Abstract

Effective language processing relies on pattern detection. Spanish monolinguals predict verb tense through stress–suffix associations: a stressed first syllable signals present tense, while an unstressed first syllable signals past tense. Low-proficiency second language (L2) Spanish learners struggle to detect these associations, and we investigated whether they benefit from game-based training. We examined the effects of four variables on their ability to detect stress–suffix associations: three linguistic variables—verbs’ lexical stress (oxytones/paroxytones), first-syllable structure (consonant–vowel, CV/consonant–vowel–consonant, CVC), and phonotactic probability—and one learner variable—working memory (WM) span. Beginner English learners of Spanish played a digital game focused on stress–suffix associations for 10 days and completed a Spanish proficiency test (Lextale-Esp), a Spanish background and use questionnaire, and a Corsi WM task. The results revealed moderate gains in the acquisition of stress–suffix associations. Accuracy gains were observed for CV verbs and oxytones, and overall reaction times (RTs) decreased with gameplay. Higher-WM learners were more accurate and slower than lower-WM learners in all verb-type conditions. Our findings suggest that prosody influences word activation and that digital gaming can help learners attend to L2 inflectional morphology.

1. Introduction

Predictive processing plays a role in a wide range of brain functions, including language processing (see Huettig, 2015, for a review of the function and mechanisms of prediction in language processing). Using prior linguistic experience, first and second language (L2) learners anticipate upcoming speech by recognizing associations between linguistic and contextual cues and targets (see Kutas et al., 2011; and Kaan & Grüter, 2021, for first language (L1) and L2 reviews, respectively). Prediction facilitates efficient language processing and may also play a role in L2 acquisition (Bovolenta & Marsden, 2021). Beginner L2 learners show limited L2 predictive processing abilities when their L1 lacks the predictive cue (Dussias et al., 2013; Mitsugi & MacWhinney, 2015; Gosselke Berthelsen et al., 2018) or when the L1 cue functions differently in the L2 (e.g., Sagarra & Casillas, 2018). However, intensive training helped low-to-intermediate proficiency L2 Swedish learners detect tone–suffix associations despite their L1 being non-tonal (Schremm et al., 2017; Hed et al., 2019). To our knowledge, these are the only studies to date focusing on the impact of game-based training on L2 learners’ predictive processing skills, and they are limited to focusing on a suprasegmental cue that is absent in the L1. This raises the following question: does training also facilitate L2 prediction with L2 suprasegmental cues that are acoustically realized differently and carry a different weight in the L2 than in the L1?

We investigated whether game-based training influences beginner-level Spanish L2 learners’ ability to predict verb suffixes in disyllabic verbs based on lexical stress, a cue relied on more heavily in Spanish than in English for lexical access. Listeners use stress placement to discriminate words more frequently in Spanish (papa–papá ‘potato–dad’) than in English (permit–permit), whereas English favors segmental cues (full vs. reduced vowels) for word discrimination (Cutler, 1986). To understand what affects beginner learners’ ability to detect stress–suffix associations, we examined three linguistic variables (lexical stress: oxytones/paroxytones; syllabic structure: CV/CVC; and phonotactic probability) and one learner variable (WM span). We examined how game-based training affects stress–suffix associations in Spanish in verbs with varying syllabic patterns as well as WM’s mediating role in these processes. The results have implications for phonology models, lexical access models, psycholinguistic models, and L2 instruction.

2. Prosody in L2 Processing and the Role of Training

Prosody-the patterns of intonation, rhythm, tone, and stress in speech, helps speakers parse spoken language and conveys lexical meaning (Cutler et al., 1997). L1 speakers use various types of prosodic cues to predict upcoming linguistic information, including intonation in English, German, and Japanese (Nakamura et al., 2012; Ito & Speer, 2008; Perdomo & Kaan, 2021; Foltz, 2021; Weber et al., 2006), tone in Swedish (Roll et al., 2015; Söderström et al., 2017), and stress in Spanish (Sagarra & Casillas, 2018).

However, L2 users often struggle to use prosody for prediction, especially when they have low proficiency and their L1 lacks the predictive prosodic cue or uses it differently from the L2. For example, advanced L2 learners of Swedish anticipated upcoming number and tense suffixes using tonal cues (Schremm et al., 2016), while beginner L2 learners (Gosselke Berthelsen et al., 2018) did not, with both groups lacking tone in their L1. Similar findings have been observed with English-speaking learners of Spanish. Although English has contrastive stress, it serves as a stronger cue in Spanish during lexical competition. In Sagarra and Casillas (2018), advanced—but not beginner—English-speaking learners of Spanish used stress cues to anticipate verbal morphology but only when the first syllable had a CVC structure. However, unlike Spanish L1 speakers, the advanced learners did not predict verbal morphology when the first syllable was open (CV), likely because the presence of a coda reduces lexical competitors, thereby facilitating prediction.

One explanation for L2 learners’ difficulties is that their mental representations may not contain sufficiently robust associations between cues and targets (e.g., tone–suffix; stress–suffix) (Grüter et al., 2012; Hopp, 2013). These associations rely on statistical learning mechanisms, where language users unconsciously track probabilities and co-occurrence patterns in language input (Saffran et al., 1999). One approach for increasing L2 learners’ awareness of associations between cues and targets is to provide training through explicit training tasks that require making predictions based on cues, thereby fostering the development of anticipatory processing skills (DeKeyser & Criado, 2012).

Digital game-based training has emerged as an engaging means of promoting more native-like predictive processing among L2 learners (Schremm et al., 2017). Schremm et al. (2017) and Hed et al. (2019) explored the impact of a digital game on L2 prediction. L2 learners of Swedish with non-tonal L1s played a game aimed at training Swedish tone–suffix associations during a two-week period. The results showed higher accuracy, faster reaction times (RTs), and more native-like neural processing patterns after training. These findings suggest that digital games can enhance L2 learners’ anticipatory processing abilities. However, further research is needed to explore how training might support L2 learners’ anticipatory processing abilities when making associations based on cues that are used differently in the L1 than in the L2.

3. Linguistic Variables: Lexical Stress, Syllable Structure, and Phonotactic Probability in Spanish and English

As speech unfolds, multiple lexical candidates are activated. Semantically related words (cat and dog) and phonologically similar words (cat and cap) compete for activation until the target word is identified. During lexical competition, the activation of the target word increases, whereas the competing words exhibit a reduction and suppression in activation (lexical inhibition) (Norris et al., 2006). The activation and decay of phonetic, phonological, and lexical information are continuously updated as we process L1 and L2 words. Different languages may use distinct cues for lexical access (e.g., Swedish uses tone to differentiate words, but German does not, Gosselke Berthelsen et al., 2022) or use similar cues that carry more weight in one language than the other (e.g., Spanish and English use lexical stress to distinguish words, but stress is preferred in Spanish, Soto-Faraco et al., 2001, and vowel reduction is favored in English, Cooper et al., 2002). In the present study, we investigated the effects of lexical stress, syllabic structure, and phonotactic probability on the ability of beginner English learners of Spanish to detect stress–suffix associations in L2 Spanish.

Lexical stress. Lexical stress is the relative prominence of one syllable in comparison to the other syllables in a word. As a suprasegmental feature, it operates above the level of individual sounds. Although lexical stress is contrastive in both Spanish and English, the two languages differ in how stress is realized and the functional load it carries. In Spanish, stress is marked mainly by pitch height, intensity, and loudness (Hualde, 2005). In contrast, in English, it is conveyed primarily through pitch height and vowel duration and quality (Cooper et al., 2002). Also, the prosodic properties of stress bear a greater functional load in Spanish and are used more frequently to distinguish words (Cooper et al., 2002; Soto-Faraco et al., 2001), whereas in English, the segmental properties of stress like vowel reduction are more important for word recognition (Cutler, 2012; Tremblay, 2008; Tremblay et al., 2017). Given that the importance of stress cues varies per language (Chrabaszcz et al., 2014; Holt & Lotto, 2006), English L2 learners’ difficulties in perceiving (Face, 2005; Ortega-Llebaria et al., 2013) and producing (Lord, 2007) Spanish stress may be due to misdirected attention to relevant acoustic cues during L2 learning. Regarding frequency and lexical competition, we expected the processing of stress–suffix associations to be facilitated in oxytones over paroxytones because paroxytones are the most frequent stress pattern in Spanish (Morales-Font, 2014). Oxytones, therefore, activate fewer lexical competitors. In Spanish disyllabic verbs, the stress pattern differs between present and past tense verb forms. Present tense verbs have a paroxytone stress pattern with stress falling on the penultimate syllable, i.e., the first syllable (e.g., habla ‘he/she speaks’). Past tense verbs have an oxytone stress pattern with stress falling on the final syllable (e.g., habló ‘he/she spoke’).

Syllabic structure. Syllabic structure, a segmental feature, refers to the organization of sounds within a syllable. Syllabic structure influences lexical access by facilitating anticipatory processes in words that start with segments that have fewer possible endings. Concerning the frequency and number of lexical competitors, CV is considered the unmarked syllable shape in all languages, but the coda of CVC-initial-syllable words offers additional information that helps narrow down possible word matches and facilitates lexical access (Sagarra & Casillas, 2018).

