Abstract

This study investigates whether peer interaction in a second language (L2) using written computer-mediated communication (CMC or text chat) may function as a bridge into oral performance. By designing and sequencing tasks according to the SSARC model of task complexity (we also examine its effects on L2 development. Finally, we explore the role of learners’ affective variables for L2 performance and development. Fifteen low–intermediate adolescent refugee learners of L2 English in the Netherlands participated in the study. Using a within-subject pre-test post-test design, we examined their language performance in both text-based CMC and face-to-face (F2F) tasks before and after a task-based classroom intervention. Results show that the intervention had a significant and strong effect on most of the linguistic measures of complexity, accuracy, and fluency (CAF). Similar gains in text chat and oral interaction provide evidence that a direct transfer of language experiences across modalities can occur. Together with the fact that most participants valued the use of written CMC in the classroom, our findings indicate that increasingly complex text chat tasks can be an effective way to promote the oral skills of language learners. We discuss our findings in light of how the design of written CMC tasks can afford L2 development across modalities.

1. Introduction

In recent years, dynamic usage-based (DUB) approaches to language learning and teaching have gained ground in Second Language Acquisition (SLA) research and practice (cf. Lowie et al. 2020; Rousse-Malpat et al. 2022; Tyler et al. 2018). DUB sees language use as the driving force of second language (L2) learning (de Bot et al. 2005, 2007), since lexical and structural forms may only be acquired in a meaningful context, where new L2 form–use–meaning mappings (FUMMs), (Verspoor 2017) can be established. Since the COVID pandemic, online communication has become even more embedded in our everyday lives (Ocando Finol 2019), and it forms a major source of authentic language use, supporting L2 learning and teaching (Ito et al. 2008; Lai and Zhao 2006). In particular, authentic interaction via (written) computer-mediated communication (CMC)1 can be a fruitful way to develop the L2 (cf. Blake 2017; Lin et al. 2013; Sauro 2011). Earlier work has shown that in CMC modes, learners feel more involved in the learning process and in the development of ideas, as well as in selecting and directing conversation topics (Chapelle 2009; Ortega 1997). Furthermore, exchanges of L2 learning peers via CMC have been shown to promote interaction (Blake 2000), and seem to generate positive effects on learners’ attitudes, language anxiety, motivation, and perceived joy (Beauvois 1997; Darhower 2002; González-Lloret and Ortega 2014; Michel 2018). CMC discourse patterns also include a wide range of social and language functions (Abrams 2001).

As long as digital facilities (soft- and hardware) are available in the foreign language (FL) classroom, written CMC (or text chat) can afford L2 teaching, because chat tasks that can be performed in parallel in classes with many students, are known to foster participation among more introverted learners, and to allow teachers to monitor multiple peer interactions concurrently (Chapelle 2009). Yet, task design plays a major role in determining the effectiveness of CMC activities (Smith and González-Lloret 2021). In the current paper, we investigate how a series of written CMC tasks that are sequenced according to Robinson’s (2005) SSARC model (cf. Baralt et al. 2014) may support the L2 oral development of adolescent learners of English in the Netherlands. With the focus on text chat modality, our investigation adds a novel dimension to research on task complexity and L2 writing. At the same time, we are addressing a gap identified by Smith and González-Lloret (2021) in their recent research agenda for technology-mediated task-based language teaching (TBLT).

1.1. Written CMC and the Transferability to Oral Production

Smith and González-Lloret (2021) remind us that for any technological tool, it is important that its affordances fit the pedagogic aim. Earlier theoretical and empirical work advocates that the specific characteristics of written CMC tasks should provide an ideal context for language learning (Sauro and Smith 2010). First, text chat can be seen as a hybrid between the form-oriented written register and highly interactive, spontaneous oral conversation (Pelletieri 2000). Accordingly, given that text chat shares the interactive and more informal nature of oral face-to-face (F2F) communication, it may be a useful stepping stone for oral language development. Specifically, it has the potential to develop the same cognitive mechanisms underlying spontaneous conversational speech (cf. Payne and Whitney 2002), such as those proposed by Levelt’s (1989) blueprint of the speaker. Blake (2009) goes as far as to argue that apart from the articulatory motor skills of oral communication vs. the hand motor skills needed for text chat typing, the two modalities might be equally useful ways of developing oral fluency. Hence, both facilitate the automatization of lexical and grammatical retrieval during meaningful, authentic interaction. In short, text-based chatting could be an effective medium for improving L2 oral skills.

On the other hand, text chat shares important characteristics with written production, which makes it a powerful medium to benefit from concepts underlying the idea of ‘writing to learn a language’ (Manchón 2011). That is, given the salience and permanence of the written modality, text chat provides learners with time for formulating, monitoring, and editing their messages (Sauro and Smith 2010) and therefore, presumably, enhances learners’ interlanguage (Abrams 2003; Blake 2000, 2009, 2017; Michel 2018). The literacy context is also linked to more form-oriented language processing, eliciting language of linguistic complexity and discourse patterns typically associated with writing (Abrams 2003; Blake 2009; González-Lloret and Ortega 2014). As such, text-based CMC has the potential to practice and facilitate the transfer of meaning- and form-focused linguistic processing, typically associated with written production, to L2 oral performance.

Over the years, scholars found evidence for the potential impact of written CMC on L2 oral language development, that is, that positive effects of written L2 chat would be transferable across modalities to L2 spoken performances. Indeed, the early work by Smith (1990) and Beauvois (1997) provided evidence that learners who participated in online written interactions displayed higher scores in oral communicative skills compared to control groups. Similarly, Payne and Whitney (2002) investigated the impact of text-based CMC on L2 oral skills while also taking working memory capacity into account. Participants in the experimental group who had engaged in weekly chat-based interactions scored notably higher on oral tasks (following ACTEFL guidelines) than the control population did. Their data further indicated that low working memory students showed greater gains. The authors explained that text chat practice would develop the same cognitive processes underlying spontaneous oral communication, and that low working memory learners particularly benefited from the additional processing time provided by the written modality. This interpretation was corroborated by a follow-up study conducted by Payne and Ross (2005), whose data suggested that text chat tasks would reduce the cognitive load of tasks.

Abrams (2003) compared groups of intermediate-level German learners working on text-based versus oral chat discussions on designated topics. Oral performance development was measured by the number of idea units (i.e., c-units) and measures of Complexity, Accuracy, and Fluency (CAF). Results revealed that text-based CMC tasks led to significantly higher scores regarding fluency, while accuracy and complexity were not significantly affected. More recently, Razagifard (2013) examined the effects of synchronous and asynchronous text-based CMC on oral fluency development by implementing a task-based language teaching (TBLT) lesson plan. The intermediate learners of English (N = 63) worked on four different communicative tasks (i.e., jigsaw; decision-making; opinion exchange; problem-solving). Findings indicated that both synchronous and asynchronous text-based CMC can improve L2 learners’ oral fluency when guided with appropriate language learning tasks. Similarly, research comparing L2 learners and native speakers, as well as studies looking into the effects of different forms of CMC activities (e.g., asynchronous vs. synchronous tasks), demonstrated that text chat supports L2 oral development, most prominently in measures of fluency, and at times also on accuracy and research-specific indices (e.g., Blake 2000, 2009; Dussias 2006; Satar and Özdener 2008).

Overall, the previously reviewed studies provide evidence that text chat can be an effective means to support L2 oral development, with most efforts focusing on fluency. The current study expands this earlier work as we investigate the effect of task-based chatting on oral development by using holistic, general, and task-specific linguistic measures. More specifically, we aim to build on theoretical accounts (e.g., González-Lloret and Ortega 2014; Smith and González-Lloret 2021) advocating that design, use, and evaluation of CMC activities should be guided by sound pedagogic rationales, such as the task-based approach (see East 2021 for an excellent recent overview).

1.2. Task-Based Language Teaching, Task Complexity and Task Sequencing

Following usage-based perspectives on language learning, the task-based language teaching (TBLT) account argues that learners need to perform meaningful tasks such that they engage in authentic L2 use (be it receptive, productive, or both), which in turn will promote language learning (East 2021). Tasks provide input as well as eliciting output, often embedded in (peer) interaction, thereby, building on the main insights of communicative and interactionist perspectives on language learning and teaching (cf. Loewen and Sato 2018, for a recent review). Of the many definitions that have been brought forward for the construction of tasks, we will draw on Samuda and Bygate (2008, p. 93), who see a task as ‘a pedagogic activity which requires communicative language use, in order to achieve a pragmatic outcome other than to practice or learn a language, but with the overall aim of promoting language development.’ Following Willis (1996), a task-based lesson typically consists of (i) a pre-task phase, where learners are introduced to the topic and non-linguistic goal, and experience a model performance; (ii) the main phase, where learners engage in performing a task themselves and report on their outcome; and (iii) the post-task phase, when analysis of and reflection on the task-performance is conducted. At all phases, a focus on language is possible, for example, through input flooding and/or enhancement during the pre-task, reactive focus on form and recasts during the main task phase, and guided reflection and even explicit instruction in the post-task phase. A task-based lesson series, that includes several pre-main, post-task cycles, needs to consist of pedagogic tasks (e.g., several narrative story retellings) that work together towards reaching the real-world target task (e.g., being able to talk about a personal experience). Thereby, factors influencing task-based performance, such as task repetition (Bygate 2001), planning time (Ellis 2003), and task complexity (e.g., Robinson 2001; Skehan and Foster 2001) act as guiding principles for taking informed pedagogic decisions. In the current study, we draw on the principle of task complexity.

Task complexity, that is, the cognitive load which a task puts forward (Révész et al. 2016) has received ample attention in task-based research. In this paper, we adopt Robinson’s (2001) perspective, which states that increased task complexity along so-called resource-directing variables (e.g., adding elements or perspective taking) induces heightened attention to language form, and thus promotes language learning. More specifically, in his SSARC model, Robinson (2010) claims that tasks should be sequenced in such a way that at first, tasks allow for simple and stable (SS) performance. Next, increases in procedural and performative demands (e.g., reducing planning time) lead to automatization (A) of processes. Only in the final stage should high demands on both performative and conceptual demands (e.g., increased task complexity through introducing more elements) be implemented, in order to induce restructuring (R) of the current language system of the learner and push them to higher levels of complexity (C) of their linguistic repertoire. Together, a SSARC sequence will foster language development.

