Abstract

This study investigates the effect of code-switching (CS) on the processing and attachment resolution of ambiguous relative clauses (RCs) like ‘Bill saw the friend of the neighbor that was talking about football’ by heritage speakers of Spanish. It checks whether code-switching imposes a prosodic break at the place of language change, and whether this prosodic break affects RC parsing, as predicted by the Implicit Prosody Hypothesis: a high attachment (HA) preference results from a prosodic break at the RC. A prosodic break at the preposition ‘of’ in the complex DP ‘the friend of the neighbor’ entails a low attachment (LA) preference. The design compares RC resolution in unilingual sentences (Spanish, with a default preference for HA in RC, and English, with the default LA) with the RC parsing in sentences with CS. The CS occurs at the places of prosodic breaks considered by the IPH. The results show sensitivity to the place of CS in RC attachment. CS prompting LA causes longer response times. The preference for HA in Spanish unilingual sentences is higher than in English ones. Heritage speakers are sensitive to the prosodic effects of CS. However, there is high variability across speakers.

1. Introduction

This paper investigates what parsing strategies heritage bilinguals use across their two languages and whether the place of code-switching (CS) affects the processing and attachment resolution of an ambiguous relative clause (RC). We approach RC parsing at the syntax–prosody interface and compare RC processing in unilingual Spanish and English sentences with sentences with CS. Our innovative method uses CS to elicit potential prosodic effects on RC parsing. We argue that heritage bilinguals differentiate between parsing strategies implemented in each of their languages. However, sentences with CS present an integrated, homogeneous whole. The linguistic target of our experiment is an ambiguous relative clause (RC) in (1).

| (1) | Bill saw the friend of the neighbor that was talking about football on the phone. |

Across both languages, Spanish and English, there are two grammatically possible answers to the comprehension question in (2): the friend (2a) or the neighbor (2b) could be talking about football.

| (2) | Who was talking about football? (a) the friend; (b) the neighbor. |

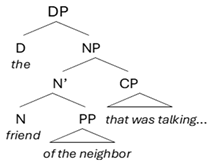

However, native speakers of English consistently prefer answer (b) the neighbor (Frazier & Traxler, 2008; Traxler et al., 1998, 2000; Frazier & Clifton, 1997; Traxler & Pickering, 1996; Frazier, 1990; Ferreira & Clifton, 1986; Rayner et al., 1983; Frazier & Fodor, 1978, among many others), whereas native speakers of Spanish stick to option (a) the friend (European Spanish: Cuetos & Mitchell, 1988; Hemforth et al., 1998; Zagar et al., 1997; Carreiras & Clifton, 1999; Carreiras et al., 2004; Cuetos & Mitchell, 1988; Gilboy et al., 1995; Mexican Spanish: Jegerski et al., 2016). To come up with either of the answers, the human mind needs to perform a certain structural analysis. It can either attach the RC to the entire complex DP, the friend of the neighbor (3a), which is higher in the syntactic tree (high attachment (HA)). Alternatively, it can unpack the DP and attach the RC to the lower noun (3b), which is low attachment (LA) in syntactic terms.

| (3) | Bill saw the friend of the neighbor that was talking about football on the phone. |

| |

| Bill saw [DP [DP the friend of the neighbor] [RC that was talking about football on the phone]]. | |

| |

| |

| Bill saw [DP the friend of [DP the neighbor [RC that was talking about football on the phone]]] | |

|

The mystery of ambiguous RCs has inspired a lot of linguistic and psycholinguistic research. Early studies in human language parsing took the preference for LA in English as evidence for a universally preferred parsing principle: —Minimal Attachment (Frazier & Fodor, 1978; Frazier & Rayner, 1987, among many others). This assumption was challenged by Cuetos and Mitchell (1988), who demonstrated a consistent preference for HA in Spanish monolinguals. They also suggested the Tuning Hypothesis, accounting for the variation in RC attachment across languages. Although this hypothesis has been tested in the field of heritage bilingualism, there is insufficient data to determine whether it accurately predicts the preferences of heritage speakers.

The Tuning Hypothesis claims that RC attachment is sensitive to the frequency of occurrence, i.e., the processor favors the pattern of RC attachment to which it has been exposed more frequently. Dussias (2004) and Dussias and Sagarra (2007) extended this hypothesis to the world of bilingualism. They proposed that bilingual parsing was governed by a single processor sensitive to the frequency of input. In their experiments, English-dominant Spanish–English bilinguals who resided in the English-speaking environment preferred LA across both languages (Dussias, 2004; Dussias & Sagarra, 2007).

A series of studies by Jegerski et al. (2016) challenged the findings of Dussias (2004) and Dussias and Sagarra (2007). Jegerski and collaborators focused on the populations of heritage speakers of Spanish in the USA. Their participants demonstrated RC resolution of around 68.7% of HA in Spanish and around 47.8% in English. The difference in RC attachment between Spanish and English was more pronounced in heritage Spanish–English bilinguals than in late Spanish–English bilinguals. The latter demonstrated HA of 57.1% in Spanish and 50.5% in English. Jegerski et al. (2016) argued that their participants demonstrated a ‘language-neutral’ attachment preference with a tendency to favor HA in Spanish.

The findings by Jegerski et al. (2016) are insightful into how bilinguals operate each of their languages, i.e., there is a tendency to favor HA in Spanish and LA in English. In other words, heritage bilinguals can acquire the parsing preferences typical for each of their languages, an assumption aligning with the differential access approach to the linguistic competence of heritage bilinguals (Perez-Cortes et al., 2019; Putnam & Sánchez, 2013).

The debate over bilingual competence is based on the nature of heritage language acquisition. Heritage speakers (HSs) are bilinguals who learned their heritage language (HL) at home from family members as an L1 and are exposed to a majority language by the age of four (Montrul, 2011). As a result, many HSs may reduce their use of HL once schooling has begun. Over time, HSs display differences in their HL when compared with monolinguals or late sequential bilinguals of the same language. Theoretically, this difference has been treated as a matter of incomplete acquisition (Montrul, 2023) or differential access (Perez-Cortes et al., 2019; Putnam & Sánchez, 2013).

