Abstract

Ethnolects have been defined as varieties linked to particular ethnic minorities by the minorities themselves or by other ethnic communities. The present paper investigates this association between ethnic groups and language varieties in the Greek context. I seek to answer whether there is an association made (by Albanians or Greeks) between Albanian migrants in Greece and a particular variety that is not their L1, i.e., Albanian, and if so, whether this is an Albanian ethnolect of Greek. I show experimentally that, in fact, there is a variety of Greek that is linked with listeners’ perceptions of Albanian migrants. However, that criterion is not enough in itself to designate the variety as an ethnolect as the acquisition of this variety by the second or subsequent generations of migrants is not evidenced. Rather, those generations are undergoing language shift from Albanian to Greek. Therefore, the classification of Albanian Greek as an Albanian ethnolect of Greek is not possible despite the association between the variety and the particular minority in Greece. Classification as an L2 Greek variety or a Mock Albanian Greek (MAG) variety is instead argued.

1. What Makes an Ethnolect?

There has been a considerable amount of research on ethnically based linguistic varieties, especially those that have developed in Europe, and in particular, those found in northern and western European countries (e.g., Kotsinas 1988; Kern and Selting 2011 and the works therein; Androutsopoulos 2010). This work shows that ethnolects are very similar to what have been termed ‘new varieties’ of various target languages. Both ethnolects and new varieties, thus, can be grouped under sociolects (Trudgill 2003a) since they are varieties that have been associated with particular social groups, or more broadly under lects (Bailey 1973) to frame them as patterned collections of linguistic features. However, it has not always been clear, from the scholars who use one term or the other, how the term differ because ethnolects are in their essence new varieties of a given language.

Clyne (2000, p. 86) defined ethnolects as “varieties of a language that mark speakers as members of ethnic groups who originally used another language or distinctive variety”. This definition directly associates a particular ethnolectal variety with an ethnic group and the implication is that this ethnolect has replaced another language or variety that the ethnic group used to speak. However, we know from ethnolectal work that some (but not all) ethnolect speakers can be bilingual in both the ethnolect and their ethnic or ancestral language (e.g., Fought (2002) on Chicano English and Spanish bilinguals in the U.S.). Moreover, other work shows that ethnolect speakers can at the same time be bidialectal as signaled by switches between the ethnolect and their regional majority language in different contexts (e.g., Selting (2011) on Turkish German and Berlin German bidialectal youth). Androutsopoulos (2001, p. 3), uses ‘ethnolect’ to refer to “non-native German”1 spoken by adolescents with a migrant background in Germany. The use of ethnolectal linguistic material is dynamic and exhibits variation which is conditioned by various social factors such as the identity of the addressee. For instance, Sharma (2017) found that the use of ethnolectal features increases when interlocutors are recognized as having the same ethnicity.

As with new varieties, ethnolects start with imposition (van Coetsem 1988) from the first language (L1) of the speakers that bring them about (Hinskens 2011; Clyne et al. 2001). Those imposition features that characterize the learner variety of an ethnic community, eventually become fossilized and are acquired naturally by the second, third, fourth, and so on generations (Clyne et al. 2001; Hinskens 2011). Thus, ethnolects have their own linguistic features that, together with the development of new features, set these varieties apart from learner and target varieties. With reference to the latter, British Punjabis, for instance, innovated a postalveolar /t/ in their Punjabi English which is not found in their local mainstream English variety (Sharma 2017).

Distinct features are to be found in every aspect of the ethnolect, including the morphosyntax, phonology, prosody, lexicon, etc. (e.g., Androutsopoulos 2001, 2010; Metcalf 1974; Kotsinas 1988; Selting 2011). Moreover, it is not unusual for some of these features to be found in other non-standard varieties of the majority variety.

In his own definition of ethnolect, Androutsopoulos (2010) also maintains an association between ethnolectal varieties and the ethnic minorities that speak them. This last point might be what sets apart ethnolects from other new varieties which are developed by non-migrant communities (e.g., Singapore English). Eckert (2008) takes this notion of the ethnolect a step further, by arguing that, along the same lines, majority varieties can also be labeled ethnolects. The argument is that since the variety spoken by an ethnic majority is also associated with a specific ethnic group (in this case the ethnic group is a majority rather than a minority), then thethis variety is an ethnolect as well. The association between an ethnic group and an ethnolect can happen by the ethnic group itself or other groups (Androutsopoulos 2010). Bills (1976), in discussing the status of Chicano English, puts forward the following criteria, which we could broaden to define any ethnolect regardless of the ethnicity of its speakers. First, the variation encountered in the ethnolect is not predictable if we were to look for explanations solely at the ethnic and target languages of the ethnolect speakers. Second, the variation encountered is structured. Third, the ethnolect is not a second language (L2) variety. Criterion (1) reinforces the argument that ethnolects are separate varieties, the characteristics of which one would not be able to predict based on their knowledge of the ethnic and target languages. Criterion (2) dispels misconceptions of ethnolects monoliths, but rather claims that they exhibit variation that is somehow conditioned. Finally, criterion (3) distinguishes ethnolects that are acquired natively from L2 varieties that are acquired as second or foreign languages.

Kotsinas (1988) was amongst the first to discuss youth ethnolects in the suburbs of Stockholm that the adolescents themselves called ‘Rinkebysvenska’ (i.e., Rinkeby (the name of the suburb) Swedish). Some of the features of Rinkebysvenska described by Kotsinas (1988, p. 136) include the diminishing or erasure of the ‘long-short syllable’ distinction of non-ethnolectal Swedish, the distinct pronunciation of certain phonemes, the mixing of native and non-native vocabulary, semantic change in native lexical items and phrases, and shift towards less marked structures.

The functions performed by ethnolectal use range from indexing ethnic identity (e.g., Kotsinas 1988; Clyne 2001) and familiarity with the mainstream media representations of their ethnic group (e.g., Androutsopoulos 2001), to coolness (e.g., Eckert 2008), highlighting (e.g., Selting 2011), emphasis in storytelling (Kern 2011b), semantic focus (e.g., Şimşek 2011; Ekberg 2011), solidarity with members of their community (Clyne 2001), and tough masculine identity (e.g., Madsen 2011) among a presumably infinite set of meanings that ethnolectal speakers could evoke or create.

Close examination of the use of ethnolectal features has shown variation with regards to the generation in which ethnolectal speakers belong. Sharma and Rampton (2015) illustrate how older first-generation Punjabi men in London produce higher rates of ethnolectal features when indexing their ethnic identity. Younger second-generation men seem less dexterous in their management of their ethnolectal repertoire. The authors attribute this difference to a change in the socio-historical conditions present during the upbringing of the two groups. The first generation grew up at a time of limited tolerance to cultural and linguistic diversityThe second generation was brought up at a time of greater acceptance and being surrounded by the ethnolectal features produced by the first generation. Another example of generational variation with regard to the use of the ethnolect is provided by Gnevsheva (2020) who examined style-shifting among Russians in Australia. Her research shows that the second generation exhibits variation in ethnolectal features which is used to mark their ethnicity and is compared to the first generation which does not exhibit such stylistic variation. Along similar lines, young ethnolectal speakers adopt older regional phonological features from the majority language which are currently undergoing change in the speech of the majority population (van Meel et al. 2014, 2015). For van Meel et al. (2014, 2015) these older regional features are now employed by young speakers with migrant backgrounds to index their minority ethnolinguistic identities.

Ethnolectal varieties do not always pass under the radar of the majority populations. Often members of the host country or other ethnic groups will engage in language crossing (Rampton 1995), that is, they will adopt features (usually lexical items which are easy to learn) from a given ethnolectal variety in order to achieve some of the functions discussed above (Androutsopoulos 2001; Clyne 2000; Lehtonen 2011). Ethnolects are also noticed by mass media where they get further stylized and, thus, become available to broader audiences (e.g., Androutsopoulos 2001).

Some scholars prefer to use the term ‘ethnic styles’ rather than ‘ethnolects’ focusing on the “social meaning of language variation in talk-in-interaction” (Kern 2011a, p. 7). Arguments against the term ethnolect also include intraspeaker and interspeaker variation which pose problems for varieties that assume homogeneity in those areas (Freywald et al. 2011). Madsen (2011, p. 266) even goes a step further and refers to the speech encountered in multicultural youth clubs in Copenhagen as ‘late modern youth style’ and argues that ethnic identity is not the most prominent function of the adolescents’ speech but rather “masculinity or toughness”. Although it is true that not all language production intends to index ethnic identity, completely dismissing that potential can conceal more complex underlying indexical phenomena. I argue that cases such as the one described by Madsen where ethnolectal use indexes toughness, constitute instead examples of what Silverstein (2003) would call the nth order of indexicality. As such, ethnolectal features mark one as having migrant background and, because of this association, the nth + 1 indexical order marks one as tough or masculine.

