Abstract

Of the few studies that have investigated the linguistic development of heritage speakers (HSs) in the study abroad (SA) context, none have utilized on-line experiments, in spite of these tasks’ clear methodological benefits. In this study, therefore, we test HSs’ on-line sensitivity to lexically selected mood morphology in Spanish. Ten adult HSs completed a self-paced reading task at the beginning and end of a fifteen-week-long SA program in Spain. The task assessed both (a) whether HSs were sensitive to mood incongruencies (e.g., by slowing down after ungrammatical verbs) and (b) whether that (in)sensitivity was different with regular vs. irregular verbs. It was hypothesized that participants would be more sensitive to mood with irregular verbs and that their mood sensitivity would increase over the course of the semester abroad, but these hypotheses were only partially supported. Although HSs developed sensitivity to mood incongruencies with regular verbs over the course of the semester abroad, they showed the reverse pattern with irregular verbs, demonstrating sensitivity at Session 1 but not Session 2. Nonetheless, because participants’ reading times decreased sharply over the semester—and without any concomitant decrease in comprehension accuracy—we argue that SA immersion likely does facilitate morphosyntactic processing in the HL.

1. Introduction

In memoirs written by heritage speakers (HSs), a common plot point is the return to the linguistic/ancestral homeland, an immersive pilgrimage that can shake the author’s sense of self and also reawaken seemingly dormant heritage language (HL) competence. As qualitative evidence of this pattern, consider the cases of two heritage bilingual authors, both of whom describe the initial difficulty of finding their HL voice during a return to the linguistic/ancestral homeland, as well as the rapid rediscovery of that voice over the course of their re-immersion.

Supreme Court justice Sonia Sotomayor, in her memoir My Beloved World (2013), depicts a childhood return to Spanish-speaking Puerto Rico as follows. While at first, “people would laugh” (Sotomayor, 2013, p. 34) because her second-generation heritage Spanish was “clumsy,” within days she claims that she could “hear [her]self improving.” Psycholinguist Julie Sedivy, a heritage speaker of Czech, offers a similar account in her (2021) book, Memory Speaks. As an adult, Sedivy travels back to the Czech Republic and experiences a similar transformation. At the beginning of her trip back, Sedivy reports making “grammar mistakes that prompted a four-year old to snicker” (Sedivy, 2021, p. 223), perhaps due to the difficulty of Czech’s case morphology system. Not long after, however, she notes that “the complicated inflections of Czech nouns…began to assemble themselves into somewhat orderly rows in [her] mind” (p. 223), a shift that points to immersion as a key factor in unlocking previously acquired—but perhaps temporarily inaccessible—HL knowledge.

While narrative accounts such as these abound in bilingual memoirs, suggesting that HSs might experience linguistic re-awakening in immersive contexts, the quantitative evidence for such shifts remains surprisingly scant. The goal of the present paper, therefore, is to assess whether HSs in an immersive, study abroad (SA) context develop heightened sensitivity to HL grammatical properties—in this case, subjunctive mood morphology in Spanish, a property that has received much attention in previous studies. By investigating HSs’ changing grammatical sensitivity over the course of a semester in Spain, the present study adds to the growing body of research on HL processing and, furthermore, sheds new light on the nature of variability in heritage grammars more generally.

1.1. Heritage Language Development in Study Abroad Contexts

Although HL researchers have begun to show more interest in the experiences of HSs who travel to a linguistic/ancestral homeland (e.g., Escalante et al., 2021), very few studies on this topic track HSs’ linguistic development over time, as noted in a number of recent papers (e.g., Escalante et al., 2021; Marqués-Pascual, 2021; Shively, 2016). Consequently, little is known about how linguistic (re)immersion in the SA context might impact HSs’ grammatical systems. When HSs take part in a SA program, do they eventually find their HL footing, as in the accounts of Sotomayor and Sedivy, or do their initial HL hiccups persist throughout the course of their immersive experience?

Of the four studies, to our knowledge, which have addressed similar questions, two have focused on apparent gains in global HL proficiency. Davidson and Lekic (2013) tested ten HSs of Russian in an intensive, nine-month SA program in Russia and found that participants significantly improved their scores on the Test of Russian as a Foreign Language from the beginning to the end of the program. Interestingly, participants’ scores increased more in reading than in the other three language modalities. Pozzi and Reznicek-Parrado (2021) used the VERSANT proficiency assessment to measure the linguistic growth of three Spanish HSs at the beginning and end of a semester-long SA program in Argentina. Two of the three participants scored higher at the end of the semester, suggesting development in their HL knowledge, while the third HS scored very highly across both sessions—but slightly lower at Session 2.

The other two studies of HSs’ grammatical development over the course of a semester abroad focused on growth in participants’ writing skills. In each study, participants responded to short prompts at the beginning and end of a semester abroad in Spain. In the first of these studies, Marqués-Pascual (2021) reports evidence of improvement in HSs’ number of words produced, written fluency and written complexity—but not grammatical accuracy. Nonetheless, because the author does not explain her method for operationalizing accuracy, a construct that can be particularly thorny in heritage bilingualism research, this finding should be interpreted with great caution. In a second analysis of the same sample, Marqués-Pascual and Checa-García (2023) reported that HSs increased their lexical density over the course of a semester abroad but not their lexical diversity or sophistication, suggesting that SA does not necessarily trigger growth in all areas of the HL.

In summary, the few studies of HL development in the SA context track linguistic growth either with (a) broad, global proficiency measures or (b) detailed assessments of very short writing samples. In spite of their clear contributions to our understanding of heritage bilingualism, though, none of these studies illuminate HSs’ development with specific grammatical properties of their HL grammar, such as subjunctive mood morphology in Spanish. Furthermore, as Jegerski (2018, p. 226) points out, off-line methods—such as those employed in the studies above—can sometimes “underestimate heritage speakers’ knowledge,” thereby making it harder to detect shifts in their HL skill over time. To address these limitations in the previous research, the present study examines a specific HL property—lexically selected mood morphology in Spanish—and tests it via self-paced reading (SPR), an on-line methodology that offers more direct insight into HSs’ unconscious, moment-to-moment processing of the HL.

1.2. Lexically Selected Subjunctive Mood and Its Acquisition by Heritage Speakers

Subjunctive mood morphology refers to a set of morphological inflections used to mark modality in Spanish (Bosque, 2012), as well as many other languages (e.g., Bybee et al., 1994). Although subjunctive mood inflections can be triggered in a number of different ways, we focus here on lexically selected subjunctive mood, that is, subjunctive mood whose presence is prompted by a preceding lexical item, typically a matrix verb.

| (1) | Sara | quiere | que | sus hijos | reciban/*reciben | una educación | bilingüe |

| Sara | want-3PS | that | her kids | receive-SUBJ/*IND | a bilingual | education | |

| Sara wants her kids to get a bilingual education | |||||||

| (2) | Alex | pide | que | sus hijos | le digan/*dicen la | historia | en francés |

| Alex | ask -3PS | that | his kids | him tell-SUBJ/*IND | the story | in French | |

| Alex asks his kids to tell him the story in French | |||||||

In (1) and (2), the trigger verbs querer (‘want’) and pedir (‘ask for’) require subjunctive mood morphology on the subsequent dependent clause verbs recibir (‘receive’) and decir (‘tell’), respectively. Unlike in the case of contextually selected mood, where subjunctive and indicative inflections can both be possible in the same context—each with a different meaning—the indicative mood forms in (1) and (2) are considered “ungrammatical” and do not convey an alternative interpretation of the sentence.

