Abstract

Forced vibrations of turbine blades induced by airflow excitation can severely threaten the service life of radial flow turbines in aircraft environmental control systems (ECSs). However, existing studies on airflow excitation in ECS radial flow turbines using novel tubular nozzles are limited. To address this research gap, the ultra-high-frequency airflow excitation characteristics and resonance behavior in an ECS radial flow turbines were studied using numerical simulations and experiments. The effects of radial clearance between the nozzle and the impeller, as well as the nozzle layout, on airflow excitation were investigated. The results indicate that, with the current tubular nozzle design, no shock waves were generated at the nozzle outlet. The rotor–stator interaction was the primary source of excitation in ECS radial flow turbines employing tubular nozzles, inducing significant first-order airflow excitation and leading to turbine fatigue failure. Increasing the radial clearance between the impeller and the nozzle can effectively reduce airflow excitation; however, this effect was nonlinear. With increasing radial clearance, the reduction in airflow excitation became less effective. Meanwhile, the airflow excitation was significantly influenced by the nozzle layout. The single-row nozzle layout exhibited pronounced first-order airflow excitation characteristics and the high-amplitude regions were distributed throughout the entire impeller flow passage. For the double-row staggered nozzle layout, the first-order airflow excitation was greatly diminished, reaching only 50% of the maximum amplitude observed in the single-row layout and the high-amplitude regions were confined to the impeller leading-edge area. This investigation is beneficial for the design of ECS radial flow turbines with novel tubular nozzles.

1. Introduction

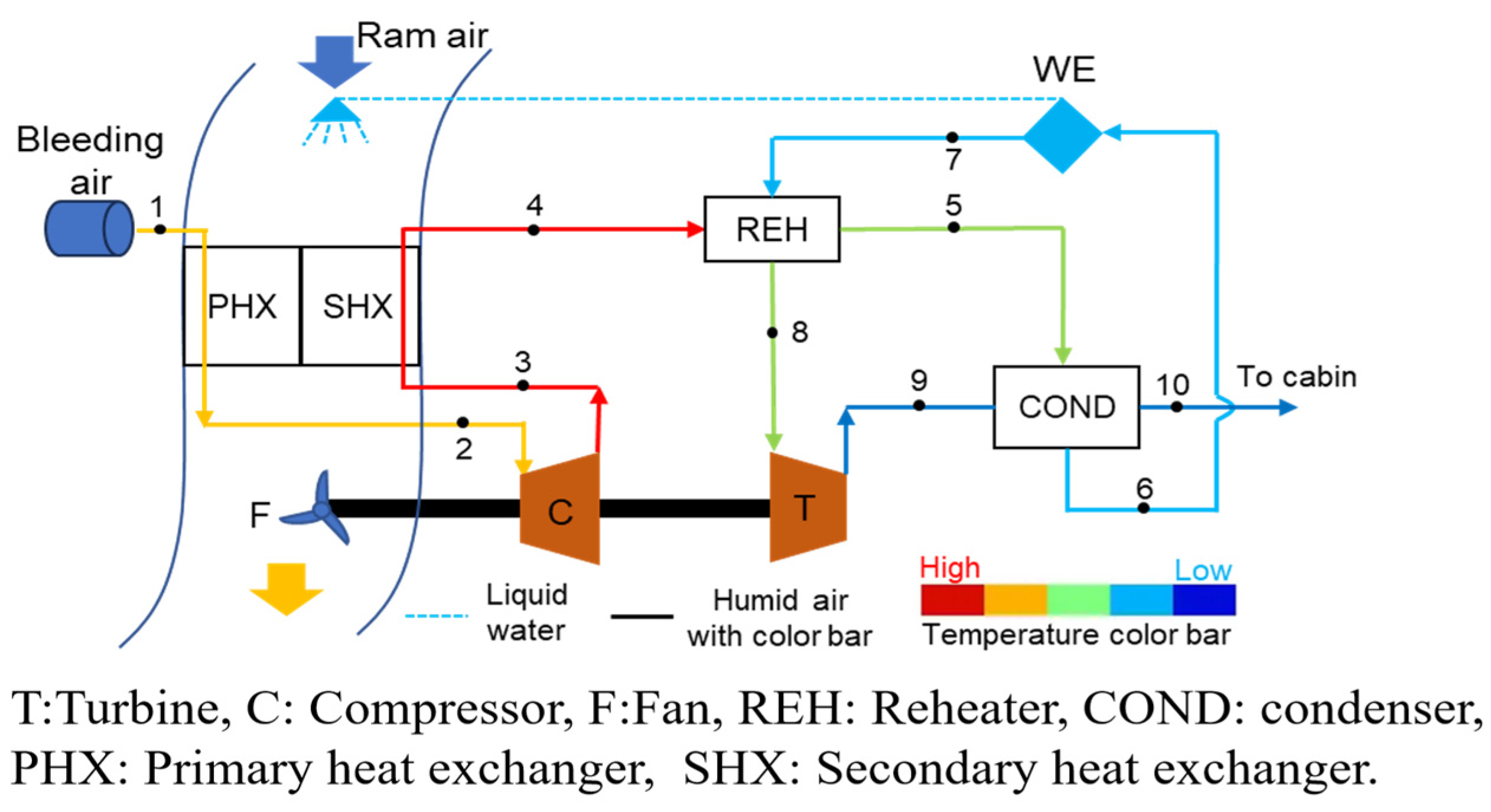

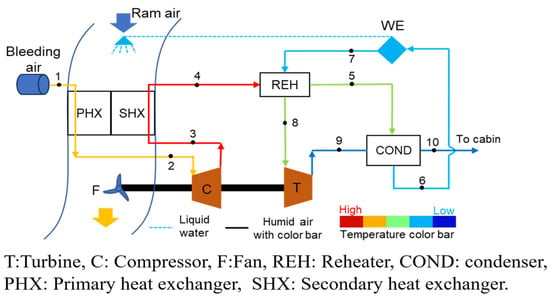

Aircraft ECSs play a critical role in maintaining cabin temperature, pressure stability, and flight safety. The radial flow turbine is a key component of an ECS, utilizing engine bleed air as an energy source to provide cooling air for cabin temperature regulation, as shown in Figure 1. The numbers in Figure 1 represent the flow sequence of the airflow. Under conditions of high rotational speed and a large expansion ratio, strong unsteady airflow excitations are generated around turbine blades as a result of the periodic interaction between the nozzle and the impeller. These excitations can induce forced vibrations, which lead to fatigue failure of the turbine blades. In engineering practice, fatigue fracture incidents frequently take place in ECS radial flow turbines. Existing studies on radial flow turbines used in ECS mainly focus on turbine bearing fault monitoring [1] and on turbine performance and coupling characteristics [2]. In contrast, studies addressing airflow excitation and the resulting fatigue failure of ECS radial flow turbines are rarely reported in the open literature. Therefore, it is necessary to investigate the unsteady airflow excitation characteristics in such high-expansion-ratio radial flow turbines.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of a typical air cycle environmental control system.

Airflow excitation, caused by unsteady aerodynamic forces, is particularly significant under high rotational speeds and complex flow conditions. Unstable flow fields intensify stress concentration in the turbine and obviously reduce the impeller’s fatigue life. Investigations on adjustable nozzle radial flow turbines revealed that rotor–stator interaction, guide vane wake, tip clearance flow, and vorticity fluctuations on the suction surface are primary reasons for impeller vibration [3,4,5,6]. Zhang Hong [7] and Ma [8] systematically investigated the airflow excitation characteristics and dynamic response of radial flow turbine rotor blades using unsteady simulations and fluid–structure interaction methods (FSIs). Their results indicated that first and second harmonic excitations are the main contributors to impeller vibration. Specifically, Ma’s results showed that the forced response analysis aligned well with Singh’s advanced frequency evaluation. Existing studies have also revealed that the combined effects of trailing-edge shock wave, stator wake, and guide vane tip leakage flow lead to significant periodic blade loading variations and high cycle fatigue (HCF) fractures [9,10,11,12,13,14]. Forced impeller vibrations have been investigated by Schwitzke [15] and Kulkarni [16] using experimental testing and fluid–structure interaction approaches. Their results indicated that unsteady excitation amplitude is significantly influenced by rotational speed, the number of guide vanes, and inlet pressure. HCF induced by resonance under unsteady excitation is regarded as a primary challenge in the design of small radial flow turbines. Existing studies have predominantly focused on turbocharger compressors and turbines equipped with conventional vaned or vaneless diffusers or nozzles. However, investigations into the ultra-high-frequency characteristics of airflow excitation induced by rotor–stator interaction in ECS radial flow turbines remain scarce in the literature, particularly for configurations employing novel tubular nozzle structures. A high-frequency airflow excitation of 22,840 Hz has been reported in a previous study [15]. In the present study, the frequency of airflow excitation is approximately twice this value and is classified as ultra-high-frequency excitation.

In this paper, to address the flow-induced failure issues in ECS radial flow turbines with tubular nozzles, numerical simulations and experimental investigations were conducted to examine the formation mechanisms of ultra-high-frequency excitation and potential mitigation strategies. The main contributions of this study are as follows:

- (1)

- The formation mechanisms of ultra-high-frequency excitation in ECS radial flow turbines with tubular nozzles were investigated. The results indicate that rotor–stator interactions are the primary source of airflow excitation.

- (2)

- The effects of the nozzle–impeller radial clearance on airflow excitation were examined. The findings show that increasing radial clearance is beneficial for reducing aerodynamic excitation, but this effect is nonlinear. A balance must also be considered between the reduction in airflow excitation and the accompanying decrease in turbine efficiency caused by enlarging the radial clearance.

- (3)

- The influence of nozzle layout on airflow excitation was investigated. It was observed that, compared with the single-row nozzle configuration, the double-row staggered nozzle layout resulted in a significant reduction in the first-order airflow excitation, with the amplitude decreased by 50%. In contrast, the excitation levels of higher order remained largely unaffected.

The structure of this paper is as follows: Section 2.1 describes the research objects. Section 2.2 and Section 2.3 present the numerical methods. Section 3 outlines the experimental validation methods and results. Section 4.1 presents the time domain results of the radial flow turbine. Section 4.2 discusses the frequency domain characteristics of the static pressure fluctuations on the impeller blades. Section 4.3 describes the airflow excitation characteristics of the turbine impeller. Section 4.4.1 investigates the effects of the nozzle–impeller radial clearance on airflow excitation, and Section 4.4.2 discusses the differences in airflow excitation induced by single-row and double-row staggered tubular nozzle layouts.

