Abstract

In the first two decades following Ross’s Constraints on Variables in Syntax, a picture emerged in which the Mainland Scandinavian (MS) languages appeared to systematically evade some of the locality constraints proposed by Ross, including the relative clause (RC) part of the complex NP constraint. The MS extraction patterns remain a topic of debate, but there is no consensus as to why extraction from RCs should be so degraded in English (compared to MS)—or why it should be so acceptable in MS (compared to English). We present experiment results which indicate that English should be counted among the languages that allow extraction from RCs in at least some environments. Our results suggest a negligible island effect for RCs in predicate nominal environments and a substantially reduced island effect for those in canonical existential environments. In addition, we show that the size of the island effect resulting from extraction from an RC under a transitive verb is substantially reduced when the transitive verb is used to make an indirect existential claim. We present arguments that patterns of RC sub-extraction discovered in Mainland Scandinavian languages are mirrored in English, and we highlight methodological innovations that we believe may be useful for further investigation into this and other topics.

1. Introduction

The empirical landscape related to islands and island sensitivity has been gradually shifting since the first discoveries of islands, occasioning new ideas about the general source of island sensitivity, as well as the nature of particular violations. An example of this shift, and the focus of our study, is relative clauses (henceforth RCs), long considered strong islands for extraction1. In the first two decades following Ross (1967), a picture emerged in which the Mainland Scandinavian (MS) languages appeared to systematically evade some of the locality constraints proposed by Ross, including the relative clause (RC) part of the complex NP constraint; research into extraction from RC in MS has consistently shown a selective pattern of acceptable extraction, where RCs in some linguistic environments, but not all, facilitate extraction from the RC (Erteschik-Shir 1973; Erteschik-Shir and Lappin 1979; Allwood 1976, 1982; Maling and Zaenen 1982; Taraldsen 1981, 1982). While the MS extraction patterns, and their proper analysis, is a topic of debate (Engdahl 1997; Kush et al. 2013, 2019; Lindahl 2017; Müller 2014, 2015), it remains a mystery why extraction from RCs should be so degraded in other languages (compared to MS). It is also not yet fully clear why it would be more degraded in some linguistic environments, a distribution which has sometimes suggested that the theory of locality be defined at least in part in terms of information structure, or processing limitations and constraints on working memory (Ambridge and Goldberg 2008; Erteschik-Shir 1973; Hofmeister and Sag 2010; Kluender 1992; Kluender and Kutas 1993; Kuno 1987). A pressing set of empirical questions therefore emerges regarding the extent of variation across both of these dimensions: across languages, and within a language, across linguistic environments. To the extent that some languages, such as the MS languages, show a selective pattern of extraction from RCs, the question we address is whether these environments vary across languages. We focus on English and present experimental evidence for acceptable extraction from English RCs. As we show, the environments in which extraction is most acceptable in English bear a significant resemblance, if not full identity, to environments identified in other languages. Based on this pattern we suggest that RCs in English are weak islands, exactly as in MS and in Hebrew (Nyvad et al. 2017; Lindahl 2014, 2017; Sichel 2018), and that strong island effects arise only in a subset of environments, which we define as presuppositional DPs. Some have argued that RCs which allow sub-extraction are to be characterized in information-structural terms such as backgroundedness or presupposition (Erteschik-Shir 1973, 1982; Ambridge and Goldberg 2008; Engdahl 1982; Löwenadler 2015). Sichel (2018) argues that the external factors that govern extraction from an RC are no different from those that govern extraction from ordinary DPs: the DP from which extraction takes place must be non-presuppositional.

Presuppositional noun phrases are noun phrases whose denotations have already been introduced into the discourse, sometimes also referred to as given. Their referents are presupposed to exist at the point at which the sentence is presented, and the containing sentence asserts that something holds of the referent designated by the presuppositional NP. In contrast, the NP in the pivot of an existential statement, bracketed in (1a), is non-presuppositional, since the sentence is introducing the referent into the discourse, by asserting that it exists. Similarly, the predicative NP following the copula, bracketed in (1b), is also non-presuppostional, since it does not even denote an individual, let alone a presupposed one.

- (1)

- There were [posters of the Republican candidate] all over town.

- Jane Smith was [a good candidate for the job].

There is significant consensus in the literature that extraction from simple NPs, in languages such as English, which allow it, is limited to non-presuppositional NPs (sometimes called non-specific indefinites or non-given NPs; Bianchi and Chesi 2014,Diesing 1992,Fiengo and Higginbotham 1981). For example, it is easier to extract from a non-presuppositional NP in an existential construction than from a presuppositional NP in an ordinary clause Moro 1997, in (2). The correlation between presuppositionality and sub-extraction is further observed within the class of direct objects, in the distinction between weak and strong quantifiers (Milsark 1974). NPs with weak quantifiers, such as many or few, are allowed in the existential construction, whereas NPs with strong quantifiers, such as each or most, are excluded, in (3). When in direct object position, the former permit sub-extraction much more readily than the latter, in (4).

- (2)

- Which candidate1 were [TP there T [vP posters of t1] all over town]?

- *Which candidate1 were [TP [posters of t1]2 T [vP all over town]]?

- (3)

- There were (many/several/few) pictures of Mary on the wall.

- *There was the/every/each picture of Mary on the wall.

- (4)

- Who did you see a picture of?

- Who did you see many/several/few pictures of?

- *Who did you see the/each picture of?

- *Who did you see most pictures of?

In the languages in which it has been attested, extraction from RCs seems to follow a similar, if not identical, pattern. Beyond the known cases in MS, additional acceptable cases of overt extraction from RCs have been attested over the years, in Italian (5a, 7c), Spanish, French, and in Hebrew (5d, 6, 7d). These have been observed in particular environments: when the RC is the pivot of an existential construction, in (5), when the RC is a predicate nominal, in (6), and when the RC is the direct object of an existential-like transitive construction, dubbed Evidential Existential by Rubovitz-Mann (Erteschik-Shir 1973; Rubovitz-Mann 2000, 2012), in (7).2 And, despite history and appearances, there are reasons to doubt whether English deserves its reputation as a language whose RCs are always strong islands. Instances of extraction in English have surfaced sporadically in the literature, over the years, and they seem to track the same environments, at least impressionistically, as seen in (8a, 8b, 8c) (Chung and McCloskey 1983; Kuno 1976; McCawley 1981).

- (5)

- Det er der mange der kan lide.that are there many who like‘There are many who like that’. (Danish; Erteschik-Shir and Lappin 1979, p. 55)

- Det språket finns det många som talar.that language exist it many that speak‘There are many who speak that language’. (Swedish; Engdahl 1997, p. 13)

- Ida, di cui non c’è nessuno che sia mai stato innamorato …‘Ida, whom there is nobody that was ever in love with, …’(Italian; Cinque 2010, p. 83)

- Al lexem Saxor, yeS rak gvina axat Se-keday limraox.on bread black be only cheese one that-worthy to.spread‘On black bread, there is only one cheese that’s worth spreading’.(Hebrew; Sichel 2018, p. 357)

- (6)

- Al ha-haxlata ha-zot, yair lapid haya ha-axaron Se-yadaabout the-decision this, Yair Lapid was the-last that-knew‘About this decision, Yair Lapid was the last to know’. (Hebrew)

- (7)

- Det kender jeg mange der kan lide.that know I many who like‘That I know many who like’. (Danish; Erteschik-Shir and Lappin 1979, p. 55)

- [En sådan frisyr] har jag aldrig sett någon som ser snygg ut i.that such hairstyle have I never seen anyone who looks good in‘That kind of hairstyle, I have never seen anyone who looks good in’.(Swedish; Engdahl 1997, p. 24)

- Giorgio, al quale non conosco nessune che sarebbe disposto ad affidare i propri risparmi …‘Giorgio, whom I don’t know anybody that would be ready to entrust with their savings …’(Italian; Cinque 2010, p. 83)

- Me-ha-sifria ha-zot, od lo macati sefer exad Se-keday le-haS’ilfrom-the-library this yet not found.I book one that-worth to.borrow‘From this library, I haven’t yet found a single book that’s worth borrowing’.(Hebrew; Sichel 2018, p. 358)

- (8)

- This is the child who there is nobody who is willing to accept.(English; Kuno 1976, p. 423)

- This is the one that Bob Wall was the only person who hadn’t read.(English; McCawley 1981, p. 108)

- That’s one trick that I’ve known a lot of people who’ve been taken in by.(English; Chung and McCloskey 1983, p. 708)

