Abstract

This paper discusses a special type of complement of perception verbs in Serbian, introduced by kako (‘how’). Via a parallel corpus analysis, I compare the distribution of Serbian kako-clauses and English -ing forms. I show that two types of non-interrogative kako-clauses can be used in translations of English -ing forms, distinguished based on their formal and interpretive properties: ‘eventive’ and propositional kako-clauses. Eventive clauses focus on directly perceived events and cannot be negated or combined with epistemic verbs, while propositional clauses express beliefs or judgments and have a truth value. At a formal level, eventive clauses feature a null subject, while propositional clauses feature an overt nominative subject. I argue that this distinction is captured syntactically through the notion of phasehood, with only propositional clauses merging a full CP domain. Adopting the Form-Copy operation, I propose that eventive clauses lack a phase boundary, allowing for the deletion of a lower subject copy and yielding the observed case alternation and null embedded subject. This analysis offers a unified syntactic account of kako-complements and contributes to the typology of perception-based clause embedding.

1. Introduction

The syntactic nature of complements of perception verbs introduced by ‘how’ has been the focus of a number of studies in the generative tradition, mainly concerned with Germanic languages (Casalicchio (2021) on German, Corver (2023) on Dutch, among others). Complements of perception verbs introduced by ‘how’ are semantically distinct from interrogative manner clauses, which are similarly introduced by ‘how’, as the former do not describe the method of an action but focus on directly observed events, highlighting their role in expressing sensory experience rather than indirect questions. In English, complements of perception verbs are generally translated by means of an -ing form, while Romance languages often use separate pseudo-relative constructions.

In this paper, I analyze parallel constructions in Serbian, where the complements of perception verbs are introduced by kako (‘how’). Via a parallel corpus analysis, I compare the distribution of Serbian kako-clauses and English -ing forms. The results of the corpus analysis show that two types of non-interrogative kako-clauses can be used in translations of English -ing forms, distinguished based on their formal and interpretive properties: eventive and propositional kako-clauses. Eventive clauses focus on directly perceived events and cannot be negated or combined with epistemic verbs, while propositional clauses express beliefs or judgments about a situation and have a truth value. At a formal level, eventive clauses feature a null subject, while propositional clauses feature an overt nominative subject. A comparison with Romance pseudo-relatives, similarly used in parallel contexts with perception verbs, shows that Serbian kako-clauses are structurally distinct from relative clauses; rather, they behave as regular embedded clauses.

I will argue in favor of a minimalist syntactic analysis that stems from a key distinction between eventive and propositional kako-clauses, which is syntactically captured by adopting the notion of phasal domain and the Form-Copy operation (Chomsky, 2021), to define the distinction between the two types of complement at a formal and interpretive level.

The paper is organized as follows: Section 2 introduces the type of Serbian kako-clauses used with perception verbs, highlighting their differences from manner kako-clauses. Section 3 presents a corpus analysis, based on the Slavicus Corpus of Baltic and Slavic languages (Rozwadowska et al., 2025), directly comparing the distribution of English -ing forms with Serbian kako-clauses. Section 4 proposes a typology of non-interrogative kako-clauses in Serbian, defining two types based on their interpretive properties: eventive and propositional kako-clauses; eventive clauses are subsequently compared with Romance pseudo-relatives, which are also used with perception verbs. Section 5 proposes a Minimalist syntactic treatment of Serbian kako-clauses; I argue for a Form-Copy analysis (Chomsky, 2021), showing that both eventive and propositional clauses allow for parallel syntactic derivations, but only the latter constitute phasal domains, determining their distinct formal and interpretive properties. Section 6 concludes the paper.

2. Interrogative and Non-Interrogative Kako-Clauses

In Serbian1, perception verbs often combine with a particular type of predicative clause introduced by the element kako (‘how’). Unlike standard complement clauses, which may describe indirect or inferred perception, kako-clauses are semantically more constrained: they require the direct and immediate perception of an event. In other words, the event described within a kako-clause must be something the subject explicitly observes, rather than infers or imagines.

Consider the following sentence, where the perception verb gledam (‘I am watching’) is followed by a clause introduced by kako. This complement structure encodes an event that is being directly witnessed by the subject:

| (1) | Gleda-m | mačk-u2 | kako | trči. |

| watch-prs.1sg | cat-acc.sg | how | run-prs.3sg | |

| ‘I am watching the cat running.’ | ||||

In this example, the kako-clause conveys an ongoing action that is perceptually accessible to the subject. The event of the cat running is not merely presumed or reconstructed; it is directly and visually observed. This interpretation contrasts with that of standard complement clauses, which can refer to indirect perception or inferential knowledge.

A key distinction arises when comparing kako-clauses that occur in perception verb constructions such as (1) with those that appear in interrogative-like manner contexts. In such cases, kako introduces a clause that specifies the method or manner in which an action takes place. These manner clauses typically answer the question of how something happened and are not linked to the direct perception of an event. For instance, in (2), the complement clause introduced by kako expresses the way in which a problem was solved, though it does not imply that the solving event was directly observed by the subject. Instead, the clause encodes an indirect counterpart of the question in (3), yielding an indirect interrogative interpretation:

| (2) | Objasni-l-a | je | kako | je | reši-l-a | problem. |

| explain-ptcp-sgf | aux.prs.3sg | how | aux.prs.3sg | solve-ptcp-sgf | problem | |

| ‘She explained how she solved the problem.’ | ||||||

| (3) | Kako | je | reši-l-a | problem? | Brzo/ | pažljivo/ | dobro. |

| how | aux.prs.3sg | solve-ptcp-sgf | problem | fast | carefully | well | |

| ‘How did she solve the problem? Fast/carefully/well.’ | |||||||

As illustrated in (3), the clause introduced by kako has a clear manner interpretation, which is further supported by the possibility of replacing kako with other manner adverbials in the answer. This contrasts with perception-based kako-clauses, which do not necessarily encode the manner of an action.

Another important interpretive cue is aspect. In (2) and (3), the use of the perfective verb form rešila (‘solved’) points to a completed action, and thus aligns with the indirect, non-perceptual reading of the kako-clause. In contrast, perception verb contexts such as (1) typically favor imperfective or ongoing event interpretations, highlighting the role of direct sensory experience.

In this paper, I argue that kako-complements in perception contexts, such as (1), are semantically distinct from interrogative-like manner clauses. In particular, they lack true manner semantics. This is evident in cases where kako co-occurs with a manner adverb within the same sentence, without yielding redundancy or ungrammaticality (4):

| (4) | Hari | ga | je | ču-o | kako | zamuck-u-je | gore | nego | ikad. |

| Harry.nom | he.acc | aux.prs.3sg | hear-ptcp.sgm | how | stutter-prs-3sg | worse | than | ever | |

| ‘Harry heard him stuttering worse than ever.’ | |||||||||

In sentence (4), the kako-clause does not function as an indirect interrogative manner complement. Rather, it behaves like a regular declarative clause that encodes a directly perceived event. The clause simply describes what Harry heard. The interpretation here lacks the interrogative force associated with the interrogative manner kako.

