Abstract

In this paper, we present a transient-format time-continuous Galerkin finite element method for fully intrinsic geometrically exact beam equations that are energy-consistent. Within the grid of space and time, we derive governing equations for elements using the Galerkin method and the time finite element method, implement variable interpolation via Legendre functions, and establish an assembly process for space–time finite element equations. The key achievement is the realization of the free order variation of the program, which provides a basis for future research on adaptive algorithms. In particular, the variable order method reduces the quality requirements for the mesh. In regions with a higher degree of nonlinearity, it is easier to increase the variable order, and the result is smoother. Meanwhile, increasing the interpolation order effectively enhances computational accuracy. Introducing kinematical equations of rotation with Lagrange operators completely imposes the conservative loads on fully intrinsic equations. This means that loads in the inertial coordinate system, such as gravity, can also be iterated synchronously in the deformed coordinate system. Through a set of illustrative examples, our algorithm demonstrates effectiveness in addressing conservative loads, elastic coupling deformation, and dynamic response, demonstrating the ability to analyze elastically coupled dynamic problems pertaining to helicopter rotors.

1. Introduction

Many engineering components, such as helicopter rotor blades, can be represented as beams for which one dimension is larger than the other two. In aircraft design, beams are commonly used as the main load-bearing structures, and their dynamics have always been an important topic of study.

In recent years, the increasing complexity of rotor structures and analysis conditions has led to higher requirements for blade dynamics models, among which fully intrinsic geometrically exact beam theory [1] stands out, with its unique form of first-order nonlinear partial differential equations that are independent of displacement and rotation variables. Ghorashi [2] applied general nonlinear intrinsic equations of beams to solve the elastodynamic response of hingeless composite blades under the condition of accelerating speed and successfully analyzed the nonlinear response of an active airfoil blade and its influence on the steady-state load. Amoozgar [3] modeled the rotation dynamics of a morphing composite blade using fully intrinsic geometrically exact beam equations and solved them via the finite element method. The convergence results were in good agreement with the experimental results. In [4], modeling methods of fully intrinsic geometrically exact beams under different boundary conditions were explored and used for static equilibrium, steady-state motion, and linearized dynamic analyses. The results show that the fully intrinsic method is particularly suitable for blade dynamics analysis.

The derivation of the fully intrinsic form began with the study of geometrically exact beams, which first appeared in the work of Kirchhoff and Clebsch [5] in 1944. Subsequently, according to different solution variables, beam theories can be divided into three types: displacement-based theory [6], which reduces the complexity of the formula by using high-order truncation; mixed variational theory [7], which introduces generalized velocity and generalized strain as unknown variables; and fully intrinsic theory [8], which completely eliminates displacement and rotation variables. The concept of intrinsic theory was first introduced by Green and Laws [9] in 1966 in the process of studying elastic rods. In 1977, Hegemier and Nair [10] proposed a fully intrinsic elastic rod theory with large deformation and small strain, in which the governing equations were composed of load and velocity variables and were used to solve the steady-state motion of helicopter rotor blades. In 1990, Hodges [7] developed an exact intrinsic formulation that can be written in a simple matrix form with only second-degree nonlinearities, and which is ideally suited for the finite element method. The feasibility of using the finite element method to solve mixed-variable equations is verified in [11]. From the canonical form of the equations of motion, in 2003, Hodges [8] derived a set of generalized strain–velocity compatibility relations. From this, a complete set of energy-conserved fully intrinsic and geometrically accurate partial differential equations of beam dynamics can be obtained.

The fully intrinsic geometrically exact beam equation is a type of nonlinear time-domain-dependent partial differential equation that is usually solved by a discrete process of first space then time, and the partial differential equations are transformed into time-domain recursive equations. Since the finite difference method is a simple and convenient spatial discretization method, Patil and Hodges [12] applied the fully intrinsic model to the dynamic analysis of a highly flexible wing using a central difference scheme. This spatial discretization scheme was later used by Khouli [13] to analyze the hinged swept blade. Pezhman [14] analyzed the vibration characteristics of the pre-twisted beam using the spatial difference scheme discretization method and focused on observing the influence of the pre-twisted distribution on the stability of the beam. Mojtaba [15] simulated the foldable spiral structure in the same format, and this showed a computational advantage over commercial software. In 2011, Patil and Althoff [16] used the continuous Galerkin method to discretize the fully intrinsic equation in space and fitted the variables with Legendre polynomials. The results show that the Galerkin method can obtain more accurate solutions with fewer trial functions. In the same year, Patil and Hodges [17] proposed the concept of variable-order finite elements by changing the order of Legendre functions and which evaluated their accuracy, computational efficiency, and applicability to general problems. Their results showed that one can obtain approximately third-order, fifth-order, seventh-order, and ninth-order convergence for linear, quadratic, cubic, and quartic finite elements, and one can use higher-order finite elements for a better approximation of mode shapes. In recent years, many spatial solving formats with better efficiency and accuracy have been proposed, such as the Chebyshev collocation method [18], the GDQ method [19] and the neural network model [20]. However, these numerical algorithms always need to recurse gradually over time, often require time- and cost-intensive iterations, have cumulative errors, and depend heavily on the initial values.

The space–time finite element method is a high-precision and effective means of addressing the problem developing time partial differential equations. Its main feature is to treat the time domain as the space domain for unified discretization, forming an unstructured space–time grid that is consistent for any order of discretization. Higher-order methods can be naturally embedded in these applications, offering desirable features like high calculation accuracy and moderate calculation time in the field of nonlinear dynamics problems. In 2022, Devin [21] adopted the space–time finite element method, using the first-order partial differential equation in the state space as the dynamic control equation of a sandwich beam. By integrating the boundary conditions and initial conditions throughout the entire domain, the equation was transformed into a system of linear algebraic equations, and the transient response was solved. Through an improved integration scheme, Vikas [22] studied the influencing parameters of high-frequency component dissipation in the process of solving dynamic equations by the Galerkin time finite element method. Currently, there are relatively few time finite element methods available for solving fully intrinsic geometrically exact beams. In [8], Hodges adopted the central difference scheme to discretize the space and time of equations simultaneously. Chen Lidao [23] adopted a DQ-Pade method with high-order accuracy to construct a space–time finite element equation for a fully intrinsic model. In 2023, Chen Lidao and Xin Hu [24] established a space–time finite element steady-state method based on the Galerkin weighted residual method with Legendre functions, which has been successfully applied to non-conservative load issues. This discrete scheme was shown to be structurally simple and easy to assemble, but the study only compared the influence of linear and second-order schemes on the results.

