Abstract

This study examines around 350 handwritten letters from semiliterate soldiers during the Spanish Civil War, focusing on written orality and its interaction with scriptural conventions. The theoretical framework combines epistolography research (in which 20th-century popular correspondence reveals oral-like features) with studying the oral–scriptural interface. As detailed in the methodology, including the corpus compilation process, I present the selection criteria for the letters, which were segmented using the Val.Es.Co. model of discourse units. Segmentation facilitates my analysis, which addresses two aspects of the oral–scriptural interface: ritualized politeness in salutations and procedural devices that structure discursive moves. After summarizing the key findings, I discuss the hybrid nature of these letters, in which oral and written conventions intertwine.

1. Introduction

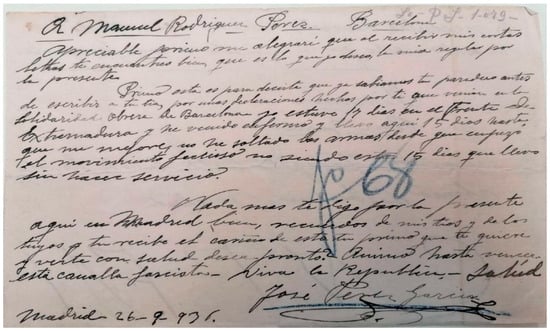

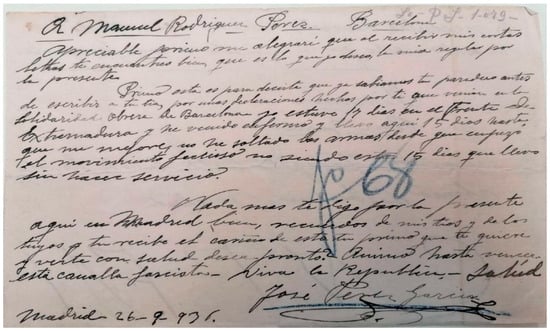

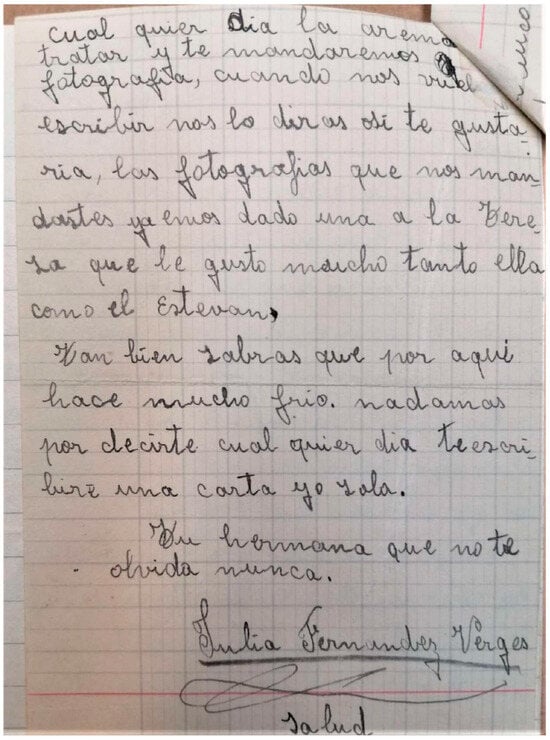

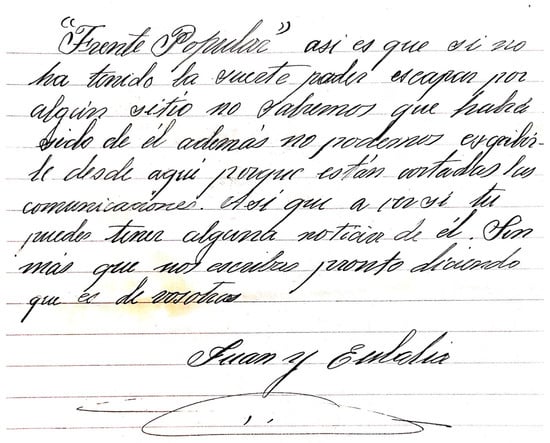

In this work, I examine two features of spoken language that are reflected in written letters: varying politeness in greetings and procedural devices of discursive moves. I aim to show how these two features, which are typical of spoken language, intertwine with the constraints imposed by the written genre of the letter, even when the writer has minimal or semiliterate education (in line with epistolary studies of 20th-century non-standard Italian; (Fresu, 2016; Cantoni, 2018, 2019; Cantoni & Fresu, 2020; Gibelli, 2022; Scivoletto, 2023, 2024). To this effect, I have compiled a corpus of around 350 documents of correspondence between soldiers and their families during the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939).1 One such example—see (1) below for the transcription and approximate translation—is as follows (Figure 1):

| (1) | |

| A Manuel Rodrigez Perez. Barcelona | |

| Apreciable primo me alegraré que al recibo de mis cortas | |

| letras te encuentres bien, que es lo que yo deseo, la mia regular por | |

| la presente((.)) | |

| Primo esta es para decirte que ya sabiamos tu paradero antes | |

| de escribir a tu tia por unas declaraciones hechas por ti que venian en la | |

| Solidaridad Obrera de Barcelona yo estuve 14 dias en el Frente de | |

| Extremadura yo he venido enfermo y llevo aquí 15 dias hasta | |

| que me mejore no he soltado las armas desde que empezó | |

| el movimiento faccioso no ((siendo)) estos 15 días que llevo | |

| sin hacer servicio. | |

| Nada mas te digo por la presente | |

| aqui en Madrid bien, recuerdos de mis tios y de los | |

| tuyos y tu recibe el cariño de este tu primo que te quiere | |

| y verte con salud desea pronto((!)) Primo hasta vencer | |

| esta canalla facciosa—Viva la Republica.—Salúd | |

| Madrid 26-9-[1]936. | José Pérez Garcia |

| ‘To Manuel Rodríguez Pérez. Barcelona | |

| Dear cousin, I will be happy to hear that upon receiving my brief | |

| letters, you are doing well, which is what I wish for, as for me, I am doing | |

| so-so at the moment((.)) | |

| Cousin, this is to tell you that we already knew your whereabouts before | |

| writing to your aunt, based on some statements made by you that appeared in | |

| Solidaridad Obrera from Barcelona. I was for 14 days at the Front of | |

| Extremadura. I have come back sick and have been here for 15 days until | |

| I recover. I have not put down my weapons since the beginning | |

| of the fascist movement, except for these 15 days | |

| I have been off duty. | |

| I have nothing more to tell you for now | |

| here in Madrid, all is well. Greetings from my uncles and | |

| yours, and you receive the affection of this cousin who loves you | |

| and wishes to see you healthy soon((!)) Cousin, until we defeat | |

| this fascist scum—Long live the Republic.—Hail | |

| Madrid 26-9-[1]936. | José Pérez García‘ |

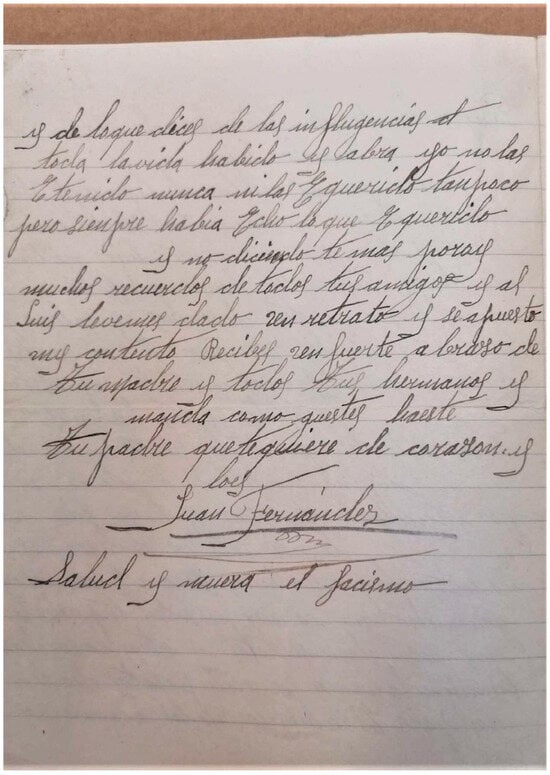

Figure 1.

A letter to a militiaman from his cousin (General Archive of the Spanish Civil War in Salamanca).

This letter was sent to a militiaman on the front lines by his cousin. The letter exhibits the conventional structure of this genre (traditionally taught in 20th-century Spanish primary schools; Sierra Blas, 2003):

- -

- It includes an opening paragraph that serves as the salutation (Dear cousin, I will be happy to hear that upon receiving my brief…).

- -

- Subsequently, a second paragraph is included, with the body of the letter, that contains information about the cousin’s situation.

- -

- The last paragraph contains the farewell, including regards from other family members.

Given the brevity of this letter, the salutation–body–farewell structure is clearly distributed across three distinct paragraphs; therefore, as a standardized letter, it is divided into three regulated parts, which are preceded by a heading with the recipient’s details (To Manuel Rodríguez Pérez. Barcelona) and conclude with the sender’s signature (José Pérez García), along with the date and location (Madrid. 26-9-[1]936).2

The letter in Figure 1 shows the typical constraints of the epistolary genre. Such constraints, characteristic of written texts, align with the Romanists’ concept of discourse tradition (Schlieben-Lange, 1983; Koch, 1997; Borreguero Zuloaga, 2006; Jacob & Kabatek, 2001; Kabatek, 2011, 2021; Rosemeyer, 2015; Octavio de Toledo, 2018), which are understood as “the repetition of a text, a text-type or a particular way of writing or speaking that acquires its own sign value” (Kabatek, 2005, p. 159). These “social, normative, and historical molds commonly adopted in producing discourse” (Pons Bordería & Salameh Jiménez, 2024, p. 288) are particularly evident in written texts. Henceforth, we will refer to these conventions as scripturality (López-Serena, 2021), of which even people with a semiliterate education have some degree of intuitive awareness (Pardo Llibrer, 2025).

Despite the force of the epistolary discourse tradition, features typical of spoken language are also observed; such features correspond to phenomena that—while occurring in written text—are linked to conversational interaction. A clear example is the use of Primo (‘cousin’) as a vocative; in the salutation, Primo fits within the typical scriptural mold of greetings (Dear cousin), but in the body of the letter, it addresses the reader as in a spoken exchange (Cousin, this is to tell you that…). Similarly, in the farewell, Primo is used as an appellation to urge resistance against the fascists (Cousin, until we defeat this fascist scum). Although these instances are written from a material standpoint, they are oral phenomena. Following López-Serena’s (2007) notion of conceptual orality, I will henceforth refer to them as orality. See Figure 2 for a schematic representation.

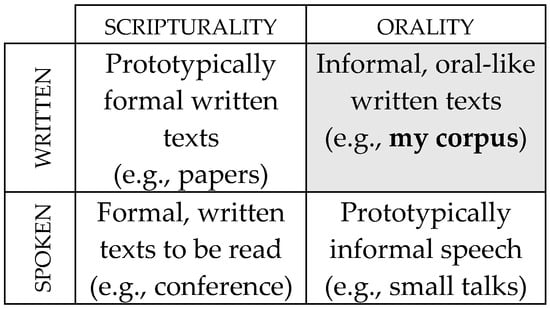

Figure 2.

