2. Previous Studies on wa and no

Many social linguists have examined the “female” SFPs

wa and

no since the 1980s. Researchers (cf.

Cook 1987;

McGloin 1986,

2005) consistently agree that as a typical “female” SFP,

wa expresses exclamation and emphasizes emotion. Yet, some researchers (

Martin 1975;

Kitagawa 1977;

McGloin 1986) have noted that the so-called “female” SFP

wa can also be used by male speakers. The differences between

wa used by male speakers and by female speakers appear in intonation, syntax, as well as modality.

Martin (

1975) points out that

wa is overwhelmingly used by older male speakers, never associated with the polite form, and never combined with other final particles. According to

McGloin (

1986), the “female”

wa typically occurs with a rising intonation, while the “male”

wa appears with a falling intonation. More significantly, McGloin demonstrates that while the “female”

wa directs its emotional emphasis toward the addressee, the “male”

wa does not. In other words, men tend to use

wa to express their own emotions. On the other hand, contrary to the claims of previous studies, in the database of this study, it was found that up to 63% of

wa usage is by young men who are 19–22 years old rather than “older men.” In addition, cases of the “male” SFP

wa associated with the polite form and combined with other SFPs are also observed in the database of the present study.

Different from

wa, studies on the SFP particle

no are not limited by a gender perspective. Since

no is regarded to be an abbreviated form of

no da, which is a grammatical structure combining the nominalizer

no and the plain copular

da. Some linguists such as

Kamio (

1997) suggest that

no indicates that the marked proposition is a fact. By contrast,

McGloin (

1986,

2005) focuses on its gender aspects rather than its factuality by claiming that the SFP

no used in declarative sentences is mainly restricted to women, who use

no to “emphasize particular information by claiming an appearance of shared knowledge with the hearer, thereby creating rapport or involving the hearer in the conversation or the speaker’s point of view” (

McGloin 1986, p. 17). Partially agreeing with McGloin,

Cook (

1987) proposes that by using

no, the speaker indicates that they are speaking as a spokesman of the group they are a part of, and the group commonly shares the idea that what the speaker is saying is true. As a result,

no can indirectly index interpersonal harmony since the speaker shows the addressee an attitude such as, “We are in the same group, and we share the same idea”.

3. Data

This study collected data from the public database called Talkbank, which is a conversational data corpus organized by Brian MacWhinney at Carnegie Mellon University, with contributions by hundreds of researchers from various languages. Sakura in Talkbank is a Japanese Conversation Analysis section that includes 18 video-recorded conversations. Each conversation has four native participants who are college students in Japan. The participants have close relationships with each other and thus mainly use casual forms or da-tai in the conversations. They are provided with a few simple prompt questions, such as “Are you a dog-person or cat-person?” and “What do you think about international marriages?” to start the conversations. However, the speakers are allowed to go off track and change topics, so the conversations are generally freestyle and can be regarded as semi-authentic.

One of the limitations of the database is that the geographic information about the participants, such as their hometowns, is not clear. Therefore, it is difficult to identify whether the language uses in the conversations are subtly influenced by their dialects. Also, their sexual orientations or gender identities are not provided, and mostly not possible to identify in the conversations. There is a possibility that some of the speakers are LGBTQA+ individuals, which could have significantly impacted their usage of “gendered” SFPs. Yet, considering the sufficient number of participants (24 male speakers and 13 female speakers), the potential influences of dialect use or the gender identities of one or two speakers would not invalidate the overall research results of this study.

Regarding the scope of the data, please note that in the cases of no, only the SFP used in declarative sentences, as in Uchi kara chikai no “It is close to my home,” is examined. The question marker no, as in an interrogative sentence, such as Doko he iku no? “Where are you going?” is excluded from the analyses, because it is considered as a gender-neutral particle equally used by both men and women without differentiation. In addition, double SFPs, in which, wa or no co-occur with another SFP, as in Iraira suru wa na “(I am) frustrated” or Sugoi mite kuru no ne, jiitto “(He) stares at me, for a long time,” are not included in the scope of the present study. Although intonation is an important factor that has drawn many linguists’ attention in examining the gendered SFPs, due to the limitations of knowledge, training, and equipment, the specific prosodic features of the SFPs wa and no are not the focus of this study and are not investigated closely or rigorously.

To obtain gender-balanced data, this study selected 14 conversations from Sakura, including 6 conversations with two male speakers and two female speakers, 4 conversations with all male participants, and 4 conversations with all female speakers.

As shown in the last row of

Table 1, in total, among the 68 cases of the SFP

wa, 43 are produced by male speakers, which comprises 63% of the total cases, while only 37% are used by female speakers. Similarly, among the 84 cases of the SFP

no, 56% are produced by male speakers, and 44% are by female speakers. Hence, although they have been traditionally called the “female” SFPs, unexpectedly, more young men than women are using the SFPs

wa and

no in casual conversations.

