Abstract

Deep space exploration missions face technical challenges such as long-distance communication delays and high-precision autonomous positioning. Traditional ground-based telemetry and control as well as inertial navigation schemes struggle to meet mission requirements in the complex environment of deep space. As a vision-based autonomous navigation technology, image-based navigation enables spacecraft to obtain real-time images of the target celestial body surface through a variety of onboard remote sensing devices, and it achieves high-precision positioning using stable terrain features, demonstrating good autonomy and adaptability. Craters, due to their stable geometry and wide distribution, serve as one of the most important terrain features in deep space image-based navigation and have been widely adopted in practical missions. This paper systematically reviews the research progress of deep space image-based navigation technology, with a focus on the main sources of remote sensing data and a comprehensive summary of its typical applications in lunar, Martian, and asteroid exploration missions. Focusing on key technologies in image-based navigation, this paper analyzes core methods such as surface feature detection, including the accurate identification and localization of craters as critical terrain features in deep space exploration. On this basis, the paper further discusses possible future directions of image-based navigation technology in response to key challenges such as the scarcity of remote sensing data, limited computing resources, and environmental noise in deep space, including the intelligent evolution of image navigation systems, enhanced perception robustness in complex environments, hardware evolution of autonomous navigation systems, and cross-mission adaptability and multi-body generalization, providing a reference for subsequent research and engineering practice.

1. Introduction

With the continuous advancement of human capabilities in space exploration, deep space exploration has gradually become a major focus in the aerospace field worldwide. Since the United States and the former Soviet Union launched lunar exploration programs in 1958, more than one hundred deep space exploration missions have been conducted worldwide, targeting celestial bodies such as the Moon, Mars, asteroids, Mercury and Venus. However, deep space exploration missions not only face challenges such as long-duration travel and complex orbit adjustments but must also address difficulties such as extreme environments and remote control delays [1]. Achieving efficient and precise navigation is therefore a key technological challenge for deep space missions [2]. Traditional deep space navigation methods, such as ground-based remote sensing and inertial navigation, have proven successful in short-range or near-Earth missions. However, in deep space environments, increasing distance from Earth leads to signal delays and insufficient navigation accuracy, which gradually become bottlenecks that limit the success of deep space missions [3]. Therefore, image-based navigation technology, as a vision-based autonomous positioning and navigation approach, has gradually become a research hotspot in the field of deep space exploration.

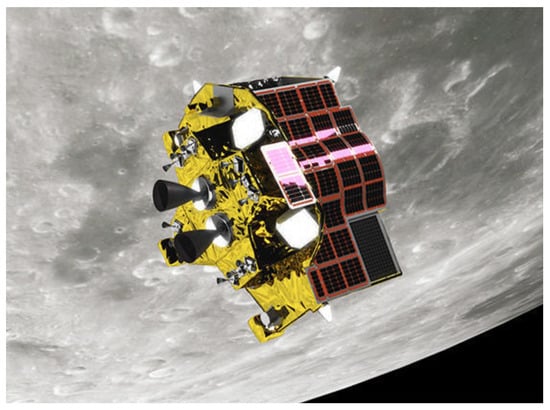

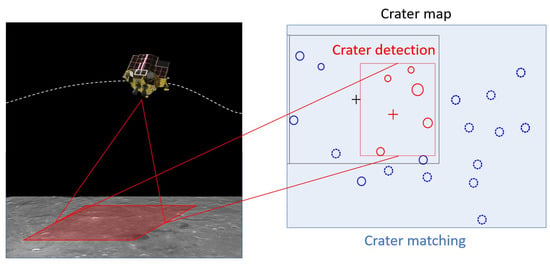

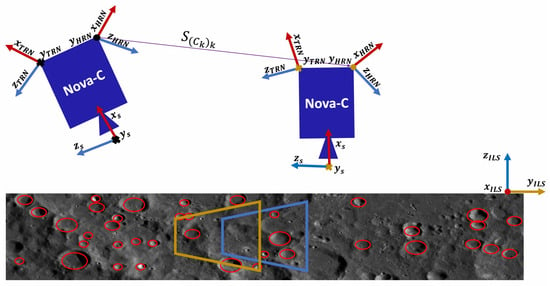

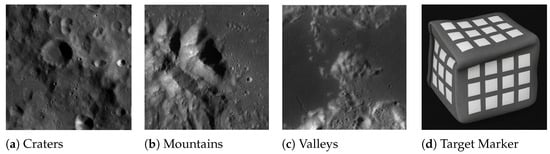

Image-based navigation enables spacecraft to obtain real-time images of the target celestial body through sensors onboard and to perform autonomous position and attitude calculation by integrating surface feature extraction, image matching, and attitude estimation [4]. Craters, as common terrain features in deep space exploration, are important targets that cannot be ignored in image-based navigation technology [5]. Due to their stable geometric shape and wide distribution, craters are frequently used as landmark features in deep space image navigation and have been applied in typical missions such as NEAR Shoemaker and SLIM. Compared to traditional ground-based control and inertial navigation methods, image-based navigation demonstrates greater autonomy, precision, and adaptability in deep space missions. On the one hand, it can achieve autonomous positioning and guidance in communication-constrained environments, reducing the reliance on ground commands; on the other hand, it can achieve high-precision pose estimation during critical phases such as descent by relying on real-time high-resolution images obtained in close proximity to the target surface, which enable effective surface feature matching. In addition, it exhibits greater robustness than traditional methods when facing complex terrain and extreme lighting conditions, making it suitable for real-time navigation requirements in diverse targets such as lunar polar regions and asteroids.

Although image-based navigation technology has achieved good application results in multiple deep space exploration missions, it still faces many technical challenges in practical use. Remote sensing image data in deep space exploration missions are often difficult to obtain, have limited coverage, and show uneven resolution. In particular, for small or unknown celestial bodies, there are bottlenecks such as a scarcity of effective visual features and a lack of annotated samples [6]. However, the complex and variable deep space environment imposes higher demands on the robustness of image navigation systems. Factors such as drastic lighting changes, image noise, significant viewpoint variation, and large-scale terrain variation can all reduce the accuracy of feature extraction and matching, thus affecting overall navigation performance. Furthermore, due to limited computing resources on spacecraft platforms, how we might achieve efficient and real-time image processing and state estimation while ensuring navigation accuracy has become a key issue that deep space image navigation technology urgently needs to address. In recent years, with the rapid development of deep learning, self-supervised learning, multimodal perception fusion, and intelligent decision-making algorithms, image navigation systems are gradually evolving toward high precision, high robustness, adaptability, and intelligence. However, their application in complex deep space mission scenarios still faces many scientific problems and engineering challenges that need to be resolved.

