The ‘Ands’ and ‘Buts’ in Kahlil Gibran’s English Works: A Corpus Stylistics Perspective

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Major Shapers of Gibran’s Literary Style in English

2.2. Gibran’s Sentence-Initial “Ands” and “Buts”

[New York]Beloved Mary, 17 April 1923I have been talking to you […]-so the silence was only in my hand.Your going over the galley proof of The Prophet, and with such love, was so sweet. Your blessed touch makes every page dear to me. The punctuations, the added spaces, the change of expressions in some places, the changing of “Buts” to “Ands” and the dropping of several “Ands”—all these things are just right. The one thing which I thought a great deal about, and could not see, was the rearrangement of paragraphs in Love, Marriage, Children, Giving and Clothes. I tried to read them in the new way, and somehow they seemed rather strange to my ear... I want very much to talk to you about it […] arrive?Love from Kahlil

And soon the struggle went down in his soul, and he forgot. But then Clara was not there for him, only a woman, warm, something he loved and almost worshipped, there in the dark. But it was not Clara. And she submitted to him. The naked hunger and inevitability of his loving her, something strong and blind and ruthless in its primitiveness, made the hour almost terrible to her. She knew how stark and alone he was. And she felt it was great, that he came to her. And she took him simply, because his need was bigger either than her or him. And her soul was still within her. She did this for him in his need, even if he left her. For she loved him.(Sons and Lovers, p. 397 quoted in Sotirova 2011, p. 123)

“While you’re refreshing yourself,” said the Queen, “I’ll just take the measurements.” And she took a ribbon out of her pocket, marked in inches.(Halliday and Hasan 1976, p. 235; quoted in Bell 2007, pp. 186–87)

The wettest weather has been in Preston where they have had 15 mm of rain and the driest weather has been in Ashford where there has been only 3 mm of rain.

Tom thinks that Sheila is rich but unhappy. But I have always thought that all rich people are unhappy.

“When you love you should not say, “God is in my heart”, but rather, “I am in the heart of God”.And think not you can direct the course of love, for love, if it finds you worthy, directs your course.Love has no other desire but to fulfil itself.But if you love and must needs have desires, let these be your desires:To melt and be like a running brook that sings its melody to the night. To know the pain of too much tenderness.To be wounded by your own understanding of love;And to bleed willingly and joyfully” (the underlining is my emphasis).

- Is Gibran’s use of “Ands” and “Buts” a stylistic feature of The Prophet?

- Is Gibran’s use of “Ands” and “Buts” a stylistic feature of his other English works?

- Is the use of “Ands” and “Buts” a stylistic feature specific to Gibran’s writing?

- Is there a discourse relationship between the “Ands” and “Buts” in Gibran’s writing?

3. Method

3.1. Corpus-Stylistics Analysis

3.2. Corpus, Corpus Tools, and Data Selection

“Your seeds shall live in my body,And the buds of your tomorrow shall blossom in my heart,And your fragrance shall be my breath,And together we shall rejoice through all the seasons”.

“And others came also and entreated him.But he answered them not. He only benthis head; and those who stood near sawhis tears falling upon his breast.And he and the people proceeded towardsthe great square before the temple.And there came out of the sanctuary awoman whose name was Almitra. And shewas a seeress” (the undelining is my emphasis).

3.3. Gibran’s English Corpus (GEC) Description

4. Data Analysis and Discussion

4.1. Is Gibran’s Use of “Ands” and “Buts” a Stylistic Feature of the Prophet?

4.2. Is Gibran’s Use of “Ands” and “Buts” a Stylistic Feature of His Other English Works?

*How noble is the sad heart who would sing a joyous song with joyous hearts.*He who would understand a woman, or dissect genius, or solve the mystery of silence is the very man who would wake from a beautiful dream to sit at a breakfast table.*I would walk with all those who walk. I would not stand still to watch the procession passing by.*You owe more than gold to him who serves you. Give him of your heart or serve him.*Nay, we have not lived in vain. Have they not built towers of our bones?*Let us not be particular and sectional. The poet’s mind and the scorpion’s tail rise in glory from the same earth.

