Abstract

This study analyses the variety of the language used in textbooks for teaching Italian as a second/foreign language. These books use a language much closer to written than to spoken Italian and do not consider its varieties, providing examples and exercises with a “neutral” standard that speakers rarely use in everyday speech. The aim of this study is to provide a critical review of pronunciation sections in current L2 Italian textbooks, in the light of a renewed and growing interest in the study of the Italian language, not only by students with a migrant background in Italy, but also by second and third-generation emigrants who want to learn Italian to recover their roots. Thirty-two Italian textbooks were examined, considering some geolinguistic variables. The general tendency seems to be the introduction of some neo-standard Italian features. As far as the phonetic–phonological level is concerned, this is probably still insufficient because of the complexity of the Italian linguistic repertoire. Our analysis further suggests the inadequacy of notions such as (neo-)standard Italian for teaching purposes in the linguistic space of global Italian.

1. Introduction

The Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR) is one of the most used guidelines to describe language proficiency results of learners. It is divided into six levels from A1 (for beginners) up to C2 (for those who are proficient in the language). Since 2018, phonetic–phonological competence has finally been formalised within this communicative language competence framework1 (CEFR, 2018). Phonetic–phonological competence is now specified in different levels (A1–C2), from the correct pronunciation of a few words up to the correct intonation at both the lexical and phrasal levels and the correct use of intonation and rhythm in relation to the morphosyntactic, semantic, and pragmatic levels. These changes have long been requested by foreign language teachers. In fact, several issues have emerged in the way Italian is taught as a foreign or second language. For instance, according to Balboni (2008, p. 65), the phonemes and prosody are not explicitly taught; the teachers themselves become aware of their regional intonation only when they hear their recorded voice; the existence and distribution of variation phenomena such as the opposition between mid-open and mid-close ‘e’ and ‘o’ are not either known or taught by Italian teachers.

Although almost seven years have passed since the CEFR was revised, in the textbooks for the study of Italian as a second (L2) or foreign language (FL), it is still not specified how learners should acquire the linguistic competence needed to establish the phonemic differences between their mother tongue and the target language2, nor is it indicated at what level some phonemes should be acquired rather than others, or what method(s) should be used to build this competence, delegating the choice to the teacher3.

It is important to distinguish acquisition in informal contexts from acquisition in formal contexts. The first occurs when somebody learns a second language (L2) subconsciously through daily direct interactions with native speakers of that language, specifically in the local variety. In contrast, the acquisition in formal contexts occurs when students acquire a foreign language (FL) in their native country through formal education provided by a teacher, who is normally expected to teach the standard variety of the language.

Since Italian is a language characterised by significant regional diversity, there is general agreement that the standard pronunciation is for the most part only used by voice professionals, and is not at all typical of average speakers (Cerruti et al., 2017; De Pascale et al., 2017), so that teaching Italian as an L2/FL strictly depends on the abilities and methodological choices of the teacher. Therefore, as far as Italian is concerned, the difference between acquisition in informal contexts and acquisition in formal contexts is not so marked: learners who live in Italy will acquire the linguistic variety of the place where they live, while international students outside Italy will learn the linguistic variety spoken and used by the teacher, reflecting their own regional variety of Italian or, in cases of non-native teachers, the variety that they have been taught.

The aim of the present study is to analyse the language variety employed in textbooks for teaching Italian as a second/foreign language. Thirty-two textbooks have been chosen from those most widely used and known in the field and examined, considering some pronunciation variables related to geographic location. The general tendency appears to be a gradual adaptation of textbooks to the 2018 indications of CEFR, including parts dedicated to the study of phonetics and some features of the neo-standard. Neo-standard Italian is the common, everyday variety of the Italian language used by most educated speakers, bridging the gap between traditional formal Italian and regional dialects. This variety is characterised by the integration of features from informal speech, notably in its use of pronouns and conjunctions, which has established it as the practical standard for modern media and informal communication (Sabatini, 1985; Berruto, 2012, 2017a, 2017b; Cortelazzo, 2001; D’Achille, 2006; Lorenzetti, 2006). However, a careful analysis of how such a trend is achieved reveals that the results are far from providing a faithful picture of the complexity of the Italian phonetic and phonological repertoire.

2. A Brief History of Spoken and Written Italian

In a study conducted in 1977 aimed at determining whether there was a process of standardisation of the Italian language, Galli de’ Paratesi (1977) recorded and transcribed teachers from different regions of Italy; the transcribed texts were then analysed by fellow professors and linguists. It was extremely difficult for them to understand where the teachers were from. Then, the recorded speech was reproduced. Everyone immediately understood at least the region of origin and, because of different intonation patterns, different pronunciation of close- and open-mid vowels, different use of both consonant and vowel duration, different application of phonosyntactic doubling, and other phonological processes. Some linguists were also able to identify the city of origin of the interviewed teachers. According to the author of the study, her results showed that standard Italian exists and that this is represented exclusively in written form4. Differences in intonation, pronunciation, and most phonological processes are not visible in formal writing, but they indicate specific spoken regional varieties.

Thus, the Italian spoken in Italy is the result of an attempt at generalising the written language (literary Tuscan5 Italian) across the different regions. However, the written Tuscan variety has for a long time been very different from the spoken language, particularly outside Tuscany, but also from the variety spoken in Tuscany, according to most scholars; it has been considered a model, and for this reason it has largely been both definite and free from normal evolution and external influences—it is prescriptive and normative (Galli de’ Paratesi, 1984). Furthermore, once more, according to Galli de’ Paratesi (1977, p. 169) and most other scholars, it is written, but it is not spoken in any Italian region6 or by any social class. There is general agreement that the standard pronunciation is, for the most part, only used by voice professionals and is not at all typical of average speakers (Cerruti et al., 2017; De Pascale et al., 2017, but see also Bertinetto & Loporcaro, 2005). Nevertheless, it is well known that standardisation is always a trend and never an incontrovertible condition.

With the help of simple grammatical and lexical explanations, examples of the historical development of written Italian can be found by students of the language when they read old texts such as the works of Dante, Petrarch, Boccaccio, and Manzoni. While this would be impossible in a French, English, or German school, it is possible in the Italian context because the modern spoken language is the logical consequence of the old written form, which has a normative and conservative character and has undergone very few changes7 in recent centuries. While some scholars might disagree, De Mauro (2017, p. 50) argues that the differences between the language used by Petrarch and contemporary Italian mainly pertain to the pronunciation level.

Focusing our attention on graphic accents, we might wonder whether the loss of phonological opposition among some Italian sounds has been eased by the absence of differentiation in the written language. Looking at several Italian language history and gram-mar textbooks (Pizzoli, 2004), it can be noted that there are two normative accents: grave to indicate the mid-open vowels “è” and “ò”, although it is also used with high “ì” and “ù” vowels in words stressed on the last syllable—for example, sì (“yes”), virtù (“virtue”), più (“more”); acute, which is used to represent mid-close vowels “é” and “ó”, for example, trentatré (“thirty-three”). According to the rules of writing, the accent is mandatory in stress-bearing open syllables at the end of words and is optional in other positions.

