Abstract

The acquisition of negation in Child Italian has not yet been comprehensively addressed in the literature. This paper aims to provide a fine-grained picture of the acquisition process in this Romance language by considering production data and exploring three specific aspects of negation development: (a) the emergence and subsequent development of negators and negative constructions, (b) the acquisition of negative functions and their varying proportion of use and (c) the emergence of negative concord constructions. Using the CHILDES database, the longitudinal data of four monolingual Italian children for an observation period from 1;07 to 3;04 years of age were extracted, and the negative utterances attested in their speech production were analyzed for both the single- and the multiword utterance period. Results show a consistent and progressive form–function development of negation, mainly in line with previous cross-linguistic literature but with some language-related features. Minor differences across children are also attested, which are arguably related to their language development, as measured by their mean length of utterance (MLU) in the age intervals considered.

1. Introduction

Although negation in natural languages is a complex and heterogeneous phenomenon, the first instances of linguistic negation appear in children’s speech quite early, by 18 and 24 months of life. Nevertheless, its acquisition is a gradual and challenging process, as it takes time for children to fully grasp the semantic meanings of the different negative words to be able to use them correctly across different sentential contexts. Moreover, in order to understand how to negate a sentence, children must also learn how negation can have scope over different parts of the sentences, leaving the others unaffected. The picture becomes even more complicated for children when multiple negative structures come into play, in which the negative meaning is conveyed by the combination of two (or more) negative elements. The interpretation of these complex syntactic constructions is indeed not always straightforward since a different arrangement of the same negative elements may yield different semantic interpretations of the same sentence. For instance, in Standard Italian, when a neg-word is preceded by the negative marker (e.g., Non ha telefonato nessuno), the sentence conveys a negative meaning (in our example: nobody called). On the contrary, when the same neg-word precedes the negative marker (e.g., Nessuno non ha telefonato), the sentence yields an affirmation (everybody called).

Though much research has been conducted on the acquisition of negation, especially with a focus on English, studies on Italian are lacking. The aim of the present study is to fill this gap in the acquisitional literature by providing a preliminary overview of negation development in Child Italian. Our investigation extends from the earliest occurrences of negation during the single-word utterance period to the emergence of the more complex negative concord structures, by examining how the different functions of negation and the negative constructions arise in the children’s spontaneous speech. This introductory section offers a brief review of the literature investigating the development of the different meanings expressed by negation in both the single- and the multiword utterance period (Section 1.1), and how negators are employed within specific negative constructions during different acquisitional stages (Section 1.2). In addition, we provide relevant background information on the various syntactic strategies that a non-strict negative concord language such as Italian has at its disposal to convey the sentence’s negative meaning (Section 1.3). After this introduction, we describe the methodology and the analyses that we have conducted on the children’s speech samples (Section 2). Eventually, we present the results of the study (Section 3) and discuss their implications also in light of previous findings in the cross-linguistic literature (Section 4 and Section 5).

1.1. Emergence of the Semantic Meanings of Negation

The acquisition of negation has been extensively investigated in a number of Child languages (e.g., Jordens (1987) for Dutch; Choi (1988) for English, French and Korean; Hummer et al. (1993) for German; Weissenborn et al. (1989) for German, French and Hebrew; McNeill and McNeill (1973) for Japanese; Felix (1987) for German and English; Klima and Bellugi (1966) for English; Drozd (1995) for English; see Dimroth (2010) for a comprehensive overview). These studies highlighted interesting commonalities across child languages with regard to the form–function development of negation.

As soon as they begin to speak at about one year of age, children start using negative words apparently without significant problems. However, these earliest negation forms do not cover the entire range of negative meanings used in adult languages, as the lexical differentiation of negative words and their inclusion into fully developed utterances require time and increasingly high processing/cognitive resources. At the beginning of its development in language use, negation has essentially affective and volitional functions: children use it to express their emotions and intentions about a situation in the immediate extralinguistic context. Instead, children seem to acquire truth-functional negation only several months later. Stern (1964) argued that English-speaking children use the earliest form no to reject a previous statement (i.e., No, I do not want that) rather than to express a logical and truth-functional judgement (i.e., No, this is not the case). This intuition was later supported by Pea (1980), who maintained that children predominantly use negation to indicate prohibition during their first year of life. This semantic meaning would be directly inferred from the parents’ behaviour: in fact, when children are doing anything wrong or dangerous, parents typically address them saying no and by shaking their head.

During the single-word utterance period (and thus before being able to produce complete sentences), children use basic forms of syntactic negation to cover different negative functions, which gradually develop and appear later in their multiword speech production. At this earliest stage of language acquisition, children do not make formal distinctions between the negative expressions used, making it difficult to identify the semantic categories of negation (Cameron-Faulkner et al. 2007). Pea (1980) proposed a categorization of the different semantic meanings of negation based on the similarities between the child’s linguistic behaviour and the different situational contexts in which negation is used. Based on longitudinal data from six English-speaking children, he identified three main broad semantic categories that are widely used to classify the possible negative meanings emerging during the single-word utterance period: rejection, non-existence and truth-functional/denial. Data collected cross-linguistically (e.g., Drozd 1995; Guidetti 2005; Hummer et al. 1993; Pea 1980) showed that the first semantic category of negation that children express is rejection. Later on, they begin to use negation to make comments on the disappearance and non-existence of familiar objects and persons in the surrounding environment. Finally, at around two years of age, they begin to negate the truth of a statement within a specific situational context. This common acquisitional order has been interpreted as evidence that the emergence of new semantic meanings is intrinsically related to children’s general cognitive development. In fact, these three types of semantic negation involve an increasing development of abstract forms and cognitive representations, and, consequently, their use demands different levels of processing capacities. Rejection does not involve abstract representations as it is used by children to express an attitude towards an event, object or person that is directly present in the situational context. Instead, in the case of non-existence/absence, the relevant object is no longer present in the context and must be denoted abstractly. The truth-functional meaning of negation requires an even higher level of cognitive representation: children must in fact simultaneously deal with two different situations, one corresponding to the actual state of the world, and one representing its false counterpart (Hummer et al. 1993).

Interestingly, some researchers have put forward the hypothesis that the earliest occurrences of denial in children’s speech production are not proper instances of truth-functional negation (which would be too demanding in terms of processing costs for children that young), but rather an expression of metalinguistic negation (Drozd 1995; Hummer et al. 1993). According to Drozd (1995), children initially use denial to express semantic functions already acquired, that is, rejecting another person’s use of language that they consider improper and expressing unfulfilled expectations towards this linguistic behaviour. Instead, Gopnik and Meltzoff (1985) considered the expression of inability to carry out a given action and the failure of plans as a bridging function between the earliest context-related meanings of negation and truth-functional denial.

Given the difficulty of discerning the semantic categories of negation during the one-word stage of language acquisition, researchers have mainly focused their attention on the development of negative meanings within children’s multiword sentences. In her influential study on three American English-speaking children, Bloom (1970) identified three main categories of negative meanings, and argued that they arise in child language in the following developmental order: multiword forms emerge first in non-existence (e.g., There’s no cookie), then in rejection (e.g., I don’t want the cookie), and finally in denial (e.g., That’s not a cookie). While a clear similarity between the two taxonomies proposed by the researchers can be observed, different acquisitional orders have been found for the single- and the multiword utterance periods: in the former, negation initially appears as rejection, while non-existence is the first semantic meaning to be expressed in the latter. This developmental pattern has been attested in several target languages (e.g., Bloom (1970) for English; McNeill and McNeill (1973) for Japanese; Choi (1988) for English, French and Korean). In particular, Choi1 (1988) argued that the different orders of acquisition found in the single- and multiword utterance period are related to the fact that children can easily resort to one-word expressions to reject an object or an action, as the referent is imminent and salient in the situational context. On the contrary, in non-existence, children have to make comments about referents that are no longer evident in the discourse context: as a consequence, they have to quickly develop negative forms in multiword speeches to adequately convey this semantic meaning. Nonetheless, researchers agree that the semantic categories of rejection and non-existence are cross-linguistically acquired before denial in both acquisitional stages, corroborating the assumption that the emergence of the different negative meanings is directly related to the growth and development of children’s cognitive representational abilities.

As regards Italian, acquisitional studies on negation are rather sparse. The principal work on the acquisition of negation in Child Italian is the pragmatic study by Volterra and Antinucci (1979), which has been largely criticized because of the excessive emphasis put on the role of the addressee’s presupposed set of beliefs as the trigger for the different negative meanings (Horn 1989; Pea 1980). While some aspects of negation have been assessed in comprehension (e.g., the interpretation of negative sentences with disjunction in Pagliarini et al. (2018, 2022)), to the best of our knowledge no acquisition research on Child Italian has yet comprehensively addressed the emergence of the functions of negation in production.

1.2. Emergence of Negators and Negative Constructions

Numerous studies have focused on the acquisition of formal expressions of negation in children’s early multiword production, distinguishing between anaphoric negation, which relates to the previous utterance, and sentential negation, in which the negative meaning applies to the sentence itself.

| (1) | ADULT: | This is red |

| CHILD: | No, orange (anaphoric) | |

| CHILD: | This is not red (sentential) |

Almost all languages examined have distinct negators (i.e., lexical items) for anaphoric and sentential negation: moreover, the former can occur either in isolation or in sentence initial position, while the latter usually occupies a sentence internal position (Bellugi 1967; Cameron-Faulkner et al. 2007; Choi 1988; Déprez and Pierce 1993; Klima and Bellugi 1966; Weissenborn et al. 1989; Wode 1977). Cross-linguistic studies have shown that anaphoric forms of negation are the first to appear in a child’s multiword utterances. This anaphoric priority is attributed to its higher frequency in the adult input, which allows children to master this form of negation very quickly. However, it remains unclear whether children use these anaphoric forms, typical of the adult language, only to express anaphoric negation or also as instances of sentential negation2. In this respect, the data collected among different languages are quite heterogeneous. In French, children seem to never use the anaphoric form non to express sentential negation, which is normally expressed by pas: this is arguably due to the fact that these negators have fixed positions within the sentence, which might help children discriminate between them (Weissenborn et al. 1989). Although German also has fixed syntactic positions for anaphoric (i.e., nein) and sentential (i.e., nicht) negation, there is evidence for an acquisitional phase in which German-speaking children consistently use the anaphoric negator to express sentential negation (e.g., Ich nein schlafen, lit. ‘I no sleep’): this behaviour has been attributed not to a simple overgeneralization of the first negator acquired, but rather to a preference displayed by children for the phonetically less complex form (Déprez and Pierce 1993).

