Abstract

As has repeatedly been pointed out in recent years, the categories ESL/Outer Circle and EFL/Expanding Circle should not be considered as clear-cut as traditionally assumed. Consequently, recent research has made first attempts for an integrative approach to Englishes traditionally ascribed to one of these categories. The paper at hand introduces the Extra- and Intra-territorial Forces Model (EIF Model) as a successful attempt to bridge the traditional gap between the two categories and shows how the model works in practice by implementation to the cases of Greece and Cyprus. These two countries are particularly interesting for the application of this framework since their linguistic ecologies, with Greek and English in contact, are essentially similar. From a historical perspective, however, they are fundamentally different; Cyprus is a former colony of the British Empire, whereas Greece has never experienced British colonization. Therefore, the two countries offer the perfect basis for putting the traditional categories of EFL and ESL to the test and for illustrating how more recent models of World Englishes, such as the EIF Model, might offer more flexible theoretical alternatives to earlier, often more rigid theoretical approaches.

1. Introduction

As a result of both British colonization and—much later but equally important—globalization, English has experienced unprecedented importance as the worldwide lingua franca in the 20th and 21st centuries. Linguists all over the world and from different linguistic subdisciplines have devoted their attention to different manifestations of forms of English and have described their structural properties, their sociolinguistic ecologies, and aspects of their acquisition. Native and second language Englishes—conceptually captured in the labels ENL and ESL—and their contact scenarios in the former colonies of the British Empire have become the main concern of World Englishes researchers; foreign language Englishes (EFL) have attracted the attention of linguists working in the field of second language acquisition (SLA). Both disciplines have developed various and independent theoretical frameworks for the classification of these Englishes as well as for the description and explanation of their linguistic specifics. In particular, the field of World Englishes research has developed into a flourishing subdiscipline. Several models have been devised, discussed, and modified since the 1980s, with the ENL-ESL-EFL distinction (e.g., Strang, 1970; Quirk et al., 1972, 1985), Kachru’s (1985) Three Circles of World Englishes, and Schneider’s (2003, 2007) Dynamic Model leading the way. However, despite their advantages and achievements in the field, some problems with these approaches have been identified in more recent times. Those mostly relate to one or more of the following aspects: (1) a static handling of categories and variety types, (2) a neglect of variety-internal heterogeneity (i.e., variation between speaker groups or individual speakers), (3) a lack in diachronic orientation, and (4) a strong focus on postcolonial Englishes, automatically matching historical status as a former colony with variety type (i.e., ENL or ESL). Englishes that have been developing in countries without a colonial background are often excluded in such accounts and lumped together as EFL. This is basically due to the fact that World Englishes and SLA research have so far worked independently from each other.

The paper at hand argues that only an approach addressing these problematic aspects (to be discussed in more detail in Section 2) can capture current linguistic realities of English worldwide in their entirety. I start by briefly outlining the ENL-ESL-EFL distinction, Kachru’s (1985) Three Circles, and Schneider’s (2003, 2007) Dynamic Model and discuss their applicability in reference to recent case studies. In doing so, I highlight major challenges these findings pose for current World Englishes theorizing (cf. Section 2.1). In Section 2.2, I introduce the Extra- and Intra-territorial Forces (EIF) Model (Buschfeld & Kautzsch, 2017; for an updated version, see Buschfeld, 2020b) and show how it addresses the problems of the earlier approaches discussed in Section 2.1. I subsequently illustrate (cf. Section 3) how exactly the shortcomings identified for the earlier models surface in a comparison of the historical developments and sociolinguistic situations of English in the southern, Greek-speaking part of Cyprus and mainland Greece and what an analysis of linguistic characteristics reveals about the traditionally strict separation between ESL/Outer Circle and EFL/Expanding Circle. The comparison is highly interesting and promising for the development of World Englishes theorizing since it bears on a rare sociolinguistic constellation (for another such constellation in the Asian context, see Percillier, 2016). On the one hand, the two regions under investigation show important differences in their historical background: Cyprus is a former colony of the British Empire while Greece has never experienced extended British influence of this kind. On this basis, the two cases would traditionally be assigned to different categories, i.e., ESL and EFL, respectively. On the other hand, the linguistic contact situation is similar in that Greek is spoken as a first language (L1) in both countries and English as an additional language by major parts of the population. Therefore, I inquire into the question whether transfer-induced local characteristics of L2 English in Cyprus (CyE) and Greece (GrE)1 are equally strongly entrenched and nativized in the two contexts. While the similar linguistic contact scenario might lend itself to such a conclusion, the differences in historico-political development give reason to expect quantitative differences in feature realization. To shed light on this question, Section 3 first introduces the historico-political and (socio)linguistic backgrounds of the two territories under investigation, from which I derive the motivation for the study at hand (Section 3.1), before presenting the methodology employed for the quantitative comparison of linguistic characteristics (Section 3.2). In Section 4, I present the linguistic results, before I discuss their theoretical implications and how both cases can be placed within the EIF Model in Section 5. Section 6 offers some brief conclusions regarding both the case studies and the theoretical discussion.

2. Rethinking the World Englishes Paradigm

2.1. Older Approaches vs. New Linguistic Realities

Early in the 1980s, the first formal attempts were made to overcome the monolithic view of the English language that had long prevailed (cf. McArthur, 1987, p. 9). The two most influential models from these early days are indisputably the ENL-ESL-EFL distinction (e.g., Strang, 1970; Quirk et al., 1972, 1985) and Kachru’s (1985) Three Circles model. They both build on a categorization of countries into ENL/Inner Circle, ESL/Outer Circle, and EFL/Expanding Circle, similar to Strang’s (1970) classification of the English-speaking community into A, B, and C speakers. In the Inner Circle, including countries such as the United Kingdom, the United States of America, Australia, or Canada, English is spoken as the native (ENL) and main language by the majority of the population. In Outer and Expanding Circle countries, English is spoken as a non-native second (ESL) or foreign language (EFL). In the former case, including countries such as India, Kenya, or Singapore, English was introduced as a result of (mostly British) colonization and typically has gone through the processes of nativization and often institutionalization due to political, sociocultural, and ultimately linguistic developments in society. Typically, Outer Circle countries are bi- or multilingual, and English is spoken as a second language by many or most inhabitants, having developed “an extended functional range in a variety of social, educational, administrative, and literary domains” and “acquired an important status in the language policies” (Kachru, 1985, pp. 12–13). In Expanding Circle countries such as China, Indonesia, Greece, or Saudi Arabia, English was not introduced as a result of colonial expansion (Kachru, 1985, p. 13; see also Crystal, 2003, p. 107) but due to a variety of different, not necessarily less important factors (cf. Section 2.2 for a more detailed reasoning). In such contexts, English is mainly used as a foreign language, and, as opposed to Outer Circle Englishes, it has not developed a special, internal status (Crystal, 2003, pp. 107–108) but mainly serves as a lingua franca, especially in international business. Furthermore, Outer Circle countries may develop their own norms, while Expanding Circle countries normally remain oriented and dependent on Inner Circle norms, mostly British and American English (e.g., Kachru, 1985, p. 17; see also Bruthiaux, 2003, p. 160; and McArthur, 1998, p. 59).