Based on the periodic steady-state scheme, in this work, we develop a free variable-order transient general scheme capable of handling conservative loads. This algorithm can simultaneously solve the vibration deformation in the spread and rotation directions at any time while the rotor is rotating. It is simple to operate and easy to implement, and it provides a powerful analytic tool for the study of rotor dynamics, including but not limited to the vibration response of the rotor with a change in its attitude and the vibration reduction optimization of complex aerodynamic shape structures coupled with blades. Its characteristic of free order variation offers the possibility of developing adaptive and meshless algorithms. Additionally, within the existing framework, the coupling solution or joint simulation of CFD/CSD can be achieved by integrating the aerodynamic solution. The basic process of the Galerkin space–time continuous finite element method for the fully intrinsic geometrically exact beam is as follows: first, the space–time element control equation is obtained through the discretization of the global elements along the spanwise and azimuth directions of the blade. Then, the element equations are assembled according to certain laws to obtain the total algebraic matrix equation of the beam. Finally, this is solved by the Newton method, and the displacement and rotation are obtained by reverse calculation. In this study, discontinuity treatment of the blade structure, energy conservation of the equation, the initial value format, conservative load treatment, and the influence of variable order are also investigated, and a series of static deformation and dynamic response problems are solved to verify the effectiveness of the proposed algorithm.

2. Fully Intrinsic Beam Equations

Ignoring warping deformation in the profile, the fully intrinsic equations for the geometric exact beam theory can be expressed in a compact form as

where is the first partial derivative of space, is the first partial derivative of time, is the initial twist/curvature of the beam, , and and , respectively, represent the element distribution force and element distribution moment loaded on the beam such that the direction is perpendicular to the beam axis. , , , and , respectively, represent the force, moment, linear velocity, and angular velocity of the beam section at the location and time . , , , and , respectively, represent the force strain, moment strain, linear momentum, and angular momentum of the corresponding beam section. Note that all the intrinsic variables are expressed in the deformed base B as . is the cross-product operator, taking as an example:

The constitutive equations relate the momenta to the velocities and the strain measures to the sectional loads as

where the matrices , , and constitute the flexibility characteristics of the beam section, and the matrices , and , respectively, represent the linear density, mass eccentricity, and moment of inertia. Equations (1) and (3) constitute a complete set of differential equations for first-order partial derivatives in time and space.

For a hingeless beam with length L, the spatial boundary and periodic continuity conditions of the steady-state problem can be summarized as follows:

where and represent the load condition at the free end, and and are the velocity conditions at the root of the blade. Let represent the initial time state; thus, the initial value boundary conditions of the transient problem can be similarly summarized as

3. Galerkin Space–Time Finite Element Method

According to [19], a fully intrinsic equation naturally adapts to the Galerkin space–time continuous finite element method (STFEM). However, only the analysis of a low-order scheme is given, that is, there are only two formats, first order and second order, lacking a comparison and the full utilization of advantages of a high-order algorithm. In this study, we construct a variable-order scheme of the STFEM, allowing its free transformation from low-order to high-order.

The Galerkin method provides a systematic discretization framework for complex multi-field coupling problems that can automatically maintain physical conservation laws and often derive symmetric equations. This method transforms the problem of complex differential equations into a larger, sparse system of linear algebraic equations. In addition, the Galerkin method can explicitly handle the boundary conditions of equations, has ribbon storage, and is efficient. Even without element discretization and with variable interpolation discretization only, that is, taking a meshless approach, it can still reliably solve equations for simple beams and loads.

The finite element method has the ability to handle advanced aerodynamic shapes, non-uniform structural characteristics, and complex alternating loads in the external field. When combined with the Galerkin method, it can achieve high-fidelity dynamic simulation of helicopter blades.

3.1. Conservation Laws of Galerkin Space–Time Equations

For a hingeless rotor blade, consider the following weak form of all the equations (fully intrinsic equation, space boundary condition, and time boundary condition). Premultiply , , and by the Galerkin weighted method and integrate them in the spanwise and time domains,

Note that the constitutive equations are already satisfied. With the rules of tilde notation , simplify Equation (6) as

Integrating by parts in space,

By the constitutive laws, integrating by parts in time,

Here, add the kinetic energy and strain energy into the evidence, which leads to

The first term on the left side of the equation is the final energy, the second term is the initial kinetic energy, and the third term is the initial potential energy. The first term on the right side of the equation is the work performed by the distributed load, and the second term is the work performed by the concentrated load at both ends of the beam. The equations state that the change in energy of the beam is equal to the work performed on the beam. Thus, the above equations are energy balance equations. The above evidence is valid for every space–time element. When dealing with a periodic steady state problem, replace the initial time condition with the periodic continuous condition, without disrupting the conservation of the equation.

3.2. Discretization in the Space–Time Domain

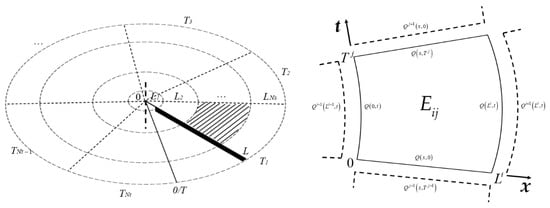

Discretize the integral domain of the above equation, as shown on the left in Figure 1. The rotating blade with length L is dispersed into Ns segments along the spanwise direction. For any motion duration, T, which is multiple of the rotation period for the steady-state format, is dispersed into Nt segments along the azimuth angle. Then, form a global space–time cell grid on the scale of . Equation (6) must be satisfied in each element. Simultaneously convert the boundary conditions into continuity between adjacent elements.

Figure 1.

Schema of the space–time finite element discrete grid.

Take the element Eij, which is ith (i = 1~Ns) in space and jth (j = 1~Nt) in time, shown on the right in Figure 1. The spatial length of this element is denoted as Li, and the temporal length is denoted as Tj, while 0 represents the start position or the initial time. The variables within the element are denoted as Qij(x,t) and substitute for the intrinsic variables , among which (x,t) are coordinates in the element. The lines around the element are shared with the four elements around time (Ei,j−1, Ei,j+1) and space (Ei−1,j, Ei+1,j), that is, the continuous variables should be continuous with the adjacent elements or meet the boundary conditions. For a homogeneous blade, the continuity condition can be summarized as follows:

The above continuity conditions are applicable to any element with concentrated mass and initial deformation; therefore, the space–time finite element equation is as follows:

Divide the above equation into four equations by the preceding multiplicative term:

Equations (13) and (14) are the dynamic equations of the element, and Equations (15) and (16) are the kinematic equations. When Equations (13)–(16) are both satisfied, Equation (12) is established.

3.3. Separation of Variables in Space and Time

As the dimensions of time and space are independent of each other, assume that the intrinsic variables can be written as a linear combination of the products of a series of trial functions:

where is the column vector of distinct polynomial weights, and , . The independent trial functions used are the shifted Legendre functions [25], that are orthogonal to the domain [0, 1] and fit the boundary and periodic conditions well. The polynomials can be iteratively derived as

Therefore, the derivatives of the variables can be expressed as the derivatives of the spatial or temporal interpolation polynomials, respectively. The continuity condition can be expressed as the continuity of the interpolating polynomial value at the ends (0 or 1) of the elements.

Let , , and , respectively, represent the weights of the corresponding variables , , and in any element,

According to Equation (3), , , , and can also be expressed as

Thus, Equation (11) can be written as

Taking Equation (13) as an example, substitute Equations (19)–(21) into the following formula:

Here, several subscripts (ab, kl, pq) are used to distinguish the order of polynomials, and each group of subscripts corresponds to a different variable. Within each group, one is of temporal interpolation order between 0~Rs, and the other is of spatial interpolation order between 0~Rt.

