Abstract

This study explores the perception of (Austrian) standard German and Austro-Bavarian dialect varieties by 111 adult speakers of German as a second language (L2) in Austria, tested through ‘smart’ and ‘friendly’ judgements in a matched-guise task. Our goal was to determine whether L2 speakers, both at the group level and as a function of individual differences in standard German and dialect proficiency, reflect the attitudes of Austrian speakers by (a) judging the dialect higher in terms of friendliness in solidarity-stressing situations (e.g., in a bakery) and (b) attributing the standard variety a higher indexical value in terms of intelligence in status-stressing settings (e.g., at the doctor’s office), a phenomenon in Austrian-centered sociolinguistics known as ‘functional prestige’. Bayesian multilevel modeling revealed that L2 speakers do not adopt attitudinal patterns suggestive of functional prestige and even appear to reallocate certain constraints on sociolinguistic perception, which seems to depend on individual differences in varietal proficiency.

1. Introduction

Language attitudes can broadly be defined as “evaluative reactions to different language varieties” (Dragojevic, 2017, p. 2). Standard and nonstandard language varieties, for instance, often carry distinct socio-indexical value, meaning that individuals may attach different social meanings to particular linguistic features and, by extension, to particular language varieties. For example, while speakers of a standard language are often judged as having high status (i.e., intelligence), speakers of nonstandard varieties are typically evaluated more favorably in terms of solidarity (i.e., friendliness). Research has repeatedly identified that expert (i.e., first-language [L1]) speakers in a community are largely consistent in the social judgements and socio-indexical elements they attach to language variation (Coupland & Bishop, 2007; Giles & Powesland, 1975; Lambert et al., 1960; Preston, 2013; Trudgill & Giles, 1978; see for Bavarian-Austria Bellamy, 2012; Soukup, 2009). In light of this, a growing strand of variationist second language acquisition (SLA) research has begun investigating the extent to which second language (L2) speakers (in migrant communities) adopt the attitudinal patterns observed among speakers in the target-language population. The present study adds to this scope of research (see, e.g., Chappell & Kanwit, 2022; Clark & Schleef, 2010; Davydova et al., 2017; Ender et al., 2017, 2023; Ender, 2020; Kaiser et al., 2019; Michalski, 2021; Stotts, 2014; Schmidt, 2020; Wirtz & Pfenninger, 2023, 2024).

We studied L2 speakers of German living in the Austro-Bavarian setting. Using Bayesian multilevel statistical modeling, we address to what extent these L2 speakers have inter-individually acquired evaluative judgement patterns characteristic of the target-language community. We focus on participants’ evaluative judgements of the prestige and social attractiveness of (Austrian) standard German and Austro-Bavarian dialect varieties.1 More specifically, we report the results of a matched-guise judgement task investigating L2 speakers’ acquisition of attitudinal patterns suggestive of ‘functional prestige’, that is, whether participants (a) judge the dialect variety higher in terms of friendliness in solidarity-stressing situations (e.g., in a bakery) and (b) attribute the standard variety higher indexical value in terms of intelligence in status-stressing situations (e.g., at the doctor’s office). Additionally, since previous findings show that dialect proficiency can be a strong predictor of differences in evaluative judgements (e.g., Chappell & Kanwit, 2022; Ender, 2020), we integrate into the investigation whether variation in varietal proficiency (i.e., proficiency in standard German and in the Austro-Bavarian dialect) can predict the acquisition of evaluative judgements reflective of functional prestige.

2. Theoretical Background

Speakers of a standard or other socially prestigious language variety are typically judged higher in terms of status traits (e.g., intelligence, professionalism, wealth) and are attested an overall higher prestige in status-stressing situations (e.g., Dragojevic, 2017). By contrast, speakers of nonstandard language varieties are often downgraded (i.e., judged less positively) on such status traits, but they may be rated more favorably in terms of solidarity (e.g., friendliness and likeability), especially in solidarity-stressing contexts. Similar patterns hold true for the Austro-Bavarian context (Bellamy, 2012; Kaiser, 2006; Moosmüller, 1991; Soukup, 2009; Unterberger, 2024; Vergeiner et al., 2021): speakers of a standard German variety are considered more educated, intelligent, and polite, while Austro-Bavarian dialect speakers are typically perceived as more humorous, natural, easy going, and likeable (Bellamy, 2012; Soukup, 2009; Vergeiner et al., 2019, 2021).

Nonstandard varieties, however, may also possess ‘covert prestige’ (see Labov, 1966; Trudgill, 1972). Covert prestige refers to cases where nonstandard speakers are judged positively in terms of solidarity traits (e.g., friendliness and likeability), against the grain of the overall higher prestige of standard languages. This concept captures the idea that nonstandard varieties with a low mainstream social value may have high value in local, solidarity-stressing settings such as in a local bakery or with friends or family (e.g., Wolfram & Schilling-Estes, 2006), although these dispositions may not be overtly expressed or readily admitted to by those who hold them (Trudgill, 1972). While certain facets of covert prestige are observable in the Austro-Bavarian context (e.g., dialect varieties are judged more positively on solidarity traits in local settings), the general concept may not provide the best description of the attitudinal patterns found in Austria.

Soukup (2009) investigated the attitudes towards standard German and the Austro-Bavarian dialect among 242 Austrians (age range: 19–36 years) in the Austro-Bavarian dialect region, specifically, in Linz in Upper Austria. The stimuli consisted of brief monologues in a status-stressing context (i.e., in a communication seminar) spoken by speakers of a standard German and Austro-Bavarian dialect variety. The speakers of the dialect variety were judged as more natural, honest, friendly, emotional, relaxed, and likeable than their standard-speaking peers, while speakers of standard German were perceived as more polite, intelligent, educated, gentle, serious, and refined. On the basis of this study, Soukup (2009, p. 128) suggests the concept of ‘functional prestige’ to describe the attitudinal behavior found in the Austro-Bavarian context (see also, e.g., Kaiser et al., 2019). The conceptual demarcation between ‘functional’ and ‘covert’ is found in the notion that there are certain things a speaker can do with each of the varieties (Soukup, 2009). In other words, functional prestige expresses the subjective adequacy of standard German and dialect varieties for certain functions and situations, being, in turn, determined by the subjectively deemed higher affective or cognitive value of a respective variety. As a further distinction between ‘functional’ and ‘covert’, the prestige of many nonstandard varieties in Bavarian-speaking Austria is not necessarily hidden but rather functional and socially quite variable. That said, attitudes towards vernacularity are subject to substantial variation across the lifespan (e.g., in the context of regional dialects of American English: Dossey et al., 2020) and, in the L2, even across a period as short as three months (Wirtz & Pfenninger, 2024).

With respect to sociolinguistic competence in the L2, that is, “the capacity to recognize and produce socially appropriate speech in context” (Lyster, 1994, p. 263; see also Kanwit, 2022; Kanwit & Solon, 2023), the ability to perceive social meaning in the speech of others is essential (see, e.g., Geeslin & Long, 2014; Geeslin, 2018; Howard et al., 2013; Regan et al., 2009; Regan, 2010). Sociolinguistically competent speakers can convey a wealth of information via language variation, such as (a) expressing their identity via variable structures that denote membership to certain social groups or (b) by (intuitively) evoking socio-indexical interpretations (e.g., competence, sympathy, humor) from a listener by employing a range of standard, regional, and local dialect varieties. Acquiring sociolinguistic competence in the L2 is, thus, equally characterized by the acquisition of complex interpretive abilities (Chappell & Kanwit, 2022; Clark & Schleef, 2010; Davydova et al., 2017; Geeslin, 2018; Geeslin et al., 2018) as it is by learning to style shift and use registers appropriately (Howard et al., 2013; Mougeon et al., 2010; Regan, 2010).

