1. Introduction—What Is Humor, and How Do Humans Recognize It?

Man is the only animal that laughs and weeps: for he is the only animal that is struck with the difference between what things are, and what they ought to be.

--William Hazlitt “On Wit and Humor” (Hazlitt, 1819, p. 5)

“There is always something to upset the most careful of human calculations.”

--Saikaku Ihara

The basic question addressed in this paper is simply stated but difficult to understand because of its complexity. It is a question I addressed some years ago in a paper titled “Why Do They Laugh (

Beeman, 1981)”. The questions remain: How does anyone in a given society know when something is funny, and how do people who want to engage in humorous communication move through behavioral and cognitive stages in a process to reach the ultimate goal of humor—to induce autonomic, spontaneous laughter, a convulsive physiological reaction that is universally enjoyed and valued by all humans.

To engage with this question, I will be using some of the tools developed in pragmatic communications research—primarily, the concepts of modality, psychological framing, Ba Theory, and the concept of pragmemic triggering. Modality is the sense in which a communication is intended to be understood. Psychological framing sets up the conditions for the production of humor. Ba Theory explains why people sharing a unity of consciousness can understand humor within their sphere of communicative understanding. Pragmemic triggers are the pragmatic tools that advance people through the process of humorous communication to spontaneous laughter.

I maintain that, although it is difficult for people who come from different cultural and social backgrounds and are therefore embedded in different ba spheres to understand each other’s humor, nevertheless, the process of humor formation and advancement to laughter has a universal pragmatic structure.

To this end, I provide comparative descriptions of humor production from four different linguistic communities—Japanese, Chinese, Arabic/Middle Eastern, and German. I also reference English language humor, particularly American humor, to provide a baseline for the discussion.

2. Humor—Modal Performative Communication: The Ludic Mode

Humor is one of the uniquely human dimensions of behavior. Others are prevarication (lying) and music. Because humor is one of these uniquely human behavioral activities, it has been the subject of research and speculation since the beginning of recorded history.

All these forms of uniquely human behavior

are performative.

are accomplishments.

are enacted in a processual manner.

are deemed to succeed when they produce an altered emotional state in participants.

must be enacted by actors in conjunction with consumers, who are observers and participants the humorous event as co-creators.

Because humor is a form of communication, it is modal in nature. The term “modality” has been used to describe the indication of the attitude of a speaker toward the verbal elements expressed in an utterance or other communicative form. Lyons elaborated on this, stating that modality is “having to do with possibility or probability, necessity or contingency, rather than merely with truth or falsity” (

Lyons, 1970, p. 322).

Modality is intentional. The speaker of a communication has the performative task not only of conveying information but also of making the nature of the attitude intended toward the communication manifest to consumers.

Modal logic is a type of formal logic that allows for formal analysis of the qualification of expressions beyond that which are covered in traditional propositional and predicate logic. Modal logicians have classified these kinds of modal expressions in a variety of categories, as shown in

Table 1 below.

Modality is conveyed through a wide variety of linguistic structures. These include virtually every part of speech:

nouns (chance, hope, expectation);

adjectives (conceivable, possible, likely, necessary);

adverbs (perhaps, possibly, regrettably);

verbal structures (doubt, think, believe, predict);

modal subjunctives (shall, will, would, could, may, might, must, etc.).

In previous papers, I have discussed modality in language as an important element for conveying emotion and social attitude in interactions (

Beeman, 2015a). More importantly for this discussion, humor as a modality in inspiring a change in emotional state in others in the case of humor resulting in a spontaneous reaction—laughter. To this end, I am suggesting that we might consider another category of modality:

ludic to indicate that the communication is to be understood as playful and directed toward producing a humorous reaction.

Discussions of modality have largely been limited to textual analysis and highly focused on Western languages and grammatical structures. However, modal expression involves a much broader palette of human behavior than verbal expression. To convey the intent, tone, and feeling of an expression, performative dimensions must also be included. “Ludic” modality is an ideal way to explore this communicative function. Creating expression that is intentionally humorous, that aims to produce a spontaneous reaction, is fully akin to the classic modal functions producing hesitation, doubt, possibility, hope, and other emotional responses between communicators. Therefore, in this way, I propose that ludic modality is an ideal embodiment of a “modal performative task” that humans accomplish in interacting with each other.

The “modal performative task” then, for speakers who wish to create humor, is, first, how to indicate that they are communicating in a humorous fashion—a ludic mode. Then, how to performatively create the communicative conditions that will induce consumers of a message to understand that the message is supposed to be humorous. Finally, to guide those consumers through the process of arriving at the point in communication where spontaneous laughter is evinced.

However, for both the initiator of a humorous communication and the receivers of a humorous communication to be able to accomplish the movement toward laughter, they must be able to mutually carry out that communication within a unified framework of understanding and shared meaning. This common unified framework is expressed by the concept of

ba (

Beeman, 2017;

Dilworth, 1970;

Nishida, 1965,

2012;

Nonaka et al., 2000;

Ohtsuka, 2011;

Shimizu, 1995). This shared understanding extends not only to the understanding of the concepts within humor but also shared understanding about the process of creation of the humorous event. This shared understanding is, by its nature, based on common cultural understandings between participants in humor events.

It is this process that will be the primary focus of this discussion. P describe the process of its execution within psychological frames in stages that move (

Peterson & Seligman, 2004, 583 ff.) performatively from a state where there is no humorous communication to the initiation of the communication event, proceeding through states until the spontaneous emotional reaction of laughter is produced. I describe the stages in this process as proceeding according to the mechanism of “pragmemic triggers”—pragmatic communicative signals that move participants through the stages of any social process. I have discussed pragmemic triggers elsewhere (

Beeman, 2015a;

Szatrowski, 2014).

Because this paper deals with humor on a pan-human scale, I have adopted a comparative approach to humor traditions in four different cultural traditions. It is surprising that this comparative research has rarely been produced in this area. However, this approach has been very fruitful, since, as will be shown, the basic structures of humor production are highly uniform across cultures, though the content of humor may be quite different.

3. Laughter—The End Goal of Humor

Humor as a communication modality has the unique purpose of producing an altered, emotional state that is marked most commonly by a highly pleasurable physiological reaction—laughter. This behavior is unique to humans. Bateson identifies this as one of three common human spontaneous autonomic “convulsive” behaviors, “… the others being grief and orgasm (

Bateson, 1952, p. 2)”. The other source of this convulsive behavior—laughter—is tickling. The curious and suggestive fact, noted by Darwin and others back through antiquity, is that humans cannot tickle themselves (

Hall & Alliń, 1897;

Milner, 1972;

Weiskrantz et al., 1971). I would also submit that one cannot make oneself laugh through humor. Both tickling and humor can only produce laughter in a human in conjunction with the actions of others.

Humans value laughter and laughter production universally. It has high evolutionary value, since people who can induce laughter in others and people who respond easily to humor are viewed positively by others (

Reysen, 2006). The ability to create humor and induce laughter in others renders potential romantic partners more attractive to each other (

Bressler et al., 2006)

1. It is protective as well, since it produces a calming effect in conflict and awkward social situations (

Beeman, 1981;

Kakalic & Schnurr, 2021;

Mullan & Béal, 2021;

Obialo, 2021;

Peterson & Seligman, 2004, pp. 583–598;

Steir-Livny, 2021).

Here is what happens when one laughs as described by cardiologist Rachel Hajar:

Laughter relaxes the whole body. A good, hearty laugh relieves physical tension and stress, leaving your muscles relaxed for up to 45 min after.

Laughter boosts the immune system. Laughter decreases stress hormones and increases immune cells and infection-fighting antibodies, thus improving your resistance to disease.

Laughter triggers the release of endorphins, the body’s natural feel-good chemicals. Endorphins promote an overall sense of well-being and can even temporarily relieve pain.

Laughter protects the heart. Laughter improves the function of blood vessels and increases blood flow, which can help protect you against a heart attack and other cardiovascular problems.

Laughter burns calories. One study found that laughing for 10–15 minutes a day can burn approximately 40 calories–=which could be enough to lose three or four pounds over the course of a year.

Laughter helps you stay mentally healthy. Laughter makes you feel good. Moreover, this positive feeling remains with you even after the laughter subsides. Humor helps you keep a positive, optimistic outlook through difficult situations, disappointments, and loss.

Other research shows that laughter produces a pleasurable state only when it is spontaneous and autonomic. “Forced” laughter is neither pleasurable for the person exhibiting it nor for the person attempting to induce it. The positive social and health benefits of laughter seem only to be produced when it is spontaneous (

Szameitat et al., 2022).

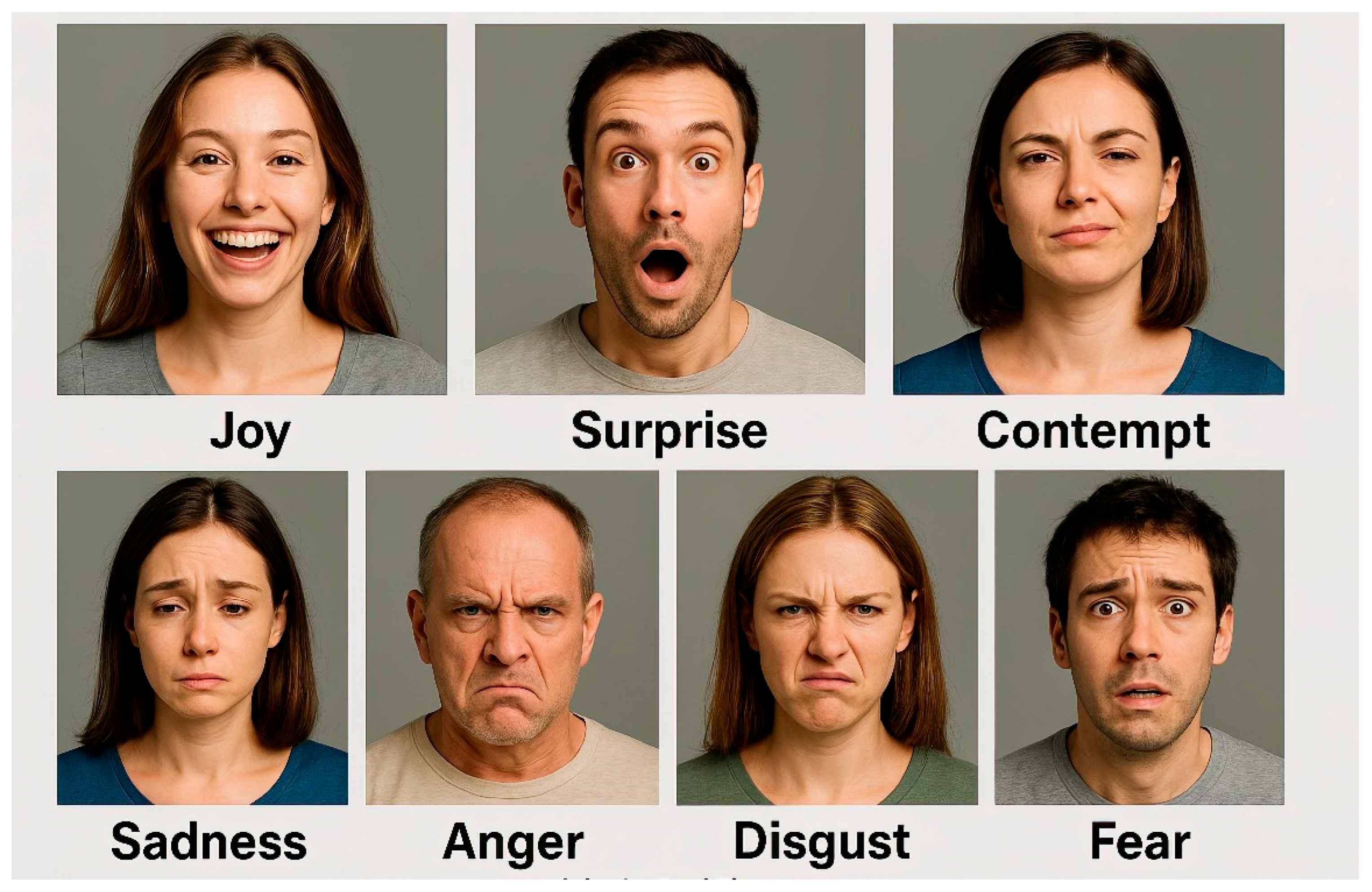

Laughter is pleasurable as a form of convulsive physiological reaction, because it appears to play on a combination of positive human basic emotional reactions that are physically activated during a humorous event. Basic underlying emotions for human beings are fear, anger, contempt, disgust, sadness, joy, and surprise (

Ekman, 1999,

2003a,

2003b) as shown in

Figure 1. Each emotion is associated with distinct autonomic physiological reactions. The activation of the autonomic physiological responses associated with laughter appears to be a combination of joy and surprise. When joy and surprise are simultaneously activated, it produces the pleasurable response of autonomic laughter that humans find so desirable.