Phonotactic probability. Phonotactic probability is the frequency with which a particular segment or sequence of segments occurs in a specific position within a word (Vitevitch & Luce, 1998). High-phonotactic-probability sequences frequently occur in dense phonological neighborhoods, meaning that the words in which they appear have many phonologically similar neighbors, whereas low-probability sequences are typically found in sparse phonological neighborhoods. According to the Neighborhood Activation Model (NAM; Luce & Pisoni, 1998), words in dense phonological neighborhoods activate more lexical and sublexical candidates, hindering lexical access (Vitevitch et al., 1999). English L1 speakers (e.g., Luce & Pisoni, 1998; Vitevitch & Luce, 1999; Vitevitch et al., 2008) and L2 speakers (e.g., Hamrick & Pandža, 2014) recognize words in high-density neighborhoods more slowly and less accurately than those in low-density neighborhoods, as demonstrated in lexical decision and auditory naming tasks.

4. Working Memory in L2 Processing

WM, the ability to maintain and manipulate information during ongoing processing (Cowan, 2017), may impact how effectively learners process and anticipate linguistic input in an L2. Research on WM effects on L2 morphological processing has yielded mixed results. Some studies report no WM effects in the processing of verb morphology (Durand López, 2021; Rızaoğlu & Gürel, 2020). However, distinct findings have been observed when researchers have increased the demands of L2 morphological processing by asking learners to process suffixes that agree with each other (Sagarra & Herschensohn, 2010) or to anticipate morphological information (Lozano-Argüelles et al., 2023), as in the present study. Moreover, WM effects have been observed in complex (Faretta-Stutenberg & Morgan-Short, 2018), but not simple (Foote, 2011), WM tasks. Stronger WM effects have also been reported on non-adjacent than adjacent agreement (Reichle et al., 2013). Relevant to the present study, WM effects are more pronounced in lower- than higher-proficiency learners (e.g., Sagarra & Herschensohn, 2010). Huettig and Janse (2016) found that in Dutch L1 speakers, higher WM and faster processing speed predicted anticipatory eye movements. They concluded that WM connects language to space and time, linking linguistic and visuospatial representations. Although previous studies (Hed et al., 2019; Schremm et al., 2017) showed that training helped low-proficiency L2 learners become more sensitive to the predictive function of tone in Swedish, no WM measure was included in those studies. Accordingly, the aim of the present study was to shed light on how WM influences the effects of training a predictive prosodic cue, addressing an important gap in our understanding of individual differences in L2 predictive processing.

5. The Present Study

Our study explores whether beginner English users of Spanish benefit from digital gaming to detect stress–suffix associations and whether WM mediates this ability. Building on previous research showing that training can help L2 learners acquire tone–suffix associations in Swedish (Schremm et al., 2017; Hed et al., 2019), we examine whether training is similarly beneficial for other L2 linguistic features, particularly for suprasegmentals that exist in the L1 and L2 but carry more weight in the L2 than in the L1.

Our first research question is as follows: does game-based training improve the detection of stress–suffix associations in beginner English learners of Spanish? Based on Schremm et al.’s (2017) findings, we expected that the game would facilitate the learning of Spanish stress–suffix associations. Consequently, we anticipated higher accuracy and faster RTs over the testing period. We also examined how lexical stress (oxytones/paroxytones), syllabic structure (CV/CVC), and phonotactic probability affected learners’ performance in the game. We expected higher accuracy and faster RTs in conditions with fewer lexical competitors than those with more, specifically oxytone verbs, CVC verbs, and verbs with lower phonotactic probability. This prediction is based on the idea that paroxytones are the most frequent Spanish stress pattern and oxytones activate fewer lexical competitors. Additionally, we expected stress–suffix associations to be facilitated in verbs with a CVC pattern. Research by Sagarra and Casillas (2018) found that advanced English learners of Spanish use stress cues to make stress–suffix associations only in verbs with a first-syllable CVC structure, which is associated with reduced lexical competition. Furthermore, we hypothesized that target words with lower phonotactic probability would elicit higher accuracy and faster RTs. This prediction is grounded in the Neighborhood Activation Model (NAM) (Luce & Pisoni, 1998), which suggests that decreased lexical competition facilitates more efficient lexical access.

Our second research question is as follows: does WM mediate L2 learners’ ability to predict suffixes based on suprasegmental cues? Research indicates that beginner L2 learners with higher WM show greater sensitivity to L2 inflectional morphology than those with lower WM (e.g., Sagarra & Herschensohn, 2010). However, research with advanced learners shows that higher-WM learners need more time to predict oxytones (the stress type activating fewer lexical competitors) than lower-WM learners (Lozano-Argüelles et al., 2023). A substantial body of literature suggests that, in cognitively complex tasks, high-WM individuals activate all possible options (words or semantic interpretations), whereas low-WM individuals activate only one option—the most frequent and easiest (e.g., the option activating fewer competitors) (see MacDonald et al.’s (1992) seminal study). In Spanish, oxytone stress activates fewer lexical competitors than paroxytone stress because paroxytone stress is more frequent. CVC-initial syllables provide additional phonological information, which facilitates lexical access. As a result, we expected lower-WM learners to be more accurate and faster with oxytones and CVC verbs than with the other verb types, while higher-WM learners would have slower responses with these verb types due to the additional time required to consider multiple options and inhibit alternatives before selecting the correct one. However, we also expected that overall higher-WM learners would be more accurate than lower-WM learners, given findings that learners with higher WM show greater sensitivity to L2 inflectional morphology.

6. Methods

6.1. Participants

The study included 20 English learners of L2 Spanish, with an average age of 19 years (SD = 1.3). The participants were enrolled in beginner-level college courses for L2 Spanish. They had not lived abroad for more than one month, had an average age of acquisition of 11 years old (SD = 4.89), and had no or minimal knowledge of languages other than Spanish and English. Participants’ low level of proficiency, despite many years of exposure to Spanish, may be attributed to the fact that the most common type of foreign language program offered in U.S. public schools provides only introductory exposure to the language (Pufahl & Rhodes, 2011). The self-reported average level of Spanish proficiency on a scale of 1 to 10, with 1 indicating “very low” and 10 “perfect,” was 4, indicating “slightly less than average.” In line with their self-reported proficiency, participants scored low on the Lextale-Esp (Izura et al., 2014), a test measuring Spanish vocabulary size with scores that can range from −60 to 60, with an average score of 0.31 (SD = 14.62; range = −25 to 28). For comparison, in Izura et al. (2014), beginner learners of Spanish with only 2.5 months of L2 instruction had an average Lextale-Esp score of 7.2. Finally, participants achieved an average score of 4.5 (SD = 1.5; range = 2 to 7) on the backward Corsi task, a measure of WM with possible scores ranging from 0 to 9.

6.2. Materials

Digital game. The digital game (Fernandez, 2024), themed around dinosaurs, was developed using the Unity WebGL framework and hosted on a PlayFab Multiplayer Server. Screenshots of the game are shown in Figure 1. The website was optimized for computer browsers, and participants were instructed not to use mobile devices for gameplay. The game automatically collected and stored response data, including RTs and accuracy for each sentence item, as well as overall playtime, on the server.

Figure 1.

Digital game screenshots capturing the instant before and after a player chooses a suffix. The dinosaur avatar is shown moving onto the ña present-tense suffix, following the audio prompt of the sentence fragment La actriz da- ‘The actress da-.’ Upon selecting the suffix, participants hear the complete sentence (e.g., La actriz daña el vestido ‘The actress damages the dress’).

Stimuli. In the game, each item consisted of a carrier sentence in which the target verb appeared once with a present-tense suffix and once with a past-tense suffix, resulting in a total of 196 items (98 sentence pairs). Sentences were recorded in a soundproof booth by a female L1 speaker who was unaware of the experiment’s aim. Each sentence was read three times in pseudo-randomized sequences. The first take was discarded, and for each sentence pair, the best recording from either the second or third takes was selected, with both sentences in each sentence pair chosen from the same take.

After the selection of recordings, sentences were divided into two parts using Praat (Boersma & Weenink, 2018), cutting after the target verb’s first syllable at zero crossing points. In the game, participants heard the first part of each sentence and were asked to use the stress pattern of the target verb’s first syllable (stressed or unstressed) to select the correct suffix. All experimental sentences were five words long and followed the same syntactic structure, comprising a determiner, a subject noun, a 2-syllable target verb (in present or past tense), a determiner, and an object noun (e.g., La actriz daña/dañó el vestido, ‘The actress damages/damaged the dress’). Target verbs were repeated twice across sentences (e.g., the verb dañar ‘to damage’ also appeared in the sentence El jardinero daña/dañó la pared, ‘The gardener damages/damaged the wall’). All verbs were -ar regular verbs. Subjects and objects were not repeated across sentences and were counterbalanced for grammatical gender. Half of the experimental verbs had a CVC syllabic structure in the first syllable (salva/salvó, ‘he/she saves/saved’), and the remainder had a CV syllabic structure (seca/secó, ‘he/she dries/dried’). Items were presented in a randomized order across the levels of the game. Phonotactic probability was calculated for the first syllable of each target word using the Phonotactic Probability Calculator (PPC) in Spanish (Vitevitch & Luce, 2004). For example, for the verb secar ‘to dry’, the likelihood of the phonological segment /se/ appearing in the word-initial position was assessed. Our analysis of phonotactic probability revealed that CV verbs had significantly higher phonotactic frequencies (M = 0.0565; SD = 0.0282) than CVC verbs (M = 0.0505; SD = 0.0241), as indicated by a two-sample t-test, t(18,984) = 15.61, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.0052, 0.0067]. This difference was expected given that the extra information provided by the coda in CVC syllables reduces the number of phonotactic competitors in verbs with this syllable structure in the first syllable. One limitation of the phonotactic probability calculator (PPC: Vitevitch & Luce, 2004) is that it cannot account for differences in phonotactic frequency in verbs that have the same phonemes but differ in stress patterns.

