Abstract

According to Chomsky’s Labeling Algorithm the merger of two phrases, i.e., {XP, YP}, is labeled either via feature sharing between the two elements or by ignoring the lower copies of movement chains. It is not immediately clear, within this approach, how adjunction structures such as {aP, nP} are to be labeled. In those languages where adjectives show concord with nouns in φ features, the shared features may provide the label.This option is not available for non-concord languages, however. In this paper, we focus on the labeling of {aP, nP} in Turkish, a non-concord language. We claim that the categorizing n0 head in Turkish lacks grammatical features, as a result of which aP fails to find valued instances of its unvalued features. In the absence of feature sharing, aP is marked as a Spell-Out domain, and {aP, nP} is labeled as nP as soon as aP is sent to the interfaces. Since aP in Turkish is a Spell-Out domain, the left-branch extraction of adjectives (i.e., aP movement) is not possible. Moreover, the lack of any grammatical features on n0 in Turkish accounts for the availability of suspension of the plural morpheme.

1. Introduction

One requirement that interface conditions impose on syntactic objects is that they be labeled. In early research on Minimalism, the labeling of a syntactic object was taken to be integral to the structure-building operation Merge (Chomsky 1995). When two syntactic objects, X and Y, are merged into a set, either X or Y is the label of this set. The merger of X and Y has the representation in (1), where Z is the label of the resulting object.

Chomsky (2013) suggests that the labeling of a syntactic object should be dissociated from the structure-building operation Merge. Merge is simply a set-formation operation that takes two syntactic objects as arguments and generates the set that contains them as its sole members (see Collins 2002 and Seely 2006 for the formulation of Merge in (2) in a label-free framework).

Chomsky (2013, p. 43) notes that “[f]or a syntactic object (SO) to be interpreted, some information is necessary about it: what kind of object is it? Labeling is the process of providing that information.” Syntactic objects are labeled by an algorithm that searches for the closest head that can serve as the label (i.e., Labeling Algorithm, LABEL for short). In the case of the merger of a head H and a phrase XP, LABEL, employing Minimal Search, finds the head H as the closest item to label the phrase {H, XP}.1

In the case of the merger of two phrases, the situation is more complex. Unlike (3) above, there is no asymmetry that LABEL can exploit in order to determine the label of the new phrase. That is, the relevant heads, X and Y, are equidistant for labeling purposes.

There are two ways in which the symmetry between XP and YP can be broken so that the merger of XP and YP has a label. Firstly, Chomsky argues, XP can provide the label of {XP, YP} only if every copy of XP is contained in {XP, YP}.2 This means that the lower copy of a chain formed by Internal Merge (i.e., movement) cannot provide the label of the phrase that contains it. Assuming that the DP subject that is merged with vP is the lower copy of a movement chain, which we indicate by putting it in parentheses, we find that DP cannot provide the label of {(DP), vP}. As a result, the label of this syntactic object is vP.

Considering now the merger of the higher copy of the subject DP with TP, i.e., {DP, TP}, we see that both of the heads can in principle be chosen as the label of the new phrase. In this scenario, it is the shared features of DP and TP, obtained via the application of AGREE between DP and T, that serve as the label. Given that DP and T show agreement in φ features, it is the φ features that serve as the label.

Focusing on the consequences of Labeling Algorithm for DP-internal syntax, Carstens (2020) notes that the types of configurations that give rise to labeling problems in verbal syntax are mirrored, in a slightly modified form, in nominal syntax. Consider the example (7) from Turkish, in which a nominal phrase is merged with its external argument. We assume that the external arguments in the nominal domain are introduced with the mediation of the n head, similar to the v head in the verbal domain that introduces the subject.3

More generally, assuming that genitive marked nouns inside possessive constructions are merged with phrases headed by the categorizing n head, we observe that there is no closest head that Labeling Algorithm can choose as the label of such phrases.4

In languages that have grammatical gender, this problem can be solved by the application of gender concord between these two phrases so that the shared feature of gender functions as the label. Carstens (2020) argues that this is the option taken in the Bantu language of Chichewa, in which possessors remain in their base-generated position.

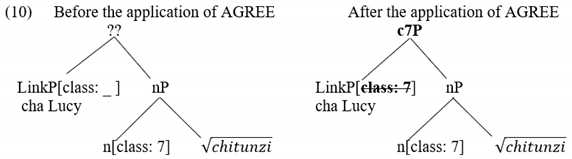

In Chichewa, possessors are introduced with the help of a linker morpheme, which exhibits concord with the head noun. (The head noun undergoes head movement to the D head, which we shall ignore here.) Assuming that gender is introduced as a feature on n0, we find that the label of the possessive construction is provided by the gender feature shared due to the AGREE operation that takes place between Linker Phrase (LinkP) and n0.5

As a result, the merger of LinkP and nP is labelled with the feature shared between these two syntactic objects: class 7.

Observe that there are two conditions that must be met here. Firstly, LinkP must act as a probe that so that feature-sharing between LinkP and the n head is possible. Secondly, n0 must contain valued instances of φ features so that AGREE between LinkP and n0 is successful. The idea that concord targets must act as probes is an assumption that we will come back to when we discuss adjectives below.

| (1) | Merge(X, Y) = {Z, {X, Y}} where Z = X or Z = Y |

| (2) | Merge(X, Y) = {X, Y} |

| (3) | LABEL({H, XP}) = HP (e.g., LABEL({V, DP}) = VP) |

| (4) | LABEL({XP, YP}) = ? (e.g., LABEL({DP, vP}) = ?) |

| (5) | LABEL({(XP), YP}) = YP (e.g., LABEL({(DP), vP}) = vP) |

| (6) | LABEL({XPf, YPf }) = f (e.g., LABEL({DPφ, TPφ}) = φP) |

| (7) | Almanya-nın | Fransa-yı | işgal-i |

| Germany-GEN | France-ACC | occupation-3SG.AGR | |

| ‘The German occupation of France’ | |||

| [?? [DP Almanya-nın] [nP Fransa-yı işgal-i]] | |||

| (8) | [?P [DP possessor] [nP n ]]] |

| (9) | [DP | [D chi-tunzi+D] | [ch-abwino | ch-a | Lucy | <chi-tunzi>]] |

| 7-picture | 7-nice | 7.of | 1.Lucy | 7-picture |

|

| (11) | Label({LinkPc7, nPc7}) = c7P |

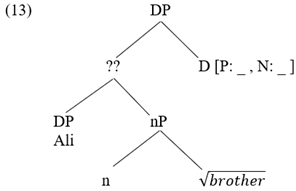

This analysis of Chichewa possessive constructions raises the question of how similar constructions obtain their label in languages that lack grammatical gender. In a language like Turkish, for instance, it is not immediately clear how the merger of a possessor with its possessum is to be labeled given that there is no gender concord between them. The initial representation of (12) is shown in (13).

Carstens argues that this labelling problem is solved with the movement of the possessor to the specifier of DP (i.e., possessor raising, see Öztürk and Erguvanlı Taylan (2016) for some recent arguments for DP-internal DP movement in Turkish). Since the possessor DP in (13) is a lower copy of a movement chain, it cannot provide the label of the phrase that contains it.