Earlier work investigating the SSARC model has not provided unanimous support (see studies gathered in Baralt et al. 2014) and more research is needed. For example, Lambert and Robinson (2014) found that while expert ratings comparing a SSARC with a control group performing oral narrative tasks suggest that the former was more successful in reaching the communicative goal than the latter, neither measures of syntactic and lexical complexity nor of accuracy found differences between the groups. The authors posited that individual differences might influence the effectiveness of SSARC sequencing. To the best of our knowledge, no empirical study has investigated written performance within a SSARC approach, nor is there work considering affective variables interacting with such an approach. The current study aims to address this gap by using SSARC sequencing as the basis for pedagogical treatment tasks. In addition, we will be exploring differences in affective factors that might influence L2 performance and development in the context of written CMC.

1.3. Motivation and Anxiety Influencing and Influenced by Written CMC Activities

In the past decades, technological innovation has had major effects on language learning and teaching. Its impact on theory and practice, particularly during and following the COVID pandemic, cannot be underestimated. Yet, it is important to realize that ‘just putting something in the digital sphere’ does not make it better or more exciting. As such, Smith and González-Lloret (2021) argue that instructors need to be careful to ensure that any technological tool supports the pedagogic aim of L2 instruction. Following their comprehensive review, González-Lloret and Ortega (2014) present the conclusion that technology-mediated tasks can boost students’ engagement, participation, motivation, and creativity, while also reducing anxiety.

In this paper we draw on Dörnyei’s (2001) construct of motivation, taking a dynamic perspective and acknowledging its multifaceted nature. We selected this because it incorporates the key theoretical concepts (e.g., motivational intensity, intrinsic motivation, ideal L2 self, instrumental motivation, international orientation, etc.), which has been shown to play an important role in L2 learning. Recent empirical work has further demonstrated that in technology-mediated contexts, both cognitive and social factors contribute as well as the task and context (see Kormos et al. 2020 for further reading). Specifically for written CMC, previous research suggests that it positively impacts motivation, increases learners’ participation, and leads to a higher quantity of language output than in F2F contexts, positively influencing turn-taking and dialogue management (see the early work by, e.g., Chun 1994; Kelm 1992; Kern 1995; and, more recently, Michel 2018).

In the present paper, we follow the definition by Scovel (1978), who refers to Foreign Language Anxiety as the way in which the learner feels and reacts at a particular moment in response to a call for communication. Building on the fact that text chat allows more time for input and output processing, Beauvois (1992) suggested that it lowers perceived communicative stress and increases students’ willingness to communicate (e.g., Ziegler 2016). Yet, empirical data by Baralt and Gurzynski-Weiss (2011), comparing anxiety levels between F2F and written CMC modalities, found no differences—although learners’ overall perceptions of CMC use were positive. Satar and Özdener (2008) examined student perceptions of the text and voice chat tasks, finding that beginner learners evaluated text chat tasks as decreasing their anxiety. Michel (2018), who explored teenage learners of German working on text chat tasks, evaluated motivation and task appraisal along with anxiety levels. The high schoolers demonstrated medium to high motivation, relatively high appreciation of the tasks, and medium anxiety levels. It appeared that language output anxiety was associated with task perceptions, indicating that this construct played a major role in their appreciation of the CMC activities. Students also perceived the written CMC practice to be beneficial for both written and oral interaction.

From this short review, it is clear that more research is needed into the extent to which written CMC tasks might influence learners’ L2 motivation and language anxiety, and vice versa. The present study aims to address this gap.

1.4. Purpose of the Present Study and Research Questions

Building on principles of technology-mediated task-based and usage-based L2 instruction (East 2021; Smith and González-Lloret 2021; Verspoor 2017), this study set out to investigate the effectiveness of a series of text chat task cycles on the oral development of adolescent L2 learners of English in the Netherlands by taking into account affective variables such as motivation, anxiety, and CMC task perceptions. More specifically, we asked the following research questions.

RQ:

- How does a task-based text chat instructional intervention that has adopted the SSARC model of task complexity (Robinson 2015) for task sequencing affect the oral task-based performance of L2 learners as gauged by measures of fluency, global and task-specific accuracy, as well as a holistic measure of functional language use?Based on Levelt’s (1989) model of language processing and previous claims (e.g., Payne and Whitney 2002; Payne and Ross 2005; Razagifard 2013), it was hypothesized that the SCMC learning outcomes would transfer to F2F communication. It was expected that all general measures of language proficiency would show an overall increase over time to a lesser or greater extent. It was also expected that the task-specific variables (i.e., accurate use of the target structures), would display the greatest degree of development (Robinson and Gilabert 2007).

- How does a task-based text chat instructional intervention that adopted the SSARC model of task complexity (Robinson 2015) for task sequencing relate to learners’ motivation, anxiety, and perceived use of these written CMC activities?Considering previously mixed findings, no specific hypothesis was determined. This research question was also examined by calculating the frequency of ratings on the complementary questions and tapping into the students’ and teacher’s comments. From the review of the literature (e.g., Baralt and Gurzynski-Weiss 2011; Ziegler 2016; Michel 2018), it was hypothesized that the use of SCMC in the classroom would be regarded as beneficial for language learning, as well as less stressful than F2F communication.

2. Materials and Methods

This study used a within-subject design to explore the effects of written CMC practice on F2F oral development by implementing an ecologically valid treatment, including pre-/post-test data collection in students’ regular language classes, stretching seven weeks.

2.1. Participants

Four male and eleven female refugees2 attending vocational training in the Netherlands participated in the study (Meanage = 19, SD = 4.4). All had completed primary school education in their country of origin (i.e., Syria, Iran, Gambia, Sudan, and Eritrea) and spoke, next to their native language, several other languages, including Dutch and English. They were currently learning the latter in a class targeting A2 level (CEFR, Council of Europe). The study was approved by a member of the University of Groningen Ethics Review Board, details of the procedure were explained to all participants, and informed consent was obtained. Tapping into the classroom teacher’s suggestions, we matched the students in pairs of two and one group of three, taking into account their gender and language background.

2.2. Materials

2.2.1. Pre-/Post-Tasks

The same two six-picture-based narrative surprise tasks from Heaton (1975) were used as pre- and post-tests. For the oral task, the original version was used, while for text chat, the pictures were slightly changed in case participants preferred to describe stories about females rather than males or vice versa. Versions were counterbalanced across participants.

2.2.2. Treatment Tasks

Over the course of three weeks, participants collaboratively worked by means of text chat interaction on a series of increasingly cognitively complex narrative tasks, following principles of the SSARC model (Robinson 2015). Tasks were based on three different video clips of Mr. Bean (Swimming Pool, Sleepy, Hospital)—the originals being video-edited to reduce them to four to six minutes—where task complexity was manipulated on the factor ± a few elements (Robinson 2001; post-task questionnaires gauging perceived task difficulty confirmed the manipulation; Révész et al. 2016). Each task cycle consisted of material for pre- and main tasks. PRE included a captioned video of two advanced speakers modeling oral task performance plus a pre-task vocabulary activity; MAIN encompassed a full-color worksheet with screenshots of each video clip (10, 14, and 16 frames in the simple, middle, and complex versions, respectively, equally distributed over the two participants), useful model structures (e.g., In the picture I can see) plus task instructions on using text chat to jointly reconstruct the story of the Mr. Bean clip, cf. Appendix A).

2.2.3. Questionnaires on Participant Characteristics and Affective Factors

Questionnaires were used to collect information about participants’

(a) demographic characteristics (e.g., age, gender);

(b) affective factors of motivation and anxiety (adapted from Kormos et al. 2011; Michel 2018):

Using a six-point Likert scale, participants indicated their (dis)agreement with thirty statements on language learning anxiety, instrumental motivation, intrinsic motivation, motivational intensity, ideal L2 self, international orientation, anxiety they may feel when chatting in English, and the use of technology to support learning English. Following Oxford and Burry-Stock (1995), items were collated into underlying constructs and tested for internal consistency, which was good for all subscales (Cronbach’s alpha between 70% and 80%), after removing several items (i.e., one statement originally related to motivation intensity, one originally related to intrinsic motivation, one originally related to ideal L2 self, and one originally related to instrumental motivation) (cf. Appendix B);

(c) eight questions targeting students’ perceptions of the CMC tasks (cf. Michel 2018) (cf. Appendix C).

2.3. Procedure

The project was fully implemented into students’ regular English classes across seven weeks, starting with introducing the project and collecting participants’ informed consent and demographic characteristics in week 1, and the oral and written text chat pre-tasks in week 2. Week 3, 4, and 5 were used for the treatment tasks, which means that each week, they first watched the modeling video clip and performed the vocabulary activity (ca. 30 min) before engaging in the text chat narrative task with their peer, followed by a brief perceived task difficulty evaluation (ca. 20 min). Week 6 and 7 were used for oral and written post-task performances as well as the questionnaires on affective factors. Finally, 15-min oral interviews targeting students’ and the teacher’s perceptions of written CMC for language learning were conducted. These consisted of a few predetermined open-ended questions targeting the students’ and the teacher’s perceptions of CMC in the FL classroom, such as “Do you feel less anxious when you chat or when you speak in English?” and “Do you think chat interaction helps students to learn something? Does it boost speaking skills?”

The first author collected all the data and administered the pre-, post-, and treatment tasks as well as the interviews.

2.4. Soft- and Hardware

Participants used their own mobile phones to interact with each other during the text chat tasks using WhatsApp messenger. After each task performance, they exported and emailed their conversation to the first author. The Easy Voice Recorder mobile application was used for collecting spoken data.