Working memory test. The backward Corsi task (Corsi, 1972) was used to assess WM. We used a non-verbal measure of WM in order to avoid potential confounders associated with language-based WM tasks. Participants viewed an array of rectangles on a computer screen, highlighted sequentially, and were then asked to recall and replicate the highlighting sequence in reverse order. The backward Corsi span, i.e., the highest sequence length accurately completed, served as the participant’s WM score.

6.3. Procedure

Participants were informed about the aim and procedure of the study before providing consent to participate. They completed the following tasks in this order. In session 1, participants completed an eye-tracking pretest (10 min), a Spanish proficiency test (5 min), and a language background and use questionnaire (5 min). Then, participants were provided with a link to register for the digital game and played the game once a day for 10 to 15 min over 10 days within a two-week period. Participants completed the game in their home, with detailed instructions provided both before gameplay commenced and embedded within the game interface itself. Players’ progress was automatically saved so players could start where they left off each time they played. During gameplay, players heard the beginning part of sentence items until the end of the first syllable of the target word associated with the predictive cue. Two suffix options were displayed on platforms, and players used the up or down arrow keys to make a selection. After making a choice, participants were given feedback on whether their response was correct or incorrect. The complete, correct sentence was provided orally as well as in writing. We opted to provide feedback through recasts (i.e., the correct restatement of an incorrectly formed utterance, Nicholas et al., 2001) based on research indicating that recasts promote the L2 acquisition of morphology (e.g., Mifka-Profozic, 2015) and that the effects of recasts are more durable than those of other types of feedback (Li, 2010). To promote quick responses, a timer was prominently displayed on the screen’s top left corner. This timer transitioned in color from green to yellow to red, signaling the closing of the preferred 2000 millisecond (ms) response window. Although players could respond after this timeframe, the design encouraged faster reactions to enhance gameplay engagement. Moreover, to promote accuracy, players received coins for accurate responses under 2000 ms, redeemable at the “Dino Store” for avatar enhancements between levels. The game was structured into 12 levels; at the end of each level, players were shown a summary of their accuracy statistics as well as how their performance compared to other players in terms of points. Points were accumulated each time players responded quickly (i.e., under 2000 ms) and accurately. As in Schremm et al. (2017), participants had to achieve 80% accuracy to progress from one level to the next. However, whereas Schremm et al. automatically moved players to the next level if they spent too much time on a single level to ensure the game was completed within the study period, we opted against this approach. Our decision was informed by a pilot study, which indicated that players could successfully complete all 12 levels within the study period by playing the game for 10–15 minutes each day for 10 days. The difficulty of achieving 80% accuracy increased as players advanced, with the number of items increasing by 2 per level—from 5 items at Level 1 to 27 items at Level 12. Finally, participants completed an eye-tracking post-test (10 min), WM task (5 min), and a vocabulary and grammar task (5 min). Participants completed an eye-tracking pre-test and post-test to assess whether they could generalize what they had learned in the game to new instances. In each task, participants listened to sentences containing disyllabic Spanish verbs different from those included in the game while viewing the words presente (‘present’) and pasado (‘past’) on the screen. Eye movements were recorded to determine whether participants used stress cues to anticipate verb tense before hearing the suffix. The results are reported elsewhere.

7. Data Analysis

Data from the digital game were analyzed using generalized linear mixed models (GLMMs) and generalized additive mixed models (GAMMs). Data cleaning and statistical analyses were performed with R (R Core Team, 2023). Models were fit using the packages lme4 (Bates et al., 2015) and mgcv (Wood, 2023). RTs equal to 0 milliseconds (0.16% of all responses) or above 2000 milliseconds (7% of all responses) were excluded from all analyses. RTs were measured from the offset of the auditory presentation of the predictive cue to the moment the player selected one of the two suffixes. The raw data were processed to ensure normality and comparability across variables. Specifically, RTs and phonotactic frequency were log-transformed, and WM scores were standardized using z-scores.

The dependent variables were accuracy (binary: correct = 1, incorrect = 0) and log-transformed RTs. GLMMs with a binomial linking function were employed for accuracy, while GLMMs with a Gaussian linking function were used for log-transformed RTs. GAMMs were used to examine nonlinear relationships between the predictors and dependent variables across game levels. GAMMs are particularly useful for modeling nonlinear effects and complex interactions common in game-based learning contexts, where performance may change nonlinearly across different levels.

Predictors included the game level, lexical stress (oxytone/paroxytone), syllabic structure (CV/CVC), phonotactic frequency, and WM score. In the GLMMs, models were fitted for each fixed effect as well as for the two-way interaction between WM and verb type (the combination of stress and syllable structure) and the three-way interaction between WM, verb type, and level. In the GAMMs, smooth terms were fitted for the level and its interaction with stress, syllabic structure, and WM. All models included by-subject and by-item random intercepts to account for repeated measures.

The significance of predictors and interactions in GLMMs was assessed using regression coefficients (β-values), standard errors (SEs), and p-values. In the GLMMs, oxytone stress served as the baseline level for stress, and CV syllable structure was the baseline for syllable structure. The significance of smooth terms in GAMMs was evaluated using effective degrees of freedom (EDFs) and p-values. The alpha level was set to α = 0.05 for all analyses.

To assess the statistical power of our design, we conducted simulation-based power analyses using the simr package in R. These simulations were informed by effect sizes from Schremm et al. (2017), who observed increases in accuracy from 59.9% to 76.0% and decreases in reaction times from 1787 ms to 748 ms across gameplay. We simulated a +2% per-level increase in accuracy (logit scale) and fit a generalized linear mixed-effects model with random intercepts for participant and item. Power to detect the fixed effect of level was estimated at 87%, based on 100 simulations. For RTs, we simulated a −100 ms per-level decrease in raw RTs (log-transformed), fitted a linear mixed-effects model, and obtained 100% power to detect the learning slope. These analyses confirm that our design, with 20 participants each completing over 1000 trials, is well-powered to detect learning effects of comparable magnitude to those previously reported.

8. Results

8.1. Descriptive Statistics

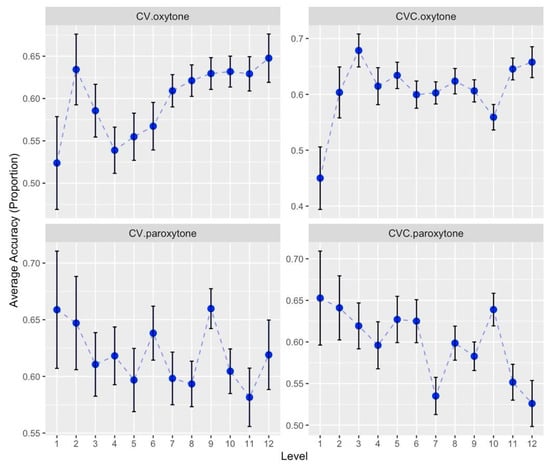

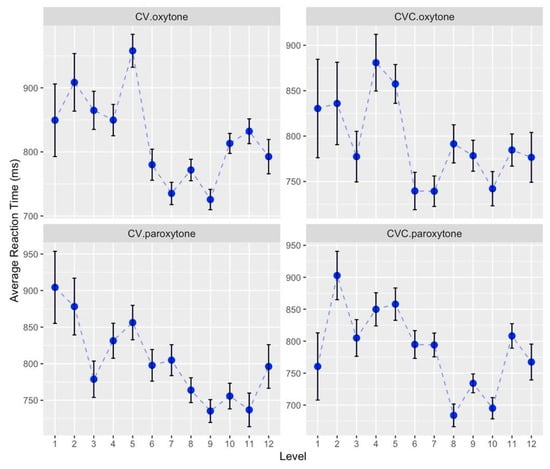

Descriptive statistics suggest an overall improvement in participants’ performance throughout the training, with more consistent gains observed in RTs than in accuracy. Average accuracy rates rose from 58% (SD = 0.50) at Level 1 to 62% (SD = 0.49) at Level 12, and RTs decreased from an average of 845 ms (SD = 482.31) at Level 1 to 803 ms (SD = 471.19) at Level 12. However, improvement varied across different item types (see Figure 2 and Figure 3). At Level 1, mean RTs were 832 ms (SD = 519.31) for CV oxytone, 839 ms (SD = 509.86) for CVC oxytone, 925 ms (SD = 455.15) for CV paroxytone, and 765 ms (SD = 424.09) for CVC paroxytone, with corresponding accuracy rates of 53% (SD = 0.50), 47% (SD = 0.50), 67% (SD = 0.47), and 66% (SD = 0.48), respectively. The highest accuracy rates were achieved at Level 12 for CV oxytone (65%, SD = 0.48) and CVC oxytone (67%, SD = 0.47), at Level 9 for CV paroxytone (66%, SD = 0.47), and initially at Level 1 for CVC paroxytone (66%, SD = 0.48). The fastest RTs were achieved at Level 9 for CV oxytone (728 ms, SD = 409.05), Level 6 for CVC oxytone (739 ms, SD = 414.37), Level 9 for CV paroxytone (738 ms, SD = 420.45), and Level 8 for CVC paroxytone (686 ms, SD = 424.99). See Figure 2 and Figure 3 for plots comparing average accuracy and RTs by item type across levels.