Mastering lexically selected subjunctive mood in Spanish requires learning both the matrix verbs that trigger the subjunctive (e.g., querer, pedir and others: See Section 2.3), as well as the specific subjunctive mood variants of subordinate verbs themselves, which can be categorized in terms of regularity. For regular verbs, such as (1), the subjunctive mood inflection is marked exclusively by a shift in the verb’s thematic vowel, in this case -e- to -a-. For irregular verbs, on the other hand, the subjunctive mood inflection is marked by both a vowel shift, as well as a change in the verbal root, e.g., di[s] to di[g] in (2).

While Spanish-dominant speakers (e.g., monolinguals or first-generation immigrants from Spanish-speaking countries) appear to exhibit categorical knowledge of lexically selected subjunctive mood across all verb types (e.g., Dracos et al., 2019; Giancaspro, 2017; Giancaspro et al., 2022; Perez-Cortes, 2023; Thane, 2025; Viner, 2016; inter alia), HSs’ knowledge of this property is both variable and significantly shaped by lexical-level characteristics such as morphological regularity. Dracos and Requena (2023) present evidence that child HSs’ knowledge of lexically selected mood is both systematic and variable. Although the HSs in their study produced far more subjunctive mood in volitional clauses following querer than in a control condition with saber (‘know’), suggesting that they clearly distinguish between subjunctive and indicative mood, the HSs’ use of subjunctive in volitional clauses was still highly variable (57.5%). Viner (2016) analyzed a corpus of Spanish in New York and found that adult HSs also exhibit variability in their production of subjunctive mood in lexically selected contexts, which he refers to as “obligatory”. Other recent studies have reported similar variability with subjunctive mood and attributed it, at least in part, to morphological regularity. Giancaspro et al. (2022) tested adult HSs’ oral production of lexically selected subjunctive with querer, finding that HSs’ knowledge of mood is both systematic and variable. Although HSs were sensitive to mood with all types of verbs, their likelihood of producing the subjunctive was much higher with irregular verbs than regular verbs, a finding that the authors attribute to differences in how irregular verbs are stored in and retrieved from memory.1

Of most direct relevance to the present investigation are two recent studies of how HSs process mood morphology in Spanish. López-Beltrán and Dussias (2024) used pupillometry to assess adult HSs’ sensitivity to mood with what they call non-variable governors, that is, matrix verbs that obligatorily select for subjunctive mood. The results of the study indicated that HSs processed mood violations, as evidenced by their greater pupil dilation with ungrammatical indicative verbs than grammatical subjunctive verbs. Furthermore, as in the off-line studies reviewed above, HSs’ ability to differentiate between subjunctive and indicative mood was stronger with irregular verbs than regular verbs, whose processing was more “effortful” (p. 837). Finally, Fernández Cuenca and Jegerski (2025) used an eye-tracking task to assess adult HSs’ knowledge of lexically selected subjunctive mood when reading. While HSs were sensitive to mood with all verb types, as in López-Beltrán and Dussias (2024), they distinguished more clearly between subjunctive and indicative mood with irregular verbs than with regular verbs, again suggesting that lexical-level knowledge affects HSs’ processing of morphosyntax.

1.3. Research Questions and Hypotheses

The research questions of the present study are as follows:

- RQ1: Are Spanish-dominant bilinguals (SDBs) sensitive to mood violations in Spanish? If so, will their sensitivity be affected by morphological regularity?

Hypothesis 1.

Based on a number of previous studies (e.g., Dracos & Requena, 2023; Fernández Cuenca & Jegerski, 2023, 2025; Giancaspro et al., 2022; López-Beltrán & Dussias, 2024; Perez-Cortes, 2025; Thane, 2025; Viner, 2016; inter alia), we hypothesize that (a) SDBs will be highly sensitive to mood violations in Spanish and (b) this sensitivity will not be affected by regularity.

- RQ2: Are adult HSs of Spanish sensitive to mood violations with regular and irregular verbs in Spanish?

Hypothesis 2.

Based on previous findings (e.g., Fernández Cuenca & Jegerski, 2023, 2025; Giancaspro et al., 2022; López-Beltrán & Dussias, 2024; Perez-Cortes, 2022; Thane et al., 2025), we hypothesize that (a) HSs will exhibit sensitivity to mood violations in Spanish and (b) their sensitivity to mood violations will be greater with irregular verbs than regular verbs.

- RQ3: Finally, does HSs’ sensitivity to mood violations change over the course of a semester abroad in Spain?

Hypothesis 3.

To our knowledge, there are no longitudinal studies of HSs’ processing of mood morphology—or any other morphosyntactic property, for that matter. Nonetheless, based on first-person accounts of HSs’ experiences in their linguistic/ancestral homeland (e.g., Sedivy, 2021; Sotomayor, 2013), we hypothesize that HSs will become more sensitive to mood violations over the course of a semester abroad. Given our prediction for RQ2, we expect this shift in grammatical sensitivity to be most evident with regular verbs, which HSs produce and process more variably.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

The study, which was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Wake Forest University [IRB-00024340; approval dates 25 August 2021, 22 May 2024], included two groups of participants, both Spanish-English bilingual adults between the ages of 19–29. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects in both groups.

The first group, which we will call the Spanish-dominant bilingual (SDB) group, consisted of 30 bilingual (but monolingually raised) college students who grew up in Spain and know English (self-rating: M = 7.2/10) but are still dominant in Spanish (self rating: M = 9.7/10). Although many bilingualism studies use such groups as a target/baseline, against which to directly compare the performance of a separate, experimental group, our purpose for including the SDBs is primarily methodological in nature. Since no previous studies have utilized self-paced reading to investigate Spanish speakers’ processing of lexically selected subjunctive in Spanish,2 testing this group allows us to validate our experimental design.

The experimental group consisted of ten HSs of Spanish, all students from the same US university studying abroad in Salamanca, Spain for a full semester.3 Because students were recruited from a program with relatively few HSs, it took three separate semesters to gather this data. Given our relatively small sample size, as well as the well-known heterogeneity of HSs, it is critical to provide a brief snapshot of some of the most pertinent educational/life experiences of this group (Bowles, 2018). Before we do so, however, we wish to underscore that the scope of this participant overview will be necessarily limited since HSs differ from one another in countless other ways (e.g., number of Spanish-speaking parents, sibling order, socioeconomic background, motivations for studying abroad, phenotype…etc…) and, consequently, there are as many profiles as there are individual HSs.

