Abstract

The aim of this study was to longitudinally examine mean length of utterance in words (MLU-w) and number of different words (NDW) and their association in children speaking Cypriot Greek (CG), a dialect for which such measures of language development have not been adequately investigated. Language samples from 36 typically developing monolingual CG-speaking children were collected at 4-month intervals from the age of 3;0 until 4;0 through free-play based conversation between the children and their caregivers. A zero-order correlation analysis among MLU-w, NDW, and age showed strong positive correlations between any two of these measures. A first-order analysis controlling for age showed that the correlation between MLU-w and NDW was independent from the influence of age. The study provides valuable information on the correlation between MLU-w and NDW for CG-speaking children and it contributes to our knowledge about language development in a dialectal variety lacking standardised tests.

1. Introduction

The use of measures of naturalistic language has been a recommended clinical practice in describing the language skills of children for at least half a century (Brown 1973; Gallagher 1983; Parker and Brorson 2005; Heilmann 2010; Eisenberg 2020; Klatte et al. 2022). Such measures offer alternative approaches to formal standardised and criterion-referenced tests, for describing and analysing language and communication in a variety of naturalistic contexts and with numerous conversational partners (i.e., clinicians, examiners, parents etc., who interact with the child in collecting a language sample) (Thomas-Tate et al. 2006; Guiberson 2020). Furthermore, measures of naturalistic language legitimise the ordinary talk of dialect-speaking children as a clinical resource (Stockman 1996; Heilmann and Westerveld 2013). They are considered an alternative language assessment procedure that brings cultural sensitivity, validity, accessibility, and flexibility to the screening process (Hewitt et al. 2005; Horton-Ikard et al. 2005; Boerma et al. 2016).

Since, for obtaining such measures, naturalistic language is elicited in a variety of contexts, e.g., conversation, free play, narration, expository discourse (Voniati et al. 2021), these measures also minimise the cultural and linguistic biases inherent in standardised testing situations (i.e., the inappropriateness for use of such tests in populations other than those for which they were standardised) (Gutiérrez-Clellen 1999; Leonard and Weiss 1983; Roseberry-McKibbin 2007). A variety of measures that examine linguistic growth and development can be extracted from naturalistic language sample analysis (LSA) (Horton-Ikard 2010). Utterance length and lexical diversity are the two most studied quantitative measures generated from LSA in researching and clinically examining child language development (Silverman and Ratner 2002; Thordardottir 2005). LSA is a time-honoured practice in the assessment of monolingual language acquisition, but also in cross-linguistic assessment (Oh et al. 2020). The ability to combine words and produce new semantic relations is generally one of the accomplishments of typically developing pre-school children (Silverman and Ratner 2002). When children begin to produce word combinations, they create new meanings that are not present in the semantic content of the words alone (Klee et al. 2007). The development in children of the ability to communicate with language can be broken down to the development of three interrelated components: content, form, and use (Bloom and Lahey 1978): when form and content are used together, they can make language understandable and communicative.

One of the most commonly mentioned indices of expressive language development used beyond the stage of single words is mean length of utterance (MLU), proposed by Brown (1973), who defined it as the average number of morphemes per utterance. MLU is calculated in a language sample of 100 spontaneous utterances by counting the total number of morphemes in the sample and dividing it by the total number of utterances (Brown 1973). Calculating MLU in morphemes for languages other than English was proven to be a challenge in the case of agglutinating languages such as Finnish (Bowerman 1973) and highly inflected languages such as Swedish (Hansonn and Nettelbladt 1995), Irish (Hickey 1991), Italian (Leonard 1998) and Spanish (Linares 1983); in such languages with rich morphology, MLU measured in words (MLU-w) was considered more appropriate than MLU measured in morphemes (MLU-m). Even in English, MLU-w was shown by Parker and Brorson (2005) to be a valid and reliable measure of gross language development, as it almost perfectly correlated with MLU-m.

Both MLU-w and MLU-m have been proposed in the literature as valid ways to benchmark the level of pre-school children’s language development in relation to age expectations. Data from Wells (1986) reported a linear and predictable rate of growth for the MLU-w of English-speaking children aged 1;3 to 5;0 (years;months). A study in Malaysia found that MLU-w increases with age in 130 children acquiring Mandarin Chinese aged 1;0–6;11 (Kok 2011). The findings of Kazemi Najafabadi et al. (2011) from a cross-sectional study on 171 typically developing children between 2;6 and 5;6 from Isfahan, Iran, revealed that the increase in MLU-m with age was statistically significant. Analysis by Acarlar (2005) indicated that MLU-m and number of different words in a cross-sectional study of 140 Turkish-speaking children strongly correlated with age in the age span of 3 to 6 years. While a number of studies demonstrate that MLU is a developmental index that changes predictably with age in some populations and languages in pre-school children, not all researchers agreed on the significance of the correlation between MLU and age for children older than 3;6 (Scarborough 1990; Conant 1987; Klee and Fitzgerald 1985).

As already mentioned, the ability to combine words and produce lengthier utterances is only one aspect of language growth; the ability to produce meaningful utterances should also be investigated in order to better understand language development (Miller 1991). Historically, the index used to measure lexical diversity in both child and adult language corpora has been the Type Token Ratio (TTR). This index of vocabulary variation is defined as the total number of unique words (types) divided by the total number of words (tokens) of a language (Miller 1981). It is one of the few LSA measures calculated by speech–language pathologists (SLPs) in everyday practice (Yang et al. 2022). TTR, however, has been shown in a number of analyses to be extremely sensitive to differences in sample size, as larger samples tend to yield lower TTR values (Malvern and Richards 1997). Furthermore, the validity of TTR as an indicator of language proficiency has been challenged, because it sometimes fails to discriminate between groups of children which are evidently different in age or diagnostic category (e.g., typically developing versus with language impairments) (Klee 1992).

Miller (1981) suggested that the number of different words (NDW), i.e., the total of every new word in a language sample of fixed length, may have properties better suited for investigating semantic development than TTR. Thus, NDW has become the most popular measure of lexical diversity and it shows promise as a way to measure lexical development both in pre-school years and beyond (Owen and Leonard 2001; Silverman and Ratner 2002). A low NDW describes limited lexical diversity, while a higher value denotes a language sample composed of a high number of different words (Silverman and Ratner 2002). Moreover, the NDW may inform SLPs of a child’s vocabulary use and whether the child uses words appropriately in real communicative encounters (Le Normand et al. 2008).

The natural setting (play context) can be used to obtain a language sample for measuring MLU and NDW without requiring that children remain still and look at pictures. In this way, children are likely to be more relaxed and spontaneous in their responses as language sample collections are conducted in a less formal way than many tests (Miller 1991). MLU and NDW as diagnostic tools are easy to understand and closely related to real-life settings (Condouris et al. 2003).