The discussion below will examine the mechanisms through which humor is accomplished, including the creation of conditions that succeed in being “funny” and produce laughter as a desired and desirable convulsive reaction.

4. Framing

All communicative acts are “psychologically framed” behavior. Psychological framing is now an established concept in describing how humans segregate specialized activities from the background of everyday reality. Pioneers in the development of this concept include

Schuetz (

1945),

Bateson (

1955,

1956), and, more recently,

Goffman (

1974). More recent work specifically dealing with linguistic and communicational aspects of framing has been presented by

Beeman (

1981,

2010,

2015a,

2017),

Tannen (

1993),

Coulson (

2001), and

Ritchie (

2005)

Frames are complex psychological structures.

Bateson (

1952,

1955,

1956) presented “play” and “games” as exemplary examples of framing. Periods of play and games are cognitively bounded. They have clear starting points and end points. Between the starting and ending points, the rules and procedures of the background reality against which the frame exists are suspended, and special rules and procedures of behavior are observed. When a period of play or a game concludes, the rules of the background reality are reasserted.

Thus, there are several components to framed behavior. The first is the general social/cultural background within which framed events are recognized. The second is the framed event itself, and the third is the set of rules and procedures that inhere within the frame. Once again, play and games provide a good example. If one is going to play a game—say, chess—there first must be a social/cultural environment of shared understanding within which chess is recognized as a play activity, a game. Then, there must be a recognized occasion or environment where the chess game can take place. Finally, there must be a shared understanding on the part of the participants in the game about their relative roles, and the rules of the game, including the rules for beginning and ending the Bagame, and proper behavior within the game. Even people who know chess well are sometimes surprised to learn that there are slightly variant rules for chess in different countries that affect the course of play.

I use the term “background reality” here in order to highlight the fact that humans are capable of cognitively sustaining multiple embedded frames. Given attention and memory limitations, the number of possible embedded frames seems to be “The Magical Number 7 (plus or minus 2)”. This is in accord with psychologist

George A. Miller’s (

1956) study on human short-term memory capacity, which demonstrated that humans have a limit on the number of items they can hold in short term memory (7 plus or minus 2) without special training (

Dean, 2023;

Miller, 1956). This allows for the kinds of multiple realities identified by

Schuetz (

1945).

The concept of psychological framing is essential to the creation of humor. Because humor depends on the ability of humans to recognize “double framing” in the construct of a humorous communication or event. In humor, the “double (or multiple) frame” is essential in creating the laughter response. An initial frame is established by the person creating the humorous communication; as the communication proceeds, a second frame is established. Finally, at one point, the first frame is “broken”, revealing the simultaneous second frame. The combination of surprise and joy produces laughter as a spontaneous autonomic physiological reaction.

5. Ba Theory and the Accomplishment of Humor

Freud, in his classic work

Jokes and Their Relation to the Unconscious (

Freud, 1905), posited that humor, which he calls “the most social of all mental functions that aim at a yield of pleasure”, requires common understanding between individuals. He suggests that it may be necessary to have at least three participants: an initiator, a receiver, and an audience. Essential is “intelligibility”, which Freud sees as binding on the humor creation process (

Freud, 1905, p. 179). Freud’s observation that humor is a “social” communication accomplishment is directly relevant to the analysis in this discussion utilizing performance and the “common understanding” that underlies Ba Theory.

Psychologist Martin Lampert and rhetorician Susan Ervin-Tripp elaborate on Freud’s notion of the concomitant requirements for successful humor production in stating the conditions for the successful execution of a joke:

When a joke successfully serves as a source of pleasure for both tellers and audiences, it does so, not only because of its clever or playful nature, but also because it allows tellers through their presentation and audiences through their laughter to indicate that they share common attitudes and beliefs centered around the joke’s theme. Conversely, when jokes fail, they can do so not because of a lack of cleverness or ingenuity, but rather be-cause of an absence of a shared attitudinal or knowledge base between interactants.

Freud, Lampert, Ervin-Tripp, and other commentators on humor have had difficulty in specifying the nature of this common understanding requisite for successful humor production in any but the most general terms. This is where Ba Theory can be enlightening.

Kitaro Nishida laid the foundations for the development of Ba Theory 場の理論

ba no riron in his pioneering work on the concept of

basho (場所) [“place”, or “field”] to embody a context in which knowledge, understanding, and emotion can be shared (

Nishida, 1965; commentary by

Dilworth, 1970). As Professor Masayuki Ohtsuka succinctly stated, Ba 場 (lit. “shared space, place, or location” but also “setting, scene, and context”) is characterized by the idea of non-separation of subject and object and non-separation of the self and the other (

Ohtsuka, 2011)”. Emphasis is placed on the sharedness of the space or context that unites all the elements within it.

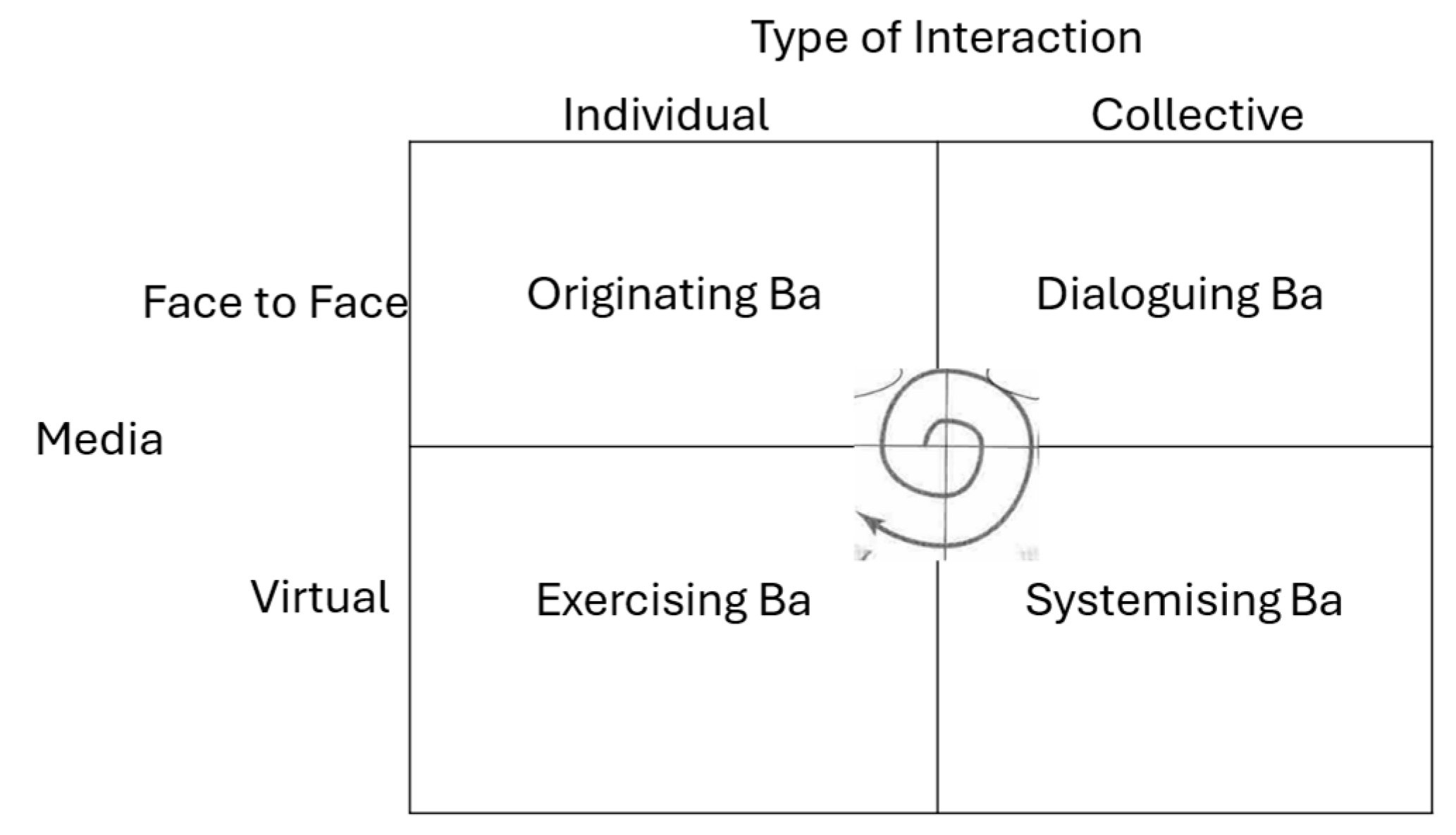

Professor Ikujiro Nonaka and his colleagues, Toyama and Konno (

Nonaka et al., 2000;

Nonaka & Konno, 1998), see the Ba concept as intrinsic to the creation of knowledge. In an influential paper from 1998, he and Noboru Konno speculated that there are four types of Ba that lead to knowledge creation through shared creative processes. The characterization of these types was modified in

Nonaka et al. (

2000). These are Originating Ba, Dialoging Ba, Exercising Ba, and Systemising Ba, illustrated in

Figure 2. These manifestations of Ba are seen as related to each other, depending on whether communication is face-to-face and individual (Originating), face-to-face and collective (Dialoguing), virtual and person-to-person (Exercising), or virtual collectively (Systemising). The authors above emphasized the importance of understanding that Ba is not a unitary state but manifests in many forms, depending on the context in which it is realized. This is the basic postulate that leads to understanding primary and secondary Ba as developed by

Hanks et al. (

2019), as discussed below.

Although Ba may be seen as a feature of the interconnectivity of the natural world, it is an accomplishment for individuals to enter this relationship with each other. Moving toward the Ba state with others is a process that must be accomplished through mutually achieved linguistic and social behavior. For Professor Nonaka, this is the primary process of entering Ba relationships that lead to knowledge creation. Of particular interest is his assertion that, to share feelings, emotions, experiences, and mental structures, “Physical and face-to-face experiences are the key …”. (

Nonaka & Konno, 1998, p. 46).