Of the ten HSs in the study, eight were second-generation (2G), meaning that one or both parents immigrated from a Spanish-speaking country as adults, and two were third-generation (3G), meaning that their Spanish-speaking parent(s) were born in the US to immigrants from a Spanish-speaking country (Portes & Rumbaut, 2014). Aside from one participant, whose Spanish-speaking family was from Spain, participants’ Spanish-speaking family members were from Latin America, specifically, Argentina, Colombia, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Mexico, and Puerto Rico. At the beginning of the SA program, participants’ proficiency was assessed via an Oral Proficiency Interview (OPI), conducted by the second author. Not surprisingly, participants’ initial OPI proficiency ranged greatly. While half of participants scored at the novice or intermediate levels (novice high: n = 2; intermediate mid: n = 1; intermediate high: n = 2), the other half scored in the advanced range (advanced low: n = 3; advanced high: n = 2).

In spite of these differences, the HSs in the study had a number of key characteristics in common. First, they considered themselves English-dominant, as determined by self-ratings in English (M = 9.5/10) and Spanish (M = 7.7/10). Second, all but one participant had traveled to a Spanish-speaking country before this trip, typically, though not always to their parents’ country of origin. Third, participants were studying Spanish at the university level, either as a minor (80%) or major (20%). Finally, all participants except for one were participating in the same SA program, which we will now describe in detail.

Nine of the ten HSs participated in the same semester-long program, which was limited exclusively to Spanish majors/minors at the second author’s university. The program was immersive and intensive in a number of ways, some typical of other SA programs and others unique. Students in the program stayed with local host families, enrolled in courses taught entirely in Spanish (e.g., a language course as well as assorted courses about literature, culture, film, and medicine, among other topics)4 and participated in a few week-long cultural excursions, during which they were under the direct supervision of a Spanish-speaking resident professor and two Spanish-speaking staff members. Perhaps the most defining characteristic of the program, however, was its strictly enforced language pledge, which students signed immediately after their first-week orientation. The language pledge required students to speak Spanish at all times—not just in class. Failure to adhere to this policy could result in possible grade reductions and even potential expulsion from the program (for repeated violations). While it is impossible to know the extent to which students obeyed this language policy in private, they seemed to follow it quite religiously in class, during group excursions, and when studying/completing homework at the study abroad center, which served as a social hub for students in the program.

The tenth and final HS did not participate in the same academic program as the rest of the students and only took one of her four classes in Spanish. Nonetheless, because this participant stayed with a Spanish host family and spent a lot of time at the study abroad center (where Spanish-language usage was enforced), we included them in the sample.

2.2. Procedure

Because the purpose of the Spanish-dominant bilingual group was to validate the experimental methodology—rather than assess potential changes in linguistic processing over time—the SDBs’ participation consisted of a single session, during which they completed a language background questionnaire, as well as a self-paced reading (SPR) task.

Participants in the HS group, on the other hand, completed two experimental sessions, both on site. (Grey (2018, p. 49) notes that “in situ within-subjects designs are arguably the experimental ideal for SA research”). During Session 1, which was always carried out in the first two weeks of the program, participants started by filling out a language background questionnaire, which was used to confirm their status as HSs and also gather other pertinent information about their linguistic profiles. Following the background questionnaire, participants completed an elicited imitation task (EIT), not reported here, as well as a SPR task, which tested their ability to process mood morphology while reading for comprehension. In Session 2, which was always scheduled during the last two weeks of the program, participants completed alternative versions of the EIT and the SPR tasks. (As we will explain further below, this ensured that participants in Session 2 did not encounter any of the same SPR sentences that they saw in Session 1). Aside from the EIT and SPR, which were always performed in that order, participants also completed oral proficiency interviews (OPIs) at the beginning and end of the semester.

2.3. Self-Paced Reading Task

The goal of the self-paced reading (SPR) task, which was administered via Paradigm (2016), was to examine participants’ on-line sensitivity to mood incongruencies in Spanish while reading sentences in real time. An advantage of using an SPR task rather than an off-line task (e.g., grammaticality judgment tasks) is that SPR experiments “are thought to provide a window into implicit processing and, possibly, into learners’ implicit underlying linguistic knowledge representations” (Marsden et al., 2018, p. 865). While judgment tasks are also intended to tap into learners’ underlying knowledge, the fact that they are off-line (e.g., not time-constrained) means that learners have the opportunity to draw on explicit grammatical knowledge while completing them. In any case, for each item of the SPR, participants saw sentences on a region-to-region basis in a left-to-right non-cumulative moving window. Each dash on screen represented a letter, while sets of dashes represented words, which were separated by spaces. At the beginning of each trial, participants pressed the space bar, causing the first group of dashes (e.g., the first word(s)) to be replaced by the first word or group of words in the sentence. With each subsequent press of the space bar, previous words disappeared from the screen, and the next group of words was revealed. Participants’ reaction time (RT), defined here as the “elapsed time between each key press” (Marsden et al., 2018, p. 861), was recorded for each group of words, which we will call regions.

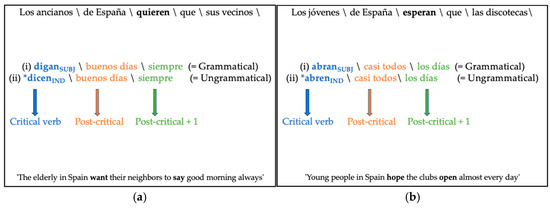

The full set of stimuli, which was preceded by a 4-sentence practice module, consisted of 128 sentences—divided into two blocks—with a 5–10 min break between. Of the 128 total sentences, 32 targeted lexically selected mood morphology. These items will be the focus of the present study. In each of the items in this condition, the matrix clause included a third person plural subject (e.g., los ancianos de España: ‘the elderly in Spain’), a trigger verb (e.g., quieren: ‘want’) that categorically selects for subjunctive mood, the complementizer que, and then a subordinate clause, also with a third-person plural lexical subject (e.g., sus vecinos: ‘their neighbors’). Two sample sentences—one with an irregular verb, the other with a regular verb—appear below in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Sample visualization of items from self-paced reading task, with three primary regions of interest highlighted in blue, orange, and green. (a) Irregular condition; (b) Regular condition. Participants saw the regions left-to-right and without colors, arrows, labels, or translations.

After pressing the space bar for the final time in each trial, a multiple-choice comprehension question appeared on screen, always about the semantic content of the recently finished sentence. (For a sample comprehension question, see Figure 2 below, which matches with the sentence presented in side (a) of Figure 1). The goal of these questions was to ensure that participants focused on the meaning of what they read rather than simply pressing the buttons without paying attention. Participants responded to the comprehension questions by pressing A or B on the keyboard. As soon as they responded to each question, the next trial would begin.

Figure 2.

Sample comprehension question for sentence (a) in Figure 1.

The eight trigger verbs that were used in this task—displayed below in Table 1—appeared four times each, twice in each grammaticality condition. Grammatical items (k = 16) included subjunctive mood morphology on the subordinate verb, while ungrammatical items (k = 16) included indicative mood morphology, which should be unexpected given the mood selection requirements of the preceding trigger verb. In principle, the presence of unexpected morphology in the ungrammatical condition should cause participants to slow down either at (or after) the subordinate verb. Consequently, participants who are sensitive to mood incongruencies would be expected to have longer RTs in the ungrammatical condition than in the grammatical condition.

Table 1.

Trigger verbs for self-paced reading task.