2. Methodology

2.1. Research Objects

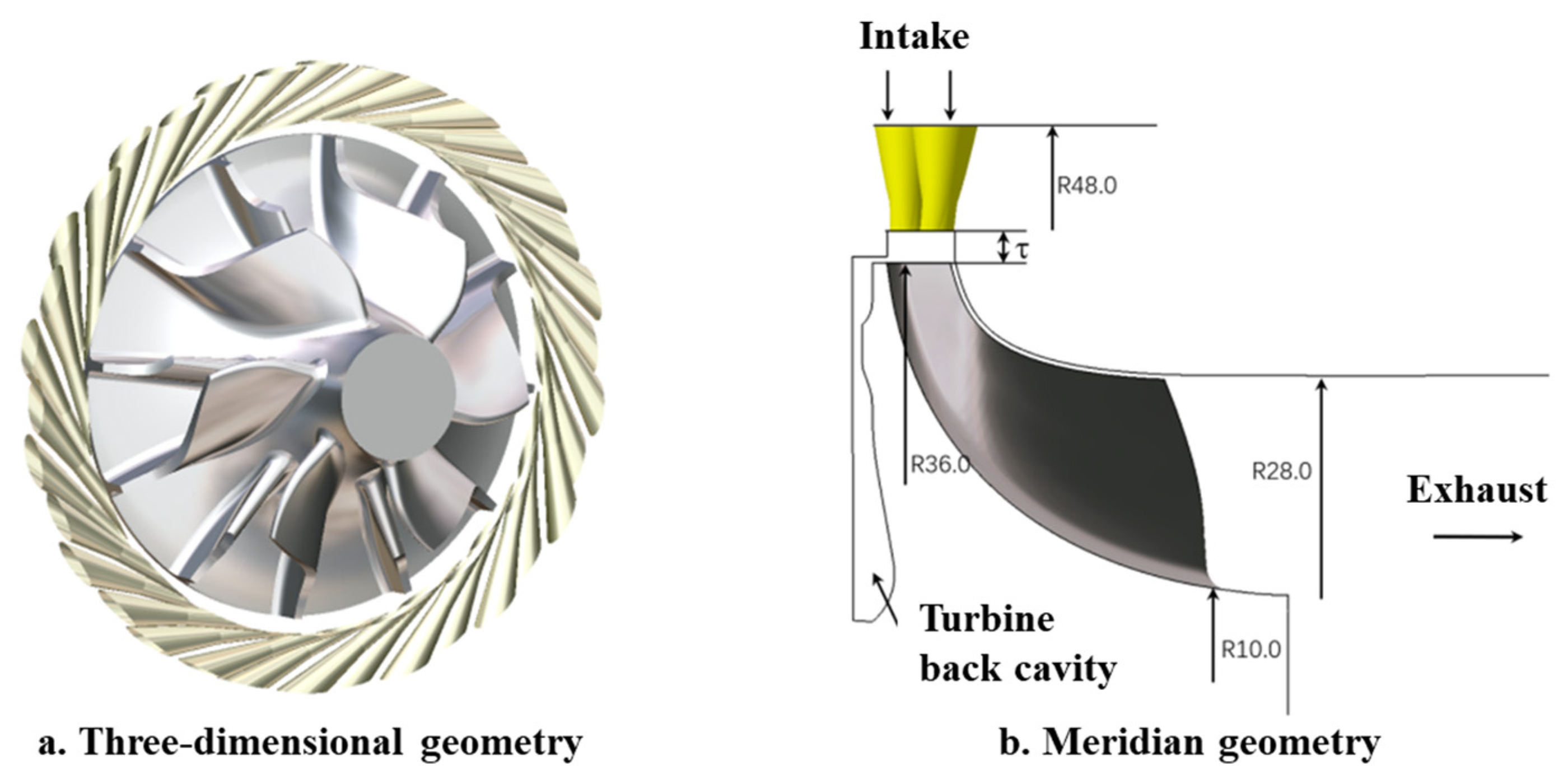

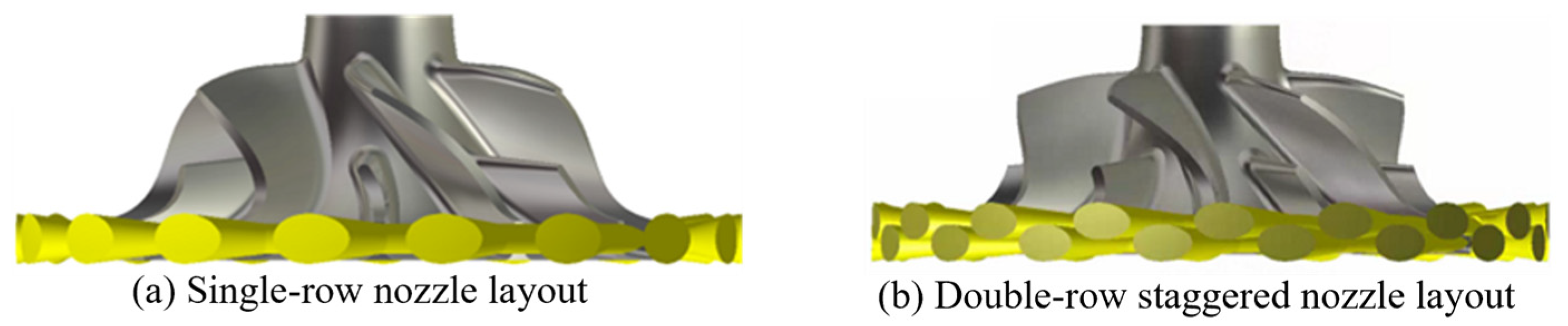

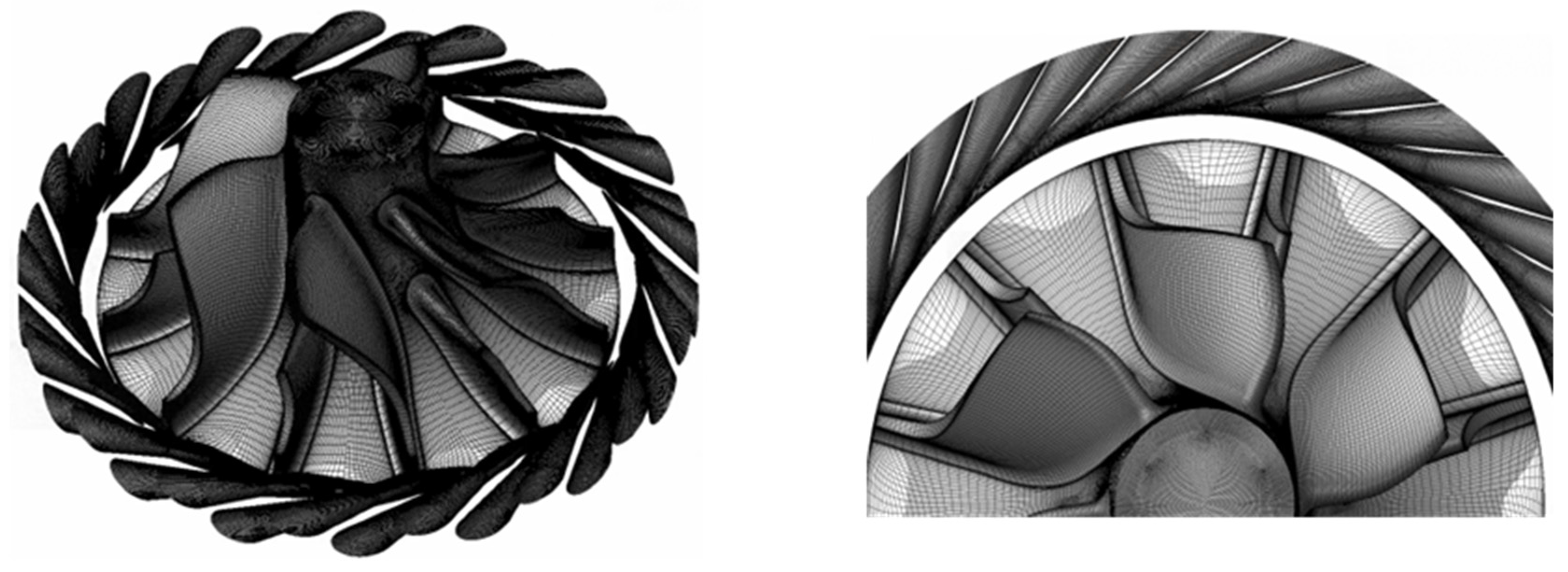

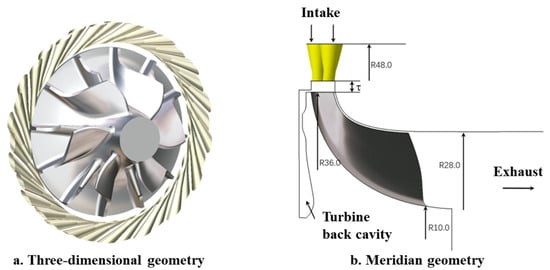

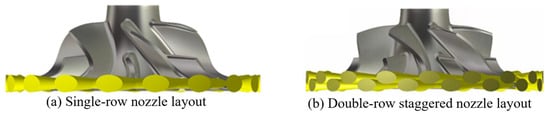

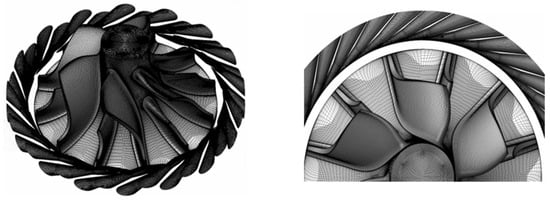

The advanced ECS turbine employs a tubular nozzle structure—Figure 2 presents its three-dimensional and meridian geometry. The impeller has a long–short blade combination layout, with 6 long and 6 short blades. The CFD simulation model includes the impeller back cavity. The radial clearance (τ) between the nozzle and the impeller is 2.5 mm. To investigate the influence of nozzle layout on airflow excitation, single-row (17 nozzles) and double-row staggered (34 nozzles) layouts are considered for comparison, while the total throat area is maintained at the same value to ensure an equivalent mass flow rate. Figure 3 shows the three-dimensional structures for both nozzle layouts, while Figure 4 presents a photograph of the tubular nozzles with the double-row staggered layout. Experimental validation in this study is conducted using the tubular nozzle with a double-row staggered layout.

Figure 2.

Three-dimensional and meridian geometry of the ECS radial flow turbine.

Figure 3.

Three-dimensional structures for both nozzle layouts.

Figure 4.

Photograph of tubular nozzles with the double-row staggered layout.

2.2. CFD Simulation Method

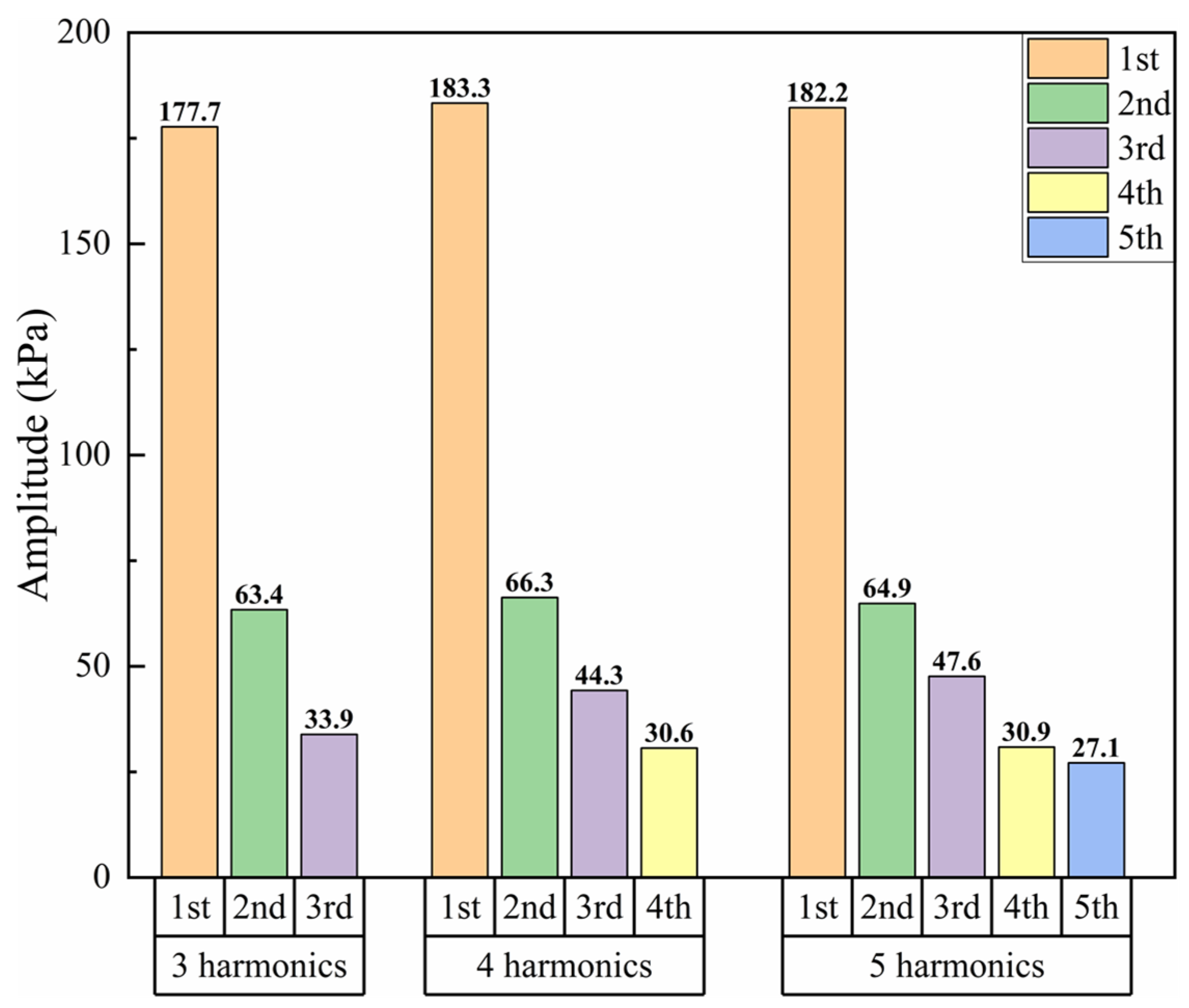

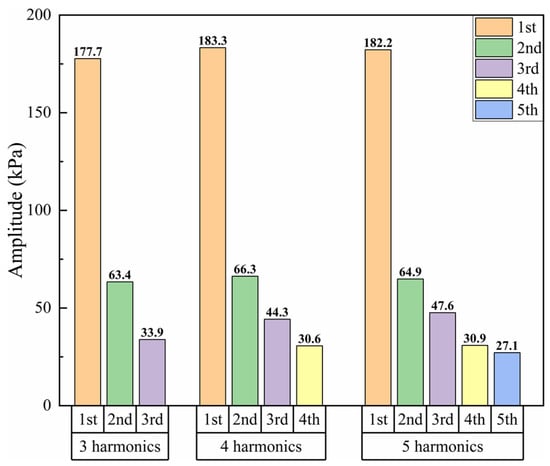

The three-dimensional RANS equations were solved using the FINE/Turbo solver. A cell-centered finite-volume formulation was adopted, in which second-order central spatial discretization was employed. Time integration was performed using a fourth-order Runge–Kutta scheme. Convergence was accelerated using multigrid, variable time steps, and residual smoothing. The SST turbulence model was employed, while unsteady flow fields were obtained via the NLH method with time domain transformation. Figure 5 presents the verification of harmonic order convergence. At a rotational speed of 90,000 rpm, simulations were performed using three, four, and five harmonics. A comparison between the results obtained with three and four harmonics shows pronounced variations in the amplitudes of different harmonic components. The third-order harmonic exhibits the largest change, reaching 30.7%. In contrast, the differences between the results obtained with four and five harmonics are relatively small for all harmonic orders. The maximum variation is again observed for the third-order harmonic, but it is reduced to only 7.4%. Moreover, the amplitude of the fifth-order harmonic is relatively small and is nearly identical to that of the fourth-order harmonic, indicating that the contribution of the fourth and higher-order harmonics is negligible. Therefore, considering both computational accuracy and efficiency, four harmonics are retained in the present study.

Figure 5.

Verification of harmonic order convergence.

The fundamental concept of the NLH approach is that the flow perturbations responsible for unsteady effects are expressed as deviations from the time-averaged flow field and subsequently decomposed into Fourier series in the time domain. For example, the conservation variable can be divided into a time-averaged value and the periodic perturbations . The periodic perturbations can be expressed as a Fourier series comprising an infinite number of frequencies as follows:

where represents the blade passing frequency and represents the complex amplitude associated with the k-th frequency. For turbomachinery, perturbations are predominantly concentrated in the first few frequency components, which permits the truncation of the Fourier series to a finite number of harmonics, denoted by N. The accuracy of the unsteady CFD simulations is determined by the order of the Fourier series. By converting the unsteady Navier–Stokes system to the frequency domain, 2N + 1 sets of coupled equations for the mean flow and real and imaginary parts of each resolved frequency are obtained.

Figure 6 shows the computational mesh for the turbine. The model includes one nozzle passage and one impeller passage, using periodic boundary conditions (representing 17 nozzle periods and six impeller passages). The mesh contains 0.8 million cells for each nozzle passage and 2.8 million cells for each impeller passage, resulting in a total of 3.6 million cells. Boundary conditions are set according to the information shown in Table 1. The inlet total pressure and temperature, as well as the outlet static pressure, are specified. The working fluid is air and all solid walls are treated as adiabatic with no-slip conditions. The rotating walls, including the blades and the backplate, are prescribed to rotate at the speeds listed in Table 1.

Figure 6.

Computational mesh for the turbine.

Table 1.

Performance indicators of environmental control turbine at typical operating points.

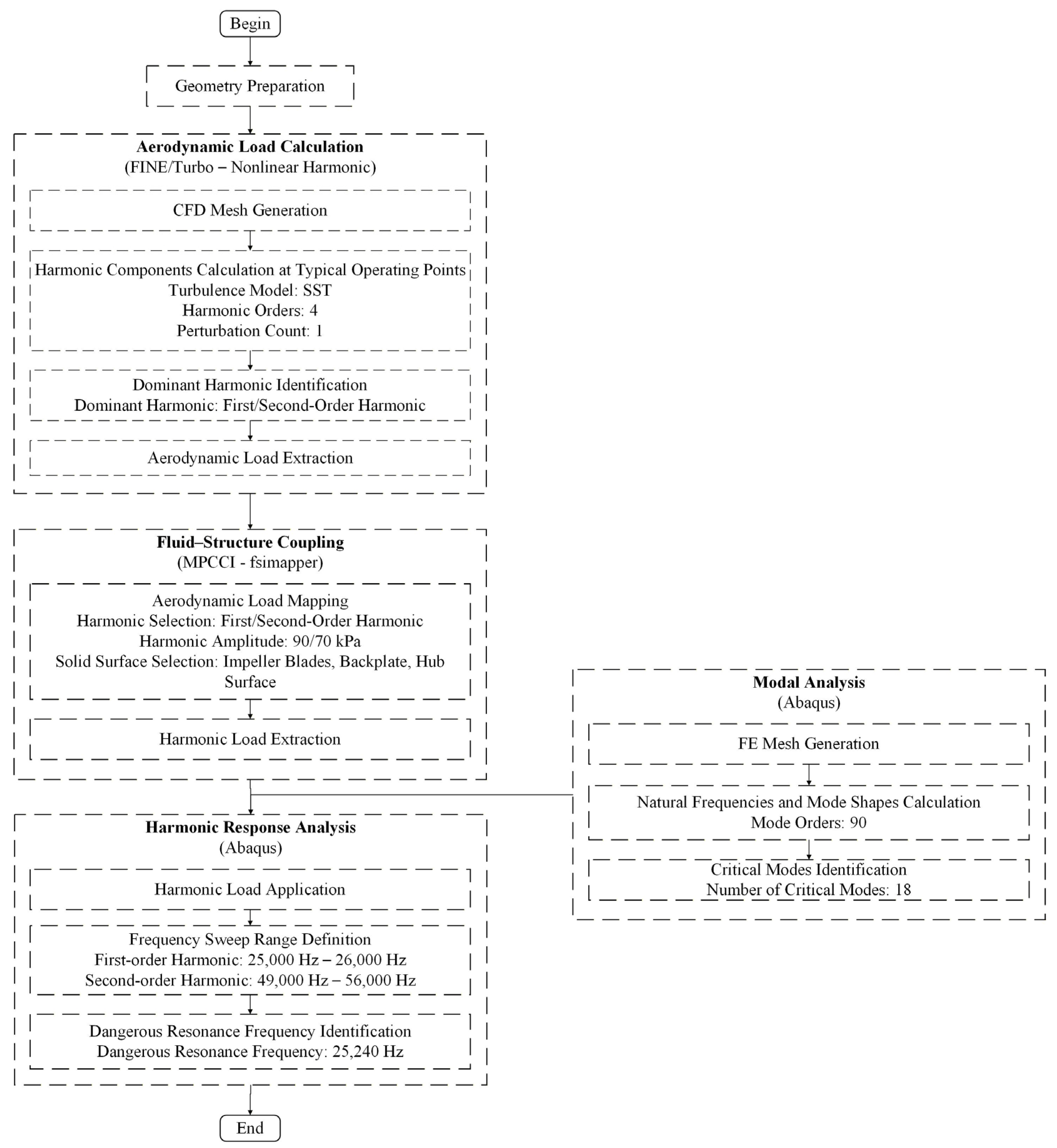

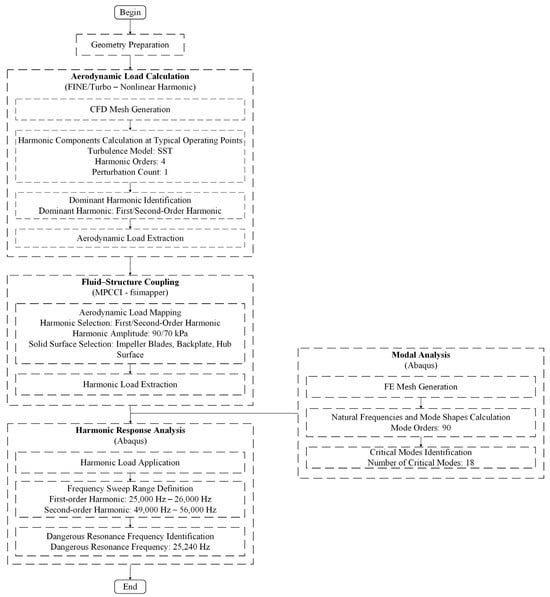

2.3. Harmonic Response Analysis Method

Figure 7 shows the FSI harmonic response analysis process. The workflow includes four parts, i.e., aerodynamic load calculation, one-way FSI, modal analysis, and harmonic response analysis. In the vibration analysis of radial flow turbines, the impeller exhibits high stiffness and damping due to the integrally bladed disk structure. Both experimental and numerical studies generally indicate that this characteristic results in small blade vibration amplitudes under most operating conditions, and the associated influence on the flow field can be neglected. Under these circumstances, the one-way FSI method can predict the vibration response with adequate accuracy, with only limited differences compared with the two-way FSI method. On this basis, the one-way FSI method is applied to predict the vibration response of the turbine [17]. The airflow excitations are computed using the NLH method. The resulting unsteady aerodynamic loads are subsequently mapped onto the finite element model through the fsimapper module of MPCCI. Based on these mapped loads, modal and harmonic response analyses are performed in Abaqus to determine the natural frequencies, mode shapes, vibration responses, and corresponding stress levels under airflow excitation, thereby enabling the assessment of potential resonance risks.