In view of the above context, this paper presents a systematic review of deep space image-based navigation technology. The first review covers the main sources of remote sensing image data in deep space exploration missions, typical application examples, and the challenges of deep space image navigation. Then, it systematically summarizes the key technical framework of image-based navigation, including surface feature extraction and how craters, as critical terrain features in deep space exploration, can be accurately identified and located using image navigation technology. Finally, the paper looks forward to the development trends and potential research directions of future deep space image navigation systems, providing references and insights for the design and optimization of high-precision autonomous navigation systems in subsequent deep space exploration missions.

4. Discussion and Future Directions

With deep space exploration missions expanding toward increasingly distant celestial bodies, the demand for advanced image-based navigation technologies is becoming more urgent. Deep space probes must operate autonomously in extreme environments to perform complex tasks such as localization, obstacle avoidance, and path planning. As such, the development of deep space image navigation technologies is expected to emphasize greater autonomy, intelligence, real-time performance, and accuracy. Future research and development can be broadly categorized into the following directions.

4.1. Intelligent Evolution of Image Navigation Systems

The rapid advancement of artificial intelligence, particularly deep learning, has significantly accelerated progress in deep space image navigation. Traditional image processing and feature matching methods exhibit limitations when faced with complex environmental conditions such as varying illumination, perspectives, and resolutions. In contrast, deep learning algorithms can automatically learn and extract complex features from large-scale data, improving the accuracy of surface feature extraction and adapting to dynamic planetary environments.

Considering the long operational cycles and sparse landmark databases typical of deep space missions, image navigation systems urgently require onboard self-learning and incremental mapping capabilities. By integrating multistage data sources (such as orbital remote sensing, close-range imaging, and descent images) and incorporating weakly supervised or self-supervised learning, the system can dynamically update feature representations and map structures. This alleviates issues related to the drift of landmark appearance and model degradation.

Furthermore, integrating graph optimization and feature relocalization enables incremental expansion of landmark databases while maintaining structural consistency, thereby enhancing the long-term stability and adaptability of the navigation system in unstructured and non-cooperative environments.

In addition to perception-driven deep learning methods, reinforcement learning (RL) and model-free approaches have recently emerged as promising directions for intelligent navigation. Unlike deep learning, which primarily enhances feature perception and environment representation, RL focuses on sequential decision making and adaptive control under uncertainty. Recent image-based deep reinforcement meta-learning further closes the loop from vision to control. For example, Q-learning and policy gradient algorithms have been applied to optimize planetary landing trajectories, hazard avoidance, and resource-constrained maneuver planning, demonstrating the ability to adaptively refine policies through interaction with simulated environments [140,141]. Moreover, model-free RL strategies have shown potential for terrain-relative navigation in lunar and Martian scenarios, where robustness against unmodeled dynamics is critical [142,143]. In addition, meta-RL policies exploit internal memory to adapt online to distribution shifts in gravity, mass properties, or illumination without explicit full-state re-estimation, with training commonly leveraging photorealistic rendering over LRO-derived DTMs to mitigate sim-to-real gaps [4,144].

Future intelligent navigation systems are therefore likely to benefit from a hybrid paradigm, in which deep learning-based vision systems provide robust perception and mapping, while RL contributes to adaptive planning and real-time decision making. This integration can improve both the accuracy of environmental understanding and the adaptability of spacecraft behavior, ultimately advancing the autonomy and resilience of deep space navigation.

4.2. Enhanced Robustness in Complex Environments

In deep space missions, image-based navigation systems operate under extremely challenging imaging conditions, such as strong illumination contrasts, shadow occlusion, low-albedo terrain, and interference from dust or plumes. These factors directly affect the stability of surface feature extraction and the reliability of feature matching, which become particularly critical during descent and landing phases. In the IM-2 mission, for example, long shadows caused by the low solar elevation angle severely interfered with crater feature matching and ultimately led to localization errors. Such cases illustrate that robustness issues arise not only from external environmental factors but also from whether the algorithms themselves can remain reliable under diverse and dynamic conditions.

Recent research has made progress in enhancing robustness. Low-light enhancement, HDR compression, and illumination-invariant feature descriptors have extended the operational range of visual sensors, and semantic-aided recognition and deep learning-based keypoint detection have demonstrated greater resilience under weak texture or partial occlusion. Meanwhile, self-supervised and cross-modal learning approaches provide representations less sensitive to environmental variability. Together, these methods lay an important foundation for stable feature detection, matching, and localization in deep space environments.

From our perspective, robustness should not be regarded as an auxiliary performance indicator, but rather as a core requirement that permeates the entire process of feature extraction, feature matching, and localization. Future navigation systems should adopt a layered and adaptive framework; lightweight visual–inertial fusion can maintain continuous navigation under nominal conditions, while more advanced enhancement or cross-modal modules can be dynamically activated when the confidence of features or matching declines, thereby ensuring stability and accuracy in critical mission phases. At the same time, the evaluation of robustness should not rely solely on average error but should incorporate safety-related metrics such as recovery time after visual degradation, whether pose or position uncertainty exceeds thresholds during descent, and the magnitude of accumulated drift under dynamic disturbances.

In summary, robustness in complex environments is not an isolated requirement but an integral part of the core chain of image-based navigation. By organically combining improvements across feature extraction, matching, and localization, and by introducing adaptive mechanisms together with risk-oriented evaluation criteria, future deep space navigation systems will be able to achieve stable performance in increasingly complex and unpredictable environments.

4.3. Hardware Evolution for Autonomous Navigation Systems

To efficiently run complex image navigation algorithms on resource-constrained space platforms, the hardware system must balance performance, power consumption, and integration. Future hardware will trend toward high-performance, low-power computing platforms, such as RISC-V-based aerospace processors, space-grade GPUs, and FPGA/ASIC accelerators. Onboard AI chips will become critical enablers for intelligent navigation, including neural network inference chips (e.g., TPU-like architectures) and space-grade AI SoCs.

These advances will enable image processing, path planning, and decision making directly on the spacecraft, reducing reliance on ground control, and improving response efficiency. In terms of system architecture, highly integrated and modular designs will become the norm. This includes unified layouts of cameras, computing units, and storage and communication modules, which improve the reliability of the system and the adaptability of the mission.