A total of 16 subordinate verbs appeared in this task, once in each grammaticality condition. (For a full list of these subordinate verbs, see Appendix A Table A1). To assess the effect of morphological regularity on participants’ processing, half of the items in each grammaticality condition had regular subordinate verbs (e.g., abrenIND/abranSUBJ: ‘open’, as in side (b) of Figure 1) and half had irregular subordinate verbs (e.g., dicenIND/diganSUBJ: ‘say’, as in side (a) of Figure 1). Following Giancaspro et al. (2022), regular verbs were defined as those whose subjunctive and indicative forms differ from one another only via a vowel shift (from -e- to -a-), while irregular verbs were defined as those whose subjunctive inflections involve a vowel shift and change to their verbal root (specifically, the presence of a -g-.)5

Regardless of regularity, all subordinate verbs were third-person plural and bisyllabic so as to reduce other potential differences that might affect comparisons across conditions. To mitigate frequency effects (Perez-Cortes & Giancaspro, 2022), we sought to ensure that irregular and regular verbs were of comparable frequency according to the SUBTLEX corpus (Cuetos et al., 2011). While irregular and regular verbs were not different from each other in terms of average log frequency/million words, irregular indicative verbs were significantly more frequent than regular indicative verbs. (Unfortunately, as noted by Fernández Cuenca and Jegerski (2023), Giancaspro et al. (2022), and López-Beltrán and Dussias (2024), frequency/regularity are highly correlated and can be hard to disentangle). To address this issue statistically, we included log frequency per million words as a covariate in data analyses.

In following with Jegerski (2013) and Keating and Jegerski (2015), the 32 experimental items described above were interspersed with 32 distractors (targeting subject-verb agreement) and 64 fillers (targeting other grammatical anomalies). The 128 total items were pseudorandomized to avoid repetition of the same category in back to back items. For a summary of the experimental conditions, see Table 2.

Table 2.

Breakdown of items in the self-paced reading task by condition.

Given the longitudinal nature of the study—at least for the HSs—it was necessary to design the items to allow for the creation of two maximally comparable versions of the SPR task. To do so, we created two counterbalanced lists: Version A and Version B.6 In order to ensure that participants never saw the same item twice in the same session—which might have drawn their attention to the key experimental manipulations—participants saw one version of each experimental sentence in Session 1 and the other version of that same sentence in Session 2. Participants who saw the grammatical variant of the sentence in Figure 1 in their first session, for example, would see the ungrammatical variant of that sentence in their next testing session.

Since critical regions are an integral concept of the methodology, we conclude with a brief description of the three regions of focus in the present study, shown below. The critical region (blue in Figure 1) refers to the subordinate verb itself, always a single, bi-syllabic verb. The post-critical region (orange in Figure 1) refers to the next word/phrase. Finally, the post-critical + 1 region (green in Figure 1) refers to the word/phrase after that. To reiterate a point made earlier in this section, participants who are sensitive to mood incongruencies would be expected to slow down in the ungrammatical condition—relative to the grammatical condition—at either the critical region or any of the subsequent regions (collectively known as “spillover” regions).

2.4. Data Trimming and Statistical Analyses

The dependent variable in the present study is reading time (RT), which was used to determine whether participants were sensitive to grammaticality across three regions of the experimental sentences: (a) the critical region, (b) the post-critical region, and (c) the post-critical + 1 region. Participants who are sensitive to grammaticality are expected to have significantly higher RTs in the ungrammatical conditions than in the grammatical conditions as a result of processing difficulties caused by mood incongruencies, that is, indicative mood morphology after a trigger verb that selects for subjunctive mood. This effect can be evident at one or more of these three regions (Foote, 2011; Jegerski & Keating, 2023).

Prior to conducting the statistical analyses, we took a few steps to clean up the data. First, following the recommendations of Keating and Jegerski (2015), we removed all sentences where participants responded incorrectly to the post-stimulus comprehension question. This step, which resulted in the loss of 6% of the data for the SDBs and 5.5% of the data for the HSs (6% at Session 1; 5% at Session 2), ensures that participants’ RTs are not affected by failures to understand the content of a sentence. After removing these responses, we eliminated unusually high and low RTs (e.g., 100 ms or below and 3000 ms or above) that may have stemmed from lapses in concentration (Baayen & Milin, 2010; Keating & Jegerski, 2015). Finally, after all remaining data was log-transformed to reduce positive skew, participants’ RTs were analyzed via mixed effects linear regressions with the lme4 package (Bates et al., 2015). Rather than analyzing the two groups in the same statistical model, we conducted separate statistical analyses for each group, a decision that is based on two key rationales. First, the SDBs only completed one session, meaning that the variable, Session, is only relevant for the HSs. Second, following arguments by Giancaspro et al. (2022), we believe that it is best to avoid direct between-group comparisons between HSs and control groups unless the control groups are carefully matched with the HSs across a wide variety of critical variables (e.g., dialectal background, socioeconomic status, speech community…etc…). Since this was not possible in the present study, we opted to prioritize within-group (rather than between-group) statistical analyses.

In the first model, which was used to analyze the SDBs’ responses, the fixed effects were Grammaticality and Verb Regularity (as well as their interaction), and the random effects were subject and item. In the second model, which was used to analyze the HSs’ responses, the fixed effects were Grammaticality, Verb Regularity, and Session (as well as their interactions), and the random effects were subject and item. Given that there were differences in the relative frequency of the irregular and regular verbs in our experiment (Section 2.3), lexical frequency was also added to both models as a covariate. To determine the optimal random-effects structure, models were initially specified using a maximal structure (Barr, 2013). Each model was first run with the maximal random effect structure, and when the model did not converge, this initial structure was simplified incrementally to identify the maximal effect structure that achieved convergence. We used Satterthwaite’s approximation for degrees of freedom with the lmerTest package for R (R Core Team, 2024; Kuznetsova et al., 2014) to obtain p values. When necessary, pairwise comparisons were conducted using the emmeans package with the Bonferroni correction (Lenth et al., 2018). Finally, alpha was set at 0.05, and interactions with p-values less than 0.10 were explored as potentially significant so as to minimize the likelihood of Type II error (Larson-Hall, 2015).

3. Results

3.1. Spanish-Dominant Bilinguals

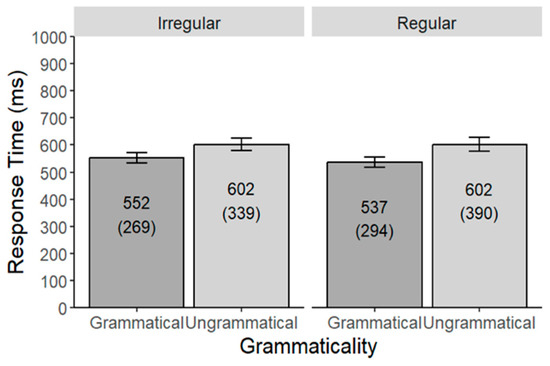

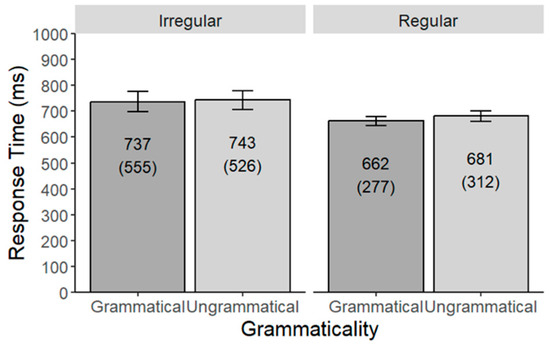

To answer RQ1, which asked whether SDBs are sensitive to mood incongruencies in Spanish, we now turn to the participants’ RTs. Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5 illustrate the SDBs’ mean RTs by region and grammaticality, while the statistical output from the mixed effects modeling (for each of our three regions of interest) is presented in Table 3. As shown in Table 3 and Figure 3, the SDBs were not sensitive to grammaticality at the critical verb, estimate = 0.05, SE = 0.03, t = 1.40, p = 0.16.