As for English, Klima and Bellugi (1966) reported evidence for an acquisition stage in which children have not yet realized how to use the different expressions of negation within specific syntactic contexts: children would initially use interchangeably the anaphoric no and the sentential not in contexts in which only the latter is adequate, by mastering the two forms only after the acquisition of n’t negative words (i.e., can’t, don’t). Wode (1977) attributed this initial confusion in the use of the two negative forms to their phonological resemblance. This hypothesis has been discarded by more recent experimental evidence, showing that the anaphoric no and the sentential not do not occur randomly in sentence internal position (Cameron-Faulkner et al. 2007). If on the one hand English-speaking children initially use the anaphoric form to express sentential negation (e.g., no move, no go), on the other hand, this tendency decreases at around two and a half years of age. At the same time, the correct use of the sentential form in the appropriate contexts starts to increase, and by the age of three, not is finally the dominant form used by children to express sentential negation. The researchers suggested that the temporary overlapping between the two different forms of negation would be the result of a conservative learning strategy: during the acquisition process, children would simply tend to express new linguistic functions using lexical items already acquired such as the more familiar negator no to also express sentential negation in multiword productions (see also Choi 1988).

As a matter of fact, children not only have to acquire the specific lexical items for the different forms of negation, but they also have to learn how to combine these negators within the sentences. Based on a longitudinal data collection, Felix (1987) proposed the following developmental sequence for the position of sentential negation in English and German. During Stage 1, children express negation by means of the negator no placed in sentence external position (no+S, e.g., No daddy hungry). A possible explanation for this phenomenon is that children initially collocate negation outside of its scope domain because they arguably have a holistic representation of the syntactic clause itself (Slobin (1985); Van Valin (1991); but see also Drozd (1995) and Klima and Bellugi (1966)). At a certain point in their development, they begin to conceive the sentence as being composed of different functional parts. This view has been challenged by Bloom (1991), who argued that instances of external negation are rather the consequence of missing subjects, which are often omitted at this stage of language development (see Déprez and Pierce (1993) for an opposite view). During Stage 2, negation moves to a sentence internal position in close proximity to the VP; however, this stage is mainly characterized by the incorrect use of no to express sentential negation (no+VP, e.g., I no sleep). Only later on, at Stage 3, do the different negators begin to be used appropriately by children, who now consistently use the correct marker of sentential negation (not+VP, e.g., I do not sleep). As pointed out above, the transition between the last two acquisitional stages is not clear-cut but is characterized by a temporary overlap in the use of the two syntactic constructions.

To the best of our knowledge, there are no previous acquisition studies examining the use of different negators (the anaphoric no and the sentential form non) and the consequent development of negative constructions in Child Italian. Therefore, it currently remains unclear whether Italian-speaking children follow the same phases in the acquisition of negation attested in other child languages, that is, if they go through an early stage in which the negator no is used to express sentential negation.

1.3. The Expression of Sentential Negation in Standard Italian

Since the present article deals with the acquisition of negation in Standard Italian, in this section we provide the reader with a comprehensive overview of the different syntactic constructions used in this language to express sentential negation. Standard Italian makes use of the preverbal negative marker non to introduce semantic negation (2). The negative meaning can also be conveyed by the presence of a single neg-word placed preverbally, that behaves as a negative quantifier (e.g., nessuno ‘nobody’ in 3).

| (2) | Gianni non ha telefonato |

| Gianni not has called | |

| ‘Gianni didn’t call’ | |

| (3) | Nessuno ha telefonato |

| n-body has called | |

| ‘Nobody called’ |

Italian negative indefinites are the neg-words nessuno ‘nobody/not any’, niente and nulla ‘nothing’. Constructions with these neg-words are commonly attested in the standard language, although nulla retains more vernacular traits, and is a form particularly used in the Tuscan area and in Southern Italy.

The combination of neg-words and the negator non within the same sentence may yield different semantic interpretations. When non comes with a negative quantifier placed in post-verbal position, the sentence expresses one single semantic negation:

| (4) | Gianni *(non) ha telefonato a nessuno |

| Gianni not has called to n-body | |

| ‘Gianni didn’t call anybody’ |

Sentence (4) is an instance of negative concord (Labov 1972): two or more negative elements that are able to individually express negation yield instead a single negative meaning when combined. Negative concord (NC) is a well-attested phenomenon in Romance languages, but is licensed also in some Germanic varieties as well as in Greek and Albanian (Giannakidou 1997, 2000; Zeijlstra 2004). In Standard Italian (a non-strict NC language), an NC reading can only be established between a preverbal negative element (either neg-word or negative marker) and neg-words in post-verbal position. Instead, no negative doubling construction is required when the neg-word is in subject position.

Furthermore, Standard Italian does license a double negation (DN) reading of multiple negative constructions in which, along the lines of propositional logic, the two negative elements cancel each other out, yielding an affirmation. As shown in (5), when the preverbal neg-word is combined with non, the NC reading of the sentence is compromised, and a double negation reading can be accessed, modulo specific prosodic features3.

| (5) | Nessuno non ha telefonato |

| n-body not has called | |

| ‘Nobody didn’t call’ |

However, this construction is very infrequent in everyday communication, as its use is subject to pragmatic restrictions: in fact, (5) is accepted only in specific communicative contexts, such as, for example, to deny a previous negative assertion made by another speaker or a presupposition established in the context. From an acquisitional perspective, cross-linguistic studies have shown that children initially tend to assign an NC reading to all multiple negative structures, including those that adults would instead interpret as double negation. Interestingly, this overgeneralization is a common acquisitional trend independent from the L1 (see Miller (2012); and Thornton et al. (2016) for English; Sano et al. (2009) for Japanese; Van Kampen (2010) for Dutch; Zhou et al. (2014) for Mandarin Chinese), with children mastering double negation in both comprehension and production only at a later time. For what concerns Italian, research on this topic is once again extremely scarce. Nonetheless, the first acquisitional studies (Moscati 2020; Tagliani 2019) collecting data on double negation in this Romance language seem to confirm the cross-linguistic evidence speaking in favor of an initial stage of strong preference for NC readings. Moscati (2020) showed that, compared to adults, 5-year-old children provide more negative concord interpretations of negative fragments used as answers to negative questions (that typically yield double negation in Italian). Moreover, Tagliani (2019) assessed both the comprehension and the production of double negation structures in Italian-speaking children aged between 3;10 and 8;2, and she found that this construction is mastered rather late, at about 7;3 years of age. The data collected in this second study support the assumption that the development of children’s knowledge of double negation is gradual, and that it arguably occurs in parallel with the growth of their computational resources.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Using the CHILDES database (MacWhinney 2000), we searched for longitudinal studies with monolingual Italian children between 18 and 48 months of age so as to extend our investigation from the single- to the multiword utterance period. Inclusion criteria were the presence of negative expressions in the child’s speech sample and an observation period longer than six months to detect possible developmental patterns. Based on this, four children from the Calambrone (Cipriani et al. 1989) and the Antelmi (Antelmi 1997) corpora were included in the analysis (see Table 1). All children were observed in their homes while interacting with the investigator and another adult (usually the mother). Three out of four children were regularly recorded for approximately one year, while one was followed for almost two years.

Table 1.

Age and MLU ranges, and number of recordings for each child participant.

2.2. Speech Sample and Procedure

The corpora were searched for negative constructions using the CLAN program (MacWhinney 2000). All single- and multiword utterances, including negators no and non and negative indefinites nulla, niente, and nessuno, as well as their combinations, were extracted from the children’s speech samples. Imitations of the interactor’s speech (i.e., echolalia), self-repetitions and incomplete utterances were excluded from the analysis.

2.3. Categorization of Functions

In the present study, we focused on various syntactic categories of negation structures (see Section 2.5), and for each negator we identified three functional macro-categories based on the coding taxonomy proposed by Bloom (1970) and Pea (1980). Examples taken from the children’s speech are presented below:

- REJECTION/PROHIBITION—the extralinguistic referent (e.g., an object, action or person) is rejected or opposed by the child

(6) MOTHER: si va a prendere i tuoi disegni?4 ‘Are we going to take your drawings?’ CHILD: no (Martina, 1;11) - ABSENCE—the referent is no longer present in the extralinguistic context

(7) MOTHER: e dov’è quello di Pinocchio? ‘And where is the one of Pinocchio?’ CHILD: no quello di Pinocchio non c’è no that of Pinocchio not there is ‘No, the one of Pinocchio is not there’ (Diana, 2;01) - DENIAL—assertion that an actual or supposed predication does not hold

(8) MOTHER: senti, hai giocato con la Dana, oggi? ‘Listen, did you play with Dana today?’ CHILD: no (Camilla, 2;06)

In following this categorization, we analyzed the use of negation to express the inability to carry out a given action, the non-occurrence of a particular event and lack of knowledge (epistemic negation) as belonging to the macro-category of denial. The function of each instance of negation was decided by considering the sentence in the context.

2.4. Coding Reliability

All authors first individually analyzed and coded for function all negative utterances extracted from children’s data samples. This initial coding resulted in 78% agreement on the functions to be assigned. After further discussion, the agreement increased to 85%: sentences for which no agreement was reached were coded as unclassifiable and excluded from Analysis 2. All occurrences, including those with no clear semantic function, were instead considered in Analyses 1 and 3.

2.5. Analyses

Three descriptive analyses were conducted considering each of the recordings that were available for the four children. To gather a complete picture of their acquisition of negation, we grouped the chats available for each child in the following 4-month intervals: 1;07–1;10, 1;11–2;02, 2;03–2;06, 2;07–2;10, 2;11–3;02, 3;03–3;07. We then compared the children’s development in the following three analyses.

Analysis 1 focused on the frequency of use of different types of negators with the aim of describing the development of negative constructions in Child Italian. All single- and multiword utterances containing negators were isolated from the children’s speech samples. To provide an exhaustive picture of negation development, we identified 4 structures of relevant interest: (i) no constructions, including no as single word negator and no x (e.g., no pappa—lit. ‘no food’); (ii) no+VP constructions (e.g., no voglio—lit. ‘no want’); (iii) non constructions; (iv) negative concord constructions, both correct (e.g., non c’è nessuno—lit. ‘there is not no-one’) and incorrect forms (e.g., c’è nessuno—lit. ‘there is no-one’). The proportional frequency of each structure in the negated utterances was then calculated. We decided to analyze no, no+VP and non constructions separately to investigate whether the last two forms were used interchangeably by children, or rather whether their emergence might reflect different stages of acquisition of the negative structures which at some point overlap (Cameron-Faulkner et al. 2007).

Analysis 2 examined the emergence and subsequent development of the different functions of negation in the children’s speech samples in order to understand how negation is used in Child Italian. In addition, we were interested in examining whether the development of negators differed within each function, and if so, to what extent. To this end, all single- and multiword negated utterances in the children’s speech samples were coded according to the three main functions of rejection/prohibition, absence and denial, following the classification proposed by Pea (1980) and Bloom (1970). For each semantic function described in Section 2.3, we calculated the frequency of use of the negators singled out in Analysis 1 during the aforementioned four-month intervals.