The goal of this study is to confirm this impression experimentally, by systematically manipulating these three contexts: pivot of an existential, predicate nominal, and object of an existential-like construction. To the extent that we find that the pattern of extraction in English replicates the pattern in Scandinavian, Romance, and Hebrew, we will have provided new evidence for the weak island status of English RCs; and we will also have provided new evidence for the cross-linguistically uniform relationship between the presuppositional status of the containing NP and strong islandhood. In a recent study of acceptable extraction from English RCs, Christensen and Nyvad (2022) examine whether English speakers show some of the same selective patterns of RC extraction that speakers of Scandinavian languages do, including sensitivity to lexical frequency, improvement over trials, and a preference for topicalization over wh-extraction. They reason that selectivity with respect to extraction suggests that RCs are weak islands, as has been argued for MS, since weak islands allow extraction, selectively. Since they do not find the same effects in English, they conclude that in English, RCs are strong islands, blocking all extraction categorically. By the same token, the finding that English sub-extraction tracks the presuppositionality of the NP as in other languages will suggest (a) that English RCs are no different, with respect to islandhood, from Scandinavian, Romance, and Hebrew, and (b) that English RCs are weak islands. Furthermore, the effect of presuppositional NPs on sub-extraction, observed with simple NPs as well, can be attributed to a strong island, however analyzed (see Diesing 1992 and Sichel 2018 for an implementation in terms of syntactic position). We return to discuss the theoretical implications of this generalization in the conclusions, where we spell out the consequences for recent ideas about acceptable extraction from NP islands (Abeillé et al. 2020; Kush et al. 2019). This paper is organized as follows: Section 2 introduces the study of islands in experimental syntax; Section 3 describes the experiments; Section 4 is the discussion of our results and their potential implications; and Section 5 concludes.

2. Experimental Syntax of Islands

Islands are typically complex syntactic environments, embedded in complex syntactic environments, or both. This makes it a challenge to interpret the acceptability of a sentence containing an extraction from a purported island, because any judgment of acceptability is affected not only by how island-specific constraints affect grammaticality but also by any general contributors to the complexity of the sentence that affect parsability. In this study, we follow the design strategy first devised by Sprouse (2007), and elaborated in Sprouse et al. (2012), which uses a factorial experimental design to decompose the acceptability of an island extraction first into any plausible contributors to degraded acceptability that are not specific to island extraction, and then into how much is “left over” for an island constraint to explain.

We illustrate this approach with a whether-island in English, as in (9). Imagine a controlled acceptability judgment experiment in which participants assigned ratings to sentences along a 1–6 Likert-type scale, where 1 is least acceptable and 6 is most acceptable. Suppose that sentences such as (9) received, on average, a rating of 2.

- (9)

- What do you wonder whether John bought?

This is a low rating, which could be attributed to a grammatical constraint that is violated by extracting the what phrase across whether. However, other characteristics of (9) could lead to degraded acceptability, including the mere presence of a whether-clause complement and the fact that a long filler-gap dependency spans two clauses. Neither of these characteristics alone violates a grammatical constraint, but each independently increases the syntactic or semantic complexity of the sentence and each thus plausibly decreases its overall acceptability. If instead of measuring the acceptability of only island-containing sentences (9), we also measure the acceptability of related sentences, then we can estimate and account for these independent contributions to acceptability.

The set of sentences in (10) realizes a 2 × 2 factorial design that relates sentences along two relevant dimensions: Dependency Length (Short, Long) and Structure (Island, Non-Island). Square brackets mark the potential island domain, and an underscore marks the gap site; hypothetical average ratings are given in angle brackets in the right margin. Notice that (10d), in the Long, whether-clause condition, is just (9).

- (10)

- Short, that-clauseWho thinks that John bought a car?

- Long, that-clauseWhat do you think that John bought ?

- Short, whether-clauseWho wonders [whether John bought a car]?

- Long, whether-clauseWhat do you wonder [whether John bought ]?

Ratings from sentences that follow the design in (10) can be used to isolate effects that are specific to extraction from an island. The ratings difference (10a)–(10b) shows that there is a cost of processing a long-distance dependency on acceptability: 6 − 4 = 2. The ratings difference (10a)–(10c) gives the acceptability cost of embedding via wonder whether vs. think that: 6 − 5 = 1. Adding these two costs together, 2 + 1 = 3, lets us predict how degraded the acceptability of (10d) should be relative to (10a), if it were only due to the independent costs of Dependency Length and Structure. Under a hypothesis of independent costs, then we should expect (10d) to receive an average rating of 3, i.e., 6 – 3. But the average rating of (10d) indicates that we have an unexplained deficit: it is one point lower than predicted. This 1-pt “deficit” provides an estimate of the island effect.

Sprouse et al. (2012) used the term ‘DD score’, as in difference of differences, to refer to how much more was needed to explain the low acceptability of an island-containing sentence. In designs such as (10) that manipulate a Length factor with some Structure factor that has Simple and Complex levels, such as Non-Island and Island in the example above, the DD score is always defined as the differences between D1 and D2, where D1 represents Long Simple–Long Complex, and D2 represents Short Simple–Short Complex. This yields a measure that is easy to interpret: if there is an island effect, DD will be positive. In the example above, DD = 1. The presence of an island effect is thus traced to a superadditive interaction, one which can be statistically represented by a regression of the ratings measure on the experimental factors.

The DD score method has been used to test a wide range of island types and languages other than English, including Japanese (Sprouse et al. 2011), Brazilian Portuguese (Almeida 2014), Italian (Sprouse et al. 2016), Hebrew (Keshev and Meltzer-Asscher 2018), Slovenian (Stepanov et al. 2018), Norwegian (Kush et al. 2018, 2019), and Modern Standard Arabic (Tucker et al. 2019). Kush et al. (2018) used a design comparable to (10) to investigate adjunct islands, whether islands, subject islands, complex NP islands, and—crucially—RC islands in Norwegian. They found that all island types were characterized by a superadditive interaction, i.e., positive DD score, and that the size of the interaction was comparable across subject, adjunct, complex NP and RC islands; it was smaller for whether islands, for which the researchers found considerable inter-speaker variation.

Given the discussion above about the often-observed permeability3 of RCs in MS, the fact that Kush et al. (2018) found an island effect in Norwegian RCs is highly relevant. However, it does not necessarily contradict the observations above, because they did not systematically manipulate the embedding environment to include positions known to “unlock” the island, such as predicate nominal or existential pivot positions. Instead, the RCs appear to be in the complement position of prepositions and transitive verbs. The set of sentences in (11) below illustrates one of their RC item sets, which crosses Length (11a/11c vs. 11b/11d) and Structure (11a/11b vs. 11c/11d). Observe that the RC is in the complement position of a preposition, in snakket med ‘speak with’ (11c/11d).4 Their results provide evidence that RCs, in that environment, are islands for extraction in Norwegian.

- (11)

- Hvem trodde at et par kritikere hadde stemt på filmen?who thought that a few critics had voted for film.def`Who thought that a few critics had voted for the film?’

- Hva trodde regissøren at et par kritikere hadde stemt på ?what thought director.def that a few critics had voted for`What did the director think that a few critics had voted for?’

- Hvem snakket med et par kritikere [ @ som hadde stemt på filmen]?who spoke with a few critics that had voted for the film.def?`Who spoke with a few critics that had voted for the film?’

- Hva snakket regissøren med et par kritikere [ @ som hadde stemt på ]?what spoke director.def with a few critics that had voted for`What did the director speak with a few critics that had voted for?’

In a later paper, Kush et al. (2019) also investigated extraction from RCs, but this time, the dependency was not a wh-question, as in (11), but topicalization. While they found generally smaller DD scores in this experiment, they nonetheless found a positive and significant island effect for topicalization out of RCs.

The key insight from this research is that we can capitalize on a factorial design to experimentally define an island effect. It is important to make a few provisos, however, about this design. Generally these experiments all cross the factors of Length and Structure, representing the island effect as their interaction. But note that these factors are merely convenient labels for a general design strategy: what they refer to depends on the experiment in question, as the position and nature of the island under consideration varies. Length sometimes, but not always, refers also to position of the gap: this is because the shortest dependency often places a gap in matrix subject position (as in 11a/11c above). Structure usually refers to the presence or absence of the island but this is then usually conflated with other lexical items. Thus, in (10), changing from a that to a whether complement necessitates changing the embedding verb (think, versus wonder). Likewise, in (11), changing from a CP to a DP complement necessitates changing the embedding verb “think” to “speak with”. Therefore, some consideration must be given to how Length and Structure are realized in any given experiment and—crucially—whether the comparison across levels fairly defines a contrast related to the island constraint in question.

