Abstract

Cavitation in aircraft hydraulic systems continues to pose a serious problem for the aviation industry. This paper presents a new study on cavitation in aviation hydraulic fluid AMG-10 at its inception condition, corresponding to a relative pressure drop of Δp = 0.58, within a small-scale rectangular throttle channel of specified dimensions. Numerical simulations were performed in a quasi-steady-state framework using the realizable k–ε turbulence model combined with the Enhanced Wall Treatment approach, and the results were validated against time-integrated experimental data obtained via the shadowgraphy method. Cavitation was modeled using the Zwart–Gerber–Belamri model. The validated numerical model, which showed a pressure deviation of less than 10% from experimental data on the upper and lower walls, also demonstrated good agreement in the dimensions of the cavitation regions, confirming that the upper region is consistently larger than the lower one. Quantitative analysis demonstrated that regions with high vapor concentration are highly localized, representing only 0.048% of the channel volume at a 0.8 vapor fraction threshold. The analysis reveals that the cavitation regions spatially coincide with local pressure drops to values as low as 214 and 236 Pa near the upper and lower walls. These regions are also associated with wall jets, accelerated by the flow constriction to velocities up to 41.98 m/s. Furthermore, the cavitation region corresponds to a distinct peak in the mean turbulent kinetic energy field, reaching 164.5 m2/s2, which decays downstream.

1. Introduction

Hydraulic systems play a crucial role in aircraft flight control, providing the power, precision, and responsiveness required to operate control surface actuators, wing mechanization, landing gear, and other critical components. Cavitation in hydraulic system components remains a persistent challenge, leading to additional hydraulic losses and reduced system efficiency, which in turn adversely affects fuel economy and increases operating costs [1,2,3,4]. Furthermore, the development of cavitation processes in an aircraft’s hydraulic systems can cause component damage and may even degrade the aircraft’s flight-control response [5].

Analysis of recent studies indicates that cavitation remains a significant challenge for aviation. The majority of recent research on cavitation in aircraft hydraulic systems has focused on investigating of the cavitation inside pilot stage valve [6,7], cavitation phenomenon in an electrohydraulic nozzle-flapper valve [8,9], cavitation suppression in aircraft hydraulic nozzle-flapper valve using triangular nozzle exits [10], and the effects of flow force and forced vibration [11,12], cavitation evolution mechanism and periodic flow of aviation pressure poppet valve [13], cavitation inside the jet servo valve [14,15,16,17,18], vortex cavitation morphological characteristics in u-shape notch spool valve [19], cavitation flow in a hydraulic slide valve [20,21] cavitation on continuous-type pintle injectors [22], parametric optimization of surface textures in aircraft valves [23]. Cavitation remains a significant issue in the operation of aviation piston pumps [24,25] and other equipment [26].

Recent studies on cavitation in hydraulic fluids encompass experimental investigations of jet cavitation erosion [27,28], oxidative deterioration effect of cavitation heat generation [29], cavitation erosion characteristics of high bulk modulus hydraulic oils [30], effect of oil viscosity on hydraulic cavitation luminescence [31], influence of air dissolved in hydraulic oil on cavitation erosion [32], occurrence characteristics of gaseous cavitation in oil shear flow [33], experiments and computational fluid dynamics on vapor and gas cavitation for oil hydraulics [34], experimental study of multiphase flow occurrence caused by cavitation during mineral oil flow [35].

A review of the literature reveals a wide range of issues related to the onset and development of cavitation in aircraft hydraulic systems, arising from the design and operating principles of hydraulic components under specified system pressures, as well as from the physical properties of the hydraulic fluid. In this context, the selection of an appropriate hydraulic fluid has a significant impact on the efficiency and reliability of system performance. Aviation mineral oil AMG-10 (derived from hydrocracking products of a paraffinic crude mixture and composed mainly of naphthenic and isoparaffinic hydrocarbons) has not been addressed in previous studies; however, it is widely used in aviation technology due to its stable viscosity, anti-corrosion and anti-friction properties, and low foaming tendency. It also contains antioxidant additives and a dye. Close analogs of the aviation hydraulic fluid AMG-10 include Hydraunycoil FH-51, with the primary difference lying in the degree of refinement.

To conclude the literature review, it should be emphasized that cavitation continues to pose a serious issue in aircraft hydraulic drive systems. Despite extensive research on cavitation in hydraulic fluids, cavitation in AMG-10 oil remains insufficiently explored. Particularly relevant is the investigation of this process under significant pressure drops (equivalent to those occurring in the hydraulic system of an actual aircraft) and within small clearances in hydraulic units, which may arise during the operation of most hydraulic system components. The present study investigates cavitation inception in AMG-10 hydraulic oil, providing a detailed analysis of the flow characteristics and fluid behavior under conditions representative of aircraft hydraulic systems. For this purpose, numerical modeling is employed and validated against experimental data obtained using the shadowgraphy method.

2. Experimental Setup and Method

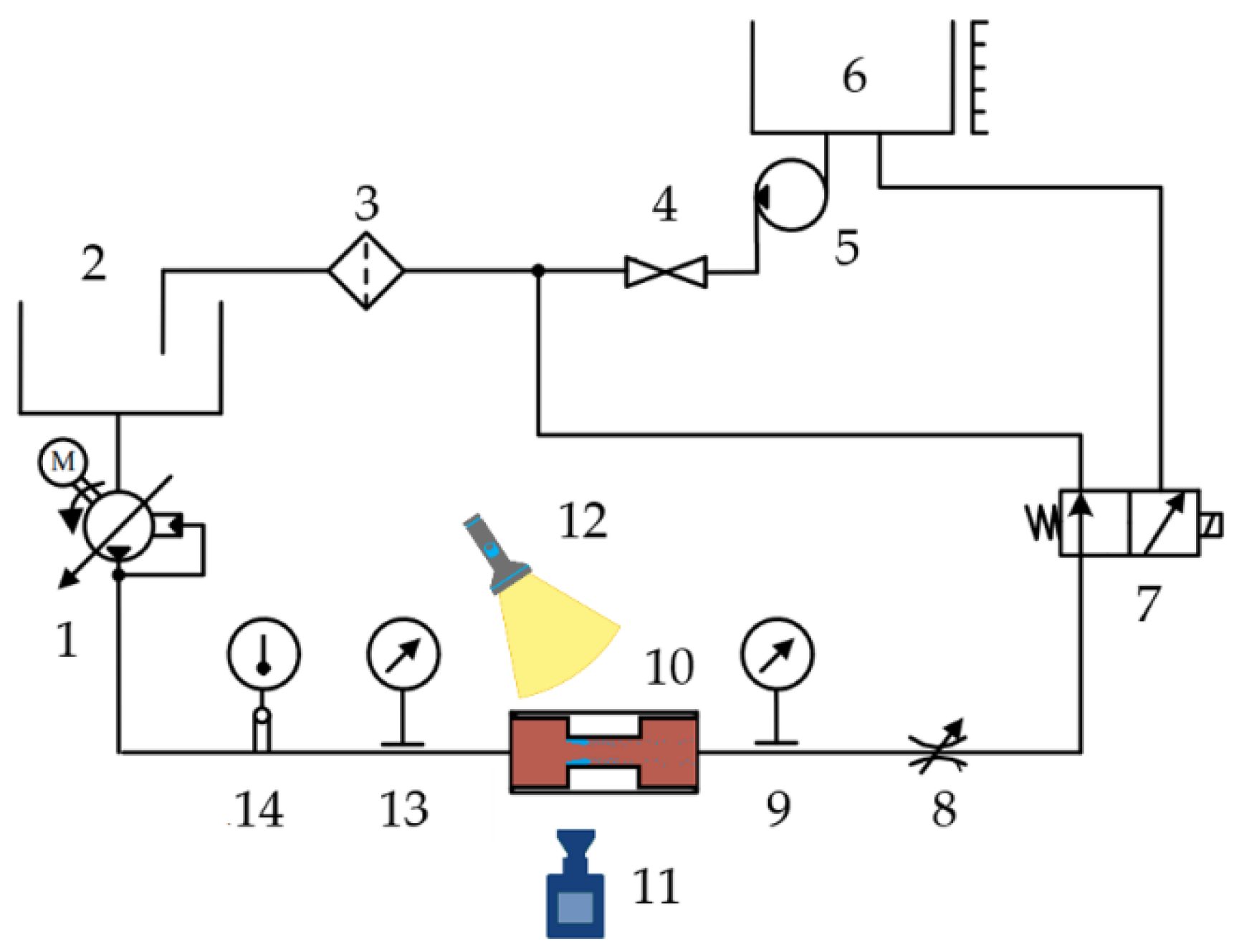

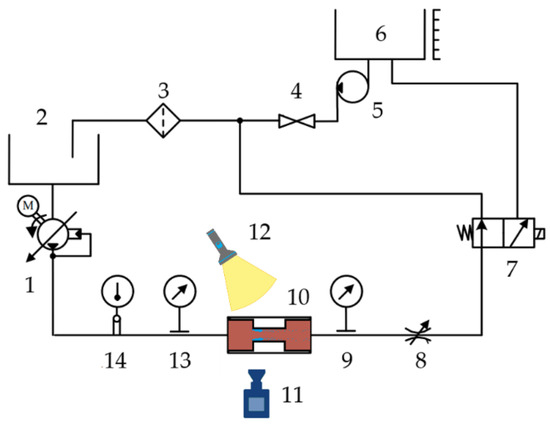

An experimental study was conducted using a test rig (all devices, instruments, and materials of which were provided by the State University “Kyiv Aviation Institute” in Kyiv, Ukraine), a simplified schematic of which is shown in Figure 1. In the pressure line, the flow was supplied by an aviation piston-rotary hydraulic pump, model NP43M-1 (1). The spring tension of the pump regulator determined the fluid pressure at the inlet of the test channel (10), while the pressure at the outlet of the channel was controlled using a throttle valve (8). The pressures at the inlet and outlet of the channel were monitored using manometers (13) (measurement range 0–1.6 MPa, CL 0.6) and (9) (measurement range 0–0.6 MPa, CL 0.6), respectively. The fluid temperature was measured with thermometer (14) (scale division 0.1 °C, measurement error ±0.1 °C). The flow rate of the hydraulic fluid was determined using the measuring tank (6). An electromagnetic valve (7) was used to direct the fluid flow into the measuring tank (6).

Figure 1.

Hydraulic scheme of the experimental rig.

The transfer of hydraulic fluid from the measuring tank (6) to the supply tank (2) was carried out by a booster centrifugal pump (5), model 463. Valve (4) was used to prevent leakage of hydraulic fluid from the measuring tank (6) through pump (5) into tank (2). Filter (3) provided purification of the hydraulic fluid.