Measures of utterance length and measures of lexical diversity were found to correlate in the literature. Klee et al. (2004) found a moderate positive correlation between MLU-m and lexical diversity D (a measure based on TTR) in language samples from Cantonese-speaking children with typical language abilities aged 2;3 to 5;8; however, when the effect of age was removed, the correlation between the two measures was found not to be significant. The study of Malvern et al. (2004) that focused on British English language data, found MLUS (Mean Length of Structured Utterances, an alternative to MLU developed by Wells 1975) to be strongly correlated with lexical diversity D for the 1;6 to 3;6 age range. This finding also held for each of the nine stages within this range, with the exception of 1;6, for which there was no significant correlation between the two measures. The study also included a tenth stage at 5;0, which was computed with MLU-m; at that stage, the correlation between MLU-m and D was not significant. Miller’s (1991) study, where 192 typically developing English-speaking children between the ages of 2;8 and 13;3 were investigated, indicated that NDW correlated significantly with age and it contributed significantly to the comparison of MLU-m with chronological age. Potratz et al. (2022) collected language samples from 32 children speaking American English aged 5;0–8;11 using storytelling and question–answers. They measured MLU-m and MLU-w (among other measures of grammatical development) and NDW (among other measures of lexical development). Their findings showed a strong correlation between NDW and MLU; however, NDW did not correlate with either MLU-m or MLU-w when their shared variance with other measures of syntactic ability was controlled for. Dethorne et al. (2005) investigated how measures such as NDW can predict MLU-m scores for 44 typically developing English-speaking pre-school participants aged 2;4–3;1, who had an average MLU-m typical of their age; their results showed that NDW was a significant predictor for MLU-m, as it accounted much of MLU-m variance and had a strong positive correlation with it. The positive correlation between MLU-m and NDW featured also in the study of Ukrainetz and Blomquist (2002) where participants were 28 typically-developing pre-school English-speaking children aged 3;11–6;0 years. Acarlar (2005) also found a strong positive correlation between MLU-m and NDW for a similar age range (3–6 years), but for a more morphologically rich language, namely Turkish. Santos et al. (2015) examined 94 children aged 4;0–5;5 who spoke European Portuguese and found a small-to-medium positive correlation between MLU-w and measures of lexical diversity resulting from the Test of Abstract Language Comprehension (TALC). Nóro and Mota (2019) examined the association between MLU (measured both in words and morphemes) and vocabulary size (calculated separately for content and function words) in a sample of 72 typically developing children speaking Brazilian Portuguese aged from 2;0 to 4;11:29 (years;months:days). Their findings showed that all four combinations of utterance length and vocabulary measures positively correlated across the age range studied.

The correlation between measures of morphosyntactic and semantic abilities has been investigated in the literature also in relation to the long-standing question of whether these two abilities are acquired by a single underlying mental mechanism (e.g., Bates and Goodman 2001) or whether morphosyntax resides in an autonomous cognitive module separate from the lexicon-learning mechanisms (e.g., Fodor 1983). The dual-mechanism view (e.g., Pinker 1991) postulates two autonomous mechanisms for the development of grammatical and lexical abilities, and thus assumes no correlation between developmental measures of those abilities. A single-mechanism view posits interdependence between morphosyntactic and semantic development, and thus assumes that measures of grammatical ability positively correlate with measures of lexical ability. Under the single-mechanism view, it has been claimed that the development of early lexical skills predicts the subsequent development of grammatical skills, a position known as lexical/semantic bootstrapping (e.g., Marchman and Bates 1994); according to this position, the knowledge of the meaning of words helps children deduce information about the words’ syntactic properties. Other studies have proposed that knowledge of syntax can facilitate acquisition of word and sentence semantics, a position known as syntactic bootstrapping (e.g., Gleitman and Gillette 1999). Other accounts proposed a bidirectional bootstrapping, in the sense of reciprocal relations between semantic and morphosyntactic development (Dionne et al. 2003). Moyle et al. (2007) examined the relationship between the two developmental abilities of 30 typically-developing and 30 late-talking English-speaking children whose ages ranged from 2;0 to 5;6. By using language sampling, parental reports, and formal tests, they extracted various measures of grammatical ability, among which were MLU3-m (i.e., the mean length in morphemes of the three longest utterances produced by the child as reported by their parents) for the 2;0–2;6 age range and MLU-m for the 2;6–5;6 range; they also extracted various measures of lexical abilities, among which was NDW for the 2;6–5;6 range. For each age point, they also computed a composite grammatical score based on all measures of grammatical ability; similarly, a composite lexical score was computed on the basis of the various measures of lexical development. An important aspect of their statistical analyses was the correlations between measures of grammatical development at a certain age point with measures of lexical development at a different age point. Their results for typically developing children showed lexical abilities at earlier age points correlated with grammatical abilities at later age points; moreover, it was also found that grammatical abilities at earlier age points correlated with lexical abilities at later age points. These results supported the bidirectional bootstrapping position under the single-mechanism view. However, these predictive associations between the two measures existed only until the age of 3;6, beyond which this interconnectedness appears to collapse. This was interpreted as emerging modularity, i.e., a transition to a dual-mechanism situation. This finding supports the view that language acquisition may start off as a single mechanism with interconnected abilities and bidirectional bootstrapping, but after a certain age grammar and lexicon learning are governed by different cognitive modules.

Apart from their value in providing an answer to long-standing debates in developmental psycholinguistics, MLU and NDW are also of clinical importance, as they have been shown to be useful for differentiating typical language from impaired language performance in pre-school children (Gavin and Giles 1996; Miller and Chapman 1981; Tse et al. 2002; Klee et al. 2004; Voniati 2016). They can be easily used with children with a range of speech, language and communication disorders including specific language impairment, developmental delay, autism spectrum disorder (ASD), literacy difficulties, but also with children that need support to initiate speech and manage to use functional language (Rice et al. 2006; Thordardottir and Namazi 2007; Tavakoli et al. 2015). From that point of view, databases regarding MLU and NDW can be important sources of developmental age data and notably aid professionals to conduct accurate and reliable language assessments.

Purpose of the Study

Worldwide, there has been an increase in the use of LSA procedures to track language development and diagnose language impairment in culturally and linguistically diverse populations (Horton-Ikard et al. 2005); although this increase would be especially beneficial in cases of non-standard language varieties, not much research has been conducted on this topic in the case of dialectal varieties. Moreover, research has concentrated primarily on English, something that could mean that any conclusions on the association between MLU and NDW are not generalisable to populations acquiring languages with richer inflectional morphology. It becomes apparent that research needs to turn to morphologically rich languages in order to reach more definite conclusions as to the universal association of MLU with NDW. Such an investigation can also contribute to the debate between the single- and dual-mechanism view regarding the development of grammatical and lexical skills.

