Abstract

The growing field of family language policies (FLPs), defined as overt and explicit planning in relation to language use among family members, has garnered increasing interest. FLPs influence child–caretaker interactions and are closely linked to child language development and acquisition. This study investigates the impact of FLPs on children’s proficiency in their heritage language (HL). Employing a multi-method approach, we conducted semi-structured interviews with 53 multilingual parents to explore their beliefs, ideologies, and language management within the family context. Concurrently, their children were administered standardized tasks in their heritage language (HL) to assess receptive vocabulary skills and morphosyntactic comprehension. Our findings indicate that parents’ perceived value of the HL significantly correlates with their children’s language performance, going beyond the influence of reported domestic language usage.

1. Introduction

Maintaining a heritage language amid a dominant societal language presents challenges for migrant families. Many factors might intervene in shaping language trajectories and language choice. The present study, based on a multi-method approach, focused on the interplay between family language policies (FLPs) and children’s linguistic competence in heritage language (HL).

King et al. (2008, p. 907) defined FLPs as the “overt […] and explicit planning […] in relation to language use within the home among family members”. According to Spolsky (2004), FLPs are related to beliefs and ideologies (e.g., regarding the social importance of the HL), practices (including the adoption of code-switching), and language management (any attempt to direct language use and learning, e.g., the employment of teaching strategies to sustain the children’s HL maintenance) (see also Curdt-Christiansen 2009; Curdt-Christiansen 2018; Hollebeke et al. 2023; King et al. 2008). The field of FLPs is disclosing much of how families manage their languages (practices), also as a result of larger social influences (ideologies), which impact their convictions (beliefs) and agency towards domestic language uses (management). However, a few empirical studies have investigated, through objective measures (Schwartz 2010), the impact of FLPs on specific features of children’s early language development. For example, Schwartz (2008) reported that FLP explained a large portion of the variance in children’s proficiency and children’s motivation towards their HL (Schwartz 2008).

Therefore, more research is needed to understand how children’s competence in HL relates to the FLPs they are exposed to and participate in. Gaining a better awareness of these dynamics is not only valuable per se; it represents a crucial first step to promoting the plurilingual repertoire of children with migrant backgrounds as well as plurilingualism in general (e.g., Council of Europe 2016, 2020). Since it is primarily up to the family to provide the necessary conditions for the youngsters to maintain their HL (e.g., Curdt-Christiansen 2022), understanding these conditions and how they relate to each other is pivotal.

1.1. Family Language Policies and HL Maintenance

The kind of choice a family makes about their language usage, e.g., to use it at home and take measures to hand down a heritage or minority language to children, largely depends on the perceived value of the language considered by the speaker per se (in terms of beliefs), which in turn can be influenced by broader societal attitudes and ideologies (Schroedler et al. 2022).

In the present study, we will adopt the terms “heritage” and “minority language” mostly as synonyms. Both expressions, although questioned by García (2005) and Pedley and Viaut (2019), emphasize how the status of a language depends largely on its power relations with other languages spoken in the same territory. A main consequence of power relations among languages is that people tend to displace the minority (or heritage) languages and shift to societal language(s) (e.g., Suarez 2002; Montrul and Polinsky 2021). This aspect has a profound impact since languages, as communication tools, also serve as carriers of cultural identity (Templin et al. 2016).

Family language policy is important for HL language maintenance because it sets the frame for child–caretaker interactions and is intrinsically connected with child language development and acquisition (King et al. 2008). Yet, FLP outcomes on children’s language proficiency vary based on family-specific factors and the importance assigned to HL maintenance. For example, Altinkamis and Simon (2020) conducted a study about the effect of family background (i.e., the parents’ linguistic background and their socioeconomic status) and language exposure/usage within the home context on the linguistic development of Turkish/Dutch bilingual children, in both the heritage and the majority languages. Their findings revealed that family background impacted children’s scores, especially in their Dutch. Language exposure/usage at home played a role in both languages, showing that input quantity, as expected, is a key variable in HL development. However, other factors—namely, how family members value the HL—play a main role too. Schwartz and colleagues (2008) tested vocabulary knowledge among second-generation Russian–Jewish immigrants in Israel. Results suggested that children’s learning was influenced by the family’s efforts towards HL maintenance through family and non-formal teaching and the children’s positive approach toward home language acquisition. Studies on trilingual children showed that heritage languages can positively affect the development of the majority language. Such effects may support positive attitudes towards heritage languages in countries with one majority language (Scalise et al. 2021).

1.2. Children’s Linguistic Trajectories in Plurilingual Contexts

Children’s linguistic trajectories might vary according to a complex interaction between familiar, societal, and individual factors when growing up in plurilingual contexts. A model proposed by Paradis (2023) describes some of the main factors influencing bilingual children’s language acquisition. These factors are of three types: child-internal (i.e., age of first exposure to the majority language, cognitive abilities, and socioemotional well-being), distal external (i.e., HL literacy and education, family SES), and proximal external (i.e., quantity of input in the heritage and the majority languages, amount of HL use at home).