Ours is the will he heralds,And ours the sovereignty he proclaims,And his love trodden courses are rivers, to the sea of our desires.We, upon the heights, in man’s sleep dream our dreams.We urge his days to part from the valley of twilightsAnd seek their fullness upon the hills.Our hands direct the tempests that sweep the worldAnd summon man from sterile peace to fertile strife,And on to triumph.

And I made a rural pen,And I stained the water clear,And I wrote my happy songsEvery child may joy to hear

4.3. Is the Use of “Ands” and “Buts” a Stylistic Feature Specific to Gibran’s Writing?

“When you love you should not say, “God is in my heart”, but rather, “I am in the heart of God”.And think not you can direct the course of love, for love, if it finds you worthy, directs your course.Love has no other desire but to fulfil itself.But if you love and must needs have desires, let these be your desires:To melt and be like a running brook that sings its melody to the night. To know the pain of too much tenderness.To be wounded by your own understanding of love;And to bleed willingly and joyfully”.

4.4. Is There a Discourse Relationship between the “Ands” and “Buts” in Gibran’s Writing?

5. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The Whelk tool provides information about how the search term is distributed across corpus files (i.e., sub-corpora). |

| 2 | Lexical associations between words in a corpus. |

| 3 | “Relative frequency per 10 k” provides relative frequency normalised to the basis of 10,000 tokens; this value is comparable across files and corpora (Brezina et al. 2020). |