For these reasons, the language variety selected in this study for investigation was a non-standard variety with rich morphology, namely Cypriot Greek (CG). CG is a variety of Modern Greek spoken on the island of Cyprus by approximately 800,000 people and also by substantial immigrant communities abroad. It is acquired as first language by Grecophone Cypriots and is used in everyday communication. Being sister varieties, CG and Standard Modern Greek (SMG) are proximal varieties with fundamental lexicogrammatical commonalities; at the same time though, they exhibit significant differences in terms of lexicon/semantics, phonetics, grammar (phonology, morphology, and syntax) and use (see e.g., Newton 1972; Terkourafi 2007). In terms of morphology, the two varieties differ to various degrees when it comes to compounding (e.g., CG [metɾofiˈlːo] vs. SMG [filomeˈtɾo] ‘I riffle’), derivation (e.g., CG [aˈɾ̥c+efk+o] vs. SMG [aɾˈç+iz+o] ‘I start’), and inflection. Concerning the latter, the two varieties are different in terms of verbal suffixes (e.g., CG [ˈɣɾaf+usin] vs. SMG [ˈɣɾaf+un] ‘they write’; CG [pliˈnː+isk+o] vs. SMG [ˈplen+o] ‘I wash’), the use of a circumfix for past tenses in CG comprised of an /e/ pre-stem part and the final post-stem part (e.g., CG [e+ˈɣɾaf+amen] vs. SMG [ˈɣɾaf+ame] ‘we were writing’), nominal suffixes (e.g., CG [ˈɣlosːa+n] vs. SMG [ˈɣlosa+∅] ‘tongue-accusative’) etc. Regarding the sociolinguistic situation in Cyprus, as CG is considered a dialectal variety, it has not undergone standardisation (i.e., the process involving selection of a norm, codification of its form, extension of its functions to prestigious domains, and its acceptance by the community; Haugen 1966), and thus has no official status; the Greek variety that serves as the official language of the Republic of Cyprus is SMG, with which CG stands in a diglossic relationship. Because of the acquisition of both ‘lects’, i.e., the standard and the non-standard variety, CG speakers can be described as discrete bilectals (Rowe and Grohmann 2013) in the sense that they first acquire the dialect at home and then the standard mainly through formal education. Through schooling, CG speakers become literate in SMG and not CG, due to the abovementioned lack of standardisation of CG: there is no single form of CG which has been selected to serve as the norm (as there is observable regional, social, and functional variation; cf. Tsiplakou et al. 2016) and to have its grammar, lexicon, and writing system codified (Armostis et al. 2014) through published grammars, dictionaries, and style guides. Not only is there a lack of such prescriptive work, there is also great room for more descriptive work on the dialect. Linguistic research has been increasingly turning its attention to describing CG over the last decades, but to date there are many lexicogrammatical aspects of the dialect that await linguistic investigation. From a clinical perspective, this lack of a well-defined norm variety of CG and the ensuing unavailability of language resources that would support clinical research result in a limited number of both language assessment tests (especially formal standardised and criterion-referenced tests) for CG-speaking children (Voniati et al. 2020) and of published studies on measures of language development (Voniati 2016).

In the literature on CG, there has not been any published research evidence regarding the correlation of MLU and NDW for pre-school CG-speaking children, two commonly used LSA measures. The only studies that examined the association between morphosyntactic and lexical skills in CG-speaking children were Taxitari et al. (2017) and Taxitari (2021); in both cases, the participants’ age ranged from 1;6 to 2;6 while measures resulted from parent-reported data on their child’s language abilities. The findings by Taxitari et al. (2017) showed a significant positive correlation between morphosyntactic and lexical skills measured as the total morphosyntactic score (a measure of grammatical complexity) and the total vocabulary score respectively. In Taxitari (2021), the total vocabulary score was found to be a significant regression predictor of MLU3-w (i.e., the mean length in words of the three longest utterances produced recently by the child). As both studies used parental feedback rather than direct child data, there is a need for validating this association by (a) using language sampling and LSA measures and (b) extending investigation to an age range not previously examined.

This study aimed to address this research gap by providing data on measures of utterance length and lexical diversity, MLU-w and NDW respectively, computed from naturalistic language samples of children with typical language development at ages 3;0, 3;4, 3;8, and 4;0. Apart from the overall correlation between MLU-w and NDW, this study also aimed to examine whether there is a correlation between these two measures at each of the four age stages under investigation. This investigation is of clinical importance, as it can serve as the basis for meeting the need for the development of language assessment tests for CG. Moreover, it can inform clinical practice in Cyprus regarding the investigation of both language skills: when SPLs assess and describe language development, it is important to consider these components as a together. Since these domains contribute to language in different ways and are necessary for everyday communication, it is important for SLPs to be familiar with their interrelation. There, SLPs need exposure to the role of these components play in language development and how they are related, in order to be able to provide better assessment and intervention support.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Participants for this longitudinal study were 36 CG-speaking children (18 girls, 18 boys) with typical course of language development coming from monolingual CG-speaking environments. Language samples were collected from each child from the age of 3;0 until 4;0 at 4-month intervals. While a number of studies (see above) demonstrate that, in some populations and languages in pre-school children, MLU is a developmental index that changes predictably with age, not all studies agree on the significance of the correlation between MLU and age for children older than 3;6 (Klee and Fitzgerald 1985; Conant 1987; Scarborough 1990). In the case of CG-speaking pre-schoolers, though, there are no reference databases on MLU scores, nor are there research findings about the relationship between age and MLU. Lacking such data, language samples in the present study were collected even beyond the age of 3;6.

At intake, parents were asked to complete child case history form, which is an extensive questionnaire on aspects such as family background, medical history, speech and language history, developmental history, etc. In addition to parent-reported information, children’s medical profile was also based on medical evaluation by paediatricians and otolaryngologists. On the basis of the child history information from the parental questionnaires and the medical evaluations, it was shown that all children presented unremarkable developmental and medical history.

The parents of the children participants had responded to the announcement sent by the first author to nursery schools and paediatricians in the areas of Nicosia. Parents and caregivers signed a written consent form prior to the study. The research protocol was approved by the Department of Speech and Language Therapy Ethics Committee–European University Cyprus.

2.2. Procedures

The first author and two trained research assistants collected the data at 4-month intervals during four experimental sessions when the children were 3;0, 3;4, 3;8, and 4;0. During the sessions, children interacted with the caregiver (there was a mix of fathers and mothers in attendance, depending on their availability to bring the child to the research facilities) while playing with various sets of toys (plastic food items, dolls, plastic cups and plates, plastic tractors and cars, puzzles, pictures, and wordless picture books). The toys remained constant across all children and across all sessions. During the sampling collection, the child was comfortably seated, and the recording device was positioned on a at surface no more than one metre from the parent and the child. Parents were reassured that the recording device would not be turned on without them being notified. Each session lasted approximately 30 minutes, was audio recorded using an Olympus DS-2500 digital voice recorder with a compact microphone configured for omnidirectional recording, under the control of the parent. For the transcription of the recorded language samples a pencil-and-paper method was used.