4. Findings and Analysis of the SFP wa

Previous studies suggest that the SFP

wa expresses exclamation and emphasizes emotion (

Cook 1987;

McGloin 1986,

2005). The present study, based on an examination of the 68 cases in casual conversations (43 by male speakers and 25 by female speakers), also demonstrates similar functions of

wa. In particular,

wa used by both male speakers (12 of the 43 cases) and female speakers (9 of the 25 cases) frequently follows adjectives that connote feelings or emotion, as listed below:

![Languages 08 00222 i001]()

The following is an example of the male speaker IM using

wa in Line 1 and Line 3 to enforce expressiveness and emphasize his feeling of admiration:

| (1) |

| 1. | IM: | Ore, U ni shuusyoku shitai n da wa (.) iku desyo? |

| | | I U at find a job do-want NOM COP SFP go right |

| | | “I want to find a job at U. You would go, right?” |

| 2. | EF: | Nande? Ikuu? |

| | | why go |

| | | “Why? Would you go?” |

| 3. | IM: | Urayamashii wa ↗ |

| | | admiring SFP |

| | | “I am jealous of you!” |

| 4. | EM: | Hontoni? |

| | | really |

| | | “Really?” |

Note that in all the conversational excerpts in this paper, “M” appearing in the speaker pseudonym indicates the speaker is male, and “F” indicates the speaker is female.

In (1), both

tai “want to do something” and

urayamashii “admiring” attached by

wa are emotional words.

Urayamashii wa “I am jealous of you!” is produced in a rising intonation, which contradicts previous studies’ claim that the SFP

wa used by older male speakers, different from its usage by female speakers, is always associated with a falling intonation (

Martin 1975;

McGloin 1986).

In the following case, although

wa is not attached to an emotional word, it still expresses the speaker’s emotion:

| (2) |

| 1. | AM: | datte ore ga sa, koe hikui toki tte tenshon hikui toki dake da tte |

| | | because I SUB FL voice low time QM excitement low time only COP QM |

| | | “Well, people say that my voice is low only when I am depressed” |

| 2. | DM: | soo na no |

| | | so COP Q |

| | | “Is that so?” |

| 3. | CM: | tenshon hikui toki aru no? |

| | | excitement low time exist Q |

| | | “Is there time when you are depressed?” |

| 4. | AM: | aru wa |

| | | exist SFP |

| | | “There is” |

| 5. | | aru yo! ore datte nayamu toki gurai |

| | | exist SFP I even annoy time there is |

| | | “There is! Even I have hard times.” |

| 6. | DM: | fuu |

| | | oh |

| | | “Oh” |

When DM and CM tease AM by questioning if there are ever times when he is depressed or feeling down, in Line 4, AM immediately responds with

aru wa “there is”, which appears to be a quick latch-on without any pause to declare that he does have low moments. Without waiting for the addressees to respond, AM further raises his voice to rephrase it to

aru yo. Based on

McCready’s (

2005) initial idea,

Oshima (

2014) suggests that the SFP

yo with a non-rising intonation carries a function of “blame on ignorance”; that is, it is essentially used to blame the hearer for their failure to recognize the propositional content. In this context, AM uses the two SFPs,

wa and

yo, to express his emotions. However, while

yo, with a rising intonation and higher pitch in the sequence, carries a strong tone of frustration toward the addressees DM and CM, the intonation of

wa sounds like a quiet version of exclamation associated with light laughter, when the speaker AM realizes he is being teased by his peer. As pointed out by

McGloin (

1986), the SFP

wa used by male speakers more often expresses emotion toward themselves rather than toward the addressees.

The data of this study show that the SFP

wa occurs predominantly in sentences with first-person pronouns, which tend to be omitted. Meanwhile, there are also significant cases where the male pronoun

ore is overtly present in an utterance ending with the SFP

wa, as in Example (1). This indicates the SFP

wa is often used by the speaker to talk about their personal issues. In fact, the SFP

wa is not only observed in contexts when the speaker expresses strong emotion, but is also used when the speaker shares their personal information, opinions, and decisions. The distribution of such usages is summarized in

Table 2.

Half of the total 68 cases of the SFP

wa fall into this category of sharing, among which cases of

wa used by male speakers (53%) are slightly more common than cases of use by female speakers (44%). When

wa is added to the end of the sentence, instead of sharing personal information, opinions, or decisions in an objective or neutral tone, the speaker delivers the utterances with an emphasis that what they are sharing is their own thought, which often differs from those of other speakers, as in the following two examples:

| (3) |

| 1. | AM: | inugao tte. Donna kao↑ tte. iu. ka. |

| | | dog-face QM what kind face QM say Q |

| | | “What kind of face is the so-called dog-face? |

| 2. | DM: | hana ga marui n janai ? |

| | | nose SUB round NOM isn’t |

| | | “The nose is round, isn’t it?” |

| 3. | | wakaran |

| | | Know-NEG |

| | | “I don’t know” |

| 4. | AM: | inugao ga wakaran |

| | | dog-face SUB know-NEG |

| | | “I don’t know about dog-face” |

| 5. | CM: | ahaha iya neko datte marui wa |

| | | no cat even round SFP |

| | | “(laugh) No, even cats’ muzzles are round.” |

In this sequence, responding to AM’s question, “What kind of face is a dog-face?” DM suggests that a dog face has a round nose. However, in Line 5, after a laugh, CM utters a disagreement marker iya “no,” and then provides a piece of information as counter-evidence against DM’s statement; that is, a cat also has a round nose. Here, like the “female” wa, CM’s disagreement is not expressed in a defensive tone but is softened by the SFP wa.

