Abstract

Falkland Islands English (FIE) began its development in the first half of the 19th century. In part, as a consequence of its youth, FIE is an understudied variety. It shares some morphosyntactic features with other anglophone countries in the Southern Hemisphere, but it also shares lexical features with regional varieties of Spanish, including Rioplatense Spanish. Che is one of many South American words that have entered FIE through Spanish, with its spelling ranging from “chay” and “chey” to “ché”. The word has received some marginal attention in terms of its meaning. It is said to be used in a similar way to the British dear or love and the Australian mate, and it has been compared to chum or pal, and is taken as an equivalent of the River Plate, hey!, hi!, or I say!. In this work, we explore the hypothesis that che entered FIE through historical contact with Rioplatense Spanish, drawing on both linguistic and sociohistorical evidence, and presenting survey, corpus, and ethnographic data that illustrate its current vitality, usage, and social meanings among FIE speakers. In situ observations, fieldwork, and an online survey were used to look into the vitality of che. Concomitantly, by crawling social media and the local press, enough data was gathered to build a small corpus to further study its vitality. A thorough literature review was conducted to hypothesise about the borrowing process involving its entry into FIE. The findings confirm that the word is primarily a vocative, it is commonly used, and it is indicative of a sense of belonging to the Falklands community. Although there is no consensus on the origin of che in the River Plate region, it seems to be the case that it entered FIE during the intense Spanish–English contact that took place during the second half of the 19th century.

1. Introduction

The Falkland Islands, an archipelago in the South Atlantic Ocean, present a unique case of cultural and linguistic contact. Despite their small population and geographic isolation, the Islands have a diverse range of ethnic communities, shaped by successive waves of migration. While the majority of the population is of British descent, Spanish-speaking communities have also played a significant role in the region’s history. According to the 2021 census (Government of the Falkland Islands, 2021), Spanish is the second most spoken language in the Falklands.

This linguistic diversity has influenced the development of Falkland Islands English (henceforth FIE), a distinct dialect that shares some morphosyntactic features with other anglophone countries in the Southern Hemisphere (Wells, 1982; Trudgill, 1986; Britain & Sudbury, 2010). As well as being the result of contact with various British English varieties (Sudbury, 2001) it has been significantly shaped by Rioplatense Spanish1 during the 19th century (Rodríguez, 2022). One of the most distinctive features of FIE is the vocative che, a term borrowed from Spanish that remains in continued use among Islanders today. However, its precise role, vitality, and borrowing process have not been systematically examined.

This study investigates the use of che in the Falkland Islands, focusing on its historical incorporation into FIE and its present usage. It addresses two main questions: (1) how che likely entered FIE, based on linguistic and sociohistorical evidence, and (2) how it is known, used, and perceived by contemporary FIE speakers.

This study fills a knowledge gap by analysing the use of che in FIE through a mixed methods approach that includes ethnographic fieldwork (participant observation and interviews), an online survey, a corpus of social media data, and a thorough literature review. By investigating its patterns of usage and historical origins, we aim to shed light on how contact between English and Spanish has shaped the Islands’ linguistic landscape. To our knowledge, this is the first comprehensive study on the use of che in the Falklands.

The Falkland Islands are a British Overseas Territory, comprising two main islands, East Falkland and West Falkland, with a total population of approximately 3500 inhabitants. The majority reside in Stanley, the capital, while the rest live in rural settlements.

Since the establishment of English settlements in 1833, the Islands have remained predominantly English speaking. However, Spanish-speaking communities, particularly gauchos from the River Plate area, were integral to early Falklands society. Their presence influenced not only agricultural practices, but also the Islands’ linguistic environment, leaving traces of Spanish vocabulary in FIE. The vocative che is one such example, originating from the Gaucho Spanish2 spoken by rural workers during the 19th century (Rodríguez, 2022).

To understand this contact, it is essential to consider the socio-economic context of the time, particularly the livestock industry. Livestock in the Falklands has its roots in the 18th century, when French settlers under Louis-Antoine de Bougainville introduced cattle, pigs, sheep, and horses to the Islands (Strange, 1973). Under Spanish rule, large-scale cattle ranching flourished, and, by 1785, Governor Ramón de Clairac reported the presence of 7774 heads of cattle (Strange, 1973).

In the early 19th century, Luis Vernet, a merchant coming from Buenos Aires, expanded the cattle industry by employing gauchos from the River Plate, who were experts in herding wild cattle and processing hides (Beccaceci, 2017).

The British reasserted sovereignty over the Falklands in 1833, when Captain Onslow raised the British flag, leading to the withdrawal of the Argentine garrison. However, many Spanish-speaking gauchos remained, along with Uruguayan Charrúa Indians and other settlers from diverse backgrounds (Pascoe & Pepper, 2008). Captain Robert Fitz Roy (1839) noted the multiethnic composition of the population, describing gauchos, Indigenous groups, and European settlers living alongside one another.

By the mid-19th century, Scottish and English settlers, encouraged by British migration policies, became the dominant group in the Islands (Sudbury, 2001, 2005). However, Spanish-speaking gauchos continued to work in the cattle industry until the late 19th century (Spruce, 1992). The Falkland Islands Company, established after the purchase of Samuel Fisher Lafone’s rights and interests in the Islands, was instrumental in the commercial development of livestock farming, leading to the decline in wild cattle (Boumphrey, 1967; Strange, 1973). It was during Lafone’s enterprise that gauchos played a crucial role in the Islands’ economy and daily life, influencing local customs, labour practices, and linguistic interactions.

By 1867, the transition to sheep farming was well underway, with sheep replacing cattle as the backbone of the agricultural economy (Beccaceci, 2017). By 1883, the Islands were home to half a million sheep, marking a fundamental shift in land use and labour patterns (Beccaceci, 2017; Strange, 1973). The disappearance of wild cattle from East Falkland (in 1889) and West Falkland (in 1894) reflected the changing economic landscape (Strange, 1973).

Although the gauchos eventually disappeared as a distinct social group, their linguistic legacy endures in FIE. Words and expressions borrowed from Gaucho Spanish, including che, remain embedded in local speech, providing a linguistic window into historical patterns of contact between English and Spanish in the Falklands.

2. Vocative Che

Among the many South American words that have made their way into FIE through Spanish3 is che, with its spelling ranging from chay and chey to ché (according to Blake et al., 2011). Sudbury (2001) states that the word is used in a similar way to the British dear or love and the Australian mate, while Roberts (2002) compared it to chum or pal and, rightly points out, that it is the equivalent, along the River Plate, of hey!, hi!, or I say!

