Mastery, Modality, and Tsotsil Coexpressivity

Abstract

1. Mastery

“ritual speech” and “denunciatory speech.” These terms distinguish what we would consider to be two different contexts for the same speech phenomenon, but which I would venture Zinacantecs consider as a single context. Entries labeled “ritual” or “denunciatory” speech invariably form a part of traditional couplets or blocks of speech which, according to the occasion, may be used during ritual activities at home, in church, or at a mountain shrine when addressing the gods or may be used in self-righteous declamations at home or at the courthouse.

| Example 1 | a | `al-b-on | j-k’an-tik | // | |||

| say-APP-1A-(IMP) | 1E-want-PL | ||||||

| ‘What we want is for you to tell him for me.’ | |||||||

| b | j-ch’amun | av-e | j-k’an-tik | // | |||

| 1E-borrow | 2E-mouth | 1E-want-PL | |||||

| ‘What we want is that I borrow your mouth.’ | |||||||

| c | tsits-b-on | j-k’an-tik | |||||

| punish-APP-1A | 1E-want-PL | ||||||

| ‘What we want is that you punish him for me.’ | |||||||

| d | k’u | `onox | ti | `animal | ch-i-s-maj-e | // | |

| what | always | CONJ | lots | ICP-1A-3E-hit-CL | |||

| ‘How is it that he so often beats me?’ | |||||||

| e | k’u | `onox | ti | `animal | ch-i-y-ute-e | ||

| what | always | CONJ | lots | ICP-1A-3E-scold-CL | |||

| ‘How is it that he so often scolds me?’ | |||||||

2. Coexpressivity

3. Coexpressivity, Multimodality, and Master Speakers

| Example 2 | a. | `ali | ja` | yech | 0-k-a`i | lo`il | noxtok | `ali: | ||

| ART | ¡ | thus | CP-1E-hear | story | also | ART | ||||

| I heard a story like that | ||||||||||

| b. | vo`ne | |||||||||

| long_ago | ||||||||||

| a long time ago. | ||||||||||

| c. | `oy | jun | `ulo` | |||||||

| exist | one | visitor | ||||||||

| There was a guy from Chamula.7 | ||||||||||

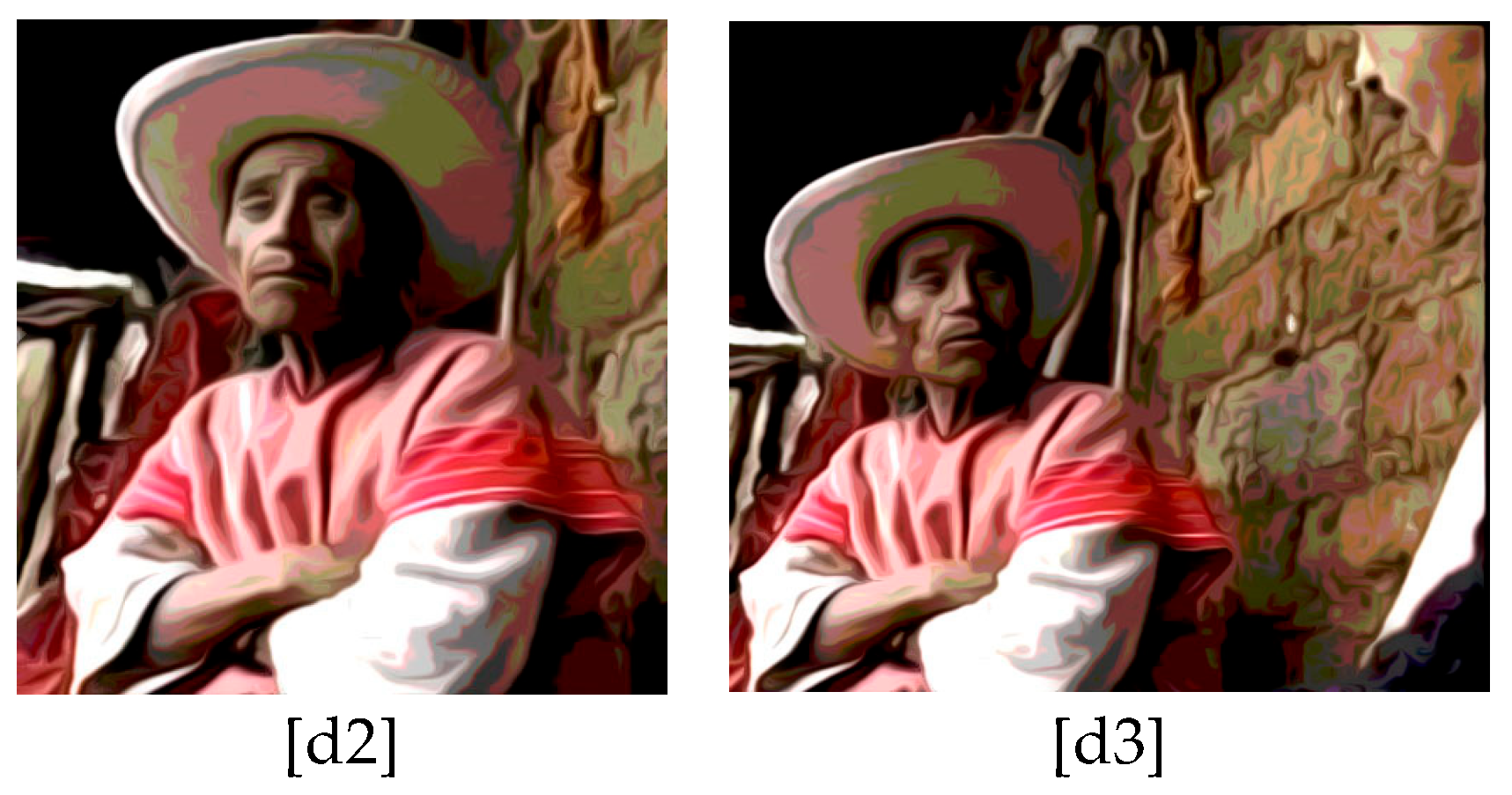

| [d0] | [d1] | [d2] | [d3] | |||||||

| d. | i-0-k’ot | li` | ta | bak’o | yo` | s-na | li | y-ajval | toch’-e | |

| CP-3A-arrive | here | PREP | bridge | where | 3E-house | ART | 3E-lord | Toch’-CL | ||

| He arrived here at the bridge where the lord of Toch’ has his house.’ | ||||||||||