In this category, input quantity in the domestic environment emerges as a crucial variable. Indeed, the quantity of input is extremely difficult, if not impossible, to measure. Input quantity is rarely balanced within families, with one language usually prevailing. Understanding patterns of linguistic interaction within families is crucial for researching home language use and its impact on bilingual development in heritage speakers. Do family interactions predominantly occur in the HL, in L2, or involve language mixing? Some authors suggest that larger HL exposure at home is associated with children’s higher scores in HL (e.g., He et al. 2020; Hoff 2018). However, other researchers doubt that unbalanced input quantity is the key factor, suggesting that even a minor exposure might ensure HL (Arnaus Gil et al. 2021; Quay 2008). Caloi and Torregrossa (2021) rather introduce the importance of “consistency”, i.e., using the same strategy of home language use over the years and “continuity”, i.e., exposure to HL between home and school.

Furthermore, the impact of language choices may vary according to the persons with whom these interactions happen (e.g., Hammer et al. 2012; Rojas et al. 2016). Indeed, differential effects have been found when the heritage and the majority language are spoken with the mother, father, or siblings. Soto-Corominas et al. (2022) found that for Syrian refugee children, exposure to English as a second language with siblings was positively related to L2 competence but did not affect the performance in HL Arabic; instead, cumulative exposure rather than current input in the HL by parents influence HL.

Another important aspect to consider is the quality of input children receive (Arnaus Gil et al. 2021; Pearson et al. 1997). As for the HL, input quality refers to the diversity and complexity of a child’s language experience through specific activities and interactions at home (e.g., interactive book sharing, language games, and maternal responses during these activities) (Paradis 2023) and in the social environment (Barnes 2011; Dewaele 2000; Dewaele 2007; Hoffmann 1985; Maneva 2004; Quay 2001). Even if quality cannot be wholly separated from quantity because good interactions which occur rarely have reduced impact (e.g., De Houwer 2018), it has been proved that language richness positively affects bilingualism and emergent literacy development in preschoolers (e.g., Hammer et al. 2009; Unsworth et al. 2019). In sum, input quality at home is vital in determining HL acquisition (e.g., He et al. 2020) as much as input quantity.

As for both quantity and quality, parent proficiency and parental discourse style in the HL can explain children’s degree and type of language knowledge (Chevalier 2015; Quay 2011). Input from less proficient parents is different from that provided by proficient parents. Also, further intervening variables in multilingual families are related to socioeconomic status (SES) and the status (prestige or disregard) of the languages involved in the immediate environment (Barron-Hauwaert 2000; Faingold 1999, 2017; Hoffmann and Stavans 2007; Wang 2008).

More generally, Kupisch and Rothman (2018) argue that heritage grammars, unlike those of monolinguals (i.e., L1 speakers of the heritage language), differ because heritage speakers are primarily exposed to the heritage language within their home environment. This influences both input quantity and quality because the HL is often in competition with the majority language in daily uses (reduced input quantity) and possibly spoken by family members who themselves have limited exposure to their L1 and are experiencing phenomena of (local) language loss (‘diverse’ input quality).

Finally, several studies have underlined how a more positive attitude towards multilingualism is associated with higher input rates and better input quality (e.g., Pérez-Leroux et al. 2011; Altman et al. 2014). On the counterpart, it has been shown that parents’ anxiety related to “monolingual mindset”, that is, the perception that monolingualism is the social norm, can be prevalent in multilingual, transcultural families due to ‘fixed monolingual mindsets’, negatively influencing multilingual language practices in and outside the family (Sevinç 2022).

To better grasp the parents’ attitudes and how they impact HL development, specific methodological choices are needed to grasp how opinions and perceptions influence FLPs—and possibly the young generations’ HL maintenance. Questionnaires to parents are usually the way through which FLPs have been explored. However, the investigation of the complex social and individual factors (ideologies, beliefs, etc.) that influence FLPs may benefit from a more personal and dialogical approach, able to capture better the specificities of every individual point of view (e.g., Cychosz et al. 2021).

1.3. The Present Study

The main aim of the present study is to explore the effects of FLPs on children’s heritage language skills in multilingual children exposed to Italian as a societal language. Specifically, we examine how parents’ language choices and beliefs about multilingualism influence children’s HL proficiency, focusing on receptive vocabulary and morphosyntactic comprehension.

We hypothesized that family language practices and management (i.e., two of the three factors which shape FLPs) influence these dimensions (e.g., King et al. 2008). More in detail, we expected that speaking the HL alone or simultaneously with Italian may have resulted in higher scores for children in their HL concerning receptive vocabulary skills and morphosyntactic comprehension. Secondly, we hypothesized that parents’ valuing of HL (i.e., the third dimension influencing FLPs) influences their children’s HL development through beliefs and ideologies (e.g., Curdt-Christiansen and Wang 2018). Finally, measures assessing both language exposure and perceived value will allow disentangling the differential role of these variables. Given the paucity of evidence in previous literature that included both language use and perceived value, this is considered an exploratory aim.

Most studies focused on the impact of FLPs on multilingual children’s L2, while results concerning the impact of FLPs on children’s HL are multifaceted and need further exploration (Paradis 2023; Caloi and Torregrossa 2021). To disambiguate the role that FLPs play in HL, we used a multi-method approach that combines qualitative and quantitative analysis from both the linguistics and psychological methodologies. Considering both perspectives may help address the complexity of multilingualism, not only in terms of proficiency levels but also in its broader social context (as in Altinkamis and Simon 2020).