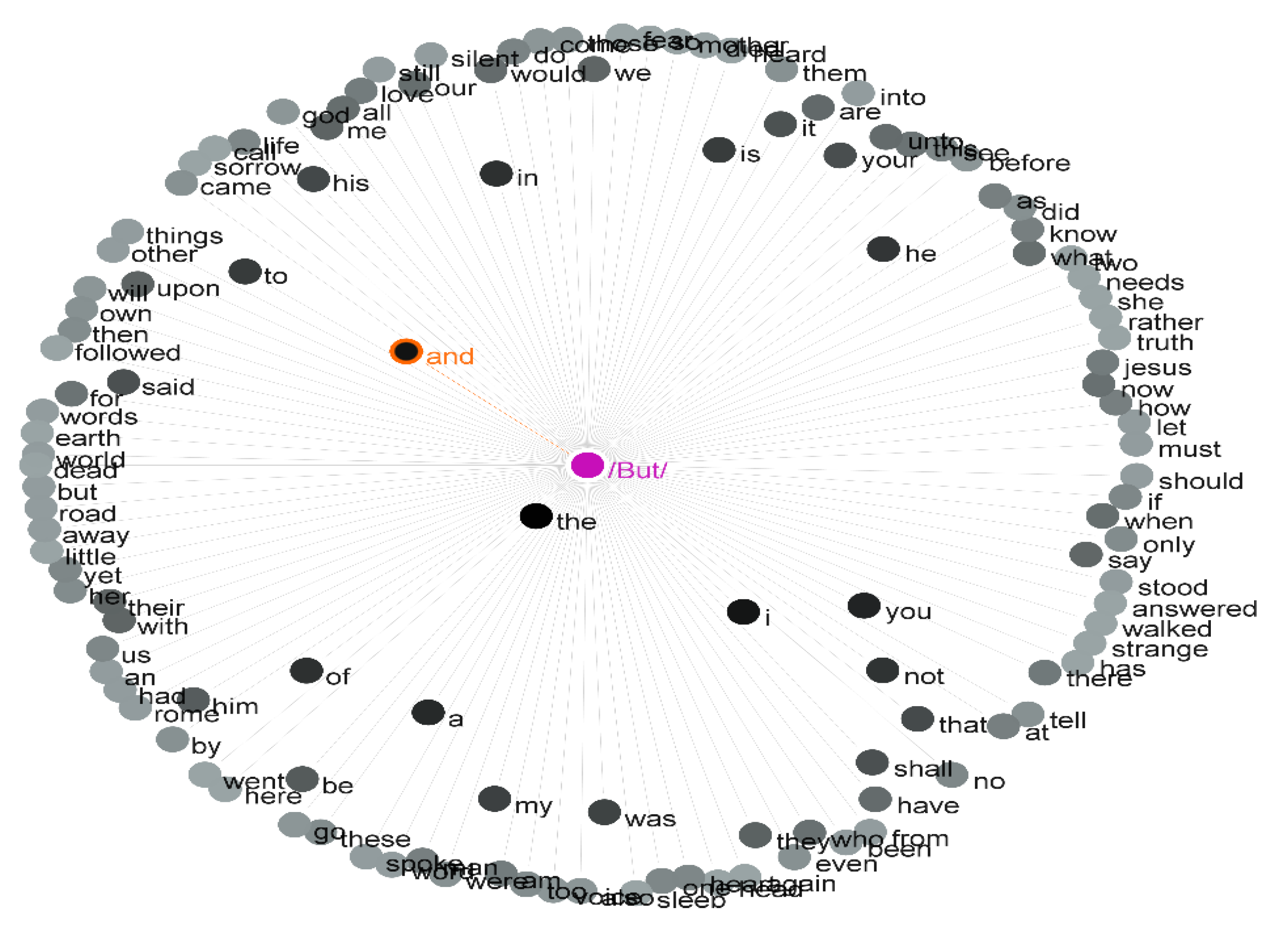

| 4 | Add to it, GraphColl plotting does not take into account capitalization. |

| 5 | As explained by Brezina et al. (2018), “the strength of collocation is indicated by the distance (length of line) between the node and the collocates. The closer the collocate is to the node, the stronger the association between the node and the collocate (‘magnet effect’)” (p. 22). |

References

- Ali, Hisham M. 2019. Beyond Reception politics of Gibran’s The Earth Gods: A symptomatic reading of two Arabic translations. Journal of Translation Studies 3: 93–113. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Saidi, Abdali H., and Abed S. Khalaf. 2022. Investigating the Aesthetic Effect in the Arabic Translations of Gibran’s The Prophet. International Journal of Asia Pacific Studies 18: 125–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshareif, Alshareif R. 2018. The Spiritual Influence of Western Writers on the First Generation of Arab-American Immigrant Writers. Unpublished Master’s thesis, University of Akron, Akron, OH, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Altabaa, Homam, Walid F. Faris, and Adham Hamawiya. 2021. A review of Kahlil Gibran’s major creative works. Journal of Islam in Asia December Issue 18: 231–53. [Google Scholar]

- Amirani, Shoku, and Stephanie Hegarty. 2012. Kahlil Gibran’s the Prophet: Why Is It So Loved? Available online: http://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-17997163 (accessed on 25 February 2023).

- Bacha, Nola. N., and Victor Khachan. 2023. A Corpus-Based Lexical Evaluation of L1 Arabic Learners’ English Literary Essays. International Journal of Arabic-English Studies 23: 415–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badran, Dany. 2010. Hybrid Genres and the Cognitive Positioning of Audiences in the Political Discourse of Hizbollah. Critical Discourse Studies 7: 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badran, Dany. 2012. Metaphor as Argument: A Stylistic Genre-based Approach. Language and Literature 21: 119–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badran, Dany. 2013. Democracy and Rhetoric in the Arab World. The Journal of the Middle East and Africa 4: 65–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, Paul. 2016. The shapes of collocations. International Journal of Corpus Linguistics 21: 139–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, David. 2007. Sentence-initial AND and BUT in academic writing. Pragmatics 17: 183–201. [Google Scholar]

- Blake, William. 1992. Songs of Innocence: And Songs of Experience. New York: Dover. [Google Scholar]

- Blakemore, Diane. 2002. Relevance and Linguistic Meaning: The Semantics and Pragmatics of Discourse Markers. Cambridge Studies in Linguistics 99. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Boushaba, Safia. 1988. An Analytical Study of Some Problems of Literary Translation: A Study of Two Arabic Translations of K. Gibran’s the Prophet. Unpublished Ph.D. thesis, University of Salford, Salford, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Brezina, Vaclav, Matt Timperley, and Tony McEnery. 2018. #LancsBox 4.x [software]. Available online: http://corpora.lancs.ac.uk/lancsbox (accessed on 21 March 2023).

