Abstract

This paper explores the integration of constructive type theory in the tradition of Martin Löf into Dynamic Syntax.

1. Introduction

Dynamic Syntax (DS) is a parsing oriented framework where syntax can be seen as the progressive growth of transparent semantic representations (Cann et al., 2005; Kempson et al., 2001). DS has been used in a variety of ways and has proven itself versatile enough to handle issues as diverse as morphosyntactic puzzles (Bouzouita, 2008; Chatzikyriakidis, 2010; Chatzikyriakidis & Kempson, 2011) and language variation all the way to ellipsis (Eshghi et al., 2015; Gregoromichelaki et al., 2011; Kempson et al., 2015, 2018) and full-blown dialogue modeling (Eshghi et al., 2012; Gregoromichelaki et al., 2011; Howes & Eshghi, 2017; Kempson et al., 2016; Purver et al., 2010). The original DS system had the ability to produce semantic representations in a logical language, which was based, in a number of ways, on Montagovian Semantics (Gallin, 2011; Montague, 1970), albeit with a twist. DS kept the simple-typed system found in Montague, included an extra type for situations (no intensional types are used in DS), but, most importantly, used the epsilon calculus for quantification (Cann et al., 2005; Kempson et al., 2001), a conscious move that enables all arguments to have lower types. The semantic bone of DS is totally orthogonal to the actual ACTION calculus, i.e., the mechanism that builds and populates binary trees, moves or halts the parsing process, checks the triggering points of lexical entries and accordingly allows these to be fired or not. In this sense, one can very well envision DS versions that encode different types of semantics. Indeed, this has already been tried out with both Cooper’s Type Theory with Records Cooper (2005, 2012); Eshghi et al. (2012); Purver et al. (2010); Ranta and Cooper (2004), as well as vector-based semantics Purver et al. (2021); Sadrzadeh et al. (2018).

In this paper, I attempt an integration of constructive, dependent type semantics in DS. I will present some potential benefits including type many-sortedness and the use of dependent typing, discussing two main test cases, quantification and modification. With regard to the first, I will present an account where existential quantification is captured using types, where the first projection coercion of the construction allows us to keep the lower type e, while for universal quantification using , the quantifier is seen as a polymorphic functor over A predicates. Lastly, I discuss modification in DS, showing that some first steps towards a more general account of modification in DS can be proposed.

2. Why Martin-Löf’s Type Theories?

I argue that there are at least two good reasons that one would choose Martin-Löf type theories (MLTT) over mainstream Montagovian semantics:

- Expressivity;

- Solid proof-theoretic underpinnings.

The former refers to the rigidity of simple type theory mainly used in mainstream semantics. There, two basic types are introduced (three in case one takes the intentional type to be a basic type) along with their function types (Gallin, 2011; Montague, 1970). MLTTs are multi-sorted type systems and also include additional and more elaborate typing constructors like, for example, dependent types. We will not delve deeper into the discussion on the need for richer typing, but it suffices to say that there are at least some phenomena that are impossible to capture in a system equipped with basic types and no extra constructors. As Chatzikyriakidis et al. (2025) argue, the semantics of copredication and counting cannot be fully captured in a simple type theoretic framework, and they argue for richer type semantics.

The second reason concerns the proof-theoretic nature of MLTTs and thus their ability to be used as effective reasoners. Indeed, variants of MLTT are implemented by computer scientists in proof-assistants, notably in Coq, Lean and Agda, and these assistants, besides being used to formalize mathematics and other types of formal verification, have also been used to encode various aspects of NL semantics (Ranta & Cooper, 2004).

In what follows, we attempt the integration of MLTT-style semantics, specifically the version that Luo and colleagues call MTT-semantics, in Dynamic Syntax. I will show how such integration can proceed, in order to incorporate the rich features of MLTT-semantics into the DS action calculus, in effect giving DS an MLTT backbone.

But before we proceed with this endeavor, we first need an introduction to MLTT-semantics that highlights its most important aspects.

3. MLTT-Semantics: Preliminaries

MLTTs belong to a class of type theories based on Martin-Löf (Martin-Löf, 1975, 1984) that have dependent types and inductive types, among others. In MLTT-semantics, interpreting various linguistic categories can deviate from standard Montagovian assumption as shown below in Table 1:

Table 1.

Examples in formal semantics.

In MTT-based semantics, the basic ways to interpret various linguistic categories are as follows:

- Sentences (S) are interpreted as propositions of type Prop.

- Common nouns (CN) may be interpreted as types.

- Verbs (IV) may be interpreted as predicates over the type D that interprets the domain of the verb (i.e., a function of type D → Prop).

- Adjectives (ADJ) may be interpreted as predicates over the type that interprets the domain of the adjective (i.e., a function of type D → Prop).

- Modified common nouns (MCNs) may be interpreted by means of -types.

3.1. Common Nouns as Types and Type Many-Sortedness

MLTT-based formal semantics differs fundamentally from Montague semantics in how common nouns (CNs) can be interpreted. This difference arises from MLTTs being essentially ‘many-sorted’ logical systems.