This tension between written norms and spoken language is deeply rooted in Italy’s unique sociolinguistic history, which lacked a centralised unifying catalyst for centuries.

Ascoli (1880) argues that, in Italy, there was no event that served as a unifier at a linguistic level—as happened, for example, in Germany with the Protestant Reformation8. In 1861, the year of the political–administrative unification of the peninsula, 78% of the population was still illiterate, and it is estimated that the speakers of Italian accounted for only ~2.5%. The use of Italian was an exception, only made possible through education. Conversely, the use of local varieties (referred to as ‘dialects’ in Italy and historically related to Italian) was natural. In the linguistic situation of a newly unified Italy, clear differences emerged not only between regions but also between social classes.

In examining the linguistic history of a country, we cannot ignore the historical events that affected it. In Italy, the use of a common language and the progressive regression of dialects were accelerated by specific events, such as the development of a bureaucratic apparatus for the new state, the need for political propaganda that everyone could understand, the constitution of a national army, industrialisation, some specifically nationalist laws of the 1920s and 1930s in favour of the use of Italian, and urbanisation and the consequent interregional demographic exchanges. In addition to these factors, education and the new mass media—such as the press, radio, television, sound cinema, and theatre9—contributed to the dissemination of the Italian language, which was accompanied by the progressive Italianisation of dialects and the emergence of a continuum of regional varieties10 of Italian with the local dialects and the ‘standard’ at the extremes of this continuum (De Mauro, 2017; Berruto, 2012; Vietti, 2019; Crocco, 2017). Between the two world wars, the linguistic repertoire of Italian speakers consisted of four varieties: common Italian (a basic formal and exclusively written variety of the national language), regional Italian, Italianised dialects, and dialects. At the end of the Second World War, low levels of schooling (60% had not completed primary school education, and 13% were totally illiterate in 1951) reflected the modest ability to use the common language (De Mauro, 2017).

In the second half of the 20th century, however, television had an important influence on linguistic levels; it took on the role of the “school of Italian”, especially in dialect-speaking areas. However, the more widespread use of Italian did not automatically lead to the disappearance of dialects. On the contrary, Italian and its local varieties still co-occur today in certain areas and social classes of the country. In some areas and social classes, the Italo-Romance dialect is even today the naturally acquired mother tongue of children. The dialects are often perceived as the languages of feelings, emotions, and everyday life.

According to Pellegrini (1975, p. 37), an ideal Italian speaker knows and is able to use four basic registers simultaneously, depending on the communicative contexts: dialect, dialectal koinè, regional Italian, and standard Italian. The expression regional Italian emphasises a primary differentiation in linguistic uses—that is, a geographical criterion. However, the expression regional Italian does not sufficiently grasp the complexity of forms, structures, and linguistic behaviours that represent the use of Italian today (Berruto, 2012, p. 17). In the Italian linguistic situation, therefore, the main differentiations are geolinguistic and social. The regional varieties of Italian are basically differentiated at the phonetic and phonological level, as pointed out at the beginning of this section. In Italian schools, the primacy of the written language has led to underestimation (if not voluntary censorship) of regional variations in pronunciation. For example, consider the word “science”. In some regional Italian varieties, the first syllable is pronounced as [ˈʃje]. In others, the pronunciation is [ˈʃe]. Across different regions of Italy, the tonic vowel “e” can be either open [ɛ] or closed [e], and the consonant “z” can be pronounced as voiced affricate [], voiceless affricate [], or even as voiceless and voiced fricative [s] and [z]. All of these different forms are mutually intelligible to speakers and accepted, and each of them reveals the origin of the speaker. Teachers will produce the word “science” according to their regional varieties of Italian (see Crocco, 2017), although they use the written language as a standard and normative form for teaching, which is the same for everybody.

Regional Italian varieties not only show features derived from contact with the dialectal substratum but also features derived from contact among speakers of different regional Italian varieties (Cerruti, 2018).

In the next section, some of the most important and well-known pronunciation differences between (groups of) regional Italian varieties are reviewed and discussed. Subsequently, the analysis of current textbooks for teaching Italian as an L2 or as an FL will target these phenomena in particular, to verify if and how such fundamental aspects of Italian speech variation are taken into account in the pedagogical training of non-native speakers.

3. Regional Variables Included in the Present Review

3.1. The /s/-/z/ Voicing Distinction

In Tuscan and standard Italian, according to Camilli (1965, p. 45), voiceless /s/ is the common pronunciation when the sibilant is geminate, when it occurs word-initally before a vowel (or semi-vowel), and in post-consonant position (polso, “wrist”, [ˈpolso], abside, “apsis” [ˈabside], psicologia, “psychology” [psikoloˈʤia], ansia, “anxiety” [ˈansia]). Voiceless pronunciation is also present at the end of a word (although in this position it can become voiced during fast speech if it precedes a word starting with a voiced consonant, e.g., “gas liquido” [gazˈlikwido]. It is produced as a voiced fricative [z] when it precedes a voiced consonant (sbatto, I bang, [ˈzba:tto] or sdentato, toothless, [zdɛnˈtatɔ]).

In word’s internal intervocalic position, the sibilant is generally produced as voiced by Northern speakers, as voiceless by Southern speakers, and it can be both [s] and/or [z] in Tuscany (uso, “use” [ˈuːzo] and mese, “month” [ˈmɛːse]). Thus, regional variability is recorded in the intervocalic position, and only when it is a singleton. Minimal pairs are possible in intervocalic position only in Tuscany. These minimal pairs include, for example, rosa (“rose” [ˈroːza]) and rosa (past participle of the verb “to erode” [ˈroːsa]); chiese (“churches” [ˈkjɛːze]) and chiese (“(s)he asked” [ˈkjɛːse]). They also include sub-minimal pairs such as ascesi (“ascended” [aˈʃeːsi]) and ascesi (“asceticism” [aˈʃɛːzi]); tesi (past participle of the verb “to stretch” [ˈteːsi]) and tesi (“thesis” [ˈtɛːzi]); or tubercolosi (“tuberculosis patients” [tuberkoˈloːsi]) and tubercolosi (“tuberculosis” [tuberkoˈlɔːzi]). Moreover, in Tuscany and in the north of Italy, the sibilant is predictably voiceless when preceded by a prefix, as in ri-saputo [risaˈpuːto] and in compounds such as semisordo [semiˈsordo] (Romito, 2023, pp. 66–68).

Therefore, in Italian regional variability, the minimal pair /s z/ in intervocalic position is neutralised; in the other contexts, the sibilant has predictable allophonic variants, [s] and [z].