Figure 3.

SDBs’ mean RTs at critical verb: irregular + regular verbs.

Figure 4.

SDBs’ mean RTs at post-critical region: irregular + regular verbs.

Figure 5.

SDBs’ mean RTs at post-critical + 1 region: irregular + regular verbs.

Table 3.

Statistical output for Spanish-dominant bilinguals across three regions of interest.

In the post-critical region (Figure 4), however, there was a statistically significant effect of grammaticality, estimate = 0.09, SE = 0.03, t = 2.77, p < 0.001. Because participants’ RTs were significantly higher in the ungrammatical condition than in the grammatical condition, we can conclude that this group is processing mood incongruencies, as hypothesized. The lack of a statistically significant interaction between Grammaticality and Verb Regularity indicates, furthermore, that the SDBs’ sensitivity to mood incongruencies is not shaped by verb regularity, also as hypothesized.

Finally, by the time that the SDBs reach the post-critical + 1 region (Figure 5), they are no longer sensitive to mood incongruencies, as shown in the bottom third of Table 3. In other words, whatever processing costs were initially incurred by the mood incongruency, the SDBs have overcome these costs two regions later.

3.2. Heritage Speakers

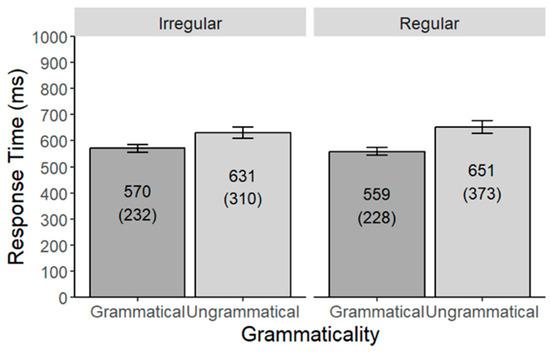

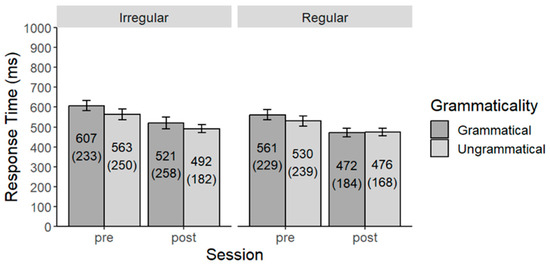

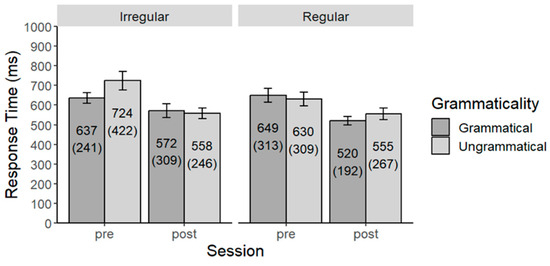

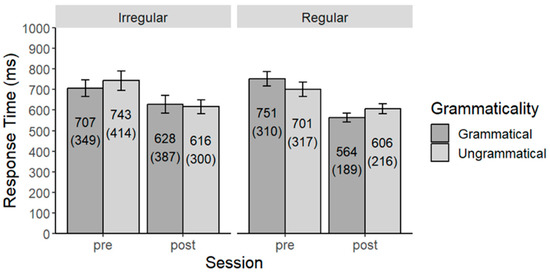

Now that we have confirmed the validity of the experimental task, we turn to RQs 2–3, which asked (a) whether HSs are sensitive to mood incongruencies with regular and irregular verbs and (b) whether their sensitivity changed over the course of a semester abroad in Spain. Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8 illustrate HSs’ mean RTs by regularity, grammaticality, and session at each of the three regions of interest: critical verb (Figure 6), post-critical verb (Figure 7), and post-critical verb + 1 (Figure 8). Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6 provide the statistical output for the mixed effects models that we ran for each of the three regions of interest.

Figure 6.

HSs’ mean RTs at critical verb: irregular + regular verbs, Session 1 and 2.

Figure 7.

HSs’ mean RTs at post-critical region: irregular + regular verbs, Session 1 and 2.

Figure 8.

HSs’ mean RTs at post-critical + 1 region: irregular + regular verbs, Session 1 and 2.

Table 4.

Statistical output for HSs: Critical verb region.

Table 5.

Statistical output for HSs: Post-critical verb region.

Table 6.

Statistical output for HSs: Post-critical verb + 1 region.

At the critical verb, shown in Figure 6 and Table 4, HSs were not sensitive to Grammaticality (p = 0.40). Nonetheless, there were two statistically significant effects in this region. First, there was an effect of Session, signaling that participants’ RTs were significantly lower in the Session 2 than in Session 1, estimate = 0.16, SE = 0.04, t = 3.94, p < 0.01. Second, there was a marginally significant effect of Verb Regularity, meaning that HSs RTs were lower with regular verbs than with irregular verbs, estimate = −0.08, SE = 0.04, t = 1.94, p = 0.05.

At the post-critical region (Figure 7, Table 5), there was once again no statistically significant effect of grammaticality. Interestingly, however, there was a marginally significant three-way interaction between Grammaticality, Verb Regularity, and Session, estimate = −0.17, SE = 0.10, t = −1.66, p = 0.09. Considering the relevance of this interaction for our research questions, we explore it further here.7

In Session 1, HSs were sensitive to mood incongruencies—and in the expected direction—but only with irregular verbs (estimate = −0.06, SE = 0.05, t = −1.76, p = 0.03) and not regular verbs (estimate = 0.02, SE = 0.07, t = 0.28, p = 0.77). In Session 2, on the other hand, HSs were sensitive to mood—and in the expected direction—but only with regular verbs (estimate = −0.09, SE = 0.04, t = −1.90, p = 0.05). Over the course of a semester abroad, therefore, it appears that the HSs in this sample became sensitive to mood incongruencies with regular verbs and yet simultaneously lost sensitivity to mood incongruencies with irregular verbs. We will return to this puzzling finding in the Discussion.

Three main effects in the post-critical verb region are also worth discussing briefly here. First, participants’ RTs were significantly lower in Session 2 than in Session 1 (p < 0.01), suggesting that their reading speed has increased considerably over the course of the semester abroad. Second, also mirroring the data from the previous region, participants exhibited a marginally significant effect of regularity, specifically, by reading faster with regular verbs than irregular verbs (p = 0.06). Finally, participants in this region experienced a significant effect of Frequency (estimate = −0.08, SE = 0.02, t = −3.41, p < 0.01), meaning that their RTs were significantly higher when subordinate verbs were relatively less frequent.

