The Development of Children’s Request Strategies in L1 Greek

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Empirical and Theoretical Background of the Study

2.1. The Development of Directive Repertoire in Children

2.2. Conceptual Framework: Illocutionary Constructions

- How does the development of requestive behaviour manifest in terms of the range and types of request constructions used by preschool- and school-aged children across different communicative situations?

- How are children’s request constructions related to their sociocognitive development, specifically their ability to take into account the social parameters of an interaction when making requests?

3. Methods

3.1. Participants

3.2. Instrument and Procedure

3.3. Coding Scheme

3.4. Statistical Analysis

4. Results

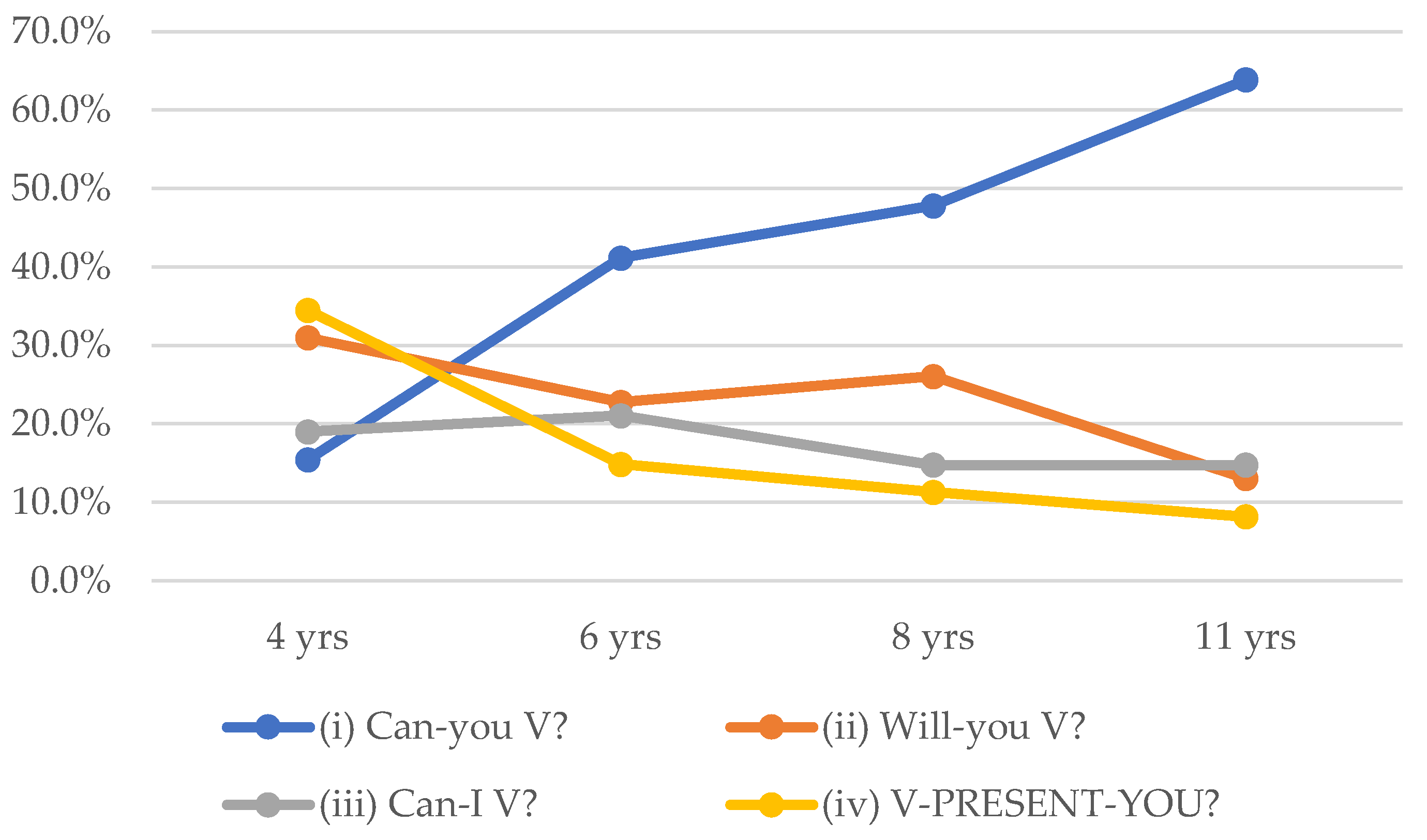

4.1. Linguistic Resources Used in Request-Making

- (a)