The vocative is a grammatical category used to directly address or call upon a person, typically marked by intonation and position in the sentence rather than inflectional morphology (Zwicky, 1974). Vocatives are inherently polyfunctional: they serve interactional purposes, such as managing turn taking or signalling attention, and also index affective stances, familiarity, and social roles (Leech, 1999). As R. Brown and Gilman (1960) demonstrated in their seminal work on address forms, such expressions participate in the construction of power and solidarity relations. In sociolinguistic terms, vocatives often carry identity work, functioning as socially meaningful forms that can become enregistered and symbolically charged. In this light, the vocative che in Falkland Islands English offers a compelling case for examining the intersection of grammar, social interaction, and the construction of local identity.

The use of che in FIE aligns with a broader class of vocative discourse markers in English that serve interpersonal and pragmatic functions beyond being a mere form of address. Similarly to dude (Kiesling, 2004), mate (Leech, 2014), or love (Mills, 2003), che operates as a marker of stance, affiliation, and contextual positioning, indexing familiarity, informality, and local identity. These vocatives often function to create solidarity or mitigate face-threatening acts, aligning with P. Brown and Levinson’s (1987) theory of politeness. In our data, che similarly signals inclusion and affective proximity, particularly among older or long-established speakers. Furthermore, as we will see in the following sections, che seems to be a culturally enregistered form, whose usage patterns parallel well-documented trends in other varieties of English.

Che is a common form of address in the Río de la Plata, among other South American regions, used to get the attention of an interlocutor. It is a vocative used to address someone, generally requesting a response or a reaction. In the context of Rioplatense Spanish, che can appear in various contexts, both diachronic and synchronic, and its use is very frequent in both Argentina and Uruguay, but also in Chilean Patagonia and southern Brazil.

Several studies have examined the vocative che in Rioplatense Spanish from grammatical, pragmatic, and historical perspectives. Borzi (2016) describes the pragmatic, semantic, and syntactic contexts of use of the form che, while Resnik (2024) proposes a functional classification of che as a vocative nucleus, a vocative particle, and an interjection, highlighting its grammaticalization alongside other colloquial vocatives. Bertolotti (2010), in turn, reviews major hypotheses regarding its etymology and suggests, like Rona (1963), that che may derive from a nominal determiner in Guarani, opening up a perspective that connects language contact with pragmatic innovation.

To analyse the incorporation of che into Falkland Islands English, this study draws on the concept of enregisterment, understood as the process through which a linguistic form becomes socially recognized and associated with particular speaker identities or registers (Agha, 2007; Johnstone et al., 2006). Che, in this sense, may be interpreted not simply as a borrowed term, but as a socially meaningful form, whose function and value have been (re)shaped through local usage and interaction. The related notion of social indexicality (Silverstein, 2003) is also central to this analysis, as it helps reveal the layered meanings attached to che within specific social contexts.

3. Aim and Methodology

The primary objective of this study is to examine the use of che in the Falkland Islands, focusing on its current vitality and the process by which it entered FIE.

It addresses the following research questions:

- (1)

- What is the most plausible pathway through which che entered FIE?

- (2)

- To what extent is che known, used, and socially meaningful among FIE speakers?

To address these questions, we employed a mixed methods approach that integrates the following qualitative and quantitative research techniques (see Table 1):

- –

- An online survey was designed to measure speakers’ awareness, usage, and perceptions of che across different demographics;

- –

- Ethnographic interviews and participant observations were conducted in situ to assess attitudes towards che and its vitality in natural speech and everyday interactions;

- –

- A corpus of social media data and local press content were compiled to examine contemporary patterns of use in written discourse;

- –

- A comprehensive literature review of relevant history and linguistics was carried out to trace the origin of che and analyse the borrowing process involving its entry into FIE.

Table 1.

Methods for data collection, based on the focus area.

Table 1.

Methods for data collection, based on the focus area.

| Technique | Data | Focus Area |

|---|---|---|

| Survey | Online questionnaire | Awareness, use, and perception toward che |

| Fieldwork | Ethnographic interviews and participant observations | Speaker attitudes and vitality of che |

| Corpus analysis | Social media and press | Written discourse and usage patterns of che |

| Literature review | Historical and linguistic sources | Borrowing process of che into FIE |

By integrating ethnographic and sociolinguistic methodologies, this study provides a comprehensive account of che as a linguistic feature in FIE, offering insights into both its historical development and contemporary usage.

3.1. Survey

An online survey was conducted to gather quantitative data on the awareness, usage, and perceptions of che among FIE speakers. The survey was anonymous and designed to ensure broad participation across different demographic groups4.

A questionnaire was administered in English and distributed during July 2019 via Facebook’s paid advertisement system, allowing it to reach a wider audience beyond the immediate personal networks of the researchers. The use of a targeted social media campaign ensured that the survey was visible to residents of the Falkland Islands, increasing the likelihood of obtaining responses from individuals of diverse ages, professions, and linguistic backgrounds.

Sixty-five residents of the Falkland Islands completed the survey. The respondents ranged in age from their early 20s to late 70s, with the majority being over 50 years old. Most participants were born in Stanley or elsewhere in the Falklands, though a few were born abroad and had lived on the Islands for extended periods. English was consistently reported as their first language. The sample included both men and women, with a slight majority of female respondents.

The survey focused on the following three main areas:

- –

- Awareness of che—Whether respondents recognise the term and associate it with FIE. (Do you know the word “chey”?)5

- –

- Usage patterns—How frequently, in what contexts, and by whom che is used. (Have you heard Islanders using the word “chey”? Have you ever used the word “chey”?)

- –

- Perceptions—Attitudes toward che, including whether it is considered a feature of local identity or an outdated/marked term. (Would you say “chey” is part of Falkland Islands English?)

We then proceeded to integrate survey data with the qualitative insights from the ethnographic fieldwork, in order to gain a nuanced understanding of che as a linguistic feature in FIE, capturing both self-reported perspectives and naturally occurring usage.

3.2. Fieldwork

As part of our ethnographic approach, we conducted interviews and participant observations to explore the use of che among both Camp (the Falklands vernacular for countryside) and Stanley dwellers. Interviews were conducted by the first author, while the second author was responsible for long-term participant observations. Informants were primarily Islanders, with a small number of immigrants also included. Given the small population of the Falklands, all personal identifiers have been carefully anonymised to protect informant privacy6. Interviews were conducted between December 2019 and March 2020; participant observations were conducted between November 2020 and January 2024.

3.2.1. Fieldwork Interview Tools

The fieldwork tools for the interviews included:

- –

- Field notes, ensuring a detailed record was captured of the observed interactions;

- –

- A camera, used to document relevant linguistic and cultural contexts;

- –

- A field diary, for reflections and real-time analysis of participant interactions;

- –

- A recorder, for high-fidelity audio data collection, in accordance with ethnographic research principles (Guber, 2001).

Interviews were conducted with individuals from diverse age groups and geographic areas, covering both Stanley and Camp (covering both of the main islands, East and West Falkland). Recruitment followed a snowball sampling approach, which facilitated the inclusion of 20 respondents, 16 were L1 English speakers and 4 were L1 Spanish speakers, both groups have knowledge of the other language, although the level varies. The interviews explored topics such as personal language use, perceptions of che, changes over time, and social meanings associated with the term. They lasted between 60 and 90 min, with an average duration of 70 min. All the interviews were transcribed; however, full transcripts are not available on an open access platform due to ethical and safeguarding restrictions.