In the Austro-Bavarian context, Ender et al. (2017) and Kaiser et al. (2019) demonstrated that adolescent and adult L2 speakers rated the standard German variety more positively than the dialect variety. That said, L2 speakers’ varietal judgements appear to be complexly intertwined with individual difference variables such as dialect proficiency, in that higher proficiency in the Austro-Bavarian dialect is related to overall higher ratings of dialect varieties (Ender, 2020). These results, however, were strictly based on L2 speakers’ overall impression of the varieties. This approach necessarily neglects possible differences between the indexical elements of status and solidarity and, moreover, the effects of these indexical elements in combination with contextual variables, such as the status- or solidarity-stressing nature of a situation, on L2 speakers’ evaluative judgements (see Kaiser et al., 2019). Wirtz (in press) addressed this shortcoming by analyzing how 40 adult speakers of L2 German and with L1 English evaluated standard German and the Austro-Bavarian dialect on the indexical domain of status (i.e., intelligence judgements) and solidarity (i.e., friendliness judgements). He found that these L2 speakers demonstrated judgement patterns consistent with functional prestige (i.e., more positive attitudes towards standard German in terms of intelligence and more positive attitudes towards the dialect variety in terms of friendliness). These rating patterns, however, may arguably be an artifact of sociolinguistic transfer (Durrell, 1995), i.e., transferring sociolinguistic information from the L1 to the L2 variation environment. Under a qualitative analytical lens, Ender et al. (2023) found among L2 users with heterogeneous language backgrounds that participants who attributed the dialect higher overall judgements demonstrated attitudinal behavior more confluent with target-like norms.

The previously discussed research on L2 speakers’ attitudinal patterns in the Austro-Bavarian context has (a) only considered comparatively small samples (i.e., approximately 40 L2 participants in each respective study), (b) fallen victim to sample- and design-related confounders (e.g., sociolinguistic transfer), or (c) neglected how differences in evaluative judgements of standard German and dialect varieties manifest as a function of the indexical elements of status and solidarity. Such factors make it difficult to determine whether L2 speakers, indeed, adopt attitudinal patterns confluent with the notion of ‘functional prestige’ or whether the results are simply an artifact of design-related discrepancies. Here, we attempt to address these shortcomings by analyzing the evaluative judgements of standard German and the Austro-Bavarian dialect on the indexical domains of status and solidarity among 111 adult speakers of German as an L2 living in the Bavarian-speaking dialect regions in Austria. We take into account how contextual conditions (in a doctor’s office vs. in a bakery) in combination with a respective language variety (standard German vs. dialect) can differently influence L2 speakers’ socio-indexical evaluations, and also whether these evaluations may be sensitive to differences in L2 speakers’ self-reported proficiency in standard German and in the Austro-Bavarian dialect.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Aim and Research Questions

The aim of this study is to examine the question as to whether adult speakers of L2 German adopt evaluative judgements mirroring the conceptual notion of ‘functional prestige.’ In this vein, the following exploratory research questions are addressed:

- RQ1:

- To what extent do adult L2 speakers’ attitudinal patterns regarding standard German and dialect varieties display (signs of) ‘functional prestige’?

- RQ1a:

- To what extent is the dialect-speaking salesperson judged as more friendly than the standard German-speaking salesperson?

- RQ1b:

- To what extent is the standard German-speaking doctor judged as more intelligent than the dialect-speaking doctor?

- RQ2:

- To what extent do differences in self-reported standard German and Austro-Bavarian dialect proficiency (i.e., varietal proficiency) predict the acquisition of attitudinal patterns suggestive of functional prestige?

- RQ2a:

- To what extent is the dialect-speaking salesperson judged as more friendly than the standard German-speaking salesperson as a function of self-reported varietal proficiency?

- RQ2b:

- To what extent is the standard German-speaking doctor judged as more intelligent than the dialect-speaking doctor as a function of self-reported varietal proficiency?

3.2. Participants

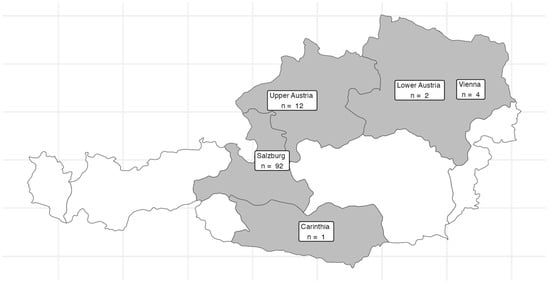

In total, 111 L2 speakers (78 women and 33 men) from Lower Austria, Upper Austria, Salzburg, Vienna, and Carinthia completed the online experiment (see Figure 1). The pool of respondents consists of people in young and mature adulthood, with 22 having started learning German at a relatively young age (i.e., under 16). The present dataset can be characterized as a convenience sample, and the participants were recruited via fliers and word of mouth. The questionnaire was closed (and, thus, the sample size determined) once the response rates had stagnated. Due to the convenience sample, it was not possible to stratify by sociolinguistic factors such as age or gender, as is otherwise typical of variationist sociolinguistics work (e.g., Labov, 1972), and the sample is, therefore, also characterized by marked heterogeneity in terms of place of birth, L1, and occupational status. There was a total of 50 different countries of birth, with the most common being the USA (n = 8); Ukraine (n = 7); China and Italy (n = 6, respectively); and Korea, Russia, and the United Kingdom (n = 5, respectively). There was a total of 37 reported L1s, the most common being English (n = 18); Arabic, Russian, and Spanish (n = 7, respectively); and Italian and Ukrainian (n = 6, respectively). The most often reported current occupation was student (n = 25), and other professions included teacher, truck driver, salesperson, hairdresser/barber, and engineer, among others. Our participants, moreover, reported a high degree of multilingualism, both in terms of further native languages and proficiency in a (or multiple) second or foreign language(s) in addition to German. Regarding additional foreign/second languages, the most reported were English (n = 70), French (n = 19), and Spanish (n = 17), with a mean of 1.9 (SD = 0.9) reported additional foreign or second languages spoken in addition to German. The participants were highly educated, with the majority holding at least one university degree (bachelor’s degree: n = 32; master’s degree: n = 20; doctoral degree: n = 3) or enrolled in a university program (enrolled in a Bachelor’s degree: n = 30; enrolled in a Master’s degree: n = 10). Only 13 participants reported a school-leaving certificate as their highest education, and 3 reported not having an educational degree. Finally, the participants differed in terms of their self-reported varietal proficiency, captured via aggregated 100-point slider scale self-reports on how L2 speakers judged their standard German and Austro-Bavarian dialect proficiency in terms of reading, writing, listening, and speaking. Table 1 outlines the participants’ self-reported proficiency and additional relevant socio-demographic information.

Figure 1.

Regional distribution of participants.

Table 1.

Participant overview.

What is more, this participant pool does justice to the call in Long (2022, p. 430) to investigate uncommonly studied language pairs in variationist SLA (that is, other than strictly speakers of L1 English acquiring L2 French or Spanish), and importantly that “learners in these under-researched contexts will reflect a broad diversity of linguistic, cultural, and social backgrounds”.