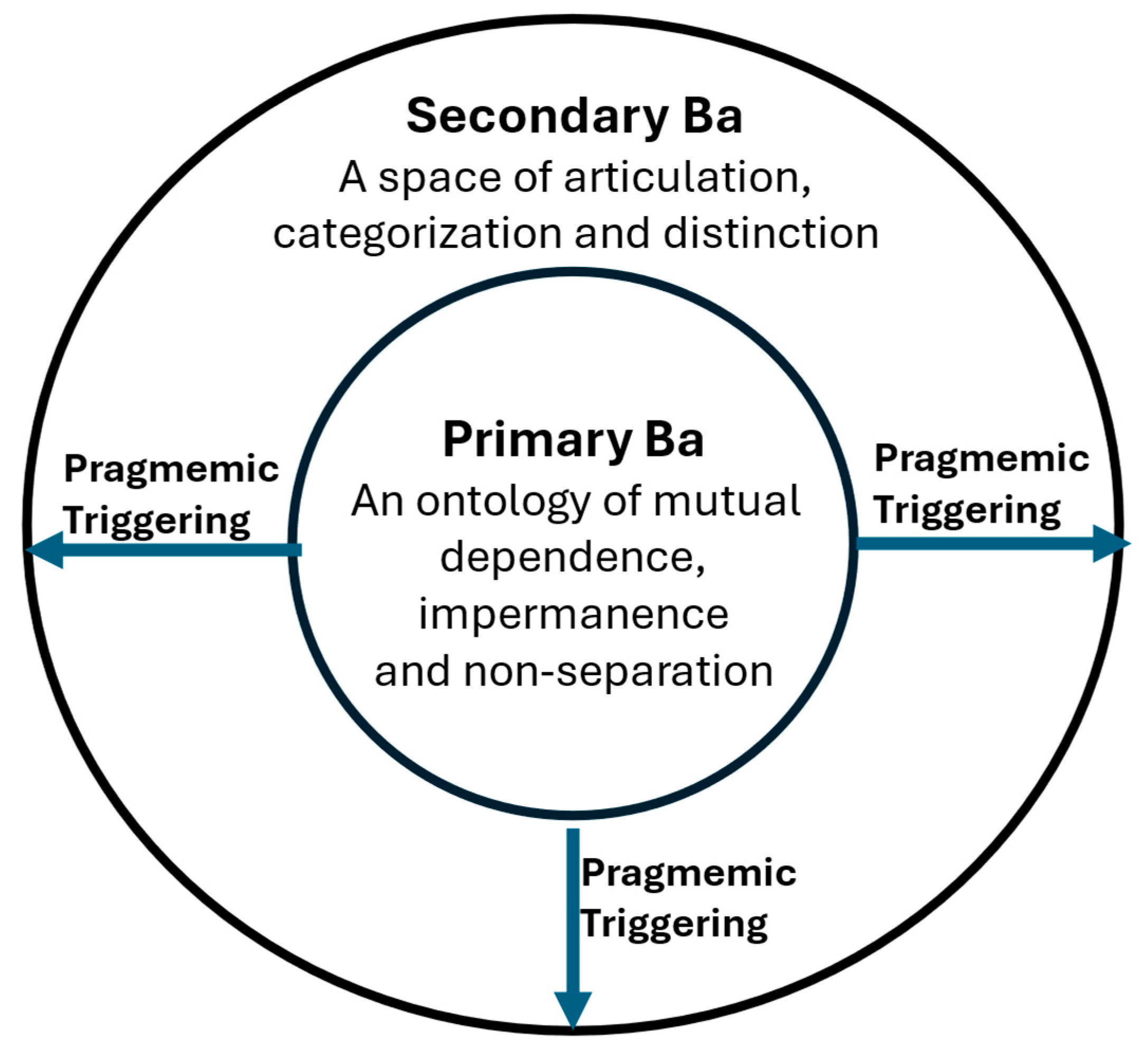

Hanks et al. emphasized this dynamic aspect of Ba in making a distinction between “primary” and “secondary” Ba following

Nishida (

2012)

3. Primary Ba is “… an ontology of mutual dependence, impermanence and ultimately non-separation… a level of nonseparation that is ontologically prior to the subject-object distinction (see also

Hanks, 2022, p. 4;

Hanks et al., 2019, p. 64)”. Secondary Ba is “a space of articulation, categorization, and distinction (

Hanks et al., 2019, p. 65)”. They continue: “Language and social practice produce distinctions, divisions, hierarchies and objects of many kinds (

Hanks et al., 2019).

4”

The distinction made between primary and secondary Ba is a figure/ground relationship, where persons in social interactions have both figure and ground solidly within their shared consciousness and play the distinctions in “secondary Ba” against the ground of “primary Ba” to generate social interaction. Ide utilized this understanding to analyze polite behavior, known as

wakimae (弁え/わきまえ) in Japanese. The word

wakimae is subtle in its meaning, but as Ide pointed out, the closest term in English is ‘discernment’ (

Ide, 1989, p. 230), a most interesting gloss, because it demonstrates that interactants understand the social and cultural distinctions between them: their roles in the interaction, their relative status, and their personal relationships construct their interaction according to their shared understanding of how this interaction should proceed. The resulting interaction in Japanese typically employs honorifics, which Ide pointed out are functional in acknowledging the status difference between the speaker and the referent (

Ide, 1989, p. 231). The resulting

wakimae interaction is a performative collaborative communication event.

Nonaka, Toyama, and Konno (

Nonaka et al., 2000) showed the interaction between primary- and secondary-type shared knowledge not as a static relationship of shared meaning and understanding but equally as a dynamic shared process in creating knowledge as in

Figure 3.

Nonaka et al. described Ba as a platform for knowledge creation—the “ontology of relatedness” paired with a dynamic interactive process combined with “separation, individuation, reification, representation, and hierarchy”.

Hanks et al. (

2019) elaborated on this, emphasizing the process through which individuals work together under shared understanding of the social process.

6. Ba and the Construction of Humor—Performative Acts

I posit that Ba is equally a platform for the dynamic creation of humor as in the execution of a joke or other humorous communication. This is also to say that a joke or humorous communication is a form of co-created knowledge. However, to proceed, it is necessary to understand that the creation of humor is a performative act. The role of Ba Theory in understanding performance was recently explored in Coker, Kajimaru, and Kazama’s recent collection,

An Anthropology of Ba, in which a variety of studies of performance are explored using Ba Theory (

Coker et al., 2021).

Kajimaru, Coker, and Kazama (in that order) in their Introduction to their volume (

Kajimaru et al., 2021) extended the notion of ba to performance events in which they assert that “ba is not simply a passive container but instead an active and even creative force in social relations and cultural histories” and, earlier in the same passage, “in the improvisatory drama model, if the

ba is the whole of that event, it includes the material theater, props and sets, the actors and the audience, as well as the cultural content of ‘the theatre’ … (see also

Beeman, 2015b for an additional analysis;

Kajimaru et al., 2021, p. 11)”.

The transition between primary and secondary Ba, as articulated above, is the essence of this performative action. From the basis of primary Ba, mutual understanding, actors, through language, narrative, gesture, physical arrangement, and illustration, bring participants to a mutual comprehension of secondary Ba, and the sign of this is the spontaneous laughter that results from successful humorous communication. This process is an accomplishment. People cannot be brought to the spontaneous realization that generates laughter, an indication of transition into a secondary Ba state, without conscious effort on the part of an actor.

Jokes and other humorous performative communications are likewise speech acts. They have a direct effect on listeners—generally to elicit a spontaneous reaction. To function, jokes and other humorous communication must fulfill a number of performative criteria. These can be likened to “felicity conditions”, as posited by John Austin in his classic work

How to Do Things with Words (

Austin, 1962). Like all other speech acts identified by Austin and others using his model, felicity conditions necessary to achieve a humorous effect and bring the audience to a release include the sharing of basic cultural understandings between participants in the event and also the mutual ability to distinguish between a humorous speech event and “ordinary reality”. These performative criteria center on the successful execution of the stages of humor creation.

In talking about the construction of humor as performance, I would like to expand on the notion of primary and secondary ba as applied to performance and suggest that, for most, if not all, communication events, there are many framed embeddings of ba in creating a successful humorous event, referring back to

Figure 3. Starting with “primary Ba” as the broadest framing, participants in any communication event share broad cultural understandings. These are the first and most important set of felicity conditions for the success of humor. They have a common language, they are aware of the social and cultural environment in which they live, and they share common understandings about social life as they are experienced by each other.

These “primary Ba” shared understandings will be different for different configurations of relationships. For example, adults may share broad social and cultural understandings with children but have a different configuration of understanding with other adults. Family members will share a set of common understandings among themselves that are different than those they share with those outside the family.

Secondary Ba as framed behavior then applies, as Kajimaru et al. posited, to communicative events. It can then be likened to what Hymes termed as a “speech event (

Hymes, 1974, p. 52)”—a culturally marked framework within which participants have a shared understanding of what kind of communication is likely to occur and also, in general, the socially agreed upon conventions for actors within that secondary ba frame. These secondary ba considerations also constitute a second set of felicity conditions essential for the success of humor production.

The execution procedures of the expected communicative activities are then embedded within the secondary Ba event. In this, as stated above, are specified actors and observers/audience, setting, scene, source of contact between participants, and communicated message (as adumbrated by Jakobson, 1960 in his analysis of communication events). All of these factors can be described ethnographically, as in Coker et al.’s anthology. The individual elements to which an analyst needs to pay attention have been described extensively in research on the “ethnography of communication” (

Bauman & Sherzer, 1974;

Gumperz, 1982;

Gumperz & Hymes, 1964,

1972).

The construction of humor, as stated above, is performative and purposeful. The end goal is to induce laughter. People engaged in this kind of communication event first share the cultural understandings necessary to comprehend that a humorous communication is taking place. Then, they share the conventions of humor creation. Finally, they know how to participate in the mutually constructed process of the humorous communicative event.

7. Stages of Humor Construction—Pragmatic Processes

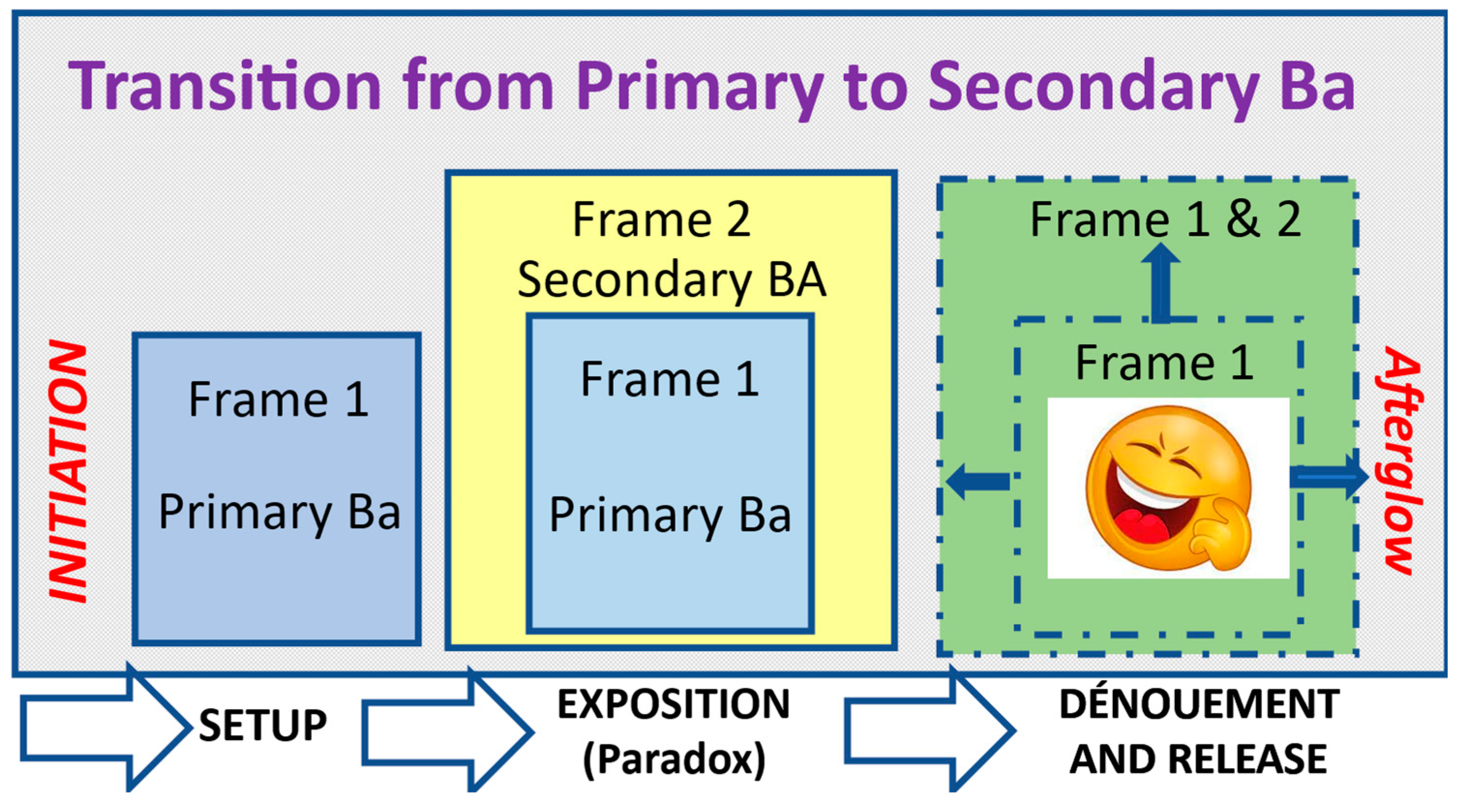

The balance of this discussion focuses on the pragmatic process through which participants in humorous communication pass through stages of mutually understood behavior to reach the endpoint of induced laughter. This represents the transition from primary Ba to a secondary Ba state. The mechanism for this movement from the point of inception of the humorous event to laughter proceeds in stages, and movement between those stages is signaled by the mechanism of “pragmemic triggers” described below.