There is another important phenomenon of regional variability concerning sibilants in post-sonorant position: where they are produced as a voiceless affricate [] in Tuscany, in some southern areas, such as Lamezia Terme-Catanzaro, they are produced as a voiced affricate [].

3.2. Stressed and Unstressed Vowels

In Italian, vowel length is not phonemically contrastive, but there are significant phonetic differences in the duration of stressed and unstressed vowels. However, this lengthening is not uniform, and it depends on factors such as the syllable structure and the nature of the following consonants. Vowels are assumed to be long in non-final stressed syllables before short consonant or non-geminate clusters. Furthermore, for instance, stressed vowels in open syllables tend to be longer in the non-final position before a non-geminate consonant or another vowel, while those preceding geminate consonants in closed syllables are typically shorter (Bertinetto & Loporcaro, 2005).

It is possible to distinguish a southern five-vowel system11, i, ɛ, a, ɔ, and u, in which it is not possible to differentiate words such as pesca (“peach”, fruit) and pesca (“(s)he fishes”, verb) [ˈpɛska]. Similarly, a central–northern seven-vowel system, i.e., a, ɔ, o, and u, exists, in which the opposition between the mid-close and mid-open vowels is phonological.

It is superficial, however, to differentiate Italian vowel systems into a five-vowel system and a seven-vowel system; it is not enough to have the same number or even the same elements to support the notion that two vowel systems have the same distribution (Trumper et al., 1991). In fact, although central–northern Italian is characterised by a seven-vowel system, in which the opposition, e, ɛ, o, and ɔ, is functional, it can be noted that their distribution is not uniform. In Florentine Italian, c’era [‘ʧɛːra] is used for “there was” and cèra [ˈʧeːra] for “beeswax”, while in the Italian variety spoken in Rome, the opposite can be noted: cèra [‘ʧɛːra] “beeswax” and c’era [ˈʧeːra] “there was” (Romito, 2003, p. 78).

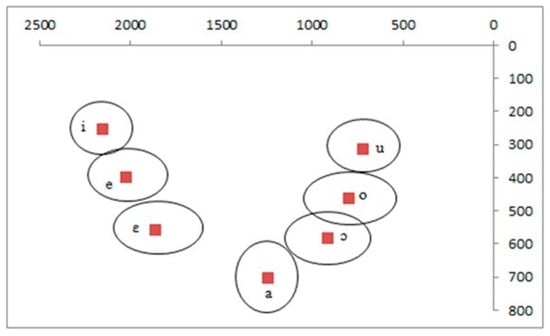

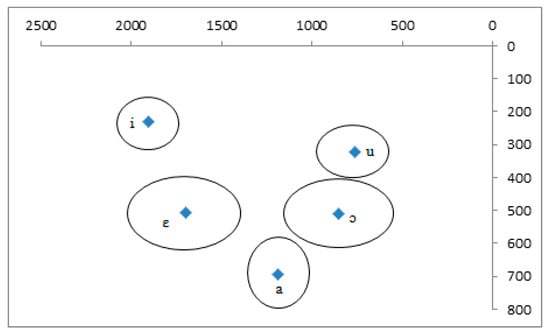

The dispersion areas of Figure 1 and Figure 2 show the differences between the vowel systems of northern and southern Italian. They were created by measuring the formant values of vowels produced by a representative sample of northern and southern Italian speakers. Data were collected through a guided interview consisting of target words in a frame sentence (see Ferrero, 1979; Romito, 2003).

Figure 1.

Dispersion area of the vowel system of northern Italian in Hz (adapted from Ferrero, 1979).

Figure 2.

Dispersion area of the vowel system of southern Italian in Hz (adapted from Romito, 2003).

3.3. Alveolar Affricates

In spoken Italian, the production of the affricate represented by the grapheme “z” has no fixed rules.

It is [] when it comes from a Latin voiceless sound, as in VITIU > vezzo (“mannerism”) [ˈveto], MARTIU > marzo (“march”) [ˈmaro], or CALCIA > calza (“sock”) [ˈkala]; it is voiced [] when it comes from a Latin voiced sound, as in HORDIU > orzo (“barley”) [ˈɔro], MEDIU > mezzo (“means”) [ˈmɛdo], or DUODICINA > dozzina (“dozen”) [dodˈdziːna], or when it comes from a Greek “z”, as in azoto (“nitrogen”) [adˈɔto] or zona (“zone”) [ˈɔna]. In the intervocalic context, the affricate can be both [] and []. These are always geminated, even when they are graphically represented as singletons (e.g., azoto (“nitrogen”) [adˈɔto], ozono (“ozone”) [odˈdzɔːno], or vezzo (“mannerism”) [ˈveto]). Voiceless and voiced pronunciations are variable across Italy, so it is plausible to find both [ˈprano] and [ˈprano] for “pranzo” (“lunch”, see Romito, 2023, p. 72).

3.4. Consonant Length and Vowel Duration

In the Italian phonological system, consonant duration has a distinctive function. Consider minimal pairs such as caro ̴ carro (“dear” and “car”, respectively) and fato ̴ fatto (“fate” and “made”, respectively), in which the meaning of the first element of the pair differs from that of the second due to consonant gemination. Almost all consonants can be both singletons and geminates except for /w/ and /j/. However, geminates do not constitute a homogeneous class of sounds. Many studies show different types of gemination in Italian: lexical (or contrastive), intrinsic, and post-lexical (Mairano & De Iacovo, 2019). A few are considered intrinsic geminates [ ʃ ʎ ɲ] because they are technically always produced as long sounds in intervocalic position, e.g., grazie /gratsje/ [grattsje] ‘thanks’. However, this is only partially true. If non-standard varieties of Italian are considered in the intervocalic context, they tend to be produced as long sounds in the central–southern area, while in the northern area they tend to be produced with a shorter duration. In general, the realisation of all geminates is less consistent in Northern Italian than in Central–Southern Italian (Bertinetto & Loporcaro, 2005). However, it has also been found that there are non-significant differences between northern and central-southern speakers, and this suggests that regional differences in Italian gemination have been overestimated in the literature (Mairano & De Iacovo, 2019, p. 612): northern speakers do not deviate from the articulatory characteristics of speakers from other Italian areas with respect to the consonant length (Celata & Kaeppeli, 2005). This could be due to the dialectal substrata of speakers who alternate regional Italian and the local dialect (Mairano & De Iacovo, 2019, pp. 629–630). Among the northern varieties of Italian, degemination of long consonants has been reported in Veneto Italian (see Vietti, 2019; Dian et al., 2024). Moreover, several studies have shown that geminates are approximately twice as long as singletons, and that the duration of the vowel preceding the geminate is shorter than the one preceding the singleton (Bertinetto, 1981; Esposito & Di Benedetto, 1999; Zmarich & Gili Fivela, 2005; Di Benedetto et al., 2021).