Both Kachru’s circles and the ENL-ESL-EFL distinction were revolutionary in that they challenged the monolithic view of the English language prevailing back then and gave non-native Englishes a voice; they have been majorly influential since then and are still widely used today. However, despite their achievements and popularity, some problems, partly of interpretation by later users, have been identified as the field of World Englishes research has moved on in reaction to both changing linguistic realities and changing foci of orientation. First of all, linguists have long treated the categories ENL-ESL-EFL/Inner-, Outer-, Expanding Circle as clear-cut, even though Kachru himself explicitly admits to the permeability between his three circles as well as the heterogeneity of speech groups (e.g., Kachru, 1985, p. 14). However, potential overlaps between the three categories, i.e., the simultaneous existence of ENL, ESL, or EFL speakers in one territory (e.g., Mesthrie & Bhatt, 2008, p. 31; Schneider, 2007, p. 13 on the co-existence of ENL and ESL in South Africa), often have not been acknowledged by later adopters of the model. Multiple membership assignment has neither been envisaged and transitions from one category to the next have mostly not been accounted for. However, many recent case studies have shown that these aspects have to be considered by a model that aims to adequately capture linguistic realities (e.g., Buschfeld, 2013 on the ESL to EFL transition of English in Cyprus; Buschfeld & Kautzsch, 2014; and Kautzsch & Schröder, 2016 on the EFL to ESL development of English in Namibia; Davydova, 2020 on the change from EFL to ESL in Germany as well as Edwards, 2016 on the Netherlands). Second, the distinctions as traditionally used have mostly not accounted for the linguistic heterogeneity found in most speech groups, i.e., the fact that varieties may vary according to sociolinguistic variables such as age, gender, educational/occupational background, etc., and hence “ignore […] certain facets of complex realities” (Schneider, 2007, pp. 12–13 on the ENL-ESL-EFL distinction). Third, they mostly lack diachronic orientation; i.e., they do not account for the development of varieties but offer a snapshot in time only.

The Dynamic Model offers a more recent, true alternative to the early approaches. In its diachronic orientation, it, in particular, addresses the second and third problems since it considers the overall development of the different Englishes under consideration and consequently allows for changes in status, prototypically from one type (e.g., EFL) to the next more advanced one (e.g., ESL). Reverse development is not explicitly envisaged in the Dynamic Model, though it is not explicitly excluded either. The model has experienced wide acceptance and application in recent years, sometimes with suggestions for slight modifications (e.g., Buschfeld, 2013, 2014; Evans, 2014; Huber, 2014; Mukherjee, 2007; Weston, 2011; cf. Schneider, 2014, for a detailed stock taking), and some criticism was voiced, too (especially Mesthrie & Bhatt, 2008, pp. 35–36). I would like to draw the readers’ attention to just one of these aspects, which is of major relevance for up-to-date World Englishes theorizing, namely, that the model is geared towards postcolonial Englishes (PCEs) only and disregards non-postcolonial Englishes (non-PCEs). I deliberately use the term “non-postcolonial” rather than “Expanding Circle” or “EFL” since I assume that this is the more neutral and thus uncontroversial term as it relies on historical facts rather than traditional ad hoc classifications in terms of status (e.g., ESL vs. EFL). What I mean here is that, at least in the age of globalization, a one-on-one mapping of historical background (i.e., postcolonial vs. non-postcolonial) on status (i.e., ESL or EFL) should be considered outdated. This assumption is supported by recent case studies, which have revealed a number of important findings and implications in this respect:

- Nativized second-language varieties of English can emerge even in countries without a British colonial background (e.g., Buschfeld & Kautzsch, 2014; Kautzsch & Schröder, 2016 on English in Namibia). This clearly indicates that colonialism is not the only decisive force behind such developments and is in no way mandatory for ESL status.

- Language political decisions and other factors can drastically alter and determine the status of English, resulting in strong entrenchment and potentially the development of second-language varieties (e.g., the cases of Namibia; Buschfeld & Kautzsch, 2014; and some countries belonging to the Association of South-East Asian Nations (ASEAN); e.g., Kirkpatrick, 2010; Schneider, 2014, pp. 22–23).

- Countries that would traditionally be assigned to the same category (e.g., EFL/Expanding Circle, ESL/Outer Circle) can be very different in their sociolinguistic setups and developments (e.g., the cases of Namibia and Germany; Kautzsch, 2014): Therefore, the EFL category—and the same applies to ESL—has to be considered very heterogeneous in itself (see also, e.g., Gilquin & Granger, 2011, p. 74).

- In a similar way, territories that would traditionally be assigned to different categories (ESL vs. EFL/Outer vs. Expanding Circle) can be more similar in their sociolinguistic setup than a strict differentiation between the categories would suggest. This is what I will focus on in the present chapter, drawing on the cases of Cyprus and Greece (cf. Section 3).

- Also to be shown in the following (Section 3), recent research has pointed to linguistic similarities between postcolonial and non-postcolonial Englishes (e.g., Biewer, 2011; Laporte, 2012; Nesselhauf, 2009). The two types often share similar linguistic features, especially when their speakers have the same substrate language as L1 (e.g., Percillier, 2016; cf. Section 3) and thus acquire and use English in similar typological contact settings. Differences in feature use are often just of quantitative nature.(For a similar list and a more detailed argument, see Buschfeld et al., 2018).

On the basis of these findings, I argue that approaches limited to postcolonial cases cannot adequately depict current linguistic realities of English worldwide. The fuzzy boundaries between EFL and ESL and most of the above observations are further reinforced by the results of the Special Eurobarometer 540 survey (European Commission, 2024, p. 21), which inquires into which languages European member state citizens speak well enough in order to have a conversation. According to the results, proficiency in English varies greatly within the group of countries that would traditionally been classified as EFL territories, with Romania coming in last with only 27% of its inhabitants feeling able to have a conversation in English and the Netherlands at the top of this list with 95%. Cyprus and Malta, the two member states with a colonial background, range in the upper third (with 80% and 91%, respectively) but below or on a par with the Scandinavian countries, i.e., Sweden 91%, Denmark 90%, and Finland 82%, even though these are non-postcolonial territories and would therefore be traditionally classified as EFL. Although it is not quite clear how exactly proficiency is measured here, these results clearly indicate current sociolinguistic realities and developmental trends of English in the EU and worldwide.

What all these observations boil down to is that the categories EFL and ESL should be viewed as extreme poles on a continuum on which Englishes are more or less EFL or ESL (or ENL) in nature and hybrid cases are conceivable (e.g., Biewer, 2011; Buschfeld, 2013). What this, in turn, shows from the perspective of World Englishes theorizing is that there is a strong need for an integrative approach to postcolonial and non-postcolonial Englishes, especially since a one-on-one mapping of historical background on variety type is not adequate and a clear categorization of types is not always possible.

To that end, it has been recently discussed whether Schneider’s (2003, 2007) Dynamic Model can account for non-PCEs as well, despite its explicit and sole orientation towards PCEs. Applying the Dynamic Model to Englishes spoken in a variety of non-postcolonial countries (from Asia, Africa, and Europe), Schneider (2014), Edwards (2016), and Buschfeld and Kautzsch (2017) identify a range of what Edwards (2016, p. 187) aptly calls “the colonial trappings of the model”. Buschfeld and Kautzsch (2017) are most comprehensive in their identification and discussion of such trappings, and they identify the following problems for an application of the Dynamic Model to non-PCEs:

- Differences in transportation of PCEs and non-PCEs; this affects the applicability of phase 1, Foundation, of the Dynamic Model;

- A lack of settler strand and external colonizing power in non-PCEs, which have exerted political, social, and linguistic influence on the (former) colony from the outside; this mainly affects the applicability of phase 2, Exonormative Stabilization, of the Dynamic Model;

- As a consequence of the missing settler strand, the type(s) of language contact and the development of identity constructions are different in non-PCE countries; linguistic accommodation between STL (settler) and IDG (indigenous population) strand does not take place; this affects all phases of the model (for further details on these aspects, see Buschfeld & Kautzsch, 2017; see also Buschfeld et al., 2018).

Schneider (2014, pp. 27–28) reacts rather pessimistically to these obstacles, concluding that “[i]n essence, the Dynamic Model is not really, or only to a rather limited extent, a suitable framework to describe this new kind of dynamism of global Englishes”. Still, the observations made earlier strongly call for an integrated approach. Edwards (2016, p. 187) therefore suggests that “the parallels [between PCEs and non-PCEs] should be salvaged, but placed in a new framework”, which is what Buschfeld and Kautzsch (2017) implement in their EIF Model. They stick to the idea of finding a solution that integrates PCEs and non-PCEs in a unified framework, salvaging parallels but also accounting for differences between the types in form of a higher-level framework.