In practice, however, the adoption of advanced hardware faces several constraints. Radiation hardening and long-term reliability often lag behind commercial devices by one or two technology generations, meaning that “state-of-the-art” space processors may not match terrestrial performance. Moreover, higher computational density inevitably increases thermal load and complicates spacecraft-level power budgeting. Therefore, a balanced design may rely on a heterogeneous computing paradigm: lightweight, radiation-hardened CPUs for baseline autonomy and mission safety complemented by reconfigurable accelerators (FPGA/ASIC) that can be selectively activated for high-demand vision tasks. From a system engineering perspective, modularity should also extend to fault detection, isolation, and recovery (FDIR), ensuring that the failure of an AI accelerator does not compromise the entire GNC chain. We believe that the true innovation will not only lie in faster chips but in co-designing algorithms with hardware constraints, e.g., pruning and quantizing neural networks for in-orbit deployment or developing reinforcement learning policies that can be executed within strict timing guarantees.

4.4. Cross-Mission Adaptability and Multi-Body Generalization

The high diversity of deep space missions demands that image navigation systems possess strong adaptability across celestial bodies. Currently, most systems are highly mission-specific and optimized for a single planetary environment, which limits their reuse in subsequent missions. This lack of transferability is largely due to domain gaps in surface appearance, illumination conditions, and sensor models, as well as the scarcity of annotated in situ data.

Recent algorithmic advances point toward several promising solutions. Transfer learning and domain adaptation techniques allow models trained on one planetary dataset to be fine-tuned for another, while meta-learning frameworks provide the ability to quickly adapt navigation policies with limited new data. Self-supervised and contrastive representation learning approaches are also emerging as effective ways to extract features that are invariant across terrains, enabling cross-body generalization without heavy reliance on labeled samples. Furthermore, multitask joint optimization—where localization, mapping, and hazard detection are trained in a shared representation space—can improve robustness and consistency when switching tasks during different mission phases.

In our view, achieving cross-mission adaptability requires more than algorithmic transfer; it demands a systematic design that combines pretraining on large-scale simulated datasets with continual on-orbit adaptation. One practical strategy is a two-stage pipeline: a universal backbone model pretrained on multi-body imagery (lunar, Martian, asteroid) followed by lightweight adapters that specialize the features to mission-specific conditions. Another critical aspect is uncertainty estimation: cross-domain models must signal when their predictions are unreliable, allowing the navigation system to hand over control to fallback sensors or inertial baselines. Finally, to ensure true generalization, evaluation metrics should move beyond single-mission accuracy and include cross-body validation, e.g., training on lunar datasets while testing on Martian analogs. We believe that future progress will depend on integrating transfer learning with robust uncertainty-aware decision-making, enabling spacecraft to operate reliably in environments that have not been explicitly encountered during training.

5. Conclusions

With ongoing breakthroughs in AI algorithms, onboard hardware, computing architectures, and multisource perception technologies, deep space image navigation is advancing toward higher levels of intelligence, efficiency, and precision. Future systems will go beyond precise localization to integrate multimodal data fusion, dynamic path optimization, and real-time obstacle avoidance. These capabilities will allow probes to navigate autonomously and reliably for extended durations in complex and dynamic deep space environments.

As mission complexity and technical demands continue to increase, deep space image navigation systems will undergo further optimization, evolving into more flexible, reliable, and globally adaptable technologies. This will be a key enabler of the continued success of deep space exploration missions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.L. and T.L.; methodology, X.L. and T.L.; software, X.L.; validation, T.L., B.H. and C.Z.; formal analysis, X.L.; investigation, X.L.; resources, T.L.; data curation, X.L.; writing—original draft preparation, X.L.; writing—review and editing, T.L. and C.Z.; visualization, X.L.; supervision, T.L.; project administration, T.L.; funding acquisition, L.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 52275083. The APC was funded by the same foundation.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DOM | Digital Orthophoto Map |

| DEM | Digital Elevation Model |

| DIM | Digital Image Map |

| LOLA | Lunar Orbiter Laser Altimeter |

| LROC | Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera |

| OHRC | Orbiter High-Resolution Camera |

| SAR | Synthetic Aperture Radar |

| NavCam | Navigation Camera |

| MDIS | Mercury Dual-Imaging System |

| MLA | Mercury Laser Altimeter |

| NFT | Natural Feature Tracking System |

| EKF | Extended Kalman Filter |

| LVS | Landing Vision System |

| IMU | Inertial Measurement Unit |

| TRN | Terrain-Relative Navigation |

| ELVIS | Enhanced Landing Vision System |

| MRL | Map-Relative Localization |

| VO | Visual Odometry |

| PnP | Perspective-n-Point |

| DPOS | Distributed Position and Orientation System |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| RF | Random Forest |

| DT | Decision Tree |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| SAM | Segment Anything Model |

References

- Zhang, Y.; Li, P.; Quan, J.; Li, L.; Zhang, G.; Zhou, D. Progress, challenges, and prospects of soft robotics for space applications. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2023, 5, 2200071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turan, E.; Speretta, S.; Gill, E. Autonomous navigation for deep space small satellites: Scientific and technological advances. Acta Astronaut. 2022, 193, 56–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, J.H.; Wang, S. China’s Future Missions for Deep Space Exploration and Exoplanet Space Survey by 2030. Chin. J. Space Sci. 2020, 40, 729–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scorsoglio, A.; D’Ambrosio, A.; Ghilardi, L.; Gaudet, B.; Curti, F.; Furfaro, R. Image-based deep reinforcement meta-learning for autonomous lunar landing. J. Spacecr. Rocket. 2022, 59, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li., S.; Lu, R.; Zhang, L.; Peng, Y. Image processing algorithms for deep-space autonomous optical navigation. J. Navig. 2013, 66, 605–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzese, V.; Topputo, F. Celestial bodies far-range detection with deep-space CubeSats. Sensors 2023, 23, 4544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nozette, S.; Rustan, P.; Pleasance, L.P.; Kordas, J.F.; Lewis, I.T.; Park, H.S.; Priest, R.E.; Horan, D.M.; Regeon, P.; Lichtenberg, C.L.; et al. The Clementine mission to the Moon: Scientific overview. Science 1994, 266, 1835–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcewen, A.S.; Robinson, M.S. Mapping of the Moon by Clementine. Adv. Space Res. 1997, 19, 1523–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.E.; Zuber, M.T.; Neumann, G.A.; Lemoine, F.G. Topography of the Moon from the Clementine lidar. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 1997, 102, 1591–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaddis, L.; Isbell, C.; Staid, M.; Eliason, E.; Lee, E.M.; Weller, L.; Sucharski, T.; Lucey, P.; Blewett, D.; Hinrichs, J.; et al. The Clementine NIR Global Lunar Mosaic. NASA Planetary Data System (PDS) Dataset. PDS. 2007. Available online: https://pds-imaging.jpl.nasa.gov/ (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Racca, G.D.; Marini, A.; Stagnaro, L.; Van Dooren, J.; Di Napoli, L.; Foing, B.H.; Lumb, R.; Volp, J.; Brinkmann, J.; Grünagel, R.; et al. SMART-1 mission description and development status. Planet. Space Sci. 2002, 50, 1323–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholten, F.; Oberst, J.; Matz, K.D.; Roatsch, T.; Wählisch, M.; Speyerer, E.J.; Robinson, M.S. GLD100: The near-global lunar 100 m raster DTM from LROC WAC stereo image data. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 2012, 117, E00H14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speyerer, E.J.; Robinson, M.S.; Denevi, B.W.; Lroc, S.T. Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera global morphological map of the Moon. In Proceedings of the 42nd Annual Lunar and Planetary Science Conference, The Woodlands, TX, USA, 7–11 March 2011; No. 1608. p. 2387. [Google Scholar]

