Abstract

This study investigates the syntactic structure of negative particle questions (NPQs), also known as VP-NEG questions, in Sixian Hakka (a variety of Chinese spoken in Taiwan). We revisit the existing literature on Hakka NPQs, pointing out unresolved issues in previous analyses. Drawing on previous analysis of VP-NEG questions in Middle Chinese, we argue that the negator mo in Hakka NPQs has grammaticalized into a disjunctive head, as mo and the predicate do not show agreement. This proposal not only accounts for the syntactic properties of NPQs in Sixian Hakka but also addresses potential problems found in previous studies.

1. Introduction

The term ‘negative particle question (NPQ)’ was first used in L. L.-S. Cheng et al. (1996) to refer to the questions formed with a sentence-final negation marker, as shown in (1), an example of an NPQ in Mandarin Chinese.

This construction is also attested in other varieties of Chinese (such as Cantonese, Southern Min, and Hakka) as well as in Southeast Asian languages (such as Khmer, Thai, and Vietnamese) (see L. L.-S. Cheng et al., 1996, 1997; Y.-J. J. Hsieh, 2013; Duffield, 2013; Liao & Lin, 2024; among many others).

| (1) | Hufei | kan-wan-le | nei-ben | shu | meiyou?1 |

| Hufei | read-finish-ASP | that-CL | book | not-have | |

| ‘Did Hufei finish reading that book?’ (L. L.-S. Cheng et al., 1997, p. 65) | |||||

In this work, we focus on NPQs in Sixian Hakka, specifically, on VP-mo questions.2 Mo ‘not have’ in Sixian Hakka is an existential negator; it can appear before a nominal or a verb phrase, as shown in (2).3 In addition, it can also occur in the sentence-final position and function like a question particle, as illustrated in (3).

| (2) | a. | Amin | mo | qien. | |||||||

| Amin | not.have | money | |||||||||

| ‘Amin doesn’t have money.’ | |||||||||||

| b. | Amin | mo | oi | hi | hog-gau. | ||||||

| Amin | not.have | want | go | school | |||||||

| ‘Amin doesn’t want to go to school.’ | |||||||||||

| (3) | Amin | oi | hi | hog-gau | mo? | ||||||

| Amin | want | go | school | not.have | |||||||

| ‘Does Amin want to go to school?’ | |||||||||||

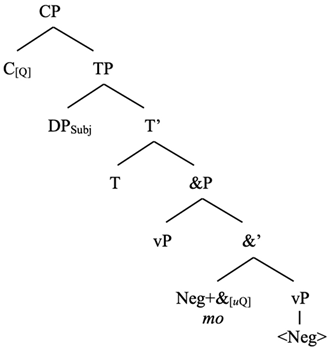

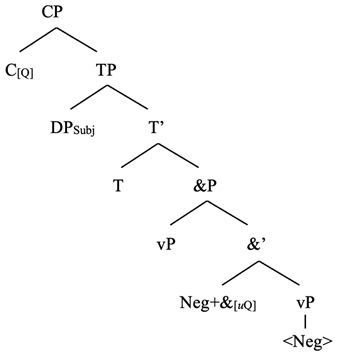

Inspired by Aldridge’s (2011) analysis of VP-NEG questions in Middle Chinese, we propose that VP-mo questions in Sixian Hakka exhibit a disjunctive question structure, as shown in (4). We argue that the negator mo in Hakka NPQs originally headed the second vP in the disjunctive phrase and has grammaticalized into a disjunctive head.

This proposal is based on the similarities between VP-mo questions in Sixian Hakka and earlier VP-fou questions in Middle Chinese. Moreover, the proposed analysis accounts for the phenomena observed in VP-mo questions, including their incompatibility with negative predicates and lack of agreement between mo and the predicates.

| (4) |  |

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows: In Section 2, we review the literature on VP-mo questions, including R.-F. Chung (2000) and Y.-J. J. Hsieh (2013), and point out some unresolved problems. In Section 3, we introduce two possible approaches to NPQs. Section 4 presents our proposal and illustrates how it accounts for the VP-mo questions in Sixian Hakka. Section 5 is the conclusion.

2. Previous Literature on VP-mo Questions

NPQs in Sixian Hakka have not received as much attention as NPQs in other languages (L. L.-S. Cheng et al., 1996, 1997; M.-L. Hsieh, 2001; Li, 2006; R.-H. Huang, 2008; among many others). The relevant literature on VP-mo questions that we have found includes R.-F. Chung (2000) and Y.-J. J. Hsieh (2013), which we review below.

R.-F. Chung (2000) provides a preliminary introduction to interrogative questions in Sixian Hakka, classifying VP-mo questions as particle questions formed with a sentence-final particle mo.4 Although Chung 2000 does not offer a syntactic analysis of VP-mo questions, he presents a set of examples that deserves our attention, as shown in (5). Chung suggests that a disjunctive question in Sixian Hakka (as in (5a)) can be reduced to a VP-mo question (as in (5c)).5

Although the exact process of deletion is not specified in R.-F. Chung (2000), we assume this is what the author means: if the verb phrase following the negator mo in (5a) is deleted, the sentence becomes (5b); if the disjunctive head ia ‘or’ is subsequently removed from (5b), the result is (5c). However, this assumption encounters some issues. First, another set of examples provided by Chung in his work, as shown in (6), would cast doubt on a deletion analysis; it is unclear how examples (6a–b) transform into (6c), as the negator mo ‘not have’ does not appear in either (6a) or (6b) in the first place.