In ritual, there is a point of transition or transformation where a participant or participants achieve a different state or identity from before the ritual began. In humor, participants also reach a point of transition or transformation that is identified, as I have said, by spontaneous laughter. Just as there are event stages in ritual, humor also has stages. The participants are co-involved in the setting up of pragmemic triggers to mark a sudden transition to a surprise or series of surprises for an audience, creating a laughter response.

The most common kind of surprise has been described since the eighteenth century under the general rubric of “incongruity” (

Morreall, 2020, pp. 15–25). Basic incongruity theory as an explanation of humor can be described in linguistic terms as follows:

A communicative actor presents a message or other content material and contextualizes it within a cognitive “frame”, incorporating a ludic modality of communication.

The actor constructs the frame through narration, visual representation, or enactment.

The actor then advances the narrative by embedding the original frame into subsequent frames, moving the “audience” for the humorous event into the embedded frame structure using pragmemic triggering devices.

Some jokes involve a kind of “triple framing”. Incongruity is introduced in the original setup by a narrator, such as “a panda walks into a bar …” (to be explored below). As the narrative proceeds, the listener is gradually introduced to the paradox. The narrator then suddenly pulls this frame aside using the pragmemic trigger of the dénouement, revealing one or more additional simultaneous cognitive frames, which audience members are shown as possible re-contextualization or re-framing of the original content material. The tension between the original framing and the sudden reframing results in an emotional release recognizable as the enjoyment response we see as spontaneous and autonomic smiles, amusement, and laughter—the combination of surprise and happiness cited above as basic emotions. This tension is the driving force that underlies humor, and the release of that tension—as Freud pointed out—is a fundamental human autonomic behavioral reflex

5.

Humor, of all forms of communicative acts, is one of the most heavily dependent on equal cooperative participation of actor and audience. The audience, to enjoy humor, must “get” the joke. They must subject themselves to pragmemic triggering. This means they must be capable of analyzing the cognitive frames presented by the actor and following the pragmemic process of the creation of the humorous event.

Codifying the process of creating incongruity, we see that humor typically proceeds in five stages:

Initiation of the humorous communication event—signal of a departure from the background world of social meaning.

First framing: the setup,

Second framing: Exposition creating a paradox,

Breaking of the two frames: the tension of dénouement,

Reaction: the release.

The “afterglow” of enjoyment and return to the background social world.

The

initiation signals that a humorous communication is about to take place, opening the frame. The

setup involves the presentation of the original content material and the first interpretive frame. This is the primary Ba state, where all parties have a common frame of understanding. The

paradox involves the construction of an additional frame or frames through exposition. These represent the secondary Ba state. The audience or consumer is usually unaware of this construction. Movement from the first frame, primary Ba, to the second frame, secondary Ba, is accomplished through the skill of the actor producing the humor. The

dénouement is the point at which the first and second frames are shown to coexist, creating tension. The

release is the enjoyment registered by the audience in the process of realization and the release resulting therefrom, usually in laughter. Finally, the

afterglow is the pleasant situation that ensues from having laughed and shared humor with others (

Beeman, 1999;

Norrick, 1993,

1994;

Norrick & Chiaro, 2011;

Oring, 2003,

2010;

Sacks, 1974,

1978).

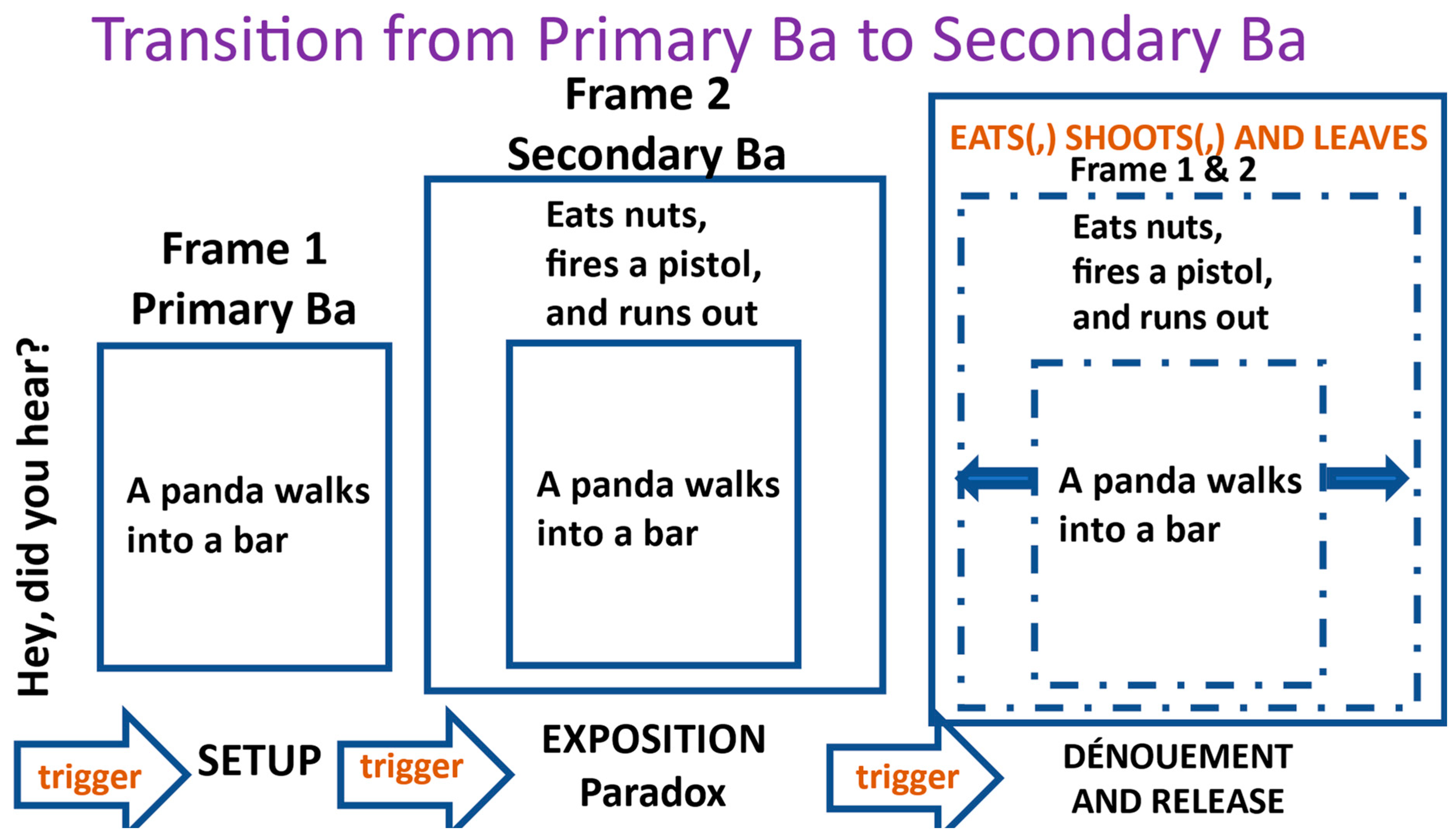

Figure 4 below shows this process.

8. Pragmemic Triggers

In other publications, I have written about the phenomenon of the

pragmemic trigger, a communication feature—verbal, visual, or behavioral—that affects a pragmatic transition from one intended cognitive state to another in a communicative structure

6 (

Beeman, 2017). I have dealt with this in describing the movement between stages in ritual (

Beeman, 2015b,

2018) and also in the process of commensality (eating a meal with others) (

Beeman, 2014)

7. However, the pragmatic trigger mechanism applies equally to the creation of humor.

The stages of humor production have been outlined above, but I focus here on the pragmatic trigger mechanisms that move the humorous communication through its processual stages to the dénouement, laughter, and the good afterglow feeling that follows.

9. Pragmemic Triggers in the Execution of Humor

To repeat what I have stated above, pragmemic triggers are the actions that creators of humor use to activate stages of the process of any communication event. Below are the five stages of humorous communication and the pragmemic triggers that affect the movement from one stage to the other. Although the description below emphasizes verbal formulas, in order to be effective, the pragmemic triggers specified must incorporate physical gesture, timing, facial expression, tone of voice, and other non-verbal communication. This is an essential part of the execution.

9.1. First Pragmemic Trigger—Initiation

9.1.1. Variation One—Direct Announcement

This is a clear indication that a recognizable form of humorous communication is about to happen. Based on primary Ba, participants should understand the nature of the humorous event. The most common way to do this is to alert listeners that a joke or other communication that is designed to lead to laughter is about to proceed. This can be done through the pragmemic trigger of linguistic formulas, such as:

There was this guy/gal …

A/an X walks into a bar.

Did you hear the one about the guy/gal/lawyer?

You know what they say about X …

Say, why does a/an X (do, look like, say, want to etc.)

So, … (X went into a store)

(Urging someone else to initiate the humorous event) Hey (Joe/Mary) tell the one about the X ….

These kinds of formulas are universally used by humans to initiate these kinds of humorous events.

These formulas are performative, because they must draw the attention of others who will be participating in the humorous event. This opens the humor “frame”. The person initiating the humorous event must show behavior that is disjunct from the atmosphere that surrounds them. Smiling, showing eagerness to initiate the humorous event, or otherwise physically indicating a departure from everyday interaction serves as an initiation. Here, the concept of “pre-announcement” developed by Douglas W. Maynard is relevant to this discussion. Maynard described “pre-announcement” as a preliminary utterance that signals an upcoming main announcement, functioning to cue the recipient that something significant is coming, often giving participants time to mentally or emotionally prepare or to actively orient to the upcoming news. Maynard’s “pre-announcement” could be considered to be a canonical pragmemic trigger in the spirit of this analysis (

Maynard, 1997,

2003).

9.1.2. Variation Two–Violation of Conversational Principles

Participants in humorous communication are also able to detect the initiation of the humorous event through noticing the disparity between the physical or verbal behavior of the initiator of the event and everyday “normal” behavior. Humorous communication is the antithesis of normal conversation or verbal interaction. Linguists and other social scientists have widely adopted Paul Grice’s “rules” for conversation as benchmarks in defining normalcy in interaction (

Grice 1975). These are:

Do not say what you believe to be false.

Do not say that for which you lack adequate evidence.

Avoid obscurity of expression.

Avoid ambiguity.

Be brief.

Morreall astutely noted that, when engaging in humor, we break these rules of conversation:

We break Rule 1 when for a laugh we exaggerate wildly, say the opposite of what we think, or “pull someone’s leg”. We break Rule 2 when we present funny fantasies as if they were facts. Rule 3 is broken to create humor when we reply to an embarrassing question with an obviously vague or confusing answer. We violate Rule 4 in telling most prepared jokes, as Raskin (1984) has shown (

Raskin, 2012). A comment or story starts off with an assumed interpretation for a phrase, but then at the punch line, switches to a second, usually opposed interpretation. Consider the line “I love cats. They taste a lot like chicken”. Rule 5 is broken when we turn an ordinary complaint into a comic rant like those of Roseanne Barr and Lewis Black.

As a humorous communication proceeds, the observer/listener may not at first comprehend that the initialization has begun, but as the communication proceeds, they will notice the kind of disjuncture pointed out by Morreall as conversational expectations are violated in the humor frame.

9.2. Second Pragmemic Trigger—The Setup

The setup frame is a narrative. The pragmemic trigger is a recognizable narrative discourse modality. This can also be accomplished through gesture, pantomime, or other non-verbal methods. The narration must be adequately accomplished. Either the actor must either be skilled in presenting the content of the humor or be astute in judging what the audience will assume from their own “primary Ba” cultural knowledge or from the setting in which the humor is created. The mark of a bad humorist is often the inability to establish the setup frame.