2.5. Coding and Analyses

Pre-/post-task data were manually coded by the first author. Speech samples were transcribed verbatim before they could be analyzed. The same or similar measures for oral and text chat were used to measure fluency, global and task-specific accuracy, and functional language use (cf. Michel 2017). Table 1 provides an overview of the used measures. Accordingly, oral fluency was gauged as speaking rate (SR, number of syllables per second) and the average length of filled and unfilled pauses (Kormos and Denes 2004); text chat fluency was established in terms of the number of words and clauses per speaker per chat log (Wolfe-Quintero et al. 1998).

Table 1.

Measures of fluency, global and task-specific accuracy, and functional language use.

Following Kuiken and Vedder (2008) and Foster and Wigglesworth (2016), errors were classified in terms of their degree of severity (1st = 0.5 points: minor mistakes such as omitted articles; 2nd = 1 point: more severe mistakes like incorrect lexical choices and agreement errors; 3rd = 1.5 points: errors that make an utterance nearly incomprehensible, such as omissions of verbs). Each clause or Analysis of Speech (AS) unit was assigned a score based on its accuracy, and a total ratio of errors per 50 words was calculated per speaker (Foster and Wigglesworth 2016).

In order to complement these global indices and tap even slight differences in performance, task-specific accuracy measures were included (Robinson and Gilabert 2007), the accurate use of present continuous, existential there is/there are and can + infinitive. These structures were chosen as they seemed to be naturally elicited by the narrative tasks at hand. For each of the three measures in every task, the total score for each participant was the number of correctly used target structures.

Functional task completion (Kuiken et al. 2010) was evaluated by means of a holistic assessment of participants’ performances using Storch’s (2005) 5-scale global evaluation scheme (cf. Appendix D), which was adapted to the content of the tasks we employed. This evaluation considered the content and structure of the transcripts, as well as the degree of task fulfillment.

Answers to questionnaire items on motivation, anxiety, and perceived use were aggregated into scores per construct. For the current analysis, responses to the interview questions were transcribed, and illustrating quotes were inserted into the discussion to complement the quantitative data.

2.6. Data Analyses

The data analysis calculated descriptive statistics for the different measures for oral and text chat pre-/post-tasks. In order to address the first research question, paired-sample t-tests (and Cohen’s d effect sizes) and Wilcoxon signed-rank tests (and matched-pairs rank biserial correlation coefficient effect size) for (non)parametric data, respectively, were conducted. In order to answer the second research question, correlation matrix analyses based on ranks were performed. The alpha level was set to p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Example Task-Based Performances

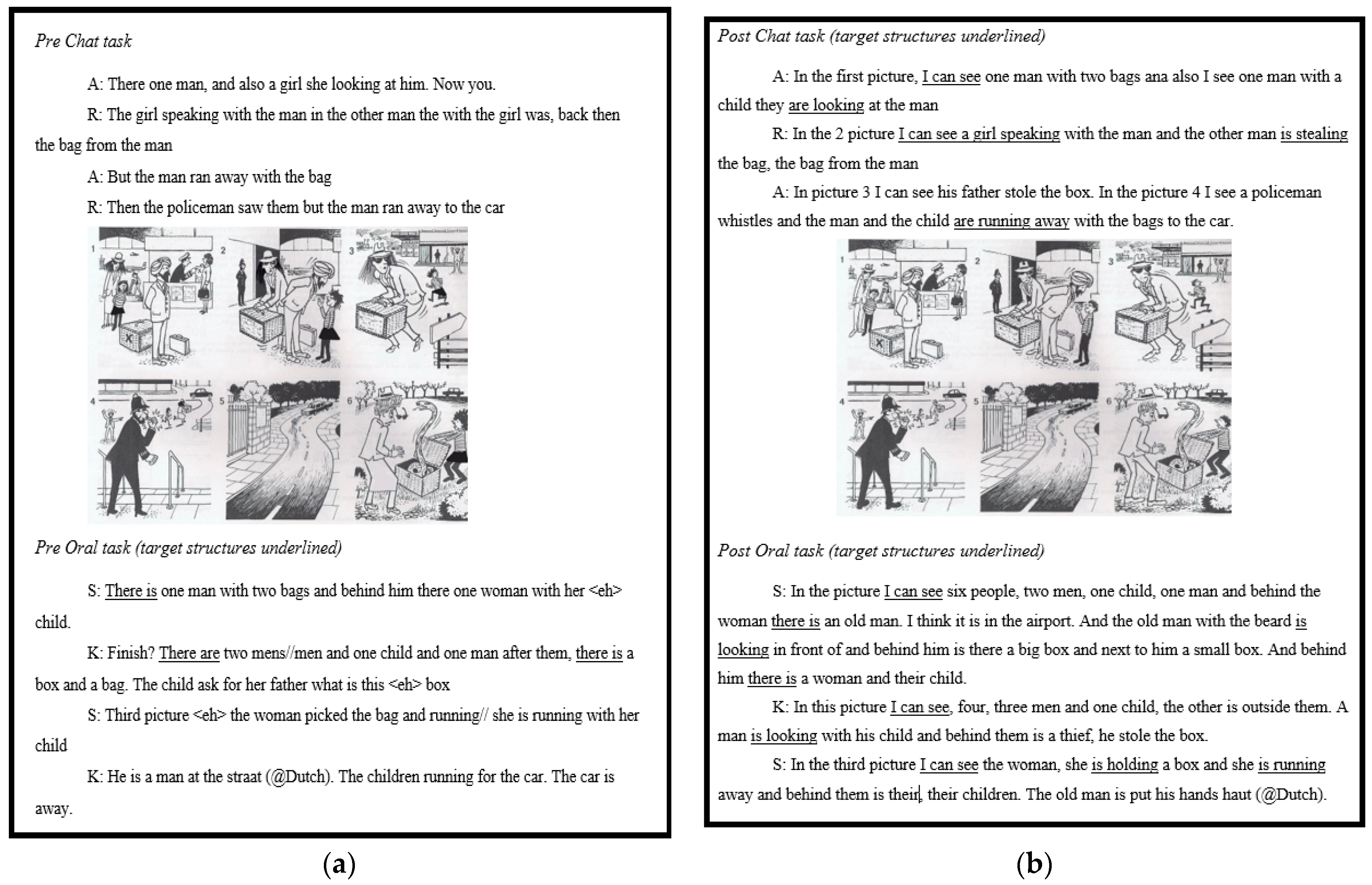

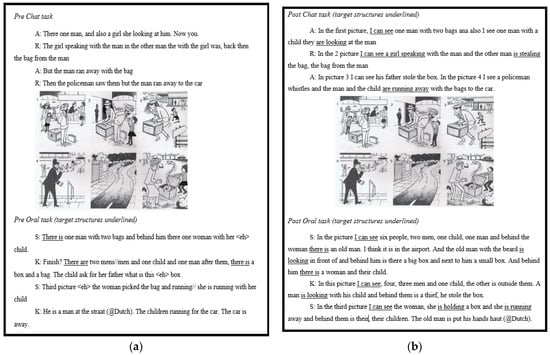

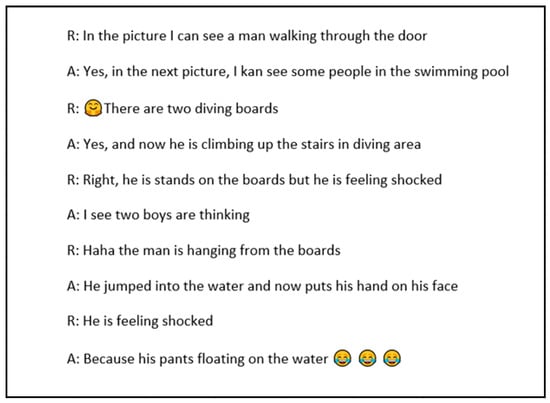

During the time allotted per task, pairs generated around eight turns for chat tasks and ten turns for oral tasks (text chat: pre M = 10.42, SD = 5.65 vs. post M = 6, SD = 1.26; oral: pre M = 11.28, SD = 3.30; post M = 7.57, SD = 2.22), summing up to at a total of 112 vs. 140 turns on text chat vs. oral tasks, respectively, for all participants. Figure 1a,b show four excerpts of chat and oral interactions by two pairs while performing pre-/post-tasks. Initially participants used (a) short, coordinated sentences, labeling main events, that is, creating a weak plot with some attempts to narrative story telling. After the intervention, participants used (b) more complex noun phrases and adjectives, gave more detail with higher accuracy, and, overall, there was a narrative (which was not always complete) structure. This development could be seen in both modalities (oral vs. text chat).

Figure 1.

(a) Examples of pre-test oral and chat task performance, (b) examples of post-test oral and chat task performance.

3.2. Descriptive and Inferential Statistics for Text-Chat and Oral Data on Pre-/Post-Tasks

Descriptive statistics (Table 2) indicate that participants made gains in all fluency, global, and task-specific accuracy, as well as holistic measures in both conditions, with global and task-specific accuracy showing the strongest development.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics on different linguistic measures (N = 15).

Table 3 presents the results of inferential statistics comparing pre- and post-task scores. For text chat, participants scored higher post-task on both fluency measures, which reached significance with a large effect size for the total number of clauses: t(14) = 2.25, p < 0.05, 95% CI [0.079, 3.39], d = 0.84. Participants were also more accurate post-task considering all error rates, with a significant difference and a large effect size for the ratio of total number of errors per 50 words: t(14) = −4.20, p < 0.01, 95% CI [−4.21, −1.37], d = −1.10), and considering two task specific measures, again with large effect sizes: present continuous V(14) = 59, p < 0.05, rrb = 0.83; can + infinitive t(14) = 4.73, p < 0.01, 95% CI [0.98, 2.61], d = 1.53. Differences in functional language use were apparent but non-significant.

Table 3.

Inferential statistics comparing pre- vs. post-task scores on text chat and oral data (N = 15).