2.3. Computing MLU-w and NDW

In the current research, in order to compute MLU-w and NDW, certain criteria were followed in selecting which utterances would be analysed. More specifically, the first 50 utterances the production of which was fully linguistically processed by the children, and thus were most representative of their language performance, were included in the analysis; all identical utterances, imitations, elliptical responses to questions, counting and other sequences of enumeration were excluded, as their production was not fully linguistically processed. MLU-w was computed by totalling up the words in each of the 50 selected utterances and dividing the sum by the number 50 (Voniati 2016; Ezeizabarrena and Fernandez 2018). The shorter language samples have been shown to be reliable for certain measures of lexical diversity (NDW) and for MLU, yielding good-quality assessment information (Casby 2011; Wilder and Redmond 2022). However, traditional recommendations for LSA suggest the use of samples of 50 utterances or more to assess children’s development (Eisenberg et al. 2001). Calculating measures from a language sample consisting of a minimum of 50 to 100 continuous and intelligible utterances, is the suggested conventional clinical practice for professionals working with young children with or without language disorders (Eisenberg et al. 2001; Heilmann et al. 2010). The calculation of NDW requires totalling up every new word in a language sample of fixed length (Hewitt et al. 2005). Although function words are considered as having little lexical meaning, they express structural relationships with content words and help create meaning in sentences (Malvern et al. 2004). Therefore, for the purposes of this research, NDW was counted by totalling up every new word (be it function or content word) in the 50 selected utterances.

For the purposes of establishing reliability in the computation of the two measures, out of the 144 transcripts (36 children × 4 age stages), 16 transcripts (i.e., 11% of the sample) were randomly selected by the second author of the paper for computing MLU-w and NDW. The resulting computations were compared to the original computations made by the first author and Krippendorff’s alpha was calculated (Hayes and Krippendorff 2007). Inter-rater reliability scores were high for both MLU-w (Krippendorff’s α = 0.943, 95%CI [0.917, 0.967]) and NDW (Krippendorff’s α = 0.859, 95%CI [0.779, 0.923]).

2.4. Method of Statistical Analysis

As the design of the study was longitudinal, the relationship between MLU-w and NDW cannot be investigated with a simple Pearson correlation analysis on the whole dataset, as it assumes that each paired data point is independent and identically distributed, an assumption that is violated in a repeated-measures design. One way of not violating this independence assumption is by collapsing data across the four age stages and using just the average MLU-w and NDW value for each individual; however, this technique results in substantial power loss. An alternative technique would be a repeated-measures correlation analysis that would avoid power loss from collapsing data and would not improperly treat each observation as independent. This statistical technique allows for examining the intra-individual linear-association relationship between MLU-w and NDW across the four age stages and for determining their common association across individuals in terms of a repeated-measures Pearson correlation coefficient rrm. Such technique is conducted with the use of the “rmcorr” R package (Bakdash and Marusich 2017).

It is expected that both MLU-w and NDW will increase with age, thus their correlation with age was investigated with a one-tailed Spearman correlation analysis; this analysis was selected over Pearson correlation analysis, as the age variable was not found to be normally distributed (Shapiro–Wilk W(114) = 0.856, p < 0.0005). An observed zero-order (i.e., not controlling for confounding factors) correlation between MLU-w and NDW may merely reflect a joint relationship with age and not necessarily a true relationship between the two variables. In order for the direct relationship between MLU-w and NDW to be investigated, a partial first-order Pearson correlation analysis was performed controlling for the effect of age.

In addition, the correlation between MLU-w and NDW was investigated separately at each of the four age stages. In each of the four analyses, if the distributions of both variables were normally distributed, a Pearson correlation analysis was conducted; if not, then a Spearman correlation analysis was conducted.

Both the zero-order correlations and the correlations per age stage involved multiple comparisons, something that results in inflation of the family-wise error rate (FWER). In order to control for FWER, p-values were adjusted with the Šidák Step-Down procedure (Stevens et al. 2017).

3. Results

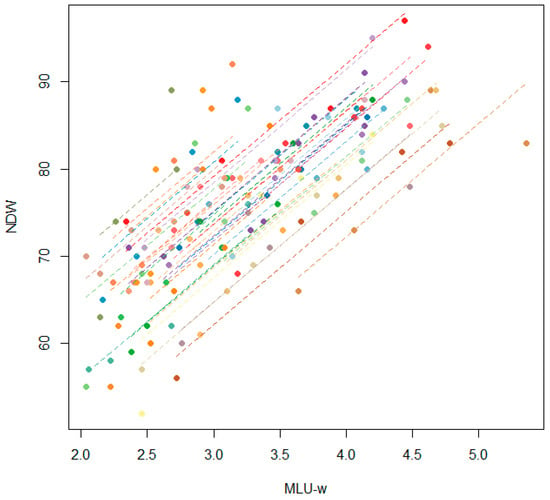

The repeated-measures correlation analysis showed a strong positive correlation between MLU-w and NDW, rrm(107) = 0.856, p < 0.0005, 95% CI [0.795, 0.899] (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Scatter plot illustrating repeated measures correlations between the MLU-w and NDW with different colour used for each child; parallel lines are fitted for each child.

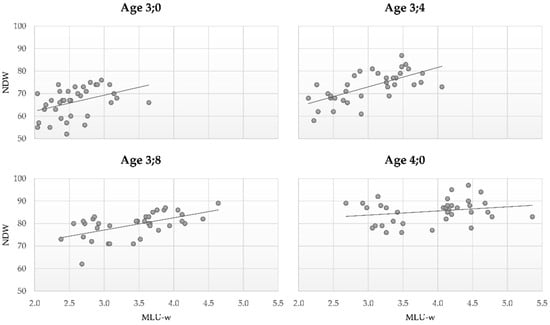

Zero-order correlation analyses of MLU-w and NDW with age revealed a strong positive correlation for both MLU-w, ρ(144) = 0.679, p < 0.0005, 95% CI [0.580, 0.758], and NDW, ρ(144) = 0.781, p < 0.0005, 95% CI [0.708, 0.838] (see Figure 2). A first-order correlation analysis between MLU-w and NDW controlling for age revealed again a strong positive correlation between the two measures, r(141) = 0.710, p < 0.0005, 95% CI [0.617, 0.783], something that indicates that the observed correlation between MLU-w and NDW is not due to their common correlation with age.

Figure 2.

Scatterplots for the correlation between MLU-w and NDW at each age point (each presented in a different panel).

The results of the correlation analyses between MLU-w and NDW per age stage are reported in Table 1. Their positive correlation was verified for the first three age stages and especially for 3;4 and 3;8, for which the correlation was stronger. At 4;0, the correlation was weak and was shown to be statistically non-significant (see Figure 2).

Table 1.

Results of correlation analyses between MLU-w and NDW at each age point.