A second proviso concerns statistical interactions. In acceptability judgment experiments, participants are usually making their responses on a rating scale where each number on the scale is essentially meaningless other than it defines an order of “goodness” (or “badness”). On a typical 1–6 Likert-type scale, a participant who judges a sentence ‘2’ is judging it to be more acceptable than a sentence to which they have assigned a ‘1’. Likewise, a participant who judges a sentence a ‘4’ is judging it to be more acceptable than a ‘3’. But there is no guarantee that a ‘4’ is as much of an improvement on ‘3’ as a ‘2’ is on ‘1’: in other words, these numbers do not define an interval scale. In some participants and experiments, the judgment ‘2’ might correspond to a much wider range of underlying acceptability than ‘1’, say, but less than ‘3’. It is possible for a spurious statistical interaction to arise if, for example, lower ratings define a much narrower range of acceptability than higher ratings or vice versa (Dillon and Wagers 2021). This is a familiar problem with statistical interactions, when the measurement scale has an unknown relationship to the underlying cognitive constructs (Loftus 1978; Rotello et al. 2015). Two solutions have been proposed to this problem: one, magnitude estimation, has been largely discarded because its assumptions are not met by acceptability judgments (Sprouse 2011). Another, z-score transformation by participants, is widely employed to dampen scale bias effects; but it can still give rise to spurious interactions. However, most researchers are at least implicitly aware of this problem and take care to guard against “ceiling” and “floor” effects, which can give rise to some of the pernicious scale compression problems mentioned above. Dillon and Wagers (2021) advocate for using tools from signal detection theory, such as the receiver-operating characteristic function, which directly takes into account how the scale is used, but in the research we report below, we use cumulative ordinal regression modeling to directly estimate the “width” of each ratings category and thus guard against spurious interactions. In figures and data tables, we report average ratings as if they were numbers, for convenience and comparability to previous research, but the underlying data analysis is ordinal.

3. Experiments

As illustrated above, a simple 2 × 2 Length by Structure experiment can be used to estimate island strength for a single domain. However, by holding the domain constant and manipulating an additional factor—the environment in which the domain in question is embedded—we can gain insight into the influence of the surrounding environment on the acceptability of extraction and, hopefully, the permeability of relative clause islands in particular environments.

In this research, we expand the Length by Structure design in this way to estimate the permeability of relative clauses in various environments in English. Following the descriptions of the conditions that facilitate extraction from relative clauses in the Mainland Scandinavian languages and Hebrew, we aimed to examine experimentally whether the facts are parallel at any effect size for English.

3.1. Experiment 1: Syntactic/Semantic Environment

This experiment employs the Length by Structure design to measure the permeability of RCs embedded within two of the three environments discussed in Section 1: the nominal pivot of a canonical existential (exemplified by (5) above) and the nominal complement of a copula (exemplified by (6) above). To allow adequate comparison to non-permeable RCs, we included a third environment: the direct object of a transitive verb. This resulted in a 2 × 2 × 3 experimental design (Length by Structure by Environment).

3.1.1. Participants

Forty-eight participants were recruited on Mechanical Turk, and each participant was paid 5.00 USD for their participation. Participants’ data were excluded if their average rating for grammatical fillers was below their average rating for ungrammatical fillers. This resulted in two participants’ data being excluded, resulting in a total of forty-six participants’ data being included in the analysis.

3.1.2. Materials and Methods

The fully crossed design resulted in 12 conditions per item, a sample of which is provided in Table 1. Thirty-six items were constructed in total. The level of the Environment factor referring to the nominal pivot of an existential environment level is labeled Existential; the level referring to the nominal complement of a copula is labeled Predicate (as in predicate nominal), and the level referring to the object of a transitive verb is labeled Transitive object. In contrast to the experiments that follow it, Experiment 1 tested extraction from a relative clause for wh-question formation.

Table 1.

Experiment 1 sample item.

All experiment conditions in every item contained the word only. In the Island conditions for the Transitive object and Predicate groups, we used DP-internal only, following impressionistic judgments that only improves the acceptability of existing sub-extraction examples, such as (8b). In the other conditions, only was included to maintain lexical matching to the extent possible. The reason that only seems to improve the chances of successful sub-extraction in the-DPs may be because it removes part of the presuppositional component that commonly accompanies the use of the definite determiner (see McNally 2008, p. 165).

Seventy-two filler sentences were included in this study, all of which were presented to a participant, regardless of which Latin square list the participant received. Both the mean and the median length for the filler sentences was twelve words. The fillers were a mix of grammatical and ungrammatical declaratives and interrogatives. Including both filler and experimental conditions, each participant viewed and rated 108 sentences, half of which were interrogatives and half of which were declaratives. Because all experiment items contained the word only, half of the filler sentences were constructed with the word only, which resulted in each participant seeing seventy-two only sentences and thirty-six sentences without only.

One of the challenges faced by researchers extending the factorial definition of islands to relative clauses is illustrated in all of the non-island conditions in Table 1. In order to accurately gauge the permeability of a relative clause in a particular environment, a non-island equivalent must be identified for each environment that plausibly contains all of the same contributors to degraded acceptability that the island condition does, except for those that are specific to island extraction.5 For the existential conditions, our plausible non-island replaced the relative clause within the nominal pivot with the present participial phrase commonly found in existentials (Deal 2009). For the predicate nominal conditions, we replaced an embedded copular clause with an embedded non-copular clause. For the Transitive object conditions, we replaced RC-containing DP complements with clausal complements. To maintain lexical similarity within those conditions, the embedded verbs for the Transitive object conditions were all capable of taking either a DP complement or a clausal complement (see, hear, notice, remember, recognize, find, discover, and mention).6

3.1.3. Analysis

The reported DD scores were calculated on ratings that were z-scored by participant with filler ratings data.

We fit a mixed-effects ordinal regression model with a cumulative link to the ratings data. A maximal random-effects structure was specified. Rating was set as the dependent variable, and Length, Structure, and Environment type were set as fixed effects.

We assigned the Length and Structure factors sum contrast coding and the Environment factor Helmert contrast coding. The effect of this on the model estimation process was that the Predicate and Existential levels were compared directly to each other, and their mean was compared directly to the Transitive object level. We believed this to be sensible since we had reason to believe that the Predicate and Existential conditions would pattern more closely with each other than with the Transitive object conditions. We refer to the comparison between the Predicate and Existential levels as the Pred_Exist comparison, and the comparison between the combination of those two levels and the Transitive object level as the PredExist_Object comparison.

3.1.4. Predictions

We expected to find main effects at least of Length and Structure. Since the Island, Long conditions involve extraction from a relative clause, we expect to see an interaction between Length and Structure that collapses across the three Environments. If there is indeed a significant reduction in island effects for the Predicate and Existential environments (as compared to the Transitive object environment), we expect a significant three-way interaction between Length, Structure, and the comparison between the Transitive object conditions and the means of the Predicate and Existential conditions. If the island effects observed in the Predicate conditions are substantially different than those observed for the Existential conditions, we expect to see an interaction between Length, Structure, and the Predicate–Existential comparison.

3.1.5. Results

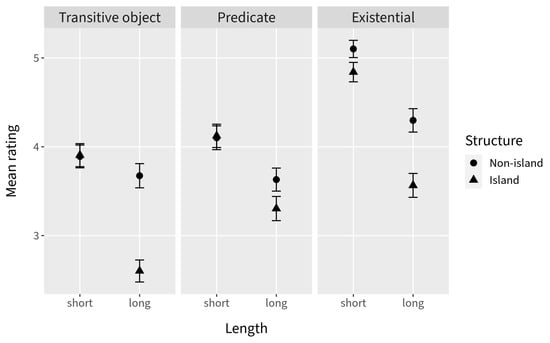

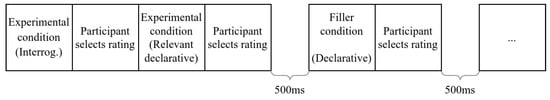

The mean raw ratings for Experiment 1 are reported in Table 2 and visualized in Figure 1. The collection of Transitive object conditions received the lowest ratings overall, followed by the Predicate conditions. We see the expected drop in acceptability ratings in the conditions involving extraction from a relative clause (Long, Island), but this drop is fairly unremarkable in the Predicate conditions, suggesting a reduced island effect at least in that environment.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics for Experiment 1 results. Mean is calculated on raw (non-z-scored) ratings.