A very similar picture was found for oral pre- and post-tasks (cf. Table 4)—yet, while 2nd grade errors were reduced, contrary to expectations, 1st grade errors increased. A significant, medium effect size difference appeared on the average pause length: t(14) = −2.27, p < 0.05, 95% CI [−1.90, −0.048], d = 0.28. For global accuracy, effect sizes of significant differences were medium to large: 1st grade errors t(14) = 2.92, p < 0.01, 95% CI [0.34, 2.03], d = 1.19; 2nd grade errors V(14) = 1.5, p < 0.05, rrb = −0.93; ratio of total number of errors per 50 words t(14) = −4.64, p < 0.01, 95% CI [−2.28, −0.55], d = 1.41. As was the case for task-specific accuracy: present continuous t(14) = 4.25, p < 0.01, 95% CI [0.75, 2.55], d = 1.65; can+ infinitive V(14) = 105, p < 0.01, rrb = 0.97. This time, participants scored significantly higher on post-tasks testing functional language use: V(14) = 78, p < 0.01, rrb = 0.96.

Table 4.

Inferential statistics comparing text chat vs. oral performances on pre- and post-tasks (N = 15).

In Table 4, results of the inferential statistics comparing text chat vs. oral performances on pre- and post-Tasks are presented, indicating that apart from 1st grade errors (V(14) = 0.77, p < 0.01, rrb = 0.90), no differences were present before the intervention. After the task-based lesson series, task-specific accuracy measures demonstrated (significantly and with medium effect sizes, except can + infinitive) that scores for text chat elicited greater accuracy than the oral exchanges, while it was the other way round for functional language use: present continuous: t(14) = −2.40, p < 0.05, 95% CI [−1.59, −0.016, d = 0.79); can + infinitive: V(14) = 0, p < 0.05, rrb = 0.23; FLU, t(14) = −2.28, p < 0.05, 95% CI [−0.83, −0.022], d = −0.51.

3.3. Descriptive Statistics and Correlational Analyses on Motivation, Anxiety and CMC Perceptions

Table 5 summarizes the descriptive statistics and correlational analysis of affective factors, such as motivation and anxiety. Participants generally tended to “agree” with most statements, with intrinsic motivation, instrumental motivation, and international orientation showing specifically high means, while (chat) anxiety yielded the lowest mean scores. In-group variations are apparent, given the standard deviations and the fact that all constructs had min/max scores from 2 to 6, respectively. Correlations reveal that technology use is positively related to the ideal L2 self (95% CI [0.22, 0.88]), to instrumental motivation (95% CI [0.16, 0.86]), and to international orientation (95% CI [0.11, 0.85]), which all correlate strongly with each other. Intensity is positively related to intrinsic motivation and international orientation. None of the correlations with anxiety constructs reached significance.

Table 5.

Descriptive statistics and Spearman correlations on task motivation and anxiety (1 = strongly disagree–6 = strongly agree) for all participants (N = 15).

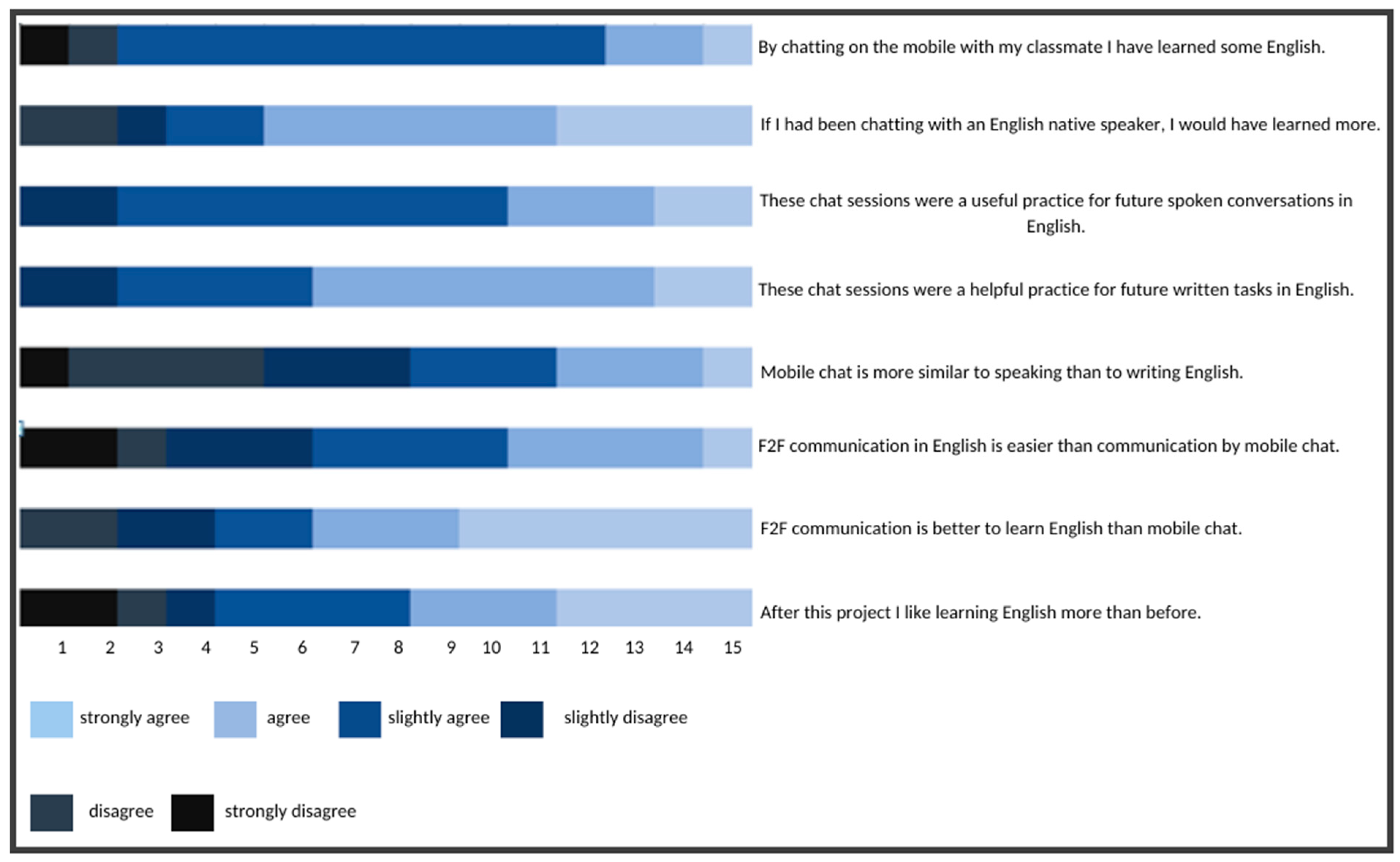

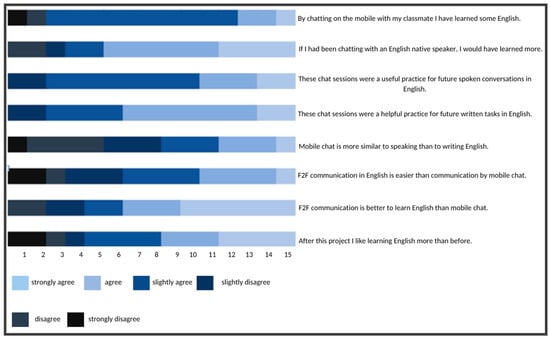

Figure 2 displays the frequency of answers on CMC perceptions. Accordingly, just over half of the participants (n = 8) found that text chat is more similar to writing than speaking, yet most of them (n = 13), perceived written CMC as a useful means for practicing written and oral English. Interestingly, most of them found chatting easier (n = 9) but F2F better for English language learning (n = 11). In general, participants agreed that they had learned some English and held favorable attitudes towards the project. When asked to tick adjectives they associated with CMC, most of them indicated it to be useful (n = 11), important (n = 13), and exciting (n = 8).

Figure 2.

Frequency of rating on task perception questionnaire for all participants (N = 15).

When running Spearman correlations between the motivation and anxiety constructs on the one hand, and CMC perception statements on the other hand, only a few associations were significant, all pertaining to written CMC tasks being helpful for future oral and written communication: motivational intensity, helpful for future writing r = 0.58, p < 0.05, 95% CI [0.09, 0.84]; intrinsic motivation, helpful for future writing r = 0.55, p < 0.05, 95% CI [0.05, 0.83]; motivational intensity, helpful for future spoken r = 0.52, p < 0.05, 95% CI [0.02, 0.82]; intrinsic motivation, helpful for future spoken r = 0.59, p < 0.05, 95% CI [0.10, 0.84]. The perceived helpfulness for future spoken English also yielded strong positive relationships with instrumental motivation (r = 0.55, p < 0.05, 95% CI [0.05, 0.83]) and international orientation (r = 0.55, p < 0.05, 95% CI [0.05, 0.83]).

4. Discussion

Guided by principles of technology-mediated, task-based, and usage-based L2 instruction (East 2021; Smith and González-Lloret 2021; Verspoor 2017), this study set out to examine the effectiveness of written CMC tasks on oral L2 development by taking into account affective variables such as motivation, anxiety, and perceptions of CMC tasks. A series of task cycles, sequenced according to Robinson’s (2015) SSARC model, was implemented into the regular English classes of 15 adolescent refugee learners of English in the Netherlands, and their L2 development was gauged by means of text chat and oral pre- and post-tasks. Questionnaires elicited participants’ levels of motivation, anxiety, and perceptions of the CMC project. In the following, we will discuss our findings.

4.1. The Transfer from L2 Text Chat to Oral Task-Based Performance and Development

The first research question asked whether text chat practice using a SSARC sequence of narrative tasks would have an effect on participants’ L2 oral skills as measured in the present study. Overall, our data revealed that improved performance, that is gains from pre- to post-tasks, were apparent for both written CMC and oral task performances. In both modalities, gains were made in measures of fluency, global and task-specific accuracy, and holistic measures of functional language use, with global and task-specific accuracy showing the strongest development in written CMC, while in the oral mode it was functional language use that was most improved. In short, this study shows that learners who performed a series of increasingly complex text chat tasks produced more fluent, accurate, and meaningful language during follow-up oral interactions. Our data, therefore, confirm that written CMC is a good method of preparation for F2F interactions, and is in line with previous work (e.g., Beauvois 1992, 1997; Blake 2000; Kern 1995).