Figure 2.

Average accuracy by item type across levels. Error bars represent ±1 SE of the mean accuracy at each level.

Figure 3.

Average RT by item type across levels. Error bars represent ±1 SE of the mean within each level.

8.2. General Findings

The GLMMs revealed statistically significant effects for both accuracy and RTs: for accuracy, we found a significant interaction between the paroxytone CVC verb type and WM score (β = −0.301; SE = 0.124; p < 0.05) and a significant three-way interaction between the paroxytone CVC verb type, WM score, and game level (β = 0.030; SE = 0.014; p < 0.05), while for RTs, we observed a significant fixed effect of syllable structure (CVC) (β = −0.044; SE = 0.019; p < 0.05) and a significant interaction between the paroxytone CVC verb type and WM score (β = −0.128; SE = 0.053; p < 0.05). All other effects and interactions were not significant. The GAMMs also revealed several significant effects and interactions. Regarding accuracy, we found a significant nonlinear interaction of paroxytone stress and the level (EDFs = 3.675; p < 0.01) and a significant linear interaction of CV syllable structure and the level (EDFs = 1.010; p < 0.05). In the case of RTs, we observed a significant nonlinear effect of the level (EDFs = 7.073; p < 0.001), a significant nonlinear interaction of oxytone stress and the level (EDFs = 6.186; p < 0.001), a significant nonlinear interaction of paroxytone stress and the level (EDFs = 5.599; p < 0.001), a significant nonlinear interaction of CV syllable structure and the level (EDFs = 6.024; p < 0.001), a significant nonlinear interaction of CVC syllable structure and the level (EDFs = 5.755; p < 0.001), a significant nonlinear interaction of phonotactic probability and the level (EDFs = 8.052; p < 0.001), and a significant nonlinear interaction between the WM score and the level (EDFs = 5.334; p < 0.001). Summaries of the GLMMs and GAMMs are included in Appendix A and Appendix B.

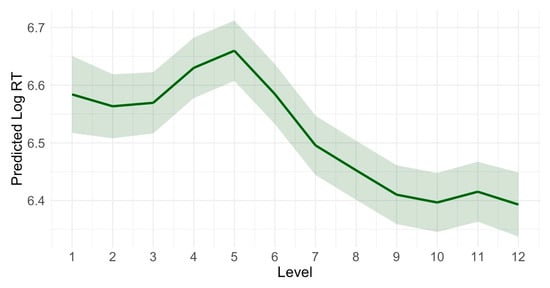

While we did not observe any significant effects of the level on accuracy, we did observe a significant nonlinear effect of the level on the RT (EDFs = 7.073; p < 0.001). Based on the prediction plot1 (see Figure 4), RTs initially decreased at the start of the game, from a predicted log-transformed RT of 6.6 (equivalent to approximately 735 ms) to 6.5 (about 665 ms) by Level 3. Although RTs increased slightly around Level 3, they decreased again to a predicted log-transformed RT of 6.5 by the middle of the game. By the end of the game, RTs further decreased to approximately 6.375 on the log scale, corresponding to about 587 ms.

Figure 4.

Predicted log-transformed RT across game levels.

8.3. The Impact of Lexical Stress, Syllabic Structure, and Phonotactic Probability on Learners’ Performance

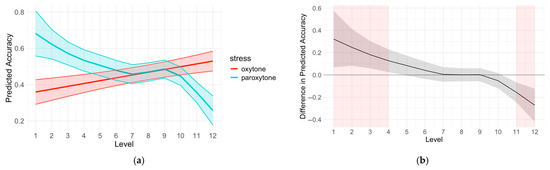

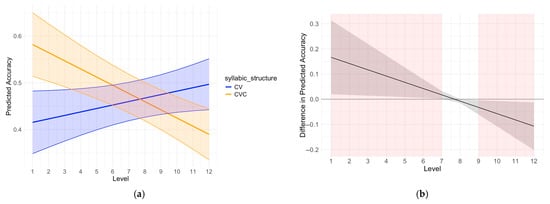

There was a significant nonlinear interaction of paroxytone stress and the level for accuracy (EDFs = 3.675; p < 0.01) but not for oxytone stress and the level (EDFs = 1.005; p = 0.07). Based on the prediction plot (see Figure 5a), at the start of the game, predicted accuracy for paroxytones was approximately 70%. By the middle of the game, accuracy had decreased to around 50%, and by the end of the game, it was approximately 25%. The difference smooth plot (see Figure 5b) reveals that from approximately Levels 1 to 3, accuracy for paroxytones was significantly higher than for oxytones. By around Level 11, this trend reversed, with oxytones showing significantly higher accuracy than paroxytones.

Figure 5.

(a) Predicted interaction between stress and level for accuracy across game levels; (b) difference smooth plot of stress (oxytone vs. paroxytone) across levels. Pink-shaded regions indicate level ranges where the modeled difference is significant.

There was a significant nonlinear interaction of oxytone stress and the level for the RT (EDFs = 6.186; p < 0.001), as well as an interaction of paroxytone stress and the level for the RT (EDFs = 5.599; p < 0.001). Based on the prediction plot (see Figure 6a), at the start of the game, RTs for oxytones were initially a predicted 6.56 on the log scale (approximately 706 ms), while RTs for paroxytones were initially slower, with a predicted log-transformed RT of 6.68 (approximately 796 ms). By the middle of the game, both oxytones and paroxytones had a predicted RT of approximately 6.6 on the log scale (equivalent to approximately 735 ms). By the end of the game, RTs had decreased for both oxytones and paroxytones, though oxytones had faster RTs (a predicted log-transformed RT of 6.35, approximately 572 ms) than paroxytones (a predicted log-transformed RT of 6.42, approximately 614 ms). However, the difference smooth plot (see Figure 6b) reveals no significant differences in RTs between paroxytones and oxytones.

Figure 6.

(a) Predicted interaction between stress and level on log-transformed RT across game levels; (b) difference smooth plot for stress (oxytone vs. paroxytone) across levels. Shaded regions indicate level ranges where the modeled difference is significant.

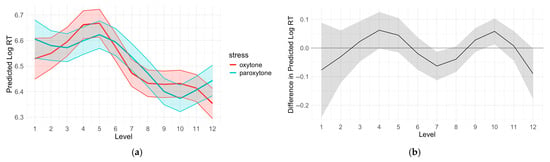

There was a significant linear interaction of CV syllable structure and the level for accuracy (EDFs = 1.010; p < 0.05), but no significant interaction between CVC syllable structure and the level (EDFs = 1.016; p = 0.2654). Based on the prediction plot (see Figure 7a), at the start of the game, predicted accuracy for CV verbs was approximately 40%. By the middle of the game, accuracy had increased to around 45%, and by the end of the game, it was approximately 50%. The difference smooth plot (see Figure 7b) shows that from approximately Levels 1 to 6, CVC verbs had significantly higher accuracy than CV verbs. However, by Level 9, this trend reversed, with CVC verbs showing significantly lower accuracy than CV verbs.

Figure 7.

(a) Predicted interaction between syllable structure and level for accuracy across game levels; (b) difference smooth plot of syllable structure (CV vs. CVC) across levels. Pink-shaded regions indicate level ranges where the modeled difference is significant.

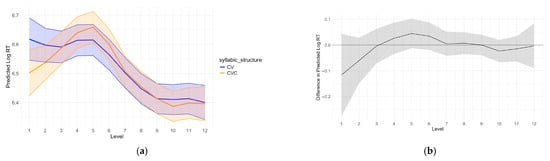

There was a significant nonlinear interaction of CV syllable structure and the level (EDFs = 6.024; p < 0.001) as well as an interaction of CVC syllable structure and the level (EDFs = 5.755; p < 0.001) for the RT. Based on the prediction plot (see Figure 8a), at the start of the game, RTs for CVC verbs were initially a predicted 6.54 on the log scale (approximately 692 ms), while RTs for CV verbs were initially slower, with a predicted log-transformed RT of 6.65 (approximately 773 ms). By the middle of the game, both CVC and CV verbs had a predicted RT of approximately 6.6 on the log scale (equivalent to approximately 735 ms). By the end of the game, RTs had decreased for both CVC and CV verbs, with a predicted log-transformed RT of 6.357 (approximately 577 ms). The difference smooth plot (see Figure 8b) indicates no significant differences in RTs between syllable structures across levels.

Figure 8.

(a) Predicted interaction between syllable structure and level for log-transformed RT across game levels; (b) difference smooth plot of syllable structure (CV vs. CVC) across levels. Shaded regions indicate level ranges where the modeled difference is significant.