A related issue to the problem of consonant length concerns the preceding stressed vowels. Vowel durational variation is allophonic, and the speakers do not appear to be aware of it. However, some studies show that vowel shortening before a geminate is not consistently present to the same extent in all regional varieties of Italian (Table 1).

Table 1.

Vowel duration before geminates and singletons of the southern Italian varieties of Cosenza (CS), Catanzaro (CZ), Reggio Calabria (RC), Naples (NA), and of the northern variety of Padua (PD) in ms (adapted from Trumper & Romito, 1989). In the first column, the capital V stands for the stressed vowel preceding a singleton or a geminate consonant.

Table 1 and Table 2 show the differences in consonant duration between southern and northern Italian. In southern varieties, there is a longer stressed vowel before a singleton consonant (cVcv context) and a shorter one before a geminate (cVccv context). Conversely, in the northern variety of Padua (PD), the durational relationship between the two contexts is not so straightforward. In fact, Dian et al. (2024, p. 24) show that Veneto Italian speakers produce longer consonant durations and higher C/V ratios for all voiceless singletons, triggering some overlap between the consonant length categories, which results in partial degemination through singleton lengthening, although only for voiceless obstruents.

Table 2.

Consonant duration in the case of singletons and geminates as produced in the Italian of Catanzaro, in ms (adapted from Trumper & Romito, 1989).

3.5. Rhythm and Intonation

Rhythmic patterns of different languages are classified through variability in average consonant and vowel durations. Rhythm, as a linguistic phenomenon, must be framed among the different aspects of prosody. In the case of Italian, rhythmic and intonational variations can indicate different local varieties. Tarasi and Romito based their 2016 study on readings of sentences by native northern and southern Italian speakers, as well as by foreign speakers from Albania, Poland, China, and Romania. The first phase of the empirical study focused on perception, demonstrating that the most relevant parameter in the correct identification of L1 and L2 Italian speakers is the segmental level, but in combination with the prosodic level. The features used by the listeners to perceptually differentiate L1 and L2 Italian production were the presence/absence of phonosyntactic doubling (e.g., a casa [a (k)ka:sa] ‘at home’), the degemination of some consonants, and the production of some phones. However, important perceptual cues were also found at the prosodic level. This study revealed that 13.3% of listeners relied on rhythm and 34.33% on intonation.

Several studies (Gili Fivela et al., 2015; Sorianello, 2006) have investigated prosodic differences in regional Italian varieties, trying to provide an intonational representation of declarative, suspensive, and interrogative sentences in different regional varieties. Although some variation was probably due to the different methods of analysis, the data revealed that there are differences in intonation among regional varieties, especially in the question mode. Polar questions show rising pitch contours in central and northern varieties, while in the southern varieties, the final boundary tones are predominantly descending (De Dominicis, 2013, pp. 146–147; see also Frascarelli, 2004).

4. Textbooks for the Study of L2/FL Italian

Several linguists have pointed out an increasingly marked difference between standard Italian and the actual uses of the language according to contexts and speakers. As Diadori et al. (2015, p. 227) pointed out, for L2 Italian teachers, the main problem lies in avoiding the excessive separation between the language used in the classroom and the variety actually used in everyday communicative situations.

The teaching of a language as L2/FL has always been characterised by normative grammar that is far from the use of real speakers (Trifone, 2007, p. 177). Some studies reveal that textbooks for the teaching of L2/FL do include reference to the spoken language, besides the written norm (Bosc, 2005).

Although providing sometimes reflections on social, stylistic, and medium-related variations, textbooks tend to exclude any account of geographic variation. For example, regarding dialogues in formal (e.g., job interviews) or informal contexts (e.g., conversation between friends at the bar) or written texts (from business emails to messages on social networks) most of the times the exercises stimulate reflection on stylistic and medium-related variation only, disregarding how this variation can interact with the geographic characteristics of the speakers/writers.

Today, teaching methodologies should be oriented towards a communicative approach (Diadori et al., 2009, p. 164). Consequently, efforts have been made to understand which linguistic features, among those identified by Sabatini (1985) as typical of the contemporary Italian variety concretely used by the speakers (“italiano dell’uso medio” or neo-standard Italian), can be considered part of a new norm to be taught in L2/FL Italian.

Building on the analysis of Słapek (2016), Zingaro (2023) reviewed 32 L2 Italian textbooks published between 2018 and 2022 to evaluate which of the linguistic phenomena characterising the neo-standard are introduced. The study usefully shows that various neo-standard syntactic uses are included in some of the textbooks. However, the study by Zingaro (2023) does not deal with the teaching of pronunciation. Moreover, the interest is in stylistic and medium-related variants; regional variation is only cursorily addressed.

Although the new Common European Framework of Reference of Languages (CEFR) tackles phonetic competence more than in the past by adding new descriptors based on pronunciation features and paying more attention to the articulation of sounds and prosodic characteristics of speech (i.e., intonation, accent, and rhythm), L2/FL Italian textbooks do not delve much further into this aspect, as the short review discussed below will show.

5. A Critical Review

5.1. Textbook Sample

In this study, 32 textbooks were analysed from among those most widely used and known in the field of teaching L2/FL Italian to adult learners. These are the same textbooks already considered by Słapek (2016) and Zingaro (2023). The structure of L2/FL Italian textbooks is highly influenced by editorial choices. As a result, these texts are not divided into the proficiency levels provided by the CEFR: some overlap two or more levels into one, while others create intermediate levels. For this reason, it was necessary to carefully reconsider the actual CEFR levels with which they match, taking into account all of the sections in which the variables are introduced: grammar, listening, and sound production exercises.

In general, it can be noted that only a few pages of the textbooks are dedicated to the study of pronunciation, which is introduced at levels A1–A2. From A2 through to the following levels, the focus is mostly on morphosyntax. Only two texts introduce phonetic–phonological considerations up to the C2 level (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Titles and levels of the textbooks analysed, and levels at which pronunciation sections are introduced.

As widely discussed in Section 2, the pronunciation phenomena considered for this review were as follows:

- The voicing of intervocalic /s/.

- The vowel inventory.

- The voicing and length of the affricates /ts dz/.

- Vowel and consonant durations.

- Rhythm and intonation.