To address inter-group, inter-speaker, and intra-speaker variation, Benor (2010, 2011, 2016), proposes the ‘ethnolinguistic repertoire’ and that the field moves away from the notions of the ethnolect and ethnic variety altogether. Burdin (2021) adopts the notion of the ethnolinguistic repertoire to discuss the use of Hebrew and Yiddish in the linguistic landscapes of Poland. She shows that speakers’ varying engagement with the ethnolinguistic repertoire available to them interacts with an attemptto construct the absence or presence of the Jewish element in the country presently.

These studies on ethnolects seem to mark a shiftin linguistics where migrants are observed to be actively affecting/creating/changing the language of the majority population in their host countries. They are now seen as active agents rather than passive subjects who simply adopt or shift to the majority language. Here, I employ ‘ethnolect’ for the purposes of the paper since alternative terms such as ‘ethnolinguistic repertoire’ and ‘late modern youth style’ are not without issues (e.g., Cheshire et al. 2015).

Motivated by Androutsopoulos’ (2010) suggestion that the association between an ethnic group and a linguistic variety can happen by the ethnic group itself or by other groups, this paper examines the potential association of a Greek variety with a migrant ethnic minorty. More specifically, it examines the potential of an ethnolect of Modern Greek through the association of ways of speaking with Albanian migrants. The urban centers of southern Europe have enjoyed less attention with regard to ethnolectal work compared, for instance, to work in central Europe which was outlined above. Admittedly, central European countries have been receiving migrants for a long time now, whereas Greece became a migratory destination only in the 80s and 90s. Until then, the countrymainly exported migrants. I argue below that, although such an association between a way of speaking and Albanian migrants exists in listeners’ perceptions, there is no conventionalized Albanian ethnolect of Greek.

In what follows I discuss the landscape of migrant varieties in Greece (Section 2), the social speech perception experiment employed in this study (Section 3), and the main findings (Section 4). Finally, I relate these findings to various criteria proposed about ethnolects, I discuss the implication these have on the status of an Albanian ethnolect of Greek (Section 5), and I offer a summary of the main arguments and some concluding remarks (Section 6).

2. Migrant Varieties in Greece

Present-day Greece has been at the receiving end of various migratory waves, with migration from Albania being one of them. Albanians’ migration towards Greece started in the early 1990s after the end of the socialist regime in Albania. As a result, Albanians became by far the largest migrant group in Greece with a population of approximately half a million in a country that has a total population of fewer than 11 million individuals (Hellenic Statistical Authority 2014).

These Albanian migrants were met with an “intense xenophobic discourse” (Archakis 2020, p. 7) which was greatly facilitated by the Greek media (Kapllani and Mai 2005). As a result, Albanians in Greece have been stigmatized as “cunning”, “primitive”, “untrustworthy”, “dangerous” and “criminal” (Lazaridis and Wickens 1999, p. 648) and also have been perceived as “polluters” and “intruders” of the “pure” and “homogenous” Greek identity (Psimmenos 2001, p. 32). Although the current discourses in Greece evolve around the successful integration of Albanians and claim that their stigmatization is part of the early reception of Albanians in Greece, recent research shows that these discourses are very much present today (Pontiki et al. 2020; Ndoci 2021a). Presently, references to Albanians are occasionally blatantly xenophobic as in the case of Greek tweets (Pontiki et al. 2020) or a January 2022 comment by Nikos Evangelatos, one of the major news anchors of Greek television, who added Τι πιο σύνηθες από έναν Aλβανό με όπλο; “What is more common than an Albanian carrying a gun?” during a news report about a recent arrest of an Albanian man. Stereotypical presentations, however, take often the form of microaggression which makes them harder to identify. Such is the case of the presentation of Albanian migrants in Greek internet memes which, under the cover of humor, construct Albanians as unintelligent, aggressive, and criminal (Ndoci 2021b, forthcoming). Such presentations are not harmless as they contribute to perpetuating the ideologies through which migrants were initially stigmatized.

Those same internet memes also show that there is some awareness in Greece of the L2 Greek spoken by Albanian migrants and of certain features that constitute this variety. Internet users in Greece utilize in memes, videos, etc. certain linguistic features that they think belong to this L2 Greek variety in a -perhaps unconscious- attempt to create a Mock Albanian Greek (MAG) variety, which in turn they attribute to Albanian migrants. In actual fact, based on a corpus of memes2 produced in this way, we can deduce a set of features that make up this stereotyped variety3 (Ndoci 2021b, forthcoming). Phonological features include the substitution of Greek palatal and velar fricatives with plosives with a similar manner of articulation (e.g., [koɾtaɾi] for Standard Modern Greek (SMG) [xoɾtaɾi] “grass”), as well as the application of Albanian word stress patterns in Greek words that normally receive antepenultimate stress (e.g., [ksaˈðeɾfo] for SMG [ˈksaðeɾfo] “cousin”). Grammatical features include non-standard grammatical gender marking (e.g., use of the neuter gender instead of feminine or masculine), and omission of function words such as modal particles or definite articles). Lexical features include Albanian words and phrases embedded within Greek frames (e.g., Albanian moj (colloquial “you.FEM”) and Albanian qifsha “f-word”).

Other popular examples of MAG include the speech of the character of Elton in the Greek TV series Παρουσιάστε “Present” (Pittaras 2020) of the 2020–2021 broadcasting season and the character of Alfred in the Greek TV series Συμπέθεροι απ’ τα Τίρανα “In-laws from Tirana” of the 2021–2022 broadcasting season (Papathanasiou and Reppas 2021). Moreover, a number of YouTube videos feature stylizations of this variety in the form of comedic skits. This awareness of a set of linguistic features attributed to Albanians that leads to the inclusion of said features in media commentary bears the question of whether these non-SMG features can be associated with Albanians in spoken language. In other words, whether a particular set of linguistic features (authentic or not) is attributed to Albanian migrants and whether we can then speak, from the hearers’ perspective, of a set of features that make up an Albanian ethnolect of Greek as in Androutsopoulos’ (2010) definition. If there is an identification of the aforementioned non-SMG features with Albanians (by Albanians and/or Greeks), then in Androutsopoulos’ view we can start exploring the possible existence of an ethnolect. In the next section, I describe the methodology employed in attempting to answer this question and in testing Androutsopoulos’ proposal. I show that although there is an identification of certain phonological features with Albanians, it cannot be classified as an Albanian ethnolect of Greek. I argue that Albanian L2 Greek and MAG are more appropriate classifications.

3. Methodology

3.1. Experiment Design and Data Collection

To assess whether there exists a genuine Albanian ethnolect of Greek beyond the mainstream and social media, a social speech perception experiment was designed and conducted. The experiment tested Androutsopoulos’ (2010) proposal as his definition of ethnolect is directly related to listeners’ perceptual association of ways of speaking with specific ethnic groups. The experiment took the form of a survey that was administered online. Participants who took the survey listened to a Greek sentence and after each sentence stimulus, they answered three questions about the talker who delivered the audio stimulus. Each sentence could be played, if the participants chose to, a maximum of 3 times to avoid responses that are the result of overthinking as it could affect the spontaneity of the subjects’ responses. Sentences were produced by the talkers in their SMG pronunciations except for a certain target word in each one of the sentences. Each of the target words was produced with a phonological trait that was attributed to Albanian migrants as identified in the meme study described above (Ndoci 2021b). Some of the target words were emblematic while others were non-emblematic of Albanian speech. As emblematic are defined those lexical items that were attributed frequently (i.e., at least three times) to the speech of Albanian migrants in internet memes carrying non-SMG phonological features. As non-emblematic are defined lexical items that were not attributed to Albanians in the memes, but that present the environments in which the non-SMG phonological traits emerge. That is, in their SMG realizations, the words classified as non-emblematic present the same phones as the emblematic lexical items do in their SMG realizations and which are presented in memes with non-SMG realizations. Table 1 provides a summary of the target words tested together with an IPA transcription of their non-SMG pronunciation in which they were heard in the experiment. An SMG pronunciation is also provided for comparison. Two of the target words, the ones for ‘knife’ and ‘woman’ were tested in two non-SMG variants as both of these occurred as possible variants (or were proposed as possible variants by the stimuli producers) of the corresponding SMG fricatives. That is, the experiment tested both [mac͡çeɾi] and [makeɾi] ‘knife’, and both [ɟ͡ʝneka] and [ʒineka] ‘woman’, while all other words were heard in only one non-SMG variant. Both variants were included in the experiment to examine whether one of them behaved differently or triggered different perceptions.