2. Method

2.1. Participants

At first, 450 families of 4–5-year-old children (M = 4.71, ds = 0.56) attending 20 infancy schools in Bologna (Italy) were involved. They compiled an Italian version of the Language and Social Background Questionnaire (LSBQ, Anderson et al. 2018) to collect information about their sociolinguistic background.

Based on the LSBQ results, we selected 81 multilingual families that were involved in semi-structured interviews aimed at deepening their family language policies (8% of participants spoke Tagalog as their HL, 2% Trigrine, 2% Ukraine, 3% Urdu, 10% Albanian, 11% Arabian, 2% Bambara, 14% Bengali, 1% Chinese, 2% Creole, 1% Farsi, 2% French, 2% Greek, 3% English, 6% Moldovan, 2% Portuguese, 17% Romanian, 5% Russian, 1% Slovak, and 8% Spanish).

As a third phase, we administered their children individual tasks to quantify their proficiency in their HL. Fifty-three parents and their children were part of our final sample, based on the availability of the HLs within the BaBIL battery (Contento et al. 2013), which includes receptive vocabulary and morphosyntactic comprehension tasks in HLs (see below for tasks description). We opted for this task because it has been used in previous research on the evaluation of linguistic skills in heritage language, showing good discriminant validity between bilingual children with and without Developmental Language Disorder (Bonifacci et al. 2020). Other available instruments, such as the Peabody Picture Vocabulary test (Dunn and Dunn 1981), do not include morphosyntactic comprehension and might be culturally and linguistically biased for vocabulary assessment in heritage language multilingual speakers (Goriot et al. 2021). Also, parents’ reports, such as the MacArthur–Bates Communicative Development Inventories (CDI, Fenson et al. 2006) available in many of the languages included in this study, were excluded because the CDI is suggested for parents of children who are not older than 37 months. Further, the CDI is an indirect measure, whereas in the present study, we wanted to combine parents’ interviews with a direct assessment of children’s linguistic skills in their HL.

2.2. Materials and Procedure

2.2.1. Parents

Semi-structured interviews. Parents were administered semi-structured interviews to explore their FLPs (beliefs, ideologies, practices, and language management) and their emotional perception of languages, linguistic usages and learning contexts. Each interview lasted approximately 30 min and was held online via the Teams platform. If present, both parents were involved contemporarily. Italian has been chosen as a preferential language, but experimenters were also available to speak in English, French or Spanish if necessary.

The interview transcripts were analyzed thematically (Braun and Clarke 2006) using NVivo (Dhakal 2022). At first, the so-called ‘Grounded Theory Method’ was used (e.g., Bryant and Charmaz 2007), so that—apart from the inevitable influence of the aims of this study—it was the systematic analysis of the participants’ words—rather than the need to test a given hypothesis—to lead to the definition of specific conceptual categories. The parents’ statements were coded through several rounds of analysis by one of the authors and an additional annotator, regardless of the specific question participants were answering. We reported as “0” when a specific issue was not present within the discourses of the family and “1” when it was addressed at least once. This bottom-up approach paved the way for a more focused analysis, as the interviewees’ accounts about HL were merged to identify general trends within and across families. This concerned both the HL perceived value (conceived as beliefs and ideologies potentially shaping FLPs) and the amount of HL use in the domestic context, including actions undertaken to influence HL maintenance (these two corresponding to FLP language practices and management). To this end, we summed issues based on the bottom-up categorization in macro-categories, which helped grasp each family’s overall relationship with their HL (see Table 1 for a list of the categories extracted from the parental interviews and related examples, and Table 1b for number of occurrences for each micro-category). Scores higher than 1 were possible if parents reported the same issue on more than one thematic unit. An example of occurrences that compose one of the micro-categories, namely Parents with positive relation with HL, is: the importance of the HL comparable to Italian and English + HL associated with cultural enrichment and open-mindedness + HL associated with future because of work environment and internationalization + positive role of HL in general + HL promotes cognitive development + HL as an advantage to learn other languages.

Table 1.

(a) Categories extracted from the parental interviews.1 (b) Occurrences for every micro-category extracted from the parental interviews.

2.2.2. Children

The BaBIL battery (Contento et al. 2013; see Bonifacci et al. 2020 for a more in-depth task description). The BaBIL battery provides information on bilingual profiles via four receptive tasks given in both L1 and L2. For the present study—only the version in L1 of vocabulary and morphosyntactic tasks were administered. Every child has been involved in an individual session within school time. The whole session lasted approximately 30 min, including a short break between tasks. Both tasks were administered through a MacBook laptop (13-inch screen). Every child and the experimenter were sitting in a comfortable and silent room provided by the school. For each task, each item was scored 1 for correct response and 0 for incorrect responses. The task was developed in Italian and in many different minority (for the Italian context) languages (e.g., Arabic, Albanian, Twi, Tagalog, Romanian, Bengali, and Chinese). The adaptation into different languages was conducted through the involvement of native speakers who translated the stimuli and gave their contributions regarding the cultural and linguistic adjustments needed. For example, in the Arabic (Moroccan) version, the item with the word “basket” (سلة) was replaced with “bucket” (دلو) because it has been suggested that basket in Arabic was longer and less frequent compared to the second. There was, however, a limited number of linguistic adjustments (0 to 3 changes for each language on the entire task). Cronbach’s alpha for the whole test is 0.86, as reported in the test manual.