Figure 7.

FSI harmonic response analysis process.

As the foundation of harmonic response analysis, modal analysis can be used to determine the natural frequencies and the mode shapes. The free vibration equation of the undamped system is defined as follows:

where and represent the mass matrix and the stiffness matrix, respectively; and represent the displacement vector and acceleration vector, respectively.

Assuming that the free vibration is a simple harmonic motion, the displacement vector satisfies the equation as follows:

By substituting Equation (2) into Equation (1), Equation (3) can be obtained as follows:

Equation (3) is a generalized eigenvalue problem. The determinant of the coefficient matrix is 0 when the equation has non-zero solutions as follows:

where eigenvalues and eigenvectors represent the square of natural frequencies and the mode shapes, respectively.

Harmonic response analysis is a frequency domain approach used to determine the steady-state response of a structure subjected to periodic simple harmonic loading. Within this framework, the equation of motion for a multi-degree-of-freedom system is expressed as follows:

where represents the damping matrix; represents the velocity vector; and represents the load vector.

For a periodically varying harmonic load, the load vector can be written as

where represents the load phase angle; and represent the real and imaginary components of the load; and represents the load frequency.

The harmonic load is mapped using the airflow excitation obtained by the NLH approach. The computation based on the NLH approach is performed on a single-passage domain. However, interpolation to the structural domain requires full-annulus results. Therefore, when reconstructing the full-annulus solution from the single-passage results, the nodal diameter is required to satisfy the following criterion:

where represents the harmonic order; and represent the number of stators and rotors; and represents the nodal diameter.

Equation (8) indicates the relationship between the harmonic order and the nodal diameter. For the ECS turbine investigated in this study, based on the numbers of rotor blades and nozzles, the first-order excitation corresponds to the one-nodal-diameter mode, the second-order excitation to the two-nodal-diameter mode, the third-order excitation to the three-nodal-diameter mode, and the fourth-order excitation to the two-nodal-diameter mode.

The solution of Equation (6) can be written as follows:

where and represent the real and imaginary components of the displacement.

By substituting Equation (6) into Equation (7), Equation (5) can be obtained as follows:

Considering the arbitrariness of the displacement, the eigenvalue equation is obtained as follows:

Harmonic response analysis is performed to evaluate the steady-state response of the turbine wheel under harmonic excitation. The critical resonance points are subsequently determined by the corresponding frequency–response curves.

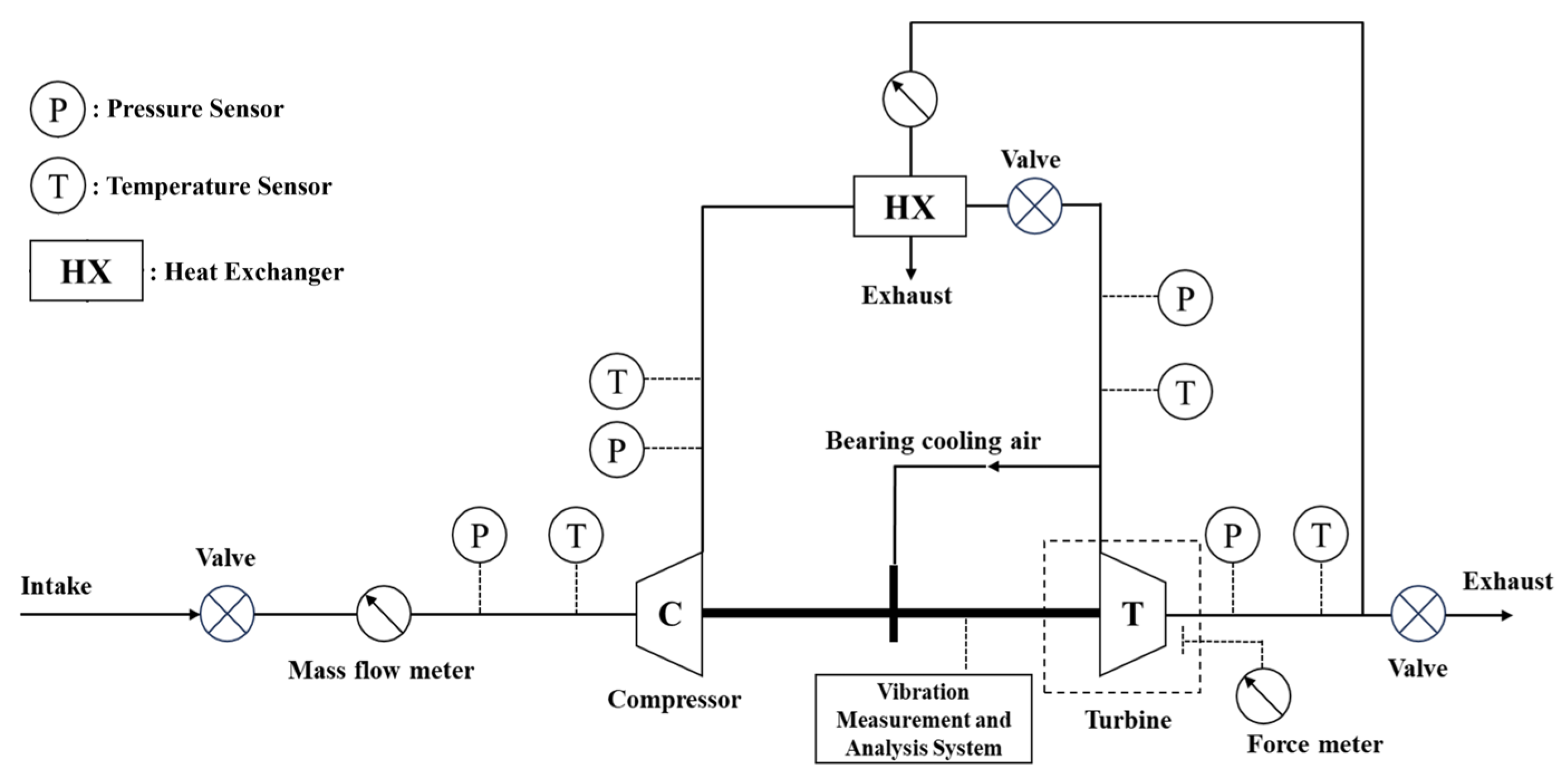

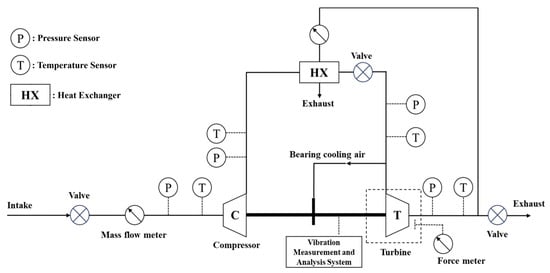

3. Turbine Vibration Testing and Performance Validation

Vibration testing indirectly reflects rotor response under high-frequency excitation, while frequency domain analysis helps reproduce fatigue fractures and validate numerical predictions. Figure 8 shows the schematic diagram of the aircraft turbine cooler ground performance test rig. The cooler consists of a compressor unit and a turbine unit. The turbine drives the coaxial compressor, high-precision pressure and temperature sensors are installed at the inlet and outlet of both units. The rig simulates engine bleed air entering the compressor. After compression, high-temperature and high-pressure air is cooled in a heat exchanger before expanding in the turbine. Part of the cooled exhaust air is used as a heat sink in the exchanger.

Figure 8.

Schematic diagram of the aircraft turbine cooler ground performance test rig.

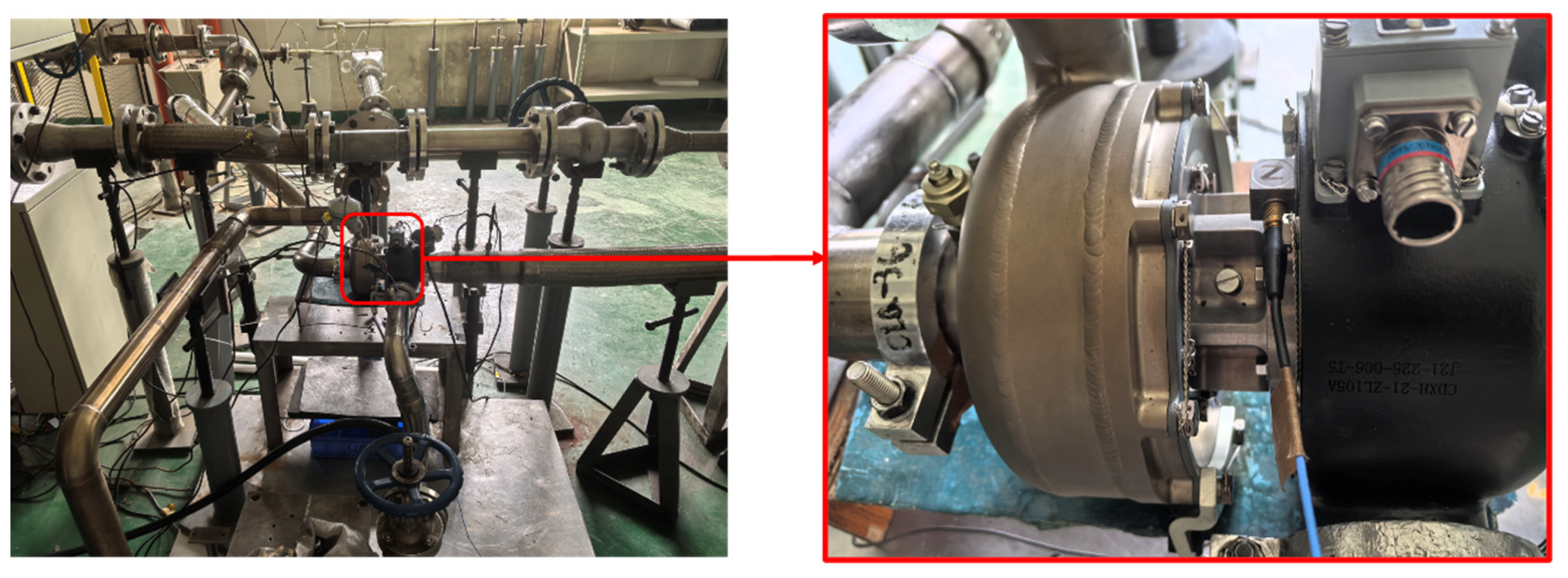

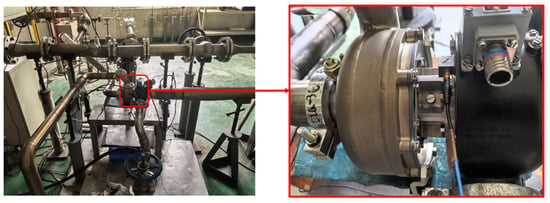

The turbine cooler has five typical operating conditions within the flight envelope. The working conditions for the turbine unit are listed in Table 1, where inlet temperature and pressure, as well as the outlet pressure, are control parameters, while rotating speed and outlet temperature are measured. Vibrations are measured using a piezoelectric accelerometer. Figure 9 shows an on-site photo of the vibration test of an aircraft turbine cooler; the sensors used in the test are listed in Table 2.

Figure 9.

On-site photo of the vibration test of an aircraft turbine cooler.

Table 2.

Statistical analysis of sensor usage in ECS turbine performance testing.

Turbine efficiency, crucial for cooling capacity, is tested and numerically validated. Total-to-static efficiency is calculated using the following equation:

where Tti and Tto represent the inlet and outlet total temperatures, respectively, and represents the total-to-static expansion ratio.

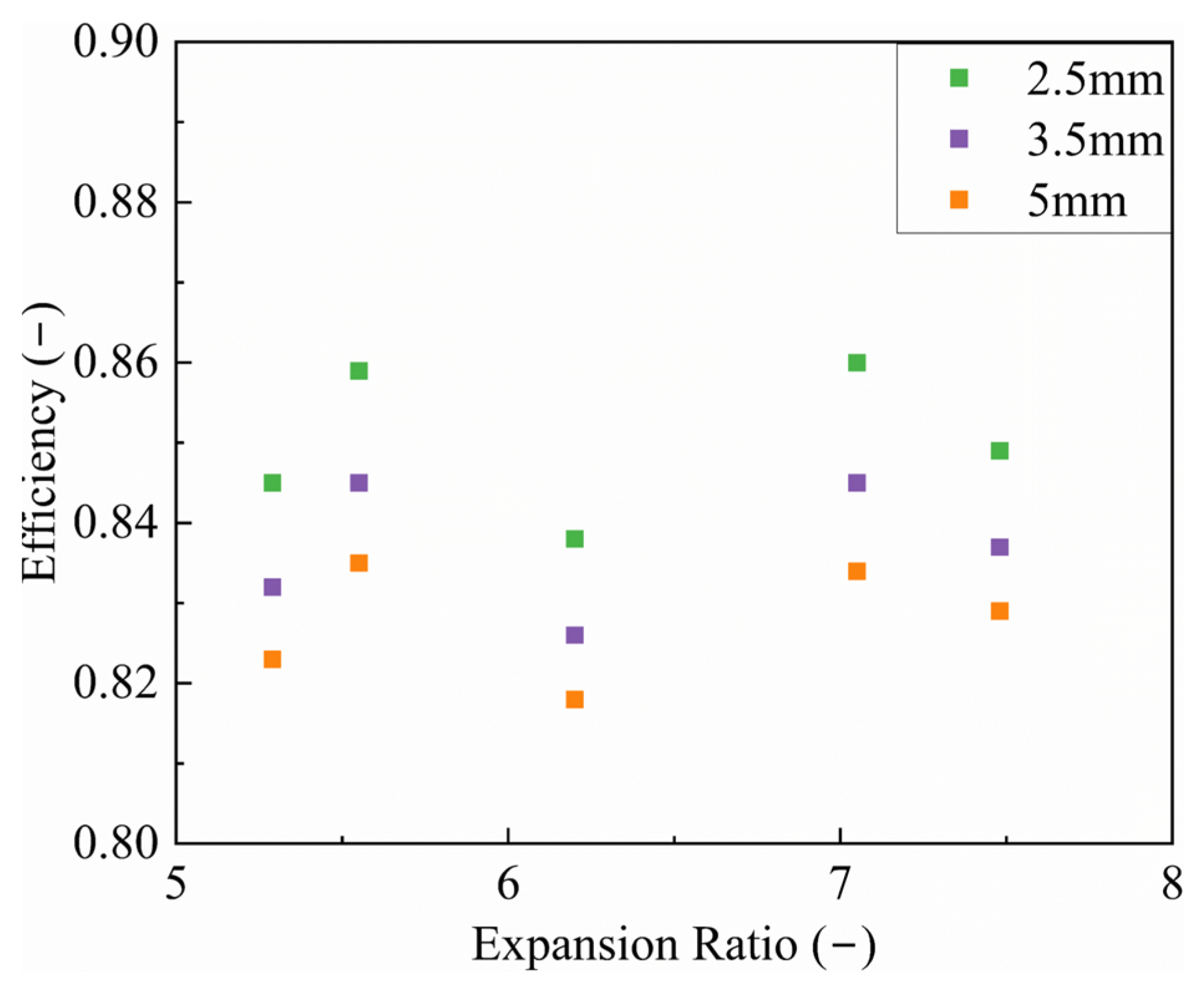

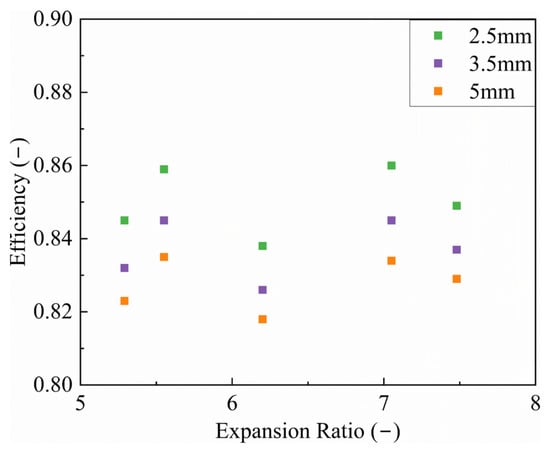

where Pti and Pto represent the inlet and outlet total pressure.