Table 1.

Summary of target words with the non-SMG variants tested in the perception experiment.

After each sentence stimulus participants responded to the following three open-ended questions.

- Tell me three words or phrases about the talker that come to mind.

- What can you tell me about the talker’s origin? Be as specific as possible in your answer.

- What kind of job do you think the talker has?

The first question aimed at eliciting subjects’ ideologies about the non-SMG features they heard, the second aimed at testing the connection between the non-SMG features and a particular ethnicity, and the third at eliciting socioeconomic ideologies related to those same features and ethnicity. Not all participants responded to all the questions. For instance, some subjects avoided answering some of the questions by filling in δεν ξέρω “I don’t know”. Moreover, some subjects did not provide three words/phrases in the first questions as instructed. The responses to this question ranged from zero (i.e., “I don’t know”) to three.

The audio stimuli were produced by one woman and one man in their late 20s who are bilingual in Albanian and Greek. The talkers were born in Albania and had migrated to Greece at a young age. They provided sentence stimuli with all the target words listed in Table 1 (2 talkers × 8 stimuli). The same audio stimuli were produced in their SMG variants by four additional talkers in their late 20s and early 30s. The additional talkers were 2 Greek women and 2 Greek men born and raised in Greece, and their stimuli were used as distractors and fillers to draw participants’ attention away from the fact that the non-SMG talkers were the same two voices. Each of the four filler talkers produced three of the six filler sentences in their SMG variants (4 talkers × 3 SMG stimuli). That is, non-SMG and the SMG sentences were all included twice in the experiment, once produced by a female voice and once produced by a male voice.

All participants heard all the non-SMG sentences (n = 16). Additionally, participants heard the same sentences (n = 12) produced in their SMG variants which functioned as distractors. In total, all participants heard in a randomized order all 28 sentences and responded to 3 questions associated with each one of those sentences (28 sentences × 3 questions).

Experiment participants were recruited through social media, that is, through the personal networks of the author. Due to the piloting nature of this experiment, a total of 20 subjects completed the survey. Eight of the subjects were ethnic Albanians (individuals with origin from Albania that grew up in Greece, bilinguals in Greek and Albanian) and the other 12 were ethnic Greeks (born and raised in Greece, of Greek origin, native Greek speakers). Ages varied between 19 and 33 with a median of 25. The participants lean on the younger side of the age spectrum and results should be interpreted in the context of this information. Women made up the majority (n = 13). The group consists of highly educated individuals especially considering the age range (completion of secondary education (n = 7), undergraduate degree (n = 8), masters degree (n = 3), PhD degree (n = 2)). The survey was administered in Greek. This was used as a criterion for determining subjects’ competence in Greek and, therefore, their eligibility to participate in the study. The design assumes that subjects with no Greek knowledge would not complete a survey in which they do not understand much or anything at all, but does not guarantee it. Responses to the questions do not indicate that something of the sort occurred.

3.2. Speech Perception

The methodology employed here follows the tradition of the social perception of speech which has been very informative to those working in sociophonetics and sociolinguistic cognition in revealing many aspects of the social processing and evaluation of speech. From that literature, we know that listeners can deduce a number of information about talkers such as where they are from (e.g., Clopper and Pisoni 2004). Listeners also make social evaluative judgments about talkers, such as how strong, urban, or gay they sound assigning meaning to particular linguistic variables (e.g., Campbell-Kibler 2007). That meaning is not dependent on the linguistic variable alone but is mediated by other information the listeners can deduce about the talkers, such as their country of origin (Walker et al. 2014). More recently, attention has been paid to the control that listeners have over this processing showing, among others, that individuals cannot completely ignore voices when making evaluative judgments about individuals even when explicitly instructed to do so (Campbell-Kibler 2020). A significant contribution to this work has been that of the Matched Guise tests, a version of which is reproduced here. Matched Guise tests provided us with the ability to elicit sensitive information such as attitudes about language and language use while subjects are under the impression that they are providing attitudes about unknown talkers (Lambert et al. 1960). In the Greek context and relevant to the present study, Ntelifilippidi (2014) examined, using a Verbal Guise test, Greek listeners’ attitudes towards Albanian. The findings point towards a negative evaluation of the Albanian talkers. However, in the study none of the listeners were successful in identifying by name the language they were evaluating which raises questions about whether the subjects were reacting towards Albanian specifically, or towards a non-native language more generally.

4. Findings

4.1. Talker Origin

Starting with the ethnic origin assigned to the talkers who produced the non-SMG variants, both Albanian and Greek listeners identified the non-SMG talkers mainly as “foreigners” (34% of 320 responses (= 20 respondents × 16 non-SMG sentences)) avoiding making an explicit association with a specific ethnicity or nationality (Table 2). However, the first named country of origin identified for a quarter of the non-SMG stimuli is Albania (25%) making an explicit link between Albanians and the non-SMG variants. Looking closely at the talkers identified as Albanian, we find that Albanian and Greek participants contributed equally to these identifications with each group identifying the talker as Albanian, 39 and 40 times respectively. Approximately one in four of the talkers in the non-SMG stimuli were identified as being from either Greece (15%), Cyprus (n = 5%), Crete (n = 5%), or some Greek village (1%). This suggests that listeners are still willing to assign Greek origin to the non-SMG features they hear which is unsurprising if we consider the sentence is produced in SMG but for the one non-SMG feature it contains. Therefore, listeners are willing to put up with the one non-SMG feature and somewhat expand their tolerance for what a person of Greek origin sounds like. A small number of individuals identified the talkers as coming from other ethnic and racial groups which are present in Greece (e.g., Russia (3%), Pakistan (1%)), or from other western European countries (e.g., Italy (n = 3)). A considerable number of listeners avoids answering the question altogether by opting for “I don’t know” (9%). Comparatively, the vast majority of the SMG fillers are identified as some type of Greek (79% (240 possible responses = 20 respondents × 12 SMG filler sentences)). In some of the filler stimuli (12%), talkers are identified as having other non-Greek origin. This finding could be due to a priming effect from the non-SMG features present in the rest of the sentence stimuli of the experiment which might lead listeners to categorize SMG speakers as foreigners as well.

Table 2.

Listener-identified talker origin.

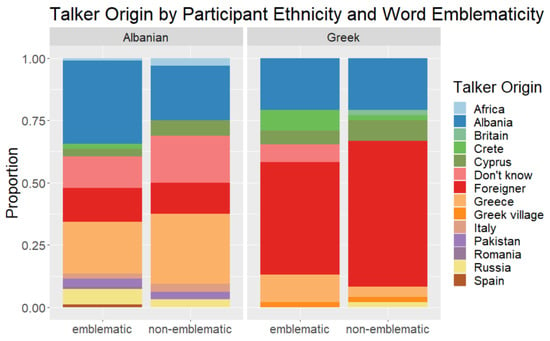

Table 3 shows that the emblematic lexical items, in general, triggered the identification of the talkers as Albanian more frequently than the non-emblematic words did. In terms of the relationship between target word emblematicity status and the origin of the talkers, it seems, at first that the proportion of the talkers identified as Albanian increases when Albanian listeners hear an emblematic target word rather than a non-emblematic one (Figure 1; Table 4). On the other hand, non-emblematic lexical items lead Greek listeners to opt for the safer “foreigner” option. The trend, however, is not confirmed by the chi-squared statistical test performed on the data in Table 4, χ2 (1, N = 79) = 0.58, p = 0.44.

Table 3.

Times each non-SMG target was identified as being produced by a talker from Albania.

Figure 1.

Proportions of listeners identified the talker’s origin by participant ethnicity and target word emblematicity type.

Table 4.

The percentage of each non-SMG target was identified as being produced by a talker from Albania by listener ethnicity and target emblematicity status.

Looking at the findings about the origin of the stimuli talkers in relation to the ethnicity of the participants, we see that Greek listeners are more prone to identifying the stimuli talkers simply as foreigners than Albanian listeners are in doing so (Figure 1). The latter listeners are comparatively more prone to identifying the talker as Albanian or even Greek. We see a tendency, then, of Greeks not making specific identifications, and of Albanians identifying the non-SMG talker as a fellow Albanian or a member of the majority community. This last finding further suggests that Albanian listeners are more tolerant than Greek listeners are about assigning non-SMG variants to Greeks.

