Abstract

As international lunar exploration shifts from mainly understanding the Moon to equally prioritizing its utilization, the requirement for highly similar lunar regolith simulants has grown. Current simulants, produced mainly by mechanical crushing and sieving, reproduce mechanical properties but lack space-weathered microstructures. However, this absence results in significant discrepancies in critical properties such as thermal conductivity and adsorption–desorption behavior, which undermine the reliability of ground-based resource utilization tests. To address this issue, this paper proposes a new preparation method for lunar regolith simulants, which simulates the micrometeorite impact process by utilizing the instantaneous high temperature, pressure, and high-velocity impact generated from the detonation of high-energy explosives in a sealed container. Preliminary experiments confirm that the method produces agglutinates, glass spherules, and porous structures resembling those in lunar regolith. The thermal conductivity of the modified simulant decreases significantly, approaching that of lunar regolith. Further refinement of the process, supported by quantitative 3D characterization, will enable the production of even more similar simulants, providing a reliable material foundation for lunar exploration, in situ resource utilization, and lunar construction activities.

1. Introduction

Lunar regolith refers to the layer of loose, fragmental material overlying the lunar bedrock. It is primarily formed by the fragmentation of surface rocks through meteorite impacts, cosmic ray irradiation, and extreme temperature cycling [1]. During the lunar exploration phase, lunar regolith simulants are typically particulate mixtures formulated by combining raw materials, such as volcanic ash and various minerals in specific proportions, followed by processing steps including crushing, drying, sieving, and recombination [2]. Based on analyses of samples returned from lunar exploration missions, researchers have developed a variety of simulants that closely match the mechanical characteristics of lunar regolith [2,3,4], thereby supporting ground tests for lunar landing, surface exploration, and sampling tasks.

However, lunar regolith has not merely undergone mechanical fragmentation and recombination; it has also experienced prolonged and complex space weathering [5], resulting in distinctive weathered microstructures. Space weathering refers to the comprehensive alteration process that affects the surface materials of airless planetary bodies. It involves physical comminution, chemical modification, and optical changes induced by long-term exposure to micrometeoroid impacts, solar wind irradiation, cosmic ray radiation, and extreme temperature cycling. These space weathering produce unique structural characteristics on and within regolith particles [6]. These structures are responsible for the fundamental differences between lunar regolith and terrestrial soils and are critical determinants of lunar regolith properties. Therefore, to prepare more similar simulants, the formation process that creates these structures must be reproduced during preparation.

Such microstructures significantly influence various physical properties of lunar regolith, including thermal properties [7] and spectral reflectance properties [8]. A total of 386.977 kg of lunar samples have been collected from six Apollo missions, three Luna missions, the Chang’e-5 and the Chang’e-6 mission [9]. The scarcity of returned lunar samples restrict the feasibility of large-scale ground experiments. To prepare more similar lunar regolith simulants, researchers use methods such as laser irradiation and kinetic impact to simulate space weathering [10], yet these methods have the limitation of single-effect simulation and cannot reproduce the entire process of fragmentation, melting, and agglutination that lunar regolith undergoes. With the focus of international lunar exploration shifting from “understanding the Moon” to “understanding and utilizing it jointly” [11]. Improved methods to simulate space weathering are needed to develop highly similar lunar regolith simulants for use in resource utilization and lunar construction experiments.

To address this issue, this study proposes an innovative preparation method for lunar regolith simulants with high similarity in weathering characteristics. Based on the physical formation process of lunar regolith, the approach uses the instantaneous high temperature, pressure, and impact generated by detonating a high-energy explosive in a sealed container to modify raw materials. This process effectively simulates the melting and agglutination behaviors observed in space-weathered lunar regolith. Section 2 reviews current methods and limitations in lunar regolith simulant preparation; Section 3 proposes a detonation-based method to simulate space weathering; Section 4 details the experimental preparation and characterization of modified simulants; Section 5 discusses potential applications in lunar exploration and research.

2. Current Methods and Limitations in Lunar Regolith Simulant Preparation

At present, lunar regolith simulants are mainly prepared through mechanical crushing, sieving, and recombination. The preparation process involves mixing different minerals, followed by crushing, stirring, blending, and drying to obtain lunar regolith simulants. This method allows for the regulation of particle size gradation, mineral composition, and relative density. For example, the Institute of Geology and Geophysics of the Chinese Academy of Sciences has prepared IGG-01 lunar regolith simulant based on Chang’e-5 sample properties. IGG-01 fills a gap in medium-titanium (3–6.7 wt%) basaltic simulants and closely matches the chemical and mineral composition, particle size distribution, and specific surface area (0.34 m2/g vs. 0.56 m2/g for Chang’e-5 lunar regolith) of the returned samples [12,13]. Similarly, Tongji University has produced the Tongji-1 (TJ-1) simulant using red volcanic ash from Jingyu County, Jilin Province. After drying, crushing, and sieving, its mechanical behavior under different gradations was tested, offering a reference for landing impact experiments. TJ-1’s physical and mechanical parameters generally fall within the estimated ranges for lunar mare regolith at 0–30 cm depth [4]. The mechanical properties of the prepared lunar regolith simulants are relatively close to those of lunar regolith, which have met the engineering requirements. Other lunar regolith simulants models both domestically and internationally are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Models of lunar regolith simulant [14].