- Brezina, Vaclav, Pierre Weill-Tessier, and Tony McEnery. 2020. #LancsBox 5.x and 6.x [software]. Available online: http://corpora.lancs.ac.uk/lancsbox (accessed on 21 March 2023).

- Brezina, Vaclav, Tony McEnery, and Stephen Wattam. 2015. Collocations in context: A new perspective on collocation networks. International Journal of Corpus Linguistics 20: 139–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buck, Christopher. 2010. “Kahlil Gibran”. American Writers: A Collection of Literary Biographies. Supplement XX. Farmington Hills: The Gale Group. [Google Scholar]

- Bushrui, Suheil. 2012. Kahlil Gibran, The Prophet: A New Annotated Edition. London: Oneworld Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Bushrui, Suheil, and Joe Jenkins. 1998. Kahlil Gibran: Man and Poet. London: Oneworld Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Can, Taner, and Hakan Cangir. 2021. A warring style: A corpus stylistic analysis of the First World War poetry. Digital Scholarship in the Humanities 37: 660–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, Ronald. 2004. Language and Creativity. The Art of Common Talk. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, Ronald. 2010. Methodologies for stylistic analysis: Practices and pedagogies. In Language and Style. Edited by Beatrix Busse and Dan McIntyre. Basingstoke: Palgrave Education, pp. 55–68. [Google Scholar]

- Čermáková, Anna, and Michaela Mahlberg. 2022. Gendered body language in children’s literature over time. Language and Literature 31: 11–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, Mark. 2015. Corpus of Historical American English (COHA). Cambridge: Harvard Dataverse, vol. 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorgeloh, Heidrun. 2004. Conjunction in sentence and discourse: Sentence-initial and and discourse structure. Journal of Pragmatics 36: 1761–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Hage, George N. 2013. William Blake & Kahlil Gibran: Poets of Prophetic Vision. Scotts Valley: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. [Google Scholar]

- El Hajj, Maya. 2019. Aporias in literary translation: A case study of The Prophet and its translations. Theory and Practice in Language Studies 9: 396–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Khatibi, Mourad. 2015. Challenges of literary translation: Kahlil Gibran’s The Prophet as a case study. Arab World English Journal (AWEJ) 6: 144–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farghal, Mohammed, and Bushra Kalakh. 2017. English focus structures in Arabic translation: A case study of Gibran’s The Prophet. International Journal of Arabic-English Studies (IJAES) 17: 233–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, Bruce. 2009. An account of discourse markers. International Review of Pragmatics 1: 293–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliday, Michael A.K., and Ruqaiya Hasan. 1976. Cohesion in English. London: Longman. [Google Scholar]

- Hertwig, Ralph, Bijorn Benz, and Stefan Krauss. 2008. The conjunction fallacy and the many meanings of and. Cognition 108: 740–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilu, Virginia, ed. 1972. Beloved Prophet: The Love Letters of Kahlil Gibran and Mary Haskell and Her Private Journal. New York: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. [Google Scholar]

- Hori, Masahiro. 2004. Investigating Dicken’s Style: A Collocational Analysis. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Ihrmark, Daniel, and Johan Nilsson. 2021. A corpus stylistic analysis of development in Hemingway’s literary production. The Hemingway Review 40: 71–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallay, Jeffrey E., and Melissa A. Redford. 2021. Clause-initial AND usage in a cross-sectional and longitudinal corpus of school-age children’s narratives. Journal of Child Language 48: 88–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazaraton, Anne. 1992. Linking ideas with AND in spoken and written discourse. International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching 30: 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebsir, Mohamed, and Akram Louiza. 2016. Misinterpretation in Literary Translation in Gibran Khalil Gibran’s the Prophet. Unpublished. Master’s thesis, University of Guelma, Guelma, Algeria. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, Sarah. 2015. Sentence-initial and and but in editorial writing: A comparison across Korean and American English newspapers. SNU Working Papers in English Linguistics and Language 13: 105–24. [Google Scholar]