Analysis 3 focused on the emergence and characteristic properties of negative concord constructions in Child Italian. The aims of this last analysis were to investigate at what age Italian children begin to use these more complex negative constructions, what types of errors they make as part of the learning process and when such constructions are eventually mastered. The children’s speech samples were searched for three syntactic constructions including the Italian negative indefinites niente, nulla ‘nothing’ and nessuno ‘nobody/not any’ that children could use in the attempt to express a negative concord meaning: (i) correct structures with the neg-word preceded by the negator non; (ii) incorrect structures with the neg-word preceded by the negator no; (iii) incorrect structures with the neg-word in isolation. The proportional frequency of each of these structures on the total of negative concord constructions was then calculated. Each negative indefinite (and corresponding negative concord structures) was analyzed separately.

3. Results

3.1. Analysis 1: Overall Development of Negators and Negative Constructions

To gather a picture of the overall development of negative constructions in Child Italian, we analyzed all the transcriptions available for the four children that we took into consideration. More specifically, we conducted different CLAN queries searching for all the occurrences of no and non and classifying them in instances of (i) no, (i) non, (iii) no+VP, where no instead of non preceded a verb resulting in an ungrammatical structure in Italian, as discussed above, and (iv) of negative concord (NC), where non was used in combination with the neg-words nessuno, niente or nulla.

The average frequency of use of the different types of negators (no, no+VP, non and NC) considered for each child in the relevant four-month intervals is reported in Table 2.

Table 2.

Frequency of each negator in the considered month intervals with the number of total occurrences reported in brackets5.

For the interval 1;07–1;10, anaphoric no is by far the predominant negator for the three children considered, accounting for 90% of the forms uttered and almost exclusively used as a single word negator, as in (9).

| (9) | OBS: | scrivi con la penna Rosa? |

| ‘Are you writing with the pen, Rosa?’ | ||

| CHI: | no! | |

| (Rosa 1;10, MLU 1.40) | ||

The second most common negator is the ungrammatical no+VP (9%), as exemplified below:

| (10) | MOT: | senti un pochino qui che brucia |

| ‘Feel a little here that it is burning’ | ||

| CHI: | o no lo tocco | |

| no it touch | ||

| ‘(I) no touch it’ | ||

| (Martina 1;08, MLU 1.90) | ||

Non characterizes instead only 1% of the negators produced, with just one occurrence produced by Martina.

In the subsequent interval (1;11–2;02), no remains the most common negator, standing at 75%, but we observe an increase in the production of sentential non, which is properly used by all four children and constitutes 18% of the negators at this age. The no+VP form instead diminishes (5%). Although this trend is observed in all four children, some differences can be found. In particular, for Rosa (MLU 1.46), no accounts for 93% of the utterances containing a negator. No+VP and non also appear in the speech sample, respectively accounting for only 5% (4 tokens) and 2% (2 tokens) of the negated utterances. Both these forms are used for the first time in multiword sentences at 2;01. For Martina (MLU 1.95), instead, no constitutes 71% of the negators, followed by non (16%) and no+VP (12%). In Camilla’s transcriptions (MLU 2.64), non is much more frequently produced, reaching the same percentage of no (42%), with 17% of no+VP. For Diana (MLU 3.28) too, non is quite frequent in this interval, representing 30% of the negators, following no that remains the most common one (65%); the occurrence of the ungrammatical form no+VP decreases significantly in her speech from 10% to 1%. The different distribution of no and non in the four children can be related to their MLU: non is not or rarely used when the MLU is still low, as in Rosa (MLU 1.46, non 2%), whereas it increases significantly when the MLU is higher as in Martina (MLU 1.95, non 16%), Camilla (MLU 2.64, non 42%) and Diana (MLU 3.28, non 30%). Interestingly, Diana shows already at this age the first occurrences of NC (4%, 4 tokens) with the neg-words niente and nessuno, which will be discussed more in depth in Analysis 3.

By 2;03–2;06, no utterances remain the predominant negation construction in all children’s speech, although the use of anaphoric no significantly diminishes with respect to the former interval, accounting for 63% of the negated utterances, and followed by non, which instead continues to increase (27%), while no+VP remains marginal (9%). Some instances of NC are observed in Diana, Martina and Rosa (1%), as will be discussed more in detail in Analysis 3. At the individual level, we can observe that no is more frequently used by Rosa (86%, MLU 2.06) and Martina (76%, MLU 2.56), with a lower percentage of non (respectively, 5% and 18%). The difference between the two negators is smaller in Camilla (no: 46%, non: 34%, MLU 3.89) and Diana, for whom non is even more frequent (no: 43%, non: 50%, MLU 4.87). Again, this different trend may be explained by referring to the considerably higher MLU of both Camilla and Diana compared to the other children at the same age. Consistently, Rosa uses non in quite short sentences, with respect to Camilla, as exemplified below.

| (11) | CHI: | non c’è, mamma? |

| not there is, mommy? | ||

| ‘There isn’t, mommy?’ | ||

| MOT: | no, non c’è qui. | |

| no, not there is here | ||

| ‘No, there isn’t here’ | ||

| (Rosa 2;05, MLU 2.14) | ||

| (12) | CHI: | e c’ha i bottoni rossi ma non funziona. |

| and it has red buttons but not works | ||

| ‘And it has red buttons but does not work’ | ||

| (Camilla 2;04, MLU 3.92) | ||

In the next month interval (2;07–2;10), no utterances are still on average prevalent considering all the three children for which transcriptions were available (Camilla, Martina and Rosa), but their frequency in the speech sample continues to decrease, reaching 71% of all negated utterances; non constitutes 19% of the negators, while no+VP remains stable (7%). As in the preceding interval, there is a sharp difference at the individual level: non is much more frequently used by Camilla (60%, MLU 4.19) than by Rosa (15%, MLU 2.41) and Martina (22%, MLU 2.55). Instances of NC constructions remain low (3%) and are attested only in Rosa’s speech.

For the next two intervals, only the recording of Camilla’s and Rosa’s speech are available. By 2;11–3;02, the use of no constructions is stable at 69%, with similar percentages in both children (71% in Rosa, MLU.290 and 64% in Camilla, MLU 3.98). The incidence of non continues to gradually increase in Rosa (19%), but it remains higher in Camilla (31%). No+VP instead gradually decreases for both children (6% Rosa, 4% Camilla). At this stage, the first occurrence of NC is observed in Camilla as well (3% Rosa, 1% Camilla).

Finally, in the last age range (3;03–3;07), the developmental trends observed in the previous speech samples are confirmed. At this stage, no is still the predominant multiword negator in Rosa’s speech (63%, MLU 3.24), while it is much less used by Camilla (30%, MLU 4.61). The frequency of utterances containing the negator non is higher in both children and now accounts for about one third of negated utterances for Rosa (29%) and two thirds for Camilla (63%). In contrast, no+VP constructions constitute 8% of all negated utterances for Rosa, while they are no longer present in Camilla’s speech. No NC constructions are attested in these transcriptions for Rosa, whereas they constitute 7% of the negators for Camilla.