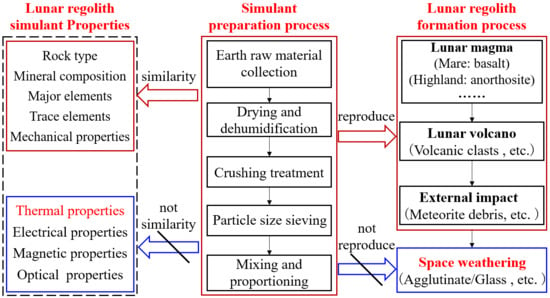

Currently, there are two main methods for preparing lunar regolith simulants. The first is the whole-rock simulation method, which utilizes terrestrial volcanic deposits or similar rocks as raw materials. These materials are dried, crushed, sieved, and classified into specific particle-size grades before being blended to match the gradation of lunar regolith. Additional components such as ilmenite or glass phases may be incorporated as needed [5]. The second approach is the single-mineral simulation method, whereby simulants are formulated by combining naturally occurring or synthetically produced individual minerals in proportions that reflect lunar regolith composition. Due to the higher cost and technical complexity associated with isolating or synthesizing pure minerals, the whole-rock method remains the more common and mature preparation route [2]. The preparation processes of the two types of lunar regolith simulants are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Current status of lunar regolith simulants development.

Although progress has been made in developing various lunar regolith simulants with representative mechanical properties, current models still exhibit notable limitations:

(1) Lunar regolith develops unique space weathering structures through complex formation processes. Current simulants, however, are typically produced by mechanical crushing and sieving, which cannot reproduce key physicochemical reactions, such as melting and agglutination that occur during regolith evolution. As a result, such simulants exhibit significant differences in space weathering structures compared to lunar regolith.

(2) Although conventional mechanically processed lunar regolith simulants can replicate key mechanical properties of lunar regolith (e.g., chemical composition, particle size distribution, and internal friction angle), their lack of characteristic space-weathering structures (e.g., agglutinates and glass spherules) leads to significant deviations in properties such as thermal conductivity and adsorption–desorption behavior.

(3) The current sample preparation and sieving methods are relatively simplistic. As a result, they cannot effectively correlate the structures of lunar regolith with the key mechanisms of its formation. Specifically, the influence of factors such as micrometeorite impact frequency and solar wind irradiation.

3. A Detonation-Based Preparation Method for Lunar Regolith Simulant

3.1. Formation and Evolution Mechanism of Lunar Regolith

Lunar regolith forms through complex physicochemical processes driven by both endogenic and exogenic forces. Endogenic forces mainly refer to the geological processes occurring within the lunar interior, including internal geological activities such as volcanic eruptions. These eruptions release magma that is cooled and fragmented into regolith precursors, as well as crustal movements that further break down surface rocks, thereby providing the material basis for lunar regolith formation [15]. Exogenic processes refer to space weathering, which continuously modifies regolith particles over time through micrometeorite impacts, solar wind irradiation, and cosmic ray implantation. These external forces cause fragmentation, melting, and agglutination of grains, ultimately producing the distinct weathered structures observed in lunar regolith [16].

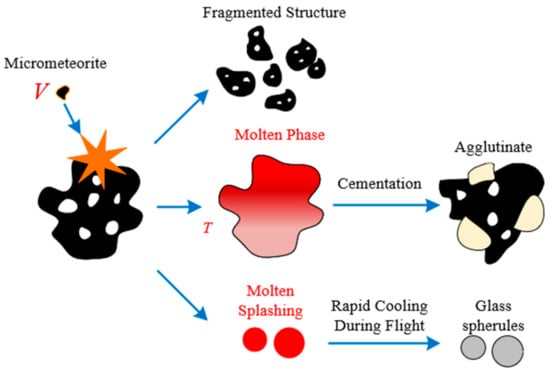

(1) Micrometeorite impact is a key driver of space weathering, the cumulative effects of which define the fundamental properties of lunar regolith [17]. Sustained impacts continuously fragment and exfoliate surface rocks, breaking primary debris into finer grains and creating stress-induced fracture textures, such as linear and planar features on particle surfaces [18]. Simultaneously, the instantaneous high temperature and pressure generated upon impact induce localized melting. Upon cooling, this melt binds adjacent particles into agglutinates, which represent typical secondary structures in lunar regolith. Some agglutinates even exhibit traces of multi-stage glass coatings, indicating repeated episodes of impact melting. A schematic of micrometeorite impacts is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Mechanism of micrometeorite impact.

