Abstract

Ethos, the speaker’s image in speech is one of the three means of persuasion e stablished by Aristotle’s Rhetoric and is often studied in a loose way. Many scholars develop lists of self-images (ethos of a leader, modesty ethos, etc.), but few explain how one arrives at these types of ethos. This is precisely what the inferential approach described here intends to do. Considering, like many discourse analysts, that ethos is consubstantial with speech, this paper provides an overview of various types and subtypes of ethos and highlights how these can be inferred from the discourse. Mainly, we would like to point out that what the speaker says about him or herself is only a part of what has been called “said ethos”: inferential processes triggered by what the speaker says about collectivities, opponents, or the audience also help construct an ethos. This tool will be applied to analyze a corpus of Donald Trump’s tweets of 6 January 2021, the day of the assault on the Capitol. As the notion of inference is essential in creating ethos, the paper pleads for the integration of the study of this rhetorical notion in the field of pragmatics.

Keywords:

ethos; discourse analysis; images; inferences; interpretation; rhetoric; pragmatics; Donald Trump’s tweets 1. Introduction: The Importance of ethos and ethos Types

Among the concepts invented by Greek and Roman rhetoric, the classical triad of the technical means of persuasion—i.e., ethos (character of the speaker), logos (speech and argumentation), and pathos (emotions of the audience)—is widely known, learned and still used today. For example, many studies in cognition and psychology are focused on the issue of the credibility of the source in the persuasion process (; ), and many studies in marketing ( for a meta-analysis). The credibility of the source is summarized in the latter article as the result of three different characteristics: expertise, i.e., “the extent to which a person can provide the correct information”, trustworthiness, i.e., a “recipient’s degree of message trust of the advice given by the information communicator”, and homophily, i.e., “The degree to which two or more individuals who interact are similar in certain attributes (e.g., beliefs, education, social status)” (). In a certain way, these characteristics echo Aristotle’s triad of “good sense, virtue, and goodwill” (, Rhet. 1378a), as good sense is a form of practical wisdom which highlights the competence of the speaker, virtue represents the moral qualities that may lead (or not) to trust, and goodwill implies a closeness between individuals, akin to the notion of “homophily”. Ethos is a key component for the aim of persuasion. Indeed, many studies since () have shown that “we are more likely to be persuaded by sources we perceive to be powerful, in authority, attractive, likable, or similar to us than by sources we perceive as not possessing these traits” ().

Even if the notion of “ethos” has lived for 2500 years, its relevance remains undisputed: its persuasive potential is proven powerful and central to many contemporary persuasion techniques. But what seems salient about all the sub-categories mentioned above—the character traits of “trustworthiness or goodwill”—is that they correspond to representations that result from inferential processes. As (; emphasis mine) pointed out: “Credibility (or, more carefully expressed, perceived credibility) consists of the judgments made by a perceiver (e.g., a message recipient) concerning the believability of a communicator”. As ethos, in principle, is “achieved by what the speaker says, not by what people think of his character before he begins to speak” (, Rhet, 1355b10), speaking of “goodwill” or “degree of trust” is neither a pre-existing condition nor background knowledge. It is the conclusion of an inferential process, which can be described as an abduction (; ): the linguistic details and features of a text give rise to one or many tacit inferential process(es) whose conclusion is that the speaker´ appears to be “trustworthy” or seems to be “benevolent”. In other words, the study of ethos requires an understanding/analysis of how linguistic resources help speakers establish their character. “For example, speakers must not say ‘I am competent in international finance’, but should instead display such competence by quoting statistics or using specific lexicon as indexes of their knowledge and abilities. As has been frequently noted, ethotic indexes operate at different levels of analysis, ranging from prosody and lexical choices to grammatical structures and speech acts […])” ()1. Because it is the result of inference in a certain context, ethos is a construction that is, by nature, an issue of pragmatics.

This process of interpretation of signs poses a theoretical problem. It cannot, in principle, be understood as an implicature in a Gricean sense, since it is not essential to meaning nor to understanding what the speaker intends to communicate. Because this is an abductive process, the ethotic conclusion is logically invalid and fragile. At best, it could be a convincing interpretation of linguistic signs, which is not necessarily shared by all message recipients2. Finally, this interpretation might even be not fully intended by the speaker in many cases. And yet, it could be considered an implicature because “any assumption communicated, but not explicitly so, […] is an implicature” (). The fact that the speakers are not forcefully committed to an intentional construction of their ethos (they might even be not aware of it) thus seems to belong to a gray area in pragmatics. A cover letter littered with spelling mistakes creates an ethos surely unintended by the writer, for example, and would not be considered an implicit assumption communicated by the latter—and, yet again, this is part of the writer’s ethos. Nonetheless, “relevance theory assumes that implicatures come in varying degrees of strength ranging from very strong implicatures to very weak ones, which shade off into entirely unintended contextual implications” (). Could most ethotic interpretations be considered as very weak implicatures? I will come back to these theoretical considerations at the conclusion of this paper.

Neo-Aristotelian definitions of ethos insist that it is an effect of speech, implying that it is not a synonym for ‘speaker image’. “And, though the character is ´revealed´ by speech, it is as likely to be ‘constructed’” (). While the notion of ethos is sometimes used in argumentation for what is called ethotic argumentation (; ; ; ), it not only deals with the ethos of a speaker, but it also relates to other speakers’ images3. In the same way, ethos is often divided between “said ethos”, “shown ethos” (see more on these categories below), and “represented ethos” (), the latter being the representation of the ethos of a speaker by commentators or members of the audience. While it can be useful (insofar as the commentators are sincere) to see if the represented ethos confirms the analysis of said and shown ethos, it remains an image of the (former) speaker by someone else who is precisely building his or her own commentator ethos. Hence, the nature of ethos first and foremost as an inferential construction disappears and is often used as a synonym for a given “image”. To add to the confusion, prediscursive ethos, the image of a speaker before his or her speech, is not a construction: it is a preliminary image, more or less stabilized, on which the discursive ethos will capitalize. Nevertheless, it seems that widening the notion of ethos to the idea of “images of self and others” could be considered as the effect of the somewhat opaque nature of the cognitive process of construction of an ethos: the images, i.e., the results of the construction are often more highlighted than the construction processes themselves in the literature. It is perhaps an effect of what Walton is pointing out here: “We make character judgments all the time anyway. These are judgments that large numbers of people make routinely. The problem is to gain insight into how they are made and how they should be made, and to carry out this task not in any arbitrary or God-like way but by understanding the kind of reasoning we already use and learning more about its structure” (). I would like to precisely focus less on the results than on the process, i.e., highlight how ethos may be analyzed in its construction from a discourse analyst’s point of view (Section 2 and Section 3). This process does not exclude other existing types of ethos, prior images of others, or the speaker in the analysis, nor argumentative strategies of ethotic attack, but attempts, if possible, to acquire an exhaustive tool for analyzing the image of a speaker as it is constructed in a speech.