Figure 1.

Mean ratings faceted by Environment, arranged in columns by Length. Error bars represent the standard error. Mean is calculated on raw (non-z-scored) ratings.

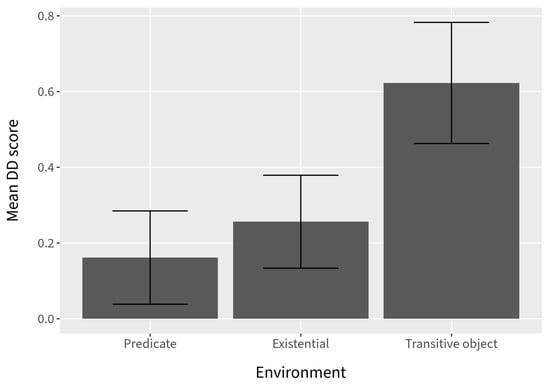

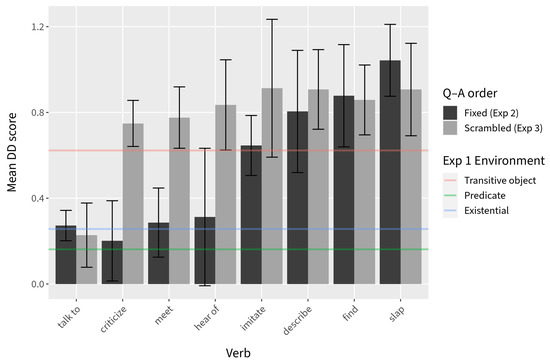

The DD scores calculated from the z-scored ratings in Table 2 are presented in Figure 2. The DD score for the Predicate environment is the lowest, which is expected considering the observation made above about the ratings for this condition. The DD score for the Existential environment follows, and the DD score for the Transitive object environment is substantially higher than that for either the Predicate or Existential environments. Readers who wish to scrutinize the DD scores by item that are averaged to produce the DD scores in Figure 2 may refer to Appendix D.

Figure 2.

DD scores by Environment (calculated from z-scored ratings). Error bars represent the standard error over DD scores calculated per item. DD scores, left to right: 0.16, 0.26, 0.62. See z-scored ratings by item in Appendix D.1.

In the ordinal regression model (see Appendix E.1 for model output), all environments were significantly different from each other, as revealed by significant main effects of Pred_Exist (p < 0.001) and PredExist_Object (p < 0.001). Length and Structure also had significant independent effects on ratings (both ps < 0.001). There was a significant island effect overall, as revealed by a significant interaction between Length and Structure (p < 0.001).

As hinted at by the relatively low DD scores for the Predicate and Existential environments (compared to the Transitive object environment), there was a significant three-way interaction between Length, Structure, and PredExist_Object (p < 0.001). On the other hand, the interaction between Length, Structure, and Pred_Exist was not significant (p = 0.124).

3.1.6. Discussion

The results of Experiment 1 suggest that RCs in both the predicate nominal and existential pivot environments are significantly more permeable than RCs in a transitive object environment. The lack of a significant three-way interaction between Length, Structure, and Pred_Exist suggests that the difference between the DD scores for the Predicate and Existential environments is negligible and that these environments effectively pattern together when it comes to the acceptability of extraction from RCs.

It remains an open question why the DD scores for the two environments that facilitate extraction are above zero. This suggests that there is not a complete amelioration of island effects. However, this finding is reminiscent of Kush et al. (2019), which found residual island effects for most of the island types they examined in Norwegian (despite informal reports of non-islandhood).

3.2. Experiment 2: Existential-like Transitive Verbs (with Supporting Context)

Although Experiment 1 demonstrates a clear reduction in island effect size for predicate nominal and existential environments, the results do not tell us why those environments facilitate extraction from RCs in English. The effect could in principle be unique to precisely those two environments, but it could also be due to properties those two environments have in common—properties that other environments might also have.

One property that these two environments have in common is that the DP that contains the RC is non-presupposed. In existential environments, the existence of the referent of the DP pivot is not presupposed because its existence is being asserted. Similarly, in predicate nominal environments, the existence of the referent of the DP predicate is not presupposed; it is asserted in positive predications and denied in negative predications. To say whether it could be the non-presuppositional nature of the DP in these environments that supports extraction or whether something else about these environments is responsible for the effect, one might consider whether transitive verbs that can be used in an existential way to introduce a referent—and therefore do not presuppose their direct object—can be counted among the environments that facilitate extraction in English. Rubovitz-Mann (2000) terms such verbs, when co-occurring with a first-person subject, “Evidential Existential” because, as noted in the introduction, the speaker can use them to assert (or deny) the existence of the entity denoted by the direct object by indicating the source of evidence for the existential claim (e.g., in the right context, I talked to someone who can fix your leak ≈ There is (indeed) someone who can fix your leak; I know because I talked to them). Of course, existential-like transitive verbs are also known to facilitate extraction in the Mainland Scandinavian languages (Engdahl 1997; Erteschik-Shir 1973) and Hebrew (Rubovitz-Mann 2000; Sichel 2018), so examining extraction from RCs in these environments in English is required for a complete picture of the parallels between extraction in English and extraction in the Mainland Scandinavian languages, Hebrew, and the Romance languages.

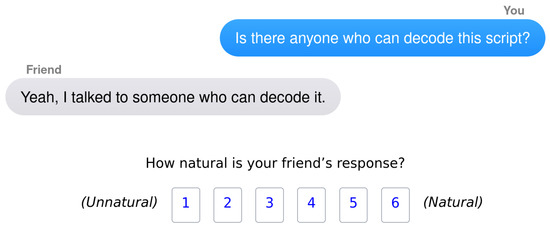

Because evidential existentiality is basically a pragmatic notion rather than a syntactic notion, a means to measure the compatibility of a transitive verb with an existential use is required—both to determine which transitive verbs should be counted as evidential existentials in an experiment and to determine which should be counted as being incompatible with such a use. In a norming rating study, we gauged the compatibility of fourteen transitive verbs with an evidential existential use by presenting a context-setting existential question alongside an affirmative answer that contains one of the following fourteen transitive verbs with a first-person subject: slap, imitate, describe, criticize, advise, praise, call, date, run into, meet, find, know, hear of, and talk to. A sample dialogue is provided in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Screenshot of in-experiment dialogue from evidential existentiality norming study.

To ascertain where the felicitousness of the transitive verbs lay with respect to a canonical existential response, we included there is as a baseline condition. Our findings are presented in (12), which orders the transitive verbs (and canonical existential) from most to least felicitous under an attempted evidential existential use. The details of the norming study are presented in Appendix B.

- (12)

- talk to > hear of > there is > know > find > meet > run into > date > call > praise > advise > criticize > describe > imitate > slap

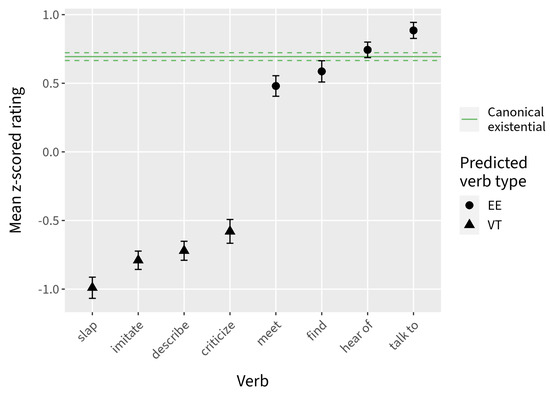

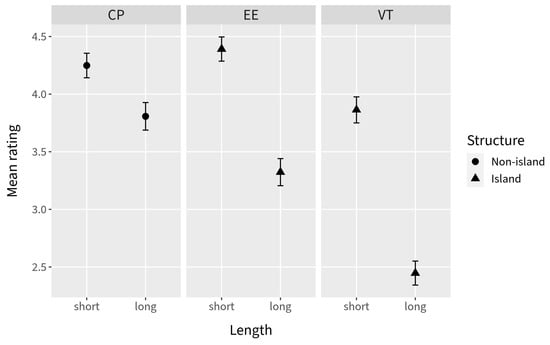

The verbs selected for the current experiment were the four transitive verbs rated as most felicitous under an evidential existential use and the four verbs rated as least felicitous. These eight verbs and their z-scored ratings from the norming study are visualized in Figure 4. For comparison, the felicitousness rating of the canonical existential is included in the figure as a horizontal green line.