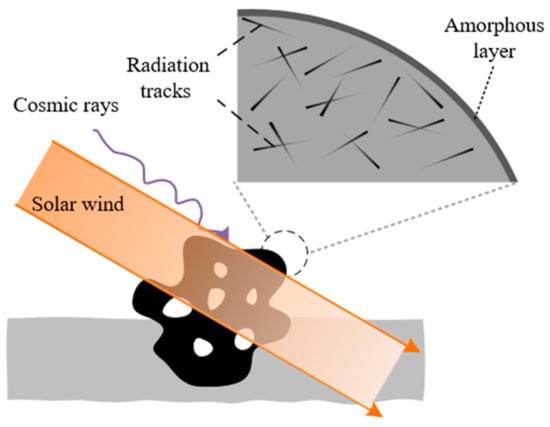

(2) Solar wind and cosmic ray implantation also modify lunar regolith particles. Solar wind protons implant into the surface layer of minerals, react with silicates in lunar regolith particles to form hydroxyl groups (OH−), and also participate in the formation of elemental iron particles. Furthermore, the long-term irradiation of cosmic rays and solar wind induces radiation tracks and lattice distortions on the mineral surface, accelerates particle fragmentation, and alters their chemical properties [16]. The interaction between solar wind and cosmic rays is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Mechanism of solar wind and cosmic ray action.

3.2. Mechanism of High-Energy Detonation Action

To produce lunar regolith simulants with high similarity in space weathering characteristics, it is essential to reproduce the melting and agglutination processes that occur during lunar regolith formation. This requires simulating the instantaneous high temperature, high pressure, and high-velocity impact conditions generated by micrometeorite impact. Building on conventional mechanical preparation methods, such as crushing, sieving, and recombination, this study introduces the application of high-energy explosives to provide the intense, transient energy required for such simulation.

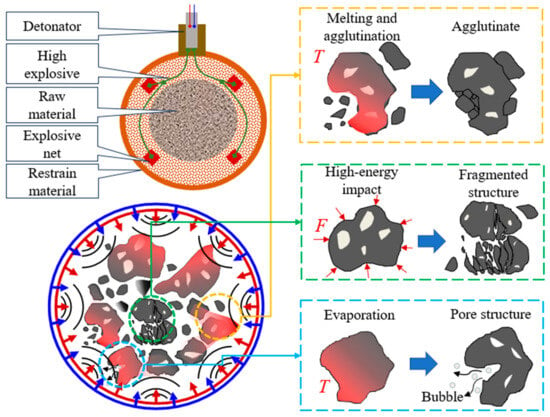

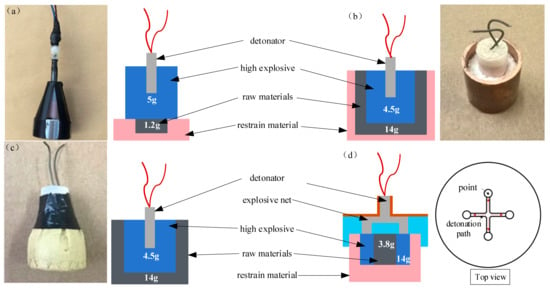

To prepare weathering-characteristic simulants based on this detonation approach, a high-energy explosive is initiated via a detonation network. Upon detonation, the explosive generates a combined high-temperature, high-pressure, and high-velocity impact loading field on the particle surfaces. This interaction closely approximates lunar micrometeorite impact conditions and triggers particle fragmentation, melting, and agglutination. The detonation device is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Explosive modification device and principle.

The particle modification mechanisms induced by detonation can be described in three main aspects: melting and agglutination, high-energy impact, and evaporation-bubble formation:

(1) The melting and agglutinating mechanism is a phase reconstruction process dominated by a high-temperature field. When raw materials are subjected to the instantaneous high temperature produced by detonation, the temperature can exceed the melting points of key mineral phases. The resulting molten material exhibits significantly reduced viscosity with increasing temperature [19], enabling flow and wetting behavior that promotes agglutination within and between particles.

(2) The high-energy impact mechanism is dominated by the mechanical loading from detonation-induced high pressure and shock waves. As the shock wave propagates through the raw material, it generates a complex internal stress field within the particles [20,21]. When the local stress exceeds the dynamic fracture strength of the minerals, micro-cracks initiate. Their propagation is controlled by microstructural features such as grain boundaries and defects [22], ultimately forming dendritic or networked crack systems.

(3) The evaporation-bubble formation mechanism is a comprehensive effect of heat and mass transfer. The instantaneous high temperature generated during detonation causes volatile components and certain low-melting-point minerals within the simulant to vaporize [23]. The resulting gases expand rapidly inside the particles, forming bubbles that solidify into pores upon cooling. The distribution, morphology, and connectivity of these pores directly influence key particle properties such as specific surface area and permeability [24].

Based on the analysis of lunar regolith formation and detonation mechanisms, this study employs high-energy explosives to generate a transient coupled environment of high temperature, high pressure, and intense mechanical impact. This environment acts on raw materials to simulate the micrometeorite-driven space weathering process, thereby reproducing the characteristic fragmentation, melting, and agglutinating behaviors of lunar regolith particles. The aim of this work is to prepare lunar regolith simulants with high structural similarity to space-weathered lunar regolith.