During processing of the premultiplication term, each equation must be satisfied by any , , and ; therefore, it is significant outside of the equations. To simplify the symbols, omit the subscripts of the elements i, j and the polynomial variables , . Then, the fully intrinsic Equations (13)–(16) can be transformed into an algebraic system about the weight coefficients:

It should be noted that the section characteristics G, K, I, R, Z, and T are generally piecewise linear functions related to the spread position and often cannot be obtained beyond the integral sign. If and only if it is a homogeneous beam can it be treated as a constant coefficient.

3.4. Assemble Element Algebraic Equations

Classify and organize the integrals in Equations (23)–(26) according to the number of coefficient variables; the following takes the first equation as an example. First, take one weight coefficient out of the integral:

Second, distinguish them based on whether there are variables in parentheses, whether there are variables outside parentheses, and whether the variables belong to the same unit, and express them in the form of multiplying rows and columns:

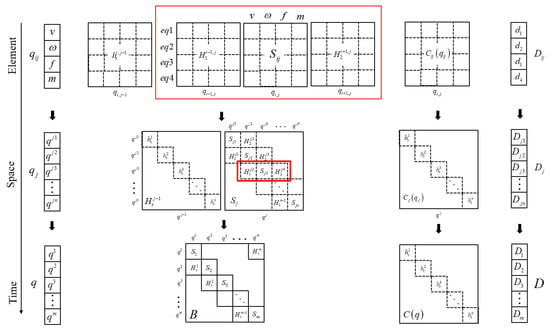

Let , , , , which are all the column vectors of the dimension. Finally, make the same arrangement for the remaining three equations, and arrange the coefficient row vectors together by column, as shown in Figure 2, the line of “Element”.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of element equation assembly process.

In addition, the terms without variables in the integral are classified as linear matrices ; the cross terms with variables in the integral are classified as nonlinear matrices ; the terms without variables outside the integral are classified as constant matrices ; and the variables outside the integral belong to adjacent elements , , and and are classified as continuity matrices that contain the spatial continuity matrices and and the time continuity matrices . Thus, the element equation can be summarized in the following form:

As shown in Figure 2, the system computing model of the structure is composed of all the space–time elements, and the structural characteristic matrix of the system is composed of the superposition of each element coefficient matrix. On the basis of obtaining the above element matrix equation, Equation (29), assemble the beam system equation according to the order of space first and then time as indicated by the arrow in Figure 2:

First, the equation variables are integrated: the jth time node variables are obtained by arranging the space–time element variables according to the spatial sequence of 1~Nt. Then, the system unknowns are obtained by arranging different time-node variables according to the time sequence of 1~Ns.

Then, the coefficient matrix of each element is assembled according to the arrangement logic of variables as follows:

- (1)

- Total stiffness matrix : the spatial continuity matrix , and the linear matrix are arranged side by side in the order of space formed as , then inserted into row and column to form the time-node matrix as shown by the red box in Figure 2. The element time continuity matrix is arranged diagonally in spatial order to form the time-node continuity matrix . The time correlation matrices and are arranged in order of time, forming , then inserted into row and column to form the total stiffness matrix.

- (2)

- Total nonlinear matrix : the element nonlinear matrix is arranged diagonally in space order, formed as , and then arranged diagonally in time order.

Finally, the constant matrix is assembled according to the assembly logic of the variables: first, the element constant matrix is placed in row to form the time-constant matrix , and then it is placed in row to form the total constant matrix, which includes external loads and boundary conditions.

Therefore, the assembled algebraic equations can be written as follows:

It should be noted that the time continuity matrix at the corner of the stiffness matrix in the initial value scheme is zero, and the initial value condition will be contained in the constant matrix. When the number of elements is 1, the whole domain is taken as an element, eliminating the process of discretization and assembly; however, the variables in the domain must be consistent, that is, the profile characteristics are continuous, and in the periodic scheme, the matrix is implicit in the matrix .

The Newton–Raphson method is used to solve the nonlinear system equations with the Jacobian matrix, which can be accurately expressed. The following is a simple demonstration of this process, supposing that Equation (26) is

Then, the Jacobian matrix is

The iterative initial value is taken by dividing the blade stiffness matrix with the constant matrix, i.e., . According to the result of each step, the Jacobian matrix is updated, and the variables are iterated until convergence. The result is substituted back into Equation (17) to obtain the space and time distribution functions of the intrinsic variables.

After obtaining the global distribution of the intrinsic variables and rotation matrix, it remains difficult to imagine the displacement and rotation angle of the beam, so it is necessary to convert the results to the configuration space. For this purpose, the displacement can be reversed via the following displacement–strain and displacement–velocity equations:

Here, is the displacement in the undeformed coordinate system and is the linear velocity of the undeformed blade. Similarly, the theta of rotation can be reversed by rotation kinematical equations, which are

Here, is the angular velocity of the undeformed blade, and is a 3 × 3-dimensional tensor matrix, which represents the rotation of the section from the undeformed coordinate to the deformed coordinate with . The initial value conditions of displacement and rotation are

To represent the angle in the undeformed coordinate system, according to the specific expression of the coordinate transformation matrix, which is non-singular, the following is performed:

3.5. Process of Space–Time Finite Element Method

The basic process of the space–time finite element method (STFEM) for fully intrinsic geometrically exact beam equations can be summarized as follows:

- The Galerkin space–time equation for a hingeless blade is shown in Equation (6). Discretize the space along the beam and discretize the time along the azimuth angle in each movement period. Then, obtain the global discrete space–time grid, shown in Figure 1;

- Establish the continuous relationships between units, as shown in Equation (11). Thus the space–time finite element equation can be obtained via the weighted method as Equation (12). Divide this into four equations according to the weight functions, like Equations (13)–(16).

- With the Legendre functions in Equation (18), approximate the variables to a linear combination of a set of space–time polynomials, as in Equations (19) and (20). Then, with only the variables that are the weight coefficients of the polynomials, transform the derivative terms and continuity into the derivative terms and continuity of the polynomials, as in Equation (21). Thus the finite element algebraic equations are obtained as Equations (23)–(26).

- Remove one weight coefficient from the integral, classify the integral functions according to the number of variables like Equations (27) and (28), and arrange the four equations in column order. This yields the element matrix equation, Equation (29).

- Assemble the above element matrix equation according to a certain law, as shown in Figure 2. Then, the global discrete algebraic equation, Equation (30), of the beam is obtained, whose coefficient matrix only includes the stiffness, nonlinear, and constant matrices.

- Obtain the linear initial value via , and also the Jacobian matrix, as shown in Equations (31) and (32). The Newton method is used to solve the nonlinear equation, and the global distribution of the intrinsic values is arranged.

- Given the initial displacement and rotation angle conditions, as in Equation (35), obtain the displacement distribution in the entire domain by Equation (33) and the transformation matrix distribution by Equation (34). Then, obtain the theta distribution by Equation (36).