Montague semantics Montague (1970) employs Church’s simple type theory (Church, 1940), which operates as a ‘single-sorted’ system. Only one type e exists for all entities. Types such as t for truth values and function types constructed from e and t do not denote entity types. Hence, no fine-grained distinctions exist between type e elements, and all individuals use identical type interpretation. John and Mary, for example, both have type e in simple type theories. MLTTs, however, being ‘many-sorted’ logical systems, can contain numerous types. MLTT-based semantics can therefore distinguish between individuals and employ different types to interpret individual subclasses. For instance, we may have and , where and are distinct types. Thus, a significant characteristic of MLTT-based semantics is their ability to interpret common nouns (CNs) as types Ranta (1994) rather than sets or predicates (i.e., objects of type ) as in Montague semantics. The CNs man, human, table and book are interpreted as types , , and , respectively. Individuals are then interpreted as belonging to one of the types used to interpret CNs.

Modified common nouns (MCNs in Table 1) receive interpretation through -types, which are types of dependent pairs. For instance, ‘handsome man’ receives interpretation as the type , the type of pairs consisting of a man and proof that the man is handsome.

This many-sortedness (i.e., the existence of numerous types in an MLTT) produces the welcome result that semantically infelicitous sentences like, e.g., the ham sandwich walks, which are syntactically well-formed, receive easy explanation. A verb like walks will be specified as having type , while the type for ham sandwich will be or , which is incompatible with the typing for walks:1

The interpretation of CNs as types rather than predicates has significant methodological implications: this approach is compatible with various subtyping relations one may consider in formal semantics. For instance, in modeling certain linguistic phenomena semantically, one may introduce various subtyping relations by postulating a collection of subtypes (physical objects, informational objects, eventualities, etc.) of the entity type Asher and Luo (2012). Now, if CNs receive interpretation as predicates as in the traditional Montagovian setting, introducing such subtyping relations would cause difficult problems: even basic semantic interpretations would fail, and dealing with some linguistic phenomena such as copredication satisfactorily becomes very difficult (Sutton, 2022). Instead, if CNs receive interpretation as types, as in type-theoretical semantics based on MTTs, copredication receives straightforward and satisfactory treatment (Chatzikyriakidis & Luo, 2020).

| (1) | a. the ham sandwich: food |

| b. walk : human → Prop |

Coercive Subtyping and Local Coercions

Coercive subtyping is an elaborate subtyping mechanism for MLTT, according to which A is a (proper) subtype of B () if there is a unique implicit coercion c from type A to type B, and, if so, an object a of type A can be used in any context that expects an object of type B: to be legal (well-typed) and equal to .

To give an example, assume that both and are base types. One may then introduce the following as a basic subtyping relation:

Now, coercive subtping in combination with the notion of context in MLTT can be used to introduce local subtyping relations when needed. This mechanism is used in the case of classic meaning transfer cases like the ham sandwich shouts. There, the idea is that one can introduce subtyping relations that are only valid in a local context. The context can furthermore be extended to involve subtyping declarations of the following form:

In the above, the type ham is coerced into type human in this particular setting via subtyping. The range of coercions we can perform can get more-fine grained as it has been exemplified, for example, in the work of Asher and Luo (2012). Note that this notion of logical coercion via subtyping is different than the usual notion of coercion as we find it in the linguistic semantics literature. In what follows, when we use the term, we mean this logical version of coercion that is tied to the subtyping mechanism.

| (2) |

| (3) |

3.2. -Types, -Types and Universes

3.2.1. Dependent -Types

A fundamental feature of MTTs is the employment of dependent types. A dependent type constitutes a family of types that depend on certain values.

The constructor/operator constitutes a generalization of the Cartesian product of two sets that allows the second set to depend on values of the first. For instance, if is a type and , then the -type is intuitively the type of humans who are male.

More formally, if A is a type and B is an A-indexed family of types, then , sometimes written as , is a type, consisting of pairs such that a is of type A and b is of type . When is a constant type (i.e., always the same type no matter what x is), the -type degenerates into product type of non-dependent pairs. -types (and product types) are associated with projection operations and so that and , for every of type or .

The linguistic relevance of -types can be directly appreciated once we understand that in its dependent case, -types can be used to interpret linguistic phenomena of central importance, like adjectival modification (Ranta, 1994). For example, handsome man is interpreted as -type ((4)), the type of handsome men (or more precisely, the type of those men together with proofs that they are handsome):

where is a family of propositions/types that depends on the type man(m).

| (4) |

The use of -types for dealing with adjectival modification will be further explained later on, when our proposal regarding the different classes of adjectives is going to be discussed.

3.2.2. Dependent -Types

-types function as a generalization of the standard function space where the second type constitutes a family of types that might depend on the first type’s values. In the non-dependent case, reduces to the function type .