3.3. Tasks and Procedure

This rating task consisted of a classic within-person matched-guise design (Lambert et al., 1960), in which the participants rated four verbal stimuli spoken by two male speakers (approximately 7 min). The stimuli in question comprised everyday greeting sequences, two of which were produced in an (Austrian) standard German variety and two of which were in an Austro-Bavarian dialect variety. The standard language stimuli correspond to a broad and usage-oriented definition of spoken standard language. Herein, we assume that the Austrian standard can evince regional characteristics, but it nonetheless represents the most supra-regional and also the most formal way of speaking among educated Austrian speakers (Elspaß & Kleiner, 2019). This also corresponds to the idea of the matched-guise design, which envisages that speakers express themselves in two different varieties: in this case in an Austro-Bavarian dialect and an Austrian standard variety. The dialectal greetings contained salient dialect features (see, e.g., Kaiser et al., 2019 for a more extensive description of the matched-guise tasks). These features are primarily phonetic in nature, such as a-darkening and l-vocalization. Morphosyntactic differences, such as the cliticized realization of the second personal plural (e.g., dial. mechtens vs. standard German möchten Sie), were only included in unavoidable cases in which the authenticity of the language use in the guises would have suffered. Table 2 demonstrates the marked, and perceptually very salient, differences between varieties:

Table 2.

Excerpts from the matched-guise task.

The greeting sequences and speakers were moreover tailored to reflect different contextual conditions in the form of different occupations: one speaker played the role of a delicacies salesperson, the other of a doctor. These contextual conditions were chosen to capture possible differences in the functional prestige of the different varieties, that is, that speakers of a standard variety could be perceived as more intelligent in status-stressing situations (i.e., at the doctor’s office), whereas speakers of a dialect variety might be judged as more friendly in solidarity-stressing contexts (i.e., in a bakery). This choice was also informed by prior work from linguistics and psychology underscoring that attitudinal behavior is contextually situated (Gawronski et al., 2014; Levon & Ye, 2020), and thus, “the evaluation of a behavior in one context does not necessarily apply in another” (Levon et al., 2021, p. 361). In line with matched-guise designs, the same speaker recorded the salesperson stimuli in both a standard German and a dialect variety, and the other speaker recorded the doctor stimuli in both varieties, which resulted in a total of four stimuli by two speakers. Importantly, the listeners were not informed that the same speaker recorded the stimuli in both varieties; the participants were exclusively asked to judge the respective speaker.

On each task trial, the participants were presented with four stimulus greeting sequences and were asked to rate the stimuli on a particular scale. Following Ender et al. (2017), Kaiser et al. (2019), and Dossey et al. (2020), one scale focused on the subjective indexical element of status (“How intelligent is this person?” [German: Wie intelligent ist diese Person?]) and the other on solidarity (“How friendly is this person?” [German: Wie freundlich ist diese Person?]). Rating responses could be selected on a 100-point slider scale, ranging between “not at all intelligent” to “very intelligent” (German: gar nicht intelligent—sehr intelligent) and “not at all friendly” to “very friendly” (German: gar nicht freundlich—sehr freundlich), respectively. The slider scales allow us to capture participants’ evaluative judgements on a continuous scale, which reflects the notion that speech—and, by extension, sociolinguistic perception—is gradient rather than categorical by nature (e.g., Kutlu et al., 2022).

Importantly, since we set out to gather data on a heterogeneous sample of L2 speakers, the survey was administered in standard German, and this because it was unfeasible to provide the survey in multiple different first languages. Of course, this may come with the caveat that the instructions and scales in standard German may influence participant response patterns, a limitation which we acknowledge. That said, it is typical of matched-guise designs administered to L1/expert speakers to provide instructions and scales in the respective standard variety as well. Any potential variety-related biases that may occur would, thus, also be present in comparable studies of L1/expert speakers (e.g., Kaiser et al., 2019).

The experimental procedure was fully computerized and administered online via Limesurvey. The presentation of the stimuli was blocked, in that each participant was asked to rate each speaker on one scale (e.g., friendliness) before proceeding to the next scale (e.g., intelligence). The order of the scale blocks was randomized, and the order in which stimuli were presented within each scale block was randomized.

3.4. Data Analysis

Bayesian mixed-effects models were fitted using the brms package (Bürkner, 2017) in R (R Core Team, 2020). We analyzed the friendliness and intelligence evaluative judgements in two respective models as a function of the stimulus’s contextual condition (i.e., salesperson vs. doctor; treatment coded; reference level: ‘salesperson’) and variety (i.e., variety of the respective stimulus; treatment coded; reference level: ‘dialect’) and their two-way interaction. Given that the rating data were necessarily bounded by 0 and 100 by virtue of the slider scale, we used the beta distribution (a canonical distribution family for proportion data), which maps the model estimates to the log odds space using the logit linking function. The advantage of the beta distribution is that it is bound to values between 0 and 1; however, it does not include 0 and 1. The rating data were, thus, first divided by 100, and values equal to 0 were manually set to 0.0001, and values equal to 1 were manually set to 0.9999. The random effects specifications included by-participant random intercepts.

The model formula described above was used to fit the data for the friendliness and intelligence ratings with 2000 iterations (1000 warmup). Hamiltonian Monte-Carlo sampling was carried out with 4 chains in order to draw samples from the posterior predictive distribution. The models were fitted with regularizing, weakly informative priors (Gelman et al., 2017; Vasishth et al., 2018) for the intercept term and all coefficient parameters, which were normally distributed and centered at 0 with a standard deviation of 5 (in log-odds space). Importantly, these priors were intended to aid in model computation, but they were not informative enough to influence the resultant model estimates.

To determine how probable RQ1a and RQ1b are, we proceed, using Bayesian hypothesis testing, by computing the probability from the posterior distribution that the difference δ between two conditions is larger than zero. We judge there to be compelling evidence if (a) δ > 0; (b) zero is not included in the 95% highest density interval (HDI; i.e., a type of credible interval, basically the Bayesian analog to the Frequentist confidence interval) of δ; and (c) the posterior P(δ > 0) is close to one (i.e., ≥0.95, Franke and Roettger, 2019). This Bayesian approach has the added advantage of allowing us to directly gauge the probability that a hypothesis holds true (conditional on the data, a data-generating model, and the prior specifications).

Finally, to test RQ2a and RQ2b concerning whether varietal proficiency (i.e., proficiency in standard German and in the Austro-Bavarian dialect) predicts the acquisition of attitudinal patterns confluent with the notion of functional prestige among individuals with L2 German, we computed Bayesian multilevel models in the same way as detailed above, with the addition of self-reported standard German and dialect proficiencies as predictor variables in the interaction with the contextual condition and stimulus variety. We follow the same procedure as outlined for RQ1a and RQ1b, the additional element being that we explore whether the differences in question become more or less pronounced with higher or lower self-reported varietal proficiency. To this end, we employ Bayesian visual methods for significance testing. We judge there to be compelling evidence if the 95% HDI of a difference δ at a select level of proficiency is greater than 0 (see also, e.g., Pfenninger, 2021 for a similar method using generalized additive modeling). Note that in these analyses, we initially included age of onset of acquisition of L2 German and participants’ length of residence in Austria as control variables. As these did not significantly predict differences in evaluative judgements, they were removed from the models and not further analyzed.2

4. Results

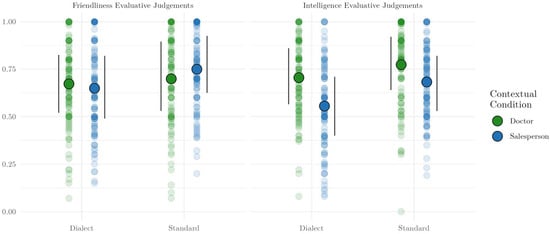

Figure 2 and Table 3 display the descriptive statistics on L2 speakers’ attitudinal behavior. As we can see, there is a high degree of variation in the range of evaluative judgement patterns recorded for each contextual condition (salesperson vs. doctor), indexical domain (friendliness vs. intelligence), and variety (standard German vs. Austro-Bavarian dialect). Given the prominent variance, and also in light of the repeated measures stemming from the within-person matched-guise design, Bayesian mixed-effects models were run.