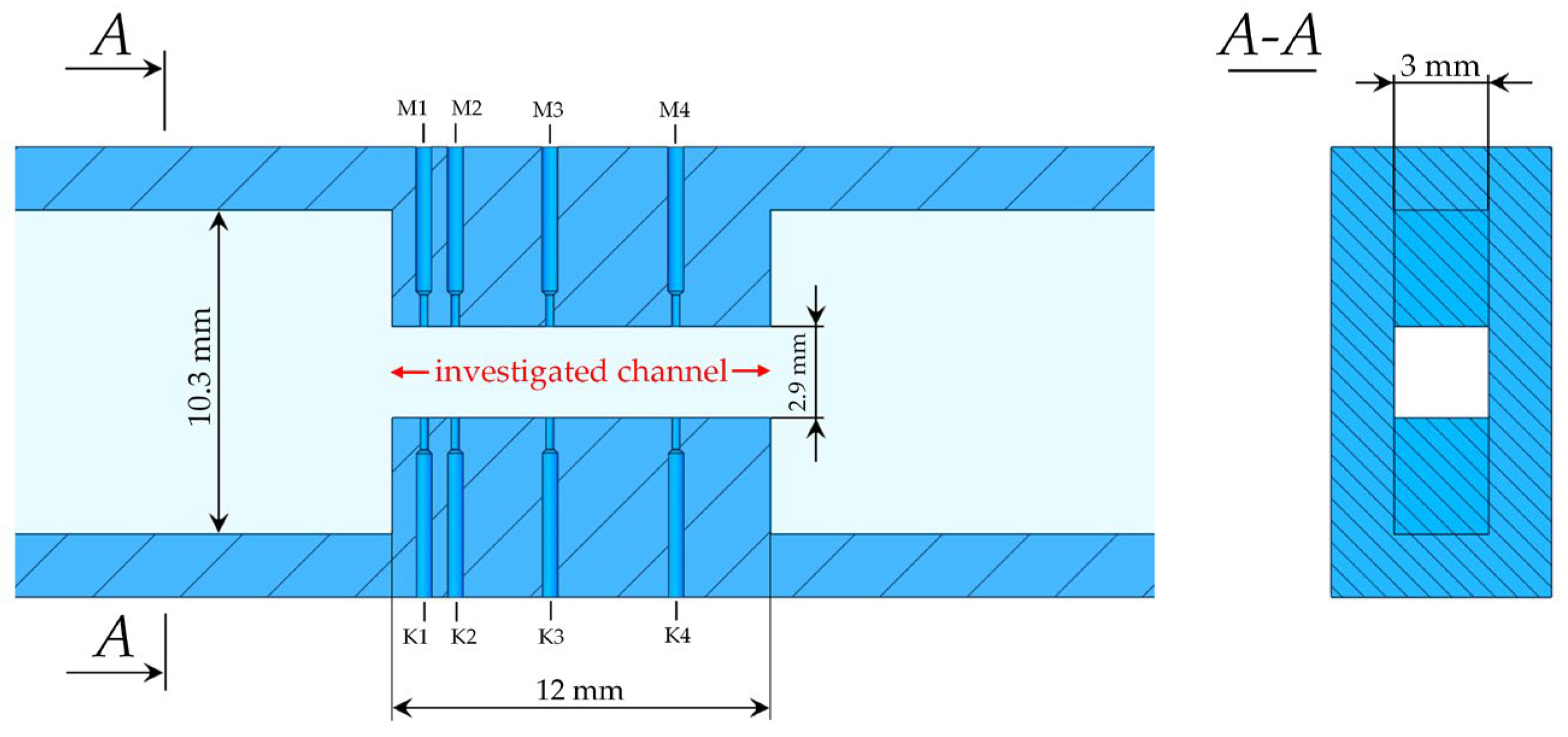

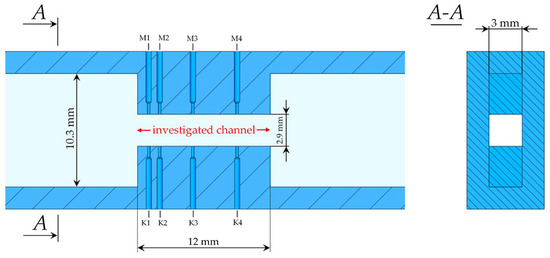

For flow visualization, a test channel (10) made of acrylic glass was used. Its main dimensions are shown in Figure 2. Illumination of the hydraulic oil flow through the channel was carried out using a strobe lamp (12) with pulsed operation and uniform light distribution. The flow was recorded using a high-speed camera (11), model SFR-2M. A single image was captured with an exposure time of 2 × 10−3 s. This exposure time is longer than the characteristic timescale of cavitation cavity oscillations, thus capturing only a time-integrated, blurred outline of the cavitation region. The camera resolution was 1024 × 768 pixels. The spatial scale was calibrated using a reference object, yielding a resolution of 0.0122 mm/pixel. Static pressure was measured at both the upper and lower walls of the investigated channel using two symmetric sets of manometers (measurement range 0–0.6 MPa, CL 0.6). Manometers M1, M2, M3, and M4 were installed on the upper wall, while manometers K1, K2, K3, and K4 were installed on the lower wall. Both sets were positioned at corresponding distances of 1 mm, 2 mm, 5 mm, and 9 mm from the channel inlet. In the following, the term “investigated channel” refers to the section between the inlet contraction and the outlet expansion of the throttle, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Channel geometry: longitudinal section and cross-section A-A.

Within the experiment, the relative pressure drop was defined as:

where Pinlet is the absolute pressure at the channel inlet, a Poutlet is the absolute pressure at the channel outlet.

Table 1 presents the main parameters of the experiment.

Table 1.

Main parameters of the experiment.

In the numerical simulation, the same parameters as in the experiment were used.

3. Numerical Simulation of Cavitation Process

3.1. Description of Governing Equations

For the numerical simulation of cavitation, a quasi-steady-state homogeneous mixture model was employed, treating AMG-10 hydraulic oil as the primary liquid phase and oil vapor as the secondary phase. Although cavitation in practical systems often involves the release of a small amount of previously dissolved air [32,35,36], this component was neglected in the present model. This simplification is justified by the experimental conditions: to limit the influence of non-condensable gas, the investigations were conducted using pre-degassed AMG-10 oil. Accordingly, the numerical model focuses solely on the liquid-vapor phase change, consistent with the prepared state of the fluid in the experiments.

The homogeneous mixture model (liquid-gas) provides a simplified representation of a two-phase flow, offering relatively low computational complexity. In this model, the consideration of the volume fraction makes it possible to describe the two-phase fluid as a single medium with coexisting phases, thus allowing it to be treated as a single-phase model. For the liquid-gas mixture under consideration, the continuity equation in the quasi-steady-state formulation is given as follows:

where ρm is the density of the mixture; u is the average mixture velocity. At the same time, the mixture density is defined as:

where αv is the vapor phase volume fraction; ρl, ρv are the density of liquid and vapor phases, respectively.

The momentum equation of mixture can be described by the following expression:

where p is the absolute pressure of the mixture; g is the acceleration due to gravity; μm is the viscosity of mixture and μt is the turbulent viscosity.

The Realizable k–ε model is suitable for quasi-steady-state cavitation simulations due to its robustness and relatively low computational cost. Unlike the standard k–ε model, it better predicts low-pressure and recirculation zones associated with cavitation, and more accurately describes near-wall flows when combined with the Enhanced Wall Treatment method, which is a near-wall modeling approach that blends linear (laminar) and logarithmic (turbulent) laws of the wall using a joining function.

Although the quasi-steady-state approach neglects the dynamics of cavitation phenomena, the Realizable k–ε model [37] effectively determines the time-averaged boundaries of cavitation zones. As a result, the model is widely used in engineering calculations of nozzles [38,39], valves [7,40,41], pumps [42,43], and other hydraulic system components [44,45], where the formation of stable cavitation structures is possible.

The turbulent kinetic energy (k) equation takes the following form:

and dissipation rate (ϵ):

where Gk = μtS2 is the production of turbulence kinetic energy, and S is the mean rate-of-strain tensor; other modeling constants C2 = 1.9, σk = 1.0 (the turbulent Prandtl number for k), σϵ = 1.2 (the turbulent Prandtl number for ε). C1 is calculated as follows:

The mixture viscosity and turbulent viscosity of the mixture, respectively, are given by the following equations:

and

where μl, μv are the viscosities of the liquid and vapor phases. For the considered Realizable k–ε turbulence model, the variable Cμ is calculated using the following formula:

where

and Ωij is the mean rate-of-rotation tensor.

In this study, the Zwart–Gerber–Belamri (ZGB) cavitation model [46,47] was used to describe the cavitation process. The model is characterized by simplicity, robustness, and versatility, providing reliable simulation of cavitation processes across a wide range of engineering applications, particularly for cavitation in hydraulic systems. It is noted that the ZGB formulation is semi-empirical, and its model coefficients are not uniquely determined by fundamental physical laws. This model is based on the Rayleigh–Plesset equation, which governs the behavior of a vapor bubble in a liquid. The ZGB model assumes that all bubbles have the same size and accounts for evaporation and condensation processes through the mass transfer source term R = Revap − Rcond in the continuity equations for a multicomponent medium.

The model defines the vapor volume fraction using the following equation:

where RB represents the bubble radius, n is the bubble concentration per unit volume of the mixture. Equation (18) establishes the relationship between the vapor volume fraction and the bubble concentration per unit volume, which makes it possible to model cavitation as a homogeneous mixture of liquid and vapor bubbles of a given radius.

The transport equation for the vapor fraction is represented by the equation below:

where phase transfer rate terms Revap is the evaporation rate and Rcond is the condensation rate, are formulated as follows:

- evaporation ( ≤ psat) isand condensation ( > psat) iswhere psat is the saturation vapor pressure; p∞ is the local absolute static pressure in the flow field; rnuc is the volume fraction at the bubble nucleation site with a value of 3 × 10−4, and other constants are Cevap = 35, Ccond = 0.0012, RB = 1.2 × 10−6.

The ZGB coefficients were treated as effective model parameters and adjusted for AMG-10 hydraulic oil based on macroscopic, time-integrated experimental observables. The calibration was guided by explicitly defined physical criteria, including agreement between computed and measured pressure levels at the monitoring locations M1–M4 and K1–K4, the observed cavitation inception location, and the mean cavity extent obtained from time-integrated flow visualizations. The adjustment was performed within physically reasonable bounds to ensure consistent reproduction of these macroscopic features. The resulting coefficient set should therefore be regarded as an effective calibration valid for the present flow configuration and working fluid only.