3.6. Treatment of Blade Structure Discontinuity

It should be noted that in the actual design process, there is a discontinuity in the blade structure. Specifically, the section structural characteristics are discontinuous, which leads to load discontinuity. According to the constitutive law, the fact that the strain is continuous in the spatial direction does not mean that the load is uniformly continuous.

where and represent the left and right parameters of the discontinuous section, and [S] is the profile stiffness matrix. Therefore, the spatial continuity of the load at the discontinuity section can be established by the section flexibility matrix [R] as

When the left and right characteristics of the section are consistent, Equation (37) naturally degenerates into Equation (3).

3.7. Handling of Conservative Loads

When the rotor is in motion, the main external force is the aerodynamic load following deformation, which completely fits to the coordinate system of the fully intrinsic model. The blade is also affected by gravity; although the value is small compared with the aerodynamic force, in many cases, it cannot be ignored.

In Ref. [26], the conservative load is coupled with the control equation through the variation parameter of the gravity vector, and its specific form is consistent with Equation (34); however, the influence of its geometric shape is not considered. In Ref. [27], a coupling scheme of geometrically exact equations combined with a kinematical equation was proposed, using Lagrange multipliers so that all variables could vary independently in the calculus. In this study, we introduce conservative loads through the coupling of rotation kinematical equations. Thus, by coupling Equation (30) with Equation (1) using Lagrange multipliers, the following can be obtained:

Here, and are the conservative force and moment. Equation (39) can also be regarded as a constraint problem, with the constraint condition that the differential equation of the coordinate transformation matrix is always 0 throughout the entire domain. The Lagrange multipliers can always be identified via the Lagrange multiplier method. However, it is hard to obtain the specific form of the multiplier directly and effectively because of the coupling between C and intrinsic variables.

The basic form of Lagrange multipliers depends on the properties of the constraint equation. Here, the multiplier is a three-dimensional column vector function whose value varies with time and space and can be adopted for discretization via the finite element method or Equation (17).

From the perspective of the variational principle, Lagrange multipliers are used to introduce constraints into energy functionals. The differential equation of C describes the geometric relationship of deformation. After introducing the multiplier, it contributes to the internal torque in the principle of virtual work; therefore, the Lagrange multiplier can be understood as the distribution function of the bending moment and the twisting moment. From the perspective of the dimensions of differential equations, C is dimensionless, and k and κ represent the curvature before and after deformation. Substituting the torque unit into the Lagrange multiplier can make the unit of the integral consistent with the energy functional.

Since can be independently and arbitrarily varied, its specific form does not affect the process of the method proposed, enabling analysis of conservative loads. At the same time, the introduction of the C matrix will nearly double the variables, increasing the time cost. There is an urgent need for a higher-order algorithm with a high upper limit to reduce the computational cost. Similarly, modifications should be made to the load boundary conditions with conservative tip force and tip moment :

3.8. Applicability and Limitations

Due to the introduction of profile characteristics in the constitutive relation of the fully intrinsic geometric exact beam model, the method proposed in this paper has a unique advantage when dealing with anisotropic complex coupled beams and can be used directly as a dynamic solver for the aeroelastic coupling of helicopter rotors. It can also be applied to dynamic models, such as wind turbine blades, that consider the influence of self-weight. In addition, its free variable-order property serves as the foundation for adaptive algorithms, and the space–time finite element format enables it to capture or trace back a to certain period when solving periodic problems.

Although the formula derived in this paper is applicable to any order interpolation, in the iterative stage of the nonlinear component C(q), not using explicitly expressed matrix operations will greatly slow down the iteration speed, causing the operation time of the element matrix to expand in a square form due to the increase in order, making it less efficient than low-order multi-element operations. If explicit operations are adopted, a large amount of preparatory work is required to write the necessary algebraic matrix, and the maximum scale of the matrix is limited, lacking sufficient flexibility. Finding a suitable time–cost control method is a key task for future studies.

The method proposed in this paper also has some deficiencies in the handling of boundary conditions. Although the application of hinge-free or bearingless hubs has increased, many rotors still use hinged or universal hinge types. Determining how to apply the method proposed in this paper to such boundary conditions, as well as the handling of multi-body continuity conditions, will be the focus of future research.

4. Numerical Results

Four cases are presented to verify the effectiveness of the algorithm presented in this paper regarding the influence of a higher-order scheme and the ability to solve large deformation problems under conservative loading. First, we apply a concentrated tip moment with different orders or elements. Second, a non-conservative tip force and conservative tip force are applied on the cantilever beam. Third, Minguet beam experiments are conducted to verify the algorithm’s effectiveness under conservative loading with common structural coupling. Finally, the dynamic response of a rotating or non-rotating beam proves the validity of the initial value scheme.

4.1. Large Deformation Simulation of Bending Moment on Elastic Beam Tip

The first case is a benchmark problem for the geometrically nonlinear analysis of beams [28]. A flapping moment is applied to the tip of an elastic beam clamped at the root. The parameter of the beam is L = 20 ft, EI2 = 9000 lb-ft2. Each point on the beam is located on the arc with the curvature ; its exact solution can be expressed as

Under tip bending, only the bending moment exists at each point of the fixed beam, and the value is equal to the tip bending moment. This means that the variables are only constants and that the Legendre interpolation order is not sensitive to the problem and is only relevant to the algorithm error. The displacement is obtained by the approximate solution of the differential equation, the error of which is closely related to the deformation degree and mesh density.

Table 1 lists the tip position r3 under different tip bending moments with one element, and Table 2 lists the tip position r3 under different numbers of elements with tip bending moments of 2500 lb-ft2. All spatial elements adopt ninth-order interpolation. Through comparison, it is obvious that with an increase in the deformation degree, the precision decreases. Increasing the mesh number can improve the accuracy of the result.

Table 1.

Tip position r3 of 9th-order 1 element scheme vs. tip bending moments.

Table 2.

Tip position r3 of 2nd- and 9th-order schemes vs. element numbers under 2500 lb-ft2.

Table 2 compares errors between the interpolation function orders with the same number of elements. We can observe that as the element number increases, the two schemes tend to unify the solution, but when the number of units is less than 10, the error of the higher-order scheme is significantly smaller. Furthermore, the ‘/’ means that the 2nd-order 1-unit cannot make the result converge.

In Ref. [29], which used the 20-element RCAS model, the magnitude of error was 6.00 × 10−4 when the tip bending moment was 500 lb-ft2, which is far less than the calculation accuracy of a single element, while the magnitude of error was 1.98 × 10−4 when the tip bending moment was 2500 lb-ft2, which can be achieved with only three elements.