Conceptual distinctions among spoken—written—scriptural—oral.

Both concepts, scripturality and orality, are reflected in the correspondence of semiliterate people, leading to a historical overview of the way in which letters were written during the first half of the 20th century. Thus, my theoretical framework (Section 2) combines letter studies (Section 2.1), since 20th-century popular correspondence allows for the description of certain aspects of oral language, along with the oral–scriptural interface study (Section 2.2), which involves two necessary levels of analysis. The methodology of my work (Section 3) concerns how the corpus has been compiled: the archival research undertaken and the criteria used to select the letters for analysis (Section 3.1). Each letter has also been segmented according to the Val.Es.Co. model of discourse segmentation (Section 3.2). My analysis in Section 4 focuses on two aspects of the oral–scriptural interface: ritualized politeness in the salutation, which is subject to typical epistolary molds, compared to those parts of the letter that reflect oral language (Section 4.1), and procedural formulae as markers of discursive moves (Section 4.2). The conclusions (Section 5) provide a final summary of the components that shape the hybrid nature of letters.

2. Theoretical Framework

In this work, I combine linguistic research on letters as a source of diachronic data (Section 2.1) with the analysis of oral elements that intertwine with the scriptural molds of this written genre (Section 2.2). The letters I have compiled belong to ordinary popular correspondence; they manifest the way in which Spaniards with little or no education, who inevitably relied on their spoken competence as sporadic writers, used to write in the first half of the 20th century.

2.1. Soldiers’ Popular Correspondence Within Letter Studies

Letter studies broadly refer to research on the genre of epistolography. Now, epistolography can encompass the following different subgenres:

- -

- Literary epistolography: considers letters as a literary, fictional correspondence genre (Guillén, 1991; Antón, 2019);

- -

- Epistolary rhetoric: considers letters as a form of essay writing (Beltrán Almería, 1996; Sáez Rivera, 2017; Azofra Sierra, 2023);

- -

- Official or diplomatic epistolography: involves the historical study of the correspondence between prominent figures of a historical period (Octavio de Toledo, 2023; Borreguero Zuloaga, 2024; Albitre Lamata & Martín Cuadrado, 2024).

In contrast to these subgenres of epistolography, my study focuses on private epistolography—that is, letters exchanged between individuals that do not serve any of the aforementioned purposes.

However, collections of private letters typically come from educated individuals and are tied to “the needs of the society at the time, [such as] disseminating a code of behavior” (Sierra Blas, 2015, p. 107).3 As a result, these letters have primarily been examined from literary and historiographical perspectives (see López Izquierdo & Taillot, 2023), leaving the following three gaps in the field of epistolography studies that this work aims to fill:

- Researchers have rarely used private letters as a source of Spanish linguistic data. Notable exceptions include Cano Aguilar’s (1996, p. 380) work on 17th-century scribe-mediated letters from the Spanish viceroyalties, Pérez-Salazar’s (2002, 2004) studies on cohesive markers in Romantic-era correspondence (19th century and earlier),4 and some works on historical politeness (Almeida, 2016; Albitre Lamata, 2020; Bello Hernández, 2020, 2022; Garrido Martín, 2021).

- Therefore, to the best of my knowledge, very few linguistic studies have specifically focused on 20th-century letters, aside from some discursive works on correspondence address forms (Molina Martos, 2021) or the illocutionary purposes of letters (Rodríguez Gallardo, 2014); these authors tackle cases that are fundamentally “family letters” (Briz Gómez, 1998) (i.e., letters addressed to relatives, friends, or fellows).

- Finally, there is a significant gap regarding private letters written by people with little formal schooling. Unlike the letters written by members of the educated middle class or elite, I am specifically interested in the former, which are less constrained by prescriptive norms and less driven by informative purposes, instead prioritizing interpersonal, affiliative communication (Briz Gómez, 2010; Val.Es.Co. Research Group, 2014), especially in war contexts (Scivoletto, 2024).

Lacking a better term to distinguish these 20th-century letters from those produced in higher sociocultural contexts, I will henceforth refer to them as popular epistolography, thereby highlighting the informal, even conversational, register in which militiamen and their relatives and friends communicated.

Contrary to the traditional Ciceronian assumption of the letter as a conversation between absent parties, semiliterate militiamen’s letters accomplish the demand for immediate communication (Koch & Oesterreicher, 1990; López-Serena & Sáez Rivera, 2018); they convey information about the war, but their dialogical structure—which is anchored throughout greetings and farewells—presents an interpersonal function. Moreover, as Scivoletto (2024, p. 315) notes, “[t]he use of performatives, meta-communicative markers, or verbs announcing an action can be traced in all texts of the correspondence.”5 In summary, I contend that semiliterate soldiers’ letters reproduce orality for the following reasons:

- -

- They are correspondences that fulfill the functions of orality; the salutation–body–farewell structure does not lie in a sort of regulated instruction but rather in their predominantly conversational markers (recall vocative uses in Figure 1).

- -

- The letters are, so to speak, incidentally transactional since, overall, they accomplish non-informative needs (but interactional ones).

- -

- Scripturality within the letter is often violated by the soldiers, who unconsciously replace normative conventions with spoken pragmatic strategies (as my analysis shows in Section 4).

The study of popular correspondence is related to the study of the oral–scriptural interface, which was especially prominent in 20th-century language due to the factors explained in the following subsection.

2.2. Data from the 20th Century: A Time for the Oral–Scriptural Merge

Hispanic philology has generally assumed that the Spanish Language reached its final stage of development in the 18th century (Lapesa, 1977; Eberenz, 1991) or, at most, in the 19th century (Melis et al., 2003). Yet, the diachronic study of the 20th century as a separate linguistic stage remained unexplored until Pons Bordería’s (2014b) work; this author argues that some phenomena were either previously undocumented or emerged in the 20th century because this stage offers data that are unique to this historical context.

From a historical, point of view, Spain significantly shifted in the 20th century from an agrarian, poorly alphabetized society to an industrial country, along with universal literacy, which “implies the access of virtually the entire population to both the comprehension and production of written material” (Pons Bordería, 2014b, p. 1001).6 According to the changes pointed out by Pons Bordería (2014b), the century is divided into two main periods: the first period, which lasted until the 1960s, and the second period, which has lasted from the 1960s onward, when the main changes began; my approach to written orality during the Spanish Civil War fits into the earlier period.

From a linguistic research perspective, the following three main features have been observed in Peninsular Spanish that have not been attested in periods earlier than the 20th century:

- In the first place, many of the linguistic changes described by scholars stem from sources that were previously unavailable to researchers, such as oral corpora (Pons Bordería, 2023), typed transcriptions (Cuenca Ordinyana, 2014; Estellés, 2020), and audio recordings from radio and television (Salameh Jiménez, 2024). This allows us to compare scriptural, highly elaborated texts (such as political speeches or parliamentary discussions) with speakers’ default orality (i.e., informal conversations).

- In the second place, Salameh Jiménez (2024) has demonstrated that 20th-century Peninsular Spanish underwent a gradual process of colloquialization; traits once associated with informal language have widely spread to the realm of formal registers (Briz Gómez, 2010; Val.Es.Co. Research Group, 2014; Pons Bordería, 2022). Other researchers have pointed out a similar process for English (Biber, 2012; Biber & Gray, 2013). Nevertheless, Salameh Jiménez’s theory of colloquialization is orthogonal: it includes the introduction of conversational features into formal registers as features from orality becoming suitable within scriptural genres, regardless of whether they are written or spoken.

- Finally, the 20th century stands out for discursive changes. The new available sources are reshaping the relationship between oral and written data; additionally, colloquialization seems to have influenced formal norms more significantly than in previous periods. Both factors have led to a focus on pragmatic elements, such as discourse markers (Octavio de Toledo, 2002; Estellés, 2009; Pons Bordería, 2014a), approximative elements (Pardo Llibrer, 2023; Llopis & Jansegers, 2024), and conversational formulae (Salameh Jiménez, 2023). The pragmatic perspective in these works is fine-grained; it addresses the grammaticalization of these elements and their synchronic, present-day polyfunctionality, distinguishing between scriptural and oral levels without treating them as equivalent to the written and spoken levels, respectively.

In this vein, popular correspondence offers new data regarding these three changes; it poses a new source of—albeit written—oral data and, depending on the extent of its scriptural molds, provides information about the degree of colloquialization in the first half of the 20th century. In the next section (Section 3), I outline my methodological considerations: corpus documentation and selection criteria for searching letters (Section 3.1). I also briefly exemplify the units of analysis employed in segmenting and labeling the corpus (Section 3.2).

3. Methodology

As Sierra Blas and Castillo Gómez (2007) note, unlike other materials (such as administrative, legal, or military documentation), popular epistolography is not typically found in historical archives. Therefore, the compilation has been autonomous and has involved carrying out manual searches in the various consulted files.

The corpus was obtained through successive visits during 2023 and 2024 to the Archivo General de la Guerra Civil (‘General Archive of the Spanish Civil War’—AGGC) in Salamanca. This archive houses the documents seized after the war by the Rebel faction’s brigada político-social (‘political-social bureau of investigation’) for the so-called Special Tribunal for the Repression of Masonry and Communism (for identification purposes). The files were treated as documentary evidence from the war period against soldiers of the Republican faction and include:

- -

- Personal correspondence between republican militiamen and their families or friends;

- -

- Denunciations from the Republican faction against civilians accused of rebellion;

- -

- Requests for clemency;

- -

- Credentials for revolutionary committees;

- -

- Letters of recommendation for trade unions.

In sum, around 350 handwritten documents have been compiled and scanned, all of which are cases of written orality, mostly popular letters (317 documents), sent from or received by the front (totaling approximately 80.000 words).

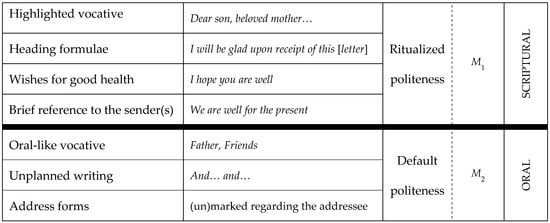

As shown in Table 1, the documented correspondence for this work consists of handwritten letters (predominantly personal, some politically marked) with a medium or low degree of scriptural proficiency. However, not every handwritten document automatically constitutes a manifestation of written orality; it is possible to find intimate cultured or semicultured correspondence (e.g., the case of the so-called madrinas de guerra, ‘war godmothers’—instructed women’s letters addressed to soldiers to motivate them; Sierra Blas, 2003). Therefore, different criteria have been applied to select popular letters.

Table 1.

Corpus overview.

