Abstract

In this paper I investigate the ne…ne construction in Turkish, illustrated by Ne Ali ne (de) Esra geldi ‘Neither Ali nor Esra arrived’. The meaning of the ne…ne construction roughly corresponds to the meaning of the neither…nor construction in English, but the syntactic properties of ne…ne are somewhat different from those of neither…nor. I focus on two such differences: one, the fact that ne…ne can, although it doesn’t have to, be accompanied by a negated verb; in fact, a negated verb is slightly dispreferred by speakers (but the presence versus the absence of negation interacts in interesting ways with negative concord); and two, the fact that the ne…ne construction cannot be embedded under a wide-scope question particle –mI except when the verb is negated.

1. Introduction1

Turkish has a number of correlative (or reduplicated) conjunctions, including the enumerating hem…hem… ‘not only… but also’, dA…dA ‘both’, the alternative ya…ya… ‘either…or’, and the negative ne…ne… ‘neither…nor’. In all of these constructions except in dA…dA ‘both’, the conjunctive particle (hem, ya, ne) precedes each coordinand and in all cases, the last instance of the particle is optionally followed by an emphatic (highlighting) particle –dA, as shown in (1).2

| 1. | a. | Hem sinema-ya | git-miş (...) | hem (de) | biraz | gez-miş-ti-m. |

| and cinema-dat | go-perf | and dA | a.little | go.around-perf-past-1sg | ||

| ‘I had both gone to the cinema and walked around a bit.’ | ||||||

| (Göksel and Kerslake 2005, p. 458) | ||||||

| b. | Ya Ahmet | ya siz | ya (da) ben | hazırlık-lar-a | gönüllü | katıl-malı-yız. | |

| or Ahmet | or you.pl | or dA I | preparation-pl-dat | voluntarily | join-must-1pl | ||

| ‘Either Ahmet or you or I must volunteer for the preparations.’ | |||||||

| (Göksel and Kerslake 2005, p. 121) | |||||||

| c. | Ne | Hasan | iş-e | git-ti, | ne (de) | Ali çarşı-ya | çık-tı. | |

| neither | Hasan | work-dat | go-past.3sg | nor dA | Ali market-dat | go.out-past.3sg | ||

| ‘Neither did Hasan go to work nor did Ali go shopping.’ | ||||||||

| (Kornfilt 1997, p. 111) | ||||||||

This paper focuses on the negative correlative conjunction ne…ne…. The meaning of the ne…ne… construction (NNC) roughly corresponds to the meaning of the neither…nor construction in English. However, unlike with neither…nor, the predicate of a sentence that contains an NNC can appear without a negation marker, as in (2a), or with it, as in (2b), without a change in meaning (Göksel 1987; Şener and İşsever 2003; Jeretič 2017, 2022). For ease of exposition, throughout the article, I will be using the term “affirmative” predicate for instances without the negation marker and the term “negative” predicate for instances with it.

| 2. | a. | Ne | Hasan ne | (de) | Mehmet okul-a | git-ti. | Affirmative pred. |

| ne | Hasan ne | dA | Mehmet school-dat | go-past.3sg | |||

| ‘Neither Hasan nor Mehmet went to school.’ | |||||||

| b. | Ne | Hasan ne | (de) | Mehmet okul-a | git-me-di. | Negative pred. | |

| ne | Hasan ne | dA | Mehmet school-dat | go-neg-past.3sg | |||

| ‘Neither Hasan nor Mehmet went to school.’ | |||||||

Interestingly, despite the fact that (2a) and (2b) mean exactly the same thing (at least truth-conditionally), their syntactic behavior differs in several respects. First, an NNC with an affirmative predicate in (2a) cannot be questioned, while the one with a negative predicate in (2b) can. This contrast is shown in (3a–b) below.

| 3. | a. | *Ne | Hasan ne | (de) | Mehmet okul-a | git-ti | mi? | Affirmative pred. |

| ne | Hasan ne | dA | Mehmet school-dat | go-past.3sg | q | |||

| Int. ‘Did neither Hasan nor Mehmet go to school?’ | ||||||||

| b. | Ne | Hasan ne | (de) | Mehmet okul-a | git-me-di | mi? | Negative pred. | |

| ne | Hasan ne | dA | Mehmet school-dat | go-neg-past.3sg | q | |||

| ‘Didn’t either Hasan or Mehmet go to school?’ | ||||||||

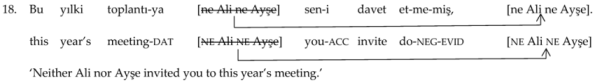

Second, only an NNC with a negative predicate allows the ne…ne… phrase to surface in a post-verbal position (Lewis 1967; Şener and İşsever 2003; Jeretič 2017, 2022). The relevant contrast is shown in (4a–b).

| 4. | a. | *Bu | yılki | toplantı-ya | sen-i | davet et-miş, | ne | Ali ne | Ayşe. | Affirmative pred. |

| this | year’s | meeting-dat | you-acc | invite do-evid | ne | Ali ne | Ayşe | |||

| Int. ‘Neither Ali nor Ayşe invited you to this year’s meeting.’ | ||||||||||

| b. | Bu | yılki | toplantı-ya | sen-i | davet et-me-miş | ne | Ali ne | Ayşe. | Negative pred. | |

| this | year’s | meeting-dat | you-acc | invite do-neg-evid | ne | Ali ne | Ayşe | |||

| ‘Neither Ali nor Ayşe invited you to this year’s meeting.’ | ||||||||||

Finally, the second conjunct alone together with the particle ne can appear post-verbally only when the predicate is not negated (Göksel and Kerslake 2005; Jeretič 2017, 2022), as shown in (5a–b).

| 5. | a. | Ne | Ali dans | et-ti, | ne | (de) Beste. | Affirmative pred. |

| ne | Ali dance | do-past.3sg | ne | dA Beste | |||

| ‘Neither Ali nor Beste danced.’ | |||||||

| b. | *Ne | Ali dans | et-me-di, | ne | (de) Beste. | Negative pred. | |

| ne | Ali dance | do-neg-past.3sg | ne | dA Beste | |||

| Int. ‘Neither Ali nor Beste danced.’ | (Jeretič 2017, p. 7) | ||||||

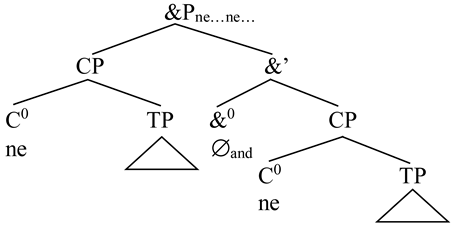

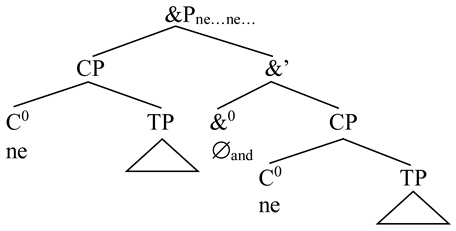

The aim of this paper is to account for the contrasts in (3)–(5). In a nutshell, I propose that an NNC involves a coordinate structure in which each coordinand is introduced by a ne particle. However, NNCs with affirmative predicates differ from NNCs with negative predicates in that the former are clausal coordinations and the latter are phrasal (non-clausal) coordinations. In my analysis this difference in the size of the ne-constituents, originally proposed by Jeretič (2017, 2022), dovetails with the nature of the ne particles, the position that they occupy, and the kind of coordination in which they appear. I propose that an NNC with an affirmative predicate is a conjunction of CPs, where each CP is headed by a genuinely negative complementizer ne, which needs no licensing by any other negative element in the structure. The schematic structure of a clausal NNC is shown in (6).

| 6. | The structure of a clausal NNC (affirmative predicate) |

|

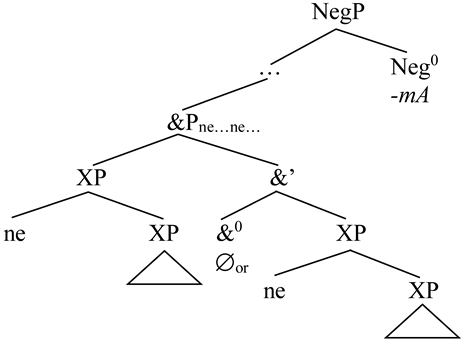

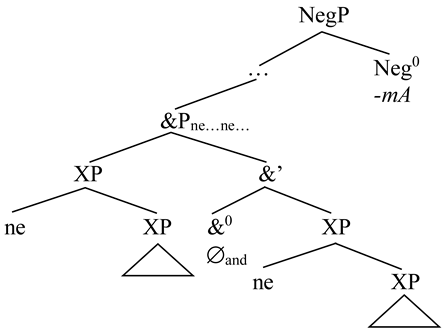

NNCs with negative predicates are typically smaller than CPs and do not contain negative complementizers. Instead, the ne particles that introduce each ne-phrase are Negative Concord Items (NCIs), which themselves do not carry negative force, but rather need a negation to license them. These particles are presumably adjoined to the constituent they introduce, as shown in (7). Additionally, the ne-phrases in non-clausal NNCs are disjoined, rather than conjoined, with the entire disjunction being c-commanded by the sentential negation.

| 7. | The structure of a non-clausal NNC (negative predicate) |

|

The paper is organized as follows: in Section 2, I present previous analyses of the ne…ne… construction. Section 3 presents my proposal, which derives the differences between NNCs with affirmative and negative predicates. Section 4 discusses data that remain unaccounted for under the proposed account and Section 5 is the conclusion.