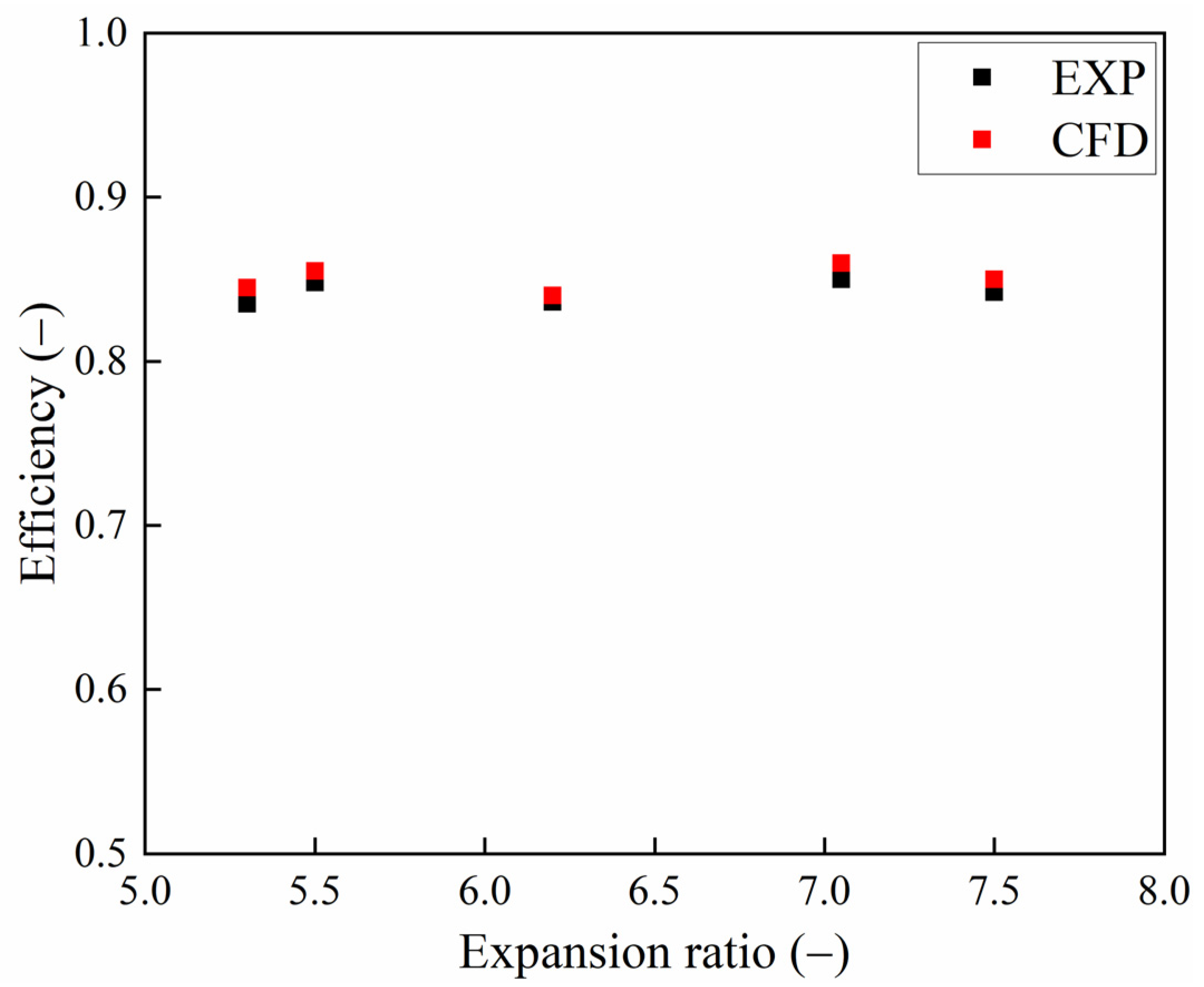

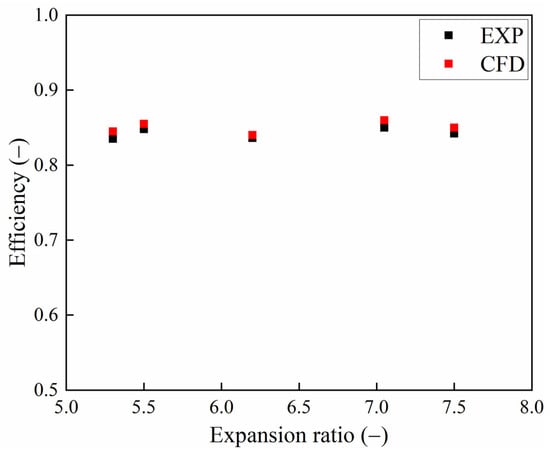

Figure 10 shows the comparison of numerical and experimental turbine efficiency under typical operating conditions. The design point (expansion ratio 7.05) has the highest efficiency, while conditions near the design point (e.g., expansion ratio 5.5) also show high efficiency (0.848). Under the operating condition with a pressure ratio of 6.2, which is further away from the design point, a reduction in efficiency is observed. Overall, the numerical predictions show good agreement with the experimental results, with discrepancies remaining within 2%, confirming the reliability of the CFD model.

Figure 10.

Comparison of numerical and experimental turbine efficiency under typical operating conditions.

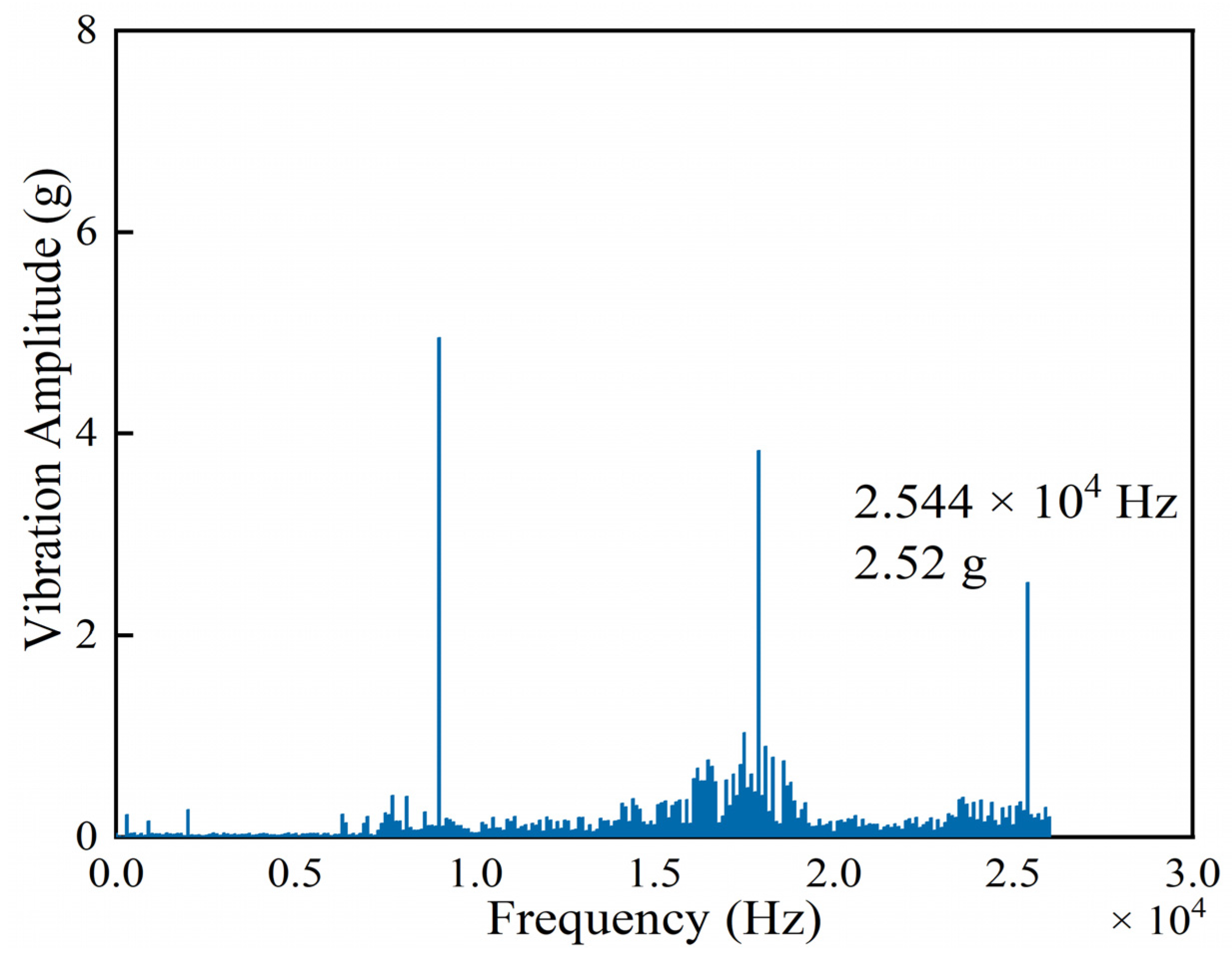

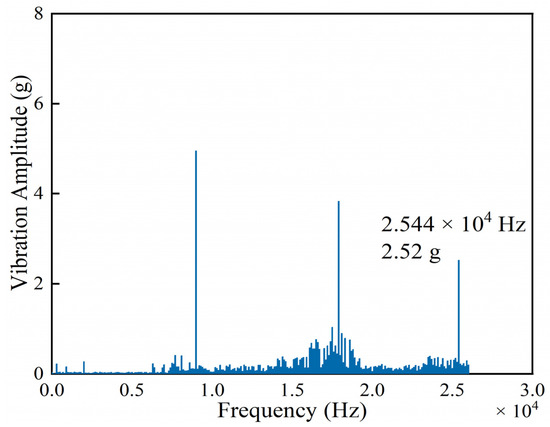

Under all tested operating conditions, the vibration spectra exhibit pronounced peaks at sixfold and twelvefold multiples of the rotational frequency, which can be attributed to the turbine blade passing frequencies. Figure 11 shows the frequency spectrum of the ECS radial flow turbine at 90,000 rpm. A significant vibration peak is observed at 25,440 Hz with an amplitude of 2.52 g when the rotational speed reaches 90,000 rpm. This frequency is equal to 17 times the shaft rotational frequency, consistent with the nozzle count, suggesting that the observed vibration originates from rotor–stator interaction. For the other four operating conditions, no significant vibration at the 17× rotational frequency is detected, indicating that the excitation frequency does not coincide with the natural frequencies of the blades and therefore fails to induce resonance.

Figure 11.

Frequency spectrum of the ECS radial flow turbine at 90,000 rpm.

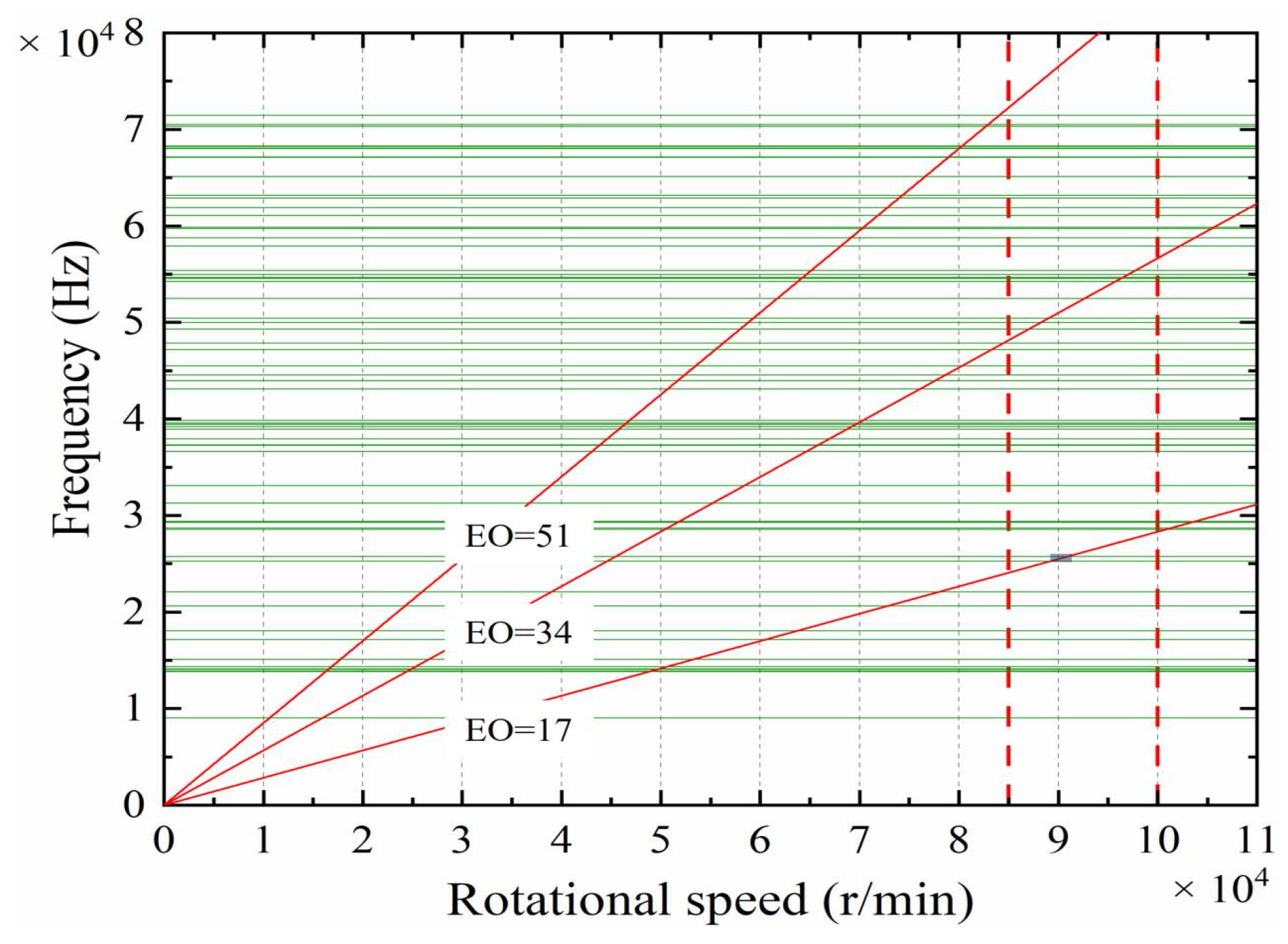

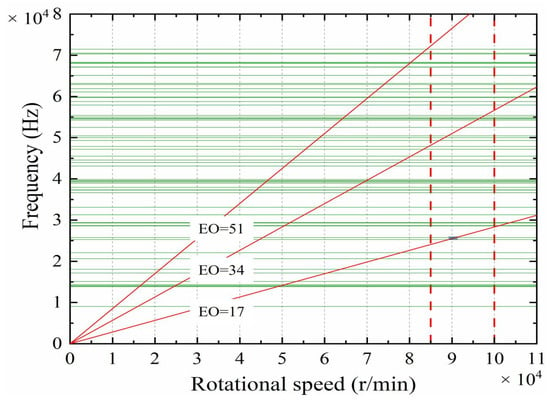

The impeller is made of 2A12 aluminum alloy; Table 3 lists the material properties of the 2A12 aluminum alloy, which is used in the modal analysis and harmonic response analysis. Modal analysis is performed to compute the first 90 natural modes. Figure 12 shows the Campbell diagram of the turbine impeller, where multiple intersections between the first- and second-order excitation lines and the natural frequency branches can be observed. The green lines represent the natural frequencies of the impeller, and the red dotted lines indicate the typical operating speed range of the turbine. Within the scope of this study, the turbine operates in a normal rotational speed range of 85,000–100,000 rpm. Taking the impeller rotational frequency as the fundamental frequency, the high-speed relative motion between the impeller and the nozzles results in multiple airflow excitation components. For the staggered nozzle configuration with 17 nozzles per row, the first-order airflow excitation occurs at 17 times the fundamental frequency (excitation order, EO = 17), while the second-order excitation appears at 34 times the fundamental frequency (EO = 34). In addition, higher-order excitations (EO ≥ 51) are also induced on the impeller.