Ethos is a concept that is not frequently used by English-speaking theories of Discourse Analysis and Argumentation theory, to the best of my knowledge. For example, recent handbooks on critical discourse analysis (; ) mention ethos only in passing. Moreover, a recent computational study that attempted to mine ethos in political debate () acknowledges the lack of studies on this subject, particularly artificial intelligence. Conversation Analysis, however, frequently uses the seminal works of Erving () and ’s () face theory about self-presentation. And recently, an international network for the study of credibility, ethos, and trust (INCET) hosted at the University of Bergen has been created around rhetoricians, philosophers, and discourse analysts. This picture must also be tempered by the fact that several works written by philosophers of argumentation propose research on the notions of trust, credibility, and expertise. Trudy (, ) examines various issues related to the unavoidable trust we need in human society: “When someone tells us something, and we accept the claim on his say-so, trust is involved. We presume the other person intends to tell us the truth and is sufficiently competent to do so” (). Douglas Walton, on the other hand, examines how to judge the character of others, mainly in the legal field, highlighting the abductive process of this evaluation and the lack of strong evidence to do so (2006). Although they barely mention the rhetorical notion of ethos, the process of evaluation leading to the judgment of others is nothing less than ethotic evaluation4.

In contrast, the massive interest in ethos found in French Discourse Analysis (, ; ; ; ; ; ; , ; ; ; ; , , ; among others) come partly from one of the core ideas of Oswald ’s (, my translation.) linguistic theory: ethos is shown and not said (“It is not the flattering statements that the speaker may make about herself in the content of her speech, statements that may, on the contrary, offend the listener, but the appearance is given by the delivery, the intonation, warm or dry, the choice of words, the arguments …”. This is important because ethos ceases to be tied to a rhetorical genre or the rhetorical aim of persuasion only. For the French discourse analysts, ethos is consubstantial with speech: “For discourse analysts, unlike traditional rhetoricians, ethos cannot be reserved for certain uses of speech, in particular oratory-type situations, whether deliberative, judicial or epidictic. As soon as there is enunciation, something of the order of the ethos is released: through the speech, a speaker activates the construction of a certain representation of herself for the interpreter. Her mastery over her speech is endangered, and the speaker must therefore try to control the interpretative processing of the signs she is sending” (, §6, my translation). Such a posture may imply a strong hypothesis: the idea that an audience is constantly inferring something about the speaker’s image from what is said.

Given the importance of credibility in persuasion and the protohistoric and developmental need we have to trust some people and be cautious with others, it would come as no surprise that our cognition is always evaluating the message and the speaker simultaneously. The idea of a constant evaluation of the image of others could be frightening concerning the representation we have of human and social relations in general, as if we were constantly spying on each other without being able to trust each other fully. However, () showed, for example, that “we have seen that this latter [4-years-old children] do not swallow indiscriminately what is communicated to them. Nevertheless, if no contradiction with information already possessed is detectable and the speaker does not demonstrate signs of untrustworthiness, children will accept the communicated propositions and enrich their stock of belief”. This observation about young children shows that they develop quite rapidly a form of epistemic vigilance (), which itself suggests that background interpretative inferences about ethos (“who to trust?”) are probably mechanisms that can be activated in situations in which we have reasons to gauge the speaker’s trustworthiness. Moreover, this also suggests that it is important for human beings to be able to make these interpretative inferences and to interpret the environment based on different clues (past experiences, etc.). While evaluating the ethos of a speaker may not be a constant conscious process, which can be more salient only when our epistemic vigilance is on alert, it also seems possible to imagine that activating our epistemic vigilance is an effect on the evaluation of the credibility, the trustworthiness or the benevolence of a speaker when this background evaluation is giving rise to suspicion. Finally, regardless of when this evaluation process takes place, its importance is not deniable.

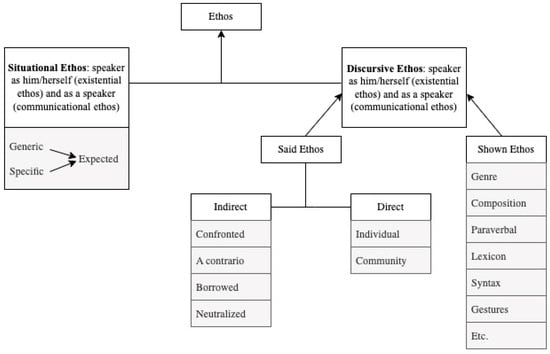

This evaluation process remains extremely complex, multifactorial, and underexplored in the linguistic literature on ethos in the field of discourse analysis, which more often unsystematically highlights lists of different traits or linguistic marks5. The aim of the present paper is precisely to address, in a more systematic way, the “inferential complex” underlying the calculation of the speaker’s ethos, paying particular attention to the notion of “said ethos”, which has always been the weakest or least examined category in recent research in the field. The ambition of this article is to provide a methodological tool that allows us to offer an answer as complete as possible to the question: “What is ethos and how is it constructed?”. More precisely, I contend that ethos is the result of multiple inferences that are drawn from many sources, which are summarized in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1.

Ethos types.

In this figure, ethos is shown as the result of the confrontation between what is called situational ethos, i.e., the image of the speaker before they utter the first word in the current situation, and discursive ethos, i.e., the image that is constructed through their speech. This first distinction separates what is given, a preliminary image, and what is constructed in situ. The situational ethos builds on two information sources: 1. a more or less extensive and more or less intimate knowledge of the people who are going to speak; 2. stereotypical expectations triggered by some aspects of the speaker (his/her clothing, age, occupation, nationality, etc.). Situational ethos is elsewhere described as a prediscursive or prior ethos (, for example), as opposed to discursive ethos, which is much closer to the original Aristotelian definition (an effect of the speech and not a prior image). The generic, specific, and expected subtypes seem to cover the main prior prediscursive images, from stereotypes to actual knowledge about the speaker and from expectations in general and expectations within the situation (see Section 2).

For the discursive ethos, I use two subtypes that are often found in the literature about ethos: what has been semantically said about the image of the speaker and what is shown through many communicational clues (prosody, gestures, tone, rhythm, syntactic and lexical choices, etc.). I adopt a distinction already made by Ducrot between said ethos and shown ethos. Still, I refine the first of the two through various ethotic stagings about which little has been written and which are particularly interesting for the inferences processes they trigger (see Section 3.2). The stagings cover the cases in which the speakers says something about themselves, individually or within a community, they are in (direct ethos). They also cover cases when a speaker gives images of others, for example, the audience (indirect ethos). Whereas shown ethos can be expressed through a multitude of signs, said ethos is based on a relatively closed list of possibilities of self-expression.

It should be noted that I also distinguish two “targets” in ethos construction: the image of the speaker as the manager of his or her discourse (communicational ethos) and the image of the speaker as his or her personality, his or her being6 (existential ethos)—these targets are only mentioned in Figure 1 because it would be too confusing to represent them and their interactions. Let us say that the ethos of anyone who speaks refers to a double role held simultaneously: the role of the speakers and that of their public function. The communicational ethos is metadiscursive and targets the image of the speakers in their communicative activity: what is their role in this communicative situation? Do they seem confident in their speaking activity? What do their communicative choices mean about their communicative strategy? All are questions that could be tackled under this label.