- Mahlberg, Michaela. 2013. Corpus Stylistics and Dicken’s Fiction. Routledge Advances in Corpus Linguistics Series. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Mansour, Arwa, Belqes Al-Sowaidi, and Tawffeek Mohammed. 2014. Investigating explicitation in literary translation From English into Arabic. International Journal of Linguistics and Communication 2: 97–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntyre, Dan, and Brian Walker. 2019. Corpus Stylistics: Theory and Practice. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Naimy, Mikhail. 1985. Kahlil Gibran: A Biography by Mikhail Naimy. New York: Philosophical Library. [Google Scholar]

- Nasr, Najwa. 2001. The use of poetry in TEFL: Literature in the new Lebanese curriculum. CAUCE, Revista de Filologia y su Didactica 24: 345–63. [Google Scholar]

- Nasr, Najwa. 2018. Gibran Kahlil Gibran the Prophet: Arabic & French Translations: A Comparative Linguistic Analysis. Aajaltoun: Librairie du Liban Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Nassar, Eugene. P. 1980. Cultural Discontinuity in the Works of Kahlil Gibran. MELUS 7: 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascal, Roy. 1977. The Dual Voice. Free Indirect Speech and Its Functioning in the Nineteenth Century European Novel. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rossette, Fiona. 2013. And-Prefaced Utterances: From Speech to Text. Anglophonia/Sigma 17: 105–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, Elizabeth. 1989. The role of conjunctions and particles for text connexity’. In Text and Discourse Connectedness. Edited by Maria-Elisabeth Conte, János Sánder Petöfi and Emel Sözer. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 175–90. [Google Scholar]

- Schiffrin, Deborah. 1986. Functions of and in discourse. Journal of Pragmatics 10: 41–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiffrin, Deborah. 1987. Discourse Markers. Studies in Interactional Sociolinguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Semino, Elena, and Mick Short. 2004. Corpus Stylistics: Speech, Writing and Thought Presentation in a Corpus of English Writing. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Raoul, and William Frawley. 1983. Conjunctive cohesion in four English genres. Text 3: 347–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotirova, Violeta. 2011. D.H. Lawrence and Narrative Viewpoint. Advances in Stylistics Series. London: Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Stockwell, Peter, and Michaela Mahlberg. 2015. Mind-modelling with corpus stylistics in David Copperfield. Language and Literature 24: 129–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taha, Kelle, Marwan A. Jarrah, and Rasheed S. Al-Jarrah. 2014. The discoursal Arabic coordinating conjunction wa (and). International Journal of Linguistics 6: 172–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The King James Bible. 1604. Project Gutenberg. Retrieved 1 May 2021. Available online: https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/10/pg10 (accessed on 10 February 2023).

- Torabi Asr, Fatemeh, and Vera Demberg. 2020. Interpretation of Discourse Connectives Is Probabilistic: Evidence From the Study of But and Although. Discourse Processes 57: 376–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traugott, Elizabeth Closs. 1986. On the Origins of ‘‘and’’ and ‘‘but’’ Connectives in English. Studies in Language 10: 137–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Novel | Number of Words | Year of Publication | Genre |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. The Madman: His Parables and Poems | 6945 | 1918 | Parables and poems; 35 prose-poems |

| 2. The Forerunner: His Parables and Poems | 6904 | 1920 | Parables and poems; 25 prose-poems similar to The Madman in theme and style |

| 3. The Prophet | 12,280 | 1923 | 26 prose-poetry pieces/fables |

| 4. Sand and Foam: A Book of Aphorisms | 7172 | 1926 | A collection of life-observation aphorisms |

| 5. Jesus, the Son of Man: His Words and His Deeds as Told and Recorded by Those Who Knew Him | 40,098 | 1928 | 78 poetic/fictional portraits of Jesus (i.e., short narratives) |

| 6. The Earth Gods | 4665 | 1931 | A dialogue-structured narrative; it is a mythological dialogue between three gods in the form of prose-poems |

| 7. The Wanderer: His Parables and His Sayings | 10,909 | 1932-Posthumously | 52 parables and sayings; similar to The Madman and The Forerunner |