- λίγο (“a little/bit”), used as a hedge (Canakis, 2015), e.g., Μπορείς να μου δώσεις λίγο το ποδήλατό σου; (“Can you give me your bike for a bit?”; Bike scenario);

- (b)

- diminutives, such as σκυλάκι (“doggie”) in the utterance Μπορείς να μου δώσεις λίγο το σκυλάκι σου να παίξω; (“Can you give me your doggie to play with for a bit?” or “Can you let me play with your doggie for a bit?”; Dog scenario);

- (c)

- V-forms (“politeness plural”), a classic politeness strategy in Greek (as well as in many other languages) that elevates both the formality and social consideration of the request, as in the utterance … μπορείτε να μας φέρετε την μπάλα; (“… can you-PLURAL bring-PLURAL us the ball?”; Ball scenario).

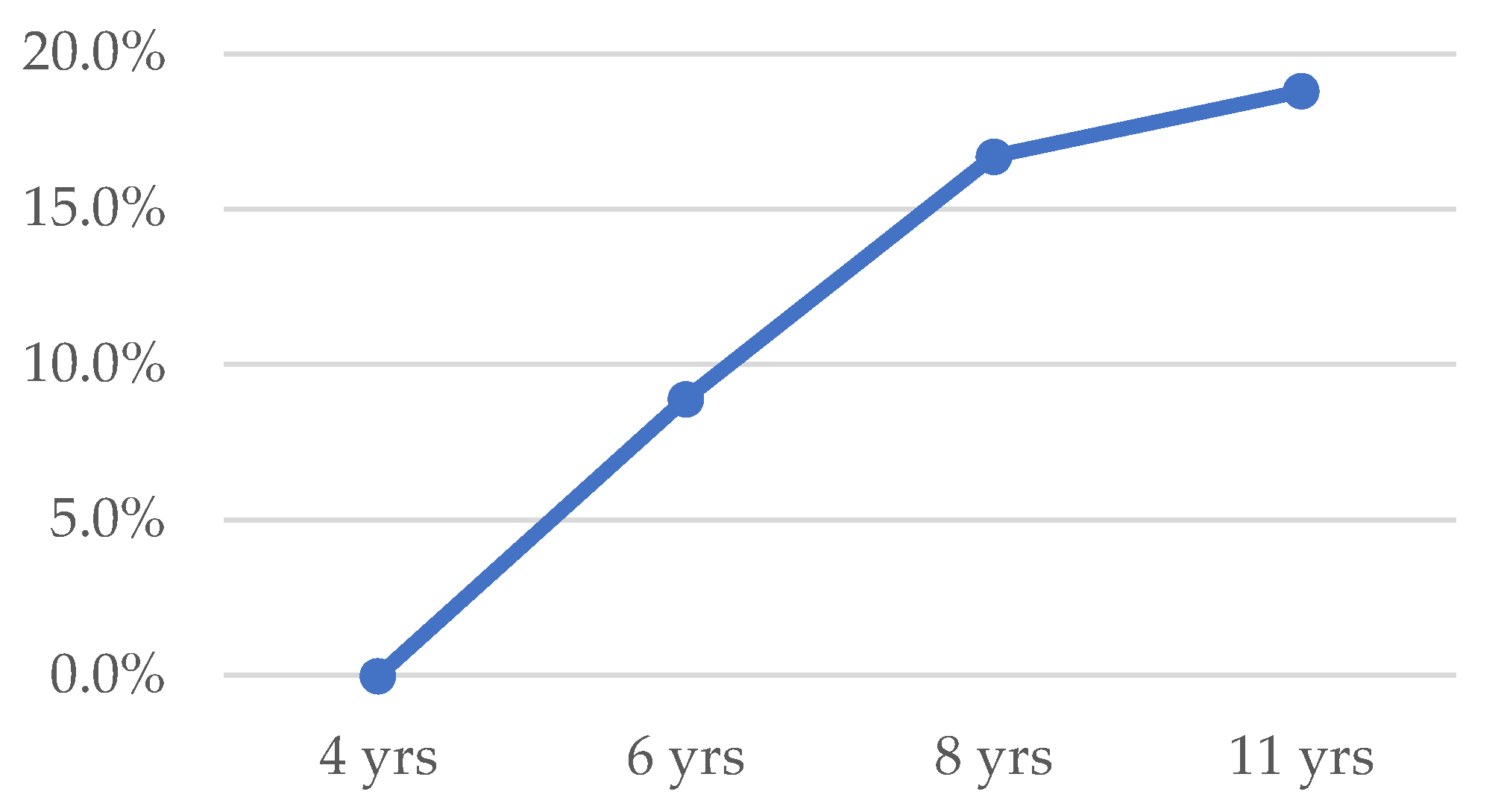

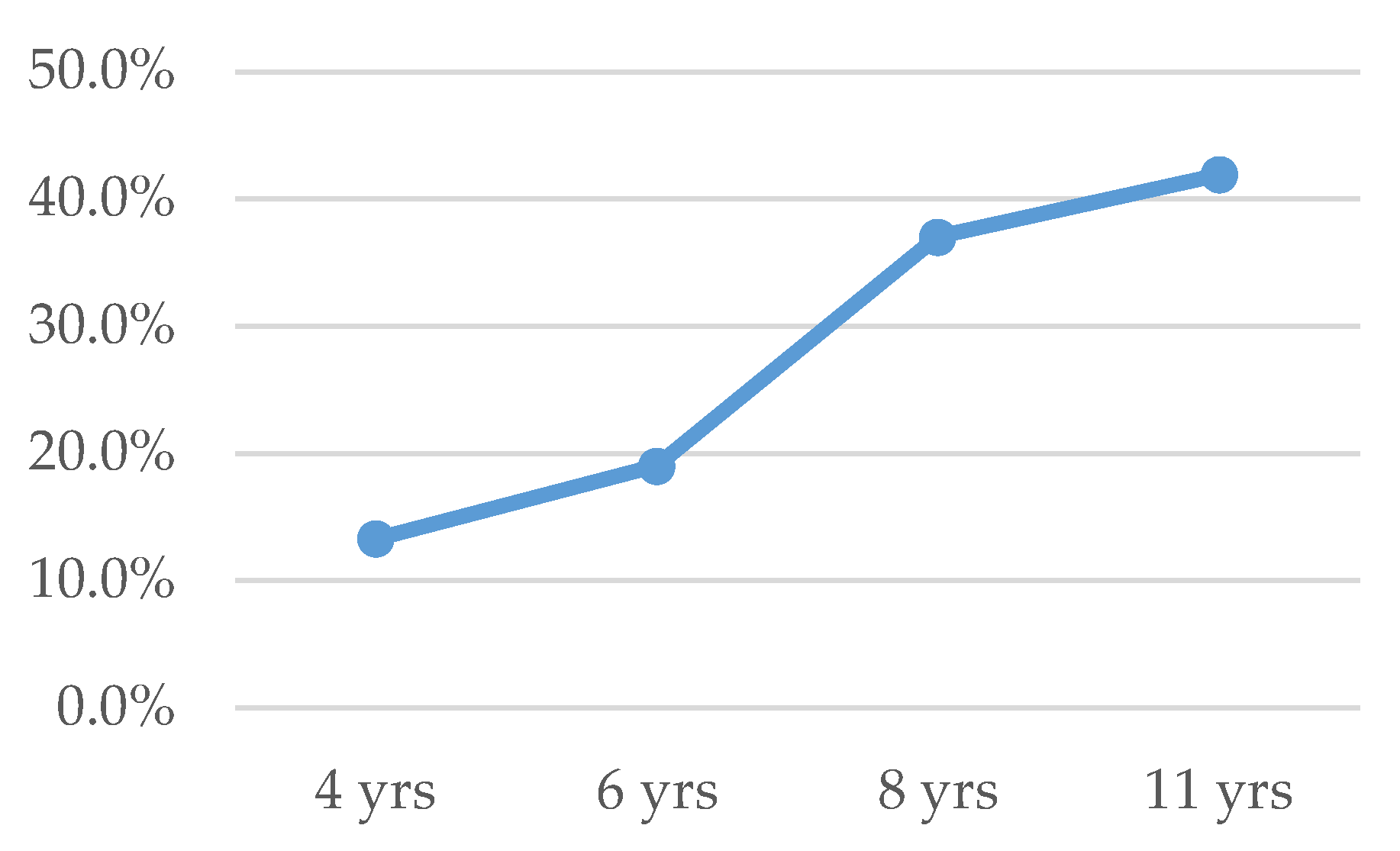

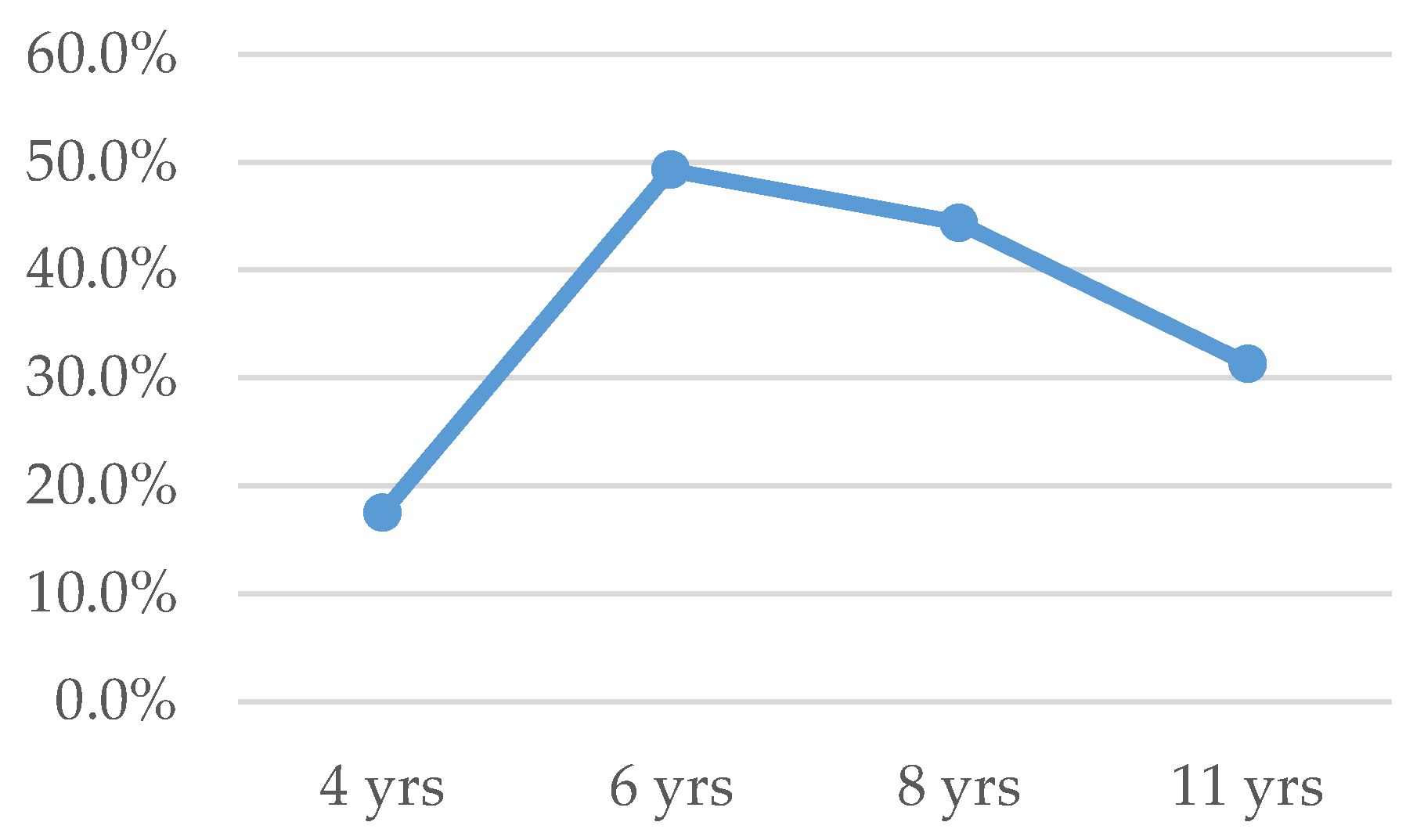

4.2. Indices of Children’s Increasingly Consolidated Sensitivity to Social Factors

5. Discussion

5.1. Key Findings and Theoretical Contributions

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| High Cost | ||

| Familiarity + | Familiarity − | |

| Power + | Your dad has just come back from work and he is very tired. You want him to drive you to a friend’s home who invited you to play together. What do you say exactly to your dad? (Father Tired scenario) | You play football with your friends in a playground. The ball goes out of the fence, rolling fast down the street. At that moment a lady passes by. You ask her to go and get the ball. What do you say exactly? (Ball scenario) |