Further evidence for the non-interrogative status of such kako-clauses comes from coordination patterns. In contexts where kako appears alongside other interrogative wh-words, such as gde (‘where’), the clause can easily be interpreted as an indirect question. This is the case in (5), where both gde and kako are coordinated to describe the location and manner of the birds’ flight, making the presence of additional manner adverbs implausible:

| (5) | Gleda-mo | ih | kako | i | gde | let-e (*visoko) | (*po vazduhu). |

| watch-prs.1pl | they. acc | how | and | where | fly-prs.3pl high | in air | |

| ‘We are watching how and where the birds fly.’ | |||||||

By contrast, in (6), the attempt to coordinate kako with gde, results in ungrammaticality. This is because the clause in (6) does not constitute an indirect question but rather a direct perceptual report of an ongoing event, as evidenced by the presence of other manner (‘high’) and locative (‘in the air’) modifiers:

| (6) | Gleda-mo | ih | kako | (*i | gde) | let-e | visoko | po | vazduhu. |

| watch-prs.1pl | they.acc | how | and | where | circle-prs.3pl | high | in | air | |

| ‘We are watching how and where they fly high in the air.’ | |||||||||

Although the kako-clauses in (5) and (6) exhibit similar superficial properties, their syntax and semantics diverge significantly. Sentence (6) illustrates that perception-based kako-clauses are not compatible with the distributional pattern’s characteristic of interrogative complements. Instead, they function as event-denoting complements, tied closely to the sensory experience of the subject.

In conclusion, kako-clauses associated with perception verbs form a distinct grammatical class, which I will define as eventive (see Corver, 2023, for a similar approach to Dutch how-complements). They differ both syntactically and semantically from manner and interrogative kako-clauses. While the former encode directly perceived events and permit co-occurrence with manner adverbials, the latter involve method-of-action readings and exhibit distributional properties consistent with embedded questions.

3. A Corpus Analysis of Serbian Non-Interrogative Kako-Clauses

In order to establish the exact distribution of non-interrogative kako-clauses, I carried out a parallel corpus analysis on three different texts: Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone, The Hobbit, and Murder on the Orient Express, using the Slavicus Parallel Corpus of Baltic and Slavic languages (Rozwadowska et al., 2025)3. This analysis focused on identifying all instances in which the English versions of these texts contained an -ing form following a transitive perception verb and comparing their Serbian translations. The comparison with English is motivated by the fact that -ing clauses are the canonical realization of perception complements in English and are semantically similar to the Serbian kako-clauses under investigation. By aligning English -ing clauses with their Serbian counterparts in a parallel corpus, we can systematically identify how Serbian expresses similar meanings, and what syntactic structures it uses to do so. This approach reveals the existence of two distinct types of kako-clauses (eventive and propositional), which are not readily distinguishable in English, as I will discuss in Section 4. Thus, the English comparison serves both as a baseline for semantic equivalence and as a tool for uncovering structural and interpretive variation in Serbian.

The corpus analysis revealed a total of 115 instances across the three books where such -ing forms appeared. In Serbian, these -ing forms are generally translated using various types of clauses, including kako-clauses, relative clauses, and subordinate clauses, highlighting the flexibility and diversity of options available in Serbian when handling the translation of -ing constructions.

Out of the 115 contexts, 75 of the English -ing forms were translated in Serbian using eventive kako-clauses, such as the ones illustrated in Section 2. This structure is the most frequent option in translation, making up 65.22% of the total analyzed contexts. Example (7) shows a Serbian eventive kako-clause translating an English -ing form, highlighting direct perception of an event by the subject:

| (7) | Ču-o | je | Račet-a | kako | se | kreć-e | u | susednom | kupeu. |

| hear-ptcp.sgm | aux.prs.3sg | Ratchett-acc | how | refl | move-prs.3sg | in | next | compartment | |

| ‘He heard Ratchett moving in the next compartment.’ | |||||||||

In this example, the verb čuo (‘heard’) has a direct object, followed by a complement introduced by kako (‘how’), which simply presents the ongoing event of Ratchett moving. This event is directly perceived by the subject.

The remaining translations are rendered by three types of constructions, which will be discussed below and in the following sections: a second type of kako-clause, which minimally differs from the one in (7); relative clauses introduced by koji (‘which’); and one single instance of an embedded clause introduced by the particle da.

The second most common translation of the English -ing forms in the corpus corresponds to a second type of kako-clause, with 21 instances (18.26% of the total). In (8), the kako-clause features an overt nominative subject; at the interpretive level, such contexts express a more evaluative meaning, where the event described can be judged for its truth value:

| (8) | Vide-še | kako | jark-o | sunc-e | sija | nad | zemljama | razasutim | u | beskraj. |

| see-aor.3pl | how | bright-nom | sun-nom | shine-prs.3sg | over | lands | scattered | in | infinity | |

| ‘He saw how the bright sun shines over the lands scattered in the infinity.’ | ||||||||||

While the interpretation of (8) remains rooted in direct perception of an event, the complement in this case also presents a statement that can be judged true or false, whether or not the sun actually shone over the lands. As will be shown in Section 4, this introduces a layer of propositionality, distinguishing it from purely eventive structures; I will refer to these as propositional clauses. It is important to note that, although still directly perceptible, the clause has an added dimension of truth evaluation, making it more akin to a factual claim than just a description of an ongoing action.

The third, less frequent translation type corresponds to relative clauses introduced by the relativizer koji, with 10 instances (8.69%). These relative clauses often function to introduce additional descriptive information or actions related to the noun, without necessarily involving direct perception of an event, as in (9):

| (9) | Na | prvom | ćošku | primeti-o | je | mačk-u, | koja | proučav-a | mapu. |

| at | first | corner | notice-ptcp.sgm | aux.prs.3sg | cat-acc | that | study-prs.3sg | map | |

| ‘At the first corner he noticed a cat studying a map.’ | |||||||||

The English -ing form “studying” is translated by the relative clause koja proučava mapu (‘who is studying the map’). Unlike the eventive clauses previously discussed, relative clauses do not require direct perception of the event. This difference becomes clear when we turn the verb into the past tense and introduce the adverb ‘earlier’, as shown in (10):

| (10) | Primeti-o | je | mačk-u, | koja | je | ranije | proučava-l-a | mapu. |

| notice-ptcp.sgm | aux.prs.3sg | cat-acc | that | aux.prs.3sg | earlier | study-ptcp-sgf | map | |

| ‘He noticed the cat that had been earlier studying the map.’ | ||||||||

Here, the event of the cat studying the map is no longer a present action that the subject directly perceives, but an action that has already occurred prior to the moment of perception. This shift in tense and the inclusion of ‘earlier’ mark the event as something observed indirectly, further distinguishing it from an eventive complement. I will return to the distribution of relatives and kako-clauses in Section 4.