4.2. Static Deflections of Cantilever with Conservative or Non-Conservative Load

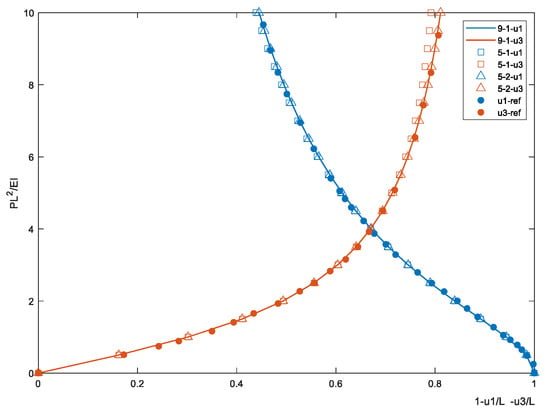

Case 2 is the static deformation of a fixed beam under a dynamic force [30,31]. The dynamic load is divided into two types: the non-conservative load and the conservative force at the free end of the blade. The so-called non-conservative force is the direction of the force that is always perpendicular to the beam axis, while the conservative force remains in the original direction. The basic parameters of the beam are as follows: length, L = 100 cm; moment of inertia, I22 = 1.666667 cm4; material Young’s modulus, E = 2.1 × 107 N/cm2.

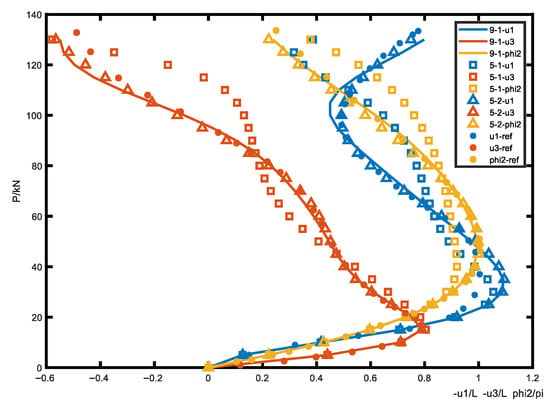

The displacement–force curve of the free end of the beam under different non-conservative tip forces is shown in Figure 3, in which an obvious nonlinear, large deformation of the beam can be seen. The 5th-order 1-unit, 5th-order 2-unit and 9th-order 1-unit simulation results are compared with the calculated data in Ref. [24], which was obtained with 10 elements and 30 unknowns. It can be noted that both the 5th-order 2-element and 9th-order 1-element results are basically consistent with the reference results except that the 5th-order 1-element result deviates strongly under large deformations.

Figure 3.

Tip displacement diagram of cantilever under non-conservative tip force.

With a tip load of about 30 kN, u1 deviates from the reference. According to trend analysis, at this time, the beam is transitioning from linear to nonlinear deformation, the tip is gradually moving upward, and the angle growth trend is gradually slowing down. The tip should still be extending negatively, that is, the tip has passed the origin along the X-axis, and -u1/L is greater than 1. In addition, comparing the 5th-order 2-element and 9th-order 1-element results, it can be seen that when the beam is under large deformation, increasing the number of elements brings the result closer to the reference result than increasing the order. This is because the displacement nonlinearity is more prominent than the load nonlinearity, and the mesh encryption can be more effective in fitting.

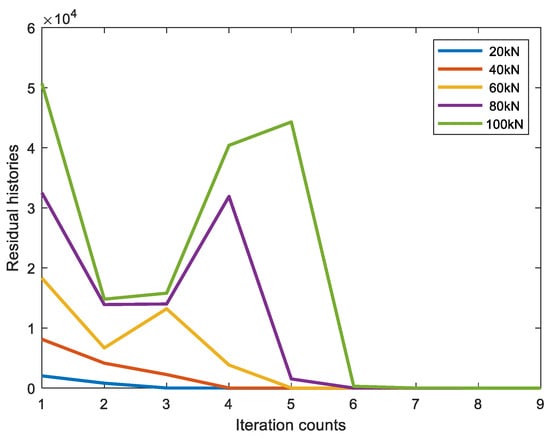

Figure 4 shows the residual history under different blade tip forces, which is calculated using a 5-order 2-element scheme. The figure clearly shows that the calculation results basically converge at the sixth iteration step and even converge at the fourth step when the load is less than 40 kN. As the tip force of the beam increases, the iteration counts do not increase by much. In addition, when the nonlinear component is large, the residual will fluctuate significantly due to the change in the iteration direction during the solution process. So, as the nonlinear components increase, the residual fluctuation also increases.

Figure 4.

Residual histories of 5th-order 2-element under different tip force.

Table 3 compares the residuals, convergence counts, and initial value sensitivity under different schemes when the tip force of the beam is 60 kN. Residuals are expressed in the form of norms, and the initial value sensitivity is represented by the norm of the increment in the first iteration. Taking a residual less than 1 × 10−5 as the standard, all different schemes achieve stable results at the seventh step. Moreover, the residual and initial value sensitivity are affected by the number of elements but not the interpolation order. As the number of elements increases, the initial residuals and the initial value sensitivity increase simultaneously. The increase in units enhances the simulation ability of the linear model for the nonlinear part, and the linear results constantly approach the reference results. That the sensitivity variable varies with the number of elements proves the compatibility of the linear initial value for different grids. Under the same number of elements, as long as the order required for the solution is reached, the other higher-order variables are basically 0 and are unaffected.

Table 3.

The residual, iteration counts, and sensitivity of initial value under 60 kN.

The displacement–force curve of the free end of the beam under different conservative tip loads is shown in Figure 5. It can be seen from the figure that both the 9th-order 1-unit and the 5th-order 2-unit results are basically consistent with the reference results. Although there is a certain gap between u3 of the 5th-order 1-unit result and the compared data, the time error is not obvious when PL2/EI < 6.

Figure 5.

Tip displacement diagram of cantilever under conservative tip force.

4.3. Static Behavior of Composite Blades Under Large Deflections

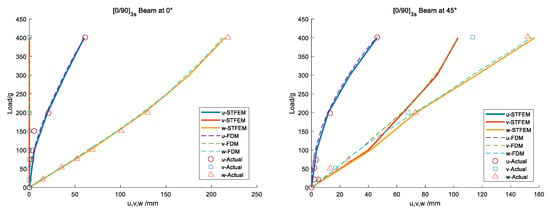

Composite materials are the primary materials used in helicopter rotor blades, leading to structural couplings such as extension–twisting and bending–twisting. These couplings can be used to improve the dynamic and aero-elastic performance of helicopter rotors. Case 3 is the large deformation of composite blade under static loading [32,33]. Here, we examine the performance of the proposed algorithm for a structurally coupled composite blade under large load conditions.

During the experiment, an aluminum chuck was used to fix the composite beam on the rotating platform to control the installation angle. The blade exposed outside the chuck was 550 mm long and 30 mm wide. The strain gauge was attached at 50 mm outside the chuck, and the displacement was observed at 300 mm and 500 mm. When the installation angle was 0°, the blade was placed horizontally. The STFEM with the 9-order 1-element format was used, compared with the finite difference method (FDM) in Refs. [34,35], which discretizes length into 56 nodes. In the experiments, the beam’s own weight was included, and all displacements were measured from initial position.

The first specimen has a [0/90]3s setup, without any coupling to serve as a reference, as shown in Figure 6. The displacement w was almost linear, and the displacement u was negative in practice. When the installation angle was 0°, the displacement v was 0, and the tip deformation was about 40% of its length under the maximum load. When the installation angle was turned to 45°, due to weak rigidity in the normal plane, the deformation tended to be the initial v, and w was basically the same. The calculation results of the method presented in this paper are basically consistent with those in the literature, which aligns with natural law and proves the reliability of the algorithm in the case without coupling.

