Abstract

Despite well-established Pasifika communities in Australia, there has been no examination of the English spoken by members of these communities in the sociolinguistic literature. Yet, research shows that Pasifika English may exhibit key differences from local ‘mainstream’ varieties. In this paper, we present a case study of members of a drill rap group with Pasifika heritage to examine whether Pasifika English features are evident in their speech. We first analyze their monophthong productions and compare these to those of mainstream Australian English speakers. We also analyze their dental fricative realizations to examine whether there is evidence of th-stopping and dh-stopping, commonly described as markers of Pasifika English. Finally, we investigate whether their speech is more syllable-timed than mainstream Australian English. The results show that these speakers produce monophthongs generally consistent with mainstream Australian English vowels, despite some small differences. We also show consistent th-fronting and dh-stopping in their speech, which serves as a marker of their Pasifika heritage. We find a tendency towards more syllable-timed speech; however, this occurs to a lesser extent than has been reported for other Pasifika varieties of English. The results suggest that these speakers index their Pasifika identities by employing indicators/markers of Pasifika English that diverge from mainstream Australian English.

1. Introduction

1.1. Pasifika Communities in Australia and Pasifika English

Contemporary Australian society is very multicultural (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2016a) and in recent years there has been an increase in attention paid to how variation in Australian English (AusE) speech production may be linked to speakers’ ethnic identities and/or non-English-speaking backgrounds (see Clothier 2019 for a recent review). According to the 2016 census, a little over 200,000 people with Pasifika heritage live in Australia (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2016b). In the census data, Pasifika (or Pacific Islander) people are broadly defined as those with ancestry from the three Pacific regions of Polynesia, Melanesia, and Micronesia, but note that this does not include people with Māori heritage, who are recorded separately (Batley 2017). Although this categorization includes people with Micronesian and Melanesian heritage, the vast majority of Pasifika people in Australia have Polynesian heritage (88%), with Sāmoan heritage the most common (37%) (Batley 2017). While the Pasifika population makes up less than 1% of the greater Australian population, it represents one of the largest Pasifika diaspora populations, along with New Zealand and the United States (Doan et al. 2023). The largest proportion of Pasifika people in Australia live in New South Wales (NSW), with the highest concentrations in two areas of Sydney: Blacktown in Western Sydney and South West Sydney (Batley 2017; NSW Government 2020).

Despite the existence of well-established Pasifika communities in Australia, as far as we are aware there has been essentially no examination of the English spoken by members of these communities in the sociolinguistic/sociophonetic literature. Yet, we know from previous work, both on local varieties of English widely spoken in Pacific nations (sometimes referred to as South Pacific Englishes (SPEs; Biewer and Burridge 2019, e.g., Fiji English: Tent and Mulger 2008; Sāmoan English: Biewer 2021)) and on English as spoken by people of Pasifika heritage in New Zealand (e.g., Starks et al. 2015; Szakay and Gibson forthcoming), that Pasifika varieties of English may exhibit key differences from so-called inner circle Englishes (Kachru 1985), or ‘mainstream’ varieties of English. It may be expected that English as spoken in Pasifika communities in Australia may share some similar features with those that have been noted elsewhere (Starks et al. 2015). Anecdotal descriptions of particular Pasifika ways of speaking are occasionally referred to in Australian popular media (e.g., Overell 2017, 2018; Stunzner 2021b), which suggests that there may be an awareness in at least some parts of the community about specific features related to Pasifika English, or Pasifika ways of speaking English, within an Australian context.

There are a number of features that have been identified as indicative of Pasifika English, particularly in speakers residing in New Zealand, which may be present in varying degrees in different speakers (some, though not all, of these features may also be observed in Māori English). For example, a lack of (or weak) aspiration in initial voiceless stops, devoicing of voiced stops and final voiced fricatives, simplification of consonant clusters, and an absence of linking-r have all been reported in previous studies (see Starks et al. 2015, and Szakay and Gibson forthcoming, for overviews of previous research). Some factors that may influence the occurrence of these features include the background of the speaker (e.g., their specific ancestry and language background) and whether English was learned as an L1/early in life, or rather as an L2 in later life (Szakay and Gibson forthcoming). In this paper, we will focus on three further features of Pasifika English: the realization of monophthongs, the English dental fricatives, and speech rhythm, which we expand on below.

Languages of the Pacific tend to have vowel systems with just 5 vowel qualities, so it may be expected that, at least in SPEs or L2 Pasifika English, there may be some differences due to transfer effects in the realization of the more complex English monophthong system. For example, Tent and Mulger (2008) describe Fiji English monophthongs as showing only 5 phonemic distinctions, based on the Fijian vowel system, with some slight phonetic variation between some of the non-contrasting vowels. Many speakers, however, learn English as an L1 or an additional language early in life, and it is not clear to what extent such transfer effects would affect such speakers’ vowel realizations, and to our knowledge descriptions of SPE/Pasifika English vowels from outside New Zealand are rare (Biewer and Burridge 2019).

There have been a few studies examining Pasifika English vowels within New Zealand (Ross et al. 2021; Starks 2008; Starks et al. 2007; Thompson et al. 2009), although these have often been limited to small numbers of speakers, and in some cases small numbers of speaker backgrounds, or did not only target Pasifika speakers. Nevertheless, one relatively consistent finding is that the kit vowel is often fronter and higher in Pasifika English than in New Zealand English (NZE) (Starks 2008; Starks et al. 2007, 2015), which has a famously centralized kit (Bauer et al. 2007) (although it should be noted that this high front kit was not observed in the study of Thompson et al. (2009), who examined the vowels of adolescents with a Niuean background, or in the study of Ross et al. (2021), who examined speakers from an area of Auckland with a high proportion of Pasifika speakers). Another difference that has been observed is that Pasifika English speakers with Tongan and Sāmoan backgrounds have lower realizations of dress compared to NZE, and variably lower and retracted realizations of trap in speakers with Tongan, Sāmoan, and Niuean backgrounds (Starks 2008). On the other hand, raised realizations of trap, dress, and lot have also been observed in speakers with Niuean backgrounds (Thompson et al. 2009). Ross et al. (2021) found evidence of lowered dress and trap in their study, despite no evidence of a high, front kit in their data. In addition, there may be a difference in vowel quality between the start and strut vowels, with a raised strut in Pasifika English speakers (Starks et al. 2007; Thompson et al. 2009). These vowels are generally considered to differ only in duration in NZE (and in AusE) (Cox and Palethorpe 2007; Warren 2006).

Given the high level of migration and movement of Pasifika people to and from New Zealand, in addition to media influence and tourism, there is a high level of contact between SPE/Pasifika English and NZE (Biewer 2015, 2021; Gibson 2016), so one may expect to observe an influence of NZE on Pasifika English vowels in speakers who do not live in New Zealand (Biewer and Burridge 2019). Whether this would also be the case for Pasifika people who have migrated to Australia is yet to be explored, although for some the pathway to Australia is via New Zealand (Doan et al. 2023), so it is possible that there may be evidence of similarity between Pasifika English vowels from speakers in Australia and what has been described for Pasifika English vowels in New Zealand.

A further well-known feature of Pasifika English is the tendency for the English dental fricatives to be fronted or stopped. Dental fricatives are typologically rare in the world’s languages (Maddieson 2013), and it is not uncommon for speakers of postcolonial varieties of English with no dental fricative in the substrate language (or for L2 speakers generally) to produce fronted (i.e., realized as labiodental fricatives) or stopped (i.e., realized as dental or alveolar stops, or, in some cases, affricates) realizations of these sounds. In Pasifika English, however, the voiceless dental fricative /θ/ tends to be fronted to [f], whereas the voiced dental fricative /ð/ tends to be stopped to [d] (or affricated as [dð]) (Bell and Gibson 2008; Gibson and Bell 2010; Gibson 2016; Starks and Reffell 2006), and this particular combination of strategies appears to be characteristic of Pasifika English (Starks et al. 2015; Szakay and Gibson forthcoming). Previous studies report that fronting of /θ/ (hereafter canonical-th fronting) is more common in coda position/word finally than in onsets/word initially (Gibson and Bell 2010; Starks and Reffell 2006), whereas stopping of /ð/ (hereafter canonical-dh stopping) occurs most frequently in onsets, especially at the beginning of an utterance (Bell and Gibson 2008; Gibson 2016). Fronting of /ð/ (i.e., with a voiced labiodental fricative realization [v]) is also reported to occur, albeit less frequently, in coda position and word medially, along with canonical dental fricative realizations (Bell and Gibson 2008; Starks and Reffell 2006).