To account for the influence of turbulent fluctuations on cavitation, the corrected saturation pressure of the oil was used [48]:

3.2. Mesh Configuration and Numerical Methods

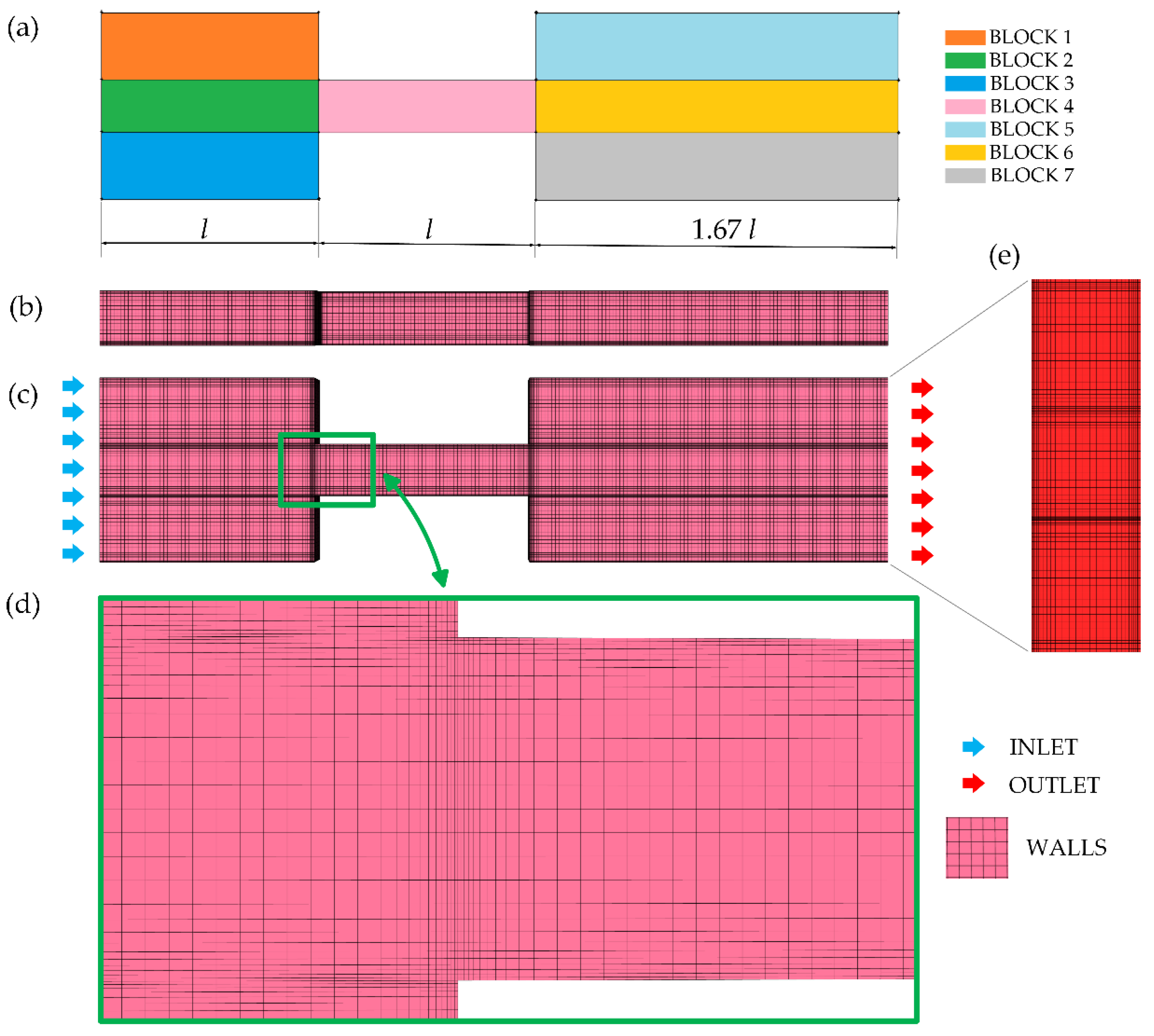

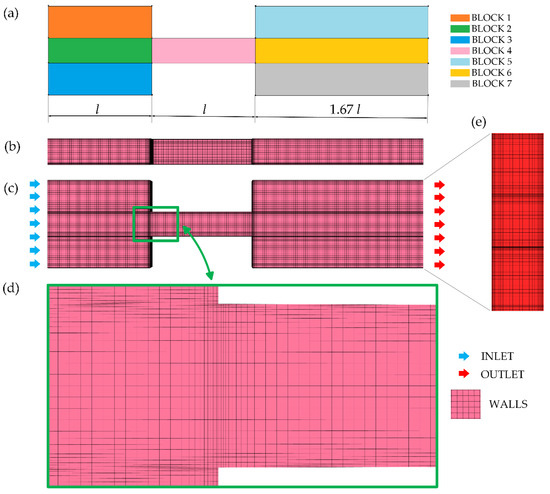

For the numerical investigation of cavitation, a three-dimensional model of the flow channel was developed, based on the geometric dimensions of the experimental test channel (10), as shown in Figure 2. The computational domain encompassed the full geometry of the throttle, including the inlet contraction, the investigated channel, and the outlet expansion. Unlike the test channel, in the three-dimensional model (Figure 3a), the inlet part has a length of l, while the outlet part is 1.67l, where l is the length of the investigated channel. The length of the inlet part was exactly the same as in the experimental setup. The outlet part was extended to a length sufficient to eliminate reverse flow, ensuring solver convergence and boundary-condition independence of the solution in the region of interest, while maintaining a reasonable mesh size.

Figure 3.

Computational mesh of the investigated channel: (a) block structure view; (b) top view; (c) front view; (d) detailed view of the front mesh near the wall; (e) side view with a detail of the outlet region.

Prior to generating the computational mesh, the model was divided into blocks, as shown in Figure 3a. The computational domain was discretized using a block-structured mesh (Figure 3b–e), ensuring smooth transitions between regions with different levels of detail, uniform element distribution, and numerical stability. To minimize numerical diffusion and enhance solution accuracy, a mesh predominantly composed of hexahedral cells was employed.

Initially, a mesh sensitivity study was conducted to determine the optimal computational resolution. Five meshes with cell sizes ranging from 0.1 mm to 0.3 mm were evaluated. The analysis focused on key local parameters: the minimum wall pressure Pmin and the cavity thickness Tcav at the upper and lower walls, as well as the global volume fraction of vapor (see Table 2, where Δ is relative change compared to the previous mesh).

Table 2.

Mesh sensitivity study.

The results demonstrate that mesh independence is achieved for cell sizes of 0.2 mm and finer. Within the 0.1–0.2 mm range, the primary local cavitation characteristics (Pmin, Tcav) vary by less than 4%, indicating that the solution in the cavitation zone is insensitive to further mesh refinement. In contrast, the coarser meshes (0.25 mm and 0.3 mm) were found to inadequately resolve the cavitation physics.

Consequently, the mesh with a cell size of 0.2 mm was selected for all subsequent simulations. The selected mesh consisted of 524,320 cells, providing sufficient resolution for an accurate representation of the flow field.

The mesh was refined near the channel walls, in the region where cavitation was expected (Figure 3d), to more accurately capture velocity and pressure gradients, turbulent effects, and the steep gradients associated with the two-phase flow structure. For the refinement, a boundary layer with 10 layers was used, where the first cell size was 0.02 mm and the growth factor was 1.2. The minimum orthogonal quality was 0.996, indicating high element orthogonality and overall good mesh quality.

3.3. Numerical Methods

The cavitation was simulated using a quasi-steady-state approximation. This approach, which filters out rapid transient bubble dynamics, was chosen to obtain time-smoothed solutions that align with the time-integrated nature of the experimental visualization data. The simulations were conducted using the open-source CFD package OpenFOAM® v2112, with the working medium modeled as an incompressible, isothermal, and turbulent fluid.

Given the absence of a dedicated steady-state solver in OpenFOAM for this physics, the transient solver cavitatingFoam was employed to obtain pseudo-steady-state solutions. This was achieved by configuring its PIMPLE algorithm for strong pressure–velocity coupling within each large computational time step and advancing the calculation with multiple internal iterations until the cavitation field converged. The liquid-phase flow was calculated using the Finite Volume Method (FVM) with the corresponding boundary conditions shown in Figure 3c. For the spatial discretization of derivatives, various numerical schemes were employed to ensure a balance between solution accuracy and stability. The evaluation of variable gradients was carried out using the least-squares method. For pressure, the Gauss linear scheme was applied to approximate gradients and divergence. This scheme uses Gauss integration over the control volume with linear interpolation of values between cell centers, making it suitable for problems with significant gradients. The momentum components and the phase volume fraction were interpolated using the linearUpwind numerical scheme for the discretization of convective terms in the transport equations, providing enhanced accuracy for convection-dominated terms. Such an approximation improves the representation of convective transport compared to first-order schemes while maintaining numerical stability. For the variables describing the turbulent characteristics of the flow (turbulent kinetic energy and turbulent dissipation rate), the linearUpwind scheme was also applied. The applied spatial discretization schemes are second-order accurate. For temporal discretization, a first-order implicit Euler scheme was used, which is adequate for obtaining the pseudo-steady-state solutions. The convergence of the numerical solution was ensured by achieving residual values below 1 × 10−5 for the mass balance in the system, velocity, and pressure, below 1 × 10−4 for turbulence parameters, and below 1 × 10−2 for the volume fraction of phases.

Consequently, all flow characteristics presented and discussed in the following sections are interpreted strictly as time-averaged mixture quantities and are not intended to represent instantaneous cavitation dynamics.

4. Results and Discussion

During the experiment, visual observations of the fluid flow in the investigated rectangular throttle channel allowed tracking changes in the structure of the cavitating flow. In the pressure drop range of 0 < Δp < 0.31, with an inlet absolute pressure of 1.06 MPa, the flow appeared transparent and showed no visible changes. With a further increase in the pressure drop, flow streamlines at the inlet of the investigated channel (at the location of the sudden contraction) began to distort, and stagnant flow regions appeared. The onset of flow separation and cavitation occurs at a pressure drop of approximately Δp = 0.58, which is the focus of the present study [49].

4.1. Wall Pressure Validation

Experimental and simulated absolute pressures for Δp = 0.58 were compared at several points along the channel walls, corresponding to manometer positions M1–M4 (upper wall) and K1–K4 (lower wall). The data are provided in Table 3, and the manometer layout is illustrated in Figure 2. The estimated conservative uncertainty of the experimental data is around ±6000 Pa (sum of the instrumental error ± 3600 Pa and the reading error ± 2500 Pa).

Table 3.

Comparison of experimental and simulated pressures along the upper and lower walls.

As can be seen from Table 3, the numerical simulation results show good agreement with the experimental data. The absolute error varies from 9000 to 48,000 Pa, corresponding to a relative error ranging from 3.27% to 9.77%. The closest agreement is observed downstream of the cavitation region at a distance of 9 mm from the channel inlet (points M4 and K4), where the relative errors are 3.27% and 4.04%, respectively. The least accurate agreement between the numerical and experimental data is observed within the cavitation region, at a distance of 2 mm from the inlet (points M2 and K2). In this region, the relative error reaches 9.77% and 9.51%, which remains within the acceptable range typically associated with numerical simulations of such flows.

At points located 1 mm from the channel inlet (M1, K1), within the potential region of cavitation, the numerical model slightly overestimates the pressure, but the relative error remains below 6.5%. Similarly, at points 5 mm from the inlet (M3, K3), the discrepancy stays within an acceptable margin, not exceeding 9.23% and 8.40%, respectively.

Thus, it can be concluded that the model reliably reproduces the pressure distribution along the upper and lower walls of the channel. Considering the acceptable discrepancy between the numerical and experimental data, the numerical model can be regarded as verified with respect to pressure. This approach enables further flow analysis, including comparison of the predicted time-averaged cavity geometry with experimental data, as well as determination of the mean pressure distribution, velocity fields, and turbulent kinetic energy within the channel.