Figure 6.

Tip displacements for a [0/90]3s beam with different tip loads.

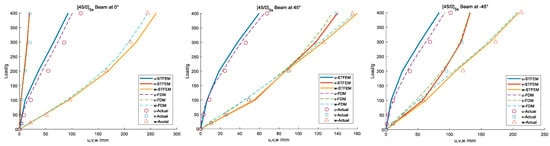

The next test was [45/0]3s to illustrate the effect of bending–twisting coupling, as shown in Figure 7. Due to the existence of flexural and torsional coupling, even at a 0° installation angle, there is a certain coupling deformation v. At 45°, v and w are basically the same, but they are completely different at −45°. In general, although the algorithm presented in this paper has some shortcomings in calculating u, its results better approximate the coupling change of v and w.

Figure 7.

Tip displacements for a [45/0]3s beam with different tip loads.

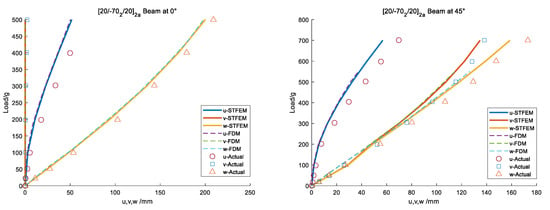

A [20/−70/−70/20]2a setup was used to illustrate the effect of extension–twisting, as shown in Figure 8. Compared with the uncoupled setup, the torsional stiffness was significantly enhanced. The results show that although there is a certain gap between the results of the proposed algorithm and the experimental data, it is completely consistent with the results of the FDM.

Figure 8.

Tip displacements for a [20/−70/−70/20]2a beam with different tip loads.

4.4. Dynamic Response of Cantilever Beam

Two cases of dynamic response [36] are examined for hingeless boundary conditions with nonrotating or rotating beams to simulate in the time domain of helicopter blades. The first case involves a nonrotating beam with vertically oriented tip dynamic forces, F3 = 10sin(20t). The second is a rotating beam under a transversal tip force, F2 = 10sin(20t), with a rotating speed of 70 rad/s. The material properties of this beam are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Material properties of beam.

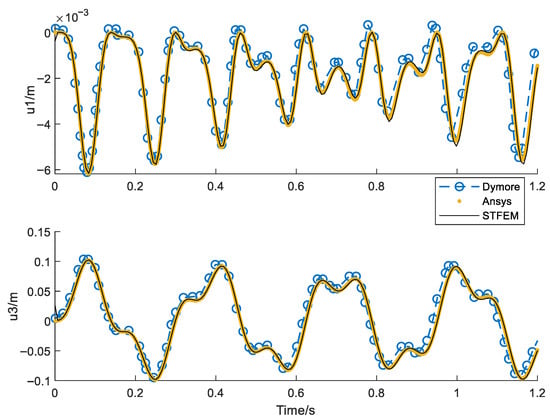

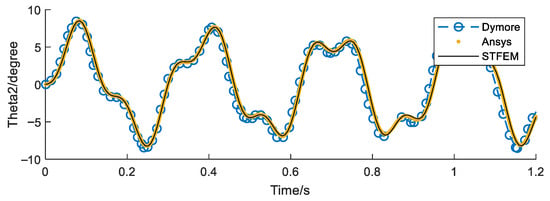

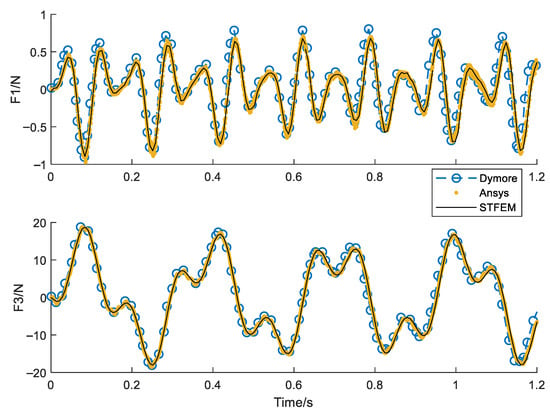

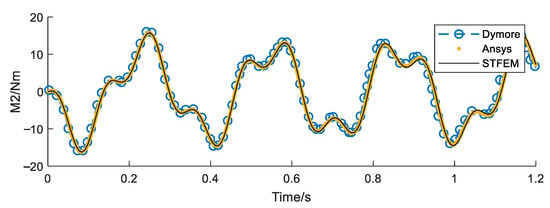

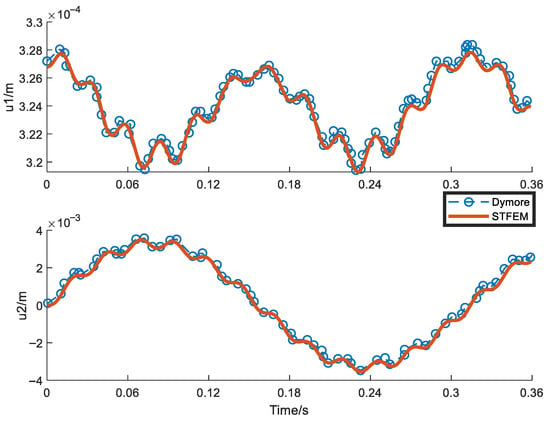

Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11 and Figure 12 show the time history curve of the tip displacement, tip rotation, root force, and root bending moment of a non-rotating cantilever beam under a given dynamic load F3 = 10sin(20t). The algorithm in this paper (STFEM) adopts a 5 × 5 cell, 5 × 5 order space–time format and computes in a step of 0.3 s. The calculation takes four steps, totaling 1.2 s. Compared with the Dymore (Bauchau, O. A., GT, USA) program, the waveform is basically the same, though there is a certain time delay with the development. On the whole, the results calculated in this study are completely consistent with those of Ansys (PA, USA), which proves the accuracy and reliability of the proposed method.

Figure 9.

Tip displacement (m) history with non-rotation for tip load F3 = 10sin(20t).

Figure 10.

Tip rotation (degree) history with non-rotation for tip load F3 = 10sin(20t).

Figure 11.

Root force (N) history with non-rotation for tip load F3 = 10sin(20t).

Figure 12.

Root moment (Nm) history with non-rotation for tip load F3 = 10sin(20t).