2. Previous Analyses of the NNC

The ne…ne… construction has not been widely discussed in the literature. (Some of) the properties in (3)–(5) were mentioned/discussed by Gencan (1979) [as cited in Jeretič (2017, 2022) and Şener and İşsever (2003)], Göksel (1987), Şener and İşsever (2003), and Jeretič (2017, 2022). Here, I report the highlights of the analyses offered by Şener and İşsever (2003) and Jeretič (2017, 2022), both of which focus on conditions that determine the polarity of the predicate in the NNC.

2.1. Şener and İşsever’s (2003) Analysis of NNCs

Şener and İşsever (2003) discuss the NNC in Turkish from the point of view of the polarity of the predicate. In other words, their main aim is to account for the fact that the NNC may contain an affirmative and a negative predicate. Focusing on NNCs that occupy subject and object positions, the authors propose an analysis in terms of information structure; their main claim is that the presence versus the absence of negation on the predicate in an NNC depends on the presence or absence of focus on the ne…ne… phrase. They propose the following focusing conditions on the ne…ne… phrases:

| 8. | Focusing conditions on [ne…ne] phrases | (Şener and İşsever 2003, p. 1095) | |

| a. | If a ne…ne phrase is focused, the predicate must be morphologically affirmative; [if the predicate is morphologically affirmative, no element other than a ne…ne phrase can be focused […]] [F ne…ne] _ Vaff | ||

| b. | If the predicate is morphologically marked for negation, the ne…ne phrase cannot be focused. […] ne…ne_ [F Vneg] | ||

Şener and İşsever argue that, when it is associated with focus, a ne…ne… phrase becomes an effective negative category, licensed only in the preverbal field (given the fact that focused constituents cannot occupy a post-verbal position). They take focused ne…ne… phrases to be inherently negative and argue that such negative and focused ne…ne… phrases have to occupy the [Spec NegP] at LF (they move to NegP at LF), where they check their [+neg] and [+foc] features. The ne…ne… phrases that lack focus are treated as non-negative NPIs, which have to be licensed by sentential negation, just like hiç kimse ‘nobody/anybody’ or hiçbir ‘no/any’. This proposal derives the distribution of negated and non-negated predicates in NNCs.

Şener and İşsever do not discuss the structure of ne…ne… phrases; they represent them as ne[DP X-Y] in their diagrams, as expected given that they only take into consideration cases in which the NNC occupies either the subject or the object position.

2.2. Jeretič’s (2017, 2022) Analyses of NNCs

Like Şener and İşsever (2003), Jeretič (2017, 2022) also focuses on the conditions that force the predicate in a NNC to be affirmative or negative. Jeretič proposes that ne…ne… phrases in Turkish are n-words and that the ne…ne… phrase undergoes negative concord (NC) when the conjuncts are smaller than clauses (when they are non-propositional), and that it is exempt from NC when it coordinates clausal coordinands (when they are propositional). Thus, Jeretič argues for the generalization in (9).

| 9. | Generalization: | ||||

| a. | no Negative Concord ↔ ne..ne coordinates full clauses or, equivalently, | ||||

| b. | Negative Concord ↔ ne..ne coordinates constituents that are not full clauses.3 | ||||

| (Jeretič 2017, p. 5) | |||||

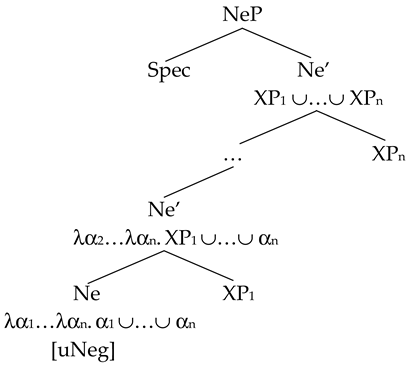

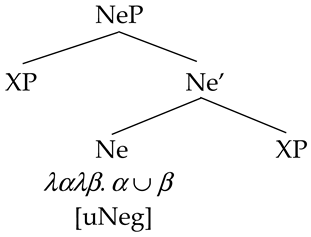

In order to derive this generalization, Jeretič adopts Zeijlstra’s (2004) analysis of NC, on which NC arises when multiple uninterpretable Neg features [uNeg] in the structure undergo Agree with a single instance of interpretable Neg feature [iNeg]. The two analyses, presented in Jeretič (2017) and Jeretič (2022), differ in how they derive the observed facts.

Jeretič (2017) proposes that [iNeg] is carried by a null negative operator Op¬ (whereas the negation head –mA carries an uninterpretable version of the same feature [uNeg]). As shown in (10), the ne…ne… phrase is also headed by a non-negative disjunction with an uninterpretable Neg feature [uNeg].

| 10. |

| Jeretič (2017, ex. 55) |

The [uNeg] feature on the ne…ne… phrase must agree with an instance of [iNeg]. This is the consequence of the Neg Criterion (Haegeman and Zanuttini 1991), of which Jeretič adopts a slightly revised version, given in (11).

| 11. | The revised Neg Criterion Jeretič (2017, p. 14) |

| a. Each [uNeg] must agree with an [iNeg] in the appropriate checking domain, | |

| b. Each [iNeg] must be in a Spec-Head relation with a [uNeg]. |

Jeretič (2017) further proposes that Op¬ in Turkish is strictly of type <t, t>; in other words, Op¬ can only merge with a phrase that is semantically a proposition. Given this restriction, Op¬ can only merge with the ne…ne… phrase when this phrase coordinates clauses. Since in this case, the [uNeg] feature of the ne…ne…phrase is checked by the [iNeg] feature of Op¬, satisfying both clauses of the Neg Criterion, there is no need for the structure to also contain sentential negation.

When the ne…ne… phrase coordinates conjuncts that are smaller in size, Op¬ cannot merge with it because of the type mismatch. In that case, the sentence must contain sentential negation (-mA), which also carries the [uNeg] feature, merged above the vP. Since NegP is of the type <t, t>, Op¬ can be merged into its specifier, and the derivation converges.

In Jeretič (2022) a ne…ne… phrase is, like before, analyzed as a disjunction, shown in (12), whose head carries a [uNeg] feature. This structure is assumed for both clausal and non-clausal disjunction, the difference lying only in the size of the disjuncts.

| 12. |

| Jeretič (2022, ex. 65) |

The analysis in Jeretič (2022) is significantly simplified compared to the (Jeretič 2017) version: it assumes that the negative marker –mA itself carries an interpretable Neg feature [iNeg], responsible for checking off the [uNeg] on non-clausal ne…ne… phrases. Clausal ne…ne… phrases, also headed by a non-negative disjunction head that carries a [uNeg] feature, cannot be embedded under a negation marker since the disjuncts are CPs and the negation marker takes vP, not CP, as its complement. Therefore, the [uNeg] feature carried by the disjunction head is checked off by the null negative operator Op¬, which can be merged in a projection above the CP, but only if a [uNeg] feature is present on the clausal spine. Since this is the case only when the ne…ne… phrase is clausal, but not when it is phrasal, Op¬ is only licensed in the former case.

Both of these analyses, Şener and İşsever (2003) and Jeretič (2017, 2022), focus on the external syntax of NNCs; they both develop an account of why an NNC can surface with both affirmative and negative predicates. Neither proposal is preoccupied with explaining the presence of a ne particle on each coordinand in an NNC: Şener and İşsever do not discuss this issue at all, Jeretič (2017, p. 19) assumes that the “particle ‘ne’ is the phonological realization of the left edge of each disjunct”, while Jeretič (2022, p. 1178) allows for this possibility, but also mentions that the ne particles might be “markers agreeing with a higher existential operator quantifying over the members of the coordination”, but in the end remains agnostic as to this issue.

Different from these analyses, my focus is on the internal syntax of NNCs; my primary aim is to show that NNCs with an affirmative verb have a different syntactic structure from NNCs with a negative verb and that diverging properties of the two follow from this difference. The analysis I present explains (to an extent) why NNCs with affirmative predicates have a ne particle on each of the ne…ne… phrases. This is because I propose that in such NNCs, the ne particles are the source of the negative semantics in each coordinand (see Section 3.2). The presence of the two ne particles in NNCs with negative predicates, however, remains unexplained by the analysis.4

3. Proposal

My analysis of Turkish NNCs rests on three ingredients, listed in (13).

| 13. | a. | The difference in the size of constituents in an NNC with an affirmative and with a negative predicate (following Jeretič 2017, 2022); |

| b. | The hypothesis that in NNCs with affirmative verbs, ne particles are negative complementizers, while in NNCs with negative verbs, they are Negative Concord Items (NCIs), adjoined to the constituent they introduce, and that they carry no negative force, but themselves need to be licensed by negation; | |

| c. | The hypothesis that NNCs with negative verbs are disjunctions embedded under negation | |

| (¬ (A ∨ B)), while NNCs with affirmative verbs are conjunctions of negatives (¬ A ∧ ¬ B)) (Wurmbrand 2008). |

In what follows, I elaborate each of these hypotheses and present evidence to support them.