2.2. The Extra- and Intra-Territorial Forces Model

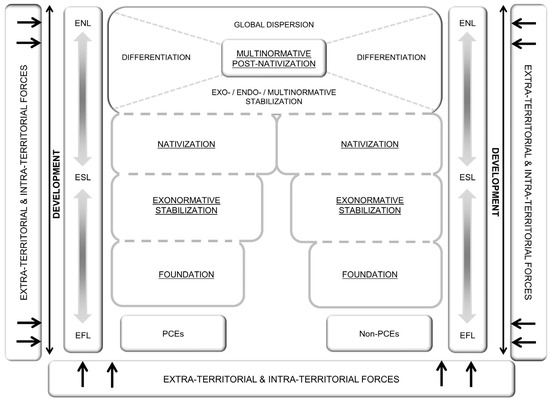

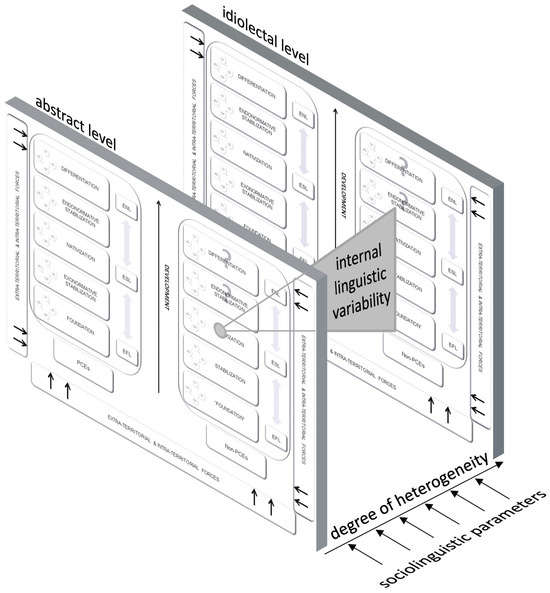

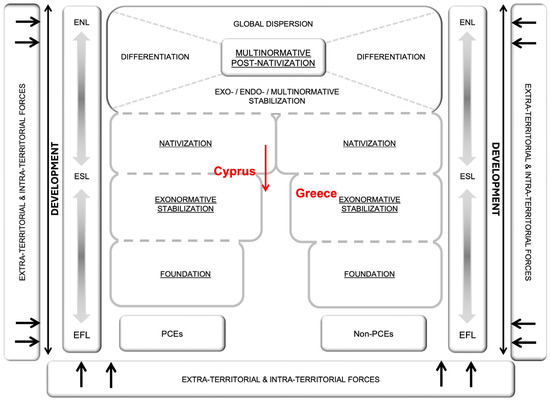

The Extra- and Intra-Territorial Forces (EIF) Model builds on two earlier conceptual frameworks, viz. Schneider’s (2014) notion of “Transnational Attraction” and the Dynamic Model. The notion of “Transnational Attraction” conceptualizes English as an attractor for both individuals and communities, who learn and use it “‘as an economic resource’ (Kachru, 2005, p. 91), a symbol of modernity and a stepping stone toward prosperity” and tries to capture “the [resulting] appropriation of (components of) English(es) for whatever communicative purposes at hand, unbounded by distinctions of norms, nations or varieties” (Schneider, 2014, p. 28). Roughly along the developmental lines of the Dynamic Model, the EIF Model assumes various forces to operate within and beyond national confines and to affect and strengthen the role and status of English in specific regions or under specific usage conditions. Such forces include, for example, language policies and language attitudes, globalization and acceptance of globalization, foreign policies, and the effect of the sociodemographic background of a region, and of course colonization and attitudes towards the colonizing power. Further forces have been added to this list in applications of the EIF Model to different non-postcolonial but also postcolonial case studies (cf. Buschfeld & Kautzsch, 2020). In the original 2017 publication, Buschfeld and Kautzsch postulate that non-PCEs, too, evolve in a more or less uniform fashion—both when compared to each other but also when compared to PCEs (cf. Schneider, 2007, p. 21, general assumption for the development of PCEs). Buschfeld (2020b) presents an update to the model, which is illustrated in Figure 1. Figure 2 constitutes a three-dimensional version of the EIF Model, taking into account the internal linguistic heterogeneity found in many varieties of English.

Figure 1.

The EIF model (from Buschfeld, 2020b, p. 411, with slight adaptation).

Figure 2.

A three-dimensional version of the EIF Model (from Buschfeld et al., 2018, p. 25).

Figure 1 and Figure 2 illustrate the major components of the model, some of which are conceptually new, and some of which draw on earlier notions and concepts that have proven suitable and thus successful in earlier approaches to theorizing World Englishes. Conceptually, the model integrates PCEs and non-PCEs and suggests that extra- and intra-territorial forces are at work in the development of the different Englishes at all times—even if in different manifestations and to sometimes different extents (e.g., the forces of globalization are developments of more recent times and were certainly not at work in the early phases of most Englishes). Its diachronic orientation is guided by the five phases and four parameters of Schneider’s Dynamic Model, but broadly links these phases to the categories EFL, ESL, and ENL, assuming that language acquisition leads to EFL speech in the initial (foundation) phase, may proceed to intensified internal functions (characteristic of ESL varieties) in the central phases and may ultimately lead to new native speakers and hence ENL varieties in the final stage (as in today’s Singapore). However, the EIF Model does not picture the three categories as clear-cut and distinct from each other; transitions from one category to the other are envisaged and possible at all times and in all directions. Furthermore, Buschfeld (2020b, pp. 410–412) revised three central aspects of the model, based on a number of theoretical considerations, which cannot be discussed in detail here (but see Buschfeld, 2020b, pp. 403–409, for a detailed discussion), and aspects raised in the individual chapters to their edited volume (Buschfeld & Kautzsch, 2020). These are summarized in the following.

First of all, she changed the set-up and labeling of the later, post-nativization stages of the model. She resolved the clear-cut and consecutive character of the phases of endonormative stabilization and differentiation and suggests a phase of “multinormative post-nativization”, which allows for exo-, endo-, or even multinormative stabilization (reacting to the suggestions made by Meer & Deuber, 2020), differentiation, and also global dispersion (cf. Figure 1). The latter aspect is meant to account for the “post-phase 5” phenomena addressed by Wee (2020) and Rüdiger (2020), in particular the commodification of, for example, Singapore and Korean Englishes. The dashed lines in this part of the model (cf. Figure 1) are meant to indicate that the three aspects are by no means obligatory. Countries may or may not go through any of these sub-phases, not necessarily through all of them and not in the exact same order. Phases may be skipped or taken at once. This, once more, depends on the exact manifestations of forces and the overall developments in the contexts under investigation.

Secondly, Buschfeld (2020b) introduced fuzzy boundaries between the phases and concepts overall. This is illustrated by the dashed lines between the phases and the EFL, ESL, and ENL categories as presented in Figure 1. In a similar way, the bi-directional arrows indicate that the development that varieties may take is by no means always a monodirectional one but that reverse development (cf. Schröder & Zähres, 2020) and thus full permeability between variety types and developmental phases is envisaged.