Figure 2.

Descriptive overview of evaluative judgements. The semitransparent points display each individual’s evaluative judgements, while the solid points display the respective group mean. The lines beside each respective set of judgements represent the interquartile range.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics of evaluative judgements.

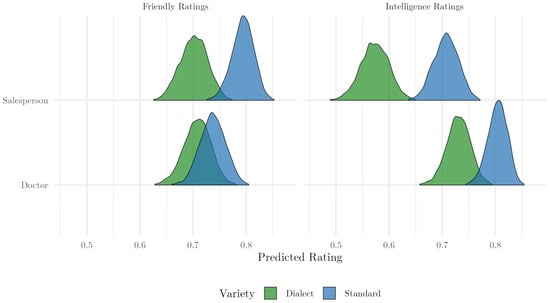

Figure 3 illustrates the conditional effects of the resultant Bayesian multilevel model. As noted, Bayesian models produce an entire distribution of probable values (i.e., the posterior distribution) for each effect, and the density plots below illustrate the predicted probabilities of L2 speakers’ evaluative judgements at the group level. Higher and steeper peaks indicate more likely values, that is, more probable evaluative judgement scores on the respective indexical domain and for the respective contextual condition and variety. The visualization shows that L2 speakers, at the inter-individual level, are predicted to rate the standard German variety higher across nearly all indexical domains and contexts. Only L2 speakers’ friendliness ratings of the doctor are comparatively similar between the two varieties: that is, the distributions of the standard German and the dialect variety overlap to a large degree.

Figure 3.

Posterior distributions of the predicted ratings of the standard German- and dialect-speaking salesperson and doctor in terms of friendliness and intelligence. Density plots estimate the probability density of the data at different values.

4.1. To What Extent Do L2 Speakers Acquire Attitudinal Patterns Suggestive of Functional Prestige?

In order to address RQ1a and RQ1b, which target the degree to which participants have acquired attitudinal patterns suggestive of ‘functional prestige’ of standard German and dialect varieties, we make use of Bayesian hypothesis testing. Attitudinal behavior consistent with functional prestige would need to be observed on two fronts, which we have operationally defined in the form of two hypotheses, confluent with the two sub-research questions:

- H1. The dialect-speaking salesperson is judged as more friendly than the standard German-speaking salesperson (i.e., dialect is perceived as more friendly in a solidarity-stressing context than is the standard German variety).

- H2. The standard German-speaking doctor is judged as more intelligent than the dialect-speaking doctor (i.e., standard German is perceived as more intelligent in a status-stressing context than is the dialect variety).

Using the posterior distributions of the conditional effects (i.e., the distributions visualized in Figure 3), we can compare the relevant conditions to directly calculate the probability that the aforementioned two facets of functional prestige are met.

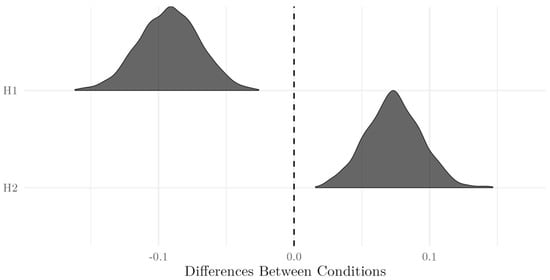

Figure 4 shows the results of the two Bayesian hypothesis tests. H1 visualizes the difference between L2 speakers’ friendliness ratings of the dialect-speaking salesperson and standard German-speaking salesperson. H2 illustrates the difference between L2 speakers’ intelligence ratings of the standard German-speaking doctor and the dialect-speaking doctor. Positive values on the x-axis indicate evaluative judgement patterns consistent with functional prestige (H1: the dialect is rated more positively in terms of friendliness; H2: standard German is rated higher in terms of intelligence), whereas negative values suggest rating patterns inconsistent with functional prestige (H1: standard German is rated more positively in terms of friendliness; H2: the dialect is rated more positively in terms of intelligence). Note that these are difference distributions: Higher and steeper peaks indicate more probable values for the difference between the two respective conditions. When the difference distribution does not overlap with zero, the difference between conditions can be interpreted as significant.

Figure 4.

Posterior distributions displaying the probability density of differences between conditions in the computed hypotheses. H1: varietal differences between friendliness ratings of the salesperson; H2: varietal differences between intelligence ratings of the doctor. Distributions not including zero indicate a significant difference between conditions.

Regarding H1, the difference between L2 speakers’ friendliness ratings of the dialect- and standard German-speaking salesperson is significant, but in the opposite direction of the specified hypothesis (median δ = −0.09, HDI = [−0.14, −0.05], P(δ > 0) = 0%). In other words, participants rated the standard German-speaking salesperson as more friendly than the dialect-speaking one. Conversely, H2 holds true, in that participants judged the standard German-speaking doctor as more intelligent than the dialect-speaking one (median δ = 0.07, HDI = [0.03, 0.11], P(δ > 0) = 99.98%).

4.2. To What Extent Does Self-Reported Proficiency Predict the Acquisition of Attitudinal Patterns Suggestive of Functional Prestige?

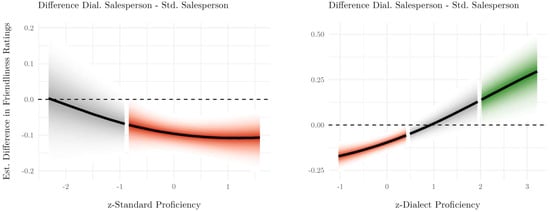

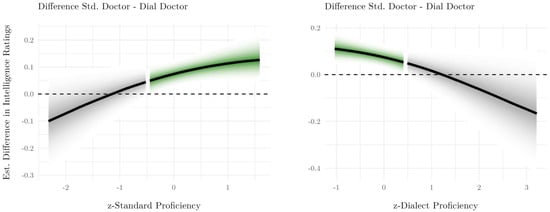

As a next step, visual methods for significance testing allow us to see where and in what ways participants’ acquisition of attitudinal behavior confluent with the notion of functional prestige differs as a function of varietal proficiency. In the same way as described above, we computed differences between conditions that would be indicative of the acquisition of evaluative judgements reflective of functional prestige and checked whether the differences in question become more or less pronounced with higher or lower self-reported varietal proficiency (i.e., proficiency in standard German and in the Austro-Bavarian dialect). The results from this procedure are shown in Figure 5 and Figure 6. The shading represents the predicted credible intervals. Green shading indicates a significant difference (i.e., the 95% HDI of the estimated difference does not include zero) in the direction consistent with functional prestige (e.g., the dialect-speaking salesperson is rated higher in terms of friendliness than the standard German-speaking salesperson), and red shading a significant difference in the opposite direction.

Figure 5.

Difference plots visualizing the estimated differences in varietal friendliness ratings. These difference plots illustrate the estimated differences in varietal friendliness ratings between the dialect-speaking salesperson and standard German-speaking salesperson (y-axis, positive values indicate that the dialect-speaking salesperson was rated higher in terms of friendliness) as a function of standard German and dialect proficiency (x-axis). Red and green shading indicates that the 95% HDI of the estimated difference does not include zero (i.e., the difference in the compared evaluative judgements is statistically significant), and grey shading indicates no significant difference. Darker shading in the respective color indicates more probable values.

Figure 6.

Difference plots visualizing the estimated differences in varietal intelligence ratings. These difference plots illustrate the estimated differences in varietal intelligence ratings between the standard German-speaking doctor and dialect-speaking doctor (y-axis, positive values indicate that the standard German-speaking doctor was rated higher in terms of intelligence) as a function of standard German and dialect proficiency (x-axis). Green shading indicates that the 95% HDI of the estimated difference does not include zero (i.e., the difference in the compared evaluative judgements is statistically significant), and grey shading indicates no significant difference. Darker shading in the respective color indicates more probable values.