Szakay and Gibson (forthcoming) highlight that while fronting and stopping of dental fricatives, which likely came about due to transfer effects given the lack of dental fricatives in Polynesian languages, may be expected in (late) L2 Pasifika English, its presence in English-dominant/L1 speakers has taken on social meaning as a marker of Pasifika identity.1 Gibson (2016) and Gibson and Bell (2010) show that higher rates of canonical-th fronting/-dh stopping are found in speakers who learned English as an L2 in later life, compared to speakers who learned English as an L1, or from a young age. In their analysis of fictional characters from a television program, Gibson and Bell (2010) also show that an increase in canonical-th fronting/canonical-dh stopping may be linked to a tough, streetwise persona, whereas less of these variants were observed in a ‘studious’ character, who avoids vernacular forms.

As far as we are aware, there has been no direct examination of speech rhythm in Pasifika English; however, it has been suggested that Pasifika English may exhibit a more syllable-timed rhythm compared to other mainstream English varieties (Biewer 2021; Starks et al. 2015). As many Polynesian/Pasifika languages are more syllable-timed than English, this is likely to be due to substrate language influences (Biewer 2021; Szakay and Gibson forthcoming; Warren 1998; Zuraw et al. 2014). Possibly related to the idea of a more syllable-timed rhythm, monophthongization of diphthongs has been shown to occur in Pasifika English, along with less diphthongization in vowels such as fleece and goose, which tend to show diphthongal qualities in their on- and off-glides in AusE and NZE (Starks et al. 2007, 2015; Thompson et al. 2009). In addition, shortening of diphthongs and of some monophthongs is reported in Pasifika English, along with a reduction in vowel length distinctions (particularly for the vowel pair /iː, ɪ/) (Biewer 2015, 2021; Starks et al. 2015; Tent and Mulger 2008; Thompson et al. 2009). Unstressed syllables in polysyllabic words may also exhibit less vowel reduction than is typical of mainstream English, with equal stress on each syllable/mora (Biewer 2021). These may all contribute to the perception of a more syllable-timed rhythm. Speech rhythm has been more widely examined in Māori English, with results pointing towards a more syllable-timed rhythm compared to NZE, with less variation in vowel duration across successive syllables (Szakay 2006; Warren 1998). This syllable-timed rhythmic characteristic is salient to New Zealand listeners, who are able to rely on it when identifying Māori English based on prosodic cues alone in a perception task (Szakay 2012). This perceptual sensitivity demonstrates that the syllable-timed rhythmic pattern has become enregistered as a marker of Māori English speech.

Anecdotal observations of Pasifika speech in Australia suggest the presence of at least some of the features described above. Therefore, English as spoken by Pasifika peoples in the Australian context represents a promising site for sociophonetic investigation; however, there is a lack of representation of speakers with Pasifika heritage in the available corpora of AusE, rendering the examination of the speech of this community difficult. In the next sections, we describe a contemporary musical group that may provide a novel resource of Pasifika speech in the AusE context.

1.2. Drill Music and OneFour

Recently, a sub-genre of hip hop known as drill rap has emerged as a new force in the Australian musical landscape. Drill has its origins in the US, but a large drill scene has developed and flourished in and around London (Hodgson 2023), and UK drill was and continues to be especially influential for Australian drill rap groups. Of particular interest with respect to this paper is that many, if not most, Australian drill rappers are of Pasifika background. The most prominent Australian drill rap group is OneFour, a group of Sāmoan Australian men from the suburb of Mount Druitt, which is within the City of Blacktown in the western suburbs of Sydney. OneFour have achieved ground-breaking success for an Australian rap group, as well as a level of infamy previously unseen in Australian popular music, primarily due to alleged associations with youth gangs and their often violent and confronting lyrics depicting tales of gang activities (Hagemann 2020; Fazal 2020). This has seen them come under heavy surveillance from police and being banned from playing live in NSW and other parts of the country (Fazal 2020).

As noted above, OneFour hail from Mount Druitt, which is within Blacktown, an area of Western Sydney which has one of the largest concentrations of Pasifika people in all of Australia (Batley 2017; NSW Government 2020). This is also an area of low socio-economic status that has been stigmatized and lampooned in the Australian media (e.g., Aubusson 2015; Molitorisz 2011); for these artists, however, loyalty and affiliation to their neighbourhood is a source of fierce pride that is conveyed in both their lyrics and in interviews. Their connection to the local area, Mount Druitt specifically and Western Sydney more generally, is an important motif in their music, and is frequently referred to in their lyrics and figures prominently in imagery surrounding the group. In addition to their local area, the group also reference their Pasifika heritage in their songs and in interviews, using Pasifika slang and borrowings from Sāmoan, and referring to growing up as (Pacific) Islanders in Australia. Indeed, they are seen as a source of inspiration for many Pasifika young people and the greater community, who feel empowered seeing people with Pasifika heritage achieve mainstream success and represent a Pasifika experience specific to the Australian context (Dunn 2019; Enari n.d.; Stunzner 2021a). Although their local and ethnocultural affiliations are foregrounded, the group nevertheless position themselves in a uniquely Australian context; they unashamedly utilize references to Australian popular culture (e.g., songs contain references to the long-running Australian soap opera Home and Away, the bushranger Ned Kelly, and the notorious Long Bay prison in Sydney) and infuse their raps with pig Latin and slang derived from the graffiti and criminal underworld, a hallmark of Australian ‘gutter/lad rap’ artists. Furthermore, they are considered the first Pasifika rappers to perform in an Australian accent, which is not necessarily the default for non-Anglo hip hop artists (Gibson 2020); according to Fazal (2020, p. 2), this ‘colloquial Australian context’ enables them ‘to hammer home the point that they are a product of this environment’. We may expect this complex relationship of local, ethnocultural, and situation context to manifest in the speech patterns exhibited by these speaker/rappers, and from our initial observations it indeed appears that some features of Pasifika English may be present.

In this paper, we therefore present an initial case study of the speech of these Pasifika speaker/rappers to examine whether there is evidence of features of Pasifika English as spoken in an Australian context. The analyses are based on conversational speech taken from a series of interviews and from raps performed in their released songs (see more details in Section 2 below). We analyze the realizations of their monophthong productions, and compare these to those of a set of mainstream AusE2 (MAusE) speakers, highlighting both similarities and differences. We subsequently analyze their realizations of items containing dental fricatives, to explore whether there is evidence of canonical-th stopping/-dh stopping, a pattern commonly described as a marker of Pasifika English. Finally, we explore whether there is evidence for more syllable-timed speech in the Pasifika speaker/rappers compared to MAusE speakers. Of course, given the small number of informants we realize that this case study cannot provide much more than an anecdotal description of a very limited number of speakers. Nevertheless, as the most prominent representatives of the Pasifika community in Australia currently, we hope that this analysis may highlight some tendencies, and may propel further, more generalized research with Pasifika speakers from the greater community.

2. Materials and Methods

The data used for the analysis in this paper are a small corpus of songs officially released by the group and interviews with various members of the group. The corpus comprises 20 song files and 5 interview files. All of the group’s officially released songs between 2017 and 2020 were included; these comprised all of the group’s official releases from their first single up to and including their first EP, which was released shortly before the analysis was undertaken. The songs range from just under one minute to just under 5 min in duration (mean = 3.2 min). Song files were purchased through Apple Music and downloaded in m4a formant, and subsequently converted to single-channel wav files. Interviews were sourced through the online video sharing platform YouTube with audio captured in wav format through the Google Chrome audio capture extension (version 1.1.2).3 The interviews included shorter as well as longer, extended response interviews, ranging from 3.5 min to 28 min in duration (mean = 16.4 min). All of the files were first orthographically transcribed in Praat (Boersma and Weenink 2022) textgrids with each speaker/rapper’s productions identified on separate tiers. Initial orthographic transcriptions for the songs were sourced from online fan sites. Initial orthographic transcriptions for the interviews were produced using the Speech to Text API from IBM Watson (https://www.ibm.com/cloud/watson-speech-to-text accessed on 16 May 2023), using an AusE language model. All transcriptions were manually checked and corrections were made where these were deemed to be inaccurate. All data were then processed using WebMAUS (Kisler et al. 2017), resulting in the output of automatically segmented and force-aligned text grids. These were then hand checked and all vowel segment boundaries were corrected where necessary. The resulting files were then converted into an EMU database using emuR (Winkelmann et al. 2017).

It should be pointed out that although the group comprises 5 members, each member is not evenly represented in the corpus. This is primarily due to the fact that three of the group’s members were incarcerated at the time of the release of the group’s EP, and therefore only contributed minimally to the songs that were included on that release (9/20 songs), and likewise did not take part in the longer interviews promoting that release. For this reason, a full set of monophthongs was not able to be extracted for these three speaker/rappers, and so in the analysis of monophthongs we focus on the monophthong realizations of only two of the group’s members. Similarly, as the analysis of speech rhythm is based on longer stretches of conversational speech, we only analyze the two remaining speaker/rappers’ productions in this analysis. All 5 speaker/rappers’ productions are, however, included in the analysis of dental fricatives.