When zooming in on the different dimensions of task-based performance, some intriguing patterns emerge. For example, raw numbers indicate that participants became more fluent (i.e., produced more words and clauses) in the post-text chat task, which became significant on clauses only. At the same time, participants improved their ability to form grammatically correct sentences after the SSARC instruction. While the participants produced enough words in both pre-and post-tasks, before the intervention, the morphosyntactic organization of these words (e.g., word order) was insufficient for forming clauses. In other words, these fluency gains in written CMC are closely related to gains in accuracy, which is in line with a view that linguistic subsystems dynamically interact with each other during developmental trajectories (Spoelman and Verspoor 2010). This interaction with accuracy might also be the reason why the speaking rate was not affected by the text chat intervention. Skehan (2009) argues that there are trade-offs between different dimensions of task-based performance, in particular, on highly complex tasks. Future work looking into how the different dimensions interact will shed new light on these theories.

However, our data did show gains in speaking fluency reflected in reduced pause length. This finding indicates that the SSARC-based written CMC instruction might have served as practice for lexical and grammatical retrieval, adding to the automatization of some of these processes (Levelt 1989; Robinson 2010), and thus allowing for more fluent speech with fewer hesitations (Blake 2009; Payne and Whitney 2002). That is, even though the participants were not interacting in the spoken mode during the instructional treatment, they were engaging in a form of real-time communication using mobile messenger, which, like spoken interaction, required effective access to their lexicogrammatical system, resulting in the development of oral proficiency.

Another reason for less hesitant speech might be related to affective factors and perceived gains in CMC tasks (e.g., Chun 1994). Most students agreed that the CMC tasks were a useful practice for future spoken conversations. It might be that this perceived growth boosted their self-confidence and sense of accomplishment, which helped in decreasing hesitation when speaking, thus breaking the vicious circle of helplessness as explained by Compton (2002).

In terms of accuracy, both modalities showed significant gains from pre- to post-tasks. Raw numbers show fairly similar scores and gains of 25 to 50%, as confirmed by the existence of no significant differences between the two contexts at pre- and post-task stages. When taking task-specific accuracy into account, both modalities showed exceptional growth in accurate target structure use, specifically present continuous and can + infinitive. The only exception is an increased number of minor mistakes (1st grade errors, e.g., article omission) in oral narratives. Again, an interactional trade-off with greater fluency in the conversations, which did not allow speakers to properly pre-plan their messages, might have induced such mistakes in this group of low-level L2 learners (Chapelle 2009; Yuan and Ellis 2003). The fact that text chat provides learners with time to frame their ideas and modify their output before hitting the enter key might have limited such mistakes in the written CMC environment (Beauvois 1997; Kern 1995; Michel 2018; Satar and Özdener 2008). In general, the saliency and permanence of text chat (e.g., Abrams 2003; Blake 2009; Chun 1994; Kelm 1992) was something that the students highlighted in follow-up interviews: they perceived text chat as easier and less stressful than spoken exchanges.

Finally, the exceptional growth in functional language use in the oral mode could be explained by tapping into post-task questionnaire data as well as learner statements. The majority of students perceived oral communication as a better tool for learning than mobile chat, and they explicitly stated their preference for F2F interaction. This increased motivation might have induced students to devote more cognitive effort to the oral interaction (e.g., Dörnyei 2003; Gardner 1985), which led to higher levels of performance in terms of structure and task fulfillment. Overall, results on all measures provide strong evidence that written CMC promotes L2 development in oral interaction and support earlier work along these lines (e.g., Blake 2009; Payne and Whitney 2002). Given that the fluency and accuracy gains made in the two conditions were similar, which provides further support for the transferability of skills between the two modes, confirming that chat practice could be a useful stepping stone for L2 oral development.