Second, some VP-mo questions cannot be reconstructed, as shown in (7) and (8). If VP-mo questions were derived from disjunctive questions through deletion, it is puzzling as to why they cannot be reconstructed into disjunctive questions.

| (5) | a. | Gi | iu | da | tien-fa | go-loi | ia | mo |

| he | have | call | phone | come | or | not.have | ||

| da | tien-fa | go-loi? | ||||||

| call | phone | come | ||||||

| ‘Did he call or did he not call?’ | ||||||||

| b. | Gi | iu | da | tien-fa | go-loi | ia | mo? | |

| he | have | call | phone | come | or | not.have | ||

| ‘Did he call or not?’ | ||||||||

| c. | Gi | iu | da | tien-fa | go-loi | mo? | ||

| he | have | call | phone | come | not.have | |||

| ‘Did he call?’ (R.-F. Chung, 2000, p. 160; glosses and translation ours) | ||||||||

| (6) | a. | Ng | oi | ten | ngai | siid fu | ia | m | ten | ngai | siid fu? |

| you | want | with | I | suffer | or | not | with | I | suffer | ||

| ‘Do you like to suffer with me or do you not like to suffer with me?’ | |||||||||||

| b. | Ng | oi | ten | ngai | siid fu | ia | m? | ||||

| you | want | with | I | suffer | or | not | |||||

| ‘Do you like to suffer with me or not?’ | |||||||||||

| c. | Ng | oi | ten | ngai | siid fu | mo? | |||||

| you | want | with | I | suffer | not.have | ||||||

| ‘Do you like to suffer with me?’ (R.-F. Chung, 2000, p. 159; glosses and translation ours) | |||||||||||

| (7) | a. | Gi | zo-ded | hi | hog-gau | mo? | |||

| he | can | go | school | not.have | |||||

| ‘Can he go to school?’ | |||||||||

| b. | *Gi | zo-ded | hi | hog-gau | ia | mo? | |||

| he | can | go | school | or | not.have | ||||

| c. | *Gi | zo-ded | hi | hog-gau | ia | mo | zo-ded | hi | |

| he | can | go | school | or | not.have | can | go | ||

| hog-gau? | |||||||||

| school | |||||||||

| (8) | a. | Gi | voi | hi | hog-gau | mo? | ||||

| he | will | go | school | not.have | ||||||

| ‘Will he go to school?’ | ||||||||||

| b. | *Gi | voi | hi | hog-gau | ia | mo? | ||||

| he | will | go | school | or | not.have | |||||

| c. | *Gi | voi | hi | hog-gau | ia | mo | voi | hi | hog-gau? | |

| he | will | go | school | or | not.have | will | go | school | ||

Now, let us turn to Y.-J. J. Hsieh (2013), which provides an early syntactic analysis of NPQs in Sixian Hakka. Hsieh points out the similarities between NPQs in Sixian Hakka and A-not-A questions in Mandarin, arguing that VP-mo questions in Sixian Hakka are a type of A-not-A question. An A-not-A question is a special type of question in Mandarin and other varieties of Chinese language characterized by the combination of both the affirmative form (A) and the negative form (not-A), as illustrated in (9).6 In (9), chi ‘eat’ represents A and bu chi ‘not eat’ represents not-A.

Hsieh presents several similarities between NPQs in Sixian Hakka and A-not-A questions in Mandarin. First, neither A-not-A questions nor VP-mo questions can be answered with a simple positive/negative particle (i.e., yes or no), as shown in (10) and (11).

Second, A-not-A questions and VP-mo questions are compatible with the adverb daodi ‘on earth; truly,’ which corresponds to dodi in Sixian Hakka; they are incompatible with the adverb nandao ‘actually,’ which corresponds to mosheng in Sixian Hakka. See (12) and (13).

Third, it is possible to add a specialized sentence-final particle to both types of questions: Mandarin ne in (14) and Hakka no in (15), which might be roughly paraphrased into ‘so,’ function as attitudinal markers expressing the speaker’s concern about the situation being inquired into and/or their interest in the addressees’ responses to questions (cf. Paul, 2014; Pan, 2015; J.-M. Cheng, 2007; Fan, 2025).

Fourth, the A in A-not-A questions and the VP in VP-NEG questions can be a verb, an adjective, a modal, an adverb, or a preposition, as shown in (16) and (17).

Fifth, both types of questions are non-biased. In a context where the speaker notices that his grandmother is very nice to a girl and suspects that she likes the girl, the speaker cannot use A-not-A questions (18a) or VP-mo questions (19a) to ask for confirmation.7

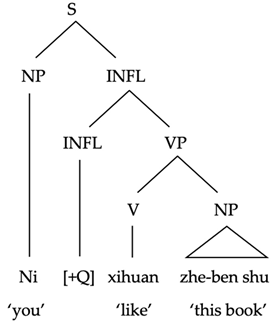

Based on these similarities, Hsieh argues that VP-mo questions are a type of A-not-A question and proposes an analysis inspired by C.-T. J. Huang’s (1991) analysis of A-not-A questions. C.-T. J. Huang (1991) proposes that A-not-A questions in Mandarin have an abstract Q under the INFL position, as illustrated in (20).8 The abstract Q is realized by a process of reduplication and the insertion of negation (bu ‘not’ in (20)).

