Abstract

Migration is commonly described as a threat through images of invasion and flood in Western media. Migrants and asylum seekers tend to be the target of hate speech together with other vulnerable groups and minorities, such as disabled people, and definitions and labels have precise implications in terms of social justice and human rights. Migrant is an umbrella term used to refer to a variety of people who leave their countries of origin. Out-of-quota and dubliner are further labels, together with asylum seekers. Through an interdisciplinary approach, adopting a translation perspective on social justice, I would like to focus on the ways these labelling practices affect migrants’ and asylum seekers’ lives to the point of violating their rights. A clear example is represented by the English term dublined, translated as dublinati/dublinanti into Italian, and with no translation into German. It derives from the Dublin regulations, signed in 2013 and still valid, and indicates those people who want to apply for asylum in a given country but cannot do so because their fingerprints have been taken and registered in another EU country. Classifications of this kind, combined with further categorisations, such as “ordinary” or “vulnerable”, are applied throughout EU countries and languages to determine whether asylum seekers deserve, and are thus granted, asylum or not. They are informed by a dehumanizing view of migration and translate into “bordering practices” which prevent access to reception systems and welfare services. Resistant translation practices, a new language and art activism can contribute to reversing dehumanizing practices by putting displaced people’s identities at the centre. The Sicilian artist Antonio Foresta is the author of the installation Pace Nostra, a symbolic wave made of migrants’ clothes and Caltanissetta inhabitants’ bedsheets, with both an Italian and Arabic title, which translates migration, commonly perceived as “their” drama, into “our” drama, a common human experience, leading to a common goal: peace.

1. Introduction

The ways migrants and asylum seekers are defined and categorised have significant implications in terms of social justice and human rights. Migrants and asylum seekers tend to be the target of hate speech, together with other vulnerable groups and minorities, such as disabled people and are often subject to social inequalities (see, among others, De Fina 2016; Federici 2020; Taviano 2020). Through an interdisciplinary approach, adopting a translation perspective on social justice, I will first attempt to reveal how labelling practices affect migrants and asylum seekers’ lives to the point of violating their rights and later suggest how resistant arts practices, together with a new language, can contribute to reversing such dehumanizing practices by placing people’s identities at the centre (Taviano 2020; Taviano, forthcoming).

Translation is central to migration, but its social and cultural implications are often taken for granted while migrants and asylum seekers tend to be seen as passive recipients of translation in its different forms. An awareness of the way migration is “framed” (Bachmann-Medick 2018) and translated is a first step to subvert Western dehumanizing representations of migrants and asylum seekers. The role of translation as a source of resistance and a vital tool for social transformation has become central in recent scholarship (Mazzara 2019; Baker 2020; Gould and Tahmasebian 2020) leading, among other things, to a fruitful contamination between translation and social justice (Boeri and Delgado 2021; Boeri and Guo, forthcoming) with a focus on the agency and activism of translators and self-translators. Translation can be particularly powerful through the arts (Bachmann-Medick 2018; Mazzara 2019; Inghilleri and Polezzi 2020; Marinetti and De Francisci 2022). Works of art and installations by local and migrant artists, such as those analysed here, can contribute to alternative views of both translation and migration as social practices and conditions common to all human beings, thus leading to social and cultural change. Translation in these cases becomes a tool of identity construction and migrant artists as agents of self-translation (Polezzi 2020) are capable of delegitimizing predominant views of migration.

The Sicilian artist Antonio Foresta, for instance, involved citizens of the Sicilian town of Caltanissetta through his installation Pace Nostra (2020), a symbolic wave made of migrants’ clothes and local citizens’ bedsheets, to translate migration, commonly perceived as “their” drama, into “our” drama, and to convey a common human experience leading to a common goal: peace. Similarly, in 2022 the collective Ocra, with the cultural association I tetti colorati in Ragusa, Sicily, carried out InsideAut, an art project based on a relational art approach with ten migrants to encourage a rethinking of the migrant experience with the audience’ direct involvement.