2.1. Analysis of Monophthongs

In this analysis, we examined 11 AusE monophthongs in the speech of the Pasifika speakers and compared them to productions of the same monophthongs by a set of MAusE speakers. The monophthongs included in the analysis are as follows: /iː, ɪ, e, æ, ɐː, ɐ, ɔ, oː, ʊ, ʉː, ɜː/,4 corresponding, respectively, to the lexical sets (Wells 1982) fleece, kit, dress, trap, start, strut, lot, north, foot, goose, and nurse, which we will use for reference below. We do not include /eː/ (square) in our analysis, as this vowel may be variably produced as either a monophthong, a diphthong, or as disyllabic in some speakers (Harrington et al. 1997), nor do we examine schwa. Note that although we do not examine any vowels labeled as schwa, as this analysis is based on spontaneous speech, it is likely that some items will have been labeled as full vowels according to their canonical realization, despite having been produced with phonetically reduced realizations.

The data for this analysis were taken from the interview data contained in the corpus described above. We had initially planned to also examine monophthongs extracted from the songs, as there may be interesting differences in vowel productions between performed songs and more natural, conversational speech, and previous work suggests that it is possible to extract usable formant estimates from songs (e.g., Gibson 2020); however, upon inspection of our data, formant estimates extracted from the songs were extremely noisy and would have required extensive hand correction in order to conduct a valid comparison. Therefore, in the interest of practicality and of minimizing researcher intervention, we decided to focus here only on the data from the interviews.

In addition to the monophthongs produced by the Pasifika speaker/rappers, we also extracted formant estimates of monophthongs produced by eight male speakers of MAusE to provide a baseline for comparison. The MAusE speakers were recorded as part of the Multicultural Australian English project corpus (Cox 2018; Cox et al. 2023; Penney et al. 2023b) in a face-to-face setting in 2021. All of the speakers were monolingual speakers of AusE with L1 English-speaking parents, aged 15–16, who had grown up (and currently lived) in the Northern Beaches area of Sydney. The Northern Beaches area has a lower level of linguistic diversity compared to many other parts of Sydney, and as such can be considered to be representative of MAusE, with minimal influences from speakers from other language backgrounds (Penney et al. 2023b; Penney et al. forthcoming). The speakers engaged in a picture naming task and a spontaneous conversation with a peer that was facilitated by a research assistant. Data from the spontaneous interviews only are examined here. The interviews ranged from 13.9 min to 21.75 min (mean = 18.05 min).

We first extracted all monophthongs from the interview data using emuR (Winkelmann et al. 2017). Items with very short (<30 ms) or very long (>300 ms) durations were excluded, as were items with a lateral following the vowel. In the case of trap, items with a following nasal were also excluded, as pre-nasal trap is likely to be raised and fronted (Cox and Palethorpe 2014; Grama et al. 2019). We also excluded the highly frequent words you and just, as well as vowels produced in hesitations (e.g., um, ah, oh, etc.). For the reasons detailed above, a full set of monophthongs was not able to be extracted for three of the Pasifika speaker/rappers. Therefore, we chose to exclude these speakers and focus this analysis on the two Pasifika speaker/rappers who were included in all of the interviews. Estimates of F1 and F2 frequencies were extracted for each of the 11 monophthongs of interest through PraatR (Albin 2014) using the following settings: maximum number of formants: 5; formant ceiling: 5000 Hz; window length: 0.025 s, pre-emphasis from 50 Hz. Target values were identified within the middle 60% of each monophthong according to the following criteria: at F2 maximum for high front vowels (fleece, kit, dress, and goose); at F2 minimum for high back vowels (lot, north, and foot); at F1 maximum for low vowels (trap, start, and strut); and at the midpoint for nurse. Outliers with values greater than 2.5 standard deviations from the (per vowel, per speaker) mean were excluded. This resulted in 5364 items for analysis (Pasifika: 2750; MAusE: 2614). Finally, as there are likely to be differences in vocal tract size between the two groups of speakers, formant estimates were normalized using the Lobanov 2.0 method (Brand et al. 2021), which is an updated version of Lobanov’s (1971) method that is suited to unbalanced datasets.

We analyzed F1 and F2 separately using linear mixed-effects regression models fitted with the lme4 package (Bates et al. 2015) in R (R Core Team 2020). For each model, the dependent variable was the normalized formant value (i.e., either F1 or F2), and the fixed effects were vowel (each of the 11 monophthongs) and group (Pasifika vs. MAusE). Random intercepts were included for speaker and for word. Random slopes were initially included for vowel by speaker, but this resulted in model non-convergence, so the random structure was simplified. The significance of overall model terms was evaluated with the afex package (Singmann et al. 2021) through type III tests with Kenward–Roger approximation of degrees of freedom. Pairwise comparisons were conducted with the emmeans package (Lenth 2020). Full model summaries of the models are included in Table A1 and Table A2 in Appendix A.

2.2. Analysis of Dental Fricatives

In this analysis, we examined the realization of the English dental fricatives as produced by the Pasifika speaker/rappers, to explore whether there is evidence of canonical-th fronting and canonical-dh stopping, a pattern that is commonly described as a marker of Pasifika English (Starks et al. 2015; Szakay and Gibson forthcoming). Of course, dental fricatives are not only typologically rare (Maddieson 2013), they are also relatively restricted in English, and therefore many of the items canonically containing dental fricatives in our dataset occur in a small set of function words: the words the, that, they, there, and with (and various forms of these) are the 5 most frequent words in our dataset. This necessarily limits opportunities for examining social meanings attached to specific words/topics. Note that, in this analysis, we did not compare the Pasifika speaker/rappers’ dental fricative realizations to those of the MAusE speakers, as canonical-th fronting/-dh stopping is not generally reported in MAusE (though see Rieschild (2007) and Warren (1999) for descriptions of these in some ethnolectal varieties of AusE), nor was there evidence of this in our MAusE speakers.

As this analysis was not reliant on formant measures, the data were taken from the interviews as well as from the songs contained in the corpus, which enabled a larger set of data and also allow for a comparison of possible differences between rap/speech in performed songs and in more natural, conversational data. As discussed above, most of the speech/raps contained in the corpus come from only two of the members of the group, with the other three members accounting for a smaller proportion of the data, which are primarily found in the songs. In the case of the dental fricatives, 84% of the items were produced by these two speaker/rappers, with the other 16% by the other three. In order to extend our analysis to other members of the group and to increase the amount of data available for analysis, we included items produced by all 5 speaker/rappers in this analysis.

Using emuR (Winkelmann et al. 2017), we extracted all items containing voiceless /θ/ and voiced /ð/ dental fricatives in their canonical transcriptions, which we refer to as canonical-th and canonical-dh items, respectively. This resulted in 2068 items combined. Using a combination of auditory analysis and visual analysis of the spectrograms, each item was categorized by the first author according to its realization, as one of the following variants:

- A voiced dental fricative: dh;

- A voiceless dental fricative: th;

- A voiced/voiceless alveolar stop: stop;

- A voiced labiodental fricative: v;

- A voiceless labiodental fricative: f;

- Deleted: del.

Note that the stop category includes both items produced as a canonical alveolar stop (either voiced or voiceless depending on the context), as well as those produced as alveolar taps. Furthermore, we do not distinguish between stopped variants and those that are affricated (cf. Bell and Gibson 2008), treating these both as examples of stop (as in Gibson and Bell 2010).

Thirty-eight items were not able to be categorized with any level of certainty, due to occurring in overlapping speech, coinciding with a drum beat or other sound effect in the songs, or for being otherwise unclear; these items were excluded from the analysis. This resulted in 2030 items remaining for the analysis. To ensure consistency in the categorization of realizations, approximately 10% of the data was subsequently re-categorized by the second author and checked for reliability using the irr package (Gamer et al. 2019). Strong agreement was found between the annotators (k = 0.845; z = 21.9; p < 0.0001) (McHugh 2012).

Each item was labeled according to context (i.e., if it was produced in an interview or song) and the syllable position that the canonical-th/-dh occupied in the word (onset or coda). Note that the coda category includes word medial items that may potentially be ambisyllabic, such as nothing, brother, etc. (though not something, which is syllable initial despite being word medial). Table 1 summarizes the number of items in each syllable position according to context. From this table it can be seen that for both canonical-th and canonical-dh items, the majority of items are found in onset position, with substantially fewer items in intervocalic and coda positions. It can also be seen that canonical-th items were relatively infrequent in the corpus overall and particularly infrequent in coda position. The small number of canonical-th items therefore precluded the modeling of the distribution of realizations. For this reason, we present only a descriptive analysis of these items below. For the canonical-dh items we include statistical modeling as well as a quantitative description.