Last but not least, Buschfeld (2020b) implemented Wee’s (2020) idea that PCEs and non-PCEs may undergo convergence in the later stages of development. This is indicated by PCEs and non-PCEs moving closer and closer together throughout their development (cf. Figure 1). This is a particularly relevant assumption for potential developments in more recent times which are motivated by general forces of globalization and often, but gradually, level out the initial differences between the types. As Wee (2020) suggests, at some point the initial differences between PCEs and non-PCEs may be overruled by converging forces of globalization. This observation is scientifically appealing in view of current sociolinguistic developments worldwide. However, I would like to emphasize here that Buschfeld and Kautzsch (2017) never assumed that PCEs and non-PCEs develop in an exactly parallel fashion. Most importantly, the development of non-PCEs started much later than the development of most PCEs. However, the general evolutionary paths may still be comparable. Also, convergence does not necessarily set in with the nativization phase. The model still abstracts from more complex and diverse linguistic realities—this lies in the very nature of any model. It aims to point out general developmental trends and does not make any predictions about exact manifestations in particular phases.

The recent call to acknowledge variety-internal heterogeneity finds expression in the third dimension of the EIF Model illustrated in Figure 2. The figure proceeds from the most abstract level to the most detailed, i.e., from the idiolectal level with heterogeneity (visualized by the branching-off axes in Figure 2) motivated by sociolinguistic variables such as age, ethnicity, social status, gender, etc. Different subvarieties in particular contexts can be pictured as located somewhere within the triangle, depending on the particular language use of the individual or specific social groups. They may be located closer towards the node or closer towards the outside plane, depending on the level of granularity one employs.

3. English in Cyprus vs. English in Greece: Background, Motivation, and Method

3.1. Background and Motivation

As stated in the introduction to this paper (Section 1), the aim of the present study is to compare English as used in two regions, the southern, Greek-dominated part of Cyprus and mainland Greece, which show very similar language contact settings from a typological perspective but strong differences in their historical and sociopolitical developments. In the following, I briefly report the most important facts and sketch out the de facto sociolinguistic situations of both contexts (see, e.g., Vida-Mannl et al., 2025, for a more detailed account).

The Republic of Cyprus is an island country in the Eastern Mediterranean. It is factually divided into a Greek and Turkish part, mainly as a result of the Turkish occupation of the north in 1974. Officially, this division is not internationally acknowledged except by Turkey, and the overall island is officially referred to as the Republic of Cyprus, with Greek and Turkish as the two official languages of the island. English was introduced to the island under British rule (1878–1960). The Greek part of the island is dominated by Greek and its local dialect, mostly referred to as Cypriot Greek. Their relationship and use have been widely investigated and discussed in the literature, in particular by the Cyprus Acquisition Team (the CAT Lab, under the direction of Kleanthes Grohmann). To put a complex story short, the use of the two speech variants seems to depend on a number of factors such as conversational context, speakers’ attitudes and educational status, but also their individual conception as distinctly Cypriot or strongly connected to the Greek mainland. English has gradually declined in usage domains and functions since the end of British rule and the separation of the island but still plays the role of an important additional language. It has changed its overall character, though: while it shows clear traces of structural nativization and thus ESL status in older speakers, younger speakers are more strongly oriented towards the British or American standards and, therefore, seem to use it more as an EFL. The character and status of English in southern Cyprus is thus heterogeneous and of hybrid ESL-EFL nature (Buschfeld, 2013; for more details on the complex developments, political background and sociolinguistic realities in Cyprus, see, e.g., Vida-Mannl et al., 2025).

Mainland Greece, not surprisingly, is an equally Greek-dominated territory, with Greek being the only official language of the country. English is also used as an important additional language (as nearly everywhere in today’s globalized world) but was not introduced through British colonization. Therefore, it is their historical background that clearly sets the two countries apart from each other. On the basis of traditional World Englishes approaches, this would suggest that CyE must constitute some kind of ESL context, whereas GrE belongs to the category of EFL. And indeed, sociolinguistic differences exist between the two scenarios, resulting from the difference in extra-territorial force “presence vs. absence of British colonization”. Still, the linguistic contact scenario, viz. L1 Greek—L2 English, is similar2, as are other factors such as the influence and impact of tourism or the speakers’ exposure to different English varieties via digital mass media (see also Davydova, 2024), which as extra-territorial forces strongly influences the status, use, and development of the English language in many countries worldwide. As is shown in the following, a classification of the two contexts is not as straightforward as traditional approaches might suggest: language proficiency is more wide-spread in Cyprus (80%) than in Greece (52%) (cf. European Commission, 2024, p. 21), yet the differences in these numbers are not as strong as a strict categorization into EFL and ESL might suggest. While local, at least partly nativized English characteristics have been reported for southern Cyprus and in particular older speakers who acquired English in a more naturalistic fashion and still under British rule (Buschfeld, 2013), in Greece—as in many non-postcolonial countries—it is mainly the young generation that demonstrates good command of English but clearly is oriented towards the British or American standards. The question that consequently arises is whether GrE also employs local linguistic characteristics that have gained a certain degree of stability and systematicity, i.e., widespread usage, or whether these forms are more accurately described as learner errors. From a preliminary but rather superficial analysis of the two speech corpora at hand (to be introduced in Section 3.2), I can report strong similarities between L2 CyE and GrE. Both are, for example, characterized by zero subjects (Examples 1 & 2), intransitive use of verbs (i.e., zero objects), particularly frequent with the verb like (Examples 3 & 4), local strategies for expressing hypothetical context (e.g., will-future or simple present instead of conditional simple; Examples 5–8), use of intensifier too + much instead of very + much (Examples 9 & 10), as well as the time reference pattern before X days/weeks/months/years (Examples 11 & 12):

| (1) | IE: […] I mean just # do you want to have a family, do you wanna marry? |

| I: Some time yes. [Ø subj.] don’t have a problem, but not right now. (CyE) | |

| (2) | I: Uhm, [Ø subj.] actually believe that uh […] it’s a problem that still remains unsolved and I don’t think that will ever be solved. (GrE) |

| (3) | IE: Do you like to travel? |

| I: Yes, I like [Ø obj.]. (CyE) | |

| (4) | IE: So you like uh [///] you are an outgoing person, an extrovert, you like meeting |

| people, mh? | |

| I: Oh, yeah, very much. I like [Ø obj.], you know. (GrE) |

Answering the question “What would you do if you won the lottery?” (Examples 5–8):

| (5) | I: Uh uhm uh the first thing I will make with the first million, I will take it to the h& uh [//] to our house […]. (CyE) |

| (6) | […] I will have the feeling that I’m save for the rest of my life, for the uh financial |

| department. And uhm I’ll give some money to friends and relatives to make them feel better. And uhm I think I’ll be travelling a lot. (GrE) | |

| (7) | I: Uh me, uh I take for myself one thousand-hundred. (CyE) |

| (8) | I: I give some moneys to poor people. (GrE) |

| (9) | I: […] she love me too much, more than I. (CyE) |

| (10) | I: I […] told you ea& [/] earlier that uh I want to travel to& # [/] too much. (GrE) |

| (11) | I: Yes. The mo& [/] the most important uhm uh experience in my life […] was uhm |

| my first child’s birth. […] Yes. Before eighteen years. (CyE) | |

| (12) | I: Now there’s not. No it’s uh not so much than before twenty, thirty years, or that |

| years. (GrE) | |

| (all examples for CyE taken from Buschfeld, 2013) |

These and similar features are primarily the result of L1 transfer; i.e., speakers of L1 Cypriot (CG) or Standard Modern Greek (SMG) have these structures in their L1 and transfer them to their L2, in this case English, thus creating local English forms that deviate from the traditional target. I briefly illustrate this process for one of the features selected for quantification for the present study, i.e., expressing hypothetical context. As Examples 5 and 6 illustrate, will-future is a viable alternative for expressing hypothetical context in CyE and GrE. This is due to the following structure in both SMG and CG, illustrated in Examples 13 and 14:

| (13) | Tom would go to school every day if he wasn’t lazy. |

| O Tom enna epiene sholio kathe mera, an den itan tembelis. (GCD) | |

| The Tom FUT go.3SG school every day, if not is.3SG lazy | |

| (14) | Tom will go to school. (Some time in the future) |

| O Tom enna pai sholio. (GCD) | |

| The Tom FUT go.3SG school | |

| (examples taken from Buschfeld, 2013, p. 85; for further details and transfer examples, cf. Buschfeld, 2013, pp. 77–90). | |

As Examples 13 and 14 illustrate, enna, a future particle, is used to indicate both future reference and hypothetical context, which leads to the conflation of the two in CyE and GrE, too. Still, the question arises whether this and similar transfer-induced characteristics are equally strongly entrenched and nativized in both contexts. Nativization of linguistic features does not emerge in a vacuum but under specific historical, political, and sociolinguistic and language acquisitional circumstances—as envisaged by the EIF Model introduced in Section 2.2. Whether a feature has undergone nativization further depends on its frequency of use, not only in an individual speaker but in general society or at least parts of it. Buschfeld (2013, p. 65) has discussed several factors pertaining to these issues and what they suggest for the status of a specific type of English (cf. Section 4 for further discussion).