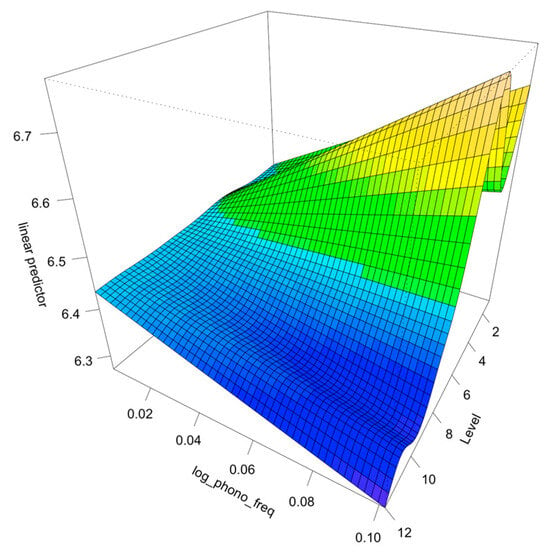

There was no significant interaction between the phonotactic probability and level for accuracy (EDFs = 2.015; p = 0.24). However, there was a significant nonlinear interaction of phonotactic probability and the level for the RT (EDFs = 8.052; p < 0.001). Based on the prediction plot (see Figure 9), for verbs with the lowest phonotactic probability, there was no observed relationship between the level and RT, with predicted log-transformed RTs remaining constant at approximately 6.42 (about 614 ms). However, verbs with higher phonotactic probability were associated with longer RTs at the start of the game, with a predicted log-transformed RT of approximately 6.65 (about 773 ms). By the middle of the game, these RTs had decreased to around 6.4 on the log scale (approximately 602 ms) and further decreased to 6.3 by the end of the game (approximately 545 ms), ultimately showing faster predicted RTs than those for verbs with lower phonotactic probability.

Figure 9.

Three-dimensional visualization of the interaction effect between the level and phonotactic probability on predicted RT (log-transformed). This figure illustrates the interaction between the level and phonotactic probability in predicting the log-transformed RT. The vertical axis represents the predicted log-transformed RT, where higher values indicate slower RTs and lower values indicate faster RTs. The color gradient, ranging from blue (faster RTs) to yellow (slower RTs), visually encodes the RT.

8.4. The Impact of WM on Learners’ Performance

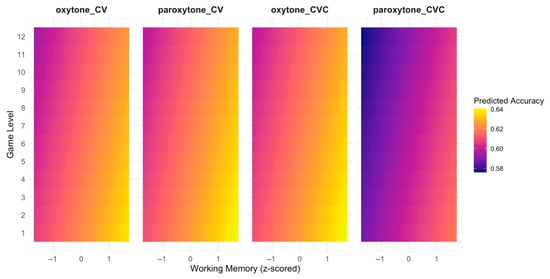

The GLMMs revealed a significant interaction between the paroxytone CVC verb type and WM score (β = −0.301; SE = 0.124; p < 0.05) and a significant three-way interaction between the paroxytone CVC verb type, WM score, and game level (β = 0.030; SE = 0.014; p < 0.05) for accuracy. We also observed a significant interaction between the paroxytone CVC verb type and WM score (β = −0.128; SE = 0.053; p < 0.05) for RTs. All other interactions were not significant (p > 0.05). The heat map for accuracy (see Figure 10), which uses a color gradient where higher predicted accuracy is represented by yellow and lower predicted accuracy by purple, shows that higher-WM learners tended to be more accurate than lower-WM learners across levels and conditions, although this difference was not significant. Higher-WM learners demonstrated a statistically significant larger drop in accuracy for paroxytone CVC verbs compared to oxytone CV verbs than lower-WM learners. However, for higher-WM learners, this drop became less pronounced at more advanced levels of the game.

Figure 10.

Heat map depicting predicted accuracy as a function of WM score, game level, and verb type. Predicted accuracy is represented by a color gradient, with higher values indicated by yellow and lower values indicated by purple.

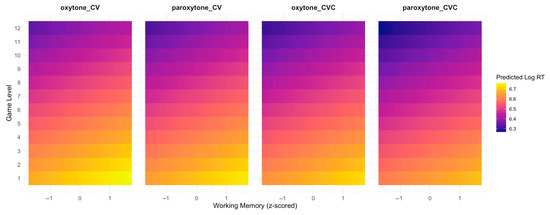

Similarly, the heat map (see Figure 11) for RTs in which yellow represents slower predicted RTs and purple represents faster RTs shows that, overall, learners’ RTs became faster as they progressed through the game. However, the difference in RTs between paroxytone CVC and oxytone CV verbs was more pronounced in higher-WM learners. Specifically, higher-WM learners had significantly faster RTs for paroxytone CVC verbs than oxytone CV verbs.

Figure 11.

Heat map depicting predicted RT as a function of WM score, game level, and verb type. Predicted accuracy is represented by a color gradient, with higher values indicated by yellow and lower values indicated by purple.

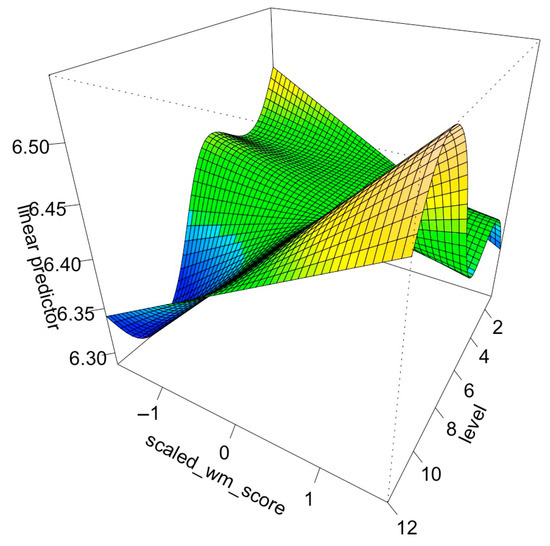

The GAMMs did not reveal a significant interaction between the WM score and level for accuracy (EDFs = 2.413; p = 0.451), but we did observe a significant nonlinear interaction between the WM score and level for RTs (EDFs = 5.334; p < 0.001). Based on the prediction plot shown in Figure 12, the effect of the level on RTs varied depending on the WM score. Participants with lower WM scores had slower RTs at the start of the game (6.5 on the log scale, approximately 665 ms), began being faster mid-game (6.45 on the log scale, approximately 633 ms), and became fastest by the end of the game (6.35 on the log scale, about 572 ms). In contrast, participants with higher WM scores demonstrated the fastest RTs at the beginning of the game (6.35 on the log scale, about 572 ms), then began being slower mid-game (6.4 on the log scale, approximately 602 ms), and became slower in a nonlinear pattern through the end of the game.

Figure 12.

Three-dimensional visualization of the interaction effect between the level and WM score on the predicted RT (log-transformed). This figure illustrates the interaction between the level and WM score in predicting the log-transformed RT. The vertical axis represents the predicted log-transformed RT, where higher values indicate slower RTs, and lower values indicate faster RTs. The color gradient, ranging from blue (faster RTs) to yellow (slower RTs), visually encodes the RT.

9. Discussion

The present study investigated whether beginner English learners of Spanish benefit from digital gaming to detect stress–suffix associations and whether WM facilitates their performance in the game. Our findings revealed that linguistic variables (i.e., word stress, syllabic structure, and phonotactic probability) and learners’ WM span significantly affected learning outcomes. Stress patterns influenced accuracy differently across gameplay, with oxytones showing improved accuracy but not paroxytones. Syllabic structure also affected performance patterns, with CVC verbs initially processed more accurately but showing less improvement over time than CV verbs. Phonotactic probability primarily impacted RTs, with high-probability verbs initially showing slower RTs but demonstrating the greatest improvements across gameplay. WM modulated both accuracy and speed, with higher-WM learners achieving greater accuracy across all conditions despite slower processing, while lower-WM learners processed information more quickly but with reduced accuracy. Overall, these findings suggest that linguistic variables and WM modulate the gains that beginner learners of Spanish make in acquiring stress–suffix associations with a digital game.

9.1. Lexical Stress, Syllable Structure, and Phonotactic Probability

Our first research question explored whether game-based training improves the detection of stress–suffix associations in beginner English L1 learners of L2 Spanish and whether learners would anticipate more accurately and faster with oxytone verbs, CVC verbs, and verbs with lower phonotactic probability. The hypothesis that learners would show higher accuracy and faster RTs over the testing period was partially supported. While learners did not show increased accuracy in all conditions with gameplay, participants did exhibit reduced RTs with increased gameplay.