2. Dehumanizing Labelling Practices and Migrants and Asylum Seekers’ Rights

The social and political implications of predominant discourses and representations of migrants and asylum seekers have been addressed by a number of linguists and translation scholars (Degli Uberti 2019; Baker 2020; Bachmann-Medick 2018; Federici 2020) who have shown how labelling practices (Degli Uberti 2019) and framing of migration (Bachmann-Medick 2018) legitimize social and political discrimination. Defining a person or a group, rather than an action they have committed, as illegal is a discursive strategy to place those people outside the polity which “indicts a person’s entire existence” (Hoops and Braitman 2019, p. 151). Immigration laws thus produce migrant “illegality” and turn it into a “quasi-inherent deficiency of migrants themselves”, (Baker 2020, p. 8) contributing to migrants’ racialization. Migrants and asylum seekers, like other minorities, are, in other words, perceived as members of a homogenous, defective group as the result of predominant social and cultural practices, thus subject to unequal treatment. This is confirmed by the current Italian government policy which, following on from that of the previous government, is based on the criminalization and imprisonment of supposed scafisti (smugglers)—accused of being responsible for smuggling irregular migrants to Italy, and who are often jailed without a trial. Interestingly enough in 2023, the Italian government also declared an emergency state to face migration flows, translating once again the emergenza migranti (migrant emergency) recurrent metaphor (see Federici 2020) into an anti-migration policy conveyed and reinforced through the media.

As I have argued elsewhere (Taviano, forthcoming), definitions of migrants, as well as being relevant in identity terms, are inevitably linked to their legal status and their rights. People who leave their countries of origin are generally defined through the umbrella term of migrants, even though their conditions and legal status might vary considerably. Asylum seeker is another term used to define migrants who cannot return to their country of origin without risking their lives, while they can be further defined through other categories, as will be shown later. According to the International Organization for Migration, Europe is the most dangerous destination in the world for irregular migrants (International Organization for Migration 2019) while, according to the Human Rights Watch, the European Frontier Security System (Eurosur), rather than identifying migrants and asylum seekers who might need humanitarian protection, mainly identifies irregular migrants who try and reach the EU by boat. However, for the IOM a commonly accepted definition of irregular migration does not exist since it can vary according to countries of origin and arrival. For instance, asylum seekers who are not granted asylum in an EU member state can appeal, but the subsequent legal procedure can last up to a year, turning them into irregular migrants who cannot travel. According to an IOM study, all these categories place migrants and asylum seekers in an unbalanced relationship with EU governments. The collection of biometric data and fingerprints is, for instance, closely connected with governments’ and police monitoring and control of migration. This procedure is negatively perceived by migrants and asylum seekers, who often fear that their personal data might be used against them by the police, as it occurs in some African countries.

EU migration policies and regulations, particularly fingerprints, have a significant impact on migrants’ and asylum seekers’ lives, as will be shown further. Asylum seekers can be classified through the English term dublined, translated as dublinati/dublinanti into Italian—while it seems to have no translation into German—according to the still-valid Dublin regulation, signed in 2013. It refers to those people who want to apply for asylum in a given country but cannot do so because their fingerprints have been taken and registered in another EU country. Fingerprints are taken in the first country of arrival, and this becomes the country where migrants should apply for asylum and stay until their application is approved. However, many asylum seekers might want to continue their journey towards other European destinations to join family members and relatives. Being classified as dublined, they run the risk of being traced and sent back to the country of arrival, including entire families whose children are attending school in that country. Classifications of this kind, combined with further categorisations, such as ordinary or vulnerable, are applied throughout EU countries according to a system whereby certain asylum seekers deserve hospitality and are thus granted asylum, while others do not. Such a system is informed by a dehumanizing view of migration, which labels people while depriving them of their humanity and translating into “bordering practices” (Degli Uberti 2019, p. 10), thus preventing access to reception systems and welfare services.

This is the case of Anas, a 27-year-old Syrian refugee, among many others, who after arriving in Lampedusa, Italy, went to Sweden looking for medical help, then to Germany where he was deported back to Italy despite having a severely injured leg. When interviewed he claimed: “I’ve lost two years of my life between Sweden and Germany. […] My only crime was that I gave my fingerprints (quoted in Reidy 2017)”. Another instance of these bordering practices occurred during a visit by the French politician Christophe Castaner at the border police station at Kehl, near Strasbourg, in 2020 as reported in the press. When Castaner used the term dublinés referring to hundreds of migrants who had been arriving in France for several years, the German policeman who acted as interpreter could not translate the term since, as he confessed, he did not know its meaning. This provoked laughter from the ministerial delegation before the policeman was told about the meaning of this neologism. While an accommodation centre had been allocated to those asylum seekers in Benfeld, the fact that the German border policeman was not aware of a term defining their legal status with subsequent laughter on the part of the delegates is a significant indication of the invisibility and a general lack of awareness of language and translation practices relating to migration policies on the part of politicians and police forces.