Every interview was conducted in the informant’s L1. However, to further safeguard the participants’ anonymity, the language of each interview is not disclosed in the transcriptions (all are in English). Additionally, some pronouns were modified in the transcripts and analysis to further prevent identification.

Prior to participation, each interviewee received an information letter outlining the scope of the study and provided informed consent using formats approved by the Ethics Committees at both the Universiteit Leiden and the Universidad de la República. Consent for audio recording was explicitly granted by all the participants prior to the interviews.

3.2.2. Long-Term Participant Observations

The second author, who has resided in the Falkland Islands for over 20 years, contributed sustained participant observation data, offering a depth of engagement that short-term fieldwork could not provide. Their long-term immersion in the community enabled the following benefits to be gained:

- –

- A more nuanced understanding of local linguistic attitudes and everyday interactions;

- –

- Access to naturally occurring conversations, capturing spontaneous linguistic exchanges that structured interviews might not elicit;

- –

- Enhanced contextual insights, enriching the overall ethnographic analysis.

By integrating lived experience with systematic observations, the second author played a critical role in strengthening the robustness of our findings, ensuring a comprehensive and context-sensitive interpretation of che in FIE.

Such immersive observation provides access to spontaneous language use and community norms that are difficult to capture through the use of short-term methods (see Emerson et al., 2011). The “observed interactions” refer to naturally occurring conversations outside of the interview setting, documented as part of participant observations, not elicited speech during interviews. While interviews were audio recorded with participant consent, naturally occurring conversations observed during daily life were not systematically documented, due to ethical considerations and contextual constraints. Observations were documented in detailed field notes and used to complement the findings from recorded interviews and survey responses. We acknowledge subjectivity as inherent to ethnography and address it through triangulation with other data sources.

3.3. Corpus

Conducting corpus-based research on lesser-known varieties presents significant challenges, particularly when working with languages spoken by small communities, with limited written production (Meyerhoff, 2012). This difficulty arises when the linguistic community under scrutiny is small, generates few textual records, or when the phenomenon being analysed is primarily a feature of spoken language.

These constraints apply to FIE (see Rodríguez et al., 2023), as locally produced written material is scarce, particularly in literary and informal registers. Additionally, the vocative che is mainly an oral feature, meaning its occurrence in written sources is limited and highly context dependent, appearing only in specific conversational topics or informal dialogues.

To overcome these limitations, we compiled a consecutive corpus using two main sources, as follows:

- Social media data—Posts from Instagram and Twitter (now known as X), as well as comments from publicly available Falklands-related Facebook pages and discussion forums, where informal language use is more likely to appear. A total of 56 posts and comments were collected and manually reviewed.

- Local press articles—Newspaper content and other written media produced in the Falkland Islands, providing insight into how che is represented in more formal or semi-formal written contexts.

Both social media and press data were compiled between 2019 and 20247. The selection criteria included the presence of the term che, contextual clarity, and identifiable authorship linked to Falklands-based users or communities. While this corpus does not provide extensive quantitative data, it serves as a valuable resource for detecting instances of che in written communication and identifying potential shifts in usage. Combined with ethnographic observations and survey responses, it enables the adoption of a triangulated approach to analysing the vitality and function of che within FIE.

3.4. Literature Review

To contextualise the presence of che in FIE and trace its origin and the borrowing process, a comprehensive literature review was conducted, drawing from research on historical linguistics, language contact, and sociolinguistics.

Given the scarcity of prior studies on che in the Falklands, the review focused on the following two key areas:

- Historical and etymological evidence, which involved reviewing linguistic and philological studies on the origin and evolution of che in Spanish, especially its emergence in the Rioplatense dialect;

- The historical processes of language contact, which involved studying documentary and historiographic sources on Spanish-speaking presence and language contact in the Falkland Islands, with particular attention to migratory, educational, and labour-related dynamics that may have facilitated the borrowing of che.

This literature review provided the theoretical foundation for interpreting the survey, ethnographic data, and corpus, allowing for a historically and linguistically informed discussion on che in FIE.

4. Results

This section presents the findings in alignment with the two research questions guiding this study: (1) what is the most plausible pathway through which che entered FIE? and (2) to what extent is che known, used, and socially meaningful among FIE speakers?

Each subsection below addresses these questions through analysis of the survey, ethnographic fieldwork, corpus, and historical data. Additionally, the data revealed patterns beyond the initial scope of the study, providing insights into broader aspects of the phenomenon. These unexpected findings contribute to a deeper understanding of the dynamics of language contact and social interaction in the Islands, offering valuable perspectives for future research.

4.1. What Is the Origin of Che, and How Did It Reach the Falklands?

Based on our historical and linguistic literature review it is clear that che entered FIE through contact with Rioplatense Spanish. FIE shares the vocative che with a Sprachbund that includes Argentina, Paraguay, Uruguay, Chilean Patagonia, and southern Brazil. The archipelago has had strong migratory bonds with most of that region. Amongst the strongest bonds is the one with the port capital of Uruguay, Montevideo, where che is widely used.

There is very little literature on FIE. Within it, Roberts’ (2002) and Sudbury’s (2001) reports are in line with our stance. The latter hypothesised that “it is most likely derived from Spanish che”, and pointed to the fact that there may be a slight degree of regional variation with respect to its use in the archipelago, with che being used more on West Falkland than on the East. Moreover, Roberts (2002) pointed out that:

A most common and friendly word of Latin American origin in Falkland Island usage, especially in Stanley, was “Chay” which simply meant “chum” or “pal”. The word comes from “Che!” which, in Spanish–English dictionaries, is interpreted as the equivalent, along the River Plate, of “hey!”, “hi!” or “I say!” but, for example, a Falkland Islander might well say, “Hey! Chay, did you know that …?” It would be hard to say which Latin American word an incomer to Port Stanley would learn first, “Camp” or “Chay”. Perhaps “chow”, another word of River Plate origin but in turn derived from the Italian, “ciao”, and meaning so long or goodbye, would be a close rival and for this “adios” not unknown either.(p. 13)

The route of che into FIE is clear; however, its roots within South American language history, in particular Rioplatense Spanish, remain unresolved. A handful of scholars have dealt with the problem (e.g., Rona, 1963; De Marsilio, 1969; Bertolotti, 2010, 2015; Bertolotti & Coll, 2014; Moyna, 2017; Resnik, 2024; among others). Resnik (2024) explains that its etymology has been variously traced to a noun or affix in Mapudungun (referred to as “Araucanian” in Abeille, 1900/2005, “Mapuche” in Lenz, 1904), to a Guarani determiner (Rona, 1963; Bertolotti, 2010), and even to an Iberian Spanish interjection (Rosenblat, 1962). Tracing through dictionary definitions, we find that the dictionaries of the Real Academia Española (Royal Spanish Academy) hardly help to attribute an origin to it (i.e., Diccionario de la Lengua Española and Diccionario de Americanismos). However, the dictionary of the Falkland Islands (Blake et al., 2011) points out that it is an indigenous word from South America and that its meaning appears to be the same as in Spanish (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Meanings and origins attributed to che in dictionaries8.