As mentioned earlier, some lexical items were tested with two non-SMG variants. That is, SMG [maçeɾi] “knife” was tested as the non-SMG [mac͡çeɾi] and [makeɾi] and SMG [ʝineka] “woman” was tested as the non-SMG as [ɟ͡ʝineka] and [ʒineka]. For the emblematic ‘knife’ we see that the plosive variant is perceived as slightly more Albanian than the affricate variant. This might be related to the perceptually similar affricates [t͡ʃ] and [t͡ɕ] that exist in Cypriot and Cretan Greek respectively (Trudgill 2003b; Manolessou and Pantelidis 2013) which might lead listeners to classify the non-affricate, i.e., the plosive, as more Albanian.

This point relates back to an earlier finding which is the identification of the non-SMG talkers as Cypriot (5%) or Cretan (5%) by some listeners. Looking at the features that trigger those identifications we see that the affricate variant [mac͡çeɾi] is the one that exclusively triggers the Cypriot and Cretan identifications, and not the plosive (makeɾi) variant. Suggesting, that listeners are aware of the presence of a perceptually similar affricate in those regional Greek varieties which leads them to identify the non-SMG talkers as speakers of those Greek varieties. A testament to this is a comment from one of the participants who claimed to be very confident of her identification of the talker as Cretan as she had lived on the island for 3 years in her adult life. Interestingly, in Cypriot and Cretan Greek, the perceptually similar affricates occur in places where SMG has the voiceless palatal plosive [c] and not the voiceless palatal fricative [ç] which is the case with the tested [mac͡çeɾi] ‘knife’ here (Trudgill 2003b). In those latter cases, Cypriot and Cretan speakers would exhibit sibilants, i.e., they would produce [maʃeɾi] and [maɕeɾi] respectively. Moreover, Cretan identifications seem to be triggered by emblematic lexical items, although they are proportionately fewer than those that trigger Albanian identifications.

For the non-emblematic ‘woman’, the comparison between the non-SMG variants is a comparison between the affricate [ɟ͡ʝ] and the fricative [ʒ] and not between an affricate and a plosive as in ‘knife’. This experiment design choice makes the comparison between the two non-SMG variants for emblematic and non-emblematic items difficult. Yet, we are still able to observe that the affricate variant [ɟ͡ʝ] yielded the identification of the talkers as Cypriot (n = 2) and as Cretan (n = 2). The fricative [ʒ] yielded the more frequent identification of the talker as Cypriot (n = 4) and Cretan (n = 7), however. In the latter case, the identification of the fricative with the regional Greek varieties is justified as both of Cypriot and Cretan exhibit the voiced post-alveolar fricative [ʒ] in the environments where SMG exhibits the voiced palatal fricative [ʝ] found word-initially in SMG ‘woman’. A few times (n = 7) talkers were identified as Cypriot when they produced the stop variants (i.e., [kaɾa] ‘joy’ (n = 6) and [koɾtaɾi] ‘grass’ (n = 1)) in the other non-SMG stimuli. This points to a limited familiarity the listeners have with this particular Greek variety. Moreover, potential influence from the more salient Cypriot features might lead listeners to further identify talkers as Cypriot even when they do not produce stereotypically Cypriot segments.

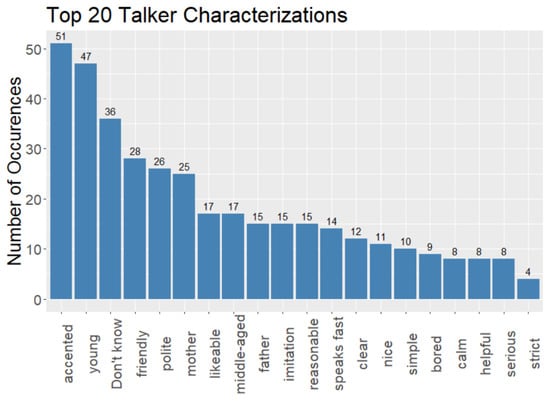

4.2. Talker Characteristics

Turning to the characterizations that the listeners provided about the talkers (Figure 2), no particularly stigmatizing descriptions associated with the non-SMG variants are found. Rather the characterizations are quite positive. In the five most frequently occurring characterizations, non-SMG talkers are judged as “accented” (n = 51/), “young” (n = 47), “friendly” (n = 28), “polite” (n = 26), and “mother[s]” (n = 25). The latter is probably due to effects of the semantic content of one of the sentence stimuli (Appendix A). A considerable number of the listeners avoid answering the question by stating “I don’t know” (n = 36). For comparison, the characterizations for the SMG fillers were very similar to the non-SMG sentences (Appendix B). Based on these findings, the internet meme study findings mentioned earlier are not reproduced here, at least not overtly. We would expect them to be so if we were to conceive memes as products of the social groups and the ideologies that participate in the construction of online spaces. In other words, internet memes and other interactions are not independent of the social structures that bring them about, and, therefore, what they communicate should correspond to attitudes found outside of online spaces as well.

Figure 2.

Top 20 talker characterizations by Albanian and Greek subjects with the number of occurrences in the data.4

How are we to interpret, then, the difference between what is found in memes and the traits provided here in relation to non-SMG? On one hand, it could be argued that the stigmatization of the variety and its speakers are not something that happens in speech. It may rather be a construct of internet users that emerges in online spaces. Another argument could be that the semantic content of the sentence stimuli was neutral enough to not yield such stigmatization (Appendix A). On the other hand, the lack of stigmatization could be interpreted as an attempt on part of the participants to avoid stereotyping and aim for more safe and politically correct evaluations5. A similar tendency is noted about AAVE in Bucholtz et al. (2007) in their work on California perceptual dialectology. Another piece of information to keep in mind is that these participants were sought through the social circles of the experimenter, which makes it likely that the subjects knew her Albanian origin which, in turn, lowers the possibility for stigmatizing or xenophobic expressions6. Having said that, the fact that (a) the characterizations provided for non-SMG talkers were along the solidarity semantic (with traits such as ‘likeable’), and (b) that we do not observe characterizations such as ‘intelligent’ or ‘educated’ of the power semantic that is also common in perception studies, suggests that for these respondents the non-SMG talkers are not associated, or could not be imagined to be associated, with power traits7.

The traits provided for the non-SMG talkers were offered mostly in response to the emblematic words rather than the non-emblematic ones and largely by Greek subjects. The one trait that was offered exclusively by Albanian listeners was that of the non-SMG talkers sounding like they are “imitating” an Albanian L2 Greek variety (n = 15). This finding perhaps explains the observation in the previous section that Albanian listeners were more likely than Greek listeners to identify the non-SGM talker as Greek.

The findings on the third survey question, namely, the perceptions of speaker profession, are not discussed here. Each profession occurred in the data only a few times and, thus, these findings were deemed inconclusive and unreliable.

5. Albanian Greek through the Lens of the ‘Ethnolect’

Broadly, the findings show that listeners who do offer specific answers such as those mentioned in Figure 1 readily recognize non-SMG talkers as Albanian8, making a direct link between ethnicity and a language variety. This link satisfies Androutsopoulos’ (2010) definition of ‘ethnolect’, therefore, offering evidence to call this variety attributed to Albanians an Albanian ethnolect of Greek. In his discussion of a Turkish German ethnolect in mainstream German media, Androutsopoulos (2001, p. 4), identifies the three stages of the “life cycle” of the ethnolect.

- Stage 1: the development of the ethnolect and crossing as a result of language contact between ethnolect speakers and majority language speakers

- Stage 2: the stylization of the ethnolect in mass media

- Stage 3: the adoption of the stylized media variety by majority language speakers.

If we were to test these stages against the non-SMG tested here, we would check off stage one since there is a variety attributed to Albanians which has its own featuresWe would check off stage two since this variety has been picked up and stylized in mass and social media which attribute the non-SMG discussed above to Albanian migrants (see Section 2). Finally, we would check off stage three as a lot of these stylizations are picked up by majority language speakers as evidenced by the popular Instagram account cjkats_9. This is an account administered by a Greek social media persona who picks up non-SMG features such as the ones discussed here and attributes them to the speech of Albanians in the comedic sketches he produces for his social media followers.