The neologism dublinante is one among two hundred keywords addressed by an Italian project, Parlare Civile, which aims to draw attention to language use and, in particular, derogatory terms concerning disability, gender, migration, and prostitution. Dublinante is defined as “un neologismo, un termine improprio” (a neologism, an inappropriate term) frequently used by mass media. Through a website and a book with the same title, published in 2013, Parlare Civile encourages to “comunicare senza discriminare” (communicate without discriminating), which is also the book’s subtitle, to raise awareness of the importance of language when referring to minorities and vulnerable people (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

https://www.parlarecivile.it/home.aspx, accessed on 30 May 2023.

A predominant lack of attention to language and translation practices was confirmed by the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals’ (UNSDG) failure to account for language and language diversity, as claimed in Marinotti’s final report of the 2017 Symposium on Language, the Sustainable Development Goals, and Vulnerable Populations. Marinotti’s view in relation to the UNSDGs is particularly relevant in migration contexts where multilingualism, translation and the possibility to provide correct information to migrants and professionals working in contexts of migration are taken for granted rather than enhanced:

Multilingualism, in the development community, is often seen as a translation process which occurs in the background. There is an implicit assumption that the appropriate language channels will be used to disseminate the correct and relevant information to the target populations, but little conscious consideration is given to enhancing two-way linguistic communication in the decision-making process to avoid misunderstandings or communication failures.(Marinotti 2017, p. 5)

The gap between UNSDG goals and the central role of languages and translation in migration contexts is further complicated by the spread of English as a language franca (ELF) which appears to facilitate communication. Indeed, while conveying an illusion of inclusiveness, the spread of ELF tends to overshadow linguistic and cultural differences which might prevent effective communication while reinforcing power asymmetries (Phillipson 2017; Pennycook 2006, 2017; Taviano 2019).

3. Translation and Migration as Social Conditions

While socio-labelling practices and legal classifications such as the ones analysed earlier can affect migrants’ and asylum seekers’ human rights, and reinforce social and legal vulnerability, collaborative migrant arts practices testify to “the possibilities for aesthetics to expand views of migration within both policy and cultural contexts” (Marchevska and Defrin 2023, p. 11). Through humour, for instance, migration narratives can be “flipped” and, rather than focusing on a problematic “otherness”, put forward ideas of “joyful welcome and curiosity”, in Marchevska and Defrin’s view (ibid.). Similarly, Bertacco introduces the powerful image of translation in relation to migrant artists as granting us “a transit visa to different cultures, places, and epochs” […] subverting the relationship between sameness and otherness inherent to traditional views of translation and emphasizing the foreignness in the receiver (i.e., the potential traveller)” (Bertacco 2020, p. 48).

For Bachmann-Medick, translation is not only a methodological tool, a critical lens to migration, but also “a social condition” and “a mode of existence of migration itself” (Bachmann-Medick 2018, p. 274) evident through the role of migrants as translators and active agents of translation. Migrant artists embody such active roles in the construction of their identity and their experience, as I am going to show further. Bachmann-Medick also focuses on the “multi-directional scenarios of migration”, (ibid., p. 278) referring to the diverse forms of displacement and translation’s political role to initiate processes of cultural transformation. Similarly, I am going to explore views of translation and migration which challenge traditional notions of space and direction through two collaborative art practices in two Sicilian towns, an art installation in Caltanissetta, and an arts project with migrants in Ragusa.