I will explain in the following pages how I justify Figure 1. More specifically, in Section 2, the situational ethos will be described as an ethos based on prior knowledge about the speaker, i.e., an ethos that is not “in the technique” and therefore rejected by Aristotle. In contrast, many contemporary works on ethos recognize the importance of prior impressions in the persuasion process (). Shown ethos will be detailed in Section 3.1. In Section 3.2, I will discuss the notion of said ethos, whose inferential nature has not been considered until now. The typology will be illustrated by analyzing Donald Trump’s tweets on 6 January 2021, the day protesters walked down to the Capitol, encouraged by Trump’s speeches. In conclusion, I return to the problematic theoretical issue related to the type of pragmatic implicit meaning ethos may correspond.

2. Situational ethos

While many discourse analysts adopt the label of “prediscursive” or “prior” ethos, I chose the label of “situational ethos” to highlight that everything until the last second before a speech can be considered as building this “prediscursive” ethos, even some contextual parameters of the speech: time, location, type of the audience, etc. It is probably a detail, but the idea here is to point out the state of the speaker’s ethos at a given point in time.

I propose considering three subtypes of situational ethos: generic, specific, and expected. The idea is to cover stereotypical inferences and actual knowledge about the speaker. Generic ethos is an ethos set by default. Imagine that you do not know the speaker who is just introduced on stage as Marcus Rhein, a German physicist who got a prize for his scientific research. Probably, you are already inferring different images from stereotypes about Germans, men, physicists, scientists, prize-winners, and so on. Moreover, you are also comparing the stereotypes and the figure standing on stage: is he exactly as you imagined? Are you surprised by his rock star looks? Our cognition loves to compare stimuli with some standards: “Whenever we interact with others, we judge them, and whenever we make such judgments, we compare them with ourselves, other people, or internalized standards” (). Experiments have shown that we form impressions of others even when relevant information is scarce ().

In the case of Donald Trump, we cannot say that his generic ethos is especially relevant since the whole planet knows him at the time as the President of the United States, as a former businessman, and as a former TV star. Nevertheless, this does not mean that generic ethos is not relevant in a comparative way: our cognition probably compares the stereotypes of the President, businessman, and media personality with what Trump had shown in the past. Communicational ethos about a generic user of Twitter is probably also present in the background. Generic situational ethos may not be salient, but it can be activated in the background as a comparison point. It is the same with different stereotypes about seventy-year-old white and rich males, about Republicans, about Americans, about New York or Florida inhabitants, about golfers, and so forth. Whether these stereotypes are accurate or not is not the problem for a discourse analyst. Still, this question does lead to a methodological problem: to what extent is a discourse analyst aware of these stereotypes? As I am not an American citizen, it is difficult for me to represent these stereotypes. For example, if I study a speech from 1848 written by Victor Hugo, I will not have access to the specificities of the public opinion about the realities he is denouncing. I would therefore recommend extreme caution in the interpretation of this kind of ethotic background.

Specific ethos can be more documented. This situational ethos subtype contains everything we know about the speaker before the time of speech. The more we know about a speaker’s history, the more specific ethos will be enriched. Since Donald Trump’s life is largely public, much is known about him. Breaking all the standards of a “normal” presidency, Trump’s ethos of a maverick and a populist leader is obvious on 6 January 2021. He is even known, at the time, as the first President who did not accept that he lost the election. The ethos of a speaker as a Twitter user has moreover already been discussed in studies that describe a break with presidential communication on social networks: “However, with President Donald Trump, a new type of Twitter use has emerged that is reflective of a move towards what () terms ‘ de-professionalization. Since emerging as a prolific tweeter during his 2016 election campaign, Trump has demonstrated an ongoing tendency to author his tweets through his personal Twitter account in a display of ‘gut-feeling’ and impulsive tweeting () that is significantly different than professional, focus-group-tested tweeting” (). It would be well beyond the scope of this paper to determine all the parameters that are relevant to the notion of specific ethos. Still, it is part of the discourse analyst’s job to imagine what can be known about the speaker at the time of communication to identify the risks and challenges of a speech, for example.

Donald Trump’s trustworthiness is completely polarized: media like the Washington Post have counted 30,573 false or misleading claims during Donald Trump’s presidency7, but many Trump supporters are still convinced by what he says, mainly, for the corpus we analyze, by the fact that the election was a fraud, even though Trump lost not only the electoral college by 306 against 232 electoral votes but also the popular vote by more than 7 million. The public image of Trump is often depicted, among many other judgments, as a “textbook narcissist”: “Identifiable negative traits of narcissists include sensitivity to criticism, poor listening skills, lack of empathy, intense desire to compete, arrogance, feelings of inferiority, need for recognition and superiority, hypersensitivity, anger, amorality, irrationality, inflexibility, and paranoia. Some of these traits seem to fit Trump”8. On the other side, it seems that supporters of Trump are still considering him as someone who is shaking the system, “draining the swamp” and who gives hopes of change to a lot of people who are resentful9. The problem for a discourse analyst, here, is to figure out not what the specific ethos of Donald Trump is on the morning of 6 January 2021, but what the specific ethoses for different parts of the audience are10.

Finally, expected ethos is a sub-category that is closely connected to the context of the situation: it can be summed up as what we are expecting from the speakers at the time they will talk. This category seems useful to me since the stakes of the speech or the context preceding it are surely important data for the discourse analyst, and thus, the need to adapt the generic or the specific ethos to a precise situation seems necessary to me. On 6 January 2021, Trump’s expected ethos could be the same as the preceding days: a man who refuses to accept that he lost the election and will fight against the electoral process. After the assault on the Capitol, however, his expected ethos is far more difficult to predict: will he portray himself as a peacemaker to avoid violent outbursts, which is expected by many witnesses, or will he conform to the specific ethos he has always shown: that of a fighter refusing half-measures or compromises, which risks setting the world on fire if this has not already happened? A 180-degree turn in his communication would probably not be credible. Besides, the two tweets calling for de-escalation this day are stylistically different from the other tweets of the day. Expected ethos is by far the most difficult category for the discourse analyst because of its cognitive reality within short periods: we cannot be sure of it, and very weak inferences are drawn based on a convergence of a given situation, with its typical and atypical aspects, and the speaker whose generic and specific ethos have been outlined. The result of this “convergence” creates an expected ethos which can then be compared to actual discursive ethos: whether it confirms or invalidates the expected ethos will be one of the questions to be asked.

Moreover, the violation of what could be expected in the situation is also a way of building the speaker’s ethos. While many TV commentators, politicians, and members of the Trump family expressed their expectations that Donald Trump would intervene quickly to stop the assault on the Capitol11, the latter reacted rather late (over two hours after the breach) in a televised message showing no firmness towards the assailants, calling for peace but reiterating his claims of election fraud and concluding it by: “we love you, you’re very special.” Multiple violations of a president’s expected ethos in such situations may form a basis on which the audience infers that President Trump is unworthy of his office, for example.