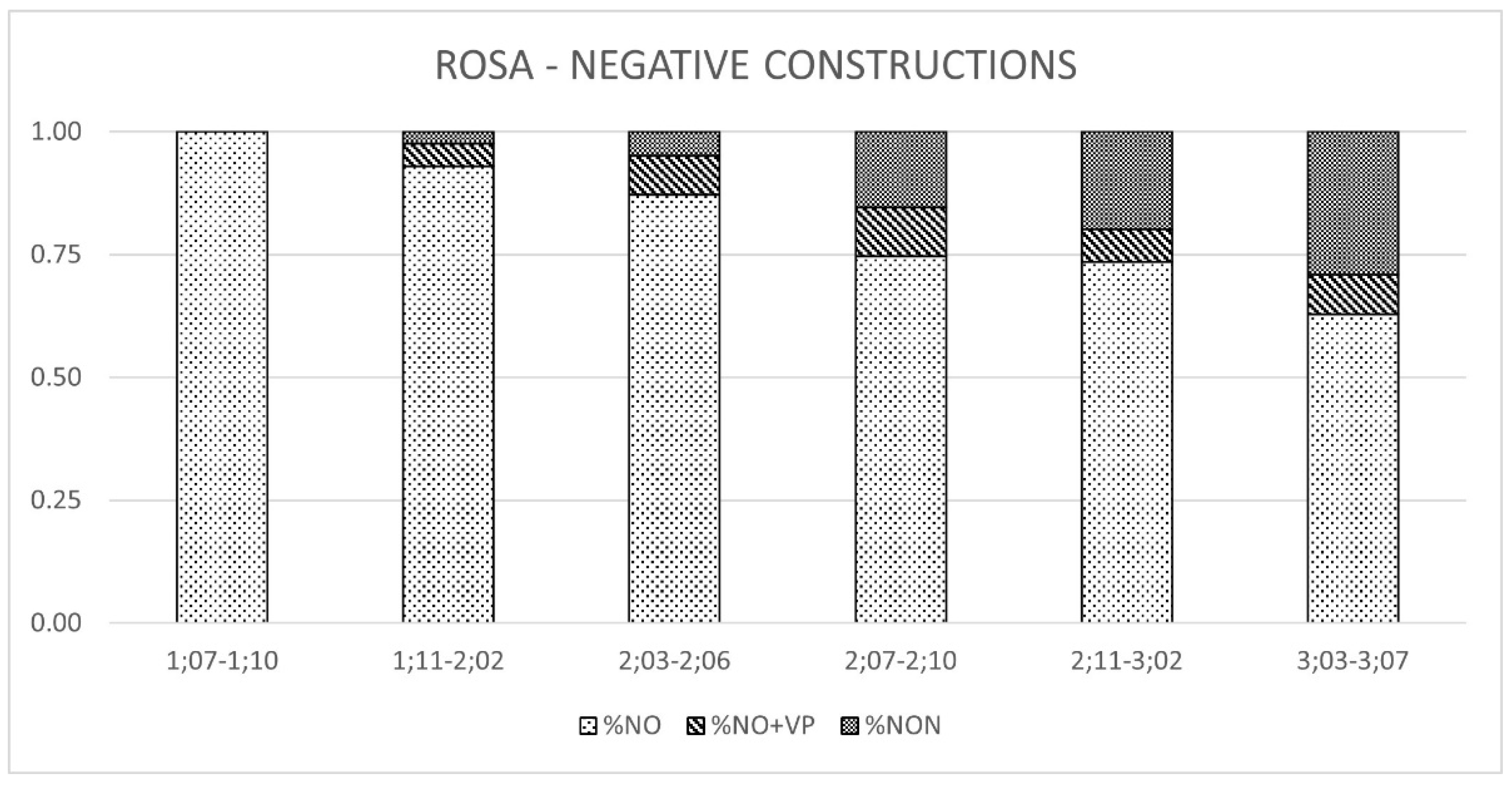

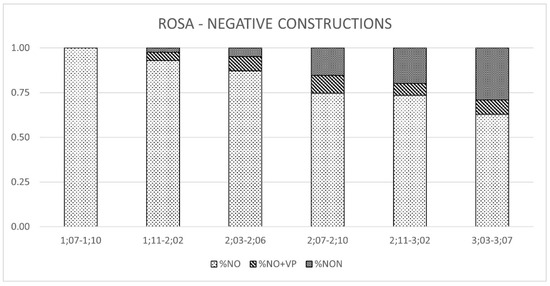

To sum up, the following trend can be observed. For all children, anaphoric negation expressed with no is largely the most common negator in the first stages of negation acquisition. While they grow, in combination with the increase in their MLU, we observe a marked increase in the incidence of sentential negation expressed with non, which becomes equally or even more frequent than no in the children with a longer MLU. Overall, No+VP are limited, and they gradually decrease in the last intervals considered, leaving space for the target form of sentential negation, i.e., non. This is particularly evident in the case of Rosa, as shown in Figure 1, for whom no+VP is more frequent than non in the early intervals (respectively: 5% and 2% at 1;11–2;02, 8% and 5% at 2;03–2;06) and is gradually replaced by non constructions later on (respectively: 10% and 15% at 2;07–2;10, 6% and 19% at 2;11–3;02 and 8% and 29% at 3;03–3;07).

Figure 1.

Proportion of negative constructions in Rosa’s considered month intervals.

Although instances of NC are rarely attested, it is interesting to notice that they are used, although in different moments, by all the children considered, starting from an MLU of 2.06 (Martina). These will be discussed in Analysis 3. In Analysis 2, instead, we discuss the functions used to express negation and how they are distributed in the different negators (no, non and no+VP) across time intervals.

3.2. Analysis 2: Emergence of Functions and Development of Negators within Functions

To understand the emergence and development of negation functions in Child Italian, we analyzed all the transcriptions available for the four children considered. Based on contextual/discourse cues, we coded by semantic function each type of negation structure (no, non and no+VP) uttered by the children. In a limited number of cases (9% for no and 3% of non), it was not possible to properly classify the negators uttered by the children, due to the absence of a sufficiently informative context. We thus decided to exclude them from the analysis. In addition, the last transcription of Camilla was not complete as, in the last part, it only reported the utterances produced by the child, which were thus in some cases uninterpretable and accordingly removed from the analysis.

This analysis aimed to explore the emergence of negation functions and the usage frequency of negators within each function. Accordingly, it is composed of two parts. In the first part, we focused on the emergence and development through time of the functions of negation, i.e., rejection/prohibition, absence and denial (see Section 2.3). We selected the patterns that emerged when considering all children’s data together, but we also discussed differences among the children when relevant. The second part analyzes the proportions of negation structures (no, non and no+VP) used for each semantic function and their development through the six age intervals here considered. Given the low frequency of NC structures, they were excluded from the coding and analyzed separately in Analysis 3.

3.2.1. Emergence of Functions

The average proportions of negation functions considered for each child and cumulatively in the four-month intervals are reported in Table 3.

Table 3.

Proportions of negation functions in the considered month intervals.

In the age interval 1;07–1;10, negation is predominantly used by all children to express rejection/prohibition, accounting for 81% of the negated utterances. These data partly confirm the pattern found in other languages, especially the relative acquisition order of rejection and denial (Bloom 1970; Pea 1980). However, in this interval the three children (Rosa, Martina and Diana) also use negation for the expression of denial (15%) and, to a lesser extent, of absence (4%), although the latter functions are more predominantly used at later stages (when they are mainly expressed through the sentential negator non).

Rejection/Prohibition remains the predominant function of negation also in the successive time interval (1;11–2;02), for which we have the transcriptions of all four children. However, at around two years of age, negation is increasingly employed for denial and, to a lesser extent, for absence too.

This pattern is fairly consistent through all the age ranges considered. Throughout the children’s development, we observe an increase in the use of negation for denial and absence, as evidenced by the proportions in Table 3: while absence is overall the least represented function (probably due to the nature of the corpus), denial progressively increases and becomes the predominant function (53%) at 3;03–3;07, i.e., the last interval considered. At this age, rejection and absence represent only 47% of the instances of negation. This trend is arguably related to a more accurate expression of sentential negation with non and to the mastery of the concept of denial/truth-functional negation. It should be noted, however, that no constructions are still used for denial in the last time interval, showing that the acquisition of this concept applies across all the relevant negation structures (see the second part of Analysis 2).

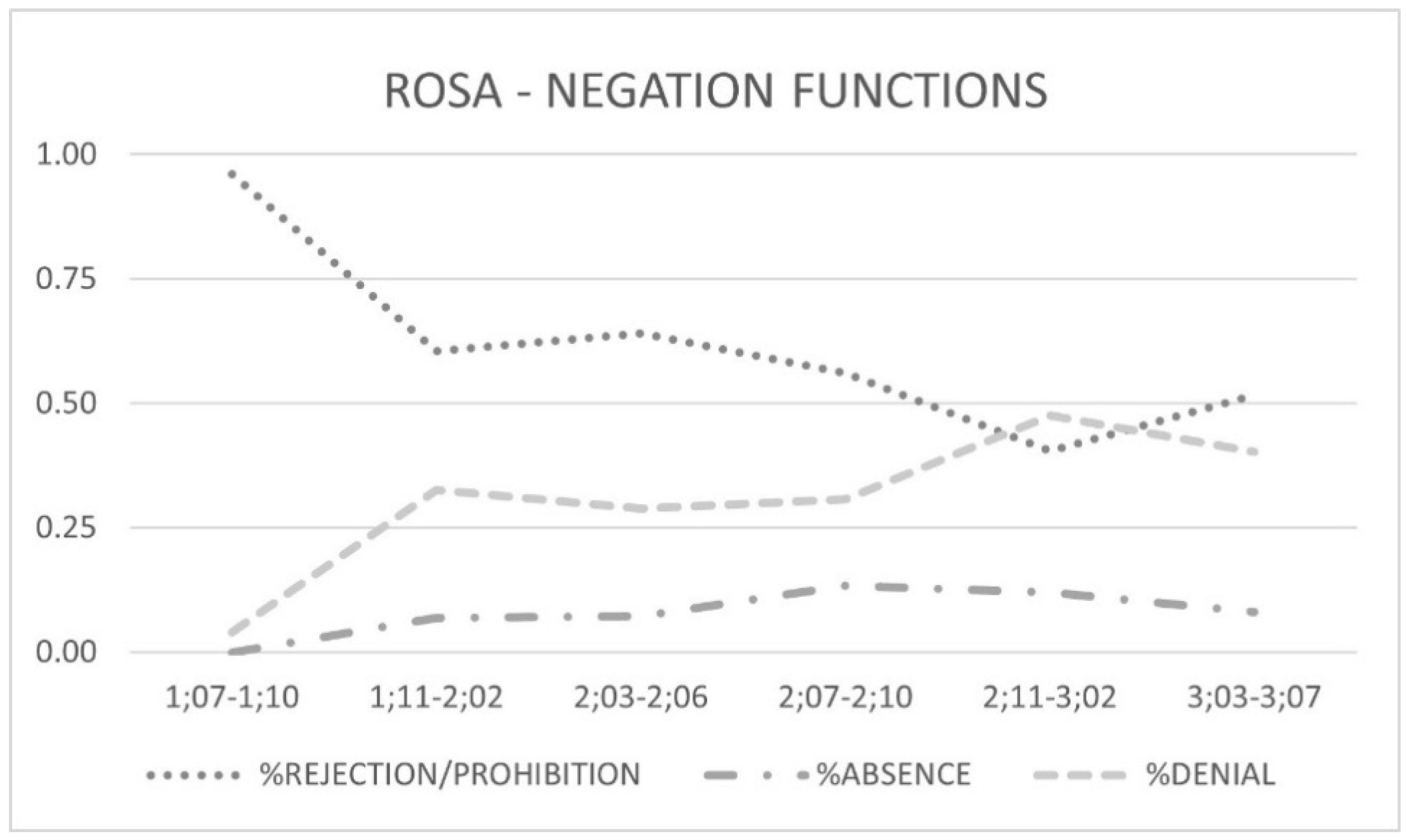

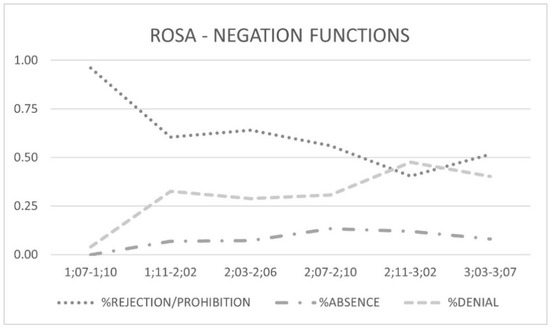

As an example, let us consider one child, Rosa: in the interval 1;07–1;10, she mainly uses negation (specifically through anaphoric no, see Table 2) with the function of rejection/prohibition, but she also deploys it for denial: its first use is already attested at 1;10. Instead, no negated utterances expressing absence are reported during this earliest age period. By 1;11–2;02, negated utterances (including both no and non as negators) begin to be used more consistently to express denial. The first instance of no expressing absence is attested at 1;11. From 2;03 onwards, Rosa consistently uses negation to express all the three functions with no, non and no+VP constructions. Specifically, Rosa’s productions show a progressive increase in denials, while rejections/prohibitions exhibit a decreasing proportional frequency. These trends can be observed in Figure 2 showing the proportions of negation functions used by Rosa across the relevant age intervals.

Figure 2.

Proportion of negation functions in Rosa’s considered month intervals.

Similar patterns are found in the other children, but some differences can be observed that are arguably linked to their language development (as indicated by their different MLU). Indeed, both Camilla and Diana, who have a higher MLU, tend to use negation for the expression of denial and absence earlier than Rosa: this is particularly evident in the interval 2;03–2;06, where Rosa still has a high prevalence of rejections (63%), while the other children have a lesser proportion of rejections (Camilla 39%, Martina 37%, Diana 32%) and deploy negation especially for denial. Across the last intervals, Rosa too increasingly uses negations for denial and absence but, overall, her development seems a bit slower than that of the other children.