Finally, only one instance corresponds to a subordinate clause introduced by da, which is widely used in Serbian to introduce various types of embedded clauses (see Wurmbrand et al., 2020, for an overview). This construction formally mirrors the propositional type of kako-clause (8), where the perception verb is followed by an embedded clause introduced by the complementizer da. This structure is illustrated in the following example:

| (11) | Patuljc-i (…) | ču-še | da | čarobnjak | ovako | govor-i | Bilb-u. |

| dwarves-nom | hear-aor.3pl | that | wizard.nom | this | speak-prs.3sg | Bilbo-dat | |

| ‘The dwarves heard the wizard talking like this to Bilbo.’ | |||||||

In (11), the complement clause introduced by da4 presents a proposition about what was heard, similar to the propositional type of kako-clause. Though structurally different, it serves a similar role in embedding a statement that can be evaluated as true or false.

The distributional frequencies observed in the corpus are crucial in identifying the preferred syntactic strategies Serbian employs to express perception complements. The fact that eventive kako-clauses account for more than 65% of all translations of English -ing constructions suggests that they are the unmarked choice in contexts involving direct perceptual experience. In contrast, propositional kako-clauses and relative clauses, which occur significantly less frequently, appear to reflect contextually specialized interpretations, such as evaluative judgments or background descriptions. Thus, the relative frequencies support the claim that Serbian distinguishes structurally and functionally between multiple types of perception-related complements, and that this variation is systematically influenced by semantic and syntactic factors. The analysis proposed in Section 4 and Section 5 aims at distinguishing eventive and propositional kako-clauses, additionally separating them from relative clauses. The analysis can be preliminarily extended to embedded configurations such as (11), but more evidence on the possible structural identity between this structure and kako-clauses is a matter of future research.

4. Towards a Typology of Non-Interrogative Kako-Clauses

4.1. Eventive and Propositional Complements

In Section 2, I established a first distinction between interrogative and non-interrogative uses of kako. Section 3 was devoted to the definition of their distribution via a corpus analysis; this analysis highlighted a more fine-grained classification of non-interrogative kako-clauses. More specifically, Section 3 considered constructions in which the perceived referent appears as the object of the perception verb in the matrix clause, while the subject of the kako-clause is null, as seen in (1), repeated here as (12). However, the corpus data highlighted that structures such as (34) alternate with a structurally distinct type of kako-construction: kako-clauses in which the perceived noun phrase follows kako and functions as the subject of the complement clause itself, as in (13):

| (12) | Vid-im | mačk-u | kako | trč-i. |

| see-prs.1sg | cat-acc | how | run-prs.3sg | |

| ‘I see the cat running.’ | ||||

| (13) | Vidi-m | kako | mačk-a | trč-i. |

| see-prs.1sg | how | cat-nom | run-prs.3sg | |

| ‘I see that the cat is running.’ | ||||

In the sentence in (13), the noun phrase mačka (‘cat’) appears in the nominative case, identifying it as the grammatical subject of the kako-clause. This contrasts with (12), where the embedded subject is unexpressed and controlled by the object of the matrix perception verb, which appears in the accusative case.

Beyond their formal divergence, I will propose that kako-clauses of the type illustrated in (13) are propositional in nature. That is, they encode information that can be treated as a statement about the world, something that can be assessed in terms of truth or falsity. These clauses can convey claims, beliefs, or assertions, and their truth value can depend on whether the situation described corresponds to reality. This is clearly shown by the possibility of embedding a kako-clause with an overt nominative subject under an epistemic verb such as ‘believe’, as shown in (14):

| (14) | Demokrit | je | nastavi-o | da | ver-u-je | kako | je | zemlj-a | ravna. |

| Democritus | aux.3sg | continue-ptcp.sgm | that | believe-prs-3sg | how | be.3sg | earth-nom | flat | |

| ‘Democritus continued to believe that the earth was flat.’ | |||||||||

In (14), kako introduces a clause expressing a belief. The truth expressed by the embedded clause is potentially verifiable based on how events unfold. Notably, clauses of this kind display a wider distribution than eventive clauses, as they can occur with a broader range of verbs, including epistemic or cognitive verbs such as veruje (‘believe’).

In contrast, it is not possible to construct a parallel version of (14) in which the perceived referent functions as the object of the main verb:

| (15) | *Demokrit | je | nastavi-o | da | ver-u-je | zemlj-u | kako | je | ravna. |

| Democritus | aux.3sg | continue-ptcp.sgm | that | believe-prs-3sg | earth-acc | how | be.3sg | flat | |

| ‘Democritus continued to believe that the earth was flat.’ | |||||||||

This contrast supports the proposal that constructions involving an accusative-marked perceived object are not propositional but eventive. Eventive kako-clauses describe actions, processes, or events unfolding in the real world. Their primary function is to report on observable occurrences, emphasizing the perceptual experience of witnessing something happen. These clauses do not present a proposition to be judged as true or false; rather, they focus on the happening itself. Because of this, they cannot appear with cognitive or knowledge verbs, as such verbs require propositional content.

A further diagnostic for this distinction is the incompatibility of eventive clauses with negation (see Barwise, 1981). This follows from the fact that a direct observation inherently favors the reporting of events that actually take place. As shown in (16), the attempt to describe a non-event leads to pragmatic implausibility:

| (16) | #Primeti-l-a | sam | Ac-u | kako | ne | dolaz-i | kući. |

| notice-ptcp-sgf | aux.prs.1sg | Aca-acc | how | neg | come-prs.3sg | home | |

| ‘I noticed Alex not coming home.’ | |||||||

Although the sentence is not ungrammatical, it is pragmatically marked: one cannot easily perceive someone not doing something. Since eventive clauses aim to capture direct sensory input, expressing the absence of an event contradicts their core function.

In contrast, the propositional counterpart in (17) more freely allows for negation:

| (17) | Primeti-l-a | sam | kako | Ac-a | ne | dolaz-i | kući. |

| notice-ptcp-sgf | aux.prs.1sg | how | Aca-nom | neg | come-prs.3sg | home | |

| ‘I noticed that Alex was not coming home.’ | |||||||

Here, the negation is semantically and pragmatically acceptable because the clause describes a subjective judgment on a state or general situation that did not take place, rather than describing a specific dynamic action. The speaker’s observation refers to a perceived situation that can be subjectively interpreted or inferred, making it compatible with the nature of propositional content. In other words, the perceptual experience does not target the absence of an event per se, but rather leads the subject to infer that a certain expected event is not taking place. In this sense, the perceptual input provides cues for an epistemic judgment, hence the propositional reading5.

The two tests discussed above (the possibility of embedding a kako-clause under an epistemic verb and the availability of negation) confirm that only the propositional kako-clauses have truth values and therefore behave as canonical propositions, unlike eventive kako-clauses, which denote events and lack truth-evaluability.

Ultimately, this distinction reflects a fundamental divide in the typology of non-interrogative kako-clauses: eventive complements require the speaker to have perceptually experienced the event, whereas propositional clauses report on beliefs, judgments, or statements that can be assessed for their truth value. The impossibility of negation and limited verb compatibility in eventive clauses further supports their status as perceptually anchored and non-propositional.

4.2. Kako-Clauses and Pseudo-Relatives: A Parallel with Romance

4.2.1. Romance Pseudo-Relatives

Besides the difference between propositional and eventive kako-clauses, the corpus analysis showed that relative clauses are also sometimes used in the translation of English -ing forms; such alternance invites a natural comparison with Romance pseudo-relatives, which regularly translate English -ing forms in languages such as French and Italian6.