4. Discussion

The study’s main research question was whether there is a correlation between MLU-w and NDW in typically developing CG-speaking children aged 3;0, 3;4, 3;8, and 4;0; the results of the study showed that there is a significant positive correlation between MLU-w and NDW irrespective of the individual association of age with each of the two measures. This overall across-ages correlation was verified with within-ages correlations for the first three age points, especially for 3;4 and 3;8, at which the correlation was stronger. At 4;0 the correlation was weak and was shown to be statistically non-significant.

Regarding the across-ages association between measures of grammatical and lexical development, the findings of the present study complements those of studies investigating children of other age ranges. In particular, the association between the two developmental skills found for CyGr-speaking children for the 1;6–2;6 age range by Taxitari et al. (2017) and Taxitari (2021) was shown by the present study to also exist for children in the 3;0–4;0 range (even though those studies used parent-reported data and different indices from the present study). This study only marginally overlaps in age range with Dethorne et al. (2005), who found a positive correlation between MLU-m and NDW for English-speaking children aged 2;4–3;1. Studies that have a greater age overlap with the present study also found an across-ages association. In particular, Malvern et al. (2004) found a positive correlation between MLUS and lexical diversity D in their 1;6–3;6 sub-range (for which such correlation could be run) for children speaking British English. Investigating the 3;11–6;0 age range in English-speaking children, Ukrainetz and Blomquist (2002) also found an association between the two skills (measured as MLU-m and NDW). Regarding languages other than English, Klee et al. (2004) found a positive correlation between MLU-m and lexical diversity D for Cantonese-speaking children aged 2;3–5;8. However, contrary to the present study, when they controlled for the effect of age, the correlation between the two measures ceased to be significant; this can be taken to mean that the grammatical abilities of the children examined are independent of their lexical abilities, as any correlation observed between them is wholly due to their common association with age. As for morphologically richer languages, Acarlar (2005) found a strong positive correlation between MLU-m and NDW for Turkish-speaking children of the 3;0–6;0 age range. Nóro and Mota (2019) also found significant positive correlations between utterance length (MLU-m and MLU-w) and vocabulary size (distinguishing between vocabulary in content and function words) for Brazilian-Portuguese –speaking children ranging in age from 2;0 to almost 5;0. A similar result was found also for European Portuguese by Santos et al. (2015), who investigated the association between MLU-w and TALC in children aged 4;0–5;5; even though their age range only marginally coincides with the one in the present study, it is indicative that the across-ages positive correlation observed in this study is also true for somewhat older children. In the same vein, the results of Potratz et al. (2022) in older children (aged 5;0–8;11) speaking American English, showed that both MLU-w and MLU-m positively correlated with NDW. However, contrary to the present study, NDW did not correlate with either MLU-m or MLU-w when their shared variance with other measures of syntactic ability was controlled for.

Regarding the within-ages correlations, an interesting finding of the present study was that, even though there was a significant within-age correlation between MLU-w and NDW for the first three age points, the correlation for age 4;0 was not significant. In the literature reviewed, only a couple of studies investigate correlations within different age points. Malvern et al. (2004) found that MLUS and D positively correlated for each of the age points examined within the 1;9–3;6 range, something that is in agreement with our finding regarding the within-ages correlations for ages 3;0 and 3;4. Their study did not include any age points between 3;6 and 5;0, hence no direct comparisons with the 3;8 or 4;0 age points of the current study can be made. However, for age 5;0, they found no correlation between D and MLU-m, which may indicate that after a certain age point (arguably around 4;0), the within-age association between the two skills breaks down despite of any significant association at an across-ages level (observed both in Malvern et al. 2004 and in the present study). This apparent discrepancy between the across-ages strong correlation and the lack thereof within the last age point in both studies may be mathematically explained by the fact that the across-ages correlation is calculated from a bigger pool of data, in which earlier age points are compensating for the lack of association of the last age point. Moyle et al. (2007) found somewhat different results in their subset of typically developing children: there was a strong positive correlation between MLU-m and NDW at age 4;6 (and between MLU3-m and parent-reported vocabulary size at age 2;0), but not for any other age point (2;6, 3;6, and 5;6). When they used composite scores of grammatical and lexical measures, the reverse was observed: there were strong associations between the two abilities, with the exception of age 4;6, for which the correlation was not significant. A comparison with the results of the present study is hard to make, as only their 3;6 age point falls within the age range examined here. There is no point in their age range before which the two abilities correlate and after which they do not (contrary to the assumption we made above in comparing the present findings with the findings of Malvern et al. 2004). Nevertheless, Moyle et al. (2007) also investigated cross-lagged associations, i.e., correlations of the one ability at a certain age point with the other ability at a different age point. This investigation revealed that earlier grammatical skills predicted later lexical skills and earlier lexical skills predicted later grammatical skills up until the age of 3;6, beyond which no significant cross-lagged correlations were found. This finding was interpreted as a separation (i.e., emerging modularity) of the two skills after this age: before 3;6, the two skills are interdependent, but after this age they become autonomous and develop separately. In the present study, this turning point may be later, i.e., after 3;8 and before (or at) 4;0. However, this hypothesis should be empirically tested in a future study. Nóro and Mota (2019) also examined within-ages correlations for three age groups, namely, children in their 2nd, 3rd, or 4th year of age. Their findings showed that both MLU-m and MLU-w correlated with the two vocabulary measures for the 2-year-olds, with the exception of MLU-w and Closed Class vocabulary, i.e., function words, arguably because children do not use many function words during this age. For 3-year-olds, no correlation was observed between MLU and vocabulary, something that was ascribed to the emergence of phrasal structures, which require more functional words. This finding does not corroborate the correlations observed in the present study for ages 3;0, 3;4, and 3;8. For 4-year-olds, Nóro and Mota (2019) found no correlations of MLU with vocabulary, with the exception of MLU-w and Open Class vocabulary, i.e., content words, for which there was a moderate positive correlation. This finding means that, for this age, the more content word a child has in their vocabulary, the longer their utterances are in words; moreover, the lack of correlation between MLU-w and Closed Class vocabulary for this age shows that an increase in function words in a child’s vocabulary does not correspond to more words in a sentence. In discussing this finding, Nóro and Mota (2019) explained it on the assumption that a great increase of function words took place during the 4th year, which resulted in more complex and well-developed syntactic structures rather than to longer utterances. This could be an explanation of the lack of correlation between lexical and grammatical skills in the present study as well: while the vocabulary may be increasing in content words at age 4;0 in parallel with an increase in MLU-w, an abrupt increase in function words in the vocabulary may not be associated with longer utterances (thus eliminating the overall correlation between NDW and MLU-w or masking any true correlation between content words and MLU-w). Some studies posit that this dissociation between lexical diversity measures and MLU, be it measured in morphemes or words, may take place even later during the 5th year, during which MLU may reach a plateau or even slightly decline (see Santos et al. 2015, and references therein). In the present study, we assume that this dissociation happens at age 4;0, if not for all children, at least for enough to render the correlation non-significant.