3.3. Simulation Analysis of Detonation Modification

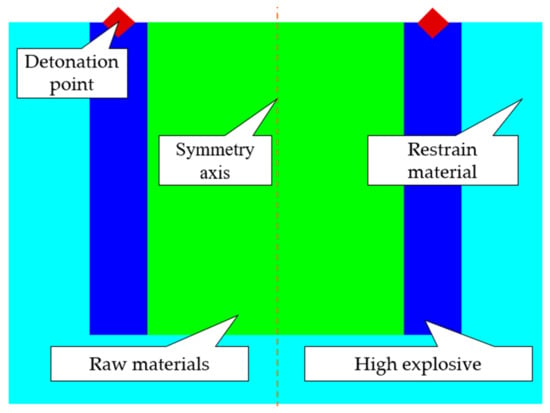

To evaluate the effect of the detonation modification, the detonation process was simulated using the explicit nonlinear dynamics software ANSYS (2024 R2) AUTODYN. AUTODYN is designed for modeling the transient response of materials under extreme loading conditions such as blast, impact, and shock [25]. A two-dimensional axisymmetric model was established, as illustrated in Figure 5. In the model, the green region represents the raw basalt sample (primarily SiO2), surrounded by a ring of HMX explosive. The outermost layer corresponds to the detonation chamber, which provides confinement during the explosion.

Figure 5.

Simulation model.

Smoothed Particle Hydrodynamics (SPH) is a numerical simulation method that discretizes continuous media into a system of particles, representing a meshless approach. In order to reproduce the particle splash and the deformation of each part in the detonation process, the SPH method is used to perform the simulation [26]. The continuous medium is discretized into a particle system carrying physical quantities for numerical simulation. After meshing the domain, the corresponding material particles were populated, totaling 18,975 particles. The simulation was then initiated upon completion of all parameter settings.

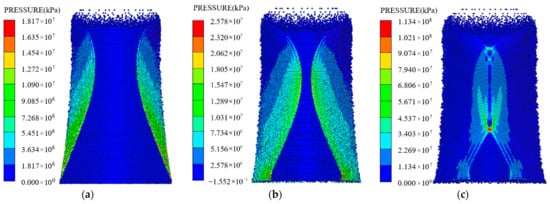

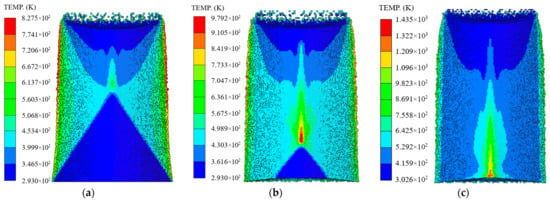

Figure 6 presents the pressure contour, illustrating the propagation of the shock wave through the raw material. Following detonation, energy travels downward along the grain. By 4 μs, the shock-wave front pressure reaches 25.85 GPa (1 GPa = 109 Pa −) and covers over 50% of the sample area, confirming the generation of a high-pressure field consistent with design expectations. The detonation also produces an instantaneous high-temperature field. As shown in the temperature contour (Figure 7), when the temperature exceeds 1373 K, the raw material begins to melt [27]. This melting phase transition leads to the formation of characteristic structures such as agglutinates and glass spherules. As the explosive continues to detonate downward, the temperature continues to rise. After 5 μs, the peak temperature reaches 1435.3 K, initiating local melting within the sample. The bulk temperature remains between 600 and 900 K, which promotes the formation of agglutinates and glass spherules through partial melting while preserving the overall mineral phase. This temperature distribution prevents excessive melting and helps maintain compositional similarity to lunar regolith.

Figure 6.

(a) Pressure contour map at 3 microseconds; (b) Pressure contour map at 4 microseconds. (c) Pressure contour map at 5 microseconds.

Figure 7.

(a) Temperature contour map at 3 microseconds; (b) Temperature contour map at 4 microseconds. (c) Temperature contour map at 5 microseconds.

4. Experimental Preparation and Characterization of Detonation-Modified Lunar Regolith Simulants

4.1. Test Preparation

To further verify the modification effect of detonation on lunar regolith simulants, this study designs a detonation experiment for validation. Existing lunar regolith simulants ensure similarity to natural lunar regolith in terms of chemical composition. Therefore, the Chinese Lunar Regolith Simulant (CLRS) series of national standard samples, developed by the Institute of Geochemistry, Chinese Academy of Sciences, were selected as the raw materials. CLRS-1 simulates low-titanium basaltic lunar regolith [28], and CLRS-2 simulates high-titanium basaltic lunar regolith [29], both of which are lunar mare simulants. Their main mineral components are plagioclase, olivine, and pyroxene, with a chemical composition similar to that of lunar regolith. The chemical composition of the samples is summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Lunar regolith simulants chemical composition (%) [28,29].

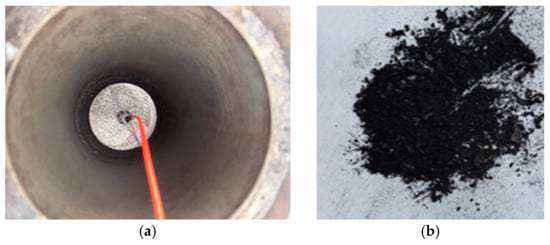

The high-energy explosives used in the experiments were RDX (Hexogen, C3H6N6O6) and JO-9 (a booster explosive with HMX as its primary component). To investigate how different assembly configuration affects the modification of simulant particles, four pyrotechnic setups were designed, as illustrated in Figure 8. RDX served as the lower-energy explosive, while the more powerful, military-grade JO-9 was employed for higher-energy inputs. Their performance parameters are summarized in Table 3. After assembling the explosives with the raw materials, a detonator and ignition wire were attached to complete the pyrotechnic assembly. The assembly was then placed inside a sealed detonation tank and initiated. Following the reaction, the system was allowed to cool prior to tank opening. The product collected from the bottom was sieved to remove large debris consisting primarily of metallic fragments from the tank wall and residual pyrotechnic materials, yielding the detonation-modified lunar regolith simulants with similar space weathering characteristics. This simulant was subsequently characterized in terms of morphology, chemical composition, and physical properties. A comparative analysis with lunar regolith was conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of the detonation-based modification method. The sealed detonation tank and sample collection process are shown in Figure 9.