Romance pseudo-relatives are formally and structurally quite similar to relative clauses, but, as with Serbian kako-clauses, are characteristically associated with perception verbs and are used to describe ongoing events that are directly witnessed by the perceiver. This parallel is particularly evident in their semantic function: both constructions convey an event tied to a specific referent that is perceptually accessible at the time of utterance. In English, Romance pseudo-relatives are typically rendered using the -ing form. Consider the French example in (18):

| (18) | J’=ai | vu | le | chat | qui | cour-ait. |

| I=aux.prs.1sg | see.ptcp | det | cat | that | run-ipf.3sg | |

| ‘I saw the cat running.’ | ||||||

In this example, qui courait (‘who was running’) is formally identical to a relative clause, yet it functions not merely to modify the noun phrase le chat (‘the cat’), but rather to predicate a state or action of the referent at the moment of perception (see Casalicchio, 2013, for a discussion). As already shown for Serbian eventive kako-clauses, the embedded clause in Romance pseudo-relatives establishes a predicative relationship between the perceived entity and the event, rather than supplying additional descriptive information in the way standard relative clauses would. This predicative function highlights the distinct nature of pseudo-relatives, setting them apart from both restrictive and non-restrictive relatives.

From a structural perspective, two main syntactic analyses have been proposed for Romance pseudo-relatives, which provide a useful framework for further examining the structure of Serbian kako-clauses. One approach treats pseudo-relatives as CP-like small clauses (Radford, 1975; Kayne, 1975; Guasti, 1988), with the entire pseudo-relative functioning as a clausal complement, as illustrated in (19a). A competing analysis interprets pseudo-relatives as DP-like structures (Burzio, 1986), aligning them more closely with regular relative clauses, where the embedded clause is nested within the determiner phrase, as shown in (19b):

| (19) | a. | [DP le chat] | [CP qui courait]. |

| b. | [DP le chat | [CP qui courait]]. | |

| det cat | that run-ipf.3sg | ||

| ‘I saw the cat running.’ | |||

Numerous syntactic and semantic diagnostics have been proposed to distinguish pseudo-relatives from standard relative clauses, including constraints on antecedent types, compatibility with stative and modal predicates, and differences in aspectual interpretation (Casalicchio, 2013). In Section 4.2.2, I will apply some tests to Serbian kako-eventive complements in order to better determine their structural classification and to assess the extent to which they pattern with Romance pseudo-relatives both syntactically and semantically.

4.2.2. Pseudo-Relatives or Just Relatives?

The corpus study revealed that kako-clauses can alternate with relative clauses in Serbian. In this section, I will show that these two structures are interpretively distinct. As in the case of Romance pseudo-relatives, Serbian eventive kako-clauses display a strong formal resemblance to relative clauses, but they diverge significantly in terms of interpretation, distribution, and syntactic constraints. Formally, Serbian relative clauses are introduced by relative pronouns such as koji (‘who/which’) and što (‘that’), yielding either restrictive or non-restrictive readings (Browne, 1986; Kordić, 1995; Gračanin-Yuksek, 2013).

At the interpretive level, relative clauses do not require the direct perception of an event. Rather, they serve to attribute general or habitual properties to the antecedent, regardless of whether these are witnessed at the moment of utterance (Alexiadou et al., 2000). This contrast becomes particularly salient when considering indirect perception contexts. For example, in (20), the relative clause simply conveys a past habitual activity associated with the object of the perception verb. The action is not necessarily being observed in real time but instead serves to provide background or descriptive information about the referent. In contrast, (21) is impossible, as kako introduces an eventive clause that reports a directly observed, ongoing event. This interpretive difference highlights the special interpretation assigned to kako-clauses, which establish a real-time relationship between the perceiving subject and the perceived action:

| (20) | Vid-im | Marij-u, | koja | je | nekad | često | šeta-l-a | po | parku. |

| see-prs.1sg | Mary-acc | who | aux.1sg | earlier | often | walk-ptcp-sgf | in | park | |

| ‘I see Mary, who earlier often walked in the park.’ | |||||||||

| (21) | *Vid-im | Marij-u | kako | je | nekad | često | šeta-l-a | po | parku. |

| see-prs.1sg | Mary-acc | how | aux.1sg | earlier | often | walk-ptcp-sgf | in | park | |

| ‘I see Mary (*earlier often) walking in the park.’ | |||||||||

In this respect, Serbian kako-clauses allow for a direct comparison with French pseudo-relatives, which exhibit the same distinction. Despite being introduced by the same element (qui), only the relative clause (22) can convey a past habitual meaning; the same meaning is impossible in a pseudo-relative reading (23):

| (22) | Je vo-is | Marie, | qui | se | promen-ait | souvent | dans | le | parc | autrefois. |

| I see-prs.1sg | Mary | who | refl | walk-ipf.3sg | often | in | the | park | earlier | |

| ‘I see Mary, who earlier often walked in the park.’ | ||||||||||

| (23) | *Je vo-is | Marie | qui | se | promen-ait | souvent | dans | le | parc | autrefois. |

| I see-prs.1sg | Mary | who | refl | walk-ipf.3sg | often | in | the | park | earlier | |

| ‘I see Mary (*earlier often) walking in the park.’ | ||||||||||

Further evidence for this distinction comes from clitic antecedents. While the kako-clauses in (24) in Serbian readily allow a clitic antecedent, the relative clause in (25) categorically disallows them:

| (24) | Vid-im | je | kako | trč-i | po | parku. |

| see-prs.1sg | she.acc | how | run-prs.3sg | in | park | |

| ‘I see her running in the park.’ | ||||||

| (25) | *Vid-im | je | koja | trč-i | po | parku. |

| see-prs.1sg | she.acc | who | run-prs.3sg | in | park | |

| ‘I see her, who runs in the park.’ | ||||||

Again, the comparison with French suggests a systematic distinction between the two types of clauses. If the antecedent of the clause is a clitic (26), only a pseudo-relative interpretation is possible:

| (26) | Je | la | vois | qui | court. |

| I | she.acc | see-prs.1sg | who | run-prs.3sg | |

| ‘I see her running/*who runs.’ | |||||

While there is no formal way to distinguish a relative from a pseudo-relative reading of (26), the only plausible reading reflects a context in which the subject witnesses someone in the act of running.