To enable a meaningful comparison between the use of che in Rioplatense Spanish and in FIE, we include here illustrative examples drawn from naturally occurring speech in Rioplatense Spanish. These examples, which were heard by the first author during informal conversations in 2025, highlight the typical pragmatic functions of che.

Examples of vocative use (addressing someone directly) are as follows:

- Che, vení para acá un segundo.

‘Hey, come here for a second.’

- 2.

- ¿Qué hacés, che? Tanto tiempo.

‘How are you, man? It’s been a while.’

Examples of emphatic or emotional reinforcement are as follows:

- 3.

- ¡Che, no sabés lo que me pasó!

‘Hey, you won’t believe what happened to me!’

- 4.

- ¡Qué frío hace hoy, che!

‘It’s so cold today, man!’

Example of solidarity and an affective stance are as follows:

- 5.

- Te juro que lo intenté, che, pero no me salió.

‘I swear I tried, man, but it didn’t work out.

These examples show that che in Rioplatense Spanish often co-occurs with informal registers and expresses familiarity, solidarity, or an emotional emphasis. It typically precedes or follows a statement and rarely carries lexical content, functioning instead as a discourse-pragmatic marker.

By comparing these uses with the patterns observed in FIE, a notable contrast emerges. While che in Rioplatense Spanish circulates widely and informally across diverse interactional settings, its use in FIE appears to be more context dependent and socially marked. Interview excerpts suggest that FIE speakers deploy che not only to express camaraderie, but also to align themselves with a localised identity. In some cases, the use of che seems to be almost performative, signalling insider status or familiarity with local ways of speaking. This layered functionality highlights its potential as both an index of affective stance and a strategic tool in identity negotiation.

4.2. To What Extent Is Che Known, Used, and Accepted by FIE Speakers?

This section presents the findings related to the vitality of che within the Falkland Islands. It draws on the ethnographic observations, interviews, social media analysis, and survey data to assess the knowledge, usage, and attitudes toward che among Islanders of different ages and backgrounds. Thematic interpretations, such as positive affect (“friendly,” “nice”), local identity (“a Falklands term,” “shows you’re from here”), and generational usage (“older people still say it,” “not common now”), emerged inductively through the open coding of responses and guided the analysis.

Open coding of the qualitative responses revealed recurring themes regarding the social value and distribution of che in FIE. Many speakers framed it as a friendly or positive expression, describing it as “a nice word” or “a friendly term”. This framing suggests a general perception of che as an affiliative marker, contributing to a positive interpersonal tone.

Another prominent theme was its association with local identity. Participants referred to che as “a Falklands term” or noted that “it shows you’re from here,” indicating that it serves as a marker of belonging and insiderness within the community.

At the same time, numerous participants referenced generational variations, noting that “older people still say it”, or that they “used to hear it more”. These statements highlight a perceived temporal shift in the frequency and context of its use, with che sometimes framed as part of a traditional speech style that is “not so common now.”

Together, these themes point to the dynamic status of che in FIE: while still recognised and often positively valued, it is also perceived as undergoing change, shaped by age, community affiliation, and shifting linguistic practices.

The following subsections analyse the current vitality and perception of che, highlighting patterns, contrasts, and social meanings that emerge from its use, and framing these in relation to theories of indexicality and enregisterment.

4.2.1. Che as a Vocative and Demonym

The vocative che is primarily used as a term of address, but it also appears in regard to nominal functions, as a nickname, demonym, or group label. This subsection documents examples of its use in everyday speech, social media, and public signage, illustrating the range of its contemporary functions.

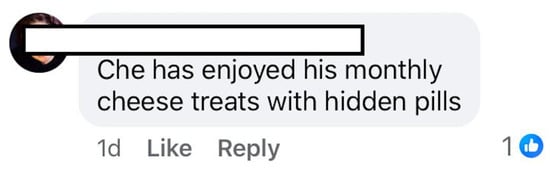

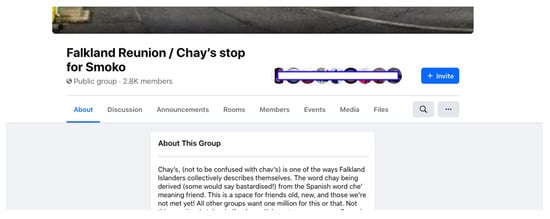

Che is used mainly as a term of address (see Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4), in the form of a vocative. However, it is sometimes used as a proper name (see Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8) or demonym (see Figure 9 and Figure 10).

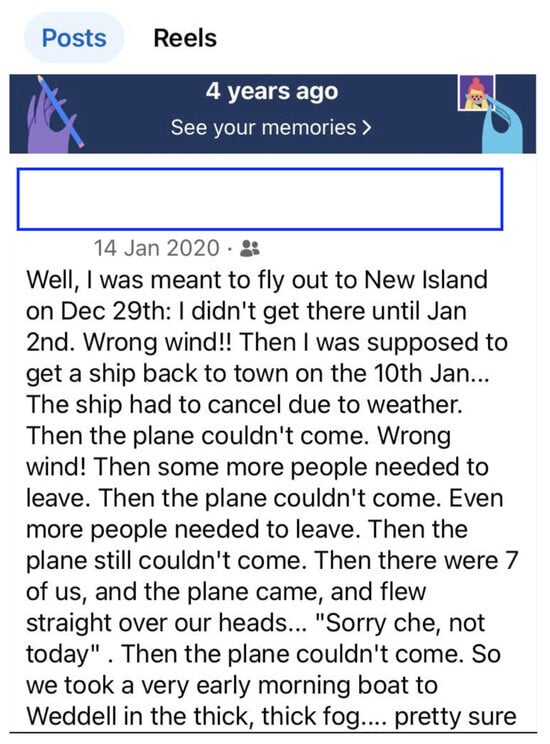

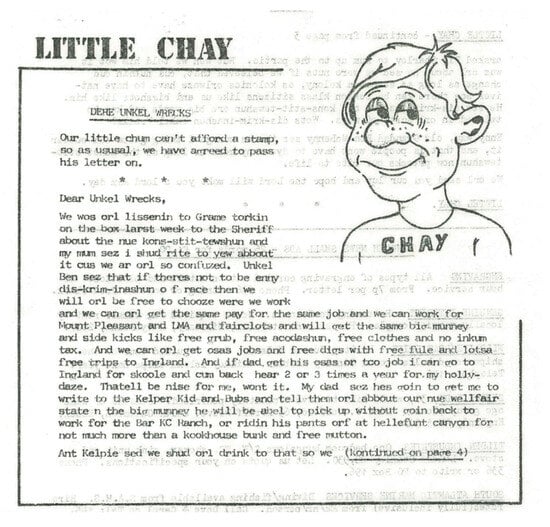

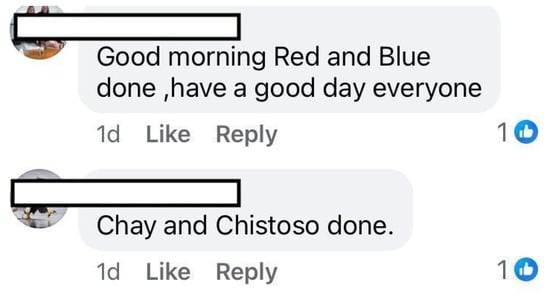

Figure 1.

