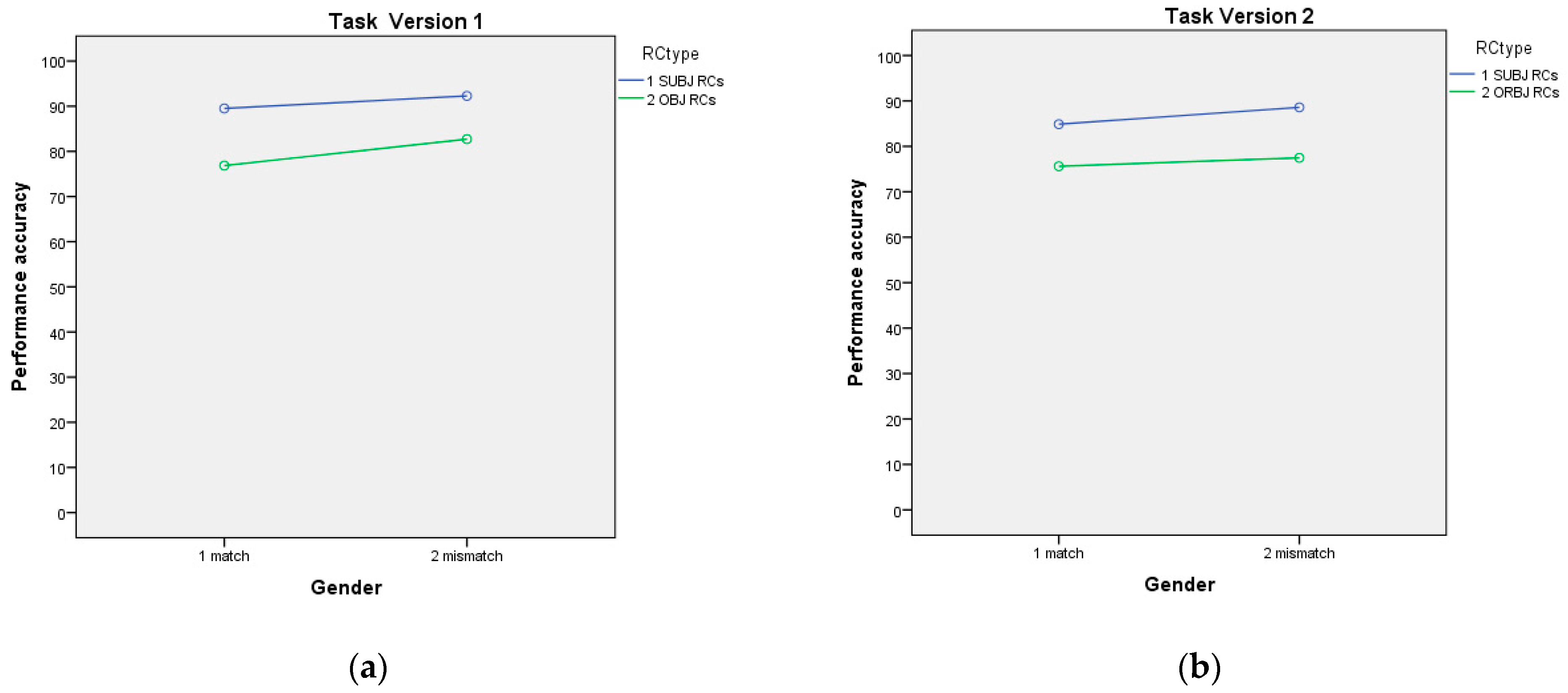

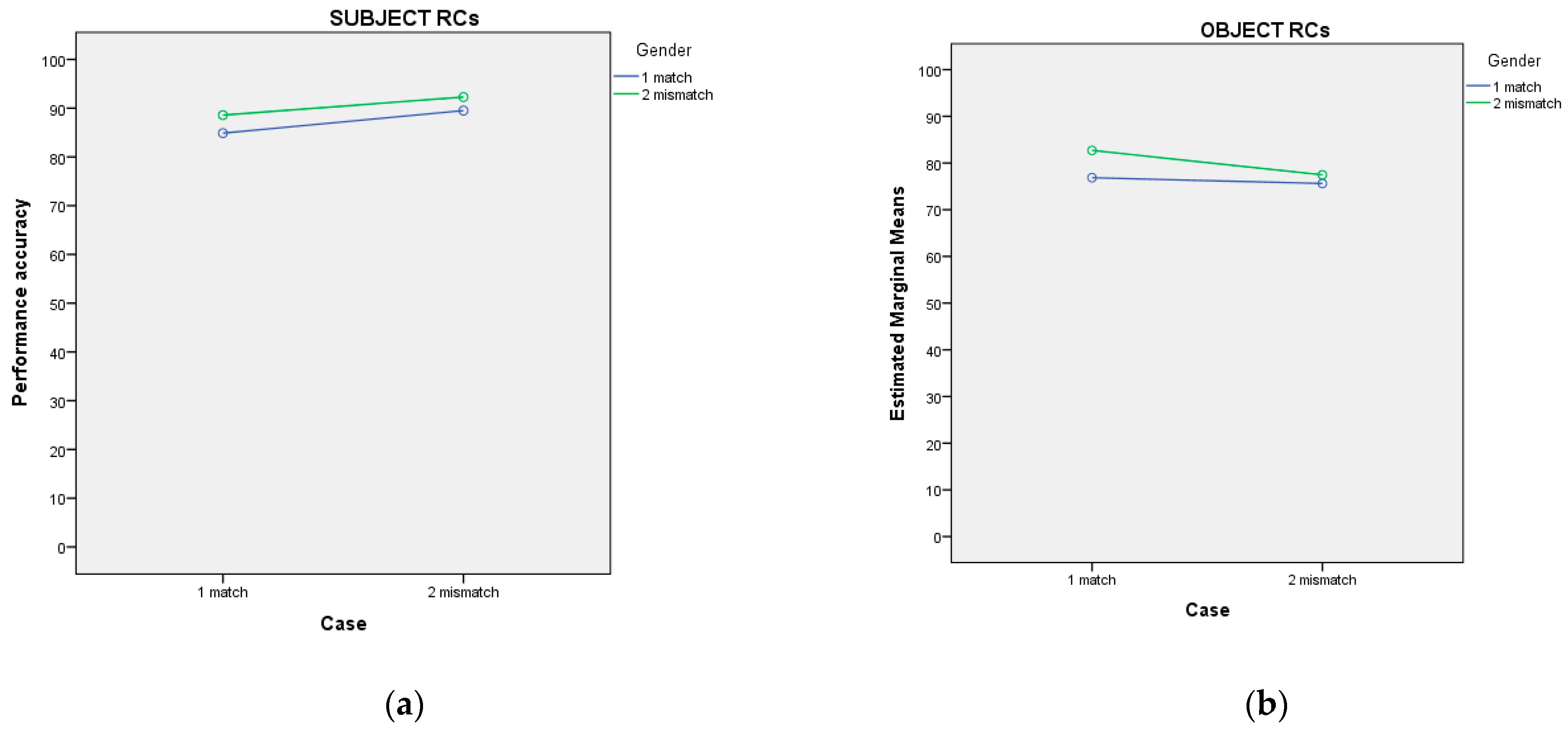

A comparison of performance on SUBJ and OBJ RCs in Task 1 showed a highly significant difference (p = 0.005); that is, children made more errors on OBJ RCs than on SUBJ RCs, as expected. The errors on OBJ RCs were further investigated with regard to gender feature. A comparison between OBJ RCs gender match and OBJ RCs gender mismatch does not show a significant difference (p = 0.162); namely, children did not benefit on OBJ RCs when the two DPs had a different gender feature.

The first conclusions to draw are that: (a) OBJ RCs indeed create a significantly bigger problem than SUB RCs for the Greek-speaking children, confirming previous findings for Greek (

Varlokosta et al. (

2015), (b) the same value for the feature gender does not constitute an additional source of difficulty for the comprehension of OBJ RCs in children’s grammar. It should be noted that Version 1 did not control for potential effects of the case of the head noun. Recall that the RCs in Version 1 are introduced by the instruction ‘here is...’, with the consequence that the DP that follows has nominative case. Both the relativized subjects, (8), and the relativized objects, (9), carry nominative case morphology, which is distinct and overt in Greek. Hence, in OBJ RCs, (9), nominative case, NOM, may be involved in the computation of similarity between the moved object and the intervening subject, and induce intervention effects which would render OBJ RCs even more difficult. Moreover, the relativized object of OBJ RCs has nominative case, and this may be another source of additional difficulty, besides intervention effects. We will return to these issues after we discuss the results from Version 2 of the experiment.