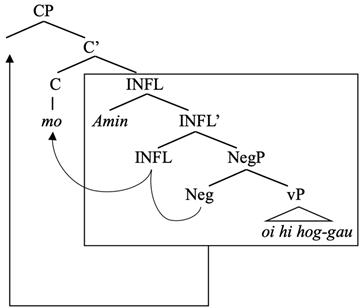

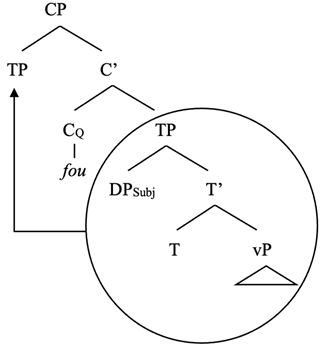

Drawing on C.-T. J. Huang’s (1991) analysis, Hsieh 2013 proposes that the sentence-final mo is an overt realization of the interrogative INFL. Hsieh argues that the negator mo is base-generated in Neg0, and then raises to INFL, and subsequently to C0 to form a question. The surface order of the NPQ is then derived after the remnant TP raises to Spec, CP, as illustrated in (21).

This analysis explains why a negative predicate is not allowed in VP-NEG questions, as shown in (22). It is argued that, because the sentence-final mo moves out of the predicate from the position of Neg0, an additional negator is not allowed within the same predicate.

| (9) | Ni | chi | bu | chi | niurou? |

| you | eat | not | eat | beef | |

| ‘Do you eat beef?’ | |||||

| (10) | Mandarin A-not-A questions: | |||||||||

| A: | Xiaoming | ai | bu | ai | chi | qiao-ke-li? | ||||

| Xiaoming | love | not | love | eat | chocolate | |||||

| ‘Does Xiaoming love to eat chocolate?’ | ||||||||||

| B: | Ai | / | Bu-ai | / | *Shi | / | *Bu-shi | / | *Dui. | |

| love | not-love | yes | no | correct | ||||||

| ‘Yes, Xiaoming does./No, Xiaoming does not.’ (Y.-J. J. Hsieh, 2013, pp. 27–28) | ||||||||||

| (11) | Hakka VP-mo questions: | |||||||||

| A: | Gi | voi | hi | hoggau | mo? | |||||

| he | will | go | school | not.have | ||||||

| ‘Will he go to school?’ | ||||||||||

| B: | Voi | / | M-voi | / | *He | / | *M-he | / | *Dui. | |

| will | not-will | yes | no | correct | ||||||

| ‘’Yes, he will./No, he will not.’ (Y.-J. J. Hsieh, 2013, p. 28) | ||||||||||

| (12) | Mandarin A-not-A questions: | |||||||||

| Ta | daodi | / *nandao | yao | bu | yao | lai | gen | women | chi | |

| he | truly | actually | want | not | want | come | with | us | eat | |

| wancan? | ||||||||||

| dinner | ||||||||||

| ‘Is he coming to eat with us or not?’ (Y.-J. J. Hsieh, 2013, p. 28) | ||||||||||

| (13) | Hakka VP-mo questions: | ||||||

| Gi | dodi | / *mosheng | voi | hi | hog-gau | mo? | |

| he | truly | actually | will | go | school | not.have | |

| ‘Is he going to the school or not?’ (Y.-J. J. Hsieh, 2013, p. 29) | |||||||

| (14) | Mandarin A-not-A questions: | ||||||

| Ni | xihuan | bu | xihuan | zhe-ge | nu-sheng | ne? | |

| you | like | not | like | this-CL | girl | PRT | |

| ‘So, do you like this girl?’ (Y.-J. J. Hsieh, 2013, p. 29, quoted with miner modification) | |||||||

| (15) | Hakka VP-mo questions: | |||||

| Gi | zung-i | ia-ge | se-moi-e | mo | no? | |

| he | like | this-CL | girl | not.have | PRT | |

| ‘So, do you like this girl?’ (Y.-J. J. Hsieh, 2013, p. 30, quoted with miner modification) | ||||||