- Barker, M.K.; Mazarico, E.; Neumann, G.A.; Zuber, M.T.; Haruyama, J.; Smith, D.E. A new lunar digital elevation model from the Lunar Orbiter Laser Altimeter and SELENE Terrain Camera. Icarus 2016, 273, 346–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haruyama, J.; Ohtake, M.; Matsunaga, T.; Morota, T.; Honda, C.; Yokota, Y.; Ogawa, Y.; Lism, W.G. Selene (Kaguya) terrain camera observation results of nominal mission period. In Proceedings of the 40th Annual Lunar and Planetary Science Conference, The Woodlands, TX, USA, 23–27 March 2009; p. 1553. [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury, A.R.; Saxena, M.; Kumar, A.; Joshi, S.R.; Dagar, A.; Mittal, M.; Kirkire, S.; Desai, J.; Shah, D.; Karelia, J.C.; et al. Orbiter high resolution camera onboard Chandrayaan-2 orbiter. Curr. Sci. 2020, 118, 560–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Suresh, K.; Prashar, A.K.; Iyer, K.V.; Suhail, A.; Verma, S.; Islam, B.; Lalwani, H.K.; Srinivasan, T.P. High resolution DEM generation from Chandrayaan-2 orbiter high resolution camera images. 52nd Lunar Planet. Sci. Conf. 2021, 2548, 1396. [Google Scholar]

- Dagar, A.K.; Rajasekhar, R.P.; Nagori, R. Analysis of boulders population around a young crater using very high resolution image of Orbiter High Resolution Camera (OHRC) on board Chandrayaan-2 mission. Icarus 2022, 386, 115168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelgrift, J.Y.; Nelson, D.S.; Adam, C.D.; Molina, G.; Hansen, M.; Hollister, A. In-flight calibration of the Intuitive Machines IM-1 optical navigation imagers. In Proceedings of the 4th Space Imaging Workshop (SIW 2024), Laurel, MD, USA, 7–9 October 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Shoer, J.; Mosher, T.; Mccaa, T.; Kwong, J.; Ringelberg, J.; Murrow, D. LunIR: A CubeSat spacecraft performing advanced infrared imaging of the lunar surface. In Proceedings of the 70th International Astronautical Congress (IAC 2019), 26th IAA Symposium on Small Satellite Missions (B4), Small Spacecraft for Deep-Space Exploration (8), Washington, DC, USA, 21–25 October 2019. Paper ID: IAC-19-B4.8.6x53460. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Liu, J.; Ren, X.; Mou, L.; Zou, Y.; Zhang, H.; Lü, C.; Liu, J.; Zuo, W.; Su, Y.; et al. The global image of the Moon obtained by the Chang’E-1: Data processing and lunar cartography. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2010, 53, 1091–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Ren, X.; Liu, J.; Zou, X.; Mu, L.; Wang, J.; Shu, R.; Zou, Y.; Zhang, H.; Lü, C.; et al. Laser altimetry data of Chang’E-1 and the global lunar DEM model. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2010, 53, 1582–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Liu, J.; Ren, X.; Yan, W.; Zuo, W.; Mu, L.; Zhang, H.; Su, Y.; Wen, W.; Tan, X.; et al. Lunar global high-precision terrain reconstruction based on Chang’E-2 stereo images. Geomat. Inf. Sci. Wuhan Univ. 2018, 43, 485–495. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Ren, X.; Tan, X.; Li, C. Lunar image data preprocessing and quality evaluation of CCD stereo camera on Chang’E-2. Geomat. Inf. Sci. Wuhan Univ. 2013, 38, 186–190. [Google Scholar]

- Caplinger, M.A.; Malin, M.C. Mars orbiter camera geodesy campaign. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 2001, 106, 23595–23606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fergason, R.L.; Hare, T.M.; Laura, J. HRSC and MOLA Blended Digital Elevation Model at 200 m v2. USGS Astrogeology Science Center, PDS Annex. 2018. Available online: https://astrogeology.usgs.gov/search/map/Mars/Viking/HRSC_MOLA_Blend (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Christensen, P.R.; Bandfield, J.L.; Bell, J.F., III; Gorelick, N.; Hamilton, V.E.; Ivanov, A.; Jakosky, B.M.; Kieffer, H.H.; Lane, M.D.; Malin, M.C.; et al. Morphology and composition of the surface of Mars: Mars Odyssey THEMIS results. Science 2003, 300, 2056–2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McEwen, A.S.; Eliason, E.M.; Bergstrom, J.W.; Bridges, N.T.; Hansen, C.J.; Delamere, W.A.; Grant, J.A.; Gulick, V.C.; Herkenhoff, K.E.; Keszthelyi, L. Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter’s High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE). J. Geophys. Res. Planets 2007, 112, E05S02. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, R.L.; Howington-Kraus, E.; Rosiek, M.R.; Anderson, J.A.; Archinal, B.A.; Becker, K.J.; Cook, D.A.; Galuszka, D.M.; Geissler, P.E.; Hare, T.M.; et al. Ultrahigh resolution topographic mapping of Mars with MRO HiRISE stereo images: Meter-scale slopes of candidate Phoenix landing sites. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 2008, 113, E00A24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A.E.; Aaron, S.B.; Ansari, H.; Bergh, C.; Bourdu, H.; Butler, J.; Chang, J.; Cheng, R.; Cheng, Y.; Clark, K.; et al. Mars 2020 lander vision system flight performance. In Proceedings of the AIAA SciTech 2022 Forum, San Diego, CA, USA, 3–7 January 2022; Volume 1214. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, J.F., III; Maki, J.N.; Mehall, G.L.; Ravine, M.A.; Caplinger, M.A.; Bailey, Z.J.; Brylow, S.; Schaffner, J.A.; Kinch, K.M.; Madsen, M.B.; et al. The Mars 2020 perseverance rover mast camera zoom (Mastcam-Z) multispectral, stereoscopic imaging investigation. Space Sci. Rev. 2021, 217, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fergason, R.L.; Hare, T.M.; Mayer, D.P.; Galuszka, D.M.; Redding, B.L.; Smith, E.D.; Shinaman, J.R.; Cheng, Y.; Otero, R.E. Mars 2020 terrain relative navigation flight product generation: Digital terrain model and orthorectified image mosaic. In Proceedings of the 51st Lunar and Planetary Science Conference, 2020, No. 2326. The Woodlands, TX, USA, 16–20 March 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gwinner, K.; Scholten, F.; Preusker, F.; Elgner, S.; Roatsch, T.; Spiegel, M.; Schmidt, R.; Oberst, J.; Jaumann, R.; Heipke, C. Topography of Mars from global mapping by HRSC high-resolution digital terrain models and orthoimages: Characteristics and performance. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2010, 294, 506–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ody, A.; Poulet, F.; Langevin, Y.; Bibring, J.-P.; Bellucci, G.; Altieri, F.; Gondet, B.; Vincendon, M.; Carter, J.; Manaud, N.C.E.J. Global maps of anhydrous minerals at the surface of Mars from OMEGA/MEx. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 2012, 117, E00J14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Chen, W.; Cao, Z.; Wu, F.; Lyu, W.; Song, Y.; Li, D.; Yu, C.; Zhang, L.; Wang, L. The navigation and terrain cameras on the Tianwen-1 Mars rover. Space Sci. Rev. 2021, 217, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, K.J.; Weller, L.A.; Edmundson, K.L.; Becker, T.L.; Robinson, M.S.; Enns, A.C.; Solomon, S.C. Global controlled mosaic of Mercury from MESSENGER orbital images. In Proceedings of the 43rd Annual Lunar and Planetary Science Conference, The Woodlands, TX, USA, 19–23 March 2012; No. 1659. p. 2654. [Google Scholar]