3.1. Difference in the Size of the Conjuncts

I adopt from Jeretič (2017, 2022) the claim that in an NNC with an affirmative predicate, the constituents introduced by the two ne’s are clausal, whereas in an NNC with a negative predicate, the constituents introduced by the two ne’s are smaller in size. This proposal is a natural extension of the observation that in an NNC in which each ne overtly introduces a full clause, the predicate of each clause must be affirmative, as shown by the contrast in (14a–b).

| 14. | a. | Ne | Ali dans | et-ti, | ne | Beste | şarkı söyle-di. | Affirmative pred. |

| ne | Ali dance | do-past.3sg | ne | Beste | song say-past.3sg | |||

| ‘Neither Ali danced nor Beste sang.’ | ||||||||

| b. | *Ne | Ali dans | et-me-di, | ne | Beste | şarkı söyle-me-di. | Negative pred. | |

| ne | Ali dance | do-neg-past.3sg | ne | Beste | song say-neg-past.3sg | |||

| Int. ‘Neither Ali danced nor Beste sang.’ | (Jeretič 2017, p. 7) | |||||||

The incompatibility of a negative predicate with overtly clausal coordination, observed in (14b), suggests that when the negative predicate is licensed, the conjuncts are not as big as clauses. This in turn suggests that example (2a), repeated here as (15a), contains no “hidden” structure and is best analyzed as in (15b).5

| 15. | a. | Ne | Hasan | ne | (de) | Mehmet | okul-a | git-me-di. | Negative pred. |

| ne | Hasan | ne | dA | Mehmet | school-dat | go-neg-past.3sg | |||

| ‘Neither Hasan nor Mehmet went to school.’ | |||||||||

| b. | [[Ne | Hasan] | [ne | (de) | Mehmet]] | okul-a | git-me-di. | ||

| [[ne | Hasan] | [ne | dA | Mehmet]] | school-dat | go-neg-past.3sg | |||

On the other hand, given that an NNC with clausal conjuncts must co-occur with an affirmative predicate, it seems plausible to explore the possibility that every NNC with an affirmative predicate is clausal. If this is correct, the underlying representation of example (2b), repeated here as (16a) is the one in (16b), where parts of the first conjunct are deleted.

| 16. | a. | Ne | Hasan | ne | (de) | Mehmet | okul-a | git-ti. | Affirmative pred. |

| ne | Hasan | ne | dA | Mehmet | school-dat | go-past.3sg | |||

| ‘Neither Hasan nor Mehmet went to school.’ | |||||||||

| b. | [[Ne | Hasan | [ne | (de) | Mehmet | okul-a | git-ti]]. | ||

| [[ne | Hasan | [ne | dA | Mehmet | school-dat | go-past.3sg]] |

If this is on the right track, we have an explanation for two of the observed differences between NNCs with affirmative and with negative predicates. First, we can explain the fact that only in an NNC with a negative predicate, but not in an NNC with an affirmative predicate, the entire ne…ne… phrase may be extraposed, as in (17) repeated here from (4) above.

| 17. | a. | *Bu | yılki | toplantı-ya | sen-i | davet | et-miş, | ne | Ali ne | Ayşe. | Affirmative pred. |

| this | year’s | meeting-dat | you-acc | invite | do-evid | ne | Ali ne | Ayşe | |||

| Int. ‘Neither Ali nor Ayşe invited you to this year’s meeting.’ | |||||||||||

| b. | Bu | yılki | toplantı-ya | sen-i | davet | et-me-miş, | ne | Ali ne | Ayşe. | Negative pred. | |

| this | year’s | meeting-dat | you-acc | invite | do-neg-evid | ne | Ali ne | Ayşe | |||

| ‘Neither Ali nor Ayşe invited you to this year’s meeting.’ | |||||||||||

| (Şener and İşsever 2003, p. 1092) | |||||||||||

The contrast in (17) follows from the analysis because the ne…ne… phrase forms a constituent only when the predicate is negative (Jeretič 2017, 2022), as in (15b); such a constituent can undergo movement to a postverbal position just like (almost) any other constituent (provided it is not focused), as in (18).6

When the predicate is affirmative, the string ne Ali ne Ayşe ‘neither Ali nor Ayşe’ does not form a constituent, as shown in (19). Thus, deriving the word order in which this string would appear post-verbally is impossible.7

| 19. | [Bu | yılki | toplantı-ya]i | ne | Ali | sen-i ti | davet | et-miş, | |||||

| this | year’s | meeting-dat | ne | Ali | you-acc | invite | do-evid | ||||||

| ne | Ayşe | sen-i ti | davet | et-miş. | |||||||||

| ne | Ayşe | you-acc | invite | do-evid | |||||||||

| ‘Neither Ali nor Ayşe invited you to this year’s meeting.’ | |||||||||||||

A way to derive the word order of the ungrammatical (17a) from (19) would be to move the subject of the first conjunct (Ali) together with the ne to a postverbal position in its own clause and then to delete the VP in the second conjunct, as shown in (20).

| 20. | *[Bu | yılki | toplantı-ya]i | tk | sen-i | ti | davet | et-miş | [ne | Ali]k, | ||||

| this | year’s | meeting-dat | you-acc | invite | do-evid | ne | Ali | |||||||

| ne | Ayşe | |||||||||||||

| ne | Ayşe | |||||||||||||

| Int. ‘Neither Ali nor Ayşe invited you to this year’s meeting.’ | ||||||||||||||

The deletion of the VP in the second conjunct is presumably not problematic given that (i) the deletion of the VP (in the first conjunct) is the mechanism proposed for examples like (16) and (ii) Turkish more generally allows forward VP ellipsis, as shown in (21).

| 21. | Ali | sen-i | davet | et-ti, | Ayşe | de | |||

| Ali | you-acc | invite | do-past.3sg | Ayşe | dA | ||||

| ‘Ali invited you, and so did Ayşe.’ | |||||||||

However, movement of the ne + subject to the right of the verb (in one or both conjuncts) leads to degradation, as shown in (22b–c). Thus, I conclude that the derivation in (20) is impossible.

| 22. | a. | Ne | Deniz | dans | et-ti | ne | Tunç şarkı | söyle-di. | (Jeretič 2022, ex. 21) | |

| ne | Deniz | dance | do-past.3sg | ne | Tunç song | say-past.3sg | ||||

| ‘Deniz didn’t dance nor did Tunç sing.’ | ||||||||||

| b. | *Dans | et-ti | ne | Deniz | ne | Tunç şarkı | söyle-di. | |||

| dance | do-past.3sg | ne | Deniz | ne | Tunç song | say-past.3sg | ||||

| c. | *Dans | et-ti | ne | Deniz | şarkı | söyle-di | ne | Tunç. | ||

| dance | do-past.3sg | ne | Deniz | song | say-past.3sg | ne | Tunç | |||

The proposal that NNCs with affirmative and negative predicates involve conjuncts of different sizes also derives the fact that only in NNCs with affirmative predicates may the second constituent in a ne…ne… phrase be post-verbal, as in (23) repeated here from (5) above.

| 23. | a. | Ne | Ali dans | et-ti, | ne | (de) | Beste. | Affirmative pred. |

| ne | Ali dance | do-past.3sg | ne | dA | Beste | |||

| ‘Neither Ali nor Beste danced.’ | ||||||||

| b. | *Ne | Ali dans | et-me-di, | ne | (de) | Beste. | Negative pred. | |

| ne | Ali dance | do-neg-past.3sg | ne | dA | Beste | |||

| Int. ‘Neither Ali nor Beste danced.’ | (Jeretič 2017, p. 7) | |||||||

Recast in the present proposal, the contrast in (23) shows that coordination of clauses with the deletion in the second conjunct, shown in (24a), is well-formed, but the coordination of DPs with the extraposition of the second DP together with ne, shown in (24b), is bad.

| 24. | a. | Ne | Ali dans | et-ti, | ne | (de) | Beste | Affirmative pred. | |

| ne | Ali dance | do-past.3sg | ne | dA | Beste | ||||

| ‘Neither Ali nor Beste danced.’ | |||||||||

| b. | *[Ne | Beste]i. | Negative pred. | ||||||

| ne | Ali dance | do-neg-past.3sg | ne | dA | Beste | ||||

| Int. ‘Neither Ali nor Beste danced.’ | (Jeretič 2017, p. 7) | ||||||||

Even though it is not entirely clear to me what excludes (24b) (perhaps it is a violation of the Coordinate Structure Constraint (Ross 1967)), the behavior of comparable correlative conjunctions in Turkish: hem…hem (de)… ‘not only…but also’ and ya…ya (da)… ‘either…or’ offers support for the claim that the derivation in (24b) is disallowed. These coordination structures, mentioned in the Introduction, behave like NNCs in that they also allow the phrase introduced by the second hem ‘and’/ya ‘or’ to appear post-verbally, as shown in (25a–b).8

| 25. | a. | Hem | Ali dans | et-ti, | hem | (de) | Beste. |

| and | Ali dance | do-past.3sg | and | dA | Beste | ||

| ‘Both Ali and Beste danced.’ | |||||||

| b. | Ya | Ali dans | et-ti, | ya | (da) | Beste. | |

| or | Ali dance | do-past.3sg | or | dA | Beste | ||

| ‘Either Ali or Beste danced.’ | |||||||

However, when the verb shows plural agreement, as in (26a–c) and (27a–c), the sentences are only grammatical with a non-extraposed word order, shown in (a) examples. Extraposition of the second conjunct together with hem ‘and’/ya ‘or’ is ill-formed regardless of the φ-features of the extraposed conjunct.9

| 26. | a. | Hem | ben | hem | (de) | Ali dans | et-ti-k. |

| and | I | and | dA | Ali dance | do-past-1pl | ||

| ‘Both I and Ali danced.’ | |||||||

| b. | *Hem | ben | dans | et-ti-k, | hem | (de) Ali. | |

| and | I | dance | do-past-1pl | and | dA Ali | ||

| Int. ‘Both I and Ali danced.’ | |||||||

| c. | *Hem | Ali dans | et-ti | -k, | hem | (de) ben. | |

| and | Ali dance | do-past-1pl | and | dA I | |||

| Int. ‘Both Ali and I danced.’ | |||||||

| 27. | a. | Ya | Ali | ya | (da) | sen dans | et-ti-niz. | |

| or | Ali | or | dA | you dance | do-past-2pl | |||

| ‘Either Ali or you danced.’ | ||||||||

| b. | *Ya | Ali | dans | et-ti-niz, | ya | (da) sen. | ||

| or | Ali | dance | do-past-2pl | or | dA you | |||

| Int. ‘Either Ali or you danced.’ | ||||||||

| c. | *Ya | sen | dans | et-ti-niz, | ya | (da) Ali. | ||

| or | you | dance | do-past-2pl | or | dA Ali | |||

| Int. ‘Either you or Ali danced.’ | ||||||||

The presence of the plural agreement on the verbs in the grammatical (a) examples of (26) and (27) suggests that in these examples, the subject contains small coordination in which each conjunct/disjunct is a DP (Ali, ben ‘I’ in (26); Ali, sen ‘you’ in (27)) and the plural verb agrees with the entire coordination phrase. The ungrammaticality of the extraposed (b) and (c) examples shows that a single conjunct, together with the conjunction particle, cannot be extracted from such a coordinate phrase. If my proposal is on the right track, any NNC that contains a negative verb involves the same small coordination. When the ne…ne… phrase occupies the subject position, the verb agrees with the whole coordination phrase. The extraposed (24b) is then ungrammatical for the same reason for which (26b–c) and (27b–c) are ungrammatical.