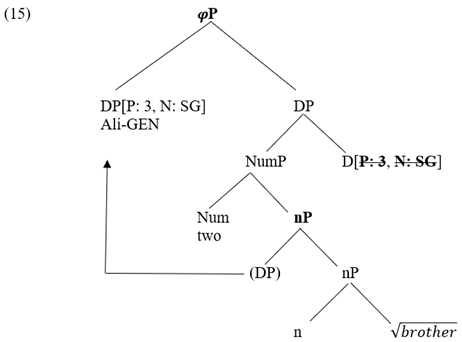

The higher copy of the possessor agrees with the D head in φ features (person and number). Therefore, the label of the phrase that immediately contains the higher copy of the possessor is φP. The representation of (12), under these assumptions, would be as in (15).

Unlike possessors, which must move to a higher position inside DP in some languages, adjectival adjuncts remain in their base-generated position. This means that when an adjective is merged with a noun, the resulting phrase poses a labeling problem, one that is not typically solved with the movement of the adjective phrase.

The only option that there is for providing a label for {aP, nP} is feature sharing. (We shall discuss languages with no grammatical gender in Section 2). For this to be possible, it must be that nominal adjuncts in general and adjectives in particular are universally probes for φ features (gender and number), an assumption we make explicit in (17). Note that, given the Probe Universal, adjectives function as probes even in languages, such as Turkish, that lack overt manifestation of concord on the assumption that adjectives are universally nominal adjuncts.

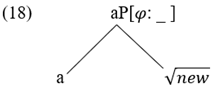

Following Heinat (2005) and Carstens (2020), we assume that the probe status of a head can be projected to the phrase that it labels. This means that aPs universally have the representation in (18).7

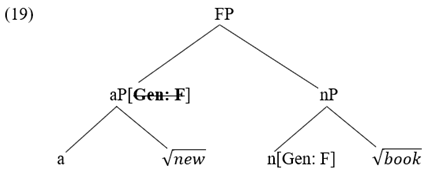

Similar to possessors in Chichewa, the application of AGREE between aP and n makes it possible for {aP, nP} to have a label (Yoo 2018).

Given the theory of labeling in Chomsky (2013, 2015), and assuming that, unlike DPs, aPs are not typically targets of movement, we find that feature-sharing is the only way for a structure such as (19) to have a label (Yoo 2018). This means in languages where gender is introduced on n0 gender concord between adjectives and nouns is expected to be obligatory. One important piece of evidence for this claim comes from the research that suggests a link between idiosyntactic (i.e., non-semantic) gender and gender concord (Bayırlı 2017; Norris 2019). To understand the nature of this relationship, let us first observe there are two main types of gender-assignment systems: semantic and idiosyntactic (Corbett 1991; Kramer 2020). In some languages, the gender of almost all nouns can be predicted by their meaning (i.e., the semantic systems of gender assignment). For instance, Tamil (Genus: Southern Dravidian, Family: Dravidian) makes a three-way distinction in gender: masculine, feminine, and neuter. Corbett (1991, p. 9) notes that in Tamil, “given the meaning of a noun, its gender can be predicted without reference to its form”. Note also that gender in a semantic system can very well be a grammatical category. In Tamil, for instance, finite verbs agree with the subject in gender and number (as well as person).

| (12) | Ali-nin kardeş-i |

| Ali-GEN brother-3SG.AGR | |

| ‘Ali’s brother’ |

|

| (14) | LABEL({(DP), nP} = nP |

|

|

| (17) | The Probe Universal (for nominal adjuncts6) |

| Nominal adjuncts are universally probes. |

|

|

A semantic gender system should be distinguished from another type of gender system in which there appears to be no clear semantic basis for gender of many nouns. A table representing the idiosyncratic nature of Russian gender is presented below (adapted from Corbett 2013):

We characterize Russian as an idiosyncratic gender language, where idiosyncratic gender systems are understood to be the complement set of semantic gender systems (for languages that have gender as a grammatical category).8 We assume, moreover, that gender in idiosyncratic gender languages is a feature on n0 (Kramer 2015; see also Kramer 2016 for an overview of the syntactic representation of gender). Recall that, given the Probe Universal, gender concord is expected to obligatory in such languages. On the basis of evidence from Feature 32A: Systems of Gender Assignment (Corbett 2013) in the online database The World Atlas of Language Structures (WALS, Dryer and Haspelmath 2013), Bayırlı (2017) claims that languages with idiosyncratic gender are, indeed, gender concord languages. This is stated in (21) as the Gender Concord Universal.

We have already seen, for instance, that Russian is a language with an idiosyncratic gender system. This means that we expect Russian adjectives to show gender concord with the noun they modify. As is well-known, this prediction is borne out (Corbett 1991, p. 106).

Note that GCU provides strong support for the conjecture in (17) that adjectives are universal probes. Assuming that gender in an idiosyncratic gender language is a feature on n0, we find that, for GCU to be a valid generalization, adjectives in these languages must act as probes. Otherwise, there could very well be an idiosyncratic gender language in which adjectives fail to exhibit concord with the head noun,9 simply because they are not specified as probes. This possibility is ruled out by GCU providing some independent support for the idea that adjectives are universal probes.

| (20) | Idiosyncratic Gender in Russian | |||||

| Masculine | Feminine | Neuter | ||||

| žurnal | magazine | gazeta | newspaper | pis’mo | letter | |

| stul | chair | taburetka | stool | kreslo | armchair | |

| avtomobil | car | mašina | car | taxi | taxi | |

| ogon’ | fire | peč’ | stove | plamja | flame | |

| glaz | eye | ščeka | cheek | uxo | ear | |

| lokot’ | elbow | lodyška | ankle | koleno | knee | |

| čas | hour | minuta | minute | vremja | time | |

| (21) | The Gender Concord Universal (GCU) | |

| If | a language has an idiosyncratic gender system, | |

| Then | this language has gender concord on adjectives. | |

| (22) | nov-yj žurnal | nov-aja kniga | nov-oe pis’mo |

| new-M magazine | new-F book | new-N letter | |

| ‘new magazine’ | ‘new book’ | ‘new letter’ |

2. When aP Is Spelled-Out

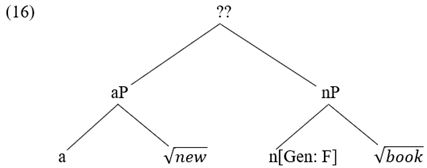

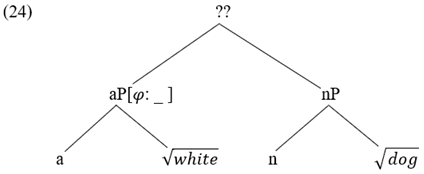

What we have seen up to this point is that if we adopt Chomsky’s labeling algorithm, the only way {aP, nP} structures can be labeled is via the application of AGREE. There are, however, languages in which adjectives and nouns do not exhibit concord in φ features. In Turkish, for instance, adjectives do not agree with nouns in number or case features (and gender is not a grammatical category at all).

Given that there seems to be no feature sharing between aP and n, it is not clear how {aP, nP} structures in such languages are to be labeled.