With respect to the friendliness ratings, Figure 5 illustrates that L2 speakers with higher dialect proficiency (that is, approximately 2 SDs above the mean, translating to a self-reported dialect score of 54/100) rate the dialect-speaking salesperson higher. Conversely, individuals with average and below-average dialect proficiency rate the standard German-speaking salesperson higher in terms of friendliness. What is more, individuals across nearly all standard German proficiency levels seem to attribute the standard German-speaking salesperson higher friendliness ratings.

Figure 6 illustrates that individuals with average and above-average standard German proficiency (i.e., above approximately 60/100) and also average and below-average dialect proficiency (i.e., below approximately 24/100) rate the standard German-speaking doctor as more intelligent.

5. Discussion

The overarching goal of the present study was to provide a snapshot analysis of the extent to which individuals with L2 German living in the Bavarian-speaking parts of Austria acquire attitudinal patterns suggestive of ‘functional prestige’ of standard German and dialect varieties (i.e., more positive attitudes towards the dialect variety in terms of friendliness in solidarity-stressing settings and more positive attitudes towards the standard German variety in terms of intelligence in status-stressing contexts) and whether self-reported varietal proficiency predicts the acquisition of attitudinal behavior consistent with the concept of functional prestige. On the whole, our results support previous findings by Kaiser et al. (2019) indicating that L2 speakers attribute more critical evaluations to the dialect as compared to the standard German variety, notably both in terms of friendliness and intelligence judgements. Additionally, the findings support Kaiser et al.’s (2019, p. 359, our translation) hypothesis that L2 speakers “sometimes evince independent socio-indexical interpretations that also differ from L1 speakers.” Specifically, Bayesian modeling and hypothesis testing facilitated compelling evidence against the assumption that L2 speakers replicate indexical interpretations of variation represented by target-language speakers in the Austro-Bavarian setting (see, e.g., Bellamy, 2012; Kaiser et al., 2019; Soukup, 2009), although there is a certain multidimensionality at play here.

As we see it, the fact that participants at the group level attribute the standard German-speaking salesperson higher friendliness judgements as opposed to the dialect-speaking salesperson may be a manifestation of ‘transformation under transfer’, that is, “the reallocation of the relative importance of variable input constraints in the output variation” (Meyerhoff & Schleef, 2012, p. 405). In other words, constraints typical of the target-language community and suggestive of functional prestige as concerns the subjective indexical element of solidarity were reversed at the inter-individual level. Arguably, this reallocation of constraints may also be a consequence of the increased perceptual difficulty of Austro-Bavarian dialect varieties. The analysis bringing varietal proficiency into the picture consolidates this interpretation, revealing that only participants with low dialect proficiency (and with standard German proficiency of varying levels) rated the standard German-speaking salesperson higher in terms of friendliness. Conversely, L2 speakers with higher dialect proficiency do not seem to evince the same transformation under transfer patterns as those with low dialect proficiency, likely because the confounding nature regarding the perceptual difficulty of Austro-Bavarian dialect varieties disappears or is at least mitigated.

On the other side of the coin, the L2 speakers in this sample indeed displayed seemingly potential indicators of functional prestige of the standard German variety on the indexical domain of status, that is, higher evaluations of standard varieties when intelligence and education are in the contextual foreground, by judging the standard German-speaking doctor as more intelligent than the dialect-speaking one. That said, we are hesitant to interpret these findings as evidence of partial acquisition of attitudinal behavior reflective of functional prestige. This is because the standard German variety was, at least as the group-level tendencies indicated, judged higher cross-contextually and on both the indexical domain of status and solidarity. L2 speakers’ preference for the standard language variety appears to be a comparatively robust finding, both in perception and production data. For instance, Ender et al. (2017) identified that adolescent L2 speakers in Austria provide overall more favorable judgements of standard-language speakers, and Wirtz et al. (2024) highlighted that adult L2 speakers of German produce primarily standard language variants. In light of this, what we are observing is likely not some form of limited acquisition of attitudes confluent with the notion of functional prestige, bounded to the standard German variety and indexical dimension of status, but rather a reflection of how increased perceptual difficulty of Austro-Bavarian dialect varieties for L2 speakers of German influences their respective evaluative judgement patterns, as also noted above.

The findings from the analysis of individual differences in varietal proficiency further consolidate this interpretation. Here, we found no significant differences between the intelligence judgements of the standard German- and dialect-speaking doctor for individuals with (above-)average dialect proficiency. Rather than acquiring only select facets of attitudinal behavior reflective of functional prestige, then, it would seem that as the perceived perceptual difficulty of the Austro-Bavarian dialect decreases (as a result of increased dialect proficiency), so too does the preference for standard German over the dialect. This finding highlights the critical link between language attitudes and linguistic practice. Specifically, is has been asserted that the degree of correlation between linguistic behavior and variant or variety preference is not a mere question of frequency or intensity of exposure but rather a matter of “whether or not native speaker conventions align with learners’ own social identities and orientations to language learning” (van Compernolle & Williams, 2012, p. 246). In other words, L2 speakers’ use of (in-)formal variants is closely intertwined with their personal relationship with prescriptive versus informal (or innovative) forms, with their willingness or refusal to align to the respective target-language speaker conventions, and, more generally, with their ultimate goals in SLA (see also, e.g., Ender, 2017; Ender et al., 2023; Kinginger, 2008; Regan, 2013, 2022; Wirtz et al., 2024).

To summarize the findings regarding the two research questions, that is, (a) whether individuals with L2 German in Austria acquire attitudinal patterns suggestive of functional prestige in the same way as L1/expert speakers of German in Austria and (b) whether the acquisition of evaluative judgements reflective of functional prestige is conditioned by variation in varietal proficiency, the short answer to both questions is no. At the inter-individual level, participants rate the standard German variety more positively overall. Granted, this effect becomes more nuanced when considering individual differences in varietal proficiency, such that individuals with above-average dialect proficiency seem to rate dialect varieties more positively in general, a finding that is confluent with Ender (2020). That said, higher dialect proficiency does not seem to be associated with L2 speakers’ acquisition of attitudinal patterns suggestive of functional prestige. This is because, while individuals highly proficient in the dialect variety rated the dialect-speaking salesperson higher in terms of friendliness, they did not rate the standard German-speaking doctor higher with respect to intelligence: in fact, L2 speakers with high dialect proficiency even tended to rate the dialect-speaking doctor higher, although the difference was not statistically significant. In other words, the L2 acquisition of the socio-situational constraints on variation that would give rise to evaluative judgement patterns consistent with functional prestige is not given at the group level and also does not seem to be predicted by individual differences in varietal proficiency.

Content-wise, the current study is, in part, also an answer to Wirtz’ (in press) call to investigate a larger, more heterogeneous sample of L2 learners of German in terms of their evaluative judgements (see also Long, 2022) and also Kaiser et al.’s (2019) request to increase the sample size of L2 speakers considered so as to more wholly capture the attitudinal tendencies of L2 speaker populations in the Austrian setting. We suggested earlier that the results in Wirtz (in press), who found in his sample of 40 speakers of L2 German with L1 English that participants indeed demonstrated attitudinal behavior consistent with that of target-language speakers, may be a result of sociolinguistic transfer, given that English-speaking sociodialectal landscapes often house similar indexical interpretations of standard and nonstandard varieties/variants in terms of solidarity and status as in the Austro-Bavarian setting. The findings at hand allude to evidence that, indeed, Wirtz (in press) was likely capturing mechanisms of sociolinguistic transfer from L1 English, which would explain the discrepancies between his participant pool and the one at hand. In this spirit, his sample was subject to a different ‘starting point’ in terms of evaluative judgements than are speakers of L2 German with other L1s and, thus, different social categorizations of variation in their respective L1 speech communities. Given the heterogeneity of L1s in the present sample, however, an L1-specific analysis of potential sociolinguistic transfer effects was not possible but presents an interesting and worthwhile avenue for future research (see also Ender, 2021). A similar argument can be made above and beyond the scope of differences in the L1. Specifically, while the analyses did not differentiate between culture, ideologies, personal experience with language variation, etc., future research should strive to more concretely operationalize sample diversity among L2 speakers.