However, identifying the tested non-SMG as an ethnolect is not as straightforward as the above definition and stages suggest it is. There is no evidence for the expansion of the domains of use of this variety, its institutionalization, or any evidence that it is actively spoken and passed to the next generations of ethnic Albanian raised in Greece. Moreover, Greek scholars have already demonstrated that the second generation of Albanian migrants has actually undergone language shift becoming dominant in Greek (Gogonas 2009, 2010; Maligkoudi 2010; Chatzidaki and Xenikaki 2012; Gogonas and Michail 2015). Note, that this is an accelerated process for Albanians in Greece as language shift is typically a characteristic of the third generation of migrants (e.g., Fishman 1980; Stevens 1992), although there are counterexamples to this pattern (e.g., Spanish maintained by the fourth generation of Mexican migrants in the U.S.). Language shift together with the sociopolitical situation in Greece towards Albanian migrants, as described also in the Greek literature above, created a generation of young Albanians that wanted no association whatsoever with Albania or anything Albanian. Therefore, with the second generation of Albanian migrants being dominant in Greek, losing its ancestral language, and rejecting its Albanianness, there is little room for this generation to acquire an Albanian Greek ethnolect as its native variety10. That is, an Albanian Greek ethnolect has little opportunity to be passed on from the first to the second and third generations in the first place, and thus, it would be difficult to refer to a variety such as the one tested here as an ethnolect. This does not mean, however, that it cannot be or become at some point an actual ethnolect for the second and subsequent generations of Albanian migrants.

An alternative classification would be to call this variety an L2 Greek variety as spoken by Albanian migrants. In essence, this would mean that it is simply a variety of Greek that the first generation of Albanian migrants learned as their second language (their L1 being Albanian). The journey of this L2 Greek variety starts and ends with this first generation of migrants. The second generation has moved on to acquire Modern Greek as their first language. L2 varieties have been also called ‘learner varieties’ (e.g., Rosen 2016; Laporte 2012; Dimroth 2013) and ‘interlanguages’ (e.g., Vraciu 2013; Ulbrich and Ordin 2014; Mesthrie 2006; Aarts and Granger 2014). The term ‘interlanguage’ was introduced by Selinker in the 1970s (Selinker 1972) and is still used today almost interchangeably with ‘L2’ and ‘learner’ varieties, although it has been criticized as framing those varieties as being situated between the L1 of the learners and their L2 (their target language). Further, describing learners’ versions of their target language as consisting of “errors” (Ulbrich and Ordin 2014, p. 27; Callies 2008, p. 201) that later fossilize and give rise to an L2, is similarly problematic since it suggests that these individuals fail at producing the target language which is framed as being a perfect error-free language. Today scholars advocate for studying and viewing L2 or learner varieties as varieties in their own right (Laporte 2012; Dimroth 2013; Becker and Klein 1984). These approaches attempt to avoid evaluative characterizations that might suggest that L2 varieties are a type of failed attempt at producing the target language or that they are deficient languages. Researchers argue that these learner varieties have their own morphosyntactic, lexical, and phonological systems and, therefore should be investigated independently of native (or L1) and target languages (Klein and Perdue 1997). Since the variety attributed to Albanians has its own distinctive features (Ndoci 2021b) and is not acquired by the second generation of these migrants11, then it fits very neatly under the L2 or learner varieties term. Yet, the Albanian migration in Greece is still quite new compared to migration in northern and western Europe where ethnolects are well attested. Albanian L2 Greek might still be the basis for an Albanian ethnolect of Greek in the future. The currently available evidence indicates only language shift and dominance in Greek for the second generation of migrants.

What we are observing in the commentary about the Greek of Albanians is the salient and stereotypical features of this variety that individuals are tuning in to and attributing to a specific ethnic group. Some of the distinctive features of Albanian L2 Greek are imposition features from the L1, Albanian, of the ethnic group. Albanian phonological, grammatical, and lexical features sometimes become evident in L2 speech because speakers’ linguistic dominance remains within Albanian. As one of the reviewers very accurately points out, L1 imposition features are not the only ones that would make up an Albanian L2 variety, or any L2 variety for that matter. L2 varities also include internal innovations independent of the L1 or the L2, and linguistic features from the local L2 which learners are acquiring in the specific regions of the host country in which they have settled. Thus, another route would be to classify the variety evident in memes as a Mock Albanian Greek variety following the tradition of mock varieties. Jane Hill’s (1998) work on Mock Spanish (as produced by white Anglos) was among the first to talk about mock varieties. Although, similar phenomena predate the nineties, their racist potential had not been highlighted. Hill (1995, p. 205) defines this variety as consisting of “a set of strategies for incorporating Spanish loan words into English in order to produce a jocular or pejorative key”. Three main easy-to-identify means by which this mockery is achieved is through (ibid.):

- the semantic pejoration of Spanish expressions, by which they are stripped of elevated, serious, or even neutral meanings in the source language, retaining only the “lower” end of their range of connotations (and perhaps even adding new lowering)

- the recruitment of Spanish morphological material in order to make English words humorous or pejorating, and

- [productions of] ludicrous and exaggerated mispronunciations of Spanish loan material.

Illustrative examples for each of the above categories include (ibid.):

- “adios” [with] meanings […] ranging from a marking of laid-back, easy-going, Southwestern warmth to the strong suggestion that the target is being insulted, “kissed off.”

- mistake-o numero uno.

- grassy-ass for gracias ‘thank you’

Hill (1993) notes that Mock Spanish is used pejoratively and ironically to establish the Anglo dominance in the American Southwest, by lowering Spanish and its speakers, and by comparison, elevating whiteness which is achieved via allusion to “negative stereotypes [about] Latinos” (Hill 1995). Such mock varieties, since they are mostly covertly racist, are also to be found in mainstream media, which, keeping with the times, cannot produce or promote more overly racist content (Hill 1993). Many who use such strategies defend their choices as aiming at humor, but for humor to be achieved Spanish speakers must first be framed as “objects of derision” (Hill 1995).

Chun (2009, p. 263), in turn, discusses Mock Asian which, although there is no universal Asian language, “is a discourse that [when used by white Anglos] indexes a stereotypical Asian identity”. The qualifier ‘mock’ in this case is employed to show that the variety is used as a racializing device, that is, to frame one as a racial other (ibid.). Similar to the effects of Mock Spanish, Chun, also suggests that Mock Asian is racist because it works to elevate whiteness while, at the same time, it belittles the racial group with which this variety is stereotypically associated. For Chun instances of Mock Asian are more overtly racist than instances of Mock Spanish, which makes them less frequent, which, in turn, makes them more readily available for public critique when they occur. More recently, Jonathan Rosa (2016) explored the use of Mock Spanish practices by Latinx adolescents in the U.S. which he calls ‘Inverted Spanglish’. With such practices, adolescents do not belittle Latinx L2 English speakers but poke fun at white Anglos’ failure to produce Spanish and at the same time they assert their own Latinx and American identities.

Similarly, we could argue then, that what we observe with the tested non-SMG is an instance of a Mock Albanian Greek (MAG) variety and not an accurate Albanian L2 Greek variety. Ndoci (2021b, forthcoming), argues in favor of MAG and, among others, lists as evidence the unmotivated12 phonological adaptation of fricatives that exist in both Albanian and Greek, the unmotivated variation in the adaptation strategies of SMG-specific fricatives, and the occurrence of phonological features within a limited set of emblematic lexical items that are related to the stereotypes about Albanians. MAG, similarly, works in elevating Greekness by way of racializing and belittling Albanianness. The potential of Inverted Mock Albanian along the lines of Rosa’s (2016) Inverted Spanglish is yet to be explored, although quite plausible. The possibility of the reproduction of Mock Albanian Greek by Albanians themselves is still open. Motivations may vary based on goals of subverting racist discourses or based on internalized racism towards one’s ethnic group.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

This paper tested experimentally a non-SMG variety to investigate whether it can be typologically classified as an ethnolect along with other migrant varieties that have emerged in Europe (e.g., Kern and Selting 2011 and the works therein). Specifically, the perception experiment tested the definition offered by Androutsopoulos (2010) about ethnolects and their in-group or out-group identification with a particular ethnic group. It was shown that, at the perceptual level, there is to a large extent such a link between specific phonological and lexical features and Albanians by both members of the majority society, i.e., Greeks, and members of the community with which the speech is associated, i.e., Albanians. However, in light of the current status of Albanian in Greece (e.g., Gogonas 2009), it is argued that the classification of the tested non-SMG as an ethnolect is not a viable one as it is not conventionalized, acquired, or nativized by the second and subsequent generations. If only the first generation is linked with a variety, we are more likely observing listeners’ reactions to a learner variety, that is, their reactions to speakers who exhibit transfer from their L1, local L2 features, and features independent of L1 or L2. Alternatively, listeners’ reactions may be related to their familiarity with non-faithful representations of Albanian L2 Greek. That is, a variety that is associated with Albanians, is not completely representative of the actual Greek of Albanians, but is rather stylized and stereotyped as such. In this case, what we are most likely observing is listeners’ reactions to MAG. It should be noted that although Albanians may partially participate in MAG, the features are not completely their own.