| (16) | Mandarin A-not-A questions: | |||||||

| a. | Ni | he | bu | he | jiu? | [verb] | ||

| you | drink | not | drink | wine | ||||

| ‘Do you drink?’ (Y.-J. J. Hsieh, 2013, p. 30) | ||||||||

| b. | Zhe-ge | nu-sheng | piao-liang | bu | piao-liang? | [adjective] | ||

| this-CL | girl | beautiful | not | beautiful | ||||

| ‘Is this girl beautiful?’ (Y.-J. J. Hsieh, 2013, p. 31) | ||||||||

| c. | Ta | neng | bu | neng | he | jiu? | [modal] | |

| he | can | not | can | drink | wine | |||

| ‘Can he drink wine?’ (Y.-J. J. Hsieh, 2013, p. 31) | ||||||||

| d. | Ta | chang | bu | chang | mai | yifu? | [adverb] | |

| she | often | not | often | buy | clothes | |||

| ‘Does she often buy new clothes?’ (Y.-J. J. Hsieh, 2013, p. 32) | ||||||||

| e. | Ta | jin-tian | zai | bu | zai | jia? | [preposition] | |

| he | today | at | not | at | home | |||

| ‘Is he at home today?’ (Y.-J. J. Hsieh, 2013, p. 32) | ||||||||

| (17) | Hakka VP-mo questions: | ||||||

| a. | Ngi | siid | jiu | mo? | [verb] | ||

| you | drink | wine | not.have | ||||

| ‘Do you drink?’ (Y.-J. J. Hsieh, 2013, p. 31) | |||||||

| b. | Ia-ge | se-moi-e | jiang | mo? | [adjective] | ||

| this-CL | girl | beautiful | not.have | ||||

| ‘Is this girl beautiful?’ (Y.-J. J. Hsieh, 2013, p. 31) | |||||||

| c. | Gi | zo-ded | siid | jiu | mo? | [modal] | |

| he | can | drink | wine | not.have | |||

| ‘Can he drink wine?’ (Y.-J. J. Hsieh, 2013, p. 31) | |||||||

| d. | Gi | jiab | mai | sam-fu | mo? | [adverb] | |

| she | often | buy | clothes | not.have | |||

| ‘Does she often buy new clothes?’ (Y.-J. J. Hsieh, 2013, p. 32) | |||||||

| e. | Gi | gim-bu-ngid | ti | vug-ka | mo? | [preposition] | |

| he | today | at | home | not.have | |||

| ‘Is he at home today?’ (Y.-J. J. Hsieh, 2013, p. 32) | |||||||

| (18) | Mandarin A-not-A questions: | ||||||

| a. | #Nainai | xihuan | bu | xihuan | zhe-ge | nu-sheng? | |

| grandma | like | not | like | this-CL | girl | ||

| ‘Does grandma like this girl?’ | |||||||

| b. | Nainai | xihuan | zhe-ge | nu-sheng | hou? | ||

| grandma | like | this-CL | girl | PRT | |||

| ‘Grandma likes this girl, right?’ | |||||||

| (19) | Hakka VP-mo questions: | |||||

| a. | #Apo | zhong-i | ya-ge | se-moi-e | mo? | |

| grandma | like | this-CL | girl | not.have | ||

| ‘Does grandma like this girl?’ (Y.-J. J. Hsieh, 2013, p. 33) | ||||||

| b. | Apo | zhong-i | ya-ge | se-moi-e | ho? | |

| grandma | like | this-CL | girl | PRT | ||

| ‘Grandma likes this girl, right?’ (Y.-J. J. Hsieh, 2013, p. 33) | ||||||

| (20) | a. | Ni | xihuan | bu | xihuan | zhe-ben | shu? | |

| you | like | not | like | this-CL | book | |||

| ‘Do you like this book?’ | ||||||||

| b. |  | (C.-T. J. Huang, 1991, p. 316) | ||||||

| (21) | a. | Amin | oi | hi | hog-gau | mo? |

| Amin | want | go | school | not.have | ||

| ‘Does Amin want to go to school?’ | ||||||

| b. |  | |||||

| (22) | *Apo | m | zhong-i | ya-ge | se-moi-e | mo? |

| grandma | not | like | this-CL | girl | not.have | |

| Intended reading: ‘Doesn’t grandma like this girl?’ (Y.-J. J. Hsieh, 2013, p. 56) | ||||||

However, this analysis has its own weakness. If the negator mo is base-generated in Neg0, its reconstruction would be expected to be acceptable. However, mo in the example sentences in (23) cannot be placed in the preverbal position, as shown in (24). This indicates that it is unlikely that the sentence-final mo in NPQs is base-generated in the head of NegP in a preverbal position.

The negator mo is not compatible with the predicates in (24), namely zo-ded ‘can,’ voi ‘will,’ and iu ‘have.’ To negate zo-ded ‘can,’ one must say zo-m-ded ‘cannot,’ inserting the negator m ‘not’ between zo and ded. To negate the modal verb voi ‘will,’ the negator m ‘not’ must be used instead of mo. To express the negation of iu ‘have,’ mo ‘not have’ as the negated counterpart of iu is used instead. In other words, there is no agreement between these verbs and the negator mo, which is not considered in Hsieh’s Neg-to-C movement approach. If the sentence-final mo is not base-generated in the head of NegP within the predicate, its exact syntactic position remains unclear. In the next section, we introduce two alternative analyses of NPQs from other languages and examine whether they can be applied to VP-mo questions in Sixian Hakka.