The subject/object asymmetry holds in Version 2 as well, with the difference between SUBJ and OBJ RCs being highly significant again (

p = 0.003). Moreover, comparison between OBJ RCs gender match and OBJ RCs gender mismatch does not show a significant difference either (

p = 0.528). This means that children did not benefit on OBJ RCs in Version 2 of the experiment either when the participating DPs had a different gender feature. Recall that in this version of the experiment OBJ RCs did not face the additional issues raised in Version 1 of the experiment, since a) the relativized DP had the same case as in its extraction site (accusative), and b) the two DPs of the sentence did not have the same case. It seems safe to conclude, therefore, that gender is not involved in intervention effects in early Greek. This is expected on the basis of the claim that only active morphosyntactic features trigger such effects in early language, and we have no reason to believe that gender is an active morphosyntactic feature in Greek in the relevant sense.

7If case induced intervention effects, hence, case match posed additional difficulties on children’s grammar, we would expect the OBJ RCs of Version 1 of the experiment to be more difficult than those of Version 2, as they contain two DPs with the same (nominative) case. This is not so, however, and we see that there were actually fewer errors on the first set of OBJ RCs, while the difference between the two OBJ RCs is not statistically significant (

p = 0.430). We conclude, therefore, that case, which is overtly and distinctively marked on feminine and masculine DPs in Greek, both on the determiner and the noun, does not induce intervention effects in child language.

8 Case of the Relativized DP and Its Extraction Site

A final issue that concerns this work is whether it matters if the case of the relativized DP is different from the case it has in its extraction site. Recall that in Version 1 of the experiment the relativized object of OBJ RCs has nominative case, rather than the accusative it receives in its extraction site, (9a), repeated below.

| (9a) | Edo | ine | i | vasilisa | pu | akoluthi |

| | here | Is | the.NOM.FEM | queen.NOM.FEM | that follow.3SG |

| | i | | | kiria. | | |

| | the.NOM.FEM | | lady.NOM.FEM | | |

| | ‘Here is the queen that the lady follows.’ |

On the other, in Version 2 of the experiment, the relativized subject of SUBJ RCs has accusative case, rather than the nominative it has in its extraction (subject) position, see (10a), repeated below:

| (10a) | Dikse | mu | ton | kirio | pu |

| | show | me | the.ACC.MASC | man.ACC.MASC | that |

| | fotografizi | | ton | magira. |

| | photograph.3SG | | the.ACC.MASC | cook.ACC.MASC |

| | ‘Show me the man that photographs the cook.’ |

Does it matter for children if an extracted object appears with nominative case, or an extracted subject appears with accusative? Given the omnipresence of Greek case morphology, an answer to this question is important for the validity of the various experiments that are administered to children, whose results may otherwise be contaminated. The relevant data are in

Table 4 below. Notice that the data we compare for OBJ RCs are the same as those investigating the possible intervention effects of case. This time, however, the comparison extends to SUBJ RCs as well.

If we compare the two versions of OBJ RCs, which differ in that in Version 1 the relativized object has nominative case, but in Version 2 it has accusative, we see that the difference (20.22% vs. 23.46% error rate, respectively) is not a significant one (p = 0.430). If we compare the two versions of SUBJ RCs, that is when the relativized subject has nominative case with when it has accusative, (9.10% vs. 13.27% error rate, respectively), the difference just reached significance (p = 0.41). We see in other words that it does not seem to matter whether an object/internal argument is marked for nominative case, but it may matter when a subject/external argument has accusative. A possible explanation might have to do with the fact that whereas internal arguments with nominative case are encountered in more than one other syntactic environments, e.g., in passives, unaccusatives, and middles, nominative arguments with accusative case are found in much fewer environments, e.g., ECM constructions.

Before concluding, we should mention a study that has been brought to our attention several times in the context of the current work, because it appears at first glance to contribute, in a slightly different manner, to the issue that concerns this last section.

Guasti et al. (

2012) investigated the effects of morphological case in the comprehension of subject and object RCs in Greek and Italian, via comprehension experiments with 27 Italian-speaking children (Range: 4.5–6.5) and 43 Greek-speaking children (Range: 4.5–6.5). Their experiments comprised pairs of sentences which differ in the way the grammatical function of the DPs, that is, subject/object, is distinguished in the RC. For instance, the RCs in (12a) and (12b) feature two DPs formed with the articles

to and

ta (neutral SG and PL, respectively).