More precisely, when A is a type and P is a predicate over A, is the dependent function type that, in the embedded logic, represents the universally quantified proposition .

proves very useful in formulating typings for numerous linguistic categories like VP adverbs or quantifiers. The concept is that adverbs and quantifiers range over the universe of (the interpretations of) CNs. is thus employed, universally quantifying over the universe . ((5-a)) shows the type for VP adverbs2 while ((5-b)) shows the type for quantifiers:

| (5) | a. | ΠA : CN.(A → Prop) → (A → Prop) |

| b. | ΠA : CN.(A → Prop) → Prop |

To better understand these typings, a few words about the notion of a universe are given as follows: informally, a universe constitutes a collection of (the names of) types assembled into a type (Martin-Löf, 1984). For example, one may wish to collect all the names of the types that interpret common nouns into a universe . The concept is that for each type A that interprets a common noun, there exists a name in . For example,

In practice, we do not distinguish a type in and its name by omitting the overlines and the operator by simply writing, for instance, . Thus, the universe includes the collection of the names that interpret common nouns. For example, in , one can find the following types:

where the -type in ((6-b)) is the proposed interpretation of ‘handsome man’ and the disjoint union type in ((6-c)) is the type election.3

| (6) | a. | man, woman, book, …; |

| b. | Σm : man.handsome(m); | |

| c. | ER + EF; |

The typings in ((5-a)) and ((5-b)) can now be explained. The type in ((5-b)) states that for all elements A of type , we obtain a function type . The concept is that the element A is now the type used. To illustrate how this operates, let us consider the case of quantifier some which has the typing in ((5-b)). The first argument we require must be of type . Thus, some human is of type given that the A here is (A becomes the type in ). Then, given a predicate like , we can apply some human to get .

Finally, and have been employed to deal with numerous problematic aspects of NL anaphora. Perhaps the most famous case is donkey anaphora. The concept is that we can make use of the projections of the to obtain donkey anaphora. Below is the interpretation of the classic donkey sentence using dependent typing:

The dependent sum type is a triple that corresponds to a man, a donkey and an ownership relation between the two. The dependent type then quantifies over all such triples. Finally, the projections and extract a man and donkey, respectively.

| (7) |

4. DS-MLTT

4.1. Preliminaries

The main idea behind our MLTT-DS system is to keep the DS ACTION calculus intact and substitute the standard Montagovian-like DS semantics with MLTT-semantics. Let us start. The first thing we can work on is type many-sortedness. DS, as in Montague semantics, uses a pretty much standard simple type system, with the exception being that type e also includes of situation types (situation entities to be more precise). There is also a type called , which, however, is a shorthand for an type. Starting with this notational similarity of this type, which will be notated in uppercase, will denote the universe of common noun types in our case. With this said, let us move to the parse of simple example in MLTT-DS. Let us tackle the sentence John loves Mary. The lexical entries for these words will be minimally different in the MLTT case, reflecting type many-sortedness:

| (8) | Lexical entry for Bill |

| IF | |

| THEN | |

| ELSE | abort |

The same minimal changes are needed in the lexical entry for the verb; for example, a verb like will project the formula value instead of . With this in place, let us move on to see whether we can successfully use dependent typing to deal with quantification.

4.2. and in Action: Existential and Universal Quantification

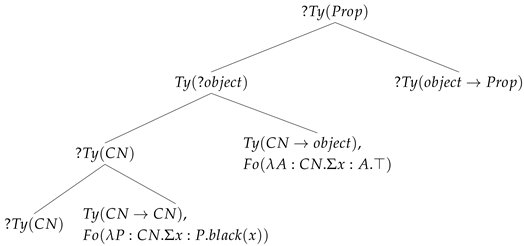

One of the idiosyncracies of DS is the use of the epsilon calculus in order to handle quantification. DS uses this mechanism, among other reasons, to keep the types of NPs lower (e) and, thus, have a uniform predicate–argument composition in that way (verbal elements are always the functors, NPs are always the arguments). What I want to show here is a way to do existential quantification using types that respect this lower typing that DS wants. Let us start. Say we want to parse the sentence a man walks. We start with the entry for the indefinite:

| (9) | Lexical entry for a |

| IF | |

| THEN | make(); go(); put(); |

| go(); make(); go(); | |

| put(Ty(), Fo()), go()() | |

| ELSE | abort |

The idea here is that the indefinite creates the CN node and the CN →object node. The type is the top type in the CN universe, meaning that all other types in the universe are its subtypes. In that node, the formula value is added. This basically creates a function requiring an A argument to create a dependent pair, where the first projection is the proof that x is an A and the second component is just the true proposition. Note that A is of type CN, the universe of common nouns. The next step is the entry for the common noun man:

| (10) | Lexical entry for man |

| IF | |

| THEN | |

| ELSE | abort |

The lexical entry for just contributes its type in the CN node (in effect, this is ). The lexical entry for walks is as follows:

| (11) | Lexical entry for walks |

| IF | |

| THEN | |

| ELSE | abort |

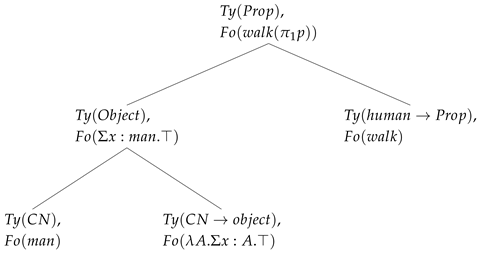

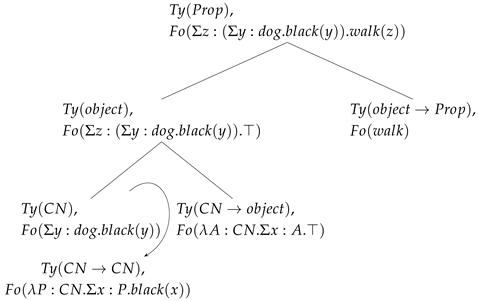

The requirement has a more general type that will be compatible with any type in the universe. The verb walks then contributes the type . Combining the and nodes will give us the formula . But this is of type . Indeed this is true, given that the is a subtype of its first projection, i.e., man, and man is a subtype of object which can thus be used in any environment that requires such a type. The end result is reflected in the tree below, where walks combines with the first projection of the dependent path:

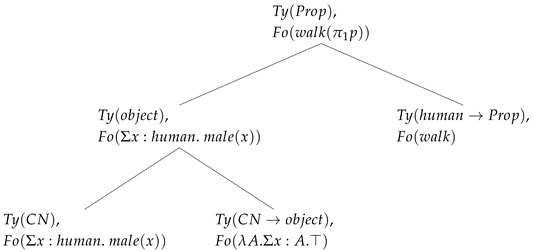

interpretation can also proceed via , i.e., instead of being base types, they are more elaborate types like, for example, types. For example, in the case of , we could have . In this case, what we would get is

Note that combining and gives that simplifies to . Also in both interpretations of CN, the end result is the same formula. However, in the second case, one can recover the fact that x is male via the second projection that says that there is proof p that x is male, while in the first case the second projection is just the truth placeholder.

| (12) |

|

| (13) |

|

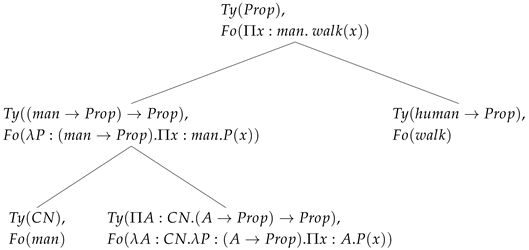

The nice thing about the use of is that we can still keep the DS intuition that NPs are of a lower type. In DS, this is maintained by using the epsilon calculus and operators for existential and universal quantification. In the case of existential quantification, this is possible with -types in our case as well. However, when we move to universal quantification using , this lower typing cannot be maintained. In MLTT-semantics, the universal quantifier is a polymorphic type with the following type:

Based on this, we assume the following lexical entry for every:

| (14) |

| (15) | Lexical entry for every |

| IF | |

| THEN | make(); go(); put(); |

| go(); make(); go(); | |

| put(Ty(), Fo()) | |

| ELSE | abort |

The crucial difference is in both the type and formula value: instead of and , respectively, what we have is and . In effect, what we get is a polymorphic function that takes a CN argument of type A and returns a generalized quantifier of type . Now, when every applies to man, we get the following:

- The CN node contributes

- The node contributes

- Applying the function:

This creates a generalized quantifier of type , which can then take walk as its argument.

| (16) |

|

| (17) |

|

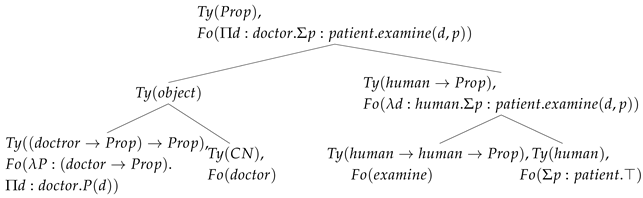

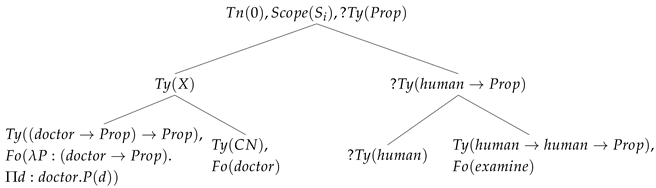

Scopal statements can be handled in the usual DS way shown in Cann et al. (2005) using scopal statements at the top node. For example, parsing every doctor examined will project a statement of scope on the top node:

| (18) |

|

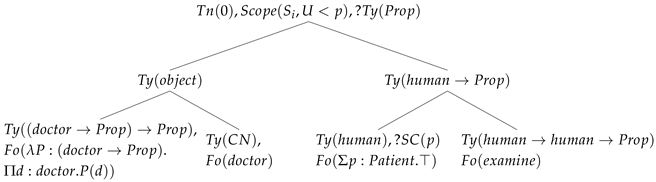

When a patient is processed, the indefinite creates an underspecified scope statement where the metavariable U can be resolved to different terms depending on whether narrow or wide scope is chosen. The indefinite also projects a scope requirement that must be satisfied:

| (19) |

|

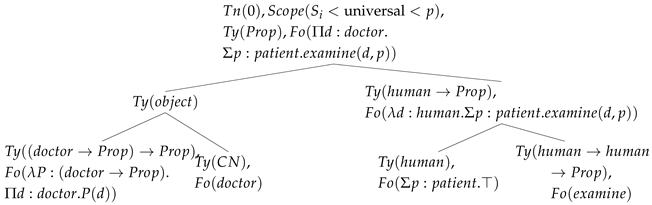

For the narrow scope reading, the metavariable U is resolved to the universal term already present in the structure, giving . This results in the scope statement , meaning the indefinite takes narrow scope relative to the universal quantifier. Function application then yields the final semantic result :