Yet not all SFPs

wa play the role of softening the tone of the speaker’s utterance. This study found that the SFP

wa used by male speakers seems to highlight their statement with a stressed or assertive tone, which often differs from that of the previous speaker. Observe the sequence of Example (4), prior to which, GM mentions his part-time job where he works with many elderly female coworkers.

| (4) |

| 1. | IM: | jikyuu wa. ii kedo ne. |

| | | hour pay TOP good but SFP |

| | | “The hourly pay is good, though.” |

| 2. | GM: | un. |

| | | yup |

| | | “Yup.” |

| 3. | HM: | tomodachi ga dekin no? |

| | | friend SUB make-NEG Q |

| | | “Can’t you make friends?” |

| 4. | GM: | tomodachi nante iran daroo. |

| | | friend like need-NEG COP-probably |

| | | “I don’t need friends, right?” |

| 5. | HM: | baito ni tomodachi inai n da: |

| | | Part-time job at friend have-NEG NOM COP |

| | | “So you don’t have friends at the part-time job” |

| 6. | GM: | iru wa:: |

| | | there is SFP |

| | | “I have (friends)” |

| 7. | LM: | obachan bakka na n da: . |

| | | middle-aged women only COP NOM COP |

| | | “Only middle-aged women~” |

When HM comments that the job has a shortcoming that he cannot make friends, in Line 4 GM replies that he does not need friends. HM interprets GM’s response as an admission that he does not have friends at the part-time job. Immediately following HM’s utterance, in Line 6 GM disconfirms HM’s assumption by declaring that he does have friends. GM’s short claim is marked by an SFP wa that has a lengthened vowel sound to express his strong attitude of self-defense. Thus, what GM shares here (he has friends at the part-time job) is delivered as an emotional objection to HM’s accusation instead of a piece of objective information.

The “male” SFP

wa shown in previous examples appears to be a marker that is speaker-oriented by putting the speaker themselves under the spotlight or highlighting and emphasizing the speaker’s personal opinions or emotion, even if that might be against their co-participant’s stance. It has an effect similar to adding expressions such as “

I feel”, “

I think”, “

I am telling you”, and “

I know” to stress the speaker’s aspect, which lines up with

McGloin’s (

1986) claim that

wa used by male speakers is directed toward themselves. From the perspective of politeness, putting enormous focus on self may potentially make the addressees uncomfortable, and thereby could be considered to reinforce or intensify an FTA (face-threatening act) (

Brown and Levinson 1987). This appears to be the opposite of the female SFP

wa, which tends to serve as a hedging or softening politeness strategy. How could the same SFP develop divergent usages by different genders? Is there any underlying link between the apparently different functions of the “female” SFP

wa and the “male” SFP

wa?

This study suggests that the cultural concept of Amae is a crucial notion for interpreting the male usage of the SFP wa, which is the underlying link between the usages of SFP wa by female speakers and by male speakers.

The noun

amae is derived from the verb

amaeru, which means to “depend and presume upon another’s benevolence” (

Doi 1973, p. 145).

Amae is regarded as a key concept for understanding Japanese personality structure. The fundamental meaning of

amae or

amaeru is better understood through the prototype on which this concept is based; that is, an infant’s feeling toward their mother—unconditional trust, reliance, and confidence about the mother’s love and tolerance, which allow the child to be able to behave in a self-indulgent manner without feeling guilty or worrying that their mom might be angry. This kind of dependence and trusting psychological mindset is not restricted merely to family relationships between children and parents in Japanese society. In fact, it exists widely, between students and teachers, subordinates and bosses,

kohai (juniors) and

senpai (seniors), etc. Yet, as pointed out by

Wierzbicka (

1991, p. 343), although

amae seems to be associated with a “hierarchical relationship,” this term could be misleading. Rather than foregrounding the hierarchical perspective,

amae, rooted in

amai, the adjective meaning “sweet,” pictures a person’s loving and dependent attitude toward someone with whom they believe to be in an especially familiar, trusting, or

amae relationship.

Due to the long history of gender inequity and the hierarchal relations between men and women, the stereotype that women tend to rely on men and show an attitude of

amae toward men while men indulge women’s needs, has been generally accepted by society (

Marshall et al. 2011). That explains why the SFP

wa, which represents the speaker’s

amae, is normally identified as a “female” expression. However, in recent decades, women’s social status in Japanese society has been gradually improving and people’s views on gender roles have also changed, especially among younger generations. In such a social context, it does not seem inappropriate or shameful behavior anymore for men to reveal an

amae attitude to their intimate friends or significant ones, which enables the SFP

wa, formerly regarded as a “female” expression, to be used more comfortably by male speakers.

In what follows, I will use the concept of amae to examine the male speaker’s attitude/feeling toward the addressee when they add the SFP wa to the end of their utterance.

In Example (4) above, when GM hears his friend HM comment that he does not have friends at the part-time workplace, GM raises his voice to claim iru wa “I do (have friends)!” The tone and the manner in which GM makes the declaration or denial of H’s accusation would sound direct or aggressive if they were not intimate friends. The exclamatory tone of wa shows G’s belief in his friend’s tolerance of his confrontational attitude.