How do we account for the grammaticality of the extraposed word order in hem…hem… and ya…ya… constructions with singular verbs, observed in (25a–b)? These examples differ from those in (26) and (27) in that the agreement morphology on the verbs does not force small coordination analysis. Thus, these examples can also receive a clausal-coordination analysis, shown in (28a–b).10

| 28. | a. | Hem | Ali | dans | et-ti, | hem | (de) Beste | |

| and | Ali | dance | do-past.3sg | and | dA Beste | |||

| ‘Both Ali and Beste danced.’ | ||||||||

| b. | Ya | Ali | dans | et-ti, | ya | (da) Beste | ||

| or | Ali | dance | do-past.3sg | or | dA Beste | |||

| ‘Either Ali or Beste danced.’ | ||||||||

Notice that an NNC with a negative verb is not structurally ambiguous: it necessarily contains a small ne…ne… coordination. This is confirmed by the fact that when an NNC is in the subject position and contains a first or a second person pronoun, the agreement on the negative verb is necessarily plural, as in (29a), and the singular agreement (either with the first or the second conjunct), shown in (29b–c), is out.11

| 29. | a. | Ne | Ali | ne (de) | ben | dans | et-me-di-k. |

| ne | Ali | ne dA | I | dance | do-neg-past-1pl | ||

| ‘Neither Ali nor I danced.’ | |||||||

| b. | *Ne | Ali | ne (de) | ben | dans | et-me-di-m. | |

| ne | Ali | ne dA | I | dance | do-neg-past-1sg | ||

| Int. ‘Neither Ali nor I danced.’ | |||||||

| c. | *Ne | Ali | ne (de) | ben | dans | et-me-di. | |

| ne | Ali | ne dA | I | dance | do-neg-past.3sg | ||

| Int. ‘Neither Ali nor I danced.’ | |||||||

Given the fact that an NNC with a negative predicate always involves small coordination, the ungrammaticality of the word order in which the second conjunct appears post-verbally is expected; this word order is derivable from clausal coordination, as shown in (28a–b), but not from DP coordination. As far as I can tell, no coordinated subject in Turkish allows extraposition of the second conjunct (together with the conjunction particle), regardless of the conjunction used.12

Thus, the contrast in (23a–b), repeated here for convenience, follows from the fact that NNCs with affirmative and negative verbs involve conjuncts of different sizes: since clausal coordination is impossible with negative predicates, and only a clausal coordination analysis can yield the grammaticality of (30a), the non-clausal NNC in (30b) is ungrammatical.

| 30. | a. | Ne | Ali | dans | et-ti, | ne (de) Beste. | (Jeretič 2017, p. 7) |

| ne | Ali | dance | do-past.3sg | ne dA Beste | |||

| ‘Neither Ali nor Beste danced.’ | |||||||

| b. | *Ne | Ali | dans | et-me-di, | ne (de) Beste. | ||

| ne | Ali | dance | do-neg-past.3sg | ne dA Beste | |||

| Int. ‘Neither Ali nor Beste danced.’ | |||||||

The difference in the size of the conjuncts in an NNC with affirmative versus negative predicates can thus pretty straightforwardly derive two properties of Turkish NNCs: the first is the fact that the whole ne…ne… phrase can be extraposed only with negative predicates (since only in that case does the ne…ne… phrase form a constituent). The second property that follows from this proposal is the fact that the second conjunct in an NNC, together with the particle ne, cannot be extraposed when the predicate is negative.

However, the difference in the size of the conjuncts in and of itself does not explain why only NNCs with negative predicates can be questioned. This is taken up in the next subsection.13

3.2. Ne in Clausal NNCs Is a Negative Complementizer

In this section, I focus on the observation that the question particle -mI is incompatible with NNCs that contain an affirmative predicate, but compatible with NNCs that contain a negative predicate. The relevant contrast is repeated here from (3).

| 31. | a. | *Ne | Hasan ne | (de) Mehmet | okul-a | git-ti | mi? | Affirmative pred. |

| ne | Hasan ne | dA Mehmet | school-dat | go-past.3sg | q | |||

| Int. ‘Did neither Hasan nor Mehmet go to school?’ | ||||||||

| b. | Ne | Hasan ne | (de) Mehmet | okul-a | git-me-di | mi? | Negative pred. | |

| ne | Hasan ne | dA Mehmet | school-dat | go-neg-past.3sg | q | |||

| ‘Didn’t either Hasan or Mehmet go to school?’ | ||||||||

In order to explain this contrast, I propose that in an NNC ne occupies the complementizer position when it introduces clauses and some lower position when it scopes over smaller constituents.14 Thus, when each ne introduces a clausal conjunct, the structure looks like (32a), but when conjuncts are smaller constituents, the structure is (32b).

| 32. | a. | [CP Ne | [TP Hasan | okul-a | git-ti]] | [CP ne (de) | [TP Mehmet | okul-a | git-ti]]. |

| ne | Hasan | school-dat | go-past.3sg | ne dA | Mehmet | school-dat | go-past.3sg | ||

| ‘Neither Hasan nor Mehmet went to school. | |||||||||

| b. | [TP [[DP Ne | [DP Hasan]] | [DP ne | (de) [DP Mehmet]]] | okul-a | git-me-di]. | |||

| ne | Hasan | ne | dA Mehmet | school-dat | go-neg-past.3sg | ||||

| ‘Neither Hasan nor Mehmet went to school.’ | |||||||||

This difference in what syntactic positions ne occupies in clausal versus non-clausal NNCs dovetails with its negative force: the ne particles that occupy the C position are semantically negative, while the ones that are adjoined to the constituent they introduce are not (instead, they need licensing by sentential negation on the predicate). Here, I propose that the former ne particles are negative complementizers, while the latter are Negative Concord Items (NCIs) which, like other NCIs in the language, need negation to be licensed (Laka 1990; Giannakidou 2006, among others).15 I will further argue that clausal NNCs, which involve negative complementizers, are conjunctions, while phrasal NNCs, which involve NCI particles, are disjunctions.

The contrast in (31) follows from the proposal that ne particles found in clausal NNCs are complementizers: an NNC cannot be questioned when it contains an affirmative predicate because in such an NNC the conjuncts are underlyingly full CPs, each headed by ne. Since mI, when it scopes over an entire event, also occupies the C position, ne and mI cannot co-occur.16 This is illustrated in (33).

| 33. | *[CP Ne | Hasan | [CP ne | (de) Mehmet | okul-a | git-ti mi]? | |

| ne | Hasan | ne | dA Mehmet | school-dat | go-past.3sg q | ||

| Int. ‘Did neither Hasan nor Mehmet go to school?’ | |||||||

The incompatibility of ne and mI persists in non-eliptical contexts as well, as shown in (34):

| 34. | *Ne | Hasan | okul-a | git-ti | mi | ne (de) | Mehmet | okul-dan | gel-di | mi? | ||

| ne | Hasan | school-dat | go-past.3sg | q | ne dA | Mehmet | school-abl | come-past.3sg | q | |||

| Int. ‘Did neither Hasan go to school nor Mehmet come from school?’ | ||||||||||||

An analysis on which a single –mI takes the entire ne…ne… phrase as its complement, as in (35), is also ruled out because the question particle mI, when it occupies C and scopes over the entire event, takes as its complement a TP, not a CP.17

| 35. | *[CP [CP Ne | Hasan | [CP ne | (de) | Mehmet | okul-a | git-ti] mi]? | |

| ne | Hasan | ne | dA | Mehmet | school-dat | go-past.3sg q | ||

| Int. ‘Did neither Hasan nor Mehmet go to school?’ | ||||||||

When an NNC contains a negative predicate, given that the coordinated constituents are not full CPs, the two ne’s do not occupy complementizer positions, and mI is allowed:

| 36. | [CP [TP [Ne | [DP Hasan]] | [ne | (de) | [DP Mehmet]] | okul-a | git-me-di] mi]? |

| ne | Hasan | ne | dA | Mehmet | school-dat | go-neg-past.3sg q | |

| ‘Did neither Hasan nor Mehmet go to school?’ | |||||||

The proposal that ne particles in clausal NNCs are negative complementizers straightforwardly accounts for the semantics of clausal NNCs: the negative force is encoded in the complementizers ne, just like it is encoded in the negative complementizer nach in the Irish example (37) below.

| 37. | Creidim | nach | gcuirfidh | sí | isteach | ar an phost. | Irish |

| I-believe | neg.comp | put [fut] | she | in | on the job | ||

| ‘I believe that she won’t apply for the job.’ | (McCloskey 2001, p. 75) | ||||||

One prediction that this analysis makes is that clausal NNCs (NNCs with affirmative predicates) should be able to host Negative Polarity Items (NPIs). In the absence of sentential negation, the negative complementizers (ne...ne…) should be able to license NPIs, just like nach does in (38) below.