Figure 4.

Mean z-scored ratings representing the felicitousness of making an existential claim with eight different matrix verbs (x-axis) in response to an existential question. Error bars (and dashed horizontal lines) represent the standard errors.

The present study utilizes the factorial definition of islands to measure the size of the island effect caused by extraction from RCs under evidential existential transitive verbs (henceforth, EE) and “ordinary” transitive verbs (henceforth, VT). Because the evidential existential use requires a supporting context—one in which the existence of some individual or class of individuals is under discussion and in which the speaker’s evidential basis for making an existential claim is necessary or relevant (Rubovitz-Mann 2012, chap. 3)—our goal in developing the materials and methods for Experiment 2 was to supply a context without suggesting to our participants that each declarative sentence was to be judged according to how well it fit in the supplied context. That is, we wanted to ensure that the task was still nominally about judging the acceptability of individual sentences but allow the suggested context to “prime” an evidential existential use of the declarative sentence.

The method we devised was to present a context-setting interrogative as if it were an independent trial to be judged by the participant in the same way as all other trials in the experiment. Normally, trials are randomized or pseudo-randomized in an experiment, so to ensure that the interrogative was capable of suggesting a context for the relevant declarative sentence, we hard-coded the ordering of question trials and their relevant answer trials to ensure that the question had the best chance of implicitly reminding the participant of a possible evidential existential interpretation of the following declarative. Additional details are provided in Section 3.2.2.

3.2.1. Participants

Forty-four participants were recruited for Experiment 2 on Prolific Pro 2022. Participants received 7.13 USD (12.04 USD/h on average) in compensation for their participation. The following exclusion criteria were pre-defined:7

- (13)

- Participants will be excluded if at least one of the two following conditions are met:

- At least 25% of the participant’s response times were shorter than one second.

- The participant’s mean ratings for unacceptable and acceptable fillers are either inverted or are too close. Too close is defined on normalized (z-scored) ratings as a difference between the average of unacceptable fillers and the average of acceptable fillers that is more than two standard deviations below the mean difference (across participants).

Two participants met the second criterion, and their results were excluded from the analysis, resulting in a total of forty-two participants’ data being used. Of the participants whose data were included, their ages ranged from 19 to 71 years. The mean age was 36.1; the median age was 31. Participants were pre-screened so that they could not participate if they had previously participated in experiments run on Prolific for this research. They were required to be born in and currently reside in the United States and were required to have English as their first language or as one of two first languages. They were required to not have any language-related disorders and to have received at least a high school diploma.

3.2.2. Materials and Methods

The materials for Experiment 2 were constructed according to a reduced factorial design. As in Experiment 1, three factors were crossed: Length (Short; Long), Structure (Non-island; Island), and now, Verb type (EE; VT). In this and the following experiment, the sentences presented for judgment were not wh-questions (in contrast to those for Experiment 1) but declaratives involving relativization. This move was made so that we could utilize a context-setting interrogative, which would provide the context for the critical conditions. A full factorial design would have resulted in eight conditions per item (2 × 2 × 2), but because the non-island conditions for the two verb types would have been identical, one duplicate set of non-island conditions was left out, resulting in six conditions per item. The non-island conditions were given the label CP for the verb type factor because the non-island conditions were all constructed with a CP-complement-taking verb (one of believe, claim, imagine, suggest, suspect, or think).

Each condition consisted of a pair of sentences: a context-setting question and a relevant answer to that question. The questions were existential in nature, each one asking whether any individual who meets the conditions described in a restrictive relative clause exists. The answers to these questions were all declarative statements that could be taken as indirect existential assertions in response to the question. A sample item for Experiment 2 is provided in Table 3.

Table 3.

Experiment 2 sample item.

Thirty-six items were constructed in total, twelve of which were reserved for an initial practice period that we henceforth refer to as a “burn-in” practice period.8 Trials from the burn-in practice period (“burn-in trials”) were not analyzed. The purpose of including burn-in trials is to ensure that the data included in the analysis were acquired after participants had acclimatized to the ratings scale and the variety of sentences they would be judging. As shown in Figure 4, the four verbs used for the VT conditions were slap, imitate, describe, and criticize; and the four verbs used for the EE conditions were meet, find, hear of, and talk to. These were distributed equally across the items (each verb was used in six different items).9 Ratings data were collected for one item whose EE conditions were found to have a typo.10 Because the typo was discovered after data collection, the ratings for this item were excluded from all analysis. This resulted in considering one less data point per participant than intended.

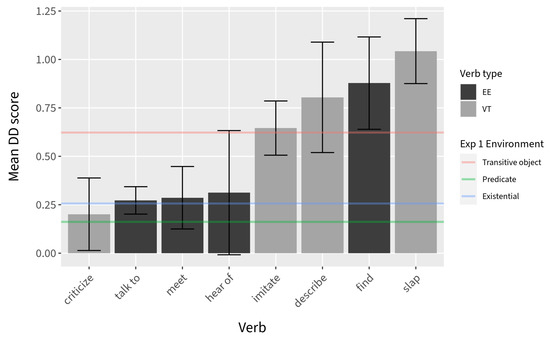

To prevent participants from judging the acceptability of the sentences qua answers to the questions, the task instructions asked participants to focus on the acceptability of each individual sentence. However, Q–A pairs were treated as a unit for Experiment 2, by which we mean that when a question was presented for a participant to rate, the relevant answer was always next in line to rate. As a result, any effect of context on the acceptability of extraction from a relative clause is expected to be implicit, rather than the simultaneous presentation of question and answer as a dialogue. In addition to this structure imposed on the order of question trials and relevant answer trials, we coded a 500 ms separator between all trials except adjacent question trials and a relevant answer trial. These had no separator, so upon selecting an acceptability rating for the question, the participant would immediately be presented with the relevant answer (see the visualization of the placement of the 500 ms separator in Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Trial order structure in Experiment 2, highlighting placement of 500 ms separators.

Three sets of fillers were constructed with the goal of ensuring a relatively even balance of grammatical and ungrammatical interrogatives and declaratives and a selection of paired (i.e., adjacent) interrogatives and declaratives, isolated interrogatives, and isolated declaratives. A total of 126 filler items were constructed in total, forty-two of which were reserved for the “burn-in” practice period. Approximately 26% of trials overall were grammatical interrogatives; 18% were ungrammatical interrogatives; 29% were grammatical declaratives; and 27% were ungrammatical declaratives. Out of all trials, approximately 34% were interrogatives adjacent to a relevant declarative, 34% were declaratives following a relevant interrogative, 10% were isolated interrogatives, and 22% were isolated declaratives.

As noted above, burn-in items were created for both experimental and filler items. A period lasting for about the first third of the experiment (about 100 trials, twelve of which were from the experimental items) was dedicated to the burn-in items. In the interest of transparency, descriptive statistics from the experimental burn-in trials are provided in Appendix C.

For instructions on how to access a working demonstration copy of Experiment 2, please see Appendix A.

3.2.3. Analysis

To derive the DD scores presented below, we calculated z-scores by participant using the ratings data for the main experimental and filler conditions following the burn-in period.

We fit a mixed-effects ordinal regression model with a cumulative link to the ratings data. A maximal random-effects structure was specified. Rating was set as the dependent variable, and Length and Verb type were set as fixed effects. Again, Structure was not included in the analysis because the reduced structure of the experiment design, combined with the contrast coding given to the Verb type factor, resulted in Structure not providing any independent information.

We assigned the Length factor sum contrast coding and the Verb type factor treatment contrast coding. This effectively treats the CP-complement level as the baseline condition for the other two verb types. For this factor, this results in the EE and VT conditions not being compared directly to each other, but to the other condition’s difference with the CP level.

3.2.4. Predictions

We anticipated main effects of Length (Short > Long), Structure (Non-island > Island), and Verb type (EE > VT). Main effects for Length and Structure are expected because of the greater processing demands involved in processing longer-distance (vs. shorter-distance) dependencies and in processing embedded clauses requiring filler-gap resolution (vs. those that do not). We expect a main effect of Verb type because the more specific meaning of the VT conditions was less relevant to the context set by the adjacent question. Due to the treatment contrast coding applied to the Verb type factor, we expect the latter main effect to show up as a significant main effect of VT as compared to the CP level and an insignificant main effect of EE as compared to CP.