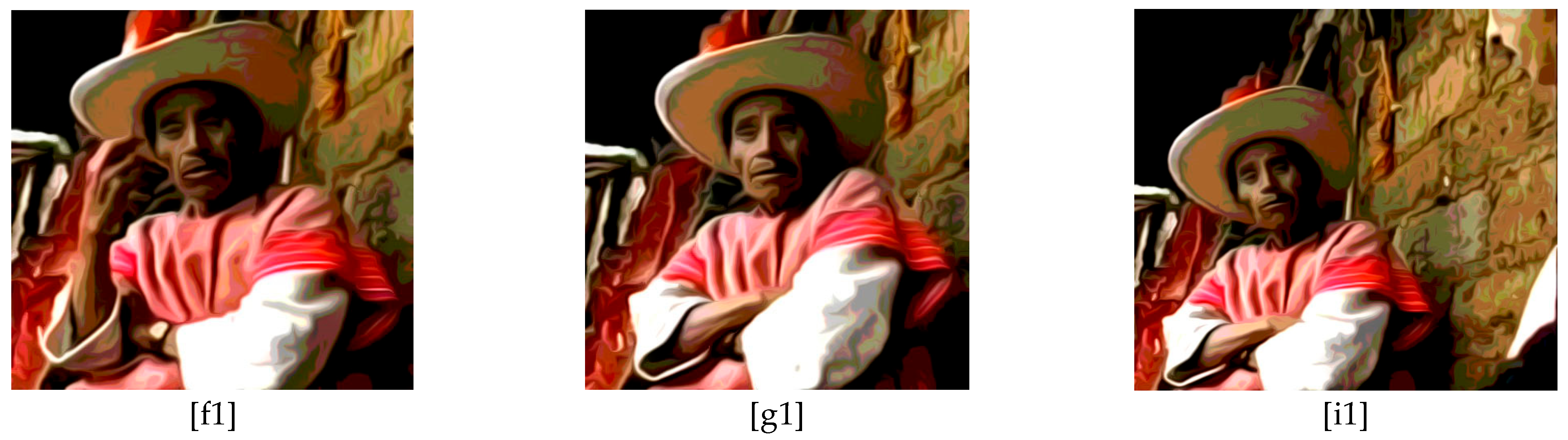

| Example 3 | [f1] | ||||||

| f | ts-k’o:j | ti`na | li | `ulo`-e | |||

| ICP.3E-knock | door | ART | visitor-CL | ||||

| The Chamula knocked on the door | |||||||

| [g1] | |||||||

| g | j-na`-tik | mi | i-0-muy | xa- | `ali | ||

| 1E-know-1PLInc | Q | CP-3A-go_up | already | uh- | |||

| Who knows if he went up…? | |||||||

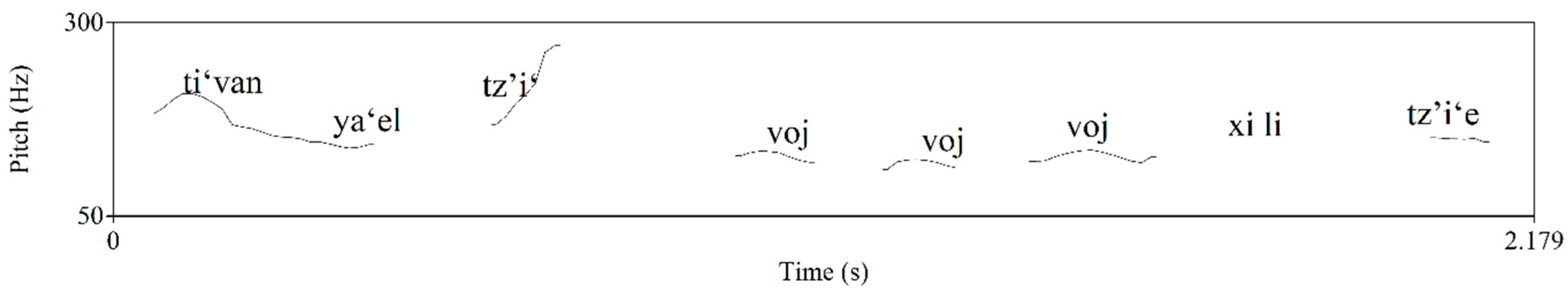

| h | ti`van | ya`el | ts’i` | ||||

| bark | EVID | dog | |||||

| A dog barked. | |||||||

| [i1] | |||||||

| i | voj | voj | voj | xi | li | ts’i`-e | |

| woof | woof | woof | said | ART | dog-CL | ||

| ‘‘Woof, woof, woof,” said the dog. | |||||||

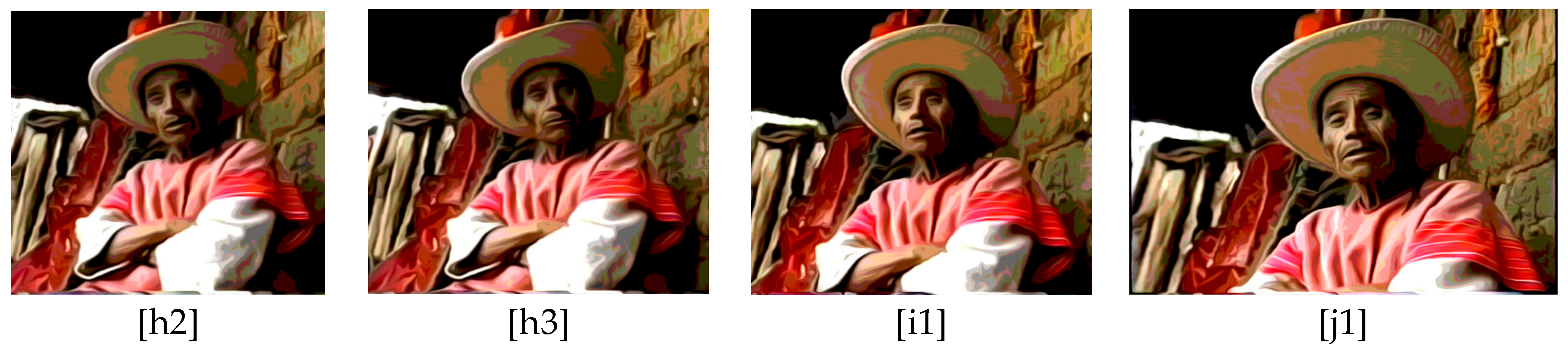

| Example 4 | [h1] [h2] | [h3] | |||||

| h | i:-0-lok’ | xa | tal | jun | muchacho | un | |

| CP-3A-exit | already | DIR | one | boy | CL | ||

| “A boy came out.” | |||||||

| [i1] | |||||||

| i | k’u | ch-a-sa` | xi | la | |||

| what | ICP-2E-search | said | EVID | ||||

| “What are you looking for?” he apparently said. | |||||||

| [j1] | |||||||

| j | Mi | li` | `ajvalil-e | xi | |||

| INT | here | boss-CL | said | ||||

| “Is the boss here?” he said. | |||||||

| k | k’u | ch-av-al | xi | ||||

| What | ICP-2E-say | said | |||||

| “What do you have to say?” he said. | |||||||

| [l1] | |||||||

| l | Ta | j-jak’ | mi | `oy | `abtel | xi | |

| ICP | 1E-ask | INT | EXIST | work | said | ||

| “I want to ask if there’s work,” he said. | |||||||

| [m1] | |||||||

| m | `Aa | xi | |||||

| Ah | Said | ||||||

| “Oh,” he said. | |||||||

| [n1] | |||||||

| n | Mala-o | j-likel-uk | xi | la | taj | muchacho-e | |

| Wait-IMP | one-moment-SUBJ | said | EVID | that | boy-CL | ||

| “Wait a second,” said that boy evidently. | |||||||

| [o1] | |||||||

| o | Ba | s-jak`-be | tal | taj | `ajvalil | ||

| AUX | 3E-ask-APP | DIR | that | boss | |||

| He went to ask the boss. | |||||||

4. Family Battles, Captured on Audiotape

| Example 5 | a. | bats’i | `ak’-o | pertonal | j-set’-uk | ||

| truly | give-IMP | pardon | 1-little-SUBJ | ||||

| Really give pardon for a little | |||||||

| b. | k-unen | sikil | `a`al | kumpa | |||

| 1E-small | cold | water | compadre | ||||

| Of my little cold water, compadre | |||||||

| c. | li` | ch-a-j-k’opon-e: | |||||

| here | ICP-2A-1E-speak-CLIT | ||||||

| That I have come to talk to you with. | |||||||

| e. | ch-a-j-k’an-be | pavo:r | |||||

| ICP-2A-1E-want-APP | favor | ||||||

| I want a favor from you | |||||||

| f. | k’usi | x-’elan | x-a-na:` | mi | |||

| what | ASP-be | ASP-2E-know | INT | ||||

| What do you think? | |||||||

| g. | mi | ja` | no`ox | mu | x-a-`abola:j | xa- | |

| INT | ¡ | only | NEG | ASP-2A-do_favor | ASP-2A- | ||

| Won’t you just please | |||||||

| h. | x-a- | tak-b-on | ta | `ik’-el | j-krem-oti:k | ||

| ASP-2E- | send-APP-1A | PREP | bring-NOM | 1E-boy-PL | |||

| send to have my boys brought in | |||||||

| i. | lavi | x-`elan | y-a`el | ti: | kap-em-ik | y-a`el | |

| now | ASP-be | 3E-seem | CONJ | angry-PERF-PL | 3E-seem | ||

| For the way they now seem to be angry | |||||||

| Example 6 | a | `ak’-o | bat-u:k | |

| give-IMP | go-SUBJ | |||

| “Let him go!” | ||||

| b | kuch-be | `onox | junabi: | |

| carry-APP | anyway | last_year | ||

| “I already carried it for him last year.” | ||||

| c | xi | la | un | |

| said | EVID | CL | ||

| So he said, I hear. | ||||

5. Coexpressivity and Speech

“Affective verbs are used characteristically in narrative description with a certain gusto, a desire to convey a vivid impression. They have dash”.

“At least one semantic property is common to all affect verbs: they are vividly descriptive. A considerable number of these verbs denote loud or noticeable noises (gurgling, hissing, clucking, howling, banging, and the like), salient physical characteristics (baldness, fatness, length of hair, facial expressions, and so forth), distinctive positions of the body (leaning, bending over, sitting with legs stretched out, etc.), or periodic motion (circling, rippling, flickering, running and ducking, and so on); affect verbs in -luj/-lij describe sudden events. These are all well adapted to colorful description. It is significant that many of the examples [of “affect verbs”] in Laughlin’s texts exhibit lengthening of a vowel for rhetorical effect”.

“Overall, affect verbs seem to convey connotations of intensity, duration, repetition, or other characteristics of an event that attract the speaker’s attention as being deviant with respect to some implicit norm or expectation. At the same time, affect verbs also convey emotional, affective connotations, i.e., the speaker’s psychological reaction (of surprise, amusement, puzzlement, and the like) to the unexpected, deviant-from-the-norm, character of a given event”.

“[w]hile referential, denotative meaning is unquestionably present in these words, they are used to serve a purpose that is not purely referential, but also expressive: to both describe a state of affairs and comment upon it by conveying one’s psychological reaction to it”.