3.1. Selection Criteria for Letters

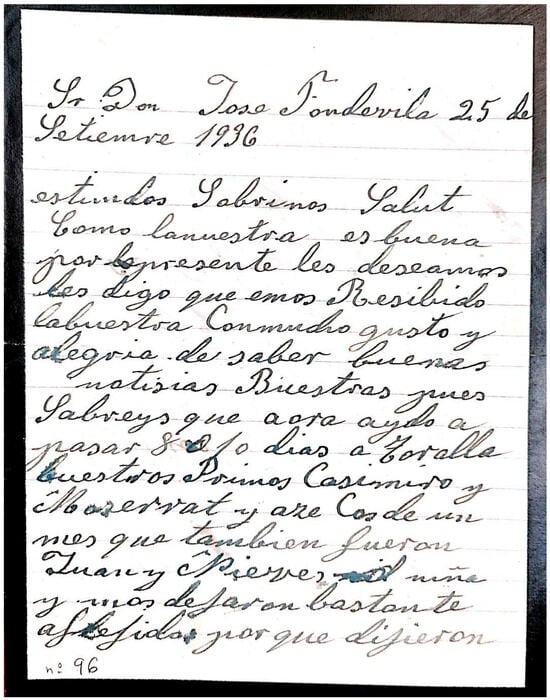

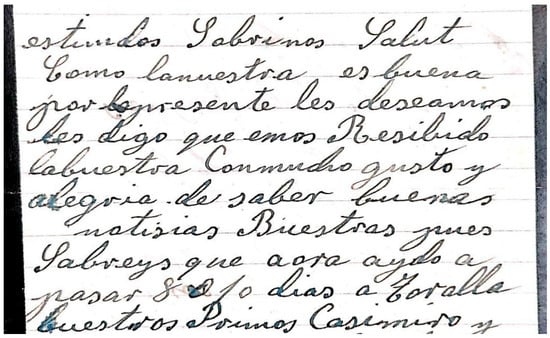

The selection criteria are based on a set of linguistic clues ranging from the most oral to the most scriptural. To exemplify the selection process, see Figure 3—transcription and translation below in (2):7

| (2) |

| Sr ((.)) Don Jose Fondevila 25 de |

| Setiembre 1936 |

| estimados Sobrinos Salut |

| Como lanuestra es buena |

| por la presente les deseamos |

| les digo que [h]emos Resibido |

| labuestra Conmucho gusto y |

| alegría de saber buenas |

| notisias Buestras pues |

| Sabreys que a[h]ora ayudo a |

| pasar 8 o 10 dias a ((Zoralla)) |

| buestros Primos Casimiro y |

| Monserrat y [h]aze Cos[a] de un |

| mes que tambien fueron |

| Juan y Nieves ((el)) niño |

| y nos dejaron bastante |

| aflejidos porque dijieron |

| […] |

| ‘Mr ((.)) Don Jose Fondevila The 25th of |

| September, 1936 |

| Dear Nephews Hail |

| As our[health] is good |

| hereby we wish you [the same] |

| I tell you that we have Received |

| your[letter] withmuch pleasure and |

| joy of having heard good |

| news from You well |

| You should know that now I help to |

| spend 8 or 10 days in ((Zoralla)) |

| your cousins Casimiro and |

| Monserrat and it’s been About |

| a month since they also went |

| Juan and Nieves ((the)) child |

| and they left us quite |

| afflicted because they said |

| […]’ |

Figure 3.

Fragment of a letter to a militiaman from his uncle.

Several indicators allow us to classify the example letter in Figure 3 as a piece of popular correspondence. I have organized these indicators into three criteria sets as follows:

- Graphic criteria. Graphic criteria refer to the visual disposition of handwriting, which can indicate semiliterate education. Figure 3 shows an uneven distribution and inclination of lines on the page; particularly relevant is the arrangement of margins and paragraphs (if present; no paragraph distribution in Figure 3) and the graphic merging of words (e.g., conmucho gusto, ‘withmuch pleasure’).

- Orthographic criteria. Given its prestige, strongly linked to formal education, failing orthography has been central for the corpus selection: failures in the standardized spelling or in the proper use of capital letters (e.g., notisias Buestras, instead of noticias vuestras; ‘news from you’). The absence or improper use of punctuation marks structuring the content (barely observed in Figure 3) is also a key (see Cantoni, 2019).

- Stylistic criteria. Even in letters with proper spelling, scriptural deficiencies can be found. These include the misuse of the salutation–body–farewell structure (e.g., greetings in Figure 3 do not follow the writing conventions of the time), the use of oral-like discourse connectors (pues, ‘well’), and textual–structuring procedural elements (some of which are analyzed in Section 4); coherence issues, such as abrupt topic shifts (‘I tell you that we have Received’), are also remarkable.

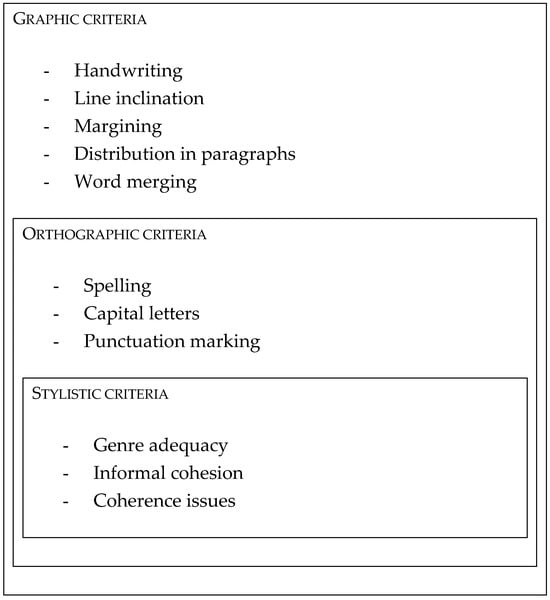

In short, the three sets of selection criteria are applied as follows (see Figure 4):

Figure 4.

Criteria sets for the identification of popular correspondence.

As shown in Figure 4, the three criteria sets overlap; this means that a letter with oral traits at the graphic level often entails oral traits in the other two sets. However, a letter with stylistic errors may still be entirely acceptable from an orthographic perspective. Due to a lack of formal education (and sometimes due to space constraints), soldiers hardly know the letter genre, providing a distribution of paragraphs that may conflict with stylistic conventions. In addition, information is based on communicative needs (discussing the war, asking about loved ones) and presented in uneven fragments. These fragments constitute discourse units, in which letters are segmented for my analysis.

3.2. The Val.Es.Co. Model of Segmentation in Discourse Units

As Borreguero Zuloaga (2023, p. 334) claims, the models of “segmentation of discourse and utterances in units—which do not correspond to syntactic units […] realized that syntactic categories were insufficient to explain the variety of constructions which hardly ever appear in written texts.” In other words, segmentation models have originally been interested in spoken language, later becoming a complementary tool in textual linguistics (Borreguero Zuloaga, 2023, 2024; Girón Alconchel, 2016, 2018). In this sense, the Val.Es.Co. (Valencia Español Coloquial) model has traditionally dealt with spoken conversations (Val.Es.Co. Research Group, 2014; Cabanes Pérez, 2020; Pons Bordería, 2022; Badia & Espinosa-Guerri, 2024), as well as related phenomena, such as reformulation (Salameh Jiménez, 2021) or pragmatic markers (Pons Bordería et al., 2023). Recently, the Val.Es.Co. Research Group has developed an extension of the model for written texts (Pons Bordería & Borreguero Zuloaga, 2024; Salameh Jiménez & Pardo Llibrer, 2024), which I have applied to my corpus.

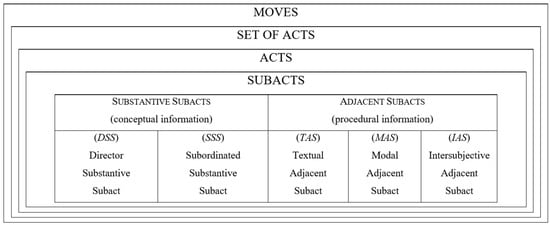

The Val.Es.Co. model uses four units for textual segmentation (see Figure 5):

Figure 5.

Val.Es.Co. units for scriptural analysis.

The units are hierarchical: higher-level units contain lower-level ones. Moreover, although they can coincide, these units do not necessarily correspond to sentences or paragraphs, making them adaptable to texts of written orality.

- -

- Acts and subacts. The act is the minimal communicative unit in the Val.Es.Co. model and is understood as an utterance with its own propositional content and illocutionary force. In turn, an act is composed of one or more subacts; the subact is the minimal informational unit and delimits the conceptual information of the act from the procedural information. Returning to Figure 1:

Figure 1.

A letter to a militiaman from his cousin (General Archive of the Spanish Civil War in Salamanca).

The body of the letter—in this case, the second paragraph—can be segmented into acts and subacts (indicated by hashtags and curly braces, respectively) as follows:

| (3) |

| #IAS{Primo}IAS TAS{esta es para decirte que}TAS DSS{ya sabiamos tu paradero antes |

| de escribir a tu tia}DSS SSS{por unas declaraciones hechas por ti que venian en la |

| Solidaridad Obrera de Barcelona}DSS# #DSS{yo estuve 14 dias en el Frente de |

| Extremadura}SSS# #DSS{yo he venido enfermo y llevo aquí 15 dias hasta |

| que me mejore}DSS# #DSS{no he soltado las armas desde que empezó |

| el movimiento faccioso no ((siendo)) estos 15 días que llevo |

| sin hacer servicio.}DSS# |

| ‘#IAS{Cousin,}IAS TAS{this is to tell you that}TAS DSS{we knew your whereabouts |

| writing to your aunt,}DSS SSS{based on some statements made by you that appeared in |

| Solidaridad Obrera from Barcelona.}SSS# #DSS{I was for 14 days at the Front of |

| Extremadura.}DSS# #DSS{I have come back sick and have been here for 15 days until |

| I recover.}DSS# #DSS{I have not put down my weapons since the beginning |

| of the fascist movement, except for these 15 days |

| I have been off duty.}DSS#’ |

Each act constitutes a fully communicative unit (i.e., a linguistic segment that can work separately from other acts) and is composed of at least one director substantive subact (DSS, implying the central information); subordinated substantive subacts (SSS), in turn, present conceptual information depending on the former. Furthermore, an act can also have adjacent subacts that involve procedural information: textual–organizing adjacent subacts (TAS), modal adjacent subacts (MAS), or intersubjective adjacent subacts (IAS). For instance, the first act in (3) presents a vocative (IAS{Cousin,}IAS), which is labeled as an intersubjective adjacent subact (IAS), and a discourse framing device (TAS{this is to tell you that}TAS), which is labeled as a textual adjacent subact (TAS); both IAS and TAS serve procedural purposes. That way, oral-like elements, such as vocatives or performative expressions, are segmented into units that are distinguishable from the strictly propositional discourse units.