Regarding the comparison at hand, the differences in historico-political development of the two contexts give reason to expect quantitative differences in feature realization. To shed more conclusive light on this question, I conducted a quantitative analysis of two of the high-frequency features identified for spoken, informal CyE, viz. expressing hypothetical context and use of intensifier too + much instead of very + much, as examples. Of course, the results from an analysis of two linguistic characteristics only should be treated as provisional findings from a pilot study into a highly complex and promising larger project. Further research is needed and underway to shed more conclusive light on the question whether and to what extent linguistic features of CyE and GrE have undergone nativization (cf. Section 6 for some more details).

3.2. Methodology

The data come from two spoken corpora of informal conversation, consisting of 20 to 60 min Labovian-style interviews (e.g., Labov, 1968, 1972, 2006). The Cyprus corpus, CEDAR (Cyprus English Data Analysis and Research), contains data from 90 participants from the southern, Greek-speaking part of Cyprus, from different age groups (aged 14 to 78) and from different educational and social backgrounds. The mainland Greece corpus, GEDAR (Greek English Data Analysis and Research), contains data from 18 participants from mainland Greece, again from different age groups (19 to 75) and educational and social backgrounds. The data were collected between 2007 and 2010 and manually transcribed and coded by two independent transcribers/coders for the absence and presence of the respective forms (i.e., local usage vs. “standard” British/American English [BrE/AmE] usage). Frequencies were counted in TAMS Analyzer (Weinstein, 2002–2023), a freeware research tool for Macintosh OS X designed to implement qualitative and quantitative analyses. It was chosen for analysis because it allows for the creation, application, and counting of individual codes that meet the specific demands and aims of the project (for further details on the methodology pursued, see Buschfeld, 2013). Finally, I calculated and compared relative frequencies of local vs. BrE/AmE realizations of the characteristics under investigation in the two varieties. Results are presented by means of tables and bar charts illustrating the absolute (token numbers) and relative (percentages) frequencies. For quantifying the expression of hypothetical context, the different options for local realizations, most prominently the use of will-future and simple present tense (cf. Examples 5–8), are subsumed under “CyE and GrE realizations”. I do not measure differences between local options in the envelope of variation as these are not important for the investigation at hand.

Significances of the results and influences of independent sociolinguistic variables, i.e., country (Cyprus vs. Greece), age (as continuous variable), gender (male vs. female), occupation (academic vs. non-academic), and time spent in an English-speaking country (as continuous variable), were modeled by means of conditional inference trees (ctrees; Hothorn et al., 2006) in R Studio (Posit team, 2025; Version 2025.05.1+513). Ctrees are an often-used inferential statistical tool in linguistic studies (Gries, 2020; Hothorn et al., 2006; Tagliamonte & Baayen, 2012) since they can handle small data sets and are straightforward to interpret. In general, ctrees employ statistical tests for inference and automatically identify and include those decisions that significantly improve the correct prediction of, in the present case, the variants expressing hypothetical context or too much vs. very much. To counteract a problem often encountered in variationist linguistics, i.e., that the two (or more) classes investigated (here standard vs. non-standard realizations) are of different sizes, I made use of a new function, RePrInDT, which is available as part of the software package PrInDT (Weihs & Buschfeld, 2023), to resample the classes in a way that balances out imbalanced token numbers and thus improves the balanced accuracy of the models, i.e., the accuracy taking into consideration the prediction of both the large and the small classes (for further details, cf. Buschfeld & Weihs, forthcoming). The labels “standard” vs. “non-standard” are not meant to imply linguistic superiority of one form over the other but simply refer to and subsume the traditional linguistic realizations vs. the local variants of the variables under investigation. For the realization of conditional simple structures, the non-standard realizations outnumber the standard ones (326 vs. 216 tokens); for the choice of too much in contexts that would traditionally require very much, the standard form constitutes the large class (103 vs. 47 tokens). I ran RePrInDT to model list of percentages to find the best combinations with following percentages for both classes and both features, 0.1, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 0.99. This step revealed the following percentages: plarge = 0.75, psmall = 0.99 for the realization of conditional simply; plarge = 0.6, psmall = 0.99 for too much vs. very much.

4. Results

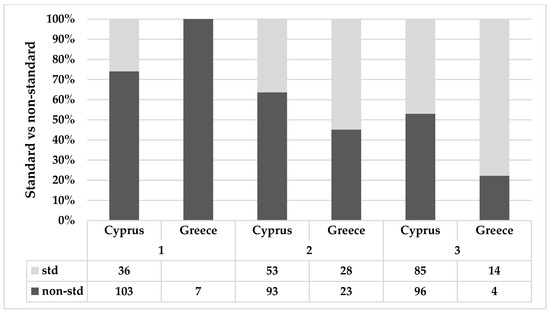

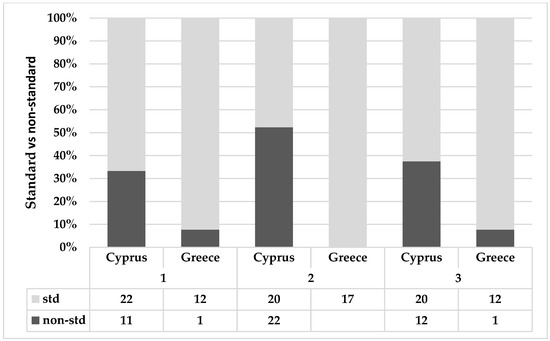

Turning towards the results of the present study, Figure 3 and Figure 4 illustrate the quantitative differences in the realization of the two characteristics under observation between CyE and GrE, also taking into consideration potential differences between three age groups to account for potential changes in status of the varieties, as already observed for Cyprus (Buschfeld, 2013). The three age groups are the same for both contexts and follow the division into age groups in Buschfeld (2013). Group 1 contains participants 61 years and older, group 2 participants between 31 and 60 years of age, and group 3 participants 30 and younger (for further details, cf. Buschfeld, 2013, p. 99). For Cyprus, participants are more or less evenly distributed across age groups and genders. For Greece, the distribution is less even (group 3: two female, one male; group 2: six female, three male; group 3: three female, three male) and requires some modification in follow-up studies.

Figure 3.

Quantitative differences in the use of conditional simple structures (BrE/AmE realization) and non-conditional simple structures (CyE and GrE realizations) by country and age group.

Figure 4.

Quantitative differences in the use of too much (CyE and GrE realization) instead of very much (BrE/AmE realization) by country and age group.