The incomplete acquisition approach posits that HSs do not fully acquire the grammar of their HL because of reduced input in childhood. Therefore, their language behaviors are distinct from those of monolinguals. Conversely, the differential access models argue that HSs maintain access to their heritage grammar regardless of reduced input. However, the developmental trajectory of the HL can systematically differ from monolinguals because of various usage- and exposure-based factors.

Considering the findings of Jegerski et al. (2016) and the rationale of the differential access models, we assume that heritage bilinguals acquire the parsing strategy preferred in a given language. However, it is not completely clear what psycholinguistic mechanism drives this acquisition. A feasible answer is language prosody. To be more specific, there is an assumption, the Implicit Prosody Hypothesis (IPH, Fodor, 2002), which argues that RC attachment is prompted by a prosodic break typical for a certain language.

According to the IPH, HA languages have a prosodic break before the RC (4a). This break puts the complex DP and the RC into separate prosodic units, and the RC is attached to the entire DP. This combination returns HA (see 3a). Alternatively, LA languages have a prosodic break inside the complex DP (4b). It occurs before the preposition ‘of’ and joins the lower DP and the RC into a single prosodic unit. This way, the RC is attached to the lower noun (see 3b).

| 4a. | Bill called the friend of the neighbor [break] [RC that was talking about football on the phone] |

| 4b. | Bill called the friend [break] of the neighbor [RC that was talking about football on the phone] |

Concerning ambiguous RCs, the IPH claims that prosodic information is implicitly used in silent reading. Therefore, it informs the parsing decision of the human mind. The effect of a prosodic break was tested in auditory processing experiments in Spanish (Fromont et al., 2017) and in English as L1 and L2 (Goad et al., 2021). The prosodic break was artificially created either before the RC, as in (4a), or inside the complex DP, as in (4b). The results supported the predictions of the IPH.

There are self-paced reading experiments that tested implicit prosodic effects on sentence parsing. These studies demonstrate that the prosodic weight of a constituent affects RC parsing. Thus, long RCs return HA in English as an L1 or L2 (Sokolova & Slabakova, 2021; Dekydtspotter et al., 2008), whereas short RCs attach low. In heritage speakers, the sensitivity to the prosodic weight of the RC was tested by Jegerski (2018). The author followed a common assumption that heritage speakers have advantages over late bilinguals when it comes to phonology (Montrul, 2011) and tested whether the length of the RC affected RC interpretation accuracy.

Jegerski (2018) used Spanish gender marking to disambiguate the RC toward either the higher or the lower noun and manipulated the length of the RC between the short and the long ones. The results returned longer reading times (RTs) in the disambiguation region in the sentences with short RCs. The longest RT time occurred in the case where the sentence was disambiguated toward HA and the length of the RC prompted LA. The effect was similar in late bilinguals. However, monolinguals demonstrated the longest RT when the sentences were disambiguated toward the lower noun and the RC was short. The interpretation accuracy was not affected by the experimental conditions in any significant way. The author concluded that there was no statistically significant effect of the RC length on the RC processing, even though there was a tendency to process the LA items for longer than the sentences with HA, typical for Spanish.

Summarizing the findings of Jegerski (2018) and the experiments in late bilinguals (Goad et al., 2021; see also Sokolova & Slabakova, 2021; Dekydtspotter et al., 2008), there is evidence that prosodic information affects RC parsing. However, the effect tends to be subtle. The current study takes a new approach to testing the predictions of the IPH and codeswitches from Spanish into English at the places hypothetically affecting RC parsing (4a and 4b). In a broader context, we advance the processing research in bilingualism and expand our understanding of the psycholinguistic mechanisms ensuring the integration of two languages in the human mind.

We conduct a self-paced reading study and compare the processing behavior of heritage speakers of Spanish in unilingual sentences with sentences with CS. A detailed description of this study is provided in the next section.

Before closing the literature review, we would like to bring up an essential methodological question: how to interpret the percentile preference of ambiguous RCs. For example, Jegerski et al. (2016) report 68.7% preference for HA in Spanish and around 47.8% in English. The difference is statistically significant. However, a preference close to 50% was considered as performance at chance level by Clahsen and Felser (2006) (see also Felser et al., 2003a, 2003b). At the same time, Sokolova and Slabakova (2019, 2021) and Witzel et al. (2012) argue that a statistically significant difference between RC preferences across two different languages is enough to claim different parsing strategies implemented in these languages. We follow the latter. If our participants demonstrate a statistically significant difference between RC attachment in Spanish and in English, and this preference goes in the right direction, i.e., toward HA in Spanish and LA in English, we take it as evidence for using different parsing strategies in these two languages.

2. Materials and Methods

This experiment investigated RC processing and attachment resolution by heritage speakers of Spanish in sentences with CS. We followed the Implicit Prosody Hypothesis and compared the prosodic effect of CS with the default prosody of English and Spanish.

We addressed the following research questions (RQs):

RQ1: Are heritage speakers sensitive to the default prosody in each of their L1s, Spanish and English?

Hypothesis 1 to RQ1: Following the experimental results of Jegerski (2018) and Jegerski et al. (2016), we anticipate that heritage speakers differentiate between their two L1s and prefer HA in Spanish and LA in English. The variation across languages occurs due to the participants’ sensitivity to the prosodic structure typical for each language.

RQ2: Does CS affect RC parsing, as predicted by the Implicit Prosody Hypothesis?

Hypothesis 2 to RQ2: Code-switching forces a prosodic break at the place of language change. A prosodic break forced by code-switching prompts the same RC parsing as a prosodic break in a unilingual sentence.