- -

- Set of acts. The unit immediately above the act is the so-called set of acts (SoA). A set of acts groups two or more acts formally and topically related. For example, the body of the letter constitutes a set of acts; it addresses topics that are different from those in the salutation (greetings) or the farewell (regards), and, in this case (Figure 1), it is graphically separated into a paragraph. Nonetheless, a set of acts does not necessarily correspond to a separate paragraph. See (4) for the segmentation of the farewell:

| (4) |

| #TAS{Nada mas te digo por la presente}TAS |

| DSS{aqui en Madrid bien,}DSS# #DSS{recuerdos de mis tios y de los |

| tuyos}DSS# #DSS{y tu recibe el cariño de este tu primo que te quiere}DSS |

| SSS{y verte con salud desea pronto((!))}SSS# #IAS{Primo}IAS DSS{hasta vencer |

| esta canalla facciosa}DSS# #DSS{– Viva la Republica.}DSS MAS{– Salúd}MAS# |

| #TAS{‘I have nothing more to tell you for now.}TAS |

| DSS{Here in Madrid, all is well.}DSS# #DSS{Greetings from my uncles and |

| yours,}DSS# #DSS{and you receive the affection of this cousin who loves you}DSS |

| SSS{and wishes to see you healthy soon((!))}SSS# #IAS{Cousin,}IAS DSS{until we defeat |

| this fascist scum}DSS# #DSS{– Long live the Republic.}DSS# #DSS{– Hail’}DSS# |

As seen in (4), the first three acts are cases of politeness, whereas the last three acts constitute an exhortation to struggle. Therefore, within the farewell paragraph, two topically distinguishable sets of acts can be identified, i.e., SoA1 and SoA2 in (5), as follows:

| (5) |

| SoA1{#TAS{‘I have nothing more to tell you for now.}TAS |

| DSS{Here in Madrid, all is well.}DSS# #DSS{Greetings from my uncles and |

| yours,}DSS# #DSS{and you receive the affection of this cousin who loves you}DSS |

| SSS{and wishes to see you healthy soon((!))}SSS#}SoA1 SoA2{#IAS{Cousin,}IAS DSS{until we defeat |

| this fascist scum}DSS# #DSS{– Long live the Republic.}DSS# #DSS{– Hail’}DSS#}SoA2 |

Finally, sets of acts can be grouped by so-called moves, which combine conceptual and procedural information with discourse traditions.

- -

- Moves. The move is the highest unit of written discourse. Salameh Jiménez and Pardo Llibrer (2024, p. 31) define the move as the unit “that groups two or more sets of acts around textual relationships,” and such textual relationships “determine the scriptural progression.”8 A move is a higher discursive mold made up of the contents of the paired sets of acts, but it is also a textual unit with its own identity, as demonstrated by the fact that some procedural elements fit in a given move, while others do not. For instance, in (5), the text-structuring adjacent subact TAS{I have nothing more to tell you for now}TAS heads the farewell move but would be infelicitous between both sets of acts. Then, the farewell paragraph in (6) is a move (M) (indicated within brackets) containing two sets of acts, as follows:

| (6) |

| M[SoA1{#TAS{‘I have nothing more to tell you for now.}TAS |

| DSS{Here in Madrid, all is well.}DSS# #DSS{Greetings from my uncles and |

| yours,}DSS# #DSS{and you receive the affection of this cousin who loves you}DSS |

| SSS{and wishes to see you healthy soon((!))}SSS#}SoA1 SoA2{#IAS{Cousin,}IAS DSS{until we defeat |

| this fascist scum}DSS# #DSS{– Long live the Republic.}DSS# #DSS{– Hail’}DSS#}SoA2]M |

The move is an especially useful unit when considering scriptural conventions; the letter genre adheres to a discourse tradition that favors certain connection forms and rhetorical organization. On the other hand, when focusing on the (sets of) acts, and particularly on the subacts, one can also observe which parts of the letter are more influenced by orality.

Ultimately, the segmentation of letters in popular epistolography follows three steps:

- -

- 1. First, segmentation into acts and subacts, denoting the influence of oral-like devices and informative structure;

- -

- 2. Second, segmentation into sets of acts, grouping utterances into topic blocks to compare them with the graphic distribution in paragraphs;

- -

- 3. Finally, segmentation into moves, denoting the degree of scripturality (which informs about the militiamen’s instruction).

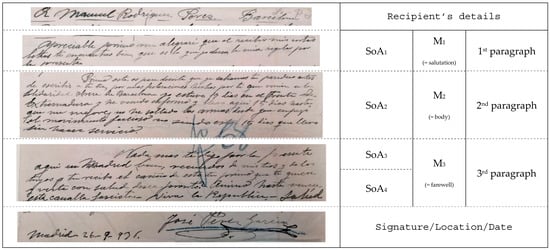

Accordingly, the full segmentation of the letter in Figure 1 is shown in (7) and summarized at a glance in Figure 6 below:

| (7) | |

| A Manuel Rodrigez Perez. Barcelona | |

| M1[SoA1{#IAS{Apreciable primo}IAS DSS{me alegraré que al recibo de mis cortas | |

| letras te encuentres bien,}DSS SSS{que es lo que yo deseo, }DSS# #DSS{la mia regular por | |

| la presente((.))}DSS#}SoA1]M1 | |

| M2[SoA2{#IAS{Primo}IAS TAS{esta es para decirte que}TAS DSS{ya sabiamos tu paradero antes | |

| de escribir a tu tia}DSS SSS{por unas declaraciones hechas por ti que venian en la | |

| Solidaridad Obrera de Barcelona}DSS# #DSS{yo estuve 14 dias en el Frente de | |

| Extremadura}SSS# #DSS{yo he venido enfermo y llevo aquí 15 dias hasta | |

| que me mejore}DSS# #DSS{no he soltado las armas desde que empezó | |

| el movimiento faccioso no ((siendo)) estos 15 días que llevo | |

| sin hacer servicio.}DSS# SoA2]M2 | |

| M3[SoA4{#TAS{Nada mas te digo por la presente}TAS | |

| DSS{aqui en Madrid bien,}DSS# #DSS{recuerdos de mis tios y de los | |

| tuyos}DSS# #DSS{y tu recibe el cariño de este tu primo que te quiere}DSS | |

| SSS{y verte con salud desea pronto((!))}SSS#}SoA4 SoA5{#IAS{Primo}IAS DSS{hasta vencer | |

| esta canalla facciosa}DSS# #DSS{– Viva la Republica.}DSS MAS{– Salúd}MAS#}SoA5]M3 | |

| Madrid 26-9-[1]936. | José Pérez Garcia |

| ‘To Manuel Rodríguez Pérez. Barcelona | |

| M1[SoA1{#IAS{Dear cousin,}IAS DSS{I will be happy to hear that upon receiving my brief | |

| letters, you are doing well,}DSS SSS{which is what I wish for,}DSS# #DSS{as for me, I am doing | |

| so-so at the moment((.))}DSS#}SoA1]M1 | |

| M2[SoA2{#IAS{Cousin,}IAS TAS{this is to tell you that}TAS DSS{we already knew your whereabouts | |

| writing to your aunt,}DSS SSS{based on some statements made by you that appeared in | |

| Solidaridad Obrera from Barcelona.}SSS# #DSS{I was for 14 days at the Front of | |

| Extremadura.}DSS# #DSS{I have come back sick and have been here for 15 days until | |

| I recover.}DSS# #DSS{I have not put down my weapons since the beginning | |

| of the fascist movement, except for these 15 days | |

| I have been off duty.}DSS#}SoA2]M2 | |

| M3[SoA4{#TAS{‘I have nothing more to tell you for now.}TAS | |

| DSS{Here in Madrid, all is well.}DSS# #DSS{Greetings from my uncles and | |

| yours,}DSS# #DSS{and you receive the affection of this cousin who loves you}DSS | |

| SSS{and wishes to see you healthy soon((!))}SSS#}SoA4 SoA5{#IAS{Cousin,}IAS DSS{until we defeat | |

| this fascist scum}DSS# #DSS{– Long live the Republic.}DSS# #DSS{– Hail’}DSS#}SoA5]M3 | |

| Madrid 26-9-[1]936. | José Pérez García’ |

Figure 6.

Segmentation overview.

Although the recipient’s information, signature, date, and location are indispensable elements in a letter, they are not labeled in the segmentation, as they are extralinguistic rather than discursive material.

Figure 6 offers an overview of the segmentation process that I applied to all the letters in my corpus. As shown, there is not necessarily a correspondence between paragraphs and topic units (SoA). Indeed, my findings concern the correspondence of certain pragmatic phenomena in moves and sets of acts, even though the semiliterate soldier does not follow the standard written distribution. In the next section, I analyze two of these phenomena.

4. Analysis

The segmentation of letters in subacts, acts, sets of acts, and moves allows for the description of some pragmatic phenomena that reflect how orality and scripturality intertwine in popular correspondence. In this section, I explore the contrast between scripturally ritualized politeness in greetings and default oral-like expressions by switching to the body of the letter (Section 4.1), as well as the procedural markers that signal a new discourse unit (Section 4.2).

As a clarification prompted by two kind reviewers, I will hereafter refer to “ritualized politeness” as the writing conventions of epistolary discourse and to “default politeness” as oral features which—albeit not strictly instances of positive politeness in Brown and Levinson’s (1987) terms—do echo face-to-face communication and strengthen interpersonal bonds among speakers (Haverkate, 1994; Bravo & Briz, 2004).

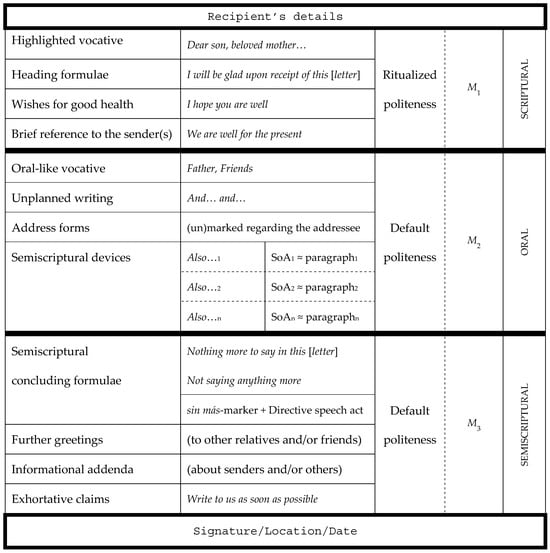

4.1. Ritualized Politeness vs. Default Politeness

Some analyses of 16th-century letters (Fernández Alcaide, 2009; Albitre Lamata, 2020) have pointed out that the main politeness strategies of epistolography tend to appear in the salutation—see Zieliński (2019b, 2020) for a historical typology of Hispanic greeting practices from its origins up to the 19th century. In this vein, the greetings in the salutation serve a linguistic and social function. They serve a linguistic function, since salutation constitutes the required header of any letter, and a social function, indicating the hierarchical relationship between sender and recipient.