| (20) |

|

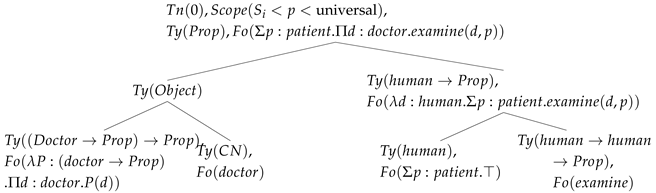

Alternatively, for the wide scope reading, the metavariable U is resolved to immediately upon processing the indefinite, giving . This results in the scope statement , meaning the indefinite takes wide scope over the universal quantifier. The same tree structure applies, but the scope statement determines that the final semantic result is :

| (21) |

|

What we did so far is as follows: in a way, we kept the intuition for lower typing for the case of existentials (as in the epsilon use for indefinites in the original DS treatment) and a higher-order typing for universals using types. To my knowledge, this is the first digression into a use where quantifiers are functors rather than arguments in DS (even though this is the standard in mostly all other formal semantics treatments). What we did here has further connections with the way existentials and universals have been shown to work. For example, going back to Reinhart (1997), choice functions and similar mechanisms (e.g., skolem functions) show that existentials take scope in different ways than universals. Here, I have shown a minimal account of scope in the traditional DS way of accounting for scope. However, the , assymetry of typing and the use of associated projections of might give rise to similar uses. Indeed, the connection between and choice/skolem functions is intriguing. For example acts like a choice function that picks a witness from the domain of patients. In the same sense, when , the behaves like a skolem constant. These are intriguing connections and we aspire to further elaborate on these in future work.

4.3. MLTT Contexts and Rerunning DS Actions

One of the powerful features of DS is its incremental, real-time, left-to-right processing that allows transparent semantic representations to be unfolded as a by-product of incremental parsing. DS has been shown to be very suitable for phenomena that go beyond the level of the sentence, notably ellipsis and dialogue phenomena. One very prominent feature of DS is the availability to rerun previous actions again. To give an example, consider the elliptical case of John loves Mary. George does too. The classic DS account of such elliptical cases involves the parser building a complete semantic tree for the first sentence, simultaneously recording all the parsing actions used in a dynamic DAG. When George does too is processed, the auxiliary projects a metavariable of type e → t that triggers a backwards search through the DAG. The sequence of actions that gave rise to the predicate loves Mary from the first sentence are identified and rerun this time at the elliptical sentence, and with George as the new subject. This rerun mechanism produces the desired interpretation George loves Mary without requiring any special ellipsis-specific machinery.

What I want to discuss here is the use of type-theoretic contexts as a means to record the history of parsing actions. In effect, TT contexts will be used to record the actions taken during the parsing process that drive incremental semantic growth. Ideally, we need a record of things like the lexical and computational actions used, the tree-building operations performed (node creation, pointer movement, type and formula decoration), and also, metavariable projections and resolutions/substitutions.

In Martin-Löf Type Theory (MLTT), contextsare finite sequences of variable declarations with their types, written as follows:

| (22) |

Contexts serve several crucial functions:

- Variable Binding: Each variable is bound with its type , which may depend on previously declared variables.

- Dependency Structure: Later types can refer to earlier variables, creating dependent types like and .

- Typing Judgments: All type-theoretic judgments are made relative to a context:

- Context Extension: New assumptions are added via context extension (provided ).

- Substitution: When we have and , we can substitute to get .

Contexts thus provide the foundational infrastructure for dependent typing, ensuring that all type dependencies are properly tracked and that substitution operations preserve well-typedness.

In this paper, we extend the standard MLTT notion of contexts to record not just semantic assumptions but the complete derivational history of DS parsing. Our DS-MLTT contexts take the following form:

where semantic assumptions are interleaved with action assumptions that record the parsing steps used to derive each semantic judgment. This allows us to treat action rerun as a formal operation on TT contexts, where we can extract and re-use action sequences. Let us exemplify the mechanism using the VP ellipsis example. But first, we need to define the basic Action types needed:

After parsing the sentence, we end up with the following context:

When the sentence is followed by George does too, the following happens. We start with INTRO and PREDICTION and parsing of George, and the pointer at the predicate node, then does comes into parse, projecting a predicate formula metavariable U:

This metavariable acts as a placeholder signaling that predicate content must be recovered from the prior discourse context .

| (23) |

| (24) | Basic Types: |

| (25) | DSAction as a Disjoint Union Type:5 |

| To give an example, consider the parse of the simple sentence John loves Mary. We start with the initial ?Ty(Prop) context: | |

| (26) | Initial Context: |

| (27) | Full DS-MLTT Context : |

| (28) | Parsing does |

At this point, too comes into parse and triggers a context rerun, filtering out the subject as follows:

| (29) | Lexical entry for too (simplified): |

| IF | |

| THEN | Run(, )) |

| ELSE | abort |

The filtering operation works as follows: we exclude all actions associated with building and populating the left daughter node at address (the subject position). Specifically, this removes actions from through in . The filtered context retains only the actions that constructed the predicate:

These remaining actions are rerun in the current tree where George occupies the subject position. The rerun rebuilds the predicate structure: loves projects its argument structure, Mary fills the object slot, and function application produces . The U metavariable is then substituted with this recovered predicate value, and COMPLETION plus ELIMINATION yield the final result .