Materials. This study followed the 1-by-4 design, where the experimental tokens formed two subsets: (a) a prosodic break by language; (b) a prosodic break by CS. For a full list of tokens, see Appendix B.

| (5) |

| HA by CS: Bill arrested the friend of the neighbor que hablaba de fútbol en el patio. LA by CS: Bill arrested the friend del vecino que hablaba de fútbol en el patio. |

| HA by language: Guille arrestó al amigo del vecino que hablaba de fútbol en el patio. LA by language: Bill arrested the friend of the neighbor that was talking about football in the yard. |

Method. This study was approved by the NTNU ethics committee, protocol # 937181. It used a self-paced reading methodology, and the experiment was administered via software for psycholinguistic experiments, Linger, available to the public. The participants read sentences on a standard laptop screen (15.7′), seeing one word at a time. Each sentence was followed by a comprehension question with two answer choices. The answer choices probed either HA or LA and were selected by a button press. The reading time at every segment, answer choices, and response time were recorded. There were 32 target sentences and 44 distractors. At the beginning of the session, there were 6 trial items prompting the participants to try all buttons used to navigate through the experiment. The entire experiment, including the paperwork, took 30–45 min to complete.

Participants. The participants were adult heritage speakers of Spanish residing in Chicago and the Chicago area. All participants reported using Spanish as a family language from birth. All of them were literate in Spanish; however, they received their education in English as the language of instruction. They were students or young professionals, with a mean age of 25.3 and a range of 18–31. Participation was voluntary, and the participants could withdraw at any time without any consequences. To qualify for this study, the participants had to be 18 years or older, born in the USA, or brought there before the age of 4. Two people were not heritage speakers of Spanish, and their data were excluded from the analysis. The total number of participants after exclusion was 20.

Procedure. Prior to the experiment, the participants signed a consent form and filled in the background questionnaire, eliciting their linguistic background and patterns of daily use of each of their languages. Then, they carried out a self-paced reading experiment. After the experiment, they completed a descriptive proficiency measure, the C-test, in Spanish (Park, 1998). The full version of the C-test is provided in Appendix A. The C-test contained a total of 60 gaps to fill in; the gaps were open-response. The gaps were evenly spread across three short texts covering general topics: a description of a nice day, a description of a schooling system in the USA, and a description of a sleeping problem. The texts were copied from the public blogs on the Internet, translated into Spanish, and validated with native speakers. The percentage of correct gap filling was calculated, and the participants were divided into three groups: advanced (85–100%), higher intermediate (70–84%), and intermediate (50–74%) speakers of Spanish. The participants were compensated with a gift card for their time.

3. Results

Data analysis. The data was analyzed in R using the lmer package. The independent variables were AnswerChoice and ResponseTime. The answer choice was used as a proxy for RC resolution. The response time was measured to account for the general complexity of a sentence and to compare unilingual sentences and sentences with CS. The dependent variables were condition and proficiency; the random slopes were participant and item.

Both condition and proficiency are multilevel factors. The four levels of the factor condition are presented in Table 1; Table 2 demonstrates the three levels of the proficiency factor.

Table 1.

Levels of condition factor.

Table 2.

Levels of proficiency factor.

Answer choice:

The first step of analysis checked the effect of the place of CS and of the default prosody in RC attachment on the choice of the answer to the comprehension question. The dependent variable was answer choice, the reference category (HA). The independent variables were condition and proficiency. The analysis used the lmer (and glmer) packages. First, we compared two models:

- (1)

- model.all_heritage_done = lmer(PctNoun1 ~ Condition_factor + (1 | Participant) + (1 | Item), data = all_heritage_done, REML = FALSE);

- (2)

- model.all_heritage_done = lmer(PctNoun1 ~ Condition_factor*Proficiency_factor + (1 | Participant) + (1 | Item), data = all_heritage_done, REML = FALSE).

Both models converged. However, the 2nd model had a lower AIC and BIC.

| Model 1: PctNoun1 ~ Condition_factor | ||||

| AIC | BIC | logLik | −2*log(L) | df.resid |

| 940.3 | 971.5 | −463.1 | 926.3 | 633 |

| Model 2: PctNoun1 ~ Condition_factor*Proficiency | ||||

| AIC | BIC | logLik | −2*log(L) | df.resid |

| 893.1 | 959.2 | −431.5 | 863.1 | 593 |

Table 3 reports the significant effects of Model 2. There are no significant simple effects. There is a significant correlation between the condition and proficiency factors.

Table 3.

Model output: PctNoun1 ~ Condition_factor*Proficiency_factor.

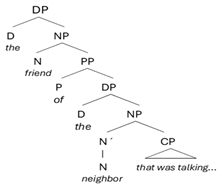

Even though there are no significant simple effects in the analysis, there is a clear tendency to prefer HA in Spanish sentences and less so in English. There is also an observable difference between the sentences where CS prompts HA and the sentences where LA is prompted. The tendency goes in the right direction. Figure 1 presents the results of the answer choice by condition (descriptive statistics).

Figure 1.

Answer choice in each experimental condition.

There are two possible reasons why the effect of condition on answer choice does not reach statistical significance. First, the experiment may not have enough power due to a limited number of participants. Second, there is an extensive variation in answer choices among participants. We will now address them step by step.

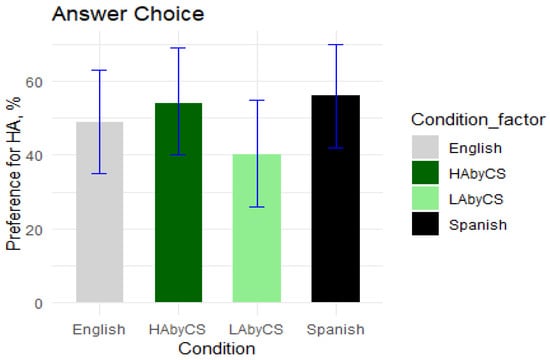

Let us begin with proficiency. Figure 2 demonstrates the data on answer choice in each condition when it is modulated by proficiency. The significant contrasts are proficiency, levels 1 and 2, with condition, levels 1 and 2. The condition factor 1 separates the performance in English from the other conditions. It is significant in correlation with proficiency factor 2, i.e., advanced vs. upper-intermediate. The condition factor 2 separates the performance data between the unilingual sentences and sentences with CS. The high negative value for Spanish, −0.625 (see Table 1), means the performance in Spanish is opposed to the performance in CS more strongly than the performance in English, −125. The correlation is significant with intermediate and upper-intermediate subgroups (see Table 2). The correlations between the condition and proficiency factors are illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Answer choice in each experimental condition by the participants’ proficiency in Spanish.