While the latter category suggests inferences made by the discourse analyst, nothing here really concerns pragmatic aspects of ethos: it is more a way of representing the contextual background of the image of a speaker that helps create rhetorical ethos. Indeed, it can be argued that this background can serve as a premise on which discursive ethos can be built, as I have just shown by comparing expected ethos and violations of these expectations. Situational ethos will guide the inferences that could be drawn from the text—it functions as a cue on which the inference that seems the most relevant can be drawn from the linguistic resources in the speech.

3. Discursive ethos

Ethos gradually built as discourse unfolds can be either shown or said. Discursive ethos is thus more the result of an inferential process based on different “symptoms” or cues in a text (shown ethos) than a self-portrait of the speaker (said ethos). In the latter category, direct ethos can be defined as covering cases of self-images that are personally (“I”) or collectively (“we”, “scientists”—when the speaker is one of them) conveyed. Indirect ethos covers cases where inferences—akin to weak implicatures ()—may be derived from how other people or groups are referred to. Interestingly, indirect ethos can be created from the image given of others in one’s discourse, as has already been shown ().

The methodological processes involved both in the analysis of ethos and in identifying its outcome are complex. On the one hand, the analysis of ethos sometimes has to resolve potential tensions generated by a discrepancy between said ethos and shown ethos. On the other, the analyst should also decide whether ethos should be reduced to a character trait (“he looks anxious”), to a social role (“she marks her leadership”), or to a prototypical figure (“she embodies a form of Solomon’s justice”). Maingueneau considers three different dimensions:

- “1. The ‘categorical’ dimension covers many things. They can be discursive roles or extra-discursive statuses. Discursive roles are those linked to the activity of speaking: host, storyteller, preacher, etc. Extra-discursive statuses can be of very varied natures: father, civil servant, doctor, villager, American, bachelor, etc.;

- 2. The “experiential” dimension of ethos covers stereotypical socio-psychological characterizations associated with the notions of incorporation and the ethical world: the common sense and slowness of the countryman and the dynamism of the young executive.

- 3. the ‘ideological’ dimension refers to positions in a field: feminist, left-wing, conservative or anticlerical in the political field, romantic or naturalist in the literary field, etc.” (, my translation).

However, Maingueneau points out that these dimensions can interact. () also proposes a list of ethotic figures: the ethos of virtue, provocation, intelligence or humanity, etc. The list could be infinite and, again, highlights more the result of an ethotic evaluation than the process leading to this result. I submit that an inferential approach to ethos is methodologically simpler and more fruitful in terms of its explanatory power. It would avoid the limits of an unnecessary proliferation of categories involved in list-making. Such an approach would consider that we all have stereotypical ethotic repertoires in our cognition against which a given discursive ethos can be assessed, but that, crucially, the selection of one or more elements from this repertoire should be made according to a principle of relevance. The number and qualitative importance of the elements identified by the analysis of discursive and situational ethos make it possible to make one or more types of ethos salient and relevant among the repertoire of possible types. For example, in the following tweet by Trump (“Get smart Republicans. FIGHT!”, 12:43 a.m., 6 January 2021), one can probably infer the ethos of a sports coach or an army chief—and this difference is precisely at the core of the legal problem we face in the assessment of these tweets (see below). The main question is why these types of ethos—and not others—are extracted from the repertoire. And it is this issue we will now tackle.

3.1. Shown ethos

The main problem with shown ethos is that complete cartography of ethos indexes is impossible: non-verbal, paraverbal, and verbal cues alike can be used to interpret the speaker’s ethos. For example, the following tweet (6 January 2021, 8:17 a.m.): “States want to correct their votes, which they now know were based on irregularities and fraud, plus corrupt process never received legislative approval. All Mike Pence has to do is send them back to the States, AND WE WIN. Do it Mike, this is a time for extreme courage!”. Because of the textual nature of the tweet, non-verbal communication is not relevant here, but capital letters and exclamation marks do contribute to the construction of an ethos of a man speaking loudly, giving an order, who seeks support to restore justice; therefore, Trump’s ethos is that of a victim who will not accept his unjust fate. He is also showing himself as dependent on Pence’s goodwill: while this can be interpreted as a sign of loss of control or loss of power, this ethos is counterbalanced by the pressure he exerts on the Vice-President. Trump portrays himself as potentially even more defrauded if the person defending him, Mike Pence, in this case, does not do what he asks: by insisting on the simplicity and obviousness of the process (“all Mike Pence has to do”), Trump is already portraying Pence as a coward, or even a traitor if he does not comply with this simple request12, which will amplify an ethos of the victim abandoned by his people. The first sentence is also asserted as a fact (despite the lack of evidence for the claim, which is considered a lie by fact-checking websites); the disjointed syntax could be a sign of irritation; the change from a third person pronoun to a second person interpellation further increases the pressure on Pence: these signs highlight the victimization of Trump, who is now supported only by the lay people, assuming that Mike Pence’s support is already put to the test. In constructing an ethos of the victim of the political maneuvers made by what he called the swamp, Trump is already dropping his vice-president (he is very probably informed that Mike Pence does not have the legal power to do what he asks of him) and positioning himself as someone calling for help from the street.

This analysis is founded on many different signs of shown ethos: capital letters, syntax, choice of lexicon, etc. I could also use intertextuality since many tweets from the election show Trump as increasingly isolated, abandoned by his closest supporters in the Senate, and so on. Amongst the ethos repertoire, the ethos of the victim of the “swamp” seems relevant and salient here, especially as it is obvious that he has few illusions about what Mike Pence will do, to whom he offers no way out except by the impossible, illegal, and unconstitutional act that he demands of him. While this should not come as a surprise, such an ethos is interesting because it highlights that hope can no longer come from politicians but only from the unconditional supporters of the Trump presidency, from the street, which seems to me to be an explanatory factor for the assault on the Capitol that will take place a few hours later.

Now, this process of interpretation is typical of a critical stylistic approach to discourse (; ), for which the analyst is mostly responsible. Can we really say that the ethotic proposition “I am unfairly victimized by political blows” is a (weak) implicature of this text? I think so and I interpreted this tweet like this, but I am aware of the interpretative fragility. Nevertheless, part of the interpretation here is closely dependent on Trump’s image of Mike Pence. This could be a key to assessing said ethos.

3.2. Said ethos

In the literature about ethos, said ethos is probably under-represented. First and foremost, because speakers rarely speak about themselves, seeing as this is arguably not persuasive: showing your expertise by mastering some jargon seems more efficient than saying you are an expert, which can, incidentally, display an ethos of arrogance. Nevertheless, besides individual ethos, many other subtypes are possible and interesting to analyze. The main idea in these subtypes is that giving an image of others is also an important way of building one’s own ethos through inference. When Trump says in his 10:44 a.m. tweet: “These scoundrels are only toying with the @sendavidperdue (a great guy) vote”, the image of the persons in charge of the counts of the vote in Georgia (“scoundrels”) as well as the qualifying adjective (“great”) about senator David Perdue are building an ethos of Trump too, through the persons he (dis)likes. This is one of the reasons I try to maintain a difference between image(s) and ethos, the latter being inferred by the former in the following subtypes.