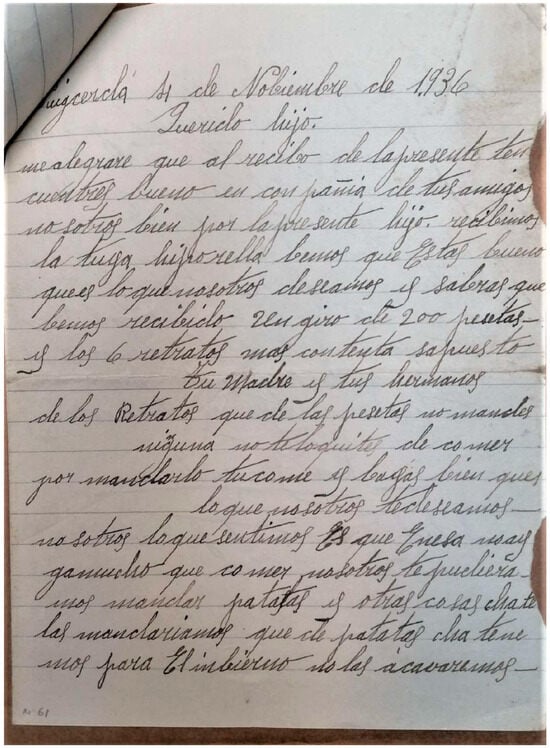

Official, high-class epistolography clearly shows a salutation that serves diplomatic or hedging—captatio benvolentiae—purposes. Now, such ritualized politeness is also systematically observed in popular letters. For instance, see Figure 7 and the transcription in (8):

| (8) |

| Puigcerdá 14 de Noviembre de 1.936 |

| Querido hijo. |

| mealegrare que al recibo de la presente ten |

| cuentres bueno en compañia de tus amigos |

| nosotros bien por la presente hijo recibimos |

| la tuya hiporella bemos que Estas bueno |

| que es lo que nosotros deseamos y sabras que |

| bemos recibido un giro de 200 pesetas |

| y los 4 retratos mas contenta sapuesto |

| tu madre y tus hermanos |

| de los Retratos que de las pesetas no mandes |

| ninguna no te lo quites de comer |

| por mandarlo tu come y bayas bien ques |

| lo que nosotros tedeseamos |

| nosotros lo que sentimos Es que fuera no ay |

| gamucho que comer nosotros te pudiera- |

| mos mandar patatas y otras cosas chate |

| las mandariamos que de patatas cha tene |

| mos para El inbierno no las acavaremos |

| ---------------------------- [page break] ---------------------------- |

| y de lo que dices de las influgencias (( )) |

| toda la vida habido y abra. yo no las |

| E tenido nunca ni las E querido tanpoco |

| pero siempre habia Echo lo que E querido |

| y no diciendo te mas poray |

| muchos recuerdos de todos tus amigos y al |

| Luis levemos dado un retrato y se apuesto |

| muy contento Recibe un Fuerte abrazo de |

| Tu padre y todos Tus hermanos y |

| Manda como ((estes haeste)) |

| Tu padre que te quiere de corazon y |

| loes |

| Juan Fernández |

| Salud y muera el fascismo |

| ‘Puigcerdá, November 14, 1936 |

| Dear son. |

| I will be glad that upon receipt of this letter you |

| ’ll find yourself well in the company of your friends |

| we are well for the present son we received |

| your letter and through it we know that you are well |

| which is what we wish for and you may know that |

| we have received a money order of 200 pesetas9 |

| and the 4 portraits happier have been |

| your mother and your siblings |

| about the portraits than about the pesetas do not send |

| any [money], do not deprive yourself of food |

| to send it [money] You eat and be well which |

| is what we wish for you |

| What saddens us is that out there there |

| is not much to eat We co- |

| uld send you some potatoes and other things had already |

| sent them to you, as we have |

| enough potatoes for the winter we will not run out of them |

| ---------------------------- [page break] ---------------------------- |

| and about what you say about influences (( )) |

| there have always been and there will always be. I have never |

| had them nor have I ever wanted them |

| but I have always done what I wanted |

| and saying no more over there |

| many regards from all your friends and to |

| Luis we have given a portrait and he has become |

| very happy Receive a strong hug from |

| your father and all your siblings and |

| send how ((you are to this address)) |

| Your father who loves you with all his heart and |

| he is |

| Juan Fernández |

| Hail and death to fascism’ |

Figure 7.

Letter from a father to his son at the war front.

The letter in (8) begins with the following salutation from a father to his son, who is at the war front:

| (9) |

| ‘Dear son. |

| I will be glad that upon receipt of this letter you |

| ’ll find yourself well in the company of your friends |

| we are well for the present’ |

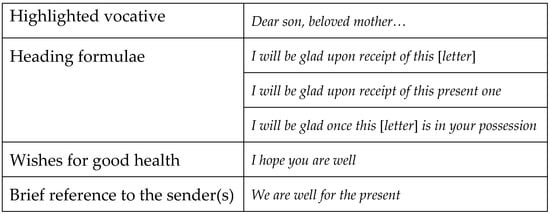

Such a beginning follows a scriptural pattern in which politeness is ritualized. First of all, a formal vocative is introduced (Dear son), often included—as in Figure 8—on a separate line. Next, a formula such as ‘I will be glad once you receive this letter’ leads the greetings, along with wishes for good health (you’ll find yourself well). Finally, the salutation usually closes with a very concise reference to the sender’s own health. Schematically, the beginning of the letter is outlined as follows:

Figure 8.

Scriptural pattern of the salutation.

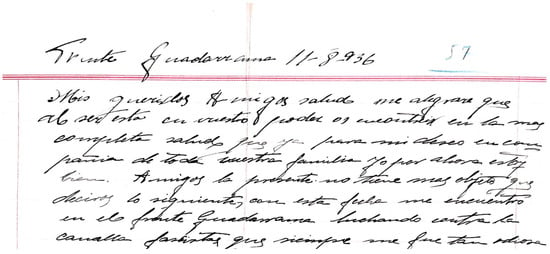

This pattern is also repeated in letters between equals, such as siblings, spouses, or friends. For instance, see the following letter (Figure 9):

| (10) |

| Frente Guadarrama 11-8-936 |

| Mis queridos Amigos salud me alegrare que |

| al ser esta en vuestro poder os encontreis en la mas |

| completa salud que ((ya)) para mi deseo en com- |

| pañia de toda vuestra familia Yo por ahora estoy |

| bien. Amigos la presente no tiene mas objeto que |

| deciros lo siguiente, con esta fecha me encuentro |

| en el frente Guadarrama luchamos contra la |

| canalla fascistas que siempre me fue tan odiosa |

| […] |

| ‘Guadarrama Front 11-8-936 |

| My dear Friends hail I will be glad that |

| once this is in your possession you find yourselves in the most |

| complete health which I ((already)) wish for myself in the com- |

| pany of all your family I am for now |

| well. Friends this letter has no other purpose than |

| to tell you the following, that as of this date I am |

| at the Guadarrama front we are fighting against the |

| fascist scum which has always been so hateful to me |

| […]’ |

Figure 9.

Salutation pattern (fragment of a letter).

Similar to (9), joy and wishes for good health are central topics in (10) (also frequently found in Italian popular correspondence; see Scivoletto, 2024, pp. 252–253). These topics define a set of acts that is consistently introduced by a formal vocative (Dear son, My dear Friends), reflecting a weak influence of orality. Such formulaic expressions were learned in elementary school, and their ritualized use implies some topics that recurrently appear in the letter. Hence, the salutation is circumscribed to a set of acts (SoA) that corresponds, in turn, to the move dedicated to greetings (M1).

Such a salutation move (M1), in fact, contrasts with the body of the letter (M2). See (11) and (12) for the segmentation of examples (9) and (10), respectively:

| (11) |

| M1[SoA1{#IAS{‘Dear son.}IAS |

| DSS{I will be glad that upon receipt of this letter you |

| ’ll find yourself well in the company of your friends}DSS# |

| #DSS{we are well for the present}DSS#}SoA1]M1 M2[SoA2{#IAS{son}IAS DSS{we received |

| your letter}DSS# #DSS{and through it we know that you are well |

| which is what we wish for}DSS##}SoA2 SoA3{#DSS{and you may know that |

| we have received a money order of 200 pesetas […]’ |

| (12) |

| M1[SoA1{#IAS{‘My dear Friends}IAS MAS{hail}MAS DSS{I will be glad that |

| once this is in your possession you find yourselves in the most |

| complete health}DSS SSS{which I ((already)) wish for myself in the com- |

| pany of all your family}SSS# # DSS{I am for now |

| well.}DSS#}SoA1]M1 M2[SoA2{#IAS{Friends}IAS DSS{this letter has no other purpose than |

| to tell you the following, that as of this date I am |

| at the Guadarrama front}DSS# #DSS{we are fighting against the |

| fascist scum which has always been so hateful to me […]’ |

In both (11) and (12), the second move (M2) begins with vocatives typical of orality (TAS{son}TAS, TAS{Friends}TAS); these vocatives are intersubjective adjacent subacts but differ from the formal salutation vocatives (M1), usually modified by an adjective (IAS{Dear son.}IAS, IAS{My dear Friends}IAS). Thus, the body of the letter is distinguished, even without graphical correspondence in paragraphs. Likewise, the body of the letter in (9) lacks punctuation or cohesive marks and is primarily structured through the conjunction y (‘and’). Similarly, in (10), only one period is used, right before the informal vocative Friends—marking the boundary between the more scriptural and the rather oral parts of the letter.

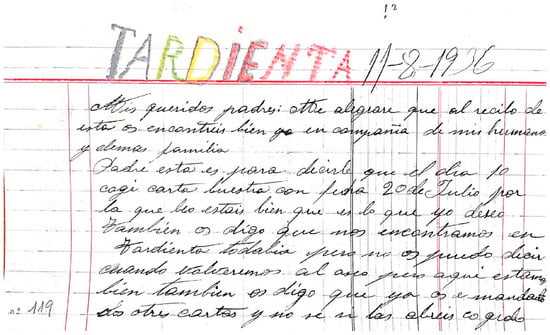

Finally, a key feature for identifying ritualized politeness in the salutation has been observed in the corpus. Spanish distinguishes two forms of address in pronouns and verb conjugation. This distinction reflects a formal difference and depends on the level of familiarity or respect: tú (‘you’) and vosotros (plural ‘you’) are used with close, same-aged people, while usted (singular) and ustedes (plural) show respect or distance. Due to the scriptural mold of the time, the salutation, when addressed to two or more people, used to be written in an unmarked way using vosotros. See Figure 10 and the transcription in (13) for an example, as follows:

| (13) |

| TARDIENTA 11-8-1936 |

| Mis queridos padres: Me alegrare que al recibo de |

| esta os encontreis bien yo en compañia de mis hermanos |

| y demas familia |

| Padre esta es para decirle que el dia 10 |

| cogi carta buestra con fecha 20 de Julio por |

| la que leo estais bien que es lo que yo deseo |

| Tambien os digo que nos encontramos en |

| Tardienta todavía pero no os puedo decir |

| cuando volveremos al (( )) pero aqui estamos |

| bien tambien os digo que ya os e mandado |

| dos otres cartas y no se si las abreis cogido […] |

| ‘TARDIENTA 11-8-1936 |

| My dear parents: I will be glad once you receive |

| this and find yourselves[= ‘tú’] well I’m along with my siblings |

| and the rest of the family |

| Father, this is to tell you[= ‘usted’] that on the 10th |

| I received your letter dated July 20th from |

| which I read that you are well which is what I wish for |

| I also tell you that we are in |

| Tardienta still but I cannot say |

| when we will return to (( )) but her we are |

| fine I also tell you that I have already sent you |

| two or-three letters and I do not know if you have received them […]’ |

Figure 10.

Diaphasic differences between salutation and body (front of the letter).

Notwithstanding the ritualized politeness of the salutation, in (13), the sender soldier switches to the marked form when addressing his parents in the body (M2) since the usted-like forms (esta es para decirle [a usted]) were the default polite form of address from sons to parents at the time (Molina Martos, 2021). See the segmentation in (14), as follows:

| (14) |

| M1[SoA1{#IAS{‘My dear parents:}IAS DSS{I will be glad once you receive |

| this and find yourselves[= ‘tú’] well}DSS# #DSS{I’m along with my siblings |

| and the rest of the family}DSS#}SoA1] M1 |

| M2[SoA2{#IAS{Father,}IAS DSS{this is to tell you[= ‘usted’] that on the 10th |

| I received your letter dated July 20th from |

| which I read that you are well which is what I wish for}DSS# |

| #SSS{I also tell you that we are in |

| Tardienta still}SSS DSS{but I cannot say |

| when we will return to (( ))}DSS# #DSS{but here we are |

| fine}DSS# #DSS{I also tell you that I have already sent you |

| two or-three letters and I do not know if you have received them}DSS# […]’ |

The use of usted-like forms coexists with the unmarked forms in the letter when the sender refers to all family members, even within the same sentence (leo que estáis bien, ‘I read you[=tú] are well’). This alternating use of address forms further reinforces the description of the body of the letter in terms of orality as a move that echoes conversation (M2), in opposition to the more scriptural tone that semiliterate writers maintain in the greetings move (M1). In short, Figure 8 is reframed into Figure 11:

Figure 11.