Before examining these two projects in detail, I would like to focus on the fact that both of them took place in Sicily, a region where, as Di Maio claims, cities like Palermo have acted “as spaces of resistance to the blatant violations of human rights entailed in Black Mediterranean practices (Di Maio 2021, p. 48)”. Palermo’s mayor, Leoluca Orlando, for instance, allowed migrants to remain in the town “independently of their status, distinguishing itself as an experimental site to rethink and challenge notions of residence, mobility, citizenship and belonging (ibid)”. Orlando, in 2015, proposed and signed the Charter of Palermo on International Human Mobility, aiming to abolish the residence permit as well as encouraging a rethinking of citizenship law, which in Italy is based on ius sanguinis, thus granting citizenship only to those who have Italian parents, rather than those who are born in Italy. As a consequence, children of non-EU migrants, born and raised in Italy, need to be eighteen before they can apply for citizenship. According to the Charter, migrants who lived in Palermo were considered citizens of Palermo, whether they had Italian citizenship or not.

In 2019, when the Italian Home Ministry Matteo Salvini introduced a Security Decree which aimed to deny migrants humanitarian protection, Orlando declared Salvini’s measures unconstitutional and in violation of human rights, and several mayors of other Italian cities, including Naples, Florence, and Milan, followed Orlando’s steps until the decree was repealed. As Di Maio argues, in this historical period municipalities can offer spaces “to experiment with equitable social practices and progressive cultural policies […] and new forms of local and global solidarity” (Di Maio 2021, p. 49). I also believe that alternative practices “that challenge hegemonic power structures, while providing spaces for equitable, progressive, and democratic cultural practices, remain one of the most concrete forms of resistance. […] Resistance, by definition, is collective (Di Maio 2021, p. 51)”. Resistance is, I believe, both individual and/or collective, as testified by the work of single artists as well as by collective relational art, as will be shown further.

4. Art Installations as Counter-Narratives on Migration

The nexus between translation and migration is expressed by Alberto Antonio Foresta’s installation, Pace Nostra, with its translational title in Arabic and Italian (Figure 2), which offers counter-narratives on migration against predominant discourses based on the binary perspective of us vs. them while redefining geographical and metaphorical spaces as a form of resistance. Foresta wants to subvert a view of migration which creates distance due to the belief that it is not our problem:

affermare che è un dramma dei migranti significa selezionare, vuol dire che non ci appartiene. E invece no, è un dramma collettivo, un dramma umano, un dramma di tutti, dell’umanità. Quindi è un dramma che ci appartiene che è anche mio, anche tuo, anche nostro (claiming that it is migrants’ drama means making a selection, it means that it does not belong to us. It is the opposite, it is a collective drama, a human drama, everybody’s drama, of all humanity. It belongs to us, it is mine, and yours, and ours).(quoted in Scarantino 2020)

Figure 2.

Courtesy of the artist.

The installation was located in a central area of Caltanissetta representing the city’s historical memory: a former shelter dating back to WW II transformed into a Contemporary Art Exhibition Centre in 2017. It was placed at the entrance of the museum, “a wave coming from the Mediterranean carrying over clothes and fabrics” (Foresta quoted in Barba 2020) and it covered a big iron serpentone (big snake). The location of the exhibition is significant and closely related to the shelter’s role as a historical memory, embodying collective and individual memories. The installation results from the interweaving of memory as well as visual translation, thus conveying Gansel’s (2017) image of translation as being connected to a geography of exile and belonging at the same time, which looks backwards to past experiences of migration as well as forward to present and future instances of migration. For Polezzi, according to such a view of geography, “no language and no place detains the exclusive right to be designated as original or to claim the absolute primacy of a point of origin (Simon and Polezzi 2022, pp. 165–66)”.

Foresta questions precisely one-directional views of hospitality and cross-cultural encounters since for him it is not just us welcoming migrants, the opposite is also true: migrants welcome our culture, and it is a reciprocal process (quoted in Scarantino 2020). Reciprocity is a key element of this installation and it is through reciprocity that binary views of migration, based on notions of original vs. translation, beginning vs. end, are called into question starting from the installation’s title. The title was in fact first composed in Arabic, with the help of a Jordanian friend, together with the corresponding Italian, “Pace Nostra”, with no clear indication of what the original and the translation is, since both the Arabic and the Italian are parts of the title in the same way. Foresta purposely created a wave carrying over migrants’ experiences all the way to the centre of a city with no sea—as emphasized by the Councilor for Culture of the time during the press conference—through migrants’ clothes and with Caltanissetta inhabitants’ sheets sown together. The image of sea waves is very powerful in conveying the fluid and complex nature of migration, and the centrality of clothes and sheets belonging to migrants and locals makes it clear that there is no us vs. them, thus turning migration into a common, shared destiny. In the same way as waves’ beginning and end points cannot be clearly identified, for Polezzi, in “the voyage of memory or the work of translation: […] no translation, no re-creation, but also no migration ever occupy the same space (Simon and Polezzi 2022, p. 164)”.