9.3. Third Pragmemic Trigger—The Paradox

The successful creation of the paradox exposition frame requires that the alternative interpretive frame or frames be presented adequately and clearly and be plausible and comprehensible to the audience. The pragmemic trigger consists of showing incongruity between narrative themes. The most amusing jokes are often risqué, because the reframing itself creates paradoxes that are difficult to express in everyday life without embarrassment, but when expressed in verbal humor or through physical action, the listener is distanced from responsibility from personal identification with the sentiment. This does not always work, since people are frequently offended by a particularly vulgar joke and may feel guilty for having even heard it.

9.4. Fourth Pragmemic Trigger—The Dénouement

The dénouement must successfully present the juxtaposition of interpretive frames. In English jokes, this is often identified as the “punchline”—the point where the two frames and their juxtaposition is revealed. If the actor does not present the frames in a manner that allows them to be seen together, the humor fails. Therefore, the performer of a joke or other form of humor must be highly skilled in performative skills such as timing, audience assessment, tone of voice, and physical demeanor. Without these skills, the joke will fail.

9.5. Fifth Pragmemic Trigger—Laughter

If the humorous communication is successful, the result will be autonomic, spontaneous laughter. However, in the telling of a joke, or other humorous expression, the narrator must allow a time interval to allow the listener to comprehend the paradox and the dénouement. A bad comedian “steps” on the laugh by not allowing this space. The “pragmemic trigger” is essentially this “realization” space. The end point of the humor, the laughter, leads to the “afterglow” of pleasant feeling that ensues after laughter has subsided.

10. A Panda Walks into a Bar

Taking the example of the classic “X walks into a bar” joke, we can analyze the stages of the joke’s development in the following diagram (

Figure 5):

- Hey, did you hear? A panda walks into a bar.

- He gobbles some beer nuts, then pulls out a pistol, fires it in the air, and heads for the door.

- “Hey!” shouts the bartender, “What the h*** are you doing?

- But the panda yells back, “I’m a panda. Google me!”

- The bartender grabs his phone and Googles: panda: “A tree-climbing mammal with distinct black-and-white coloring. Eats shoots and leaves”.

Figure 5 below shows how this joke works in terms of pragmatic triggering.

In

Figure 5, we see the first pragmemic trigger: the “pre-announcement” initiation: “Hey did you hear?” This tells listeners that a “joke” is about to ensue. To ensure that listeners know that this is indeed a prelude to a joke (and not an alarm or an announcement), smiling and tone of voice would accompany this utterance as part of the pragmemic trigger. The second pragmemic trigger also depends on performative skill, involving tone of voice and the use of a familiar “joke” formula: the setup “A panda walks into a bar”. The third pragmemic trigger: the paradox delivery, with proper timing and delivery, “The panda eats nuts, fires a pistol and runs out”. The fourth pragmemic trigger: the dénouement, again with proper timing and delivery, “A panda eats(,) shoots(,) and leaves”. The fifth pragmemic trigger is usually a pause by the narrator, signaling to the listeners that they must now make the connection between the main narrative and the dénouement. The laughter that ensues when participants realize the double framing incongruity between the panda’s actions and the ambiguity

double entendre of the description of the panda’s behavior.

Because this is a performative activity, these triggers must be executed with some skill. “Bad” joke tellers have trouble managing the triggers that move listeners from stage to stage. They have poor narrative skills, get the order of presentation mixed up, or start to laugh at their own joke before the listeners can resolve the paradox themselves. The initiator of the joke must not laugh—they must induce the listeners to laugh. This is why comedians point out frequently that humor is funniest when the comedian is “serious”. There is a wealth of literature on comic delivery, but success in inducing laughter involves successful execution of the kinds of pragmemic triggers described above, incorporating formulas, timing, rhythm, gesture, voice, and physicality (

Allen & Wollman, 1998;

Bergson, 1914;

Carter, 2019;

Double, 2020).

11. Types of Humorous Communication and Ba Theory

The above discussion deals with a generalized framework for the creation and execution of a humorous event. But when placed in the framework of Ba Theory, it is necessary to note that individuals in a social setting need to be able to mutually understand what actually “counts” as humor and what is “funny”. At the most basic level, they need to understand the language and rhetoric of the humorous communication.

Primary Ba, then, is the basis for mutual understanding and unity of thought of persons in any social relationship. Secondary Ba in the context of this discussion involves mutual recognition of the genres of humor recognized by participants and, within these genres, recognition of the process of moving through the humorous event with the help of pragmemic triggers to the ultimate goal of laughter. In this respect, every culture and society will have its own unique forms of humorous expression, and though they may be different, this discussion posits that the overall structure of humorous communication is a human universal.

It seems that relatively little work has been done in the comparison of genres of humorous communication cross-culturally (

Hasan et al., 2019;

Kalliny et al., 2006;

Oring, 1981), but also see

Oring (

1984,

1986,

1989,

2003,

2010,

2016). Peterson and Seligman, in their highly influential American Psychological Association-sponsored Handbook

Character strengths and virtues: a handbook and classification, seem unaware of comparative cross-cultural studies of humor. They state:

Folk wisdom tells us that there are national or cultural styles of humor. Some groups have earned themselves a reputation for having a characteristic style of humor (e.g., British humor, Jewish humor), and other groups are said to have no sense of humor at all (e.g., Germans, Japanese). Most cross-national research has involved essays describing national styles of humor or comparisons of jokes in folklore archives (

Davies, 1998;

Ziv, 1988a,

1988b). So far, no research program has examined humor as an individual difference across several cultures simultaneously.

Since it is widely puzzling for many people to understand the humor of another cultural tradition, it is perhaps not surprising that research on comparative humor has been scant, as Peterson and Seligman report. Of course, anthropologists have documented humor extensively but usually within the context of individual societies and rarely cross-culturally. It is particularly noteworthy and surprising in the context of this discussion that Peterson and Seligman suggest that it is thought that Germans and Japanese have no sense of humor. Not only is this somewhat startling as a proposition, but it is also demonstrably untrue. For this reason, this discussion will highlight both German and Japanese (as well as Chinese and Middle Eastern) humor in examples below.

12. Primary Ba and the Fundamentals of Comedy

As has been mentioned above, for participants in humor to be able to participate in the process of humor creation and “arrive” at the point where spontaneous laughter can be produced, they must share a common understanding both of their common linguistic competence and the dynamics of their shared cultural traditions, history, and social dynamics. This is the realm of primary Ba, as described earlier in this discussion. One of the reasons it is so difficult for people who do not share primary Ba understandings to find each other’s “sense of humor” funny is because of the lack of this shared understanding.

12.1. Puns

Perhaps the most fundamental form of shared humor is the “pun”. This form of humor is universal, and it is based on the possession of common language skills—the most general capability seen in primary Ba relationships. Native speakers of any given language can “get” the humor in a pun nearly instantaneously. Non-native speakers are often left wondering about what is funny in a pun because of limitations in their knowledge of vocabulary or grammar (

Sacks, 1973,

1974;

Sherzer, 1978,

1985,

2002). Below are some puns from different language groups.

12.1.1. English—Pun

I bought a wooden whistle. But it wooden (wouldn’t) whistle. So, I bought a steel whistle. But it steel (still) wooden (wouldn’t) whistle. So, I bought a lead whistle. But it steel (still) wooden (wouldn’t) lead (let) me whistle.

12.1.2. German—Wortspiel

Egal wie dicht du bist, Goethe war Dichter.

No matter how thick you are, Goethe was an author.

(dicht “thick”, dichter “thicker”, Dichter “poet, author”)

Wenn es Häute regnet, wird das Leder billig

If it rains today, leather will be cheap.

(Haut “skin” Häute “skins”, “today, skins”)

Egal wie viel Curry wir essen, Freddie isst Mercury.

No matter how much Curry we eat, Freddie is/eats Mercury.

(ist “is”, isst “eats”, “Mercury = mehr Curry “more curry”)

Egal wie gut du schläfst, Albert schläft wie Einstein.

No matter how well you sleep, Albert sleeps like Einstein.

(Einstein = ein Stein “a rock”)

Egal wie jung deine Freunde sind. Jesus’ Freunde waren Jünger

No matter how young your friends are, Jesus’ friends were disciples.

(jung “young”, jünger “younger” Jünger “deciples”)

12.1.3. Japanese 駄洒落 (だじゃれ) Dajare [pun]

パンダの好きな食べ物は何ですか?パンだ! Panda no sukina tabemono wa nadesu ka? Pan da.

What food does a panda like the most? Bread.

(パンダ (panda) sounds the same as パン だ pan da “it’s bread”

イクラはいくら? ikura wa ikura?

How much is the salmon roe?

イクラ (ikura) “salmon roe, いくら (ikura) “how much”

12.1.4. Chinese 双关语 Shuāng Guān Yǔ [pun]

有天螃蟹出门不小心撞倒了章鱼。

Yǒu tiān pángxiè chūmén, bùxiǎoxīn zhuàng dǎo le zhāngyú.

One day, a crab was taking a walk and accidentally knocked over an octopus.

章鱼很生气地说:“你是不是瞎啊?”

Zhāngyú hěn shēngqì de shuō: “Nǐ shì búshì xiā a?”

The octopus said angrily, “Are you blind?”

螃蟹说:“不是, 我是螃蟹。”

Pángxiè shuō: “Búshì, wǒ shì pángxiè”.

The crab said, “No, I am a crab”.

The word 瞎 (xiā)—“blind” sounds the same as 虾 (xiā)—“prawn”. “Are you a prawn?”—that’s what the crab heard.

12.1.5. Arabic لعبة الكلمات [pun]

I’ll be there this after ﻥ (noon)

Just don’t make a ﺱ (seen)

I ﻉ (‘ayn) worried about nothin’

You need to go to the ﺝ (jim)

Hey ﻖ ﻑ (fe, qaf), don’t be so ﻝ (lam)

(All the above are Arabic/Persian pronunciations of Arabic letters forming puns when read in English)

12.2. Jokes—Witz (German), 笑话 xiaohua (Mandarin), 冗談 jōdan (Japanese), نكتة nukta (Arabic)—all mean “joke”)

Jokes are narrative forms. They often incorporate puns but are more elaborate, involving the juxtaposition of different, disparate cognitive frames. Below are some examples.

- (1)

A Higgs-Boson particle walks into a [Catholic] church and the priest says “thank God you made it, we can’t have mass without you”.

(Higgs-Bosun particles are thought to be essential to creation of physical elemental mass in particle physics).

- (2)

René Descartes sitzt in einer Bar bei einem Drink. Der Barmixer fragt ihn, ob er noch einen möchte. “Ich denke nicht”, sagt er und verschwindet in einem Hauch von Logik.

(The bartender asks Descartes if he wants another drink. “Ich denke nicht” means both “I think not” and “I don’t think” So taking Descartes’ famous statement cogito ergo sum “I think, therefore I am” if he “doesn’t think”, he “disappears in a ‘puff of logic’.)

- (3)

A mullah enters a café and sees some men drinking liquor. Disapprovingly he says: “Haram ‘aleikum (Forbidden be upon you)”. The drinkers raise their glasses, smile, and say: “Wa ‘aleikum haram!”

(The response to the universal greeting “Salaam ‘aleikum (peace be upon you)” is “wa ‘aleikum salaam (and on you be peace)”.

- (4)

两个饺子结婚了,送走客人后新郎回到卧室,发现床上躺着一个肉丸。新郎大惊,问: “你是谁?” “我脱了衣服你就不认识我了?” 肉丸害羞地说。

Liǎng gè jiǎozi jiéhūn le, sòng zǒu kèrén hòu xīnláng huí dào wòshì, fāxiàn chuáng shàng tǎng zhe yí gè ròuwán. Xīnláng dà jīng, wèn: “Nǐ shì shéi?”. “Wǒ tuō le yīfu nǐ jiù bú rènshi wǒ le?”, ròuwán hàixiū de shuō.

Two dumplings got married. After seeing off their guests, the bridegroom returned to the bedroom, only to find a meatball lying on the bed. The bridegroom was shocked, and he asked, “Who are you?” “You don’t recognize me without clothes?”, the meatball said shyly.

(A Chinese/Japanese jiaozi/gyoza has a meat filling wrapped in dough. When “unwrapped”, the filling could look like a meatball).