The six sub-categories of said ethos are supposed to cover all possible cases that can be roughly summed up by the personal pronouns and the position taken in the relationship to others (positive, negative, or neutral), as manifested on the semantic level: I (individual ethos), you (confronted), we (community), he/she/they considered as allies (borrowed), as opponents (a contrario) or as third parties (neutralized). The interest of the closed list is not the multiple labels of subtypes but the fact that it is closed and helps to identify different ethotic strategies without creating ad hoc ethos types.

The second subtype of a direct ethos is community ethos, i.e., the ethos of a community in which the speaker evolves. Community ethos can be associated with the pronoun “we” but is not necessarily tied with this pronoun: the speaker may use allegories or adopt the ethos of a spokesperson. The implicit meaning used in this case is not founded on an implicature but an entailment first: if I say that “US citizens need it” and I am a US citizen, it implies that I support the same view. Let us take two examples in the corpus. “THE REPUBLICAN PARTY AND, MORE IMPORTANTLY, OUR COUNTRY NEEDS THE PRESIDENCY MORE THAN EVER BEFORE […]” (6 January 2021, 8:32 a.m.). This tweet in capital letters is interesting since Donald Trump seems to be distant: instead of “me”, which, even for him, might sound outrageously narcissistic, he stated “the presidency”, disengaging in some way from his involvement. The sentence becomes a truism, and ‘the presidency’ hardly disguises the “me” intended here.

Nevertheless, Trump tries to hide his personal aspirations behind higher aspirations: those of his party and his country. Where individual ethos might threaten Trump’s face, community ethos (of the country or the Republican Party), from which individual ethos is derived by entailment, avoids creating an image of a power-hungry loser, for example. In the second example, “us” and “we” are clearly used in the same way: “1:00 a.m.: If Vice President @Mike_Pence comes through for us, we will win the Presidency” (6 January 2021, 1:00 a.m.). Trump’s individual ethos merges with his movement as if the individual victory were a collective victory. Of course, ‘we’ and “us” entail ‘I’ and “me”, which, for politeness reasons, are routinely dispreferred. This first implicit inference (an entailment) may follow the weak implicature based on the rhetorical strategies observed here. That is to say, an implicature founded on the fact of using the plural rather than the singular form may find its relevance in building a particular ethos: the ethos of a winner supported by Mike Pence and the voters’ movement, in this case.

Confronted ethos is a label that I propose to use when a speaker’s ethos is derived from the image of his/her addressees (you); therefore, ethos is indirectly built from the images of others. By implication, giving the image of a “you” is always dissociated from the image of “I” (if the image had been similar, the use of a community ethos would have been more relevant)—the assessment of this difference is crucial in this subtype. In the last (and soon deleted) tweet of this day, after the assault on the Capitol, Trump uses a very provocative confronted ethos: “These are the things and events that happen when a sacred landslide election victory is so unceremoniously & viciously stripped away from great patriots who have been badly & unfairly treated for so long. Go home with love & in peace. Remember this day forever!” (6 January 2021, 6:01 p.m.). While a large part of his audience is qualified as “great patriots” in the third person (they), the last two sentences (and orders) are clearly addressed to the protesters (you) and exhibit confronted ethos. He flatters the patriots who stormed the Capitol and creates an image of paternal (or paternalistic) love13, expressing pride about the action of his supporters and eager for these patriots to remember this day as a glorious one, for it is hard to imagine in such a context that ‘remember this day forever’ would be interpreted as a day of shame. The ethos of a protector (“in peace”) acting like a proud father (“go home”) does not show an ounce of regret for actions that have just shaken American democracy to its foundations; moreover, he is justifying the violence against institutions. This tweet is shocking in the context of the violation of democratic foundations; one of the reasons is, of course, that the ethos of a POTUS is supposed to be, prominently, to defend US institutions and democracy: Trump rejects the expected ethos of a president and unveils once more the lack of respect for the institutions that elected him, thereby reinforcing the image of outsized egocentricity and of a president who is unlike any other, a maverick who does not share the codes, customs, and values that come with political power. Trump does not show a hint of regret for unprecedented action, showing himself as being unaware of the symbolic gravity of the event. His tweet begins by denying any responsibility, as he conveys something along the lines of “you had it coming”. One hour later, Twitter removed Trump’s tweets from the day and shut down his account for 12 h before suspending it permanently. The lack of empathy for people (mainly his supporters) who died in the riot is obvious, and the ethos of Trump-as-president is more fragile than ever, as the expectations of what any president should have done in such a situation are violated. As these multi-faceted ethe (Trump as himself, Trump as President of the US states) are no longer superimposable, it becomes clear that by reinforcing one, he weakens the other; by flattering his unconditional supporters, he scandalizes and probably further alienates most citizens, who look at his lack of action, his lack of empathy, and his lack of political sense in disbelief. Is this intended? This question is crucial since the intention is important in contemporary mainstream pragmatics. It is scientifically impossible to answer this question, as one cannot ascertain the presence of an intention in a speaker’s mind. Still, the effect of the decisions made by Trump—giving an image of the supporters, silencing the death of people in the Capitol, and forgiving the actions of his supporters—does serve to ground (weak) inferences regarding Trump’s ethos, not only for a discourse analyst but also for citizens who follow the events as they unfold. Of course, in rhetoric, ethos is consciously built by the speaker to persuade it, but “the ability to see what is possibly persuasive in every given case” (according to Aristotle’s famous definition of the rhetoric) doesn’t imply strategically controlling these means.

A contrario ethos and borrowed ethos are indirect ethoses associated with the pronouns he/she/they, that is to say, people who are not in the interaction but are evoked in the speech. If the quoted or mentioned person appears to be neutral or opposed to the speaker, I label it as a contrario ethos; if the person is shown as supporting the speaker’s words, I label it as borrowed ethos. In the latter case, the endorsement of stars in advertisements is a way of building the ethos of a brand through the image of the endorsing person, for example. Prosopopeia is a rhetorical device typically associated with borrowed ethos while quoting out of context or using the straw man fallacy will often be associated with a contrario ethos. We have already analyzed an example of a contrario ethos based on Mike Pence’s image in Trump’s latest tweets. Asking Mike Pence to perform an act of extreme courage is apparently building a contrario the image of Trump as potentially proud of his vice-president, confident of Pence’s loyalty and sense of self-sacrifice. When, later, Pence did not do what he was expected to do (according to Trump’s vision), the President treats him as a coward violating his sense of duty: “Mike Pence didn’t dare to do what should have been done to protect our country and our Constitution, giving States a chance to certify a corrected set of facts, not the fraudulent or inaccurate ones which they were asked to previously certify” (6 January 2021, 2:04 p.m.). A contrario, Trump’s ethos is that of a betrayed man, accompanied by a weakling, probably disappointed in the lack of support from his right-hand man, and who feel reinforced in his ethos of being treated unfairly. Community ethos of the country and the constitution, “not protected”, allows him to avoid the image of a personal quest for power and instead highlights the image of a man motivated by an ideal: the country he is supposed to protect.