Overall, our data diverge from prior studies that have reported stronger training gains—namely, faster and more accurate performance in the game—after training on an L2 suprasegmental cue absent in the L1 to predict upcoming suffixes (e.g., Schremm et al., 2017; Hed et al., 2019). In contrast, we observed more moderate gains with increased gameplay. Specifically, participants showed a faster but generally not more accurate performance in the acquisition of a suprasegmental predictive cue (lexical stress), which is acoustically realized distinctly and has a different functional load in the L1 (English) and L2 (Spanish). Since English primarily uses segmental cues (e.g., reduced vs. full vowels) to distinguish words (Cutler, 1986), it relies less on suprasegmental features like lexical stress than languages such as Spanish, where suprasegmentals carry a greater functional load in word recognition (Cutler & Pasveer, 2006). Our results are consistent with prior studies showing that L2 learners acquire linguistic forms absent in the L1 earlier than those that are similar but used differently (e.g., Tokowicz & MacWhinney, 2005). It has been suggested that forms that are similar but used distinctly are more challenging to acquire because learners often assume that the forms function in the same way in both languages, leading to L1-L2 interference (Tokowicz & MacWhinney, 2005). An alternative explanation for the more modest gains observed in the present study may relate to task design. Whereas previous studies maintained a constant number of items per level, our game increased the load from 5 items at Level 1 to 27 items at Level 12, making high accuracy progressively harder to attain. Nonetheless, the observed gains (limited gains in accuracy and overall gains in RTs) provide at least partial support for the revised Speech Learning Model (Flege & Bohn, 2021), which proposes that phonetic category formation is possible across the lifespan, irrespective of age of first exposure to an L2. Our results further build upon the model, suggesting that learners can also adapt to process a similar suprasegmental cue in a more native-like way when that cue is used differently in their L2. Given that it may be more challenging for L2 learners to acquire a suprasegmental predictive cue used distinctly in their L1, future research should explore whether learners require additional training to acquire these types of predictive cues.

Our hypothesis that higher accuracy and faster RTs would be observed for oxytone verbs, CVC verbs, and lower phonotactic probability verbs was partially supported. At the start of the game, paroxytone and CVC verbs showed higher accuracy than oxytone and CV verbs. However, by the end of the game, this pattern reversed, with accuracy for oxytone and CV verbs surpassing that of paroxytone and CVC verbs. RTs decreased similarly across all verb-type conditions, regardless of stress or syllabic structure. Phonotactic probability did not significantly affect accuracy across game levels. However, it did influence RTs. Verbs with the lowest phonotactic probability had faster RTs than verbs with the highest phonotactic probability at the beginning of the game. However, training did not appear to impact RTs for verbs with the lowest phonotactic probability as the game progressed. In contrast, verbs with the highest phonotactic probability initially showed the slowest RTs, but by the end of the game, they exhibited the fastest RTs. One possible explanation for the contradictory findings—higher accuracy for oxytone than paroxytone verbs but lower accuracy for CVC than CV verbs with increased gameplay—is that the facilitating effect of the extra phonological information provided by the coda in CVC verbs diminished over time as participants became accustomed to the task. In contrast, as participants became more attuned to using stress cues to predict verb suffixes, oxytone stress became increasingly salient and more facilitative. This is likely because oxytone stress is the marked pattern that stands out more compared to paroxytone stress, which is the default in Spanish and activates a greater number of lexical competitors. Regarding the findings on phonotactic probability, the lack of RT reduction for the lowest probability verbs with training may be explained by a ceiling effect. Specifically, the minimal lexical competition associated with these verbs likely limited the potential for further improvement in RTs, even with increased training. Our findings offer a nuanced perspective on the predictions of the Neighborhood Activation Model (NAM; Luce & Pisoni, 1998), which argues that processing is facilitated in words with fewer lexical competitors. Initially, verbs with fewer competitors were processed more efficiently, while those with more competitors had slower RTs, aligning with the NAM’s predictions. Yet the fact that high-phonotactic-probability verbs showed the greatest RT reductions with training, eventually becoming faster than lower-probability verbs, seems, at first glance, to contradict the NAM, as the model predicts inhibitory effects for words with many competitors. Given the participants’ low proficiency levels, an alternative explanation emerges: the learners may not have fully activated competing lexical representations due to their limited vocabulary and exposure to Spanish. This reduced lexical competition likely resulted in the inhibitory effects predicted with the NAM being less pronounced. Instead, the high phonotactic probability of these verbs may have facilitated processing as participants became more accustomed to them through training. This interpretation is supported by studies like Vitevitch et al. (1997), which found that lexical access can be facilitated for high-probability nonwords in auditory naming tasks. In our context, learners might have processed high-probability verbs similarly to nonwords with high-probability phonotactic patterns, benefiting from increased exposure during training. This familiarity with sound sequences could explain the faster RTs observed with training. Rather than contradicting the NAM, our findings suggest that the model’s predictions may interact with factors such as vocabulary size. Since the present study involved beginner L2 Spanish learners, their limited knowledge of L2 words may have limited the effects of phonotactic probability.

9.2. Working Memory

Our second research question examined whether WM mediated L2 participants’ ability to predict suffixes based on suprasegmental cues. Our expectation that lower-WM learners would be more accurate and faster with oxytones and CVC verbs than with other verb types, that higher-WM learners would be slower with oxytones and CVC verbs than lower-WM learners, and that higher-WM learners would be overall more accurate was partially supported. Overall, higher-WM learners were more accurate than lower-WM learners across all levels and conditions, while lower-WM learners were generally faster than higher-WM learners. This finding is consistent with evidence that higher-WM learners activate more options and need time to inhibit alternatives (e.g., Lozano-Argüelles et al., 2023), making them slower but also more accurate. Our findings are also in line with Huettig and Janse (2016), who reported that higher WM facilitated L1 prediction, suggesting that WM also supports L2 prediction. However, all learners were faster but less accurate with paroxytone CVC verbs compared to the other verb types. This is surprising given that CVC syllable structure should activate fewer lexical competitors than CV syllable structure, facilitating prediction. It appears that for the beginning L2 learners in this study, anticipating morphological information using stress cues was cognitively demanding regardless of WM capacity. There seemed to be a speed–accuracy tradeoff across all learners, even under conditions that should have facilitated prediction due to stress patterns or syllabic structures that activate fewer lexical competitors. Taken together, our WM data support L2 prediction models claiming that prediction is cognitively taxing and modulated by WM.

9.3. Pedagogical Implications

While training gains were more modest than those of previous studies examining the impact of training on the acquisition of predictive prosodic cues (e.g., Schremm et al., 2017; Hed et al., 2019), the observation of these gains is still promising. Beginner L2 learners struggle attending to new or different L2 prosodic cues, yet the importance of L2 prosody for L2 processing during comprehension is neglected in L2 classrooms (Gosselke Berthelsen & Roll, 2023). Digital games can be a valuable supplement to L2 classroom instruction by providing intensive practice to accelerate the detection of predictive cues. Language instructors could integrate such games into curricula as homework or in-class activities, while self-directed learners could use them for targeted practice of challenging structures. Digital games are also an integral part of language apps like Duolingo (16.2 million installations and 25 million users per month). These language apps are extremely popular, but research on their effectiveness is limited (e.g., Loewen et al., 2020). Language apps to learn Spanish are particularly important because Spanish is the second-most spoken language in the world (595 million speakers) and the U.S. (43 million speakers) and the first-most studied language in U.S. public schools (5.3 million Spanish learners). With regard to the design of our game, given that the game’s mechanics—designed to encourage both speed and accuracy—seemed to prioritize speed over accuracy, future versions could consider modifications that shift the focus more toward accuracy and include attention checks to mitigate the effects of fatigue or the development of response biases. Furthermore, future research should explore how digital games might enhance the acquisition of other challenging predictive cues across different L1-L2 combinations and with varying training durations, given that the potential of such games for developing predictive processing skills remains largely unexplored. Moreover, it is important to investigate whether learners can extrapolate the cue–target associations they have learned in training to new instances, for example, by using eye-tracking and electroencephalogram (EEG) (in progress).

10. Conclusions

The goal of the present study was to explore whether beginner English learners of Spanish benefit from digital gaming to promote the acquisition of stress–suffix associations and whether WM influences their performance in a predictive task. Beginner English learners of Spanish played a digital game designed to facilitate the learning of stress–suffix associations for 10 days, dedicating 10–15 minutes daily. They also completed a Spanish proficiency test (Lextale-Esp), a language background and use questionnaire, and a Corsi WM task. The findings revealed modest gains in acquiring stress–suffix associations through gameplay. Specifically, accuracy improvements were observed only for CV verbs and oxytones as participants advanced in the game. However, RTs decreased significantly across all conditions, indicating that learners became faster in detecting stress–suffix associations over time. Regarding WM, higher-WM learners had higher accuracy and slower RTs than lower-WM learners in all conditions, likely because they activated multiple options, evaluating and selecting the correct one at the cost of speed. These results suggest that linguistic factors such as lexical stress, syllable structure, and phonotactic probability, and learner variables like WM span modulate the effectiveness of digital gaming in promoting learners’ use of stress as an anticipatory cue to predict verb suffixes. These findings inform models proposing that prosody influences word activation and highlight the cognitive demands of L2 morphological processing.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.S. and K.F.; methodology, N.S. and K.F.; software, K.F.; validation, K.F.; formal analysis, K.F.; investigation, K.F.; resources, K.F.; data curation, K.F.; writing—original draft preparation, K.F.; writing—review and editing, N.S. and K.F.; visualization, K.F.; supervision, N.S. and K.F.; project administration, K.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Rutgers University (Project ID: 2020000216; Date of approval: 30 August 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in https://osf.io/3qzt7/ (accessed on 2 July 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. GLMM and GAMM Accuracy Summaries

Table A1.

Results of seven GLMMs to predict accuracy.

Table A1.