5.2. Results

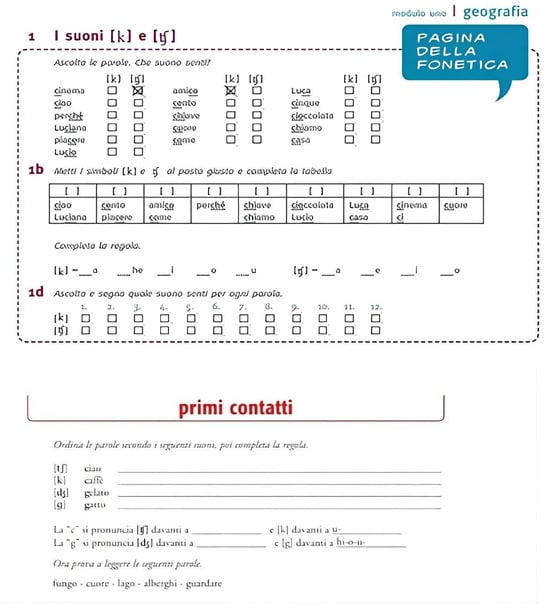

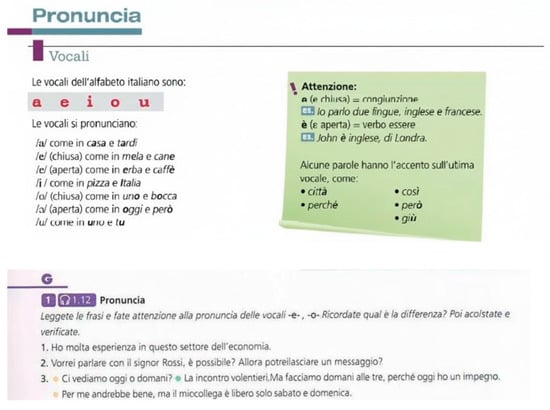

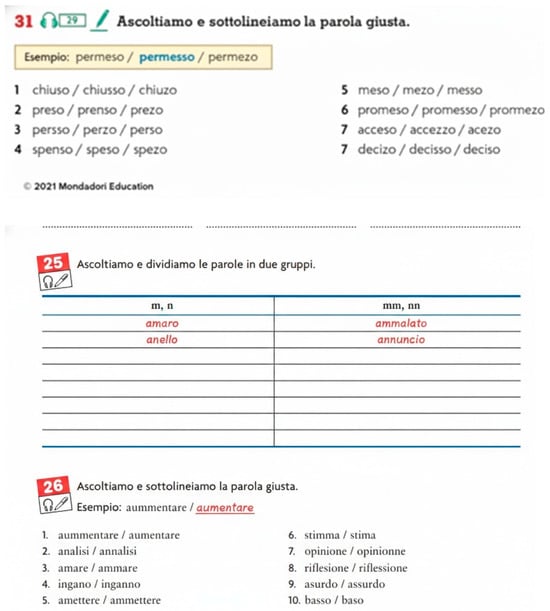

Most often, the exercises introduced in pronunciation sections ask students to listen to the sound and repeat it or to listen to the sound and underline the corresponding grapheme. Furthermore, after introducing these exercises, some textbooks ask students to implement and practise orthographic–phonetic correspondence rules (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Examples of phonetic exercises from Domani and Nuovo espresso, respectively.

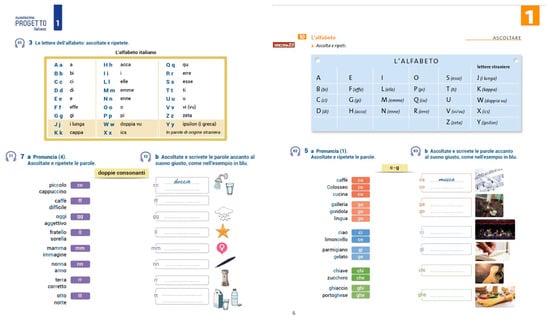

Figure 4 shows that textbooks introduce pronunciation topics starting from orthographic conventions and give greater emphasis to some phonemes presented as minimal pairs: /k/ ̴ /ʧ/, /ɡ/ ̴ /ʤ/, /ku/ ̴ /kw/, /ʎ/, /ɲ/, and /ʃ/.

Figure 4.

Examples of listening and production exercises from Nuovissimo progetto italiano and Chiaro.

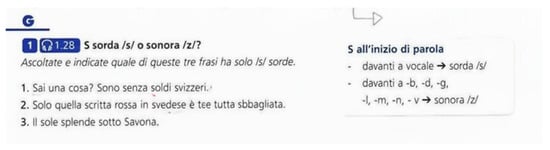

The phonotactic distribution of voiceless and voiced /s/ is discussed in seven of the textbooks; an example is provided in Figure 5. Although the voicing of /s/ in intervocalic position is one of the features of neo-standard Italian (see Sabatini, 1985), most of the textbooks do not mention it. Figure 5 shows that, even when /s/ voicing is discussed, the proposed pronunciation rule does not adequately represent the ongoing generalisation of voiced /z/ intervocalically.

Figure 5.

Exercise and explanation of the voicing of intervocalic /s/ adapted from Caffè Italia.

All of the texts in our corpus introduce a five-vowel system, except two of them which introduce a seven-vowel system (see Figure 6): the distinction between mid-close /e/ and mid-open /ɛ/ is presented as distinctive, differentiating between “è” as the third person of the present simple tense of the verb “to be” and “e” as a conjunction.

Figure 6.

Examples of phonetic explanation of front mid-vowel distinction from Nuovo contatto and Caffè Italia.

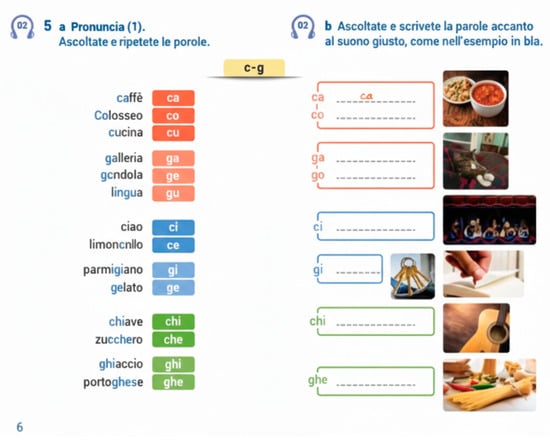

In 24 of the 32 textbooks, the affricates /ts/ and /dz/ are not introduced in minimal pairs, but the voiced realisation is more widespread than the voiceless one. The voiceless and voiced alveopalatal affricates /ʧ ʤ/ are introduced in minimal pairs with the voiceless and voiced velar stops (/k ɡ/), as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Exercises on affricate sounds in minimal pairs with stops from Nuovissimo progetto italiano.