- Receptive vocabulary task. Children were asked to carefully listen to 20 words in their HL, one at a time. After every word, they were presented with four images and had to decide which represented the word they listened to by pointing it on the screen. For example, the child listens to the word “feather” (in the HL) and sees four images (a feather, a puma, a duvet, a bird) on the computer screen. The choice of words, which includes objects and animals (e.g., drum, shark), was based on an age of acquisition below 4.5 years for Italian (Burani et al. 2001). On the score sheet, the examiner notes down the answer given by the child and checks if it is correct. The score on this task was obtained by summing up the correct responses (M score = 9.16, ds = 3.89).

- Morphosyntactic comprehension task. Children were asked to carefully listen to 20 sentences in their HL, one at a time. The task includes the assessment of diverse grammar structures: articles, pronouns, prepositions, adverbs, adjectives, and verb agreement. Some examples are “Show me the image that shows more pens” and “There are no apples in the basket”. After every sentence, they were presented with four images and had to decide which represented the sentence they listened to by pointing it on the screen. The score on this task was obtained by summing up the correct responses (M score = 10.51, ds = 4.88).

3. Results

3.1. Data Planning

The analyses were run through RStudio (RStudio Team 2020, Version 2023.09.1+494).

Correlation analysis (Hmisc package, Harrell 2023).

At first, we ran a correlation analysis to select the variables to be inserted in our model to control for multicollinearity (as in Kraha et al. 2012).

Multivariate regression analysis (lme4 package, Bates et al. 2015).

As a main analysis, we ran a multivariate regression analysis to explore the effect of FLPs on children’s HL skills. The receptive vocabulary and morphosyntactic comprehension tasks were inserted as dependent variables. The families’ prevailing use of HL, Italian, or a combination of HL and Italian at home were inserted as main predictors, together with their overall positive vs. negative attitudes and perceived values towards multilingualism.

3.2. Main Results

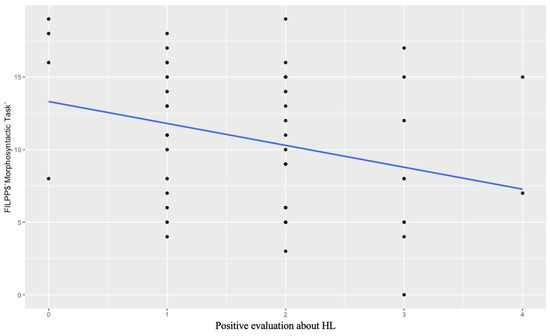

Concerning receptive vocabulary as the dependent variable, the families’ positive evaluation of multilingualism resulted significantly in determining children’s scores (p < 0.05), with a positive estimate (β = 0.639), meaning that the more positive values associated with HL and multilingual uses, the better children develop their vocabulary skills in HL (see Figure 1). On the contrary, the prevalent use of the HL in the domestic context per se does not seem to affect children’s receptive vocabulary performance (p = 0.711) (see Table 2 for extensive results concerning receptive vocabulary task as dependent variable).

Figure 1.

Role of parents’ positive evaluation of heritage language (HL) on children’s receptive vocabulary scores.

Table 2.

Receptive vocabulary task as the dependent variable.

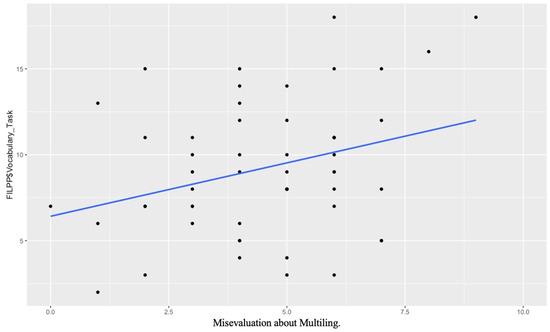

Concerning morphosyntactic comprehension as dependent variable, the misevaluation of multilingualism resulted in a trend towards significance (p = 0.06), with a negative estimate (β = −1.30344), meaning that the worse idea parents have about their being multilingual, the worse children perform in terms of morphosyntactic comprehension in their HL (see Figure 2). Moreover, the language choices held by the parents do not seem to affect children’s morphosyntactic comprehension skills (usage of HL: p = 0.338; usage of Italian: p = 0.453; usage of both languages: p = 0.954) (see Table 3 for extensive results concerning morphosyntactic comprehension as dependent variable).

Figure 2.

Role of parents’ misevaluation about multilingualism on children’s morphosyntactic comprehension scores.

Table 3.

Morphosyntactic comprehension task as dependent variable.

4. Discussion

The present study aimed to investigate how family language practices (FLPs) affect children’s language acquisition. More specifically, we aimed to address how parents’ language choices, beliefs and ideologies concerning multilingualism may influence children’s mastery of their HL.

To achieve this, parents participated in semi-structured interviews to discuss their FLPs. Two broad dimensions were considered and extracted from the interviews as FLPs, namely the linguistic usage at home (i.e., if parents speak the HL, if they speak Italian or both the languages) and the value attributed to multilingualism (i.e., positive attitude towards multilingualism or misevaluation about multilingualism).