4.4. Adjectives and Adverbs

In this last section, I want to discuss two issues that have not received enough attention in the DS literature: adjectives and adverbs. There is some work on adjectives as part of an analysis of polydefinites in Chatzikyriakidis (2015); Chatzikyriakidis and Spathas (2025), and also some general notes on adjectives and adverbs in Chatzikyriakidis (2017), but no attempt at a generalized account of these exist. What I will propose here is a way to use standard DS mechanisms with dependent typing in order to get a basic account of aspects of the syntax/semantics of adjectives and adverbs.

4.5. Adjectives

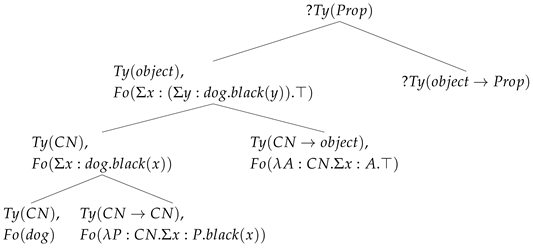

I am going to propose two mechanisms for adjectives: one that does not use LINK and projects adjectival semantics in the CN node, and one that uses LINK. Various adjectival constructions cross-linguistically seem to be requiring both as I will argue, e.g, regular adjectival modification vs polydefinites in Greek and stage- vs. individual-level readings in English. Let us start with a classic intersective adjective like black. The standard assumption in MLTT-semantics is that something like black dog involves a in effect, a dependent pair with the first projection being proof that an object is a dog, along with proof that it is black (given that it is a dog). Based on this, one can envision the following lexical entry for black in English:

| (30) | Lexical Entry for black: |

| IF | |

| THEN | make(); go(); put(); |

| go(); make(); go(); | |

| put(, ) | |

| ELSE | abort |

Parsing black will give us

| (31) | Parsing black |

| |

Then, dog is parsed, providing the noun type and combining with the polymorphic type to return . The ?Object node gets a type and a formula:

| (32) | After parsing dog |

| |

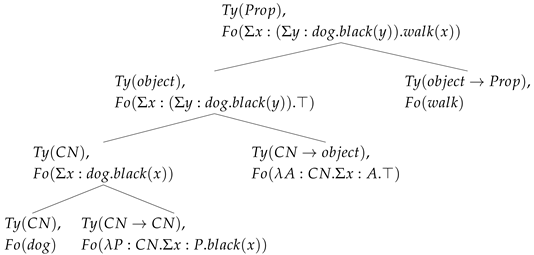

Walks comes into parse, combines with the subject node, and the parse is complete:

| (33) | After a black dog walks |

| |

Note that in the above, the ending formula is , since the first projection of the is a coercion (basically, we drop the ⊤ from the formula). In TTs where this does not hold, one needs to find a way to grab the first projection content. Of course, we need to repeat here that this exact mechanism is also the one that allows us to keep a lower type with types.

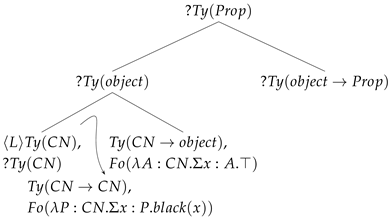

The other way to deal with adjectives and, in general, modifiers is via LINK. The difference here is that the adjective, instead of projecting its semantics into the main tree, initiates a LINK relation from the type ?CN node.

| (34) | After parsing black on a LINKed tree |

| |

After LINK evaluation gives us at the CN node, then ELIMINATION combines it with the determiner:

| (35) |

The verb comes into parse and everything works as expected from there on:

| (36) | |

| |

One thing that these two different ways of encoding adjectives offer us is that we can deal with some well-known differences in adjectival syntax cross-linguistically. For example, take the case of individual- vs. stage-level readings in English, i.e., the difference between the responsible people and the people responsible. In the first case, the property of being responsible is tightly knit into that specific subset of people, whereas in the second, it is situation-dependent. One can envision where the prenominal adjectives give the semantics we just discussed, and the postnominal is derived by LINK via a LINK evaluation rule that ties the semantics to a situation variable. Similar considerations apply to Greek polydefinites, recasting the account by Chatzikyriakidis and Spathas (2025) with MLTT-semantics.