Table 3.

Mechanical properties of 2A12 aluminum alloy.

Figure 12.

Campbell diagram of the turbine impeller.

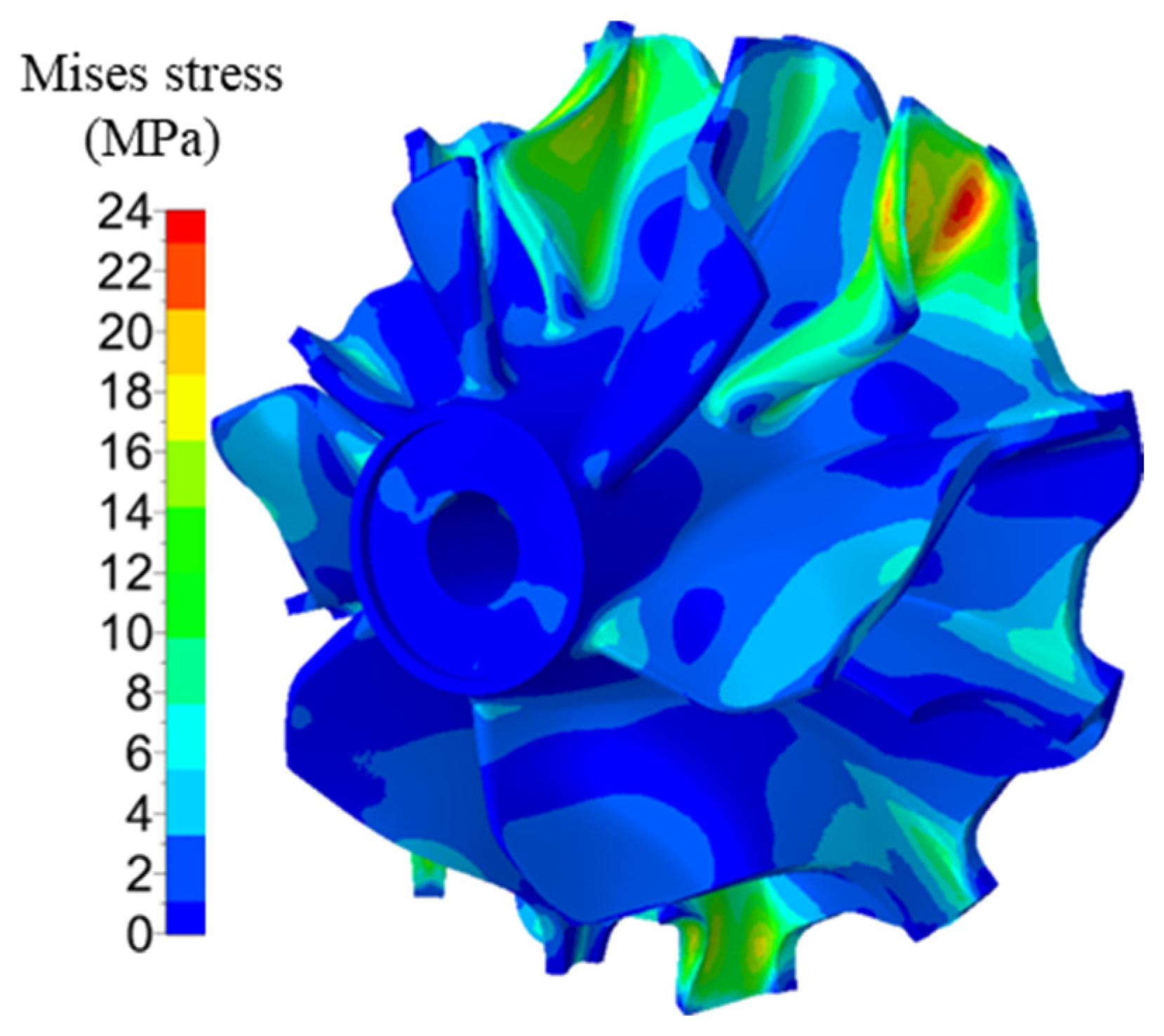

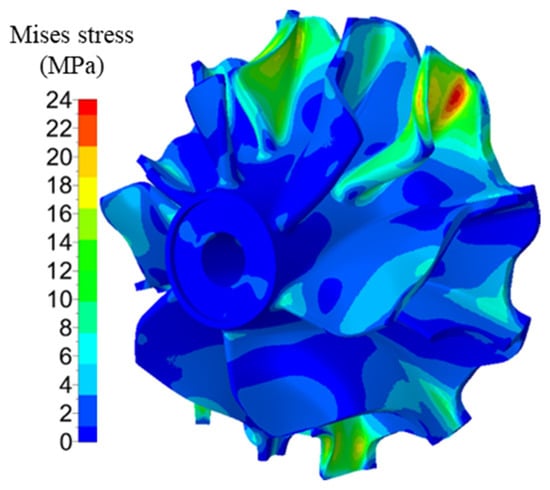

Based on the airflow excitation at 90,000 r/min, harmonic response analyses were conducted at each intersection. Among all the critical resonance points, the maximum von Mises stress occurs at 25,240 Hz, which corresponds to a rotational speed of 89,082 rpm, which is in good agreement with the experimental results. Figure 13 shows the equivalent stress distribution of the turbine impeller at 25,240 Hz. The maximum von Mises stress amplitude was 23.75 MPa, located at the blade root near the leading edge of a small blade. The high-stress regions on the impeller are consistent with the actual failure locations observed in turbine impellers, as shown in Figure 14, indicating a strong correlation between the numerical predictions and actual failure characteristics.

Figure 13.

Equivalent stress distribution of turbine impeller at 25,240 Hz.

Figure 14.

Photograph of the damaged turbine impeller.

4. Results and Analysis

4.1. Time Domain Flow Characteristics

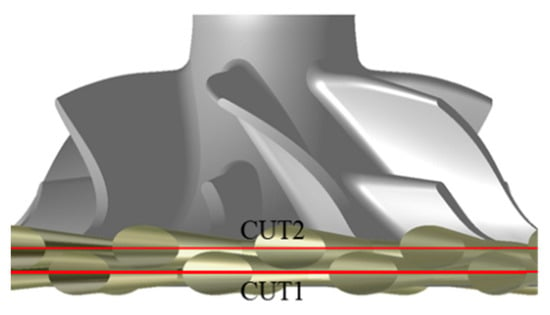

To elucidate the flow field characteristics and the associated static pressure variation induced by rotor–stator interaction, the transient static pressure behavior at two internal turbine cross-sections was examined under the operating condition of 90,000 rpm. Figure 15 illustrates the locations of the two cross-sections. The red lines indicate the locations of the CUT1 and CUT2 sections. CUT1 and CUT2 are axial sections, each representing the mid-plane of two adjacent staggered nozzles.

Figure 15.

Schematic of cross-section locations.

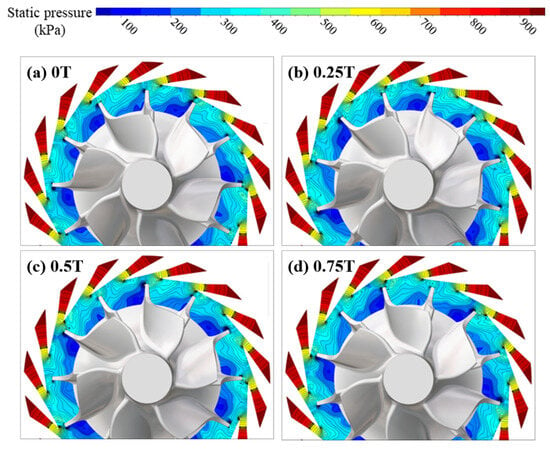

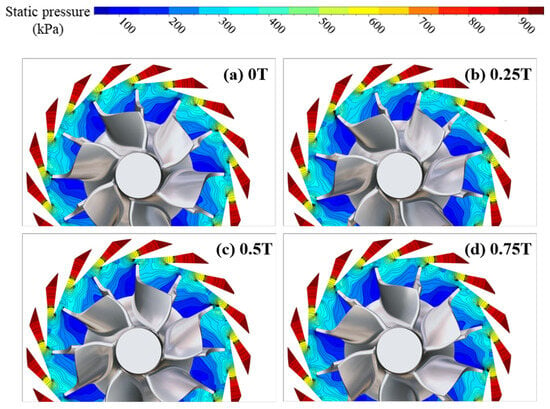

Figure 16 presents the instantaneous static pressure distributions at the CUT1 section for the double-row staggered nozzle layout at 90,000 rpm. When the impeller rotates circumferentially relative to the nozzles, the static pressure in the regions away from the rotor–stator interaction interface, e.g., the nozzle inlet, has no significant variation. However, near the rotor–stator interface, such as at the beveled portion of the nozzle exit and the leading-edge region of the impeller inlet, the static pressure distribution exhibits substantial changes. For example, when the impeller’s leading edge sweeps past the trailing edge of one nozzle and moves towards the trailing edge of the adjacent nozzle, it causes the low-pressure zones near the exits of the two nozzles to gradually shift circumferentially. This results in a corresponding periodic increase and decrease in static pressure at the leading edge of the impeller inlet. On the CUT1 section, the region with the largest static pressure variation within the impeller is located on the suction side of the leading edge, followed by the pressure side of the leading edge. Similar phenomena are observed for both the long and short blades of the turbine impeller. Figure 17 shows the instantaneous static pressure distributions at the CUT2 section. Similarly to the CUT1 section, static pressure variations occur near the rotor–stator interface, especially in the nozzle exit region and the leading edges of the impeller blades. For the impeller blades, the amplitude of static pressure variation is largest on the suction side of the leading edge and smaller on the pressure side. As the flow develops downstream within the impeller passage, the amplitude of static pressure variation gradually attenuates. Compared with the CUT1 section, the flow inside the nozzles at the CUT2 section is generally similar. However, the low-pressure region near the suction-side leading edge of the rotor at CUT2 is wider. Since the pressure in the low-pressure region is less affected by the nozzles, this indicates that the potential pressure fluctuations at the CUT2 section are smaller.

Figure 16.

Instantaneous static pressure distributions at the CUT1 section for the double-row staggered nozzle layout at 90,000 rpm.

Figure 17.

Instantaneous static pressure distributions at the CUT2 section for the double-row staggered nozzle layout at 90,000 rpm.

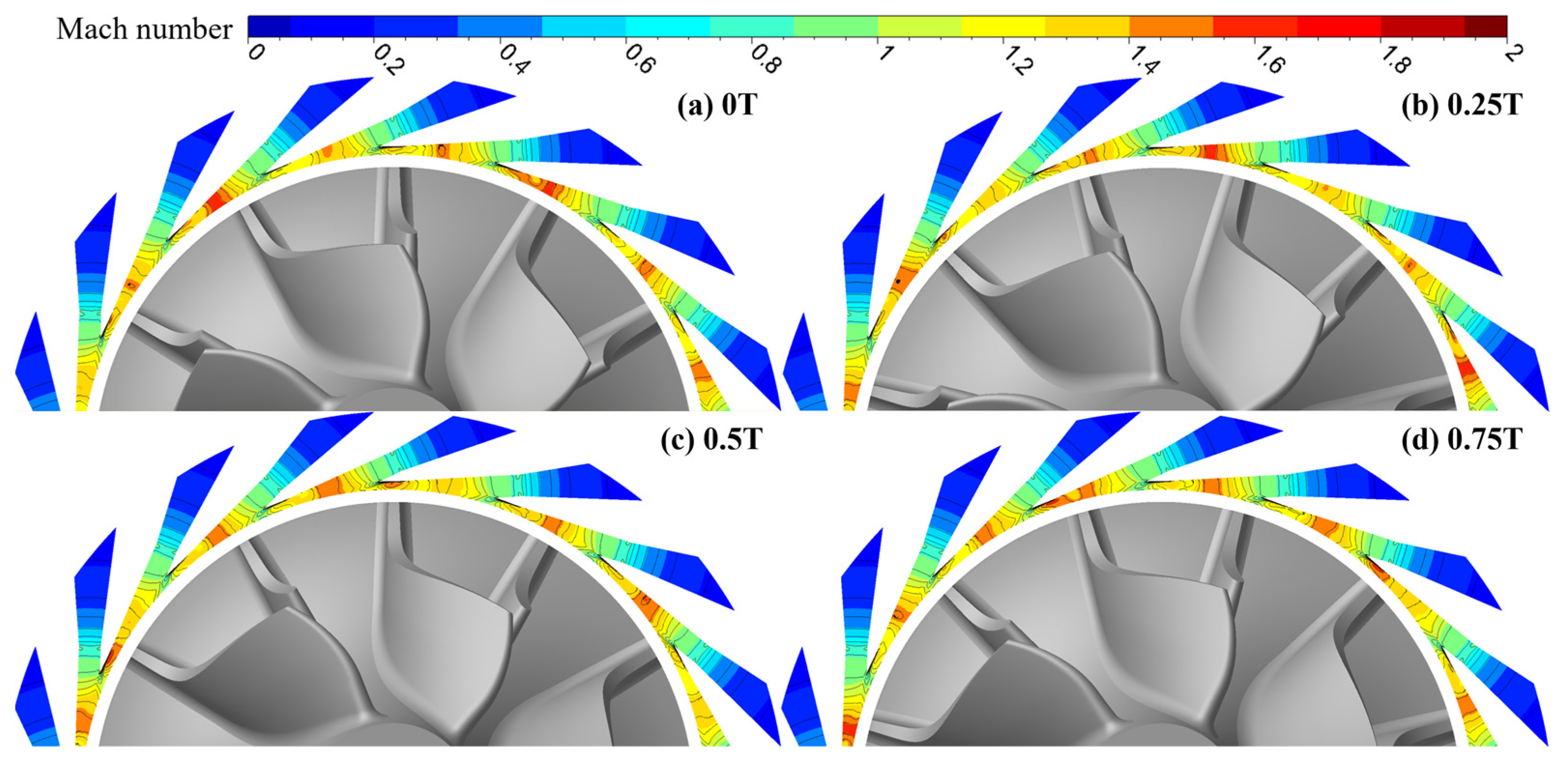

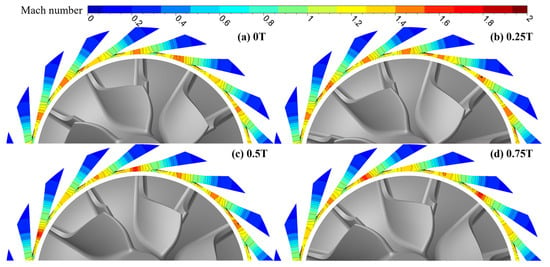

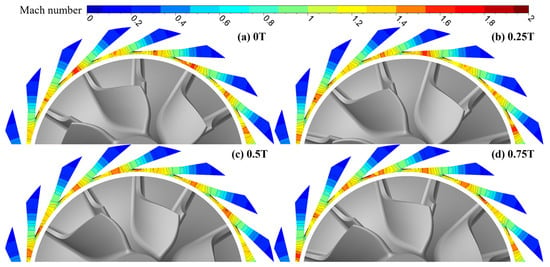

Figure 18 and Figure 19 present the instantaneous Mach number distributions inside the nozzle at the CUT1 and CUT2 sections for the double-row staggered nozzle layout at 90,000 rpm, respectively. After entering the nozzle, the flow accelerates uniformly. The flow reaches sonic conditions at the beveled section of the nozzle and continues to accelerate downstream, with the maximum Mach number reaching approximately 1.8. As the blade leading edge rotates to different positions, the Mach number at the nozzle exit varies periodically, reflecting the effect of rotor–stator interaction. With the current tubular nozzle design, no shock waves are observed at the nozzle exit. Therefore, the primary source of excitation acting on the rotor originates from the rotor–stator interaction between the nozzle and the impeller.