Scriptural vs. oral patterns of salutation.

This border between scriptural and oral moves, drawn by the salutation, is also observed when analyzing the procedural markers used by semiliterate people to (try to) ensure cohesion in the text.

4.2. Markers of Discursive Move

Semiliterate people’s letters lack the cohesive markers that are typical of formal written texts. Instead, they rely on procedural elements to structure the content into sets of acts and moves. Some of these elements include conversational markers that introduce the body of the letter (which, as explained in Section 4.1, tend to reproduce orality). For instance, returning to a fragment of the letter in Figure 3 (below Figure 12):

| (15) |

| M1[SoA1{#IAS{estimados Sobrinos}IAS MAS{Salut}MAS |

| DSS{Como lanuestra es buena |

| por la presente les deseamos}DSS# |

| #DSS{les digo que [h]emos Resibido |

| labuestra Conmucho gusto y alegría . de saber buenas |

| notisias Buestras}DSS#}SoA1]M1 M2[SoA2{#TAS{pues}TAS |

| DSS{Sabreys que a[h]ora ayudo a |

| pasar 8 o 10 dias a ((Zoralla))}DSS# |

| #DSS{buestros Primos Casimiro y […] |

| M1[SoA1{#IAS{‘Dear Nephews}IAS MAS{Hail}MAS |

| DSS{As our[health] is good |

| hereby we wish you [the same]}DSS# |

| #DSS{I tell you that we have Received |

| your[letter] withmuch pleasure and joy. of having heard good |

| news from You}DSS#}SoA1]M1 M2[SoA2{#TAS{well}TAS |

| DSS{You should know that now I help to |

| spend 8 or 10 days in ((Zoralla))}DSS# |

| DSS{your cousins Casimiro and […]’ |

Figure 12.

Fragment of a letter to a militiaman from his uncle.

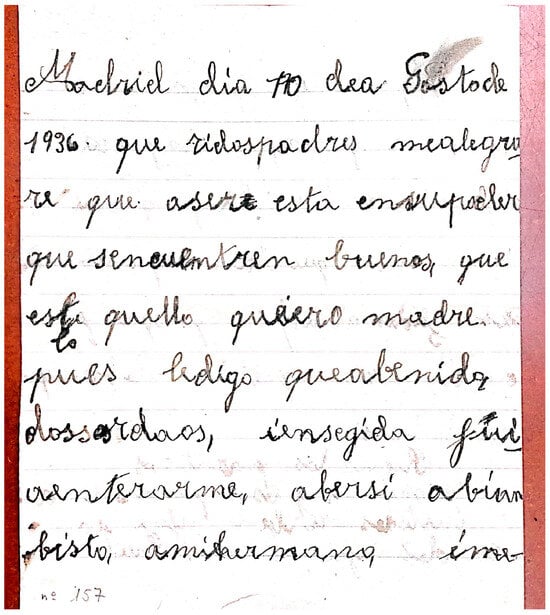

The marker pues (‘well’) in Figure 12 is the first element of the body of the letter (M2), signaling the switch from the first salutation move (M1). According to the segmentation in (15), such oral markers introduce a new move and frequently appear in combination with the prototypical vocative that starts the body of the letter. See Figure 13 and the segmented transcription in (16):

| (16) |

| Madrid dia 19((º)) dea Gostode |

| 1936. M1[SoA1{#IAS{que ridospadres}IAS DSS{mealegra- |

| re que aser((--)) esta ensupoder |

| que sencuentren buenos,}DSS SSS{que |

| es lo quello quiero}SSS#}SoA1]M1 M2[SoA2{#IAS{madre}IAS |

| TAS{pues}TAS DSS{le digo queabenido, |

| dossordaos,}DSS# #DSS{iemsegida fui- |

| aenterarme, abersi abían |

| visto, amishermano,}DSS# #DSS{ime- […] |

| ‘Madrid day 19((th)) of August |

| 1936. M1[SoA1{#IAS{dear parents}IAS DSS{I will-be- |

| glad once this is((--)) in-your-hands |

| that you-are well,}DSS SSS{which |

| is what-I wish}SSS#}SoA1]M1 M2[SoA2{#IAS{mother}IAS |

| TAS{well}TAS DSS{I tell you that have-arrived, |

| two-soldiers,}DSS# #DSS{and-immediately I went- |

| to-find-out if they had |

| seen, my siblings,}DSS# #DSS{and-I- […]’ |

Figure 13.

Fragment of a letter from a soldier to his mother.

Deepening in the oral nature of the body move (M2), the combination of the default vocative (IAS{mother}IAS) with pues (TAS{well}TAS) introducing a new topic runs parallel to that used in spoken language to start a new turn in conversation (Pons Bordería, 2018; Pons Bordería et al., 2023, pp. 56–58).

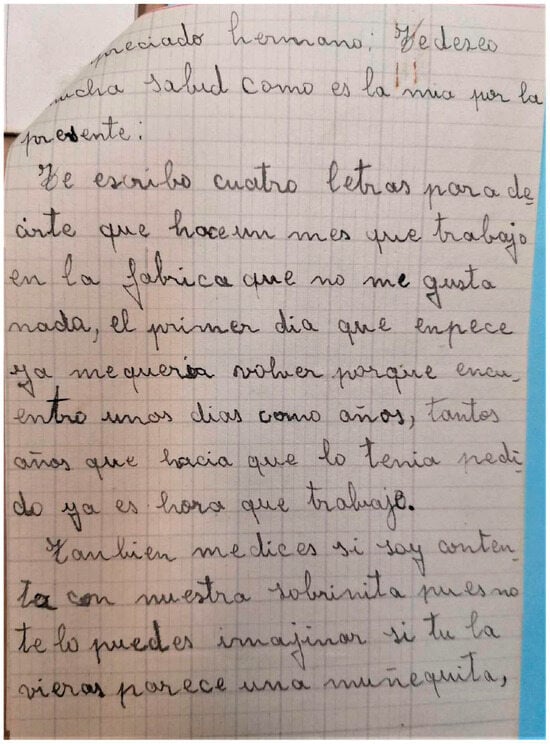

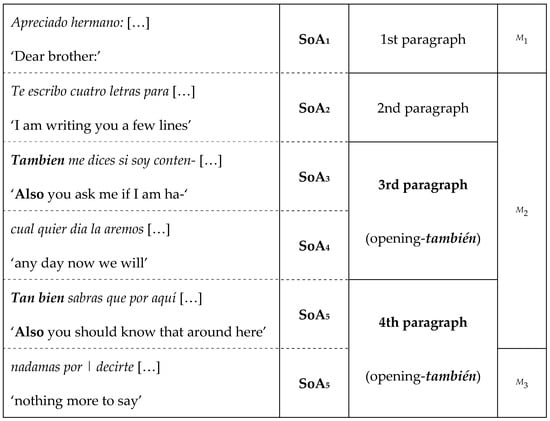

As a differentiated move from salutation, the body of the letter tends to begin with procedurally oral elements; nevertheless, this move can also be initiated by some ritualized formulae. For instance, see Figure 14 and its segmented transcription in (17):

| (17) |

| M1[SoA1{#IAS{Apreciado hermano:}IAS DSS{Te deseo |

| mucha salud como es la mía por la |

| presente:}DSS#}SoA1]M1 |

| M2[SoA2{#TAS{Te escribo cuatro letras para de- |

| cirte que}TAS DSS{hace un mes que trabajo |

| en la fabrica que no me gusta |

| nada}DSS# #DSS{el primer dia que emepece |

| ya me queria volver}DSS SSS{porque encu- |

| entro unos días como años,}SSS# #DSS{tantos |

| años que hacia que lo tenia pedi- |

| do ya es hora que trabaje.}DSS#}SoA2 |

| SoA3{#TAS{Tambien}TAS DSS{me dices si soy conten- |

| ta con nuestra sobrinita.}DSS# #TAS{pues}TAS DSS{no |

| te lo puedes imajinar}DSS# #DSS{si tu la |

| vieras parece una muñequita,}DSS# |

| SoA4{#DSS{cual quier dia la aremos [re-] |

| tratar y te mandaremos ((--)) |

| fotografía,}DSS# # DSS{cuando nos vuel[vas a] |

| escribir nos lo diras osi te gusta- |

| ria,}DSS# # DSS{las fotografías que nos man- |

| dastes ya emos dado una a la Tere- |

| sa que le gusto mucho tanto ella |

| como el Estevan.}DSS#}SoA4 |

| SoA5{#TAS{Tan bien}TAS DSS{sabras que por aquí |

| hace mucho frio.}DSS#}SoA5 M2[SoA6{#TAS{nadamas por |

| decirte}TAS# #DSS{cual quier dia te escri- |

| bire una carta yo sola.}DSS#}SoA6]M2 |

| Tu hermana que no te |

| olvida nunca. |

| Julia Fernandez Verges |

| M1[SoA1{#IAS{‘Dear brother:}IAS DSS{ I wish you |

| good health as is mine in |

| this letter:}DSS#}SoA1]M1 |

| M2[SoA2{#TAS{I am writing you a few lines to |

| tell you that}TAS DSS{for a month I have been working |

| in the factory and I do not like it |

| at all}DSS# #DSS{the first day I started |

| I already wanted to leave}DSS SSS{because I fi- |

| nd the days as long as years,}SSS# #DSS{so many |

| years I had been waiting for this job |

| and now it is time to work}DSS#}SoA2 |

| SoA3{#TAS{Also}TAS DSS{you ask me if I am ha- |

| ppy with our little niece.}DSS# #TAS{so}TAS DSS{you cannot |

| imagine}DSS# #DSS{if you saw her |

| she looks like a little doll,}DSS# |

| SoA4{#DSS{any day now we will have her [por-] |

| trait taken and we will send you ((--)) |

| a photograph,}DSS# # DSS{when you [again] |

| write us let us know if you would |

| like it,}DSS# # DSS{the photographs you sent |

| us we have already given one to Tere- |

| sa who liked it very much both she |

| and Estevan.}DSS#}SoA4 |

| SoA5{#TAS{Also}TAS DSS{you should know that around here |

| it is very cold.}DSS#}SoA5 M3[SoA6{#TAS{nothing more to |

| say}TAS# #DSS{any day now I will write |

| you a letter all by myself.}DSS#}SoA6]M3 |

| Your sister who never |

| forgets you |

| Julia Fernandez Verges |

Figure 14.

Letter from a sister to her soldier brother.