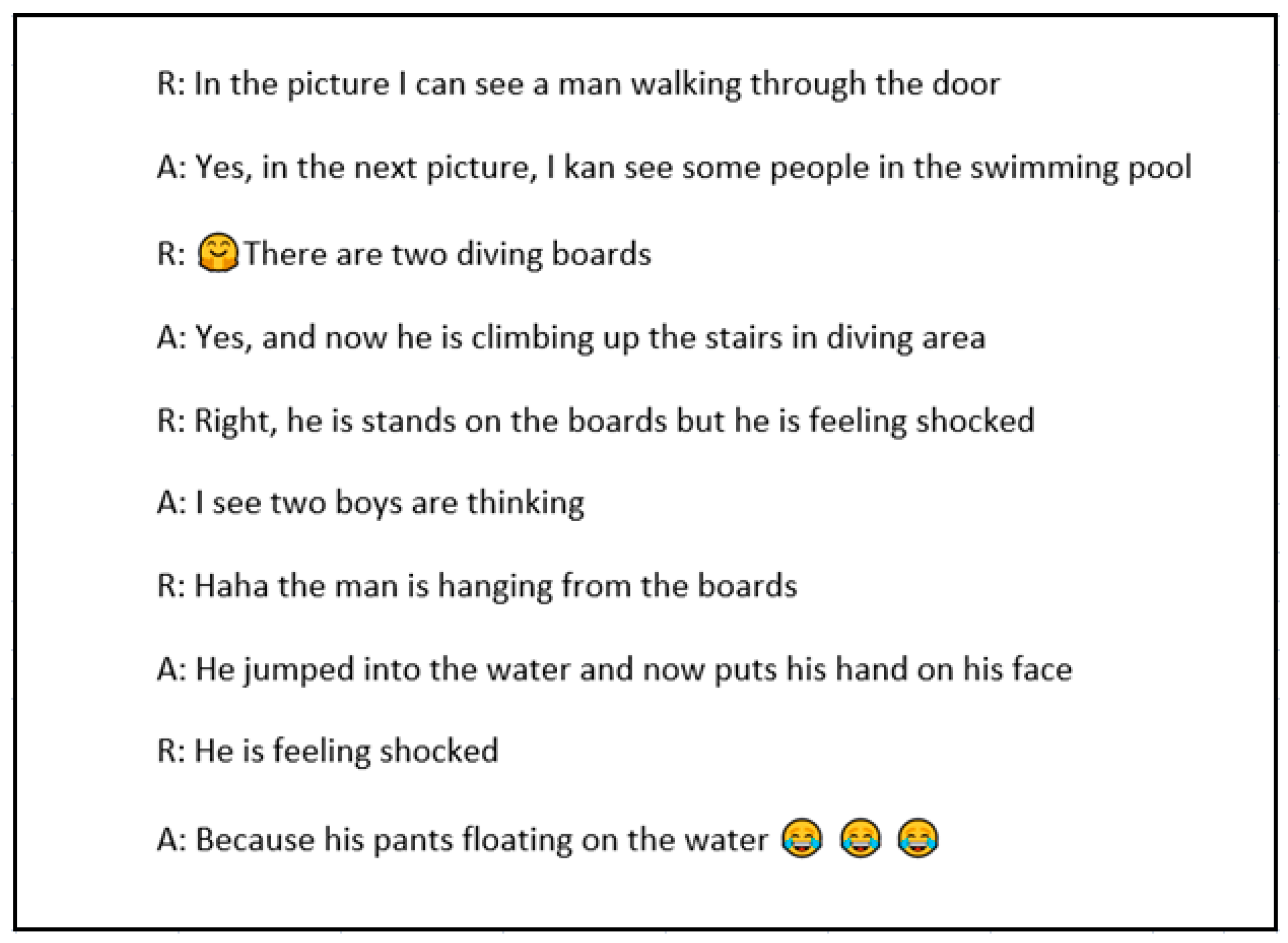

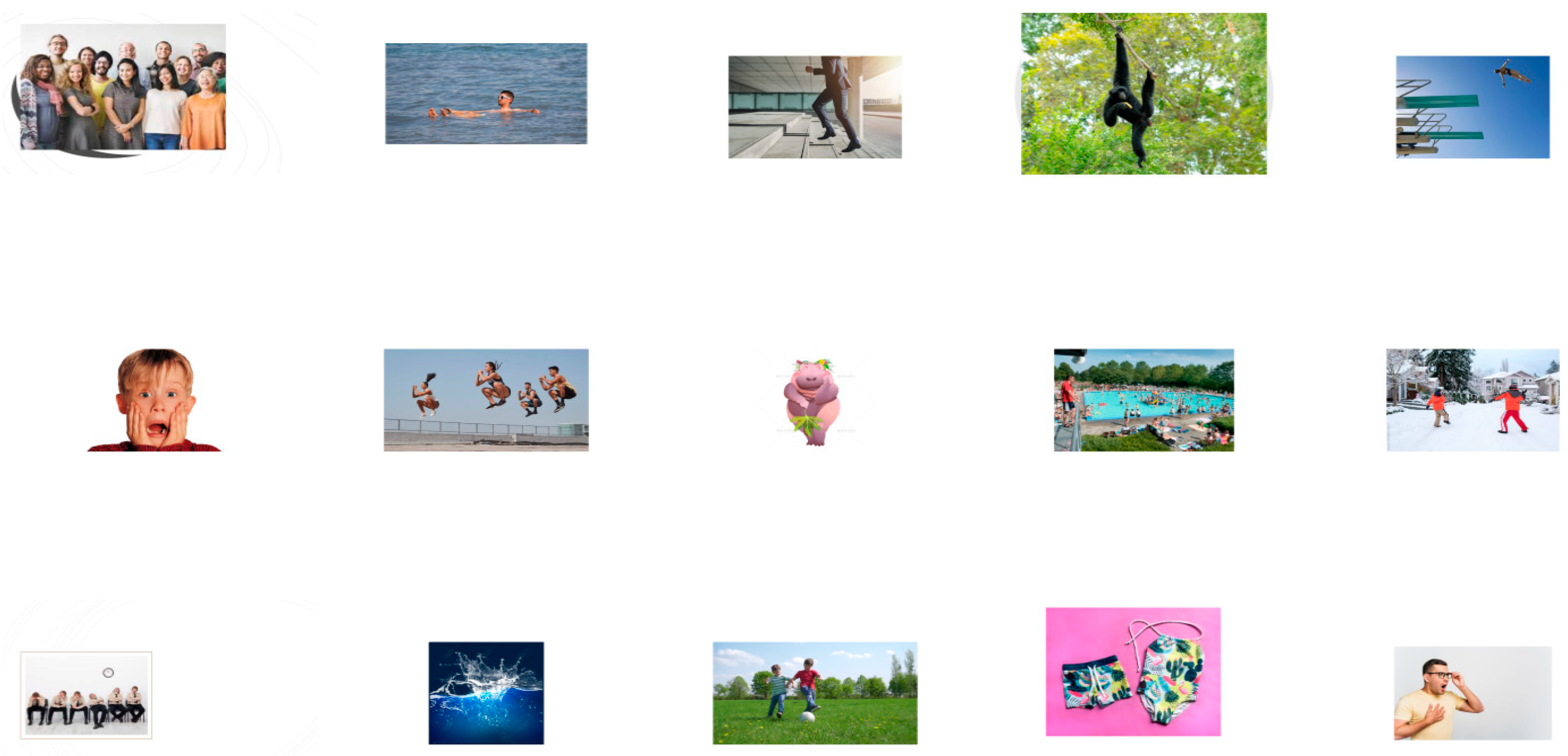

4.2. Written CMC Treatment Task Design: Task Complexity and Sequencing

It is likely that our results on fluency, functional language use, and the major findings in task-specific accuracy are related to our task design and our choice of target structures. Following Robinson’s (2001) Cognition Hypothesis and his SSARC model of task sequencing (Robinson 2010), treatment tasks were designed such that they allowed for meaningful peer interaction, while at the same time promoting development through practice and steady increases in task complexity. Tasks were aligned with the students’ curriculum and needs, as, for example, the target structures were expected to be known for their official oral exams at school. Our intervention implemented these structures implicitly through pre-task activities, modeled use, and guided practice during task performance based on material that was seeded with these structures—at no time was explicit instruction of the target structures provided. When reviewing the chat logs of task-based performances, it is clear that students did pick up and practice the target structures (cf. Figure 3), which most likely resulted in the L2 development apparent in our data.

Figure 3.

Example of a chat log for treatment task 1.

Similarly, the repetitive nature of the task structure, using similar features in combination with increasing task complexity from task 1 to task 3, allowed for cumulative learning, stabilizing, automatizing, restructuring, and, finally, complexifying the interlanguage system, as predicted by the SSARC model (Robinson 2010). Consequently, most of the participants employed at least two of the target structures in their post-task interactions. Written CMC activities allow all students to practice English simultaneously, which is different from oral class discussions, where typically only a handful of students take a turn (Blake 2009; Payne and Ross 2005). Moreover, Van de Guchte et al. (2019) have shown that students remain in the target language during text chat interactions without returning to their joint native language, which often happens in oral interactions. As such, the task-based text chat performances increased the amount of input, output and interaction that, most likely, was beneficial for the participants’ linguistic development (Chapelle 2009; Loewen and Sato 2018). To conclude, all of these aspects together created an optimal environment for L2 development, which pushed not only written CMC interaction but also led to more fluent, accurate, and functional use of spoken language.

4.3. Language Learning Motivation, Anxiety and Task Perception

The second research question was concerned with how the text chat intervention related to learners’ motivation, anxiety, and perceived use of these written CMC activities. Overall, students showed medium to high motivation, medium to low (chat) anxiety, and relatively high appreciation of the chat task project.

The strong and significant correlations between the usefulness of written CMC for future written and oral interactions and motivational constructs give rise to some of the following possible explanations. Our data suggest that students who are motivated to learn, and are career as well as internationally oriented, appreciate the technology-mediated tasks more, as they evaluate them as useful for achieving their goals. Future work could collect additional individual difference data to see how different mindsets, orientations, and preferences would relate to text chat perceptions (Baralt and Gurzynski-Weiss 2011).

Interestingly, while most participants in the follow-up interview stated that chatting in English causes less anxiety than speaking, their data from the SCMC task perception questionnaire did not correlate either with either (chat) anxiety measure. As such, anxiety seems not to have played an important role in their appreciation of the CMC project—a finding that is inconsistent with the previous work by Michel (2018). In that study, however, participants were younger and used Skype to chat with each other on a computer. It might be that the more authentic context of the current study (using text chat on a mobile device) plus the fact that our participants were very familiar with technology use and explicitly stated that chatting is easier than speaking, and causes less anxiety, induced our findings. It could also well be the novelty of using written CMC for formal instruction that influenced our data (Baralt and Gurzynski-Weiss 2011; Gurzynski-Weiss and Baralt 2014). Future studies could utilize additional methods, such as stimulated recall, to triangulate data and provide additional insights on anxiety and text chat practice.

Finally, the more qualitative data revealing students’ perceptions of the CMC activities indicate that the adolescent L2 learners held positive attitudes towards using text chat in class—a finding that was reiterated by their teacher. As such, teachers may well employ text chat as a means of learning into their regular practice.

5. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

At this point, we would like to highlight four important limitations of our study. First, the present study was implemented during the COVID pandemic, which means that there were only a small number of participants, and no control group was used. Consequently, the SSARC model was employed for all participants and no alternative intervention could be implemented. Such methodological issues limit the generalizability of our conclusions. Second, the fact that the instructional treatment was implemented by the researcher might affect students’ performance and overall behavior. In order to improve ecological validity, it is suggested for FL teachers to implement any future experiments in their own regular classrooms. Third, the absence of a delayed post-test does not allow us to evaluate any long-term effects of chat practice on oral development. Finally, the design features of the narrative task restrict its generalizability to other task types. Narrative tasks do not create a need to communicate with classmates per se, because there is no information gap. A potentially interesting future area of investigation could be the examination of L2 oral development in relation to different written CMC tasks with different task features or different task types, as we know that task design has substantial effects on learning outcomes. (e.g., Ellis 2003; Robinson and Gilabert 2007; Smith and González-Lloret 2021).

As such, there remains enough work to be done in the future to generate more insights into how different task types, different task designs, and implementations affect task-based performance and the transferability from text chat to oral interaction. Introspective methodologies (e.g., stimulated recall) could help us understand how the written CMC context influences the learning process, how learners might notice L2 features, and how motivation and anxiety might mediate these processes (Baralt and Gurzynski-Weiss 2011).

6. Conclusions and Pedagogical Implications

The present study investigated whether written CMC practice through a series of interactive narrative tasks, designed following the SSARC model (Robinson 2010), influences L2 oral development by transferring skills across modalities. It also explored the relationship between language learning motivation, anxiety, and perceptions of the CMC tasks. Given the context of our study, where the intervention and data collection were fully integrated in an ongoing language class, we can allow ourselves to formulate some pedagogical implications alongside some theoretical conclusions. First, although the sample size is too small and some other, previously described limitations restrict our ability to draw firm conclusions, the findings of the present study provide convincing evidence that text-based CMC can be an effective means by which to improve oral skills. When guided by theoretically informed language learning tasks, text chat can be a helpful teaching tool, either for additional practice (e.g., when there is insufficient class time to practice speaking), or as part of an online course. Our data suggest that interacting via chat helps students not only to speak more, but also to make fewer mistakes. More specifically, we provide evidence that a direct transfer of language experiences across modalities does occur, which suggests that the cognitive mechanisms that apply to oral interaction are very likely also used in chat production (Blake 2009; Payne and Whitney 2002). Given that text chat gives learners some time to think and implement newly learned language, a straightforward pedagogical implication is that written CMC is an important classroom tool that teachers should not be shy to use.

Additionally, this study shed some light on students’ perceptions regarding the use of text chat in the FL classroom. Written CMC was seen as a safe, engaging, and motivating learning environment for L2 practice. Based on the body of work showing that motivation helps learning, another pedagogical implication of our study is that text chat can be implemented in the language classroom for motivational reasons. However, it is important to reiterate that the use of text chat should be carefully considered in relation to divergent groups of learners and their preferences (Smith and González-Lloret 2021).

Even though this was not a research question, the classroom-based implementation of our study allows us to shed some light on the principles we have used to design the intervention lessons. The task-based lesson series was built on Robinson’s (2010) SSARC model and, as such, elicited the repeated use of the same structures across a variety of tasks (e.g., model video of advanced learners demonstrating successful task performance; vocabulary tasks; task and procedural repetition) with growing performative and cognitive complexity. It seems that performing these text chat tasks boosted students’ confidence to actually speak while using and consequently acquiring a new linguistic repertoire. A final pedagogical implication, therefore, is that it seems to be a valuable practice to sequence tasks according to task complexity and the SSARC model.

To summarize, based on our study, we do conclude that written CMC is a useful practice for oral development, and is valued by learners, which, therefore, creates a favorable environment for L2 practice and development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.K.; methodology, E.K.; formal analysis, E.K.; investigation, E.K.; resources, E.K.; data curation, E.K.; writing—original draft preparation, E.K.; writing—review and editing, M.M.; visualization, E.K.; supervision, M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the MA of Applied Linguistics, Groningen University, Faculty of Arts.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data cannot be shared due to privacy reasons.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Vocabulary Worksheet Example

Task 1: Vocabulary Worksheet

You will see 16 pictures on a PowerPoint presentation.

Read the sentences and find the correct phrase for each picture.

If you know the answer, raise your hand!