4.2. Cavity Shape Validation

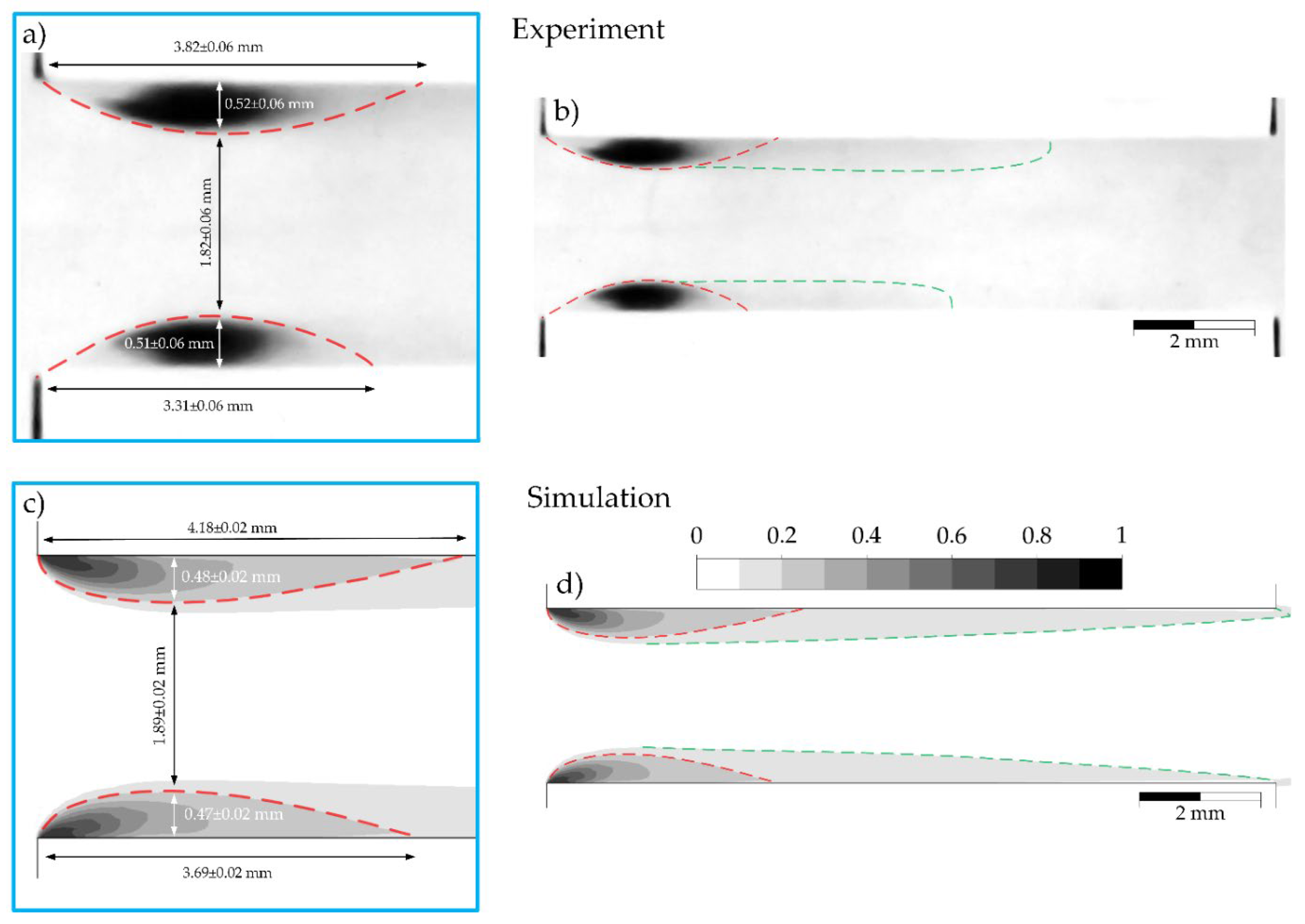

Since the numerical model’s predictions of wall pressure distribution align well with experimental measurements, its validity for further analysis is supported. The model can therefore be checked against the experimental data for its ability to capture the spatial distribution of the vapor phase. Specifically, visualizing the vapor volume fraction along the channel’s longitudinal section allows the simulated cavitation region’s shape and extent to be compared with the experiment, showing a qualitative match with the time-integrated experimental image.

For visual comparison with the time-integrated experimental image, longitudinal sections from the numerical simulation are presented, displaying the vapor volume fraction using a 10-level color scale. This choice of discretization yields a clear visual correspondence with the experimentally observed outline of the cavitating region. Increasing the number of color levels in the visualization leads to a more fragmented appearance of the contour plot, which diverges from the smoother experimental image. This, however, is purely an artifact of the graphical representation; the underlying simulation data defining the existence and spatial extent of the vapor-rich zone remain unchanged.

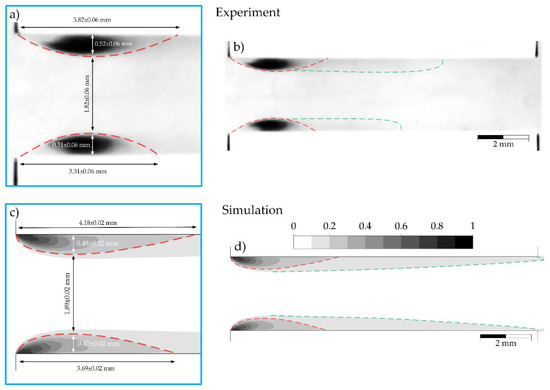

In Figure 4, the boundaries of the cavitation region are shown with red dashed lines, while the downstream zone of high vapor fraction is indicated with green dashed lines. Figure 4 presents a comparison of cavitation structure obtained from experimental observations (Figure 4a,b) and numerical simulations (Figure 4c,d). Figure 4a,c show the cavitating region located near the investigated channel inlet, whereas Figure 4b,d display the distribution of vapor along the entire length of the investigated channel.

Figure 4.

Comparison of cavitation patterns in the longitudinal section: comparison between experiment (a,b) and simulation (c,d).

Linear dimensions of the cavitating region were measured from experimental and numerical images in ImageJ 1.53e using a unified spatial scale calibrated from the experimental image (0.0122 mm/pixel). The uncertainty in locating the cavity boundary, however, differs between the numerical simulation and the experiment. In the numerical results, the boundary is algorithmically sharp. The measurement error in ImageJ is minimal, arising mainly from raster discretization, and is estimated at ±2 pixels (≈±0.02 mm). For the experimental image, the boundary localization error is larger. It results not only from discretization but also from physical interface blurring, optical noise, and the inherent limitations of edge-detection algorithms on real data.

In the experiment, the maximum height of the upper cavity was 0.52 ± 0.06 mm with a cavity length of 3.82 ± 0.06 mm, while the maximum height of the lower cavity was 0.51 ± 0.06 mm with a cavity length of 3.31 ± 0.06 mm. In the numerical simulation, these parameters for the upper cavity were 0.48 ± 0.02 mm and 4.18 ± 0.02 mm, respectively, while for the lower cavity, they were 0.47 ± 0.02 mm and 3.69 ± 0.02 mm, indicating good quantitative agreement with the experimental data. The distance of 1.82 ± 0.06 mm in the experiment and 1.89 ± 0.02 mm in the simulation corresponds to the inter-cavitation gap, i.e., the vertical distance between the upper and lower boundaries of the two symmetric cavitation regions in the flow contraction zone.

The spatial structure of the cavities including its shape and expansion region, is well reproduced in the numerical model. Both experimental and computational results are in agreement, showing a clear asymmetry: the upper cavity is consistently longer than the lower one. The origin of this asymmetry has not been established in the present work and remains outside the scope of this analysis.

The green dashed lines in Figure 4b,d delineate a downstream region characterized by an intermediate vapor volume fraction in the range of 0.1–0.2. In the context of the time-averaged data, this region corresponds to the area of sustained, dispersed vapor presence. The numerical simulation resolves this zone more distinctly, showing a greater elongation along the channel, whereas it appears less pronounced in the experimental images. This difference may arise from limitations in visualizing fine bubbles in the experiment, as well as from the inherent simplifications of the quasi-steady numerical approach in describing complex two-phase flow dynamics. Nevertheless, the consistent spatial localization of this vapor-rich region in both datasets validates the model’s ability to predict the mean structure and extent of the flow transition region downstream of the primary cavitation area.