Figure 8.

(a) End face shape constraint assembly method: the mass ratio of explosive to raw material was 5 g:1.2 g; (b) Bucket shaped strong constraint assembly method: the mass ratio of explosive to raw material was 4.5 g:14 g; (c) Bucket shaped weak constraint assembly method: the mass ratio of explosive to raw material was 4.5 g:14 g; (d) Four point detonation assembly method and top view: the mass ratio of explosive to raw material was 14 g:3.8 g. Configurations (a–c) employed RDX, while configuration (d) used JO-9 explosive.

Table 3.

Performance parameters of high explosive.

Figure 9.

(a) The sealed detonation tank; (b) Sample collection after detonation.

4.2. Particle Morphology Analysis

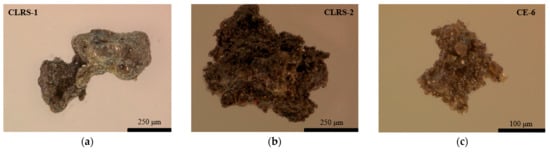

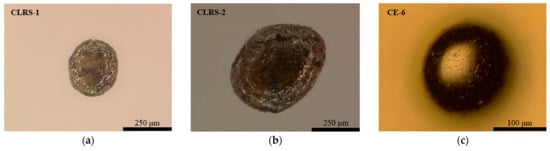

The morphology of the detonation-modified samples was examined using leica DVM6 digital microscope (Leica Microsystems GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany) and compared with the lunar regolith returned by Chang’e-6 mission. Prior to observation, the samples were cleaned with anhydrous ethanol to remove surface debris and contaminants. Chang’E-6 accomplished the first-ever sample return from the lunar far-side. The landing site (153.9776° W, 41.6251° S, −5273 m) is located in the mare basalt region of the northeastern South Pole–Aitken Basin (SPA), between the southern rim crest and the peak rim of the Apollo Basin [30]. The results indicate significant overall morphological changes, including a reduction in sharp edges and corners, an increase in surface-adhering material, the formation of micro-pits, a higher content of agglutinates, and a notable decrease in the proportion of fine particles. These changes are attributed to the instantaneous high temperature during detonation, which melts finer particles and promotes their adhesion onto larger grains, thereby altering the overall particle morphology.

The modified samples contain agglutinates (Figure 10) and glass spherules (Figure 11), both of which closely resemble those found in lunar regolith. Agglutinates, a common constituent of lunar regolith, form under high-velocity micrometeorite impacts. They exhibit irregular shapes, developed pore structures, and locally honeycomb-like textures, with particle sizes ranging from 100 to 500 μm. Their overall morphology aligns closely with observations from Chang’e-6 lunar regolith samples, though their abundance in the simulants remains relatively low. As another characteristic component, the glassy phase in the modified samples occurs almost entirely as spherules with other materials often attached to their surfaces, most of which are below 50 μm in diameter. Only a small fraction shows composite morphologies. Compared to Chang’e-6 returned samples, the glass spherules in the detonation-modified simulants have rougher surfaces and are rarely found as isolated particles—most adhere to the surfaces of other grains or agglutinates [9]. Furthermore, the energy input during detonation significantly influences the relative proportions of agglutinates and glass spherules. Lower energy inputs favor agglutinate formation, while higher inputs increase the content of glassy material. In subsequent experiments, the ratios of these two phases can therefore be adjusted by controlling the detonation energy.

Figure 10.

(a) Agglutinate in CLRS-1 lunar regolith simulants after modified; (b) Agglutinate in CLRS-2 lunar regolith simulants after modified. (c) Agglutinate in lunar regolith from Chang’e-6.

Figure 11.

(a) Glass spherules in CLRS-1 lunar regolith simulants after modified; (b) Glass spherules in CLRS-2 lunar regolith simulants after modified. (c) Glass spherules in lunar regolith from Chang’e-6.

4.3. Analysis of Thermal Characteristics

In addition to morphological analysis, this study also evaluated the thermal properties of a simulant prepared using Configuration A (Figure 8a). The specific heat capacity and thermal diffusivity of the samples before and after detonation modification were measured using the laser flash method and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC). The thermal conductivity was then derived accordingly. Thermal conductivity calculation equation:

In the equation, α is the thermal diffusion coefficient at a certain temperature, measured in mm2/s; Cp is the specific heat capacity at the corresponding temperature, measured in J/(g∙K); ρ is the density, measured in g/cm3.