Overall, it is found that listeners do not directly associate the tested non-SMG with negative or stigmatizing discourses. Albanian-accented speakers are associated with traits along the solidarity semantic such as ‘likeable’ and ‘friendly’. Traits such as these are common in perceptual studies. What is missing from the characterizations offered in the current study are traits along the power semantic such as ‘educated’ or ‘intelligent’ which are also common and usually occur together with solidarity traits in perception experiments that involve self-reporting in part of the subjects.

The lack of negative characterizations could suggest, on first reading, that Albanians are now successfully integrated into the Greek society and are no longer the target of xenophobic discourses. However, comments such as “What is more common than an Albanian carrying a gun?” that was uttered by the Greek anchorman in February 2022, indicate that this is far from the truth and that rather those xenophobic discourses have mostly moved from the realm of overt stigmatization to the realm of microaggression. A lot of these discourses are also latent and resurface as events involving Albanians attract the public interest. Such an example is the huge amount of xenophobic commentary that surfaced on the Greek internet also in February 2022 when it became public that an Albanian man was involved (as part of a group of 11 individuals) in the death of a Greek football fan in Thessaloniki. It might be the case, then, that the current experiment design, was not appropriate to elicit the negative attitudes found elsewhere.

Further support for the presence of the negative attitudes is offered by Ndoci (2021a, 2021b) who examined a subset of these non-SMG phonological and lexical features in a Matched Guise perception experiment. The study shows that listeners, when provided with statements such as “The talker sounds like an aggressive person” and asked to rate their agreement with it, will offer their opinion more readily rather than when prompted to provide the characterizations themselves. In other words, when listeners simply need to show their agreement with stigmatizing statements, they will do so more willingly than offer those statements. As a result, in such experiments talkers get associated with aggressiveness and criminality significantly more frequently when they produce non-SMG variants than when they produce SMG ones. Though not directly obvious from the findings of this paper, stigmatizing discourses are still present, and, given the right experimental or social setup, they make themselves visible. These do not come at no cost for Albanian migrants. Recent roundtables on Albanian Greek (Ndoci et al. 2021) and Afrogreek identity (Ampoulimen and Odoul 2020) evidence the emotional and psychological toll that stigma has on ethnic and racial groups in Greece seen as non-local. It is imperative that we, then, continue to explore such attitudes as ignoring them will not benefit the groups affected nor lead to more inclusive and equitable social structures.

Funding

This research has benefitted from a small grant by the Kenneth E. Naylor Professorship of South Slavic Linguistics at The Ohio State University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of The Ohio State University (protocol code 2020E0562, approved 27 May 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset and R code for data visualization can be made available upon request to the author.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Brian D. Joseph for his help and continuous encouragement throughout this project.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Experiment Stimuli

Table A1.

IPA Symbols Mark Pronunciation Differences between the Sentences with the Same Semantic Content. Right-Most Column Indicates the Type (Non-SMG/SMG) of the Production and the Gender of the Producer.

Table A1.

IPA Symbols Mark Pronunciation Differences between the Sentences with the Same Semantic Content. Right-Most Column Indicates the Type (Non-SMG/SMG) of the Production and the Gender of the Producer.

| Sentence Stimulus | English Translation | Stimulus Producers |

|---|---|---|

| Πάρε καλύτερα το μαcҫαίρι του ψωμιού. | You should take the bread knife. | Non-SMG male and Non-SMG female |

| Τι καλή ʒυναίκα που είναι η Μαρία. | Maria is such a nice woman. | Non-SMG male and Non-SMG female |

| Θα πάμε τα παιδιά στην παιδική kαρά το απόγευμα. | We will take the kids to the park in the afternoon. | Non-SMG male and Non-SMG female |

| Πρέπει να κόψουμε το kορτάρι στον κήπο. | We need to cut the grass in the yard. | Non-SMG male and Non-SMG female |

| Πάρε καλύτερα το μαkαίρι του ψωμιού. | You should take the bread knife. | Non-SMG male and Non-SMG female |

| Το gάλα είναι στο ψυγείο. | The milk is in the fridge. | Non-SMG male and Non-SMG female |

| Πήραμε ένα μεgάλο τραπέζι για την κοζίνα. | We bought a big table for the kitchen. | Non-SMG male and Non-SMG female |

| Τι καλή ɟʝυναίκα που είναι η Μαρία. | Maria is such a nice woman. | Non-SMG male and Non-SMG female |

| Θα παμε τα παιδιά στην παιδική χαρά το απόγευμα. | We will take the kids to the park in the afternoon. | Filler SMG male 1 and Filler SMG female 1 |

| Πρέπει να κόψουμε το χορτάρι στον κήπο. | We need to cut the grass in the yard. | Filler SMG male 1 and Filler SMG female 1 |

| Πάρε καλύτερα το μαχαίρι του ψωμιού. | You should take the bread knife. | Filler SMG male 1 and Filler SMG female 1 |

| Το γάλα είναι στο ψυγείο. | The milk is in the fridge. | Filler SMG male 2 and Filler SMG female 2 |

| Τι καλή γυναίκα που είναι η Μαρία. | Maria is such a nice woman. | Filler SMG male 2 and Filler SMG female 2 |

| Πήραμε ένα μεγάλο τραπέζι για την κοζίνα. | We bought a big table for the kitchen. | Filler SMG male 2 and Filler SMG female 2 |

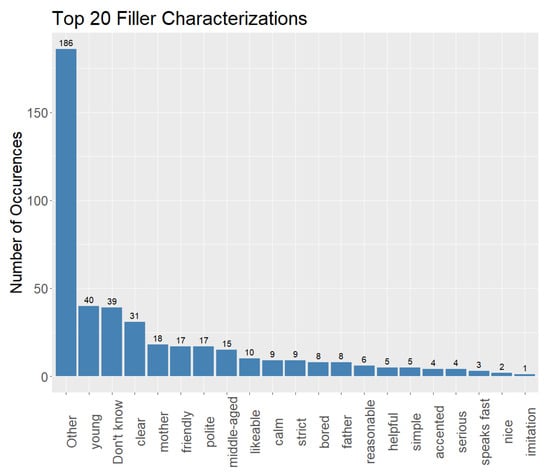

Appendix B. Top 20 Characterizations for SMG Filler Stimuli

Figure A1.

Twenty most common characterizations about filler speakers as offered by experiment participants. Arranged in descending order.

Notes

| 1 | ‘Non-native’ here is probably not meant to imply that the variety is acquired non-natively, but that the variety is not native to the place where it is found in. |

| 2 | The memes were collected between 2020 and 2021 from various Greek websites and social media platforms. The text is mostly written in a non-standard Greek script and in some cases in Greeklish (a transliteration of Greek into English orthohraphy, see Mouresioti and Terkourafi 2021). |

| 3 | The author, who is a second-generation Albanian migrant, can confirm that impressionistically (from her experience with other Albanians), the prominent meme features match to a large extent the actual L2 Greek of Albanian migrants. See also forthcoming work on the comparison of MAG with authentic Albanian L2 Greek. |

| 4 | 241 data points (i.e., characterizations do not appear in the graph as they occurred four or fewer than four times in the data. The graph includes the 20 most frequent characterizations). |

| 5 | Which, as the editors of this issue suggest, is not surprising given the age and educational background of the subjects. |

| 6 | That is not to say that the subjects necessarily figured out the purpose of the study. In a subsequent communication, a participant expressed their confidence that the experimenter’s research focuses on Cypriot Greek. |

| 7 | Admittedly, the SMG talkers are not attributed power traits either, although, the ‘clear’ characterizations are much more common for the SMG talkers (n = 31) than for the non-SMG talkers (n = 12). |

| 8 | At least those subjects that do make a specific identification and do not opt for the evasive ‘I don’t know’ or ‘foreigner’. |

| 9 | Who counts more than 150k followers, a considerable number for a Greek account. |

| 10 | As mentioned in Section 1, under different sociopolitical and historical contexts, ethnic minorities have emerged as bilingual in the ethnolect and the variety of the dominant language available to them. Take for instance Chicano English and local American English varieties acquired by Chicanx individuals in the U.S. as discussed by Fought (2002). |

| 11 | The author can attest to this from her own experience as a second-generation Albanian migrant in Greece. |

| 12 | ‘Unmotivated’ refers to substratal L1 (Albanian) features. These could still be part of the L2 Greek of other ethnic groups with different L1s. |

References

- Aarts, Jan, and Sylviane Granger. 2014. Tag sequences in learner corpora: A key to interlanguage grammar and discourse. In Learner English on Computer. Edited by Sylviane Granger. London: Routledge, pp. 132–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ampoulimen, Jackie, and Eirini Niamouaia Odoul. 2020. 9 Afrogreeks Discuss: What Does “I Can’t Breath” Mean in Greece? Onassis Cultural Center Roundtable Series. Available online: https://www.onassis.org/el/news/9-afrogreeks-discuss-what-does-i-cant-breathe-mean-in-greece (accessed on 15 February 2022).