Regarding the single- vs. dual-mechanism debate, the strong across-ages correlation between MLU-w and NDW found in the present study may serve as indication for a single-mechanism in the acquisition of lexical and grammatical skills. The significant within-ages correlations verified this view for ages 3;0 to 3;8, but not for age 4;0. It is assumed here that this break-down of the association between the two measures may be an indication of emerging modularity, which arguably takes place later compared to Moyle et al. (2007). However, this assumption should be tested with a more expanded age range, in order to examine whether the lack of association persists in later age points.

It should be noted that, in comparing the findings of the present study to other studies, it is not always easy draw parallels, as different studies used different methodology regarding the king of measures used, the statistical analysis performed, the characteristics of the sample regarding size, age range, and language, the method of collecting data etc. All these factors make it difficult to ascertain whether the development of vocabulary and utterance length proceed in a uniform fashion across languages. In addition to the above, many other factors contribute to the variability that can be observed in the language development process cross-linguistically (Hickey 1991; Wong et al. 2010): since language represents a multidimensional construct, developmental patterns may be influenced by genetic factors, gender, the children’s cognitive development, their linguistic capacity, and socioeconomic status and general language input in the children’s environment (Becker and Deen 2020; Rice et al. 2010; Saxton 2017).

In the context of child development research, there is a need to extend investigations on MLU and NDW correlation beyond the pre-school time frame, to collect language sample in different settings, and to analyse different dimensions of language development. The outcomes of the current research point toward both similarities and differences in the ways in which MLU-w and NDW grow and correlate over time in typically developing CG-speaking children. Overall, the results regarding the correlation of MLU-w and NDW need to be interpreted with caution; further research with larger numbers of participants would help indicate whether the current findings are generalisable. Finally, additional studies are needed to specify the correlation of MLU-w and NDW in typically developing CG-speaking children and in children whose language does not appear to be developing typically.

5. Conclusions

To date, no other research exists that examines the correlation of utterance length and lexical diversity measures in CG-speaking children in the age range studied. The language assessment of children who use a dialect needs to be based on the standards of typical language behaviour of their own language variety. Conclusions drawn from standardised tests may differ from the actual language performance of a dialect-speaking child, since these tests, in the case of CG, are based on the standard language and not on the dialect. Although the data from the present study may not be exhaustive and generalisable to a wider national context, the results are important since they provide, for the first time, valuable information on the correlation between MLU-w and NDW for CG-speaking children. Therefore, the study provides background knowledge and general language development trends of CG, generated from LSA. This could contribute to SLPs’ better understanding about the relations of language components, which would lead to improvements in their everyday practice and, consequently, better outcomes for children. Findings and information such as those presented here may assist SLPs in developing more efficient practices.

The current study provides also informative material to those who work with measures of naturalistic language. It has gone some way towards enhancing our understanding of the correlation of utterance length and lexical diversity measures for dialect-speaking children. Correlations between MLU-w and measures of lexical diversity, such as NDW, suggest that data generated by MLU-w, although designed to assess syntax, may instead measure language development more extensively. Furthermore, the present study contributes to the increasing number of reference databases for documenting language performance in dialect speakers, providing at the same time a model for establishing local reference databases for dialect speakers.

This study can serve also as a basis for future studies on LSA in establishing a statistical link between the MLU-w and the NDW in other populations and age ranges. This set of findings argues for the importance of expanding the sample population database and increasing the regional linguistic diversity of the child participants. Future research will be helpful in providing more clarity in the patterns found here and will help clinicians address the challenge of accurately describing dialect-speaking children’s language performance with measures of naturalistic language.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.V., S.A. and D.T.; methodology, L.V. and S.A.; formal analysis, S.A.; visualization, S.A.; investigation, L.V.; writing—original draft preparation, L.V., S.A. and D.T.; writing—review and editing, L.V., S.A. and D.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Department of Speech and Language Therapy Ethics Committee–European University Cyprus.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Acarlar, Funda. 2005. Türkçe ediniminde gelişimsel özelliklerin dil örneği ölçümleri açısından incelenmesi [Developmental Characteristics of Language Sample Measures in the Acquisition of Turkish]. Türk Psikoloji Dergisi [Turkish Journal of Psychology] 20: 61–76. Available online: https://www.psikolog.org.tr/tr/yayinlar/dergiler/1031828/tpd1300443320050000m000166.pdf (accessed on 19 December 2022).

- Armostis, Spyros, Kyriaki Christodoulou, Marianne Katsoyannou, and Charalambos Themistocleous. 2014. Addressing writing system issues in dialectal lexicography: The case of Cypriot Greek. In Dialogue on Dialect Standardization. Edited by Carrie Dyck, Tania Granadillo, Keren Rice and Jorge Emilio Rosés Labrada. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, pp. 23–38. [Google Scholar]

- Bakdash, Jonathan Z., and Laura R. Marusich. 2017. Repeated Measures Correlation. Frontiers in Psychology 8: 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bates, Elizabeth, and Judith C. Goodman. 2001. On the inseparability of grammar and the lexicon: Evidence from acquisition. In Language Development: The Essential Readings. Edited by Mike Tomasello and Elizabeth Bates. Malden: Blackwell, pp. 134–62. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, Misha, and Kamil Ud Deen. 2020. Language Acquisition and Development: A Generative Introduction, 1st ed. Cambridge: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom, Lois, and Margaret Lahey. 1978. Language Development and Language Disorders. New York: John Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Boerma, Tessel, Paul Leseman, Mona Timmermeister, Frank Wijnen, and Elma Blom. 2016. Narrative abilities of monolingual and bilingual children with and without language impairment: Implications for clinical practice. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders 51: 626–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowerman, Melissa. 1973. Early Syntactic Development. A Cross-Linguistic Study with Special Reference to Finnish. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Roger. 1973. A First Language: The Early Stages. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Casby, Michael W. 2011. An examination of the relationship of sample size and mean length of utterance for children with developmental language impairment. Child Language Teaching and Therapy 27: 286–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conant, Susan. 1987. The relationship between age and MLU in young children: A second look at Klee and Fitzgerald’s data. Journal of Child Language 14: 169–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Condouris, Karen, Echo Meyer, and Helen Tager-Flusberg. 2003. The relationship between standardized measures of language and measures of spontaneous speech in children with autism. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology 12: 349–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dethorne, Laura S., Bonnie W. Johnson, and Jane W. Loeb. 2005. A closer look at MLU: What does it really measure? Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics 19: 635–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dionne, Ginette, Philip S. Dale, Michel Boivin, and Robert Plomin. 2003. Genetic evidence for bidirectional effects of early lexical and grammatical development. Child Development 74: 394–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, Sarita L. 2020. Using General Language Performance Measures to Assess Grammar Learning. Topics in Language Disorders 40: 135–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, Sarita L., Tara McGovern Fersko, and Cheryl Lundgren. 2001. The use of MLU for identifying language impairment in pre-school children: A review. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology 10: 323–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezeizabarrena, Maria-José, and Iñaki Garcia Fernandez. 2018. Length of Utterance, in Morphemes or in Words?: MLU3-w, a Reliable Measure of Language Development in Early Basque. Frontiers in Psychology 8: 2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fodor, Jerry A. 1983. Modularity of Mind: An Essay on Faculty Psychology. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher, Tanya M. 1983. Pre-assessment: A procedure for accommodating language use variability. In Pragmatic Assessment and Intervention Issues in Language. Edited by Tanya M. Gallagher and Carol A. Prutting. San Diego: College-Hill Press, pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Gavin, William J., and Lisa Giles. 1996. Temporal reliability of language sample measures. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research 39: 1258–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gleitman, Lila R., and Jane Gillette. 1999. The role of syntax in verb learning. In Handbook of Child Language Acquisition. Edited by William C. Ritchie and Tej K. Bhatia. San Diego: Academic Press, pp. 280–98. [Google Scholar]