As can be gathered from Figure 2, advanced speakers do not demonstrate the target-like HA preference in Spanish. Meanwhile, intermediate speakers, the lowest proficiency group in the sample, demonstrate it (Condition_factor2:Proficiency_factor1; p = 0.01). The intermediate participants are also the most sensitive to the effect of CS (Condition_factor2:Proficiency_factor1; p = 0.01), the advanced sub-group is somewhat sensitive (Condition_factor2:Proficiency_factor2; p = 0.05), and the upper-intermediate one is not. The preference in English is more consistent across groups (Condition_factor1:Proficiency_factor2; p = 0.07).

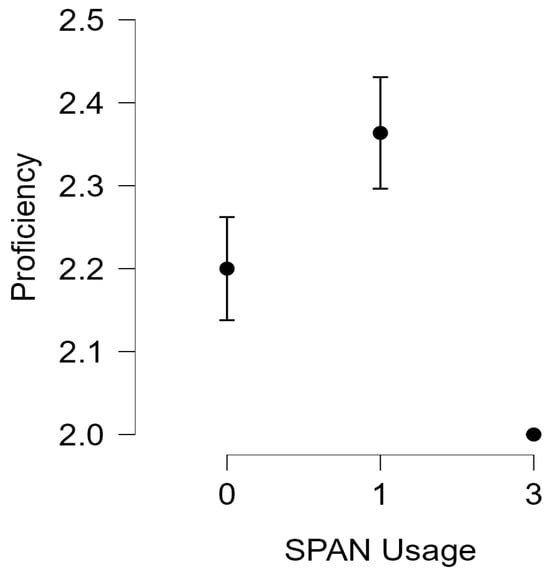

The apparent inconsistency in how proficiency affects the answer choice motivated a closer look at the background questionnaire. We checked whether Spanish proficiency correlated with the patterns of the participants’ daily use of either of their languages. Two things stood out. First, there was no correlation between the amount of daily use of Spanish and the participants’ level of proficiency in Spanish (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Daily usage of Spanish and Spanish proficiency.

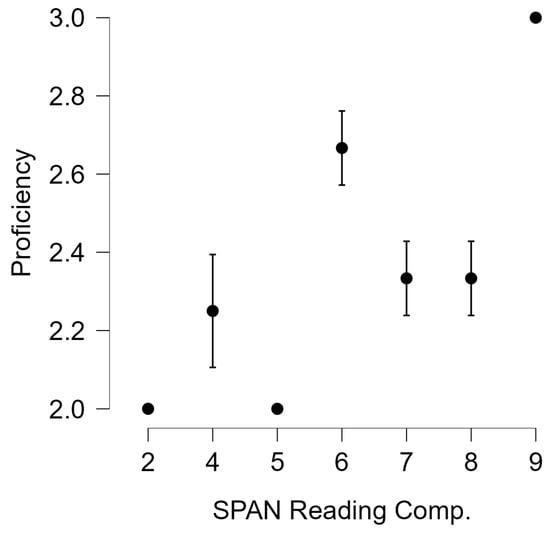

However, there was some meaningful correlation between the participants’ self-ratings of their level of reading comprehension in Spanish and their Spanish proficiency. This correlation is reported in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Self-ratings in reading comprehension and Spanish proficiency.

We assume that some of the participants might have been inaccurate in their estimates of the daily use of Spanish. Alternatively, there could be a meaningful difference between proficiency and exposure: The people who use Spanish the most are not the most proficient in it but prefer the HA, typical for the RC in Spanish, consistently. If this holds true, exposure to the language is a better predictor of the speakers’ parsing behavior than their language proficiency.

To provide a better explanation of the variation across speakers, as well as to account for the limited number of participants, we checked the effect size of the contrasts. We report it as the odds ratio (OR), the effect size for binary outcomes, and r/R2, which explains variance. The odds ratios are reported in Table 4.

Table 4.

Odds ratio for PctNoun1 ~ Condition_factor*Proficiency_factor.

For a factor to have the potential to increase the odds of selecting HA, the odds ratio should be above 1. Among the factors that came out significant, the combination Condition2 × Proficiency1 increases the odds of HA choices by 14 times. Bearing in mind that Proficiency1 (intermediate) on its own demonstrates the odds to select HA lower from the baseline by 38% (1 − 0.62), the combination Condition2 × Proficiency1 elicits the speakers’ sensitivity to the contrast Spanish vs. place CS. Subgroup Proficiency2 has the odds to prefer HA twice as often in Condition2, Spanish vs. place CS, than in the other conditions (Condition2 × Proficiency2 = 2.284).

There is a combination that did not reach statistical significance in the main model; however, its odds ratio is high, at 4.566 (Condition3 × Proficiency1). Condition3 is the contrast between HAbyCS and LAbyCS. This condition increases the odds of selecting HA for the subgroup Proficiency1 (intermediate) by 4 times.

There is another factor that can potentially increase the odds of selecting HA: Condition_factor2, Spanish vs. CS. However, it does not reach statistical significance in the main model.

To account for the general variance, we used the MuMin package to obtain the R2 effect size: r.squaredGLMM(model.all_heritage_done). The results are provided in Table 5. R2m, or R2 marginal, demonstrates the proportion of variance explained by fixed effects only. R2c, or R2conditional, means the proportion of variance explained by fixed + random effects. To account for the potential effect of within-participant variation, we provide the effect size for the model including participant and item as random effects and for the model where only participant is included as a random effect.

Table 5.

R2 effect size.

Table 5 shows that fixed effects explain 3.8% of the data and fixed + random effects explain 6.8% of the data in the model with participant + item as random effects. When only the random effect of participant is included in the model, the proportion of variance explained by fixed + random effects drops to 3.7%. Since R2m = R2c, the random effect (participant) does not explain additional variance. It means that the variance is near zero.