In (17), the body of the letter is introduced by a formula such as ‘I am writing you four/a couple of/a few lines to tell you that.’ This formula can indicate a writer’s higher degree of education; however, as routinized in the scriptural mold, it can also—echoing the segmentation in (7)—combine with default oral vocatives like Primo (‘Cousin’):

| (7) |

| M2[SoA2{#IAS{Primo}IAS TAS{esta es para decirte que}TAS DSS{ya sabiamos tu paradero antes |

| de escribir a tu tia}DSS SSS{por unas declaraciones hechas por ti que venian en la |

| Solidaridad Obrera de Barcelona}DSS# #DSS{yo estuve 14 dias en el Frente de |

| Extremadura}SSS# #DSS{yo he venido enfermo y llevo aquí 15 dias hasta |

| que me mejore}DSS# #DSS{no he soltado las armas desde que empezó |

| el movimiento faccioso no ((siendo)) estos 15 días que llevo |

| sin hacer servicio.}DSS# SoA2]M2 |

The body, as the most extensive move (M2) of a letter, is characterized by the blending of both scriptural (e.g., routinized framing devices) and oral elements, such as vocatives or the use of TAS{pues}TAS (‘so’) serving a formulative function.

This blending is particularly evident in some cohesive devices that are neither strictly oral nor part of written conventions. In other words, the letter writer draws on elements from their background as a semiliterate individual and uses them to structure the text. A clear example is the adverb también (‘also’) in (17); in these cases, también introduces a new set of acts, and the writer aligns it with a new paragraph (Figure 15):

Figure 15.

Text-structuring también.

As shown in Figure 15, también starting a new paragraph does not necessarily have scope over all sets of acts included in such a paragraph (nor over a move); that said, text-structuring también, in my view, denotes the sender’s deliberate attempt to distribute information across topic blocks.

Finally, two main concluding markers introducing the farewells have been identified. Although not as rigid or even—in Zieliński’s (2019a, p. 325) words—“abrupt” as the discourse traditions present within the salutation, the farewell, as the final part of the letter,10 constitutes a move that follows certain scriptural conventions; for example, see in (17)—last paragraph, third move (M3)—the text-closing marker TAS{nadamas por decirte}TAS (‘nothing more to say’). This formula is repeated in several letters with minor variations, like Nada mas te digo por la presente (‘I don’t tell you anything more in this letter’) in (7) or y no diciendo te mas (‘and saying no more’) in (8).

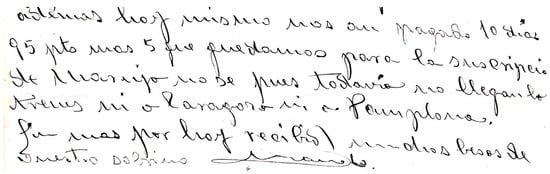

The second concluding marker is sin más (similar to English ‘that’s all’), as observed in Figure 16 and example (18):11

| (18) |

| […] |

| ademas hoy mismo nos [h]an pagado 10 dias |

| 95 pts mas 5 que quedamos para la suscripción |

| de ((Maruja)) no se pues todavía no llegan lo[s] |

| trenes ni a Zaragoza ni a Pamplona.]M2 |

| M3[#TAS{Sin mas}TAS DSS{por hoy recibid muchos besos de |

| vuestro sobrino}DSS#]M3 Manolo |

| […] |

| ‘moreover today we [h]ave been paid for 10 days |

| 95 pts12 plus 5 that we set aside for the subscription |

| about ((Maruja)) I don’t know anything since trains still do not reach |

| Zaragoza or Pamplona.]M2 |

| M3[#TAS{That’s all}TAS DSS{ for today you all receive many kisses from |

| your nephew}DSS#]M3 Manolo’ |

Figure 16.

Letter fragment (farewell): ‘sin más + imperative.’

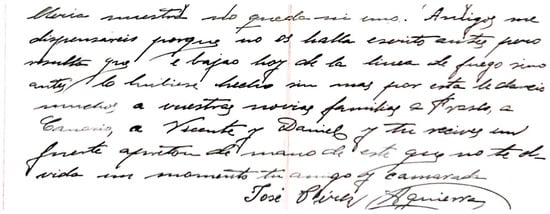

The marker sin más serves to introduce the farewell move; unlike formulae such as ‘nothing more to say in this letter,’ sin más preceds in (18) an imperative verb (recibid, ‘you all receive’). This combination is relevant since the marker sin más is always paired with a sentence that prompts the recipient to send greetings to other relatives or friends (Figure 17) or emphasizes additional information or requests (Figure 18):

| (19) |

| […] |

| [arti-]lleria nuestra no queda ni una. Amigos me |

| dispensareis porque no os halla escrito antes pero |

| resulta que e bajao hoy de la linea de fuego sino |

| antes lo hubiese hecho]M2 M3[#TAS{sin mas}TAS DSS{por esta le daréis |

| muchos a vuestras novias familias a ((Fresco)), a |

| Canario, a Vicente y Daniel}DSS# #DSS{y tu recives un |

| fuerte apretón de manos de este que no ol- |

| vida un momento}DSS IAS{tu amigo y camarada}IAS#]M3 |

| José Pérez Aguirre |

| […] |

| ‘[arti-]llery ourse there is not even one left. Friends you will |

| forgive me for not having written before but |

| it turns out that I came down today from the front lines if not |

| I would have done it earlier]M2 M3[#TAS{That’s all}TAS DSS{you shall give |

| many [greetings] to your girlfriends families to ((Fresco)), to |

| Canario, to Vicente and Daniel}DSS# #DSS{and you receive a |

| strong handshake from this one who does not for- |

| get a moment}DSS IAS{ your friend and comrade’}IAS#]M3 |

| José Pérez Aguirre |

Figure 17.

Letter fragment (farewell): ‘sin más + further greetings.’

Figure 18.

Letter fragment (farewell): ‘sin más + further request.’

| (20) |

| […] |

| “Frente Popular” asi es que si no |

| ha tenido la suerte poder escapar por |

| algún sitio no sabremo que habrá |

| sido de él además no podemos escribir- |

| le desde aquí porque están cortas las |

| comunicaciones. Así que ver si tu |

| puedes tener alguna noticia de él.]M2 M3[#TAS{Sin |

| más}TAS DSS{que nos escribas pronto diciendo |

| que es de vosotros}DSS#]M3 |

| Juan y Eulalia |

| […] |

| ‘“Popular Front” so if he has not |

| had the luck to escape through |

| some way we will not know what has |

| happened to him moreover we cannot write |

| to him from here because they cut off communications |

| so see if you can get any news from him.]M2 M3[#TAS{That’s |

| all}TAS DSS{please write to us soon saying |

| what’s up with you guys}DSS#]M3 |

| Juan and Eulalia’ |

Hence, the construction ‘sin más + directive speech act’ reveals a semiscriptural way to vary the conventions associated with farewells when sudden information has to be added before the letter closes—as recently highlighted by Albitre Lamata (2024) in her study of 19th-century Río de la Plata private letters, this use of directive speech acts is characteristic of contexts of maximal closeness, though already constructionalized in our 20th-century corpus.

In conclusion, segmenting letters into discourse units uncovers procedural devices specialized in certain parts of the letter. These devices are not only markers that reproduce orality (such as vocatives, formulative markers, and directive speech acts) but patterns of low-degree scripturality (such as text-structuring también and concluding constructions).

5. Conclusions

This study has documented around 350 handwritten letters from semiliterate people in early 20th-century Spain. Documentation, cataloging, and corpus segmentation using the Val.Es.Co. model allowed for the observation of different pragmatic phenomena related to politeness and procedural devices for discourse structuring; see them at a glace in Figure 19.13

Figure 19.

Letter components.

Regardless of the soldiers’ or their relatives’ formal education, the written orality in these letters is inseparable from the scriptural conventions. As the initial discursive move (M1), the ritualized formulae and politeness forms in the salutation contrast with those in the body of the letter (M2), which is more strongly influenced by orality. At the same time, the body of the letter incorporates cohesive elements characteristic of low-level scripturality. This semiscriptural flavor is also evident in the farewells, i.e., the final move (M3).

My analysis, then, identifies recurring patterns distributed across these three moves, outlining a composition framework of how the most modest Spaniards of the time expressed themselves in writing during a challenging period for the nation. As a final point, a model of segmentation into discourse units serves as a complementary tool for studies on epistolography, thereby enhancing philological interpretations of written orality.

Funding

This work is part of the two following research projects: Hacia la caracterización diacrónica del siglo XX (DIA20) (CIPROM/2021/038, Generalitat Valenciana) and Aportaciones para una caracterización diacrónica del siglo XX (MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033/FEDER—Una manera de hacer Europa).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Acknowledgments

I truly thank the two anonymous reviewers for their suggestions for improvement and bibliographical recommendations. I am also grateful to Margarita Borreguero Zuloaga for her assistance in accessing some references on Italian philology and to Salvador Pons Bordería and Shima Salameh Jiménez, who read a previous version of this paper. I also thank Giulio Scivoletto, whose book Una guerra con la lingua has become a constant reference for me. Finally, I am indebted to the archivists at the Civil War Archive in Salamanca for their patience with this linguist with philological pretensions. All remaining errors are my own.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DSS | Director Substantive Subact |

| SSS | Subordinated Substantive Subact |

| TAS | Textual–Structuring Adjacent Subact |

| MAS | Modal Adjacent Subact |

| IAS | Intersubjective Adjacent Subact |

| SoA1, SoA2… SoAn | Set(s) of Acts |

| M1, M2… Mn | Discursive Move(s) |

Notes

| 1 | Regarding the search for documentation in the archives, see Section 3. |

| 2 | In these letters, there are other written marks related to the documentation process of the archive where they were located. In this work, I will not consider these marks, as they do not constitute linguistic information (but archival or historiographical information). |

| 3 | My translation. |

| 4 | See also Tróccoli’s (2012) analysis of Uruguayan Spanish oral traits in 19th-century private letters. |

| 5 | My translation. |

| 6 | My translation. |

| 7 | In my transcriptions, brackets [ ] indicate reconstructed text; double parentheses (( )) mark uncertain transcription; ((--)) denotes cross-out; and […] denotes omitted content. Page breaks will be expressly indicated. |

| 8 | My translation. |

| 9 | Former currency of Spain. |

| 10 | See the studies by Vila Carneiro and Faya Cerqueiro (2016, 2017) on the importance of farewell formulae in the closing sections of letters in Golden Age Spanish (17th-century Imperial Period). |

| 11 | The segmentation of (18), (19), and (20) omits the unit set of acts, as I am dealing with letter fragments in these examples. |

| 12 | Abbreviation for pesetas (former currency of Spain). |

| 13 | As one anonymous reviewer has pointed out, it is somewhat vague to include unplanned writing as a feature of “default politeness.” However, as I mentioned at the beginning of Section 4, I include it here operationally, in opposition to the scriptural norms of “ritualized politeness.” I appreciate this criticism and hope to provide a more refined solution in future research. |

References

- Albitre Lamata, P. (2020). El género epistolar y la (des)cortesía histórica. Estado de la cuestión y reflexión crítica. Textos en Proceso, 6(1), 118–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albitre Lamata, P. (2024). Pragmática histórica del español rioplatense. Actos directivos y estrategias de mitigación en correspondencia femenina del siglo XIX. Studia Linguistica Romanica 12, 187–212. [Google Scholar]