- Guiberson, Mark. 2020. Alternatives to Traditional Language Sample Measures with Emergent Bilingual Pre-schoolers. Topics in Language Disorders 40: E1–E6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutiérrez-Clellen, Vera F. 1999. Mediating Literacy Skills in Spanish-Speaking Children with Special Needs. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools 30: 285–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansonn, Kristina, and Ulrika Nettelbladt. 1995. Grammatical characteristics of Swedish children with SLI. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research 38: 589–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haugen, Einar. 1966. Dialect, Language, Nation. American Anthropologist 68: 922–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, Andrew F., and Klaus Krippendorff. 2007. Answering the Call for a Standard Reliability Measure for Coding Data. Communication Methods and Measures 1: 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heilmann, John J. 2010. Myths and Realities of Language Sample Analysis. Perspectives on Language Learning and Education 17: 4–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heilmann, John J., and Marleen F. Westerveld. 2013. Bilingual language sample analysis: Considerations and technological advances. Journal of Clinical Practice in Speech-Language Pathology 15: 87–93. [Google Scholar]

- Heilmann, John J., Ann Nockerts, and Jon F. Miller. 2010. Language Sampling: Does the Length of the Transcript Matter? Language Speech and Hearing Services in Schools 41: 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, Lynne E., Carol Scheffner Hammer, Kristine M. Yont, and J. Bruce Tomblin. 2005. Language sampling for kindergarten children with and without SLI: Mean length of utterance, IPSYN, and NDW. Journal of Communication Disorders 38: 197–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hickey, Tina. 1991. Mean length of utterance and the acquisition of Irish. Journal of Child Language 18: 553–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horton-Ikard, RaMonda. 2010. Language Sample Analysis with Children Who Speak Non-Mainstream Dialects of English. Perspectives on Language Learning and Education 17: 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton-Ikard, RaMonda, Susan Ellis Weismer, and Claire Edwards. 2005. Examining the use of standard language production measures in the language samples of African-American toddlers. Journal of Multilingual Communication Disorders 3: 169–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemi Najafabadi, Yalda, Thomas Klee, and Helen Stringer. 2011. Diagnostic Accuracy of Language Sample Measures in Iranian Persian Speaking Children. [Seminar]. Newcastle: Newcastle University Child Language Seminar. [Google Scholar]

- Klatte, Inge S., Vera van Heugten, Rob Zwitserlood, and Ellen Gerrits. 2022. Language Sample Analysis in Clinical Practice: Speech-Language Pathologists’ Barriers, Facilitators, and Needs. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools 53: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klee, Thomas. 1992. Measuring children’s conversational language. In Causes and Effects in Communication and Language Intervention. Edited by Steven F. Warren and Joe Ernest Reichle. Baltimore: Brookes, pp. 315–30. [Google Scholar]

- Klee, Thomas, and Martha Deitz Fitzgerald. 1985. The relation between grammatical development and mean length of utterance in morphemes. Journal of Child Language 12: 251–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klee, Thomas, Stephanie F. Stokes, Anita M.-Y. Wong, Paul Fletcher, and William J. Gavin. 2004. Utterance Length and Lexical Diversity in Cantonese-Speaking Children with and Without Specific Language Impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 47: 1396–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klee, Thomas, William J. Gavin, and Stephanie F. Stokes. 2007. Utterance length and lexical diversity in American- and British-English speaking children: What is the evidence for a clinical marker of SLI? In Language Disorders from a Developmental Perspective: Essays in Honor of Robin S. Chapman. Edited by Rhea Paul. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum, pp. 103–40. [Google Scholar]

- Kok, Lee Theng. 2011. A Comparison of Mean Length of Utterances (MLU) on Mandarin Child Language Data of Chinese Children within the Age Ranges of 1; 0–6; 11 Years Old: MLUs (Syllable) and MLU-w (Word). Bachelor’s thesis, University of Kebangsaan, Bangi, Malaysia. [Google Scholar]

- Le Normand, Marie-Thérèse, Christophe Parisse, and Henri Cohen. 2008. Lexical diversity and productivity in French pre-schoolers: Developmental, gender and sociocultural factors. Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics 22: 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, Laurence B. 1998. Children with Specific Language Impairment. Cambridge: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Leonard, Laurence B., and Amy L. Weiss. 1983. Application of nonstandardized assessment procedures to diverse linguistic populations. Topics in Language Disorders 3: 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linares, Nicolas. 1983. Rules for calculating Mean Length of Utterances in morphemes for Spanish. In The Bilingual Exceptional Child. Edited by Donald R. Omark and Joan Good Erickson. San Diego: College-Hill Press. [Google Scholar]

- Malvern, David D., and Brian J. Richards. 1997. A new measure of lexical diversity. In Evolving Models of Language. Edited by Ann Ryan and Alison Wray. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters, pp. 58–71. [Google Scholar]

- Malvern, David D., Brian J. Richards, Ngoni Chipere, and Pilar Durán. 2004. Lexical Diversity and Language Development: Quantification and Assessment. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Marchman, Virginia A., and Elizabeth Bates. 1994. Continuity in lexical and morphological development: A test of the critical mass hypothesis. Journal of Child Language 21: 339–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Jon F. 1981. Assessing Language Production in Children: Experimental Procedures. Baltimore: University Park Press. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Jon F. 1991. Quantifying productive language disorders. In Research on Child Language Disorders: A Decade of Progress. Edited by Jon F. Miller. Austin: Pro-Ed, pp. 211–20. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Jon F., and Robin S. Chapman. 1981. The relation between age and mean length of utterances in morphemes. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research 24: 154–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moyle, Maura Jones, Susan Ellis Weismer, Julia L. Evans, and Mary J. Lindstrom. 2007. Longitudinal relationships between lexical and grammatical development in typical and Late-Talking children. Journal of Speech Language and Hearing Research 50: 508–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newton, Brian. 1972. Cypriot Greek: Its Phonology and Inflections. The Hague: Mouton. [Google Scholar]