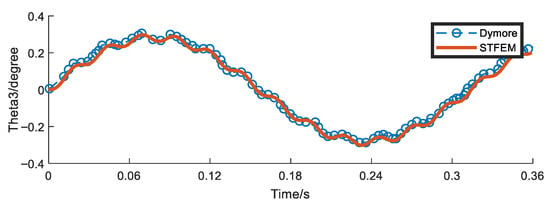

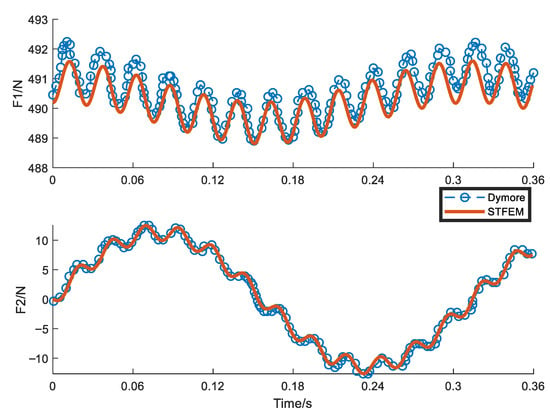

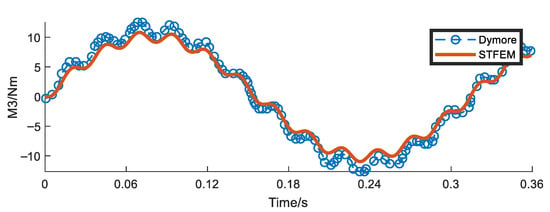

Figure 13, Figure 14, Figure 15 and Figure 16 show the time history curves of the tip displacement, tip rotation, and root bending moment of a rotating clamped beam under a given tip dynamic load, F2 = 10sin(20t). The format used is the same as above, the time step is 0.045 s, and the total time for eight steps is 0.36 s. According to the results, each peak and valley position was clearly captured. Although the deviation in the pendulum torque is slightly larger than that of the other terms, overall, the result is consistent with the results achieved using the simulation code Dymore, which verifies the feasibility of the proposed algorithm in the aerodynamic analysis of blades.

Figure 13.

Tip displacement (m) history with 70 rad/s rotating for tip load F2 = 10sin(20t).

Figure 14.

Tip rotation (degree) history with 70 rad/s rotating for tip load F2 = 10sin(20t).

Figure 15.

Root force (N) history with 70 rad/s rotating for tip load F2 = 10sin(20t).

Figure 16.

Root moment (Nm) history with 70 rad/s rotating for tip load F2 = 10sin(20t).

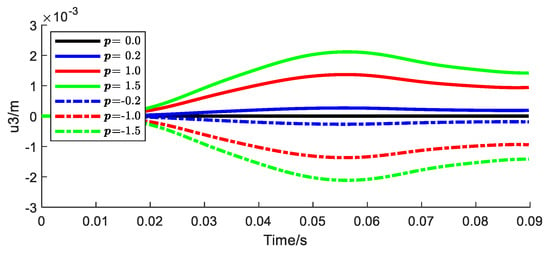

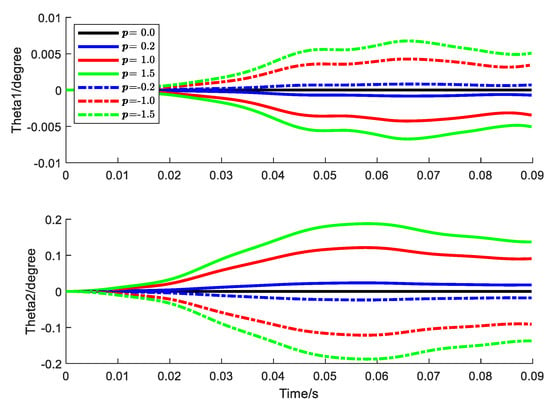

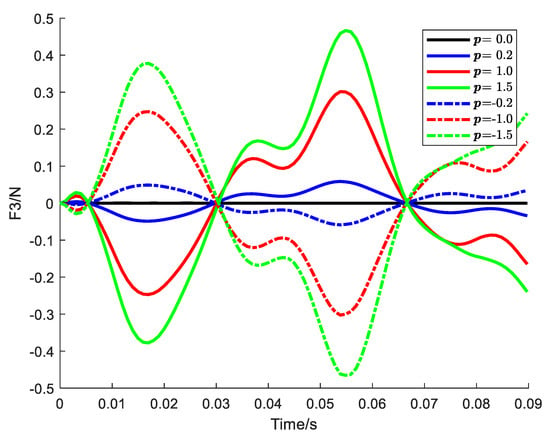

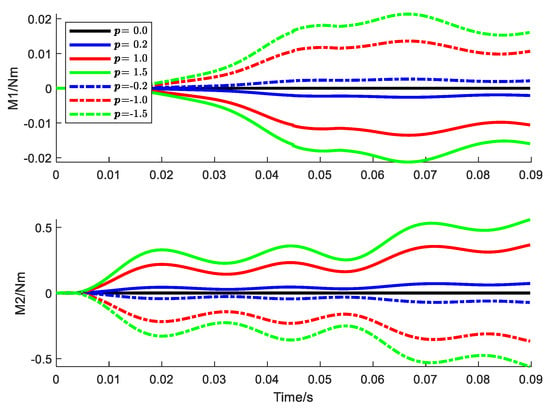

Figure 17, Figure 18, Figure 19 and Figure 20 show the displacement and load variation of a rotating beam in the non-pendulum direction after introducing bending–bending coupling under the action of a conserved simple harmonic force at the tip. The difference from Figure 13, Figure 14, Figure 15 and Figure 16 is that in the stiffness matrix, the flap–lag coupling stiffness is no longer 0 and is numerically equal to a certain proportion of the flap stiffness, which is represented by p.

Figure 17.

Tip displacement (m) history with bending–bending coupling.

Figure 18.

Tip rotation (degree) history with bending–bending coupling.

Figure 19.

Root force (N) history with bending–bending coupling.

Figure 20.

Root moment (Nm) history with bending–bending coupling.

It can be clearly observed from the figure that the introduction of bending–bending coupling will cause the pendulum mode to respond in the direction of the flap. Furthermore, the structural responses brought about by positive and negative elastic coupling are of opposite signs but equal values. Combining Figure 13 and Figure 17, we can imagine that the movement trajectory of the beam tip is presented as an ellipsoid.

Specifically, positive coupling causes the beam to flap upward when it lags forward while generating a pitch-down moment, that is, a negative torsion angle, at the same time. On the contrary, negative coupling will cause the beam to flap down during the forward lag and generate a pitch-up moment. Therefore, incorporating the elastic coupling of the profile can be used to enhance the stability of the angle of attack of the rotor blade. Then, from the numerical values in the figure, even if the coupling stiffness is greater than the swing stiffness, the resulting torsional change is very small. A 0.3° lag angle can only bring about a 0.005° change in the torsional angle. If the lag angle is 15°, the corresponding change in the torsion angle is only 0.25°.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, a space–time continuous finite element method for solving the fully intrinsic equations of a geometrically exact beam is established. The processes of space–time discretization, the establishment of the element equation, the discretization of variables, and the assembly of equations, as well as the solutions, are described in detail. This space–time finite element scheme offers energy conservation and variable order features that have the potential of an adaptive algorithm. This paper also provides solutions to common discontinuity, conservative load, and initial-value problems. The results show that this algorithm has good precision, stable convergence, and the ability to analyze blade coupling. By increasing the interpolation order of variables, the calculation accuracy is improved effectively, and the minimum element number requirement is significantly reduced such that it can even be developed into a meshless algorithm. In future studies, aerodynamic equations can be incorporated into the proposed method to achieve aero-elastic adjoint solutions; the method can be adapted as a high-precision dynamics solver; or the loose coupling method can be used to analyze the aero-elastic response of the rotor. The simultaneous solution of rotor dynamics problems via the time finite element method can avoid the accuracy issue resulting from the time step. Through integration, the changes in aerodynamic loads can be effectively captured, especially when loads change suddenly. The transient response results are also continuous and smooth, which is also more conducive to analyzing blade state at any moment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.H., L.C. and Y.L.; methodology, X.H. and L.C.; validation, X.H. and Y.L.; investigation, X.H.; data curation, X.H.; writing—original draft preparation, X.H. and Y.L.; writing—review and editing, X.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Hodges, D.H. Nonlinear Composite Beam Theory; AIAA: Reston, VA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ghorashi, M.; Nitzsche, F. Nonlinear dynamic response of an accelerating composite rotor blade using perturbations. J. Mech. Mater. Struct. 2009, 4, 693–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoozgar, M.R.; Shaw, A.D.; Zhang, J.; Friswell, M.I. Composite Blade Twist Modification by Using a Moving Mass and Stiffness Tailoring. AIAA J. 2019, 57, 4218–4225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotoudeh, Z.; Hodges, D.H. Modeling Beams with Various Boundary Conditions Using Fully Intrinsic Equations. J. Appl. Mech. 2011, 78, 31010-1–31010-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, A.E.H. Mathematical Theory of Elasticity, 4th ed.; Dover Publications: New York, NY, USA, 1944. [Google Scholar]