Lastly, we turn to our third and final region of interest: the post-critical + 1 region (Figure 8, Table 6). As in previous regions, there is no main effect of Grammaticality here, meaning that the HSs do not have higher RTs with ungrammatical items than with grammatical items. That said, there was a strong main effect of Session, indicating that HSs’ RTs in the post-critical + 1 verb region decreased sharply from Session 1 to Session 2.

4. Discussion

Aside from a few qualitative accounts written by HSs who have traveled abroad (e.g., Sedivy, 2021; Sotomayor, 2013), little is known about heritage bilinguals’ linguistic development—and processing—in a study abroad (SA) context. In the present study, therefore, we complement the limited previous literature on this topic by adding new, quantitative evidence to our understanding of Spanish HSs’ linguistic trajectory during a semester-long sojourn in a Spanish-dominant country. Our attempt to address this very understudied area of research was guided by three research questions (RQs), one aimed at validating our methodology with Spanish-dominant bilinguals (SDBs), and two directed at the knowledge of HSs, who constituted the primary experimental group.

As hypothesized for RQ1, our SDB group was sensitive to mood incongruencies in Spanish, as evidenced by their significantly slower reading times (RTs) in the ungrammatical condition, where non-target indicative mood morphology appeared on subordinate verbs, than in the grammatical condition, where subjunctive mood morphology was used. Importantly, this effect was statistically significant in only one region—specifically, the post-critical verb region—and it was not at all affected by the morphological regularity of subordinate verbs. In summary, then, the experimental methodology worked as expected, and the SDBs performed in accordance with previous studies of this topic—both on-line and off-line—by demonstrating strong sensitivity to mood incongruencies that was unaffected by lexical-level details of the subordinate verb, such as regularity or frequency.

RQs 2 and 3 built on these findings by examining (a) whether HSs were sensitive to mood incongruencies with regular and irregular verbs and (b) whether that (in)sensitivity changed over the course of a semester abroad. Based on previous studies, it was hypothesized that HSs would be sensitive to mood—more so with irregular verbs than regular verbs—and that their sensitivity would increase over time, presumably as a result of temporarily boosted heritage language (HL) activation and use (Putnam & Sánchez, 2013).

The results only partially supported these hypotheses. As expected, HSs in Session 1 were more sensitive to grammaticality with irregular verbs than with regular verbs, thereby aligning with previous off-line and on-line research with HSs. Also as expected, HSs became more sensitive to mood on regular verbs over the course of a semester abroad. Although they did not show a grammaticality effect with regular verbs at Session 1, at Session 2, HSs were clearly sensitive to mood incongruencies with regular verbs, suggesting that SA immersion can facilitate morphosyntactic processing in the HL. Puzzlingly, though, the HSs in this study exhibited the inverse pattern with irregular verbs. After clearly picking up on mood incongruencies with irregular forms in Session 1, as expected, HSs at Session 2 no longer did so, an unanticipated shift that belies simple explanation.

In light of this unexpected result, could it be possible that the HSs’ apparent psycholinguistic development over the course of their SA experience is just experimental noise? We believe that this is not the case, for the following reasons. First, HSs’ reading speed was much faster at Session 2 than Session 1—in all three regions of interest—and without any drop-off in comprehension accuracy. As argued by Grey (2018), such a pattern points directly to improved processing efficiency.8 Second, all HSs in the study improved their OPI proficiency from Session 1 to Session 2, thereby providing a secondary measure of linguistic progress over the course of the semester abroad. Third, it appears that HSs’ perplexing insensitivity to mood distinctions with irregular verbs at Session 2 may be driven, at least in part, by underlying differences in how they store and access irregular and regular verbs, respectively, which may shift over time. Consistent with this possibility is the fact that HSs’ RTs were lower with regular than irregular verbs—regardless of grammaticality—at both the critical verb and post-critical verb. Nonetheless, the specific mechanics of this admittedly speculative possibility are a topic for future investigation.

The present study suffers from a few key limitations that we wish to highlight briefly here. First, our sample of HSs was both small and heterogeneous, largely due to the demographics of the SA program itself. For better generalizability, future research should recruit larger and more homogeneous samples, perhaps via SA programs targeted specifically at HSs. Second, the present study lacked a delayed post-test, which could have further bolstered the arguments provided here. The most convincing way to demonstrate the effects of SA on HSs’ processing would be to show both a boost in their sensitivity during the program itself, as in the present study, as well as subsequent regressions (or slowdowns) following participants’ return home. Although the logistics of such a study would certainly be challenging, the pay-off could be great. Third, the method of choice in the present study—self-paced reading—is a blunter psycholinguistic instrument (Keating, 2022) than other alternatives, such as eye-tracking, and therefore may lead us to overlook growth in HSs’ linguistic processing that might be evident with other, more multi-faceted methods. We hope that future studies in this area make use of newer, more effective tools. Finally, as pointed out by an anonymous reviewer, the design of the study makes it difficult to isolate SA immersion as the sole, driving factor behind the changes in HSs’ processing of subjunctive mood over the course of a semester. Future research could address this limitation either by (a) comparing HSs in a SA program to HSs who are taking the same number of Spanish classes but not studying abroad or (b) testing HSs who are studying abroad but not taking classes in Spanish.9

In spite of all of these shortcomings, we believe that the present study makes critical—if also preliminary—contributions to our understanding of HL processing and HL grammars more generally. To this day, almost all experimental research on adult HSs takes place at a single time point, making our view of speakers’ HL knowledge more of a superficial snapshot than a comprehensive home video. (In fact, we are unaware of any longitudinal processing studies with adult HSs and very few longitudinal studies with adult HSs at all10). While snapshot-style research sheds important light on what HSs know at a given moment in time, it deprives us of the opportunity to see the dynamic nature of HL grammars, which wax and wane over time in response to a multitude of changing life experiences, linguistic and otherwise. Understanding heritage grammars in their full color, therefore, will necessarily involve tracing the trajectories of individual HSs—such as Sonia Sotomayor and Julie Sedivy—as their experience with and exposure to the HL changes over time. Pursuing such a path—and with a psycholinguist’s toolkit in hand—may just reveal that HSs’ vivid, qualitative accounts of (re)immersion in the HL line up neatly with, and even complement, the results of carefully controlled laboratory research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.G. and S.F.C.; methodology, D.G. and S.F.C.; software, S.F.C.; validation, D.G. and S.F.C.; formal analysis, D.G. and S.F.C.; investigation, S.F.C.; resources, D.G. and S.F.C.; data curation, S.F.C.; writing—original draft preparation, D.G. and S.F.C.; writing—review and editing, D.G. and S.F.C.; visualization, S.F.C.; supervision, S.F.C.; project administration, S.F.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board at Wake Forest University; IRB-00024340; approval dates 25 August 2021, 22 May 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Anonymized data can be obtained by contacting the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HL | heritage language |

| HS | heritage speaker |

| INDIC | indicative mood |

| OPI | oral proficiency interview |

| RT | reading/response time |

| SA | study abroad |

| SDB | Spanish-dominant bilingual |

| SPR | Self-paced reading |

| SUBJ | subjunctive mood |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Subordinate verbs used in self-paced reading experiments. The first eight verbs are irregular, and the second eight verbs are regular. All are inflected for third-person plural, since all items in the SPR experiment involved third-person plural subjects. In the second and third columns of Table A1, hyphens mark syllables.