6. The Brides of the Underworld

| Example 7 | [6a]] | [6b]] | ||||||

| 6 | t’uj-o | av-ajnil | xi | la | ||||

| pick-IMP | 2E-wife | said | EVID | |||||

| “Pick out a wife,” he said. | ||||||||

| [7a]] | ||||||||

| 7 | lavi | chol-ol | li | tseb-e | li` | |||

| now | lined_up-PRED | ART | girl-CL | here | ||||

| Right now, the girls are lined up here. | ||||||||

| 8 | t’uj-o | much’u | junukal | lek | s-verte | ch-0-k’ot | av-u`un-e | |

| pick-IMP | who | one | good | 3E-luck | ICP-3ª-arrive | 2E-belong-CL | ||

| Pick which one of them you will turn out to have good luck with. | ||||||||

| 9 | lek | muk’-tik | tseb-etik | xi | la | |||

| good | big-PL | girl-PL | said | EVID | ||||

| “They’re good full-grown girls,” he said. | ||||||||

| Example 8 | [10a]] | |||||||

| 10 | ejj, | mu | j-na` | me- | mi | x-i-nop | ya`el-e, | |

| mmm | NEG | 1E-know | EVID | INT | ASP-1A-think | it_seems | ||

| “Hmm, I really don’t know if I am getting used to it.” | ||||||||

| 11 | mu | x-i-nop | ya`el | |||||

| NEG | ASP-1A-accustom | seems | ||||||

| “I don’t think I am going to get accustomed.” | ||||||||

| 12 | t’uj-o: | |||||||

| pick-IMP | ||||||||

| “Pi:ck one.” | ||||||||

| Example 9 | [11a] | [11b] | ||||||

| 11 | tseb-etik-e | naka | xa | 0-tse`in-ik | xa | tajmek | `un | |

| girl-PL-CL | just | already | 3A-smile-PL | already | very | CL | ||

| The girls were already just there smiling. | ||||||||

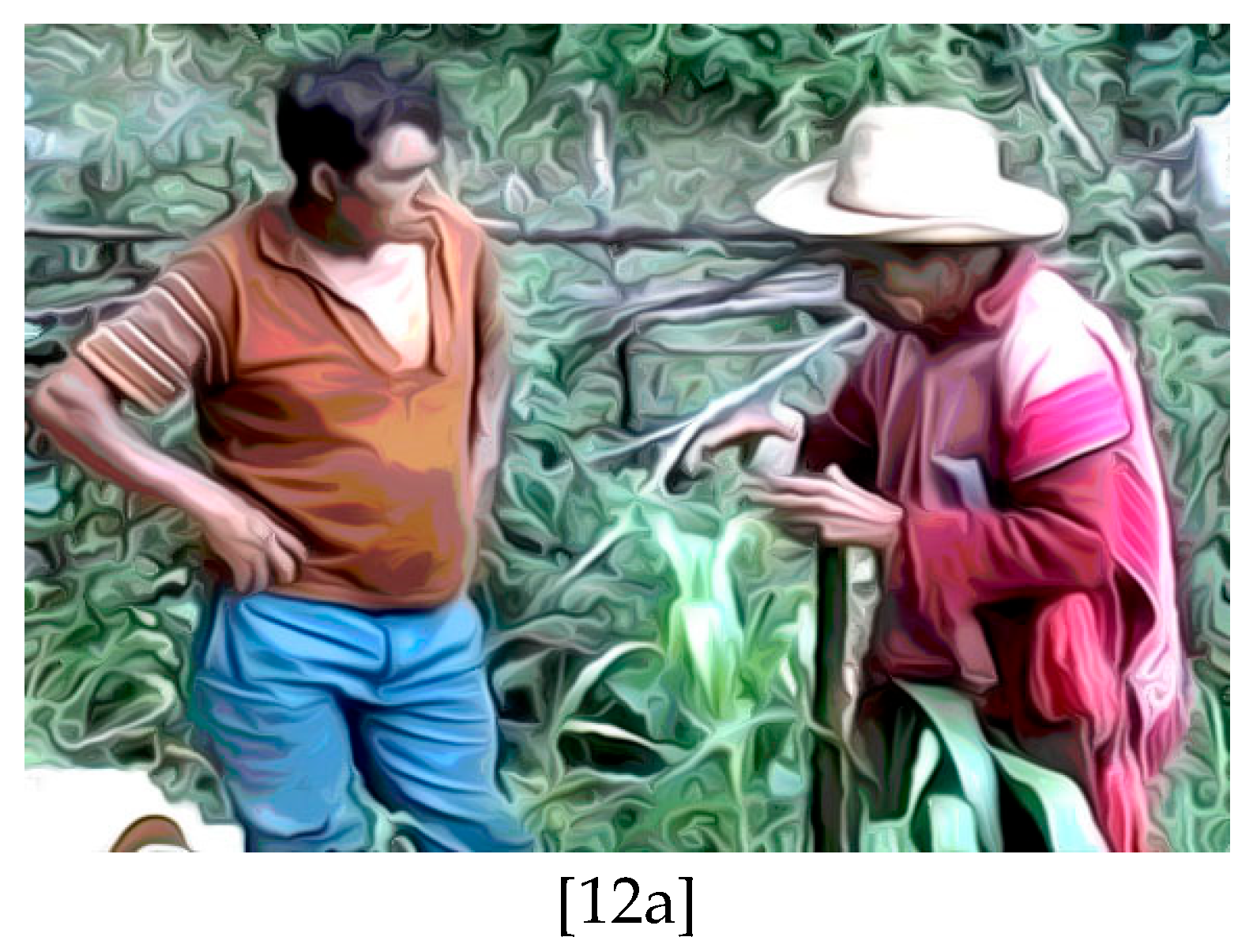

| [12a] | [12b] | |||||||

| 12 | v-a`i | `ali | `ali | jkobel | `ali- | |||

| 2A-hear | ART | ART | fucking | ART | ||||

| So, they were –uh—fucking uh- | ||||||||

| [13a] | ||||||||

| 13 | k’usi | puta | chanul, | sapo | `un-e | |||

| what | whore | animal | toad | CL-CL | ||||

| What are the damn animals called, toads | ||||||||

| 14 | ja` | li | muk’-tik | sapo | `ali | |||

| ¡ | ART | large-PL | toad | uh | ||||

| They were those big toads, uh | ||||||||

| Example 10 | [15a] | ||||||

| 15 | ali | jkobel | jenjen | x-0-ut-ik | |||

| ART | fucking | “jen jen” | ASP-3E-tell-PL | ||||

| Uh, those fucking “jen jen” (people) call them. | |||||||

| [16a] | |||||||

| 16 | mol-ik | xi | chot-ajtik | ta | balamil | ||

| big-PL | thus | seated-PL | PREP | ground | |||

| Big as this, sitting on the ground. | |||||||

| [17a]] | |||||||

| 17 | jenjen-il | sapo-etik | `un-e | ||||

| ‘jenjen’-SUF | toad-PL | CL-CL | |||||

| ‘Jenjen’ type toads, that is. | |||||||

| 18 | ji` | la | |||||

| yes | EVID | ||||||

| That’s what they were, they say... | |||||||

| 19 | tseb | ta | `al-el | `un-e | |||

| girl | PREP | say-NOM | CL-CL | ||||

| But supposedly they were girls. | |||||||

| 20 | le:k-il | pulul-ik | s-jol | ti | tseb | `un-e | |

| good-ATT | thickly_sprouted-PL | 3E-head | ART | girl | CL-CL | ||

| Beautiful thick hair on the girls. | |||||||

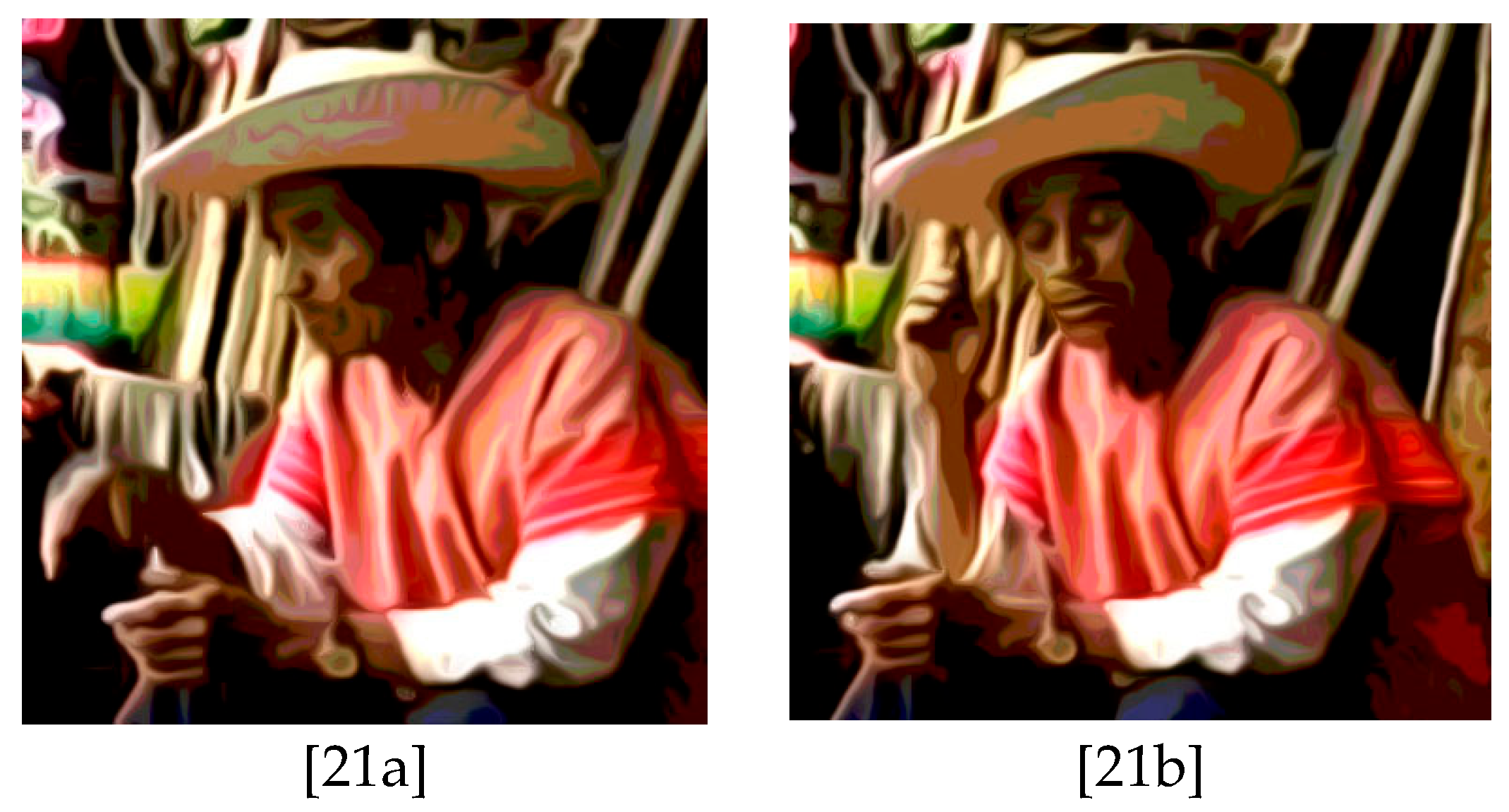

| Example 11 | [21a] | [21b] | ||||||

| 21 | k’alal | mu | j-k’an | mi | x-0-ut | la | `un-e, | |

| when | NEG | 1E-want | INT | ASP-3E-tell | EVID | CL-CL | ||

| When the guy supposedly told him, “I don’t want them”— | ||||||||

| 22 | Mu | j-k’an | xi | la | `un-e | |||

| NEG | 1E-want | say | EVID | CL-CL | ||||

| “I don’t want them,” he apparently said. | ||||||||

| [23a] | ||||||||

| 23 | k’alal | va`-ajtik | un, | |||||

| when | standing-PL | CL | ||||||

| While they were standing up on two feet, | ||||||||

| 23x | [23xb] | |||||||

| lek | `ono | la | tseb | yilel | x-0-cha`le, | |||

| good | indeed | EVID | girl | apparently | ASP-3E-act | |||

| They made themselves actually look like proper girls. | ||||||||

| 24 | bweno | |||||||

| Okay. | ||||||||

| Okay. | ||||||||

| 25 | k’alal | mu | la | x-0-k’ane | `un-e | |||

| when | NEG | EVID | ASP-3A-want-PASS | CL-CL | ||||

| When they were told they weren’t wanted. | ||||||||

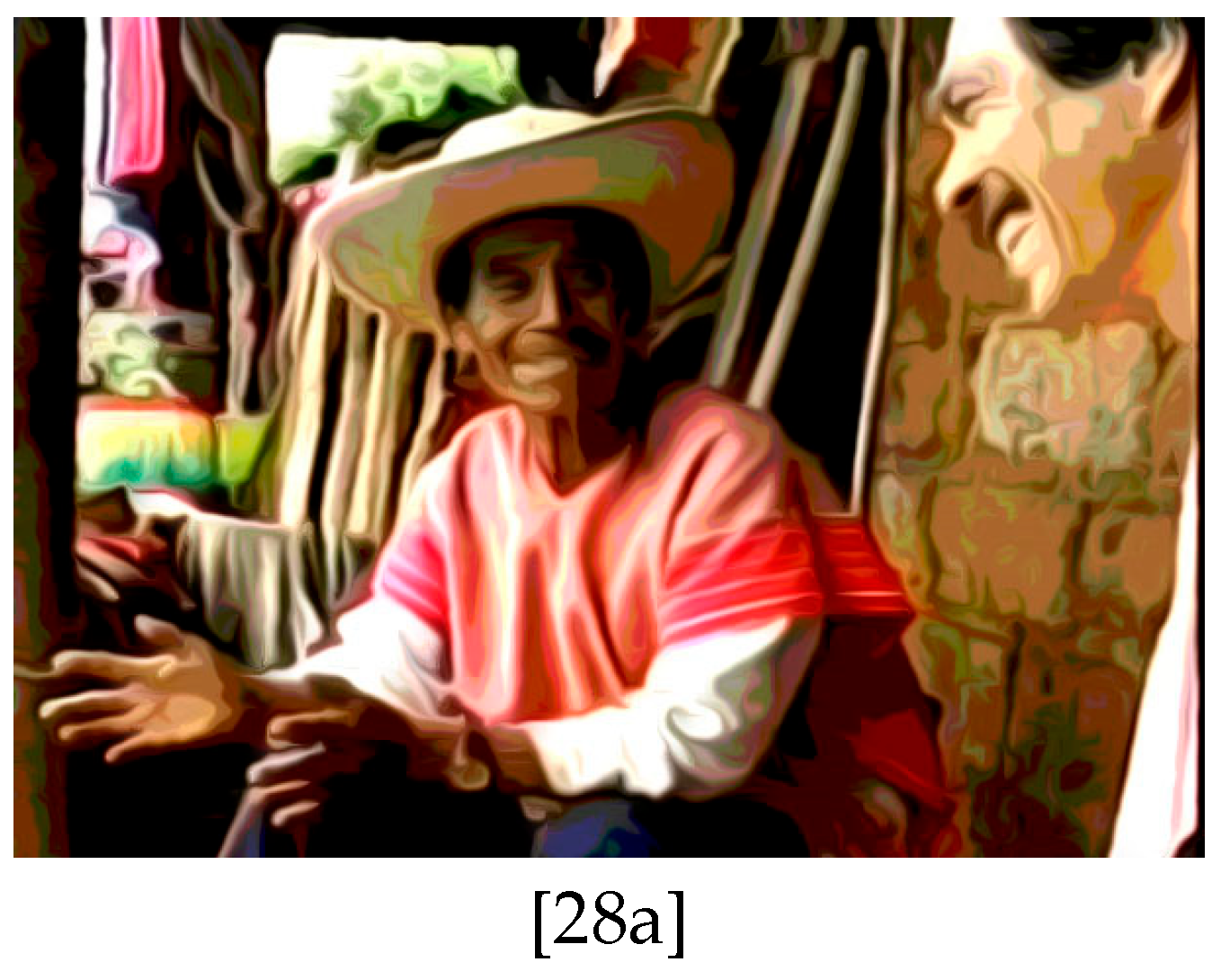

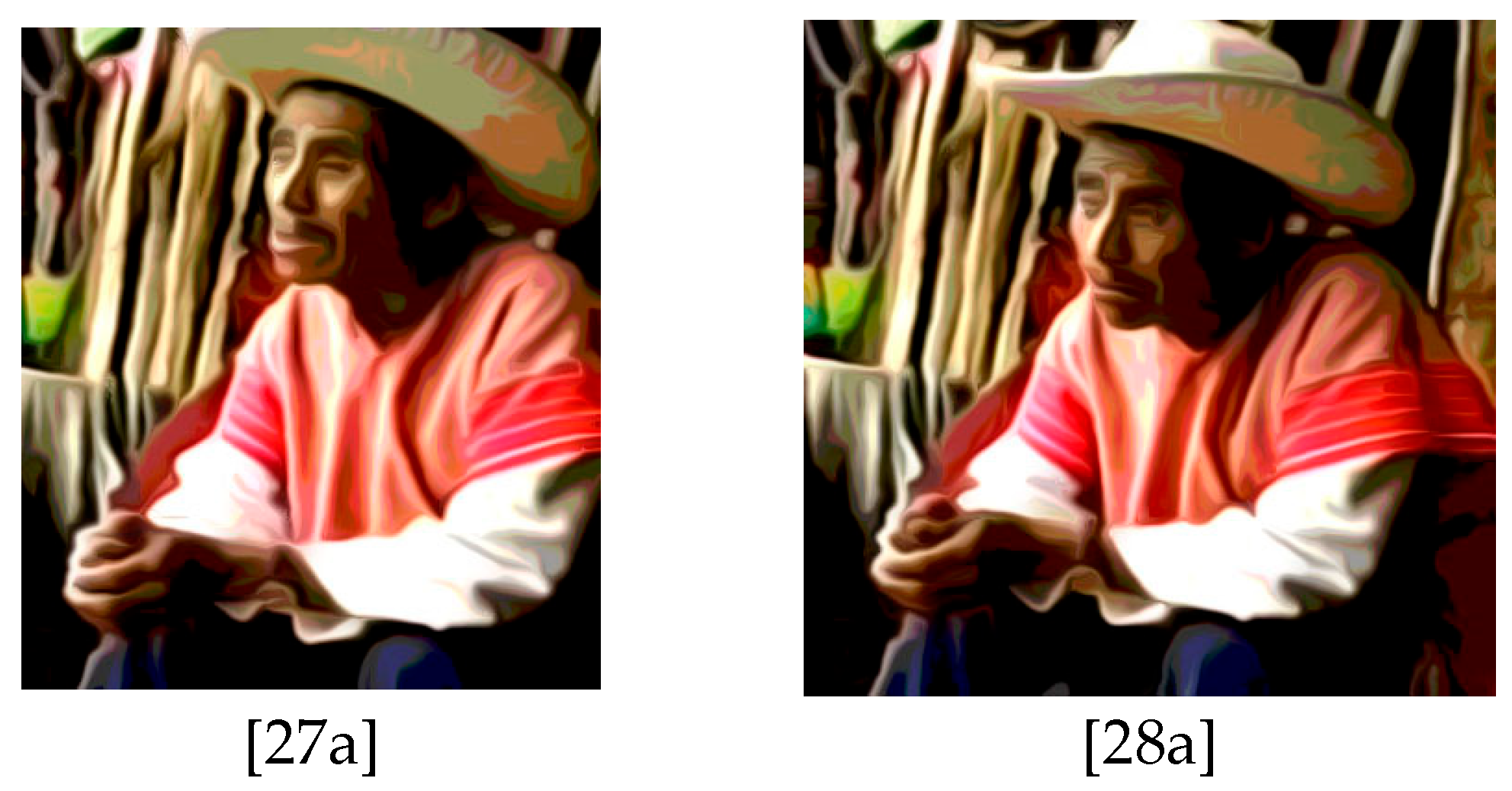

| Example 12 | [26a] | [26b] | [26c] | ||||

| 26 | bat | `u:n, | k’ataj-e, | ||||

| go | CL | transform-CL | |||||

| They left, they were transformed. | |||||||

| [27d] | |||||||

| 27 | xok’-la:j | xi | `ech’el | li | sapo-etik | `une | |

| squat-AV | thus | away | ART | toad-PL | CL | ||

| The toads hopped away squatting. | |||||||

| [28a] | |||||||

| 28 | pero | tseb | `un | ||||

| but | girl | CL | |||||

| But they were supposedly girls. | |||||||

“The affective verb CVC-lah18 occurs always in the sequence av + ša + directional verb. It implies the rapid motion of an object or animal towards or away from either the narrator or the protagonist”.

7. A Supernatural Encounter

| Example 13 | [3a] | ||||||||

| 3 | ja` | no`ox | k’al | x-lok’ | muk’ta | k’anal | xi, | ||

| ! | only | when | ASP+3A-exit | large | star | Said | |||

| Just when the big star comes out, he said. | |||||||||

| [4a] | [4b][4c] | ||||||||

| 4 | `oy | j-p’ej | mol | k’anal | x-lok’ | ta | sak | `osil-e | |

| EXIST | one-NCL | big | star | ASP+3A-exit | PREP | white | land-CL | ||

| There’s one big star that comes out just at dawn. | |||||||||

| Example 14 | [9a] | ||||||

| 9 | `ali | jch’ulme`tik-e | mu | xa | bu | x-ch’ay, | |

| ART | Moon-CL | NEG | already | where | ASP+3a-lose | ||

| The moon (“our holy mother”) will not have been lost yet. | |||||||

| [10a] | |||||||

| 10 | toyol | ch-kom | xi | ||||

| high | ICP+3A-remain | said | |||||

| It will still be high, he said. | |||||||

| Example 15 | 25 | ya`uk | s-ba`yubtas | y-a`-uk | s-tij | ta | s-pat | mu | x-0-anav |

| think-SUBJ | 3E-put_in_front | 3E-think-SUBJ | 3E-hit | PREP | 3E-back | NEG | ASP-3A-walk | ||

| He tried to make it go in front and to hit it on the back from behind, but it wouldn’t walk. | |||||||||