The following is another sequence that shows the speaker’s attitude of

amae toward the addressees:

| (5) |

| 1. | CM: | sok kara staato shita. tomodachi na no ka. |

| | | There from begin do-PST friend COP NOM Q |

| | | “Starting from there. Are they friends?” |

| 2. | BF: | kekkon. na no ka. Ren-ai na no ka. |

| | | marry COP NOM Q dating COP NOM Q |

| | | “Are they going to get married or just dating?” |

| 3. | CM: | soo. Kekkon na no ka. Renai na no ka. |

| | | Right marry COP NOM Q dating COP NOM Q |

| | | “Right. It depends on whether they will get married or are just dating.” |

| 4. | EM: | tomodachi dattara kihontekini kawan nai jan. |

| | | Friend COP-if basically change-NEG right |

| | | “If they are friends, then basically it doesn’t change anything, right?” |

| 5. | | yoi seekaku da na:: toka iroiro |

| | | good personality COP SFP etc. various |

| | | “Like good personality, etc., those things” |

| 6. | CM: | maa ii jan |

| | | well good isn’t it |

| | | “Well, isn’t it good” |

| 7. | BF: | haha (laugh) |

| 8. | EM: | °nande (.)moo shaberanai wa ↗° |

| | | Why any more chat-NEG SFP |

| | | “Why? I won’t say anymore” |

| 9. | CM: | a. soo. gomen yo. kore wa |

| | | oh really sorry SFP this TOP |

| | | “Oh really? I am sorry about this.” |

In this excerpt, the four speakers are discussing dating. As can be clearly observed from the video clip, when EM tries to express his seemingly wordy or “nerdy” opinions, in Line 6, CM cuts him off, claiming “Okay, okay, that is enough.” EM looks quite defeated and upset by CM’s discouraging comment. He asks “Why?” in line 8, and then declares moo shaberanai wa “I won’t say anything anymore,” which is like the behavior of a spoiled child, who cannot take any criticism. Note here that wa is produced in a slightly rising intonation, as most of the SFP wa utilized by female speakers.

Example (6) is another typical case of the SFP

wa used by male speakers reflecting

amae.| (6) |

| 1. | GM: | nanka aru no? |

| | | something there is Q |

| | | “Anything wrong?’ |

| 2. | HM: | are? maa ii ya. |

| | | that well okay SFP |

| | | “What? Well, that is fine.” |

| 3. | GM: | nani? nani? nani? |

| | | what what what |

| | | “What is it? What? What?” |

| 4. | HM: | iya, ii, ii, ii. |

| | | nay okay okay okay |

| | | “Nay, it is okay, it is okay, it is okay.” |

| 5. | LF: | soo iu no ga tsumannai n da yone |

| | | That say NOM SUB boring NOM COP SFP |

| | | “This kind (of person) is boring, right?”. |

| 6. | KF: | un |

| | | yeah |

| | | “Yeah” |

| 7. | HM: | iya, ima hitori de sugoku kangaeteru no |

| | | no now one person with very think-ing SFP |

| | | “No, I am just thinking by myself.” |

| 8. | GM: | dakara, nani o? |

| | | so what OBJ |

| | | “So, what are you thinking about?” |

| 9. | HM: | iya ii wa |

| | | no fine SFP |

| | | “No, it is fine.” |

| 10. | GM: | nani ga ii no? |

| | | what SUB okay Q |

| | | “What is fine?” |

Immediately prior to this sequence, it seems HM was about to say something, but he just stopped. Ignoring the other interlocutors’ repetitive queries about what is on his mind, HM refuses to share his thoughts, repetitively claiming, “it is okay, just leave me alone, I am just thinking on my own.” Stubbornly refusing to engage in the conversation is seen as an immature, childish, and self-centered reaction that is often found in children’s behavior when they face challenges or cannot take criticism from others. This type of behavior is called wagamama in Japanese, meaning “self-indulgence” or “doing whatever you want to do.” The reason that children often behave wagamama, is because deep inside of their hearts they believe the grownups love them unconditionally and would not punish them for their wagamama behaviors. Similarly, HM’s wagamama speech act in (6) also reveals his attitude of amae; that is, taking his friends’ tolerance toward his childish uncooperative behavior for granted. Interestingly, the same kind of speech act, namely, declaring withdrawal from ongoing conversations, appears multiple times in male speakers’ utterances ending with the SFP wa. In particular, two cases of ii wa “that is okay/enough” and two cases of moo shaberanai wa “I won’t talk again” are found among the 43 cases of SFP wa use by male speakers.

Another finding related to

amae is that many young male speakers use the SFP

wa to tease female addressees. There are six such cases in the present database. Examples (7) and (8) are two of them.

| (7) |

| 1. | EF: | desyoo, kyoo tyotto mensetsu ittekuru. Haha |

| | | Right today a little interview go |

| | | “Right? I am going to the interview today.” (laugh) |

| 2. | GM: | ukaran wa, tabun. |

| | | pass-NEG SFP probably |

| | | “You won’t get the job, probably.” |

| 3. | L F: | e::: e:::! |

| | | wow wow |

| | | “Wow! Wow!” |

| 4. | ALL: | hhhh |

| | | (laugh) |

When the female speaker EF mentions that she is going to have an interview for a new job, GM immediately teases her by claiming “You probably won’t get the job” with the SFP wa. The exaggerated shocked reactions and laughter by other addressees indicate that everyone acknowledges that GM’s claim is not a serious statement but intends to make fun of EF. Being able to tease someone without worrying that would offend them proves that the speaker understands that the teasing target is “teasable” and their relationship with the teasing target is intimate enough for teasing. If there were no such confidence, GM probably would not be able to tease EF in front of the group. In other words, behind the teasing, the speaker holds amae toward the addressee.