At the very least, we expect to see a significant interaction between Length and Structure for the VT conditions; this would be the standard island effect. If island effects are completely ameliorated for the EE conditions, we would not expect to see a significant interaction between Length and Structure for the EE conditions. However, considering that there was still a significant interaction between Length and Structure for the Existential conditions in Experiment 1, we may observe a reduction in island effects for the EE conditions that does not completely remove the interaction between Length and Structure.

3.2.5. Results

The descriptive statistics are summarized in Table 4, and the mean ratings in Table 4 are visualized in Figure 6. The reader will note that there is a generally reduced acceptability associated with the VT conditions, suggesting that the more specific event descriptions of the verbs used in those conditions caused degradation, that these conditions were less acceptable as answers to existential questions, or a mixture of both of these possibilities. Unsurprisingly, the EE, Long and VT, Long conditions were the most degraded, falling below long-distance extraction from a complement clause (CP).

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics for Experiment 2 results. Mean is calculated on raw (non-z-scored) ratings.

Figure 6.

Mean ratings for Experiment 2. Error bars represent the standard error. Mean is calculated on raw (non-z-scored) ratings.

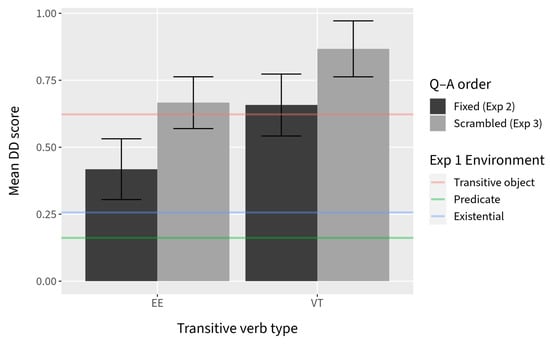

The DD score plot in Figure 7 shows the range of DD scores calculated for each verb used in Experiment 2. The DD scores for the EE verbs were lower on average than those for the VT verbs, but one verb categorized as VT (criticize) fell among the lowest DD scores, and one verb categorized as EE (find) fell among the highest DD scores. Despite these apparent outlier DD scores, we take these DD scores to be a confirmation of our predictions from a descriptive statistical standpoint: RCs within non-presupposed direct objects are more permeable than those within the direct objects of more typical transitive verbs.

Figure 7.

DD scores (calculated from z-scored ratings) by verb for Experiment 2 with DD scores for Experiment 1 environments overlaid as horizontal lines. Error bars represent the standard error over DD scores calculated by item. Summary statistics are based on five to six DD scores calculated for each verb. See z-scored ratings by item in Appendix D.2.

In the ordinal regression model (see Appendix E.3 for model output), we observed a main effect of Length (p = 0.022). The comparison of the CP conditions to the EE conditions was just outside of the 0.05 significance threshold (p = 0.064), indicating that we cannot reliably conclude that the EE conditions were judged any differently from the CP conditions overall. On the other hand, the comparison of the CP conditions to the VT conditions was significant (p < 0.001), which is consistent with the impressions given by Figure 6.

Both length interactions were significant (ps < 0.001), although the interaction between length and the CP–EE comparison received a smaller coefficient estimate, indicating a smaller effect size for that interaction.

3.2.6. Discussion

The significance of the interactions in the ordinal regression model indicates that even with supporting context, there is still a significant island effect for both verb types. However, both the DD scores and the coefficient estimates for the models indicate a smaller effect size for EE verbs, which suggests that the island effect for that verb type is reduced.

3.3. Experiment 3: Existential-like Transitive Verbs (without Supporting Context)

In order to gauge the impact of the indirectly suggested context on the island effects observed in Experiment 2, we constructed and deployed Experiment 3, which was identical to Experiment 2 except that the context-setting questions were paired with an item whose answers were unrelated and irrelevant. All other aspects of the experiment remained unchanged from Experiment 2.

3.3.1. Participants

Forty-four participants were recruited for Experiment 3 on Prolific. Participants received 7.13 USD (11.26 USD/h on average) in compensation for their participation. The same exclusion criteria were used for Experiment 3 as were used for Experiment 2.

Again, two participants met the second criterion, and their results were excluded from analysis, resulting in a total of forty-two participants’ data being included in the analysis. Of the participants whose data were included, their ages ranged from 18 to 64 years. The mean age was 34.7; the median age was 33. Participants were pre-screened so that they could not participate if they had previously participated in experiments run on Prolific for this research. They were required to be born in and currently reside in the United States and were required to have English as their first language or as one of two first languages. They were required to not have any language-related disorders and to have received at least a high school diploma.

3.3.2. Materials and Methods

The materials and methods used for Experiment 3 were identical to those used for Experiment 2, but the question and answer components of each item were scrambled so that participants would never see a relevant declarative statement that could felicitously be interpreted as an answer to the question in the immediately preceding trial. The task instructions remained the same; participants were instructed to rate the acceptability of each sentence, whether declarative or interrogative, on an individual basis. The 500 ms separator was implemented in exactly the same situations, but due to the scrambling of questions and relevant answers, the lack of a separator was no longer a subliminal cue that an adjacent question and answer might be construed together. A sample item is provided in Table 5; note, in particular, that the associated question is irrelevant to the set of possible answers. Due to the shared materials between Experiment 2 and Experiment 3, data for the same item that had a typo in Experiment 2 were also collected but excluded from all analysis.

Table 5.

Experiment 3 sample item.

For instructions on how to access a working demonstration copy of Experiment 3, please see Appendix A.

3.3.3. Analysis

The DD scores presented below were calculated in the same way as for Experiment 2.

We fit a mixed-effects ordinal regression model with a cumulative link to the ratings data from Experiment 3. A maximal random-effects structure was specified. Rating was set as the dependent variable, and Length and Verb type were set as fixed effects. Structure was not included in the analysis because the reduced structure of the experiment design, combined with the contrast coding given to the Verb type factor, resulted in Structure not providing any independent information.

We assigned the Length factor sum contrast coding and the Verb type factor treatment contrast coding. This effectively treats the CP level as the baseline condition for the other two verb types. For this factor, this results in the EE and VT conditions not being compared directly to each other, but to the other condition’s difference with the CP level.

In order to obtain a more direct comparison of the results from the two experiments, we also pooled the ratings data, introduced an Experiment factor (which we also refer to as Q–A order, with the levels Fixed, for Experiment 2, and Scrambled, for Experiment 3), and estimated a second mixed-effects ordinal regression model for the pooled data. In the regression formula for this second model, Experiment was coded as an additional factor (see Appendix E.5).

3.3.4. Predictions

We anticipated main effects of Length as well as main effects for both Verb type comparisons. Main effects for Length are expected because of the greater processing demands involved in processing longer-distance (vs. shorter-distance) dependencies and in processing embedded clauses requiring filler-gap resolution (vs. those that do not). In contrast to our expectations for Experiment 2, we do not expect different main effects of Verb type because the effect of scrambling questions and relevant answers is that no declaratives that follow questions will be felicitous answers. Because one EE sentence and one VT sentence per item involved extraction from a relative clause and the CP conditions did not, we expect main effects of verb type for both the EE–CP comparison and the VT–CP comparison.

We expect to see a significant interaction between Length and Structure for both the VT and EE conditions, reflecting an island effect for relative clauses under both Verb types.

3.3.5. Results

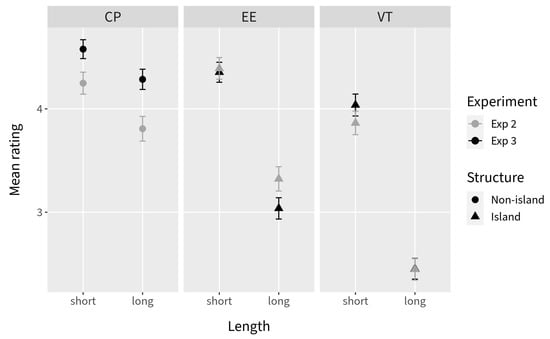

The mean ratings data are summarized in Table 6 and visualized in Figure 8. Overall, the results appear quite parallel to the results from Experiment 2, but there was a slight increase in the ratings for both Non-island conditions, a decrease in the mean rating for the EE, Long condition, and an increase in the VT, Short condition.

Table 6.

Descriptive statistics for Experiment 3 results. Mean is calculated on raw (non-z-scored) ratings.

Figure 8.

Mean ratings for Experiment 3 (Experiment 2 ratings shown in light gray). Error bars represent the standard error. Mean is calculated on raw (non-z-scored) ratings.