- Bauchau, O.A.; Kang, N.K. A Multibody Formulation for Helicopter Structural Dynamic Analysis. J. Am. Helicopter Soc. 1993, 38, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, D.H. A Mixed Variational Formulation Based on Exact Intrinsic Equations for Dynamics of Moving Beams. Int. J. Solids Struct. 1990, 26, 1253–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, D.H. Geometrically Exact, Intrinsic Theory for Dynamics of Curved and Twisted Anisotropic Beams. AIAA J. 2003, 41, 1131–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, A.E.; Laws, N. A General Theory of Rods. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. 1966, 293, 145–155. [Google Scholar]

- Hegemier, G.A.; Nair, S. A Nonlinear Dynamical Theory for Heterogeneous, Anisotropic, Elasticrods. AIAA J. 1977, 15, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, D.H.; Shang, X.; Carlos, C. Finite Element Solution of Nonlinear Intrinsic Equations for Curved Composite Beams. J. Am. Helicopter Soc. 1996, 41, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, M.J.; Hodges, D.H. Flight Dynamics of Highly Flexible Flying Wings. J. Aircr. 2006, 43, 1790–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khouli, F.; Afagh, F.F.; Langlois, R.G. Application of the First Order Generalized-α Method to the Solution of an Intrinsic Geometrically Exact Model of Rotor Blade Systems. J. Comput. Nonlinear Dyn. 2009, 4, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardanpour, P.; Izadpanahi, E.; Rastkar, S.; Fazelzadeh, S.A.; Hodges, D.H. Geometrically exact, fully intrinsic analysis of pre-twisted beams under distributed follower forces. AIAA J. 2018, 56, 836–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshtaghzadeh, M.; Izadpanahi, E.; Mardanpour, P. Stability analysis of an origami helical antenna using geometrically exact fully intrinsic nonlinear composite beam theory. Eng. Struct. 2021, 234, 111894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, M.J.; Althoff, M. Energy-consistent, Galerkin approach for the nonlinear dynamics of beams using intrinsic equations. J. Vib. Control 2011, 17, 1748–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, M.J.; Hodges, D.H. Variable-order finite elements for nonlinear, fully intrinsic beam equations. J. Mech. Mater. Struct. 2011, 6, 479–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Masjedi, P.K.; Maheri, A.; Weaver, P.M. Large deflection of functionally graded porous beams based on a geometrically exact theory with a fully intrinsic formulation. Appl. Math. Model. 2019, 76, 938–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoozgar, M.R.; Shahverdi, H. Analysis of Nonlinear Fully Intrinsic Equations of Geometrically Exact Beams Using Generalized Differential Quadrature Method. Acta Mech. 2016, 227, 1265–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Yang, X.; Deng, X.; Li, L. A varying-gain recurrent neural-network with super exponential convergence rate for solving nonlinear time-varying systems. Neurocomputing 2019, 351, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, D.J.; Batra, R.C. First failure load of sandwich beams under transient loading using a space–time coupled finite element method. Thin-Walled Struct. 2022, 173, 108960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.; Fujisawa, K.; Murakami, A.; Sasakawa, S. A methodology to control numerical dissipation characteristics of velocity based time discontinuous Galerkin space-time finite element method. Int. J. Numer. Methods Eng. 2022, 123, 5517–5545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Liu, Y. Differential Quadrature Method for Fully Intrinsic Equations of Geometrically Exact Beams. Aerospace 2022, 9, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Hu, X.; Liu, Y. Space-Time Finite Element Method for Fully Intrinsic Equations of Geometrically Exact Beam. Aerospace 2023, 10, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramowitz, M.; Stegun, I.A. (Eds.) Handbook of Mathematical Functions with Formulas, Graphs, and Mathematical Tables; US Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 1948; Volume 55. [Google Scholar]

- Masjedi, P.K.; Jangravi, S.; Reali, A. Isogeometric collocation for locking-free large deflection analysis of geometrically exact beams with intrinsic formulation. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2025, 446, 118282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Yu, W. Geometrically nonlinear analysis of composite beams using Wiener-Milenković parameters. J. Renew. Sustain. Energy 2017, 9, 033306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, A.S.; Ormiston, R.A. An Examination of Selected Problems in Rotor Blade Structural Mechanics and Dynamics. J. Am. Helicopter Soc. 2006, 51, 104–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hodges, D.H.; Atilgan, A.R.; Fulton, M.V.; Rehfield, L.W. Free-Vibration Analysis of Composite Beams. J. Am. Helicopter Soc. 1991, 36, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyris, J.H.; Symeonidis, S. Nonlinear finite element analysis of elastic systems under nonconservative loading-natural formulation. part I. Quasistatic problems. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 1981, 26, 75–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondoh, K.; Atluri, S.N. Large-deformation, elasto-plastic analysis of frames under nonconservative loading, using explicitly derived tangent stiffnesses based on assumed stresses. Comput. Mech. 1987, 2, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minguet, P.J. Static and Dynamic Behavior of Composite Helicopter Rotor Blades Under Large Deflections; Massachusetts Institute of Technology: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Minguet, P.J.; Dugundji, J. Experiments and analysis for composite blades under large deflections Part I: Static behavior. AIAA J. 1990, 28, 1573–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowell, E.H.; Traybar, J.J. An Experimental Study of the Nonlinear Stiffness of a Rotor Blade Undergoing Flap, Lag and Twist Deformations; NASA: Washington, DC, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Dowell, E.H.; Traybar, J.J.; Hodges, D.H. An experimental-theoretical correlation study of non-linear bending and torsion deformations of a cantilever beam. J. Sound Vib. 1977, 50, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T. Structural Dynamics Modeling of Helicopter Blades for Computational Aeroelasticity. Ph.D. Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).