12.3. Satire

Satire is another form of humor that is dependent on common understanding based in primary Ba. For satire to be understood, participants in humor must have a common reference point, since satire is a “twisted” view of a commonly understood aspect of social life, such as a social institution, a public figure, or a group (

Alterman & Sharro, 2020;

Pollard, 1970;

Worcester, 1940).

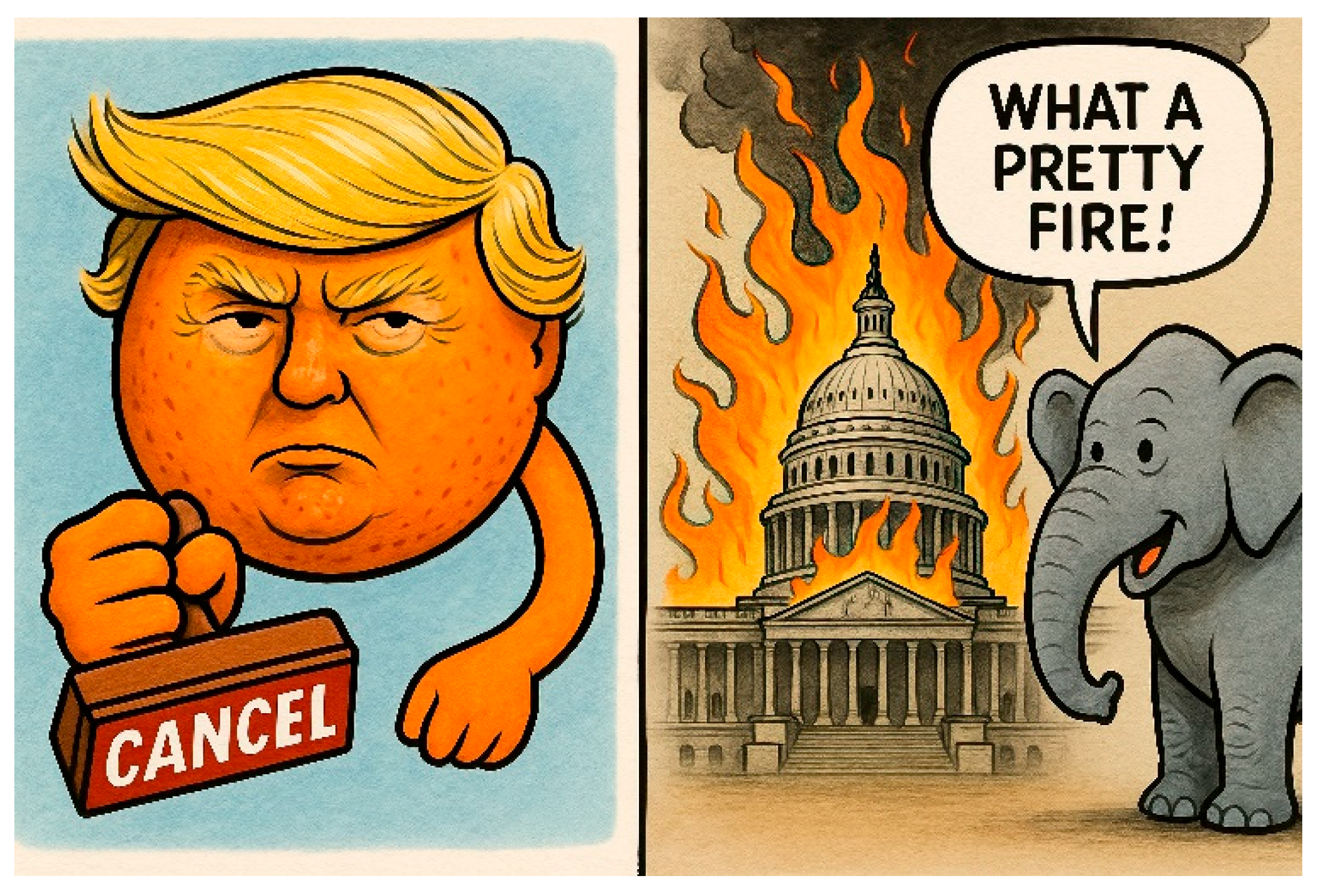

One of the principal forms of satire is the editorial cartoon. These visual forms of humor are closely tied to current events and are nearly incomprehensible to people living outside of the immediate social sphere in which the cartoon exists.

Figure 6 shows two examples of satirical cartoons. The first image refers to President Donald Trump and his administrative “style”. The second represents the Republican Party, which mascot is the elephant, and its purported disregard for political “conflagration” in Washington. To understand the images, viewers must participate in the shared Ba of United States political life. In the first image, they must know the characteristics that identify Mr. Trump, his “orange” complexion, and his characteristic hair. In the second image, they must recognize the Republican elephant image and the image of the United States Capitol.

12.4. Parody

Parody is closely related to satire in terms of mutual understanding. Parody relies on a common understanding of an existing social form or existing literary or artistic work—the essence of primary Ba. For example, stories presented in works of Shakespeare might be presented in exaggerated or comedic form for humorous effect. But if one does not know Shakespeare’s original works, the humor will not be understood (

Dentith, 2000;

Hutcheon, 2000;

Müller, 1997;

Rose, 1993).

Parodies of the Mona Lisa are very widespread because the image is so universally known. The images in

Figure 7 distort the Mona Lisa image, presenting her as a Picasso painting, as a modern “punk” figure, and as a representation of the iconic painting “The Scream” by Edvard Munch.

12.5. Cultural Sensibilities—Limits to Humor

Finally, there are cultural sensibilities that reflect the values of a culture concerning what may be acceptable as humor. These, too, are an aspect of primary Ba. In some societies, there are taboos against humor that focus on sexual subjects, on the depiction of specific groups of people (ethnic humor), on satire or ridicule of religious institutions, on depiction of prominent social figures, on political institutions, or on subjects that might cause embarrassment to another person or persons. Though humorous communication dealing with these subjects may be presented in the form outlined above, the resulting reaction on the part of participants may not result in laughter but rather other basic emotions such as anger, disdain, or disgust. One curious aspect of this dynamic is that humor dealing with these taboo subjects may result in spontaneous laughter, but this may be laughter for which participants may feel shame (or think they should feel shame). Harvey Sacks’ important work on the “dirty joke” shows this ambiguity (

Sacks, 1974,

1978).

13. Genres of Humor

I would now like to turn to genres of humor as seen in four distinct cultures: Japan, China, Germany, and the Arabic/Middle Eastern world. My point in doing this is to argue that, although the institutions for the production of humor are different in each of these cultural settings, the structure for the production of humor follows the framing and pragmemic trigger pattern I have outlined above.

13.1. Japan

Japanese humor has been widely explored (

Abe, 2002;

Aso, 1966;

Bråth, 2018;

Hibbett, 2002;

Sigmundsdóttir, 2016;

Wells, 1997), and a thorough review of all aspects of Japanese humor is far beyond the scope of this paper. However, some things are notable in the construction of Japanese humorous situations. Wordplay (puns, double entendre), exaggerated physical and verbal situations, and gags—what in the Western world might be termed “slapstick” comedy—and puns are important features of Japanese humor. The role of performance partners in the creation of humor performances is also prominent. For these to be appreciated, individuals must also be clearly aware of Japanese social customs and sensibilities, such as

keigo 敬語 “polite speech” and

wakimae 弁え “discernment” (

Ide, 1989).

13.1.1. Kyogen

Kyogen 狂言 (狂 “madness, craziness 言 ”speech”) is arguably the oldest active comedy form in Japan. Originally established in the 15th century as an entr’acte between episodes in a Noh drama, it has become an independent performance form in modern times.

Kyogen plays are characterized by their humorous and light-hearted nature. They typically feature exaggerated gestures, distinctive vocal patterns, and comedic storytelling. The actors employ stylized movements and language patterns to entertain the audience and elicit laughter. Many Kyogen plays incorporate elements of traditional Japanese customs and cultural practices.

Though there may be several characters in Kyogen, the main roles are the 主役 (Shuyaku) or 主人公 (Shujinkō), literally the “main character” (usually a high-ranking person), and the 道化 (Dōke) or clown (道化 “path of transformation, interpreted as madness or folly”). Although the interplay between the high-ranking person and the clown is a common theme, frequently, the play consists of two clowns whose foolish antics are the crux of the comedy. The plays satirize customs and behavior of the Edo period, but the humor portrayed is universal in its comedic effect.

Masks are frequently used in Kyogen performances to portray specific characters and express their emotions or traits. These masks play a crucial role in conveying the essence of the characters. The art of Kyogen represented in

Figure 8 also emphasizes skilled acting techniques and rhythm. Actors entertain the audience through comical movements, facial expressions, and precise timing.

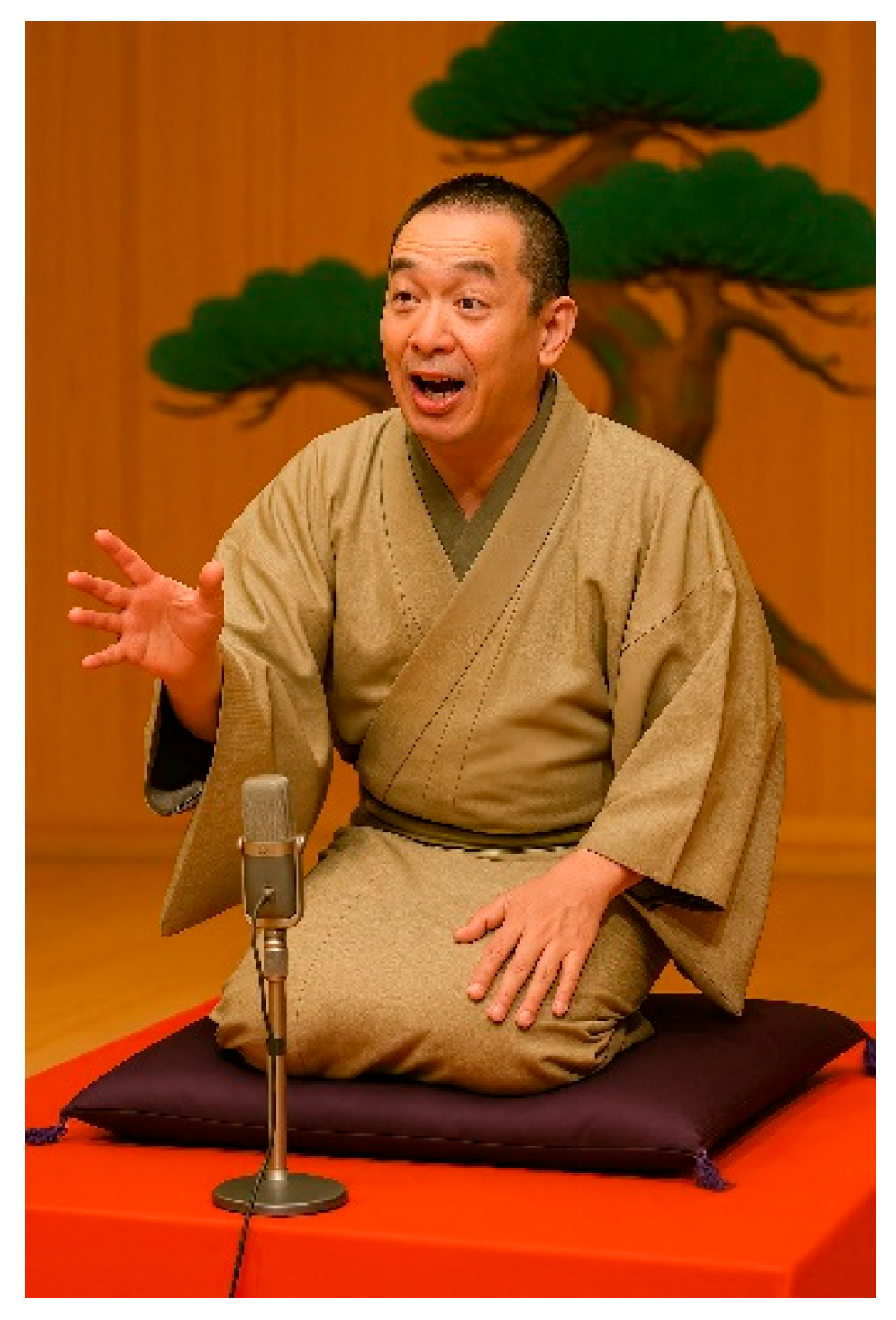

13.1.2. Rakugo

Rakugo, as seen in

Figure 9, is a traditional form of Japanese comedic storytelling that has been entertaining audiences for centuries. It is a form of sit down comedy performance where a single performer, known as a rakugo artist or rakugoka 落語家, (“落” to “fall”), sits on a stage and tells a humorous story using only a fan and a small cloth as props (

Brau, 2008;

Sweeney, 1979; see also

Szatrowski, 2010 regarding general storytelling dynamics).