Figure 18.

Instantaneous Mach number distributions inside the nozzle at the CUT1 section for the double-row staggered nozzle layout at 90,000 rpm.

Figure 19.

Instantaneous Mach number distributions inside the nozzle at the CUT2 section for the double-row staggered nozzle layout at 90,000 rpm.

4.2. Frequency Domain Flow Characteristics

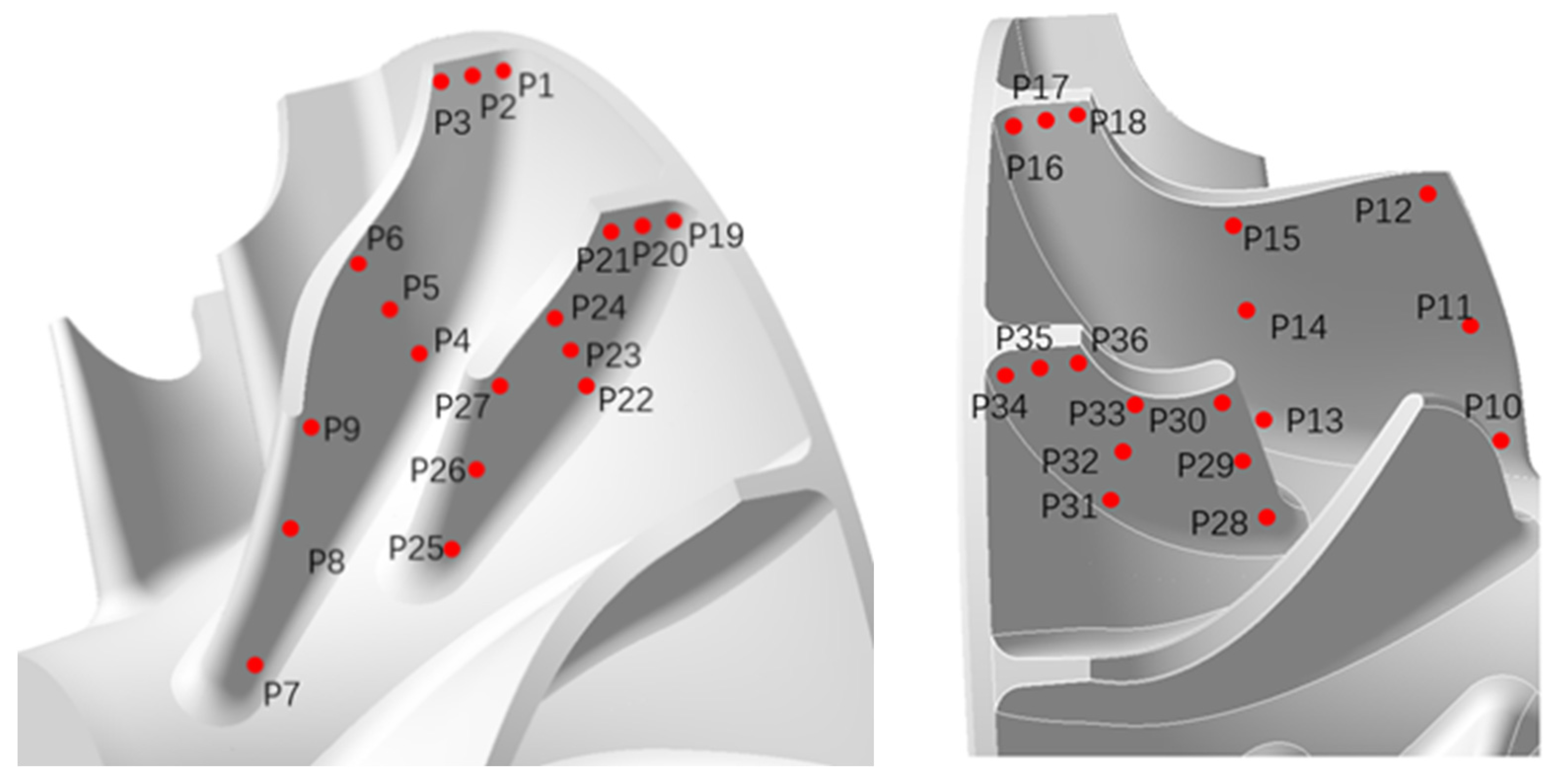

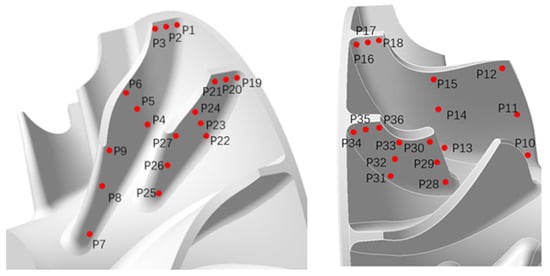

The frequency domain characteristics of static pressure fluctuations on the impeller blade surface were analyzed for the double-row staggered nozzle configuration to identify the primary sources and magnitudes of airflow excitation within the turbine. Figure 20 provides a schematic of static pressure monitoring point locations on the turbine blade. Points 1–36 denote the 36 static pressure monitoring points. Points P1–P18 are located on the surface of the long blades, while points P19–P36 are on the short blades, distributed at different blade heights and streamwise positions. The pressure fluctuations at each point can directly reflect the strength of unsteady airflow excitation and the disturbance frequency at different locations.

Figure 20.

Schematic of static pressure monitoring point locations on the turbine blade.

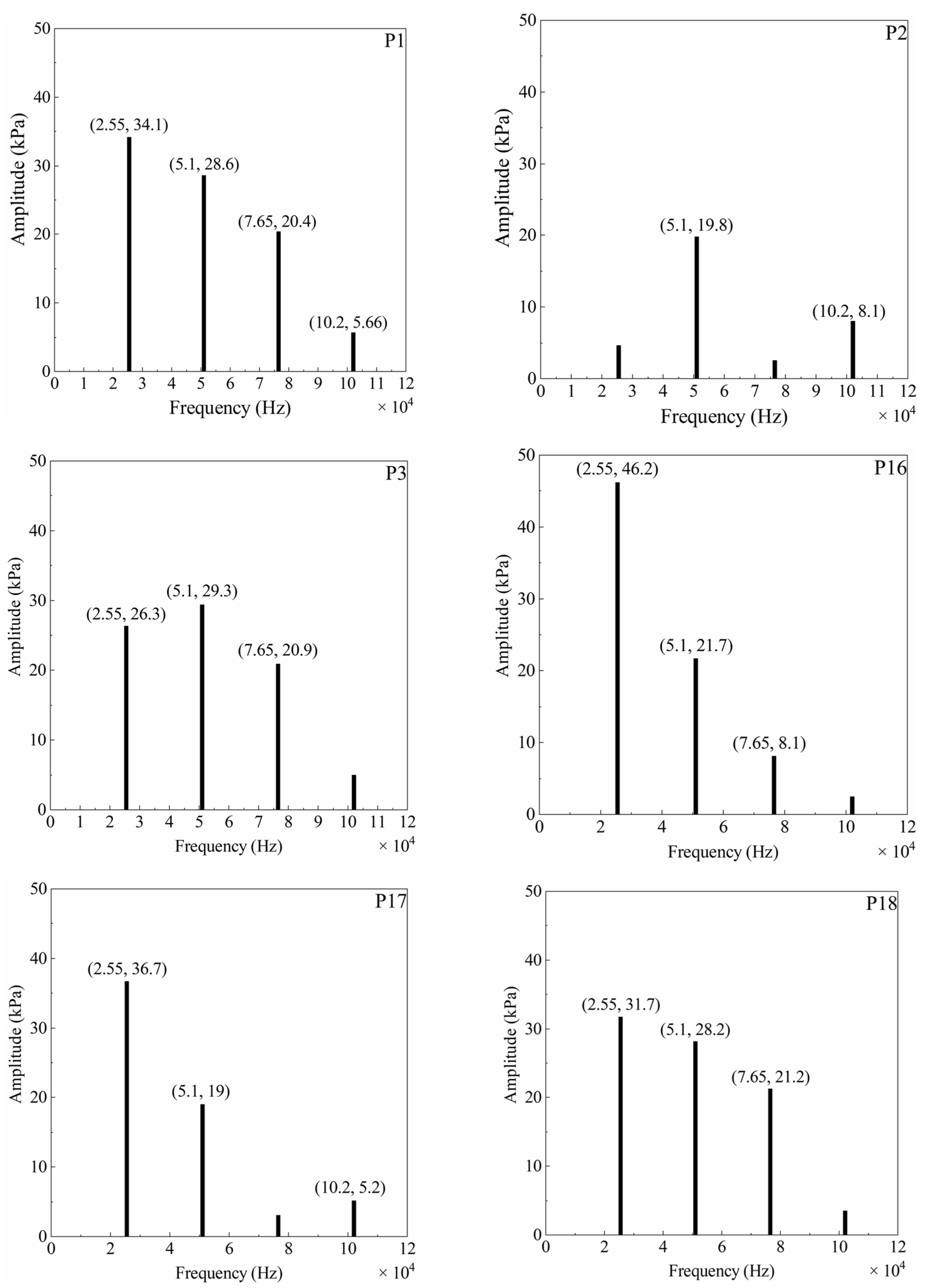

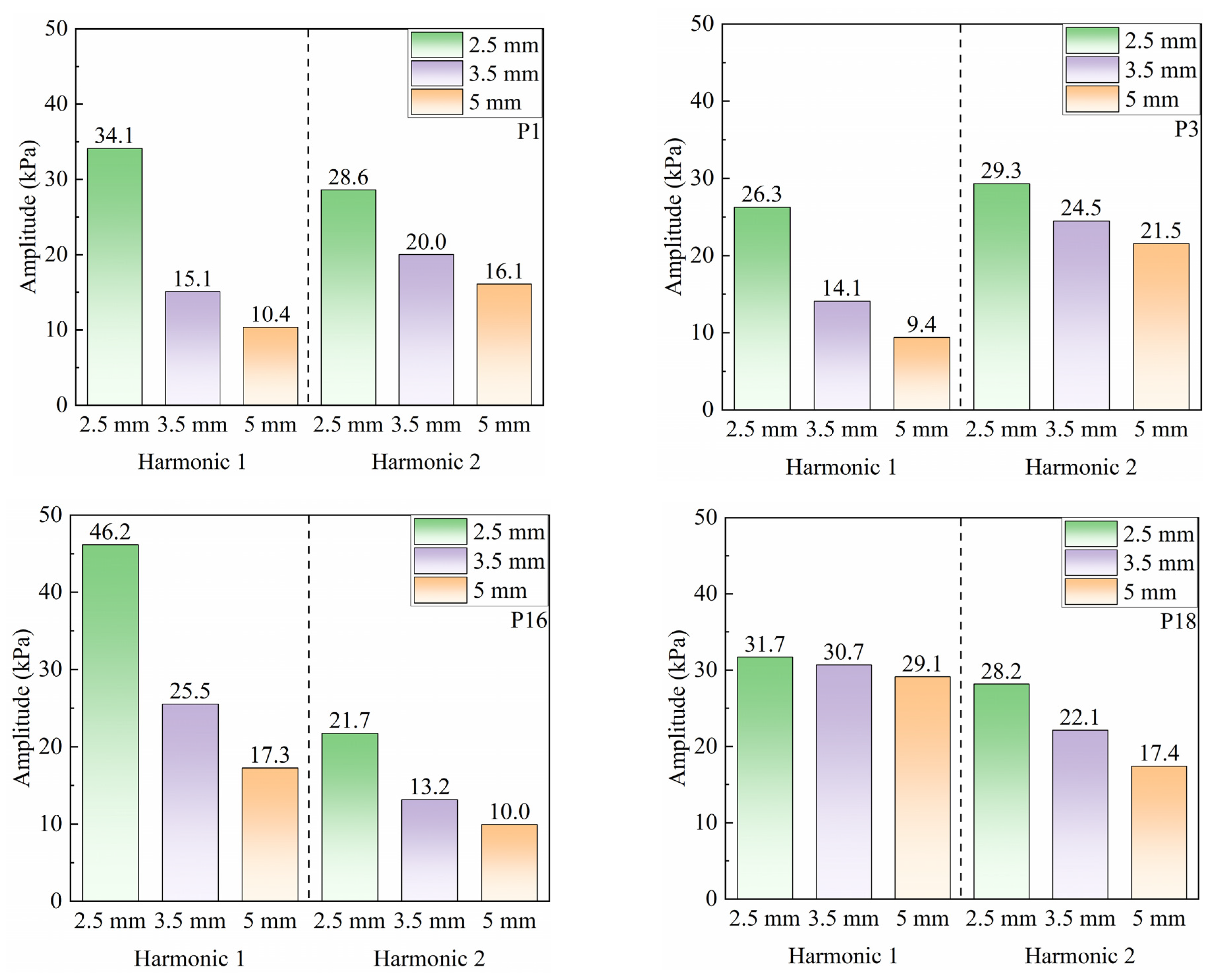

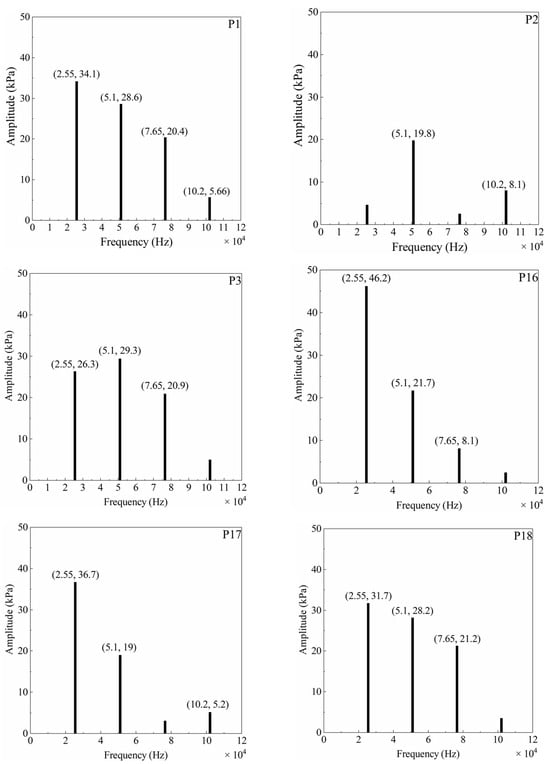

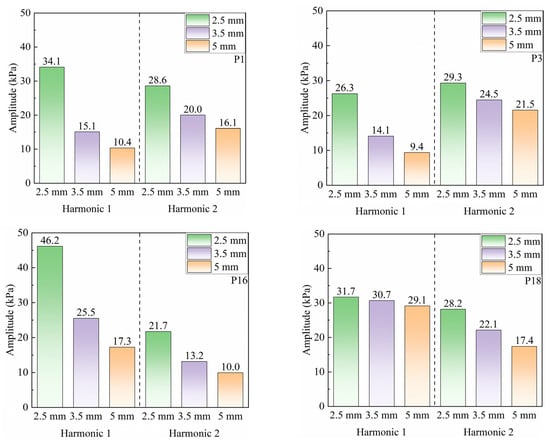

Comparing the airflow excitation amplitudes at all monitoring points, the highest amplitudes are found at the leading edge of the impeller blades. Therefore, monitoring points at the leading edge of the long blades are selected for frequency domain analysis. By comparing the airflow excitation amplitudes across all monitoring points, it was observed that the highest amplitudes occurred at the leading edges of the impeller blades. Consequently, the monitoring points located on the leading edges of the long blades were selected for subsequent frequency domain analysis. Figure 21 shows the frequency characteristics of static pressure fluctuations at the turbine blade monitoring points P1–P3 and P16–P18. At a turbine speed of 90,000 rpm and with 17 sets of nozzles, the fundamental disturbance frequency caused by the impeller rotation, i.e., the Blade Passing Frequency (BPF) is 25.5 kHz.