As Figure 3 and Figure 4 illustrate, for both characteristics the use of the local variant is clearly higher in Cyprus than in Greece. The outlier in group 1 in the data from Greece needs to be treated with some caution as it relies on seven tokens from three participants only. In Cyprus, the use of non-conditional simple structures (including both will-future and simple present as well as some other non-standard but rather rarely used or idiosyncratic variants) ranges above 50% for all age groups, indicating strong use and entrenchment of the local forms. Still, we can also observe a decline of features for the younger generations since group 1 prefers the local variant in over 70% of all cases while it goes down to slightly over 50% in group 3. For Greece, the data also reveals a clear downward trend in feature use. When it comes to the use of too much instead of very much, the local realization is less frequent overall in both varieties but, again, clearly higher for CyE than for GrE. For Cyprus, it is the middle-aged generation that prefers too much over very much in more than 50% of all cases, followed by the youngest group with close to 40% of use of the local variant. Interestingly, the old generation ranges lowest in their use of the local variant but still clearly over 30%. In the Greek data, the middle-aged group makes no use of the local variant at all, while the oldest and youngest groups both range around 8% of local feature use. This finding, too, might be a coincidence resulting from rather low token numbers, but it shows that no clear downward trend can be observed either.

What these numbers imply in terms of feature nativization is certainly debatable. Schneider observes in this respect that

[i]ndigenous usage starts as preferences, variant forms used by some while at the same time a majority of others will stick to the old patterns; then it will develop into a habit, used most of the time and by a rapidly increasing number of speakers, until in the end it has turned into a rule, constitutive of the new variety and adopted by the vast majority of language users, with a few exceptions still tolerated and likely to end up as archaisms or irregularities.(Schneider, 2007, p. 44)

Building on his observations, Buschfeld (2013, p. 65) has suggested some rough “numerical benchmarks for assessing whether a characteristic is undergoing or has undergone feature nativization”:

- 30% usage of the local variant(s) as a rough starting point of indigenous usage as this roughly seems to correspond to part one of Schneider’s assumption, i.e., that “[i]ndigenous usage starts as preferences, variant forms used by some while at the same time a majority of others will stick to the old patterns” (Schneider, 2007, p. 44).

- 50% usage of the local variant(s) as numerical benchmark for step two, i.e., development “into a habit, used most of the time and by a rapidly increasing number of speakers” (Schneider, 2007, p. 44); I here assume that “this can be considered the turning point when a local characteristic starts to outnumber an old pattern and gradually turns into a rule” (Buschfeld, 2013, p. 66).

In terms of the above numbers, this means that the use of non-conditional simple structures to express hypothetical context appears to be a nativized feature of CyE, but it also constitutes a fairly entrenched local variant in mainland Greece. The same is true for the CyE use of too much over very much; only the GrE use of this feature ranges clearly below the nativization threshold. It still needs to be kept in mind, of course, that the suggested benchmarks are not meant to be absolute, unalterable numbers but rather rough points of orientation for feature analyses and interpretation (cf. Buschfeld, 2013, pp. 63–66, for a more detailed discussion of feature nativization). Concerning the present research question and expectations, the results clearly indicate that, despite the linguistic similarities between the two contexts, extralinguistic factors such as the historical and political background of the contexts overrule the typological factors. L1 transfer can be observed for both contexts, which is why the local characteristics are found in both Englishes. The quantitative differences detected, however, are the results of the respective historico-political and, as a result, sociolinguistic background of the respective context.

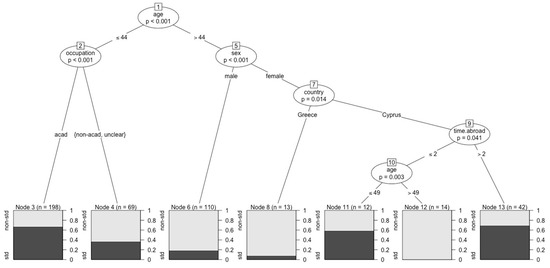

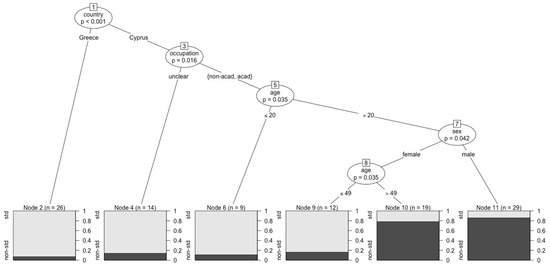

When finally turning to the results from the inferential statistical analysis, Figure 5 and Figure 6 reveal that all sociolinguistic variables included in the analysis have a statistically significant influence on the data. In the following, I focus on country and age since these are the most important ones for the analysis at hand.

Figure 5.

PrInTD-generated ctree illustrating the influence of significant sociolinguistic variables on the realization of conditional simple structures.

Figure 6.

PrInTD-generated ctree illustrating the influence of significant sociolinguistic variables on the use of too much instead of very much.

For the realization of conditional simple (Figure 5), age appears to be the most important predictor (Node 1) and splits the participants at age 44. The following branches show that occupation splits the participants in the younger generation, with those working in academic positions making a statistically more frequent use of standard realizations (dark grey, Node 3) than those in non-academic positions (or for whom occupation was unclear; Node 4). For those older than 44 years, I focus on the split by country. For Greece, the use of non-standard, local realizations is predicted for almost all cases. For Cyprus, the realization of conditional simple first depends on time spent in an English-speaking country. Those participants who spent more than two years in an English-speaking country clearly prefer the standard variant (Node 13), while those with two years or less years in an English-speaking country being split by age again. Those participants older than 49 years almost always make use of the local variants while those 49 and younger show a slight preference for the standard variant. It can, therefore, be concluded that both age and country have a significant effect on the results, with, in particular, older Cypriots, but also older Greeks, showing a very strong tendency towards local forms.

For the use of too much vs. very much, country turned out to be the most important predictor (Figure 6, Node 1). For Greece, the use of the local variant (light grey) too much is very rare (Node 2). For the follow-up splits for Cyprus, I focus on the age splits. Node 5 splits the participants into those 20 years and younger, who mostly make use of the standard variant (Node 9). For participants older than 20 years, the model has revealed a split by gender with male participants making much use of the non-standard forms (in line with sociolinguistic theory). For female participants, age plays a decisive role again. Female participants 49 and younger clearly prefer the standard variant (Node 9), while older female speakers make quite strong use of the local form (Node 10).

The trees come with a balanced accuracy of 72.6% and 83.8%, respectively, and can thus be considered quite robust. I will discuss what these findings imply for variety status and World Englishes modeling in the following section (Section 5).

5. Discussion: General Implications and the Extra- and Intra-Territorial Forces Model

As the comparisons of some sociolinguistic, historical, and demographic aspects as well as the quantitative comparison of linguistic characteristics of CyE and GrE have revealed, similarities as well as clear differences exist between the two L2 scenarios. The latter are certainly motivated by the extra-linguistic factor “colonization”. However, further extra- and intra-territorial forces should be taken into consideration when characterizing different types of English; this has been argued in Section 2.1 and Section 2.2 and is clearly reinforced by the comparison of Cyprus and Greece.

The results presented in Section 4 show that, for Greece, a clear difference in the use of local variants exists between the two features investigated. Their frequency is very high for the realization of local conditional simple structures, in particular for older participants, but rather infrequent for the local too much structure. For Cyprus, the use of local variants for both features is very high, again in particular for the older generation.

When accounting for the linguistic similarities between the sociolinguistic settings, the extra-territorial force “tourism” and the intra-territorial force “language contact situation” certainly play a strong role. The finding that both contexts show a stronger use of local characteristics for the older cohorts of participants can likely be explained by a generally heightened exposure of younger people to traditional native Englishes, in particular AmE, via global media and higher and more flexible social mobilities, i.e., younger generations having spent far more time travelling. Schooling effects, i.e., increased language teaching by more proficient, better-trained, standard-oriented teachers, likely play a role here, too.

The criterion “colonization” alone is therefore not sufficiently diagnostic to account for the status of a particular type of English. Still, the higher usage rates of local variants for Cyprus and the fact that Greek speakers make comparatively strong use of one feature but not the other show that colonization of course has an influence on the development of Englishes. In more general terms, this finding suggests that features can go different ways when it comes to nativization, even under the exact same circumstances, as my results suggest for the case of Greece. This can be explained by findings from second language acquisition research, which have shown that cross-linguistic influence, which is at the heart of feature nativization, appears to be domain-specific; i.e., it occurs for some areas of grammar but not for others (e.g., Paradis & Genesee, 1996).