| 38. | Cheapas | go deo nach | rachadh | aoinne | ann. | Irish |

| I-thought | ever neg.comp | would-go | anyone | there | ||

| ‘I thought that nobody would ever go there.’ | (McCloskey 1996, p. 94) | |||||

Interestingly, this prediction is not borne out: ne does not license NPIs in the TP that it takes as the complement. As noted by Şener and İşsever (2003), an NNC that contains an NPI is ungrammatical unless the verb is negative, as shown by the contrast in (39a–b).

| 39. | a. | *Bu | yılki | toplantı-ya | ne Ali ne | Ayşe kimse-yi | davet et-miş. | Affirmative pred. |

| this | year’s | meeting-dat | ne Ali ne | Ayşe anybody-acc | invite do-evid | |||

| Int. ‘Neither Ali nor Ayşe invited anybody to this year’s meeting.’ | ||||||||

| b. | Bu | yılki | toplantı-ya | ne Ali ne | Ayşe kimse-yi | davet et-me-miş. | Negative pred. | |

| this | year’s | meeting-dat | ne Ali ne | Ayşe anybody-acc | invite do-neg-evid | |||

| ‘Neither Ali nor Ayşe invited anybody to this year’s meeting.’ | ||||||||

| (Şener and İşsever 2003, p. 1091) | ||||||||

On the present proposal, the structure of (39a) is the one in (40), where the NPI kimse ‘anybody’ is c-commanded by ne in each conjunct, but the sentence is nevertheless ungrammatical in the absence of the sentential negation. This indicates that ne, despite its negative semantics, does not license NPIs.

| 40. | *[Bu | yılki | toplantı-ya]i | [CP ne | [TP Ali | |||

| this | year’s | meeting-dat | ne | Ali | ||||

| [CP ne | [TP Ayşe | kimse-yi ti | davet et-miş]] | |||||

| ne | Ayşe | anybody-acc | invite do-evid | |||||

| Int. ‘Neither Ali nor Ayşe invited anybody to this year’s meeting.’ | ||||||||

Even when the NNC involves no ellipsis, and each clause contains an NPI that is overtly within the scope of ne, the sentence is ungrammatical without the sentential negation on the predicate.

| 41. | *Bu | toplantı-ya | rektöri | [CP ne hiçbir | professor-ü | ti | davet et-ti] |

| this | meeting-dat | president | ne any | professor-acc | invite do-past.3sg | ||

| [CP ne hiçbir | doçent-i | ti | davet et-ti]. | ||||

| ne any | assoc.prof.-acc | invite do-past.3sg | |||||

| Int. ‘The president invited neither any professors nor any assoc. professors to this meeting.’ | |||||||

In order to account for the ungrammaticality of NNCs in (39a) and (41), I will assume, following Şener (2007), İnce (2012), Kamali (2017), Jeretič (2017, 2022), and Görgülü (2020), that Turkish negation-sensitive elements ((hiç)kimse ‘anybody/nobody’, hiç ‘at all’, sakın ‘under no circumstances’,…) are Negative Concord Items (NCIs) rather than Negative Polarity Items (NPIs) and I will propose that Negative Concord (NC) in Turkish is impossible across a finite TP boundary.18

As supporting evidence for the claim that Turkish has NCIs rather than NPIs, it has been put forth that these elements can appear in fragment answers and preverbal positions, as shown in (42a–b).19

| 42. | a. | Q: | Ali | kim-le konuş-uyor? | (İnce 2012, p. 189) |

| Ali | who-com speak-prog.3sg | ||||

| ‘Who is Ali talking to?’ | |||||

| A: | (Hiç)kimse-yle! | ||||

| anybody-com | |||||

| ‘To nobody!’ | |||||

| b. | Kimse | gel-me-di. | (İnce 2012, p. 190) | ||

| anybody.nom | come-neg-past.3sg | ||||

| ‘Nobody came.’ (Lit. ‘Anybody didn’t come.’) | |||||

As shown by Kornfilt (1997), Kelepir (2001), and Kayabaşı and Özgen (2018), among others,20 NCIs in Turkish are not licensed by superordinate negation in finite embedded clauses. This is shown in (43a–b).

| 43. | *Kimse-∅ | geç gel-di | san-mı-yor-lar. | (Kelepir 2001, p. 151) |

| anybody-nom | late come-past.3sg | think-neg-prog-3pl | ||

| Int. ‘They don’t think anybody came late.’ | ||||

However, in embedded non-finite clauses,21 NCIs seem to be licensed long distance, as shown by (44) and (45) (Kornfilt 1984, 2007; Zidani-Eroğlu 1997; Kelepir 2001; Predolac 2017).22

| 44. | Ahmet-in | kimse-yi | sev-diğ-in-i | san-mı-yor-um. | |

| Ahmet-gen | anybody-acc | love-dık-3.sg-acc | think-neg-prog-1sg | ||

| ‘I don’t think Ahmet loves anybody.’ | (Kelepir 2001, p. 148) | ||||

| 45. | Hasan-ın | kimse-yi | ara-ma-sın-ı | iste-mi-yor-um. | |

| Hasan-gen | anybody-acc | call-ma-3.sg-acc | want-neg- prog-1sg | ||

| ‘I don’t want Hasan to call anybody.’ | (Kelepir 2001, p. 149) | ||||

This distribution of NCIs suggests that NC in Turkish is clause-bound (Linebarger 1980; Zanuttini 1991; Progovac 1994; Haegeman 1995; Şener 2007). In (46) below, repeated from (39a)/(40), the TP complements of ne are finite and the embedded NCI object is not licensed. These facts can be explained if NC in Turkish is not only a local phenomenon, but is in fact restricted to the domain of a finite TP (rather than a finite CP). In embedded finite clauses, shown in (43), the finite TP boundary intervenes between the NCI and the matrix negation, while in clausal NNCs, shown in (39a)/(46) and (41), the finite TP boundary intervenes between the NCI and the negative complementizer. Consequently, NC is precluded in both cases.

| 46. | *[Bu yılki | toplantı-ya]i | [CP ne | [TP Ali | ||

| this year’s | meeting-dat | ne | [TP Ali | |||

| [CP ne | [TP Ayşe | kimse-yi ti | davet et-miş]] | |||

| ne | [TP Ayşe | anybody-acc | invite do-evid] |

If ne is a negative complementizer and if the generalization above is correct, then we should expect that an NCI inside a non-finite complement of a negative complementizer ne will be licensed (since NC obtains in embedded nominalized clauses in (44) and (45)). Surprisingly, NCIs are not licensed in embedded NNCs in (47a) and (48a) below, even though the complement of each ne is a non-finite nominalized clause, as represented in the (b) examples.

| 47. | a. | *Ahmet-in | ne hiçbir | film-i | ne (de) | hiçbir dizi-yi | sev-diğ-in-i | düşün-üyor-um. |

| Ahmet-gen | ne any | movie-acc | ne dA | any series-acc | like-dik-3sg-acc | think -prog-1sg | ||

| Int. ‘I think that Ahmet likes/liked neither any movies nor any series.’ | ||||||||

| b. | *Ahmet-ini | [CP ne [TP ti | hiçbir film-i | |||

| Ahmet-gen | ne | any movie-acc | ||||

| [CP ne (de) | [TP ti hiçbir dizi-yi | sev-diğ-in-i]] | düşün-üyor-um. | |||

| ne dA | any series-acc | like-dik-3sg-acc | think -prog-1sg | |||

| Int. ‘I think that Ahmet likes/liked neither any movies nor any series.’ | ||||||

| 48. | a. | *Hasan-ın | ne | hiçbir dosya-yı | ne (de) | hiçbir aday-ı | değerlendir-me-sin-i |

| Hasan-gen | ne | any file-acc | ne dA | any candidate-acc | evaluate-ma-3sg-acc | ||

| ist-iyor-um. | |||||||

| want-prog-1sg | |||||||

| Int. ‘I want Hasan to evaluate neither any files nor any candidates.’ | |||||||

| b. | *Hasan-ıni | [CP ne | [TP ti hiçbir dosya-yı | ||||

| Hasan-gen | ne | any file-acc | |||||

| [CP ne (de) | [TP ti hiçbir aday-ı | değerlendir-me-sin-i]] | ist-iyor-um. | ||||

| ne dA | any candidate-acc | evaluate-mA-3sg-acc | want-prog-1sg | ||||

| Int. ‘I want Hasan to evaluate neither any files nor any candidates.’ | |||||||

One way to explain the contrast between the grammatical (44) and (45) on the one hand and the ungrammatical NNCs in (47a) and (48a) on the other is to adopt Predolac’s (2017) analysis of Turkish embedded nominalized clauses (–DIK/–(y)AcAK and –mA clauses). Predolac proposes that these clauses are CPs (without a DP layer on top). However, she proposes that the C which heads –DIK/–(y)AcAK and –mA clauses is nominal in nature, i.e., that it has a strong [−v]/[+n] feature, which is responsible for the genitive case on the embedded clause subject as well as for the nominal agreement of the verb.23 How would this analysis help explain the absence of NC in (47a) and (48a)? Suppose that the negative complementizer ne is incompatible with a nominal C (just like, for example, if is incompatible with a declarative C in English) and can only occupy the C position when the C is featurally [+v]/[−n], i.e., in finite clauses. If this is the case, then the ne particles in (47a) and (48a) do not occupy embedded C positions because the embedded clauses in these examples are headed by [−v]/[+n] C’s. This means that the analyses given in (47b) and (48b), where the ne particles occupy the C positions, are incorrect. Instead, the nominalized CPs are treated as nominal arguments (DPs) of the verb and the ne particles are adjoined to them (like in phrasal NNCs), as shown in (49a–b).24 The reason why the examples are ungrammatical is because these ne particles are not negative complementizers and do not carry negative force themselves, so they cannot license NCIs. Instead, the ne particles are themselves NCIs, which need negation to be licensed. So, (47a) and (48a), whose correct representations are given in (49a–b) respectively, are bad because they contain instances of unlicensed NCIs both in the embedded CPs (e.g., hiçbir film ‘any movie’, hiçbir dizi ‘any series’) and adjoined to the embedded CPs (the two ne’s).