Figure 21.

Frequency domain characteristics of static pressure fluctuations at the turbine blade monitoring points for the double-row staggered nozzle layout at 90,000 rpm.

Points P1–P3 are located on the pressure side of the long blade leading edge, from the blade root to the tip. Excitations with distinct amplitudes are identified at the nozzle blade passing frequency (25.5 kHz) and its subsequent harmonics. The frequency domain characteristics of static pressure fluctuations at the three monitoring points indicate that the leading edge on the pressure side of the long blade is subjected to pronounced airflow excitation, which is induced by rotor–stator interaction with the nozzle rows.

In both the tip region (P3) and the root region (P1), the amplitudes of the first three excitation orders are relatively high. The highest amplitude in the tip region is the second-order excitation, reaching 29.3 kPa, while the most prominent in the root region is the first-order excitation, with an amplitude of 34.1 kPa. In the mid-span region (P2), the amplitudes of the first- and third-order harmonics are markedly reduced. The second-order excitation is found to be dominant. This suggests that, in the mid-to-high-span region near the blade leading edge, the second-order excitation dominates over the first-order excitation.

Points P16–P18 are located on the suction side of the long blade leading edge, from the root to the tip. Compared with the pressure side, the amplitudes of the first-order airflow excitation are significantly higher and increase progressively from the tip toward the root, reaching 31.7 kPa, 38.7 kPa, and 46.2 kPa, respectively. At these three points, the first two excitation orders exhibit significant amplitudes, while a relatively distinct third-order excitation is also present in the tip region (P18). The results indicate that the first-order excitation is dominant at the suction-side leading edge of the long blade.

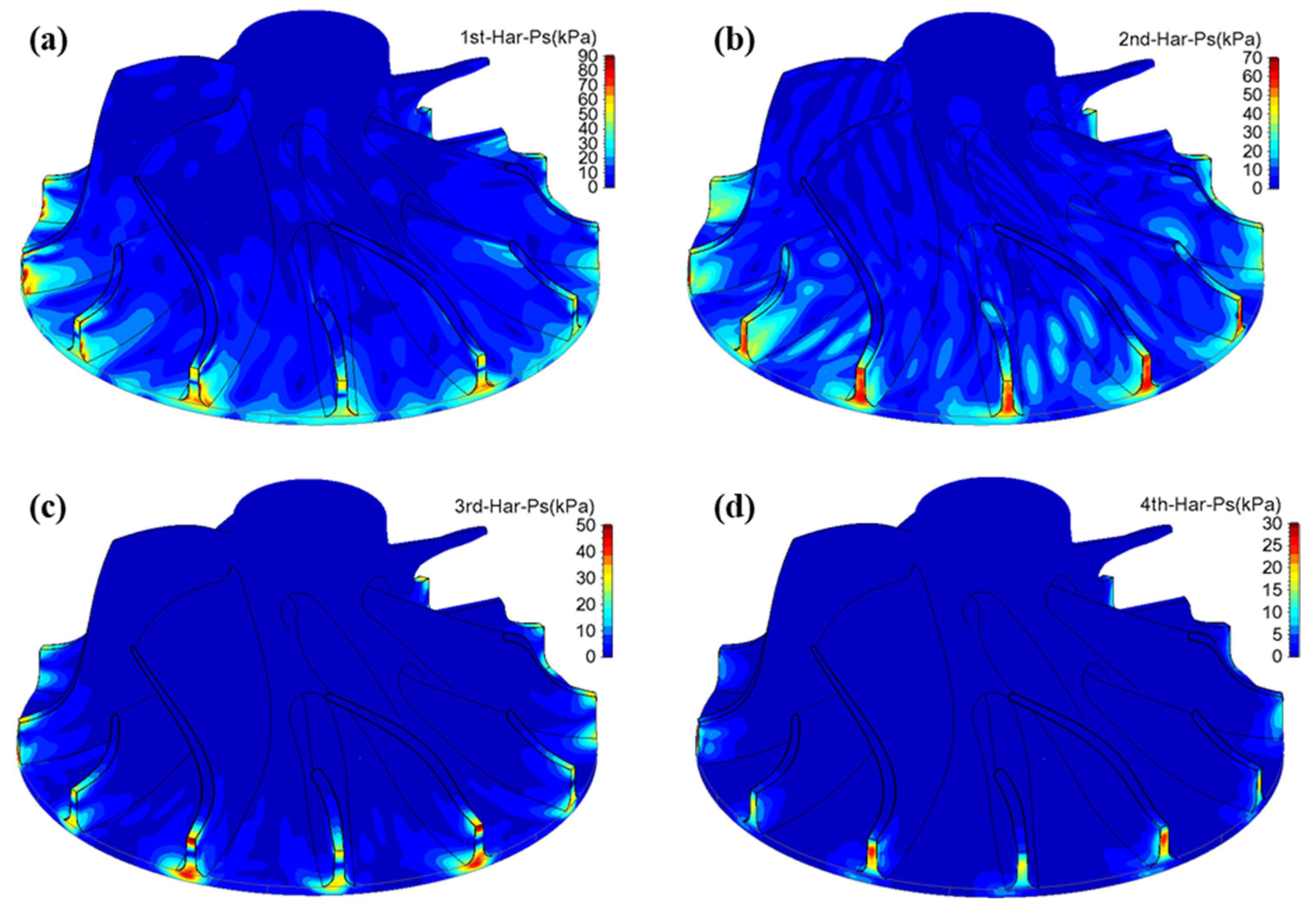

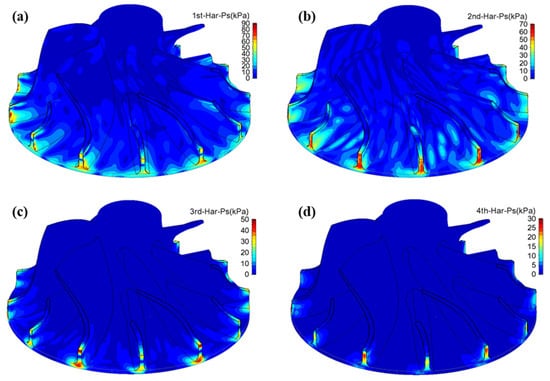

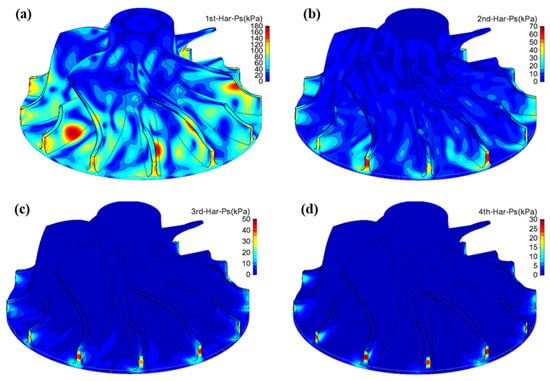

4.3. Airflow Excitation Characteristics

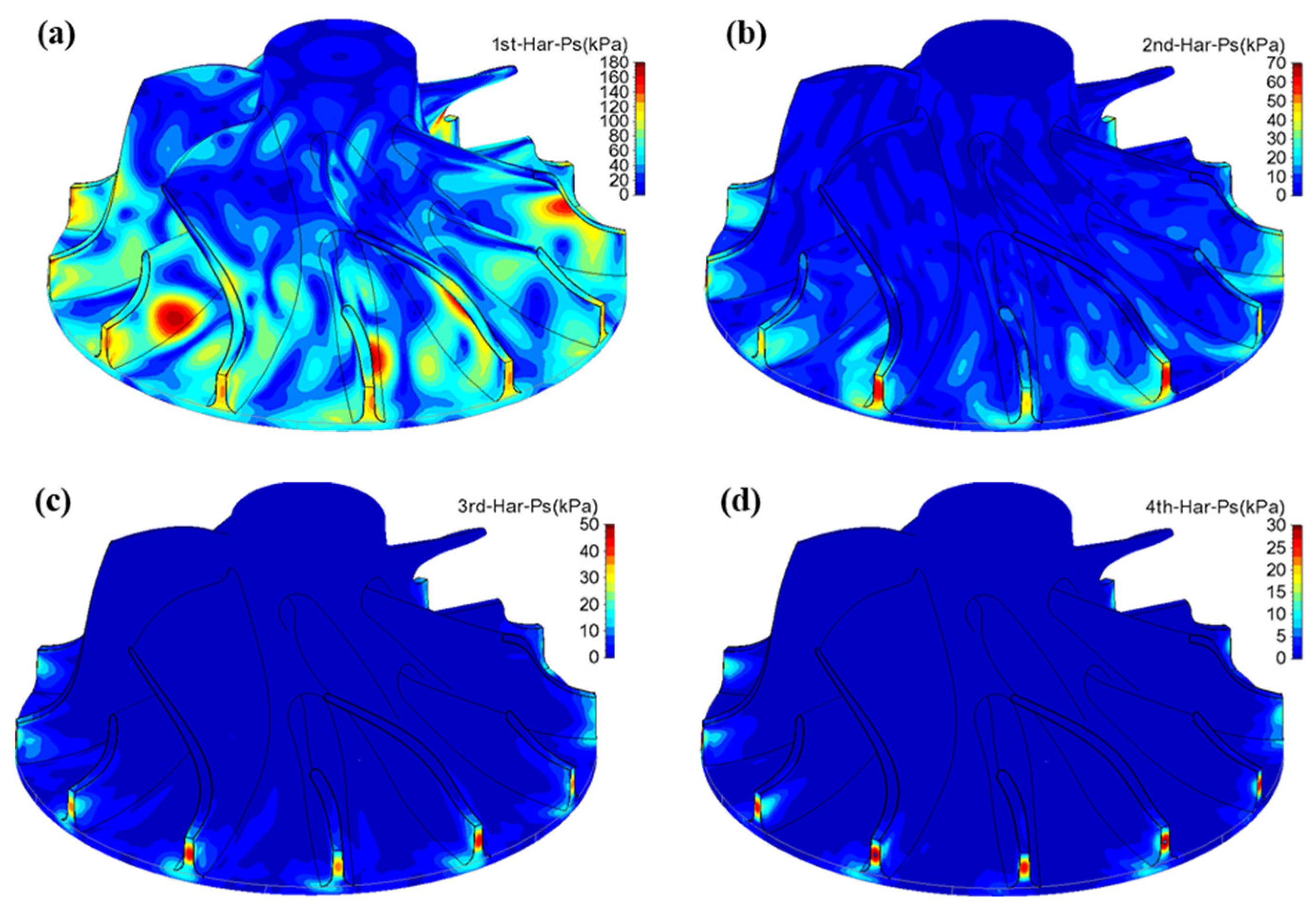

Figure 22 illustrates the amplitude distributions of different excitation orders on the impeller. The first- and second-order airflow excitations exhibit higher amplitudes. The regions of high amplitude are concentrated near the blade leading edge and extend into the flow passage. The extension is more pronounced on the suction side than on the pressure side. For the first-order excitation, the high-amplitude region extends further on the pressure side of the long blade, reaching 25% of the chord length. For the second-order excitation, the extension is longer on the pressure side of the short blade, reaching 50% of the chord length. The amplitudes of the third- and fourth-order excitations are relatively low. For the third-order excitation, the high-amplitude region is located near the blade leading edge. Its influence within the passage is significantly reduced, extending only up to 10% of the chord length of the long blade. For the fourth-order excitation, the high-amplitude region is confined to the blade leading edge. The maximum amplitude of the first-order airflow excitation is approximately 90 kPa, located near the mid-span of the suction side at the leading edge of the long blade. The second-order excitation reaches a maximum amplitude of about 70 kPa, occurring near the root and tip regions of the leading edge of the long blade. The third-order excitation still attains a maximum amplitude of around 50 kPa, while the fourth-order excitation drops significantly to approximately 25 kPa.

Figure 22.

Distributions of airflow excitation of different orders on the impeller for the double-row staggered nozzle layout at 90,000 rpm ((a) First-order airflow excitation, (b) Second-order airflow excitation, (c) Third-order airflow excitation, (d) Fourth-order airflow excitation).

It is noteworthy that for the first- and third-order excitations, a low-amplitude region is observed near the mid-span of the blade leading edge. Meanwhile, the second- and fourth-order excitations extend across the entire blade leading edge. The results suggest that the second-order excitation plays a dominant role near the mid-span, which is in agreement with the frequency domain characteristics of the static pressure fluctuations presented in Figure 19.

The results indicate that the first- and second-order airflow excitations are dominant for the impeller, with maximum amplitudes of 90 kPa and 70 kPa, respectively. Considering the Campbell diagram presented in Figure 12, these excitations carry the potential to induce impeller resonance and are critical factors affecting the fatigue life of the rotor.

4.4. Effect of Nozzle Aerodynamic Layout on Excitation

4.4.1. Effect of Nozzle–Impeller Radial Clearance

The effect of the radial clearance between the nozzle and the rotor on airflow excitation was investigated. Three radial clearances were selected: 2.5 mm (baseline), 3.5 mm, and 5.0 mm. Figure 23 compares the amplitudes of airflow excitation at points P1, P3, P16, and P18 under the three radial clearance conditions. As the radial clearance increases from 2.5 mm to 3.5 mm, both the first- and second-order excitations exhibit significant reductions. The maximum reduction in the first-order excitation reaches 55.7% and occurs at the root of the pressure-side leading edge (P1). For the second-order excitation, the maximum reduction is 33.3%, also observed at the tip of the pressure-side leading edge (P3). When the radial clearance is further increased from 3.5 mm to 5.0 mm, the reductions in both the first- and second-order excitations become less pronounced. The maximum reductions in the first- and second-order excitations are 39.2% and 24.2%, respectively, both occurring at the root of the suction-side leading edge (P16). Notably, at the tip of the suction-side leading edge (P18), the first-order excitation exhibits only a slight reduction of 5.2%, indicating relatively stable pressure fluctuations in this region. The comparative analysis demonstrates that the radial clearance between the nozzle and the rotor has a significant influence on airflow excitation. An increase in radial clearance is beneficial for reducing airflow excitation. In the present study, increasing the radial clearance is more effective for attenuating the first-order excitation than the second-order excitation. However, the relationship between radial clearance and excitation attenuation is not linear. As the radial clearance increases, the effectiveness of airflow excitation attenuation gradually decreases. Meanwhile, an increase in radial clearance leads to a noticeable reduction in turbine efficiency.

Figure 23.

Comparison of frequency-domain characteristics of static pressure fluctuations at typical monitoring points for the double-row staggered nozzle layout under different radial clearances at 90,000 rpm.

Figure 24 illustrates the turbine efficiency at different radial clearances. Across the full operating range, an increase in radial clearance leads to a deterioration in turbine efficiency. For the case with an expansion ratio of 7.48 and a rotational speed of 90,000 rpm, increasing the radial clearance from 2.5 mm to 5 mm causes efficiency drops of 1.2% and 0.8%, respectively. Therefore, the use of increased radial clearance to suppress airflow excitation requires a careful consideration of turbine geometric constraints, as well as a trade-off between turbine efficiency and airflow excitation.