| Power − | Your friend has an amazing puzzle. His godmother bought it for him from America and he is very excited. You don’t have any puzzles and ask him to give it to you as a gift. What do you say exactly? (Puzzle scenario) | In the square, you come across a kid riding his/her new bike. This kid is not someone you know. You left your bike at home. You ask that kid to let you ride the bike for a while. What do you say exactly? (Bike scenario) |

| Low Cost | ||

| Familiarity + | Familiarity − | |

| Power + | Your grandmother and you go for a walk and pass by a kiosk. You are thirsty and ask her to buy you some juice. What do you say exactly? (Juice scenario)– | As you play in the square, you see a lady walking her dog. You want to play with the dog for a while, because you like animals very much. What do you say exactly to the lady? (Dog scenario) |

| Power − | Your friend at school has a big pack of cookies and eats some during playtime. You ask for a cookie. What do you say exactly? (Cookie Familiar scenario) | During playtime at school a kid who is not a classmate and a friend of yours (you don’t know his/her name) eats your favourite cookies. He/She has an almost full pack and you ask for a cookie. What do you say exactly to that kid? (Cookie Unfamiliar scenario) |

Appendix B

| Category | Codes | Example 1 | Example 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Μου δίνεις, σε παρακαλώ πολύ, ένα μπισκότο; (lit.: “Are You Giving Me, Please, a Cookie?”/”Could You Please Give Me a Cookie?”) | Θα μπορούσες να μου δανείσεις το ποδήλατό σου και εγώ θα σου το επιστρέψω; (“Could You Lend Me Your Bike, and I’ll Give It Back to You?”) | ||

| Sentence Type/Μood | Imperative | 0 | 0 |

| Interrogative | 1 | 1 | |

| Subjunctive | 0 | 0 | |

| Tense | Present | 1 | 0 |

| Future | 0 | 0 | |

| Past (+ θα) (=would) | 0 | 1 | |

| (Modal) | Want (θέλω) | 0 | 0 |

| Can/May (μπορώ) | 0 | 1 | |

| Main Verb Inflectional Marking | Person (1st vs. 2nd) | 0 | 0 |

| Number (Singular vs. Plural) | 1 | 1 | |

| Optional Elements | Please (παρακαλώ) | 1 | 0 |

| A bit (λίγο) | 0 | 0 | |

| Diminutives | 0 | 0 | |

| Summons | 0 | 0 | |

| Supportive Moves | 0 | 1 |

References

- Ainsworth-Vaughn, N. (1990). The acquisition of sociolinguistic norms: Style-switching in very early directives. Language Sciences, 12, 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Abbas, L. (2023). Politeness strategies used by children in requests in relation to age and gender: A case study of Jordanian elementary school students. Frontiers in Education, 8, 1175599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andini, S., Sudarto, S., Ayatullah, A., & Farhan, H. M. (2025). Language politeness in Javanese and Sundanese border cultural landscapes in elementary school student learning. Journal of Innovation in Educational and Cultural Research, 6(4), 681–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axia, G., & Baroni, M. R. (1985). Linguistic politeness at different age levels. Child Development, 56, 918–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baicchi, A. (2017). How to do things with metonymy in discourse. In A. Athanasiadou (Ed.), Studies in figurative thought and language (pp. 75–104). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Bates, E. (1976). Language and contexts: The acquisition of pragmatics. Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bernicot, J., & Legros, S. (1987). Direct and indirect directives: What do young children understand? Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 43, 346–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum-Kulka, S., House, J., & Kasper, G. (Eds.). (1989). Cross-cultural pragmatics: Requests and apologies. Ablex. [Google Scholar]

- Bock, J. K., & Hornsby, M. E. (1981). The development of directives: How children ask and tell. Journal of Child Language, 8(1), 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, P., & Levinson, S. (1987). Politeness: Some universals in language usage. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant, J. B. (2015). Pragmatic development. In E. L. Bavin, & L. R. Naigles (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of child language (pp. 438–457). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron-Faulkner, T. (2014). The development of speech acts. In D. Matthews (Ed.), Pragmatic development in first language acquisition (pp. 37–52). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Canakis, C. (2015). Non-quantifying líγo constructions in Modern Greek. Constructions and Frames, 7(1), 47–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. (2017). Children’s early awareness of the effect of interpersonal status on politeness. Journal of Politeness Research, 13(1), 121–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dąbrowska, E. (2004). Rules or schemas? Evidence from Polish. Language and Cognitive Processes, 19, 225–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desagulier, G., & Monneret, P. (2023). Cognitive Linguistics and a usage-based approach to the study of semantics and pragmatics. In M. Díaz-Campos, & S. Balasch (Eds.), The handbook of usage-based linguistics, 1. Wiley. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diessel, H. (2013). Construction grammar and first language acquisition. In T. Hoffmann, & G. Trousdale (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of construction grammar (pp. 347–364). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dore, J. (1977). Children’s illocutionary acts. In R. O. Freedle (Ed.), Discourse production and comprehension (pp. 227–244). Ablex. [Google Scholar]