6. Conclusions and Future Directions

The Austro-Bavarian landscape is characterized not only by sociolinguistic variants but also entire sociolinguistically functional varieties/codes, for example, standard German and Bavarian dialect varieties. Along these lines, German is regarded as a language with a particularly extravagant range of variation (Barbour & Stevenson, 1998). In the context of additional language learning, this breadth of sociolinguistic variation does not come without challenges (Ender, 2022; Wirtz, in press). In order to successfully participate in social, commercial, and academic interactions, L2 speakers must learn to understand, interpret, and decode subtle indicators of social and socio-contextual information communicated via sociolinguistic variation (Ender et al., 2017; Ender, 2020; Kaiser et al., 2019; Chappell & Kanwit, 2022). The present study explicitly explored whether speakers of L2 German living in Austria acquire attitudinal patterns suggestive of functional prestige, that is, whether they (a) judge the dialect higher in terms of friendliness in a solidarity-stressing situation and (b) attribute the standard variety a higher indexical value in terms of intelligence in a status-stressing setting. We also addressed the issue as to whether the acquisition of attitudes reflective of functional prestige may be conditioned by individual differences in varietal proficiency (i.e., proficiency in standard German and the Austro-Bavarian dialect), especially seeing as variation in dialect proficiency has been found to be a strong predictor of variation in evaluative judgements (e.g., Ender, 2020; Chappell & Kanwit, 2022).

Our findings provide initial evidence that speakers of L2 German in Austria do not seem to acquire the socio-situational constraints on variation that would give rise to evaluative judgement patterns consistent with functional prestige. At the group level, Bayesian multilevel modeling indicated that L2 speakers tend to rate standard German varieties more positively, both in terms of intelligence and friendliness. Individual differences in varietal proficiency do, however, seem to impact variation in L2 speakers’ evaluative judgements. For example, whereas the group-level analysis illustrated that the standard German-speaking salesperson was rated higher in terms of friendliness, the model integrating varietal proficiency indicated that individuals with above-average dialect proficiency judged the dialect-speaking salesperson as more friendly. That said, while varietal proficiency seems to be related to apparent preferences for a variety (e.g., individuals with high dialect proficiency appear to prefer dialect varieties, regardless of the indexical domain, and vice versa), it did not predict the acquisition of attitudinal patterns suggestive of functional prestige more generally.

As with any cross-sectional study, this snapshot portrait of inter-individual tendencies is to be taken with a grain of salt. As Lowie and Verspoor (2019, p. 203) maintain, group studies such as this can “give us valuable information about the relative weight of individual factors that may play a role in L2 development,” but are not necessarily “representative for a longer period of time and cannot predict much about any individual’s behavior at any point in time.” So, while the Bayesian multilevel modeling approach used here can neutralize individual variation within the group and, thus, “allow for adequate generalizations in the frequency domain, such generalizations are not warranted in the time domain” (Pfenninger, 2021, p. 12; see also Lowie & Verspoor, 2015). Along these lines, Wirtz and Pfenninger (2024) and Ender et al. (2023) underscore the dynamic nature and the influence of individual beliefs on attitudinal development and the range of contextual and socio-affective factors that play a role in the development of sociolinguistic evaluative judgements. While our results in the present study indeed suggest that L2 speakers do not adopt target-like attitudinal patterns, it is yet comparatively understudied how attitudinal preferences develop at the individual level over time and which factors may contribute to these changes. In light of this, we require more studies exploring the intra-individual variability (i.e., change over time) of evaluative judgements (see also Geeslin & Schmidt, 2018) in the Austro-Bavarian context and beyond.

Finally, it was notable that neither age of onset of acquisition nor length of residence in the target-language community were significant predictors of differences in learners’ evaluative judgements, a finding which indeed runs counter to previous conclusions about learners’ sociolinguistic perception drawn on the basis of L2 learners of Spanish (e.g., Chappell & Kanwit, 2022) and English (e.g., Davydova et al., 2017). While it is acknowledged that L2 learners only very rarely achieve L1-like patterns of sociolinguistic variation, even with substantial exposure to the target-language community (e.g., Howard et al., 2013), widening the range of individual differences may represent a useful step forward in variationist SLA to more clearly ascertain potential rationales for convergence to or divergence from target-like patterns of variation. For example, this study considered a diverse sample of participants in terms of L1s and socioeconomic backgrounds, all of whom had migrated to the Austro-Bavarian context, although likely for different reasons. As previous SLA research has shown, differences in migratory experience may help in explaining language acquisitional outcomes (e.g., Forsberg Lundell & Bartning, 2015), and Diskin and Regan (2015) have demonstrated that differences in learners’ rationales for migrating to a certain host community may affect their acquisition of variable structures (e.g., discourse–pragmatic features). In addition to developing methods to tease apart the effects of differences in migratory experience on SLA, future research may consider accounting for individual differences in psycho-social variables as well, for example, personality traits, as these have repeatedly been found to correlate with L2 skills (e.g., Forsberg Lundell & Sandgren, 2013; Forsberg Lundell et al., 2018, 2023a, 2023b) and may, thus, feasibly correlate with learners’ differential ability to adopt and/or to attribute target-like indexical value to variable features of the target language.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A.W. and A.E.; methodology, M.A.W. and A.E.; formal analysis, M.A.W.; investigation, M.A.W. and A.E.; resources, A.E.; data curation, M.A.W. and A.E.; writing—original draft preparation, M.A.W. and A.E.; writing—review and editing, M.A.W. and A.E.; visualization, M.A.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the participants for taking the time to provide the data for this experiment, as well as the reviewers and editors of this special issue for their helpful comments on an earlier version of this manuscript. We also thank David Gschösser for proofreading the IPA transcriptions. Any remaining errors are, of course, our own.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Note that in German-speaking sociolinguistics, the term ‘dialect’ is used in the spirit of ‘local base dialect’ or ‘local vernacular’ and is not synonymous to ‘any language variety’. Additionally, we employ the term ‘Bavarian’ in its dialectological sense. It refers to eastern varieties of Upper German, which are spoken in most parts of Austria. |

| 2 | For more detailed information about the strengths of Bayesian data analysis over Frequentist methods, the interested reader is referred to McElreath (2015) as well as to Vasishth et al. (2018), Franke and Roettger (2019), and Garcia (2021) for tutorials on Bayesian inferential statistics geared towards the language sciences. For conceptual advantages of Bayesian analysis in sociolinguistics and SLA, we refer readers to Gudmestad et al. (2013) and Wirtz and Pfenninger (2023). |