| 8. The Garden of the Prophet | 9140 | 1933-Posthumously | Similar format to The Prophet (prose-poetry fables) |

| 98,113 |

| JESUS THE SON.TxT | the multitudes of the kingdom of heaven. | And | He accused the scribes and the |

| JESUS THE SON.TxT | towards the north gate of the city. | And | He said to us, “My hour has |

| JESUS THE SON.TxT | followed Him, that day and the next. | And | upon the afternoon of the third day |

| JESUS THE SON.TxT | down upon the cities of the plains. | And | His face shone like molten gold, and |

| JESUS THE SON.TxT | you behold, and therein I shall rule. | And | if it is your choice, and if |

| MADMAN.txt | to their houses in fear of me. | And | when I reached the market place, a |

| MADMAN.txt | and I wanted my masks no more. | And | as if in a trance I cried, |

| MADMAN.txt | my masks.” Thus I became a madman. | And | I have found both freedom of |

| MADMAN.txt | and like a mighty tempest passed away. | And | after a thousand years I ascended the |

| MADMAN.txt | like a thousand swift wings passed away. | And | after a thousand years I climbed the |

| SAND and FOAM.txt | and lo, the mist was a worm. | And | I closed and opened my hand again, |

| SAND and FOAM.txt | again, and behold there was a bird. | And | again I closed and opened my hand, |

| SAND and FOAM.txt | man with a sad face, turned upward. | And | again I closed my hand, and when |

| SAND and FOAM.txt | and a night.” And I followed him. | And | we walked many days and many nights, |

| SAND and FOAM.txt | we did not reach the Holy City. | And | what was to my surprise he became |

| THE EARTH GODS.txt | All this have I done, and more. | And | all that I have done is empty |

| THE EARTH GODS.txt | all dark spirits we guarded the flower. | And | now that our vine hath yielded the |

| THE EARTH GODS.txt | that lieth therein is bred for gods. | And | naught but bread ungraced shall it be |

| THE EARTH GODS.txt | gods raise it not to their mouths. | And | as the mute grain turns to love |

| THE EARTH GODS.txt | GOD Aye, man is meat for gods! | And | all that is man shall come upon |

| THE FORERUNNER.txt | are but the foundation of your giant-self. | And | that self too shall be a foundation. |

| THE FORERUNNER.txt | that self too shall be a foundation. | And | I too am my own forerunner, for |

| THE FORERUNNER.txt | own forerunners, and always shall we be. | And | all that we have gathered and shall |

| THE FORERUNNER.txt | out of our eagerness dreams were born. | And | dreams were time limitless, and dreams |

| THE FORERUNNER.txt | not more, shining, than I, shone upon. | And | we, sun and earth, are but the |

| TheGardenoftheProphet.txt | which is the month of remembrance. | And | as his ship approached the harbour, he |

| TheGardenoftheProphet.txt | prow, and his mariners were about him. | And | there was a homecoming in his heart. |

| TheGardenoftheProphet.txt | there was a homecoming in his heart. | And | he spoke, and the sea was in |

| TheGardenoftheProphet.txt | once more and learn of the beginning. | And | what is there that shall live and |

| TheGardenoftheProphet.txt | a cry of remembrance and of entreaty. | And | he looked upon his mariners and said: |

| THE PROPHET CLEAN.txt | back to the isle of his birth. | And | in the twelfth year, on the seventh |

| THE PROPHET CLEAN.txt | his joy flew far over the sea. | And | he closed his eyes and prayed in |

| THE PROPHET CLEAN.txt | wings. Alone must it seek the ether. | And | alone and without his nest shall the |

| THE PROPHET CLEAN.txt | mariners, the men of his own land. | And | his soul cried out to them, and |

| THE PROPHET CLEAN.txt | often have you sailed in my dreams. | And | now you come in my awakening, which |

| THE WANDERER.txt | a veil of pain upon his face. | And | we greeted one another and I said |

| THE WANDERER.txt | to my house and be my guest. | And | he came. My wife and my children |

| THE WANDERER.txt | a silence and a mystery in him. | And | after supper we gathered to the fire |