3.2.2. Development of Negators within Functions

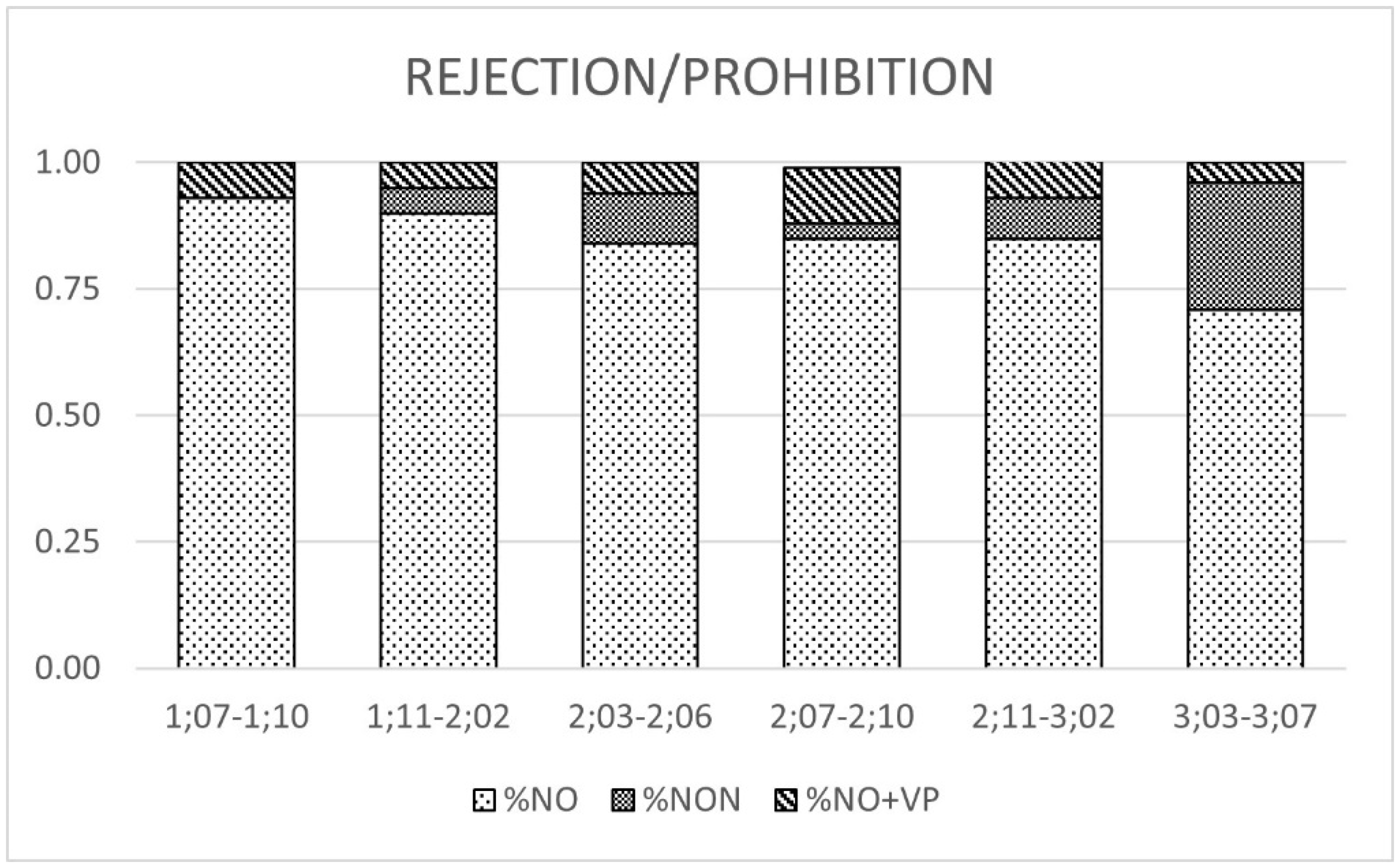

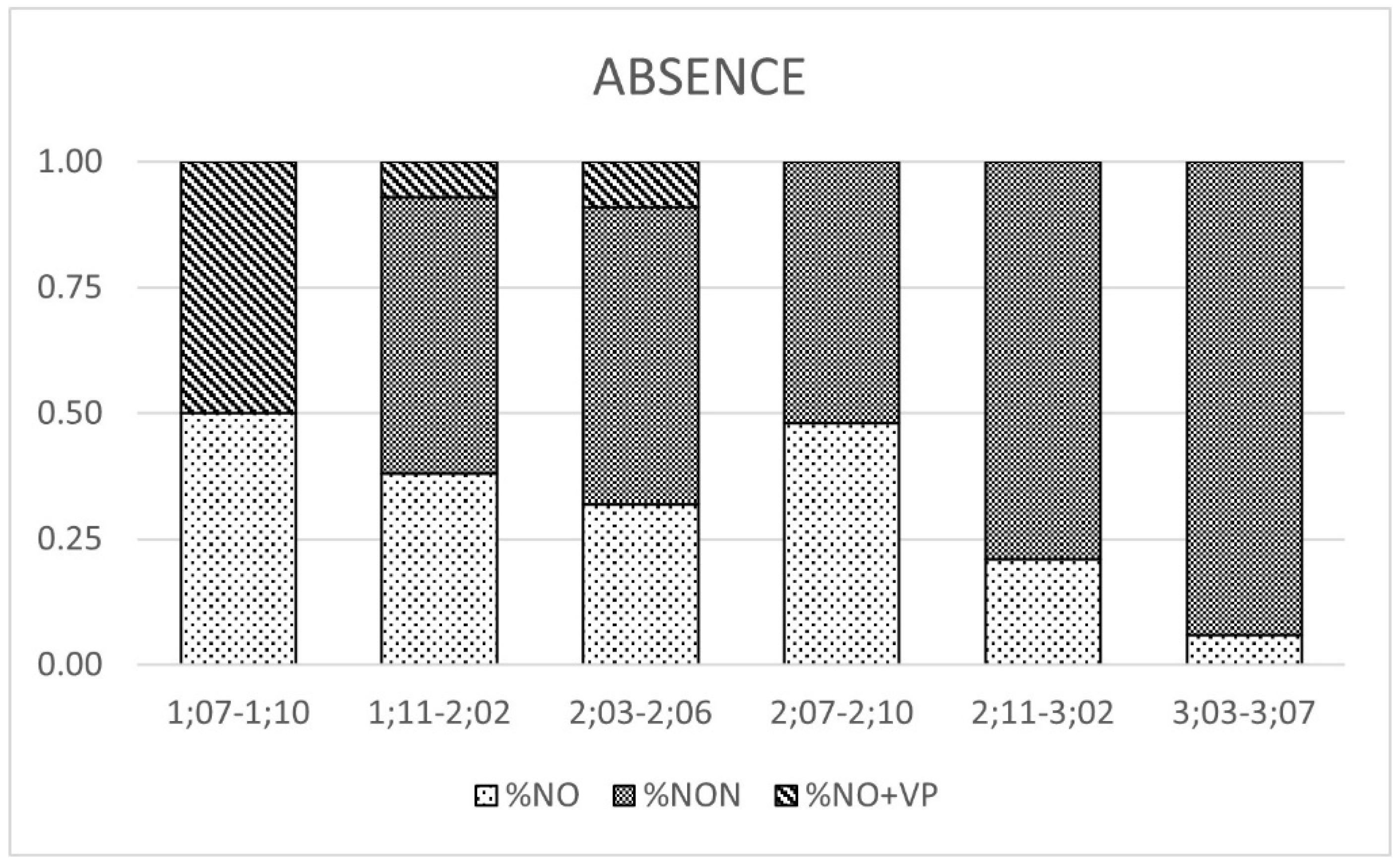

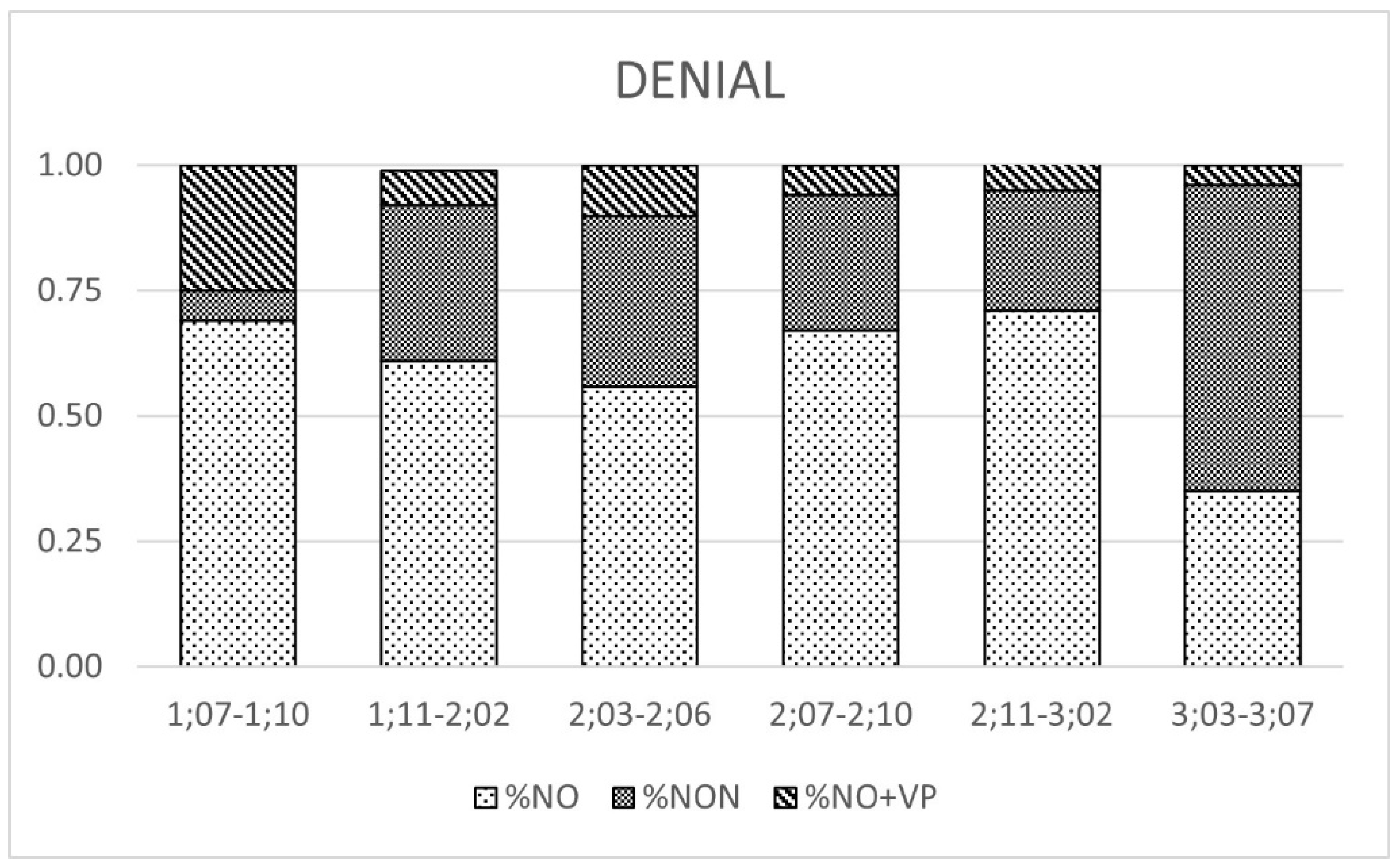

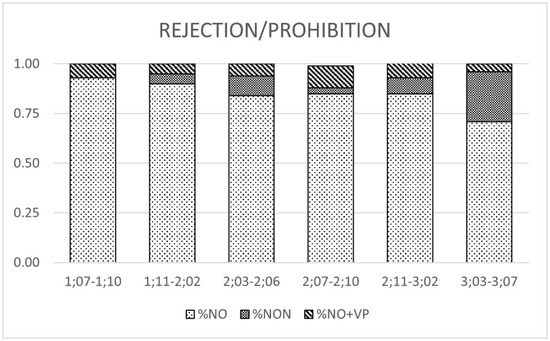

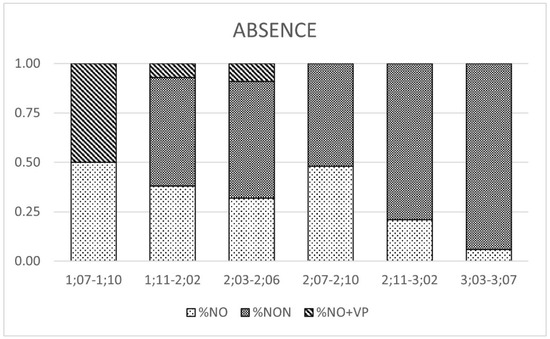

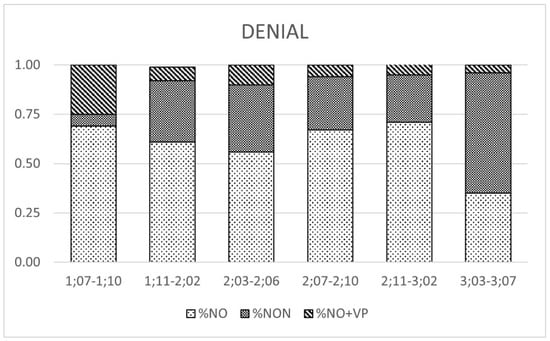

Having depicted the emergence of negation functions, we now turn to the use of negators for the expression of these functions in Child Italian. Table 4 contains the average proportions of the three negation constructions coded for each function; the developmental trend for each function is also represented in Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5. Children’s data are reported cumulatively in each age range.

Table 4.

Average proportions of negators within functions in the considered age intervals.

Figure 3.

Average proportional frequency of negators for rejection/prohibition.

Figure 4.

Average proportional frequency of negators for absence.

Figure 5.

Average proportional frequency of negators for denial.

Rejection/Prohibition. The average proportional use of negators for the expression of rejection (and prohibition) across age intervals is reported in Figure 3.

As observed in Analysis 1, during the age range 1;07–1;10, anaphoric no is the predominant negator in all children’s speech. Table 4 shows that no is mainly deployed with the function of rejection/prohibition (almost all rejections/prohibitions are expressed with no constructions at this age, see example 13). By 1;11–2;02, no is still the predominant negator used to express rejection/prohibition, representing 90% of the negations uttered by the four children.

| (13) | MOT: | cerco io. |

| ‘I search’ | ||

| CHI: | no, lo cerco io. | |

| no, it search I | ||

| ‘No, I search it’ | ||

| (Rosa 2;02, MLU 2.64) | ||

However, across the successive intervals, rejections/prohibitions are increasingly conveyed via non and no+VP constructions, too. For instance, in the case of Rosa, the first occurrence of non utterances used to express rejection appears at 2;04:

| (14) | MOT: | dai si pettina a modino, la bambolina. |

| ‘Come on, you have to comb the doll nicely’ | ||

| CHI: | non voglio. | |

| not want | ||

| ‘I do not want’ | ||

| (Rosa 2;04;23,6 MLU 1.75) | ||

The frequency increase in non is almost constant across children’s development, reaching 25% of instances of negation at 3;03–3;07, which shows that sentential negation is progressively mastered by children and used with all functions at this age. On the other hand, the use of no+VP increases only until sentential negation with non is more accurately expressed, at around 3 years, and shows a decrease in the last two age intervals. This pattern is not surprising since the no+VP construction is non-target-like but represents instead an intermediate step in the acquisition of sentential negation with the negator non.

Absence. The average proportional use of negators for the expression of absence across age intervals is reported in Figure 4.

The expression of absence also exhibits a clear tendency of development, showing that children learn to master negation constructions with non (e.g., non c’è ‘there isn’t’) and progressively abandon constructions with no for the expression of this function, especially from 3 years of age onwards. For instance, in Rosa’s speech, the first instances of non used with the function of absence is already attested at 2;01:

| (15) | MOT: | e il coltellino e la forchettina dove sono? |

| ‘And the little knife and the little fork, where are they?’ | ||

| CHI: | no lo so. | |

| no it know | ||

| ‘I no know it’ | ||

| CHI: | là non c’è. | |

| there not there is | ||

| ‘There, there is not’ | ||

| (Rosa 2;01, MLU 2.64) | ||

After 3, children tend to prevalently use the negator non for the expression of absence; on the contrary, no+VP is used in the earliest age intervals but is abandoned at later stages (since 2;07) when non becomes the dominant negator for the expression of absence (94%).

Denial. The average proportional use of negators for the expression of denial across age intervals is reported in Figure 5.