Results of seven GLMMs to predict accuracy.

| Response Variable | Smooth Terms (Fixed Effects and Interactions) | Fixed Effects and Interactions | Random Effects | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant ID | Sentence ID | |||||||

| Estimate | Std. Error | p-Value | Variance | Std. Deviation | Variance | Std. Deviation | ||

| Accuracy | Stress (paroxytone) | −0.044 | 0.049 | 0.377 | 0.019 | 0.139 | 0.072 | 0.269 |

| Accuracy | Syllable struct (CVC) | −0.041 | 0.049 | 0.405 | 0.019 | 0.139 | 0.072 | 0.269 |

| Accuracy | wm_score | 0.039 | 0.034 | 0.245 | 0.018 | 0.133 | 0.072 | 0.269 |

| Accuracy | log_phono_freq | 0.806 | 0.995 | 0.418 | 0.019 | 0.139 | 0.072 | 0.269 |

| Accuracy | wm_score: paroxytone CV | −0.078 | 0.126 | 0.537 | 0.018 | 0.134 | 0.070 | 0.265 |

| wm_score: oxytone CVC | −0.068 | 0.127 | 0.590 | |||||

| wm_score: paroxytone CVC | −0.306 | 0.124 | 0.014 * | |||||

| wm_score: paroxytone CV: level | 0.007 | 0.015 | 0.620 | |||||

| wm_score: oxytone CVC: level | 0.011 | 0.015 | 0.461 | |||||

| wm_score: paroxytone CVC: level | 0.030 | 0.014 | 0.037 * | |||||

Note. * p < 0.05.

Table A2.

Results of seven GAMMs to predict accuracy.

Table A2.

Results of seven GAMMs to predict accuracy.

| Response Variable | Smooth Terms (Fixed Effects and Interactions) | S(Fixed Effects and Interactions) | S(Participant ID) | S(Sentence ID) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EDF | Ref.df | F | EDF | Ref.df | F | EDF | Ref.df | F | ||

| Accuracy | s(Level) | 1.015 | 1.029 | 0.707 | 15.083 | 19 | 83.916 *** | 118.531 | 191 | 322.035 *** |

| Accuracy | s(Level, by = Stress, oxytone) | 1.005 | 1.01 | 3.296 | 15.058 | 19 | 83.803 *** | 118.157 | 191 | 319.152 *** |

| s(Level, by = Stress, paroxytone) | 3.675 | 4.554 | 14.401 ** | |||||||

| Accuracy | s(Level, by = syllable_struct, CV) | 1.016 | 1.032 | 1.29 | 15.147 | 19 | 86.03 ** | 118.155 | 191 | 319.55 *** |

| s(Level, by = syllable_struct, CVC) | 1.01 | 1.02 | 5.69 * | |||||||

| Accuracy | s(Level, by = wm_score) | 2.413 | 2.713 | 2.786 | 14.061 | 18 | 74.146 *** | 118.484 | 191 | 320.139 *** |

| Accuracy | s(Level, by = log_phono_freq) | 1.015 | 1.029 | 0.707 | 15.083 | 19 | 83.916 | 118.531 | 191 | 320.761 *** |

Note. EDF = effective degrees of freedom; Ref.df = reference number of degrees of freedom; *** p < 0.001; ** p < 0.01; * p < 0.05.

Appendix B. GAMM RT Summaries

Table A3.

Results of seven GLMMs to predict RTs.

Table A3.

Results of seven GLMMs to predict RTs.

| Response Variable | Smooth Terms (Fixed Effects and Interactions) | Fixed Effects and Interactions | Random Effects | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant ID | Sentence ID | |||||||

| Estimate | Std. Error | p-Value | Variance | Std. Deviation | Variance | Std. Deviation | ||

| log_rt_ms | Stress (paroxytone) | −0.019 | 0.019 | 0.324 | 0.040 | 0.199 | 0.009 | 0.096 |

| log_rt_ms | Syllable struct (CVC) | −0.044 | 0.019 | 0.019 * | 0.040 | 0.199 | 0.009 | 0.094 |

| log_rt_ms | wm_score | −0.051 | 0.189 | 0.791 | 0.041 | 0.202 | 0.009 | 0.096 |

| log_rt_ms | log_phono_freq | 0.153 | 0.377 | 0.686 | 0.040 | 0.199 | 0.009 | 0.097 |

| log_rt_ms | wm_score: paroxytone CV | −0.104 | 0.054 | 0.054 | 0.018 | 0.134 | 0.070 | 0.265 |

| wm_score: oxytone CVC | −0.099 | 0.054 | 0.069 | |||||

| wm_score: paroxytone CVC | −0.128 | 0.053 | 0.015 * | |||||

| wm_score: paroxytone CV: level | −0.004 | 0.006 | 0.511 | |||||

| wm_score: oxytone CVC: level | −0.007 | 0.006 | 0.300 | |||||

| wm_score: paroxytone CVC: level | −0.001 | 0.006 | 0.936 | |||||

Note. * p < 0.05.

Table A4.

Results of seven GAMMs to predict RTs.

Table A4.

Results of seven GAMMs to predict RTs.

| Response Variable | Smooth Terms (Fixed Effects and Interactions) | S(Fixed Effects and Interactions) | S(Participant ID) | S(Sentence ID) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EDF | Ref.df | F | EDF | Ref.df | F | EDF | Ref.df | F | ||

| log_rt_ms | s(Level) | 7.073 | 8.095 | 25.730 *** | 18.619 | 19.000 | 56.316 *** | 101.652 | 191.000 | 1.336 *** |

| log_rt_ms | s(Level, by = Stress, oxytone) | 6.186 | 7.310 | 16.085 *** | 18.616 | 19.000 | 55.774 ** | 100.968 | 191.000 | 1.303 *** |

| s(Level, by = Stress, paroxytone) | 5.599 | 6.727 | 16.141 *** | |||||||

| log_rt_ms | s(Level, by = syllable_struct, CV) | 6.024 | 7.158 | 13.891 *** | 18.618 | 19.000 | 56.189 *** | 101.911 | 191.000 | 1.322 *** |

| s(Level, by = syllable_struct, CVC) | 5.755 | 6.887 | 16.953 *** | |||||||

| log_rt_ms | s(Level, by = wm_score) | 5.334 | 6.33 | 5.191 *** | 17.605 | 18.000 | 52.182 *** | 102.908 | 191.000 | 1.384 *** |

| log_rt_ms | s(Level, by = log_phono_freq) | 8.052 | 9.078 | 21.485 *** | 18.608 | 19.000 | 55.081 *** | 101.515 | 190.000 | 1.337 *** |

Note. EDF = effective degrees of freedom; Ref.df = reference number of degrees of freedom; *** p < 0.001; ** p < 0.01.

Note

| 1 | A prediction plot displays model-estimated (fitted) values of the dependent variable, holding all other predictors constant. The shaded band marks the 95% confidence interval around those estimates. |

References

- Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B., & Walker, S. (2015). Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software, 67(1), 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boersma, P., & Weenink, D. (2018). Praat: Doing phonetics by computer [Computer software]. Available online: http://www.praat.org (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Bovolenta, G., & Marsden, E. (2021). Expectation violation enhances the development of new abstract syntactic representations: Evidence from an artificial language learning study. Language Development Research, 193–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrabaszcz, A., Winn, M., Lin, C. Y., & Idsardi, W. J. (2014). Acoustic cues to perception of word stress by English, Mandarin, and Russian speakers. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 57(4), 1468–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, N., Cutler, A., & Wales, R. (2002). Constraints of lexical stress on lexical access in English: Evidence from native and non-native listeners. Language and Speech, 45(3), 207–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corsi, P. M. (1972). Human memory and the medial temporal region of the brain [Unpublished doctoral dissertation, McGill University]. [Google Scholar]

- Cowan, N. (2017). The many faces of working memory and short-term storage. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 24(4), 1158–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutler, A. (1986). Forbear is a homophone: Lexical prosody does not constrain lexical access. Language and Speech, 29(3), 201–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutler, A. (2012). Native listening: Language experience and the recognition of spoken words. MIT Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutler, A., Dahan, D., & van Donselaar, W. (1997). Prosody in the comprehension of spoken language: A literature review. Language and Speech, 40(2), 141–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutler, A., & Pasveer, D. (2006). Explaining cross-linguistic differences in effects of lexical stress on spoken-word recognition. In R. Hoffman, & H. Mixdorff (Eds.), Speech prosody. TUD Press. [Google Scholar]

- DeKeyser, R. M., & Criado, R. (2012). Automatization, skill acquisition, and practice in second language acquisition. In C. Chapelle (Ed.), The encyclopedia of applied linguistics (pp. 4501–4504). Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durand López, E. M. (2021). Morphological processing and individual frequency effects in L1 and L2 Spanish. Lingua, 257, 103093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dussias, P. E., Kroff, J. R. V., Tamargo, R. E. G., & Gerfen, C. (2013). When gender and looking go hand in hand: Grammatical gender processing in L2 Spanish. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 35(2), 353–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Face, T. L. (2005). Syllable weight and the perception of Spanish stress placement by second language learners. Journal of Language and Learning, 3(1), 90–103. [Google Scholar]