References

- Barbour, S., & Stevenson, P. (1998). Variation im deutschen. soziolinguistische perspektiven. de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Bellamy, J. (2012). Language attitudes in England and Austria: A sociolinguistic investigation into perceptions of high and low-prestige varieties in Manchester and Vienna. Franz Steiner Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Bürkner, P. -C. (2017). Brms: An R package for Bayesian multilevel models using stan. Journal of Statistical Software, 80(1), 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappell, W., & Kanwit, M. (2022). Do learners connect sociophonetic variation with regional and social characteristics?: The case of L2 perception of Spanish aspiration. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 44(1), 185–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, L., & Schleef, E. (2010). The acquisition of sociolinguistic evaluations among Polish-born adolescents learning English: Evidence from perception. Language Awareness, 19(4), 299–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coupland, N., & Bishop, H. (2007). Ideologised values for British accents. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 11(1), 74–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davydova, J., Tytus, A., & Schleef, E. (2017). Acquisition of sociolinguistic awareness by German learners of English: A study in perceptions of quotative be like. Linguistics, 55(4), 783–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diskin, C., & Regan, V. (2015). Migratory experience and second language acquisition among polish and Chinese migrants in Dublin, Ireland. In F. F. Lundell, & I. Bartning (Eds.), Cultural migrants and optimal language acquisition (pp. 137–77). Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Dossey, E., Clopper, C. G., & Wagner, L. (2020). The development of sociolinguistic competence across the lifespan: Three domains of regional dialect perception. Language Learning and Development, 16(4), 330–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragojevic, M. (2017). Language attitudes. In H. Giles, & J. Harwood (Eds.), Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Communication (pp. 1–30). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Durrell, M. (1995). Sprachliche Variation als Kommunikationsbarriere. In H. Popp (Ed.), Deutsch als Fremdsprache. An den Quellen eines Faches. Festschrift für Gerhard Helbig zum 65. Geburtstag (pp. 417–428). Iudicium. [Google Scholar]

- Elspaß, S., & Kleiner, S. (2019). Forschungsergebnisse zur arealen Variation im Standarddeutschen. In J. Herrgen, & J. E. Schmidt (Eds.), Sprache und Raum. Ein internationales Handbuch der Sprachvariation (pp. 159–184). de Gruyter. Handbücher zur Sprach- und Kommunikationswissenschaft 30.4, vol. 4: Deutsch. Unter Mitarbeit von Hanna Fischer und Brigitte Ganswindt. [Google Scholar]

- Ender, A. (2017). What is the target variety? The diverse effects of standard–dialect variation in second language acquisition. In G. De Vogelaer, & M. Katerbow (Eds.), Acquiring Sociolinguistic Variation (pp. 155–184). Benjamins. Studies in Language Variation 20. [Google Scholar]

- Ender, A. (2020). Zum Zusammenhang von Dialektkompetenz und Dialektbewertung in Erst-und Zweitsprache. In M. Hundt, A. Kleene, A. Plewnia, & V. Sauer (Eds.), Regiolekte. Objektive Sprachdaten und subjektive Sprachwahrnehmung (pp. 77–102). Narr Francke Attempto Verlag. Studien zur deutschen sprache 25. [Google Scholar]

- Ender, A. (2021). The standard-dialect repertoire of second language users in German-speaking Switzerland. In A. Ghimenton, A. Nardy, & J. -P. Chevrot (Eds.), Sociolinguistic variation and language acquisition across the lifespan (pp. 251–75). John Benjamins. Studies in language variation 26. [Google Scholar]

- Ender, A. (2022). Dialekt-Standard-Variation im ungesteuerten Zweitspracherwerb des Deutschen. Eine soziolinguistische Analyse zum Erwerb von Variation bei erwachsenen Lernenden. De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Ender, A., Kasberger, G., & Kaiser, I. (2017). Wahrnehmung und Bewertung von Dialekt und Standard durch Jugendliche mit Deutsch als Erst-und Zweitsprache. ÖDaF-Mitteilungen, 33(1), 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ender, A., Kasberger, G., & Wirtz, M. A. (2023). Standard-und Dialektbewertungen auf den Grund gehen: Individuelle Unterschiede und subjektive Theorien hinsichtlich Dialekt-und Standardaffinität bei Personen mit Deutsch als Zweitsprache im bairischsprachigen Österreich. Zeitschrift für Deutsch im Kontext von Mehrsprachigkeit, 1(2), 8–25. Available online: https://www.vr-elibrary.de/doi/abs/10.14220/odaf.2023.39.1.8 (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Forsberg Lundell, F., & Bartning, I. (2015). Introduction: Cultural migrants—Introducing a new concept in SLA research. In F. F. Lundell, & I. Bartning (Eds.), Cultural migrants and optimal language acquisition (pp. 1–16). Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Forsberg Lundell, F., & Sandgren, M. (2013). High-level proficiency in late L2 acquisition. Relationships between collocational production, language aptitude and personality. In G. Granena, & M. Long (Eds.), Sensitive periods, language aptitude, and ultimate L2 attainment (pp. 231–56). John Benjamins Publishing Company. Language learning & language teaching. [Google Scholar]

- Forsberg Lundell, F., Arvidsson, K., & Jemstedt, A. (2023a). The importance of psychological and social factors in adult SLA: The case of productive collocation knowledge in L2 Swedish of L1 French long-term residents. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 45(2), 558–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsberg Lundell, F., Arvidsson, K., & Jemstedt, A. (2023b). What factors predict perceived nativelikeness in long-term L2 users? Second Language Research, 39(3), 597–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franke, M., & Roettger, T. (2019). Bayesian regression modeling (for factorial designs): A tutorial. Available online: https://github.com/michael-franke/bayes_mixed_regression_tutorial/blob/master/text/bmr_tutorial.tex (accessed on 16 December 2024).

- Garcia, G. D. (2021). Data visualization and analysis in second language research. Routledge. Second Language Acquisition Research. [Google Scholar]

- Gawronski, B., Ye, Y., Rydell, R. J., & De Houwer, J. (2014). Formation, representation, and activation of contextualized attitudes. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 54(1), 188–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geeslin, K. L. (2018). Variable structures and sociolinguistic variation. In P. A. Malovrh, & A. G. Benati (Eds.), The handbook of advanced proficiency in second language acquisition (pp. 547–565). Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Geeslin, K. L., Gudmestad, A., Kanwit, M., Linford, B., Long, A. Y., Schmidt, L., & Solon, M. (2018). Sociolinguistic competence and the acquisition of speaking. In R. Alonso (Ed.), Speaking in a second language (pp. 1–26). John Benjamins. AILA applied linguistics series 17. [Google Scholar]

- Geeslin, K. L., & Long, A. Y. (2014). Sociolinguistics and second language acquisition. Learning to use language in context. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Geeslin, K. L., & Schmidt, L. B. (2018). Study abroad and L2 learner attitudes. In C. Sanz, & A. Morales-Front (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of study abroad research and practice (pp. 387–405). Routledge. New York. [Google Scholar]

- Gelman, A., Simpson, D., & Betancourt, M. (2017). The prior can often only be understood in the context of the likelihood. Entropy, 19(10), 555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles, H., & Powesland, P. F. (1975). Speech, style and social evaluation. Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gudmestad, A., House, L., & Geeslin, K. L. (2013). What a Bayesian analysis can do for SLA: New tools for the sociolinguistic study of subject expression in L2 Spanish. Language Learning, 63(3), 371–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, M., Mougeon, R., & Dewaele, J. -M. (2013). Sociolinguistics and second language acquisition. In R. Bayley, R. Cameron, & C. Lucas (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of sociolinguistics (pp. 340–359). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, I. (2006). Bundesdeutsch aus österreichischer Sicht. Eine Untersuchung zu Spracheinstellungen, Wahrnehmungen und Stereotypen. Institut für Deutsche Sprache. Amades. Arbeitspapiere und Materialien zur deutschen Sprache 2/06. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, I., Ender, A., & Kasberger, G. (2019). Varietäten des österreichischen Deutsch aus der HörerInnenperspektive: Diskriminationsfähigkeiten und sozio-indexikalische Interpretation. In L. Bülow, A. Fischer, & K. Herbert (Eds.), Dimensionen des sprachlichen Raums: Variation—Mehrsprachigkeit—Konzeptualisierung (pp. 341–362). Peter Lang Verlag. Schriften zur deutschen Sprache in Österreich 45. [Google Scholar]