- Albitre Lamata, P., & Martín Cuadrado, C. (2024). Aproximación a discurso epistolar nicaragüense. Mariano Barreto: Las cartas privadas dirigidas a Casanovas, Paniagua Prado y Guzmán. Boletín de la Academia Peruana de la Lengua 76, 433–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, B. (2016). Escribir lo dicho. Reflejos de la lengua hablada y de los intercambios comunicativos en un corpus documental del siglo XIX. Boletín de Literatura Oral, 6, 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Antón, J. (2019). La teoría de la carta familiar (siglos XVI-XIX). Revista de Historia Moderna, 37, 95–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azofra Sierra, M. E. (2023). El epistolario de Diego de Valera: Lengua y persuasión. RILCE: Revista de Filología Hispánica, 39(1), 12–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badia, S., & Espinosa-Guerri, G. (2024). CONVERSATIONS. Un software para el análisis semiautomático de la estructura conversacional. RLA. Revista de Lingüística Teórica y Aplicada, 62(1), 73–100. [Google Scholar]

- Bello Hernández, I. (2020). La cortesía en Canarias a finales del siglo XVIII y principios del XIX. Saludos y despedidas en un corpus de cartas privadas. Estudios de Lingüística del Español, 42, 39–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello Hernández, I. (2022). Las formas de tratamiento pronominales y nominales en cartas familiares canarias (siglo XVIII). In J. Herrero Ruiz de Loizaga, M. E. Azofra Sierra, & R. González Pérez (Eds.), La configuración histórica del discurso: Nuevas perspectivas en los procesos de gramaticalización, lexicalización y pragmatización (pp. 79–108). Iberoamericana Vervuert. [Google Scholar]

- Beltrán Almería, L. (1996). Las estéticas de los géneros epistolares. Anuario de la Sociedad Española de Literatura General y Comparada, 10, 239–246. [Google Scholar]

- Biber, D. (2012). Register as a predictor of linguistic variation. Corpus Linguistic and Linguistic Theory, 8, 9–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biber, D., & Gray, B. (2013). Being specific about historical change. The influence of sub-register. Journal of English Linguistics, 41(2), 104–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borreguero Zuloaga, M. (2006). La crónica de sucesos (s. XVII–s. XIX), evolución y desarrollo de la organización informativa textual. In J. L. Girón Alconchel, & J. J. de Bustos Tovar (Eds.), Actas del VI congreso internacional de historia de la lengua Española (pp. 2653–2668). Arco Libros. [Google Scholar]

- Borreguero Zuloaga, M. (2023). Discourse traditions and models of discourse segmentation. In E. Winter-Froemel, & A. Octavio de Toledo (Eds.), Manual of discourse traditions in Romance (pp. 333–350). De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Borreguero Zuloaga, M. (2024). La Epístola a Suero de Quiñones de Enrique de Villena. Articulación informativa y macroestructura textual en la transición del ars dictaminis a la epístola humanística. Círculo de Lingüística Aplicada a la Comunicación, 97, 59–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo, D., & Briz, A. (2004). Pragmática sociocultural: Estudios sobre el discurso de cortesía en español. Ariel. [Google Scholar]

- Briz Gómez, A. (1998). El español coloquial en la conversación. Ariel. [Google Scholar]

- Briz Gómez, A. (2010). El registro como centro de la variedad situacional. Esbozo de la propuesta del grupo Val.Es.Co. sobre las variedades diafásicas. In I. Fonte, & L. Rodríguez (Eds.), Perspectivas dialógicas en estudios del lenguaje (pp. 21–56). UANL. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, P., & Levinson, S. C. (1987). Politeness: Some universals in language usage. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cabanes Pérez, S. (2020). La quinésica en la identificación de intervenciones y turnos. Estudios Interlingüísticos, 8, 33–49. [Google Scholar]

- Cano Aguilar, R. (1996). Lenguaje ‘espontáneo’ y retórica epistolar en cartas de emigrantes españoles a Indias. In T. Kotschi, W. Oesterreicher, & K. Zimmermann (Eds.), El español hablado y la cultura oral en España e Hispanoamérica (pp. 375–404). Iberoamericana-Vervuert. [Google Scholar]

- Cantoni, P. (2018). Ci lece questo scrito mi debe compatire perche non son una per sona indelicente. Riflessioni sulla lingua ‘dal basso’ nella didattica dell’italiano. ELLE, 7, 135–151. [Google Scholar]

- Cantoni, P. (2019). L’uso della punteggiatura nei registri dei maestri elementari di primo Novecento. In A. Ferrari, L. Lala, F. Longo, F. Pecorari, & R. Stojmenova (Eds.), Punteggiatura, sintassi, testualità nella varietà dei testi italiani contemporanei (pp. 209–223). Franco Cesati Editore. [Google Scholar]

- Cantoni, P., & Fresu, R. (2020). Altri modelli per l’insegnamento della variazione: Riflessioni teoriche e proposte didattiche. Italiano Lingua Due, 12(1), 991–1006. [Google Scholar]

- Cuenca Ordinyana, M.-J. (2014). The use of demonstratives and context activation in Catalan parliamentary debate. Discourse Studies, 16(6), 729–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberenz, R. (1991). Castellano antiguo y español moderno: Reflexiones sobre la periodización en la historia de la lengua. Revista De Filología Española, 71(1/2), 79–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estellés, M. (2009). The importance of paradigms in grammaticalization. The Spanish discourse markers por cierto and a propósito. Studies in Pragmatics, 7, 123–146. [Google Scholar]

- Estellés, M. (2020). The evolution of parliamentary debates in light of the evolution of evidentials. Corpus Pragmatics, 4, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández Alcaide, M. (2009). Práctica privada del arte epistolar en el siglo XVI. In M. V. Camacho-Taboada, J. J. Rodríguez Toro, & J. Santana Marrero (Coords.), Estudios de lengua española: Descripción, variación y uso. Homenaje a Humberto López Morales (pp. 261–284). Iberoamericana Vervuert. [Google Scholar]

- Fresu, R. (2016). Questa guerra non è mica la guerra mia. Scritture, contesti, linguaggi durante la grande guerra. Il Cubo. [Google Scholar]

- Garrido Martín, B. (2021). Cartas de mujeres y recursos para la intensificación y la expresión afectiva en un corpus del s. XVIII. Hipogrifo, 9(1), 1027–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibelli, A. (2022). Scritture popolari e Grande Guerra. Una rivoluzione copernicana. Revista de Historiografía, 37, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girón Alconchel, J. L. (2016). La segmentación lingüística del discurso en la prosa de la segunda mitad del siglo XVII. In A. López-Serena, A. Narbona Jiménez, & S. del Rey Quesada (Eds.), El español a través de los tiempos. Estudios ofrecidos a Rafael Cano Aguilar (Vol. 2, pp. 933–955). Universidad de Sevilla. [Google Scholar]

- Girón Alconchel, J. L. (2018). La creación de gramática y de texto. Del enunciado a la unidad discursiva en El Quijote. In J. L. Girón Alconchel, F. J. Herrero Ruiz de Loizaga, & D. M. Sáez Rivera (Eds.), Procesos de textualización y gramaticalización en la historia del español (pp. 311–344). Iberoamericana. [Google Scholar]

- Guillén, C. (1991). Al borde de la literariedad: Literatura y epistolaridad. Tropelías, 2, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haverkate, H. (1994). La cortesía verbal: Estudio pragmalingüístico. Gredos. [Google Scholar]

- Jacob, D., & Kabatek, J. (2001). Introducción. Lengua, texto y cambio lingüístico en la Edad Media iberorrománica. In D. Jacob, & J. Kabatek (Coords.), Lengua medieval y tradiciones discursivas en la Península Ibérica. Descripción gramatical-pragmática histórica-metodología (pp. 1–12). Vervuert/Iberoamericana. [Google Scholar]

- Kabatek, J. (2005). Tradiciones discursivas y cambio lingüístico. Lexis: Revista de Lingüística y Literatura, 29(2), 151–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabatek, J. (2011). Diskurstraditionen und genres. In S. Dessì-Schmid, U. Detges, P. Gévaudan, W. Mihatsch, & R. Waltereit (Eds.), Rahmen des Sprechens. Beiträge zu valenztheorie, varietätenlinguistik, kreolistik, kognitiver und historischer semantik. Peter koch zum 60. geburtstag (pp. 89–100). Narr. [Google Scholar]

- Kabatek, J. (2021). Eugenio Coseriu on immediacy, distance and discourse traditions. In K. Willems, & C. Munteanu (Eds.), Eugenio Coseriu. Past, present and future (pp. 227–244). De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Koch, P. (1997). Diskurstraditionen. Zu ihrem sprachtheoretischen Status und ihrer Dynamik. In B. Frank, T. Haye, & D. Tophinke (Eds.), Gattungen mittelalterlicher schriftlichkeit (pp. 43–79). Narr. [Google Scholar]

- Koch, P., & Oesterreicher, W. (1990). Gesprochene Sprache in der Romania: Französisch, Italienisch, Spanisch. Niemeyer. [Google Scholar]

- Lapesa, R. (1977). Historia de la lengua española. Gredos. [Google Scholar]

- Llopis, A., & Jansegers, M. (2024). Del rollo como sustantivo comodín contracultural al rollo aproximador en el español coloquial actual. Spanish in Context, 21(1), 159–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Izquierdo, M., & Taillot, A. (2023). Epistolatrías: Mutaciones contemporáneas y nuevos enfoques de estudio de la carta. Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- López-Serena, A. (2007). La importancia de la cadena variacional en la superación de la concepción de la modalidad coloquial como registro heterogéneo. Revista Española de Lingüística, 37(1), 337–370. [Google Scholar]

- López-Serena, A. (2021). El hablar y lo oral. In O. Loureda, & A. Schrott (Eds.), Manual de lingüística del hablar (pp. 243–260). De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- López-Serena, A., & Sáez Rivera, D. M. (2018). Procedimientos de mímesis de la oralidad en el teatro español del siglo XVIII. Estudios Humanísticos: Filología, 40, 235–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melis, C., Flores, M., & Borgard, S. (2003). La historia del español. Propuesta de un tercer período evolutivo. Nueva Revista de Filología Hispánica, 51, 1–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina Martos, I. (2021). Cambio lingüístico y transformación social: Formas y fórmulas de tratamiento en España (1860–1940). RILI. Revista Internacional de Lingüística Iberoamericana, 38, 173–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Octavio de Toledo, Á. (2002). ¿Un viaje de ida y vuelta? La gramaticalización de vaya como marcador y cuantificador. Anuari de Filologia, 12, 47–72. [Google Scholar]

- Octavio de Toledo, Á. (2018). ¿Tradiciones discursivas o tradicionalidad? ¿Gramaticalización o sintactización? Difusión y declive de las construcciones modales con infinitivo antepuesto. In J. L. Girón Alconchel, F. J. Herrero Ruiz de Loizaga, & D. M. Sáez Rivera (Eds.), Procesos de textualización y gramaticalización en la historia del español (pp. 79–134). Vervuert/Iberoamericana. [Google Scholar]

- Octavio de Toledo, Á. (2023). Rasgos a la carta: Fenómenos dialectales y marcas de lengua elaborada en las Letras de Hernando del Pulgar. Rilce. Revista De Filología Hispánica, 39(1), 70–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo Llibrer, A. (2023). Sobre la lexicalización ‘no llega’ como forma aproximativa. Études Romanes de Brno, 44(2), 249–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]