- Drew, P., & Couper-Kuhlen, E. (2014). Requesting—From speech act to recruitment. In P. Drew, & E. Couper-Kuhler (Eds.), Requesting in social interaction (pp. 1–34). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Economidou-Kogetsidis, M., Myrset, A., & Savić, M. (2026). “If we are talking to the Minster of Education …”: L2 request appraisals and metapragmatic awareness in young learners of English. In G. Schauer, M. Economidou-Kogetsidis, M. Savić, & A. Myrset (Eds.), Second language pragmatics and young language learners: EFL primary school contexts in Europe (pp. 23–53). Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Ervin-Tripp, S., Guo, J., & Lampert, M. (1990). Politeness and persuasion in children’s control acts. Journal of Pragmatics, 14, 307–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ervin-Tripp, S. Μ. (1977). Wait for me, roller skate! In S. Ervin-Tripp, & C. Mitchell-Kernan (Eds.), Child discourse (pp. 165–188). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ervin-Tripp, S. M. (2009). Developmental psychology. In D. Sandra, J.-O. Östman, & J. Verschueren (Eds.), Cognition and pragmatics (pp. 146–156). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Ervin-Tripp, S. M., & Gordon, D. P. (1986). The development of children’s requests. In R. E. Schiefelbusch (Ed.), Communicative competence: Assessment and intervention (pp. 61–96). College Hill Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fried, M., & Nikiforidou, K. (2025). Construction grammar: Introduction. In M. Fried, & K. Nikiforidou (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of construction grammar (pp. 1–20). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gass, S. M., & Houck, N. (1999). Interlanguage refusals: A cross-cultural study of Japanese-English. De Gruyter Mouton. [Google Scholar]

- Georgalidou, M. (2008). The contextual parameters of linguistic choice: Greek children’s preferences for the formation of directive speech acts. Journal of Pragmatics, 40, 72–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, D. P., & Ervin-Tripp, S. M. (1984). The structure of children’s requests. In R. E. Schiefelbusch, & A. Pickar (Eds.), The acquisition of communicative competence (pp. 295–321). University Park Press. [Google Scholar]

- Grosse, G., Moll, H., & Tomasello, M. (2010). 21-Month-olds understand the cooperative logic of requests. Journal of Pragmatics, 42, 3377–3383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, A. M. (2012). Problem solving, reasoning and numeracy in the early years foundation stage. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Huls, E., & van Wijk, C. (2012). The development of a directive repertoire in context: A case study of a Dutch speaking young child. Journal of Pragmatics, 44(1), 83–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kania, U. (2013). “Can I ask you something?”: The influence of functional factors on the L1-acquisition of yes-no questions in English. Yearbook of the German Cognitive Linguistics Association, 1(1), 109–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kania, U. (2016). Why don’t you just learn it from the input?: A usage-based corpus study on the acquisition of conventionalized indirect speech acts in English and German. In L. Ortega, A. E. Tyler, H. I. Park, & M. Uno (Eds.), The usage-based study of language learning and multilingualism (pp. 37–53). Georgetown University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kasper, G. (2000). Data collection in pragmatics research. In H. Spencer-Oatey (Ed.), Culturally speaking (pp. 316–341). Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Küntay, A., Nakamura, K., & Ateş, B. S. (2014). Crosslinguistic and crosscultural approaches to pragmatic development. In D. Matthews (Ed.), Pragmatic development in first language acquisition (pp. 317–341). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Laalo, K. (2021). Directives in Finnish language acquisition. In U. Stephany, & A. Aksu-Koç (Eds.), Development of modality in first language acquisition: A cross-linguistic perspective (pp. 347–378). De Gruyter Mouton. [Google Scholar]

- Leech, G. (1983). Principles of pragmatics. Longman. [Google Scholar]