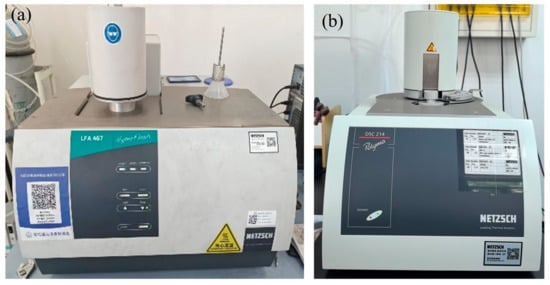

The test equipment is shown in Figure 12. Thermal diffusivity of the samples before and after modification was measured at low temperature (−173.15 K) and room temperature (298.15 K) using a laser flash analyzer (Figure 12a). The results presented in Table 4 represent average values based on three repeated tests. At low temperature, the thermal diffusivity of the modified sample decreased by approximately 40.7% to 0.067 mm2/s. At room temperature, it decreased by about 27% to 0.080 mm2/s. Using the specific heat capacity corresponding to each temperature, the thermal conductivity was calculated. At low temperature, the thermal conductivity of the modified sample decreased by approximately 50.4% to 0.0419 W/(m∙K). At room temperature, it decreased by about 41% to 0.0725 W/(m∙K). After high-energy detonation modification, the formation of complex, melted agglutinates and the development of weathering-like surface structures introduce significant interfacial thermal resistance, which alters the solid phase heat transfer path and leads to a marked reduction in thermal conductivity. The thermal conductivity of Lunar regolith is roughly two orders of magnitude lower in situ than under Earth’s atmospheric pressure [31]. According to measurements of Apollo 16 lunar samples, the thermal conductivity of lunar regolith at room temperature is approximately 0.04 W/(m·K) [18]. In comparison, the modified simulant exhibits thermal conductivity that is closer to this lunar reference value than to that of the unmodified material.

Figure 12.

(a) Thermal conductivity testing instrument: NETZSCH LFA 467 HyperFlash; (b) Specific heat capacity testing instrument: NETZSCH DSC 214 Polyma. Both are manufactured by NETZSCH-Gerätebau GmbH, Selb, Germany.

Table 4.

Thermal Conductivity of Lunar regolith simulants Before and After Modification.

It should be pointed out that due to the limited mass of modified lunar regolith simulants, thermal conductivity testing under high vacuum (under 10−2 Pa) conditions has not yet been conducted. Vacuum level is also an important factor affecting thermal conductivity. Therefore, the calculated thermal conductivity differs from that of lunar regolith measured under high-vacuum conditions. Nevertheless, the thermal conductivity of the detonation-modified simulant shows a clear convergence toward that of lunar regolith.

The carbon residues on sample surfaces, resulting from the negative oxygen balance of RDX and HMX, constitute only a minor fraction and are not the primary factor influencing thermal conductivity. As the results demonstrate, the significant reduction in thermal conductivity is mainly due to the formation of space-weathered microstructures (e.g., agglutinates and pores), which substantially alter solid-phase heat transfer pathways and introduce considerable interfacial thermal resistance. All samples were cleaned prior to morphological and thermal characterization. The cleaning procedure reduces the influence of surface carbon residues on sample testing, though it does not fully eliminate their effect. Further minimizing carbon interference remains an objective for process optimization.

5. Potential Applications of Lunar Regolith Simulants in Exploration and Research

The prepared lunar regolith simulants exhibit high similarity in weathering structure. The detonation-modified simulants contain key weathering features such as agglutinates and glass spherules, and their thermal conductivity is significantly reduced, providing a closer approximation to lunar regolith. When used in lunar regolith heating and melting experiments, these lunar regolith simulants can serve as more realistic materials, leading to more accurate experimental outcomes.

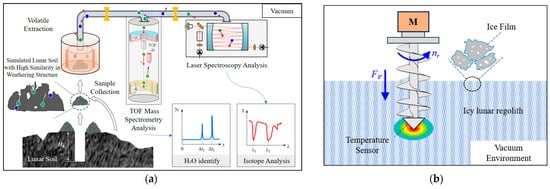

At the payload application level, this research facilitates the transition of lunar in situ resource utilization technology from experimental study to engineering practice. It provides both a material basis and theoretical support for China’s deep space exploration endeavors. For instance, the simulants can offer more realistic calibration materials for subsequent payload detection tasks. During the Chang’e-7 water-ice detection mission, sampling equipment may experience water loss upon contact with lunar regolith ice. To determine the in situ water-ice content, the amount of ice lost during sampling must be quantitatively calibrated. The modified simulants possess adsorption–desorption properties closer to those of lunar regolith, thereby supplying more authentic calibration substances and data for preparing lunar regolith ice simulants. Potential application scenarios for high-fidelity lunar regolith simulants are illustrated in Figure 13.

Figure 13.

High similarity simulation of lunar regolith application scenarios: (a) Ground simulation experiment of volatile matter heating extraction; (b) Ground simulation test of lunar regolith water ice drilling sampling.