It should be noted that this last image is not consistent with the rest of his messages from that afternoon, where the fate of the institutions was of little importance to him. A contrario ethos is frequently used in Trump’s tweets, as the former President is known for his offensiveness (). In the corpus, he is taunting, for example, the NBC journalist Chuck Todd: “Sleepy Eyes Chuck Todd is so happy with the fake voter tabulation process that he can’t even get the words out straight. Sad to watch!” 6 January 2021, 08:45 a.m.). Nicknaming opponents is a trademark of President Trump: “Donald Trump regularly used nicknames to deride his opponents’ appearances, demeanors, beliefs, or personal histories” (). One can infer from this nickname of “Sleepy Eyes” his propensity to publicly mock the physical characteristics of people he dislikes, in the same way that he mocks a form of stammering in this tweet. He shows an ethos of shamelessness in judging people, resorting to ad personam attacks while ignoring ethics or respect for people. He also confirms an ethos of breaking with the language expected of presidents; the fact that he says what he is thinking is often praised by the President’s supporters14.

Borrowed ethos is rarer in the corpus. A very paradoxical borrowed ethos can be found in the corpus when Trump “praises” Mexico: “Even Mexico uses Voter I.D.” (6 January 2021, 09:36 a.m.). While it must be technically considered a borrowed ethos, because he praises a country with a more advanced electoral protocol than the American one, it is only half-hearted praise: “Even Mexico” presupposes (in a classic conventional implicature) that Mexico was the least supposed to be more advanced than US: Trump confirms here a prior ethos of despising against Mexico and Mexicans which was obvious in his famous announcement speech15. Added to the contempt for Mexico is a form of dismay at the American electoral system, described in another tweet, a quarter of an hour earlier, as “worse than that of third world countries!” (6 January 2021, 09:00 a.m.)—which again reinforces the ethos of American superiority and contempt for less developed countries. The only unequivocal example of borrowed ethos from the corpus is the following one, already mentioned above: “[…] @sendavidperdue (a great guy)”. Mentioning people we like is also a way of building ethos: the values, actions, and other speeches of the person being praised can be seen as close to the person who praises. Now, confronting this discursive ethos with the situational one, it can be noted that this is not the first time that Trump has used the phrase ‘great guy’ in his tweets. And, when it comes to the American political celebrities, Trump regularly mentions, they are first and foremost very loyal supporters of Donald Trump. Such an attitude is another clue that confirms the narcissistic ethos that many psychologists diagnosed16. Praising people whose adulation for Trump is manifest reduces the value or the authenticity of the praise. Again, we cannot suspect that Trump intended to confirm the narcissistic ethos. It is only the confrontation I made as a discourse analyst between intertextuality and this tweet that gives some substance to this interpretation.

Finally, the neutralized ethos is that of third parties quoted without any speaker’s judgment about it. The journalist delivering facts or the scientist describing findings are typically inclined to use this ethotic form. The absence of involvement on the part of the speaker does not imply, however, that the speaker’s image is not created, still according to the hypothesis that ethos is consubstantial with the act of saying. It may be an ethos that marks a certain seriousness, or that aims to let facts or truth speak for themselves without the need to take sides for the speaker. By default, raw assertions are considered facts () and give a connotation of probity to the speaker. Thus, one might be legitimately troubled when Trump asserts in a factual mode: “They just happened to find 50,000 ballots late last night” (6 January 2021, 9:00 a.m.) or “The States want to redo their votes” (6 January 2021, 9:15 a.m.)—two facts that turn out to be false or, at least, never substantiated. But Trump is in a position to know these kinds of facts, and stating them may be believable, despite his reputation as a serial liar. The neutralized ethos of a messenger may fuel the anger of people who still believe that the election was stolen, that “a sacred landslide election victory is […] unceremoniously & viciously stripped away from great patriots” (6 January 2021, 6:01 p.m.). The image of an unfairly treated president, despite the alleged existence of “facts” that are supposed to prove that the election was rigged can be strengthened by the rhetorical strategy of a neutralized ethos.

4. Conclusions: A Fragile Tool for Pragmatics, an Interesting Tool for Discourse Analysis

In these lines, we see that a multi-faceted ethos (i) is built through probably intended rhetorical strategies or unintended effects of what has been said, (ii) can be built thanks to an entailment (“we are proud” implies “I am proud”) or to a weak implicature, (iii) can be founded on different ostensive signs (verbal or non-verbal communication, prosody, etc.). This may give rise to an impression of a catch-all category. My response will be two-fold, alluding to the two keywords of this special issue: argumentation and pragmatics.

First, regarding pragmatics, I would like to show how the ethotic construction responds to different principles of relevance theory, in my view (I do not consider myself an advocate of this theory, but I am convinced by the inferential model based on the idea of a degree of manifestness of what has been communicated). Then, regarding argumentation, I would like to discuss some results of this methodological proposition.

() states some assumptions which are essential to my eyes for the issue of analyzing ethos (I underline the crucial aspects of this quotation): “a. The communicator’s informative intention is an intention to modify the audience’s cognitive environment—that is, their possibilities of thinking—rather than directly affecting their thoughts. b. In recognizing the communicator’s informative and communicative intentions, the audience must necessarily go beyond them. c. Communication is not a yes-no matter but a matter of degree. d. In the case of weak communication, much of the responsibility for constructing a satisfactory interpretation falls on the audience’s side.”. The highlighted elements are completely congruent with what has been done here. The ethos of a speaker is a specific cognitive environment devoted to or specialized in assessing a speaker and fed by different inferences—weak or strong, intended or not, established by comparison or not with previous contexts or social stereotypes. The responsibility of the discourse analyst is to justify how relevant the ethos that they bring out of the observed text is, according to a principle exposed by () in the same paper: “What relevance theory aims to do is not to produce better interpretations than actual hearers or readers do, but to explain how they arrive at the interpretations they do construct”.

The notion of weak communication is particularly useful in literary or stylistic interpretation since, as shown by (), the responsibility for drawing weak implicatures is more on the hearer’s (or the analyst’s) side, making them optional and not necessarily foreseeable by the speaker.

In this sense, a theoretical conclusion of this paper is to defend that the inferential processes depicted here are weak implicatures and belong not only to the rhetorical sphere but also to the pragmatic sphere in the broad sense, which, to my knowledge, has never been stated in these terms.