| (23) | a. | Amin | zo-ded | hi | hog-gau | mo? |

| Amin | can | go | school | not.have | ||

| ‘Can Amin go to school?’ | ||||||

| b. | Amin | voi | hi | hog-gau | mo? | |

| Amin | will | go | school | not.have | ||

| ‘Will Amin go to school?’ | ||||||

| c. | Amin | iu | hi | hog-gau | mo? | |

| Amin | have | go | school | not.have | ||

| ‘Did Amin go to school?’ | ||||||

| (24) | a. | *Amin | mo | zo-ded | hi | hog-gau. |

| Amin | not.have | can | go | school | ||

| Intended reading: ‘Amin cannot go to school.’ | ||||||

| b. | *Amin | mo | voi | hi | hog-gau. | |

| Amin | not.have | will | go | school | ||

| Intended reading: ‘Amin will not go to school.’ | ||||||

| c. | *Amin | mo | iu | hi | hog-gau. | |

| Amin | not.have | have | go | school | ||

| Intended reading: ‘Amin did not go to school.’ | ||||||

3. Two Analyses of NPQs in Other Languages

3.1. Agreement Languages and Non-agreement Languages

L. L.-S. Cheng et al. (1997) discuss NPQs in Mandarin, Cantonese, and Taiwan Southern Min. They point out that different languages adopt different strategies for forming NPQs. Languages that exhibit agreement patterns are classified as agreement languages, while those without such patterns are classified as non-agreement languages. In agreement languages such as Mandarin, aspect markers and verb types that are compatible with the negator also remain compatible when the negator appears in the sentence-final position as a negative particle in NPQs, as shown in (25) and (26). The negator meiyou ‘not have’ is compatible with the aspect marker guo but incompatible with the modal verb hui ‘will,’ as exemplified in (25). These agreement patterns are maintained when the negator meiyou appears in the sentence-final position to form an NPQ, as shown in (26).9

In non-agreement languages such as Cantonese and Taiwan Southern Min, agreement between negation and an aspect or verb is not maintained. Cantonese examples are given below. The negator mei ‘not have’ in Cantonese is incompatible with the modal verb hoyi ‘can’ and the perfective aspect marker zo. However, in NPQs, the sentence-final particle mei is compatible with both.

L. L.-S. Cheng et al. (1997) further argue that NPQs in agreement languages, such as Mandarin, involve Neg-to-C movement, while those in non-agreement languages, such as Cantonese and Taiwan Southern Min, do not. In the latter case, the sentence-final negative particle is base-generated in C0.

| (25) | a. | Hufei | meiyou | qu-guo. | |

| Hufei | not.have | go-EXP | |||

| ‘Hufei has not been (there).’ | |||||

| b. | *Hufei | meiyou | hui | qu. | |

| Hufei | not.have | will | go | ||

| Intended reading: ‘Hufei will not go.’ (L. L.-S. Cheng et al., 1997, p. 67) | |||||

| (26) | a. | Ta | qu-guo | meiyou? | |

| he | go-EXP | not.have | |||

| ‘Has he been there?’ | |||||

| b | *Ta | hui | qu | meiyou? | |

| he | will | go | not.have | ||

| Intended reading: ‘Will he go?’ (L. L.-S. Cheng et al., 1997, p. 74) | |||||

| (27) | a. | *Keoi | mei | hoyi | lei. |

| he | not.have | can | come | ||

| Intended reading: ‘He will not come.’ | |||||

| b. | *Keoi | mei | lei-zo. | ||

| he | not.have | come-PERF | |||

| Intended reading: ‘He has not come yet.’ (L. L.-S. Cheng et al., 1997, p. 69) | |||||

| (28) | a. | Ngo | hoyi | ceot-heoi | mei? |

| I | can | go.out | not.have | ||

| ‘Can I go out?’ | |||||

| b. | Keoi | sik-zo | fan | mei? | |

| he | eat-PERF | rice | not.have | ||

| ‘Has he eaten?’ (L. L.-S. Cheng et al., 1997, p. 75) | |||||

According to L. L.-S. Cheng et al.’s (1997) classification, Sixian Hakka should be categorized as a non-agreement language, because agreement between verbs and negation is not maintained in NPQs, as shown in (23) and (24). If this analysis is on the right track, mo in VP-mo questions would be base-generated in the C0 position. In that case, the negative predicates should be compatible with mo. However, this is not borne out. VP-mo questions do not allow negative predicates, as evidenced by (22).

So far, neither the Neg-to-C movement approach nor the base-generation approach for non-agreement languages can fully account for Hakka VP-mo questions. This raises the question of whether a third type exists—distinct from both agreement and non-agreement languages. We now turn to Aldridge’s account of NPQs in Middle Chinese to explore whether a historical perspective might offer a possible solution.

3.2. Analysis of VP-NEG Questions in Middle Chinese

Aldridge (2011) examines VP-NEG questions observed in Middle Chinese, especially VP-wu and VP-fou questions. See (29) for some examples, where the negators wu ‘not have’ and fou ‘not be’ can appear in the sentence-final position and function similarly to a question particle.