| THE WANDERER.txt | the dust and patience of his road. | And | when he left us after three days |

| THE WANDERER.txt | met on the shore of a sea. | And | they said to one another Let us |

| JESUS THE SON.TxT | me I shall see Him no more. | But | how shall I believe what they say? |

| JESUS THE SON.TxT | His body seems to fill my arms. | But | is it not passing strange that my |

| JESUS THE SON.TxT | and raised my hand to hail Him. | But | He did not turn His face, and |

| JESUS THE SON.TxT | I was cursed, and I was envied. | But | when His dawn-eyes looked into my eyes |

| JESUS THE SON.TxT | fade away sooner than their own years. | But | I see in you a beauty that |

| MADMAN.txt | with a new and happy submission. | But | the seventh self remained watching and |

| MADMAN.txt | sides of the cloth that I weave. | But | I have a neighbour, a cobbler, who |

| MADMAN.txt | he went about looking for camels. | But | at noon he saw his shadow again--and |

| MADMAN.txt | looking for a hidden and lonely place. | But | as we walked, we saw a man |

| MADMAN.txt | sand. Great waves came and erased it. | But | he went on tracing it again and |

| SAND and FOAM.txt | the wind will blow away the foam. | But | the sea and the shore will remain |

| SAND and FOAM.txt | opened it there was naught but mist. | But | I heard a song of exceeding sweetness. |

| SAND and FOAM.txt | lie again in the dust of Egypt. | But | behold a marvel and a riddle! The |

| SAND and FOAM.txt | would not be difficult to find you. | But | should you hide behind your own shell, |

| SAND and FOAM.txt | choose the ecstasy. It is better poetry. | But | you and all my neighbors agree that |

| THE EARTH GODS.txt | the infinite would I conquer the infinite. | But | you would not do this, were it |

| THE EARTH GODS.txt | eyes the shadows of night are sleeping. | But | terrible is thy silence, And thou art |

| THE EARTH GODS.txt | not cling to that clings to me. | But | unto that that rises beyond my reach |

| THE EARTH GODS.txt | and of gods, I would be fulfilled. | But | you and I are neither human, Nor |

| THE EARTH GODS.txt | beyond, And we are the most high. | But | love is beyond our questioning, And love |

| THE FORERUNNER.txt | to himself, and he too went in. | But | what was{10} his surprise to find himself |

| THE FORERUNNER.txt | the envoy disappeared among the trees. | But | in a few minutes they returned, and |

| THE FORERUNNER.txt | true he no longer believes in me. | But | he went away much comforted.” At that |

| THE FORERUNNER.txt | tell me my faults and my shortcomings. | But | strange, not one word of reproach have |

| THE FORERUNNER.txt | triumph in disguise; and he was ashamed. | But | suddenly he raised his head, and like |

| The Garden of the Prophet.txt | that we may sing and be heard. | But | what of the wave that breaks where |

| The Garden of the Prophet.txt | walks the day between sleep and sleep. | But | I shall gaze upon the sea." And |

| The Garden of the Prophet.txt | head held high you sought the heights. | But | the sea followed after you, and her |

| The Garden of the Prophet.txt | travel ere you become one with Life. | But | of that road I shall not speak |

| The Garden of the Prophet.txt | that grow their longing for the light. | But | it is night that raises them to |

| THE PROPHET CLEAN.txt | prayed in the silences of his soul. | But | as he descended the hill, a sadness |

| THE PROPHET CLEAN.txt | take with me all that is here. | But | how shall I? A voice cannot carry |

| THE PROPHET CLEAN.txt | also. These things he said in words. | But | much in his heart remained unsaid. For |

| THE PROPHET CLEAN.txt | our faces. Much have we loved you. | But | speechless was our love, and with veils |

| THE PROPHET CLEAN.txt | no other desire but to fulfil itself. | But | if you love and must needs have |

| THE WANDERER.txt | the eagle all is well with us. | But | do you not know that we are |

| THE WANDERER.txt | might rid himself of the little bird. | But | he failed to do so. At last |

| THE WANDERER.txt | the smile of dawn upon her lips. | But | now the young men seeing her turned |