We suggest that the labeling of a syntactic object is sensitive to Spell-Out domains. We propose that when AGREE between the aP probe and the n head fails, aP is marked as a Spell-Out domain, as a result of which it is sent to the interfaces, becoming inaccessible to label {aP, nP}. Here is the proposal:

Spelling out aP in {aPuφ, nP} serves a dual function. First, it eliminates unvalued features (on aP) from the syntactic representation. This is achieved not by providing them with a value but by delivering them to the interfaces where they are given a default value at PF and, presumably, deleted or ignored at LF. Second, this operation makes it possible for {aP, nP} to have a label by making nP the only candidate for labeling purposes. In what follows, we discuss these consequences of the Spell-Out operation as applied to aPs.

| (23) | Küçük(*-ler-e) | beyaz(*-lar-a) | köpek-ler-e | doğru |

| small-PLU-DAT | white-PLU-DAT | dog-PLU-DAT | towards | |

| ‘toward small white dogs’ | ||||

|

| (25) | In {αuF, β} where β does not contain a suitable goal, |

| α is marked as a Spell-Out domain |

The interaction between Spell-Out domains and labeling has been worked out in previous research (Kiyang and Wonbin 2016; Takita et al. 2016; Gallego 2018). The crucial assumption we make here is that when a constituent α is Spelled-Out, it is eliminated from syntactic representation (Ott 2011), becoming inaccessible for labeling purposes. For instance, when the complement of the phasal v head, i.e., VP, is spelled-out, VP is no longer accessible for labeling. Assuming that a singleton containing a syntactic object SO, generally a lexical item, is identical to its member (Chomsky 2012; Goto 2013; Narita 2014), we obtain the representations in (26), where the label can be designated as vP.

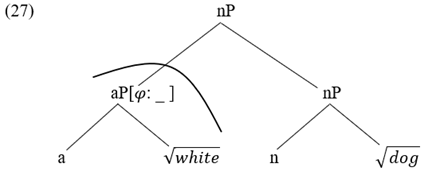

We claim that {aP, nP} structures in non-concord languages are labeled in a similar fashion. Once the aP node is spelled out, nP is the only grammatical category accessible to Minimal Search for labeling purposes.10

In (27), the aP node is sent to the interfaces with unvalued φ features. It has been claimed that syntactic objects that contain unvalued/uninterpretable features are illicit at the interfaces, which leads to ungrammaticality (Chomsky 2000, 2001). However, recent work on φ agreement suggests that while a probe must initiate the search for valued instances of its unvalued features, the failure to find them is tolerable (i.e., the derivation does not “crash”) and does not result in ungrammaticality (Preminger 2014); AGREE between a probe and a potential goal must be attempted, but in the absence a viable goal in the (c-command) domain of the probe, its failure is not catastrophic for the derivation.

| (26) | {… {DP, {v, VP}}} | Before Spell-Out |

| {… {DP, {v}}} | After Spell-Out | |

| {… {DP, v}} | {lex} = lex | |

| LABEL({DP, v}) = vP | ||

|

Before we delve into the details of the consequences of the representation in (27) for Turkish, let us provide some independent evidence for the claim that aPs in non-concord languages are, indeed, Spell-Out domains. To do so, we must first clarify our assumptions about how and when Spell-Out domains become inaccessible for syntactic operations at the phase level. There has been some indeterminacy as to when exactly a Spell-Out domain is sent to the interfaces. Chomsky (2000) adopts a version of Phase Impenetrability Condition (PIC) in which the YP complement of a phasal head H is sent to the interfaces as soon as HP is completed.

Chomsky (2001), on the other hand, suggests that while the YP complement of a phasal head H1 is marked as a Spell-Out domain, it remains accessible to the syntactic operations until the next phase head H2 is introduced to the structure. That is, it is only after the merger of another phase head H2 that YP is transferred to LF and PF.

In the weak version of PIC, YP is sent to the interfaces as soon as a new phase head (one that does not mark YP as a Spell-Out domain) is merged to the structure. In {aPuφ, nP}, there is no phase head that marks aP as a Spell-Out domain. Rather, aP is marked as a Spell-Out domain so that {aPuφ, nP} can have a label. In the spirit of (29), we suggest that aP is sent to the interfaces as soon as a phase head is introduced to the structure. Our assumption about the timing of the Spell-Out of aPuφ is given below:

On the assumption that D0 is a phasal head, aP is spelled-out as soon as D0 is merged to the structure. In this way, aP is eliminated from the structure upon the merger of D0, and the phrase can be labeled as nP.11

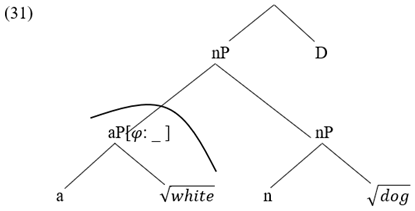

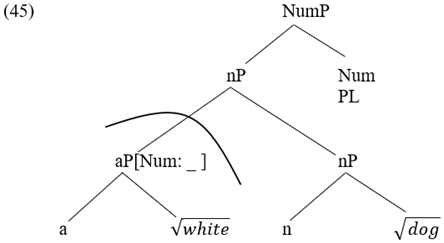

One consequence of PIC is that the movement of a phrase XP to a position γ proceeds though the edge of each phase separating XP and γ (i.e., successive cyclic movement). We see in (31), however, that aP is sent to the interfaces as soon as the phasal D0 head is merged, becoming inaccessible for any syntactic operations at DP or higher phases. This leads to the prediction that in languages that lack concord between adjectives and nouns, aP movement out of nP, in descriptive terms the left-branch extraction (LBE) of adjectives, is not possible. The A/N Agreement Generalization, proposed in Bošković (2009) and further elaborated in Yoo (2018), provides evidence for this prediction.

As expected under the A/N Agreement Generalization, aP-movement is not acceptable in non-concord languages (Yoo 2018, p. 19).

The ungrammaticality of aP fronting in non-concord languages is a direct consequence of aP in such languages being a Spell-Out domain,12 as we have just discussed.13

| (28) | Phrase Impenetrability Condition (strong version) |

| In [H2P H2 … [H1P X [H1 YP]]], where H1 and H2 are phase heads, | |

| YP is a Spell-Out domain and | |

| YP is inaccessible for operations outside of H1P. |

| (29) | Phrase Impenetrability Condition (weak version) |

| In [H2P H2 … [H1P X [H1 YP]]], where H1 and H2 are phase heads, | |

| YP is a Spell-Out domain and | |

| YP is inaccessible for operations at H2P. |

| (30) | In {αuF, β} where β does not contain a suitable goal, |

| α is marked as a Spell-Out domain | |

| α is transferred to PF and LF upon the merger of a phase head |

|

| (32) | The A/N Agreement Generalization |

| Only adjectives that agree with the noun they modify can undergo left-branch extraction. |

| (33) | a. | *pissan1 | [C-ka | [t1 chayk]-ul | satta] | (Korean) |

| expensive | C-NOM | book-ACC | bought | |||

| ‘C bought an expensive book.’ | ||||||

| b. | *takai1 | [C-ga | [t1 hon]-o | kata] | (Japanese) | |

| expensive | C-NOM | book-ACC | bought | |||

| ‘C bought an expensive book.’ | ||||||

Turkish presents a more complex empirical situation. Bošković and Şener (2014) observe that while aP fronting is not acceptable, the movement of aP to the post-verbal domain is not completely ruled out.

While the ban on aP fronting can be understood to be an instance of the A/N Agreement Generalization, the availability of the post-verbal aP scrambling is something of a puzzle. Kornfilt (2003a) notes that this latter operation is not completely free either. While postposing aPs out of a non-case-marked argument is possible (as in (35)b), case-marked DPs seem to function as barriers for aP movement.

In this paper, we suggest that since attributive aPs in Turkish are marked as Spell-Out domains and are spelled out as soon as a phasal head is introduced to the structure, there is no such operation as aP postposing in Turkish. What looks like aP in (35)b is actually a reduced relative clause (see Tat 2011 for a reduced relative analysis of adjectives in Turkish). That is, what is postposed in (35)b is not an aP but a relative clause containing the aP. Some independent evidence for this claim comes from the behavior of non-predicative adjectives such as tek “only”, ana “main”, eski “former”.