| 26 | kotol | ||||||||

| Standing(four legged) | |||||||||

| It just stood there. | |||||||||

| [27a] | |||||||||

| 27 | jo:k-sjo:k | ts-ni`, | |||||||

| snorting | PREP+3E-nose | ||||||||

| It kept snorting. | |||||||||

| [28a] | |||||||||

| 28 | s-k’el-o:j | la | li | ka`-e | |||||

| 3E-look-PERF | EVID | ART | horse-CL | ||||||

| The horse just appeared to be looking (at something). | |||||||||

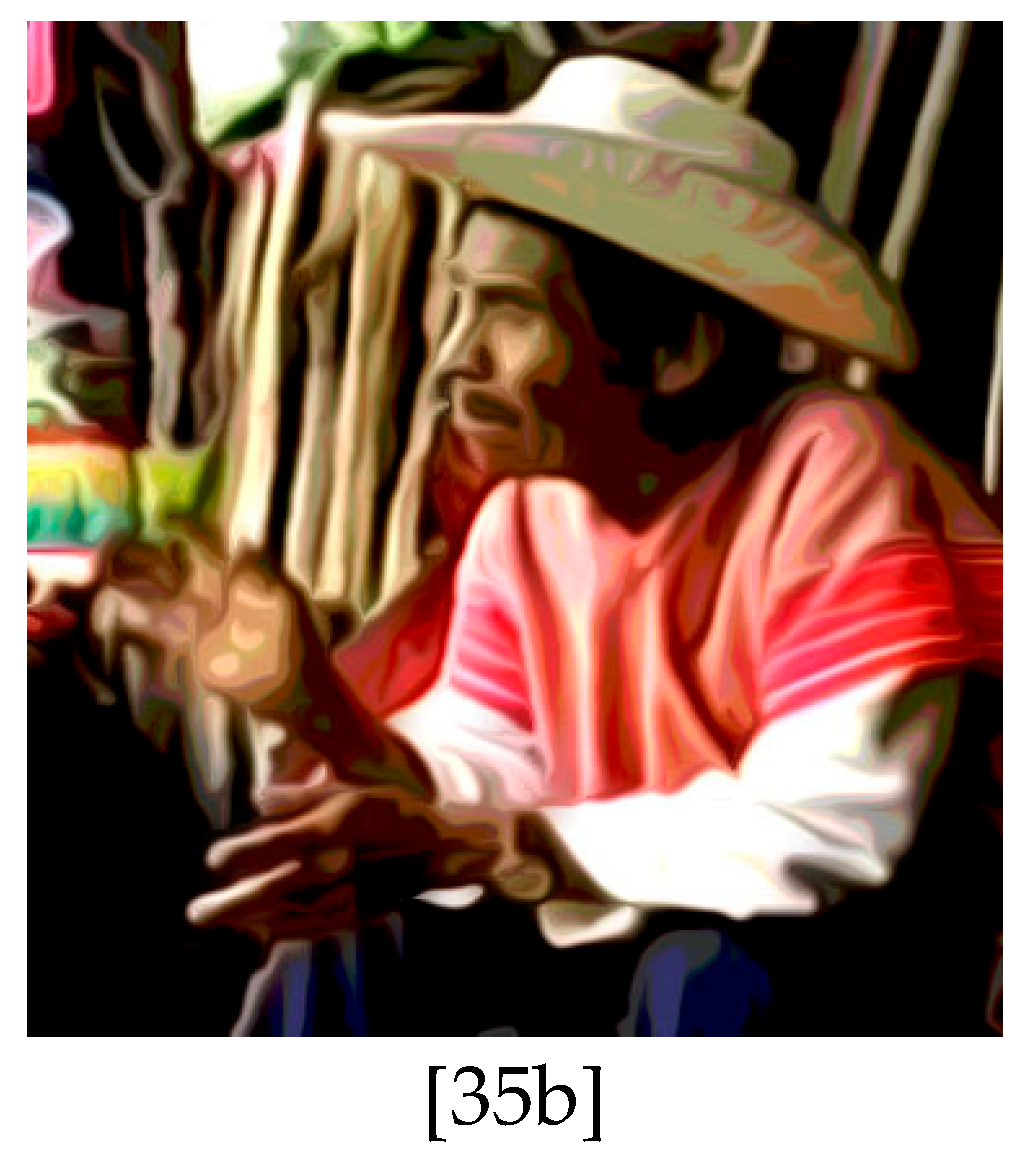

| Example 16 | [35b] | ||||

| 35 | sak-jam-a:n | xa | li | balamil-e | |

| white-opening | already | ART | earth-CL | ||

| The earth was dawning already. | |||||

| 36 | x-vinaj | xa | `un | ||

| ASP+3A-appear | already | CL | |||

| One could begin to see. | |||||

| Example 17 | 49 | `Eeee | |||||||

| EXCL | |||||||||

| “Eeek.” | |||||||||

| 50 | `oy | te | ch-il | ka:jal | ta | ka` | jun | jkaxlan | |

| EXIST | there | ICP+3E-see | mounted | PREP | horse | one | ladino | ||

| He could see there, mounted on a horse, a ladino man. | |||||||||

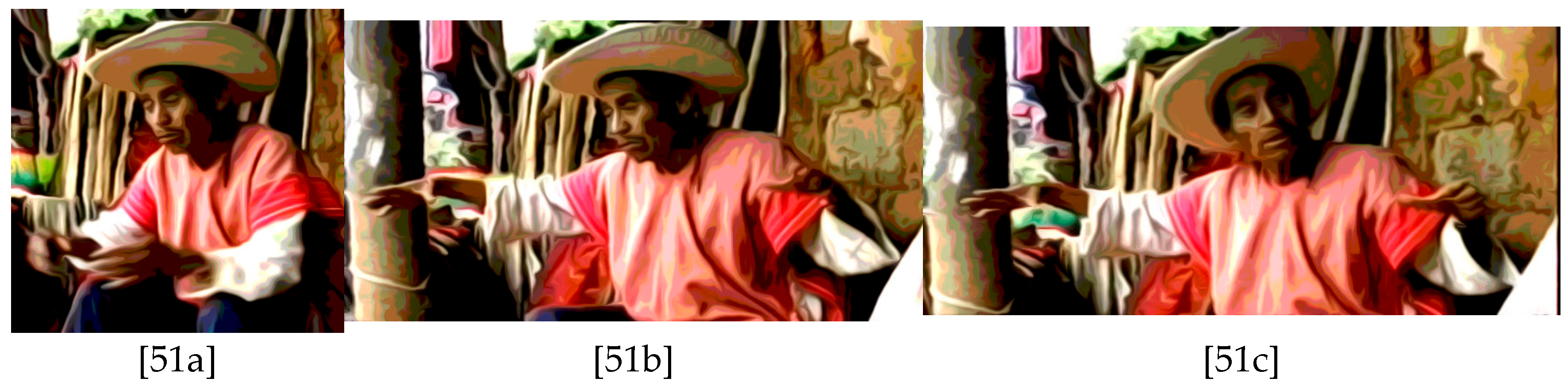

| Example 18 | [51a] | [51b] | [51c] | ||||||

| 51 | mo:l | y-u`n-la | x-pixol | xi | to | vi | ch’ut | beo`-tik-e, | |

| big | 3E-belong-CL | 3E-hat | thus | PSP | look | belly | creek-DIST-CL | ||

| With a bi:g hat like this, in the creek bed. | |||||||||

| 52 | lek | to`o:x | sob | tajmek | `un | ||||

| good | then | early | very | CL | |||||

| It was still very early in the morning. | |||||||||

| 53 | sombreron | la | `un | ||||||

| Sombreron | EVID | CL | |||||||

| It was evidently a bogeyman. | |||||||||

“intensifies the particular state of the root. It may stress the slowness or ponderousness of its motion, the ineffectiveness or repetition of an action, the loudness of a noise”.

| Example 19 | [54a] | [54b] | ||||||

| 54 | Bat | la | `un, | |||||

| go | EVID | CL | ||||||

| Then he took off. | ||||||||

| [55a] | ||||||||

| 55 | leplo:n | xi | ech’el | ta | ka` | `un | ||

| bouncing | thus | DIR (going away) | PREP | horse | CL | |||

| He trotted off on the horse. | ||||||||

| 56 | pu:ta | pero | l-i-xi` | `un | xi | |||

| whore | but | CP-1A-fear | CL | said | ||||

| “Damn! But I was afraid,” he said. | ||||||||

| Example 20 | [57a] | [57b] | ||

| 57 | Pero | marku:x, | ch-a-bat-e | |

| but | Marcos | ICP-2A-go-CL | ||

| “But Marcos. You’re done for.” | ||||

| 58 | ch-a-cham | `onox, | ||

| ICP-2A-die | always | |||

| “You’re going to die for sure.” | ||||

| Example 21 | |||

| 1. | P; | “You’re not going to grow old,” I told him. | |

| 2. | M; | “Is that certain?” | |

| 3. | P; | “Yes.” | |

| 4. | M; | “But how is that?” | |

| 5. | P; | “The bogeyman’ll come to take your luck,” I told him. |

8. Coexpressive Interaction: Thieves

| Example 22 | |||

| 1. | M: | Belongs to my little brothers. | |

| 2. | P: | Why do they ruin the pine trees? | |

| 3. | They chopped them down, left the pines split wide open. | ||

| 4. | Just left them, didn’t even take them. I stumbled (vuk’-laj) down there a few days ago. | ||

| 5. | M: | But where exactly? | |

| 6. | P: | Above my son Antonio’s land, inside your woodlands. | |

| 7. | M: | Ah, they’re the ones who steal pine needles.25 | |

| 8. | P: | Thieves? Idiots! | |

| 9. | Why should they chop baby trees? | ||

| 10. | “Don’t they care about letting pines grow?” I asked myself. | ||

| 11. | M: | No, because they’re thieves. | |

| [12a] | |||

| 12. | P: | Damn! They were baby pines just this big. | |

| 13. | M: | They bent down the tips of the pine trees and broke them off to carry them away. | |