The children completed two tasks in their HL: one to enhance their receptive vocabulary skills and the other to assess their morphosyntactic comprehension.

Our first hypothesis was that family language practices may impact these dimensions. Specifically, we hypothesized that children from families with greater reported HL usage would demonstrate stronger vocabulary and morphosyntactic comprehension skills in HL. However, our results suggest that HL usage, as reported by parents in interviews, does not significantly affect children’s HL skills, including vocabulary and morphosyntactic comprehension. These results contrast with previous studies that reported a positive association between HL exposure in the family context and children’s linguistic skills (for an overview, see Paradis 2023). For example, Pham and Tipton (2018) found that parental use of Vietnamese contributed to children’s Vietnamese vocabulary. However, Bello et al. (2023) reported that children’s HL expressive vocabulary was mainly predicted by the child’s output (active usage of HL in responding to parents) rather than by parental input (parents spoke to the child in HL) and by the parental use of interactive practice (e.g., listening to songs and telling stories). In addition, Lindgren and Bohnacker (2022) did not find an effect of language exposure on Swedish-German bilingual preschoolers’ narrative skills. Other researchers highlighted that in plurilingual families even a minor exposure might ensure HL maintenance (Arnaus Gil et al. 2021; Quay 2008)

As De Houwer (2018) pointed out, language input in bilingual families varies dynamically. Different parameters can be adopted, including the timing of exposure, the cumulative and absolute frequency of language input, the quality of input (e.g., parental competence), who gives the input (parents, sibling, formal instruction), as well as interactions in the social environment (Barnes 2011; Dewaele 2000, 2007; Hoffmann 1985; Maneva 2004; Quay 2001). Also, different collection tools are reported in the literature, including parent questionnaires, interviews, and diaries or direct observation of input quantity and quality in everyday life through various types of interactional analysis. In this regard, some authors reported discrepancies between parental-reported language choice in speaking to their children and parents’ observed input (Goodz 1989; De Houwer and Bornstein 2016; Marchman et al. 2016).

The study results should be interpreted within the context of the methodology used: parental interviews focused on self-reported FLPs. This methodology was meant to grasp how parents manage language choices within the family as well as how they make sense of such choices. As for the former, we analyzed how often they refer to language usage in everyday life considering HL, Italian and both languages. While this type of data cannot be directly compared to more structured parent reports or direct observations, they might be informative in the way they suggest that language usage per se, according to parents’ interviews, is not predictive of children’s skills in HL. Concerning the latter, the perceived positive value of HL, interestingly, unlike language usage, it proved to be significantly related to effective children’s HL acquisition. More in detail, a positive value attributed to HL within the family context proved to significantly impact children’s receptive vocabulary skills in their HL.

Furthermore, the parents’ perception that their HL is misevaluated in the societal context has a negative impact on children’s morphosyntactic comprehension skills. These results seem to be in line with what was reported by (Sevinç 2022) regarding the negative effects on children’s HL of parents’ anxiety due to ‘fixed monolingual mindsets’ influenced by societal factors.

We want to highlight that the two broad FLP dimensions considered differ, i.e., positive evaluation of HL and misevaluation of HL. The first is a mix of parental attribution to other’s opinions and their own opinions. On the contrary, the misevaluation variable encompasses the parents’ perception of HL usage by the school and the context in which they live. Even if these attributions partially differ and may shed light on slightly different aspects, they all refer to parents’ ideologies and beliefs and seem more powerful in determining children’s HL skills than usage per se.

These results underscore the psychological and social implications of language development and acquisition for bilinguals. Indeed, how people experience being bilinguals is deeply shaped by the system in which the individual is enclosed, that is, his or her family in principle. In turn, this family is deeply rooted and shaped by an idea about what the society they live in may think about their multilingualism. We can speculate that parents who perceive a positive value regarding their HL, either at an individual level or in the societal context, can transmit higher motivation and ease in using that language to their children. This, in turn, might positively affect their HL maintenance and competence. This was particularly the case of increased vocabulary in HL, possibly related to an increased attitude by parents and children in naming activities in HL.

On the counterpart, those who speak HL in everyday life but perceive a misevaluation of this language by society (e.g., teachers suggest not to use HL at home) may convey a negative feeling towards this language, and the child might be less prone to HL usage. We did not address the evaluation of children’s perspectives, but it might be that children themselves perceive negative feedback from the societal context regarding their HL. We found specific effects on morphosyntactic comprehension, which may suggest that a misevaluation of HL might make linguistic interactions less rich in syntactic complexity. However, further studies should better investigate the effects of perceived language value on different domains of language competence.

5. Conclusions

This study provides insights into how parents’ attitudes toward HL shape their children’s linguistic development in HL. As suggested by De Houwer (2018), language usage is strictly connected with the specific sociocultural power constellations in the society where children and their families live. Also, as Paradis (2023) suggested, emotional and motivational factors (i.e., socioemotional well-being according to her model) and parents’ attitudes need to be considered in research addressing bilingual development. Therefore, the present study can be framed within a more holistic approach to language input that, according to De Houwer (2018), needs to consider language-related power issues.