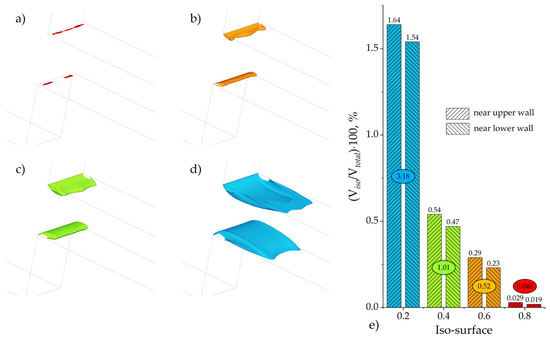

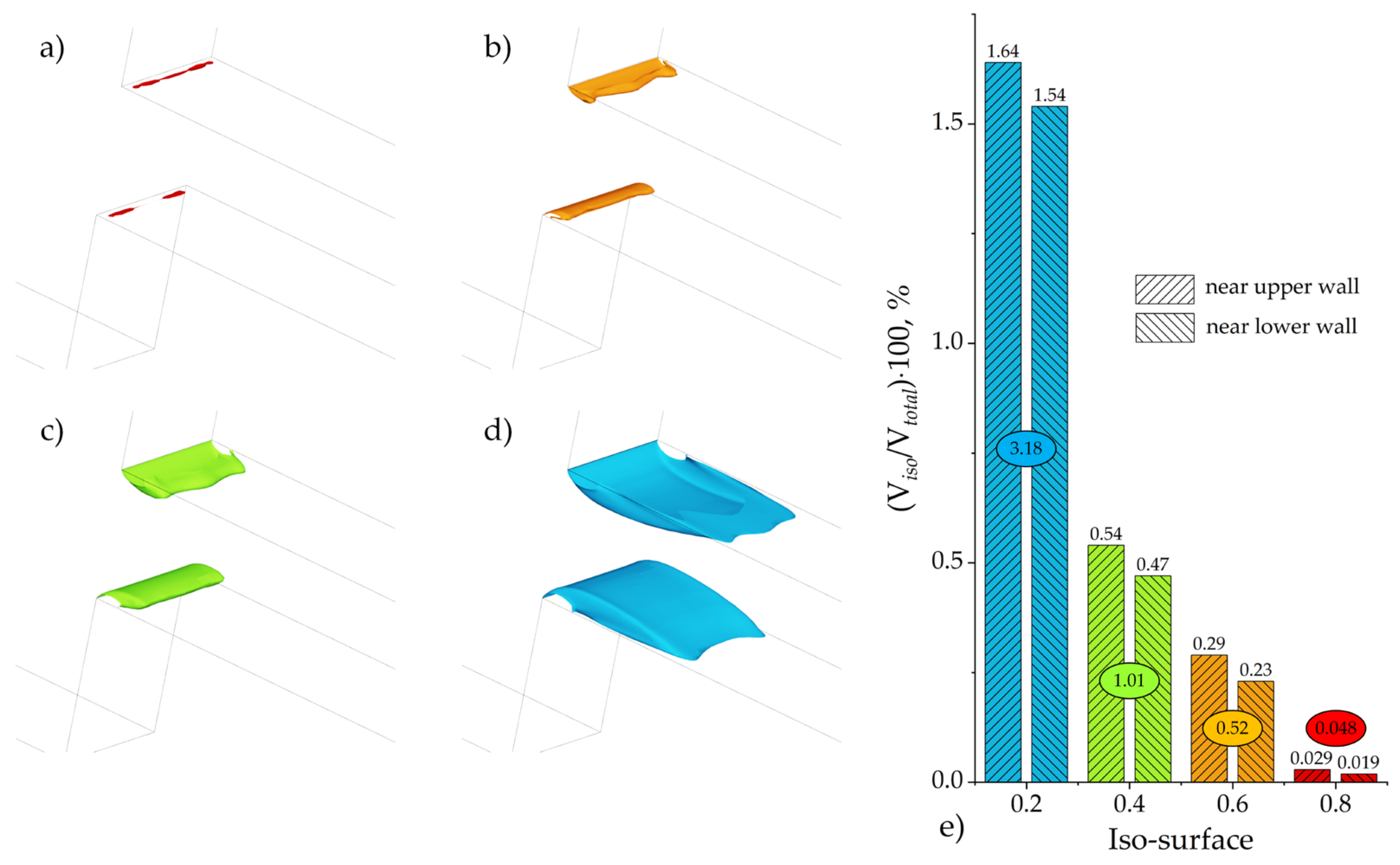

Figure 5a–d show isosurfaces of the vapor volume fraction for different threshold values, obtained from numerical simulations. Each isosurface encloses a volume where the vapor volume fraction exceeds a specified threshold, allowing a parametric analysis of the vapor distribution in the flow and the spatial extent of the cavitating region at different levels of vapor saturation. Such visualization illustrates how the apparent three-dimensional morphology of the cavitating region depends on the chosen threshold, which is crucial for assessing the sensitivity and structural representation of cavitation in the steady-state simulation framework.

Figure 5.

Isosurfaces of the vapor phase volume fraction at different threshold levels (a) 0.8, (b) 0.6, (c) 0.4, (d) 0.2, and (e) bar chart of the vapor phase volume fraction and the relative volume for the individual cavities near the upper and lower walls, with their combined total highlighted by an oval.

Figure 5.

Isosurfaces of the vapor phase volume fraction at different threshold levels (a) 0.8, (b) 0.6, (c) 0.4, (d) 0.2, and (e) bar chart of the vapor phase volume fraction and the relative volume for the individual cavities near the upper and lower walls, with their combined total highlighted by an oval.

The series of isosurface levels, ranging from 0.8 to 0.2, reveals a structure with a dense core and a more diffuse periphery. At the highest thresholds (0.8 and 0.6), the isosurface defines a compact region of very high vapor fraction. The spatial extent of this vapor-rich zone is clearly anchored to the abrupt channel constriction, with this connection becoming evident starting from the 0.6 isosurface level.

As the vapor volume fraction threshold decreases, the corresponding isosurface encompasses a larger volume of the flow. At the lower thresholds (0.4 and 0.2), the isosurfaces exhibit increasingly complex and irregular shapes. This morphological complexity at low volume fraction levels highlights the diffuse and intermittent nature of the vapor distribution in the peripheral zones of the cavitating flow. The significant expansion of the isosurface volume at the 0.2 threshold underscores the extensive spatial footprint of the vapor phase, even at relatively low concentrations.

Figure 5e presents a bar chart showing the relationship between the values of the vapor phase volume fraction and the relative volume (Viso/Vtotal)·100%, where Viso denotes the volume of the region bounded by the corresponding isosurface and the channel walls, and Vtotal is the total channel volume. It should be noted that Figure 5e provides individual bar chart of values for the cavitation regions near the upper and lower walls, as well as their combined total. As seen from the bar chart, an increase in the vapor volume fraction threshold leads to a sharp decrease in the relative volume, indicating that regions with high vapor phase saturation occupy a significantly smaller portion of the modeled domain. For example, the isosurface with a vapor volume fraction of 0.2 encompasses about 3.18% of the total volume, whereas at a threshold of 0.8 it covers only 0.048%.

At all isosurface levels, the upper and lower cavities are clearly distinguishable. The bar chart in Figure 5e quantitatively demonstrates that the upper cavity has a consistently larger relative volume than the lower one. This reflects the observed flow asymmetry and aligns with the experimental observations (Figure 4a,b), although the underlying cause of this asymmetry is not fully understood and is not investigated in the present work.

4.3. Pressure, Velocity, and Turbulent Kinetic Energy Distributions Inside the Channel

4.3.1. Pressure Distribution

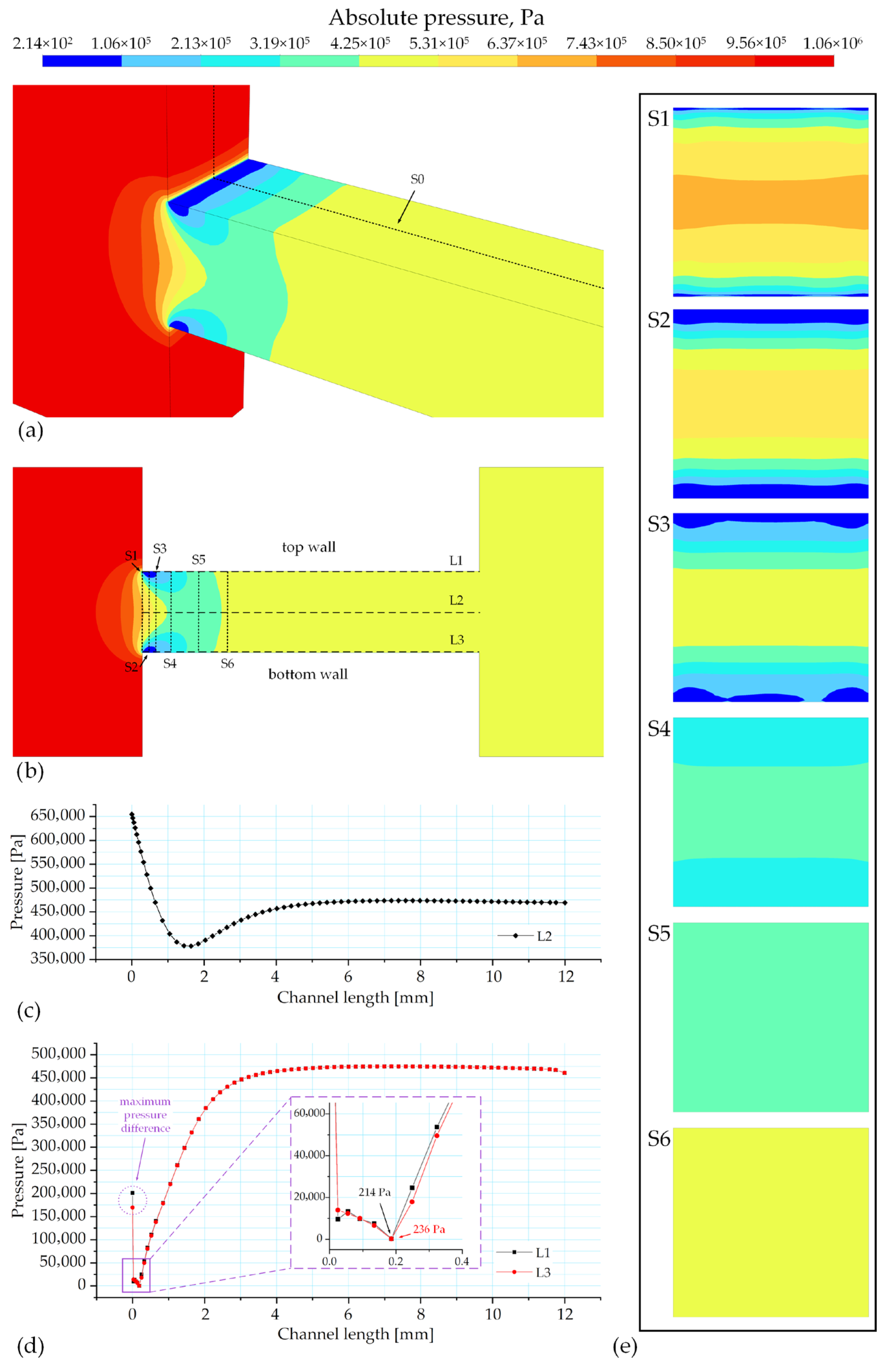

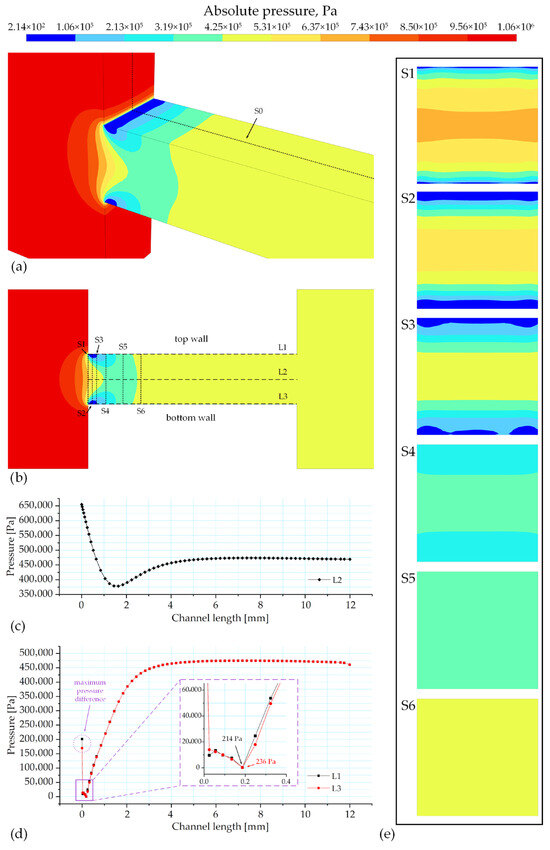

Figure 6 presents the results of the numerical simulation of the mean absolute pressure distribution in the investigated channel. Figure 6a shows a three-dimensional isometric visualization of the pressure field, providing a spatial overview of its distribution in the flow. Particular attention is drawn to the regions of sharp pressure drop, as these areas spatially correlate with the cavitating regions observed in the time-integrated flow structure (Figure 4). In Figure 6a, the position of the longitudinal section S0 is also indicated, which is shown in detail in Figure 6b.

Figure 6.

Distribution of the mean absolute pressure in the channel: (a) three-dimensional view; (b) pressure along the longitudinal section with the indication of analysis lines; (c) pressure along the central axis (L2); (d) pressure along the upper and lower walls (L1 and L3); (e) pressure contours in cross-sections S1–S6.

Figure 6b shows the longitudinal section passing through the channel axis, where lines are presented to evaluate the pressure distribution along the axis (L2), along the upper (L1) and lower (L3) walls, as well as the positions of six cross-sections (S1–S6) for the analysis of transverse pressure distribution. Figure 6b highlights that in the region upstream of the investigated channel (before the sharp contraction), a uniform pressure distribution is observed. In the inlet region of the investigated channel, localized zones of low-pressure form near the upper and lower walls (visible as blue and light-blue regions). Downstream of the channel constriction, in the region following the low-pressure zone, a gradual pressure recovery is observed. The view shows a symmetric pressure distribution with respect to the horizontal axis L2, which reflects the symmetry inherent to the steady-state solution and indicates the numerical convergence and spatial regularity of the simulated flow field in this section.