| (29) | a. | 秋 | 寒 | 有 | 酒 | 無? | ||

| Qiu | han | you | jiu | wu? | ||||

| autumn | cold | have | liquor | not.have | ||||

| ‘In the autumn cold, is there any liquor?’ | ||||||||

| (Bai Juyi, 9th c., from Aldridge, 2011, p. 2) | ||||||||

| b. | 尊 | 者 | 能 | 食 | 粗 | 惡 | 食 | |

| Zun | zhe | neng | shi | cu | e | shi | ||

| respect | DET | can | eat | coarse | bad | food | ||

| 不? | ||||||||

| fou? | ||||||||

| not.be | ||||||||

| ‘Oh great one, can you eat inferior food?’ | ||||||||

| (Zabao Zangjing 50, ca. 5th c., from Aldridge, 2011, p. 9) | ||||||||

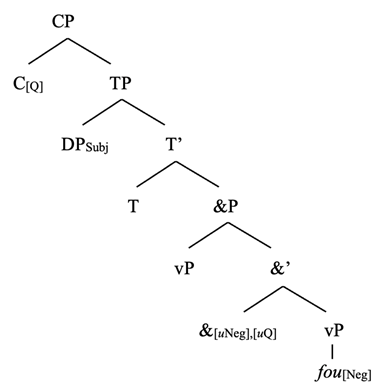

Aldridge 2011 investigates the syntactic structure of VP-NEG questions in Middle Chinese and proposes a reanalysis process (i.e., a grammaticalization path) of the negators into a Q element. The analysis of VP-fou questions in Middle Chinese is illustrated in (30). It is proposed that VP-fou questions in the earlier stage (before the 5th century) involve a disjunctive construction composed of a positive predicate and a negative predicate. The head of the disjunctive phrase (&P) bears two uninterpretable features, [uNeg] and [uQ].

| (30) |  | (Aldridge, 2011, p. 4) |

Aldridge argues that at this stage, fou was part of the vP complement of &P before raising to attach to & in a head-to-head manner. The [uNeg] feature is valued after fou moves to &; the [uQ] feature on the disjunctive head is valued through an Agree relation with the [Q] feature on C. See (31).

At this stage, fou was still undergoing grammaticalization and had not been fully grammaticalized into a question marker. The supporting facts are as follows: Negative predicates occurring before sentence-final fou are not attested, which may suggest that fou was base-generated in a position inherently endowed with [Neg] feature. However, the lack of agreement between predicates and fou supports the idea that fou occupied C0. For instance, the predicate headed by you ‘have,’ which cannot be negated by fou, can still be followed by sentence-final fou. Thus, Aldridge suggests that fou at this time was still base-generated in a lower position.

| (31) |  | (Aldridge, 2011, p. 17) |

When fou moved to &, it acquired the feature [uQ], and fou was eventually grammaticalized to be base-generated as the head of CP (or ForceP in the sense of Rizzi, 1997). By the 5th century, the grammaticalization of fou ‘not be’ was complete, with fou functioning as a full-fledged Q particle base-generated in C, as we illustrate in (32). The complement of CP then moves to Spec, CP, deriving the surface order.

This argument is based on the following observations: First, fou could occur with a wide range of predicates. Fou and the predicates do not need to show agreement. Second, fou is compatible with a negative predicate, which indicates that it cannot be base-generated in a position endowed with the [Neg] feature. See (33).

| (32) |  |

| (33) | 無 | 諸 | 惡 | 不? |

| Wu | zhu | e | fou? | |

| not.have | DET.PL | evil | not.be | |

| ‘Are (you) free of the various irritations?’ | ||||

| (Zabao Zangjing 73, ca. 5th c., from Aldridge, 2011, p. 9) | ||||

The analysis of VP-fou questions across different stages provides us with a new perspective on VP-mo questions in Sixian Hakka, especially regarding the role of grammaticalization, which is often overlooked in syntactic research. In the next section, we present our analysis by adopting Aldridge’s disjunctive approach to VP-mo questions and provide supporting evidence.

4. Proposal

Drawing inspiration from Aldridge’s 2011 disjunctive analysis of VP-fou questions in Middle Chinese, we propose that VP-mo questions in Sixian Hakka share a similar structure with earlier VP-fou questions, as shown in (34). The disjunctive phrase &P has two uninterpretable features: [uNeg] and [uQ].

We propose that the negator mo in Sixian Hakka originally headed the second vP of a disjunctive construction and would move to the head of a disjunctive phrase to value the feature [uNeg]. Through grammaticalization, mo has become the head of the disjunctive phrase, but it has not further grammaticalized into a question particle base-generated in C.10 The feature [uQ] is valued through an Agree relation with the [Q] feature on C. In addition, following Aldridge’s (2011) analysis of VP-NEG questions, we assume that the VP-mo questions in Sixian Hakka are derived by deletion of the second VP in the disjunctive construction and stranding of the negator in v.

| (34) | a. | Amin | oi | hi | hog-gau | mo? |

| Amin | want | go | school | not.have | ||

| ‘Does Amin want to go to school?’ | ||||||

| b. |  | |||||

This proposal is supported by the following facts: First, VP-mo questions, similarly to earlier-stage VP-fou questions, cannot occur with negative predicates; see (35). They also show a lack of agreement between the negator and predicates; see (36).

In addition, mo ‘not have’ can stand alone, as shown in (37). This suggests that mo functions as a head rather than an adjunct in syntactic terms, and is capable of undergoing head movement. This is quite similar to the status of fou in Middle Chinese, as exemplified in (38).