Although denial is mastered by children later than rejection/prohibition, the use of negators for its expression follows the same developmental pattern that emerged for the other functions. Indeed, denial is mainly expressed via no and no+VP in the first age interval (1;7–1;10). Examples of these constructions from Diana’s speech are reported in (16) and (17).

| (16) | AUN: | è uscito? |

| ‘Did he go out?’ | ||

| CHI: | no. | |

| (Diana 1;08, MLU 2.3) | ||

| (17) | INV: | lascia pure che faccia. |

| ‘Let her do it’ | ||

| CHI: | no no scrive. | |

| no no writes | ||

| ‘No (it) no writes’ | ||

| (Diana 1;10, MLU 2.6) | ||

The first instances7 of non with the function of denial appear in the age interval 1;11–2;02, but this negator is still quite rare in children’s speech at around 2 years of age. Below is a rare instance, extracted from Rosa’s speech at 2;01.

| (18) | MOT: | l’hai rotto? |

| ‘Did you break it?’ | ||

| CHI: | no non è rotto. | |

| no not is broken | ||

| ‘No, it is not broken’ | ||

| (Rosa 2;01, MLU 1.4) | ||

From this age onwards, non is also occasionally used for the expression of inability to carry out a given action and lack of knowledge (i.e., epistemic negation): both functions are classified in the macro-category of denial in the current analysis.

| (19) | MOT: | te lo mette mamma. |

| ‘Mom will put it on you’ | ||

| CHI: | non mi riesce. | |

| not to me does | ||

| ‘I can not do it’ | ||

| MOT: | a te non ti riesce? | |

| ‘You cannot do it?’ | ||

| (Rosa 2;01, MLU 1.4) | ||

At 2;03–2;06, the proportion of no utterances slightly decreases for the expression of denial, but they remain quite frequent throughout the following age ranges. In the age interval 2;07–3;02, indeed no is still the predominant negator used in denial contexts (interestingly, instead, non constructions have already become dominant for the expression of absence at this age). It is in the last interval, at 3;03–3;07, that denial is more consistently expressed by non constructions, which eventually surpass in frequency no constructions. As for the no+VP utterances, the same pattern found for the other functions is observed since they appear in concurrence with non utterances, being initially more frequent in the speech sample than the target forms with non. After a few months, however, they begin to decrease in frequency as the number of non constructions increases.

3.3. Analysis 3: Emergence of Negative Concord Constructions

In this final analysis we consider the emergence of negative concord constructions and the development in the use of the neg-words niente, nessuno and nulla. Although only a few occurrences have been found in the transcriptions we considered, as reported in Table 2 (Section 3.1), it should be observed that all four children use NC constructions.

The first child to produce them is Diana with two occurrences at 2;0;2 (MLU 2.96), one at 2;0;17 (MLU 3.89) and one at 2;01 (MLU 3.94). Notice that in three out of four occurrences, her negative concord constructions can be traced back to a phenomenon of echolalia since she repeated the interlocutor’s utterance (in all three cases the neg-word is niente). Only one structure is produced autonomously by the child, reported in (20).

| (20) | MOT: | ci vuoi ancora gli sportelli? |

| ‘Do you still want the car doors?’ | ||

| CHI: | no, quali sportelli? | |

| ‘No, which car doors?’ | ||

| CHI: | no non ce n’è nessuno. | |

| no not there is n-any | ||

| ‘No, there isn’t any’ | ||

| CHI: | ecco nessuno! | |

| here n-any | ||

| ‘Here, no one!’ | ||

| (Diana 2;01, MLU 3.94) | ||

Diana uses another NC construction at 2;06 (MLU 5.52):

| (21) | CHI: | Pinocchio ha detto di bugie! |

| ‘Pinocchio told lies’ | ||

| CHI: | non dici niente? | |

| not say n-thing? | ||

| ‘Don’t you say anything?’ | ||

| (Diana, 2;06, MLU 5.52) | ||

In her speech, NC is realized more frequently with niente (four out of five tokens), followed by nessuno (one token); the neg-words nulla, niente and nessuno are never used in isolation.

In the case of Rosa, whose acquisition path was monitored from 1;07 to 3;03, an interesting development in the use of neg-words and NC is observed. Over the time period analyzed, Rosa produces a total of 15 instances of negative concord, of which 14 include the neg-word nulla. The only NC construction with the neg-word nessuno is a clear instance of echolalia and therefore will not be discussed.