Figure 6c shows the pressure distribution along the central axis of the channel (L2). It can be seen that at a distance of 1.6 mm from the inlet of the investigated channel, the pressure drops sharply to a minimum value of about 378 kPa, after which it gradually increases, reaches a relatively stabilized level, and then slightly decreases near the investigated channel outlet (at the place of sudden channel expansion).

Figure 6d presents graphs comparing the pressure distribution along the lines running through the middle of the upper wall (L1) and the lower wall (L3) of the investigated channel. As seen from the graph, at the channel inlet, two points are marked (circled): 201 kPa on the upper wall (L1) and 169 kPa on the lower wall (L3). The difference between these values (32 kPa) represents the maximum pressure differential observed between the two walls. Further along the investigated channel walls, sharp pressure drops are observed. It is particularly evident in the zoomed-in fragment of the graph, which shows the points with the minimum detected pressure values of 214 Pa for L1 and 236 Pa for L3, located approximately ~0.19 mm from the entrance of the investigated channel. Such pressure values, being close to the saturation pressure level for the hydraulic oil AMG-10, which corresponds to the localization of an isosurface with a vapor volume fraction of 0.8. Downstream of the pressure minimum, the pressure along both walls recovers, eventually reaching a stable plateau. In this downstream region, the pressure difference between the upper and lower walls diminishes to a negligible level.

Figure 6e presents the pressure distributions in the cross-sections S1–S6 of the investigated channel. In cross-sections S1 and S2, a relatively high pressure is observed in the central part of the channel, which gradually decreases toward the upper and lower walls. In these cross-sections, the contraction of the jet is clearly visible. At the same time, the pressure distribution appears symmetric with respect to the notional horizontal axis passing through the center of the cross-sections. In section S3, a more pronounced low-pressure region is observed near the upper wall compared to the lower one. At the same time, the pressure profile near the lower wall exhibits a slight asymmetry with respect to the vertical axis of the section. In sections S1, S2, and S3, zones of locally reduced pressure (blue regions) are observed, which spatially coincide with the cavitating regions identified in Figure 4.

Further downstream, in sections S4, S5, and S6, the pressure gradually increases near the upper and lower walls. However, the distribution becomes more uniform only after section S6, indicating a spatial transition toward a more homogeneous pressure field. These observations confirm the presence of a spatial pressure recovery region downstream of the cavitation zone and the achievement of a more uniform pressure distribution in the far field.

4.3.2. Velocity Distribution

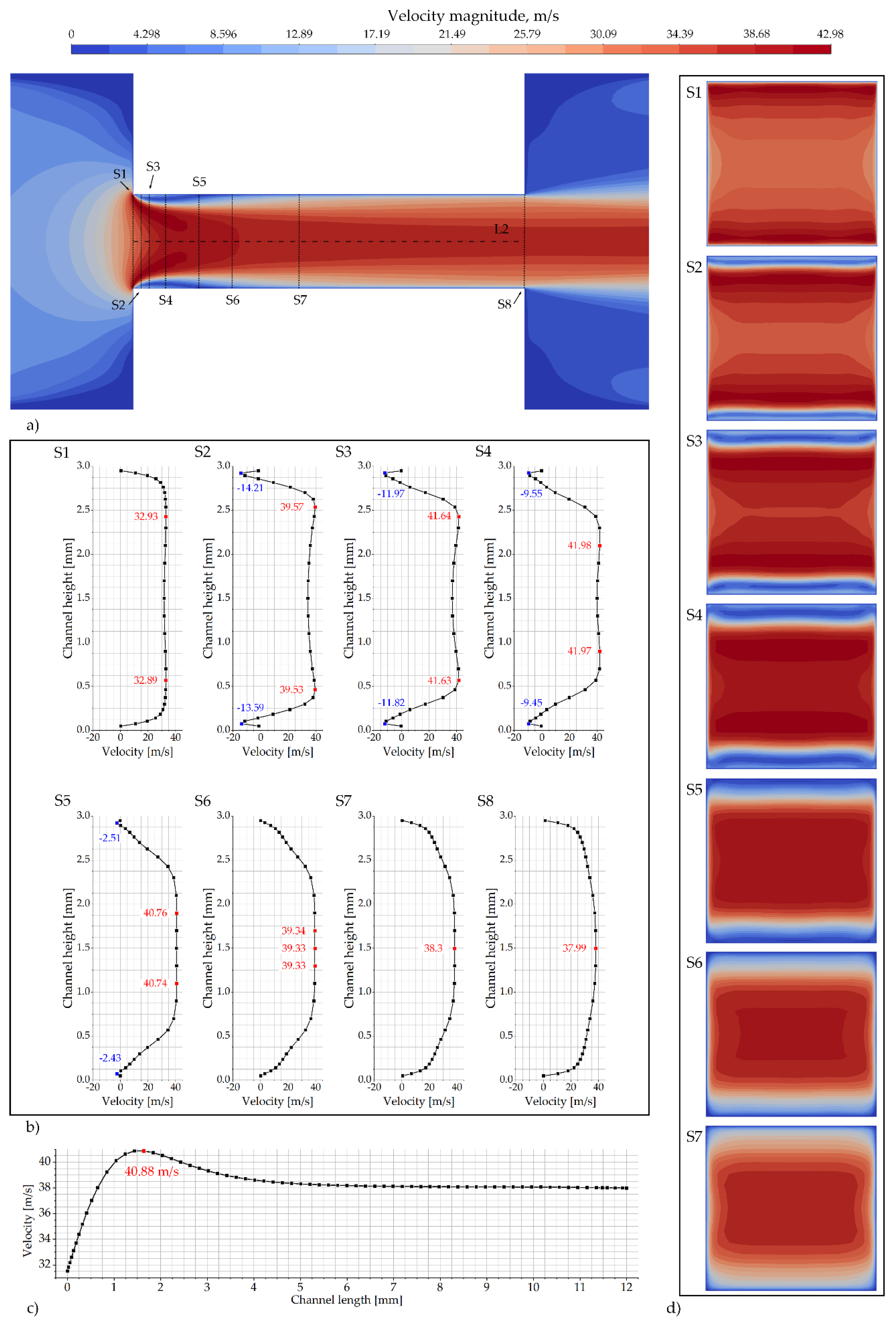

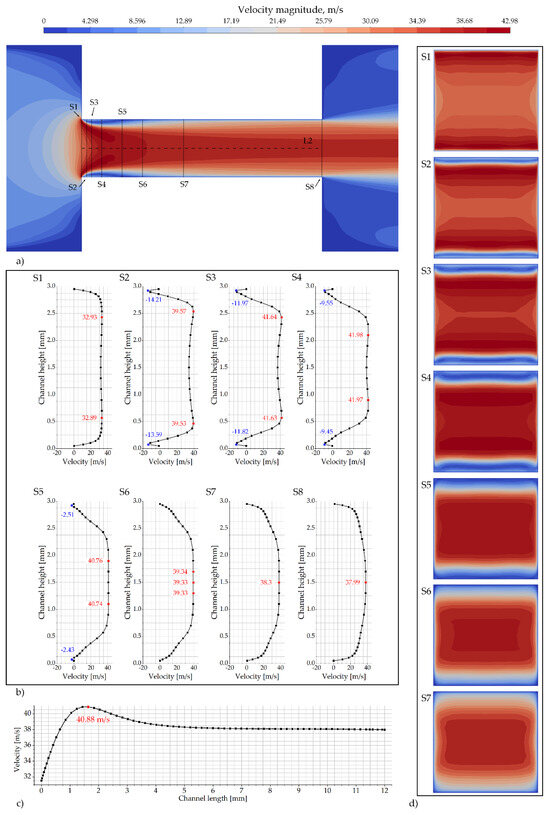

Figure 7 shows the mean velocity distributions in the channel obtained from numerical simulations. Figure 7a presents the velocity contours in the longitudinal section S0, with the positions of cross-sections S1–S8 indicated, which are used in Figure 7b,d for a detailed analysis of velocity profiles across the channel height and cross-sectional velocity contours. The line L2 (channel axis) is also indicated, and the velocity distribution along this line is presented in Figure 7c.

Figure 7.

Mean velocity distribution in the channel: (a) velocity in longitudinal section with the indication of lines for analysis; (b) velocity distribution along the vertical centerline in cross-sections S1–S8; (c) velocity along the central axis (L2); (d) velocity contours in cross-sections S1–S7.

In Figure 7a, the flow structure exhibits distinct spatial regions: an upstream region with uniform flow in the expanded inlet part of the channel (before S1), followed by a flow constriction region (between S1 and S6) characterized by low and high velocity gradients, and a downstream region (after S6) with gradually decreasing velocity gradients.

After the inlet of the investigated channel, the velocity field shows a high-speed core near the channel axis and low-velocity zones adjacent to the walls. These near-wall, low-velocity zones spatially coincide with the cavitation regions.

Figure 7b illustrates the velocity distribution along the vertical centerline in cross-sections S1–S8. The maximum and minimum observed velocity values are highlighted in red and blue, respectively.

In sections S1–S4, double peaks of maximum velocity are observed, positioned symmetrically with respect to the channel axis. The distance between these peaks gradually decreases from section S1 to S4. This pattern is consistent with two symmetric high-speed regions above and below the channel axis (Figure 7a). Along the channel axis itself, the velocity is lower than in these lateral jets, which is particularly evident in S3 and S4, where the local velocity maxima exceed 41 m/s. The global velocity maximum is found at section S4 and reaches approximately 41.98 m/s. This distribution characterizes a flow structure with strong lateral acceleration within the constriction. Near the channel walls, regions of reverse flow (negative velocity) appear in the sections S2 and S3. The intensity and spatial footprint of these regions diminish downstream in sections S4 and S5. No reverse flow is observed at the walls in S6, indicating the cessation of the recirculation zones present further upstream. At section S6, the two symmetric high-velocity regions have merged into a single, broader central jet. The velocity distribution in this section exhibits a turbulent-like profile that is more uniform than in the upstream sections. Further downstream, in sections S7 and S8, the velocity profile evolves into a shape characteristic of a fully developed turbulent flow in a channel, exhibiting a distinct velocity peak on the channel centerline and monotonically decreasing toward the walls.

Figure 7c shows the velocity profile along the channel axis L2. The profile features a steep rise, reaching a maximum of 40.88 m/s at a distance of ~1.6 mm from the inlet of investigated channel. This high-velocity peak is associated with the flow constriction. Further downstream, the velocity declines to a nearly constant value of approximately 38 m/s, which is maintained over the remaining length of the profile.

Figure 7d shows the velocity contours in the transverse sections S1–S7. This sequence allows for a comparative analysis of the spatial evolution of the mean velocity distribution. The contours in S1 and S2 exhibit a structure with double peaks of maximum velocity located symmetrically near the upper and lower walls, while the velocity is lower at the channel axis. In sections S3 through S5, this double-peak structure weakens: the peaks move closer to the channel axis, and the velocity at the axis increases. In section S6, the distribution transitions to a profile with a single, central velocity maximum. Finally, in section S7, the flow is characterized by a stable, single-peak velocity profile with velocity decreasing monotonically from the center to the walls. The progression of contour shapes across the sections illustrates the spatial transformation of the flow from a bifurcated inlet pattern to a consolidated, axisymmetric jet downstream of the constriction.