Let me now say a few words on how adverbs can be incorporated in DS-MLTT. In terms of their semantics, the semantics of various types of adverbs have been dealt with in Chatzikyriakidis and Luo (2017) and the assumption that adverbs involve LINK relations.

| (37) | Lexical Entry for quickly: |

| IF | |

| THEN | make(); go(); |

| put(, | |

| ) | |

| ELSE | abort |

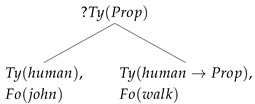

Now take the sentence John walks quickly. The first step is parsing the subject and verb:

| (38) | After John walks |

| |

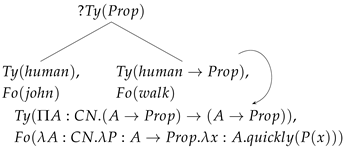

| (39) | After quickly is parsed |

| |

The adverb’s typing contains an A argument which is inferred from context. This is not unusual in type systems. In fact, we can assume that the A is an implicit argument, in the same sense one can declare implicit arguments in proof-assistants implementing MLTTs like Coq (The Coq Development Team, 2024). Given this type being implicit, the result of the tree after evaluation is as follows:

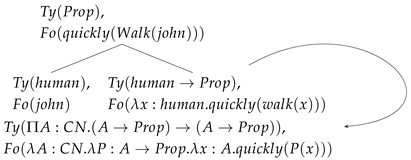

| (40) | Final tree after ELIMINATION |

| |

This is a simple treatment of VP adverbs that does not get into the details of the semantics of each adverb. However, the MLTT paradigm is expressive enough to capture various fine-grained issues in adverbial semantics. To give an example, considering veridicality, if we wanted to encode veridicality for VP (or Prop adverbs), one way is to use the following -type based account. According to this, the lexical entry for quickly will be the following:

We use an auxiliary type constructor that associates a modified predicate with a proof of veridicality:

Then, every veridical adverb is of the following definition:

For quickly, we have the following DS entry:

| (41) |

| (42) |

| (43) | Lexical Entry for veridical quickly |

| IF | |

| THEN | make(); go(); |

| put(, | |

| ) | |

| ELSE | abort |

Now, after parsing something like John walks quickly, we get the following:

- Parse gives .

- This is equal to .

- Extract the proof from the second projection: .

- Instantiate with : .

- Modus ponens: .

Same considerations apply to sentence-level adverbs. Of course, the semantics, but also syntax, of adverbs are far more complicated, but I will not delve into more fine-grained issues of adverbial semantics here. The interested reader is directed to Maienborn and Schäfer (2019); Morzycki (2016) for a general discussion on the nature and problems of modification in NL semantics and to Chatzikyriakidis and Luo (2017) for a more thorough discussion on treating the semantics of aspects of adjectival and adverbial modification using MLTT-semantics.

5. Conclusions and Future Work

In this paper, I presented a first take on how one can encode MLTT-semantics in Dynamic Syntax. I have shown a couple of use cases, including the incorporation of type many-sortedness, dependent typing for a number of issues like quantifiers, adjectives and adverbs and the use type-theoretic context to help us encode DS context in order to facilitate action rerun and similar core DS mechanisms.

One of the things we did away with was the epsilon calculus.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

This research does not have any supporting data to report.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Of course, one would want to be able to allow such cases in a number of environments where some sort of shift in meaning takes place in order to serve a specific interpretation as in the classic meaning transfer example the ham sandwich shouts. This is not a problem within the theory as the coercive subtyping mechanism can be used to introduce local coercions, i.e., local subtyping that can accommodate these interpretations. For more information, please see Luo (2011). Also see the following discussion in Section 3.1.1. |

| 2 | This was proposed for the first time in Luo (2011). |

| 3 | The + operator is used to denote a disjoint union (sum type). A disjoint union is a type whose elements are noted/tagged as coming from either type A or type B, but not both. In our case, an element of type election () is either an element from (real election) or from (fake election). The tagging ensures the two categories remain distinct. |

| 4 | From now on, I use the whole and not the subtyping coercion operation. This is not correct type-theoretically, but it is more convenient in terms of exposition. Thus, is actually . |

| 5 | The bar | denotes disjoint union, indicating that a DSAction is exactly one of the listed constructors. In type theory, as already mentioned, a disjoint union represents a type whose elements are noted/tagged as coming from either A or B, but not both. Each constructor (make, go, put, etc.) thus represents a distinct branch of the DSAction type. Pattern matching on a DSAction value allows us to determine which specific action was performed and extract its parameters accordingly. |

References

- Asher, N., & Luo, Z. (2012). Formalisation of coercions in lexical semantics. Sinn und Bedeutung, 17, 63–80. [Google Scholar]

- Bouzouita, M. (2008). The diachronic development of Spanish clitic placement. Diachronica, 25(2), 170–204. [Google Scholar]

- Cann, R., Kempson, R., & Marten, L. (2005). The dynamics of language: An introduction. Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Chatzikyriakidis, S. (2010). Clitics in four dialects of Modern Greek: A dynamic account [Doctoral dissertation, King’s College London]. [Google Scholar]

- Chatzikyriakidis, S. (2015, September 26–29). Polydefinites in Modern Greek: The missing LINK. The 11th International Conference on Greek Linguistics (ICGL 11), Rhodes, Greece. [Google Scholar]