- Androutsopoulos, Jannis. 2001. From the Streets to the Screens and Back again: On the Mediated Diffusion of Ethnological Patterns in Contemporary German. LAUD Linguistic Agency, Series A, Nr. 522. Duisburg: Universität Essen. [Google Scholar]

- Androutsopoulos, Jannis. 2010. Ideologizing ethnolectal German. In Language Ideologies and Media Discourse: Texts, Practices, Politics. Edited by Sally Johnson and Tommaso M. Milani. London and New York: Continuum International Publishing Group, pp. 182–204. [Google Scholar]

- Archakis, Argiris. 2020. The continuum of identities in immigrant students’ narratives in Greece. Narrative Inquiry 32: 393–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, Charles-James. 1973. Variation and Linguistic Theory. Arlington: Center for Applied Linguistics. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, Angelika, and Wolfgang Klein. 1984. Notes on the internal organization of a learner variety. In Interpretive Sociolinguistics: Migrants, Children, Migrant Children. Edited by Peter Auer and Aldo Di Luzio. Tübingen: G. Narr, pp. 215–29. [Google Scholar]

- Benor, Sarah Bunin. 2010. Ethnolinguistic repertoire: Shifting the analytic focus in language and ethnicity. Journal of Sociolinguistics 14: 159–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benor, Sarah Bunin. 2011. Mensch, bentsh, and balagan: Variation in the American Jewish linguistic repertoire. Language & Communication 31: 141–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benor, Sarah Bunin. 2016. Jews of color: Performing black jewishness through the creative use of two ethnolinguistic repertoires. In Raciolinguistics: How Language Shapes our Ideas about Race. Edited by John R. Rickford. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 171–84. [Google Scholar]

- Bills, Garland. 1976. Vernacular Chicano English: Dialect or interference? Southwest Journal of Linguistics 2: 30–36. [Google Scholar]

- Bucholtz, Mary, Nancy Bermudez, Victor Fung, Lisa Edwards, and Rosalva Vargas. 2007. Hella Nor Cal or totally So Cal? The perceptual dialectology of California. Journal of English Linguistics 35: 325–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdin, Rachel Steindel. 2021. Hebrew, Yiddish and the creation of contesting Jewish places in Kazimierz. Journal of Sociolinguistics 25: 81–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callies, Marcus. 2008. Easy to understand but difficult to use? Raising constructions and information packaging in the advanced learner variety. In Linking up Contrastive and Learner Corpus Research. Edited by Gaëtanelle Gilquin, Szilvia Papp and María Belén Díez-Bedmar. Leiden: Brill, pp. 201–26. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell-Kibler, Kathryn. 2007. Accent, (ING), and the social logic of listener perceptions. American Speech 82: 32–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell-Kibler, Kathryn. 2020. Deliberative control in audiovisual sociolinguistic perception. Journal of Sociolinguistics 25: 253–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzidaki, Aspasia, and Ioanna Xenikaki. 2012. Language Choice among Albanian Immigrant Adolescents in Greece: The Effect of the Interlocutor’s Generation. Menon 1: 4–16. [Google Scholar]

- Cheshire, Jenny, Jacomine Nortier, and David Adger. 2015. Emerging multiethnolects in Europe. Queen Mary’s OPAL 33: 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Chun, Elaine. 2009. Ideologies of legitimate mockery: Margaret Cho’s revoicings of Mock Asian. In Beyond Yellow English: Toward a Linguistic Anthropology of Asian Pacific America. Edited by Angela Reyes and Adrienne Lo. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 261–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clopper, Cynthia G., and David B. Pisoni. 2004. Homebodies and army brats: Some effects of early linguistic experience and residential history on dialect categorization. Language Variation and Change 16: 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clyne, Michael. 2000. Lingua Franca and Ethnolects in Europe and Beyond. Sociolinguistica 14: 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clyne, Michael. 2001. Can the shift from immigrant languages be reversed in Australia? In Can Threatened Languages Be Saved? Edited by J. Fishman. Bristol: Blue Ridge Summit, pp. 364–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clyne, Michael, Edina Eisikovits, and Laura Tollfree. 2001. Ethnic varieties of Australian English. In English in Australia. Edited by D. Blair and P. Collins. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 223–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimroth, Christine. 2013. Leaner Varieties. In The Encyclopedia of Applied Linguistics. Edited by Carol A. Chapelle. Hoboken: Blackwell Publishing Ltd., pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckert, Penelope. 2008. Where do ethnolects stop? International Journal of Bilingualism 2: 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekberg, Lena. 2011. Joint attention and cooperation in the Swedish of adolescents in multilingual settings: The use of sån ‘such’ and såhär ‘like’. In Ethnic Styles of Speaking in European Metropolitan Areas. Edited by Friederike Kern and Margret Selting. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp. 217–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishman, Joshua. 1980. Language Maintenance. In Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups. Edited by Stephen Thernstrom, Ann Orlov and Oscar Handlin. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, pp. 629–38. [Google Scholar]

- Fought, Carmen. 2002. Chicano English in Context. London: Pelgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freywald, Ulrike, Katharina Mayr, Tiner Özҫelik, and Heike Wiese. 2011. Kiezdeutsch as a multiethnolect. In Ethnic Styles of Speaking in European Metropolitan Areas. Edited by Friederike Kern and Margret Selting. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp. 45–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnevsheva, Ksenia. 2020. The role of style in the ethnolect: Style-shifting in the use of ethnolectal features in first- and second-generation speakers. International Journal of Bilingualism 24: 861–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogonas, Nikos. 2009. Language shift in second generation Albanian immigrants in Greece. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 30: 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogonas, Nikos. 2010. Γιατί η νέα γενιά Aλβανών μεταναστών στην Ελλάδα χάνει τη γλώσσα της; [Why is the second generation of Albanian immigrants in Greece losing its language?]. Polydromo 3: 28–34. [Google Scholar]

- Gogonas, Nikos, and Domna Michail. 2015. Ethnolinguistic vitality, language use and social integration amongst Albanian immigrants in Greece. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 36: 198–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellenic Statistical Authority. 2014. 2011 Population and Housing Census. Available online: https://www.statistics.gr/en/statistics?p_p_id=documents_WAR_publicationsportlet_INSTANCE_qDQ8fBKKo4lN&p_p_lifecycle=2&p_p_state=normal&p_p_mode=view&p_p_cacheability=cacheLevelPage&p_p_col_id=column-2&p_p_col_count=4&p_p_col_pos=1&_documents_WAR_publicationsportlet_INSTANCE_qDQ8fBKKo4lN_javax.faces.resource=document&_documents_WAR_publicationsportlet_INSTANCE_qDQ8fBKKo4lN_ln=downloadResources&_documents_WAR_publicationsportlet_INSTANCE_qDQ8fBKKo4lN_documentID=310596&_documents_WAR_publicationsportlet_INSTANCE_qDQ8fBKKo4lN_locale=en (accessed on 15 February 2022).