Example (8) is another teasing case, in which the participants are talking about whether friends of different genders can also hang out together even though they are not dating. The female speaker KF complains that the boys have never invited them. To this, the male speaker HM replies “I am going to pick you up” in a teasing tone.

| (8) |

| 1. | HM: | itsu demo mukae ni iku yo |

| | | When no matter welcome to go SFP |

| | | “I will go to pick you any time.” |

| 2. | KF: | konai jan nee |

| | | Come-NEG right SFP |

| | | “He won’t come, right?” |

| 3. | LF: | un |

| | | Yeah |

| | | “Yeah” |

| 4. | HM: | honto ni iku. Ja iku. Ja iku yo. Jaa iku. |

| | | Really go then go then go SFP then go |

| | | “I am really going. Then I am going. Then I am going.” |

| 5. | KF: | kureba kureba haha |

| | | Come-if come-if |

| | | “Just come, just come” (laugh) |

| 6. | HM: | jaa iku wa. nichiyoobi iku wa. |

| | | Then go SFP Sunday go SFP |

| | | “Then I am going. I am going on Sunday.” |

| 7. | KF: | nichiyoobi inai yo, tabun |

| | | Sunday stay-NEG probably |

| | | “I won’t be home on Sunday, probably” |

HM’s repetitive claim “I am going (to pick you up)” triggers the girls’ counter-teasing and laughter. Therefore, in line 6, HM adds the SFP wa declaring jaa iku wa. nichiyoobi iku wa “I am going, I am going on Sunday.” Compared with the SFP yo in Lines 1 and 4, wa is more expressive and puts more emotional stress on the propositional content, through which the speaker HM shows a strong determination. The emphasis on his personal feelings makes HM sound like amaeta or a self-indulgent kid who takes the friendship for granted to perform the teasing act. In that sense, by skillfully utilizing wa to express an attitude of amae toward the addressees, the speaker successfully maintains the rapport of the conversation and thereby strengthens their intimate relationship. The reason that the SFP wa is more likely used by male speakers to tease female speakers, rather than the other way around, would be an interesting topic to further explore from a perspective of gender psychology.

5. Data Findings and Analysis of the SFP no

As revealed in the data section, like the SFP wa, the other generally regarded as “female” SFP, no is also more often used by male speakers (56%) than by female speakers (44%) in the present database. This section examines the discourse-pragmatic functions of the SFP no, with a focus on the “male” SFP no in young Japanese people’s conversations.

Three major usages of no are identified in both men’s and women’s utterances.

To share information that is assumed to be unknown and unexpected by the addressee;

To reconfirm the speaker’s previous statement by adding more details/evidence in a reassuring tone;

To explain reasons or background situations in an assertive tone.

Note that the total number of

no in

Table 3 is 87 tokens, which is over the total number of 84 shown in

Table 1. The discrepancy is due to a few cases performing more than one of those functions. The following will provide some specific case analyses for each of the usages.

As shown in

Table 3, approximately half of the SFPs

no, either by male speakers (44%) or by female speakers (58%), are used to share new information. Two examples are given below.

In (9), four friends are talking about music and singers.

| (9) |

| 1. | DM: | kore yabee. |

| | | this marvelous |

| | | “This is marvelous.” |

| 2. | EM: | ore. mae Hirai Ken no konsaato mi ni itte-kita no. chotto |

| | | I before (singer’s name)’s concert see to go-came SFP a little |

| | | “I went to see Hirai Ken’s concert before, a little bit.” |

| 3. | | (.) un. Itte kita yo. |

| | | yeah go-came SFP |

| | | “Yeah, I went.” |

| 4. | FF: | Hirai Ken mo itta no? |

| | | also went Q |

| | | “Did you go to Hirai Ken’s concert, too?” |

When DM makes a positive comment about a song by the famous singer Hirai Ken, in Line 2, EM, instead of responding with an agreement or disagreement, unexpectedly shares his experience of going to Hirai’s concert, which was obviously not known by the other interlocutors. He marks his information sharing with the SFP

no. In addition, EM adds a hedging marker,

chotto “a little” that serves as a mitigator to soften the speaker’s impulsive acts that may threaten the addressee’s face (

Wang 2017), as well as a short pause, to mitigate the newsworthiness of the piece of news, signaling that he does not want to make a big deal of it or brag about it.

| (10) |

| 1. | MM: | hamustaa tte are yaro, akachan umu yan ne. |

| | | Hamster QM that isn’t it baby born isn’t it SFP |

| | | “Hamsters give birth to babies” |

| 2. | | akachan unnde kakushi toka nankan no yaroo |

| | | baby bear hide FL something NOM right |

| | | “After giving birth, they hide their babies” |

| 3. | | okaachan to akachan ga issyoni oru toki wa hito ga mitara |

| | | mom and baby SUB together bewhen TOP person SUB see-if |

| | | “When the mom and baby together, if they are seen by people” |

| 4. | | akanno yatte, shitte ta? |

| | | no good (dialect) know PST? |

| | | “That is not good. Do you know?” |

| 5. | IM: | nannde? |

| | | “Why?” |

| 6. | GM: | nannde? |

| | | “Why?” |

| 7. | MM: | hito ga miru to nee, okaachan ga akachan kakusoo to omotte kutte shimau no. |

| | | People SUB see if SFP mom SUB baby hide QM think eat finish SFP |

| | | “When people see them, the mom thinks she is trying to hide the babies, she eats them!” |

| 8. | IM: | ee- |

| | | (gasp) |

| 9. | HM: | ee- |

| | | (gasp) |

Example (10) is another case of no in the context of sharing information. Different from (9), the news shared in this sequence is not personal information. Instead, MM shares a shocking fact about hamsters; that is, when a little baby hamster is found by human beings, the mother hamster might try to hide her baby by eating it! Prior to revealing the final piece of information, in Line 4, MM pauses to check if the information is already known by the other interlocutors by asking “Do you know?”, which not only ensures that what he is going to share is unknown by the addressees, but also triggers their curiosity. When IM and GM eagerly inquire “Why?”, MM uses the SFP no at the end of his sharing to add more dramatic effect, seemingly to declare, “I know it is hard to believe, but it is true!”.