The rakugoka typically begins by introducing themselves and the story they will be performing. They then take on multiple roles, using different voices, facial expressions, and body language to differentiate characters within the story. The stories often involve witty dialogues, wordplay, and humorous twists. The expressions, voices, and characterizations in part derive from other Japanese theatrical forms such as Noh and Kabuki.

Rakugo stories are usually based on traditional tales or everyday situations, depicting humorous episodes from daily life, historical events, or folklore. The stories are typically set in the Edo period (1603–1868) and often showcase the quirks and eccentricities of different characters. A familiarity with this historical period and the arts and customs of the period is necessary for full appreciation of the art form.

The performance style of rakugo involves a combination of verbal delivery and physical gestures. The rakugoka sits on a small cushion called a zabuton and uses minimalistic movements to enhance the storytelling. The performer’s skill lies in their ability to captivate the audience solely through their storytelling techniques and comedic timing.

Rakugo has a rich history and has been passed down through generations of performers. It requires extensive training and apprenticeship to master the art form. Today, rakugo continues to be performed in theaters, cultural festivals, and on television in Japan, delighting audiences with its blend of humor, wit, and storytelling prowess.

13.1.3. Manzai

Manzai (漫才) is a traditional form of Japanese comedic duo performance characterized by rapid back-and-forth dialogues between two comedians. It is a popular form of standup comedy in Japan and has a long history dating back to the Edo period (1603–1868). Manzai is known for its fast-paced banter, wordplay, puns, and comedic timing (

Katayama, 2008;

Zawiszová, 2021).

In a typical manzai performance, there are two comedians: the “boke” ボケ (funny man) and the “tsukkomi” 突っ込み (straight man). The character 突 (tsuku) means “to thrust, poke”, and 込 (komu) means “to enter/insert”. The boke plays the role of a foolish or naive character who often makes silly or nonsensical remarks, while the tsukkomi acts as the more rational and sharp-witted partner who corrects or criticizes the boke’s statements. These roles mirror the Shuyaku 主役 “straight man” and Doke 道化 “clown character”.

The comedy routine usually consists of a series of short skits or jokes based on everyday situations, misunderstandings, or social commentaries. The boke’s humorous statements or actions serve as setups for the tsukkomi’s clever comebacks or sarcastic remarks. The interaction between the two comedians generates laughter from the audience.

Manzai, as represented in

Figure 10, is performed on a stage with minimal props, focusing primarily on the dialogue and comedic chemistry between the duo. The performers utilize exaggerated facial expressions, gestures, and vocal inflections to enhance the humor of their routines. The timing and rhythm of the dialogues are crucial, with the tsukkomi’s punchlines often met with a pause, followed by laughter from the audience.

Manzai has a significant presence in Japanese entertainment, and comedic duos perform in various venues, including theaters, television programs, and comedy festivals. It continues to evolve with modern influences while preserving its traditional roots, and many successful comedians in Japan have started their careers through manzai.

13.1.4. Senryū

川柳 (Senryū) (川柳 “willow river”) is a traditional form of Japanese poetry that is similar to haiku in structure but focuses on human nature and the human condition, often with a touch of humor or satire. The name is commonly believed to be derived from the name of the poet Karai Senryū, a disciple of Matsuo Basho, the famous haiku master. Senryū was known for his witty and satirical verse. Although there are differing theories about the exact origin of the name.

The poetic structure of senryū follows a 5-7-5 syllable pattern, just like haiku. It consists of three lines, with the first and third lines containing five syllables and the second line containing seven syllables. Unlike haiku, which typically centers around nature and seasonal elements, senryū focuses on human nature, emotions, social interactions, and observations of everyday life. It often highlights the quirks, ironies, and foibles of human behavior.

Often incorporating humor, wit, and satire, senryū may employ wordplay, double entendre, or clever twists to evoke amusement or provide a satirical commentary on human behavior and society. Senryū can also express personal reflections or contemplations on various aspects of human existence. It explores universal emotions, relationships, and the human experience. Like haiku, senryū aims for brevity and succinctness. It captures a moment or sentiment concisely, using carefully chosen words and vivid imagery. Senryū is often written in a light-hearted and whimsical tone, making it an enjoyable form of poetry that offers insight into the human condition with a touch of humor and satire.

Senryū also involves parody of the traditional classic poetic form waka (和歌—“lit. Japanese poetry”), one manifestation pertinent to senryū being tanka or “short poem”. To fully understand the humor of these senryū parodies, a reader must be familiar with these classical poetic forms. The poetry also “make[s] satirical targets of Neo-Confucian laws and customs, particularly those relating to the family, sexual relations, and … the double standard applied to men and women (

Rabson, 2003, p. 4).

While there may be occasions where senryū is recited or read aloud in a poetic gathering or literary event, it is not primarily intended for performance in the way that theatrical or dramatic forms such as kyogen, rakugo, or manzai are. Instead, senryū is appreciated for its concise and insightful observations on human nature, humor, and satire through the written word (

Blyth, 1964;

Brown, 1991;

Gardner, 2002;

Opler & Obayashi, 1945;

Rabson, 2003). For senryū to be appreciated and seen as amusing, readers must share a great deal of “primary Ba” cultural knowledge.

Figure 11 provides an example.

13.2. Chinese

Chinese genres of humor are extensive. Like Japanese humor, they depend extensively on wordplay, puns, and humorous banter between individuals. They are often impossible to understand well unless one has an extensive knowledge of the Chinese language, often dialects, because the Chinese language has so many homonyms. Many Chinese jokes are also formulated as riddles to heighten the effect of the pun.

13.2.1. Xiàngsheng 相声 (Crosstalk)

相声 (xiàngsheng) is a traditional Chinese comedic performance art form that involves comedic dialogue, sketches, and storytelling, much like Japanese rakugo, manzai, and the two-person interchanges found in Japanese kyogen. Like manzai, it is often performed by two people, with one playing the “straight man” role and the other playing the “funny man” role. The performers engage in witty banter, wordplay, and humorous exchanges, entertaining the audience with their comedic timing and delivery. Xiàngsheng, represented in

Figure 12, has a long history in Chinese culture and remains popular in various forms of entertainment, including stage performances, television shows, and radio programs (

Moser, 1990,

2018;

Tsau, 1980).

13.2.2. Cold Jokes 冷笑话

冷笑话 (lěng xiàohuà) is a term that translates to “cold jokes” in Chinese. Cold jokes are a specific type of humor that relies on unexpected punchlines, wordplay, or absurdity. They are called “cold” because they often elicit a reaction of confusion or a delayed response before the humor is understood. These jokes often play with language, cultural references, or absurd situations to create a humorous effect. Cold jokes can be a form of dry humor or rely on clever wordplay, and they are popular in online communities, social media, and casual conversations in China.

The term “cold joke” derives from the kind of laughter that these jokes generate. “冷笑” (lěngxiào) is a Chinese term that translates to “sneer” or “mocking laughter”. The closest approximation for Westerners might be the laughing “groan” that people give out when hearing a particularly corny joke, as represented in

Figure 13. Lěngxiào refers to a derisive or contemptuous type of laughter, often accompanied by a sense of cynicism or ridicule. It is an expression of disdain or mockery towards someone or something. “冷笑” can also be used to describe a sarcastic or ironic type of laughter that conveys a lack of sincerity or genuine amusement.

13.3. Arabic/Middle Eastern

Modern Arabic and Middle Eastern humor is increasingly emulating Western-style standup comedy, but Western-style sketch comedy has deep roots in the Arabic-speaking world. In the Arab world, improvisational comedy has gained popularity in recent years, with the emergence of improv groups and comedy clubs in countries like Egypt, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates. Arab improv comedy may derive from language and wordplay, but it is more heavily based in satire, often incorporating cultural references, contemporary politics, social commentary, and local humor into the performances. The comedic style can vary, ranging from physical comedy and wordplay to satirical improvisation on current events or daily life situations.

Arab improv comedy not only entertains audiences but also serves as a platform for social and political commentary, providing a lighthearted way to address serious topics and engage with audiences humorously and interactively. It has become a popular form of entertainment in the Arab comedy scene, with dedicated improv troupes and shows being performed in theaters, comedy festivals, and online platforms.

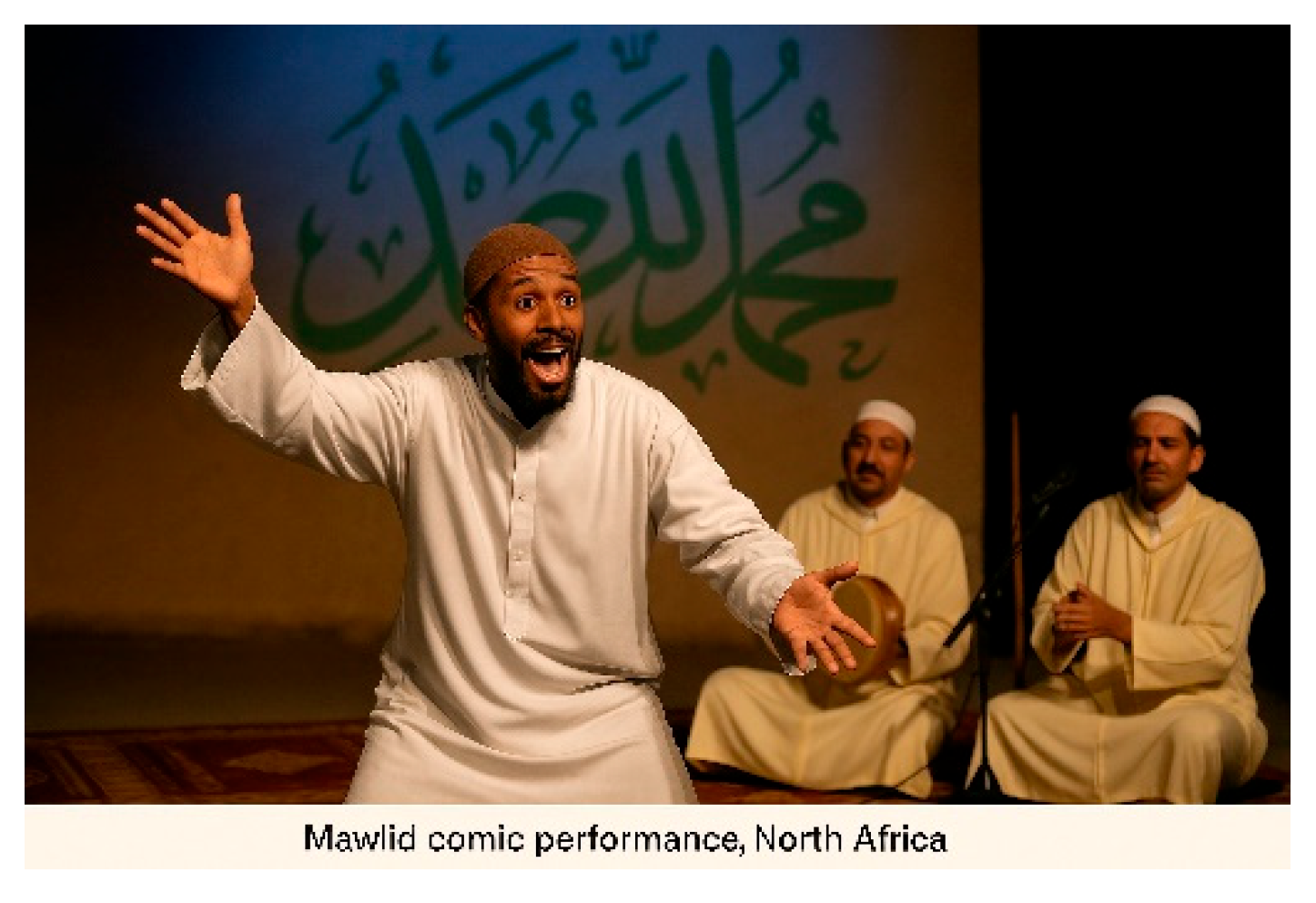

Mawlid مولد

“Mawlid” is a term used in Islam to refer to the celebration of the birth of the Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him). The celebration of Mawlid, represented in

Figure 14, takes many forms, and different Muslim communities around the world have developed their unique ways of observing it.