- Hill, Jane. 1993. ‘Hasta la vista, baby’: Anglo Spanish in the American Southwest. Critique of Anthropology 13: 145–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, Jane. 1995. Junk Spanish, covert racism, and the (leaky) boundary between public and private spheres. Pragmatics 5: 197–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, Jane. 1998. Language, race, and white public space. American Anthropologist 100: 680–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinskens, Frans. 2011. Emerging Moroccan and Turkish varieties of Dutch: Ethnolects or ethnic styles? In Ethnic Styles of Speaking in European Metropolitan Areas. Edited by Friederike Kern and Margret Selting. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp. 101–30. [Google Scholar]

- Kapllani, Gazmend, and Nicola Mai. 2005. Greece belongs to Greeks!: The case of the Greek flag in the hands of an Albanian student. In The New Albanian Migration. Edited by Russell King, Nicola Mai and Stephanie Schwanders-Sievers. Brighton: Sussex Academic Press, pp. 153–72. [Google Scholar]

- Kern, Friederike. 2011a. Introduction. In Ethnic Styles of Speaking in European Metropolitan Areas. Edited by F. Kern and M. Selting. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, Friederike. 2011b. Rhythm in Turkish German talk-in-interaction. In Ethnic Styles of Speaking in European Metropolitan Areas. Edited by Friederike Kern and Margret Selting. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp. 161–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, Friederike, and Margret Selting, eds. 2011. Ethnic Styles of Speaking in European Metropolitan Areas. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, Wolfgang, and Clive Perdue. 1997. The basic variety (or: Couldn’t natural languages be much simpler?). Second Language Research 13: 301–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotsinas, Ulla-Britt. 1988. Immigrant children’s Swedish—A new variety? Journal of Multilingual & Multicultural Development 9: 129–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, Wallace E., Richard C. Hodgson, Robert C. Gardner, and Samuel Fillenbaum. 1960. Evaluational reactions to spoken languages. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology 60: 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laporte, Samantha. 2012. Mind the gap! Bridge between World Englishes and Learner Englishes in the making. English Text Construction 5: 264–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazaridis, Gabriella, and Eugenia Wickens. 1999. “Us” and the “others”: Ethnic minorities in Greece. Annals of Tourism Research 26: 632–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehtonen, Heini. 2011. Developing multiethnic youth language in Helsinki. In Ethnic Styles of Speaking in European Metropolitan Areas. Edited by Friederike Kern and Margret Selting. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp. 291–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, Lian Malai. 2011. Late modern youth style in interaction. In Ethnic Styles of Speaking in European Metropolitan Areas. Edited by Friederike Kern and Margret Selting. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp. 265–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maligkoudi, Christina. 2010. H Γλωσσική Εκπαίδευση των Aλβανών Μαθητών στην Ελλάδα: Κυβερνητικές Πολιτικές και Oικογενειακές Στρατηγικές [The Language Education of Albanian Pupils: Educational Policies and Family Strategies]. Unpublished. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Crete, Rethymno, Greece. [Google Scholar]

- Manolessou, Io, and Nikolaos Pantelidis. 2013. Velar fronting in Modern Greek dialects. In Proceedings of the fifth International Conference on Modern Greek Dialects and Linguistic Theory. Edited by Mark Janse, Angela Ralli, Brian Joseph and Metin Bagriacik. Patras: University of Patras, pp. 272–86. [Google Scholar]

- Mesthrie, Rajend. 2006. Anti-deletions in an L2 grammar: A study of Black South African English mesolect. English World-Wide 2: 111–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcalf, Allan. 1974. The study of California Chicano English. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 2: 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouresioti, Evgenia, and Marina Terkourafi. 2021. Καλημέρα, kalimera or kalhmera? A mixed methods study of Greek native speakers’ attitudes to using the Greek and Roman scripts in emails and SMS. Journal of Greek Linguistics 21: 224–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndoci, Rexhina. 2021a. Albanians in Greece and the social meaning of ethnolectal features in L2 Greek. Proceedings of the Linguistic Society of America 6: 906–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndoci, Rexhina. 2021b. Social Perceptions of Albanian Greek. Unpublished Qualifying Paper. Columbus, OH, USA: The Ohio State University. [Google Scholar]

- Ndoci, Rexhina. forthcoming. The Linguistic Construction of Migrant Ethnic Identity: Names, Name-calling, and Internet Memes at the Service of (De)racialization. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA.

- Ndoci, Rexhina, Linda Xheza, Ilira Aliaj, Eno Agolli, Ervin Kondakҫiu, and Neritan Zinxhiria. 2021. Thirty Years Later—Rethinking Albanian-Greek Identity. Greek Studies Now: A Cultural Analysis Network Roundtable Series. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Bo-_R_k3d8I&list=PLV3c_i7JATs5hsYZAeQEvEdczEeOYPOdy&index=3&t=1662s&ab_channel=TORCH%7CTheOxfordResearchCentreintheHumanities (accessed on 15 February 2022).

- Ntelifilippidi, Alexandra. 2014. Social Networks and Attitudes towards Albanians in Greece: Intergroup Contact and Prejudice. Unpublished Master’s thesis, University of Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Papathanasiou, Th, and M. Reppas (Creators). 2021. In-Laws from Tirana [TV Series]. Miami: Mega TV. [Google Scholar]

- Pittaras, M. 2020. Parousiaste [TV Series]. Athens: J. K. Productions. [Google Scholar]

- Pontiki, Maria, Maria Gavriilidou, Dimitris Gkoumas, and Stelios Piperidis. 2020. Verbal aggression as an indicator of xenophobic attitudes in Greek Twitter during and after the financial crisis. Ppaper presented at the LR4SSHOC: Workshop about Language Resources for the SSH Cloud, Marseille, France, May 11–16; pp. 19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Psimmenos, Iordanis. 2001. Νέα εργασία και ανεπίσημοι μετανάστες στην μετροπολιτική Aθήνα [New labor and undocumented immigrants in the metropolitan Athens]. In Μετανάστες στην Ελλάδα [Immigrants in Greece]. Athens: Ellinika Grammata, pp. 95–126. [Google Scholar]

- Rampton, Ben. 1995. Crossing. Language and Ethnicity Among Adolescents. London: Longman. [Google Scholar]

- Rosa, Jonathan. 2016. From Mock Spanish to Inverted Spanglish: Language ideologies and the racialization of Mexican and Puerto Rican youth in the United States. In Raciolinguistics: How Language Shapes Our Ideas about Race. Edited by H. Samy Alim, John R. Rickford and Arnetha F. Ball. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 65–80. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen, Anna. 2016. The fate of linguistic innovations: Jersey English and French learner English compared. International Journal of Learner Corpus Research 2: 302–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selinker, Larry. 1972. Interlanguage. International Review of Applied Linguistics 10: 209–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selting, Margret. 2011. Prosody and unit-construction in an ethnic style: The case of Turkish German and its use and function in conversation. In Ethnic Styles of Speaking in European Metropolitan Areas. Edited by Friederike Kern and Margret Selting. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp. 131–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, Devyani. 2017. Scalar effects of social networks on language variation. Language Variation and Change 29: 393–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, Devyani, and Ben Rampton. 2015. Lectal focusing in interaction: A new methodology for the study of style variation. Journal of English Linguistics 43: 3–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverstein, Michael. 2003. Indexical order and the dialectics of sociolinguistic life. Language and Communication 23: 193–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şimşek, Yazgül. 2011. Constructions with Turkish şey and its German equivalent dings in Turkish-German conversations: Şey and dings in Turkish-German. In Ethnic Styles of Speaking in European Metropolitan Areas. Edited by Friederike Kern and Margret Selting. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp. 191–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, Gillian. 1992. The social and demographic context of language use in the United States. American Sociological Review 57: 171–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trudgill, Peter. 2003a. A Glossary of Sociolinguistics. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Trudgill, Peter. 2003b. Modern Greek dialects: A preliminary classification. Journal of Greek Linguistics 4: 45–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulbrich, Christiane, and Mikhail Ordin. 2014. Can L2-English influence L1-German? The case of post-vocalic /r/. Journal of Phonetics 45: 26–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Coetsem, Frans. 1988. Loan Phonology and the Two Transfer Types in Language Contact. Providence: Foris Publications. [Google Scholar]

- van Meel, Linda, Frans Hinskens, and Roeland van Hout. 2014. Variation in the realization of /εi/ by Dutch youngsters: From local urban dialects to emerging ethnolects? Dialectologia et Geolinguistica 22: 46–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Meel, Linda, Frans Hinskens, and Roeland van Hout. 2015. Co-variation and varieties in Modern Dutch ethnolects. Lingua 172: 72–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vraciu, Alexandra. 2013. Exploring the upper limits of the Aspect Hypothesis: Tense-aspect morphology in the advanced English L2 variety. Language, Interaction and Acquisition 4: 256–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, Abby, Christina García, Yomi Cortés, and Kathryn Campbell-Kibler. 2014. Comparing social meanings across listener and speaker groups. The indexical field of Spanish /s/. Language Variation and Change 26: 169–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).