| 14. | P: | Ee:y, damn! |

| Example 23 | [2a] | [2b] | |||||

| 2 | P; | ba:t | cha`- | p’ej | j-vompa | ||

| go | two- | NCL[round] | 1E-pump | ||||

| Two pumps were stolen. | |||||||

| 3 | M; | bat | `un | ||||

| go | CL | ||||||

| They were stolen?. | |||||||

| [ | [4A] | ||||||

| 4 | P; | ba:t | vakib | litro | j-likiro | ||

| go | six | liter | 1E-herbicide | ||||

| Six liters of herbicide were stolen. | |||||||

| 5 | ba:t | `ach’ | k’u`ul-etik | ||||

| go | new | clothing-PL | |||||

| y-u`un | li | lol-e | |||||

| 3E-POSS | ART | Lorenzo-CL | |||||

| Lorenzo’s new clothes were stolen. | |||||||

| [6a] | |||||||

| 6 | M; | kere: | |||||

| boy | |||||||

| Boy! | |||||||

| [ | [7a] | ||||||

| 7 | P; | x-chi`uk | j-tojbalal | i-bat | s-k’u`-tak | ||

| 3E-with | AGN-employee | CP-go | 3E-clothes-DPL | ||||

| And also the workmen’s clothing was stolen. | |||||||

| Example 24 | [8a] | |||||

| 8 | P; | yech | xa | x-moch’laj | yulel | |

| thus | already | ASP-shivering/huddled | DIR (arriving_here) | |||

| They got back here just empty-handed. | ||||||

| Example 25 | |||||||||

| 9 | P; | ch’abal | xa | cha`-p’ej | vompa | ||||

| none | already | two-NCL[round] | pump | ||||||

| And they were without their two pumps. | |||||||||

| [10a] | |||||||||

| 10 | M; | nompre | de | dyos | |||||

| name | of | God | |||||||

| In the name of God! | |||||||||

| [ | |||||||||

| 11 | P; | mu | xa | bu | y-ak’-be | komel | |||

| NEG | already | where | 3E-give-APP | DIR(staying) | |||||

| They never applied the herbicide - | |||||||||

| Example 26 | [13a] | |||||||

| 13 | P; | They still returned. | ||||||

| [ | ||||||||

| [14a] | ||||||||

| 14 | M; | They still returned | ||||||

| 15 | P; | I have bought a replacements for one of my pumps. | ||||||

| 16 | But they’re expensive! | |||||||

| [ | ||||||||

| [17a] | ||||||||

| 17 | M; | But they’re very expensive! | ||||||

| 18 | P; | Expensive, now. | ||||||

| [ | ||||||||

| 19 | M; | Expensive now. | ||||||

| [20a] | ||||||||

| 20 | P; | Impossible to buy them. | ||||||

| 21 | M; | Impossible to buy them. | ||||||

| Example 27 | [8a] | ||||||||

| 8 | P; | animal | vokol | li | puta | j`elek’-e | |||

| extremely | difficult | ART | whore | robber-CL | |||||

| It is really hard (to deal with) damned thieves! | |||||||||

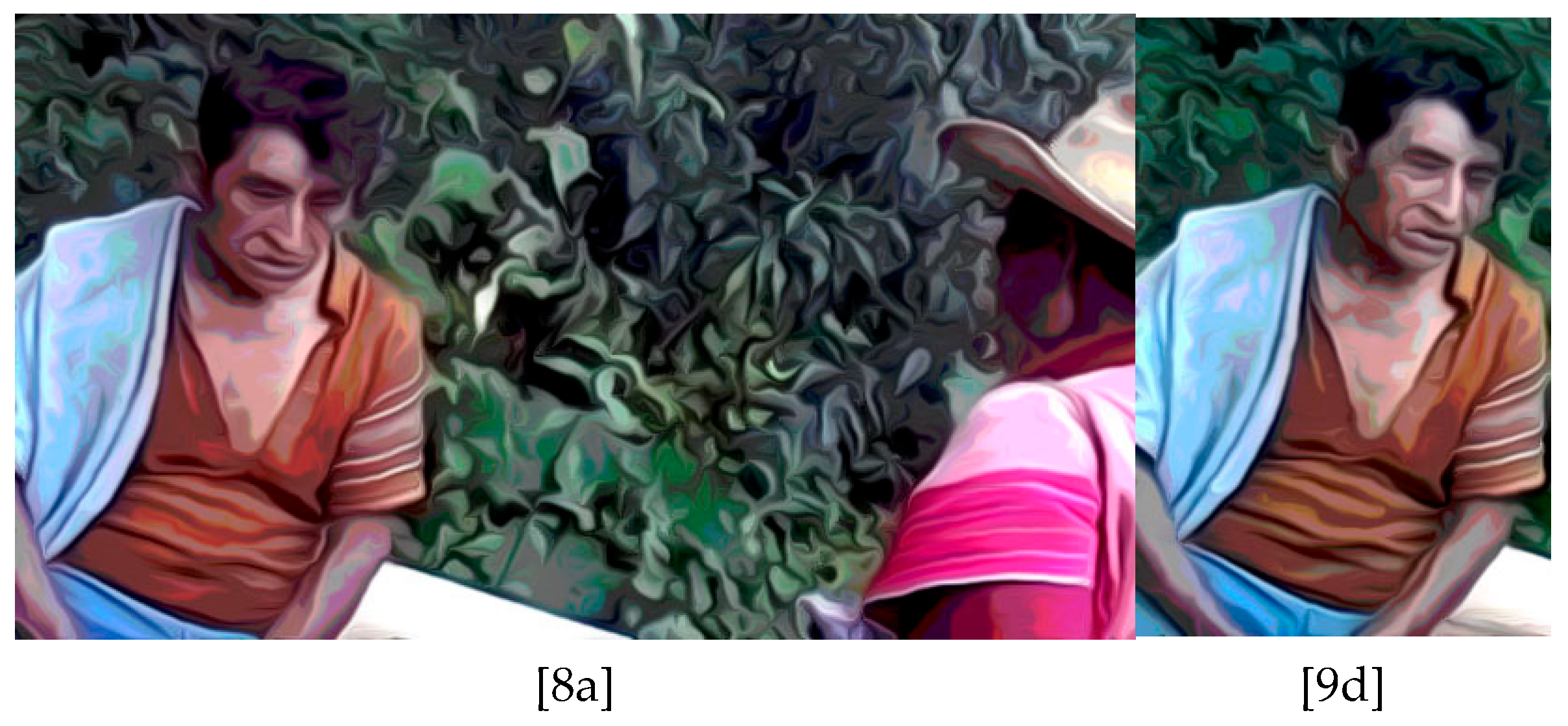

| [ | [9d] | ||||||||

| 9 | M; | animal | chopol | s-jol-ik | |||||

| extremely | bad | 3E-head-PL | |||||||

| They have very bad heads. | |||||||||

| 10 | M; | [10a] | |||||||

| loj | ryox | ||||||||

| 3E+see+PERF | God | ||||||||

| As God is my witness! | |||||||||

9. Summary and Farewell

“Elements which are found together in the same utterance (say, in the various lines of a poem) in certain sequentially-definable positions, are “equivalent” in the sense of being metaphorically compared and contrasted.”

- This essay began not with Don Pedro himself but with his elder daughter. In Example 1, she recounted a visit to her house and a complaint addressed to her magistrate husband by a beaten woman about the punishments she thought her own abusive husband deserved. Jakobson’s “poetic function” was directly relevant to the generic specificities of this wife’s lament, phrased in the chanted parallel lines of Tsotsil “ritual speech” with all of its generic specificities (rhythm and cadence, conventionalized doublets and triplets, often involving archaic or loan lexicons, and precise morphological parallelism) to highlight the metaphorical domains of importance—here, the conceptual link between speech and both abuse and punishment. Such a ritual speech genre is the Zinacantec default for shamanic and religious prayer, for ritual counsel and advice, as well as for denunciation, lament, and witchcraft.

- Zinacantec society also embodies metaphors of rank: in spoken Tsotsil, through greetings, leave takings, and address formulas, but ordinarily accompanied by direct bodily manifestations, as for example in shaking hands vs. “bowing” and “releasing” to initiate or end interaction and conversation, rank order in walking or seating positions, and also turn-taking order or serving position for ritual prestations (see Figure 3).

- Other conventionalized gestures are integral parts of ordinary face-to-face talk. (Consider the “nod” in Figure 5b, or the “shrug” in Figure 7[g1].) As in virtually all speech traditions around the world, iconic gestures complement the meanings of spoken Tsotsil words, offering referential specificity often absent in speech alone (for example, the “small trees” in Figure 38).

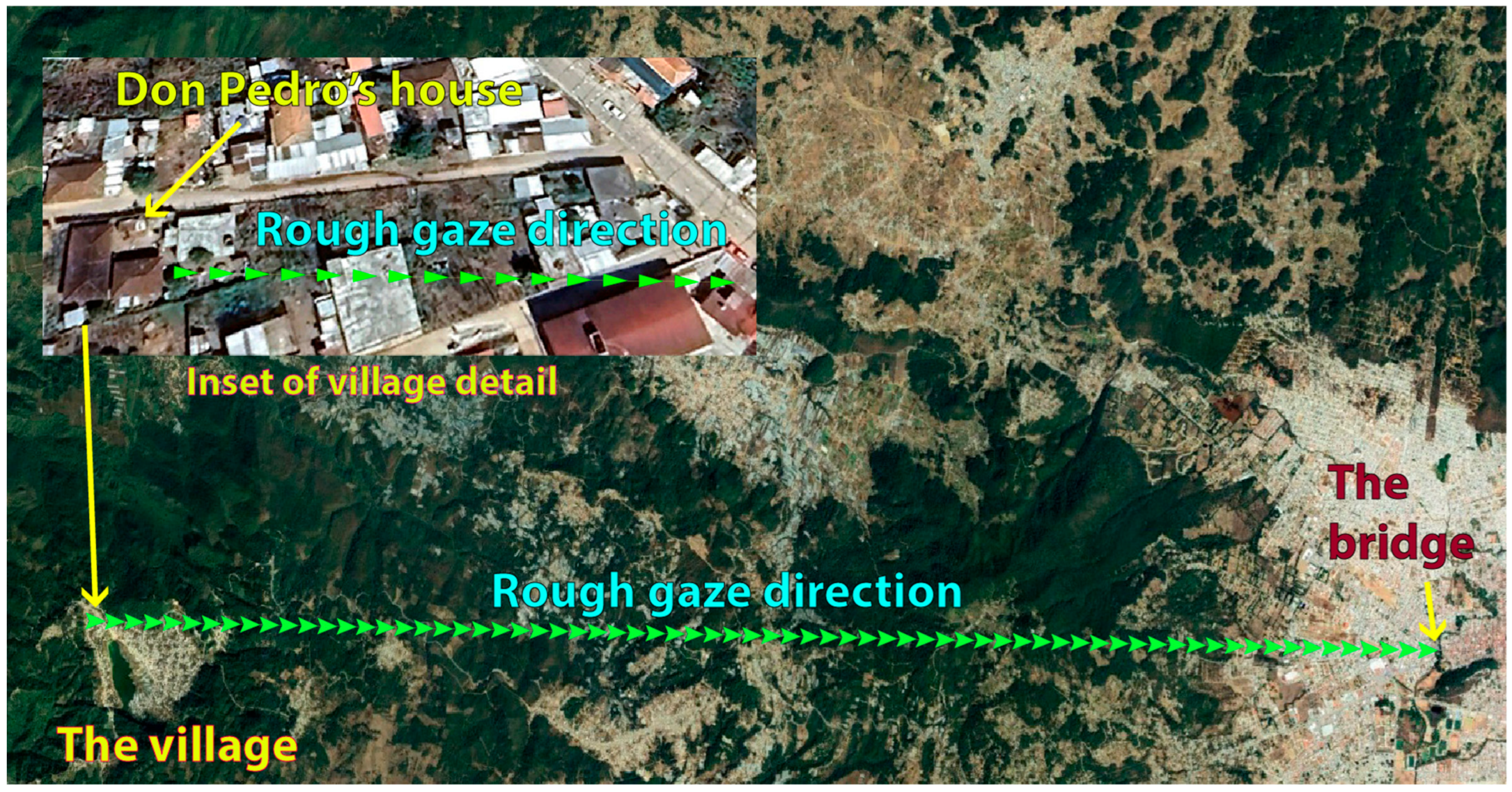

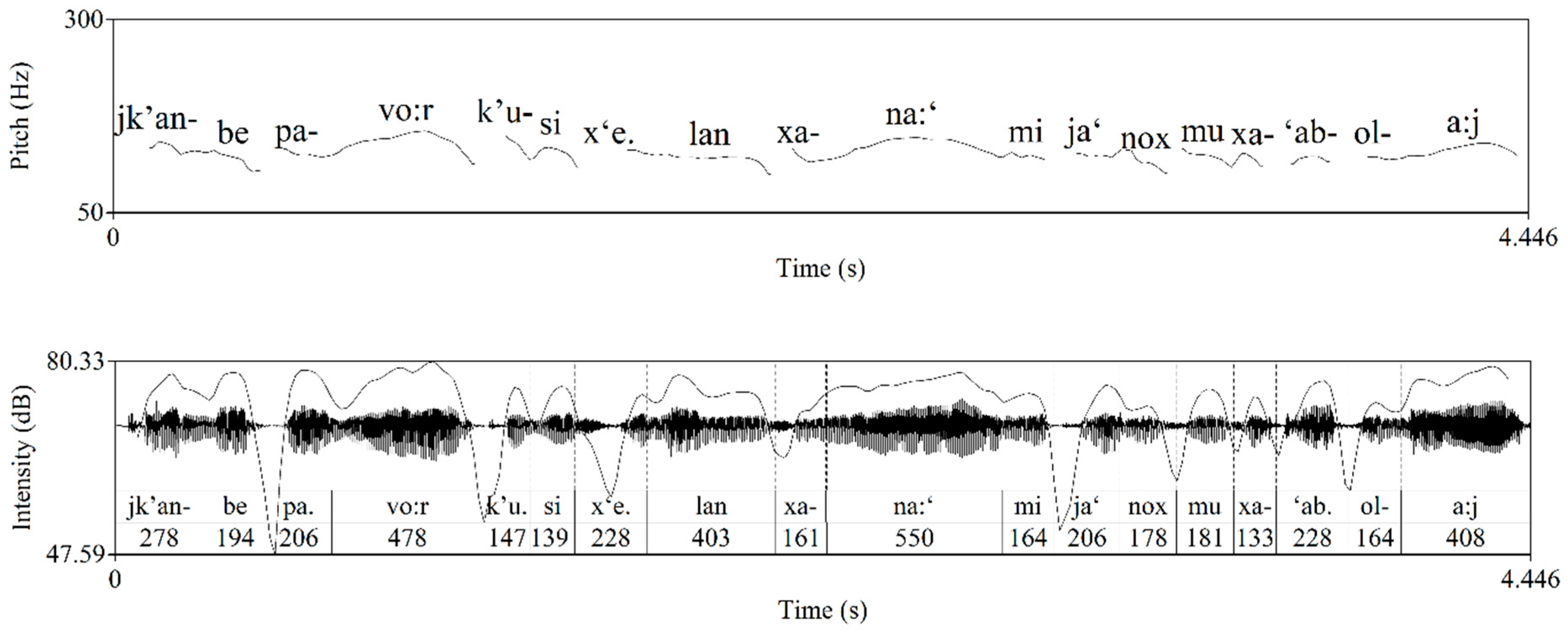

- There are multiple indexical devices available for locating objects, oneself, and one’s protagonists in physical, interactive, and virtual space(s). Notably, Don Pedro makes systematic use of gaze, pointing (with various body parts and, sometimes, tools), and facial orientation (as well as with myriad spoken and gestured locational devices). These spaces may be given by one’s actual physical (and biographic) position in the real world, at different levels of granularity; they may also be invoked by interactions, both given by the conversational circumstances or created discursively. Of these “spaces,” Tsotsil presumes directional precision for known real places: east is east, and west is west (see Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6). Such orientation is also presumed in a depicted interactional scene (Example 4, Figure 10 and Figure 12), and the conceptual complexity of mutually overlaid or transposed spaces can also involve recurrent, recursive, and even fractal orientation. (Consider the interactive space in my conversation with Don Pedro—for example Figure 15[6A], or the configuration of the Chamula’s “bride” selection, Example 7—and how interactive space can also overlay or structure an imagined or conjured space, e.g., “over the shoulder” in Example 13.)

- Tsotsil interlocutors use their gaze and their faces as indexical devices linked to “pointing,” i.e., to indicate (by looking at or appearing to look at) locations and other referents, again in a myriad of different “spaces” ranging from the immediate speech situation and the surrounding wider geographical area at different levels of resolution, to imagined or conjured spaces implied by other conversations, mimed or retold. However, gaze in so-called “face-to-face” interaction has conceptually different communicative uses as well. Depending on cultural practices from place to place (see Rossano et al., 2009), gaze can be a central index of attention, mutual or disjoint, and also an index of different aspects of turn-taking (see Kendon, 1967; Goodwin, 1981 for early studies). There are also times in Zinacantán when politeness decrees certain gaze avoidance, but Don Pedro in most informal talk often uses his gaze to signal, to summon, or to monitor different sorts of attention. There are also what I have called “nowhere” spaces or internally created mental ones (Figure 17[12a-b]), towards which apparent (sometimes vacant) gaze may seemingly be directed. Similarly, both gaze and facial expression—a frown of disapproval or raised eyebrows in surprise (see Figure 40)—can offer an interlocutor’s expressive commentary or “back channel” via the face, and such expressive devices can function as well as, if not better than, spoken assessments (Goodwin, 1986; Goodwin & Goodwin 1987).