| 49. | a. | *Ahmet-ini | [CP ne | [CP ti hiçbir film-i | |

| Ahmet-gen | ne | any movie-acc | |||

| [CP ne (de) | [CP ti hiçbir dizi-yi | sev-diğ-in-i]] | düşün-üyor-um. | ||

| ne dA | any series-acc | like-dik-3sg-acc | think -prog-1sg | ||

| b. | *Hasan-ıni | [CP ne | [CP ti hiçbir dosya-yı | ||

| Hasan-gen | ne | any file-acc | |||

| [CP ne (de) | [CP ti hiçbir aday-ı | değerlendir-me-sin-i]] | ist-iyor-um. | ||

| ne dA | any candidate-acc | evaluate-mA-3sg-acc | want-prog-1sg |

Notice that embedded NNCs (without NCIs) are possible, as shown by (50). This example has different structures depending on whether the embedded verb is affirmative (okuduğuna ‘read’) or negative (okumadığına ‘didn’t read’). Both possibilities are discussed below.

| 50. | Osman ne | Ali-nin ne | Ayşe-nin kitap | Şener and İşsever (2003, p. 1097) | |

| Osman ne | Ali-gen ne | Ayşe-gen book | |||

| oku-duğ-un-a | /oku-ma-dığ-ın-a | inan-ma-dı. | |||

| read-dık-3sg-dat | /read-neg-dık-3sg-dat | believe-neg-past.3sg | |||

| ‘Osman didn’t believe that either Ali or Ayşe read/didn’t read a book/books.’ | |||||

If the embedded verb is affirmative (okuduğuna ‘read’), the NNC is clausal, but the ne particles are adjoined to each nominalized CP, like in (49a–b). This time the sentence is grammatical because there are no NCIs in the embedded clauses (so, the fact that the CP-adjoined ne particles are not negative is not a problem) and the matrix verb is negative (so, the ne particles themselves are licensed by the matrix negation). This licensing is possible since there is no finite TP boundary between the negative matrix verb and the CP-adjoined ne particles. This is shown in (51).

| 51. | Osman | [CP ne | [CP Ali-nin | [CP ne | [CP Ayşe-nin | kitap oku-duğ-un-a ]] | |

| Osman | ne | Ali-gen | ne | Ayşe-gen | book read-dik-3sg-dat | ||

| inan-ma-dı. | |||||||

| believe-neg-past.3sg | |||||||

| ‘Osman didn’t believe that either Ali or Ayşe read a book/books.’ | |||||||

If, on the other hand, the embedded verb is negative (okumadığına ‘didn’t read’), the NNC is phrasal, with each ne adjoined to the DP it introduces. Except the ne particles, there are no other NCIs to be licensed in the sentence, and the ne particles themselves are licensed by the negation marker on the embedded verb. This is shown in (52).

| 52. | Osman | [CP [DP ne | [DP Ali-nin]] | [DP ne | [DP Ayşe-nin]] | kitap |

| Osman | ne | Ali-gen | ne | Ayşe-gen | book | |

| oku-ma-dığ-ın-a ] | inan-ma-dı. | |||||

| read-neg-dık-3sg-dat | believe-neg-past.3sg | |||||

| ‘Osman didn’t believe that neither Ali nor Ayşe didn’t read a book/books.’ | ||||||

My informants report that (50) is grammatical even when both the matrix verb and the embedded verb are affirmative, as in (53a). Here, the absence of the negation marker on either verb suggests that the NNC is clausal, but at the same time excludes the possibility that the ne particles are NCIs, adjoined to the embedded nominalized CPs (because these particles require the presence of the negation marker). Thus, the ne particles must be negative complementizers. However, the fact that the embedded C’s are featurally nominal excludes the possibility that the NNC is at the embedded level since a negative complementizer is incompatible with the featural combination of such C’s ([−v]/[+n]). This leaves us with the analysis in (53b), on which the clausal coordination is at the matrix level, with each ne occupying a matrix C position.

| 53. | a. | Osman ne | Ali-nin ne | Ayşe-nin kitap | oku-duğ-un-a | inan-dı. | |

| Osman ne | Ali-gen ne | Ayşe-gen book | read-dık-3sg-dat | believe-past.3sg | |||

| ‘Osman believed that neither Ali nor Ayşe read a book/books.’ | |||||||

| b. | Osmani [CP ne | [TP ti [CP Ali-nin | |||||

| Osman ne | Ali-gen | ||||||

| [CP ne | [TP ti [CP Ayşe-nin kitap | oku-duğ-un-a] | inan-dı]] | ||||

| ne | Ayşe-gen book | read-dık-3sg-dat | believe-past.3sg | ||||

Thus, nominalized C’s can grammatically co-occur with ne particles (with ne particles either occupying CP-adjoined positions or introducing matrix clauses); they just cannot syntactically host such particles.

This is different from the situation we encountered above, where I proposed that the impossibility of questioning NNCs with an affirmative predicate stems from the fact that both the negative particle ne and the question particle mI compete for the same position (the C position) and therefore cannot co-occur. This is presumably because both ne and mI occupy the position of a [+v]/[−n] C.

Similar evidence that the ne particles in clausal NNCs are indeed (negative) complementizers comes from the fact that clausal NNCs are also incompatible with conditionals (Lewis 1967). If the verb in an NNC is suffixed by a conditional marker, it cannot be affirmative, as (54a–b) show. Markers of conditionals (like Turkish –sA) are commonly assumed to be CP-related elements (Bhatt and Pancheva 2006), and so the fact that a NNC with an affirmative verb cannot contain the conditional suffix –sA is not surprising if both ne and –sA occupy the C position.

| 54. | a. | *Ahmet ne | bira ne (de) | şarap | iç-er-se | on-a kola ver. |

| Ahmet ne | beer ne dA | wine | drink-pres-cond | him-dat Coke give.imp | ||

| Int. ‘If Ahmet doesn’t drink beer or wine, give him Coke.’ | ||||||

| b. | Ahmet ne | bira ne (de) | şarap | iç-mez-se | on-a kola ver. | |

| Ahmet ne | beer ne dA | wine | drink-neg.pres-cond | him-dat Coke give.imp | ||

| ‘If Ahmet doesn’t drink beer or wine, give him Coke.’ | ||||||

I next turn to the nature of the ne…ne… coordination.

3.3. Clausal NNCs as a Conjunction of Negatives

So far, I have shown evidence suggesting that NNCs with affirmative predicates are clausal coordinations, with each coordinand being introduced by a negative complementizer ne (except when the clauses are nominalized CPs, whose C’s are incompatible with ne’s). One the other hand, NNCs with negative predicates are argued to involve a smaller, non-clausal coordination, where the ne particles that introduce each coordinand do not carry negative force, but are instead NCIs whose licensing requires c-command by the negative marker. Thus, the two kinds of NNCs involve the structures shown schematically in (55a–b), where “coord.” stands for “coordinator”.

| 55. | a. | Clausal NNCs: | ¬ A coord ¬ B |

| b. | Non-clausal NNCs: | ¬ (A coord B) |

Given the structural configuration for clausal NNCs (in which each coordinand is negated), the semantic computation for such NNCs yields the correct meaning only if the coordinator in (55a) is a conjunction, so that the NNC (ne A… ne B…) is interpreted as ¬ A ∧ ¬ B. The clausal NNC in (2a), repeated here as (56) (with an affirmative predicate) has exactly that reading.25

| 56. | Ne Hasan | ne (de) | Mehmet | okul-a | git-ti. | Affirmative pred. |

| ne Hasan | ne dA | Mehmet | school-dat | go-past.3sg | ||

| ‘It is not the case that Hasan went to school and it is not the case that Mehmet went to school.’ | ||||||

The structure of a clausal NNC is given in (57).

| 57. | Clausal NNC: affirmative predicate |

|

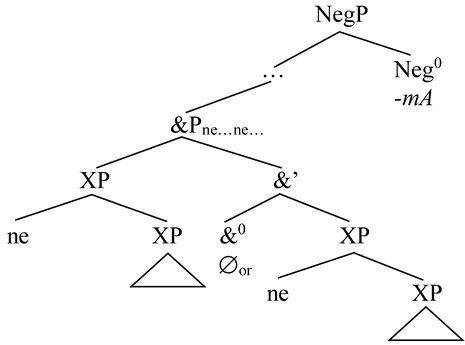

However, a similar structure cannot be posited for non-clausal NNCs (with negative predicates), where the ne particles are non-negative: the negative semantics in such NNCs stems from the negation marker –mA on the predicate. If non-clausal NNCs also involved a conjunction, the structure would be as in (58), yielding the meaning ¬ (A ∧ B) for a NNC ne A…ne B….

| 58. | Non-clausal NNC: negative predicate (to be revised) |

|

This is, however, not the meaning that non-clausal NNCs have, as shown by in (59) below, repeated from (2b): the NNC has only the reading in (59a), and the reading in (59b) is absent.