- In the picture, I can see a swimming pool

- They are playing with the ball

- In the picture I can see some children

- In the middle of the picture, I can see a group of people

- There are two bathing suits

- He is climbing up the stairs

- There are two diving boards

- The young boy is feeling afraid

- He is feeling shocked

- He is tired to wait

- In the picture, I can see a water splash

- In the picture, I can see a naked hippopotamus

- They are jumping

- They are throwing snowballs at each other

- The orangutan is hanging from the tree

- The man is floating on the water

Figure A1.

Screenshot of the pictures used in the PowerPoint presentation for the task 1 vocabulary activity.

Figure A1.

Screenshot of the pictures used in the PowerPoint presentation for the task 1 vocabulary activity.

- MAIN Treatment task 1

- You and your partner each have 10 frames/pictures.

- These pictures together tell a story of Mr. Bean.

- Each picture has a number. This number indicates the order of the pictures.

- Look at your pictures carefully and take a few moments (3 min) to think before you start chatting with your partner. Read the useful words and phrases!

- Chat with your partner, describe the pictures in the right order, use the useful words and phrases! Try to understand the story!

- You will describe all that you can see in the picture (the place, the people and the objects) and explain what you think is happening and how the people are feeling: What is in the picture? Where in the picture? What is happening in the picture?

- Try your best, describe the details, and tell the story! You have 10 min!

| 1 |  | 2 |  |

| 3 |  | 4 |  |

| 5 |  | 6 |  |

| 7 |  | 8 |  |

| 9 |  | 10 |  |

- Useful words and phrases for description of pictures:

- What is in the picture?

- In the picture I can see ...

- There is/There are ...

- There isn’t a ...

- Say what is happening with the present continuous

- The man/woman is ...ing

- Where in the picture?

- At the top/bottom of the picture ...

- In the middle of the picture ...

- On the left/right of the picture ...

- next to

- in front of

- behind

- near

- on top of

- under

- If something isn’t clear

- It looks like a ...

- Maybe it’s a ...

- Examples of linking words

- …because…, and, then, after that, before, but

- How to ask if you don’t understand

- I am sorry, I didn’t understand. Is the man/woman … ing?/are the people … ing?

- What do you mean by …? Maybe you want to say…?

- Could you please repeat?

Appendix B. Language Motivation and Anxiety Questionnaire (Plus 6 Statements Targeting Chat Anxiety and Technology Use) with a 7-Point Likert Scale Answer Options from ‘Strongly Disagree’ to ‘Strongly Agree’

- I would feel uneasy speaking English with/to a person who spoke that language.

- I use English language-teaching computer programs.

- I feel more tense and nervous in my language class than in my other classes.

- I often use the Internet to practice English.

- I get nervous when I’m speaking in my English class.

- I often chat in English on the Internet.

- My friends think English is cool.

- I’m afraid that other students will laugh at me when I speak English.

- People around me tend to think that it’s a good thing to know foreign languages.

- When I chat on the computer in English I am afraid that my chat partner finds me stupid when I make mistakes.

- My friends think that studying English is important.

- I feel embarrassed to write in English during a computer chat session at school.

- I put off my English homework as much as possible

- My friends are not bothered to study English.

- When I study English, I seldom do more than is necessary.

- I study English because I’d really like to be good at it.

- I find that learning English is really interesting.

- I’m ready to work hard to learn English.

- I am happy when I see that I am making progress in English.

- I study English because it will be necessary to work in English speaking countries.

- I keep up to date with English by working on it almost every day.

- Learning English is really great.

- I would feel uncomfortable using computer chat in English with/to a person who spoke that language.

- I can imagine myself reading books and magazines in English.

- When I imagine my future job, I see myself using English.

- Learning English is necessary because it is an international language.

- Studying English will help me feel part of the international community of people speaking English.

- I can imagine myself speaking English with high proficiency.

- I can imagine myself writing emails in English.

- I study English because I would like to spend some time abroad.

- I study English as it is necessary to pass my exams.

- The things I want to do in the future require that I speak English.

- I need English for my future career.

- I would really like to communicate with English speakers in the future.

Table A1.

Internal reliability of language motivation and anxiety constructs.

Table A1.

Internal reliability of language motivation and anxiety constructs.

| Construct | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|

| 1. Technology use (2, 4, 6) | 0.712 |

| 2. Chat anxiety (10, 12, 23) | 0.703 |

| 3. Anxiety (1, 3, 5, 8) | 0.712 |

| 4. Motivational intensity (15, 18, 21) | 0.724 |

| 5. Intrinsic motivation (16, 17, 19, 22) | 0.756 |

| 6. Ideal L2 Self (24, 25, 29) | 0.801 |

| 7. Instrumental motivation (31, 32, 33) | 0.707 |

| 8. International orientation (20, 26, 27, 34) | 0.716 |

Appendix C. Questionnaire Items on Task Perception with a 7-Point Likert Scale Answer Options from ‘Strongly Disagree’ to ‘Strongly Agree’

- By chatting on the mobile with my classmate I have learned some English.

- If I had been chatting with an English native speaker, I would have learned more.

- These chat sessions were a useful practice for future spoken conversations in English.

- These chat sessions were a helpful practice for future written tasks in English.

- Mobile chat is more similar to speaking than to writing English.

- Face-to-face communication in English is easier than communication by mobile chat.

- Face-to-face communication is better to learn English than mobile chat.

Appendix D. Holistic Rating Scale Guidelines to Global Evaluation of Language Performance

The language output is assessed on a score out of 5. This score evaluates the language output mainly in terms of structure and task fulfillment. In order to fulfill the task, the product needs to include the description of the main elements that appear on the pictures, and the narration of what happens should also be clear.

- Score 5: This is a very good result. The output is well structured. It contains a clear and complete description of the pictures and the narration of the story is logical. Ideas are clearly organized, and good use is made of linking words/phrases.

- Score 4: This is a good result. The output has a clear overall structure. All pictures are described, and the narration of the story is easy to follow most of the time. Ideas are generally well organized and linking words/phrases are generally used appropriately.

- Score3: This is a satisfactory result. It has an overall structure, but the description of some pictures may be incomplete, and the narration of the story hard to follow. Linking words/phrases may be missing or used inappropriately.

- Score 2: This is an adequate result. It is difficult to follow because the description is very incomplete, and the narration is not well organized. There is a general lack of linking words/phrases. There might be repetitions.

- Score 1: This is a poor result. It is poorly organized and difficult to follow. Description and narration are poor or absent.

Notes

| 1 | Throughout this paper, we will use the terms ‘text chat’ and ‘written CMC’ (rather than SCMC, which stands for synchronous CMC) to refer to the medium widely used in modern digital communication by means of messenger services such as WhatsApp or WeChat, given that it is no longer used in synchronous modes only (cf. Smith and González-Lloret 2021). |

| 2 | We highlight here the specific background of our participants even though this is not related to our research questions. The interested reader is referred to Gok and Michel (2021) where we shed more light on tasks for highly educated refugees in the Netherlands. |

References

- Abrams, Zsuzsanna. 2001. Computer-mediated communication and group journals: Expanding the repertoire of participant roles. System 29: 489–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrams, Zsuzsanna. 2003. The effect of synchronous and asynchronous CMC on oral performance in German. The Modern Language Journal 87: 157–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baralt, Melissa, and Laura Gurzynski-Weiss. 2011. Comparing learners’ state anxiety during task-based interaction in computer-mediated and face-to-face communication. Language Teaching Research 15: 201–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baralt, Melissa, Roger Gilabert, and Peter Robinson, eds. 2014. Task Sequencing and Instructed Second Language Learning. London: A&C Black. [Google Scholar]

- Beauvois, Margaret-Heily. 1992. Computer-assisted classroom discussion in the foreign language classroom: Conversation in slow motion. Foreign Language Annals 25: 455–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauvois, Margaret-Heily. 1997. Write to speak: The effects of electronic communication on the oral achievement of fourth semester French students. In New Ways of Learning and Teaching: Issues in Language Program Direction. Edited by Judith Muyskens. Boston: Heinle & Heinle Publishers, pp. 93–116. [Google Scholar]

- Blake, Christopher. 2009. Potential of text-based internet chats for improving oral fluency in a second language. The Modern Language Journal 93: 227–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, Christopher. 2017. Technologies for teaching and learning L2 speaking. In The Handbook of Technology and Second Language Teaching and Learning. Edited by Carol A. Chapelle and Shannon Sauro. New York: John Wiley & Sons Inc., pp. 107–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, Robert. 2000. Computer-mediated communication: A window on FL Spanish interlanguage. Language Learning & Technology 4: 120–36. [Google Scholar]

- Bygate, Martin. 2001. Effects of Task Repetition on the Structure and Control of Oral Language. In Researching Pedagogic Tasks Second Language Learning, Teaching and Testing. Edited by Martin Bygate, Peter Skehan and Merrill Swain. Upper Saddle River: Pearson Education, pp. 23–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapelle, Carol A. 2009. The relationship between second language acquisition theory and computer-assisted language learning. The Modern Language Journal 93: 741–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, Dorothy M. 1994. Using computer networking to facilitate acquisition of interactive competence. System 22: 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compton, Lily. 2002. From Chatting to Confidence: A Case Study of the Impact of Online Chatting on International Teaching Assistants’ Willingness to Communicate, Confidence Level and Fluency in Oral Communication. Unpublished. Master’s thesis, Department of English, Iowa State University, Ames, IA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Darhower, Mark. 2002. Interactional features of synchronous computer-mediated communication in the intermediate L2 class: A sociocultural case study. CALICO 19: 249–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bot, Kees W., Wander Lowie, and Marjolijn Verspoor. 2005. Second Language Acquisition: An Advanced Resource Book. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- de Bot, Kees W., Wander Lowie, and Marjolijn Verspoor. 2007. A Dynamic Systems Theory approach to second language acquisition. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 10: 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dörnyei, Zoltán. 2001. New Themes and Approaches in Second Language Motivation Research. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics 21: 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dörnyei, Zoltán. 2003. Attitudes, orientations, and motivations in language learning: Advances in theory, research, and applications. Language Learning 53: 3–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dussias, Paola. 2006. Morphological development in Spanish-American telecollaboration. In Internet-Mediated Intercultural Foreign Language Education. Edited by Julie A. Belz and Steve L. Thorne. Boston: Thomson Heinle, pp. 121–46. [Google Scholar]