Table 1.

Summary of canonical-TH/DH items according to context and syllable position.

For the canonical-dh items, we analyzed the data using a generalized linear mixed-effect regression model fitted with the lme4 package (Bates et al. 2015) in R (R Core Team 2020). For the dependent variable, we calculated a binary predictor of the most frequent realization, stop, versus all other realizations combined. Fixed effects were syllable position (onset vs. coda) and context (interview vs. song). We also included an interaction term between the two fixed factors. Random intercepts were included for speaker and word.

2.3. Analysis of Speech Rhythm

In this analysis, we explored whether there is evidence for more syllable-timed speech in the speech of the Pasifika speakers than in speakers of MAusE, through an examination of speech rhythm using the normalized Pairwise Variability Index (nPVI) (Grabe and Low 2002; Low et al. 2000). The data for this analysis were taken from the corpus of interviews described above. We extracted data from a recording of a single interview with the Pasifika speakers. Note that only two of the speaker/rappers were included in this interview, for reasons outlined above. This was one of the longer interview files (27 min) and contained roughly equal amounts of spontaneous speech from both speakers, including many extended responses. To provide a baseline for comparison, we also analyzed the recordings of the eight MAusE speakers included in the analysis of monophthongs described above.

For each speaker we calculated an nPVI score based on vowel duration (Low et al. 2000). The nPVI provides a measure of how similar in duration each vowel (i.e., each syllable nucleus) is to the next, and is calculated as the difference between a vowel and the following vowel, divided by the average duration of both vowels, which is then averaged across all differences and multiplied by 100 to give an integer value.

Variability in the duration of successive vowels has been shown to increase when a higher number of minimum syllables are included (Fuchs 2016). Therefore, following Deterding et al. (2022), based on findings in (Fuchs 2016), only vowels produced in phrases with six or more syllables were included in the analysis. Non-vocalic sonorants were not labeled as vowels, and items with lateral codas were segmented into vowel/consonant segments where there was a visible change in quality or, in the case of no clear change, at the midpoint of the sequence. Any vowels occurring in hesitations or false starts were excluded. Following Deterding et al. (2022), items that were labeled as schwa and any vowels with a duration of less than 30 ms were excluded, as small differences in successive short vowels may exert undue influence on the nPVI measure. In the case of adjacent vowels (e.g., in words such as skiing /skiːɪŋ/), these were treated as two separate vowels if there was a visible change in vowel quality (Torgersen and Szakay 2012). This resulted in 9137 items for analysis (Pasifika: 3448, with 1647–1801 items per speaker; MAusE: 5689, with 565–996 items per speaker).

One of the MAusE speakers was identified as an outlier, with an nPVI score more than two standard deviations lower than the mean nPVI score for the MAusE group; this speaker was therefore excluded from the analysis. As this analysis is based on a single nPVI score per speaker, a simple linear regression model (i.e., a model with no random effects) was fitted to the data using the stats package in R (R Core Team 2020). The dependent variable was the nPVI value per speaker, with a fixed factor of group (Pasifika vs. MAusE).

3. Results

3.1. Results: Analysis of Monophthongs

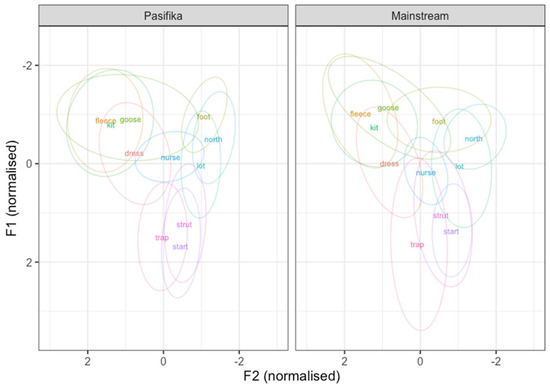

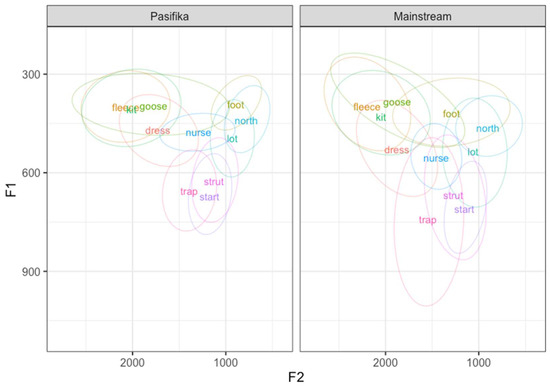

Figure 1 illustrates the vowel space of each group of speakers, with the mean values of each monophthong represented by the relevant lexical set label. As can be seen, the vowel spaces of the two groups appear on the whole to be quite similar, though there are some noticeable differences. In particular, foot appears to have a more retracted realization in the Pasifika speakers, dress and nurse have higher realizations in the Pasifika group, and the high front vowels fleece, kit, and goose show greater overlap in the Pasifika group than in the MAusE speakers. In addition, the low vowels in the two groups exhibit a different pattern, with start occupying the lowest position (i.e., highest F1) in the vowel space of the Pasifika speaker/rappers, compared to trap for the MAusE speakers, which also shows a greater degree of variability (as visible in the size of the ellipse).

Figure 1.

F1 and F2 (Lobanov 2.0 normalized) values for each vowel according to group. Lexical set labels represent mean values. Ellipses represent 95% confidence intervals.

For F1, there was a significant interaction between vowel and group (F(10, 4813.92) = 10.98; p < 0.001). Pairwise comparisons showed that there was a significant difference between the groups for dress (p < 0.0001) and nurse (p = 0.0036), which were both lower (produced with a higher F1) in the MAusE group, fleece (p < 0.0001) and goose (p < 0.0001), which were both higher (produced with a lower F1) in the MAusE group, and for start (p = 0.0025) and strut (p < 0.0001), which were both lower in the Pasifika group. We also found that, within the groups, the differences between fleece and kit and between goose and kit were significant for the MAusE speakers (p = 0.0001 and p < 0.0001, respectively), but that due to the raised realization of kit, there was no significant difference between these vowels for the Pasifika speaker/rappers (p = 0.9968 and p = 0.8191, respectively). We also note that while there was no significant difference between trap and start within either group, there was weak support for a distinction for the MAusE speakers (p = 0.0540).

The F2 model also showed a significant interaction between vowel and group (F(10, 5201.58) = 10.79; p < 0.001). Pairwise comparisons showed that there is a significant difference between the groups for foot (p < 0.0001), which is retracted in the Pasifika speaker/rappers, and for kit (p = 0.0047), fleece (p = 0.0004), and start (p < 0.0001), which have fronter realizations in the Pasifika speakers. Within the MAusE speakers, foot was significantly different to both north (p < 0.0001) and lot (p < 0.0001); however, due to the retracted realization of foot in the Pasifika speaker/rappers, there was no significant difference between these vowels within this group (foot–north: p = 0.9577; foot–lot: p = 0.7523).

3.2. Results: Analysis of Dental Fricatives

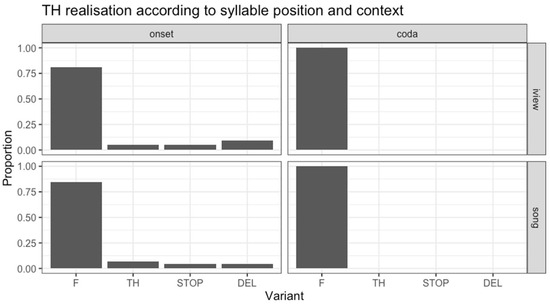

Figure 2 illustrates the distribution of realizations for the canonical-th items. Across syllable positions and contexts, the most frequent realization of canonical-th was f, occurring near categorically in 83% of all items. In onset position, 82% of items were realized as f, and this was relatively consistent between contexts (interview: 81%; songs: 85%). Of the remaining realizations in onset position, eight items were realized with stop variants (these were canonical stops rather than taps); these all occurred in the word thing(s), produced as [tʰɪŋ], or in related items such as something and everything. There were also 13 items realized as del, with all of these items occurring in the word something, in productions that can be transcribed as [sɐʔn̩] or [sɐ̃mʔm̩]. Note that not all instances of (some/every)thing were produced with these variants; there were 4 such items produced with th, as well as 59 produced with the more common f. Finally, there were 5 other items produced with th. These occurred in the words think, thanks, thought, and threat, all of which were also produced with f in other instances.

Figure 2.

Proportion of canonical-th realizations according to syllable position and context.