Example 1 of che used as a term of address.

Figure 2.

Example 2 of che used as a term of address.

Figure 3.

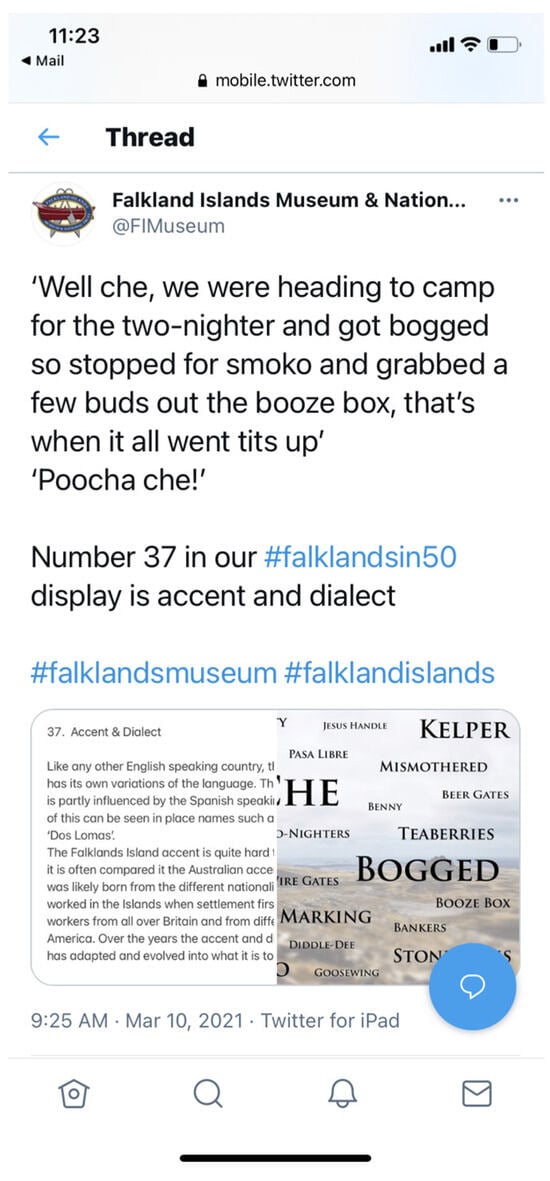

Example 3 of che used as a term of address.

Figure 4.

Example 4 of che used as a term of address (posted by the Falkand Isands Museum and National Trust).

Figure 5.

Example 1 of che used as a proper name.

Figure 6.

Example 2 of che used as a proper name.

Figure 7.

Example 3 of che used as a proper name.

Figure 8.

Example 4 of che used as a proper name.

Figure 9.

Example 1 of che used as a demonym.

Figure 10.

Example 2 of che used as a demonym.

Some informants mentioned that a group of Islanders is colloquially referred to as “Cheys”. We verified this through social media analysis (see Figure 9) and further confirmed it through the existence of a Facebook group named “Falkland Reunion/Chay’s stop for smoko” (see Figure 10). This group’s description clarifies that:

Chay is one of the ways Falkland Islanders collectively describe themselves. The word chay being derived (some would say bastardised!) from the Spanish word che meaning friend. This is a space for friends old, new, and those we have not met yet! All other groups want one million for this or that. Not this one: it only takes half a dozen Kelpers9 to warm a room. Come in, have a cuppa and tell us where you are and how/why you got there! There are few rules, other than all content should relate to the Falklands, and, having posted a photograph, please help us to retain the historically interesting comments from us ‘oldies’ by never deleting your photos. Some of us may not be around long enough to make the comments again.

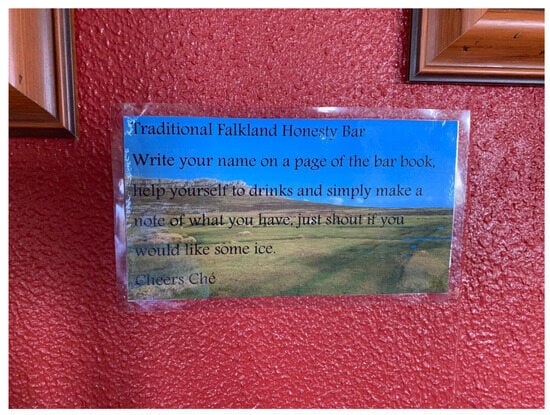

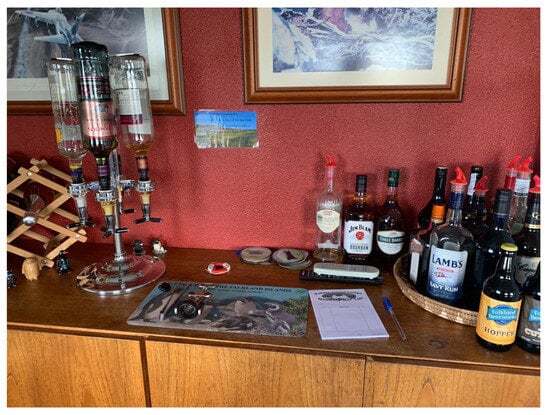

While conducting fieldwork outside Stanley, we documented the use of che at a self-service bar in a bed and breakfast on Pebble Island (West Falkland). The sign reads: “Traditional Falkland Honesty Bar. Write your name on a page of the bar book, help yourself to drinks and simply make a note of what you have, just shout out if you would like some ice. Cheers Ché”. The manager explained that in the Falklands, it is common to toast with a “Cheers, che” (see Figure 11 and Figure 12).

Figure 11.

Example of che used as a vocative in the context of a self-service bar (see Figure 12 for context). Photograph by the first author.

Figure 12.

Sign using che (Figure 11) used as a vocative in the context of a self-service bar. Photograph by the first author.