In the age range 1;11–2;02, Rosa correctly uses the neg-word nulla in response to her mother’s questions to convey a negative semantic meaning, such as for instance to deny the occurrence of an action:

| (22) | MOT: | Rosa cosa hai fatto? |

| ‘Rosa, what have you done?’ | ||

| CHI: | nulla | |

| n-thing | ||

| ‘Nothing’ | ||

| (Rosa 2;01;29, MLU 1.50) | ||

The first two instances of negative concord appear in the age range 2;03–2;06, and are in the incorrect form 0-nulla, as illustrated in (23):

| (23) | CHI: | ha nulla in mano?8 |

| has n-thing in hand? | ||

| ‘Does (she) have anything in hand?’ | ||

| MOT: | non c’ha nulla in mano amore, nulla | |

| not has n-thing in hand, love, n-thing | ||

| ‘(She) doesn’t have anything in hand, love, anything’ | ||

| (Rosa, 2;04;23, MLU 1.75) | ||

In the age interval 2;7–2;10, incorrect constructions are still predominant in Rosa’s speech sample, accounting for 85% of the negative concord utterances. Of the seven negative concord sentences produced by Rosa, five are in the form 0-nulla and one contains the negator no (24). The first correct instance of negative concord (25) is at 2;07.

| (24) | CHI: | no vuole nulla. |

| no wants n-thing | ||

| ‘(She) no wants anything’ | ||

| (Rosa 2;09;04, MLU 2.87) | ||

| (25) | CHI: | non capisce nulla. |

| not understands n-thing | ||

| ‘(She) does not understand anything’ | ||

| (Rosa 2;07;26, MLU 2.78) | ||

In Analysis 1, we have seen that exactly from this age range onwards, Rosa begins to use non consistently as a sentential negator, while the incorrect form no+VP declines. A similar development trend can be observed here: from this moment on, the number of correct negative concord constructions increases, and in the final speech sample (3;03–3;07) all the five instances produced by the child are correct.

A similar development is observed in Martina: at 2;03;01 she is still not able to produce NC correctly and she utters the neg-word in isolation resulting in an error, as reported in (26):

| (26) | MOT: | costì chi c’è? |

| ‘Costi, who is there?’ | ||

| CHI: | c’è nessuno. | |

| there is n-body | ||

| ‘There is no one’ | ||

| (Martina 2;03;01, MLU 2.55) | ||

Only a couple of weeks later, however, a proper NC construction is observed:

| (27) | MOT: | si legge questo libro qui |

| ‘Let’s read this book here’ | ||

| MOT: | questo ancora non l’hai visto! | |

| ‘You haven’t seen this one yet!’ | ||

| CHI: | no perché non c’è nulla! | |

| no because not there is n-thing | ||

| ‘No because there is nothing’ | ||

| (Martina 2;03;22, MLU 2.64) | ||

In the same period, niente is used in isolation in a proper context:

| (28) | MOT: | alle puppine della mucca cosa fa? |

| ‘To the cow’s udders, what does he do?’ | ||

| CHI: | niente. | |

| n-thing | ||

| ‘Nothing’ | ||

| (Martina 2;03;22, MLU 2.64) | ||

No other NC constructions or other instances of niente, nulla and nessuno are observed in her speech. Camilla, instead, starts to produce NC quite late, but without committing errors (eight tokens in total), mainly with the neg-word niente (seven tokens; one token of nessuno). The first instance is observed at 3;01 (MLU 4.49).

| (29) | MOT: | che si mangia a questa scuola qui? |

| ‘What do you eat at this school here?’ | ||

| CHI: | eh, ora non si mangia niente. | |

| eh, now not si-IMP eat n-thing | ||

| ‘Eh, now you don’t eat anything’ | ||

| (Camilla 3;01, MLU 4.49) | ||

The neg-word niente is correctly used in isolation, as shown below, and no wrong constructions are observed.

| (30) | MOT: | non lo sai a scuola cosa hai fatto? |

| ‘Don’t you know what you did at school?’ | ||

| CHI: | niente. | |

| n-thing | ||

| ‘Nothing’ | ||

| (Camilla, 2;11, MLU 3.47) | ||

Summarizing, negative concord constructions are first produced by all children between age 2 and 3 and even with a relatively low MLU; the most common neg-words used are niente and nulla, whereas nessuno is less frequent. In some cases, children show an incorrect use of the neg-words without the negator non before producing the correct NC construction. The neg-words are instead used properly in isolation early on.

4. Discussion

The goal of this study was to gather a preliminary picture of how negation is acquired in Child Italian, that is, how children move from the earliest use of negative particles during the single-word utterance period to the mastering of complex syntactic structures, which can also include multiple negative elements, as with negative concord. As outlined above, indeed, the acquisition of negation in Italian is underinvestigated, and the studies available are limited to the, rather criticized, contribution by Volterra and Antinucci (1979). With the principal aim of filling this gap in the literature, we conducted an in-depth analysis using the CHILDES database (MacWhinney 2000) to extract longitudinal data of four monolingual Italian children for an observation period ranging from 1;07 to 3;04 years of age. We examined three specific aspects of negation development, which had already been investigated for other child languages, in order to see whether the same acquisitional patterns hold also for Italian or whether there may be language-related differences.

In our first analysis, we focused on the development of negative constructions in Child Italian by examining the children’s use of different negators (the anaphoric no and the sentential form non) during the single- and the multiword utterance period. What we observed is that the anaphoric form no is the predominant negator used by children during the first acquisitional periods. This is not surprising if we consider that our investigation also examined very early stages of language acquisition, in which children most often express themselves using single or few words. At a later point in time, no constructions decrease proportionally in favor of a more widespread use of non as a negative marker: however, they always remain predominant in numerical terms as evidenced by the raw numbers of occurrences reported in Table 2. We also considered non-target no+VP forms, where no is used incorrectly to express sentential negation (e.g., no lo so, lit. ‘I don’t know’). However, the use of these ungrammatical forms is limited in time, and gradually decreases in the children’s speech as they begin to make consistent use of the correct non construction. Significantly, this developmental trend seems to be intrinsically related to the increase in the child’s MLU: in fact, if on the one hand we have observed that all four children moved from anaphoric to sentential forms of negation, on the other hand the temporary use of no+VP forms persisted longer in those children with a lower MLU (e.g., Rosa).

This evidence speaks in favor of an intermediate step of language development during which children overextend the anaphoric negator no to express sentential negation. In line with what was assumed by Cameron-Faulkner and colleagues (2007) for English, our data indicate that Italian children do not interchangeably use the two negators in their speech production: rather, they prefer to use lexical items already acquired (i.e., no, also phonologically simpler than non) for the expression of more complex negative meanings and structures. This assumption is supported by the fact that the no+VP forms were attested longer and more frequently in children with a low MLU, who also started producing non constructions at a later time. These results also confirm the developmental sequence proposed for the distribution of sentential negation in English (Felix 1987) by extending those observations to Child Italian. The first instances of negation in children’s multiword production present the anaphoric no in sentence external position, which then moves in close proximity to the VP, giving rise to the ungrammatical no+VP structure used to express sentential negation. Around 2;7, these non-target forms diminish in favor of non constructions, becoming the predominant form.

In the second analysis, we examined the emergence of the different functions of negation in order to understand for which communicative intentions negation is primarily used in Child Italian, and whether the development of the examined negators may differ within each function. For this analysis, we considered the three macro-functions of negation (i.e., rejection/prohibition; absence; denial) identified by Pea (1980) and Bloom (1970) for the single- and multiword speech production, respectively. The data we examined clearly indicate that, during the first age intervals (1;07–2;02), negation is mainly used to express rejection/prohibition by all children. Then, this function progressively decreases, in correspondence with an increase in the use of negation to express absence and denial. Both of these functions are attested already during the first age interval considered (albeit in a very limited percentage). However, while denial steadily increases, becoming the predominant function at three years of age, absence is infrequent in the child’s speech. Similar to what was observed in the first analysis, the emergence and subsequent development of new functions is faster when the child has a higher MLU.

Our data collected for Child Italian provide partial confirmation of the acquisition order of negative meanings found in other languages (mainly English, as outlined in the introduction) with rejection/prohibition being the first function expressed by the child and denial becoming the predominant function only later on (Pea 1980; Bloom 1970). Unlike for English, the first instances of denial appear earlier in Child Italian, already at about one and a half years of age. It must be said, however, that the first sentences coded as denial are often instances of epistemic negation and inability—rather than truth-functional judgements about previous statements, in line with the trajectory of development assumed by Gopnik and Meltzoff (1985). This can explain their early occurrence in our data sample. For what concerns absence, the data reveal a delay in the expression of this function, which was attested very little and especially at later stages through the negator non. This is arguably related to both formal and more contextual reasons. First, it could be partly due to the nature of the corpus, as the interview setting may not have provided adequate contexts of utterance for this function. Second, the concept of absence is often expressed by younger children through other Italian expressions/words (e.g., più, lit. ‘more’ or via, lit. ‘away’) that we did not include in the investigation, as they are not related to the use of a negator. This, together with the fact that the Italian negative construction used to express absence (e.g., non c’è, lit. ‘there isn’t’) is morphosyntactically more complex than other negative expressions and probably also more expensive in terms of cognitive processing, may explain why this function is found more often when children begin to use the negator non. As for the development of the different negators, a similar trend has been reported across functions: no is the predominant negator during the first stages of acquisition but, in subsequent intervals, its use decreases in favor of no+VP and non constructions. However, the former are progressively abandoned when the expression of sentential negation with non is mastered. These results provide further evidence that the acquisition process of sentential negation is gradual and involves an intermediate step of non-target constructions for all functions.

In the third and last analysis, we investigated the emergence of negative constructions including the negative indefinites niente, nulla ‘nothing’ and nessuno ‘nobody/not any’. In the corpus, we found few occurrences of NC constructions: this is not surprising as they are quite complex both from a syntactic and semantic point of view, and thus they are likely to be mastered later. Indeed, the data collected indicate that children seem to start producing these structures between two and three years of age. The earliest structures produced by children include syntactic errors such as the incorrect use of the neg-word without the negator non, and the use of the anaphoric form no as negative marker. While we have already discussed the development of negators in the child’s speech, it is interesting to observe that children are able to produce correct negative sentences including neg-words in isolation very early on: this indicates that they have already learned that the negative indefinites convey negative semantics. The corresponding errors reported for NC constructions are arguably due to the fact that children, since they have not yet developed an adult-like competence of negative concord, resort to negative constructions that they have already acquired in the attempt to express more complex negative structures.

Lastly, no double negation constructions were attested in the children’s speech samples, attesting to the fact that children do not master yet this complex construction in the age interval considered. This is in line with what has been reported in the literature: double negation, which is extremely marked from both a pragmatic, prosodic and syntactic perspective, is learned by children only at a much later age, at around 7, when they start to correctly interpret and produce these marked constructions (Tagliani 2019). This late occurrence is also probably related to the fact that, given their restricted usage conditions, double negation structures are infrequent in everyday speech and also in the adult input.