- Kanwit, M., & Solon, M. (2023). Communicative competence in a second language: Theory, method, and applications. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanwit, M. (2022). Sociolinguistic competence: What we know so far and where we’re heading. In K. L. Geeslin (Ed.), The Routledge handbook of second language acquisition and sociolinguistics (pp. 30–44). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kinginger, C. (2008). Language learning in study abroad: Case studies of Americans in France. The Modern Language Journal, 92(1), 1–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutlu, E., Chiu, S., & McMurray, B. (2022). Moving away from deficiency models: Gradiency in bilingual speech categorization. Frontiers in Psychology, 13(1), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labov, W. (1966). The social stratification of English in New York city. Center for Applied Linguistics. [Google Scholar]

- Labov, W. (1972). Sociolinguistic patterns. University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert, W., Hodgson, R., Gardner, R. C., & Fillenbaum, S. (1960). Evaluational reactions to spoken language. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 60(1), 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levon, E., & Ye, Y. (2020). Language, indexicality and gender ideologies: Contextual effects on the perceived credibility of women. Gender and Language, 14(2), 123–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levon, E., Sharma, D., Watt, D. J. L., Cardoso, A., & Ye, Y. (2021). Accent Bias and Perceptions of Professional Competence in England. Journal of English Linguistics, 49(4), 355–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, A. Y. (2022). Commonly Studied Language Pairs. In K. L. Geeslin (Ed.), The Routledge handbook of second language acquisition and sociolinguistics (pp. 420–432). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Lowie, W. M., & Verspoor, M. H. (2015). Variability and variation in second language acquisition orders: A dynamic reevaluation. Language Learning, 65(1), 63–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowie, W. M., & Verspoor, M. H. (2019). Individual differences and the ergodicity problem. Language Learning, 69(S1), 184–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundell, F. F., Eyckmans, J., Rosiers, A., & Arvidsson, K. (2018). Is multicultural effectiveness related to phrasal knowledge in English as a second language? International Journal of Applied Linguistics and English Literature, 7(2), 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lyster, R. (1994). The effect of functional-analytic teaching on aspects of French immersion students’ sociolinguistic competence. Applied Linguistics, 15(1), 263–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McElreath, R. (2015). Statistical rethinking. A Bayesian course with examples in R and stan. Chapman and Hall/CRC. [Google Scholar]

- Meyerhoff, M., & Schleef, E. (2012). Variation, contact and social indexicality in the acquisition of (Ing) by teenage migrants. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 16(3), 398–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalski, I. M. (2021). The sociolinguistic perception of stylistic variation in a second language: Learner attitudes toward four variable structures of Spanish [Ph.D. Dissertation, Indiana University]. [Google Scholar]

- Moosmüller, S. (1991). Hochsprache und Dialekt in Österreich: Soziophonologische Untersuchungen zu ihrer Abgrenzung in Wien, Graz, Salzburg und Innsbruck. Böhlau. [Google Scholar]

- Mougeon, R., Nadasdi, T., & Rehner, K. (2010). The sociolinguistic competence of immersion students. Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Pfenninger, S. E. (2021). About the INTER and the INTRA in age-related research: Evidence from a longitudinal CLIL study with dense time serial measurements. Linguistics Vanguard, 7(s2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preston, D. R. (2013). Language with an attitude. In J. K. Chambers, & N. Schilling (Eds.), The handbook of language variation and change (2nd ed., pp. 157–182). Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. (2020). R: A Language and environment for statistical computing. R foundation for statistical computing. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 16 December 2024).

- Regan, V. (2010). Sociolinguistic competence, variation patterns and identity construction in L2 and multilingual speakers. EUROSLA Yearbook, 10(1), 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regan, V. (2013). The bookseller and the basketball player: Tales from the French Polonia. In D. Singleton, V. Regan, & E. Debaene (Eds.), Linguistic and cultural acquisition in a migrant community (pp. 28–48). Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Regan, V. (2022). Variation, identity and language attitudes. In R. Bayley, D. R. Preston, & X. Li (Eds.), Variation in second and heritage languages (pp. 253–278). Benjamins. Studies in Language Variation 28. [Google Scholar]

- Regan, V., Howard, M., & Lemée, I. (2009). The acquisition of sociolinguistic competence in a study abroad context. Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, L. B. (2020). Role of Developing language attitudes in a study abroad context on adoption of dialectal pronunciations. Foreign Language Annals, 53(1), 785–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soukup, B. (2009). Dialect use as interaction strategy. A sociolinguistic study of contextualization, speech perception, and language attitudes in Austria. Braumüller. [Google Scholar]

- Stotts, G. P. (2014). L2 Spanish speakers’ attitudes toward selected features of peninsular and Mexican Spanish [Ph.D. dissertation, Brigham Young University]. [Google Scholar]

- Trudgill, P. (1972). Sex, covert prestige and linguistic change in the urban British English of Norwich. Language in Society, 1(1), 179–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trudgill, P., & Giles, H. (1978). Sociolinguistics and linguistic value judgements: Correctness, adequacy and aesthetics. In F. Coppieters, & D. L. Goyvaerts (Eds.), Functional studies in language and literature (pp. 167–190). Story-Scientia. [Google Scholar]

- Unterberger, E. (2024). Wertschätzung sprachlicher Variation. Eine Untersuchung zur Veränderbarkeit von Spracheinstellungen im Deutschunterricht. wbv Publikation. [Google Scholar]

- van Compernolle, R. A., & Williams, L. (2012). Reconceptualizing sociolinguistic competence as mediated action: Identity, meaning-making, agency. The Modern Language Journal, 96(2), 234–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasishth, S., Nicenboim, B., Beckman, M. E., Li, F., & Kong, E. J. (2018). Bayesian data analysis in the phonetic sciences: A tutorial introduction. Journal of Phonetics, 71(4), 147–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergeiner, P. C., Buchner, E., Fuchs, E., & Elspaß, S. (2019). Sprachnormvorstellungen in sekundären und tertiären Bildungseinrichtungen in Österreich. Zeitschrift für Dialektologie und Linguistik, 86(3), 284–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergeiner, P. C., Buchner, E., Fuchs, E., & Elspaß, S. (2021). Weil STANDARD verständlich ist und DIALEKT authentisch macht: Varietätenkonzeptionen im sekundären und tertiären Bildungsbereich in Österreich. In T. Hoffmeister, M. Hundt, & S. Naths (Eds.), Laien, Wissen, Sprache. Theoretische, methodische und domänenspezifische Perspektiven (pp. 417–442). De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Wirtz, M. A. Dynamics of L2 sociolinguistic development in adulthood. Multilingual Matters. in press.

- Wirtz, M. A., & Pfenninger, S. E. (2023). Variability and individual differences in L2 sociolinguistic evaluations: The GROUP, the INDIVIDUAL and the HOMOGENEOUS ENSEMBLE. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 45(5), 1186–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirtz, M. A., & Pfenninger, S. E. (2024). Signature dynamics of development in second language sociolinguistic competence: Evidence from an intensive microlongitudinal study. Language Learning, 74(3), 707–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirtz, M. A., Pfenninger, S. E., Kaiser, I., & Ender, A. (2024). Sociolinguistic competence and varietal repertoires in a second language: A study on addressee-dependent varietal behavior using virtual reality. Modern Language Journal, 108(1), 385–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfram, W., & Schilling-Estes, N. (2006). American English: Dialects and variation (2nd ed.). Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).