- Liebling, C. R. (1988). Means to an end: Children’s knowledge of directives during the elementary school years. Discourse Processes, 11(1), 79–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieven, E., & Tomasello, M. (2008). Children’s first language acquistion from a usage-based perspective. In P. Robinson, & N. C. Ellis (Eds.), Handbook of cognitive linguistics and second language acquisition (pp. 168–196). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- Marmaridou, S. (2000). Pragmatic meaning and cognition. John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, D. (2014). Introduction. An overview of research on pragmatic development. In D. Matthews (Ed.), Pragmatic development in first language acquisition (pp. 1–11). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, D., & Krajewski, G. (2019). First language acquisition. In E. Dąbrowska, & D. Divjak (Eds.), Cognitive linguistics: A survey of linguistic subfields (pp. 159–181). De Gruyter Mouton. [Google Scholar]

- Ogiermann, E. (2015). In/directness in Polish children’s requests at the dinner table. Journal of Pragmatics, 82, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogiermann, E. (2018). Discourse completion tasks. In A. H. Jucker, K. P. Schneider, & W. Bublitz (Eds.), Methods in pragmatics (pp. 229–255). De Gruyter Mouton. [Google Scholar]

- Panther, K.-U., & Thornburg, L. (2005). Motivation and convention in some speech act constructions: A cognitive linguistic approach. In S. Marmaridou, K. Nikiforidou, & E. Antonopoulou (Eds.), Reviewing linguistic thought: Converging trends for the 21st Century (pp. 53–76). De Gruyter Mouton. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez Hernández, L. (2013). Illocutionary constructions: (Multiple source)-in-target metonymies, illocutionary ICMs, and specification links. Language & Communication, 33, 128–149. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez Hernández, L. (2020). Speech acts in English: From research to instruction and textbook development. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez Hernández, L., & Ruiz de Mendoza, F. J. (2002). Grounding, semantic motivation, and conceptual interaction in indirect directive speech acts. Journal of Pragmatics, 34(3), 259–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakoczy, H., & Schmidt, M. F. H. (2013). The early ontogeny of social norms. Child Development Perspectives, 7(1), 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakoczy, H., & Tomasello, M. (2009). Done wrong or said wrong? Young children understand the normative directions of fit of different speech acts. Cognition, 113, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, K. (2000). An exploratory cross-sectional study of interlanguage pragmatic development. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 22, 27–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, K. (2009). Interlanguage pragmatic development in Hong Kong, phase 2. Journal of Pragmatics, 41, 2345–2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossano, F., & Liebal, K. (2014). “Requests” and “offers” in orangutans and human infants. In P. Drew, & E. Couper-Kuhler (Eds.), Requesting in social interaction (pp. 335–363). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz de Mendoza, F. J., & Baicchi, A. (2007). Illocutionary constructions: Cognitive motivation and linguistic realization. In K. Istvan, & L. Horn (Eds.), Explorations in pragmatics: Linguistic, cognitive, and intercultural aspects (pp. 95–127). De Gruyter Mouton. [Google Scholar]

- Ryckebusch, C., & Marcos, H. (2004). Speech acts, social context and parent-toddler play between the ages of 1;5 and 2;3. Journal of Pragmatics, 36, 883–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safont-Jordà, M.-P. (2013). Early stages of trilingual pragmatic development: A longitudinal study of requests in Catalan, Spanish and English. Journal of Pragmatics, 59, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savić, M., Myrset, A., & Economidou-Kogetsidis, M. (2022). Lived experiences as a resource for scaffolding metapragmatic understandings with young language learners. Language Learning Journal, 50(4), 475–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sealy, A. (1999). “Don’t be cheeky”: Requests, directives and being a child. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 3(1), 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Searle, J. (1976). The classification of illocutionary acts. Language in Society, 5, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sifianou, M. (1992). Politeness phenomena in England and Greece. Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stephany, U. (2021). Development of modality in early Greek language acquisition. In U. Stephany, & A. Aksu-Koç (Eds.), Development of modality in first language acquisition: A cross-linguistic perspective (pp. 255–314). De Gruyter Mouton. [Google Scholar]