As expected, adjectives such as tek “only”, ana “main”, eski “former” are unacceptable inside relative clauses, where they would have to occupy a predicate position.

If the claim that what is postposed in (35)b is not an aP but a relative clause is on the right track, then non-predicative adjectives should be unacceptable in the post-verbal position given that they cannot have an underlying relative-clause syntax. This is, indeed, what we find.

Note that the objects in (39)a–c are not case-marked. That means that the unacceptability of these sentences cannot be attributed to the ban on scrambling out of case-marked arguments, as we seen in (36). Rather, we suggest that the reason why the sentences in (39) are unacceptable is that aPs in Turkish cannot be targets of movement operation. The reason is that aPs are marked as Spell-Out domains when they fail to find valued instances of their unvalued features and such domains are eliminated from syntactic representation as soon as the next phase head is added to the structure.

| (34) | Pelin kalın kitap oku-du |

| Pelin thick book read-PST | |

| ‘Pelin read a thick book.’ | |

| (35) | a.* kalın1 [Pelin [ t1 kitap] okudu]] |

| b.? [Pelin [ t1 kitap] okudu] kalın1 |

| (36) | *[Dün | sokak-ta | [t1 bir adam-a] | rastla-dı-m] | çok yaşlı1 |

| yesterday | street-LOC | a man-DAT | meet-PST-1SG | very old | |

| ‘I met a very old man in the street yesterday.’ | |||||

| (37) | a. | *Caddenin karşı-sın-daki | yol | ana-∅. |

| street-Gen opposite-3.SG.AGR-ADJ | road | main-COP.3SG | ||

| Int. ‘The road across the street is a main road.’ | ||||

| b. | *Siyah saç-lı | çocuk | tek-∅. | |

| black hair-DER | child | only-COP.3SG | ||

| Int. ‘The dark-haired child is an only child.’ | ||||

| c. | *Orada-ki | bakan | eski-∅. | |

| there-ADJ | minister | former-COP.3SG | ||

| Int. ‘The minister there is a former minister.’ | ||||

| (38) | a. | Ana (*ol-an) | yol-u | bul-mak | uzun sür-dü. |

| main (be-REL) | road-ACC | find-INF | long last-PST | ||

| ‘It took a long time to find the main road.’ | |||||

| b. | Tek (*ol-an) | çocuk-lar-ı | büyüt-mek zor-∅. | ||

| only (be-REL) | child-PLU-ACC | raise-INF | difficult-COP.3SG | ||

| ‘It is difficult to raise an only child.’ | |||||

| c. | Eski (*ol-an) | bakan ile | buluş-tu-k | ||

| former be-REL | minister COM | meet-PST-1PL | |||

| ‘We met the former minister.’ | |||||

| (39) | a. | *[Saat-ler-dir | [t1 yol] | arı-yor-uz] | ana1 |

| hour-PLU-ADV | road | look.for-IMPF-1PL | main | ||

| ‘We have been looking for a/any main road for hours.’ | |||||

| b. | *[Biz de | [t1 çocuk] | büyüt-üyor-uz] | tek1 | |

| we also | child | grow-IMPF-1PL | only | ||

| ‘We are also raising an only child.’ | |||||

| c. | *[Şirket | [t1 bakan] | istihdam.ed-ecek] | eski1 | |

| company | minister | hire-FUT | former | ||

| ‘The company will hire a/any former minister.’ | |||||

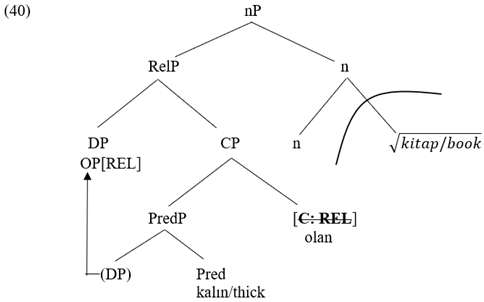

How is it possible for relative clauses to move to the post-verbal domain? To answer this question, we first need to understand how a relative clause obtains its label. For concreteness, we shall adopt an operator-movement approach to relative clauses (Chomsky 1977 and much subsequent work), where the C head probes for an operator in its c-command domain in order to check its unvalued feature. As a result of the AGREE operationbetween the C head and the operator, the whole clause is labeled as RelP (as opposed to QP, which is the label for indirect questions). The head of the relative clause is then externally merged with RelP, which gives us the representation in (40).

Following Arad (2003) and Marantz (2007), we assume that category-defining heads, here n0, are phasal heads. Consequently, the complements of such heads are marked as Spell-Out domains, and they are spelled out as soon as the next phasal head is added to the tree. At the next phase level, the label of the merger of RelP and the external nominal head is determined as follows:

We see that, unlike aPs, relative clauses are not marked as Spell-Out domains. As a result, they can be targeted for movement operations by the higher phase heads.

|

| (41) | {… {RelP, {n, }}} | Before Spell-Out |

| {… {RelP, {n}}} | After Spell-Out | |

| {… {RelP, n}} | {lex} = lex | |

| LABEL({RelP, n}) = nP | ||

3. Consequences of a Featureless Life: Plural Suspension

In this section, we take a closer look at plural suspension in Turkish, which, we claim, provides independent support for the idea that plural in Turkish is not a feature on n0.

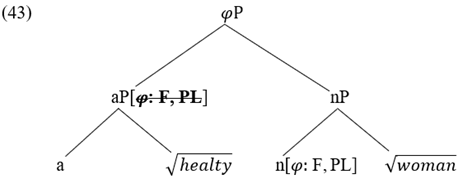

Our focus in Section 1 was the mechanism responsible for the labeling of {aP, nP} structures in languages with gender concord on adjectives. As is well-known, gender is not the only category relevant for nominal concord. When adjectives in a language show concord with the noun they modify, concord morphology usually involves the full set of feature of that noun (e.g., gender, number and case). Leaving the issue of case concord aside,14 we shall focus on φ-concord (gender and number) on adjectives and the lack thereof. As an example, consider Kubachi, a Northeast Caucasian language of Dagestan, Russia. Adjectives in in Kubachi show concord with nouns in gender15 and number (Vamling and Tchantoria 1991).

We can account for φ concord in Kubachi on the assumption that the category-defining n head is the host of valued instances of gender and number features. Being universal φ-probes, adjectives find these features in their c-command domain and delete their unvalued features.16

Consider now Turkish, a language that lacks grammatical gender. Given that adjectives are universal probes for φ features, it seems reasonable to assume that adjectives in Turkish probe for a number feature. If number were a feature on n0, we would expect Turkish to exhibit number concord. This is, of course, not what we find.

This means that number in Turkish cannot be a feature on the n head. We assume, then, that number in Turkish is introduced as a functional projection that merges with nP. As a result, number is not within the c-command domain of the aP probe.17

Independent evidence for the claim that the plural feature in Turkish is not integral to the category-defining n head comes from a type of construction that came to be called “suspended affixation” (Lewis 1967; Orgun 1995; Kornfilt 1996, 2012; Kabak 2007; Akkuş 2016; Atmaca 2021). In these constructions, one or more inflectional elements that are morphologically realized on the second conjunct take semantic scope over both conjuncts. In (46), for instance, while the plural morpheme is marked on the second conjunct, it semantically affects both of the nouns.