For Foresta, arts have the ability to narrate stories that we can see as well as stories that we cannot see, including the artist’s creative process. The installation was in fact the result of a long and heavy physical effort in looking for and collecting 150 m of fabric, provided by the local association, Migrantes, as well as brought from the sea and by local citizens, including clothes as well as bedsheets. As Simon argues, in conversation with Polezzi about the material experience of migration from a translation perspective, in the case of clothes evoking people who are not present, our encounters with these objects are mediated and are the result of “multiple processes of translation, both figurative and literal” (Simon and Polezzi 2022, p. 154) and “translation involves a process of reframing” (155). The first level of translation and framing is carried out by the artist and his father’s personal and physical engagement in sewing the clothes together while “bending down (Foresta quoted in Scarantino 2020)”. Foresta translates and is translated in this creative process sewing with his father, a painter, a mentor for him, because of his past experience as an artist and a tailor, who also devotes time and physical energy, translates and is translated in turn. Together they are the first to experience and embody migration’s reciprocal nature which Foresta constantly aims to convey through his art.

Caltanissetta citizens’ identities similarly go through multiple processes of translation. Their sheets first of all translate the stories of the people who used them. Foresta makes a precise choice in this sense, he reframes the material experience and migrant stories by including Italian people’s sheets since those objects tell us about the suffering and joys of those who donated them to the artist (Scarantino 2020). The installation becomes an opportunity for a further process of translation, that is translating migrants’ experience by putting oneself in their shoes, or as the Italian idiomatic expression goes, mettersi nei loro panni, by sharing their experiences and emotions through their clothes. Mediterranean waves, carrying migrants’ bodies with their clothes—in many cases without life—become Foresta’s wave carrying Italians’ sheets with them. Common expectations are thus constantly reversed and cancelled through real and metaphorical geographical and political borders, together with distinctions between first- and second-class human beings, based on Western migration systems and procedures. This process of translation and retranslation does not end with the installation—in the same way as waves do not have a clear end—since the use of fabric is a central and constant element of Foresta’s art. He received and collected more clothes than he used in the installation Pace Nostra and those which were left were later used in other works of art.

A sense of continuity links this installation with Foresta’s previous work, Mare Vostrum (Figure 3 and Figure 4), formed by a bath with yellow water, evoking African colours, with shoes of missing migrants, both in and outside the bath, and occasionally the presence of the silent artist. Dressing a bare room with strong colours was for Foresta a way to convey one of the most painful human experiences. The shock provoked by the colours evoking the origins of many migrants, and the shoes belonging to people who died crossing the Mediterranean, leave the artist, like each of us, speechless, as Figure 3 shows. Foresta’s installation, stretching back to and connecting Shoah victims to migrants who died in the Mediterranean, “congela lo spettatore in un crucciante silenzio: questo effetto lo si può sentire anche se la sala in cui è esposta è affollata” (it freezes spectators in a painful silence: this can be felt even when the exhibition room is crowded), as a critic claims (Pastorello 2019). Mare Vostrum was part of the 2019 modern art exhibition Cambio pelle (I am changing my skin) in the Contemporary Art Exhibition Centre of Caltanissetta.

Figure 3.

Mare Vostrum, courtesy of the artist.

Figure 4.

Mare Vostrum, courtesy of the artist.

As the exhibition title indicates, the artists’ aim was to encourage spectators to change their skin, way of thinking and way of interacting with the arts, with one’s own city and humanity at large. Most installations were provocative and succeeded in stimulating audiences’ response and this also occurred a year later with Pace Nostra, even before its inauguration. Many people were in fact doubtful and they initially thought that those clothes had been abandoned there or assumed that migrants who lived in the city centre had hung them to dry. By questioning the significance of those clothes, and inevitably their own views of migration, a debate around migration and around history, which repeats itself, followed. Foresta had decided to create that installation in the city centre, mainly inhabited by migrants, after the umpteenth shipwreck in the Mediterranean had caused hundreds of deaths, without purposely explaining its aim to stimulate such a debate. The audience’s interest and curiosity for Foresta’s work is a confirmation of the social role and responsibility of artists, who need to stay in society, in close contact with people while making them socially responsible, as Foresta believes (quoted in Barba 2020).