To and

ta are ambiguous between the nominative and accusative case so in principle, the DPs in examples such as (12) could be used as subjects or objects of the verb. The only way in which the grammatical function of neutral DPs can be distinguished in RCs is via subject agreement on the verb. Concretely, the RC in (12a) is a SUBJ RC because the verb agrees in number with the relativized DP,

to alogo ‘the horse’. On the other hand, the RC in (12b) is an OBJ RC because the verb displays 3PL agreement, which is the number specification of the post-verbal subject.

| (12) | a. | Dikse | mu | to | alogo | |

| | | show | me | the.ACC.NEUT.SG | horse.ACC.NEUT.SG | |

| | | pu | kiniga | ta | liontaria. | |

| | | that | chase.3SG the.ACC.NEUT.PL | lions.ACC.NEUT.PL | |

| | | ‘Show me the horse that chases the lions.’ |

| | b. | Dikse | mu | to | alogo | pu |

| | | show | me | the.ACC.NEUT.SG | horse.ACC.NEUT.SG | that |

| | | kinigun | ta | | liontaria. | |

| | | chase.3PL | the.NOM.NEUT.PL | lions.NOM.NEUT.PL | |

| | | ‘Show me the horse that the lions chase.’ |

In (13), the verb carries 3SG agreement in both cases. Nonetheless, the gender of the DPs is feminine and the article combining with feminine DPs is different in nominative and accusative case, i and tin, respectively. With DPs, as those formed with i or tin, that are unambiguously marked with case, OBJ RCs are distinguished from SUBJ RCs by their case marking. For instance, (13a) features a SUBJ RC: the post-verbal DP carries accusative case and thus, functions as the object of the verb of the RC. The relativized DP can only function as the SUBJ of the verb of the RC, but is assigned accusative case in its surface position from the matrix verb. In (13b), the postverbal DP carries nominative case and thus it is interpreted as the subject of the verb. The relativized DP is the object of the verb of the RC and is marked with accusative case, as expected.

| (13) | a. | Dikse | mu | ti | maimu | |

| | | show | me | the.NOM.FEM.SG | monkey.NOM.FEM.SG | |

| | | pu | pleni | tin | arkuda. | |

| | | that | wash.3SG | the.ACC.FEM.SG | bear.ACC.FEM.SG | |

| | | ‘Show me the monkey that washes the bear.’ |

| | b. | Dikse | mu | ti | maimu |

| | | show | me | the.ACC.FEM.SG | monkey.ACC.FEM.SG | |

| | | pu | pleni | i | arkuda. | |

| | | that | wash.3SG | the.NOM.FEM.SG | bear.NOM.FEM.SG | |

| | | ‘Show me the monkey that the bear washes.’ |

As far as the more general phenomenon goes,

Guasti et al. (

2012) observe an SUBJ/OBJ asymmetry in the comprehension of RCs showing, as expected, that SUBJ RCs are easier to comprehend. The authors also present a formal explanation of this asymmetry using machinery that has been introduced in previous work by

Villata et al. (

2016). Setting this asymmetry aside, the novel, and more interesting, finding in

Guasti et al. (

2012) is that Greek-speaking children comprehend better the kind of OBJ RCs in (13b), where the function of the DPs is disambiguated by morphological case marking than those of (12b) where it is disambiguated by number marking. This is the finding that led

Guasti et al. (

2012) to the conclusion that morphological case matters for the comprehension of RCs. We do agree with their conclusion that case does matter, and is probably what explains a different fact we have not commented on, namely, that by contrast to Italian where case is not marked at all, Greek speaking children perform better in the overall in object relative clauses. It is important to note, however, that their work does not extend to a central question of ours, namely, whether case matters in the computation of locality, in the same way that gender and other formal features have been argued to do (cf.

Belletti et al. 2012, i.a.). In regard to locality, we saw that case does not play any role and in fact, it is not expected to play any different role in the computation of locality in (12b) and (13b) because in both examples, the relativized object has accusative case which is different from the nominative case carried by the subject. The only factor that is different between (12b) and (13b) is the morphological exponence of nominative case: in the first, it is syncretic with the accusative whereas in the latter, it is not. This difference is not predicted to play a role in the computation of locality in any obvious manner, however.