At the scientific level, by simulating the core mechanisms of space weathering and reproducing the fragmentation–melting–agglutination behavior during lunar regolith formation, this study offers a new material basis for investigating lunar regolith genesis. Furthermore, through comparative analysis of unmodified simulants, detonation-modified simulants, and lunar regolith, the relationship between weathering structure and physical properties can be elucidated, helping to fill research gaps in this field.

6. Conclusions

Based on the formation mechanism of lunar regolith and the detonation mechanism, this study employs the coupled high-temperature, high-pressure, and high-impact loading generated by the detonation of high-energy explosives to modify raw materials. This approach thereby reproduces the fragmentation–melting–agglutination behavior that characterizes space weathering, enabling the preparation of lunar regolith simulants with high similarity in terms of space weathering characteristics. The main conclusions are as follows:

(1) The method of generating instantaneous high-temperature, high-pressure, and high-impact environment via high-energy explosives in a sealed container can effectively simulate the micrometeorite-dominated space weathering process, yielding simulants with weathering characteristics closely resembling those of lunar regolith.

(2) Detonation-modified samples exhibit two critical features also found in lunar regolith: agglutinates and glass spherules. The agglutinate morphology is similar to that observed in lunar regolith samples. The glass spherules show attached surface materials, and particle surfaces display pore-like fractured structures analogous to lunar regolith.

(3) These structures significantly alter solid phase heat transfer pathways, leading to a marked decrease in thermal diffusivity and thermal conductivity, closer to lunar regolith. It can serve as a more reliable material basis for future experiments on resource utilization and lunar construction.

This research is currently at the preliminary design and validation stage, employing gram-scale charges and confinement configurations. Scaling up toward potential engineering applications may profoundly affect energy-distribution uniformity, melting-agglomeration behavior, and ultimately the simulant’s structure and properties. Therefore, the next phase of this research will focus on systematically examining the effects of charge mass and configuration on the structure, thermal properties, and weathering characteristics of the simulant, to improve the performance and yield of the simulants.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.T., S.J. and Z.D.; methodology, J.T., A.Z. and Y.L. (Yu Li); software, A.Z.; validation, J.T., A.Z., S.J., Y.L. (Yang Li), Y.L. (Yu Li) and X.W.; formal analysis, A.Z. and Y.L. (Yu Li); investigation, A.Z. and Y.L. (Yu Li); resources, J.T., Y.L. (Yang Li), X.Z., and T.H.; data curation, J.T.; writing—original draft preparation, A.Z.; writing—review and editing, J.T., Y.L. (Yang Li), Y.Y. and X.W.; visualization, A.Z., Y.L. (Yu Li) and X.W.; supervision, J.T. and S.J.; project administration, J.T.; funding acquisition, J.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by The National Key R&D Program of China (2025YFF0510801), Natural Science Foundation of Heilongjiang Province of China (YQ2025E010), Open Fund of National Key Laboratory of Deep Space Exploration (NKDSEL2024003), The Chang’e-5 Lunar Scientific Research Sample (CE5C0200YJFM00303H), and The Chang’e-6 Lunar Scientific Research Sample (CE6C0300).

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Xiangrun Zhao was employed by the company Institute of Pyrotechnics Technology Xi’an North Qinghua Electromechanical Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Zheng, Y.; OYang, Z.; Wang, S.; Zou, Y. Physical and mechanical properties of lunar soil. Miner. Rocks 2004, 24, 14–19. [Google Scholar]

- He, X.; Xiao, L.; Huang, J.; He, Q.; Gao, R.; Yang, G. Lunar regolith simulants development and lunar regolith simulants CUG-1A. Geol. Sci. Technol. Inf. 2011, 30, 137–142. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Zou, M.; Jia, Y.; Chen, B.; Ma, W. Study on Lunar regolith simulants for Mechanical Tests of Lunar Rovers. Rock Soil Mech. 2008, 29, 1557–1561. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, M.; Li, L. Development of TJ-1 Lunar regolith simulants. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 2011, 33, 209–214. [Google Scholar]

- Heiken, G.H.; Vaniman, D.T.; French, B.M. Lunar Sourcebook: A User′s Guide to the Moon; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1991; pp. 285–356. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, L.P. Space Weathering of Lunar Rocks and Regolith Grains. In Proceedings of the Hayabusa 2013: Symposium of Solar System Materials, Sagamihara, Japan, 16–18 October 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cremers, C.J.; Hsia, H.S. Thermal conductivity of Apollo 16 lunar fines. Lunar Planet. Sci. Conf. 1974, 3, 2703–2708. [Google Scholar]

- Denevi, B.W.; Noble, S.K.; Christoffersen, R.; Thompson, M.S.; Glotch, T.D.; Blewett, D.T.; Garrick-Bethell, I.; Gillis-Davis, J.J.; Greenhagen, B.T.; Hendrix, A.R.; et al. Space weathering at the moon. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 2023, 89, 611–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Hu, H.; Yang, F.; Liu, J.; Zhou, Q.; Ren, X.; Liu, B.; Liu, D.; Zeng, X.; Zuo, W.; et al. Nature of the lunar far-side samples returned by the Chang’E-6 mission. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2024, 11, nwae328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corley, L.M.; Gillis-Davis, J.J.; Schultz, P.H. A comparison of kinetic impact and laser irradiation space weathering experiments. In Proceedings of the Lunar and Planetary Science XLVIII, The Woodlands, TX, USA, 20–24 March 2017; p. 1721. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Li, X.; Zhu, K.; Xu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Lei, D.; Luo, T.; Ling, Z.; Wang, G. In-Situ Resource Utilization on the Moon and Key Scientific and Technological Issues. Bull. Natl. Nat. Sci. Found. China 2022, 36, 907–908. [Google Scholar]