In Polezzi’s words, “artwork related to migration also asks us to interrogate ourselves as spectators, readers, viewers, about our own narratives […] It is that interpellation of us, of our position and our response which is also an integral part of re-thinking translation as co-presence, rather than substitution (Simon and Polezzi 2022, p. 159)”. Foresta’s co-creation with local citizens and migrants does this, it is a way to encourage new ways of thinking about peace and hospitality and those clothes become part of a present which is still looking for peace. It is an opportunity to go beyond labels such as “dublinante”, identifying migrants and asylum seekers through rigid categories, and to acquire an active role in defining our relationship with the Other on the basis of our individual experience as human beings. Pace Nostra continues, so to speak, and concludes through the cycle’s third work, Mediterraneo Mio (My Mediterranean, Figure 5), which represents the end, physical as well as metaphorical, of a circle, covered in clothes, in an open space, devoted to a permanent exhibition, always in Caltanissetta. It is a closed circle symbolizing the end of suffering thanks to a united mankind.

Figure 5.

Mediterraneo Mio, courtesy of the artist.

5. Translating Geographical and Human Spaces through Relational Art

The collective Ocra and the cultural association I tetti colorati (coloured roofs) in the Sicilian town of Ragusa in 2022 carried out InsideAut, an art project with 10 migrants under international protection, part of a wider initiative co-funded by the European Union and the Italian Home Ministry promoting “networks and routes towards integration”. According to European regulations, non-EU-citizens can benefit from international protection if, returning to their country, they risk persecution on grounds of religion, race, ethnicity, nationality, political opinion, or sexual orientation or they are likely to be subjected to death penalty, execution, inhuman treatment, or violence. The project was informed by a relational art approach focusing on everyday life through migrants’ works of art, encouraging social inclusion while remapping the city with the audience’s involvement. For the collective Ocra, like for Foresta, inclusion is always bidirectional and this is why both migrants and the locals were involved in the project (La Monica 2022). The Festival sociale was a true opportunity for migrants and the local community to meet and cooperate. The festival was the conclusion of a project encouraging relationships and creating new social spaces, for instance by combining migrants’ artistic work with coffee breaks in the city centre and stops in corner shops to create contacts with Ragusa citizens. Recycled materials, wood, and paper were used and the project’s slogan was “art as a pretext, relations as the final aim”. The association Laboratorio Insieme in Città participated by guiding migrants through the city to make them know the place where they lived, the city’s heart and its different neighbourhoods.

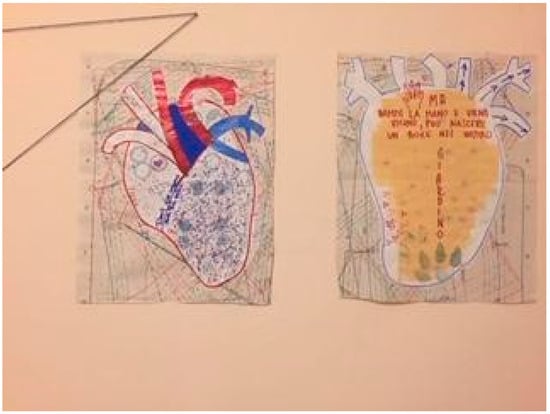

The interactive exhibition, which took place on the 10th of February 2022, offered portraits painted by migrants, working in pairs, by looking at each other with the aim to portray only some elements of the other person’s face. Those portraits were not meant to be well-defined to symbolize the fluid and complex nature of migrant identities. They were hanging at eye level forcing viewers to come into close contact with the paintings (see Figure 6 and Figure 7). As viewers entered the room where the paintings were hanging, we could not turn in the other direction and help but look at those faces very closely. The exhibition also included installations with hearts, representing both human hearts as well as the city’s heart (Figure 8), which had been reinterpreted with painted cornices and through alternative “relational maps”, including photos of migrants (Figure 7). Blue and red lines were recurrent: they were used in the portraits, in the maps and in the hearts’ veins. The heart symbolises a point of arrival and a new departure for its central role in activating emotions in relationships.