All items produced in coda position were realized with the f variant, and this was the case in both contexts. Recall, however, that this comprised only 13 items. This included six instances of the word nothing. The remaining items in coda position were the words fourth, fifth, north, south, truth (twice), and Penrith, a suburb in Western Sydney and the speaker/rappers’ local rugby league football team.

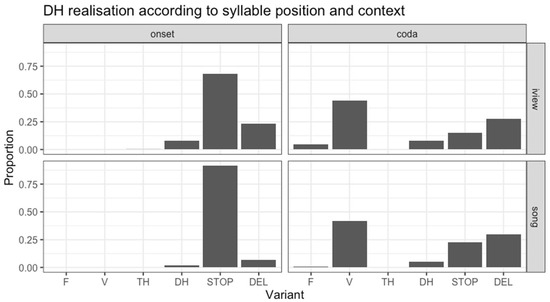

Figure 3 illustrates the distribution of realizations for the canonical-dh items. In comparison to Figure 2 above, illustrating the distribution of canonical-th realizations, it can be seen that there is greater amount of variation in canonical-dh realizations in the data. The most frequent realization across syllable positions and contexts was the stop variant, occurring in 73% of all items. This is reflected in the onset position, where stop realizations predominate in both contexts (interview: 68%; songs: 92%); however, there are far fewer stop realizations in coda position, where the most frequent variant is v (interview: 44%; songs: 42%). Although the general patterns appear similar across the two contexts, some variation can be observed: this is most visible in onset position, where there is a greater proportion of stop realizations in the songs compared to the interviews, which conversely show a higher proportion of del. Though not as immediately apparent, there is also a difference in coda position, with a greater proportion of stop realizations in the songs (22%) compared to the interviews (15%).

Figure 3.

Proportion of canonical-dh realizations according to syllable position and context.

The results of the model confirm that the difference between syllable positions is significant, with fewer stop realizations occurring in coda position (Estimate: −3.3848; SE: 0.5136; z: −6.591; p < 0.0001). In addition, there was also a significant effect of context, with more stop realizations occurring in the songs than in the interviews (Estimate: 1.4304; SE: 0.1744; z: 8.202; p < 0.0001). The interaction between syllable position and context was not significant, reflecting that there was a higher proportion of stop realizations in the songs compared to the interviews in both syllable positions.

As already mentioned, stop realizations were less frequent in coda position, where v realizations were the most frequent. Additionally, del realizations were more frequent than stop in coda position. Looking at the particular words that were produced with these variants, v was most commonly found in the word with, which was the most frequent word in coda position. As we will see below, however, not all realizations of this word were produced with v; this tended to occur primarily when the word was followed by a pause or hesitation, or when it was followed by a vowel or an /h/ initial word in which the /h/ was elided: for example, in with everything [wɪvevɹiːfɪŋ] or with (h)im [wɪvɪm]. Apart from in this word, v was also common in disyllabic words where the canonical-dh occurred word medially, such as brother, mother, either, etc. Apart from one instance of the word together, the del variant occurred exclusively in the word with, generally when this was followed by an obstruent or nasal initial word (e.g., with shows [wɪʃəʉz], with me [wɪmiː]) or when the following word began with a canonical-dh realized with a stop variant, (e.g., with them [wɪɾem], with the [wɪdə]).5 stop realizations in coda position were predominately taps, and occurred in similar environments to v, in with preceding vowel initial words and in disyllabic words such as brother, another, etc. The increase in stop realizations in coda position appears to be linked to the use of taps in prevocalic with, which occurred more frequently in the songs, whereas the v variant occurred more frequently in the interviews.

In onset position, stop realizations were essentially categorical in the songs, whereas in the interviews there was a greater proportion of del and dh variants. The bulk of the items with a del realization followed a nasal, often with an elided final obstruent, in which the rhyme of the canonical-dh initial word was resyllabified with the preceding nasal, for example in constructions such as in (th)e [ɪ̃nə], on (th)at [ɔ̃næt], an(d) that [ə̃næt], and an(d) then [ə̃nẽn] (cf. Gibson 2016). In many such cases, the nasal segment created the auditory impression of a rapid nasal tap. Less frequently, del realizations occurred following a fricative, as in cause (th)at [kəzæt], gives (th)em [ɡɪvzə̃m]. Constructions such as these rarely occurred in the songs, but were frequent in the interviews. In particular, the construction an(d) that occurred 94 times in the interviews, most often as a vague adjunctive general extender (Cutting 2019). There was also an increase in items produced with a dh realization in the interviews; though these only constituted 8% of items, this was more frequent than in the songs, where they made up less than 1% of items. In general, dh realizations tended to occur in utterance/phrase initial positions, after a pause.

3.3. Results: Analysis of Speech Rhythm

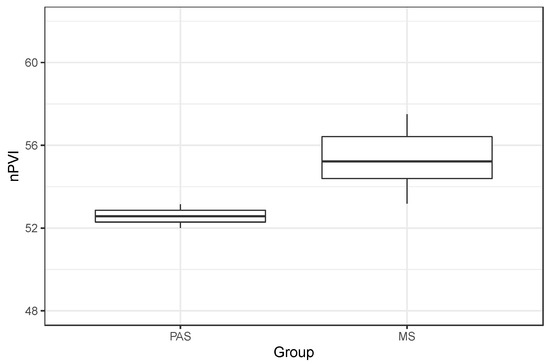

Figure 4 illustrates the nPVI scores according to speaker group, and Table 2 provides the nPVI scores according to each speaker within the two groups. From Figure 4 it can be seen that there is a difference between the groups in the expected direction, with lower scores in the Pasifika speakers pointing towards a more syllable-timed rhythm. It should be highlighted, however, that the difference is not as great as has been found in other studies on similar groups (e.g., Szakay 2006): the mean score of the Pasifika speakers was 52.6, whereas the MAusE speakers had a mean nPVI score of 55.4. Figure 4 also shows that there is greater variability in the MAusE group than in the Pasifika group, which is to be expected given the greater number of speakers included in the MAusE group, but which might also reflect greater variation in vowel duration more generally in the MAusE speakers compared to the Pasifika speaker/rappers.

Figure 4.

Normalized Pairwise Variability Index (nPVI) score by group (higher nPVI = more stress-timed; lower nPVI = more syllable-timed).

Table 2.

Mean nPVI scores according to speaker and group.

The results of the linear regression model confirm that the difference in nPVI scores between the groups is significant, with an alpha threshold value of p < 0.05 (estimate: −2.786; SE: 1.145; t = −2.432; p = 0.0453), though we note that this result should be treated with caution as it is only just below the alpha.

4. Discussion

4.1. Discussion: Analysis of Monophthongs

The results of the monophthong analysis above suggest that, despite some small differences, the monophthongs of the Pasifika speaker/rappers are generally consistent with those produced by MAusE speakers. Notably, the Pasifika speaker/rappers’ vowel space does not reflect an NZE vowel space, nor one with a large substrate influence of a Polynesian language such as Sāmoan. Rather, the Pasifika speaker/rappers’ vowel productions broadly confirm that they speak with Australian accents (insofar as this can be determined from an analysis of only monophthongs). This should not be overly surprising, given that they have grown up in Australia and are often described as having, and rapping in, Australian accents (Fazal 2020).

However, we nevertheless also identified a small number of significant differences between the Pasifika speaker/rappers and the speakers of MAusE. First, we found that there was a greater concentration of vowels in the high front area of the space for the Pasifika speaker/rappers. fleece and goose were found to be significantly lower in the Pasifika speaker/rappers than in the MAusE speakers. Moreover, kit was found to be significantly fronter and fleece significantly backer compared to the MAusE speakers. Additionally, although there was no significant difference between the two groups in terms of the F1 of kit, within the Pasifika group there was no significant difference in height between kit and fleece or between kit and goose, suggesting less dispersion of the high front vowels than is seen in the MAusE speakers. Starks et al. (2015, p. 297) describe a ‘pan-ethnic Pasifika close front kit vowel’, which may suggest some Pasifika English influence, although it should be noted that this description is based on studies of a small number of adolescent Pasifika speakers, has not been consistently found, and is in comparison to NZE kit, which is well known to have a centralized realization (Bauer et al. 2007). Biewer (2021) describes how Sāmoan English speakers may exhibit a high degree of overlap between fleece and kit, whereby they substitute fleece and kit with no apparent change in meaning. This, however, is discussed in relation to a reduction in vowel length distinctions—for example, a fleece vowel may be produced in an item such as pig which would normally be produced with the shorter kit vowel—that is common in many new varieties of English (Melchers and Shaw 2003). Additionally, according to our understanding, this suggestion was not based on spectral measurements. MAusE is known to exhibit a long on-glide in fleece, which gives it a diphthongal quality and may help to maintain perceptual difference from the otherwise spectrally similar kit (Cox et al. 2014; Harrington et al. 1997; Williams et al. 2018). Although a dynamic analysis is beyond the scope of the present paper, an interesting extension for future research would be examine whether Pasifika speakers also exhibit on-glide or whether fleece and kit are indeed spectrally merged in Pasifika speakers in Australia.