Another point of divergence between the two structures concerns compatibility with stative verbs. Kako-clauses impose restrictions on stativity: they are generally limited to contexts in which the stative predicate describes a temporary or dynamic state. For example, (27) is fully acceptable, as ‘laughing’ is a transitory state. However, (28) is anomalous, since eye color represents a permanent, non-eventive property. In contrast, relative clauses readily accommodate stative predicates regardless of their permanence, as shown by (29):

| (27) | Ču-l-a | sam | Aleks-u | kako | se | smej-e. |

| hear-ptcp-sgf | aux.prs.1sg | Aleksa-acc | how | refl | laugh-prs.3sg | |

| ‘I heard Aleksa laughing.’ | ||||||

| (28) | *Vide-o | sam | An-u, | kako | im-a | plave | oči. |

| see-ptcp.sgm | aux.prs.1sg | Ana-acc | how | have-prs.3sg | blue | eyes | |

| ‘I saw Ana having blue eyes.’ | |||||||

| (29) | Vide-o | sam | An-u, | koja | im-a | plave | oči. |

| see-ptcp.sgm | aux.prs.1sg | Ana-acc | who | have-prs.3sg | blue | eyes | |

| ‘I saw Ana, who has blue eyes.’ | |||||||

Also in this case, French exhibits an identical pattern: pseudo-relatives (30) allow only for temporary states, while relative clauses (31) allow for permanent states, too7:

| (30) | J’=ai | vu | Alexandre | qui | souri-ait. |

| I=aux.prs.1sg | see.ptcp | Alexander | who | smile-ipf.3sg | |

| ‘I saw Alexander smiling.’ | |||||

| (31) | J’=ai | vu | Anne, | qui | avait | les | yeux | bleus. |

| I=aux.prs.1sg | see.ptcp | Anne | who | have-ipf.3sg | det | eyes | blue | |

| ‘I saw Anne, who has blue eyes.’ | ||||||||

Taken together, these observations highlight the unique properties of pseudo-relatives compared to standard relative clauses. While both constructions share formal similarities, pseudo-relatives are crucially tied to the domain of direct perception and eventive interpretation, distinguishing them from the more descriptive and structurally flexible relative clauses. The parallels with French pseudo-relatives further confirm that these properties are not language-specific but instead reflect a broader cross-linguistic pattern of eventive clauses.

5. Analysis

5.1. The Structure of Relatives and Kako-Clauses

The comparison between Serbian kako-clauses and French pseudo-relatives clearly indicates that the difference between both such structures and relative clauses requires a principled formal analysis. The nature of Romance relative and pseudo-relative clauses has been the object of a wide number of studies in the generative tradition (Burzio, 1986; Guasti, 1988; Cinque, 1992; Casalicchio, 2013, among others), while the literature on Slavic is more limited (see Arsenijević (2009) for an analysis of complement and relative clauses in Serbian, and Šimík and Sláma (2023) for an analysis of Czech how-complements). Before moving to the analysis of kako-clauses, I will therefore reflect more extensively on the structural difference existing between kako-clauses and relative clauses in Serbian. The picture that will emerge will later allow me to formulate a detailed syntactic analysis of propositional and eventive kako-clauses.

A key difference that supports the distinct syntactic status of relative clauses and kako-clauses is their behavior in contexts of long NP movement in passives (32) and insertion of a locative PP between the NP Iva and the kako-clause (33), both of which are available for pseudo-relatives but not for relatives:

| (32) | Iv-a | je | viđ-ena | kako | hod-a | po | parku. |

| Iva-nom | aux.prs.3sg | see-ptcp-sgf | how | walk-prs.3sg | in | park | |

| ‘Iva was seen walking in the park.’ | |||||||

| (33) | Vide-o | sam | Iv-u | u | parku | kako | hod-a. |

| see-ptcp.sgm | aux.prs.3sg | Iva-acc | in | park | how | walk-prs.3sg | |

| ‘I saw Iva in the park walking.’ | |||||||

In both examples, the eventive kako-clause behaves as a separate, independent constituent. This contrasts with relative clauses, which, due to their syntactic structure, do not exhibit the same flexibility.

| (34) | *Iv-a | je | viđ-ena | koja | hod-a | po | parku. |

| Iva-nom | aux.prs.3sg | see-ptcp-sgf | who | walk-prs.3sg | in | park | |

| ‘Iva was seen, who walks in the park.’ | |||||||

| (35) | *Vide-o | sam | Iv-u | u | parku | koja | hod-a. |

| see-ptcp.sgm | aux.prs.3sg | Iva-acc | in | park | who | walk-prs.3sg | |

| ‘I saw Iva in the park, who walks.’ | |||||||

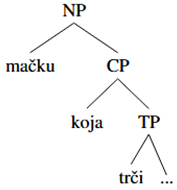

I propose that the distinct behavior of relatives (34) and (35) and kako-clauses (32) and (33) arises from a structural difference between the two constructions, which has significant implications for both their syntax and interpretation. In particular, I follow Kayne (1994) in arguing that relative clauses are generally analyzed as being embedded under their head noun; the head noun of the relative clause originates within a relative CP before moving to its surface position. The relative clause is embedded inside the NP it modifies, and the event described in the relative clause is not seen as an independent event, but rather as part of the nominal phrase. The relative clause has the simplified representation in (36):

| (36) |  |

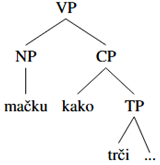

In contrast, kako-clauses, following the proposals of Kayne (1975), Cinque (1992), and Casalicchio (2013), have a distinct structural configuration, where the kako-clause and its antecedent are separate constituents. This independent structure accounts for the control-like relationship in which the null subject of the kako-clause must be co-referential with the NP antecedent, as shown in (37):

| (37) |  |

In view of configurations such as the ones exemplified in (32) and (33), I argue that this is the only structure available for Serbian kako-clauses, which do not allow for an analysis in line with Burzio’s (1986) DP analysis of Romance pseudo-relatives.

The structural differences schematically represented in this section reinforce the broader syntactic distinction between relative clauses and kako-clauses introduced in Section 4.2.1 as a comparison with pseudo-relatives. While relative clauses (and at least some Romance pseudo-relatives) are inherently nominal in nature, modifying an NP within a larger syntactic unit, kako-clauses behave like clausal complements. The structural properties of kako-clauses will be refined and further developed in Section 5.2.

5.2. The Form-Copy Analysis

Having defined kako-clauses as complements, I will now move to the interpretive difference between the eventive and propositional types. I propose that the contrast between the two types of kako-clauses depends on the presence of a perspective phrase (PerspP) in the external part of the C-domain in propositional, but not in eventive clauses. The notion of a PerspP originates in Sundaresan (2012), who proposes it as a high left-peripheral projection in the CP domain that encodes the perspective holder, the individual whose point of view is relevant for interpreting the embedded clause. PerspP has been independently motivated in a variety of languages and constructions, including logophoric clauses and evidential or attitude contexts (see Speas & Tenny, 2003; Anand & Nevins, 2004). In such contexts, PerspP often hosts a silent operator that determines the clause’s temporal, locative, or epistemic anchoring, and is closely tied to evidential or propositional interpretations. The Serbian propositional kako-clauses show similar behavior: they express judgments, beliefs, or evaluable content tied to the speaker or subject’s perspective, and they pattern with other constructions known to project PerspP. Their compatibility with negation, truth value tests, and embedding under attitude verbs further supports the presence of PerspP, which in turn correlates with their phasal status in our analysis. The presence or absence of PerspP explains the different behavior of the two types of complements with respect to subjective perception in (16) and (17).