| 59. | Ne Hasan | ne (de) | Mehmet | okul-a | git-me-di. | Negative pred. |

| ne Hasan | ne dA | Mehmet | school-dat | go-neg-past.3sg | ||

| a. ‘Neither Hasan nor Mehmet went to school.’ | ||||||

| b. #‘It is not the case that both Hasan and Mehmet went to school.’ | ||||||

Thus, the structure posited for the non-clausal NNCs should be such that it derives the same meaning that clausal NNCs have (since we saw at the beginning of the paper that the presence versus the absence of the negative marker on the predicate of an NNC does not affect the truth conditions of the sentence). All of these considerations taken together suggest that non-clausal NNCs are disjunctions, embedded under sentential negation, as in (60).26

| 60. | Non-clausal NNC: negative predicate (final) |

|

4. Loose and Not-So-Loose Ends

In this section, I discuss examples that do not follow from my analysis and then present some others that do. I argued that a clausal NNC (with an affirmative verb) cannot be questioned because the question particle –mI and the negative complementizer ne both occupy the C position and thus cannot co-occur. For the same reason, the complementizer ne cannot co-ocur with the conditional marker –sA. However, an NNC can be embedded under the complementizer diye ‘saying’, as shown in (61). In (61), the embedded clause is a reason clause, which, according to Gündoğdu (2017), means that diye sits in the C position and takes the embedded clause as the complement (see also Note 17). Given that the embedded clause is introduced by ne, which I argued also occupies the C position, (61) should be ungrammatical for the same reason for which (62a–b) are ungrammatical. However, the sentence is well-formed.

| 61. | Ne | Ali ne (de) | Ahmet | gel-di | diye, | Mehmet de | erken ayrıl-dı. |

| ne | Ali ne dA | Ahmet | come-past.3sg | diye | Mehmet dA | early leave-past.3sg | |

| ‘Since neither Ali nor Ahmet came, Mehmet also left early.’ | |||||||

| 62. | a. | *Ne | Ali ne (de) | Ahmet | gel-di mi? | |

| ne | Ali ne dA | Ahmet | come-past.3sg q | |||

| Int. ‘Did either Ali or Ahmet come?’ | ||||||

| b. | *Ne | Ali ne (de) | Ahmet | gel-ir-se | onlar-ı ara. | |

| ne | Ali ne dA | Ahmet | come-pres-cond | them-acc call.imp | ||

| Int. ‘If neither Ali nor Ahmet comes, call them.’ | ||||||

That there is some deeper incompatibility between ne and –mI is shown also by the fact that –mI, which normally can occupy a variety of positions besides C, cannot do so in an NNC, regardless of whether the verb in the NNC is affirmative or negative, as shown by (63a–b).

| 63. | a. | *Ali ne | Elif-i mi | ne (de) | Sahra-yı mı | gör-dü? |

| Ali ne | Elif-acc q | ne dA | Sahra-acc Q | see-past.3sg | ||

| Int. ‘Were the persons who Ali didn’t see (really) Elif nor Sahra?’ | ||||||

| b. | *Ali ne | Elif-i (mi) | ne (de) | Sahra-yı mı | gör-me-di? | |

| Ali ne | Elif-acc q | ne dA | Sahra-acc q | see-neg-past.3sg | ||

| Int. ‘Were the persons who Ali didn’t see (really) Elif nor Sahra?’ | ||||||

This is unexpected; if the examples in (63a–b) underlyingly have the structures in (64a–b) respectively, there should be no reason why these sentences could not accommodate question particles.

| 64. | a. | *Alii [CP ne | [TP ti Elif-i mi gör-dü]] | [CP ne (de) | [TP ti Sahra-yı mı | gör-dü]]? |

| Ali ne | Elif-acc q see-past | ne dA | Sahra-acc q | see-past.3sg | ||

| b. | *Ali [ne | Elif-i (mi)] | [ne (de) | Sahra-yı mı] | gör-me-di? | |

| Ali ne | Elif-acc q | ne dA | Sahra-acc q | see-neg-past.3sg |

The (a) examples in (63)–(64) might be explained if we assume that Turkish –mI originates on the phrase that it overtly marks, but then covertly moves to C (Aygen 2007; Bayırlı 2017) and for this reason, C must be empty at LF and not occupied by ne. However, in the (b) examples, since ne does not occupy C, –mI should be free to move there without incurring ungrammaticality, but it is not. I have no explanation for these facts. However, the generalization seems to be that somehow, the negative complementizer ne can surface when C is occupied by “plain” subordinating complementizers like diye ‘saying’, but not when C is occupied by elements whose semantic import is richer than that, like mI or –sA. I leave these issues for further work.

Finally, that an NNC with an affirmative verb involves bigger conjuncts than an NNC with a negative verb is suggested by the fact that in embedded environments (even in the presence of diye) the former gives rise to ambiguity, while the latter does not. Thus, (65) is ambiguous between the readings given in (65a–b). On the present analysis, the ambiguity is explained if the reading in (65a) is derived when the conjuncts are matrix ne-clauses, as in (66a), and the reading in (65b) is derived when they are limited to the embedded ne-clauses, as in (66b).

| 65. | Ne | Ali ne (de) | Ayşe gel-di | diye | duy-du-m. |

| ne | Ali ne dA | Ayşe come-past.3sg | diye | hear-past-1sg | |

| a. ‘I didn’t hear that Ali came and I didn’t hear that Ayşe came.’ | |||||

| b. ‘I heard that Ali didn’t come and that Ayşe didn’t come.’ = ‘I heard that neither Ali nor Ayşe came.’ | |||||

| 66. | a. | [Ne | [Ali | ∧ [ne (de) | [Ayşe gel-di | diye] duy-du-m.]] | |

| ne | Ali | ∧ ne dA | Ayşe come-past | diye hear-past-1sg | |||

| b. | [[Ne | Ali | ∧ [ne (de) Ayşe | gel-di | diye] duy-du-m.] | ||

| ne | Ali | ∧ ne dA Ayşe | come-past.3sg | diye hear-past-1sg |

By contrast, when the verb of an NNC is negative, as in (67), only the reading in (65b)/(67b) is attested. This is predicted, given that the ne…ne… coordination cannot be extended to the matrix clause. The structure of (67) is unambiguously the one in (68).

| 67. | Ne | Ali ne (de) | Ayşe | gel-me-di | diye | duy-du-m. |

| ne | Ali ne dA | Ayşe | come-neg-past.3sg | diye | hear-past-1sg | |

| a. *‘I didn’t hear that Ali came and I didn’t hear that Ayşe came.’ | ||||||

| b. ‘I heard that neither Ali nor Ayşe came.’ | ||||||

| 68. | [[[[Ne | Ali] | ∨ [ne (de) | Ayşe]] | gel-me-di | diye] duy-du-m]. |

| ne | Ali | ∨ ne dA | Ayşe | come-neg-past.3sg | diye hear-past-1sg |

5. Conclusions

In this paper I proposed an analysis of the ne…ne construction in Turkish. This construction can contain an affirmative or a negative verb without a change in meaning, but the syntactic behavior of the two kinds of NNCs differs in terms of word order possibilities and the compatibility with the question particle –mI. I proposed that a clausal NNC has the structure of CP coordination headed by a null conjunction in which each conjunct is semantically negative (because it is headed by a negative complementizer). On the other hand, an NNC with a negative verb involves a disjunction of smaller constituents (Jeretič 2017, 2022), in which each disjunct is introduced by a non-negative NCI ne, licensed by the negative marker that appears on the verb. The analysis results in the two kinds of ne particles being classified as different lexical items, one participating in NC, one not. This is similar (although not identical) to Herburger’s (2001) analysis of Spanish n-words, where the author argues that n-words are lexically ambiguous between NPIs and their genuinely negative counterparts.

The differences in the syntactic make-up of the conjuncts results in the differences of constituent structure, which in turn derives differences in word order possibilities depending on the polarity of the predicate. The fact that an NNC with an affirmative verb is incompatible with the question particle follows from the proposal that the question particle and the particle ne in clausal coordination compete for the same (C) position and thus cannot co-occur.

The analysis presented here draws heavily on Jeretič (2017, 2022): both propose the existence of clausal and non-clausal NNCs and in both the ne particles found in non-clausal NNCs are treated as NCIs. However, on Jeretič’s analysis, Turkish ne particles are unambiguously NCIs but NC is obligatory only in non-clausal NNCs. Thus, Jeretič argues that Turkish NC is of the “hybrid” type, i.e., that Turkish has “NCIs that do not behave uniformly in how they engage in NC” (Jeretič 2022, p. 1152). If the analysis I propose here is correct, in particular, if ne particles found in non-clausal NNCs are NCIs, but those found in clausal NNCs are not, then it can be maintained that Turkish is a strict Negative Concord language (Zeijlstra 2004; Kamali 2017, among others), in which (abstracting away from polar questions) all NCIs have to be associated with a licensor (in our case, sentential negation).

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| 1 | first person |

| 2 | second person |

| 3 | third person |

| ABL | ablative |

| aff | affirmative |

| ACC | accusative |

| COM | comitative |

| COND | conditional |

| DAT | dative |

| DIK | nominalizer –DIK |

| EVID | evidential |

| F | focus |

| FUT | future |

| GEN | genitive |

| IMP | imperative |

| Int. | intended |

| mA | nominalizer –ma |

| neg | negative |

| NEG | negation |

| NEG.COMP | negative complementizer |

| NOM | nominative |

| PAST | past |

| PERF | perfect |

| PL | plural |

| PROG | progressive |

| Q | question particle |

| SG | singular |

Notes

| 1 | I would like to sincerely thank Yağmur Kiper, Alper Kesici, Sercan Karakaş, and the students of my Introduction to Syntax class in the Fall of 2021 for their invaluable help with judgments of this extremely difficult construction. Special thanks go to İsa Bayırlı both for his help as a language consultant and for helpful discussions on the topic, as well as to the guest editor and two anonymous Languages reviewers, whose comments significantly improved earlier versions of the paper. All remaining errors are my own. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | The dA…dA construction differs from these in that the enumerating particle dA follows the conjoined phrases and is attached to each item that is enumerated (Göksel and Kerslake 2005), as shown in (i).