In addition, we observed that both dress and nurse were produced with higher realizations (i.e., lower F1) by the Pasifika speaker/rappers than by the MAusE speakers, though not in a manner suggestive of an NZE influence. It is possible that this difference is due to an ongoing change in MAusE, whereby both of these vowels have been lowering in tandem over an extended period (Butcher 2012; Cox and Palethorpe 2008; Cox et al. forthcoming; Grama et al. 2019). It may be that the MAusE speakers are ahead with regard to this change, and therefore show lowered realizations. In an analysis on a set of AusE speakers with either a monolingual English background (which included the MAusE speakers examined here) or another language background (Arabic, Chinese, Indian, and Vietnamese), Penney et al. (2023b) found that speakers with Arabic and Vietnamese language backgrounds produced more conservative realizations of some vowels known to be undergoing lowering, including nurse. That is, the lowering of these vowels may be a change that is being driven by MAusE speakers, and the Pasifika speaker/rappers are less advanced with respect to this change.

We also found that both start and strut were significantly lower in the Pasifika speaker/rappers, with start also fronter than in the MAusE speakers. We did not find evidence of a significant quality difference between start and strut in the Pasifika speaker/rappers (cf. Starks et al. 2007; Thompson et al. 2009). Interestingly, there were no significant differences between the groups in either F1 or F2 for trap. A lowered trap (along with dress) is suggestive of Pasifika English in New Zealand, but trap has been undergoing an ongoing lowering/retracting change in AusE, such that it is now the most open vowel in the space (Cox and Palethorpe 2001, 2007, 2008; Cox et al. forthcoming; Grama et al. 2019). This very open trap can be seen in the MAusE speakers, but in the Pasifika speaker/rappers start is the most open vowel, with a realization that is lower than trap. For the Pasifika speaker/rappers, there was no significant difference in height between trap and start, with both occupying a similar part of the space, whereas the MAusE speakers showed a trend towards significance, with trap visibly lower. trap also exhibited substantial variability in the MAusE speakers. It may be possible that the Pasifika speaker/rappers are more conservative with respect to the lowering of trap, as evidenced by their lower start, but this difference was not captured through the normalization process, as the vowel with the greatest F1 values differed between the groups. Figure A1 in Appendix A illustrates the non-normalized data. From the figure it is clear that normalization of the data was necessary, as evidenced by the generally more compressed Pasifika vowel space suggesting larger vocal tracts in this group, and that a direct comparison of the non-normalized values would not be informative. At any rate, it is clear that there are differences between the two groups with respect to the low vowel system, and these present an interesting avenue for future research to explore.

Finally, we also found that foot was significantly retracted in the Pasifika speaker/rappers compared to the MAusE speakers, such that its realization was produced similarly back as north and lot. It can also be seen from Figure 1 that the MAusE speakers show considerable variation in their realizations of foot (as visible in the 95% CI ellipses), including retracted realizations, whereas the Pasifika speaker/rappers do not. Recall also that vowels occurring prelaterally, which particularly for goose and foot generally exhibit substantial retraction, were excluded, so this is unlikely to be simply an effect of context. While Starks et al. (2015) suggest that foot may be slightly lowered in Pasifika speakers (which is not observable here), they make no mention of retraction as a feature of Pasifika English; however, a similarly retracted foot is seen in Szakay and Gibson (forthcoming) in the vowel space of a middle-aged Sāmoan man that they refer to as an ‘L2-type’ speaker of Pasifika English; similarly, in Figure 1 of Thompson et al. (2009), foot (labeled as hood) is also seen to be quite retracted, though this was based on only a small number of items. This may suggest that a retracted foot may be associated with Pasifika English, although future work will be required to explore this further.

This analysis of monophthongs has shown that, despite generally producing vowels that can be considered typical for AusE, the Pasifika speaker/rappers do exhibit some differences that may be linked to their Pasifika heritage, though this needs to be corroborated by further research. We note that this analysis has been restricted to monophthongs, and ethnolectal variation may also be evident in the diphthong system (Cheshire et al. 2011; Grama et al. 2021; Penney et al. 2023a, 2023b). Future work should examine a greater range of vowels, and consider issues of vowel duration as well as dynamics. It would also be interesting to explore the extent to which the vowel differences observed here may index specifically Pasifika identities, or whether they are rather consistent with a broader, multi-ethnolectal/non-mainstream variety of English produced by speakers from a variety of non-English backgrounds.

4.2. Discussion: Analysis of Dental Fricatives

Overall, the results of the analysis of dental fricatives presented above are broadly consistent with previous descriptions of the realization of dental fricatives in Pasifika English: canonical-th is generally fronted, and less often stopped, whereas canonical-dh is generally stopped in onset position and fronted in medial position and in codas (Bell and Gibson 2008; Gibson and Bell 2010; Gibson 2016; Starks et al. 2015). As noted above, this combination of canonical-th fronting and canonical-dh stopping, and additionally dh-fronting in medial position, is quite particular to Pasifika English, compared to many other varieties of English that may use one or the other strategy to deal with typologically rare dental fricatives. Thus, it appears that the Pasifika speaker/rappers demonstrate a clear pattern of realizing dental fricatives that signals their Pasifika heritage; however, in addition to this general pattern of th-fronting and dh-stopping (and medial dh-fronting), we also observed some additional realizations of the dental fricatives that seem to be based on particular lexical items and constructions.

Some previous descriptions suggest that th-fronting in Pasifika English is most likely in coda position and less likely in onsets (Gibson and Bell 2010; Starks et al. 2015). In coda position we indeed observed categorical fronting, which would be consistent with the previously described distribution; however, this was based on only very few items and so should be interpreted with caution. While we observed some variation in canonical-th realizations in onset position, overall the majority of onset items in our data were fronted. While th-fronting was near categorical in onset position, we also observed stopping and elision of canonical-th in a small number of items, all related to the word thing: thing(s), everything, and something. We suggest that in these particular instances, th-stopping indexes not the speakers’ Pasifika identities, but rather associations with UK drill music and perhaps hip hop more generally. th-stopping is known to be linked to hip hop and African American ‘street’ culture (Alim 2006; Cutler 1999). Moreover, th-stopping is a feature of Multicultural London English and, particularly in certain words like thing, has been suggested to have indexical associations to grime music in the UK (Drummond 2018)—a precursor to UK drill music—and the lifestyle that goes along with it. Similarly, the elision of canonical-th, along with glottalization and a nasal syllabic nucleus, in words like something is common in African American English (Wolfram 1969) and is commonly used in hip hop music, often stylized as sum’n. Tollfree (1999) also reports a glottal stop variant of something [sɐ̃mʔɪŋ] in London English. Therefore, it may be that these speaker/rappers are referencing their association to drill music, or perhaps to hip hop more generally, through their divergent realization of canonical-th in this/these lexical items.

In our data, dh-stopping is the most common realization of canonical-dh in onset position, and this occurs at higher rates than what has been described in previous studies (e.g., Bell and Gibson 2008). We note that such a high level of dh-stopping has been attributed to speakers who learned English as an L2 in later life, rather than as an L1 or from a young age (Gibson and Bell 2010; Gibson 2016). Therefore, it might be expected that our speaker/rappers would show less consistent use of dh-stopping in onset position, given that they have grown up in an Australian-English-speaking environment and, as shown above, produce monophthongs broadly consistent with AusE. On the other hand, Gibson (2016) suggests that dh-stopping may carry social meanings linked to toughness and masculinity among Pasifika speakers (particularly among those who acquired English early), characteristics that go hand-in-hand with drill music. This would be consistent with the reduction in stopped variants in the interviews compared to the songs, where a tough image is more likely to be consistently projected. Although, as noted above, the primary difference in onset position in the interviews was the increase in instances of del, which occurred mainly in spoken constructions that were not present in the songs. Nevertheless, it is possible that the high level of dh-stopping is related to an element of performance, contributing simultaneously to the projection of a tough and also markedly Pasifika identity.