- The latter sections of this exploration of Don Pedro’s verbal mastery and coexpressivity return to his speech, relying less on multimodality (gesture, gaze, and proxemics) than on his words (or sounds) themselves. Jakobson apparently had verbally encoded “assessments” directly in mind when citing as primary examples of the “EMOTIVE or ‘expressive’ function” what Conan Doyle writes as “Tut! Tut,” which “consists of two suction clicks” (1960, p. 354). He continues, “[t]he emotive function, laid bare in the interjections, flavors to some extent all our utterances, on their phonic, grammatical, and lexical level” (p. 354). In addition to non-spoken emotive elements of the sort previously mentioned, Tsotsil interjections include, with a different valence, similar suction clicks, as well as full, etymologically transparent, lexical words like kere! (“boy,” Figure 40[4a]) or loanword imprecations as in Example 25. Spoken expression of epistemic and emotional concordance and discordance are also frequent in Tsotsil speech, for example through the interactional mechanism of partial repetition of an interlocutor’s exact words (see Example 26).

- Like Conan Doyle’s orthographic rendering of tut tut, Tsotsil onomatopoeic roots are conventionalized expressive elements in their own right. Although they may serve as the basis for verb stems, unlike most Tsotsil roots, they can also be uttered bare or reduplicated, often with unusual voice qualities; they are thus both imitative (iconic) and expressive all on their own (the knock on the door and the dog’s answering bark in Example 3; Markux’s terrified horse whinnying in Example 15).

- I have suggested that particular derivational morphology in Tsotsil produces direct coexpressivity. That is, words so derived combine both the core denotational semantic packet of the root involved and a coexpressive, not necessarily fully specified or predetermined, additional dramatic or humorous flavor or effect. Don Pedro’s examples above include Kaufman’s “affect” or “affective” verbs and a few compound “color” words. The relevant semantic core mostly involves so-called positional roots, which denote sorts of entities (often bodies or body parts) and their shapes, positions, and configurations. Choice of such a root is central to mastery of Tsotsil, but the specificity of each configuration also makes each positional lexeme ripe for parody and ridicule. The candidate brides, who were supposedly standing bipedally and upright when they looked like human women, were revealed to be toads when they reassumed their natural squatting positions—described with the root xok’ (“squatting”)—and hopped off (Example 12). The “affective” verbal suffix -laj captured their abrupt, comical, and abject departure when rejected. Don Pedro mocks himself when he characterizes his unstable footing walking in the steep woodlands in Example 22, combining the same motion suffix with the transitive root vuk’ (“kick something down”). Compound color words, as in Figure 30, associate specific hues with positional and other verbal roots to evoke shapes, configurations, and scenarios to which the colors may appropriately be applied, to suggest entire visual scenarios.

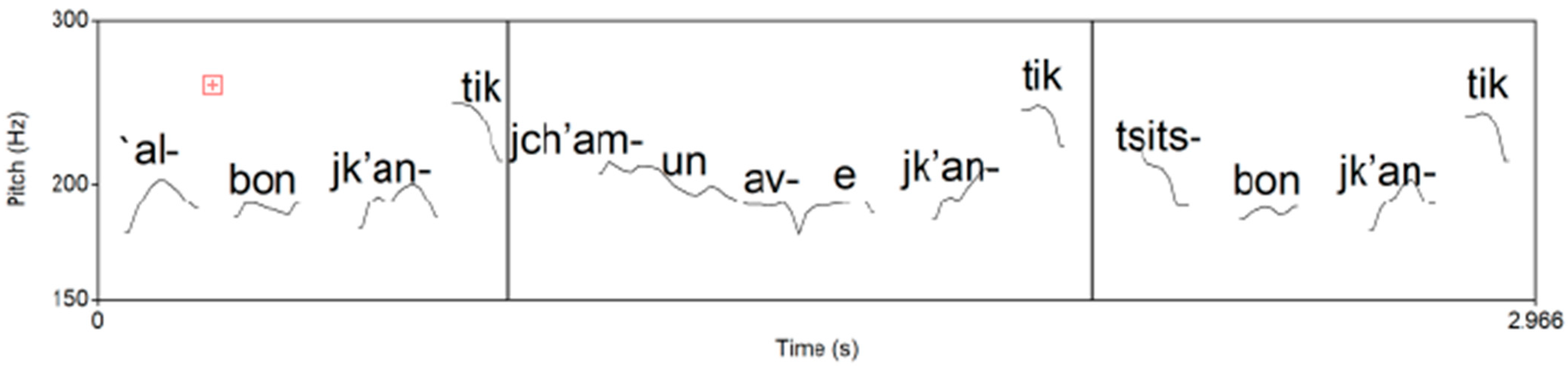

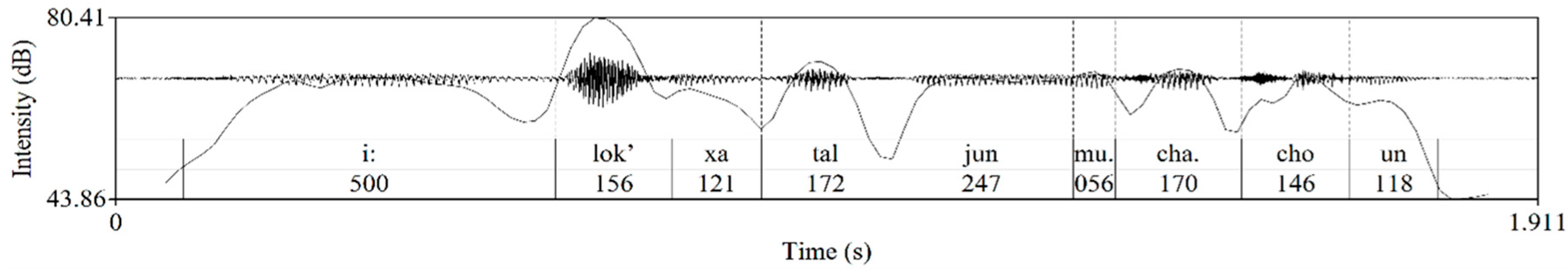

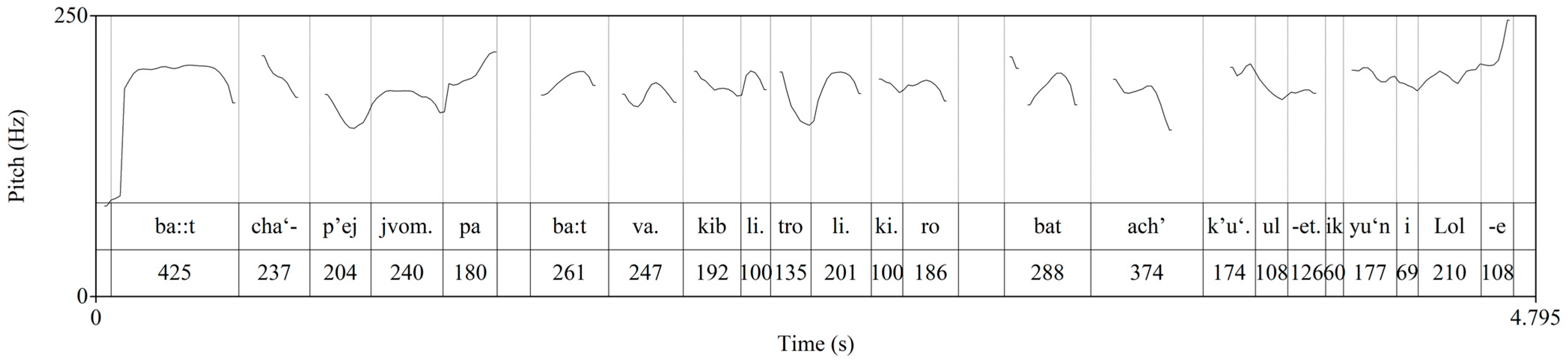

- As quoted above, Jakobson argues that “the emotive function … flavors … all our utterances.” Phonological features of my compadre’s Tsotsil illustrate such flavoring. There are conventionalized melodic cadences not only for ritual speech, but also for formal requests, pleading (see Figure 13), and chiding (Figure 37). Speech rate also slows noticeably when one is a supplicant, whereas when one is angry (or being depicted as angry), speech is rapid and clipped, and often displays a creaky timbre (Figure 14). Finally, Don Pedro27 makes liberal use of elongated vowels for a variety of purposes including hesitations (Figure 11), lists (Figure 13), and onomatopoetic and positional iconic emphasis (Figure 23, Figure 30 and Figure 32). He elongates both evocative root syllables and “affective” verbal desinences that “have dash.”

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | I write “traditional” here because, although this genre of stringed instrument music—a mainstay of all religious ritual in the community—has existed for at least 300 years, it was derived in both its instrumentation and form from late-16th-century Spanish music introduced by Colonial friars; see the article by the Irish (ethno)musicologist Frank Harrison and his English musicologist wife Joan Rimmer, a specialist in early European musical instruments (Harrison & Harrison, 1968). |

| 2 | Tsotsil audio and video recordings were annotated for current purposes using ELAN software (ELAN, 2024). I use a slightly modified version of what is now a standard (and largely self-explanatory) Spanish-based practical orthography to write Tsotsil, using single Spanish letters to represent the most orthographically similar Tsotsil phonemes, digraphs (ts, ch) for similar affricates, and an apostrophe [‘] for ejective (glottalized) consonants. I digress from the practical orthography only by using an inverted apostrophe [`] for a glottal stop, to disambiguate such a consonant where necessary from a glottalizing apostrophe. Text examples are maximally transcribed line by line with Tsotsil words (shown in bold and split roughly into morphemes) on the first line, and corresponding morpheme-by-morpheme glosses in English (shown in plain non-italic type) on the second line, followed by an English free gloss (in italics) on the third. When appropriate, individual points in transcripts are marked above their lines (enclosed in square brackets) to crossreference corresponding illustrative video frames in accompanying figures. Abbreviations used in the morpheme-by-morpheme glosses include: 0, a null, unpronounced, or hypothetical “zero” morpheme; 1,2,3 first, second, and third person; A absolutive clitic; AGN agentive prefix; APP applicative suffix; ART article; APP applicative suffix; ASP neutral aspect; ATT attributive adjective; AUX auxiliar verb; AV affective verbal suffix; CL clitic; CONJ conjunction; CP completive aspect; DIR directional particle; DPL distributive plural; E ergative proclitic; EXIST existential nominal; EVID evidential clitic; ICP incompletive aspect; IMP imperative; INT interrogative particle; NEG negative; NCL numeral classifier; POSS possessive nominal; NOM—nominalizing suffix; PASS passive suffix; PERF perfective aspect; PL plural; PREP preposition; PRED predicative suffix; Q interrogative particle; SUBJ subjunctive or irrealis suffix; ! emphatic or topicalizing nominal. As common in conversational transcripts, overlapping speech by interlocutors are marked by an open sqaure bracket ([) where such overlap begins. |

| 3 | Silverstein (1981) treats in considerable detail a six-line fragment of a Tsotsil verse-prayer from Zinacantán (his example 4) displaying multiple layers of internal “poetic” structure that signal figures of metaphorical equivalence. |

| 4 | The Praat program analyzes digitally recorded audio to calculate acoustic properties of the signals. In this figure, to emphasize the pitch curve, I used a narrow pitch scale from only 150 to 300 Hz, compatible with the speaker’s voice range. An orthographic rendering of each Tsotsil syllable is written above the relevant segment of the pitch curve. |

| 5 | I am indebted to Doris Payne for reminding me of this recent coinage by Haspelmath and his colleagues, apparently first introduced in Haspelmath’s sense in (Hartmann et al., 2014), and elaborated as a more generalized typological (and terminological) proposal in Haspelmath’s 2023 paper (and cf. Haspelmath, 2019). |

| 6 | As Austin German reminds me, coexpressivity is not exclusive to “master” speakers, nor to highly valued speech genres, although it may reach metapragmatic consciousness most markedly in such contexts. It is, indeed, a property of all speech, even that of inexpert or clumsy speakers, as is apparent, for example even with some dispute settlers who may be selected in modern Zinacantán more for what lines their pockets than their golden tongues (see Haviland, 1990, an essay which borrows from the same metonym as this one). |

| 7 | Chamula is the name of a neighboring Tsotsil-speaking community (or municipio) with which Zinacantecs have a longstanding and somewhat competitive relationship. |