Summarizing the analysis, neither of the random effects (participant or item) accounts for more than 6.8% of the variance in the data obtained. Therefore, the variation is caused by experimental conditions.

Response time:

The raw response time data were log-transformed for the analysis. Same as in the previous analysis, we tested two lmer models, and like the previous analysis, the second model returned a lower AIC and BIC. Therefore, we report the results of Model 2 below.

- (1)

- model.all_heritage_done = lmer(log_RespTime ~ Condition_factor + (1 | Participant) + (1 | Item), data = all_heritage_done, REML = FALSE);

- (2)

- model.all_heritage_done = lmer(log_RespTime ~ Condition_factor*Proficiency_factor + (1 | Participant) + (1 | Item), data = all_heritage_done, REML = FALSE).

| Model 1: log_RespTime ~ Condition_factor | ||||

| AIC | BIC | logLik | −2*log(L) | df.resid |

| 11,302.2 | 11,333.4 | −5644.1 | 11,288.2 | 633 |

| Model 2: log_RespTime ~ Condition_factor*Proficiency | ||||

| AIC | BIC | logLik | −2*log(L) | df.resid |

| 10,760.7 | 10,826.8 | −5365.3 | 10,730.7 | 593 |

Table 6 reports significant effects influencing the response time. There are significant simple effects and a significant correlation between the condition and proficiency factors.

Table 6.

Model output: log_RespTime ~ Condition_factor*Proficiency_factor.

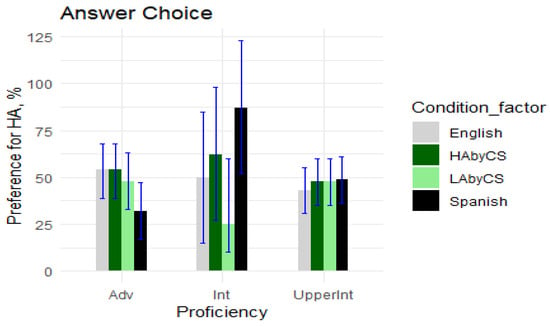

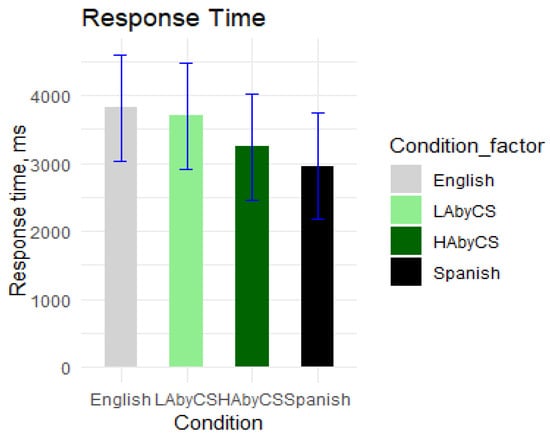

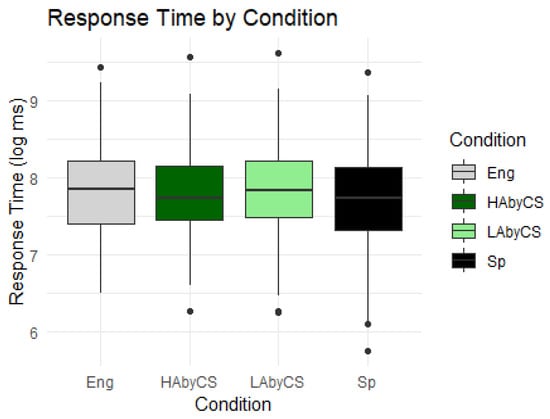

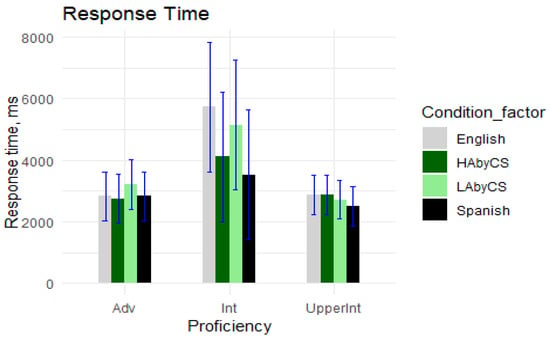

The data on the response time in each condition, as well as the mixed effect of condition by proficiency, are presented below. Figure 5 and Figure 6 present the means and log-transformed response time, respectively. Figure 7 demonstrates the mixed effects of condition and proficiency on the response time.

Figure 5.

Response time, ms. by condition.

Figure 6.

Log response time by condition.

Figure 7.

Response time, ms. by condition and proficiency.

There is a difference in the overall processing complexity among sentences. Unilingual English sentences and sentences promoting LA by CS are more difficult than sentences where HA is prompted by CS or Spanish unilingual sentences.

Like the data on the answer choice, the response time has a strong variability by speaker, as illustrated in Figure 7.

The group pattern demonstrated in Figure 5 and Figure 6 is maintained by the intermediate speakers (Condition_factor1:Proficiency_factor1; p = 0.02). Advanced speakers demonstrate a tendency for longer response times in the sentences that force LA by CS. However, this effect does not reach statistical significance.

4. Discussion

The experiment investigated RC parsing and attachment resolution by adult heritage speakers of Spanish in Chicago and the Chicago area. Our research questions targeted the parsing effects of code switching. We examined whether CS imposes a prosodic break at the place of language change. The experiment followed the IPH and put the prosodic breaks either at the beginning of the RC or inside the complex DP (Fodor, 2002). If CS imposes a prosodic break, the language switch at the beginning of the RC favors HA. LA is prompted if CS takes place at the preposition ‘of’ inside the complex DP, like ‘the friend of the neighbor’. The effect of CS was compared with the participants’ sensitivity to the default prosody of language, i.e., HA is the default parsing preference in Spanish and LA in English.