The DD scores calculated by verb for the Experiment 3 data are presented in Figure 9 alongside the DD scores for Experiment 2. Notable differences from the DD scores for Experiment 2 include a disproportionate increase in DD scores for the EE verbs except for talk to, whose DD score remained basically unchanged. The scores for the VT verbs remained fairly constant, but the DD score for criticize, which was unexpectedly low in Experiment 2, increased.

Figure 9.

DD scores (calculated from z-scored ratings) by verb and Q–A order (Experiment) with Experiment 1 DD scores overlaid as horizontal lines. Error bars represent the standard error over DD scores calculated by item. Summary statistics are based on five to six DD scores calculated per verb per experiment. See z-scored ratings by item in Appendix D.

In the ordinal regression model we fit to the ratings data, there was a main effect of Length (p = 0.0079), and both comparisons (EE; VT) to the CP conditions were significant (ps < 0.001). Additionally, the interactions between Length and the CP comparisons were significant (ps < 0.001).

In the analysis of the pooled ratings data from the two experiments, we found a significant main effect of Experiment (p = 0.008). See the coefficient estimates for the combined analysis in Appendix E.5. There was a significant interaction between Experiment and the EE–CP comparison (p < 0.001), and the parallel VT–CP comparison interaction was not significant (p = 0.07). The interaction between Experiment, Length, and the EE–CP comparison was not significant (p = 0.109), nor was the interaction between Experiment, Length, and the VT–CP comparison (p = 0.236).

3.3.6. Discussion

The EE–CP comparison was significant in Experiment 3, in contrast to Experiment 2, which suggests that context has an outsize effect on the acceptability of evidential existential responses compared to typical transitive verbs. In the ordinal regression for the pooled data (in which Experiment was included as a factor), the significant interaction between Experiment and EE–CP confirms that this difference across experiments was significant. We take this to be a validation of the notion of an evidential existential use for a transitive verb, as well as the notion that certain verbs more naturally fall into this class than others.

As predicted, we cannot reliably conclude that either the EE or VT conditions completely lacked an island effect, as indicated by the significant interactions between Length and both EE/VT–CP comparisons. The combined ordinal regression model also indicated that the strength of the island effect is not significantly different for either Verb type level across the two experiments, which means we cannot conclude with certainty that context generally increased the permeability of RCs in evidential existential contexts. This is reflected by the closeness of the error bars in the DD score plot presented in Figure 10, which collapses DD scores by Verb type. Although the slight non-overlap of the error bars in the EE half of the plot, along with the slight overlap of the error bars in the VT half of the plot, gives the impression of a disproportionate effect of context on RC permeability for the EE conditions (as predicted), the data do not allow us to conclude with confidence that this is the case.

Figure 10.

Average DD scores (calculated from z-scored ratings) by transitive verb type and Q–A order (Experiment) with Experiment 1 DD scores overlaid as horizontal lines. Error bars represent the standard error over DD scores. See z-scored ratings by item in Appendix D.

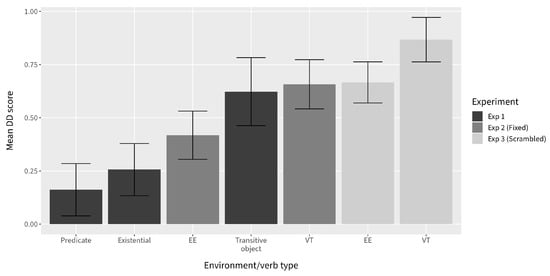

4. General Discussion

The inferential statistics for Experiments 2 and 3 indicate a persistent interaction between Length and Environment, regardless of Verb type. Taking these results seriously, we cannot conclude that there was a complete absence of island effects in either experiment. This conclusion is confirmed by the ordinal regression model estimated for the combination of the data from the two experiments: the lack of a significant interaction between Length, Environment, and Experiment (for either verb type) indicates that we cannot confidently conclude that there was a significant difference in island effect across Experiment 2 and Experiment 3 within each Verb type.

However, examination of the DD scores suggests that the combined effects of Verb type and context are not inconsequential. Although we observed a general increase in the DD scores for both verb types in Experiment 3, the DD scores for the EE verb type pull apart slightly more across the two experiments when compared to the VT verb type (Figure 10). Further, when the mean DD scores visualized in Figure 10 are broken down according to verb (Figure 9), there are notable trends within each verb type. The only verb in the EE group that maintained consistently low DD scores across the two experiments was talk to. This is unlikely to be due to chance; the results from the evidential existentiality norming study indicate that out of fourteen transitive verbs tested, talk to is the most natural transitive verb with which to make an “evidential existential” claim (for additional discussion, see Vincent 2021). Two of the other four EE verbs used in Experiments 2 and 3, meet and hear of, have a noticeably higher DD score in Experiment 3, when context did not favor an existential use. Similarly, three out of four verbs that were categorized under VT (imitate, describe, and slap) maintained consistently high DD scores across the two experiments. This also seems unlikely to be due to chance, as these three verbs were found to be the least natural transitive verbs to use to make an existential claim in a supporting context.

What this suggests to us is that there is a gradient effect on relative clause permeability that is affected by the likelihood of the transitive verb being used existentially. Certain verbs such as talk to are so natural in non-canonical existential assertions that a reading in which their complement is non-presupposed is easily accommodated. Verbs such as imitate, describe, and slap, on the other hand, are so unnatural in existential assertions that a non-presupposed reading of their complement is difficult to accommodate—even when context provides the right conditions for an existential assertion. It is also possible that there is variation across speakers regarding the possibility for a non-canonical existential reading for particular verbs, contributing to the overall less clear picture.

In conjunction with the results from Experiment 1, in which canonical existential and predicate nominal environments result in a substantial decrease in island effects, the picture that emerges is that the same factors appear to modulate RC permeability in English as in the Mainland Scandinavian languages: extraction is facilitated when the RC is within a predicate nominal, an existential pivot, or a direct object of a verb with which it is natural to make an existential assertion (refer to the combined DD score plot in Figure 11). This finding is noteworthy from an empirical standpoint because it contrasts with the general consensus that English islands (apart from whether-complements) invariably give rise to severe degradation under extraction.

Figure 11.

DD scores (calculated from z-scored ratings) across the three experiments reported in this work. Error bars represent the standard error. See z-scored ratings by item in Appendix D.

From a theoretical standpoint, our findings provide some clues as to which analyses of extraction from RC may turn out to be fruitful and which may turn out to be unfruitful. What initially appeared to be a phenomenon specific to the Mainland Scandinavian languages may be a more general pattern than initially thought. If the phenomenon’s first discovery in these languages is what initially led to suggestions that island constraints be parameterized to handle cross-linguistic variation, then finding that this phenomenon is observable even in English should take us at least one step away from parameterization. It appears likely that the picture is both more cross-linguistically uniform and also more nuanced, language-internally, than a parameterization approach could satisfactorily handle.

Besides the language-particular effects found in English, another conclusion which emerges from our experiments is that the environments which facilitate extraction seem to be cross-linguistically uniform: extraction is permitted (or more acceptable) from a non-presupposed RC (Erteschik-Shir 1973, 1982; Engdahl 1997; Rubovitz-Mann 2000; Sichel 2018; Vincent 2021). Regardless of the ultimate “island” status of some of these environments, the existence of such a consistent cross-linguistic landscape suggests that there is something to understand about these environments and why they facilitate extraction to the extent that they do. The significance of these particular environments is further highlighted by the fact that sub-extraction from simple, non-relative DPs in English follows the same pattern: possible when DP is a non-presupposed indefinite. Here, too, the English pattern is similar to what is known about other languages (Davies and Dubinsky 2003; Diesing 1992; Fiengo and Higginbotham 1981; Mahajan 1992, among others). This suggests that presuppositional DPs are strong islands, and that English RCs, when non-presuppositional, are weak islands, as in other languages in which sub-extraction is attested. Another empirical benefit of our study is that it provides a clear blueprint for future studies in other languages: measurement of sub-extraction facilitation effects depends on knowing where to look for them. Rather than comparing, for example, extraction from RC in subject position vs. extraction from RC in object position, or extraction from indefinite RCs vs. definite RCs, it seems to us that, to the extent that it is at all possible in a language, sub-extraction from an RC is most likely to be found in the sort of non-presuppositional contexts we have focused on.11 Further investigation of these environments in other languages is needed for a clearer understanding of the cross-linguistic landscape of RC island-hood and its relationship to general DP island-hood.