In line with Sundaresan (2012), I propose that PerspP is located quite high in the C-domain. In a cartographic approach to the CP (Rizzi, 1997), I argue that PerspP is higher than ForceP, which implies that the full left-periphery needs to be merged in the structure:

| (38) | [PerspP [ForceP [TopP [FocP [FinP [… ]]]]]]8 |

Following Chomsky (2001), I propose that full CPs identify a phasal domain. Therefore, the presence or absence of a perspective center in the left periphery of the clause reflects a fundamental structural distinction: propositional complement clauses, the ones that feature a PerspP over ForceP, identify a phasal domain; conversely, eventive complements are smaller than that and maximally merge a FinP, which does not identify a phasal domain.

In syntactic terms, this means that propositional complement clauses are sent off for interpretation before moving to the next phase and are therefore closed structure chunks that are not accessible to the next phase for modifications or syntactic operations. Conversely, eventive complements remain accessible for further computation: the lack of a phase edge allows for modifications and syntactic operations to take place between the eventive complement and the upper phase.9

I propose that kako is merged in FinP (see Krapova, 2010) in both propositional and eventive complement clauses, but only the former (39) further merges a full CP (that is, a fully realized left periphery, up to ForceP; see Rizzi, 1997), while the latter (40) does not:

| (39) | a. | Vid-im | kako mačk-a | trč-i. |

| see-prs.1sg how | cat-nom | run-prs.3sg | ||

| ‘I see the cat running.’ | ||||

| b. | [CP-matrix [TP [vP [VP --|phase edge|-- [PerspP [ForceP [FinP kako … ] ] ] ] ] ] ] | |||

| (40) | a. | Vid-im | mačk-u | kako trč-i. |

| see-prs.1sg | cat-nom | how run-prs.3sg | ||

| ‘I see the cat running.’ | ||||

| b. | [CP-matrix [TP [vP [VP [FinP kako … ] ] ] ] ] | |||

In the remainder of this section, I will show that the distinction illustrated in (39) and (40) is crucial in the definition of the type of syntactic operations that can take place between the subject of the kako-clause and the object of the matrix perception verb.

5.2.1. Introducing Form-Copy

The analysis I adopt in this paper builds on Chomsky (2021), who introduces Form-Copy (FC) as an operation that applies at the level of Logical Form (LF) and establishes a copy relation between structurally identical elements within a sentence to account for phenomena such as obligatory control (see also Asudeh & Toivonen, 2012). Before presenting the analysis, it is important to motivate the choice of Form-Copy (FC) over traditional PRO-based control. While the use of PRO has been widely used to account for null embedded subjects in control constructions starting from Chomsky 1981 (see Landau, 2013, for an overview), it relies on a special null category with no phonological realization or direct syntactic evidence. In contrast, the FC approach (Chomsky, 2021) derives control-like dependencies through copy-deletion at Logical Form, without introducing additional primitives. Crucially, Serbian perception verbs are not canonical control predicates10, and the structural and case properties of eventive kako-clauses (particularly the accusative-marked matrix NP and null embedded subject) are more transparently captured by a copy-based mechanism that is sensitive to phasehood and accessibility. The analysis below adopts FC for these reasons, aligning with a broader minimalist effort to unify movement and control phenomena.

The FC approach builds on Hornstein (1999) and addresses the theoretical distinction between control and raising in generative grammar. As with Hornstein (1999), Chomsky (2021) challenges this distinction. While in traditional approaches to control, the antecedent is connected to PRO through binding in raising movement creates a chain linking the subject to its position in the embedded clause. Hornstein (1999) suggests that movement accounts for both raising and control, allowing PRO to be treated like an NP-trace, a byproduct of movement. The type of movement adopted by Hornstein (1999), labeled ‘sideward movement’, predicts that an NP argument (normally the subject) can move into multiple theta-positions. This is controversial because the standard view is that movement into theta-positions is prohibited under the Theta Criterion, which stipulates that every argument receives exactly one theta role. Besides, sideward movement involves moving an element across different syntactic domains, which violates the typical constraints on locality and movement in syntax, such as the phase impenetrability condition (Chomsky, 2001).

FC, as defined in Chomsky (2021) (see also Fong et al., 2023; Saito, 2024; Manzini & Roussou, 2024), revisits Hornstein’s (1999) movement-based analysis of control. Crucially, Chomsky (2021) introduces the Minimal Yield (MY) condition on Merge, which addresses the issues related to sideward movement. MY solves the locality issues by ensuring that each application of Internal or External Merge introduces at most one new accessible item to the syntactic workspace. This ensures that the complexity of the workspace does not increase unnecessarily, and it prevents multiple elements from becoming accessible in ways that would violate locality. Instead of movement, the subject in FC is externally merged in both the matrix clause and the embedded clause. However, these multiple occurrences are treated as copies of the same element, and one of the copies is deleted. This prohibits sideward movement, which inherently creates two new accessible items in separate domains. Crucially, only External Merge can introduce an element into a theta-position, which is a key departure from Hornstein’s theory. To distinguish two identical elements, FC assigns a ‘copy’ relation between the two. The lower copy is then deleted.

The concept of accessibility is particularly relevant in this context: according to Chomsky (2021), any syntactic element (such as a phrase or a constituent) that is available for further syntactic operations, such as movement, Merge, or other processes, within the current syntactic workspace, is defined as accessible. Accessibility is determined by structural locality and the constraints imposed by the Phase Impenetrability Condition (PIC) and Minimal Search. Essentially, an item is accessible if it is not within a phase that has been closed off, it is not within the c-command domain of the current workspace, and it is not blocked by intervening syntactic objects. MY ensures that Merge introduces only one new accessible item to the syntactic workspace at a time. For an item to be accessible, it must be in a c-command relationship with the target of the next operation. This means it should not be trapped inside a syntactic domain that is out of reach for further movement or operations. Translated into Phase Theory terms, once a phase is complete, only the edge of the phase (e.g., its specifier) remains accessible. The internal content of the phase becomes inaccessible for further operations. Thus, an accessible item under MY is defined as any syntactic element that can still be manipulated in subsequent derivations and is not blocked by locality or phase boundaries.

In the remainder of this section, I will show how FC captures the difference between the two types of how-complements in Serbian.

5.2.2. Form-Copy in This Study

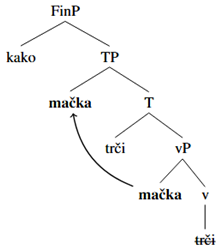

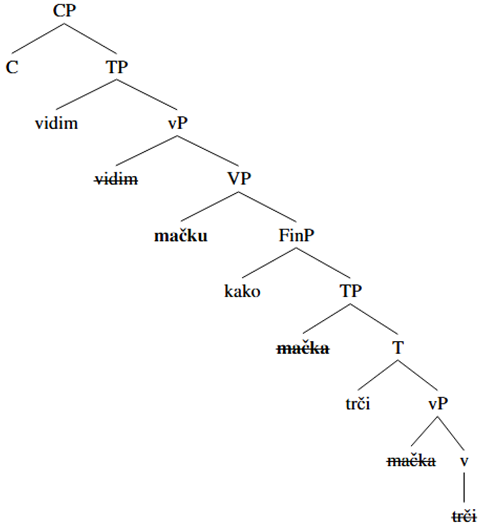

In line with the discussion in Section 5.2.1, in the case of eventive complements such as (1) (repeated here as 41), the NP mačka needs to be externally merged into different thematic positions (in line with Chomsky, 1981, 2021): the matrix VP complement and the embedded Spec-vP; the steps of the syntactic computation are described below.