The results show that there is sensitivity to the place of CS, and the effect goes in the ‘right’ direction: HA is preferred 13% more often than LA if CS occurs at the RC, a HA condition by the effect of CS. However, the effect does not reach statistical significance. Our assumption is that the effect of the place of CS is obscured by the high within-subject variability of the data. Taking a closer look at the background data, we notice that the highest proficiency speakers of Spanish do not demonstrate the target-like HA preference in Spanish. Moreover, the participants who use Spanish most often are not the ones with the highest proficiency. At this point, we can conclude that Spanish proficiency is not a straightforward predictor of the ‘target-like’ processing behavior. We assume that exposure to Spanish is understood broadly and, going beyond daily use of the language, should be. This reversed correlation would go in line with the assumptions of the differential access models of heritage bilingualism, which claim that various usage and exposure-based factors affect the HL developmental trajectory (Perez-Cortes et al., 2019; Putnam & Sánchez, 2013).

Further evidence that heritage bilinguals access each of their grammars is their preference in RC resolution in Spanish and English, with HA being preferred more often in Spanish than in English (Jegerski et al., 2016). In our experiment, the difference was small (56% HA in Spanish and 49% HA in English), and it did not reach statistical significance. The results support the ‘language-neutral’ attachment preference suggested by Jegerski et al. (2016). Even though we cannot report a clear-cut sensitivity to the default prosody in English or Spanish in our group of heritage bilinguals, the reported effect size suggests a strong tendency in that direction. A bigger data pool, therefore, would be more informative.

There is a marginally significant difference in response time between the unilingual sentences and the sentences with CS (Condition_factor2; p = 0.07). It shows a tendency to process English sentences and sentences with LA by CS longer than sentences with HA by CS and Spanish unilingual sentences, but this tendency is very light. At this point, it is difficult to provide a definitive explanation of this result. It is worth noting that the effect reaches statistical significance in the intermediate group only, the participants with the lowest level of proficiency in Spanish. Earlier, we noticed that exposure to the language and proficiency were not correlated directly, and that exposure to Spanish could be a stronger predictor for the target-like parsing behavior. The intermediate group comprises those who use Spanish most often. Therefore, it is possible that their frequent exposure to the HA language makes them slow down in LA conditions, which would be less common. This explanation is purely speculative, as the answer choice does not return a clear HA preference in Spanish, and a different study would be needed to explain the longer response time in the LA condition. At this point, we conclude that two languages in sentences with CS integrate smoothly and do not cause any excessive processing difficulty.

5. Conclusions

Our experiment made a step toward better understanding the mechanisms of heritage language processing. We checked whether the place of CS forces a prosodic break, which, in turn, shapes RC parsing. Even though we only reported a tendency to follow the parsing prompts created by CS, this study is important for the field of heritage bilingualism because it links the theoretical approaches to heritage language acquisition and processing experiments. Our study offers a new research path. We used code-switching to elicit parsing strategies operating across the two languages of a bilingual, which broadens our knowledge of psycholinguistic mechanisms that ensure a smooth integration of languages within the human mind. For the future direction, we would like to investigate how the processing constraints established in monolingual studies affect the parsing of sentences with CS.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S.; methodology, M.S.; software, M.S. and J.W.; validation, M.S. and J.W.; formal analysis, M.S. and J.W.; investigation, M.S. and J.W.; resources, M.S. and J.W.; data curation, M.S. and J.W.; writing—original draft preparation, M.S.; writing—review and editing, M.S. and J.W.; visualization, M.S. and J.W.; supervision—collaboration; project administration, M.S. and J.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Norwegian University of Science and Technology (protocol code 937181, date of approval 23 October 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgement to the Department of Hispanic Studies at the University of Illinois at Chicago for their help in advertising the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

- C-test

- Tarea: Completa los espacios en blanco que consideres necesarios

- ¡Hoy es el mejor día de mi vida! ¡Lo digo todos los días antes de levantarme de la cama! Luego pie______ por q______ estoy agrad______: una ca______ calientita, aq______ en m______ casa, u______ día ven______, café, ag______ corriente, u______ casa bon______, etc. ¡Lu______ me lev______!

- Mientras cond______ hacia l______ ciudad, v______ a una señ______ que con______ mi abu______. Me det______ y le ofrecí llevarla, lo cual aceptó con gusto. La dejé en su destino, a menos de cinco minutos de distancia.

- Eso es un acto de bondad en un solo viaje a la ciudad, pensé. Ahora lo escribiré para Help Others y ¡tal vez sea contagioso!

- Based on https://www.kindspring.org/story/view.php?sid=31665, accessed on 1 August 2016.

- Existen muchas causas posibles del insomnio. A veces h______ una ca______ principal, pe______ a men______ varios fact______ que inter______ entre s______ pueden cau______ un tras______ del su______. Las cau______ del inso______ incluyen: fact______ psicológicos, fís______ o temp______. La fa______ de u______ buen desc______ nocturno pu______ provocar dive______ problemas y puede generarse un círculo vicioso. El asesoramiento profesional de un médico, terapeuta o especialista en sueño puede ayudar a las personas a afrontar estas afecciones.

- Based on https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/9155.php and https://sleepfoundation.org/insomnia/content/what-causes-insomnia, accessed on 1 August 2016.

- El sistema educativo estadounidense tiene diversas estructuras que se establecen a nivel estatal. Para la may______ de l______ niños, l______ escolarización oblig______ comienza alre______ de l______ cinco o seis añ______ y du______ doce añ______ consecutivos. L______ educación e______ obligatoria ha______ los diec______ años co______ mínimo e______ todos l______ estados, y alg______ exigen q______ los estud______ permanezcan e______ un entorno de educación formal hasta los dieciocho años.

- Por lo general, la educación preescolar, conocida como pre-K o pre-kindergarten, se ofrece a niños de entre tres y cinco años. El jardín de infancia es el primer año de educación obligatoria, que normalmente se cursa a los cinco o seis años. A partir de entonces, la educación dura doce años.