These examples confirm that in FIE che functions primarily as a vocative, but its use has extended into the nominal domain, where it also serves as a nickname, group label, and symbol of belonging. This functional versatility reinforces its embeddedness in the local speech repertoire and supports its gradual enregisterment as a recognisable marker of Falklands identity. The shift from being a pragmatic vocative to a socially recognisable form aligns with what Johnstone et al. (2006) describe as a local enregisterment process, whereby everyday expressions become ideologically linked to a place and a persona. Furthermore, the examples reveal how che extends beyond interpersonal address into the symbolic domain, functioning as a marker of local identity. Its use in signage and group labels suggests an early stage of enregisterment (Agha, 2007), where the term is increasingly stylised and recognised as emblematic of Falklands identity.

4.2.2. Islanders’ Perceptions of Che

While some regard che as a fading or old-fashioned term, others continue to use it daily or associate it strongly with local identity. These divergent views point to generational shifts and the socially regulated use of the term.

Comments regarding the purported loss of vitality of che are prominent, juxtaposed with assertions that its usage persists as a commonplace occurrence. Some Islanders’ comment on a decline in its frequency of use over time, noting that it is not as prevalent as in previous years (see example i and ii), while others argue the opposite (see example iii). Its usage seems to vary among individuals, with some informants reporting employing it naturally and regularly, while others utilising it in jest. The term predominantly finds resonance among older families or individuals embracing tradition, and reports of its daily occurrence are not uncommon.

- Example i. Not as common as it was (informant 14).

- Example ii. Chey is not used as much as it used to be (informant 2).

- Example iii. I hear it every day (informant 15).

Recollections from childhood underscore its once-frequent usage, now seemingly relegated to a means of humorously mimicking past Islander speech patterns, rather than its original organic application. Conversely, there are voices of dissent, expressing discomfort with the term due to its association with Argentina. This shift aligns with the process of enregisterment (Agha, 2007), wherein linguistic features acquire social and historical connotations, transforming them from unmarked elements of everyday speech into recognisable markers of identity, nostalgia, or parody.

Exploring its etymology and historical context in the Islands unveils intriguing hypotheses. Some informants suggest its derivation as a corruption of a familiar term widely used in Argentina; others attribute its origin to pre-conflict collaborations with the continent.

In participant observations, we have heard individuals in their twenties using the vocative, suggesting the continued usage of the term che. This observation underscores the perpetuation of the expression as a marker of linguistic identity in the Islands. Furthermore, we have also heard children using the word, and teachers coming to work from abroad mentioned feeling puzzled when their students used che.

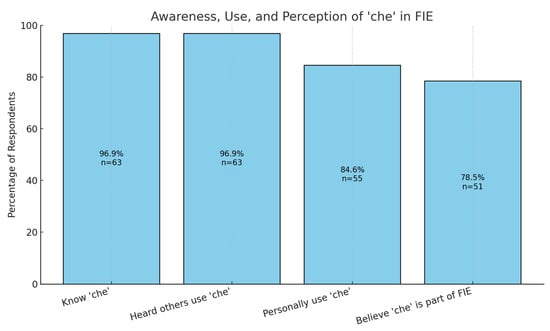

The survey data obtained from 65 respondents, together with their demographics, provides valuable insights into the awareness, perception, and usage of che among Falkland Islanders. The results, visualised in Figure 13, indicate that che is widely recognised in the community, as follows:

- –

- A total of 96.9% of respondents stated that they know the word che, demonstrating its strong presence in local linguistic awareness;

- –

- An identical 96.9% reported having heard others use che, reinforcing its continued presence in Falklands speech;

- –

- A total of 84.6% of participants stated that they personally use che, indicating that while it remains widely used, there is a slight gap between awareness and active use;

- –

- A total of 78.5% of respondents believed that che is part of FIE, showing that while widely known and used, its status as a local feature of speech is not unanimously accepted.

Figure 13.

Awareness, usage, and perception of che in FIE. This figure was developed with the assistance of an AI tool (ChatGPT, OpenAI, 2025).

These figures suggest that che is not only deeply embedded in the local lexicon, but also commonly used in FIE. However, the discrepancy between awareness and usage, with slightly less speakers reporting personal use than those who recognise it, may reflect generational shifts or individual variations in usage patterns. Within that group of speakers, there is a mix of both long-term and very short-term residents, suggesting that the non-use of che may stem from generational factors, as well as individual trajectories in terms of residence and local affiliation.

These findings align with the data obtained from the participant observations and corpus analysis, which suggest that che remains a hallmark of local speech. Moreover, the fact that 96.9% of respondents reported recognising che, and only 84.6% claimed to use it personally, suggests that che may function more as a marker of group recognition than of active linguistic practice among all the residents (like in Rioplatense Spanish).

The survey responses confirm that che continues to function as a widely recognised and actively used linguistic marker, reinforcing its enregisterment as an emblem of Falklands identity.

Perceptions of che reveal both continuity and change: while many Islanders view it as a core element of local speech, others perceive a decline in usage or express ambivalence due to its regional associations. This variation underscores its socially dynamic and context-sensitive nature. The variation in perception reflects the fluid and layered indexicality of the form (Silverstein, 2003), as its meanings shift according to speaker stance, age, and social proximity. The divergent evaluations of che, from affectionate to outdated, illustrate a layered indexical field (Eckert, 2008), in which its social meaning shifts across age groups and contexts. These contrasts suggest that its symbolic value is not fixed, but is negotiated in relation to the speaker’s identity and stance.

The next section further explores how che has evolved beyond everyday oral usage into being a self-aware, stylised feature of local identity, including its recent appearance in regard to commercial products and public discourse.

Despite varying attitudes, che remains closely tied to local identity in the Falklands. Many Islanders describe it as a defining feature of local speech. The analysis also reveals patterns of cautious or excessive use depending on the speaker’s background and social familiarity, underscoring the role of che as a marker of insider status.

Despite diverging opinions, the resonance of che in regard to the Islander identity remains unmistakable, heralded as a hallmark expression and arguably the defining term of FIE. Islanders seem to be identified by this word. We learn this from assertions such as:

- Example iv: It’s a very strong part of our identity (informant 8);

- Example v: (…) by far the most popular phrase (informant 11);

- Example vi: Probably the defining word of FI English! (informant 20);

- Example vii: But I can tell you that almost everyone who is from the Falklands uses the word che to speak to other people (informant 22).

One finding, observed during the participant observations, is the socially regulated use of che. Social etiquette dictates limited use with newcomers, reinforcing che as an insider linguistic marker reserved for familiar interactions. In contrast, long-term foreign residents tend to overuse che, suggesting a process of linguistic assimilation, during which they adopt local speech features, sometimes excessively, as part of their integration into the community.

The data show that che plays a key role in signalling insider status and shared identity, but its usage is socially calibrated, intensified in informal settings and regulated in regard to outsiders. This selective deployment highlights its function as a boundary marker within the speech community. This selective usage aligns with Eckert’s (2008) understanding of style as a locus for the construction of social meaning: che functions as a stylistic resource to index localness and informality, mediated by speaker awareness and contextual appropriateness.