Table A1.

Subordinate verbs used in self-paced reading experiments. The first eight verbs are irregular, and the second eight verbs are regular. All are inflected for third-person plural, since all items in the SPR experiment involved third-person plural subjects. In the second and third columns of Table A1, hyphens mark syllables.

| Lexeme | Indicative Form | Subjunctive Form |

|---|---|---|

| caer (‘fall’) | ca-en | cai-gan |

| decir (‘say’) | di-cen | di-gan |

| poner (‘put’) | po-nen | pon-gan |

| salir (‘leave’) | sa-len | sal-gan |

| tener (‘have’) | tie-nen | ten-gan |

| traer (‘bring’) | tra-en | trai-gan |

| valer (‘to be worth’) | va-len | val-gan |

| venir (‘to come’) | vie-nen | ven-gan |

| abrir (‘to open’) | a-bren | a-bran |

| beber (‘to drink’) | be-ben | be-ban |

| comer (‘to eat’) | co-men | co-man |

| correr (‘to run’) | co-rren | co-rran |

| cumplir (‘to follow’) | cum-plen | cum-plan |

| leer (‘to read’) | le-en | le-an |

| subir (‘to go up’) | su-ben | su-ban |

| vivir (‘to live’) | vi-ven | vi-van |

Notes

| 1 | See Perez-Cortes (2022) for evidence of regularity effects in a study of contextually selected subjunctive mood in Spanish. |

| 2 | For studies that use self-paced reading to assess other types of subjunctive mood, see Cameron (2017) and Villegas et al. (2013). |

| 3 | As discussed by Shively (2016), many US-born/raised HSs study abroad in Spain, which continues to be a very popular destination for American university students (George & Hoffman-González, 2019). Some HSs studying abroad in Spain face criticism from locals for their dialectal background and/or way of speaking (Peace, 2023), an experience which might affect their linguistic development. Nonetheless, not all HSs have this experience (Peace, 2023). Furthermore, because HSs hear linguistic criticism even when traveling to their “ancestral country” (Riegelhaupt & Carrasco, 2000), there is no clear way to eliminate potential effects of these negative experiences on HSs’ linguistic development abroad. |

| 4 | An anonymous reviewer suggested that explicit grammar instruction on the subjunctive mood in class could cause changes in participants’ sensitivity to mood over time. Nonetheless, we think it is very unlikely that this would be enough to affect participants’ on-line processing of mood. The L2 Spanish learners in Fernández Cuenca and Jegerski (2023), for example, were not sensitive to mood on regular verbs, even though they had many years of classroom Spanish experience and in some cases even worked as Spanish teachers. Furthermore, as described above, the participants in this study were enrolled primarily in “content” courses that focused on literature, culture, film, and medicine, among other topics. Though the professors of these courses may have discussed subjunctive mood at some point in class, they did not focus on this topic, making it especially implausible that instruction would cause major changes in participants’ processing of mood over time. |

| 5 | Other researchers have categorized the regularity of subjunctive verbs in Spanish differently. Gudmestad (2012), for example, divides Spanish verbs into three regularity categories: (i) regular (e.g., come/coma: ‘eat’), (ii) irregular (e.g., duerme/duerma: ‘sleep’), and (iii) form-specific irregular (e.g., es/sea: ‘be’). Although Perez-Cortes (2022) and López-Beltrán and Dussias (2024) use a binary classification of regularity, as in the present study, their irregular verb category was more expansive than ours, specifically, by including inflections without the -g- consonant that appears in all of our irregular verbs. |

| 6 | Since the SDBs participated in one testing session, half completed Version A of the SPR task, and half completed Version B. |

| 7 | As noted by Luke (2017), p-values in mixed effects models are less certain than in simpler models. Furthermore, many researchers have begun to eschew dichotomous interpretations of statistical significance (e.g., Amrhein et al., 2019). |

| 8 | It is possible, as suggested by an anonymous reviewer, that participants’ faster RTs at Session 2 are caused (at least in part) by improvements in their reading comprehension skills and vocabulary and not necessarily by gains in morphosyntactic sensitivity. |

| 9 | Unfortunately, it will be very difficult to recruit participants for these comparisons. In the case of comparison (a), it will be difficult to find HSs who are not studying abroad and yet are enrolled in the same number of Spanish classes as HSs who are studying abroad. (Typically, HSs who study abroad take 3–4 Spanish classes). In the case of comparison (b), it will be challenging to find a group of HSs who are residing in an immersive study abroad context for a semester’s length of time but not taking Spanish classes. Most HSs who study abroad in a Spanish-speaking country take at least some courses in Spanish. |

| 10 | For research on how HL instruction affects HSs’ grammatical systems over time, see Bowles (2022) and contributions therein. |

References

- Amrhein, V., Greenland, S., & McShane, B. (2019). Scientists rise up against statistical significance. Nature, 567(7748), 305–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baayen, H., & Milin, P. (2010). Analyzing reaction times. International Journal of Psychological Research, 3(2), 12–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, D. J. (2013). Random effects structure for testing interactions in linear mixed-effects models. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, D., Maechler, M., Bolker, B., & Walker, S. (2015). Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software, 67, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosque, I. (2012). Mood: Indicative vs. subjunctive. In J. Hualde, A. Olarrea, & E. O’Rourke (Eds.), The handbook of Hispanic linguistics (pp. 371–394). Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Bowles, M. (2018). Outcomes of classroom Spanish heritage language instruction. In K. Potowski (Ed.), The Routledge handbook of Spanish as a heritage language (pp. 331–344). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bowles, M. (2022). Outcomes of university Spanish heritage language instruction in the United States. Georgetown University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bybee, J., Perkins, R., & Pagliuca, W. (1994). The evolution of grammar. University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, R. (2017). Lexical preference and online processing of the Spanish subjunctive. Linguistics Unlimited, 2, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Cuetos, F., Glez-Nosti, M., Barbón, A., & Brysbaert, M. (2011). SUBTLEX-ESP: Spanish word frequencies based on film subtitles. Psicológica, 32, 133–143. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, D., & Lekic, M. (2013). The heritage and non-heritage learner in the overseas immersion context: Comparing learning outcomes and target-language utilization in the Russian flagship. Heritage Language Journal, 10(2), 226–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, M. (2016). Corpus del español: Web/dialects. Available online: https://www.corpusdelespanol.org/web-dial/ (accessed on 20 August 2021).