- Based on https://transferwise.com/us/blog/american-education-overview, accessed on 1 August 2016.

- Answer key

- ¡Hoy es el mejor día de mi vida! ¡Lo digo todos los días antes de levantarme de la cama! Luego pienso por qué estoy agradecida: una cama calientita, aquí en mi casa, un día ventoso, café, agua corriente, una casa bonita, etc. ¡Luego me levanto!

- Mientras conducía hacia la ciudad, vi a una señora que conocía mi abuela. Me detuve y le ofrecí llevarla, lo cual aceptó con gusto. La dejé en su destino, a menos de cinco minutos de distancia.

- Eso es un acto de bondad en un solo viaje a la ciudad, pensé. Ahora lo escribiré para Help Others y ¡tal vez sea contagioso!

- Based on https://www.kindspring.org/story/view.php?sid=31665, accessed on 1 August 2016

- Existen muchas causas posibles del insomnio. A veces hay una causa principal, pero a menudo varios factores que interactúan entre sí pueden causar un trastorno del sueño. Las causas del insomnio incluyen: factores psicológicos, físicos o temporales. La falta de un buen descanso nocturno puede provocar diversos problemas y puede generarse un círculo vicioso. El asesoramiento profesional de un médico, terapeuta o especialista en sueño puede ayudar a las personas a afrontar estas afecciones.

- Based on https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/9155.php and https://sleepfoundation.org/insomnia/content/what-causes-insomnia, accessed on 1 August 2016.

- El sistema educativo estadounidense tiene diversas estructuras que se establecen a nivel estatal. Para la mayoría de los niños, la escolarización obligatoria comienza alrededor de los cinco o seis años y dura doce años consecutivos. La educación es obligatoria hasta los dieciséis años como mínimo en todos los estados, y algunos exigen que los estudiantes permanezcan en un entorno de educación formal hasta los dieciocho años.

- Por lo general, la educación preescolar, conocida como pre-K o pre-kindergarten, se ofrece a niños de entre tres y cinco años. El jardín de infancia es el primer año de educación obligatoria, que normalmente se cursa a los cinco o seis años. A partir de entonces, la educación dura doce años.

- Based on https://transferwise.com/us/blog/american-education-overview, accessed on 1 August 2016.

Appendix B

| List of experimental tokens |

| 1 |

| Bill arrested the friend of the neighbor that was talking about football in the yard |

| Who was talking about football? friend neighbor |

| Guille arrestó al amigo del vecino que hablaba de fútbol en el patio |

| ¿Quién hablaba de fútbol? amigo vecino |

| Bill arrested the friend of the neighbor que hablaba de fútbol en el patio |

| Who was talking about football? amigo vecino |

| Bill arrested the friend del vecino que hablaba de fútbol en el patio |

| Who was talking about football? amigo vecino |

| 2 |

| Bill arrested the neighbor of the friend that was talking about football in the yard |

| Who was talking about football? friend neighbor |

| Guille arrestó al vecino del amigo que hablaba de fútbol en el patio |

| ¿Quién hablaba de fútbol? amigo vecino |

| Bill arrested the neighbor of the friend que hablaba de fútbol en el patio |

| ¿Quién hablaba de fútbol? friend neighbor |

| Bill arrested the neighbor del amigo que hablaba de fútbol en el patio |

| ¿Quién hablaba de fútbol? friend neighbor |

| 3 |

| The doctor called the sister of the woman that was drinking coffee on the balcony |

| Who was drinking coffee? sister woman |

| El médico llamó a la hermana de la mujer que tomaba café en el balcón |

| ¿Quién tomaba café? hermana mujer |

| The doctor called the sister of the woman que tomaba café en el balcón |

| ¿Quién tomaba café? sister woman |

| The doctor called the sister de la mujer que tomaba café en el balcón |

| ¿Quién tomaba café? sister woman |

| 4 |

| The doctor called the friend of the sister that was drinking coffee on the balcony |

| Who was drinking coffee? sister friend |

| El médico llamó al amigo de la hermana que tomaba café en el balcón |

| ¿Quién tomaba café? hermana amigo |

| The doctor called the friend of the sister que tomaba café en el balcón |

| Who was drinking coffee? hermana amigo |

| The doctor called the friend de la hermana que tomaba café en el balcón |

| Who was drinking coffee? hermana amigo |

| 5 |

| The nurse helped the brother of the man that was writing a letter at the desk |

| Who was writing a letter? brother man |

| La enfermera ayudó al hermano del hombre que escribía una carta en el escritorio |

| ¿Quién escribía la carta? hermano hombre |

| The nurse helped the brother of the man que escribía una carta en el escritorio |

| Who was writing a letter? hermano hombre |

| The nurse helped the brother del hombre que escribía una carta en el escritorio |

| Who was writing a letter? hermano hombre |

| 6 |

| The nurse helped the friend of the brother that as writing a letter at the desk |

| Who was writing a letter? brother friend |

| La enfermera ayudó al amigo del hermano que escribía una carta en el escritorio |

| ¿Quién escribía la carta? hermano amigo |

| The nurse helped the friend of the brother que escribía una carta en el escritorio |

| ¿Quién escribía la carta? brother friend |

| The nurse helped the friend del hermano que escribía una carta en el escritorio |

| ¿Quién escribía la carta? brother friend |

| 7 |

| The teacher praised the brother of the boy that was reading a book in the library |

| Who was reading a book? brother boy |

| La profesora elogió al hermano del chico que leía un libro en la biblioteca |

| ¿Quién leía un libro? hermano chico |

| The teacher praised the brother of the boy que leía un libro en la biblioteca |

| Who was reading a book? hermano chico |

| The teacher praised the brother del chico que leía un libro en la biblioteca |

| Who was reading a book? hermano chico |

| 8 |

| The teacher praised the sister of the girl that was reading a book in the library |

| Who was reading a book? girl sister |

| La profesora elogió a la hermana de la chica que leía un libro en la biblioteca |

| ¿Quién leía un libro? hermana chica |

| The teacher praised the sister of the girl que leía un libro en la biblioteca |