4.2.3. Che and the Process of Enregisterment

Che has become a stylised emblem of Falklands identity, moving from what we supposed was an unmarked oral usage to becoming a highly self-aware, commodified form (see Figure 14). This shift aligns with the process of enregisterment, wherein a linguistic form acquires layered social meanings and symbolic value (Agha, 2007). In other words, an everyday element of speech acquires social, cultural, and historical connotations. This transformation has positioned che not only as a vocative in natural conversation, but also as a symbol of local identity.

Figure 14.

A t-shirt featuring che, highlighting the enregisterment of the term (taken from https://www.thebirdsofwinter.com/).

One key sign of this enregisterment process is the emergence of che in metalinguistic awareness and commercial representations. While historically an oral feature, che has recently begun appearing in written and stylised forms, particularly in merchandising and public discourse. Since 2023, t-shirts featuring playful uses of the word che have been produced and circulated in the Falklands, with phrases like Yes, che (see Figure 14 and Figure 15). These stylised uses highlight how che is being commodified and consciously performed as an emblem of Falklands identity, rather than just serving its original interactional function.

Figure 15.

An Instagram post by local artist and craftsman James Peck, designer and creator of the t-shirts (we were granted permission to post his picture and mention his name).

This shift aligns with other global cases of registered linguistic features, wherein words and expressions transition from casual speech to become deliberate markers of regional belonging. A well-documented example is the case of Scottish English and the enregisterment of Scottish phonological and lexical features (Johnstone et al., 2006; Beal, 2009). Words such as wee (small) and aye (yes) have moved beyond mere vernacular use and have become cultural markers of Scottish identity, appearing in commercial products, tourist campaigns, and media representations of Scottishness. Similarly, in Latin America, Lunfardo, a sociolect of Rioplatense Spanish, has followed a similar trajectory. Originally associated with the working class, Lunfardo expressions, such as laburar (to work), have been reframed as symbols of national and regional identity, appearing in the literature, tango lyrics, and commercialised language resources (Moyna, 2017).

As with other enregistered features, the process of stylisation and commodification also introduces layers of self-awareness and even irony (Coupland, 2007). Some Islanders may view che as an authentic symbol of local speech, while others may perceive its stylisation in merchandise as a parodic or exaggerated performance of Falklands identity. This tension highlights the fluidity of enregisterment, wherein linguistic elements can be embraced, resisted, or reinterpreted depending on the social context and speaker’s perception.

Ultimately, the enregisterment of che in the Falklands contributes to larger discussions on language, identity, and regional distinction. The case of che demonstrates how historically borrowed words can gain new social meanings, shifting from being practical communication tools to symbolic resources that articulate group identity, local heritage, and even commercial value. The growing awareness and stylisation of che suggest that its cultural value is increasing, reinforcing its role as both a linguistic relic of historical contact with Spanish and a contemporary marker of Falklands distinctiveness. These stylised uses not only index group belonging, but they also signal the speaker’s awareness of che as a metapragmatic resource. This reflexivity marks a late stage in the enregisterment process, wherein che becomes a recognised emblem of place-based identity.

Whether its future holds continued everyday use or eventual obsolescence, che stands as a compelling example of how words evolve beyond their original linguistic function to become symbols of place and belonging. Its stylisation in merchandise and media suggests that the term is undergoing enregisterment, evolving from being a spontaneous vocative into a reflexive emblem of Falklands identity. This process mirrors broader patterns observed in other contact varieties and underscores its symbolic value beyond its original use.

5. Conclusions

This study represents a first attempt at systematically examining the vitality, etymology, and borrowing process of che in FIE. By combining survey data, ethnographic fieldwork, corpus analysis, and a literature review, we aimed to shed light on the historical roots, contemporary usage, and sociolinguistic significance of this vocative among residents of the Falklands.

Our findings suggest that even though che primarily functions as a vocative, much as it does in other regions, it also appears in the nominal domain. Just like in Rioplatense Spanish (see Bertolotti, 2010), che is not a homogeneous form; there seem to be instances of its usage that fall within the nominal domain, while others resemble interjections. The data also indicates that che is a distinctive linguistic feature of FIE that reinforces in-group solidarity. However, its use is socially regulated, with newcomers employing it cautiously and some long-term foreign residents overusing it in an apparent process of linguistic assimilation. Additionally, we observed signs of enregisterment (Agha, 2007), whereby che has moved from being an everyday, unmarked feature of speech to one associated with local identity, nostalgia, and even parody.

Regarding its origin, our study argues that che entered FIE through 19th century contact with Rioplatense Spanish, irrespective of its ultimate origin within it. While che is still widely recognised, perceptions of its vitality vary among speakers, with some reporting a decline in frequency and others attesting to its continued presence in everyday interactions. This suggests that its use is socially and generationally dynamic, shaped by broader linguistic and cultural shifts.

As a preliminary study, this work has provided an initial exploration of che in FIE, but there remains much to be investigated. Future research could expand on the phonetic and pragmatic aspects of che, analyse its variation across different social groups, and further explore Spanish influences on FIE. More broadly, studying che in FIE contributes to discussions on language contact, lexical borrowing, and identity in small, multilingual and isolated communities.

Ultimately, while this study does not claim to offer a definitive account, it provides a starting point for understanding che as a linguistic emblem of the Falklands, reflecting the historical, social, and cultural interactions that continue to shape the Islands’ speech community.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.V.R. and M.B.; methodology, Y.V.R.; formal analysis, Y.V.R.; investigation, Y.V.R. and M.B.; resources, Y.V.R. and M.B.; data curation, Y.V.R.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.V.R.; writing—review and editing, Y.V.R. and M.B.; visualization, Y.V.R.; supervision, Y.V.R.; project administration, Y.V.R.; funding acquisition, Y.V.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the British Embassy in Montevideo, the Falkland Islands Government, the Shackleton Fund, the Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office, and the Comisión Sectorial de Investigación Científica of the Universidad de la República.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Humanities of Universidad de la República on 12 December 2019.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from informants.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical considerations. Given the small and close-knit population of the Falkland Islands, even anonymised qualitative data—such as interview excerpts or detailed linguistic observations—could inadvertently lead to the identification of individuals. To protect participant anonymity and uphold ethical research standards, access to the data is restricted. Researchers with a justified interest in the dataset may contact the corresponding author to discuss potential limited access under strict confidentiality agreements.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the audience of the II International CROS Conference 2024, where we first presented our data and preliminary analysis, and to the two anonymous reviewers for their insightful feedback and constructive suggestions. Figure 13 was developed with the assistance of an AI tool (ChatGPT, OpenAI, 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Rioplatense Spanish is the variety of Spanish spoken primarily in the Río de la Plata basin, encompassing the metropolitan areas of Buenos Aires (Argentina), Montevideo (Uruguay), and surrounding regions. |

| 2 | The argot spoken by Spanish-speaking gauchos. |

| 3 | See Rodríguez et al. (2023) for an elaboration on the semantic fields these words belong to. |

| 4 | The data is available upon request from the first author. |

| 5 | We opted for the “chey” spelling given that it is the most common form used in FIE. |

| 6 | See note 4. |

| 7 | See note 4. |

| 8 | Accessed on 3 February 2025. Translations of the text from the Diccionario de la Lengua Española and the Diccionario de Americanismos were carried out by the authors of this work. |

| 9 | Kelper is one of the terms used in the Falklands to describe native Islanders. |