In some cultures, including some parts of the Arab world, humorous or satirical poems and skits are sometimes performed during Mawlid gatherings as a way of entertaining the audience.

For example, in some parts of North Africa, comedians may perform humorous skits or plays that poke fun at certain aspects of Islamic history or religious figures. These skits often use satire and exaggeration to make their points and are meant to be taken in good humor. Similarly, in some Arab countries, poets may recite humorous or playful poems that use religious motifs and themes to entertain the audience.

It’s important to note, however, that not all Muslims view this kind of humor as appropriate or respectful during Mawlid celebrations, and some religious scholars have even issued fatwas (religious rulings) against it. Therefore, any humor or satire included in Mawlid celebrations should be approached with sensitivity and caution, taking into account cultural and religious sensibilities.

13.4. Germany

Far from being “humorless”, German humorous traditions are historical and extensive. The German sense of humor is often described as straightforward, dry, and sometimes sarcastic. German humor tends to rely on wit, irony, and clever wordplay rather than slapstick or physical comedy. Here are some key characteristics of German humor:

Satire and Sarcasm: Germans appreciate satire and often use it to critique societal norms, politics, and authority figures. Satirical programs, political cartoons, and comedic shows are common in German media. German humor often involves observations about everyday life, human behavior, and social situations. Comedians may point out common quirks and idiosyncrasies that resonate with audiences. This is common in everyday life as well, and Germans expect a certain amount of “ribbing” from their friends and family. Germans enjoy playing with language and appreciate clever puns and wordplay. They find amusement in linguistic jokes and witty word association. Germans are known for their deadpan delivery, where jokes are delivered with a straight face and minimal emotional expression. This dry and understated approach can add an extra layer of humor to comedic situations. German humor can have an intellectual edge, drawing on cultural references, historical events, and philosophical concepts. Intellectual jokes that require some background knowledge or understanding may be appreciated by German audiences. Germans have a reputation for appreciating dark or gallows humor. They can find humor in topics that may be considered taboo or sensitive in other cultures, as long as it is handled with intelligence and sensitivity (

Howell, 2004;

Kluth, 2016;

Ruch & Heintz, 2016).

13.4.1. Cabaret (Kabarett)

Cabaret, as seen in

Figure 15, is a form of entertainment that combines comedy, music, satire, and social criticism. It originated in France but has a strong presence in Germany as well. Cabaret performances often include humorous sketches, musical performances, political satire, and witty wordplay (

Bauschinger, 2000;

Casadevall, 2007;

Siegordner, 2003).

13.4.2. Comedic Theater (Komödientheater)

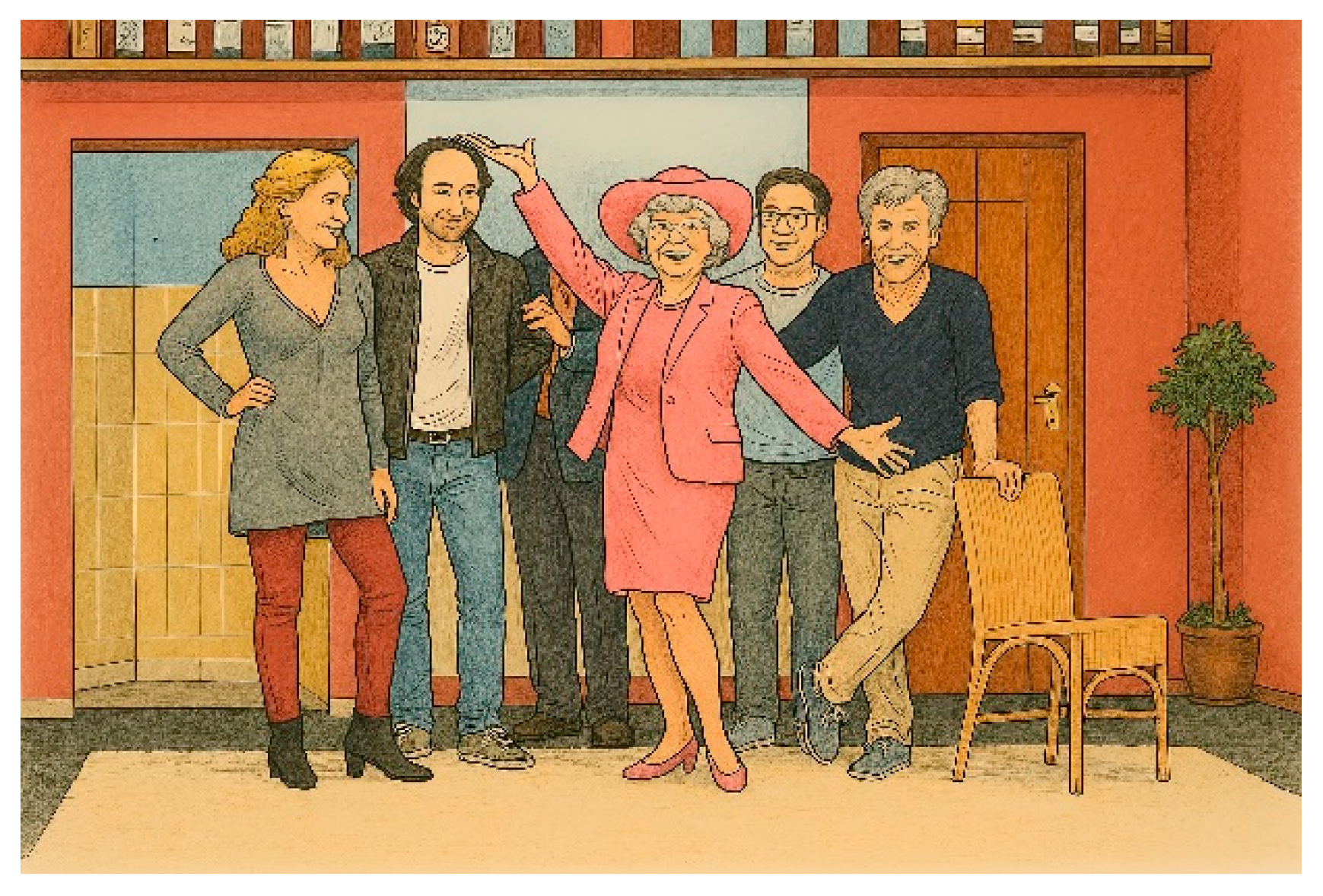

German theater has a long history of comedic productions. Comedic theater performances, such as illustrated in

Figure 16, can range from classic plays by renowned playwrights, such as Johann Wolfgang von Goethe or Bertolt Brecht, to contemporary comedic plays and farces.

13.4.3. Comedy TV Shows (Comedy-Sendungen)

Germany has a vibrant comedy television industry with numerous shows dedicated to comedy. These shows feature a variety of formats, including sketch comedy, improvisation, and comedic panel discussions, where comedians interact and engage in humorous banter.

13.4.4. Improv Comedy (Improvisationskomik)

Improvisational comedy, where performers create scenes and dialogue on the spot without a script, also has a presence in Germany. Improv groups and shows entertain audiences with spontaneous humor, quick thinking, and interactive performances.

14. Comparison of Forms and the Basis for Humor

When people in a given society share a primary Ba relationship, they have the basis for understanding humorous communication, and they also know “what is funny”. Even when the procedures for creating humorous expression are followed, if primary Ba relationships declare that certain themes or taboos are “off limits”, participants will either not laugh or will feel embarrassed to have laughed at the humor.

Here are some contrasting versions of humor. Satire and parody are more prevalent in Middle Eastern and German humor. They are also prominent in American humor. Puns and wordplay are higher in Japanese and Chinese humor and more moderate in Middle Eastern and German humor. Physicality is high in Japanese and Middle Eastern humor and more moderate in Chinese and German humor. Sexuality is prominent in German humor, moderate in Chinese and Japanese humor, and circumspect (but present) in Arabic/Middle Eastern humor.

The well-known Chinese author Lin Yutang wrote extensively on humor, including a book-length treatment

The Chinese Sense of Humor. He was a strong advocate for not using humor to belittle or insult others. He wrote: “幽默是没有仇恨的表现,幽默的人很少是恶毒的。”—《中国人的幽默》 “Humor is not an expression of hatred, and humorous people are rarely malicious (

Lin, 2005).”

8Satire and parody are not favored in Japan and China largely because of the need to preserve “face” in these cultures. Humor that diminishes or insults others is widely disapproved. Jamie Dimon, Chief Executive at JP Morgan Chase Bank, was forced to apologize when he made the following joke in Boston in November 2021 during a visit to the Boston College Chief Executives Club.

“I was just in Hong Kong; I made a joke that the Communist Party is celebrating its 100th year. So is JPMorgan. And I’ll make you a bet we last longer”, he said on Tuesday at a Boston event. Then he added: “I can’t say that in China. They probably are listening anyway”. The Chinese government was immediately alerted and issued strong disapproval (

Levitt, 2021).

Looking at forms of humor comparatively, we can see contrasts in the themes discussed above in viewing the humor processes treated in this discussion. A relative comparison of the mechanism for helping consumers of humor transit from an initial Frame 1 (primary Ba) to a subsequent Frame 2 (secondary Ba), creating the surprise factor that produces spontaneous laughter, is somewhat subjective, but some general observations may be useful.

Some languages lend themselves much more easily to puns and wordplay by the very ease of producing ambiguity in understanding. Japanese and Chinese are particularly facilitative of this kind of humor. Physicality is a feature that plays a large role in Japanese and Arabic/Middle Eastern humor. This may be because, in these societies, the notion of the “face” is highly valued, and physical humor bypasses language that could be considered impolite. This also may account for the reason that parody and ridicule are less prevalent in Japan and China. Parody is used extensively in the Middle East and in German humor. This rather blunt form of humor allows for social commentary without direct assault on public figures, which is politically expedient. Of all forms of humor, sexuality is the most circumspect of techniques. Personal modesty is a feature of many traditional societies, and so, sexuality as a source of humor is cautiously employed. However, sexuality and scatological themes are appreciated in German humor, where social interaction is more open and straightforward. In general, then, the process of humor adheres to social and cultural norms, which are, in the spirit of this analysis, a reflection of primary Ba in the societies where they are practiced. A summary of these contrasts is provided in

Table 2.

15. Conclusions

I join with many previous researchers in believing the dynamics of humor creation to be universal for all human beings. The combination of universal constructions through narrative, visual materials, and behavior, joined with extensive local cultural knowledge, creates a palette for all expressions of humor. I have further tried to emphasize that humor is a performative accomplishment drawing on the common understandings people share through primary and secondary Ba understandings.

Then, I have emphasized that humor creation depends on using universal mechanisms: ludic modality, double framing, the triggering of a combination of basic emotions of surprise and happiness/joy through the process of pragmatic triggering, which moves consumers of humor by stages, from the initial encounter with material designed to be humorous to the point of spontaneous laughter as the humorous event reaches dénouement. Pragmemic triggering can be seen as the mechanism by which participants in a comedic event move from the common cultural understandings of primary Ba to the more specific created understanding of secondary Ba. The surprise of the breaking of tension between these two states generates the spontaneous autonomic response of laughter.

In the latter half of this discussion, I have focused on comparative forms of humor that universally depend on puns, turns of phrase that are extremely difficult to translate between languages. They also depend on cultural knowledge, familiarity with historic and contemporary individuals, and social rituals as part of the primary and secondary ba unity within individual cultures and societies.