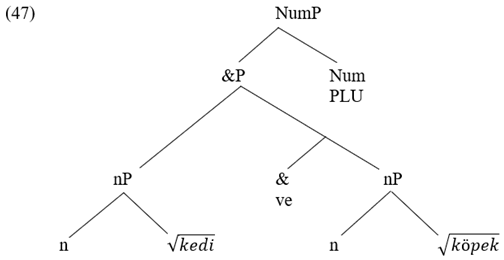

In order to account for the semantic scope of plural over conjunction in (46), we suggest that the syntactic representation of plural suspension in Turkish is as in (47).18 It is to be noted, again, that under this representation, number is not a property of n0 but a functional projection on its own.

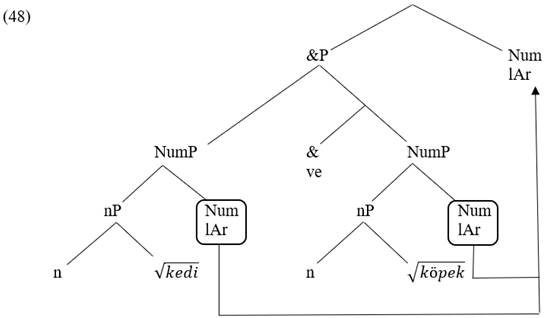

In a rare syntactic analysis of suspension constructions in Turkish, Kornfilt (2012) claims that only inflectional morphemes such as number and case that project a functional category (NumP and KP, respectively) allow suspension. The availability of plural interpretation for both conjuncts in suspension constructions is accounted for on the assumption that such constructions have an underlying representation in which each noun is associated with a distinct, independent number projection hosting the plural feature. Under Kornfilt’s analysis, an expression such as kedi ve köpek-ler (i.e., cat and dog-PLU) is derived via Right Node Raising of the plural morpheme. This claim can be implemented in terms of Across-the-Board movement of plural, as shown in (48).

In this way, Kornfilt accounts for the semantic equivalence between (46) and (49), and more generally between expressions of the form [A and B]-PLU and [A-PLU] and [B-PLU].

In what follows, we show that there are cases where suspension constructions are not semantically equivalent to their counterparts with no suspension. To account for these discrepancies, we claim that an expression of the form [A and B]-PLU is not really derived via Right Node Raising from a syntactic representation that involves coordination of NumPs. That is, [A and B]-PLU has the representation in (47), where plural is directly merged with the coordinated nouns, rather than the one in (48).

| (42) | Singular | Plural | ||

| I.Male | arazi-w adame | aražu-b adamte | ‘healthy man/men’ | |

| II.Female | arazi-j x:unul | aražu-b x:unne | ‘healthy woman/women’ | |

| III.Other | arazi-b h:a:wan | aražu-d h:a:wante | ‘healthy animal/animals’ |

|

| (44) | beyaz(*-lar) | köpek-ler |

| white-PLU | dog-PLU | |

| ‘white dogs’ | ||

|

| (46) | Sokağ-ı | [kedi ve köpek]-ler doldur-muş | |

| street-ACC | cat and dog-PLU | fill-EVID | |

| ‘The street is full of cats and dogs.’ | |||

|

|

| (49) | Sokağ-ı | kedi-ler | ve köpek-ler | doldur-muş |

| street-ACC | cat-PLU | and dog-PLU | fill-EVID | |

| ‘The street is full of cats and dogs.’ | ||||

Winter and Scha (2015) note that there are three possible interpretations of coordinated plurals. The first one is the union interpretation where the predicate is understood to apply to all the individuals in the sum of the extension of the coordinated nouns.

In Turkish, the union interpretation is available with both suspension and non-suspension constructions, giving some initial credence to the idea that suspension constructions are derived from their non-suspended counterparts.19

A second interpretation for conjoined plurals is the semi-distributive interpretation, under which the predicate is understood to be distributed over both conjuncts.

This is one of the interpretations in which suspension constructions and their counterparts with no suspension give us differing results. While both constructions allow for union readings, the semi-distributive interpretation is easily available with the coordination of pluralized nouns. With the suspension of plural, however, this interpretation is not available (or at least, considered to be quite misleading).

The third interpretation for conjoined plurals is the symmetric interpretation, under which the sentence is judged to make a statement that affects both of the plural individuals symmetrically.

Such an interpretation is easily available for constructions involving coordination of pluralized noun. However, suspension constructions do not seem to license this inference. Instead, we get a reading in which there was an arbitrary separation of the men and the women, where each group is expected to contain some men and some women.

To summarize, semi-distributive and symmetric interpretations do not seem to be available with plural suspension constructions. Winter and Scha (2015) note that what semi-distributive and symmetric interpretations have in common is that they require access to the plural individuals as distinct entities.

We suggest that these observations can be explained on the assumption that NumP coordination yields a set of plural individuals rather just the sum (i.e., the union) of two plural individuals.20 The distinction between taking the sum of two plural individuals and forming the set of the two plural individuals is that the set of the plural individual keeps the plural individuals differentiated in the set, while the sum operation creates a flat object with both plural individuals as subparts.21 The observation that the semi-distributive and the symmetric interpretations are not available with suspension structures can be understood to be a consequence of the fact that the conjunction of nPs corresponds to the SUM operation, and this operation can only give rise to undifferentiated plural individuals. On the other hand, the semantic import of NumP conjunction is set formation. After the application of this operation, each plural individual is still accessible for semantic manipulation, as required for the semi-distributive and symmetric interpretations. On the basis of this discussion, we conclude that plural suspension in Turkish must be analyzed as the direct merger of the plural feature with coordinated nPs (as in (47)) rather than across-the-board movement of the plural morpheme from coordinated NumPs (as in (48)).

| (50) | a. | The girls and the boys met | (a meeting of a mixture of boys and girls). |

| b. | The soldiers and the policemen surrounded the factory. | ||

| (51) | a. | Asker | ve polis-ler | bina-yı | sar-dı | |

| soldier | and police-PLU | building-ACC | surround-PST | |||

| b. | Asker-ler | ve | polis-ler | bina-yı | sar-dı | |

| soldier-PLU | and police-PLU | building-ACC | surround-PST | |||

| ‘The soldiers and the policemen surrounded the building.’ | ||||||

| (52) | The girls and the boys met. ≈ The girls met and the boys met. |

| (53) | a. | Park-ta | bugün | kadın-lar | ve erkek-ler | buluş-tu |

| park-LOC today woman-PLU and man-PLU meet-PST | ||||||

| ‘Today the women met and the men met in the park.’ | ||||||

| b. | #Park-ta | bugün kadın | ve erkek-ler | buluş-tu | ||

| park-LOC today woman and man-PLU | meet-PST | |||||

| ‘Today the women met and the men met in the park.’ | ||||||

| (54) | The girls and the boys were separated from each other. |

| ≈ The girls were separated from the boys and the boys were separated from the girls. |

| (55) | a. | Kadın-lar | ve erkek-ler | birbirlerin-den | ay(ı)r-ıl-dı-lar |

| woman-PLU | and man-PLU | each.other-ABL | separate-PASS-PST-3PLU | ||

| ‘The women were separated from the men and the men were separated from the women.’ | |||||

| b. | #Kadın | ve erkek-ler | birbirlerin-den | ay(ı)r-ıl-dı-lar | |

| woman | and man-PLU | each.other-ABL | separate-PASS-PST-3PLU | ||

| Int. ‘The women were separated from the men and the men were separated from the women.’ | |||||

| (56) | Semi-distributive: meet({P, Q}) ≈ meet(P) & meet(Q) |

| Symmetric: were_separated({P,Q}) ≈ were_separated(P, Q) & were_separated(Q,P) |

In this section, we have provided independent evidence for the claim that plural in Turkish is not a feature on n0 but a projection of its own. We have shown that plural suspension constructions are obtained via direct merger of the plural feature with coordinated nPs.