- Stephany, U., & Voeikova, M. D. (2015). Requests, their meanings and aspectual forms in early Greek and Russian child language. Journal of Greek Linguistics, 15, 66–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, H. (2012). A cognitive linguistic analysis of the English imperative. With special attention to Japanese imperatives. John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Tomasello, M. (2003). Constructing a language: A usage-based theory of language acquisition. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tomasello, M. (2006). Construction grammar for kids. Constructions, SV1-SV11, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Tomasello, M. (2015). The usage-based theory of language acquisition. In E. L. Bavin, & L. R. Naigles (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of child language (pp. 89–106). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vassilaki, E. (2017). Cognitive motivation in the linguistic realization of requests in Modern Greek. In A. Athanasiadou (Ed.), Studies in figurative thought and language (pp. 105–124). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Vassilaki, E., & Selimis, S. (2020a). Children’s requestive behavior in L2 Greek: Beyond the core request. Corpus Pragmatics, 4(3), 359–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassilaki, E., & Selimis, S. (2020b). Children’s requestive behavior in L2 Greek: The core request. Journal of Pragmatics, 170, 271–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, L. C., Wilkinson, A. C., Spinelli, F., & Chiang, C. P. (1984). Metalinguistic knowledge of pragmatic rules in school-age children. Child Development, 55(6), 2130–2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wootton, A. J. (1981/2014). Two request forms of four year olds. In P. Drew, & E. Couper-Kuhler (Eds.), Requesting in social interaction (pp. 171–183). John Benjamins. (Original work published 1981). [Google Scholar]

- Zufferey, S. (2016). Pragmatic acquisition. In J.-O. Östman, & J. Verschueren (Eds.), Handbook of pragmatics. 2016 Installment. John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

| 4-Year-Olds | 6-Year-Olds | 8-Year-Olds | 11-Year-Olds | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age Range (yrs;mos) | 3;8–5;0 | 6;1–7;1 | 8;2–9;2 | 11;1–12;5 |

| Mean Age (yrs;mos) | 4;5 | 6;6 | 8;7 | 11;6 |

| Total N | 18 | 18 | 17 | 20 |

| Base Construction | Frequency (N of Tokens) | Example |

|---|---|---|

| (i) Can-you V-SUBJUNCTIVE? | 33.3% (193) | Μπορείς να μου δώσεις ένα μπισκότο; (“Can you give me a cookie?”) |

| (ii) Will-you V? | 16.9% (98) | Θα μου δώσεις ένα μπισκότο; (“Will you give me a cookie?”) |

| (iii) Can-I V-SUBJUNCTIVE? | 12.9% (75) | Μπορώ να πάρω ένα μπισκότο; (“Can I take a cookie?”) |

| (iv) V-PRESENT-YOU? | 11.9% (69) | Μου δίνεις ένα μπισκότο; (“Are you giving me a cookie?”) [lit. transl.] |

| Age (yrs) | παρακαλώ (“Please”) | λίγο (“a Little”) | Diminutives | Plural | Supportive Moves |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | + | − | − | − | − |

| 6 | + | + | + | + | + |

| 8 | + | + | + | + | + |

| 11 | + | + | + | + | + |

| Age (yrs) | παρακαλώ (“Please”) | λίγο (“a Little”) | Diminutives | Plural | Supportive Moves |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | + | + | + | − | + |

| 6 | + | + | + | − | + |

| 8 | + | + | + | + | + |

| 11 | + | + | − | + | + |

| Age (yrs) | παρακαλώ (“Please”) | λίγο (“a Little”) | Diminutives | Plural | Supportive Moves |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | + | + | + | − | + |

| 6 | + | + | + | + | + |

| 8 | − | + | + | + | + |

| 11 | + | + | + | − | + |

| Age (yrs) | παρακαλώ (“Please”) | λίγο (“a Little”) | Diminutives | Plural | Supportive Moves |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | + | + | − | − | + |

| 6 | + | + | + | − | + |

| 8 | + | + | + | + | + |

| 11 | + | + | − | + | + |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Selimis, S.; Vassilaki, E. The Development of Children’s Request Strategies in L1 Greek. Languages 2026, 11, 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages11010019

Selimis S, Vassilaki E. The Development of Children’s Request Strategies in L1 Greek. Languages. 2026; 11(1):19. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages11010019

Chicago/Turabian StyleSelimis, Stathis, and Evgenia Vassilaki. 2026. "The Development of Children’s Request Strategies in L1 Greek" Languages 11, no. 1: 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages11010019

APA StyleSelimis, S., & Vassilaki, E. (2026). The Development of Children’s Request Strategies in L1 Greek. Languages, 11(1), 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages11010019