- East, Martin. 2021. Foundational Principles of Task-Based Language Teaching. London: Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, Rod. 2003. Task-Based Language Learning and Teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, Pauline, and Gillian Wigglesworth. 2016. Capturing accuracy in second language performance: The case for a weighted clause ratio. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics 36: 98–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, Robert C. 1985. Social Psychology and Second Language Learning: The Role of Attitudes and Motivation. London: Arnold. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gok, Seyit, and Marije Michel. 2021. Designing pedagogic tasks for refugees learning English to enter universities in the Netherlands. In The Cambridge Handbook of Task-Based Language Teaching. Edited by Mohammad Javad Ahmadian and Michael Long. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 290–302. [Google Scholar]

- González-Lloret, Marta, and Lourdes Ortega, eds. 2014. Technology-Mediated TBLT: Researching Technology and Tasks. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, vol. 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurzynski-Weiss, Laura, and Melissa Baralt. 2014. Exploring learner perception and use of task-based interactional feedback in FTF and CMC modes. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 36: 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heaton, John Brian. 1975. Beginning Composition through Pictures. London: Longman Group Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Ito, Mizuko, Heather A. Horst, Matteo Bittanti, Danah Boyd, Becky Herr-Stephenson, Patricia C. Lange, C.J. Pascoe, and Laura Robinson. 2008. Living and Learning with New Media: Summary of Findings from the Digital Youth Project. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelm, Orlando. 1992. The use of synchronous computer networks in second language instruction: A preliminary report. Foreign Language Annals 25: 441–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, Richard. 1995. Restructuring classroom interaction with networked computers: Effects on quantity and characteristics of language production. The Modern Language Journal 79: 457–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kormos, Judit, and Mariann Denes. 2004. Exploring measures and perceptions of fluency in the speech of second language learners. System 32: 145–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kormos, Judit, Tineke Brunfaut, and Marije Michel. 2020. Motivational factors in computer-administered integrated skills tasks: A study of young learners. Language Assessment Quarterly 17: 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kormos, Judit, Thom Kiddle, and Kata Csizér. 2011. Goals, attitudes and self-related beliefs in second language learning motivation: An interactive model of language learning motivation. Applied Linguistics 32: 495–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuiken, Folkert, and Ineke Vedder. 2008. Cognitive task complexity and written output in Italian and French as a foreign language. Journal of Second Language Writing 17: 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuiken, Folkert, Ineke Vedder, and Roger Gilabert. 2010. Communicative adequacy and linguistic complexity in L2 writing. In Communicative Proficiency and Linguistic Development: Intersections between SLA and Language Testing Research. Edited by Inge Bartning, Maisa Martin and Ineke Vedder. EuroSLA Monographs Series 1; Amsterdam: EuroSLA, pp. 81–100. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, Chun, and Yong Zhao. 2006. Noticing and text-based chat. Language Learning and Technology 10: 102–20. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert, Craig, and Peter Robinson. 2014. Learning to perform narrative tasks: A semester-long classroom study of L2 task sequencing effects. In Task Sequencing and Instructed Second Language Learning. Edited by Melissa Baralt, Roger Gilabert and Peter Robinson. London: Bloomsbury, pp. 207–30. [Google Scholar]

- Levelt, Willem. 1989. Speaking: From Intention to Articulation. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Wei-Chen, Hung-Tzu Huang, and Hsien-Chin Liou. 2013. The effects of text-based SCMC on SLA: A meta-analysis. Language Learning & Technology 17: 123–42. [Google Scholar]

- Loewen, Shawn, and Masatoshi Sato. 2018. Interaction and instructed second language acquisition. Language Teaching 51: 285–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowie, Wander, Marije Michel, Audrey Rousse-Malpat, Merel Keijzer, and Rasmus Steinkrauss, eds. 2020. Usage-Based Dynamics in Second Language Development. Cleveldon: Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Manchón, Rosa. 2011. Writing to learn the language: Issues in theory and research. Learning-to-Write and Writing-to Learn in an Additional Language 61: 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, Marije. 2017. Complexity, accuracy and fluency in L2 production. In Routledge Handbook of Instructed Second Language Acquisition. Edited by Shawn Loewen and Masatoshi Sato. (Routledge Handbooks in Applied Linguistics). London: Routledge, pp. 50–68. [Google Scholar]

- Michel, Marije. 2018. Practicing online with your peers: The role of text chat for second language development. In Practice in Second Language Learning. Edited by Cristian Jones. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 164–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocando Finol, Maria. 2019. Past the Anthropocentric: Sociocognitive Perspectives for Tech-Mediated Language Learning. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics 39: 146–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, Lourdes. 1997. Processes and outcomes in networked classroom interaction: Defining the research agenda for FL computer-assisted classroom discussion. Language Learning and Technology 1: 82–93. [Google Scholar]

- Oxford, Rebecca L., and Judith Burry-Stock. 1995. Assessing language learning strategies worldwide with the ESL/EFL version of the strategy inventory for language learning (SILL). System 23: 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, Scott J., and Brenda M. Ross. 2005. Synchronous CMC, working memory, and L2 oral proficiency development. Language Learning and Technology 9: 35–54. [Google Scholar]

- Payne, Scott J., and Paul J. Whitney. 2002. Developing L2 oral proficiency through synchronous CMC: Output, working memory, and interlanguage development. CALICO Journal 20: 7–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelletieri, Jill. 2000. Negotiation in cyberspace: The role of chatting in the development of grammatical competence. In Network Based Language Teaching: Concepts and Practice. Edited by Mark Warschauer and Richard Kern. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 59–86. [Google Scholar]

- Razagifard, Parisa. 2013. The impact of text-based CMC on improving L2 oral fluency. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning 29: 270–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Révész, Andrea, Marije Michel, and Roger Gilabert. 2016. Measuring cognitive task demands using dual task methodology, subjective self-ratings, and expert judgments: A Validation Study. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 38: 703–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, Peter. 2001. Task complexity, task difficulty and task production: Exploring interactions in a componential framework. Applied Linguistics 22: 27–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, Peter. 2005. Cognitive complexity and task sequencing: Studies in a componential framework for second language task design. International Review of Applied Linguistics 43: 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, Peter, ed. 2010. Second Language Task Complexity: Researching the Cognition Hypothesis of Language Learning and Performance. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, Peter. 2015. The Cognition Hypothesis, second language task demands, and the SSARC model of pedagogic task sequencing. In Domains and Directions in the Development of TBLT: Plenaries from a Decade of the International Conference. Edited by Martin Bygate. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp. 87–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, Peter, and Roger Gilabert. 2007. Task complexity, the cognition hypothesis and second language learning and performance. International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching 45: 161–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousse-Malpat, Audrey, Rasmus Steinkrauss, Martjin Wieling, and Marjolijn Verspoor. 2022. Communicative language teaching: Structure-Based or Dynamic Usage-Based? Journal of the European Second Language Association 6: 20–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuda, Virginia, and Martin Bygate. 2008. Tasks in Second Language Learning. New York: Palgrave. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satar, Muge, and Nesrin Özdener. 2008. The effects of synchronous CMC on speaking proficiency and anxiety: Text versus voice chat. The Modern Language Journal 92: 595–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauro, Shannon. 2011. SCMC for SLA: A research synthesis. CALICO Journal 28: 369–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauro, Shannon, and Bryan Smith. 2010. Investigating L2 performance in text chat. Applied linguistics 31: 554–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scovel, Thomas. 1978. The effect of affect on foreign language learning: A review of the anxiety research. Language Learning 28: 129–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skehan, Peter. 2009. Modeling second language performance: Integrating complexity, accuracy, fluency, and lexis. Applied Linguistics 30: 510–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skehan, Peter, and Pauline Foster. 2001. Cognition and Tasks. In Cognition and Second Language Instruction. Edited by Peter Robinson. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 183–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Bryan, and Marta González-Lloret. 2021. Technology-Mediated Task-Based Language Teaching: A Research Agenda. Language Teaching 54: 518–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Karen L. 1990. Collaborative and interactive writing for increasing communication skills. Hispania 73: 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spoelman, Marianne, and Marjolijn Verspoor. 2010. Dynamic patterns in development of accuracy and complexity: A longitudinal case study in the acquisition of Finnish. Applied Linguistics 31: 532–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storch, Neomy. 2005. Collaborative writing: Product, process, and students’ reflections. Journal of Second Language Writing 14: 153–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, Andrea E. L., Lourdes Ortega, Mariko Uno, and Hae In Park, eds. 2018. Usage-Inspired L2 Instruction: Researched Pedagogy. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, vol. 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Guchte, Marrit C., Gert Rijlaarsdam, Martine Braaksma, and Peter Bimmel. 2019. Focus on language versus content in the pre task: Effects of guided peer-video model observations on task performance. Language Teaching Research 23: 310–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verspoor, Marjolijn. 2017. Complex dynamic systems theory and L2 pedagogy. In Complexity Theory and Language Development: In Celebration of Diane Larsen-Freeman. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp. 143–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, Jane. 1996. A Framework for Task-Based Learning. Harlow: Longman, vol. 60. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe-Quintero, Kate S., Shunji Inagaki, and Hae-Young Kim. 1998. Second Language Development in Writing: Measures of Fluency. In Accuracy, and Complexity. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Fangyuan, and Rod Ellis. 2003. The Effects of Pre-Task Planning and On-Line Planning on Fluency, Complexity and Accuracy in L2 Monologic Oral Production. Applied Linguistics 24: 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, Nicole. 2016. Taking technology to task: Technology-mediated TBLT, performance, and production. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics 36: 136–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).