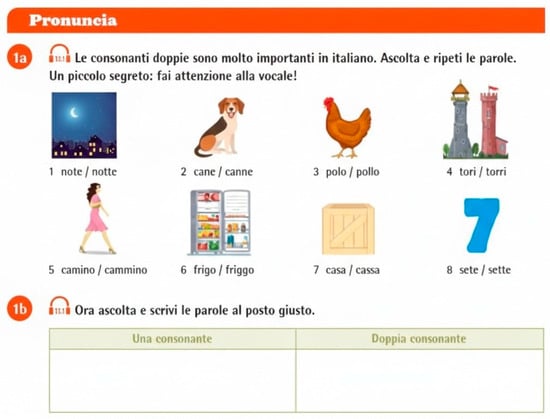

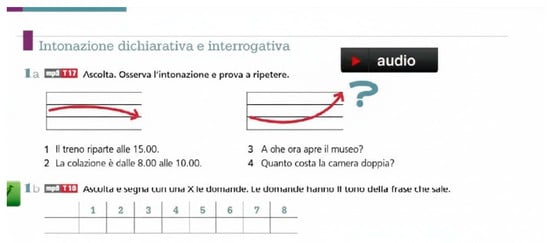

In 29 of the 32 texts, consonant duration is widely discussed; these textbooks propose listening exercises in which the students are asked to recognise whether certain sounds are singletons or geminates, sometimes also focusing their attention on the preceding vowel duration (see Figure 8 and Figure 9).

Figure 8.

Exercises on geminates and vowel duration adapted from Nuovo affresco italiano.

Figure 9.

Exercises on geminates and vowel duration adapted from Nuovo affresco italiano.

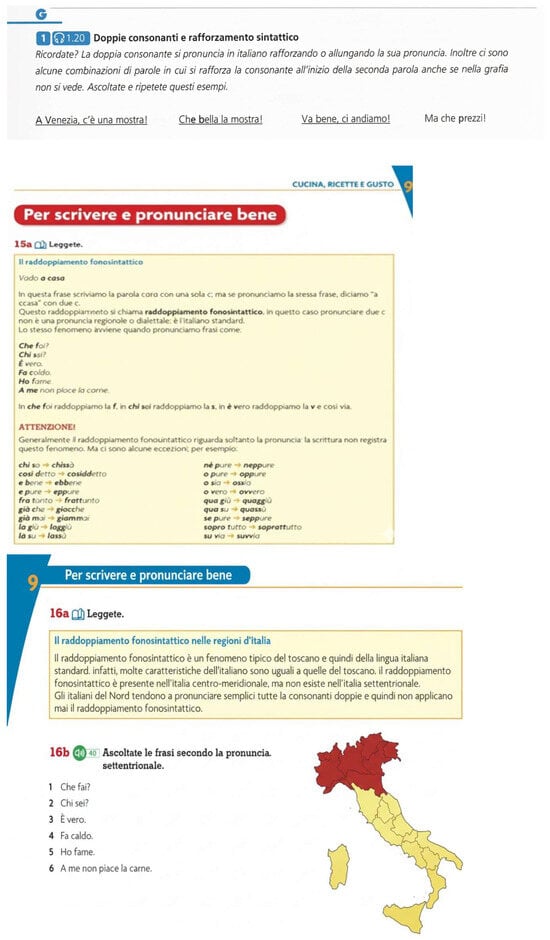

When the textbooks introduce regional varieties of Italian, they almost exclusively refer to phonosyntactic doubling, as shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Exercise and explanation of phonosyntactic doubling from Caffè Italia and Nuovo affresco italiano.

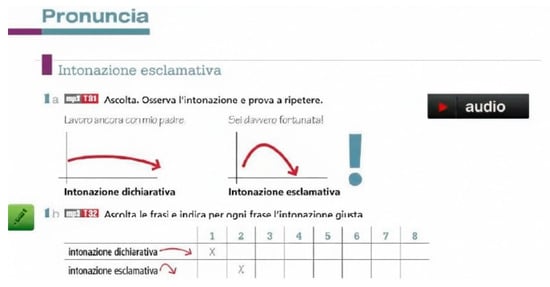

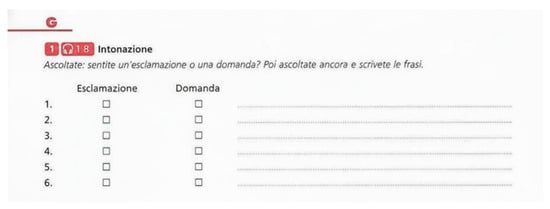

Conversely, as far as rhythm and intonation are concerned, the data show that only 6 of the 32 textbooks feature an intonation section. However, as shown in Figure 11, Figure 12 and Figure 13, they focus on the different intonation patterns that characterise declarative, interrogative, and exclamative sentences, with no reference to geographic variation.

Figure 11.

Different intonation in declarative and exclamative forms in Nuovo contatto.

Figure 12.

Different intonation in declarative and interrogative forms in Nuovo contatto.

Figure 13.

Exercise on intonation discrimination from Caffè Italia.

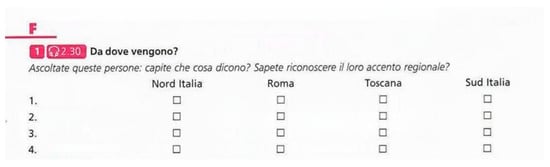

In their sporadic mention of geographic variability, textbooks may ask the students to recognise the regional accent after listening to excerpts of natural conversation, as shown in Figure 14.

Figure 14.

Exercise on regional accents from Caffè Italia.

Table 4 summarises how the variables considered are distributed across the textbooks analysed in this study.

Table 4.

Number of textbooks in which the phonetic–phonological variables analysed are reported.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

Among all of the texts analysed, two lack any reference to phonetics. Overall, the general tendency appears to be a gradual adaptation to the new European Framework, including parts dedicated to the study of phonetics and some features of the neo-standard. Nevertheless, this remains insufficient. In fact, if the vowel system, gemination, and alveolar affricates are often discussed, the same cannot be stated for the voicing of intervocalic /s/ and for rhythm and intonation, for which exercises are found in only 21.8% and 18.75% of the analysed textbooks, respectively. As far as rhythm and intonation are concerned, the accompanying audio recorded for the analysed textbooks is not always regionally characterised; it is functional in introducing regional varieties in C1–C2-level textbooks. This work aimed to demonstrate how the teaching of Italian as an L2/FL is controversial in its intersections with the open question of a linguistic “standard” Italian. Such a standard has been coded by the grammar of the written variety, which has held up since the Unification of Italy (1861). Therefore, teachers of Italian as a second/foreign language have to cope with the inconsistency between the language of textbooks and the language that learners encounter in various daily communicative situations. On the one hand, a language that tends towards the neo-standard is presented; on the other, learners will find that phonetic varieties of the language are strongly subject to regional variation, but this aspect is almost totally absent from teaching practices.

We want to stress that it would be extremely useful to further explore geolinguistic variation, in addition to medium-related and social class-related variations. As we have discussed, every teacher will use their own regional variety of Italian, and this is already enough for the learners to experience phonetic variation in their real life.