This study has some limitations that need to be accounted for and might limit the generalization of the results. First, as already mentioned, measures of language usage are partially different from those used in other studies and derive from qualitative and quantitative analyses of parents’ interviews. These results could, therefore, be expanded with direct measurements of the quality and quantity of the language input. Also, comparisons between parents’ accounts and their language behaviors are necessary in future studies. Secondly, interviews were coded based on a bottom-up approach that led to identifying macro-categories. A different coding approach based on top-down extraction of thematic units which isolate the intended phenomena might be a promising approach in future research. For example, clustering the parents’ accounts according to the FLP dimensions (practices, beliefs and ideologies, management) from the beginning and, for each category, assuming a pre-established annotation schema (e.g., for beliefs and ideologies, a scale going from “HL valuing” to “HL devaluing”). Finally, a more detailed analysis of contextual factors not directly addressed in the present study (i.e., socioeconomic status, parental activities in the home context, such as shared book reading, etc.) would allow us to understand better the complex interaction between environmental factors and bilingual language development.

Despite these limitations, the evidence of the role of perceived language value in relation to children’s HL skills represents an original contribution with respect to previous literature and might represent an intriguing perspective for future research. The present study might also have implications for educational policies, reinforcing the idea that a positive attitude towards HL might help children (and their families) in the active maintenance of HL and this, in turn, as suggested by (Scalise et al. 2021) might have positive effects on later language learning at school.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, P.B. and C.B.; methodology, C.B., M.C. and P.B.; formal analysis, M.C.; investigation, M.C.; resources, M.C.; data curation, M.C., C.B. and P.B.; writing—original draft preparation, M.C.; writing—review and editing, M.C., C.B. and P.B.; supervision, C.B. and P.B.; funding acquisition, C.B. and P.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the University of Bologna, Almaidea 2022.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Bologna (protocol code 0250367, 17 October 2022.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from both parents of the children involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy issues.

Acknowledgments

We thank Comune di Bologna, Area Educazione, Istruzione e Nuove Generazioni for the support in contacting and recruiting participants. We also thank Rebecca Cerretti, Giulia Chessa, Alessia Paglino, Ilaria Ricci, and Camilla Santoni for their contribution to data collection and transcription. Finally, thanks to Irene Parisotto for her work on data coding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Note

| 1 | Each example provided in Table 1 is anticipated by the family code (e.g., 27GLRV) and the speaker (‘M’ = ‘mother’; ‘F’ = ‘father’). A word needs to be said about the translation of the extracts selected for inclusion in the present article. The transcriptions were analyzed in the original language(s) participants used. This was mostly Italian, with occasional switch to English. The participants’ level of Italian was varied, with some being relatively proficient, while others struggled to make themselves understood. Once the extracts to be quoted were selected, we translated them into English. However, this procedure required a number of choices. For example, the morpho-syntactic mistakes made by the parents did not always have an equivalent in English, in which case similar types of errors were chosen in order to convey an analogous level of language proficiency. |

References

- Altinkamis, Feyza, and Ellen Simon. 2020. Language abilities in bilingual children: The effect of family background and language exposure on the development of Turkish and Dutch. International Journal of Bilingualism 24: 931–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, Carmit, Zhanna Burstein-Feldman, Dafna Yitzhaki, Sharon Armon-Lotem, and Joel Walters. 2014. Family language policies, reported language use and proficiency in Russian–Hebrew bilingual children in Israel. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 35: 216–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, Jhon, Lorinda Mak, Aram Keyvani Chahi, and Ellen Bialystok. 2018. The language and social background questionnaire: Assessing degree of bilingualism in a diverse population. Behavior Research Methods 50: 250–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnaus Gil, Laia, Natascha Müller, Nadine Sette, and Marina Hüppop. 2021. Active bi- and trilingualism and its influencing factors. International Multilingual Research Journal 15: 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, Kim. 2011. On Language: A Short Meditation. In West of 98. Edited by Stegnen Lynn and Rowland Russell. Austin: University of Texas Press, pp. 226–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barron-Hauwaert, Suzanne. 2000. Issues surrounding trilingual families: Children with simultaneous exposure to three languages. Zeitschrift für Interkulturellen Fremdsprachenunterricht 5: 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Bates, Douglas, Martin Mächler, Steve Walker, and Ben Bolker. 2015. Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software 67: 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, Arianna, Paola Ferraresi, Maria Cristina Caselli, and Paola Perucchini. 2023. The Predictive Role of Quantity and Quality Language-Exposure Measures for L1 and L2 Vocabulary Production among Immigrant Preschoolers in Italy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20: 1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonifacci, Paola, Elena Atti, Martina Casamenti, BarbaraPiani, Marina Porrelli, and Rita Mari. 2020. Which measures better discriminate language minority bilingual children with and without developmental language disorder? A study testing a combined protocol of first and second language assessment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 63: 1898–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3: 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, Antony, and Khaty Charmaz. 2007. Introduction. Grounded Theory Research: Methods and practices. In The SAGE Handbook of Grounded Theory. Edited by Antony Bryant and Khaty Charmaz. Thousand Oaks: Sage, pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Burani, Cristina, Laura Barca, and Lisa Saskia Arduino. 2001. Una base di dati sui valori di età di acquisizione, frequenza, familiarità, immaginabilità, concretezza, e altre variabili lessicali e sublessicali per 626 nomi dell’italiano. Giornale Italiano di Psicologia 28: 839–56. [Google Scholar]