Figure 6.

InsideAut, photo by the author.

Figure 7.

InsideAut, photo by the author.

Figure 8.

InsideAut, photo by the author.

During the exhibition, each group of visitors was invited to print hands and hearts on tetrapak, a simple technique shown by the collective members (see visitors’ artistic creations in Figure 9), they were also asked to choose a favourite place in the city and to write a personal thought to be included in the new city map. The interactive nature of the exhibition, resulting from the collaboration between migrant artists and the audience, was maintained to the very end with a walk through the city during which viewers’ prints were posted to Ragusa citizens’ mailboxes.

Figure 9.

Visitors’ works, photo by the author.

6. Conclusions

The project InsideAut, like Foresta’s installations, challenges traditional notions of space in relation to migration and translation on several levels. Migrants translate their experience and identity through their artistic production in which both human profiles—their faces—and urban profiles—city maps—are not linearly defined, they are redrawn and remapped by migrants and local citizens together. Migrants and local citizens share their views and emotions through a common journey which becomes an opportunity, particularly for spectators, to interrogate themselves, their view of migration and of their own city. Human and geographical space and direction are shaped through different steps. In the same way as migrants’ identities are fluid and subject to change, throughout the project and the exhibition, people from Ragusa and other members of the audience, including myself, coming from other cities, also change, individually and socially, together with the surroundings. All people participating in the exhibition bring back home new ways of conceiving not only migration, and inclusion, but even their relationships with their own homes, their positions within their cities as well as their cities as a whole.

InsideAut, like Pace Nostra, encourages us to see and address migration not only by challenging socio-political narratives—including labelling practices, such as those examined earlier—through our position and perspective as Italians, and as Europeans, but above all through our experience as individuals. For Di Maio, if we want to make sense of our world, “every migrant should have the chance to find not only a political asylum, but first of all a human refuge (Di Maio 2021, pp. 52–53)”. If through relational art we can (re)learn to look at migrants as human beings, it is by making that experience significant in our everyday life as common citizens through new social and cultural practices that we can ensure that migrants’ voices and stories are actively told, translated, and shared.

Funding

This research received University of Messina FFABR 2021 funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No data or database are available.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Bachmann-Medick, Doris. 2018. Migration as Translation. In Migration, Changing Concepts, Critical Approaches. Edited by Doris Bachmann-Medick and Jens Kugele. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 273–94. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, Mona. 2020. Rehumanizing the migrant: The translated past as a resource for refashioning the contemporary discourse of the (radical) left. Palgrave Communications 6: 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barba, Roberta. 2020. “Pace Nostra”: Una drammatica onda di pace e speranza che parte da Caltanissetta. Il Fatto Nisseno. October 20. Available online: https://www.ilfattonisseno.it/2020/10/pace-nostra-una-drammatica-onda-di-pace-e-speranza-che-parte-da-caltanissetta/ (accessed on 25 October 2020).

- Bertacco, Simona. 2020. A Planetary Via Crucis Migration and Translation in the Work of Emily Jacir and Valeria Luiselli. Annali di Ca’ Foscari. Serie occidentale 54: 48–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeri, Julie, and Carmen Delgado. 2021. Ethics of activist translation and interpreting. In The Routledge Handbook of Translation and Ethics. Abingdon and New York: Routledge, pp. 245–61. [Google Scholar]

- Boeri, Julie, and Ting Guo, eds. Forthcoming. Translation for Social Justice: Concepts, Policies and Practices across Modalities and Contexts. Special Issue of LANS-TTS. Antwerp: Antwerp University.