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | My analysis heavily relies on this insight by Jeretič, although I do not adopt the rest of her proposal. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | As a reviewer points out, the question is more general in that it applies also to other (non-negative) correlative conjunctions in the language (those seen in (1)). In this paper, I must leave the reduplication of the ne particles in an NNC unsolved. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5 | A note on the absence of the plural agreement morphology on the verb in (15) is in order: In Turkish sentences with plural or coordinated 3rd person subjects, the verb typically shows singular agreement. Plural marking on the verb is possible (although dispreferred) with human subjects, as in (ia), and is worse/impossible with inanimate subjects, as in (ib).

Thus, for the verb in (15) to show singular agreement although its subject is a coordination phrase is expected and independent of the NNC. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6 | Şener and İşsever (2003) do not discuss the size of the constituents in an NNC; they derive the contrast in (17) from their proposal that an NNC contains a negative predicate when the ne…ne… phrase is not focused, and an affirmative predicate when the ne…ne… phrase is focused. Since the postverbal position in Turkish is associated with an obligatory lack of focus, it follows from Şener and İşsever’s analysis that the ne...ne... phrase can only be postverbal when the predicate is negative. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7 | I assume that in an NNC, each ne introduces its own conjunct, so when the coordination is clausal, each ne introduces its own clause. In such cases, when a constituent that is interpreted in both conjuncts (like bu yılkı toplantıya ‘to this year’s meeting’ in (19)) precedes both ne’s in the NNC, I assume that the constituent has been moved Across-the-board to the sentence-initial positon. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8 | With these conjunctions, the second conjunct together with the second hem ‘and’/ya ‘or’ can appear post-verbally independently of the polarity of the predicate: it is possible with both affirmative and negative predicates. Thus, (25a–b) can both contain a negative predicate as shown in (ia–b). However, the presence versus the absence of the negation in these constructions affects the semantics of the sentence in the way the sentential negation is expected to.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 9 | As mentioned in Note 5, Turkish tolerates (and even favors) singular agreement with plural and coordinated subjects that are 3rd person. The same is true of the hem…hem… and ya…ya… constructions: when both conjuncts are third person singular, the verb preferably shows singular agreement, as shown in (ia–b).

However, when one of the conjuncts is first or second person, as in (iia–b) and (iiia–b), for many speakers the verb obligatorily requires plural agreement. This is why (26a–b) and (27a–b) contain a first or second person personal pronoun as one of the conjuncts. Jaklin Kornfilt (personal communication) informs me that in such examples, but probably not in the ne…ne… example in (29b) below, closer conjunct agreement is also a possibility; see (Tat and Kornfilt 2022) for relevant discussion. A correct description of all the agreement patterns in Turkish correlative conjunctions would require a larger survey, which I have to leave for the future.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10 | The clausal conjunction analysis is also available to examples with extraposed word orders, like (ia), where one of the conjuncts is a first or second person pronoun, but the first, non-elliptical conjunct involves no agreement violation. This is expected given that ellipsis more generally allows morphological mismatches.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 11 | I am grateful to a reviewer for urging me to be more explicit about the correlation between the presence of the negation marker on the verb and the plural agreement. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12 | Some conjunctions, like ve ‘and’ and veya ‘or’, seem to disallow reduction in the second conjunct, as shown by the ungrammaticality of (ia–b).

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 13 | Interestingly, subject NNCs with affirmative verbs, in which one of the phrases introduced by ne is the first or the second person pronoun (ben ‘I’, sen ‘you’), can also show plural agreement, as in (i). This is unexpected given the claim that such NNCs always involve clausal coordination.

However, such NNCs also display behavior similar to NNCs with negative predicates, in that they can be questioned and do not allow extraposition of the second conjunct.

Even though such NNCs show properties characteristic of small ne…ne… coordination, they disallow extraposition of the entire ne…ne… phrase, as shown in (iii). For now, I have no explanation for any of these facts.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 14 | The syntactic positioning of ne seems to mirror (to an extent) the distribution of the question particle mI in the language, which occupies the C position when it scopes over the entire event (Kornfilt 1997; Besler 2000; Aygen 2007; Kamali 2011; Gračanin-Yuksek and Kırkıcı 2016, among others), and is adjoined to the phrase it questions when it takes narrow scope (Besler 2000; Kamali 2011).

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 15 | Thus, the analysis presented here is reminiscent of Herburger’s (2001) analysis of n-words in Spanish (Romance). Herburger analyzes Spanish n-words as being lexically ambiguous between NPIs and so-called “negative elements”, the latter comprising “negative quantifiers, negative determiners, sentential and constituent negation, the negative conjunction neither…nor, and adjectival neither” (Herburger 2001, p. 291). Like Herburger, I propose that ne is lexically ambiguous. However, the ambiguity is between a negative complementizer (whose existence and usage is, presumably independent of Negative Concord) and an NCI, which does not carry negative force on its own, but instead requires licensing by local negation. I would like to thank an anonymous reviewer for bringing Herburger’s study to my attention and for helping me relate my own proposal to her work. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 16 | A reviewer notes that the competition of ne and mI for the same syntactic position might not be on the right track since ne is linearized to the left and mI to the right. The reviewer suggests that NNCs might be incompatible with mI due to a conflict between the syntax of full clausal coordination and the prosody of yes-no questions. If this is the case, as noted by the reviewer, the same incompatibility should arise with cases of hem…hem… ‘not only...but also’ and ya…ya… ‘either...or’ coordination. I am grateful to the reviewer for the comment and I believe that this option is worth exploring. However, as indicated below, the informal judgments that I collected for sentences (i) through (iv) were rather heterogeneous, for some speakers co-varying with the coordinator (hem vs. ya) and for some with the position of coordination (subject vs. object). This absence of judgment stability is why I leave this possibility aside for the moment, until it can be properly investigated.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 17 | Turkish more generally seems to disallow CP recursion. Gündoğdu (2017) shows that the complementizer diye ‘saying’ occupies the C position when the clause it embeds is a reason clause, but not when it is a manner clause (in which case diye is a VP adverbial). Kesici (2019) shows that the reason clause in (i), complement of diye, cannot be questioned, suggesting the absence of CP recursion in Turkish.

Particle –mI can follow diye, but in that case, –mI does not occupy the complementizer position in the embedded clause, but is rather adjoined to the CP modifier of the matrix verb, just like it is adjoined to the DP modifier of the matrix verb in (iii):

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 18 | I would like to thank a reviewer for suggesting this formulation of the observed patterns. The same reviewer asks about the anti-licensing of Positive Polarity Items (PPIs) in NNCs. It seems to be the case that for some Turkish speakers, PPIs are anti-licensed by both local and long-distance negation. These speakers find all the examples in (i)–(ii) ungrammatical (supporting the idea that ne particles in (iib) are negative complementizers). For speakers with a more permissive grammar, conditions on anti-licensing of PPIs seem to be less strict than conditions on licensing NCIs. For such speakers PPIs are admissible in any context that does not include local negation, i.e., a PPI is licensed even if there is no finite TP/CP boundary between the PPI and its anti-licensor (negation). This is shown by the contrast in (ia–b): the PPI çoktan ‘already’ is anti-licensed by the local negation in (ia), but is allowed in an embedded nominalized clause when the matrix predicate is negated, as in (ib). The pattern of PPI anti-licensing with NNCs, shown in (ii) is also compatible with the proposed analysis of NNCs: Example (iia), in which çoktan ‘already’ is contained in a non-clausal NNC (with a negative predicate), is ungrammatical. This is expected if PPIs are anti-licensed by a local negation. The grammaticality of the comparable clausal NNC (with an affirmative predicate) in (iib) suggests that çoktan ‘already’ is not bothered by the negative complementizer in the same CP, given that the there is a finite TP boundary between the two. This is again expected, given the grammaticality of (ib).

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 19 | Interestingly, they can also appear in polar questions, provided that the question particle mI is attached to the predicate and scopes over the entire question, as in (ia). Any other placement of the question particle fails to license the NCI, as shown in (ib).

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 20 | Note that these authors classify the relevant elements as NPIs. Here, I recast their observations and generalizations in the perspective of NC. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 21 | Embedded clauses discussed here are nominalizations, headed by the morphemes –DIK (in (44), (47), and (50)) and –mA (in (45) and (48)). Even though, as a reviewer points out, such clauses may seem finite since their verbs agree with the subjects, in the generative literature on Turkish they are standardly referred to as non-finite (Erguvanlı-Taylan 1984; Csató 1990, 2010; Kornfilt 1997; Göksel and Kerslake 2005, among many others) because they exhibit a number of properties that differentiate them from tensed root clauses: The –mA clauses encode no tense whatsoever, while the temporal distinctions of the –DIK clauses are restricted to future versus non-future (without making a difference between past and present). Also, the agreement markers on the nominalized verb belong to the nominal rather than to verbal paradigm (verbal tense and aspect affixes are incompatible with –DIK and –mA). Finally, the subjects of embedded nominalized clauses are marked genitive (as opposed to subjects of root clauses, which appear in the nominative case). Another reason for treating –DIK and –mA clauses as non-finite is to set them apart from finite clausal complements, which manifest nominative subjects and full verbal agreement on the predicate, as in (43). See, however, Kornfilt (2007) for a different view. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 22 | NPIs (in the present view NCIs) are not licensed in non-finite nominalized clauses when they are factive (Kornfilt 1984, 2007; Kelepir 2001; Predolac 2017, among others).

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 23 | See Kornfilt (2003) for the original proposal that C with nominal features (dominated by a DP layer) is involved in embedded –DIK and –(y)AcAK clauses. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 24 | This is possible presumably because of the fact that embedded nominalized clauses in Turkish show many properties of DPs (such as being case-marked) and have been argued to actually be DPs (e.g., Aygen 2002, 2011; Kornfilt 2003; Gürel 2003). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 25 | Wurmbrand (2008) analyzes English (and German) NEG-nor constructions as coordination of negatives, based on, among other things, the ungrammaticality of examples like (i), which show that negation does not scope over the subject in the first conjunct (as it would have to if the structure involved a disjunction under negation).