- Faretta-Stutenberg, M., & Morgan-Short, K. (2018). The interplay of individual differences and context of learning in behavioral and neurocognitive second language development. Second Language Research, 34(1), 67–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, K. (2024). Dinosaur verb game. Available online: https://testenvdinosaur-game.web.app (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- Flege, J. E., & Bohn, O.-S. (2021). The revised speech learning model (SLM-r). In Second language speech learning (pp. 3–83). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foltz, A. (2021). Using prosody to predict upcoming referents in the L1 and the L2: The role of recent exposure. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 43(4), 753–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foote, R. (2011). Integrated knowledge of agreement in early and late English–Spanish bilinguals. Applied Psycholinguistics, 32(1), 187–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosselke Berthelsen, S., Horne, M., Brännström, K. J., Shtyrov, Y., & Roll, M. (2018). Neural processing of morphosyntactic tonal cues in second-language learners. Journal of Neurolinguistics, 45, 60–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosselke Berthelsen, S., Horne, M., Shtyrov, Y., & Roll, M. (2022). Native language experience shapes pre-attentive foreign tone processing and guides rapid memory trace build-up: An ERP study. Psychophysiology, 59(8), e14042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosselke Berthelsen, S., & Roll, M. (2023). Computer-Aided L2 prosody acquisition and its potential in second language learning. ASLA:s Skriftserie, 30, 157–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grüter, T., Lew-Williams, C., & Fernald, A. (2012). Grammatical gender in L2: A production or a real-time processing problem? Second Language Research, 28(2), 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamrick, P., & Pandža, N. B. (2014). Competitive lexical activation during ESL spoken word recognition. International Journal of Innovation in English Language Teaching and Research, 3(2), 159–177. [Google Scholar]

- Hed, A., Schremm, A., Horne, M., & Roll, M. (2019). Neural correlates of second language acquisition of tone-grammar associations. The Mental Lexicon, 14(1), 98–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, L. L., & Lotto, A. J. (2006). Cue weighting in auditory categorization: Implications for first and second language acquisition. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 119(5), 3059–3071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopp, H. (2013). Grammatical gender in adult L2 acquisition: Relations between lexical and syntactic variability. Second Language Research, 29(1), 33–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hualde, J. I. (2005). The sounds of Spanish with audio CD. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Huettig, F. (2015). Four central questions about prediction in language processing. Brain Research, 1626, 118–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huettig, F., & Janse, E. (2016). Individual differences in working memory and processing speed predict anticipatory spoken language processing in the visual world. Language, Cognition and Neuroscience, 31(1), 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, K., & Speer, S. R. (2008). Anticipatory effects of intonation: Eye movements during instructed visual search. Journal of Memory and Language, 58, 541–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izura, C., Cuetos, F., & Brysbaert, M. (2014). Lextale-Esp: A test to rapidly and efficiently assess the Spanish vocabulary size. Psicológica, 35(1), 49–66. [Google Scholar]

- Kaan, E., & Grüter, T. (2021). Prediction in second language processing and learning: Advances and directions. In E. Kaan, & T. Grüter (Eds.), Prediction in second language processing and learning (pp. 1–24). John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutas, M., DeLong, K. A., & Smith, N. J. (2011). A look around at what lies ahead: Prediction and predictability in language processing. In M. Bar (Ed.), Predictions in the brain: Using our past to generate a future (pp. 190–207). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S. (2010). The effectiveness of corrective feedback in SLA: A meta-analysis. Language Learning, 60(2), 309–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loewen, S., Isbell, D. R., & Sporn, Z. (2020). The effectiveness of app-based language instruction for developing receptive linguistic knowledge and oral communicative ability. Foreign Language Annals, 53(2), 209–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, G. (2007). The role of the lexicon in learning second language stress patterns. Applied Language Learning, 17(1/2), 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Lozano-Argüelles, C., Sagarra, N., & Casillas, J. (2023). Interpreting experience and working memory effects on L1 and L2 morphological prediction. Frontiers in Language Sciences, 1, 1065014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luce, P. A., & Pisoni, D. B. (1998). Recognizing spoken words: The neighborhood activation model. Ear and Hearing, 19, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, M. C., Just, M. A., & Carpenter, P. A. (1992). Working memory constraints on the processing of syntactic ambiguity. Cognitive Psychology, 24(1), 56–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mifka-Profozic, N. (2015). Effects of corrective feedback on L2 Acquisition of tense-aspect verbal morphology. LIA: Language, Interaction and Acquisition, 6(1), 149–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsugi, S., & MacWhinney, B. (2015). The use of case marking for predictive processing in second language Japanese. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 19(1), 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Font, A. (2014). El acento. In R. A. Nuñez, S. Colina, & T. G. Bradley (Eds.), Fonología generativa contemporánea de la lengua Española (pp. 235–265). Georgetown University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura, C., Arai, M., & Mazuka, R. (2012). Immediate use of prosody and context in predicting a syntactic structure. Cognition, 125(2), 317–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholas, H., Lightbown, P. M., & Spada, N. (2001). Recasts as feedback to language learners. Language Learning, 51(4), 719–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, D., Cutler, A., McQueen, J. M., & Butterfield, S. (2006). Phonological and conceptual activation in speech comprehension. Cognitive Psychology, 53(2), 146–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Llebaria, M., Gu, H., & Fan, J. (2013). English speakers’ perception of Spanish lexical stress: Context-driven L2 stress perception. Journal of Phonetics, 41(3–4), 186–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdomo, M., & Kaan, E. (2021). Prosodic cues in second-language speech processing: A visual world eye-tracking study. Second Language Research, 37(2), 349–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pufahl, I., & Rhodes, N. C. (2011). Foreign language instruction in U.S. schools: Results of a national survey of elementary and secondary schools. Foreign Language Annals, 44(2), 258–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. (2023). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 15 March 2024).

- Reichle, R. V., Tremblay, A., & Coughlin, C. E. (2013). Working-memory capacity effects in the processing of non-adjacent subject-verb agreement: An event-related brain potentials study. In Selected proceedings of the 2011 second language research forum. Cascadilla Proceedings Project. [Google Scholar]

- Rızaoğlu, F., & Gürel, A. (2020). Second language processing of English past tense morphology: The role of working memory. International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching, 60(3), 825–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roll, M., Söderström, P., Mannfolk, P., Shtyrov, Y., Johansson, M., van Westen, D., & Horne, M. (2015). Word tones cueing morphosyntactic structure: Neuroanatomical substrates and activation time-course assessed by EEG and fMRI. Brain and Language, 150, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saffran, J. R., Johnson, E. K., Aslin, R. N., & Newport, E. (1999). Statistical learning of tone sequences by human infants and adults. Cognition, 70(1), 27–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sagarra, N., & Casillas, J. V. (2018). Suprasegmental information cues morphological anticipation during L1/L2 lexical access. Journal of Second Language Studies, 1(1), 31–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagarra, N., & Herschensohn, J. (2010). The role of proficiency and working memory in gender and number agreement processing in L1 and L2 Spanish. Lingua, 120(8), 2022–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schremm, A., Hed, A., Horne, M., & Roll, M. (2017). Training predictive L2 processing with a digital game: Prototype promotes acquisition of anticipatory use of tone-suffix associations. Computers & Education, 114, 206–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schremm, A., Söderström, P., Horne, M., & Roll, M. (2016). Implicit acquisition of tone-suffix connections in L2 learners of Swedish. The Mental Lexicon, 11(1), 55–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Faraco, S., Sebastián-Gallés, N., & Cutler, A. (2001). Segmental and suprasegmental mismatch in lexical access. Journal of Memory and Language, 45(3), 412–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Söderström, P., Horne, M., & Roll, M. (2017). Stem tones pre-activate suffixes in the brain. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research, 46, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokowicz, N., & MacWhinney, B. (2005). Implicit and explicit measures of sensitivity to violations in second language grammar: An event-related potential investigation. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 27(2), 173–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, A. (2008). Is second language lexical access prosodically constrained? Processing of word stress by French Canadian second language learners of English. Applied Psycholinguistics, 29(4), 553–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, A., Broersma, M., & Coughlin, C. E. (2017). The functional weight of a prosodic cue in the native language predicts the learning of speech segmentation in a second language. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 21(3), 640–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitevitch, M. S., & Luce, P. A. (1998). When words compete: Levels of processing in perception of spoken words. Psychological Science, 9(4), 325–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitevitch, M. S., & Luce, P. A. (1999). Probabilistic phonotactics and neighborhood activation in spoken word recognition. Journal of Memory and Language, 40(3), 374–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitevitch, M. S., & Luce, P. A. (2004). Spanish phonotactic probability calculator. Department of Psychology, University of Kansas. Available online: https://calculator.ku.edu/phonotactic/Spanish/words (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- Vitevitch, M. S., Luce, P. A., Charles-Luce, J., & Kemmerer, D. (1997). Phonotactics and syllable stress: Implications for the processing of spoken nonsense words. Language and Speech, 40(1), 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitevitch, M. S., Luce, P. A., Pisoni, D. B., & Auer, E. T. (1999). Phonotactics, neighborhood activation, and lexical access for spoken words. Brain and Language, 68(1–2), 306–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitevitch, M. S., Stamer, M. K., & Sereno, J. A. (2008). Word length and lexical competition: Longer is the same as shorter. Language and Speech, 51(4), 361–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, A., Grice, M., & Crocker, M. W. (2006). The role of prosody in the interpretation of structural ambiguities: A study of anticipatory eye movements. Cognition, 99, B63–B72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]