Moreover, mo in VP-mo questions does not further move to C0, in contrast to fou in VP-fou questions at a later stage of its diachronic development. Notably, VP-mo questions can be embedded—unlike questions with the Q-particle ma in Mandarin, in which the sentence-final particle ma occupies Force0 (Paul, 2014; Pan, 2015, 2019).

| (35) | a. | *Apo | m-zung-i | ya-ge | se-moi-e | mo? |

| grandma | not-like | this-CL | girl | not.have | ||

| Intended reading: ‘Doesn’t grandma like this girl?’ (Y.-J. J. Hsieh, 2013, p. 56) | ||||||

| b. | *Amin | mo | hi | hog-gau | mo? | |

| Amin | not.have | go | school | not.have | ||

| Intended reading: ‘Didn’t Amin go to school?’ | ||||||

| (36) | a. | Amin | zo-ded | / | voi | / | iu | hi | hog-gau | mo? |

| Amin | can | will | have | go | school | not.have | ||||

| ‘Can/Will/Did Amin go to school?’ | ||||||||||

| b. | *Amin | zo-ded | / | voi | / | iu | hi | hog-gau | ia | |

| Amin | can | will | have | go | school | or | ||||

| mo | zo-ded | / | voi | / | iu | hi | hog-gau? | |||

| not.have | can | will | have | go | school | |||||

| Intended reading: ‘Can/Will/Did Amin go to school, or not?’ | ||||||||||

| (37) | Context: Jane wishes that someone would drive her to the party (she would rather not go if she had to take the bus) … | |||||

| Mo, | ngai | moi | hi | ho | le. | |

| not.have | I | do.not | go | good | SFP | |

| ‘If it’s not the case, it is better for me not to go.’ | ||||||

| (38) | 順 | 則 | 進, | 否 | 則 | 退。 |

| Shun | ze | jin, | fou | ze | tui. | |

| accept | then | proceed | not.be | then | hold.back | |

| ‘If (your opinion) is accepted, then proceed; if that is not the case, then hold back.’ (Yanzi Chunqiu 3.14, from Aldridge, 2011, p. 11) | ||||||

| (39) | a. | Amin | m-di | [gi | iu | ti | ia | mo]. |

| Amin | not-know | he | have | at | here | not.have | ||

| ‘Amin doesn’t know whether he is here.’ | ||||||||

| b. | *Wo | bu-zhidao | [ta | zai | ma]. | |||

| I | not-know | he | at | Q | ||||

| ‘I don’t know wether he is here.’ (Aldridge, 2011, p. 8) | ||||||||

The proposed account is capable of addressing the problems that remain in the previous literature.11 On the other hand, these observations of Sixian Hakka appear to provide an answer to the question raised in Section 2: whether there is a third type of NPQ, distinct from those found in agreement and non-agreement languages. We suggest that more than two types of NPQs may exist cross-linguistically.12

5. Conclusions

This work points out potential issues in the previous literature on VP-mo questions in Sixian Hakka and provides a syntactic analysis that addresses these issues. Adopting Aldridge’s 2011 disjunctive construction analysis, we propose that VP-mo questions share a similar syntactic structure with VP-fou questions in Middle Chinese prior to the 5th century, and that the negator mo in VP-mo questions has grammaticalized into a disjunctive head.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers and editors for their invaluable suggestions and questions, which greatly enriched the original draft, and I also wish to thank Elena Guerzoni, Martina Rizzello, Chenchen Song, Guy Tabachnick, and the audience at SinFonIJA 17 for their insightful feedback.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Abbreviations used in the glosses are as follows: ASP = aspectual marker; CL = classifier; PRT = particle; NEG = negation; PERF = perfective aspect marker; EXP = experiential marker; DET = determiner; PL = plural marker; SFP = sentence-final particle; Q = question marker. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | There are two negators in Sixian Hakka that can be used in negative particle questions (NPQs). One is mo ‘not have,’ as shown in (3), and the other is mang ‘have not … yet,’ illustrated in (i) below. Unlike mo, mang is a negator that involves an aspectual element. In this work, we focus solely on VP-mo questions, leaving VP-mang questions for future research.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | The Hakka data and native speaker judgments presented in this paper originate from the author and an informant who is originally from Miaoli City in Taiwan. The transcriptions are rendered according to the Taiwan Sixian Hakka Romanization System proclaimed by Ministry of Education, R.O.C., in 2023 (https://hakkadict.moe.edu.tw/search_list/, accessed on 1 September 2024). | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | The data of Sixian Hakka in R.-F. Chung (2000) is collected from southern Taiwan. This variety is also known as Southern Sixian Hakka. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5 | In R.-F. Chung (2000), questions like (5a) are not classified as disjunctive questions but A-not-A questions, which consist of a positive part and a negative part and are observed in Mandarin and other varieties of Chinese. See (9) for an illustration. See R.-F. Chung (2000) for more details of the treatment. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6 | An A-not-A question is not very productive in Sixian Hakka. Only a limited set of auxiliaries, e.g., voi ‘will’ and he ‘be’ may occur in such a construction, as shown in (i). Other verbs such as siid ‘eat’ are not allowed, as exemplified in (ii).