| ¿Quién leía un libro? girl sister |

| The teacher praised the sister de la chica que leía un libro en la biblioteca |

| ¿Quién leía un libro? girl sister |

References

- Carreiras, M., & Clifton, C. (1999). Another word on parsing relative clauses: Eye tracking evidence from Spanish and English. Memory and Cognition, 27(5), 826–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carreiras, M., Salillas, E., & Barber, H. (2004). Event-related potentials elicited during parsing of ambiguous relative clauses in Spanish. Cognitive Brain Research, 20(1), 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clahsen, H., & Felser, C. (2006). Continuity and shallow structures in language processing. Applied Psycholinguistics, 27, 107–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuetos, F., & Mitchell, D. C. (1988). Cross-linguistic differences in parsing: Restrictions on the use of the Late Closure strategy in Spanish. Cognition, 30, 73–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dekydtspotter, L., Donaldson, B., Edmonds, A. C., Fultz, A. L., & Petrush, R. A. (2008). Syntactic and prosodic computation in the resolution of relative clause attachment ambiguity by English-French learners. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 30, 453–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dussias, P. E. (2004). Parsing a first language like a second: The erosion of L1 parsing strategies in Spanish-English bilinguals. International Journal of Bilingualism, 8(3), 355–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dussias, P. E., & Sagarra, N. (2007). The effect of exposure on syntactic parsing in Spanish–English bilinguals. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 10(1), 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felser, C., Marinis, T., & Clahsen, H. (2003a). Children’s processing of ambiguous sentences: A study of relative clause attachment. Language Acquisition, 11, 127–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felser, C., Roberts, L., Marinis, T., & Gross, R. (2003b). The processing of ambiguous sentences by first and second language learners of English. Applied Psycholinguistics, 24, 453–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, F., & Clifton, C. (1986). The independence of syntactic processing. Journal of Memory and Language, 25, 348–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fodor, J. (2002). Psycholinguistics cannot escape prosody. Speech prosody 2002, ISCA archive. Available online: https://www.isca-archive.org/speechprosody_2002/fodor02_speechprosody.html (accessed on 8 June 2023).

- Frazier, L. (1990). Parsing modifiers: Special purpose routines in the human sentence processing mechanism. In Comprehension Processes in Reading (pp. 303–330). Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Frazier, L., & Clifton, C. (1997). Construal: Overview, motivation and some new evidence. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research, 26, 277–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frazier, L., & Fodor, J. D. (1978). The sausage machine: A new two-stage parsing model. Cognition, 6, 291–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazier, L., & Rayner, K. (1987). Resolution of syntactic category ambiguities: Eye movement is parsing lexically ambiguous sentences. Journal of Memory and Language, 26, 505–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazier, L., & Traxler, M. (2008). The role of pragmatic principles in resolving attachment ambiguities: Evidence from eye-movements. Memory and Cognition, 36, 314–28. [Google Scholar]

- Fromont, L. A., Soto-Faraco, S., & Biau, E. (2017). Searching high and low: Prosodic breaks disambiguate relative clauses. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilboy, E., Sopena, J. M., Clifton, C., & Fraizer, L. (1995). Argument structure and association preference in Spanish and English complex NPs. Cognition, 54(2), 131–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goad, H., Guzzo, N. B., & White, L. (2021). Parsing ambiguous relative clauses in L2 English. Learner sensitivity to prosodic cues. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 43, 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemforth, B., Konieczny, L., Scheepers, C., & Strube, G. (1998). Syntactic ambiguity resolution in German. Syntax and Semantics, 31, 293–309. [Google Scholar]

- Jegerski, J. (2018). Sentence processing in Spanish as a heritage language: A self-paced reading study of relative clause attachment. Language Learning, 68(3), 598–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jegerski, J., Keating, J. D., & VanPattern, B. (2016). On-line relative clause attachment strategy in heritage speakers of Spanish. International Journal of Bilingualism, 20(3), 254–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montrul, S. (2011). Introduction: The linguistic competence of heritage speakers. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 33(2), 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montrul, S. (2023). Heritage languages: Language acquired, language lost, language regained. Annual Review of Linguistics, 9, 399–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J. (1998). The C-test: Usefulness for measuringwritten language ability of non-native speakers of English [Master’s thesis, Iowa State University]. [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Cortes, S., Putnam, M. T., & Sánchez, L. (2019). Differential access: Asymmetries in accessing features and building representations in heritage language grammars. Languages, 4(4), 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, M. T., & Sánchez, L. (2013). What’s so Incomplete about Incomplete Acquisition?: A Prolegomenon to Modeling Heritage Language Grammars. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism, 3(4), 478–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayner, K., Carlson, M., & Frazier, L. (1983). The interaction of syntax and semantics during sentence processing: Eye movements in the analysis of semantically biased sentences. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 22, 358–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolova, M., & Slabakova, R. (2019). L3-sentence processing: Language-specific or phenomenon-sensitive. Languages, 4, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolova, M., & Slabakova, R. (2021). Processing similarities between native speakers and non-balanced bilinguals. International Journal of Bilingualism, 25, 1655–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traxler, M. J., & Pickering, M. J. (1996). Plausibility and the processing of unbounded dependencies: An eye-tracking study. Journal of Memory and Language, 35, 454–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traxler, M. J., Pickering, M. J., & Clifton, C. (2000). Ambiguity resolution on sentence processing: Evidence against frequency-based accounts. Journal of Memory and Language, 43, 447–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traxler, M. J., Pickering, M. J., & Clifton, C., Jr. (1998). Adjunct attachment is not a form of ambiguity resolution. Journal of Memory and Language, 39, 558–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witzel, J., Witzel, N., & Nicol, J. (2012). Deeper than shallow: Evidence for structure-based parsing biases in second language sentence processing. Applied Psycholinguistics, 33, 419–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagar, D., Pynte, J., & Rativeau, S. (1997). Evidence for early closure attachment on first-pass reading times in French. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology Section A, 50, 421–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).