As a final comment, we want to recall that there is no standard education for Italian L2/FL teachers. Among the master’s degrees recognised by the Italian Ministry of Education as qualifications for teaching L2/FL Italian in DM n.92/2016 and in DM n.130/2023, only one explicitly refers to the teaching of the “phonetics and phonology of Italian in a contrastive perspective”. We hope that this contribution has stressed further the importance of adopting a perspective open to the regional variability of pronunciation phenomena in teaching Italian as a second/foreign language, based on the recognised observation that a standard norm in the realisation of many segmental and supra-segmental aspects does not actually exist.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, L.R. and E.G.; methodology, E.G.; validation, L.R. and E.G.; formal analysis, E.G.; data curation, E.G.; writing—original draft preparation, L.R. and E.G.; writing—review and editing, E.G.; supervision, L.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analysed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | In the 2001 CEFR there was already a reference to phonetic level and intonation. In the 2018 revision, the phonetic–phonological aspect has been expanded and better organised. |

| 2 | Contrastive phonology is used only in academic teaching. See (De Dominicis, 2013; Romito, 2023). |

| 3 | In the academic field, there are some methods such as the verbotonal method (Guberina, 2013) or the articulatory approach (Underhill, 2005; Messum, 2012; Young, 2012) to teach pronunciation, but only in rare cases are these applied in schools for the teaching of L2 or FL. |

| 4 | According to Ammon (1986, 2003), among the characteristics that identify a standard language, it is codified, supraregional, elaborated, used by upper classes, invariant, and written. |

| 5 | The 14th-century written language is based on the works of Dante, Petrarch, and Boccaccio. |

| 6 | Today, in Italy, an active restandardisation process of Italian can be noticed in the northern part of the country. |

| 7 | According to Salvi and Renzi (2010, pp. 713–715), it is not easy to periodise the Italian language (in contrast to French, German, and English). The authors propose three different historical periods identified in old Italian or old Florentine from 1211 to the 1400s, Middle Florentine from the beginning of the 1400s until the reform of Pietro Bembo in 1525, and modern Italian from the reforms of Bembo and Manzoni to the present day. Therefore, according to the authors, modern Italian would be a direct consequence of old Italian, whereas Middle Italian developed in the Florentine dialect (see Manni, 1979). |

| 8 | By spreading elementary education and the reading of sacred texts, the Protestant Reformation was important for all social classes in all regions of the German state on identical religious themes. |

| 9 | In 1923, Italianisation spread Italian culture, language, and identity. In the Royal Decree of 1 October 1923 (n. 2185, art. 4), it is written that teaching is given in the official language of the state in all the elementary schools of the kingdom. In municipalities where a different language is habitually spoken, this will be studied in additional hours. In other decrees, it is written not to publish articles, poems, or titles in dialects. Vernacular literature is not encouraged. |

| 10 | De Mauro (2017) recognises the northern variety, the Tuscan variety, the Roman variety, and the southern variety, each of which has some subvarieties. See also (Sobrero, 1988, pp. 732–733). |

| 11 | The term southern is very generic: for example, the Italian spoken in the city of Naples is characterised by a seven-vowel system. For more information, see (Romito, 2023). |

References

- Ammon, U. (1986). Explikation der begriffe ‘Standardvarietät’ und ‘Standardsprache’ auf normtheoretischer grundlage. In V. G. Holtus, & E. Radtke (Eds.), Sprach-licher substandard (Vol. 1, pp. 1–62). Niemeyer. [Google Scholar]

- Ammon, U. (2003). On the social forces that determine what is standard in a language and on conditions of successful implementation. Sociolinguistica, 17, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascoli, G. I. (1880). L’Italia dialettale. Archivio Glottologico Italiano, 8, 98–128. [Google Scholar]

- Balboni, P. E. (2008). Fare educazione linguistica. Attività didattiche per l’italiano L1 e L2, lingue straniere e lingue classiche. UTET UNIVERSITÀ. [Google Scholar]

- Berruto, G. (2012). Sociolinguistica dell’italiano contemporaneo. La Nuova Italia Scientifica. [Google Scholar]

- Berruto, G. (2017a). Dinamiche nell’architettura delle varietà dell’italiano nel ventunesimo secolo. In G. Caprara, & M. Giorgia (Eds.), Italiano e dintorni. La realtà linguistica italiana: Approfondimenti di didattica, variazione e traduzione (pp. 7–31). Peter Lang Edition. [Google Scholar]

- Berruto, G. (2017b). What is changing in Italian today. In C. Massimo, C. Crocco, & S. Marzo (Eds.), Towards a new standard: Theoretical and empirical studies on the restandardization of Italian (pp. 31–60). Mouton de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Bertinetto, P. M. (1981). Strutture prosodiche dell’Italiano (Studi di grammatica italiana). Accademia della Crusca. [Google Scholar]

- Bertinetto, P. M., & Loporcaro, M. (2005). The sound pattern of standard Italian, as compared with the varieties spoken in Florence, Milan and Rome. Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 35(2), 131–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosc, F. (2005). Quale italiano per vivere in Italia? La lingua per comunicare. In B. Iori (Ed.), L’italiano e le altre lingue. Apprendimento della seconda lingua e bilinguismo dei bambini e dei ragazzi immigrati (pp. 79–87). FrancoAngeli. [Google Scholar]

- Camilli, A. (1965). Pronuncia e grafia nell’italiano. Sansoni—Biblioteca di Lingua Nostra. [Google Scholar]

- CEFR. (2018). Common european framework of reference for languages. Council of Europe Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Celata, C., & Kaeppeli, B. (2005). Affricazione e rafforzamento in italiano: Alcuni dati sperimentali. Quaderni del Laboratorio di Linguistica, 4, 43–59. [Google Scholar]

- Cerruti, M. (2018). Il parlato regionale oggi: Un italiano composito? LId’O Lingua Italiana d’oggi, 15, 15–31. [Google Scholar]

- Cerruti, M., Crocco, C., & Marzo, S. (2017). On the development of a new standard norm in Italian. In C. Massimo, C. Claudia, & M. Stefania (Eds.), Towards a new standard: Theoretical and empirical studies on the restandardization of Italian (pp. 3–28). De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Cortelazzo, M. A. (2001). L’italiano e le sue varietà: Una situazione in movimento. Lingua e Stile, 36, 417–430. [Google Scholar]

- Crocco, C. (2017). Everyone has an accent: Standard Italian and regional pronunciation. In C. Massimo, C. Claudia, & M. Stefania (Eds.), Towards a new standard. Theoretical and empirical studies on the restandardization of Italian (pp. 89–116). De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- D’Achille, P. (2006). L’italiano contemporaneo. Il Mulino. [Google Scholar]

- De Dominicis, A. (2013). Fonologie comparate. Suoni e lingue d’Europa, cina e mondo arabo. Carocci. [Google Scholar]

- De Mauro, T. (2017). Storia linguistica d’Italia dall’Unità ad oggi. Laterza. [Google Scholar]