- Dracos, M., & Requena, P. (2023). Child heritage speakers’ acquisition of the Spanish subjunctive in volitional and adverbial clauses. Language Acquisition, 30(1), 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dracos, M., Requena, P., & Miller, K. (2019). Acquisition of mood selection in Spanish-speaking children. Language Acquisition, 26(1), 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escalante, C., Viera, C., & Patiño-Vega, M. (2021). Linguistic development of Spanish heritage learners in study abroad: Considerations, implications, and future directions. In R. Pozzi, T. Quan, & C. Escalante (Eds.), Heritage speakers of Spanish and study aborad (pp. 181–198). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández Cuenca, S., & Jegerski, J. (2023). A role for verb regularity in the L2 processing of the Spanish subjunctive mood: Evidence from eye-tracking. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 45(2), 318–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández Cuenca, S., & Jegerski, J. (2025, June 9–13). Morphological regularity effects in the processing of the Spanish subjunctive by heritage speakers: An eye-tracking study [Paper presentation]. International Symposium on Bilingualism, San Sebastian, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Foote, R. (2011). Integrated knowledge of agreement in early and late English-Spanish bilinguals. Applied Psycholinguistics, 32, 187–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, A., & Hoffman-González, A. (2019). Dialect and identity: US heritage language learners of Spanish abroad. Study Abroad Research in Second Language Acquisition and International Education, 4(2), 252–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giancaspro, D. (2017). Heritage speakers’ production and comprehension of lexically and contextually selected subjunctive mood morphology [Doctoral dissertation, Rutgers University]. [Google Scholar]

- Giancaspro, D., Perez-Cortes, S., & Higdon, J. (2022). (Ir)regular mood swings: Lexical variability in heritage speakers’ oral production of subjunctive mood. Language Learning, 72(2), 456–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grey, S. (2018). Quantitative approaches for study abroad research. In C. Sanz, & A. Morales-Front (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of study abroad research and practice (pp. 48–57). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gudmestad, A. (2012). Toward an understanding of the relationship between mood use and form regularity: Evidence of variation across tasks, lexical items, and participant groups. In K. Geeslin, & M. Díaz-Campos (Eds.), Selected proceedings of the 14th Hispanic linguistics symposium (pp. 214–227). Cascadilla Proceedings Project. [Google Scholar]

- Jegerski, J. (2013). Self-paced reading. In J. Jegerski, & B. VanPatten (Eds.), Research methods in second language psycholinguistics (pp. 20–49). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Jegerski, J. (2018). Psycholinguistic perspectives on heritage Spanish. In K. Potowski (Ed.), The Routledge handbook on Spanish as a heritage language (pp. 221–234). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Jegerski, J., & Keating, G. (2023). Using self-paced reading in research with heritage speakers: A role for reading skill in the on-line processing of Spanish verb argument specifications. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1056561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keating, G. (2022). The effect of age of onset of bilingualism on gender agreement processing in Spanish as a heritage language. Language Learning, 72(4), 1170–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keating, G., & Jegerski, J. (2015). Experimental designs in sentence processing research: A methodological review and user’s guide. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 37(1), 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsova, A., Brockoff, P. B., & Christensen, R. H. B. (2014). lmerTest: Tests for random and fixed effects for linear mixed effect models (lmer objects of lme4 package). Available online: http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/lmerTest/index.html (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Larson-Hall, J. (2015). A guide to doing statistics in second language research using SPSS and R. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Lenth, R., Singmann, H., Love, J., Buerkner, P., & Herve, M. (2018). Emmeans: Estimated marginal means, aka least square means. Available online: http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/emmeans/index.html (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- López-Beltrán, P., & Dussias, P. E. (2024). Heritage speakers’ processing of the Spanish subjunctive: A pupillometric study. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism, 14(6), 809–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luke, S. G. (2017). Evaluating significance in linear mixed-effects models in R. Behavior Research Methods, 49(4), 1494–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marqués-Pascual, L. (2021). The impact of study abroad on Spanish heritage learners’ writing development. In R. Pozzi, T. Quan, & C. Escalante (Eds.), Heritage speakers of Spanish and study abroad (pp. 199–216). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Marqués-Pascual, L., & Checa-García, I. (2023). Lexical development of Spanish heritage and L2 learners in a study abroad setting. Study Abroad Research in Second Language Acquisition and International Education, 8(1), 115–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsden, E., Thompson, S., & Plonsky, L. (2018). A methodological synthesis of self-paced reading in second language research. Applied Psycholinguistics, 39(5), 861–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradigm. (2016). Experiment builder software [self-paced feature]. Available online: http://www.paradigmexperiments.com/index.html (accessed on 20 August 2021).

- Peace, M. (2023). ‘A mí no me gusta España mucho’ vs. ‘Yo quiero ir a toda España, me encanta España.’ Heritage speakers and their receptiveness to Spain and Peninsular Spanish. Study Abroad Research in Second Language Acquisition and International Education, 8(2), 197–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Cortes, S. (2022). Lexical frequency and morphological regularity as sources of heritage speaker variability in the acquisition of mood. Second Language Research, 38(1), 149–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Cortes, S. (2023). Re-examining the role of mood selection type in Spanish heritage speakers’ subjunctive production. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism, 13(2), 238–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Cortes, S. (2025). Obviating the mood, but mostly under control: Spanish heritage speakers’ acquisition of the binding constraints of desiderative complements. Language Acquisition, 32(1), 76–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Cortes, S., & Giancaspro, D. (2022). (In)frequently asked questions: On types of frequency and their role(s) in heritage language variability. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1002978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portes, A., & Rumbaut, R. (2014). Immigrant America: A portrait. University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pozzi, R., & Reznicek-Parrado, L. (2021). Problematizing heritage language identities: Heritage speakers of Mexican descent studying abroad in Argentina. Study Abroad Research in Second Language Acquisition and International Education, 6(2), 189–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, M., & Sánchez, L. (2013). What’s so incomplete about incomplete acquisition? A prolegomenon to modeling heritage language grammars. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism, 3(4), 478–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. (2024). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.r-project.org/ (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Riegelhaupt, F., & Carrasco, R. L. (2000). Mexico host family reactions to a bilingual Chicana teacher in Mexico: A case study of language and culture clash. Bilingual Research Journal, 24, 405–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedivy, J. (2021). Memory speaks: On losing and reclaiming language and self. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shively, R. (2016). Heritage language learning in study abroad: Motivations, identity work, and language development. In D. Pascual y Cabo (Ed.), Advances in Spanish as a heritage language (pp. 259–280). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Sotomayor, S. (2013). My beloved world. Knopf. [Google Scholar]

- Thane, P. D. (2025). Acquring morphology through adolescence in Spanish as a heritage language: The case of subjunctive mood. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 28, 373–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thane, P. D., Austin, J., Rodríguez, S., & Goldin, M. (2025). The acquisition of the Spanish subjunctive by child heritage and L2 learners: Evidence from a dual language program. Studies in Hispanic and Lusophone Linguistics, 18(1), 193–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villegas, Á., Demestre, J., & Dussias, P. E. (2013). Processing relative/sentence complement clauses in immersed Spanish-English speakers. In J. Cabrelli Amaro, G. Lord, & A. de Prada Pérez (Eds.), Selected proceedings of the 16th Hispanic Linguistics Symposium (pp. 70–79). Cascadilla Proceedings Project. [Google Scholar]

- Viner, K. (2016). Second-generation NYC bilinguals’ use of the Spanish subjunctive in obligatory contexts. Spanish in Context, 13(3), 343–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).