Tanomura (

1990) proposes that the sentence-final expression

no da in Japanese can be used by the speaker to share something behind the scenes that is not known by others, which is called

hirekisee, meaning making a disclosure or revealing a secret. Probably inherited from

no da, the SFP

no also carries the same function as a device to share newsworthy information.

Storytelling is a typical form for people to share new information. The SFP

no is often found in contexts of storytelling, in which

no occurs multiple times, as shown in the following example: In (11), the male speaker GM uses the SFP

no four times in total to vividly tell the story of his hamster. Different from the “female” SFP

no that often serves as a politeness marker by stressing “sharedness”, as previous studies (

McGloin 1986,

2005;

Cook 1987) suggest, by contrast, the “male” SFP

no in storytelling highlights the information being shared as something newsworthy or unexpected.

| (11) |

| 1. | AM | uchi no hamustaa atama ga yokatta |

| | | home ‘s hamster head SUB good-PST |

| | | “Our hamster was smart.” |

| 2. | IM: | son na no |

| | | that COP Q |

| | | “Is that so?” |

| 3. | GM: | chotto, keeji ga aru jann. de, ori ga sa. nanka fukku mitaini natte |

| | | Supe cage SUB there-is right. so cage SUB SFP FL hook like become |

| | | “Super smart. There is a cage. So the cage has a hook.” |

| 4. | | koo yatte kagi mitaini shimattearu yatsu ga. Soo iu ori datta no. |

| | | This do lock like closed stuff SUB that QM cage COP-PST SFP |

| | | “Do this, it closes like a lock. That kind of cage.” |

| 5. | | sore o gacha gacha gacha tte jibun akeru no. ↗ (0.3) |

| | | That OBJ (rattling noise) QM own open SFP |

| | | “He makes a rattling noise and opens it on his own.” |

| 6. | MM: | fufufufu |

| | | (laugh) |

| 7. | GM: | akereru hamustaa datta no (.) |

| | | open-can hamster COP-PST SFP |

| | | “It was a hamster that can open cages.” |

| 8. | IM: | tamatama gacha gacha gacha tte yattara |

| | | by chance (rattling noise) QM do-if |

| | | “If he just rattles (the cage) by chance” |

| 9. | GM: | chau chau chau moo maikai akeru kara, soko sentaku basami de tometoita no (0.) |

| | | no no no already every time open because there clothespins with fastened SFP |

| 10. | | sore irai |

| | | that from |

| | | “No, no, no, because he did that every time, since then we had to use clothespins to lock it.” |

| 11. | IM: | ee- |

| | | Wow |

| 12. | GM: | de de, sore akete, shikamo nigedashite |

| | | Then then that open furthermore escape |

| | | “Then he opened it and escaped.” |

In addition to sharing new information, male speakers often use the SFP

no to restate and reconfirm what they have said previously. For instance, in (12), the male speaker IM shares information that a kitten he once had made a strange “

nii” sound, instead of the normal cats’ purring sound, “

nyaa” in Japanese.

| (12) |

| 1. | IM: | chiichai goro saa, chiichai neko o hirotta koto ga atte saa, sodateta n da yone. |

| | | little time SFP little cat OBJ picked thing SUB there is SFP raised NOM COP SFP |

| | | “When I was little, I found a little cat and raised it.” |

| 2. | | Nii te kanji no toki ni wa moo tamaran yo. |

| | | (sound) QM feeling LK time at TOP already bear-NEG SFP |

| | | “I could not bear it when he makes ‘nii’ sound.” |

| 3. | HM: | nii tte naku no? |

| | | QM purr Q |

| | | “It purrs with ‘nii’?” |

| 4. | IM: | nii tte. naku yo. Nyaa. ja nai no. nii tte naku no. hhhh |

| | | (sound) QM purr SFP (sound) COP-NEG SFP QM purr SFP |

| | | “It purrs nii. Not nyaa, but nii.” (laugh) |

Responding to HM’s confirmative question in Line 3 “Does your cat really make

nii sound?” IM first uses the SFP

yo to inform HM that the information is in his “informational territory” (

Kamio 1997). Following that, IM uses the SFP

no twice to emphasize and reconfirm that his cat does make the sound of “

nii” instead of “

nyaa” with a more assertive tone.

The case analysis above shows that the SFP

no can deliver new and often unexpected information and add assertiveness to reconfirm information. In addition, as mentioned previously, the SFP

no is generally regarded as an abbreviated form derived from the sentence-final structure

no da, which is often used to explain reasons or the background situations (c.f.,

Tanomura 1990;

Makino and Tsutsui 1995;

Kamiya 2005). Similarly, the SFP

no is also frequently observed in the contexts of explanation. For instance, in (13), CM uses the SFP

no to explain that he does not like cats because he is allergic to them.

| (13) |

| 1. | EM: | C chan, neko ni torauma? |

| | | (name) cat to be scared |

| | | “C, are you scared of cats?” |

| 2. | HF: | koko. hhhh |

| | | “Here” (laugh) |

| 3. | CM: | neko ne… ore. neko arerugii na no |

| | | cat SFP. I cat allergy COP SFP |

| | | “Cats? I am allergic to cats.” |

Behind CM’s reasoning, there exists a common logic that CM assumes the addressees are familiar with or agree with; that is, people who are allergic to cats do not like cats.