In the embedded clause, the NP mačka moves to the embedded Spec-TP for agreement, leaving behind a lower copy in the thematic position Spec-vP (42):

| (41) | Vid-im | mačk-u | kako trč-i. |

| see-prs.1sg | cat-nom | how run-prs.3sg | |

| ‘I see the cat running.’ | |||

| (42) |  |

At this point, two identical copies of the same NP are found in the same syntactic domain (the kako-clause), and FC applies. The copy relation is assigned to the two occurrences of mačka in the embedded kako-clause, and the lower one is deleted (43):

| (43) |  |

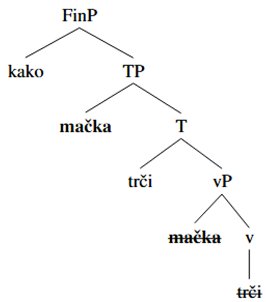

When the matrix VP is merged, an additional copy of the NP mačka is externally merged in the complement of V. Recall that there is no phase boundary between the matrix and embedded environment, as the embedded FinP does not represent a phase domain. Therefore, syntactic operations between the matrix and embedded environments remain available. Given the presence of two identical copies of the same NP in the matrix VP and the embedded Spec-TP, FC applies again, assigning the copy relation to the two NPs, deleting the lower copy in the embedded Spec-TP (44):

| (44) |  |

The FC relationship established in the tree in (44) deletes the lower copy of the NP in the kako-clause, yielding the eventive construction with an accusative-marked perceived NP in the matrix clause and a null subject in the complement itself; I argue that the lack of a phase boundary in (62) allows for FC to take place between the two locations in the matrix and embedded environments.

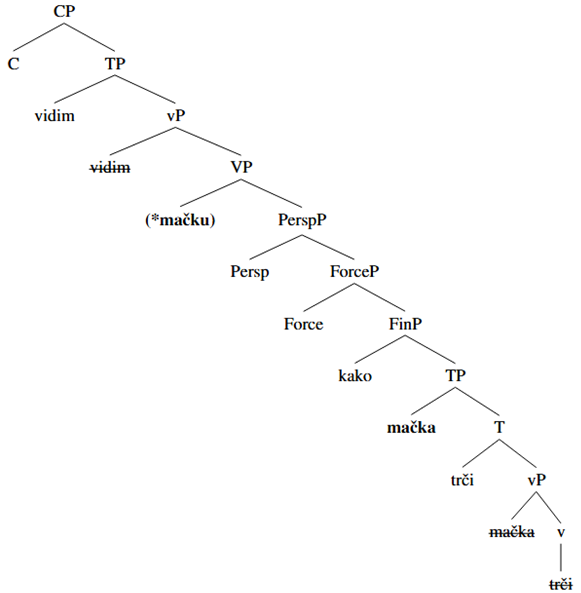

Conversely, a propositional clause (13) (repeated here as (45)) does not allow for FC to apply between the complement and matrix environment. As discussed at the beginning of Section 5.2, propositional complement clauses constitute phasal domains, with PerspP as their highest functional head. In Section 5.2.1, we established, building on Chomsky (2021) that FC applies locally, that is, it does not violate the PIC. As a consequence, FC is impossible in propositional complement clauses, as the copy relation cannot be established across phases. This is represented in (46):

| (45) | Vid-im | kako mačk-a | trč-i. |

| see-prs.1sg | how cat-nom | run-prs.3sg | |

| ‘I see the cat running.’ | |||

| (46) |  |

The embedded occurrence of the NP mačka is not accessible to Form-Copy because of the Phase Impenetrability Condition (Chomsky, 2021): the complement clause is sent to LF for interpretation, and the matrix object cannot see its embedded copy; the realization of an additional copy of the NP in the matrix clause would therefore result in ungrammaticality11. In conclusion, case assignment differs between the two kako-clause types due to structural and derivational asymmetries. In eventive clauses, the perceived NP appears in the accusative case as the complement of the matrix verb, and the embedded clause lacks an overt subject. According to the Form-Copy analysis (Chomsky, 2021), this NP is externally merged in both the matrix VP and the embedded clause, and a copy relation links the two positions. Because the kako-clause in this configuration does not constitute a phasal domain, the embedded subject remains accessible, allowing the matrix verb to assign accusative case to it via standard object-licensing mechanisms.

By contrast, in propositional kako-clauses, the embedded clause is a full CP phase that contains its own subject. The subject is introduced and licensed within the embedded clause by agreement with embedded T, receiving nominative case. Since the CP is a separate phase, the embedded subject is not accessible to the matrix verb for case assignment. The matrix verb thus treats the entire CP as a propositional object, and case is assigned internally in the embedded clause.

6. Conclusions

The corpus-based study presented in this paper showed that Serbian uses a variety of structures to translate English -ing forms. I focused on two types of complement clauses introduced by kako (‘how’). At the interpretive level, the Serbian kako-clauses are comparable to Romance pseudo-relatives, but they exhibit the typical behavior of complement clauses, rather than relatives.

I argued for a Minimalist syntactic analysis of Serbian kako-clauses and showed how Chomsky’s (2021) FC can be extended to a variety of clausal complements, to capture fine-grained distinctions such as the ones described for eventive and propositional clauses. The two type of clauses received parallel syntactic analyses, and the notion of phases and phase boundaries captured the formal differences existing between the two structures, as well as their distinct interpretation.

Funding

This research was supported by the Polish National Science Center (NCN) grant SONATA BIS-11 HS2 (2021/42/E/HS2/00143).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to the audiences of SinFonIJa 17, the Bielefeld-Leiden Comparative Syntax Conference 2025 and the Linguistic Meetings (University of Udine), to two anonymous reviewers and to the editors of this volume for their helpful and insightful comments. I would like to thank Željko Antić, Miroslav Mešanović and Marko Milenković for the discussion of the Serbian data. All remaining errors are my own.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Serbian is used here with specific reference to the corpus data employed in the paper, which is made up of Serbian translations of original English texts. I am aware that structures that parallel the ones discussed in the present work are more generally available in Bosnian/Croatian/Montenegrin/Serbian. Similarly, parallel structures are attested in numerous other Slavic languages. The possibility of extending the syntactic analysis proposed here to include all Slavic languages that allow for such structures is a matter of current investigation. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | For reasons of space, I will only gloss nominative and accusative cases in the example, as a way to distinguish the different types of kako-clauses I will present in the paper. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | The corpus is available at https://corpus.slavicus.uwr.edu.pl/. Last consulted on 6 May 2025. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | An anonymous reviewer raised the question of whether the da-clause is truly equivalent to the propositional kako-clause, particularly with respect to evidentiality and informativity. At this point, I have no evidence that the alternation between the two structures conveys such subtle semantic contrasts. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5 | An anonymous reviewer correctly pointed out that English -ing forms can tolerate negation under certain interpretations (e.g., I noticed Alex not touching the line). This observation suggests that some English speakers may use -ing forms to translate both eventive and propositional kako-clauses in Serbian. I preliminarily propose that negation is permitted (in English and Serbian alike) in contexts that are not clearly eventive. A more detailed investigation of the semantic role of negation in such clauses is left for future research. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6 | The comparison with French pseudo-relatives is intended as a diagnostic rather than a genetic or areal parallel. These constructions offer well-documented syntactic tests (e.g., clitic antecedents, movement, stativity restrictions) that help clarify the structural nature of Serbian eventive kako-clauses. Further cross-Balkan comparison, especially with Romanian how-clauses (as suggested by an anonymous reviewer), is an important direction for future research. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7 | Notice, however, that French uses the same relative pronoun qui in relative and pseudo-relative constructions, making the exact nature of (31) more ambiguous. An anonymous reviewer suggested that we should be able to disambiguate between relatives and pseudo-relatives in French by using a clitic antecedent, which is possible only with pseudo-relatives. Indeed, by replacing the antecedent Anne in (31) with the clitic l’, the permanent state becomes impossible:

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8 | I will not discuss the realization of TopP and FocP here, as their role is irrelevant in the definition of phasal domains. The present account allows for dislocated constituents to be realized above FinP in eventive and propositional clauses alike. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 9 | In this respect, my proposal diverges from Wurmbrand and et al. 2020 analysis, where eventive complements maximally merge vP. However, both models agree that eventive complements lack full structural complexity compared to propositional clauses, which may allow the two perspectives to be partially reconciled. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10 | The literature on FC, starting from Chomsky (2021), discusses cases of obligatory control, but does not directly address the distinction between partial and exhaustive control. Kako-clauses represent a special case in that the partial control interpretation is always excluded, eliminating the problems posed by them for the FC approach. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 11 | While the present work focuses only on how-complements, I preliminarily propose that the structure in (46) could also be applied to the example in (11), which features a da-complement clause with an overt subject NP. I leave this topic for future research. While, to my knowledge, there is no literature directly comparing the syntactic structure of pseudo-relative and complement clauses, a discussion of structural identity between complement and relative clauses is presented in Arsenijević (2009). | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- Alexiadou, A., Wilder, C., Meinunger, A., & Law, P. (2000). Introduction. In A. Alexiadou, C. Wilder, A. Meinunger, & P. Law (Eds.), The syntax of relative clauses (pp. 1–52). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Anand, P., & Nevins, A. (2004). Shifty operators in changing contexts. Proceedings of SALT, 14, 20–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsenijević, B. (2009). Clausal complementation as relativization. Lingua, 119(1), 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asudeh, A., & Toivonen, I. (2012). Copy raising and perception. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory, 30(2), 321–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barwise, J. (1981). Scenes and other situations. The Journal of Philosophy, 78, 369–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, W. (1986). Relativna rečenica u hrvatskom ili srpskom jeziku u poređenju s engleskom situacijom [Relative clauses in Serbo-Croatian in comparison with English] [Ph.D. thesis, Zagreb University]. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Burzio, L. (1986). Italian syntax. A government-binding approach. Reidel. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Casalicchio, J. (2013). Pseudorelative, gerundi e infiniti nelle varietà romanze: Affinità (solo) superficiali e corrispondenze strutturali [Ph.D. thesis, University of Padova]. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Casalicchio, J. (2021). Expressing perception in parallel ways: Sentential small clauses in German and Romance. In S. Wolfe, & C. Meklenborg (Eds.), Continuity and variation in Germanic and Romance (pp. 70–96). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Chomsky, N. (1981). Lectures on government and binding. Foris Publications. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Chomsky, N. (2001). Derivation by phase. In M. Kenstowicz (Ed.), Ken hale: A life in language (pp. 1–52). MIT Press. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Chomsky, N. (2021). Minimalism: Where are we now, and where can we hope to go. Gengo Kenkyu (Journal of the Linguistic Society of Japan), 160, 1–41. [Google Scholar]

- Cinque, G. (1992). The pseudo-relative and acc-ing constructions after verbs of perception. Working Papers in Linguistics–University of Venice, 2, 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Corver, N. (2023). Decomposing adverbs and complementizers: A case study of Dutch hoe ‘how’. In Ł. Jędrzejowski, & C. Umbach (Eds.), Non-interrogative subordinate wh-clauses (pp. 158–206). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Fong, S., Ginsburg, J., Matsumoto, M., & Terada, H. (2023). The strong minimalist thesis (SMT): Form copy (FC) and the serial verb construction (SVC). Japanese/Korean Linguistics, 30, 411–421. [Google Scholar]

- Gračanin-Yuksek, M. (2013). The syntax of relative clauses in Croatian. The Linguistic Review, 30(1), 25–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guasti, M. T. (1988). La pseudorelative et les phénomènes d’accord. Rivista di Grammatica Generativa, 13, 35–57. [Google Scholar]

- Hornstein, N. (1999). Movement and control. Linguistic Inquiry, 30(1), 69–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayne, R. (1975). French syntax: The transformational cycle. MIT Press. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Kayne, R. (1994). The antisymmetry of syntax. MIT Press. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Kordić, S. (1995). Relativna rečenica [The relative clause]. Matica Hrvatska. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Krapova, I. (2010). Bulgarian relative and factive clauses with an invariant complementizer. Lingua, 120(5), 1240–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landau, I. (2013). Control in generative grammar: A research companion. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Manzini, M. R., & Roussou, A. (2024). Italian and Arberesh (Albanian) causatives: Case and agree. Isogloss Open Journal of Romance Linguistics, 10(4), 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Radford, A. (1975). Pseudo-relatives and the unity of subject raising. Archivum Linguisticum, 6, 32–64. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzi, L. (1997). The fine structure of the left periphery. In L. Haegeman (Ed.), Elements of grammar (pp. 281–337). Kluwer. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Rozwadowska, B., Frasson, A., Klimek-Jankowska, D., Shlikhutka, N., & Wągiel, M. (2025). Slavicus corpus. Available online: https://corpus.slavicus.uwr.edu.pl/ (accessed on 6 May 2025).[Green Version]

- Saito, M. (2024). On minimal yield and form copy: Evidence from East Asian languages. The Linguistic Review, 41(1), 59–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speas, P., & Tenny, C. (2003). Configurational properties of point of view roles. Asymmetry in Grammar, 1, 315–344. [Google Scholar]

- Sundaresan, S. (2012). Context and (Co) reference [Ph.D. thesis, University of Stuttgart]. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Šimík, R., & Sláma, J. (2023). Czech evidential relatives introduced by jak ‘how’: Recognitional cues for the hearer. In Ł. Jędrzejowski, & C. Umbach (Eds.), Non-interrogative subordinate wh-clauses (pp. 239–273). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Wurmbrand, S., Kovač, I., Lohninger, M., Pajančič, C., & Todorović, N. (2020). Finiteness in South Slavic complement clauses: Evidence for an implicational finiteness universal. Linguistica, 60(1), 119–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).