| THE WANDERER.txt | the field came unto him in greeting. | But | all the people said that his wife |

| THE WANDERER.txt | woman like unto Spring in a garden. | But | pity me and my husband for we |

| Novel | SIA | SIa | SIB | SIb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. The Madman | 137 | 13 | 27 | 2 |

| 2. The Forerunner | 146 | 19 | 10 | 2 |

| 3. The Prophet | 269 | 12 | 55 | 0 |

| 4. Sand and Foam | 48 | 11 | 17 | 11 |

| 5. Jesus, the Son of Man | 679 | 112 | 152 | 17 |

| 6. The Earth Gods | 160 | 1 | 18 | 0 |

| 7. The Wanderer | 245 | 13 | 54 | 3 |

| 8. The Garden of the Prophet | 152 | 32 | 23 | 2 |

| Total: 836 | Total: 213 | Total: 355 | Total: 37 |

| Novel | Number of Words | SIA | SIA Relative Frequency/10 K | SIB | SIB Relative Frequency/10 K |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. The Madman | 6945 | 150 | 215.982 | 29 | 41.756 |

| 2. The Forerunner | 6904 | 159 | 230.301 | 12 | 17.381 |

| 3. The Prophet | 12,280 | 228 | 185.667 | 42 | 34.201 |

| 4. Sand and Foam | 7172 | 59 | 82.264 | 28 | 39.035 |

| 5. Jesus, the Son of Man | 40,098 | 725 | 180.807 | 159 | 39.652 |

| 6. The Earth Gods | 4665 | 36 | 77.17 | 17 | 36.441 |

| 7. The Wanderer | 10,909 | 258 | 236.501 | 56 | 51.333 |

| 8. The Garden of the Prophet | 9140 | 172 | 188.183 | 25 | 27.352 |

| CORPUS | Number of Words | SIA Frequency | Relative Frequency/10 K | SIB Frequency | Relative Frequency/10 K |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. COHA SAMPLE | 2,086,612 | 5742 | 27.518 | 5320 | 25.495 |

| 2. King James Bible | 821,130 | 15,377 | 187.26 | 2033 | 24.75 |

| 3. GEC | 98,114 | 1787 | 182.13 | 368 | 37.507 |

| Novel | Number of Tokens | SIA | Non-Sentence Initial (and) | SIB | Non-Sentence Initial (but) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. The Madman | 6945 | 150 | 317 | 29 | 27 |

| 2. The Forerunner | 6904 | 159 | 306 | 12 | 32 |

| 3. The Prophet | 12,280 | 228 | 449 | 42 | 95 |

| 4. Sand and Foam | 7172 | 59 | 222 | 28 | 39 |

| 5. Jesus, the Son of Man | 40,098 | 725 | 1770 | 159 | 171 |

| 6. The Earth Gods | 4665 | 36 | 126 | 17 | 11 1 |

| 7. The Wanderer | 10,909 | 258 | 522 | 56 | 50 |

| 8. The Garden of the Prophet | 9140 | 172 | 498 | 25 | 50 |

| Total | 1787 | 4210 | 368 | 475 |

| Collocate | Frequency of Collocate | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | the | 191 |

| 2 | and | 132 |

| 3 | i | 127 |

| 4 | you | 93 |

| 5 | a | 83 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Khachan, V. The ‘Ands’ and ‘Buts’ in Kahlil Gibran’s English Works: A Corpus Stylistics Perspective. Languages 2023, 8, 246. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8040246

Khachan V. The ‘Ands’ and ‘Buts’ in Kahlil Gibran’s English Works: A Corpus Stylistics Perspective. Languages. 2023; 8(4):246. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8040246

Chicago/Turabian StyleKhachan, Victor. 2023. "The ‘Ands’ and ‘Buts’ in Kahlil Gibran’s English Works: A Corpus Stylistics Perspective" Languages 8, no. 4: 246. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8040246

APA StyleKhachan, V. (2023). The ‘Ands’ and ‘Buts’ in Kahlil Gibran’s English Works: A Corpus Stylistics Perspective. Languages, 8(4), 246. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8040246