- Roatsch, T.; Kersten, E.; Matz, K.-D.; Preusker, F.; Scholten, F.; Jaumann, R.; Raymond, C.A.; Russell, C.T. High-resolution ceres low altitude mapping orbit atlas derived from dawn framing camera images. Planet. Space Sci. 2017, 140, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, S.; Tsuda, Y.; Yoshikawa, M.; Tanaka, S.; Saiki, T.; Nakazawa, S. Hayabusa2 mission overview. Space Sci. Rev. 2017, 208, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preusker, F.; Scholten, F.; Elgner, S.; Matz, K.-D.; Kameda, S.; Roatsch, T.; Jaumann, R.; Sugita, S.; Honda, R.; Morota, T.; et al. The MASCOT landing area on asteroid (162173) Ryugu: Stereo-photogrammetric analysis using images of the ONC onboard the Hayabusa2 spacecraft. Astron. Astrophys. 2019, 632, L4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatsumi, E.; Domingue, D.; Schröder, S.; Yokota, Y.; Kuroda, D.; Ishiguro, M.; Hasegawa, S.; Hiroi, T.; Honda, R.; Hemmi, R.; et al. Global photometric properties of (162173) Ryugu. Astron. Astrophys. 2020, 639, A83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, K.J.; Edmundson, K.L. Control of OSIRIS-REx OTES observations using OCAMS TAG images. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.12177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, B.G. Technical challenges and results for navigation of NEAR Shoemaker. Johns Hopkins APL Tech. Dig. 2002, 23, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa, N.; Terui, F.; Yasuda, S.; Matsushima, K.; Masuda, T.; Sano, J.; Hihara, H.; Matsuhisa, T.; Danno, S.; Yamada, M.; et al. Image-based autonomous navigation of Hayabusa2 using artificial landmarks: Design and in-flight results in landing operations on asteroid Ryugu. In Proceedings of the AIAA Scitech 2020 Forum, Orlando, FL, USA, 6–10 January 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mario, C.; Norman, C.; Miller, C.; Olds, R.; Palmer, E.; Weirich, J.; Lorenz, D.; Lauretta, D. Image correlation performance prediction for autonomous navigation of OSIRIS-REx asteroid sample collection. In Proceedings of the 43rd Annual AAS Guidance, Navigation & Control Conference, Breckenridge, CO, USA, 1–3 February 2020. AAS 20-087. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, C.; Olds, R.; Norman, C.; Gonzales, S.; Mario, C.; Lauretta, D.S. On orbit evaluation of natural feature tracking for OSIRIS-REx sample collection. In Proceedings of the 43rd Annual AAS Guidance, Navigation & Control Conference, Breckenridge, CO, USA, 1–3 February 2020. AAS 20-154. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz, D.A.; Olds, R.; May, A.; Mario, C.; Perry, M.E.; Palmer, E.E.; Daly, M. Lessons learned from OSIRIS-REx autonomous navigation using natural feature tracking. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Aerospace Conference, Big Sky, MT, USA, 1–12 March 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Maki, J.N.; Gruel, D.; McKinney, C.; Ravine, M.A.; Morales, M.; Lee, D.; Willson, R.; Copley-Woods, D.; Valvo, M.; Goodsall, T.; et al. The Mars 2020 engineering cameras and microphone on the Perseverance rover: A next-generation imaging system for Mars exploration. Space Sci. Rev. 2020, 216, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setterfield, T.P.; Conway, D.; Chen, P.-T.; Clouse, D.; Trawny, N.; Johnson, A.E.; Khattak, S.; Ebadi, K.; Massone, G.; Cheng, Y.; et al. Enhanced Lander Vision System (ELViS) algorithms for pinpoint landing of the Mars Sample Retrieval Lander. In Proceedings of the AIAA SCITECH 2024 Forum, Orlando, FL, USA, 8–12 January 2024; p. 0315. [Google Scholar]

- Maru, Y.; Morikawa, S.; Kawano, T. Evaluation of landing stability of two-step landing method for small lunar-planetary lander. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Space Flight Dynamics (ISSFD), Darmstadt, Germany, 22–26 April 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Takino, T.; Nomura, I.; Moribe, M.; Kamata, H.; Takadama, K.; Fukuda, S.; Sawai, S.; Sakai, S. Crater detection method using principal component analysis and its evaluation. Trans. Jpn. Soc. Aeronaut. Space Sci. Aerosp. Technol. Jpn. 2016, 14, Pt_7–Pt_14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ishii, H.; Takadama, K.; Murata, A.; Uwano, F.; Tatsumi, T.; Umenai, Y.; Matsumoto, K.; Kamata, H.; Ishida, T.; Fukuda, S.; et al. The robust spacecraft location estimation algorithm toward the misdetection crater and the undetected crater in SLIM. In Proceedings of the 31st International Symposium on Space Technology and Science (ISTS), Ehime, Japan, 3–9 June 2017. Paper No. ISTS-2017-d-067/ISSFD-2017-067. [Google Scholar]