- De Pascale, S., Marzo, S., & Speelman, D. (2017). Evaluating regional variation in Italian: Towards a change in standard language ideology? In C. Massimo, C. Claudia, & M. Stefania (Eds.), Towards a new standard. Theoretical and empirical studies on the restandardization of Italian (pp. 118–141). De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Diadori, P., Palermo, M., & Troncarelli, D. (2009). Manuale di didattica dell’italiano L2. Guerra Edizioni. [Google Scholar]

- Diadori, P., Palermo, M., & Troncarelli, D. (2015). Insegnare italiano come seconda lingua. Carocci Editore. [Google Scholar]

- Dian, A., Hajek, J., & Fletcher, J. (2024). Cross-regional patterns of obstruent voicing and gemination: The case of Roman and Veneto Italian. Languages, 9(12), 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Benedetto, M. G., Shattuck-Hufnagel, S., De Nardis, L., Budoni, S., Arango, J., Chan, I., & De Caprio, A. (2021). Lexical and syntactic gemination in Italian consonants—Does a geminate Italian consonant consist of a repeated or a strengthened consonant? The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 149, 3375–3386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esposito, A., & Di Benedetto, M. G. (1999). Acoustical and perceptual study of gemination in Italian stops. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 106(4), 2051–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrero, G. (1979). L’identificazione della persona per mezzo della voce. ESA. [Google Scholar]

- Frascarelli, M. (2004). L’interpretazione del focus e la portata degli operatori sintattici [The interpretation of focus and the scope of syntactic operators]. In F. Albano Leoni, F. Cutugno, M. Pettorino, & R. Savy (Eds.), Il Parlato Italiano: Atti del convegno nazionale (Naples, 13–15 febbraio 2003) (CD-ROM B06). M. D’Auria Editore—CIRASS. [Google Scholar]

- Galli de’ Paratesi, N. (1977). La standardizzazione della pronuncia nell’italiano contemporaneo. Aspetti sociolinguistici dell’Italia contemporanea. In R. Simone, & G. Ruggiero (Eds.), Atti dell’VIII congresso internazionale di studi, Bressanone, Italy, May 31–June 2 (pp. 167–196). Bulzoni. [Google Scholar]

- Galli de’ Paratesi, N. (1984). Lingua toscana in bocca ambrosiana. Il Mulino. [Google Scholar]

- Gili Fivela, B., Avesani, C., Barone, M., Bocci, G., Crocco, C., D’Imperio, M., Giordano, R., Marotta, G., Savino, M., & Sorianello, P. (2015). Intonational phonology of the regional varieties of Italian. In S. Frota, & P. Prieto (Eds.), Intonation in romance (pp. 140–197). Oxford Univesity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Guberina, P. (2013). The verbotonal method (C. Roberge, Ed.). ARTRESOR NAKLADA. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzetti, L. (2006). L’italiano contemporaneo. Carocci. [Google Scholar]

- Mairano, P., & De Iacovo, V. (2019). Gemination in northern versus central and southern varieties of Italian: A corpus-based investigation. Language and Speech, 63(3), 608–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manni, P. (1979). Ricerche sui tratti fonetici e morfologici del fiorentino quattrocentesco. Studi di Grammatica Italiana, 8, 115–171. [Google Scholar]

- Messum, P. (2012). Teaching pronunciation without using imitation: Why and how. In J. Levis, & K. LeVelle (Eds.), Proceedings of the 3rd pronunciation in second language learning and teaching conference, Ames, IA, USA, September 16–17 (pp. 154–160). Iowa State University. [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrini, G. B. (1975). Saggi di linguistica italiana: Storia, struttura, società. Boringhieri. [Google Scholar]

- Pizzoli, L. (2004). Le grammatiche di italiano per inglesi (1550–1776). Un’analisi linguistica. Accademia della Crusca. [Google Scholar]

- Romito, L. (2003). Manuale di fonetica articolatoria, acustica e forense. Centro Editoriale e Libraio Università della Calabria. [Google Scholar]

- Romito, L. (2023). I suoni delle lingue. Manuale di fono-didattica. Italiano, spagnolo, francese, inglese e tedesco. AMON Edizioni. [Google Scholar]

- Sabatini, F. (1985). ‘L’italiano dell’uso medio’: Una realtà tra le varietà linguistiche italiane. In V. G. Holtus, & E. Radtke (Eds.), Gesprochenes Italienisch in geschichte und gegenwart (pp. 154–184). Narr. [Google Scholar]

- Salvi, G., & Renzi, L. (Eds.). (2010). Grammatica dell’italiano antico. Il Mulino. [Google Scholar]

- Słapek, D. (2016). Argomenti grammaticali e nei certificati d’italiano LS. Rivista Italiana di Linguistica Applicata (RILA), 49(1), 109–127. [Google Scholar]

- Sobrero, A. A. (1988). Italianisch: Regionale varianten/italiano regionale. In G. Holtus, M. Metzelin, & C. Schmitt (Eds.), Lexikon der Romanistishen Linguistik (LRL) (Vol. 4, pp. 732–748). Niemayer. [Google Scholar]

- Sorianello, P. (2006). Prosodia. Modelli e ricerca empirica, con CD-Rom multimediale. Carocci Editore. [Google Scholar]

- Trifone, P. (2007). Malalingua: L’italiano scorretto da Dante a oggi. Il Mulino. [Google Scholar]

- Trumper, J., & Romito, L. (1989). Un problema della coarticolazione: L’isocronia rivisitata. In Atti del XVII convegno nazionale dell’associazione Italiana di acustica (pp. 449–456). Tipolitografia Mattioli. [Google Scholar]

- Trumper, J., Romito, L., & Maddalon, M. (1991). Vowel systems and areas compared: Definitional problems. In P. Benincasa (Ed.), L’interfaccia tra fonologia e fonetica (Vol. 1, pp. 43–72). Unipress. [Google Scholar]

- Underhill, A. (2005). Sounds foundations. Learning and teaching pronunciation. Macmillan Education. [Google Scholar]

- Vietti, A. (2019). Phonological variation and change in Italian. In Oxford research encyclopedia of linguistics. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, R. (2012). Teaching pronunciation efficiently means not using ‘Listen and Repeat’. In Teaching times (Vol. 63, p. 18). TESOL. [Google Scholar]

- Zingaro, A. (2023). Quale italiano? Una proposta per l’insegnamento dell’italiano a stranieri tra standard e neostandard. University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zmarich, C., & Gili Fivela, B. (2005). Consonanti scempie e geminate in italiano: Studio cinematico e percettivo dell’articolazione bilabiale e labiodentale. In P. Cosi (Ed.), Misura dei parametri, Atti del I convegno nazionale dell’associazione Italiana di scienze della voce, Padova, Italy, Decemeber 2–4 (pp. 429–448). EDK Editore. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.