In general, the comparison of the two sociolinguistic settings has revealed that, even though differences between the two scenarios exist, these are by no means pronounced enough to assign the two cases to completely different categories, viz. as clear cases of either ESL or EFL. Instead, it once more shows that these categories should be considered as poles on a continuum on which different Englishes can be more or less ESL or EFL in nature. The overall findings from this study therefore clearly reinforce the need for an integrative approach towards ESL and EFL (and probably also ENL), voiced in recent years (cf. Section 2.1 and Section 2.2). Taking into consideration the earlier work by Buschfeld (2013) and the results of the present study, Cyprus and Greece might roughly occupy the following positions within the EIF Model (cf. Section 2.2). In what direction Greece will develop cannot conclusively be determined on the basis of two features and 18 participants only and requires some further research. It will certainly depend on future developments of extra- and intra-territorial forces such as language attitudes, educational polices, the availability of digital mass media, and tourism.

As Figure 7 illustrates, CyE can be located somewhere between ESL and EFL, still closer to the ESL pole but undergoing reverse development towards EFL (indicated by the downwards pointing arrow; cf. Buschfeld, 2013). GrE likewise is to be located somewhere between the EFL and ESL poles but is clearly more EFL in nature than CyE. However, the strong local use of non-conditional simple structures might point to further development towards ESL, but more research is needed to shed conclusive light on this question. A more systematic study of further participants and linguistic characteristics, including other levels of linguistic description (especially also the phonological domain), is necessary since linguistic feature nativization cannot be measured on the basis of only few individual features and requires systematicity in usage and societal entrenchment.

Figure 7.

Cyprus and Greece in the EIF Model.

What is more, Greece—like many other countries around the globe—will certainly be subject to further influences of globalization (e.g., through the Internet and tourism) and the further entrenchment of English worldwide, which, I assume, are not going to recede in the foreseeable future but rather experience further increase. Nevertheless, my classification here is a rather perfunctory one and remains on the abstract level of the model. A more detailed investigation of extra- and intra-territorial forces as well as of variety-internal variation is required to more precisely locate GrE in terms of the EIF model.

What these findings suggest on a higher-level theoretical basis is that the World Englishes and Language Acquisition research paradigms should work more closely together. According to traditional lines of thinking, GrE would be treated as a learner English/EFL and thus would fall within the realm of SLA research. CyE, on the other hand, would be considered a PCE and therefore as ESL and belonging to the field of World Englishes research. However, as a number of studies before (cf. Section 2.1), the comparison at hand has revealed that such a strict conceptual separation and consequently a clear distinction between the two research fields does not reflect current linguistic developments. It is therefore high time the two fields started working more closely together to share their expertise on the different types of English, viz. their conceptions and methodologies to jointly and comprehensively investigate and understand the characteristics, acquisition, and developments of Englishes around the world, no matter of what type.

6. Conclusions

With globalization and changing sociolinguistic realities worldwide, linguists see themselves confronted with new challenges. One of these is the fact that the rather artificially created borders between allegedly well-defined types of English are becoming more and more indistinct, as is the case for the ESL-EFL distinction. This has been observed by a number of case studies in recent times and asks for a more flexible theoretical approach towards World Englishes theorizing (cf. Section 2.1). With the EIF Model, such an approach was introduced in Section 2.2. The case study presented in Section 3 and Section 4 corroborates these earlier assumptions. On the basis of a quantitative comparison of two linguistic characteristics that both exist in CyE and GrE, I have shown how the similarity in a linguistic contact scenario (both L1 Greek) leads to qualitatively similar L1 transfer structures in L2 English but that the local variants come with differences in their frequency of use. Still, these are not as strongly pronounced and consistent in pattern as would be expected for two completely distinct types of English. I, therefore, conclude that the differences in the historico-political developments and certainly other forces operating on the development and entrenchment of English do have an impact on feature use in the two contexts but that these differences are not strong enough to warrant unambiguous and clear-cut categorization into one of the categories ESL/Outer Circle or EFL/Expanding Circle. I have thus argued that both have to be located between the two poles, with CyE in reverse development from ESL to EFL and GrE more EFL in nature, though one of the features investigated would also meet the frequency criterion for (early) structural nativization. I have discussed a number of theoretical implications arising from such findings and have shown how only an integrative approach to postcolonial and non-postcolonial Englishes, here the EIF Model, can adequately account for such new linguistic realities.

Still, further research is needed to shed more detailed light on the question of how linguistic criteria (here: similar linguistic background) interact with colonization and, ultimately, further extra- and intra-territorial forces in the formation of new Englishes. Besides the potential to further investigate the sociopolitical and sociolinguistic background of Greece to compare it with the case of Cyprus, the two contexts have even more to offer for the discussion at hand. As briefly mentioned in Section 3.1, even though the linguistic differences between CG and SMG were not important for the comparison at hand, they do exist and can be exploited for a similar yet unprecedented study. Comparing how phonological or grammatical characteristics, in which CG and SMG differ, transfer into L2 CyE or GrE and how these frequencies compare to the frequencies of characteristics that are realized the exact same way for both varieties may yield additional insights into the complex interaction of typological similarities in contact scenario, colonial background, and further extra- and intra-territorial forces at work in the respective scenarios (cf. Rak & Buschfeld, in prep.). Furthermore, the inclusion of further linguistic features and higher numbers of GrE speakers will consolidate (or modify) the findings at hand and is of crucial importance for generating conclusive and reliable results.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

This study reports on data of which parts where briefly indicated in an earlier publication (CUP) which has a completely different aim. The data set and results as described and used in the present article is different in purpose and much more detailed. In the earlier publication, it was only used for quick illustration and not described in much detail (cf. Buschfeld (2020a). Language Acquisition and World Englishes. In D. Schreier, M. Hundt, & E. W. Schneider (eds.), The Cambridge 674 Handbook of World Englishes (pp. 559–584). Cambridge University Press (https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108349406.024)).

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the anonymous reviewers, Caroline Rak, and, in particular, Julia Davydova for their invaluable comments, suggestions, and support. All remaining shortcomings are, of course, my own.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | I use the abbreviations CyE and GrE here for reasons of economy and uniformity; I do not intend to imply anything about the status of these Englishes but use these labels as a neutral means of indication that they are spoken in the country under investigation as important additional languages. |

| 2 | Please note that the dialectal differences between the two speech communities (viz. Standard Modern Greek and Cypriot Greek) can safely be neglected for the study at hand (but see my more detailed comment in the conclusion). |