- Ishida, T.; Fukuda, S.; Kariya, K.; Kamata, H.; Takadama, K.; Kojima, H.; Sawai, S.; Sakai, S. Vision-based navigation and obstacle detection flight results in SLIM lunar landing. Acta Astronaut. 2025, 226, 772–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getchius, J.; Renshaw, D.; Posada, D.; Henderson, T.; Hong, L.; Ge, S.; Molina, G. Hazard detection and avoidance for the nova-c lander. In Proceedings of the 44th Annual American Astronautical Society Guidance, Navigation, and Control Conference, Charlotte, NC, USA, 7–11 August 2022; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 921–943. [Google Scholar]

- Molina, G.; Hansen, M.; Getchius, J.; Christensen, R.; Christian, J.A.; Stewart, S.; Crain, T. Visual odometry for precision lunar landing. In Proceedings of the 44th Annual American Astronautical Society Guidance, Navigation, and Control Conference, Charlotte, NC, USA, 7–11 August 2022; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 1021–1042. [Google Scholar]

- Thrasher, A.C.; Christian, J.A.; Molina, G.; Hansen, M.; Pelgrift, J.Y.; Nelson, D.S. Lunar crater identification using triangle reprojection. In Proceedings of the AAS/AIAA 2023, Big Sky, MT, USA, 13–17 August 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Li, J.; Guan, Y.; Huang, X. Autonomous Navigation for Powered Descent of Chang’e-3 Lander. Control Theory Appl. 2014, 31, 1686–1694. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, P.; Zhang, H.; Li, J.; Guan, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yang, W.; Yu, J.; Wang, H.; et al. Design and Implementation of the GNC System for the Chang’e-5 Lander-Ascent Combination. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 2021, 51, 763–777. [Google Scholar]

- Song, J.; Rondao, D.; Aouf, N. Deep learning-based spacecraft relative navigation methods: A survey. Acta Astronaut. 2022, 191, 22–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechini, M.; Lavagna, M.; Lunghi, P. Dataset generation and validation for spacecraft pose estimation via monocular images processing. Acta Astronaut. 2023, 204, 358–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloos, J.L.; Moores, J.E.; Godin, P.J.; Cloutis, E. Illumination conditions within permanently shadowed regions at the lunar poles: Implications for in-situ passive remote sensing. Acta Astronaut. 2021, 178, 432–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, J.A. A tutorial on horizon-based optical navigation and attitude determination with space imaging systems. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 19819–19853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, A.; Lax, G. Using artificial intelligence for space challenges: A survey. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 5106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

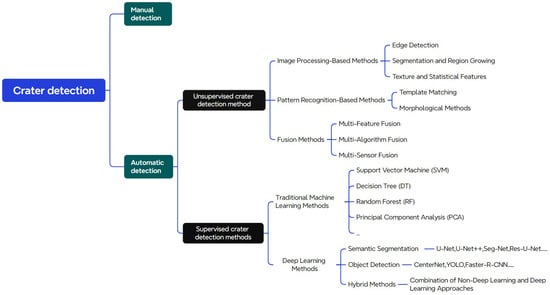

- Chen, D.; Hu, F.; Zhang, L.; Wu, Y.; Du, J.; Peethambaran, J. Impact crater recognition methods: A review. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2024, 1, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.; Yan, J.; Li, M.; Barriot, J.P. A deep learning-based local feature extraction method for improved image matching and surface reconstruction from Yutu-2 PCAM images on the Moon. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2023, 206, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Liang, X.; Wu, F.; Zhang, L. Overview of optical navigation technology development for asteroid descent and landing stage. Infrared Laser Eng. 2020, 49, 20201009. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawai, S.; Scheeres, D.J.; Kawaguchi, J.; Yoshizawa, N.; Ogawawara, M. Development of a target marker for landing on asteroids. J. Spacecr. Rocket. 2001, 38, 601–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Jiang, J.; Ma, Y. A review of vision-based navigation technology based on impact craters. Laser Optoelectron. Prog. 2023, 60, 1106013. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Tewari, A.; Prateek, K.; Singh, A.; Khanna, N. Deep learning based systems for crater detection: A review. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.07727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, S.J.; Hynek, B.M. A new global database of Mars impact craters≥ 1 km: 1. Database Creat. Prop. Parameters [J. Geophys. Res. Planets] 2012, 117, E05XXXX. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kneissl., T.; van Gasselt, S.; Neukum, G. Map-projection-independent crater size-frequency determination in GIS environments—New software tool for ArcGIS. Planet. Space Sci. 2011, 59, 1243–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyer, T.; Iqbal, W.; Oetting, A.; Hiesinger, H.; van der Bogert, C.H.; Schmedemann, N. A comparative analysis of global lunar crater catalogs using OpenCraterTool–An open source tool to determine and compare crater size-frequency measurements. Planet. Space Sci. 2023, 231, 105687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canny, J. A computational approach to edge detection. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 1986, 6, 679–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Miller, J.K. Autonomous landmark based spacecraft navigation system. AAS/AIAA Astrodyn. Spec. Conf. 2003, 114, 1769–1783. [Google Scholar]

- Zuo, W.; Li, C.; Yu, L.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, R.; Zeng, X.; Liu, Y.; Xiong, Y. Shadow–highlight feature matching automatic small crater recognition using high-resolution digital orthophoto map from Chang’E missions. Acta Geochim. 2019, 38, 541–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maass, B. Robust approximation of image illumination direction in a segmentation-based crater detection algorithm for spacecraft navigation. CEAS Space J. 2016, 8, 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Maass, B.; Krüger, H.; Theil, S. An edge-free, scale-, pose- and illumination-invariant approach to crater detection for spacecraft navigation. In Proceedings of the 2011 7th International Symposium on Image and Signal Processing and Analysis (ISPA), Dubrovnik, Croatia, 4–6 September 2011; pp. 603–608. [Google Scholar]