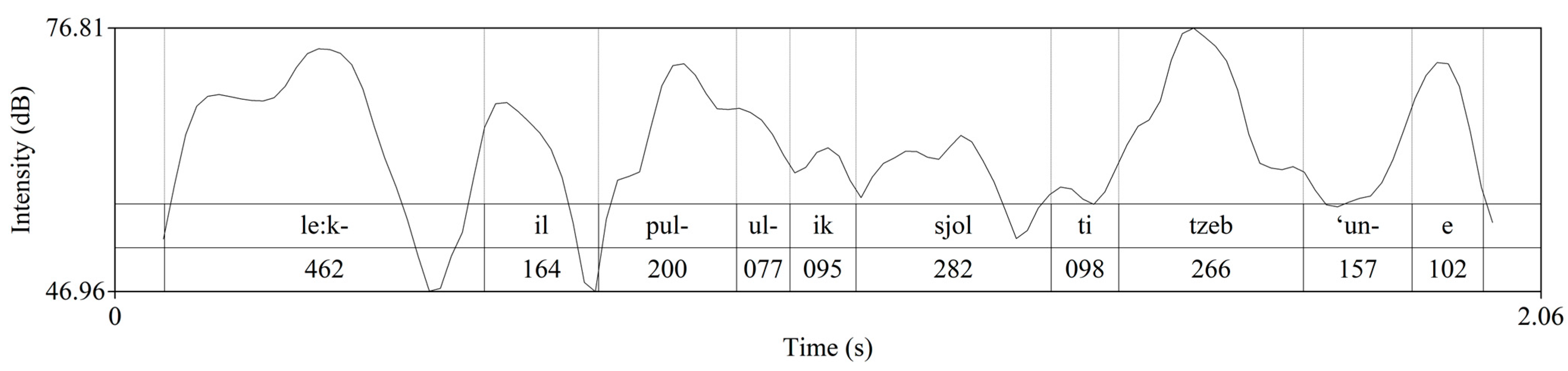

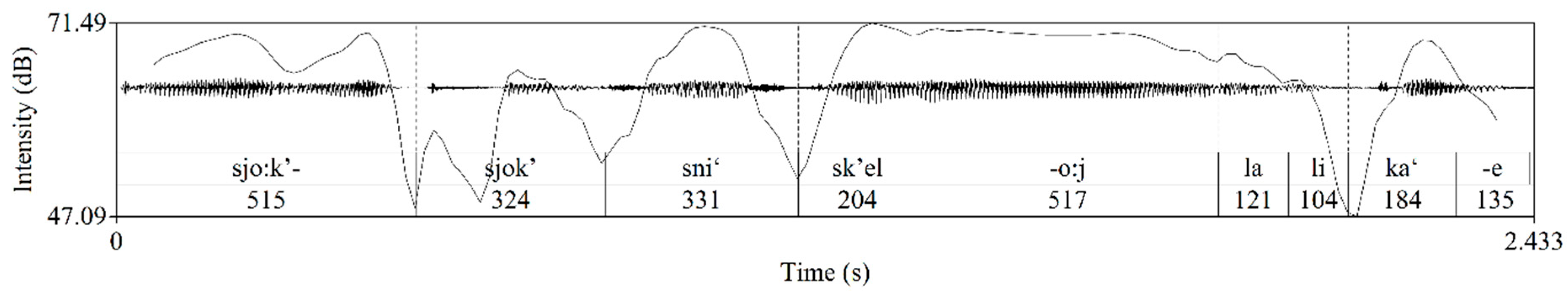

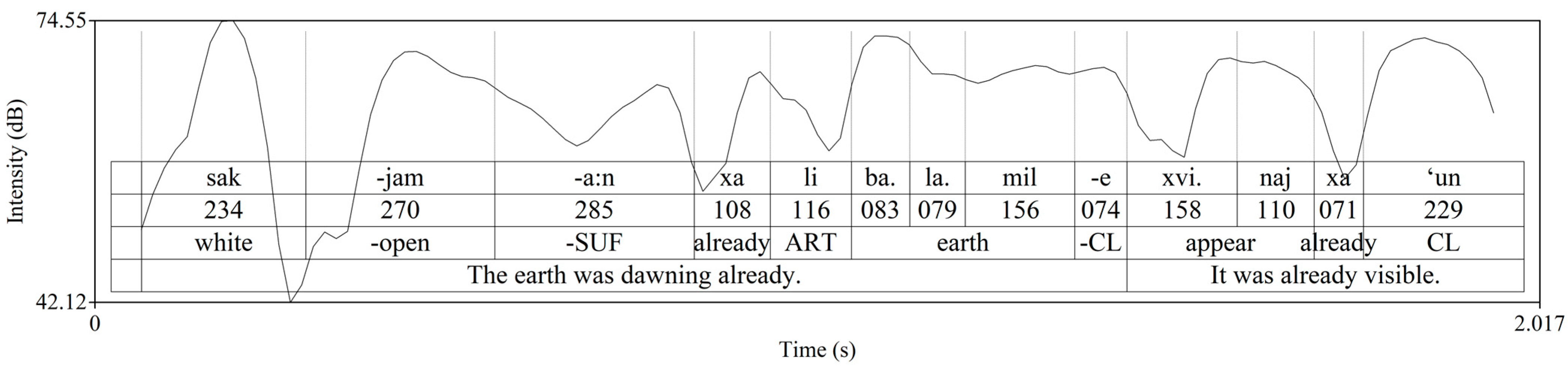

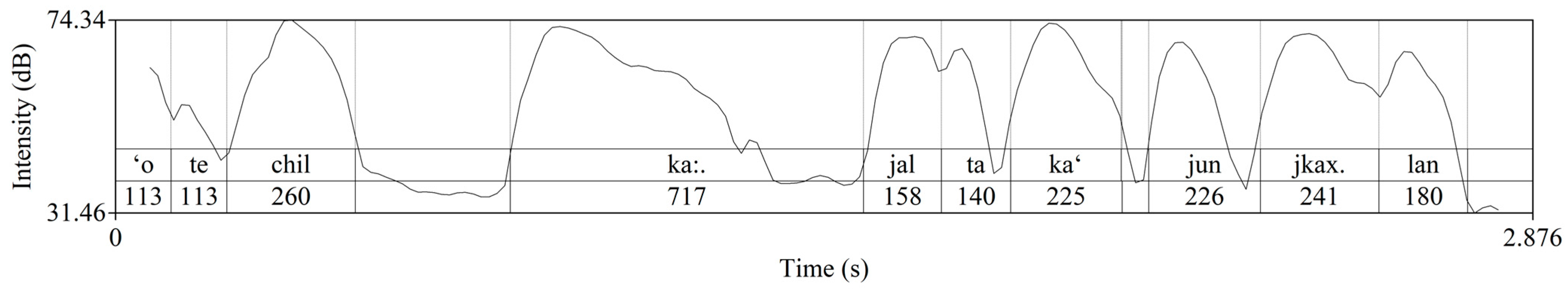

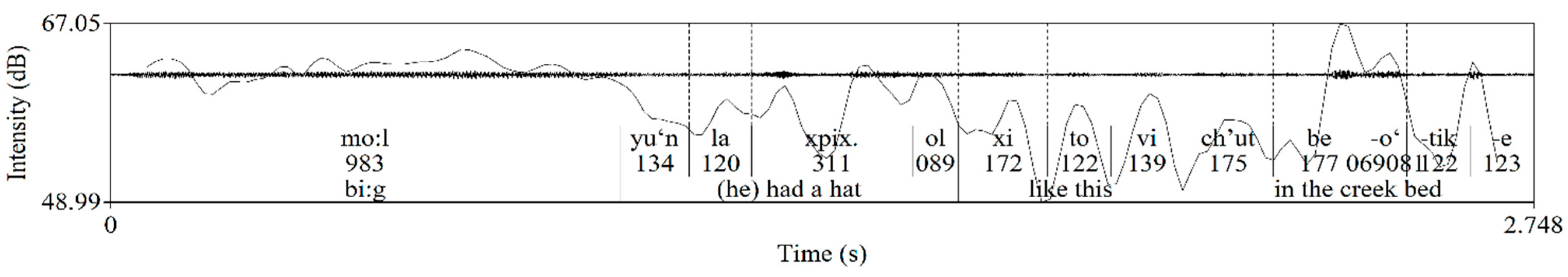

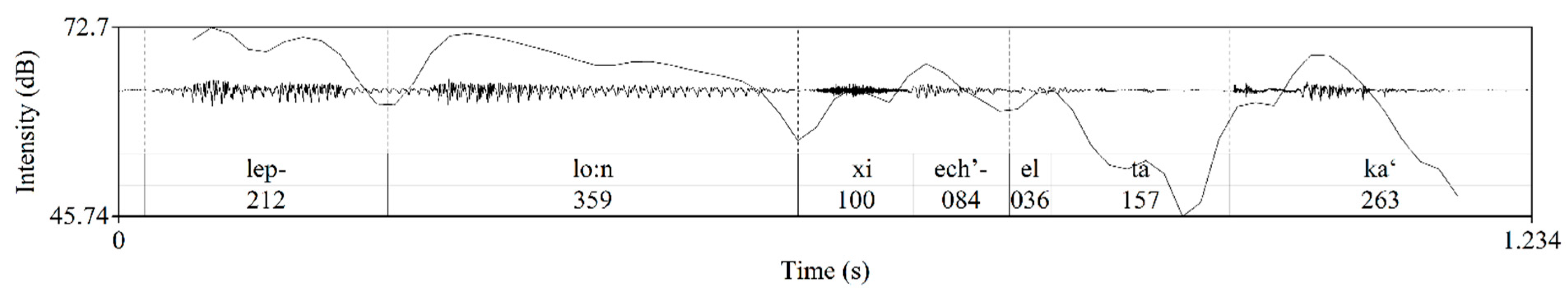

| 8 | In this and following Praat graphics, pitch curves are shown generally aligned vertically with orthographic rendering of syllables. Intensity (volume) is sometimes roughly graphed, usually as individual lines over the speech wave. The left to right axis represents time, so that syllable duration can be read from the annotated length (in milliseconds) corresponding to each syllable, as well as judged visually from the intensity line. Lengthened vowels are usually also indicated orthographically with a following colon (:) in the case of notably long vowels. In Praat syllable-length diagrams, a period (.) orthographically links syllables that are part of longer orthographic words, whereas dashes (-) mark morpheme boundaries of various sorts. |

| 9 | |

| 10 | It was precisely this phonotactic canon that allowed Laughlin to use a mechanical method, introduced by Norman McQuown (1952) and later employed rigorously by Kaufman and his students as well as many others (e.g., Collier, 1963; Berlin, 1968/2017), of generating all phonologically possible CVC roots and testing them exhaustively (and exhaustingly) one by one against possible morphological guises to discover (putative) “real” words. See Kaufman (2003) and Laughlin (1975) for more details. |

| 11 | Grouping together various formally defined subtypes of each main verbal category, the totals from Laughlin (1975) are 99 “intransitive” roots (defined by the fact that forms identical to the bare roots directly function as intransitive verb stems), 340 “transitive” roots, 182 “onomatopoetic” roots (with distinctive stem forms), and 761 roots categorized as “positional.” (There are also several much smaller root categories, including another 131 roots, for which Laughlin had insufficient attested stem possibilities to assign them confidently.) For details on the formal categorization of Tsotsil roots and stems, see Haviland (1992/1994). |

| 12 | Such notions Ameka and Levinson (2007) characterize as a typical subclass of “locative predicates,” because, in many languages, they characteristically provide sometimes obligatory verbs in locative sentences. Because of their exceptionally wide semantic range in Mayan languages, Steven Levinson once dubbed them “dispositionals,” a term adopted in a comparative study of Tseltal and Yucatec by Bohnemeyer and Brown (2007). |

| 13 | Kaufman (2003, p. 5) includes the following brief autobiographical note about his introduction to Mayan languages:

His 1963 dissertation lists a formal stem class for Tseltal, which he labels “affect verb,” whose members, unlike other stem classes, are always derived (p. 41) and which accept only limited verbal inflection (p. 169). He enumerates eight highly productive desinences which produce individual “affective verbs” from a range of different root types, with brief schematic characterizations of what such stems mean (pp. 88–92), although not explaining their supposed “affective” quality. |

| 14 | Aside from Ringe (1981), and a foundational paper on Tseltal (Maffi 1990), by far the most substantial treatment of the form and use of “affect verbs” (renamed “expressive predicates”) is Pérez González (2012) on Tseltal, Tsotsil’s closest relative, which expands on Kaufman’s original list of stem forms, exemplified in detail from various textual and audio recorded sources. Pérez González includes a partial dictionary of 475 “affective” or “expressive” stems from the Tseltal of Tenango. Note that Laughlin (1975)—who used the exhaustive CVC root method to elicit possible forms—attests more than 4000 “affective” verb stems for Zinacantec Tsotsil. See also (Zender, 2010). |

| 15 | Pérez González (2012, p. 58) makes a similar point about cognate forms in Tseltal: “Los expresivos además de evocar una escena de viveza en el discurso, pueden ser meramente descriptivos en determinados contextos, por lo que van y vienen de lo expresivo a lo llano, aunque la mayoría de las veces muestran connotaciones subyacentes al contexto pragmático en el que tienen presencia.” (Expressive [verbs], in addition to evoking lively scenes in discourse, can also be simply descriptive in certain contexts, so that they move between expressive and plain uses, although mostly they show connotations that underlie the pragmatic context in which they occur. [JBH translation].) |

| 16 | In the Spanish version of his dictionary (2008, p. 97), Laughin modified the Latin name to Bufo marinus. I am indebted to Austin German for asking about the apparent importance that Don Pedro seemingly assigns to recalling ther exact name for the toad here. |

| 17 | The hypothetical or underlying Tsotsil vowel A is realized sometimes as o and sometimes as a according to morphosyntactic conditions not otherwise relevant here. |

| 18 | |

| 19 | I am indebted to Olivier LeGuen (personal communication, 12 March 2025) for a parallel example from Yucatec Maya conversational usage where a speaker will “use a positional root that is not really suited for a human body or position to talk about a human; thus the discrepancy makes the situation grotesque and absurd hence funny. e.g., jenekbal which is for a heavy bag of grain lying on the floor, used to talk about a very fat man on a motorbike, as if he had no legs or lower body, just his enormous belly.” |

| 20 | |

| 21 | Laughlin’s (1975) dictionary of Zinacantec Tsotsil lists more than 1100 such compound words. A very few initial roots that are not “color” words also occur in such compounds, including some that denote temperatures like sik (“cold”) and k’ak’ (“hot”), although the total number of such compounds is tiny compared to those denoting colors. |

| 22 | He uses the Tsotsil word j-kaxlan, which combines an agentive prefix j- with a Tsotsilized version of the Spanish loanword castellano, thus, “Spanish person,” commonly translated into Mexican Spanish as ladino. |