References

- Biewer, C. (2011). Modal auxiliaries in second language varieties of English: A learner’s perspective. In J. Mukherjee, & M. Hundt (Eds.), Exploring second-language varieties of English and learner Englishes: Bridging a paradigm gap (pp. 7–33). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruthiaux, P. (2003). Squaring the circles: Issues in modeling English worldwide. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 13(2), 159–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buschfeld, S. (2013). English in Cyprus or Cyprus English? An empirical investigation of variety status. John Benjamins. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buschfeld, S. (2014). English in Cyprus and Namibia: A critical approach to taxonomies and models of world Englishes and second language acquisition research. In S. Buschfeld, T. Hoffmann, M. Huber, & A. Kautzsch (Eds.), The evolution of Englishes: The dynamic model and beyond (pp. 181–202). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buschfeld, S. (2020a). Language acquisition and world Englishes. In D. Schreier, M. Hundt, & E. W. Schneider (Eds.), The Cambridge 674 handbook of world Englishes (pp. 559–584). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buschfeld, S. (2020b). Synopsis: Fine-tuning the EIF Model. In S. Buschfeld, & A. Kautzsch (Eds.), Modelling world Englishes: A joint approach to postcolonial and non-postcolonial varieties (pp. 397–415). Edinburgh University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buschfeld, S., & Kautzsch, A. (2014). English in Namibia: A first approach. English World-Wide, 35(2), 121–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buschfeld, S., & Kautzsch, A. (2017). Towards an integrated approach to postcolonial and non-postcolonial Englishes. World Englishes, 36(1), 104–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buschfeld, S., & Kautzsch, A. (Eds.). (2020). Modelling current linguistic realities of English world-wide: The extra- and intra-territorial forces model put to the test. Edinburgh University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Buschfeld, S., Kautzsch, A., & Schneider, E. W. (2018). From colonial dynamism to current transnationalism: A unified view on postcolonial and non-postcolonial Englishes. In S. C. Deshors (Ed.), Modelling world Englishes in the 21st century: Assessing the interplay of emancipation and globalization of ESL varieties (pp. 15–44). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buschfeld, S., & Weihs, C. (forthcoming). Optimizing decision trees for the analysis of world Englishes and sociolinguistic data. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Crystal, D. (2003). The Cambridge encyclopedia of the English language (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davydova, J. (2020). English in Germany: Evidence from domains of use and attitudes. Russian Journal of Linguistics, 24(3), 687–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davydova, J. (2024). EFL adolescents’ use of English in the era of new digital media: An empirical investigation. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 35(2), 617–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, A. (2016). English in the Netherlands: Functions, forms and attitudes. John Benjamins. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. (2024). Special Eurobarometer 540: Europeans and their languages. Available online: https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/2979 (accessed on 27 May 2025).

- Evans, S. (2014). The evolutionary dynamics of postcolonial Englishes: A Hong Kong case study. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 18(5), 571–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilquin, G., & Granger, S. (2011). From EFL to ESL: Evidence from the international corpus of learner English. In J. Mukherjee, & M. Hundt (Eds.), Exploring second-language varieties of English and learner Englishes: Bridging a paradigm gap (pp. 55–78). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gries, S. T. (2020). On classification trees and random forests in corpus linguistics: Some words of caution and suggestions for improvement. Corpus Linguistics and Linguistic Theory, 16(3), 617–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hothorn, T., Hornik, K., & Zeileis, A. (2006). Unbiased recursive partitioning: A conditional inference framework. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics, 15(3), 651–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, M. (2014). Stylistic and sociolinguistic variation in Schneider’s Nativization Phase: T-affrication and relativization in Ghanaian English. In S. Buschfeld, T. Hoffmann, M. Huber, & A. Kautzsch (Eds.), The evolution of Englishes: The dynamic model and beyond (pp. 86–106). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kachru, B. B. (1985). Standards, codification and sociolinguistic realism: The English language in the outer circle. In R. Quirk, & H. G. Widdowson (Eds.), English in the world. Teaching and learning the language and literatures (pp. 11–30). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kachru, B. B. (2005). Asian Englishes beyond the canon. Hong Kong University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kautzsch, A. (2014). English in Germany: Spreading bilingualism, retreating exonormative orientation and incipient nativization? In S. Buschfeld, T. Hoffmann, M. Huber, & A. Kautzsch (Eds.), The evolution of Englishes: The dynamic model and beyond (pp. 203–227). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kautzsch, A., & Schröder, A. (2016). English in multilingual and multiethnic Namibia: Some evidence on language attitudes and on the pronunciation of vowels. In M. Tönnies, C. Ehland, & I. Mindt (Eds.), Anglistentag paderborn 2015: Proceedings (pp. 277–288). WVT. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick, A. (2010). English as a lingua franca in ASEAN: A multilingual model. Hong Kong University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Labov, W. (1968). The reflection of social processes in linguistic structures. In J. A. Fishman (Ed.), Readings in the sociology of language (pp. 240–251). De Gruyter Mouton. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labov, W. (1972). Some principles of linguistic methodology. Language in Society, 1(1), 97–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labov, W. (2006). The social stratification of English in New York City (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laporte, S. (2012). Mind the gap!: Bridge between world Englishes and learner Englishes in the making. English Text Construction, 5(2), 264–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McArthur, T. (1987). The English languages? English Today, 3(3), 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McArthur, T. (1998). The English languages. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meer, P., & Deuber, D. (2020). Standard English in Trinidad: Multinormativity, translocality, and implications for the dynamic model and the EIF model. In S. Buschfeld, & A. Kautzsch (Eds.), Modelling world Englishes: A joint approach to postcolonial and non-postcolonial varieties (pp. 274–297). Edinburgh University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesthrie, R., & Bhatt, R. M. (2008). World Englishes: The study of new linguistic varieties. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, J. (2007). Steady states in the evolution of new Englishes: Present-day Indian English as an equilibrium. Journal of English Linguistics, 35(2), 157–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesselhauf, N. (2009). Co-selection phenomena across New Englishes: Parallels (and differences) to foreign learner varieties. English World-Wide, 30(1), 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradis, J., & Genesee, F. (1996). Syntactic acquisition in bilingual children: Autonomous or interdependent? Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 18(1), 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Percillier, M. (2016). World Englishes and second language acquisition. Insights from Southeast Asian Englishes. John Benjamins. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posit team. (2025). RStudio: Integrated development environment for R (Version 2025.05.1+513) [Computer software]. Posit Software, PBC. Available online: http://www.posit.co/ (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Quirk, R., Greenbaum, S., Leech, G., & Svartvik, J. (1972). A grammar of contemporary English. Longman. [Google Scholar]

- Quirk, R., Greenbaum, S., Leech, G., & Svartvik, J. (1985). A comprehensive grammar of the English language. Longman. [Google Scholar]

- Rak, C., & Buschfeld, S. (in prep.). Comparing Cypriot Greek English and standard Greek English: Implications for world Englishes and second language acquisition research.

- Rüdiger, S. (2020). English in South Korea: Applying the EIF model. In S. Buschfeld, & A. Kautzsch (Eds.), Modelling world Englishes: A joint approach to postcolonial and non-postcolonial varieties (pp. 154–178). Edinburgh University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, E. W. (2003). The dynamics of new Englishes: From identity construction to dialect birth. Language, 79(2), 233–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, E. W. (2007). Postcolonial English: Varieties around the world. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, E. W. (2014). New reflections on the evolutionary dynamics of World Englishes. World Englishes, 33(1), 9–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröder, A., & Zähres, F. (2020). English in Namibia: Multilingualism and ethnic variation in the extra- and intraterritorial forces model. In S. Buschfeld, & A. Kautzsch (Eds.), Modelling world Englishes: A joint approach to postcolonial and non-postcolonial varieties (pp. 38–62). Edinburgh University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strang, B. M. H. (1970). A history of English. Methuen. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagliamonte, S. A., & Baayen, H. R. (2012). Models, forests, and trees of York English: Was/were variation as a case study for statistical practice. Language Variation and Change, 24(2), 135–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vida-Mannl, M., Buschfeld, S., & Grohmann, K. K. (2025). The linguistic ecology of Cyprus. In P. Siemund, G. Stein, & M. Vida-Mannl (Eds.), Word Englishes in their local multilingual ecologies (pp. 166–189). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wee, L. (2020). English in Singapore: Two issues for the EIF Model. In S. Buschfeld, & A. Kautzsch (Eds.), Modelling world Englishes: A joint approach to postcolonial and non-postcolonial varieties (pp. 112–132). Edinburgh University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weihs, C., & Buschfeld, S. (2023). PrInDT: Prediction and interpretation in decision trees for classification and regression, R package version 1.0.1. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=PrInDT (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Weinstein, M. (2002–2023). TAMS analyzer. Available online: http://tamsys.sourceforge.net/ (accessed on 30 October 2012).

- Weston, D. (2011). Gibraltar’s position in the dynamic model of postcolonial English. English World-Wide, 32(3), 338–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).