Analyzing ethos may appear as opening Pandora’s box, especially since the typology shown in (), may already appear to be overwhelming. I intended to compartmentalize different aspects of what constitutes the speaker’s image in order to have a better vision of what it covers and also to describe a tool that I hope is encompassing enough to cope with different texts. This does not exclude interpretations that are sometimes fragile, personal, and possibly debatable, but the approach taken here to analyze Donald Trump’s tweets during the assault on the Capitol is always aimed at highlighting why it seems relevant to interpret the image of the American President in this way. Regarding argumentation, the process highlighted here is indeed highly inferential since it tries to show how one could conclude a judgment on the speaker’s character. But the fact that this process falls completely on the audience’s side—to quote Wilson—is not plainly within the realm of argumentation, classically defined as a “set of claims in which one or more of them—the premises—are put forward to offer reasons for another claim, the conclusion” (). The conclusion and the major premise are implicit in the ethotic evaluation of the speaker: the audience takes the situational ethos they inherit and merge it with the discursive ethos of the occasion, observing the shown ethos and the said ethos to arrive at an ethotic conclusion about the speaker17. In this respect, it is more an ethotic reasoning whose existence is only cognitive than an argumentative reconstruction of a text. The cognitive nature of this reasoning is why it could be interesting to develop some experimental studies from what has been sketched here, even if the diversity of parameters will be hard to master for an experimental design. I wonder if it could be interesting to test the difference between individual and community ethos or between borrowed and neutralized ethos, for example. More research on the process of the character judgment that interested Douglas Walton could be done: since we all easily judge other people—it could be considered as a claim or a conclusion—and since this judgment is grounded in some communicational clues—functioning as premises or data—it is the warrant in ’s () terms which is at the center of the inquiry. And this warrant can look like a black box—mainly because I’m not sure that we are very aware of its importance: it takes one-tenth of a second to judge someone according to psychological studies of first impressions (). And I think that many persons asked to justify their judgments about a character would explain it by their “feelings” or “intuitions”. A dialog with such works in psychology and social cognition can lead to fruitful further research about the formation of a judgment of trust: I tried to shed some light on this black box as a discourse analyst, but it is probably only scratching the surface of different problems that only interdisciplinarity research could better tackle.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | See also () about the circularity of sentences like “I am credible”. |

| 2 | Note that () considers that conversational implicatures are inferences to the best explanations (or abductions). It goes along with the idea I develop later: ethos can be considered as a form of implicature, in a non-Gricean sense though. |

| 3 | “An ethotic argument does not establish the ethos of the author of this argument, but it aims to use other speakers’ ethos to infer the content of what they said or to infer that the content should not be accepted” (). |

| 4 | I thank one of my reviewers for the references that were not mentioned in the first version of this paper. |

| 5 | In “Identité et discours” () offer a methodological approach to discursive ethos which can be considered as a tool to guide the interpretation of ethos, based on different theories and sources, whereas my approach is more focused on the interpretative process itself. |

| 6 | This partially echoes Oswald ’s () distinction between L et λ, the speaker as a human being and the speaker as a speaker. For him, shown ethos is associated to L (as the speaker) while said ethos is about λ (the human being about whom L is talking). This theory is called into question here (see Section 3). |

| 7 | |

| 8 | https://theconversation.com/trumps-dangerous-narcissism-may-have-changed-leadership-forever-151184 (accessed on 5 June 2022). |

| 9 | news.berkeley.edu/2020/12/07/despite-drift-toward-authoritarianism-trump-voters-stay-loyal-why/ (accessed on 5 June 2022). |

| 10 | Note that speakers may occasionnally refer to multiple specific ethoses. For example, these words of a physician in a TV interview: “I’m a little embarrassed to answer you: either I answer you as a citizen, or I answer you as a doctor” (my translation: https://www.programme-television.org/news-tv/Michel-Cymes-sur-le-suicide-assiste-Je-suis-un-peu-embete-pour-vous-repondre-VIDEO-4677528) (accessed on 5 June 2022). |

| 11 | https://www.nytimes.com/2021/12/13/business/media/fox-news-trump-jan-6-meadows.html (accessed on 5 June 2022). |

| 12 | Which is, by the way, legally and constitutionnaly impossible. |

| 13 | He already concluded a video during the events by “We love you. You’re very special”. |

| 14 | https://www.bbc.com/news/av/election-us-2016-36493678 (accessed on 5 June 2022). |

| 15 | “When Mexico sends its people, they’re not sending their best. […] They’re sending people that have lots of problems, and they’re bringing those problems with us. They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists. And some, I assume, are good people” (16 June 2015) (https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-fix/wp/2017/06/16/theyre-rapists-presidents-trump-campaign-launch-speech-two-years-later-annotated/ (accessed on 5 June 2022)). |

| 16 | |

| 17 | This summary must be attributed to one of the anonymous reviewers of this paper. I thank them both for their careful reading and their precious suggestions. |

References

- Allott, Nicholas. 2018. Conversational Implicature. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Linguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amossy, Ruth, ed. 1999. Images de soi dans le discours: La construction de l’ethos. Lausanne: Delachaux et Niestlé. [Google Scholar]

- Amossy, Ruth. 2010. La présentation de soi: Ethos et Identité Verbale. Paris: PUF. [Google Scholar]

- Aristotle. 1926. Aristotle in 23 Volumes. Translated by J. H. Freese. Harvard University Press: Cambridge and London: William Heinemann Ltd., vol. 22. [Google Scholar]

- Baumlin, James S., and Peter L. Scisco. 2018. Ethos and its Costitutive Role in Organizational Rhetoric. In The Handbook of Organizational Rhetoric and Communication. Edited by Øyvind Ihlen and Robert L. Heath. Chichester: Wiley Blackwell, pp. 202–13. [Google Scholar]

- Bonnafous, Simone. 2002. La question de l’ethos et du genre en communication politique. Actes Du Premier Colloque Franco-Mexicain En Information et Communication. Available online: https://edutice.archives-ouvertes.fr/edutice-00000362/document (accessed on 5 June 2022).

- Brinton, Alan. 1986. Ēthotic argument. History of Philosophy Quarterly 3: 245–58. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Penelope, and Stephen C. Levinson. 1987. Politeness: Some Universals in Language Usage. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Budzynska, Katarzyna, Marcin Koszowy, and Martin Pereira-Fariña. 2021. Associating Ethos with Objects: Reasoning from Character of Public Figures to Actions in the World. Argumentation 35: 519–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budzynska, Katazyna. 2013. Circularity in ethotic structures. Synthese 190: 3185–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chaiken, Shelly. 1980. Heuristic versus systematic information processing and the use of source versus message cues in persuasion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 39: 752–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charaudeau, Patrick. 2005. Le Discours Politique: Les Masques du Pouvoir. Paris: Vuibert. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, Billy. 2013. Relevance Theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Clément, Fabrice. 2010. To Trust or not to Trust? Children’s Social Epistemology. Review of Philosophy and Psychology 1: 531–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corcoran, Katja, Tanja Hundhammer, and Thomas Mussweiler. 2009. A tool for thought! When comparative thinking reduces stereotyping effects. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 45: 1008–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cornilliat, Françoise, and Richard Lockwood, eds. 2000. Ethos et Pathos: Le Statut du Sujet Rhétorique: Actes du Colloque International de Saint-Denis (19–21 juin 1997). Paris: Honoré Champion. [Google Scholar]