4. Conclusions

In this paper, we have addressed the issue of how {aP, nP} structures are labeled in natural languages. In concord languages, the features that are shared between aP and n0 can provide the label, an option that is not available in non-concord languages such as Turkish. We have argued that being universal probes, aPs always search their domain for valued instance of their unvalued φ features. In non-concord languages, this search fails due to a lack of grammatical features on n0. As a result, aP is marked as a Spell-Out domain, and {aP, nP} gets to be labeled as nP as soon as aP is transferred to the interfaces. The main evidence for this claim comes from the immobility of adjectival adjuncts in non-concord languages. Finally, we have provided some evidence that plural in Turkish is not a feature on n0. The availability of plural suspension in Turkish is a consequence of plural being an independent, functional projection.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | There is some controversy as to when exactly syntactic objects are labeled. For Chomsky, the labeling of the output of Merge takes places at the point of transfer of the syntactic objects to the interfaces, i.e., at the phase level. Under this view, labeling is not required for syntactic computation to proceed but for the successful interpretation of syntactic objects at the interfaces. Bošković (2015), on the other hand, suggests that labeling takes place as early in the derivation as possible. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | Collins and Stabler (2016) defines the contain-relation as follows:

Under this definition, the contain-relation is the transitive closure of the immediately-containrelation. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | One reviewer asks about the source of the ACC marker on Fransa “France”. Indeed, the presence of ACC-assigning nouns in Turkish is something of a puzzle for theories in which ACC is assigned by v0. In a recent analysis of such constructions, Solak (2021) argues that such nouns are composed of a verbal stem, which is associated with a silent deverbalizing head (see also Keskin 2009 for arguments against a silent light verb analysis). For discussion, see Sezer (1991) and Akkuş (2015). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | Following Chomsky (2013), we assume that category-neutral roots cannot act as labelers. Hence, the merger of a category-defining head and a root is labeled by the category-defining head. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5 | It is sometimes suggested that for the successful application of AGREE between a probe and a goal, it is necessary that the goal have some unvalued features that make it active (i.e., the Activity Condition). Throughout the paper, we will ignore this condition. For arguments against the relevance of this condition for AGREE, see Nevins (2004). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6 | A natural question that comes to mind at this point is whether other concord targets such as numerals, determiners, and demonstratives can be said to be universal probes. This depends, mostly, on our assumptions about their syntactic representation. If demonstratives are functional heads that select for a complement, then {Dem, nP} can be labeled as DemP in the absence of AGREE. In other words, there is no need for agreement between the Dem head and nP for {Dem, nP} to have a label. If demonstratives are adjuncts on nPs, then they must function as probes so that {DemP, nP} can have a label. This availability of these two options in the context of demonstratives might actually be what is needed for representing different types of demonstratives in Levantine Arabic (Shlonsky 2004). In this head-initial language, there are two types of demonstratives. The first one shows adjectival pattern in that it is postnominal (similar to adjectives) and shows concord for gender and number (again, similar to adjectives).

The second demonstrative seems to behave as a functional head. It precedes its complement, and it differs from adjectives in that it does not show concord.

This pattern follows directly from the interaction of concord with labeling possibilities. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7 | Adjectives typically show concord in gender, number, and case features. Therefore, it would be more accurate to represent the aP probe as aP[φ: _; K: _], where φ represents gender and number features, and K represents case features. In this paper, we will not be concerned with the nature of case concord on adjectives since integrating case concord into the standard AGREE-based analysis of nominal concord has proved non-trivial (see Privizentseva 2020 for an analysis of case concord that is in line with the assumptions in this paper and see Danon 2011 and Norris 2014 for a discussion of distinct mechanisms for case concord). Since the generalization we propose in this section is about the obligatoriness of gender concord on adjectives, our focus here is feature valuation in terms of gender (See Section 3 for number concord). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8 | Note that even in idiosyncratic systems, nouns that denote human individuals of a certain gender are privileged so that such nouns are typically specified with the gender of their referent. The situation with non-human nouns is different. The gender of non-human nouns, and especially that of inanimate noun, tends to be unpredictable from their meaning. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 9 | Bayırlı (2017) discusses two types of potential counterexamples to GCU. In languages such as Alagwa (Cushitic), Bayso (Cushitic), Mosetén (Mosetenan), and Rendille (Cushitic), it is not the adjectives that show concord with the head noun but the linker morpheme, which is obligatory in introducing attributive adjectives to the structure. Such languages can be given an analysis in the spirit of the linker-agreement phenomenon we have seen in the context of Chichewa possessive constructions. In Supyire (Gur) and Ju|’hoan (Kx’a), on the other hand, adjectives are morphologically incorporated into nouns, which is why, Bayırlı claims, they fail to show concord. See Bayırlı (2017) for the details of these claims and Norris (2019) for further discussion. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10 | It is sometimes suggested that category-defining heads such as n0, a0, and v0 are phase heads (Arad 2003; Marantz 2007; Embick 2010), an assumption that we will also make in the context of labeling of relative clauses at the end of Section 2. If categorizing heads are phase heads, then their complements are Spell-Out domains. Note that this assumption would not solve the labeling problem associated with {aP, nP} structures.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 11 | Saito (2016) proposes that overt case marking on a DP prevents it from projecting its label. That is, in some languages, overt case marking functions as a label blocker (see Miyagawa et al. (2019) for a general analysis of label blockers and label inducers). In a sense, what Spell-Out domains do within the analysis developed in this paper resembles what overt case marking does in Saito’s analysis. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12 | Yoo (2018) proposes that in non-concord languages {aP, nP} should remain labelless (following similar ideas about adjunction in Hornstein and Nunes 2008; Hunter 2010). In fact, under Yoo’s analysis, what blocks aP movement in non-concord languages is the fact that, as a consequence of aP movement, {(aP), nP} would have to be labeled as nP. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 13 | It must be noted that there is no universal ban on aP fronting. In many concord languages, aP fronting is acceptable (Bošković 2009, 2013). The reason is that when {aP, nP} is labeled via feature-sharing, aP need not be marked as a Spell-Out domain. Therefore, aPs in concord languages can be moved to the edge of the next phase and beyond.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 14 | Throughout the paper, we ignore case concord for the reason that integrating case concord into an AGREE-based framework of nominal concord has lead to some questions that remain largely unaddressed and mostly unresolved. While gender and number can be understood to be φ features on the n head, case is typically analyzed as being assigned to a DP from an outside source (v or P). It is not clear how exactly a feature on DP percolates down onto all the concord targets inside DP. One analysis of case concord that is compatible with the rest of this paper belongs to Privizentseva (2020), who claims that, in addition to gender and number, case is also a valued feature on n0. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 15 | Kubachi has a three-gender/-class system. Following the literature on the Caucasian languages, we indicate genders with roman numerals (i.e., I, II, III). Class I is typically for males, class II for females, and class III is the elsewhere gender. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 16 | One reviewer asks what it means to say that the label of a phrase is φP. Within the labeling theory, the function of labels is to distinguish syntactic objects from each other. That is, a phrase that is labeled as φP is of a different kind from a phrase that is not labeled as such. Observe that both the merger of {aP, nP} and the merger of {DP, TP} are labeled as φP, and we probably do not want to say that these two syntactic objects are of the same kind. It is important, at this point, to note that φP is an abbreviation for an ordered tuple of φ features. In the merger of {aP, nP}, the shared features are gender and number (and case, which we ignore in this paper). For {DP, TP}, the shared features contain gender, number, and person. Since (Gen, Num, Case) is not equivalent to (Gen, Num, Person), these syntactic objects can be distinguished. The problem that the reviewer highlights is not completely solved, however. Recall that in Turkish, both possessive DPs and tensed matrix clauses are labeled as φP, where φ, in each case, includes number and person. Moreover, nominalized embedded clauses in Turkish, both TP and CP varieties (see Kornfilt 2003b), are labeled as φP. The question of how to distinguish between these syntactic objects remains open. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 17 | There are approaches to agreement in natural languages that allow (and sometimes require) the goal to c-command the probe for the succesful application of AGREE (Baker 2008; Zeijlstra 2012; Bjorkman and Zeijlstra 2019, a.o.). In this paper, we adopt the standard approach, in which the goal must be within the c-command domain of the probe (Chomsky 2000, a.o.). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 18 | Chomsky (2013) argues against analyses in which a conjunction construction is labeled &P on the grounds that coordinators are devoid of features and cannot provide the label of the coordinated complex. Instead, he argues, coordination has an underlying structure in which coordinators are sisters, as in [and [α β]]. The remerge of α with [and [α β]] (i.e., [α [and [βP (α) β]]]) makes is possible for [(α) β] to be labeled as βP. Moreover, since coordinators are featureless, the whole complex is labeled as αP (i.e., [αP α [and [βP (α) β]]]). This, in effect, corresponds to Zhang’s (2010) analysis in which the first conjunt, which occupies a specifier position, is responsible for the label of the whole conjunction structure (i.e., [αP α [and β]]). In this paper, we sidestep the issue of the proper analysis of coordination structures within the Labeling Algorithm framework and simply assume that conjunction constructions have the label &P. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 19 | The examples that are presented below were first discussed in Bayırlı (2017) and further elaborated in Bayırlı (2022). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 20 | This means that we need to re-define the domain so that it includes “nested individuals”. As shown in Winter and Scha (2015), this can be done in the following manner: Let E be a set of entities. Let D0 = E and for every i > 0 Di = Di−1 ∪ {A ⊆ Di−1: |A| > 2} A domain D over E is the union of all Dj from some j ≥ 0 D = D0 ∪ D1 ∪ D2 ∪ … | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 21 | The distinction can be appreciated with the following correspondences. A plural individual can be thought of as the set of atoms that make up this individual. The Sum of two plural individuals can be thought of as the union of these two sets. However, if we apply Set Formation to the sets that characterize the plural individuals, we obtain a set whose members are the two sets that characterize the plural individuals. To summarize, let P and Q be plural individuals, and let P’ and Q’ be their set-theoretic correspondances. P’ = {p: ATOM(p) and p ≤ P} Q’ = {q: ATOM(q) and q ≤ Q} SUM(P,Q) ≈ P’ ∪ Q’ = {r: r is a member P’ or r is a member of Q’} SET-FORMATION(P,Q) ≈ {P’, Q’}. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- Akkuş, Faruk. 2015. Light verb constructions in Turkish: A case for DP predication and blocking. In Proceedings of the 9th Workshop on Altaic Formal Linguistics. Edited by Andrew Joseph and Esra Predolac. Cambridge: MITWPL, pp. 133–45. [Google Scholar]