- Caloi, Irene, and Jacopo Torregrossa. 2021. Home and School Language Practices and Their Effects on Heritage Language Acquisition: A View from Heritage Italians in Germany. Languages 6: 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevalier, Sarah. 2015. Trilingual Language Acquisition: Contextual Factors Influencing Active Trilingualism in Early Childhood. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contento, Silvana, Stephanie Bellocchi, and Paola Bonifacci. 2013. BaBIL. Prove per la valutazione delle competenze verbali e non verbali in bambini bilingui. Firenze: Giunti-Edu. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. 2016. Guide for the Development and Implementation of Curricula for Plurilingual and Intercultural Education. Strasbourg: Council of Europe. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. 2020. Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment-Companion Volume. Strasbourg: Council of Europe. [Google Scholar]

- Curdt-Christiansen, Xiao Lan. 2009. Invisible and visible language planning: Ideological factors in the family language policy of Chinese immigrant families in Quebec. Language Policy 8: 351–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curdt-Christiansen, Xiao Lan. 2018. Family language policy. In The Oxford Handbook of Language Policy and Planning. Oxford: Oxford Academic, pp. 420–41. [Google Scholar]

- Curdt-Christiansen, Xiao Lan. 2022. Family language policy and school language policy: Can the twain meet? International Journal of Multilingualism 19: 466–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curdt-Christiansen, Xiao Lan, and Weihong Wang. 2018. Parents as agents of multilingual education: Family language planning in China. Language, Culture and Curriculum 31: 235–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cychosz, Margaret, Anele Villanueva, and Adriana Weisleder. 2021. Efficient estimation of children’s language exposure in two bilingual communities. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 64: 3843–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Houwer, Aannick. 2018. Chapter 7. The role of language input environments for language outcomes and language acquisition in young bilingual children. In Bilingual Cognition and Language. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp. 127–54. [Google Scholar]

- De Houwer, Annick, and Marc Bornstein. 2016. Bilingual mothers’ language choice in child-directed speech: Continuity and change. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 37: 680–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dewaele, Jean-Marc. 2000. Trilingual first language acquisition: Exploration of a linguistic « miracle ». La Chouette 31: 77–86. [Google Scholar]

- Dewaele, Jean-Marc. 2007. Predicting Language Learners’ Grades in the L1, L2, L3 and L4: The Effect of Some Psychological and Sociocognitive Variables. International Journal of Multilingualism 4: 169–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhakal, Kerry. 2022. NVivo. Journal of the Medical Library Association: JMLA 110: 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, Lloyd, and Leota Dunn. 1981. Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test-Revised. St Paul: American Guidance Service, Incorporated. [Google Scholar]

- Faingold, Eduardo. 1999. The Re-emergence of Spanish and Hebrew in a Multilingual Adolescent. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 2: 283–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faingold, Eduardo. 2017. Pro-active attitudes and education strategies in early trilingual acquisition: Referential avoidance and parental intervention at the one-word stage. Estudios de Lingüística Aplicada 32: 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenson, Lerry, Virginia Marchman, Donna Thal, Philip Dale, Steven Reznick, and Elizabeth Bates. 2006. MacArthur-Bates Communicative Development Inventories, Second Edition (CDIs). [Database Record]. Washington, DC: APA PsycTests. [Google Scholar]

- García, Ofelia. 2005. Positioning heritage languages in the United States. Modern Language Journal 89: 601–5. [Google Scholar]

- Goodz, Naomi. 1989. Parental language mixing in bilingual families. Infant Mental Health Journal 10: 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goriot, Claire, Roeland van Hout, Mirjam Broersma, Vanessa Lobo, James McQueen, and Sharon Unsworth. 2021. Using the peabody picture vocabulary test in L2 children and adolescents: Effects of L1. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 24: 546–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, Carol, Eugene Komaroff, Barbara Rodriguez, Lisa Lopez, Shelley Scarpino, and Brian Goldstein. 2012. Predicting Spanish–English bilingual children’s language abilities. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 55: 1251–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammer, Carol, Megan Davison, Frank Lawrence, and Adele Miccio. 2009. The effect of maternal language on bilingual children’s vocabulary and emergent literacy development during Head Start and kindergarten. Scientific Studies of Reading 13: 99–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrell, Frank, Jr. 2023. Hmisc: Harrell Miscellaneous. R Package Version 5.1-0. Available online: https://hbiostat.org/R/Hmisc/ (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- He, Sun, Siew Ng, Beth O’Brien, and Ton Fritzsche. 2020. Child, family, and school factors in bilingual preschoolers’ vocabulary development in heritage languages. Journal of Child Language 47: 817–43. [Google Scholar]