- De Fina, Anna. 2016. Linguistic Practices and Transnational Identities. In The Routledge Handbook of Language and Identity. Edited by Siân Preece. Abingdon and New York: Routledge, pp. 163–78. [Google Scholar]

- Degli Uberti, Stefano. 2019. Borders within. An Ethnographic Take on the Reception Policies of Asylum Seekers in Alto Adige/South Tyrol. Archivio Antropologico Mediterraneo Anno, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Maio, Alessandra. 2021. The Black Mediterranean. Transition 132: 34–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federici, Federico. 2020. Emergenza Migranti: From Metaphor to Policy. In Translation, Interpreting and Languages in Local Crises. Edited by Christophe Declercq and Federici Federico Marco. London and New York: Bloomsbury, pp. 233–58. [Google Scholar]

- Gansel, Mireille. 2017. Translation as Transhumance. Translated by Ros Schwartz. New York: Feminist Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gould, Rebecca, and Kayvan Tahmasebian, eds. 2020. The Routledge Handbook of Translation and Activism. Abingdon and New York: Rouledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hoops, Joshua F., and Keli Braitman. 2019. The influence of immigration terminology on attribution and empathy. Critical Discourse Studies 16: 149–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inghilleri, Moira, and Loredana Polezzi. 2020. A Conversation about Translation and Migration. Cultus 13: 24–43. [Google Scholar]

- International Organization for Migration. 2019. Global Report. Geneva: International Organization for Migration. [Google Scholar]

- La Monica, Vincenzo. 2022. Arte e socialità con i migranti. Oltre i Muri. Available online: https://www.oltreimuri.blog/tag/collettivo-ocra-ragusa/ (accessed on 1 May 2023).

- Marchevska, Elena, and Carolyn Defrin. 2023. Reframing Migrant Narratives through Arts Practice. Arts 12: 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinetti, Cristina, and Enza De Francisci. 2022. Introduction: Translation and performance culture. Translation Studies 15: 247–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinotti, J. P. 2017. Symposium on Language and the Sustainable Development Goal. Final Report. New York: City University of New York. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzara, Federica. 2019. Reframing Migration. Lampedusa, Border Spectacle and Aesthetics of Subversion. Oxford and New York: Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Pastorello, Leonardo. 2019. Mare Vostrum: Un’Immagine Della Decadenza Umana. L’Antenna Online. Available online: https://lantennaonline.it/2019/07/12/mare-vostrum-unimmagine-della-decadenza-umana/ (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- Pennycook, Al. 2006. The Myth of English as an International Language. In Disinventing and Reconstructing Languages. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Pennycook, Al. 2017. The Cultural Politics of English as an International Language. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Phillipson, Robert. 2017. Myths and realities of ‘global’English. Language Policy 16: 313–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polezzi, Loredana. 2020. From Substitution to Co-presence: Translation, Memory, Trace and the Visual Practices of Diasporic Italian Artists. In Transcultural Italies, Mobility, Memory and Translation. Edited by Charles Burdett, Loredana Polezzi and Barbara Spadaro. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, pp. 317–40. [Google Scholar]

- Reidy, Eric. 2017. How a Fingerprint Can Change an Asylum Seeker’S Life. The New Humanitarian. November 21. Available online: https://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/special-report/2017/11/21/how-fingerprint-can-change-asylum-seeker-s-life???IRIN (accessed on 15 October 2020).

- Scarantino, Giulio. 2020. Pace Nostra: Il dramma dei migranti diventi il dramma dell’umanità. L’Antenna Online. Available online: https://lantennaonline.it/2020/10/15/pace-nostra-il-dramma-dei-migranti-diventi-il-dramma-dellumanita/ (accessed on 25 October 2020).

- Simon, Sherry, and Loredana Polezzi. 2022. Translation and the material experience of migration. A conversation. Translation and Interpreting Studies 17: 154–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taviano, Stefania. 2019. The Counter Narratives of Migrants and Cultural Mediators’. In Intercultural Crisis Communication. Edited by Christophe Declercq and Federico M. Federici. London: Bloomsbury Academic, pp. 21–35. [Google Scholar]

- Taviano, Stefania. 2020. The Migrant Invasion: Love Speech Against Hate Speech and the Violation of Language Rights. In Homing in on HATE: Critical Discourse Studies of Hate Speech, Discrimination and Inequality in the Digital Age. Edited by Giuseppe Balirano and Brownes Hughes. Napoli: Paolo Loffredo, pp. 247–63. [Google Scholar]

- Taviano, Stefania. Forthcoming. Translation, migration and hospitality: Painting the migrant experience with four hands. In The Routledge Handbook of Translation and Migration. Edited by Brigid Maher, Loredana Polezzi and Rita Wilson. London and New York: Routledge.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).