Figure 24.

Comparison of turbine efficiency for the double-row staggered nozzle layout under different radial clearances.

4.4.2. Effect of Nozzle Layout

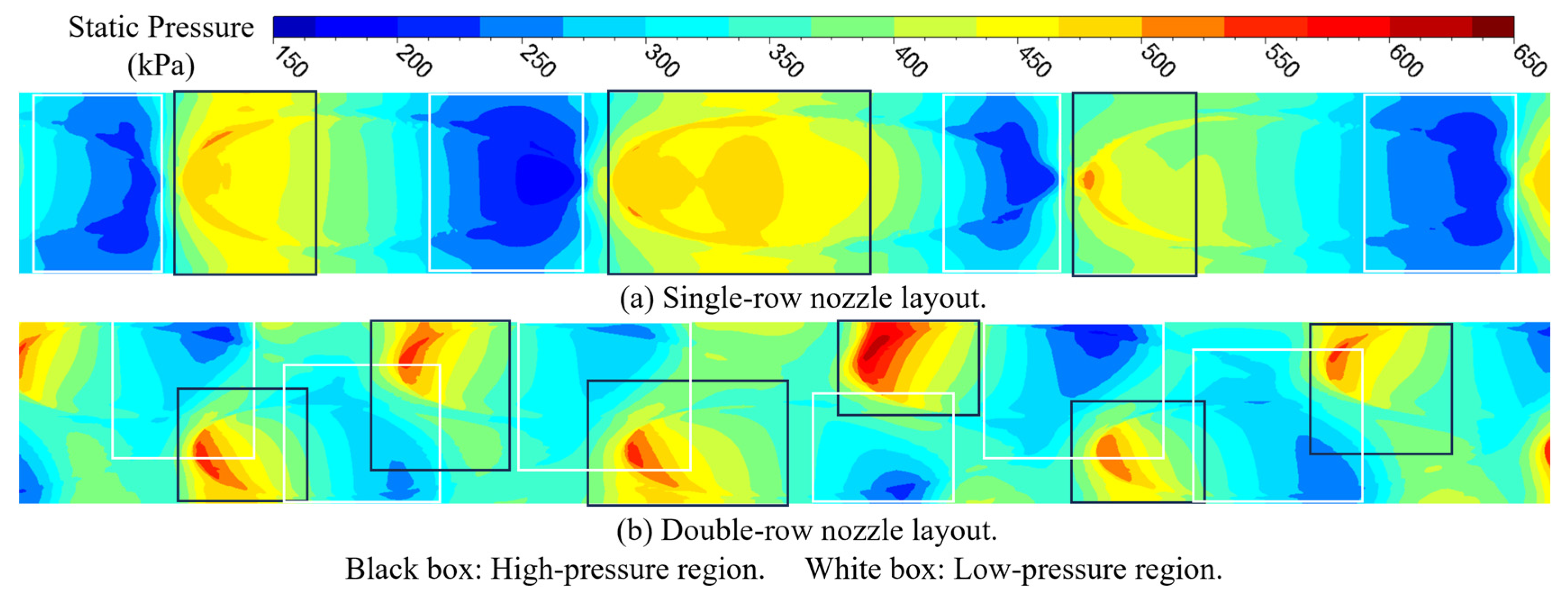

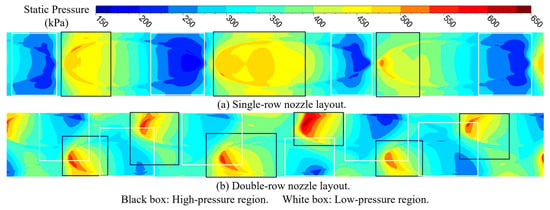

To investigate the influence of nozzle layout on airflow excitation amplitude, a comparative analysis of the internal flow was conducted for turbines equipped with a single-row nozzle and a dual-row staggered nozzle configuration. Due to the limited installation space, more rows of nozzles could not be accommodated within the specified dimensions. Figure 20 shows the distribution of airflow excitation amplitudes for different orders in the impeller under the single-row tubular nozzle layout. Compared with the dual-row staggered nozzle structure, as shown in Figure 18, the first-order airflow excitation amplitude under the single-row nozzle layout increases significantly, with the peak amplitude rising from 90 kPa to 180 kPa. The location of the maximum amplitude shifts from the mid-region of the suction side on the long blade leading edge to the mid-chord region of the suction side on the short blade. Moreover, the region of static pressure fluctuation expands considerably within the flow passage, with an amplitude of 60 kPa observed near the blade trailing edge. In contrast, the amplitudes and distributions of the second-order to fourth-order airflow excitations show little variation. The comparative results demonstrate that the first-order airflow excitation amplitude under the single-row tubular nozzle layout is remarkably higher than the dual-row tubular nozzle layout, and its distribution range is significantly broader. This indicates that the single-row tubular nozzle layout is less effective in suppressing airflow excitation.

The effect of nozzle layout on airflow excitation was investigated. The distributions of airflow excitation on the impeller were compared between the single-row nozzle layout and the double-row staggered nozzle layout. Figure 25 illustrates the distributions of airflow excitation of different orders on the impeller for the single-row nozzle layout at 90,000 rpm. Compared with the double-row staggered nozzle layout shown in Figure 20, the amplitude of the first-order airflow excitation under the single-row nozzle layout increases significantly. An increase in the maximum amplitude of the first-order excitation is observed, rising from 90 kPa to 180 kPa. The spatial location of the maximum amplitude is also found to vary under this condition; specially, it extends further into the flow passage and reaches approximately 50% of the chord length on the suction side of the short blade. In addition, the high-amplitude region expands markedly within the flow passage, and amplitudes of about 60 kPa are observed near the blade trailing edge.

Figure 25.

Distributions of airflow excitation of different orders on the impeller for the single-row nozzle layout at 90,000 rpm. ((a) First-order airflow excitation, (b) Second-order airflow excitation, (c) Third-order airflow excitation, (d) Fourth-order airflow excitation).

The maximum amplitude of the second-order airflow excitation remains nearly unchanged; however, the high-amplitude region near the blade leading edge is slightly reduced. Similarly, the maximum amplitudes of the third- and fourth-order airflow excitations show little variation. Nevertheless, the spatial distribution of the third-order excitation differs between the two nozzle layouts. Under the single-row nozzle configuration, the high-amplitude region of the third-order excitation is mainly located near the mid-span of the blade leading edge. For the double-row staggered nozzle configuration, a different distribution pattern is observed: The high-amplitude region of the third-order excitation shifts toward the root and tip of the blade leading edge. No significant change is observed in the distribution of the fourth-order excitation, while a slight increase in the amplitude of the fourth-order excitation is observed at the leading edge of the short blade. The region of elevated amplitude extends marginally into the flow passage and reaches approximately 10 kPa. In addition, unlike the behavior observed in Figure 20, the high-amplitude regions of the first- and third-order airflow excitations cover the entire blade leading edge and no low-amplitude region is observed near the mid-span. This behavior indicates that, with the single-row nozzle layout, the mid-span region of the blade leading edge is no longer dominated by the second-order airflow excitation. Instead, the first-order airflow excitation becomes the dominant contributor.

Figure 26 compares the instantaneous static pressure distributions at the nozzle outlet at the same instant for different nozzle layouts. For the single-row nozzle layout, alternating high- and low-static-pressure regions are observed circumferentially at the nozzle outlet. During one nozzle passing period, the impeller is subjected sequentially to one high-pressure region and one low-pressure region, as illustrated in Figure 26a. As a result, the aerodynamic loads on the impeller manifest predominantly as the first-order excitation. The situation is different for the double-row staggered nozzle layout; in this layout, one nozzle passing period contains two nozzles, and each nozzle generates its own high- and low-pressure regions. Because the nozzles are staggered circumferentially, the high- and low-pressure regions associated with each nozzle are phase-shifted. After the flow exits the nozzles, axial mixing occurs, causing the high- and low-pressure regions to extend in the axial direction. During one nozzle passing period, the impeller is exposed to a sequence of high- and low-pressure regions. As indicated in Figure 26b, two high-pressure regions and two low-pressure regions are encountered near the mid-span. This flow feature weakens the first-order airflow excitation while enhancing the second-order excitation acting on the impeller. In the airflow excitation distribution, this behavior is reflected by the dominance of first-order excitation under the single-row nozzle layout, where high-amplitude regions extend throughout the entire flow passage. In contrast, under the double-row staggered nozzle layout, the first-order excitation is significantly reduced, and its influence is confined to the impeller leading-edge region. Meanwhile, the area of high-amplitude second-order excitation increases, although its maximum amplitude remains nearly unchanged.

Figure 26.

Comparison of instantaneous static pressure distributions at the nozzle outlet at the same instant for different nozzle layouts at 90,000 rpm.

5. Conclusions

This paper investigates the ultra-high-frequency airflow excitation characteristics induced by rotor–stator interaction in a high-expansion-ratio ECS radial flow turbine. The tubular nozzles utilized in this ECS radial flow turbine have received little attention in the open literature. Based on the FINE/Turbo 14.1 software package, the three-dimensional RANS equations were solved using the NLH method. Resonance and failure causes of the impeller were investigated using harmonic response analysis. Both the CFD numerical method and the impeller resonance predictions were validated experimentally. The effects of three nozzle–impeller radial clearances (2.5 mm, 3.5 mm, and 5 mm) on airflow excitation were discussed and the variations in airflow excitation induced by different nozzle layouts (single-row and double-row staggered nozzles) were studied.

- (1)

- Time domain and frequency domain analyses indicated that rotor–stator interaction is the primary source of strong unsteady excitation within the turbine, with the first-order and second-order airflow excitation being dominant. The excitation sources in the radial flow turbine with tubular nozzles used in this study differ from those in widely studied automotive turbocharger radial flow turbines. In automotive turbocharger radial turbines, the primary sources of aerodynamic excitation are shock waves, tip clearance flow in vaned nozzles, and the volute tongue in vaneless nozzles. In the tubular nozzle design employed in this study, the maximum Mach number reached 1.8 at the nozzle exit, but no shock waves were formed. Therefore, the rotor–stator interaction dominated the airflow excitation experienced by the impeller. The maximum amplitudes of the first-order and second-order airflow excitations reached 90 kPa and 70 kPa, respectively. The airflow excitation mainly impacted the blade leading edge, with larger amplitudes and a wider influence on the suction side compared with the pressure side. Second-order airflow excitation dominated the mid-span region of the blade leading edge, while first-order airflow excitation dominated the tip and root regions.

- (2)

- Increasing the radial clearance between the nozzle and the impeller effectively reduced airflow excitation and enhance impeller safety. However, the effect of increasing the radial clearance on weakening airflow excitation was nonlinear. With increasing radial clearance, the reduction in airflow excitation became less effective. When the radial clearance increased from 2.5 mm to 3.5 mm (a 40% increase), the maximum reduction in first-order airflow excitation reached 55.7%. Increasing the radial clearance further from 3.5 mm to 5 mm (a 42.9% increase) resulted in a maximum reduction of 33.3% in first-order airflow excitation. Moreover, increasing the radial clearance led to a reduction in turbine efficiency. The corresponding reductions in efficiency were 1.2% and 0.8%, respectively. Therefore, when weakening airflow excitation by increasing the radial clearance, it is necessary not only to consider turbine size limitations but also to balance turbine efficiency and airflow excitation.

- (3)

- The nozzle layout had a significant impact on the airflow excitation of the turbine impeller. Compared with the single-row nozzle layout, the airflow excitation was significantly weakened in the double-row staggered nozzle layout. The single-row nozzle layout exhibited pronounced first-order airflow excitation characteristics. The maximum amplitude was 180 kPa, with the high-amplitude regions distributed throughout the entire impeller flow passage. For the double-row staggered nozzle layout, the maximum amplitude of the first-order airflow excitation was only 50% of that observed in the single-row nozzle layout. The high-amplitude regions were confined to the impeller leading-edge area. The amplitudes and distributions of airflow excitations of the other orders showed little difference.

Author Contributions

Y.L.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Investigation, Data Curation, Formal Analysis, Writing—Original Draft. S.J.: Conceptualization, Resources, Supervision, Review and Editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Yan, J.; Yu, J.; Zhuang, W.; Li, L.; Chen, Y. Study on Fault Feature Extraction of ECS Turbine Bearing by Combination of EEMD and HMM. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2022, 2181, 012037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Chen, S.; Sheng, C.; Xie, H.; Luo, G.; Hou, Y. Study on Coupling Performance of Turbo-Cooler in Aircraft Environmental Control System. Energy 2021, 224, 120029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Chen, H.; Wang, Y.; Wei, Y.; Wu, G. An Investigation of the Effects of Volute A/R Distribution on Radial Turbine Performance. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part D J. Automob. Eng. 2024, 238, 3242–3252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiseira, A.; Dolz, V.; Inhestern, L.B.; Echavarría, J.D. Choking Dynamic of Highly Swirled Flow in Variable Nozzle Radial Turbines. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2022, 122, 107396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, H.-J.; Schulz, A.; Schwitzke, M. Aerodynamic Excitation of Blade Vibrations in Radial Turbines. MTZ Worldw. 2013, 74, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Li, Y.; Liu, Z.; Yin, B.; Wang, L. Study on the Influence of Volute Throat Jet on Excitation Vibration Alleviation of Radial Turbine Blade. J. Turbomach. 2025, 147, 11010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Dong, H. A Vibration Frequency Sweeping Algorithm Based on Equivalent Single Degree of Freedom for Turbine. Trans. Beijing Inst. Technol. 2024, 44, 270–277. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, C.; Huang, Z.; Qi, M. Investigation on the Forced Response of a Radial Turbine under Aerodynamic Excitations. J. Therm. Sci. 2016, 25, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galindo, J.; Tiseira, A.; Navarro, R.; Inhestern, L.B.; Echavarría, J.D. Numerical Analysis of the Effects of Grooved Stator Vanes in a Radial Turbine Operating at High Pressure Ratios Reaching Choked Flow. Aerospace 2023, 10, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Yang, M.; Murae, S.; Sato, W.; Shimohara, N.; Yamagata, A. Aerodynamic Interaction of Volute with Rotor in a Nozzleless Radial Turbine. J. Turbomach. 2022, 144, 61012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Yang, M.; Murae, S.; Sato, W.; Shimohara, N.; Yamagata, A. Influence of Tip Clearance Distribution on Blade Vibration of Vaneless Radial Turbine. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part D J. Automob. Eng. 2022, 236, 1007–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Lao, D.; Liu, Y.; Yang, C.; Qi, M.; Ma, C. Harmonic Resonance and High Cycle Fatigue of a Radial Turbine in Pressure Fluctuation. Trans. Beijing Inst. Technol. 2014, 34, 1120–1124. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, D.; Wang, K.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Q.; Lei, X.; Hu, L. An Investigation of the Performance and Internal Flow of Variable Nozzle Turbines with Split Sliding Guide Vanes. Machines 2022, 10, 1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Shi, X.; Sun, H.; Qi, M.; Song, P. Effects of Grooved Vanes on Shock Wave and Forced Response in a Turbocharger Turbine. Int. J. Engine Res. 2021, 22, 805–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwitzke, M.; Schulz, A.; Bauer, H.-J. Prediction of High-Frequency Blade Vibration Amplitudes in a Radial Inflow Turbine with Nozzle Guide Vanes. In Proceedings of the Turbo Expo: Power for Land, Sea, and Air, San Antonio, TX, USA, 3–7 June 2013; American Society of Mechanical Engineers: New York, NY, USA, 2013; Volume 55270, p. V07BT33A007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, A.; LaRue, G. Vibratory Response Characterization of a Radial Turbine Wheel for Automotive Turbocharger Application. In Proceedings of the Turbo Expo: Power for Land, Sea, and Air, Berlin, Germany, 9–13 June 2008; ASME Technical Publishing Office: New York, NY, USA, 2008; Volume 43154, pp. 583–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Yang, M.; Murae, S.; Sato, W.; Kawakubo, T.; Yamagata, A.; Deng, K. Study on Aerodynamic Excitation of Radial Turbine Blades with Vaneless Volute at Low Excitation Order. J. Fluids Struct. 2021, 107, 103408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.