Another difference observed in the data analyzed here is the relatively rare occurrence of dh variants, particularly in coda position, where this occurred word medially (i.e., in words such as brother, mother, etc.), and the high proportion of other realizations (v, stop, and del) in this position. Bell and Gibson (2008) report that canonical-dh was consistently realized as dh in medial position in their study, and, although only based on a small number of items, Gibson (2016) also reports the relatively consistent use of dh in medial position for one of his speakers (with the other preferring the stop variant). Starks and Reffell (2006) also found high rates of dh in their analysis, although this was based on a reading passage and only low rates were found for any non-standard variants in their data. Here, however, we only observed minimal occurrence of dh variants. So, similar to the use of stopped variants in onset position, it appears that these speaker/rappers’ productions would suggest a stronger use of these forms than previous analyses suggest to be common. Szakay and Gibson (forthcoming) state that th-fronting and dh-stopping have progressed from being simply features of Pasifika English, through L2 acquisition of English, to serve as markers of Pasifika identity; it would thus appear that these speaker/rappers index their Pasifika heritage through their relatively consistent use of these markers in both songs and more conversational settings. Of course, it is possible that the high rates of use of these markers of Pasifika identity found here are due to the fact that the speaker/rappers are performing, both in the songs and in the more conversational speech. Therefore, future research should examine how representative these patterns of canonical-th stopping and canonical-dh stopping are in the speech of other Pasifika speakers of AusE in more general settings.

4.3. Discussion: Analysis of Speech Rhythm

The results of the analysis of speech rhythm described above suggest that there may be a tendency towards more syllable-timed speech in the Pasifika speaker/rappers compared to the MAusE speakers, with lower nPVI scores indicating less alternation in vowel duration across consequent syllables; however, we stress that this interpretation should be treated with caution and that further analysis is necessary to confirm whether a more syllable-timed speech rhythm is indeed a feature of Pasifika speech. Although the Pasifika speaker/rappers showed lower nPVI scores compared to the MAusE speakers, and this difference was found to be significant, the difference between the two groups was not as great as has been seen in other similar comparisons; for example, between Māori English and Pakeha NZE speakers (Szakay 2006), and the p value could be considered to be close to borderline at an alpha threshold of 0.05. In addition, this analysis is based on the speech of only two of the Pasifika speaker/rappers, and so whether the patterns observed here will generalize to other members of the greater Pasifika community (within and/or without Australia) remains to be seen. There is also the fact that, although the recordings of both groups were of natural, conversational speech, the tasks the speakers from the two groups were engaged in were quite different: the Pasifika speaker/rappers were engaged in an interview following the release of their EP and a rapid rise in success, as well as much-publicized police pressure and surveillance. The MAusE speakers, on the other hand, were teenagers recorded in conversation with a peer and a research assistant at their school. Therefore, it is not possible to rule out that in the case of more closely matched tasks and participants, the results may look quite different, and this could result in either more or less difference between the groups.

Nevertheless, the results do show a tendency in the expected direction, and are consistent with previous suggestions with respect to Pasifika English; namely, that Pasifika English may be more syllable-timed (Biewer 2021; Starks et al. 2015). This makes sense in the light of observations that vowel length contrasts often appear to be minimized in Pasifika English and SPEs (Biewer 2015, 2021; Starks et al. 2015; Tent and Mulger 2008; Thompson et al. 2009). As noted above, Māori English has also been shown to be more syllable-timed than NZE, so it may not be surprising that Pasifika English may also exhibit a less stress-timed speech rhythm compared to MAusE, given a number of similarities are shared between Pasifika English and Māori English, and both varieties have Polynesian substrates (Szakay and Gibson forthcoming). On the other hand, the results here do not appear to be as conclusive as has been found to be the case for Māori English (Szakay 2006; Warren 1998). Future research on a greater number of speakers is needed to better understand whether the rhythmic patterns of Pasifika English can be considered as a marker of Pasifika heritage.

5. General Discussion

Overall, the results presented here indicate that there are some features of Pasifika English that can be observed in the speech of these Pasifika speaker/rappers within an Australian context. The monophthong productions of these speaker/rappers are generally consistent with those of MAusE speakers. That is, their vowel productions confirm that they speak with Australian accents, and there is no evidence to suggest that they produce monophthongs that exhibit an overly NZE influence; however, we also identified a number of differences from MAusE vowels, which are consistent with observations of Pasifika English vowel realizations that have been reported in New Zealand, and which we suggest may be linked to the speaker/rappers’ Pasifika heritage. We have also shown that there is consistent TH-fronting and DH-stopping in the Pasifika speaker/rappers’ speech, which is not common in mainstream Australian English, but which has previously been identified as a marker of Pasifika identity. We furthermore found that there is a tendency towards a more syllable-timed rhythm in the Pasifika speaker/rappers’ speech than in MAusE, although this effect was not found to be as strong as what has been previously reported for other varieties, such as Māori English, and it is not clear whether this difference in rhythm is a robust marker (or perhaps merely an indicator) of Pasifika English. Nonetheless, taken together these results suggest that these speaker/rappers index elements of their Pasifika heritage and identities by employing features of Pasifika English, thereby showing a level of divergence from MAusE.

We acknowledge that a major limitation of this paper is that we have a very small sample of speakers. Nevertheless, we hope that this paper can shed a small light on a substantial community within our population, and the ways of speaking that may be linked to these speakers’ identities, which have heretofore passed very much under the radar. We would also like to point out that small sample sizes are an issue that has plagued much of the previous research that has been conducted on Pasifika English and SPEs, and more generally much work on ethnolectal variation in small communities outside of the mainstream, reflecting the lack of resources and investment in, and in some cases awareness of, such communities. The features identified here in the speech of these very visible representatives of the Australian Pasifika community may now serve as a stimulus from which to conduct a more controlled study with a larger set of informants. To this end we also offer a few anecdotal observations of other possible features for future examination that we have frequently observed in these speaker/rappers’ speech but which have not been analyzed directly here: differences in voice quality (cf. Szakay 2012), final cluster reduction (cf. Biewer 2021), retraction of [stɹ] clusters, and, more generally, the realization, and apparent substitution, of the sibilant fricatives [s] and [ʃ] (Biewer 2021). We also add that future examination of phonetic data should be paired with, and evaluated in the light of, ethnographic examinations of Pasifika speakers’ reflections on their heritage and how their speech is linked to their identities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.P. and A.S.; methodology, J.P. and A.S.; validation, J.P. and A.S.; formal analysis, J.P.; investigation, J.P. and A.S.; data curation, J.P.; writing—original draft preparation, J.P.; writing—review and editing, J.P. and A.S.; visualization, J.P.; funding acquisition, J.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially supported by a Chitra Fernando New Researcher Grant to the first author from the Department of Linguistics at Macquarie University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to Felicity Cox for allowing us access to the recordings of the Mainstream AusE speakers from the Multicultural Australian English corpus. We thank Hannah White for assistance with data processing and annotation. We also thank Andy Gibson, members of the MQ Phonetics Lab, audience members at ALS 2023 (where a preliminary analysis of this research was presented), two anonymous reviewers, and editors Chloé Diskin-Holdaway and Kirsty McDougall for their feedback and comments that have helped to make an improved paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Full model summary for linear mixed-effects regression model analyzing effects of vowel and group on F1.

Table A1.

Full model summary for linear mixed-effects regression model analyzing effects of vowel and group on F1.

| Estimate | SE | df | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | −0.18 | 0.04 | 148.96 | −4.827 | <0.0001 |

| vowelfleece | −0.66 | 0.05 | 2770.79 | −13.247 | <0.0001 |

| vowelfoot | −0.76 | 0.11 | 2260.10 | −7.12 | <0.0001 |

| vowelgoose | −0.71 | 0.06 | 2305.39 | −11.843 | <0.0001 |

| vowelkit | −0.61 | 0.05 | 2858.43 | −11.328 | <0.0001 |

| vowellot | 0.22 | 0.06 | 2135.26 | 3.923 | 0.00009 |

| vowelnorth | −0.34 | 0.07 | 2293.04 | −4.852 | <0.0001 |

| vowelnurse | 0.02 | 0.09 | 2114.35 | 0.247 | 0.80467 |

| vowelstart | 1.85 | 0.08 | 2004.27 | 23.19 | <0.0001 |

| vowelstrut | 1.42 | 0.05 | 2574.46 | 26.909 | <0.0001 |

| voweltrap | 1.75 | 0.06 | 2588.55 | 30.239 | <0.0001 |

| groupMainstream | 0.22 | 0.05 | 292.76 | 4.249 | 0.00003 |

| vowelfleece:groupMainstream | −0.40 | 0.06 | 4983.91 | −6.176 | <0.0001 |

| vowelfoot:groupMainstream | −0.12 | 0.13 | 5286.58 | −0.896 | 0.37029 |

| vowelgoose:groupMainstream | −0.51 | 0.07 | 5109.81 | −6.851 | <0.0001 |

| vowelkit:groupMainstream | −0.20 | 0.07 | 5041.33 | −2.841 | 0.00452 |

| vowellot:groupMainstream | −0.21 | 0.07 | 5269.04 | −3.051 | 0.00229 |

| vowelnorth:groupMainstream | −0.23 | 0.09 | 4437.58 | −2.545 | 0.01098 |

| vowelnurse:groupMainstream | 0.12 | 0.12 | 3909.59 | 0.926 | 0.35426 |

| vowelstart:groupMainstream | −0.50 | 0.11 | 4448.96 | −4.726 | <0.0001 |

| vowelstrut:groupMainstream | −0.47 | 0.07 | 5222.71 | −7.203 | <0.0001 |

| voweltrap:groupMainstream | −0.13 | 0.074 | 5049.78 | −1.76 | 0.07849 |

Table A2.