- Akkuş, Faruk. 2016. Suspended affixation with derivational suffixes and lexical integrity. Mediterranean Morphology Meetings 10: 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Arad, Maya. 2003. Locality constraints on the interpretation of the roots: The case of Hebrew denominal verbs. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 21: 737–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atmaca, Furkan. 2021. Suspended Affixation Needs No Morphological Word: -(y)Ip. In Proceedings of Tu+6. Edited by Songül Gündoğdu, Sahar Taghipour and Andrew Peters. Suite: Linguistic Society of America. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, Mark. 2008. The Syntax of Agreement and Concord. Cambridge: CUP. [Google Scholar]

- Bašić, Monika. 2009. Left branch extractions: A remnant movement approach. In Proceedings of Novi Sad Generative Syntax Workshop. Edited by Ljiljana Subotić. Novi Sad: University of Novi Sad, pp. 39–51. [Google Scholar]

- Bayırlı, İsa Kerem. 2017. The Universality of Concord. Ph.D. dissertation, MIT, Cambridge, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Bayırlı, İsa Kerem. 2022. Türkiye Türkçesinde Ertelenmiş Çekim Eklerinin Dilbilimsel Analizi. Akademik Dil ve Edebiyat Dergisi 6: 378–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjorkman, Bronwyn M., and Hedde Zeijlstra. 2019. Checking Up on (φ-)Agree. Linguistic Inquiry 50: 527–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bošković, Željko. 2009. On Leo Tolstoy, its structure, Case, left-branch extraction, and prosodic inversion. In Studies in South Slavic Linguistics in Honor of E. Wayles Browne. Columbus: Slavica Publishers, pp. 99–122. [Google Scholar]

- Bošković, Željko. 2013. Adjectival escapades. In Proceedings of Formal Approaches to Slavic Linguistics. Edited by Steven Franks, Markus Dickinson, George Fowler, Melisa Whitcombe and Ksenia Zanon. Ann Arbor: Michigan Slavic Publications, vol. 21, pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Bošković, Željko. 2015. From the Complex NP Constraint to everything: On deep extractions across categories. The Linguistic Review 32: 603–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bošković, Željko, and Serkan Şener. 2014. The Turkish NP. In Crosslinguistic Studies on Noun Phrase Structure and Reference. Edited by Patricia Cabredo Hofherr and Anne Zribi-Hertz. Leiden: Brill, pp. 102–40. [Google Scholar]

- Carstens, Vicki. 2020. Concord and labeling. In Agree to Agree: Agreement in the Minimalist Programme. Edited by Peter W. Smith, Johannes Mursell and Katharina Hartmann. Berlin: Language Science Press, pp. 71–116. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, Noam. 1977. On wh-movement. In Formal Syntax. Edited by Peter W. Culicover, Thomas Wasow and Adrian Akmajian. New York: Academic Press, pp. 71–132. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, Noam. 1995. The Minimalist Program. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, Noam. 2000. Minimalist inquiries. In Step by Step: Essays on Minimalist Syntax in Honor of Howard Lasnik. Edited by Roger Martin, David Michaels and Juan Uriagereka. Cambridge: MIT Press, pp. 89–155. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, Noam. 2001. Derivation by phase. In Ken Hale: A Life in Language. Edited by Michael Kenstowicz. Cambridge: MIT Press, pp. 1–52. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, Noam. 2012. Poverty of the stimulus: Willingness to be puzzled. In Rich Languages from Poor Inputs. Edited by Massimo Piattelli-Palmarini and Robert Berwick. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 61–67. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, Noam. 2013. Problems of projection. Lingua 130: 33–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chomsky, Noam. 2015. Problems of projection: Extensions. In Structures, Strategies and Beyond: Studies in Honour of Adriana Belletti. Edited by Elisa Di Domenico, Cornelia Hamann and Simona Matteini. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, Chris. 2002. Eliminating labels. In Derivation and Explanation in Minimalist Syntax. Edited by Samuel David Epstein and T. Daniel Seely. New York: Wiley, pp. 42–64. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, Chris, and Edward Stabler. 2016. A Formalization of Minimalist Syntax. Syntax 19: 43–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbett, Greville. 1991. Gender. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Corbett, Greville. 2013. Systems of Gender Assignment. In The World Atlas of Language Structures Online. Edited by Matthew S. Dryer and Martin Haspelmath. Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. Available online: http://wals.info/chapter/32 (accessed on 15 July 2022).