4.3.3. Distribution of Turbulent Kinetic Energy (TKE)

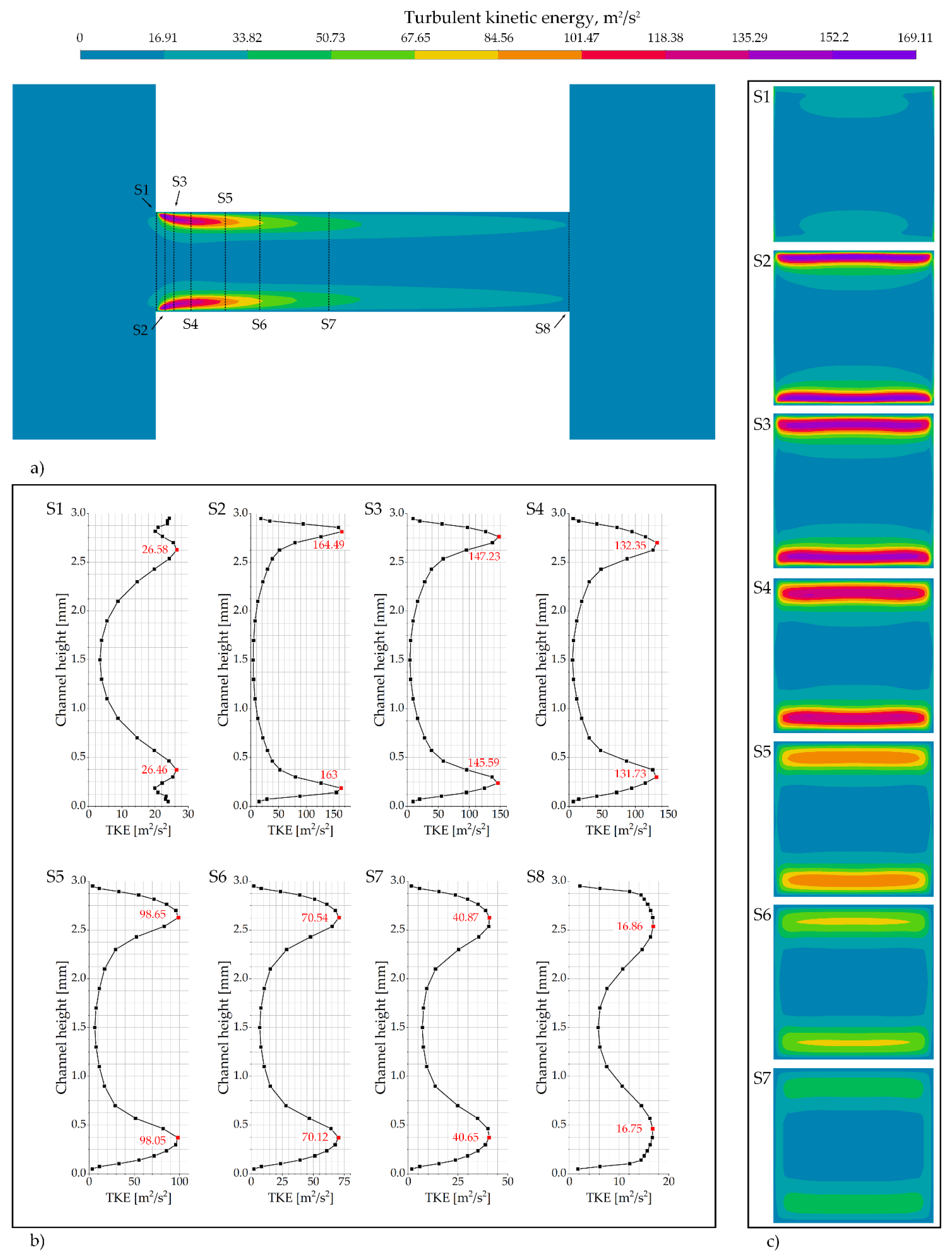

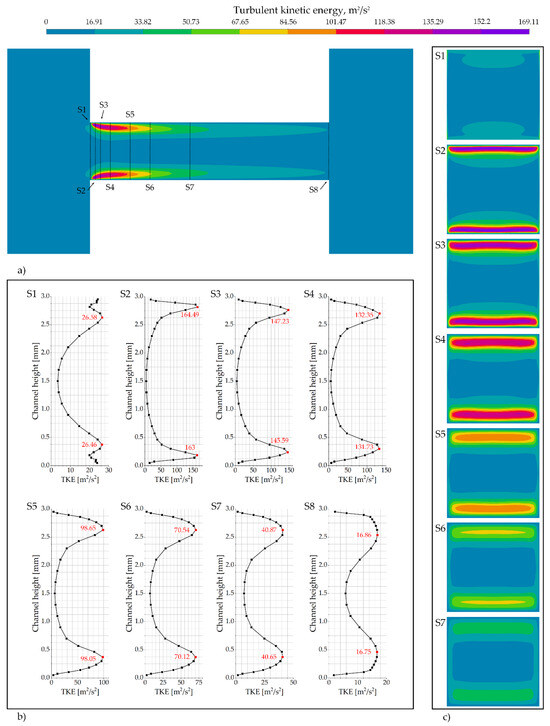

Figure 8a presents the distribution of the mean turbulent kinetic energy (TKE) on the central longitudinal plane of the channel. The highest levels of TKE are localized in the region at the beginning of the investigated channel, particularly near the upper and lower walls. This spatial distribution of intense turbulence correlates with the regions of high vapor fraction shown in Figure 4. Further downstream, the TKE level diminishes, and its distribution becomes more uniform along the length of the channel. At the outlet, the TKE reaches its minimum value in the domain.

Figure 8.

Distribution of mean turbulent kinetic energy (TKE) in the channel: (a) TKE contours on the longitudinal section (analysis lines indicated); (b) TKE profiles along the vertical centerlines of cross-sections S1–S8; (c) TKE contours on selected cross-sections S1–S7.

Figure 8a shows the lines defining the locations of the cross-sections S1–S8. For these cross-sections, a detailed analysis of the turbulent kinetic energy distribution is presented along the vertical centerlines (Figure 8b), along with the contour distributions of turbulent kinetic energy in these sections (Figure 8c).

Figure 8b shows the vertical distribution of turbulent kinetic energy (TKE) along the centerlines of cross-sections S1–S8. In section S1, the TKE level is low across the entire height, with the highest values (26.58 m2/s2) near the upper wall. A sharp increase in TKE magnitude is observed in sections S2 through S4, with maxima of 164.49 m2/s2, 147.23 m2/s2, and 132.35 m2/s2, respectively, located near the upper wall. These peak values coincide spatially with the core of the high-speed lateral jets (Figure 7). Starting from section S5, the peak TKE values decline monotonically (S5: 98.65 m2/s2, S6: 70.54 m2/s2, S7: 40.87 m2/s2). Concurrently, the TKE distribution across the height becomes more uniform, and the local gradients weaken. In the most downstream section, S8, the TKE reaches its lowest level in the series (16.86 m2/s2), approaching a nearly uniform distribution.

Figure 8c shows the contours of turbulent kinetic energy in cross-sections S1–S8. The distributions are visualized using a color scale from low (blue) to high (purple) values, enabling a comparative analysis of how the turbulence intensity field changes from the inlet to the outlet of the investigated channel.

In the inlet section S1, the TKE level is low overall, with slightly elevated values appearing near the upper and lower walls. In sections S2 through S4, two symmetric regions of high TKE intensity develop near the walls, where the energy reaches its maximum values in the entire sequence. Starting from section S5, the magnitude of these TKE peaks diminishes. Concurrently, the TKE distribution across the section becomes more homogeneous, and the lateral gradients weaken.

Thus, the TKE field exhibits a clear spatial trend: high, localized intensity in the shear layers downstream of the inlet of the investigated channel contrasts with a nearly uniform, low-intensity distribution at the outlet. This spatial pattern of turbulence intensity is consistent with the distributions of pressure and velocity, and it correlates spatially with the extent of the cavitating region.

5. Conclusions

The investigation of cavitation in the aviation hydraulic fluid AMG-10 within a small-scale rectangular throttle channel for the relative pressure drop Δp = 0.58, using a quasi-steady-state modeling approach and time-integrated experimental data, allowed the following conclusions to be drawn:

- The applied quasi-steady-state numerical model, based on the Realizable k–ϵ turbulence model combined with the Enhanced Wall Treatment method and the Zwart–Gerber–Belamri cavitation model, reliably reproduces the shape and size of the cavitation regions, demonstrating good qualitative and quantitative agreement with the experimental data. Comparison of the pressure between numerical simulations and experimental measurements along the upper and lower walls of the investigated channel shows differences of less than 10%, confirming the accuracy of the model.

- Quantitatively, the volume delineated by the vapor fraction isosurface decreases significantly as the threshold is raised. For instance, an isosurface of 0.2 occupies approximately 3.18% of the channel volume, whereas at a threshold of 0.8, it constitutes merely 0.048%. This sharp decrease indicates a strong localization of regions with high vapor concentration, which is crucial for assessing the spatial structure of cavitation. The analysis of vapor volume fraction iso-surfaces at different threshold values revealed a consistent asymmetric nature of the cavitation. Specifically, the upper cavity consistently exhibited a larger volume compared to the lower cavity. This asymmetry was observed in both experimental and numerical results, confirming the reliability of the computational model in capturing this mean feature. While this study confirms the consistency of the phenomenon, identifying its physical cause remains an important challenge for future research.

- Numerical modeling identifies points of minimum mean absolute pressure located ~0.19 mm from the inlet, with values of 214 Pa at the upper wall and 236 Pa at the lower wall. These pressures are within the saturation pressure of AMG-10. The spatial location of these calculated low-pressure values coincides with the region where the model predicts a high vapor volume fraction, confirming the internal consistency of the numerical solution.

- In the investigated channel, the velocity field exhibits a structure with double peaks of maximum velocity near the upper and lower walls. The local velocity maxima in these peaks reach approximately 41.98 m/s, exceeding the maximum velocity along the channel axis (40.88 m/s).

- The maximum level of turbulent kinetic energy (TKE ≈ 164.5 m2/s2) is localized in section S2, immediately downstream of the channel constriction. This region of peak TKE spatially coincides with the zones of highest vapor fraction and intense velocity shear. Further downstream, the TKE magnitude decreases, and its distribution becomes increasingly uniform across the channel cross-section. At the outlet, the TKE field is characterized by low intensity and minimal spatial variation.

Thus, the conducted study demonstrates that a quasi-steady-state numerical model can reliably predict the time-averaged structure of cavitating flow in small-scale throttle channels for the aviation hydraulic fluid AMG-10. The obtained mean fields of pressure, velocity, and turbulent kinetic energy provide a consistent, quantitative description of the flow anatomy, highlighting the spatial relationships key to cavitation. This dataset and validated modeling approach can be valuable for the design and analysis of hydraulic systems.