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7 | Example (19) is adapted from Y.-J. J. Hsieh (2013), with both the original context and the translation slightly modified. In addition, since Hsieh 2013 does not provide a counterpart example of Mandarin A-not-A questions, Example (18) is provided by us. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8 | C.-T. J. Huang (1991) argues that there are two types of A-not-A questions, AB-not-A and A-not-AB, as shown in (i). The A-not-A questions we discuss here are of the A-not-AB type.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 9 | Examples (25)–(28), taken from L. L.-S. Cheng et al. (1997), are used in their work to illustrate negation and verb/aspect agreement. Although they do not form an ideal minimal pair, we cite them here as they still serve to highlight the relevant contrast. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10 | An anonymous reviewer asks whether there exists further evidence in Hakka suggesting that mo is shifting toward a more functional role distinct from its use as a simple verbal negator. We think that the absence of a negative interpretation of mo in VP-mo questions (see the contrast in (5)) may serve as evidence for its ongoing grammaticalization (cf. Liu, 1998; F. Wu, 1997; H. Wu, 1987), as semantic bleaching—the gradual loss of a word’s original lexical meaning in favor of a more grammatical function—is a key characteristic of this process. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 11 | An anonymous reviewer asks if our proposal accounts for the example (5b), in which the marker of disjunction ia, ‘or’, and the negator mo co-occur in the same sentence. The answer is yes. We propose that mo in VP-mo questions has been grammaticalized as the head of the disjunctive phrase. In other situations, mo remains a marker of negation. Mo in (5b) and mo in (5c) are fundamentally different in syntactic and interpretive terms. First, mo in (5a–b) has the denotation of negation, while in (5c), such a denotation of negation is absent. Second, the agreement between mo and the predicate holds in (5a) and (5b), but not in (5c), as illustrated in (i); the predicate voi hi hog-gau, ‘will go to school’, is not compatible with negator mo, but is fine in the VP-mo question.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12 | An anonymous reviewer suggests explicitly comparing the properties of Hakka VP-mo questions with those in other Chinese varieties. While this is a valid point, such a comparison unfortunately goes beyond the scope of the present study and should be reserved for future research. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- Aldridge, E. (2011). Neg-to-Q: The historical origin and development of question particles in Chinese. The Linguistic Review, 28(4), 411–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.-M. (2007). Hailu keyu yuqici yanjiu [Research of hai-lu Hakka modal particle] [Master’s Thesis, National Central University]. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, L. L.-S., Huang, J., & Tang, J. (1996). Negative particle questions: A dialectal comparison. In J. Black, & V. Motapanyane (Eds.), Microparametric syntax (pp. 41–78). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, L. L.-S., Huang, J., & Tang, J. (1997). Negative particle questions: A dialectal perspective. Journal of Chinese Linguistics, 10, 65–112. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, R.-F. (2000). Ke jia hua de yi wen ju [The structure of Hakka interrogative sentences]. Chinese Studies/Hanxue Yanjiu, 18(Special issue), 147–174. [Google Scholar]

- Duffield, N. (2013). Head-first: On the head-initiality of Vietnamese clauses. In D. Hole, & E. Löbel (Eds.), Linguistics of Vietnamese: An international survey (pp. 127–155). Mouton de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, L. (2025). Taiwan hailu kejiahua jumozhuci yanjiu [A study of the sentence-final particles in Taiwanese hailu Hakka] [Ph.D. Thesis, National Taiwan Normal Univerisity]. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, M.-L. (2001). Form and meaning: Negation and question in Chinese [Ph.D. Thesis, University of Southern California]. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, Y.-J. J. (2013). On negation and interrogatives in Hakka [Master’s Thesis, National Taiwan Normal Univerisity]. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, C.-T. J. (1991). Modularity and Chinese A-not-A questions. In C. Georgopoulos, & R. Ishihara (Eds.), Interdisciplinary approaches to language. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, R.-H. (2008). Deriving VP-neg questions in modern Chinese: A unified analysis of A-NOT-A syntax. Taiwan Journal of Linguistics, 6(1), 1–54. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B. (2006). Chinese final particles and the syntax of the periphery [Ph.D. Thesis, Leiden University]. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, Y. L. I., & Lin, T. H. J. (2024). The left-peripheral nature of the right-edge particle Không in Vietnamese. Taiwan Journal of Linguistics, 22(1), 115–133. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z. (1998). Fanfu wenju de lishi fazhan [Historical development of alternative questions]. In X. Guo (Ed.), Guhanyu yufa lunji [Papers on classical Chinese grammar] (pp. 566–582). Yuwen Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, V. J. (2015). Mandarin peripheral construals at the syntax-discourse interface. The Linguistic Review, 32(4), 819–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, V. J. (2019). Architecture of the periphery in Chinese. Cartography and Minimalism. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, W. (2014). Why particles are not particular: Sentence-final particles in Chinese as heads of a split CP. Studia Linguistica, 68(1), 77–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzi, L. (1997). The fine structure of the left periphery. In L. Haegeman (Ed.), Elements of grammar (pp. 281–337). Kluwer Academic Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, F. (1997). Cong “VP-neg” shi fanfu wenju de fenhua tan yuqici “ma” de chansheng [On the origin of the question particle ‘ma’ from a VP-neg type disjunctive question]. Zhongguo Yuwen, 256(1), 44–54. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H. (1987). Lun Zutangji zhong yi bu, fou, wu, me shouwei de wenju [On questions with clause-final bu, fou, wu, me in the Zutangji]. Zhongshan Daxue Xuebao, 4, 80–89. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).