- Ruan, R.; Yang, W.; Zhang, D.; Tian, H.-C.; Zhao, Q.; Zou, Y.; Yu, B. A moderate-Ti lunar mare soil simulant: IGG-01. Acta Astronaut. 2024, 224, 148–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Hu, H.; Yang, M.F.; Pei, Z.-Y.; Zhou, Q.; Ren, X.; Liu, B.; Liu, D.; Zeng, X.; Zhang, G.; et al. Characteristics of the lunar samples returned by the Chang’E-5 mission. Natl. Sci. Rev. (Engl. Version) 2022, 9, nwab188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Shen, Z.; Dang, Z.; Zhuo, T. Simulation of Lunar Soil Research and Its Application in Lunar Exploration Engineering. Spacecr. Environ. Eng. 2014, 31, 241–247. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, F.; Li, Q.; Chen, Y.; Hu, S.; Yue, Z.-Y.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, H.; Yang, W.; Tian, H.-C.; Zhang, C.; et al. Lunar Evolution in Light of the Chang’e-5 Returned Samples. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 2024, 52, 159–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Sun, J.; Xiao, Q.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Cao, K.; Liu, Y.; He, Q.; Yang, H.; Chen, Q.; et al. Microtopographic Characteristics of Chang’e-5 Returned Lunar Regolith and Its Implications for Space Weathering. Earth Sci. 2022, 47, 4145–4160. [Google Scholar]

- Housley, R.M.; Cirlin, E.H.; Paton, N.E.; Goldberg, I.B. Solar wind and micrometeorite alteration of the lunar regolith. Lunar Planet. Sci. Conf. Proc. 1974, 3, 2623–2642. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, R.V.; Score, R.; Dardano, C.; Heiken, G. Handbook of Lunar Regolith; NASA: Washington, DC, USA, 1983.

- Giordano, D.; Russell, J.K.; Dingwell, D.B. Viscosity of magmatic liquids: A model. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2008, 271, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Kong, W.; Zuo, J.; Li, L.; Wu, B.; Tao, Z. Experimental and Numerical Analysis of Dynamic Action Evolution Mechanism of Explosion Shock Wave and Detonation Gas. J. China Coal Soc. 2024, 49, 248–260. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Ning, J.; Xu, X. Calculation of Reflection Pressure After Interaction Between Shock Wave and Typical Materials. Acta Armamentarii 2025, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Griffith, A.A. The Phenomena of Rupture and Flow in Solids. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 1920, A221, 163–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Li, C.; Li, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zhu, C.; Wen, Y.; Fa, W.; Li, X.; Liu, J.; Ouyang, Z. Vapor-deposited digenite in Chang’e-5 lunar regolith. Sci. Bull. (Engl. Version) 2023, 68, 723–729. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhang, B. Analysis of the Relationship between Specific Surface Area and Pore Structure of Shales. J. Hebei Univ. Eng. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2019, 36, 75–79. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, K.; Mi, S.; Sun, J. Numerical simulation analysis of jet formation in double-layer drug cover based on AUTODYN. In Proceedings of the 12th China CAE Engineering Analysis Technology Annual Conference Chinese Society of Mechanical Engineering, Changchun, China, 11–12 August 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.; Feng, D.; Guo, Z. Recent developments of SPH in modeling explosion and impact problems. In Proceedings of the III International Conference on Particle-Based Methods: Fundamentals and Applications (PARTICLES 2013), Stuttgart, Germany, 18–20 September 2013; pp. 428–435. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y.; Li, F.; Zhou, S.; Liu, L. Investigating the microscopic, mechanical, and thermal properties of vacuum-sintered BH-1 lunar regolith simulants for lunar in-situ construction. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 22, e04132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L. High Temperature Sintering and SLM Forming of CLRS-1 Simulated Lunar Soil and Characterization of Sample Properties. Master’s Thesis, Harbin Institute of Technology, Harbin, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T.; Tang, H.; Li, X.; Zhou, C.; Yu, W.; Mo, B.; Liu, J.; Zeng, X. Np-Fe 0 addition affects the microstructure and composition of the microwave-sintered lunar soil simulant CLRS-2. Adv. Space Res. 2024, 73, 945–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Zeng, X.; Ren, X.; Chen, W.; Gao, X.; Zuo, W.; Liu, B.; Zhang, Z.; Fu, Q.; Liu, J.; et al. Geological characteristics of Chang’E-6 landing area in micro-scale unveiled by new observation data. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 4219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pourakbar, M.; Zhao, Y.; Cortes, D.D.; Dai, S. Small-strain thermo-mechanical performance of lunar mare and highlands regolith simulants under Earth’s atmospheric pressure and in vacuum. Icarus 2025, 429, 116405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.