In future studies, the research aims to extend the numerical modeling by taking into account unsteady processes associated with cavitation bubble collapse. Additionally, the influence of different pressure drops on the structure and intensity of cavitation is planned to be investigated.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.B. and T.T.; methodology, V.B. and T.T.; validation, V.B.; formal analysis, V.B. and T.T.; investigation, V.B. and T.T.; resources, V.B. and T.T.; data curation, V.B. and T.T.; writing—original draft preparation, V.B. and T.T.; writing—review and editing, V.B. and T.T.; visualization, V.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed at the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chahine, G.L.; Franc, J.-P.; Karimi, A. Cavitation and Cavitation Erosion. In Advanced Experimental and Numerical Techniques for Cavitation Erosion Prediction; Kim, K.-H., Chahine, G., Franc, J.-P., Karimi, A., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 3–20. ISBN 978-94-017-8539-6. [Google Scholar]

- Konami, S.; Nishiumi, T. Hydraulic Control Systems: Theory And Practice; World Scientific Publishing Company: Singapore, 2016; ISBN 978-981-4759-66-3. [Google Scholar]

- Manring, N.D.; Fales, R.C. Hydraulic Control Systems; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019; ISBN 978-1-119-41647-0. [Google Scholar]

- Andrenko, P.; Hrechka, I.; Khovanskyi, S.; Rogovyi, A.; Svynarenko, M. Improving the Technical Level of Hydraulic Machines, Hydraulic Units and Hydraulic Devices Using a Definitive Assessment Criterion at the Design Stage. J. Mech. Eng. 2021, 18, 57–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Tomovic, M.; Liu, H. Commercial Aircraft Hydraulic Systems: Shanghai Jiao Tong University Press Aerospace Series; Elsevier Science: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; ISBN 978-0-12-419972-9. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, L.; Yan, H.; Ren, Y.; Li, L.; Cai, C. Numerical Investigation of Flow Force and Cavitation Phenomenon in the Pilot Stage of Electrical-Hydraulic Servo Valve under Temperature Shock. Machines 2022, 10, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Saha, B.K.; Shakib, M.S.N.; Li, S.; Jihan, J.I. A Numerical Analysis of Pressure Characteristics in the Deflector Jet Pilot Stage Valve with an Innovative Deflector Deflection. Flow Meas. Instrum. 2024, 99, 102674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aung, N.Z.; Li, S. A Numerical Study of Cavitation Phenomenon in a Flapper-Nozzle Pilot Stage of an Electrohydraulic Servo-Valve with an Innovative Flapper Shape. Energy Convers. Manag. 2014, 77, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Aung, N.Z.; Li, S.; Zou, C. Effect of Oil Viscosity on Self-Excited Noise Production Inside the Pilot Stage of a Two-Stage Electrohydraulic Servovalve. J. Fluids Eng. 2018, 141, 011106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Xu, Y.; Chen, Z.; Wang, W.; Aung, N.Z.; Li, S. Cavitation Suppression in the Nozzle-Flapper Valves of the Aircraft Hydraulic System Using Triangular Nozzle Exits. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2021, 112, 106598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Yan, H.; Zhang, H.; Li, J. Numerical Simulation and Experimental Research of the Flow Force and Forced Vibration in the Nozzle-Flapper Valve. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2018, 99, 550–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Yuan, Z.; Tariq Sadiq, M. Numerical Simulation and Experimental Research on Flow Force and Pressure Stability in a Nozzle-Flapper Servo Valve. Processes 2020, 8, 1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Li, M.; Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Kong, D. Cavitation Evolution Mechanism and Periodic Flow of Aviation Pressure Poppet Valve. Flow Meas. Instrum. 2025, 102, 102811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Ren, Y.; Yao, L.; Dong, L. Analysis of the Internal Characteristics of a Deflector Jet Servo Valve. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. 2019, 32, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazhenko, V.N.; Mochalin, E.V.; Jian-Cheng, C. Mechanical Admixture Influence in the Working Fluid on Wear and Jamming of Spool Pairs from Aircraft Hydraulic Drives. J. Frict. Wear 2020, 41, 526–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, B.K.; Peng, J.; Li, S. Numerical and Experimental Investigations of Cavitation Phenomena Inside the Pilot Stage of the Deflector Jet Servo-Valve. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 64238–64249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Yan, H.; Mao, Q.; Zuo, Z.; Hao, H. A Model-Based Investigation of the Performance Robustness of the Deflector Jet Servo Valve. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 10428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xia, Y. Analysis and Optimization of the Pilot Stage of Jet Pipe Servo Valve. Alex. Eng. J. 2022, 61, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Wang, J.; Li, M.; Ryu, S. Experimental and Numerical Analysis on Vortex Cavitation Morphological Characteristics in U-Shape Notch Spool Valve and the Vortex Cavitation Coupled Choked Flow Conditions. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2022, 189, 122707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, W.; Ren, L.; Bai, Y.; Bao, G. Numerical Simulation of the Temperature Rise and Cavitation Flow in a Hydraulic Slide Valve. Flow Meas. Instrum. 2024, 96, 102553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, W.; Yang, Q.; Bao, G. Numerical Simulation of the Multiscale Cavitation Flow in a Hydraulic Slide Valve. Flow Meas. Instrum. 2025, 102, 102805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, D.; Lee, S.; Ahn, K. Effects of Non-Uniform Center-Flow Distribution and Cavitation on Continuous-Type Pintle Injectors. Aerospace 2024, 11, 847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Pei, Q.; Liu, Z.; Luo, S.; Zhou, L.; Li, J.; Chen, L. Parametric Optimization of Surface Textures in Oil-Lubricated Long-Life Aircraft Valves. Lubricants 2024, 12, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhu, C.; Meng, B.; Li, S. Challenges and Solutions for High-Speed Aviation Piston Pumps: A Review. Aerospace 2021, 8, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Zhao, C.; Hong, H.; Cheng, G.; Yang, H.; Feng, S.; Zhai, J.; Xiao, W. Optimization of the Outlet Unloading Structure to Prevent Gaseous Cavitation in a High-Pressure Axial Piston Pump. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part C J. Mech. Eng. Sci. 2022, 236, 3459–3473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Peng, X.; Meng, X.; Jiang, J.; Ma, Y. Influence of Cavitation on the Heat Transfer of High-Speed Mechanical Seal with Textured Side Wall. Lubricants 2023, 11, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazama, T. Experimental Study of Jet Cavitation Erosion Applicable to Oil and Water-Hydraulic Equipment. Mater. Perform. Charact. 2018, 7, 355–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazhenko, V. The Influence of Contaminated Hydraulic Fluid on the Relative Volume Flow Rate and the Wear of Rubbing Parts of the Aviation Plunger Pump. Aviation 2019, 23, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Yang, G.; Wu, G.; Li, X. Oxidative Deterioration Effect of Cavitation Heat Generation on Hydraulic Oil. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 119720–119727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazama, T.; Aoki, S.; Kobessho, M. Cavitation Erosion Characteristics of High Bulk Modulus Oils: Preliminary Evaluation Experiment for Hydraulic Equipment. Mater. Perform. Charact. 2020, 9, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Qi, N.; Jiang, J. Effect of Oil Viscosity on Hydraulic Cavitation Luminescence. Fluid Dyn. 2021, 56, 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterland, S.; Müller, L.; Weber, J. Influence of Air Dissolved in Hydraulic Oil on Cavitation Erosion. Int. J. Fluid Power 2021, 22, 373–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iga, Y.; Okajima, J.; Takahashi, S.; Ibata, Y. Occurrence Characteristics of Gaseous Cavitation in Oil Shear Flow. Phys. Fluids 2022, 34, 023313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterland, S.; Günther, L.; Weber, J. Experiments and Computational Fluid Dynamics on Vapor and Gas Cavitation for Oil Hydraulics. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2023, 46, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polášek, T.; Bureček, A.; Hružík, L.; Ledvoň, M.; Dýrr, F.; Olšiak, R.; Kolář, D. Experimental Study of Multiphase Flow Occurrence Caused by Cavitation during Mineral Oil Flow. Phys. Fluids 2024, 36, 113377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bureček, A.; Hružík, L.; Vašina, M. Determination of Undissolved Air Content in Oil by Means of a Compression Method. Stroj. Vestn. J. Mech. Eng. 2015, 61, 477–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, T.-H.; Liou, W.W.; Shabbir, A.; Yang, Z.; Zhu, J. A New k-ϵ Eddy Viscosity Model for High Reynolds Number Turbulent Flows. Comput. Fluids 1995, 24, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaddour, A.; Ouadha, A. Numerical Study of the Flow in a Two-Phase Nozzle for Trilateral Flash Cycle Applications. Int. J. Thermofluids 2023, 19, 100393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.-J.; Shi, J.-W.; Cheng, X.-L.; Zhang, Z.; He, Y.-Q.; Tao, W.-Q. Numerical Study on the Cavitation Flow Characteristics of High-Pressure Fuel in Injector Orifices Based on Compressible Non-Isothermal Model. AIP Adv. 2023, 13, 115205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutlu, Y.; Dönmez, A.H.; Karadağ, M.A.; Göklüberk, P. Pressure Drop and Cavitation Optimization of a Relief Valve Featuring Quick Coupling Used in Radar Systems. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2025, 50, 2321–2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Jin, H.; Wang, C.; Liu, X. Investigation on Flow and Cavitation Characteristics in Flow Channel of Multistage Depressurization Valve. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part E J. Process Mech. Eng. 2025, 09544089251318109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chen, Y.; Li, M.; Xu, Y.; Wang, B.; Dang, X. Numerical Study on the Working Performance of a Streamlined Annular Jet Pump. Energies 2020, 13, 4411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Guo, R.; Wang, G.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, Q.; Yu, L.; Zhang, Q. Study on Cavitation of Port Plate of Seawater Desalination Pump with Energy Recovery Function. Processes 2023, 11, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kevorkijan, L.; Palomar-Torres, A.; Torres-Jiménez, E.; Mata, C.; Biluš, I.; Lešnik, L. Obtaining the Synthetic Fuels from Waste Plastic and Their Effect on Cavitation Formation in a Common-Rail Diesel Injector. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onishi, T.; Peng, Y.; Ji, H.; Peng, G. Numerical Simulations of Cavitating Water Jet by an Improved Cavitation Model of Compressible Mixture Flow with an Emphasis on Phase Change Effects. Phys. Fluids 2023, 35, 073333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwart, P.J.; Gerber, A.G.; Belarmi, T. A Two-Phase Flow Model for Predicting Cavitation Dynamics. In Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference on Multiphase Flow, Yokohama, Japan, 30 May–4 June 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Jansson, M. Implementing a Zwart-Gerber-Belamri Cavitation Model; CFD with OpenSource Software; Chalmers University of Technology: Gothenburg, Sweden, 2018; p. 18. [Google Scholar]

- Singhal, A.K.; Athavale, M.M.; Li, H.; Jiang, Y. Mathematical Basis and Validation of the Full Cavitation Model. J. Fluids Eng. 2002, 124, 617–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarasenko, T.; Badakh, V.; Makarenko, M.; Lukianov, P.; Dubkovetskiy, I. Determining the Mechanism for Generating Cavitation Pressure Fluctuations in Throttle Devices at High-Head Throttling of Liquid. East. Eur. J. Enterp. Technol. 2024, 4, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.