On the theoretical side, a more nuanced conception of the environments which facilitate sub-extraction is key for the analysis of these cases and for our understanding of the nature of island violations more generally. First, the claim in Sichel (2018) that the external environments which facilitate RC sub-extraction are no different from those which support sub-extraction from simple DPs is further supported by the English pattern. If this is so, and to the extent that sub-extraction from simple DPs can ultimately be analyzed in terms of the syntactic position (derived, non-derived) of presupposed and non-presupposed DPs (Bianchi and Chesi 2014; Diesing 1992), there is no a priori reason to suspect that sub-extraction from RCs is any different: an RC from which extraction is acceptable is in a non-derived position, consistent with contemporary theories of DP-islandhood, which allow sub-extraction from a simple DP when that DP is in a non-derived position (Rizzi 2004; Stepanov 2001; Takahashi 1994; Uriagereka 1999; Gallego and Uriagereka 2006, 2007; Chomsky 2008; among others).

Second, the empirical cut which emerges from English, along with other languages which permit RC sub-extraction to some degree, can be used to further test predictions raised by other theories of acceptable extraction from islands. In a recent paper on extraction from subject islands, Abeillé et al. (2020) focus on the nature of the extracted constituent and argue for an information-structure based constraint on sub-extraction from subjects, according to which extraction is subject to a focus-background conflict constraint (FBC), a gradient constraint disallowing a focused element to be part of a backgrounded constituent. They compared A-bar extraction for wh-questioning with A-bar extraction for relativization, across subjects and objects. They found that extraction from a subject is degraded compared to extraction from an object when extraction is part of question formation—but not when it is part of relativization. The effect is attributed to a clash between the focus potential of the wh-phrase and the givenness of subjects, generally. While we basically agree with the characterization of the extraction domain which hinders sub-extraction in terms of information structure, and with the specific characterization in terms of pre-suppositionality (or givenness, in the terms of Abeillé et al. 2020), we believe that our more nuanced approach to the distribution of these environments is helpful for further testing of their predictions. While Abeillé et al. (2020) have characterized the overall difference between subjects and objects in terms of givenness, we follow contemporary findings in syntax and semantics which acknowledge that presuppositionality has an effect on sub-extraction both within the domain of subjects, as well as within the domain of objects: presupposed subjects, as well as presupposed objects, block sub-extraction, whereas non-presupposed objects, as well as non-presupposed subjects, are more porous for sub-extraction. We also think that it is premature to attribute this sensitivity to a clash between the information-structural properties of the extraction domain and the information-structural properties of the extracted constituent. If the source of the problem were indeed such a clash, the expectation is that the characterization of the extraction domain should vary across extraction types—and should reverse when the extracted constituent is information-structurally characterized as given, or presupposed. In particular, the types of A-bar movement which apply to given, presuppositional constituents, such as scrambling and topicalization, should actually be more acceptable when the extraction domain is a presupposed (or given) DP than when it is non-presupposed. Our own study used both wh-movement in question formation (Experiment 1) and relativization (Experiments 2 and 3) and made no attempt to manipulate them systematically. Kush et al. (2019) found a lower penalty for topicalization out of RCs than for wh-questioning out of RCs but made no attempt to systematically manipulate environments which ‘unlock’ islands. Sichel (2018) found that topicalization from an RC follows the same presuppositional pattern as in the present study, an indication that the extraction domain does not vary with the information-structure characterization of the extracted constituent. That study, however, is not experimental and did not include the careful quantitative controls that experimental studies, such as the former studies, do. We hope that future work will test these comparative predictions by combining careful quantitative controls and nuanced manipulation of the blocking and facilitating environments.

Although less central to the main focus of this paper, we hope to impress two main methodological points upon our readers. First, we believe that our experiments can be viewed as a trial of the Length by Structure experiment design and an example of how it can be extended to measure not only the permeability of individual island domains but the influence of additional factors (such as environment and context) on the permeability of island domains. Second, we believe that our effort to suggest a context (in Experiment 2) without changing the nature of the acceptability judgment task was successful, considering the distinctions we observed in the results for experiments that were identical except for the relevance of Q–A pairs. Future research in this and other areas may find this technique useful when context is relevant or is part of an experiment manipulation but when it is undesirable to directly ask participants to consider an item with respect to a context.

5. Conclusions

Our results indicate that English should be counted among the languages that allow extraction from RCs in at least some environments. The results from Experiment 1 suggest a negligible island effect for RCs in predicate nominal environments and a substantially reduced island effect for those in canonical existential environments. The interactions between the Environment comparisons and Length were significant in both Experiments 2 and 3, indicating that the data collapsed across verbs still bear the signature of a significant island effect. However, the DD scores calculated by verb reveal a somewhat more complex story: the scores for three out of four of the verbs we categorized as EE verbs (talk to, meet, and hear of) are on a par with the DD score for canonical existentials in Experiment 1 when participants are “primed” by an adjacent context-setting question.

In addition to the above findings, an important takeaway is that cross-linguistically, the factors that enhance a relative clause’s permeability appear to be stable, even if the size of their effects on acceptability ratings vary somewhat. It is a clear pattern that environments and contexts that support existential, non-presupposed interpretations of the DP containing the RC ‘unlock’ the RC to some extent, whether the environment is a direct assertion (or denial) of existence, a nominal predication, or an indirect assertion (or denial) of existence using an evidential existential verb in a supporting context.

Lastly, we highlighted the methodological innovations that we believe may be useful for further investigation into this and other topics. These include expansion of the Length by Structure design to compare extraction environments as closely as possible as well as the use of trial adjacency to suggest interpretation and evaluation of a condition in the context of another condition without disturbing the overall task.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.W.V., I.S. and M.W.W.; Data curation, J.W.V.; Formal analysis, J.W.V., I.S. and M.W.W.; Methodology, J.W.V., I.S. and M.W.W.; Visualization, J.W.V.; Writing—original draft, J.W.V., I.S. and M.W.W.; Writing—review & editing, J.W.V., I.S. and M.W.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study is exempt from IRB review as determined by the Institutional Review Board of the University of California, Santa Cruz (protocol code HS0801386, granted 09/04/2009).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are openly available at the Open Science Framework: https://osf.io/tz7af (accessed on 5 May 2022).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank two anonymous reviewers of Languages for their detailed and thoughtful comments and critiques on an earlier version of this paper, which we believe helped us sharpen and focus our framing and discussion.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Experiment Demonstration Links

The following links go to full working demonstrations of Experiments 2 and 3. To get past the onboarding form, fill in the mandatory fields with bogus information.

- Experiment 2: https://farm.pcibex.net/r/YfwLvt/ (accessed on 11 January 2022)

- Experiment 3: https://farm.pcibex.net/r/JQXOij/ (accessed on 11 January 2022)

Appendix B. Evidential Existentiality Norming Study

Appendix B.1. Participants

A total of 121 undergraduate students at UC Santa Cruz participated in the norming experiment for course credit—0 of these participants’ data was not included in the analysis, 27 of which self-reported as non-native English speakers, and three of which met at least one of the exclusion criteria defined in (13). The data from ninety-one participants were included in the analysis. Participant age ranged from 18 to 33. The mean age was 20.

Appendix B.2. Materials and Methods

Thirty-six items were created, twelve of which were again reserved for the burn-in practice period. A sample item is provided in Table A1. The experiment included a single factor, Response, of which there were three levels: there existential, Evidential existential, and Transitive verb. These response types describe responses to polar questions inquiring about the existence of a human individual matching a particular description contained in a relative clause. The question was invariant within each item.

Table A1.

Evidential existentiality norming study sample item.

Table A1.

Evidential existentiality norming study sample item.

| Sentence | Response Type | |

|---|---|---|

| Question: Is there anyone who can decode this script? | ||

| a | Yeah, I’m sure there’s someone who can decode it. | There existential |

| b | Yeah, I talked to someone who can decode it. | Evidential existential |

| c | Yeah, I criticized someone who can decode it. | Transitive verb |

On a given trial, participants saw a polar question presented above one kind of response. The question–answer pair was formatted as a brief text-message thread (Figure 4). As in the other experiments, participants were instructed to choose a rating from a Likert-type scale. Here, they were instructed to rate how natural the response was to the answer.

Appendix B.3. Analysis

We fit a mixed-effects ordinal regression model with a cumulative link to the ratings data. A maximal random-effects structure was specified. Rating was set as the dependent variable, and Response was set as a fixed effect.