In some cases, the logic behind the uses of the SFP

no is not as obvious as in Example (13); instead, it is hidden in the context, as in (14).

| (14) |

| 1. | LM: | otaku wa nani o oshieteru n desu ka. |

| | | you (honorific) TOP what OBJ teaching NOM COP Q |

| | | “What are you teaching?” |

| 2. | IM: | hahahhh |

| | | Hahaha (laugh) |

| 3. | GM: | see kyooiku |

| | | sex education |

| | | “Sex education” |

| 4. | IM: | chau nanka saa, reji toka uchi takunakute saa. |

| | | wrong FL FL cash register etc. hit want-NEG FL |

| | | “That is wrong. Well, I did not want to do cashier.” |

| 5. | IM: | dakara saisho juku no sensee ni shita no. |

| | | so beginning cram school ‘s teacher to did SFP |

| | | “So I decided to be a cram school teacher.” |

Prior to this sequence, IM told his friends that his first job was being a cram school teacher. LM and GM start to tease IM that the only thing he could teach would be sex education. In Line 4, IM denies this, and explains why he took the job with a statement ending with the SFP no; that is, because he did not like cashier work, he decided to be a cram school teacher. Behind the reasoning is the assumed shared acknowledgment among Japanese youth that cashiers and tutors are the most common, if not the only available, part-time jobs. Interestingly, in Example (13) the SFP no is attached to the reasoning clause, while in (14) it appears at the end of the clause of the result.

(13) “I am scared of cats, because I have cat allergy no”

(14) “I don’t like cashier work, so I decided to be a cram school teacher no”

Nonetheless, in either case, by utilizing the SFP

no, the speaker implies that their reasoning is a shared logic or common knowledge that is presumably accepted by everyone in the group or committee. Therefore, on one hand, it justifies the speaker’s reasoning as true and solid; on the other hand, as

McGloin (

1986,

2005) and

Cook (

1987) suggest, because of the aspect of sharedness,

no is often used as a positive politeness strategy to share common ground with the addressee and make the addressee feel included, and thus to create rapport in the conversation.