- Nóro, Letícia Arruda, and Helena Bolli Mota. 2019. Relationship between mean length of utterance and vocabulary in children with typical language development. Revista CEFAC 21: 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, So Jung, Ji Hye Yoon, and YoonKyoung Lee. 2020. A Qualitative Study on Experiences and Needs of Language Sample Analysis by Speech–Language Pathologists: Focused on Children with Language Disorders. Communication Sciences & Disorders 25: 169–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, Amanda J., and Laurence B. Leonard. 2001. Lexical diversity in the speech of normally developing and specific language impaired children. Paper presented at the Twenty Second Annual Meeting of the Symposium for Research in Child Language Disorders, Madison, WI, USA, June 3. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, Matthew D., and Kent Brorson. 2005. A comparative study between mean length of utterance in morphemes (MLUm) and mean length of utterance in words (MLUw). First Language 25: 365–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinker, Steven. 1991. Rules of language. Science 253: 530–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potratz, Jill R., Christina Gildersleeve-Neumann, and Melissa A. Redford. 2022. Measurement properties of Mean Length of Utterance in school-age children. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools 53: 1088–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, Mabel L., Sean M. Redmond, and Lesa Hoffman. 2006. Mean Length of Utterance in Children with Specific Language Impairment and in Younger Control Children Shows Concurrent Validity and Stable and Parallel Growth Trajectories. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 49: 793–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, Mabel L., Filip Smolik, Denise Perpich, Travis Thompson, Nathan Rytting, and Megan Blossom. 2010. Mean Length of Utterance Levels in 6-Month Intervals for Children 3 to 9 Years with and Without Language Impairments. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 53: 333–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roseberry-McKibbin, Celeste. 2007. Language Disorders in Children: A Multicultural and Case Perspective. Boston: Pearson/Allyn and Bacon. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe, Charley, and Kleanthes K. Grohmann. 2013. Discrete bilectalism: Towards co-overt prestige and diglossic shift in Cyprus. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 2013: 119–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, Maria Emília, Sofia Lynce, Sara Carvalho, Mariana Cacela, and Ana Mineiro. 2015. Mean length of utterance-words in children with typical language development aged 4 to 5 years. Revista CEFAC 17: 1143–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxton, Matthew. 2017. Child Language: Acquisition and Development, 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Scarborough, Hollis S. 1990. Index of Productive Syntax. Applied Psycholinguistics 11: 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, Stacy, and Nan Bernstein Ratner. 2002. Measuring lexical diversity in children who stutter: Application of vocd. Journal of Fluency Disorders 27: 289–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevens, John R., Abdullah Al Masud, and Anvar Suyundikov. 2017. A comparison of multiple testing adjustment methods with block-correlation positively-dependent tests. PLoS ONE 12: e0176124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockman, Ida J. 1996. The promises and pitfalls of language sample analysis as an assessment tool for linguistic minority children. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools 27: 355–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakoli, Mahdiye, Nahid Jalilevand, Mohammad Kamali, Yahya Modarresi, and Masoud Motasaddi Zarandy. 2015. Language sampling for children with and without cochlear implant: MLU, NDW, and NTW. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology 79: 2191–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taxitari, Loukia. 2021. Early grammatical development in Cypriot Greek. Journal of Monolingual and Bilingual Speech 3: 40–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taxitari, Loukia, Maria Kambanaros, Georgios Floros, and Kleanthes K. Grohmann. 2017. Early language development in a bilectal context: The Cypriot adaptation of the MacArthur-Bates CDI. In Where Typical and Atypical Language Acquisition Meet Crosslinguistically. Edited by Elena Babatsouli, David Ingram and Nicole Müller. Bristol: Multilingual Matters, pp. 145–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terkourafi, Marina. 2007. Perceptions of difference in the Greek sphere: The case of Cyprus. Journal of Greek Linguistics 8: 60–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas-Tate, Shurita, Julie Washington, Holly Craig, and Mary Packard. 2006. Performance of African American pre-school and kindergarten students on the expressive vocabulary test. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools 37: 143–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thordardottir, Elin T. 2005. Early lexical and syntactic development in Quebec French and English: Implications for cross-linguistic and bilingual assessment. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders 40: 243–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thordardottir, Elin T., and Mahchid Namazi. 2007. Specific language impairment in French-Speaking children: Beyond grammatical morphology. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 50: 698–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tse, Shek Kam, Carol Chan, Sin Mee Kwong, and Hui Li. 2002. Sex differences in syntactic development: Evidence from Cantonese-speaking pre-schoolers in Hong Kong. International Journal of Behavioral Development 26: 509–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiplakou, Stavroula, Spyros Armostis, and Dimitris Evripidou. 2016. Coherence ‘in the mix’? Coherence in the face of language shift in Cypriot Greek. Lingua 172–73: 10–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ukrainetz, Teresa A., and Carol Blomquist. 2002. The criterion validity of four vocabulary tests compared with a language sample. Child Language Teaching and Therapy 18: 59–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voniati, Louiza. 2016. Mean Length of Utterance in Cypriot Greek-speaking Children. Journal of Greek Linguistics 16: 117–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voniati, Louiza, Dionysios Tafiadis, Spyros Armostis, Evangelia I. Kosma, and Spyridon K. Chronopoulos. 2020. Lexical Diversity in Cypriot-Greek-Speaking Toddlers: A Preliminary Longitudinal Study. Folia Phoniatrica et Logopaedica 73: 277–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voniati, Louiza, Spyros Armostis, and Dionysios Tafiadis. 2021. Language sampling practices: A review for clinicians. Evidence-Based Communication Assessment and Intervention 15: 24–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, Gordon. 1975. Coding Manual for the Description of Child Speech, 2nd ed. Bristol: University of Bristol Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wells, Gordon. 1986. The Meaning Makers: Children Learning Language and Using Language to Learn. Portsmouth: Heinemann. [Google Scholar]

- Wilder, Amy, and Sean M. Redmond. 2022. The Reliability of Short Conversational Language Sample Measures in Children with and without Developmental Language Disorder. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 65: 1939–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, Anita M.-Y., Thomas Klee, Stephanie F. Stokes, Paul Fletcher, and Laurence B. Leonard. 2010. Differentiating Cantonese-Speaking pre-school children with and without SLI using MLU and lexical diversity (D). Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 53: 794–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Ji Seung, Carly Rosvold, and Nan Bernstein Ratner. 2022. Measurement of Lexical Diversity in Children’s Spoken Language: Computational and Conceptual Considerations. Frontiers in Psychology 13: 905789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).