- Danon, Gabi. 2011. Agreement and DP-Internal Feature Distribution. Syntax 14: 297–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dryer, Matthew S., and Martin Haspelmath, eds. 2013. The World Atlas of Language Structures Online. Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. Available online: http://wals.info (accessed on 18 November 2022).

- Embick, David. 2010. Localism versus Globalism in Morphology and Phonology. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gallego, Ángel J. 2018. Projection without agreement. The Linguistic Review 35: 601–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goto, Nobu. 2013. Labeling and scrambling in Japanese. Tohoku: Essays and Studies in English Language and Literature 46: 39–73. [Google Scholar]

- Heinat, Frederik. 2005. Why phrases probe. In The Department of English in Lund: Working Papers in Linguistics. Edited by Frederik Heinat and Eva Klingvall. Lund: Lund University, vol. 5, pp. 33–63. [Google Scholar]

- Hornstein, Nobert, and Jairo Nunes. 2008. Adjunction, Labeling and Bare Phrase Structure. Biolinguistics 2: 57–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, Timothy. 2010. Relating Movement and Adjunction in Syntax and Semantics. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Maryland, College Park, MD, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Kabak, Barış. 2007. Turkish suspended affixation. Linguistics 45: 311–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keskin, Cem. 2009. Subject Agreement-Dependency of Accusative Case in Turkish—Or Jump-Starting Grammatical Machinery. Utrecht: LOT. [Google Scholar]

- Kiyang, Kwon, and Lee Wonbin. 2016. Relative Clauses and Labeling Algorithm. New Korean Journal of English Language and Literature 58: 173–93. [Google Scholar]

- Kornfilt, Jaklin. 1996. On some copular clitics in Turkish. ZAS Papers in Linguistics 6: 96–114. [Google Scholar]

- Kornfilt, Jaklin. 2003a. Scrambling, subscrambling, and case in Turkish. In Word Order and Scrambling. Edited by Simin Karimi. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, pp. 125–55. [Google Scholar]

- Kornfilt, Jaklin. 2003b. Subject Case in Turkish Nominalized Clauses. In Syntactic Structures and Morphological Information. Edited by Uwe Junghanns and Luka Szucsich. New York: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 129–215. [Google Scholar]

- Kornfilt, Jaklin. 2012. Revisiting “suspended affixation” and other coordinate mysteries. In Functional Heads: The Cartography of Syntactic Structures. Edited by Laura Bruge, Anna Cardinaletti, Giuliana Giusti, Nicola Munaro and Cecilia Poletto. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 181–96. [Google Scholar]

- Kramer, Ruth. 2015. The Morphosyntax of Gender. Oxford Studies in Theoretical Linguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, vol. 58. [Google Scholar]

- Kramer, Ruth. 2016. The location of gender features in syntax. Language and Linguistics Compass 10: 661–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, Ruth. 2020. Grammatical gender: A close look at gender assignment. Annual Review of Linguistics 6: 45–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, Geoffrey. 1967. Turkish Grammar. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Marantz, Alec. 2007. Phases and words. In Phases in the Theory of Grammar. Edited by Sook-Hee Choe. Seoul: Dong in Publisher. [Google Scholar]

- Miyagawa, Shigeru, Danfeng Wu, and Masatoshi Koizumi. 2019. Inducing and blocking labeling. Glossa: A Journal of General Linguistics 4: 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, Andrew. 2020. Left-Branch Extraction and Barss’ Generalization: Against a remnant movement approach. In Proceedings of the 38th West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics. Edited by Rachel Soo, Una Y. Chow and Sander Nederveen. Somerville: Cascadilla Proceedings Project, pp. 294–304. [Google Scholar]

- Narita, Hiroki. 2014. Endocentric Structuring of Projection-Free Syntax: Phasing in Full Interpretation. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Nevins, Andrew Ira I. 2004. Derivations without the Activity Condition. In Perspectives on Phases MIT Working Papers in Linguistics 49. Edited by Martha McGinnis and Norvin Richards. Cambridge: MITWPL, pp. 287–310. [Google Scholar]

- Norris, Mark. 2014. A Theory of Nominal Concord. Ph.D. dissertation, UCSC, Santa Cruz, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Norris, Mark. 2019. A typological perspective on nominal concord. Proceedings of the Linguistic Society of America 4: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orgun, Cemil Orhan. 1995. Flat vs branching morphological structures: The case of suspended affixation. Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society 21: 252–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ott, Dennis. 2011. A note on free relative clauses in the theory of phases. Linguistic Inquiry 42: 183–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztürk, Balkız, and Eser Erguvanlı Taylan. 2016. Possessive constructions in Turkish. Lingua 182: 88–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preminger, Omer. 2014. Agreement and Its Failures. Linguistic Inquiry Monographs 68. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Privizentseva, Mariia. 2020. Eligibility at PF: Ellipsis and concord in Moksha. In Proceedings of the 38th West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics (WCCFL). Edited by Rachel Soo, Una Y. Chow and Sander Nederveen. Somerville: Cascadilla Proceedings Project, pp. 366–76. [Google Scholar]

- Saito, Mamoru. 2016. (A) case for labeling: Labeling in languages without phi-feature agreement. The Linguistic Review 33: 129–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seely, T. Daniel. 2006. Merge, derivational c-command, and subcategorization in a label-free syntax. In Minimalist Essays. Edited by Cedric Boeckx. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 182–217. [Google Scholar]

- Sezer, Engin. 1991. Issues in Turkish Syntax. Ph.D. dissertation, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Shlonsky, Ur. 2004. The form of Semitic noun phrases. Lingua 114: 1465–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solak, Ercan. 2021. Accusative licensing of nouns in Turkish. In Proceedings of the 6th Workshop on Turkic and Languages in Contact with Turkic. Edited by Songül Gündoğdu, Sahar Taghipour and Andrew Peters. New York: Linguistic Society of America. [Google Scholar]

- Takita, Kensuke, Nobu Goto, and Yoshiyuki Shibata. 2016. Labeling through Spell-Out. The Linguistic Review 33: 177–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tat, Deniz. 2011. APs as reduced relatives: The case of Bir in some varieties of Turkic. In Proceedings of WAFL7. Edited by Andrew Simpson Linguistics. MIT Working Papers in Linguistics. Cambridge: MIT, vol. 62. [Google Scholar]

- Vamling, Karina, and Revaz Tchantouria. 1991. Sketch of the Grammar of Kubachi. The Simple Sentence. Working Papers 30. Lund: Lund University Department of Linguistics. [Google Scholar]

- Winter, Yoad, and Remko Scha. 2015. Plurals. In The Handbook of Contemporary Semantic Theory. Edited by Shalom Lappin and Chris Fox. Hoboken: Wiley Online Library. [Google Scholar]

- Yoo, Yong Suk. 2018. Mobility in Syntax: On Contextuality in Labeling and Phases. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Zeijlstra, Hedde. 2012. There is only one way to agree. The Linguistic Review 29: 491–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Niina Ning. 2010. Coordination in Syntax. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).