Full model summary for linear mixed-effects regression model analyzing effects of vowel and group on F2.

Table A2.

Full model summary for linear mixed-effects regression model analyzing effects of vowel and group on F2.

| Estimate | SE | df | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 0.74 | 0.03 | 32.85 | 22.054 | <0.0001 |

| vowelfleece | 0.72 | 0.04 | 3746.15 | 18.762 | <0.0001 |

| vowelfoot | −1.94 | 0.08 | 2713.72 | −22.907 | <0.0001 |

| vowelgoose | 0.12 | 0.05 | 3056.79 | 2.501 | 0.0125 |

| vowelkit | 0.58 | 0.04 | 3583.84 | 13.93 | <0.0001 |

| vowellot | −1.78 | 0.05 | 2948.90 | −39.251 | <0.0001 |

| vowelnorth | −2.06 | 0.06 | 2735.94 | −37.321 | <0.0001 |

| vowelnurse | −0.90 | 0.07 | 2261.88 | −12.275 | <0.0001 |

| vowelstart | −1.22 | 0.06 | 2652.80 | −19.056 | <0.0001 |

| vowelstrut | −1.31 | 0.04 | 3420.98 | −31.698 | <0.0001 |

| voweltrap | −0.67 | 0.05 | 3196.60 | −14.764 | <0.0001 |

| groupMainstream | 0.01 | 0.04 | 46.95 | 0.302 | 0.7642 |

| vowelfleece:groupMainstream | 0.11 | 0.05 | 5300.70 | 2.412 | 0.0159 |

| vowelfoot:groupMainstream | 0.61 | 0.10 | 5340.72 | 6.373 | <0.0001 |

| vowelgoose:groupMainstream | 0.03 | 0.05 | 5341.76 | 0.613 | 0.5396 |

| vowelkit:groupMainstream | −0.13 | 0.05 | 5312.68 | −2.453 | 0.0142 |

| vowellot:groupMainstream | −0.05 | 0.05 | 5333.78 | −1.008 | 0.3135 |

| vowelnorth:groupMainstream | −0.16 | 0.07 | 4996.09 | −2.277 | 0.0228 |

| vowelnurse:groupMainstream | −0.01 | 0.09 | 4112.55 | −0.155 | 0.8765 |

| vowelstart:groupMainstream | −0.34 | 0.08 | 4874.77 | −4.336 | <0.0001 |

| vowelstrut:groupMainstream | 0.00 | 0.05 | 5340.64 | −0.043 | 0.9658 |

| voweltrap:groupMainstream | −0.02 | 0.05 | 5316.59 | −0.433 | 0.6653 |

Figure A1.

Non-normalized F1 and F2 (Hz) values for each vowel according to group. Lexical set labels represent mean values. Ellipses represent 95% confidence intervals.

Notes

| 1 | Tent and Mulger (2008) report that the pattern of canonical-th fronting/-dh stopping is also common in Fiji English, despite the presence of a voiced dental fricative in Fijian. |

| 2 | Mainstream AusE (MAusE), spoken by the majority of the population, is one of the three main AusE accent groups, along with Australian Indigenous Englishes (spoken by many First Nations people) and various ethnocultural varieties. See Cox (2019) and Cox et al. (2022) for more details. |

| 3 | As a reviewer points out, although the interviews were captured in wav format it is nevertheless likely that the audio would have undergone some degree of compression prior to this audio capture. We acknowledge that audio compression may affect formant estimation, though this depends on the level of compression, and the effects may be unpredictable (see, for example, Bulgin et al. (2010); De Decker and Nycz (2011); Sanker et al. (2021) and Zhang et al. (2021)). However, this remains beyond the scope of this analysis, and we leave it to future research to compare the vowel measures reported here with lab-based recordings of Pasifika speakers. |

| 4 | We use the symbols recommended by Harrington et al. (1997) and Cox and Palethorpe (2007) for representing AusE phonemes. |

| 5 | Note that although this may represent coalescence of two canonical-dh items into a single stop, according to the way the data were coded this was labeled as elision of the first and stopping of the second. |

References

- Albin, Aaron. L. 2014. PraatR: An architecture for controlling the phonetics software “Praat” with the R programming language. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 135: 2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alim, H. Samy. 2006. Roc the Mic Right: The Language of Hip Hop Culture. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Aubusson, Kate. 2015. Mt Druitt Community Leaders Hurt, Angry and Feeling Sick after Struggle Street Documentary. The Sydney Morning Herald. Available online: https://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/tv-and-radio/mt-druitt-community-leaders-hurt-angry-and-feeling-sick-after-struggle-street-documentary-20150506-ggvtff.html (accessed on 16 May 2023).

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2016a. Cultural Diversity in Australia. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/by%20Subject/2071.0~2016~Main%20Features~Cultural%20Diversity%20Article~60 (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2016b. TableBuilder: 2016 Census, Cultural Diversity. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/microdata-tablebuilder/tablebuilder (accessed on 16 May 2023).

- Bates, Douglas, Martin Mächler, Ben Bolker, and Steve Walker. 2015. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software 67: 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batley, James. 2017. What does the 2016 Census reveal about Pacific Islands communities in Australia? In Brief 2017/23: The State, Society and Governance in Melanesia Program (SSGM) in the ANU College of Asia and the Pacific. Canberra: Australian National University. Available online: https://dpa.bellschool.anu.edu.au/sites/default/files/publications/attachments/2017-09/ib_2017_23_batley_revised_final_0.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2023).

- Bauer, Laurie, Paul Warren, Dianne Bardsley, Marianna Kennedy, and George Major. 2007. Illustrations of the IPA: New Zealand English. Journal of the International Phonetic Association 37: 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, Alan, and Andy Gibson. 2008. Stopping and fronting in New Zealand Pasifika English. University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics 14: 42–53. [Google Scholar]

- Biewer, Caroline. 2015. South Pacific Englishes. A Sociolinguistic and Morphosyntactic Profile of Fiji English, Samoan English and Cook Islands English. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Biewer, Caroline. 2021. Samoan English: An emerging variety in the South Pacific. World Englishes 40: 333–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biewer, Caroline, and Kate Burridge. 2019. World Englishes old and new: English in Australasia and the South Pacific. In The Cambridge Handbook of World Englishes (Cambridge Handbooks in Language and Linguistics). Edited by Daniel Schreier, Marianne Hundt and Edgar Schneider. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 282–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boersma, Paul, and David Weenink. 2022. Praat: Doing Phonetics by Computer (Version 6.2.14). Available online: https://www.praat.org/ (accessed on 16 May 2023).

- Brand, James, Jen Hay, Lynn Clark, Kevin Watson, and Márton Sóskuthy. 2021. Systematic co-variation of monophthongs across speakers of New Zealand English. Journal of Phonetics 88: 101096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulgin, James, Paul De Decker, and Jennifer Nycz. 2010. Reliability of formant measurements from lossy compressed audio. Paper presented at British Association of Academic Phoneticians, London, UK, March 29–31; Available online: http://research.library.mun.ca/id/eprint/684 (accessed on 16 January 2024).

- Butcher, Andrew. 2012. Changes in the formant frequencies of vowels in the speech of South Australian females 1945–2010. Paper presented at the 14th Australasian International Conference on Speech Science and Technology, Sydney, Australia, December 3–6; Edited by Felicity Cox, Katherine Demuth, Susan Lin, Kelly Miles, Sallyanne Palethorpe, Jason Shaw and Ivan Yuen. Canberra: Australasian Speech Science and Technology Association Inc., pp. 449–53. [Google Scholar]

- Cheshire, Jenny, Paul Kerswill, Sue Fox, and Eivind Torgersen. 2011. Contact, the feature pool and the speech community: The emergence of Multicultural London English. Journal of Sociolinguistics 15: 151–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clothier, Josh. 2019. Ethnolectal variability in Australian Englishes. In Australian English Reimagined: Structure, Features and Developments. Edited by Louisa Willoughby and Howard Manns. London: Routledge, pp. 155–72. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, Felicity. 2018. Multicultural Australian English: The New Voice of Sydney. Canberra: Australian Research Council Future Fellowship FT 180100462. [Google Scholar]