- Bandeira, L.; Ding, W.; Stepinski, T.F. Detection of sub-kilometer craters in high-resolution planetary images using shape and texture features. Adv. Space Res. 2012, 49, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, G.; Guo, L. A novel sparse boosting method for crater detection in the high-resolution planetary image. Adv. Space Res. 2015, 56, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrosa, M.M.; Azevedo, S.C.D.; Silva, E.A.D.; Dias, M.A. Improved automatic impact crater detection on Mars based on morphological image processing and template matching. J. Spat. Sci. 2017, 62, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woicke, S.; Gonzalez, A.M.; El-Hajj, I. Comparison of crater-detection algorithms for terrain-relative navigation. In Proceedings of the AIAA Scitech Forum, Kissimmee, FL, USA, 8–12 January 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M.; Liu, D.; Qian, K.; Li, J.; Lei, M.; Zhou, Y. Lunar crater detection based on terrain analysis and mathematical morphology methods using digital elevation models. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2018, 56, 3681–3692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magee, M.; Chapman, C.R.; Dellenback, S.W.; Enke, B.; Merline, W.J.; Rigney, M.P. Automated identification of Martian craters using image processing. In Proceedings of the Lunar and Planetary Science Conference, Houston, TX, USA, 17–21 March 2003; p. 1756. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, L.; Lim, S. On lunar on-orbit vision-based navigation: Terrain mapping, feature tracking driven EKF. In Proceedings of the AIAA Guidance, Navigation and Control Conference and Exhibit, Honolulu, HI, USA, 18–21 August 2008; AIAA Press: Reston, VA, USA, 2008; p. 6834. [Google Scholar]

- Krøgli, S.O. Automatic Extraction of Potential Impact Structures from Geospatial Data: Examples from Finnmark, Northern Norway. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Degirmenci, M.; Ashyralyyev, S. Impact Crater Detection on Mars Digital Elevation and Image Model; Middle East Technical University: Ankara, Turkey, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Li, W. GeoAI in terrain analysis: Enabling multi-source deep learning and data fusion for natural feature detection. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2021, 90, 101715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, M.; Cao, Y.; Wu, Q. Crater detection in lunar grayscale images. J. Appl. Sci. 2009, 27, 156–160. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepinski, T.F.; Mendenhall, M.P.; Bue, B.D. Machine cataloging of impact craters on Mars. Icarus 2009, 203, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbach, E.R.; Stepinski, T.F. Automatic detection of sub-km craters in high resolution planetary images. Planet. Space Sci. 2009, 57, 880–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Cheng, W.; Yan, G.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, J. A machine learning approach to crater classification from topographic data. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 2594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

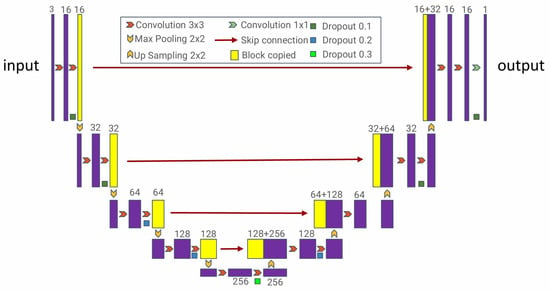

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention–MICCAI 2015: 18th International Conference, Munich, Germany, 5–9 October 2015; Proceedings, Part III, 18. Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, Y.; Liu, L.; Zhang, C. Moon impact crater detection using nested attention mechanism based UNet++. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 44107–44116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silburt, A.; Head, J.W.; Povilaitis, R. Lunar crater identification via deep learning. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 2019, 124, 1121–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Head, J.W.; Fassett, C.I.; Kadish, S.J.; Smith, D.E.; Zuber, M.T.; Neumann, G.A.; Mazarico, E. Global distribution of large lunar craters: Implications for resurfacing and impactor populations. Science 2010, 329, 1504–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Povilaitis, R.Z.; Robinson, M.S.; Van der Bogert, C.H.; Hiesinger, H.; Meyer, H.M.; Ostrach, L.R. Crater density differences: Exploring regional resurfacing, secondary crater populations, and crater saturation equilibrium on the Moon. Planet. Space Sci. 2018, 162, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C. Automated crater detection on Mars using deep learning. Planet. Space Sci. 2019, 170, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLatte, D.M.; Crites, S.T.; Guttenberg, N.; Tasker, E.J.; Yairi, T. Segmentation convolutional neural networks for automatic crater detection on Mars. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2019, 12, 2944–2957. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Liu, W.; Zhang, L. An effective lunar crater recognition algorithm based on convolutional neural network. Space Sci. Technol. 2020, 40, 2694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Cho, Y.; Kim, H. Automated crater detection with human-level performance. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2021, 48, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Su, Z.; Wan, G.; Liu, L.; Liu, J. Ae-transunet+: An enhanced hybrid transformer network for detection of lunar south small craters in LRO NAC images. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2023, 20, 6007405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannakis, I.; Bhardwaj, A.; Sam, L.; Leontidis, G. A flexible deep learning crater detection scheme using Segment Anything Model (SAM). Icarus 2024, 408, 115797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohite, R.R.; Janardan, S.K.; Janghel, R.R.; Govil, H. Precision in planetary exploration: Crater detection with residual U-Net34/50 and matching template algorithm. Planet. Space Sci. 2025, 255, 106029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, D.; Yan, J.; Tu, Z.; Barriot, J.-P. LCDNet: An Innovative Neural Network for Enhanced Lunar Crater Detection Using DEM Data. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

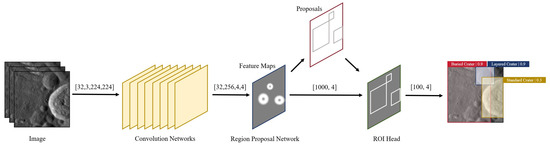

- Girshick, R. Fast R-CNN. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1504.08083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2016, 39, 1137–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redmon, J. You only look once: Unified, real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Szegedy, C.; Reed, S.; Fu, C.-Y.; Berg, A.C. SSD: Single shot multibox detector. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision–ECCV 2016: 14th European Conference, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 11–14 October 2016; Proceedings, Part I, 14. Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 21–37. [Google Scholar]

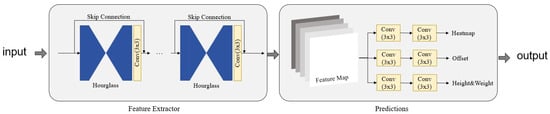

- Duan, K.; Bai, S.; Xie, L.; Qi, H.; Huang, Q.; Tian, Q. CenterNet: Keypoint triplets for object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 6569–6578. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Lv, W.; Xu, S.; Wei, J.; Wang, G.; Dang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Chen, J. DETRs beat YOLOs on real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 16965–16974. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez, L.; Schmidt, F.; Andrieu, F.; Bentley, M.; Talbot, H. Automatic crater detection and classification using Faster R-CNN. Copernicus Meetings 2024, EPSC2024-1005. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, P.; Yang, J.; Kang, Z.; Cao, Z.; Yang, Z. Automatic detection for small-scale lunar impact crater using deep learning. Adv. Space Res. 2024, 73, 2175–2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