- Doury, Marianne, and Pierre Lefébure. 2006. « Intérêt Général», «Intérêts Particuliers». La construction de l’ethos dans un débat public. Questions de communication 9: 47–71. [Google Scholar]

- Druetta, Ruguero, and Paola Paissa. 2020. Éthos discursif, éthos préalable et postures énonciatives. Corela. (online) HS-32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducrot, Oswald. 1984. Le Dire et le Dit. Paris: Editions de Minuit. [Google Scholar]

- Duthie, Rory, Katarzyna Budzynska, and Chris Reed. 2016. Mining Ethos in Political Debate. COMMA 287: 299–310. [Google Scholar]

- Eco, Umberto. 1992. Les Limites de L’interprétation. Translated by M. Bouzaher. Paris: Grasset. [Google Scholar]

- Enli, Gunn. 2017. Twitter as arena for the authentic outsider: Exploring the social media campaigns of Trump and Clinton in the 2016 US presidential election. European Journal of Communication 32: 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Errecart, Amaia. 2019. De la sociabilité associative: Formes et enjeux de la construction d’un ethos collectif. Mots. Les Langages du Politique 121: 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flowerdew, John, and John E. Richardson, eds. 2018. The Routledge Handbook of Critical Discourse Studies. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons, Alison, and Sara Whiteley. 2018. Contemporary Stylistics: Language, Cognition, Interpretation. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman, Erving. 1973. La présentation de soi. Paris: Les Editions de Minuit. [Google Scholar]

- Govier, Trudy. 1997. Social Trust and Human Communities. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Govier, Trudy. 1998. Dilemmas of Trust. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Govier, Trudy. 2013. A Practical Study of Argument: Enhanced Edition, 8th ed. Belmont: Wadsworth, Cengage Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Grimminger, Lara, and Roman Klinger. 2021. Hate Towards the Political Opponent: A Twitter Corpus Study of the 2020 US Elections on the Basis of Offensive Speech and Stance Detection. arXiv arXiv:2103.01664. Available online: http://arxiv.org/abs/2103.01664 (accessed on 5 June 2022).

- Hatano-Chalvidan, Maude, and Denis Lemaître. 2017. Identité et discours: Approche méthodologique de l’ethos discursif. Caen: Presses Universitaires de Caen. [Google Scholar]

- Herman, Thierry. 2001. «Le Président est mort, vive le Président». Images de soi dans l’éloge funèbre de François Mitterrand par Jacques Chirac. In La mise en scène des valeurs. Edited by Marc Dominicy and Madeleine Frédéric. Lausanne: Delachaux et Niestlé, pp. 167–202. [Google Scholar]

- Herman, Thierry. 2005. L’analyse de l’ethos oratoire. In Des discours aux textes: Modèles et analyses. Edited by Philippe Lane. Mont-Saint-Aignan: Presses universitaires de Rouen et du Havre, pp. 157–82. [Google Scholar]

- Hovland, Carl I., Irving L. Janis, and Harold H. Kelley. 1953. Communication and Persuasion; Psychological Studies of Opinion Change. New Haven: Yale University Press, pp. xii, 315. [Google Scholar]

- Ismagilova, Elvira, Emma Slade, Nripendra P. Rana, and Yogesh K. Dwivedi. 2020. The effect of characteristics of source credibility on consumer behaviour: A meta-analysis. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 53: 101736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jacquin, Jérôme. 2018. Ethos and Inference: Insights from a Multimodal Perspective. Edited by Steve Oswald and Didier Maillat. London: College Publications, vol. 2, pp. 413–23. [Google Scholar]

- Jeffries, Lindsay. 2010. Critical Stylistics: The Power of English. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Tyler. 2021. Sleepy Joe? Recalling and Considering Donald Trump’s Strategic Use of Nicknames. Journal of Political Marketing 20: 302–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kedia, Gayannée, Thomas Mussweiler, and Dennis E. J. Linden. 2014. Brain mechanisms of social comparison and their influence on the reward system. NeuroReport 25: 1255–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Krieg-Planque, Alice. 2019. L’ethos de rupture en politique: «Un ouvrier, c’est là pour fermer sa gueule!», Philippe Poutou. Argumentation et Analyse du Discours 23: 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lehti, Lotta. 2013. Genre et ethos: Des voies discursives de la construction d’une image de l’auteur dans les blogs de politiciens. Turku: Université de Turku. [Google Scholar]

- Maingueneau, Dominique. 2002. Problèmes d’ethos. Pratiques 113: 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maingueneau, Dominique. 2013. L’èthos: Un articulateur. COnTEXTES. Revue de Sociologie de la Littérature 13: 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maingueneau, Dominique. 2014. Retour critique sur l’éthos. Langage et Societe 149: 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzarella, Diana. 2021. “I didn’t mean to suggest anything like that!”: Deniability and context reconstruction. Mind and Language. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Keefe, Daniel J. 2016. Persuasion: Theory and Research, 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Peirce, Charles S. 1932. Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce: Vol. II: Elements of Logic. Edited by Charles Hartshorne and Paul Weiss. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard Univ. Press. [Google Scholar]

- Reid, Thomas. 1970. An Inquiry into the Human Mind. Edited by Timothy Duggan. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, Andrew S., and Daniel Caldwell. 2020. ‘Going negative’: An APPRAISAL analysis of the rhetoric of Donald Trump on Twitter. Language and Communication 70: 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandré, Marion. 2014. Ethos and interaction: An analysis of the political debate between Franȱis Hollande and Nicolas Sarkozy. Langage et Societé 149: 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperber, Dan, and Deirdre Wilson. 1986. Relevance: Communication and Cognition. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Sperber, Dan, Fabrice Clément, Christophe Heintz, Olivier Mascaro, Hugo Mercier, Gloria Origgi, and Deirdre Wilson. 2010. Epistemic Vigilance. Mind & Language 25: 359–93. [Google Scholar]

- Stacks, Don W., Michael B. Salwen, and Kristen C. Eichhorn. 2019. An Integrated Approach to Communication Theory and Research. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Toulmin, Stephen. 2003. The Uses of Argument, Updated ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. First Published in 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Walton, Douglas N. 1999. Ethotic arguments and fallacies: The credibility function in multi-agent dialogue systems. Pragmatics & Cognition 7: 177–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Walton, Douglas N. 2006. Character Evidence: An Abductive Theory. Dordrecht: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Willis, Janine, and Alexander Todorov. 2006. First Impressions: Making Up Your Mind After a 100-Ms Exposure to a Face. Psychological Science 17: 592–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, Deirdre, and Robyn Carston. 2019. Pragmatics and the challenge of ‘non-propositional’ effects. Journal of Pragmatics 145: 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wilson, Deirdre. 2012. Relevance and the interpretation of literary works. In Observing Linguistic Phenomena: A Festschrift for Seiji Uchida. Tokyo: Eihohsha, pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, Elizabeth J., and Daniel L. Sherrell. 1993. Source effects in communication and persuasion research: A meta-analysis of effect size. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 21: 101–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wodak, Ruth, and Michael Meyer, eds. 2016. Methods of Critical Discourse Analysis, 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).