6. Conclusions

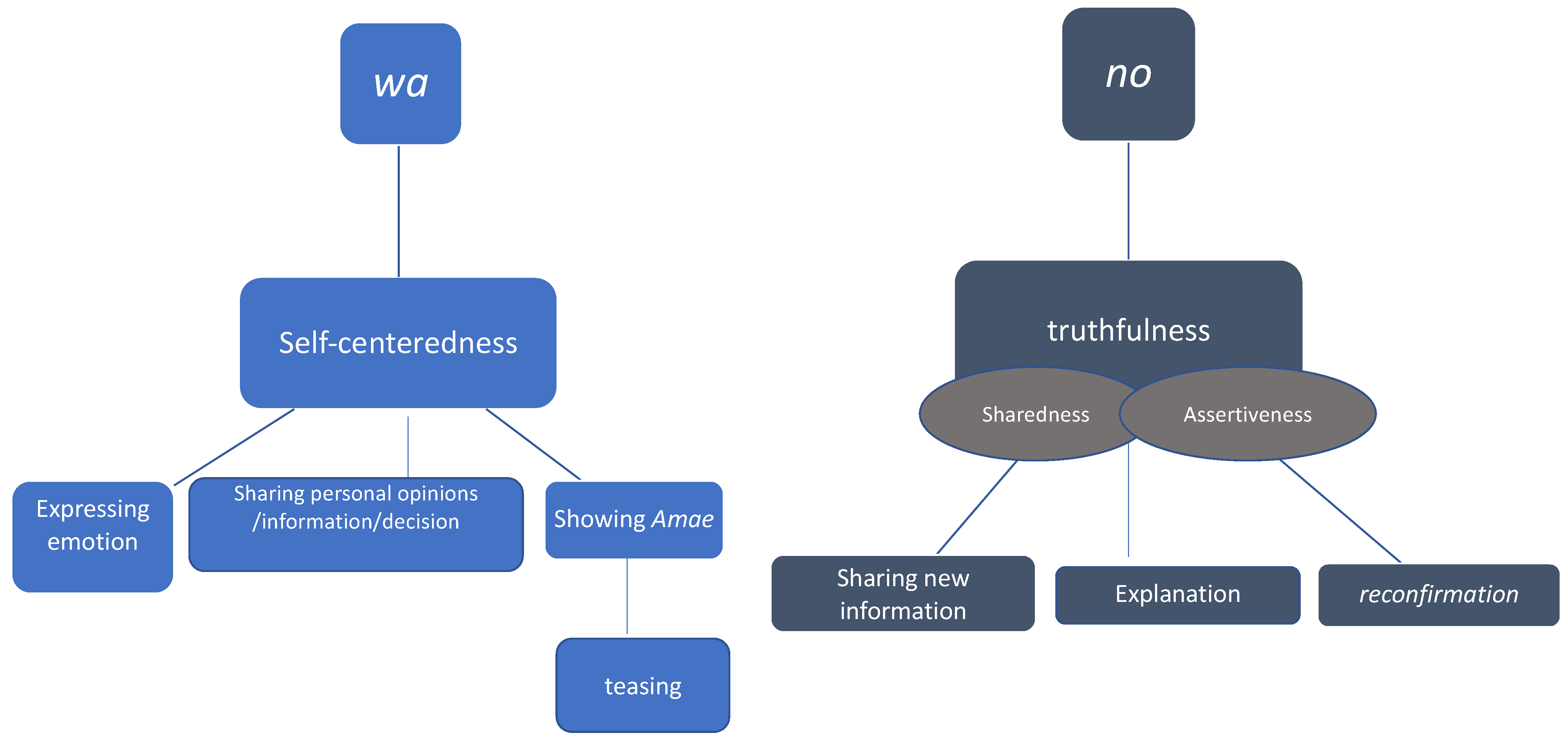

The SFPs wa and no have generally been regarded as feminine expressions that give a soft and gentle tone to the speaker’s statement. The present study examines how these so-called “female” SFPs are used by young male speakers. By analyzing their usage in multiparty conversations among Japanese college students, this study found that the SFPs wa and no do not directly index femininity; rather, they are more often used by male speakers than by female speakers among young people. It demonstrates that while the primary meanings and functions of wa mainly index the speaker’s self-centered attitude, no indexes the truthfulness of the relevant information contained in the speaker’s statement.

The following summarizes the usages of wa and no, respectively:

Like “female” usages, the SFP wa used by young male speakers is speaker-oriented, often expressing personal emotion. By overtly showing personal feelings, the “male” SFP wa can display an amae, wagamama, or egocentric attitude. Relying on amae, young male speakers can use wa to tease female speakers. In addition, wa can also be used to share personal information, decisions, or opinions by highlighting them from a self-centered perspective.

By contrast, the SFP no used by young male speakers in declaratives performs three major functions: it provides new information often presumably unexpected by the addressee, reconfirms the speaker’s prior statement, and provides explanations of the reasons or background situations. In all those usages, no has an objective tone as if the speaker is presenting a fact, and thereby it adds assertiveness to the statement. Furthermore, when used for explanation, no indicates that the logic behind the speaker’s reasoning is commonly shared among the community or society.

The graph in

Figure 1 illustrates the general picture of the multiple discourse-pragmatic functions of the SFPs

wa and

no.As shown in

Figure 1, the SFP

wa directly indexes self-centeredness, which gives it secondary functions such as expressing personal emotion, sharing personal information, opinions, or decisions, showing

amae, or teasing the other interlocutors. It does not directly index femininity. Rather, because in Japanese society women tend to be thought of as more emotional and more likely to show

amae or dependency toward men, the SFP

wa is traditionally regarded as a feminine expression. However, society changes, and now more and more young men are not hesitant to show emotion or

amae in front of people that they are close to. Thus, more and more young male speakers feel comfortable using the SFP

wa when talking with their friends.

On the other hand, the SFP no directly indexes truthfulness, and all the usages related to sharing new information, giving reconfirmation, or providing explanations are based on truthfulness. When something is presented as a fact, it triggers an assumption of sharing since truth is supposedly commonly known and accepted by most people. In certain cases, the truth can be unexpected and newsworthy, which makes the SFP no a perfect device to reveal the unknown information. Truthfulness also triggers assertiveness, because when a speaker presents what they believe to be true, they normally appear to be more confident and certain about what they are saying. Those secondary indexed meanings, including sharedness and assertiveness, qualify the SFP no as both a “female” SFP that shows the speaker’s effort to engage the addressee, as well as a “male” SFP that shows the male speaker’s assertive tone.

In short, the traditional “female” SFPs wa and no can be used by young male speakers in casual conversations in similar ways but with slight differences compared to their use by female speakers. Wa directly indexes self-centeredness, which makes it an SFP for the speaker to express emotion, share personal information, opinions, or decisions, or perform speech acts such as teasing or amae in a self-focused way. No directly indexes truthfulness, which allows its use by the speaker to share a story in a vivid tone, to reconfirm the speaker’s prior statement, or to provide the speaker’s explanation/reasoning in an assertive tone.

As

Ochs (

1992) stresses, language itself does not directly index gender. Instead, gendered usages of language are derived from the direct linguistic indexed meanings in certain social contexts. The ongoing social changes in gender norms in Japanese society today are driving language toward constant change. In other words, the “unconventional” usages of SFPs

wa and

no by young men reflect the gender and social transformations behind the language changes. That is, young men do not always conform to the traditional “masculine” style. Rather, they are more comfortable using “feminine” expressions to express their emotions or dependence on others; on the other hand, they can also flexibly utilize traditional “feminine” expressions to express their attitude of confidence or assertiveness.

“Identity is constructed in part through language” (

Siegal and Okamoto 2003, p. 59). Society is changing and individual language learners have developed more diverse perspectives and experiences regarding gender. Students should have the right to choose, form, and reveal their own identities when speaking Japanese. It is laudable that many new editions of Japanese textbooks such as

Genki (

Banno et al. 2020) and

Intermediate Japanese (

Miura and McGloin 2008) have removed gendered speech by replacing it with gender-neutral expressions in dialogues. However, this is still not sufficient. The present study of the unconventional usages of gendered expressions hopes to inspire Japanese educators to provide learners with unbiased, diverse, and authentic forms of the Japanese language, both conventional and unconventional.