References

- Abeille, L. (2005). Idioma Nacional de los argentinos. Biblioteca Nacional/Colihue. First published 1900. [Google Scholar]

- Agha, A. (2007). Language and social relations. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Beal, J. (2009). Enregisterment, commodification, and historical context: ‘Geordie’ versus ‘Sheffieldish’. American Speech, 84(2), 138–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beccaceci, M. (2017). Gauchos de Malvinas. South World. [Google Scholar]

- Bertolotti, V. (2010). Notas sobre el che. Lexis, 34(1), 57–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolotti, V. (2015). A mí de vos no me trata ni usted ni nadie. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México/Universidad de la República. [Google Scholar]

- Bertolotti, V., & Coll, M. (2014). Retrato lingüístico del Uruguay. Un enfoque histórico sobre las lenguas en la región. Facultad de Información y Comunicación, Universidad de la República. [Google Scholar]

- Blake, S., Cameron, J., & Spruce, J. (2011). Diddle dee to wire gates: A dictionary of falklands vocabulary. Jane & Alastair Cameron Memorial Trust. [Google Scholar]

- Borzi, C. (2016). El che argentino: Sus contextos de uso y su significado. Philología Hispalensis, 30(1/2), 9–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boumphrey, R. S. (1967). Place-names of the Falkland islands. The Falkland Islands Journal. [Google Scholar]

- Britain, D., & Sudbury, A. (2010). Falkland Islands English. In D. Schreier, P. Trudgill, E. W. Schneider, & J. P. Williams (Eds.), Lesser-Known varieties of English: An introduction (pp. 209–223). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, P., & Levinson, S. C. (1987). Politeness: Some universals in language usage. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, R., & Gilman, A. (1960). The pronouns of power and solidarity. In T. A. Sebeok (Ed.), Style in language (pp. 253–276). MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Coupland, N. (2007). Style: Language variation and identity. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- De Marsilio, H. (1969). El lenguaje de los uruguayos. Nuestra Tierra. [Google Scholar]

- Eckert, P. (2008). Variation and the indexical field. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 12(4), 453–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, R. M., Fretz, R. I., & Shaw, L. L. (2011). Writing ethnographic fieldnotes (2nd ed.). University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fitz Roy, R. (1839). Narrative of the surveying voyages of his majesty’s ships adventure and beagle. Henry Colburn. [Google Scholar]

- Government of the Falkland Islands. (2021). Census report. Available online: https://www.falklands.gov.fk/policy/downloads?task=download.send&id=219:falkland-islands-2021-census-report&catid=13 (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Guber, R. (2001). La etnografía. Método, campo y reflexividad. Siglo XXI. [Google Scholar]

- Johnstone, B., Andrus, J., & Danielson, A. E. (2006). Mobility, indexicality, and the enregisterment of “Pittsburghese”. Journal of English Linguistics, 34(2), 77–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiesling, S. F. (2004). Dude. American Speech, 79(3), 281–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leech, G. (1999). The distribution and function of vocatives in American and British English conversation. In H. Hasselgård, & S. Oksefjell (Eds.), Out of corpora (pp. 107–118). Rodopi. [Google Scholar]

- Leech, G. (2014). The Pragmatics of politeness. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lenz, R. (1904). Diccionario etimolójico de las voces chilenas derivadas de las lenguas indíjenas americanas. Imprenta Cervantes. [Google Scholar]

- Meyerhoff, M. (2012). Uncovering hidden constraints in micro-corpora of contact Englishes. In Corpus linguistics and variation in English (pp. 109–130). Brill Rodopi. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, S. (2003). Gender and politeness. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Moyna, M. I. (2017). Voseo vocatives and interjections in Montevideo Spanish. In J. Colomina-Almiñana (Ed.), Contemporary advances in theoretical and applied Spanish linguistic variation (pp. 124–147). The Ohio State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pascoe, G., & Pepper, S. (2008). Getting it right: The real history of the Falklands/Malvinas: A reply to the Argentine. [Seminar of 3 December 2007]. Available online: http://www.wildisland.gs/atlantis/gettingitright.pdf (accessed on 16 January 2024).

- Real Academia Española. (2010). Diccionario de americanismos. Available online: https://www.asale.org/damer (accessed on 23 January 2024).

- Real Academia Española. (2023). Diccionario de la lengua española (23rd ed.). Available online: https://dle.rae.es (accessed on 11 August 2024).

- Resnik, G. (2024). Acerca de che en español rioplatense: Una aproximación gramatical. Quintú Quimün. Revista De lingüística, 8(1), Q093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, G. (2002). Origins and associations of Spanish words in the Falklands islands up to 1950. Falkland Islands Journal, 8, 32–51. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, Y. V. (2022). Spanish-English contact in the Falkland islands: An ethnographic approach to loanwords & place names [Ph.D. dissertation, Leiden University]. Available online: https://www.lotpublications.nl/spanish-english-contact-in-the-falkland-islands (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Rodríguez, Y. V., González, P., & Elizaincín, A. (2023). The Spanish component of Falkland Islands English. English World-Wide, 44(1), 118–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rona, J. P. (1963). Sobre algunas etimologías rioplatenses. Anuario de Letras, 3, 87–106. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblat, A. (1962). Origen e historia del «CHE» argentino. Universidad de Buenos Aires, Facultad de Filología y Letras, Instituto de Filología y Literaturas Hispánicas Dr. Amado Alonso. [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein, M. (2003). Indexical order and the dialectics of sociolinguistic life. Language & Communication, 23(3–4), 193–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spruce, J. (1992). Corrals and Gauchos: Some of the people and places involved in the cattle industry. Falklands Conservation Publication. [Google Scholar]

- Strange, I. (1973). Introduction of stock to the Falkland Islands. The Falkland Islands Journal. [Google Scholar]

- Sudbury, A. (2001). Falkland Islands English: A southern hemisphere variety? English World-Wide, 21(1), 61–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudbury, A. (2005). Social networks and the spread of linguistic features: The case of the Falkland Islands. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 9(3), 305–322. [Google Scholar]

- Trudgill, P. (1986). Dialects in contact. Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Wells, J. C. (1982). Accents of English. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zwicky, A. (1974). Hey, whatsyourname! In M. La Galy, R. A. Fox, & A. Bruck (Eds.), Papers from the tenth regional meeting of the Chicago linguistics society (pp. 787–801). CLS. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).