- Hoff, Erika. 2018. Bilingual development in children of immigrant families. Child Development Perspectives 12: 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, Charlotte. 1985. Language acquisition in two trilingual children. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 6: 479–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, Charlotte, and Anat Stavans. 2007. The evolution of trilingual codeswitching from infancy to school age: The shaping of trilingual competence through dynamic language dominance. International Journal of Bilingualism 11: 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollebeke, Ily, Esly Struys, and Orhan Agirdag. 2023. Can family language policy predict linguistic, socio-emotional and cognitive child and family outcomes? A systematic review. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 44: 1044–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, Kendall, Lyn Fogle, and Aubrey Logan-Terry. 2008. Family language policy. Language and Linguistics Compass 2: 907–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraha, Amanda, Heather Turner, Kim Nimon, Linda Zientek, and Robin Henson. 2012. Tools to support interpreting multiple regression in the face of multicollinearity. Frontiers in Psychology 3: 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kupisch, Tanja, and Jason Rothman. 2018. Terminology matters! Why difference is not incompleteness and how early child bilinguals areheritage speakers. International Journal of Bilingualism 22: 564–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindgren, Josefin, and Ute Bohnacker. 2022. How do age, language, narrative task, language proficiency and exposure affect narrative macrostructure in German-Swedish bilingual children aged 4 to 6? Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism 12: 479–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maneva, Blagovesta. 2004. ‘Maman, je suis polyglotte!’: A Case Study of Multilingual Language Acquisition from 0 to 5 Years. International Journal of Multilingualism 1: 109–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchman, Virginia, Lucìa Martínez, Nereyda Hurtado, Theres Grüter, and Anne Fernald. 2016. Caregiver talk to young Spanish-English bilinguals: Comparing direct observation and parent-report measures of dual-language exposure. Developmental Science 20: e12425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montrul, Silvina, and Maria Polinsky. 2021. Introduction: Heritage languages, heritage speakers, heritage linguistics. In The Cambridge Handbook of Heritage Languages and Linguistics. Edited by Silvina Montrul and Maria Polinsky. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Paradis, Johanne. 2023. Sources of individual differences in the dual language development of heritage bilinguals. Journal of Child Language 50: 793–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, Barbara, Sylvia Fernandez, Vanessa Lewedeg, and Kimbrough Oller. 1997. The relation of input factors to lexical learning by bilingual infants. Applied Psycholinguistics 18: 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedley, Malika, and Alain Viaut. 2019. What do minority languages mean? European perspectives. Multilingua 38: 133–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Leroux, Ana, Alejandro Cuza, and Danielle Thomas. 2011. Input and parental attitudes: A look at Spanish–English bilingual development in Toronto. In Bilingual youth: Spanish in English-Speaking Societies. Edited by Kim Potowski. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 149–75. [Google Scholar]

- Pham, Giang, and Timothy Tipton. 2018. Internal and external factors that support children’s minority first language and English. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools 49: 595–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quay, Suzanne. 2001. Managing linguistic boundaries in early trilingual development. In Trends in Bilingual Acquisition. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. Available online: https://www.jbe-platform.com/content/books/9789027294814-tilar.1.09qua (accessed on 20 January 2024).

- Quay, Suzanne. 2008. Dinner conversations with a trilingual two-year-old: Language socialization in a multilingual context. First Language 28: 5–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quay, Suzanne. 2011. Trilingual toddlers at daycare centres: The role of caregivers and peers in language development. International Journal of Multilingualism 8: 22–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, Raul, Aquiles Iglesias, Ferenc Bunta, Brian Goldstein, Claude Goldenberg, and Leslie Reese. 2016. Interlocutor differential effects on the expressive language skills of Spanish-speaking English learners. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology 18: 166–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- RStudio Team. 2020. RStudio: Integrated Development for R. RStudio. Boston: PBC. Available online: http://www.rstudio.com (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Scalise, Elena, Johanna Stahnke, and Natascha Müller. 2021. Parameter setting and acceleration: Subject omissions in a trilingual child with special reference to French. Language, Interaction and Acquisition 12: 157–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroedler, Tobias, Judith Purkarthofer, and Kathia Cantone. 2022. The prestige and perceived value of home languages. Insights from an exploratory study on multilingual speakers’ own perceptions and experiences of linguistic discrimination. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, Mila. 2008. Exploring the relationship between family language policy and heritage language knowledge among second generation Russian-Jewish immigrants in Israel. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 29: 400–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, Mila. 2010. Family language policy: Core issues of an emerging field. Applied Linguistics Review 1: 171–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevinç, Yesim. 2022. Mindsets and family language pressure: Language or anxiety transmission across generations? Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 43: 874–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Corominas, Adriana, Evangelia Daskalaki, Johanne Paradis, Magdalena Winters-Difani, and Redab Janaideh. 2022. Sources of variation at the onset of bilingualism: The differential effect of input factors, AOA, and cognitive skills on HL Arabic and L2 English syntax. Journal of Child Language 49: 741–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spolsky, Bernard. 2004. Language Policy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Suarez, Debra. 2002. The paradox of linguistic hegemony and the maintenance of Spanish as a heritage language in the United States. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 23: 512–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Templin, Torsten, Andrea Seidl, Bengt-Arne Wickström, and Gustav Feichtinger. 2016. Optimal language policy for the preservation of a minority language. Mathematical Social Sciences 81: 8–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unsworth, Sharon, Susanne Brouwer, Elise de Bree, and Josje Verhagen. 2019. Predicting bilingual preschoolers’ patterns of language development: Degree or non-native input matters. Applied Psycholinguistics 40: 1189–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Xiao-lei. 2008. Growing up with Three Languages. Bristol: Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).