| 23 | Laughlin (1975, p. 313) says of this creature: “It is believed that dwarf ladinos with enormous hats travel about at night frightening people. They are of two kinds: one is the ghost of unbaptized babies, the other, a thunder and lightning transformation of the earth lord. It is said that if, when you meet a big hat, you offer him a hatful of cigarettes, he will fill your hat with money. During the dry season big hats are believed to travel on deer to Guatemala to buy their stock of rockets for the forthcoming rainy season.” See also La Chica (2020) for other versions of this Chiapas bogeyman. |

| 24 | For a more extensive treatment of this full conversation, oriented towards the use of mutual epistemic assessment, see (Haviland, 2002/2004a). |

| 25 | In Zinacantán, pine needles and young pine boughs are required for decorating altars and other ritual purposes. |

| 26 | As with many of the affective verbs—and, indeed, other “possible” words that he and his Zinacantec collaborators discovered by combining Tsotsil roots with various derivational morphemes—Laughlin often pressed his Tsotsil colleagues to imagine scenarios where such words might be possible, without necessarily trying to explore their full range of possible uses. On the other hand, Juan Luciano Pérez Hernández, a young Zinacantec linguist, recently volunteered that for him the verb Don Pedro used means exactly the same thing as another much more common affective verb kiklajet—derived from a positional root kik (“leaning against (something)”)—which Laughlin (1975, p. 174) glosses as “staggering (drunk), toddling.” However, the situation in Don Pedro’s story clearly suggests a rather different image from that of a staggering drunk. As an unpossessed noun, moch’ also means “pain, tightening in limbs” (Laughlin, 1975, p. 239). |

| 27 | As well, apparently, as virtually all of the Zinacantecs whose stories and dreams were published by Robert Laughlin (1976, 1977). Laughlin uses dashes to mark the ubiquitous elongated syllables throughout the Tsotsil renderings of the Zinacantec tales, as well as in their English translations. (Jakobson (1960, p. 354) mentions such elongation as relevant to the “emotive units” of even languages, like English, that make no referential use of phonemic vowel length, although it is nonetheless “a conventional, coded linguistic feature” that is “emotive.”). |

References

- Ameka, F. K., & Levinson, S. C. (2007). Introduction: The typology and semantics of locative predicates: Posturals, positionals, and other beasts. Linguistics, 45(5), 847–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlin, B. (2017). Tzeltal numeral classifiers: A study in ethnographic semantics. De Gruyter Mouton. (Original work published 1968). [Google Scholar]

- Berlin, B., & Kay, P. (1991). Basic color terms: Their universality and evolution. Univ of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Boersma, P., & Weenink, D. (2024). Praat: Doing phonetics by computer (Version 6.4.22) [Computer program]. Available online: http://www.praat.org/ (accessed on 5 October 2024).

- Bohnemeyer, J., & Brown, P. (2007). Standing divided: Dispositionals and locative predications in two Mayan languages. Linguistics, 45(5), 1105–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, P. (2011). Color me bitter: Crossmodal compounding in Tzeltal perception words. The Senses and Society, 6(1), 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, P., Sicoli, M., & Guen, O. (2021). Cross-speaker repetition and epistemic stance in Tzeltal, Yucatec, and Zapotec conversations. Journal of Pragmatics, 183, 256–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancian, F. (1965). Economics and prestige in a maya community: The religious cargo system in Zinacantan. Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cancian, F. (1972). Change and uncertainty in a peasant economy: The maya corn farmers of Zinacantan. Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Collavin, L. (2024, April 26). Personal communication.

- Collier, G. A. (1963). Color categories in Zinacantan [B.A. Honors thesis, Harvard College]. [Google Scholar]

- Crow, M., Suresh, H., Lee, J., & Gillis, J. (2022). Coexpression reveals conserved gene programs that co-vary with cell type across kingdoms. Nucleic Acids Research, 50(8), 4302–4314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Bois, J. W. (2007). The Stance Triangle. In R. Englebretson (Ed.), Stancetaking in discourse: Subjectivity, evaluation, interaction (pp. 139–182). Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- ELAN (Version 6.9) [Computer software]. (2024). Nijmegen: Max planck institute for psycholinguistics, The language archive. Available online: https://archive.mpi.nl/tla/elan (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Enfield, N. (2009). The anatomy of meaning: Speech, gesture, and composite utterances (language culture and cognition). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, C. (1981). Conversational organization: Interaction between speakers and hearers. Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin, C. (1986). Between and within: Alternative sequential treatments of continuers and assessments. Human Studies, 9, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, C. (2017). Co-operative action (Learning in doing: Social, cognitive and computational perspectives). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, C., & Goodwin, M. H. (1987). Concurrent operations on talk: Notes on the interactive organization of assessments. IPrA Papers in Pragmatics, 1(1), 1–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gossen, G. H. (1974). To speak with a heated heart: Chamula canons of style. In R. Bauman, & J. Sherzer (Eds.), Explorations in the ethnography of speaking (pp. 389–413). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, F., & Harrison, J. (1968). Spanish Elements in the Music of Two Maya Groups in Chiapas. Selected Reports in Ethnomusicology, 1(2), 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann, I., Haspelmath, M., & Cysouw, M. (2014). Identifying semantic role clusters and alignment types via microrole coexpression tendencies. Studies in Language. International Journal sponsored by the Foundation “Foundations of Language”, 38(3), 463–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haspelmath, M. (2019). Comparing reflexive constructions in the world’s languages. Ms. MPI-SHH Jena & Leipzig University. [Google Scholar]

- Haspelmath, M. (2023). Coexpression and synexpression patterns across languages: Comparative concepts and possible explanations. Frontiers in Psychology, 14(2023), 1236853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haviland, J. B. (1977a). Gossip as competition in Zinacantan. Journal of Communication, 27(1), 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haviland, J. B. (1977b). Gossip, reputation, and knowledge in Zinacantan. University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Haviland, J. B. (1981). Sk’op Sotz’leb; El Tzotzil de San Lorenzo Zinacantán (383p). Centro de Estudios Mayas, Instituto de Investigaciones Filológicas, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. [Google Scholar]

- Haviland, J. B. (1986a). ‘Con buenos chiles’: Talk, targets and teasing in Zinacantán. Text, 6(3), 249–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haviland, J. B. (1986b). Las máximas mínimas de la conversación natural de Zinacantán. Anales de Antropología, XX(1984), 221–256. [Google Scholar]

- Haviland, J. B. (1987). Fighting words: Evidential particles, affect, and argument. In J. Aske, N. Beery, L. Michaelis, & H. Filip (Eds.), Berkeley linguistics society proceedings of the 13th annual meeting, parasession on grammar and cognition (pp. 343–354). Berkeley Linguistics Society. [Google Scholar]

- Haviland, J. B. (1989). Sure, sure: Evidence and affect. Text, 9(1), 27–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haviland, J. B. (1990). ‘We want to borrow your mouth’: Tzotzil marital squabbles. Special issue of Anthropological Linguistics, 30(3&4), 395–447. [Google Scholar]

- Haviland, J. B. (1991, September 7). Chromatopoetics: Tzotzil color terms and spatial imagery. Paper presented to Cognitive Anthropology Research Group Seminar, Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics, Nijmegen, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Haviland, J. B. (1992/1994). Lenguaje ritual sin ritual. Estudios de Cultura Maya, XIX, 427–442. [Google Scholar]

- Haviland, J. B. (1994). Te xa setel xulem (The buzzards were circling): Categories of verbal roots in (Zinacantec) Tzotzil. Linguistics, 3, 691–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haviland, J. B. (1996). ‘We want to borrow your mouth.’ Tzotzil marital squabbles. In C. L. Briggs (Ed.), Disorderly discourse (pp. 158–203). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Haviland, J. B. (1997). Shouts, shrieks, and shots: Unruly political conversations in indigenous Chiapas. Pragmatics, 7, 547–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Haviland, J. B. (1999, ). ‘White-blossomed on bended knee’ linguistic mediations of nature and culture. Paper presented in the session “Verbal Practice: Construing the ‘Cultural’ by Constructing the ‘Natural’”, organized by Michael Silverstein. Annual Meetings of the American Ethnological Society, Portland, Or., March 26. (Book chapter for Festschrift for Terry Kaufman, edited by Roberto Zavala M. & Thomas Smith-Stark, 2003). Available online: https://pages.ucsd.edu/~jhaviland/Publications/BLOSSOMEdit.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- Haviland, J. B. (2000a). Early pointing gestures in Zinacantán. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology, 8(2), 162–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haviland, J. B. (2000b). Pointing, gesture spaces, and mental maps. In D. McNeill (Ed.), Language and Gesture: Window into Thought and Action (pp. 13–46). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Haviland, J. B. (2003). How to point in Zinacantán. In S. Kita (Ed.), Pointing: Where language, culture, and cognition meet (pp. 139–170). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Haviland, J. B. (2004a). Evidential mastery. In M. Andronis, E. Debenport, A. Pycha, & K. Yoshimura (Eds.), CLS 38-2, The panels (pp. 349–368). CLS. (Original work published 2002). [Google Scholar]

- Haviland, J. B. (2004b). Mayan master speakers—The archive of the indigenous languages of Chiapas. Collegium Antropologicum, 28(Suppl. 1), 229–239. [Google Scholar]

- Haviland, J. B. (2017). Mayan conversation and interaction. In J. Aissen, N. C. England, & R. Zavala (Eds.), The mayan languages (pp. 401–432). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Haviland, J. B., & Haviland, L. (1983). Privacy in a Mexican Indian village. In S. I. Benn, & J. Gaus (Eds.), Public and Private in Social Life (Volume 14, pp. 341–362). Croom Helm. [Google Scholar]

- Jakobson, R. (1957). Shifters, verbal categories, and the Russian verb. Russian Language Project, Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures, Harvard University. [Google Scholar]

- Jakobson, R. (1960). Closing statement: Linguistics and poetics. In T. A. Scbook (Ed.), Style in language (pp. 350–377). The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman, T. S. (1963). Tzeltal grammar [Ph.D. thesis, University of California]. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman, T. S. (2003). A preliminary Mayan etymological dictionary [unpublished document]. Available online: http://www.famsi.org/reports/01051/pmed.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- Kendon, A. (1967). Some functions of gaze-direction in social interaction. Acta Psychologica, 26(1967), 22–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendon, A. (1980). Gesture and speech: Two aspects of the process of utterance. In M. R. Key (Ed.), Nonverbal communication and language (pp. 207–277). Mouton. [Google Scholar]

- La Chica, M.-C. (2020). El Sombrerón en la tradición oral de Chiapas. Boletín de Literatura Oral, 10(2020), 27–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laughlin, R. M. (1975). Great Tzotzil Dictionary of San Lorenzo Zinacantán. Smithsonian Institution Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laughlin, R. M. (1976). Of wonders wild and new: Dreams from Zinacantán. Smithsonian Institution Press. [Google Scholar]

- Laughlin, R. M. (1977). Of Cabbages and Kings: Tales from Zinacantán. Smithsonian Institution Press. Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology, Number 23. [Google Scholar]

- Laughlin, R. M. (2008). Mol cholobil k’op ta sotz’leb, El gran diccionario Tzotzil de San Lorenzo Zinacantan. CIESAS, Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios superiores en antropologia social, CONACULTA, Consejo Nacional para la cultura y las artes. [Google Scholar]

- Maffi, L. (1990). Tzeltal Maya Affect Verbs: Psychological Salience and Expressive Functions of Language. In D. Costa (Ed.), Proceedings of the Sixteenth Annual Meeting of the 928 Berkeley Linguistics Society (pp. 61–72). Special Session on General Topics in American Indian Linguistics. Berkeley Linguistics Society. [Google Scholar]

- McNeill, D. (1992). Hand and mind: What gestures reveal about thought. University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- McNeill, D., Cassell, J., & McCullough, K.-E. (1994). Communicative effects of speech-mismatched gestures. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 27, 223–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McQuown, N. A. (1952). Review of Methods in Structural Linguistics by Zellig S. Harris. Language, 28, 495–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez González, J. (2012). Predicados expresivos e ideófonos en tseltal [Master’s Thesis, CIESAS]. [Google Scholar]

- Ringe, D. A. (1981). Tzotzil affect verbs. Journal of Mayan linguistics, 3, 61–85. [Google Scholar]

- Rossano, F., Brown, P., & Levinson, S. C. (2009). Gaze and questioning and culture. In J. Sidnell (Ed.), Conversation analysis: Comparative perspectives (pp. 187–249). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schegloff, E. A. (1984). On some gestures’ relation to talk. In J. M. Atkinson, & J. Heritage (Eds.), Structures of social action (pp. 266–296). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein, M. (1981). Metaforces of power in traditional oratory. University of Chicago. [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein, M. (2003). Indexical order and the dialectics of sociolinguistic life. Language & communication, 23(2003), 193–229. [Google Scholar]

- Zender, M. (2010). Baj ‘hammer’ and related affective verbs in Classic Mayan. The PARI Journal, 11, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Haviland, J.B. Mastery, Modality, and Tsotsil Coexpressivity. Languages 2025, 10, 169. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10070169

Haviland JB. Mastery, Modality, and Tsotsil Coexpressivity. Languages. 2025; 10(7):169. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10070169

Chicago/Turabian StyleHaviland, John B. 2025. "Mastery, Modality, and Tsotsil Coexpressivity" Languages 10, no. 7: 169. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10070169

APA StyleHaviland, J. B. (2025). Mastery, Modality, and Tsotsil Coexpressivity. Languages, 10(7), 169. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10070169