5. Conclusions

This work represents the first exploratory study of the acquisition of negation in Child Italian, and it provides relevant insights into different aspects and structures involved in the process, such as the development of negators and negative constructions, the acquisition of negative functions and their varying proportions of use, and the emergence of negative concord structures. Results indicate that the acquisition of negation in production is a gradual process, characterized by a consistent developmental pattern across the children considered, with minor differences that arguably relate to differences in the children’s language development (as indicated by their MLUs in the age intervals). Our data mainly confirm cross-linguistic evidence indicating a progressive development of structures and functions of negation, with intermediate stages characterized by incorrect forms, though minor language-related differences have been observed.

For future research it would be interesting to explore some acquisitional aspects that were not addressed in the present work. As suggested by the reviewers, it would be useful to extend the investigation of the distribution of the different negators to the adult language, so as to gain a better understanding of children’s form–function development of negation. In addition, we could include in the analysis other Italian expressions and words that are not proper negators but are often used by younger children to express the concept of absence (e.g., più, lit. ‘more’ or via, lit. ‘away’): such study would allow us to understand in which contexts, when and for how long children resort to these alternative forms to express absence. Another possible trajectory would be to extend the investigation to beginner learners of L2 Italian, to see whether this acquisitional stage may share some tendencies with L1 acquisition. Moreover, it would be interesting to conduct contrastive analyses between different Child languages by adopting the same methods and criteria as those deployed for the current study. Finally, having a more recent corpus would allow extending the number of participants and widening the observation period above three and a half years of age in order to provide a broader picture of the development of multiple negation constructions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.T., M.V. and C.M.; methodology, M.T., M.V. and C.M.; software, M.T., M.V. and C.M.; formal analysis, M.T., M.V. and C.M.; investigation, M.T., M.V. and C.M.; resources, M.T., M.V. and C.M.; data curation, M.T., M.V. and C.M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.T., M.V. and C.M.; writing—review and editing, M.T., M.V. and C.M.; funding acquisition, C.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC was funded by Fondi di Ricerca Scientifica (FUR) A.F. 2017-2022, Chiara Melloni (Department of Cultures and Civilizations).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The chat transcripts analyzed in this study are part of the open-source CHILDES dataset (https://childes.talkbank.org/ accessed on 25 April 2022).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1. | The taxonomy proposed by Choi (1988) distinguished nine semantic and pragmatic functions of negation compared to Bloom (1970)’s three in order to provide a more fine-grained picture of the form-function relationship. | |||||||||||||||

| 2. | As correctly noted by an anonymous reviewer, while anaphoric negation is used, at least in some Child languages, in place of the sentential one (with respect to the lexical item used and/or its position), there are no cases where sentential negation is used by children as anaphoric negation. | |||||||||||||||

| 3. | The primary stress of the sentence must be located on the neg-word placed preverbally. | |||||||||||||||

| 4. | All the forms that in the original transcriptions were indicated as phonological errors have been reported using the correct form in all the examples throughout the paper to improve readability. | |||||||||||||||

| 5. | The number of occurrences reported for the different age ranges is constrained by the fact that some chats were very short compared to others, as they concerned spontaneous speech production. | |||||||||||||||

| 6. | When there are two recordings in the same month, the day in which they took place is also indicated. | |||||||||||||||

| 7. | The first instance of non with function of denial in our data sample is actually attested in Martina’s speech at 1;9.

| |||||||||||||||

| 8. | However, it should be noted that the sentence produced by the child in (23) is grammatically accepted in Tuscan speech varieties to express semantic negation: thus, it could be a dialectal expression rather than an incorrect NC form. |

References

- Antelmi, Donna. 1997. La Prima Grammatica Dell’italiano. Indagine Longitudinale Sull’acquisizione Della Morfosintassi Italiana. Bologna: Il Mulino. [Google Scholar]

- Bellugi, Ursula. 1967. The Acquisition of the System of Negation in Children’s Speech. Ph.D. dissertation, Harvard Graduate School of Education, Cambridge, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom, Lois. 1970. Language Development: Form and Function in Emerging Grammars. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom, Lois. 1991. Language Development from Two to Three. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron-Faulkner, Thea, Elena Lieven, and Anna Theakston. 2007. What Part of No Do Children Not Understand? A Usage-Based Account of Multiword Negation. Journal of Child Language 34: 251–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Choi, Soonja. 1988. The Semantic Development of Negation: A Cross-Linguistic Longitudinal Study. Journal of Child Language 15: 517–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipriani, Paola, Pietro Pfanner, Anna Maria Chilosi, Lorena Cittadoni, Alessandro Ciuti, Anna Maccari, Natalia Pantano, Lucia Pfanner, Paola Poli, Stefania Sarno, and et al. 1989. Protocolli Diagnostici e Terapeutici Nello Sviluppo e Nella Patologia Del Linguaggio. Pisa: Italian Ministry of Health, Stella Maris Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Déprez, Viviane, and Amy Pierce. 1993. Negation and Functional Projections in Early Grammar. Linguistic Inquiry 24: 25–67. [Google Scholar]

- Dimroth, Christine. 2010. The Acquisition of Negation. In The Expression of Negation. Edited by Laurence Robert Horn. Berlin and New York: De Gruyter Mouton, pp. 39–71. [Google Scholar]

- Drozd, Kenneth F. 1995. Child English Pre-Sentential Negation as Metalinguistic Exclamatory Sentence Negation. Journal of Child Language 22: 583–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Felix, Sascha. 1987. Cognition and Language Growth. Michigan: Foris Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Giannakidou, Anastasia. 1997. The Landscape of Polarity Items. Groningen: Rijksuniversiteit. [Google Scholar]

- Giannakidou, Anastasia. 2000. Negative … Concord? Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 18: 457–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopnik, Alison, and Andrew N. Meltzoff. 1985. From People, to Plans, to Objects: Changes in the Meaning of Early Words and Their Relation to Cognitive Development. Journal of Pragmatics 9: 495–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidetti, Michèle. 2005. Yes or No? How Young French Children Combine Gestures and Speech to Agree and Refuse. Journal of Child Language 32: 911–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horn, Laurence Robert. 1989. A Natural History of Negation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, Available online: https://web.stanford.edu/group/cslipublications/cslipublications/site/1575863367.shtml (accessed on 10 September 2021).

- Hummer, Peter, Heinz Wimmer, and Gertraud Antes. 1993. On the Origins of Denial Negation. Journal of Child Language 20: 607–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jordens, Peter. 1987. Neuere Theoretische Ansätze in Der Zweitspracherwerbsforschung. Studium Linguistik 1987: 3165. [Google Scholar]

- Klima, Edward S., and Ursula Bellugi. 1966. Syntactic Regulation in the Speech of Children. In Psycholinguistic Papers. Edited by John Lyons and Roger J. Wales. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, pp. 183–203. Available online: https://www.scirp.org/(S(351jmbntvnsjt1aadkposzje))/reference/ReferencesPapers.aspx?ReferenceID=1339882 (accessed on 1 September 2021).

- Labov, William. 1972. Negative Attraction and Negative Concord in English Grammar. Language 48: 773–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacWhinney, Brian. 2000. The CHILDES Project: Tools for Analyzing Talk: Transcription Format and Programs, 3rd ed. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers, vol. 1, p. xi, 366. [Google Scholar]

- McNeill, David, and Nobuko B. McNeill. 1973. What Does a Child Mean When He Says ‘No.’. In Studies in Child Language Development. Edited by Charles Ferguson and Dan Isaac Slobin. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, pp. 619–27. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Karen. 2012. Sociolinguistic Variation in Brown’s Sarah Corpus. Paper presented at Boston University Conference on Language Development (BUCLD) Proceedings 36, Boston, MA, USA, November 4–6; Edited by Alia Biller, Esther Chung and Amelia Kimbal. Somerville: Cascadilla Press, pp. 339–48. [Google Scholar]

- Moscati, Vincenzo. 2020. Children (and Some Adults) Overgeneralize Negative Concord: The Case of Fragment Answers to Negative Questions in Italian. University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics 26: 1. Available online: https://repository.upenn.edu/pwpl/vol26/iss1/20 (accessed on 20 November 2021).

- Pagliarini, Elena, Stephen Crain, and Maria Teresa Guasti. 2018. The compositionality of logical connectives in child Italian. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research 47: 1243–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagliarini, Elena, Oana Lungu, Angeliek van Hout, Lilla Pintér, Balàzs Surànyi, Stephen Crain, and Maria Teresa Guasti. 2022. How adults and children interpret disjunction under negation in Dutch, French, Hungarian and Italian: A cross-linguistic comparison. Language Learning and Development 18: 97–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pea, Roy D. 1980. The Development of Negation in Early Child Language. In The Social Foundations of Language and Thought. Edited by David R. Olson. New York: Norton & Company, pp. 156–86. [Google Scholar]

- Sano, Tetsuya, Hiroyuki Shimanda, and Takaomi Kato. 2009. Negative Concord vs. Negative Polarity and the Acquisition of Japanese. Paper Presented at Third Conference on Generative Approaches to Language Acquisition North America, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT, USA, September 4–6; Edited by Jean Lenore Crawford, Koichi Otaki and Masahiko Takahashi. Somerville: Cascadilla Proceedings Project, pp. 232–40. [Google Scholar]

- Slobin, Dan Isaac. 1985. Crosslinguistic Evidence for the Language Making Capacity. In The Crosslingustic Study of Language Acquisition Volume 2: Theoretical Issues. Edited by Dan Isaac Slobin. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers, pp. 1157–249. [Google Scholar]

- Stern, Gustaf. 1964. Meaning and Change of Meaning: With Special Reference to the English Language. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, Available online: http://archive.org/details/meaningchangeofm00ster (accessed on 5 October 2021).

- Tagliani, Marta. 2019. The Acquisition of Double Negation in Italian. In Language Use and Linguistic Structure. Proceedings of the Olomouc Linguistics Colloquium 2018. Olomouc: Palacký University, pp. 109–26. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton, Rosalind, Anna Notley, Vincenzo Moscati, and Stephen Crain. 2016. Two negations for the price of one. Glossa: A Journal of General Linguistics 1: 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Kampen, Jacqueline. 2010. Acquisition preferences for negative concord. In The Evolution of Language. Edited by Andrew D. M. Smith, Marieke Schouwstra, Bart de Boer and Kenny Smith. Singapore: World Scientific, pp. 321–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Valin, Robert. 1991. Functionalist Linguistic Theory and Language Acquisition. First Language 11: 7–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volterra, Virginia, and Francesco Antinucci. 1979. Negation in Child Language: A Pragmatic Study. In Development Pragmatics. Edited by Elinor Ochs Keenan and Bambi Schieffelin. New York: Academic Press, pp. 281–303. [Google Scholar]

- Weissenborn, Jürgen, Maaike Verrips, and Ruth Berman. 1989. Negation as a Window to the Structure of Early Child Language. Nijmegen: Ms., Max Planck Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Wode, Henning. 1977. Four Early Stages in the Development of Li Negation. Journal of Child Language 4: 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]