- Chatzikyriakidis, S. (2017, April 19–20). Modification in Dynamic Syntax. The 1st Dynamic Syntax Conference, SOAS, University of London, London, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Chatzikyriakidis, S., Cooper, R., Gregoromichelaki, E., & Sutton, P. (2025). Types and the structure of meaning: Issues in compositional and lexical semantics (Elements in Semantics). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chatzikyriakidis, S., & Kempson, R. (2011). Standard Modern and Pontic Greek person restrictions: A feature-free dynamic account. Journal of Greek Linguistics, 11(2), 127–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzikyriakidis, S., & Luo, Z. (2017). Adjectival and adverbial modification: The view from modern type theories. Journal of Logic, Language and Information, 26, 45–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzikyriakidis, S., & Luo, Z. (2020). Formal semantics in modern type theories. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Chatzikyriakidis, S., & Spathas, G. (2025). Polydefinites as markers of prominence: A unified analysis of Greek polydefinites. Glossa. Under review. [Google Scholar]

- Church, A. (1940). A formulation of the simple theory of types. The Journal of Symbolic Logic, 5(2), 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, R. (2005). Records and record types in semantic theory. Journal of Logic and Computation, 15(2), 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, R. (2012). Type theory and semantics in flux. In R. Kempson, N. Asher, & T. Fernando (Eds.), Handbook of the philosophy of science, Volume 14: Philosophy of linguistics (pp. 271–323). Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Eshghi, A., Hough, J., Purver, M., Kempson, R., & Gregoromichelaki, E. (2012). Conversational interactions: Capturing dialogue dynamics. In S. Larsson, & L. Borin (Eds.), From quantification to conversation: Festschrift for Robin Cooper (pp. 325–349). College Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Eshghi, A., Howes, C., Gregoromichelaki, E., Hough, J., & Purver, M. (2015). Feedback in conversation as incremental semantic update. In Proceedings of the 11th international conference on computational semantics (IWCS 2015) (pp. 261–271). Association for Computational Linguistics. [Google Scholar]

- Gallin, D. (2011). Intensional and higher-order modal logic: With applications to Montague semantics (Vol. 19). Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Gregoromichelaki, E., Kempson, R., Purver, M., Mills, G., Cann, R., Meyer-Viol, W., & Healey, P. (2011). Incrementality and intention-recognition in utterance processing. Dialogue and Discourse, 2(1), 199–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howes, C., & Eshghi, A. (2017). Feedback relevance spaces: The organisation of increments in conversation. In Proceedings of the 12th international conference on computational semantics (IWCS 2017)—Short papers. Curran Associates, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Kempson, R., Cann, R., Eshghi, A., Gregoromichelaki, E., & Purver, M. (2015). Ellipsis. In The handbook of contemporary semantic theory (pp. 114–140). Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Kempson, R., Cann, R., Gregoromichelaki, E., & Chatzikyriakidis, S. (2016). Language as mechanisms for interaction. Theoretical Linguistics, 42(3–4), 203–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempson, R., Gregoromichelaki, E., Eshghi, A., & Hough, J. (2018). Ellipsis in Dynamic Syntax. In The Oxford handbook of ellipsis. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kempson, R., Meyer-Viol, W., & Gabbay, D. (2001). Dynamic Syntax: The flow of language understanding. Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Z. (2011). Contextual analysis of word meanings in type-theoretical semantics. In S. Pogodalla, & J.-P. Prost (Eds.), Logical aspects of computational linguistics—6th international conference, LACL 2011, proceedings (pp. 159–174). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Maienborn, C., & Schäfer, M. (2019). Adverbs and adverbials. In Semantics: Lexical structures and adjectives (pp. 477–514). Mouton de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Löf, P. (1975). An intuitionistic theory of types: Predicative part. In H. Rose, & J. C. Shepherdson (Eds.), Logic Colloquium’73 (pp. 73–118). North-Holland. [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Löf, P. (1984). Intuitionistic type theory. Bibliopolis. [Google Scholar]

- Montague, R. (1970). English as a formal language. Ed. di Comunità. [Google Scholar]

- Morzycki, M. (2016). Modification. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Purver, M., Gregoromichelaki, E., Meyer-Viol, W., & Cann, R. (2010, June 16–18). Splitting the ‘I’s and crossing the ‘You’s: Context, speech acts and grammar. The 14th Workshop on the Semantics and Pragmatics of Dialogue (SemDial 2010), Poznan, Poland. [Google Scholar]

- Purver, M., Sadrzadeh, M., Kempson, R., Wijnholds, G., & Hough, J. (2021). Incremental composition in distributional semantics. Journal of Logic, Language and Information, 30(2), 219–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranta, A. (1994). Type-theoretical grammar. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ranta, A., & Cooper, R. (2004). Dialogue systems as proof editors. Journal of Logic, Language and Information, 13, 225–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhart, T. (1997). Quantifier scope: How labor is divided between QR and choice functions. Linguistics and Philosophy, 20(4), 335–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadrzadeh, M., Purver, M., Hough, J., & Kempson, R. (2018, November 8–10). Exploring semantic incrementality with Dynamic Syntax and vector space semantics. The 22nd Workshop on the Semantics and Pragmatics of Dialogue (SemDial 2018), Aix-en-Provence, France. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton, P. R. (2022). Restrictions on copredication: A situation theoretic approach. Semantics and Linguistic Theory, 32, 335–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Coq Development Team. (2024). The Coq proof assistant reference manual, Version 8.19. INRIA. Available online: https://coq.inria.fr/refman/ (accessed on 14 October 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).