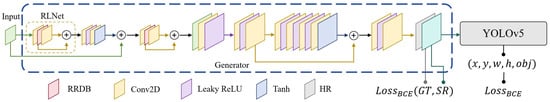

- La Grassa, R.; Cremonese, G.; Gallo, I.; Re, C.; Martellato, E. YOLOLens: A deep learning model based on super-resolution to enhance the crater detection of the planetary surfaces. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

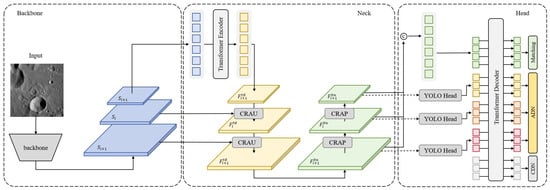

- Guo, Y.; Wu, H.; Yang, S.; Cai, Z. Crater-DETR: A novel transformer network for crater detection based on dense supervision and multiscale fusion. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5614112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Zhao, H.; Bruzzone, L.; Benediktsson, J.A.; Liang, Y.; Liu, B.; Zeng, X.; Guan, R.; Li, C.; Ouyang, Z. Lunar impact crater identification and age estimation with Chang’e data by deep and transfer learning. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 6358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali-Dib, M.; Menou, K.; Jackson, A.P.; Zhu, C.; Hammond, N. Automated crater shape retrieval using weakly-supervised deep learning. Icarus 2020, 345, 113749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Lai, J.; Xie, M.; Zhao, J.; Zou, C.; Liu, C.; Qian, Y.; Deng, J. Identification of lunar craters in the Chang’e-5 landing region based on Kaguya TC Morning Map. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tewari, A.; Jain, V.; Khanna, N. Automatic crater shape retrieval using unsupervised and semi-supervised systems. Icarus 2024, 408, 115761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilduff, T.; Machuca, P.; Rosengren, A.J. Crater detection for cislunar autonomous navigation through convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the AAS/AIAA Astrodynamics Specialist Conference, Big Sky, MT, USA, 13–17 August 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Emami, E.; Ahmad, T.; Bebis, G.; Nefian, A.; Fong, T. Crater detection using unsupervised algorithms and convolutional neural networks. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2019, 57, 5373–5383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

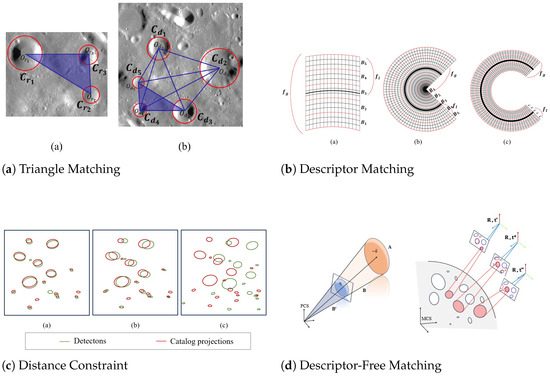

- Christian, J.A.; Derksen, H.; Watkins, R. Lunar crater identification in digital images. J. Astronaut. Sci. 2021, 68, 1056–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solarna, D.; Gotelli, A.; Le Moigne, J.; Moser, G.; Serpico, S.B. Crater detection and registration of planetary images through marked point processes, multiscale decomposition, and region-based analysis. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2020, 58, 6039–6058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroy, B.; Medioni, G.; Johnson, E.; Matthies, L. Crater detection for autonomous landing on asteroids. Image Vis. Comput. 2001, 19, 787–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weismuller, T.; Caballero, D.; Leinz, M. Technology for autonomous optical planetary navigation and precision landing. In Proceedings of the AIAA Space Conference, Long Beach, CA, USA, 18–20 September 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Clerc, S.; Spigai, M.; Simard-Bilodeau, V. A crater detection and identification algorithm for autonomous lunar landing. IFAC Proc. Vol. 2010, 43, 527–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harada, T.; Usami, R.; Takadama, K.; Kamata, H.; Ozawa, S.; Fukuda, S.; Sawai, S. Computational Time Reduction of Evolutionary Spacecraft Location Estimation toward Smart Lander for Investigating Moon. In Proceedings of the 11th International Symposium on Artificial Intelligence, Robotics and Automation in Space (i-SAIRAS2012); European Space Agency (ESA): Frascati, Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sawai, S.; Fukuda, S.; Sakai, S.; Kushiki, K.; Arakawa, T.; Sato, E.; Tomiki, A.; Michigami, K.; Kawano, T.; Okazaki, S. Preliminary system design of small lunar landing demonstrator SLIM. Aerosp. Technol. Jpn. 2018, 17, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haruyama, J.; Sawai, S.; Mizuno, T.; Yoshimitsu, T.; Fukuda, S.; Nakatani, I. Exploration of lunar holes, possible skylights of underlying lava tubes, by smart lander for investigating moon (slim). Trans. Jpn. Soc. Aeronaut. Space Sci. Aerosp. Technol. Jpn. 2012, 10, Pk_7–Pk_10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Cui, H.; Tian, Y. A new approach based on crater detection and matching for visual navigation in planetary landing. Adv. Space Res. 2014, 53, 1810–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Hu, W.; Liu, C.; Yang, D. Relative pose estimation of a lander using crater detection and matching. Opt. Eng. 2016, 55, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, W.; Xie, J.; Cao, L.; Leng, J.; Wang, B. Crater matching algorithm based on feature descriptor. Adv. Space Res. 2020, 65, 616–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maass, B.; Woicke, S.; Oliveira, W.M.; Razgus, B.; Krüger, H. Crater navigation system for autonomous precision landing on the moon. J. Guid. Control. Dyn. 2020, 43, 1414–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, M.; Shao, W. Crater triangle matching algorithm based on fused geometric and regional features. Aerospace 2024, 11, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

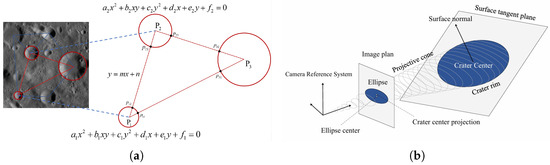

- Chng, C.K.; Mcleod, S.; Rodda, M.; Chin, T.J. Crater identification by perspective cone alignment. Acta Astronaut. 2024, 224, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Ansar, A. Landmark based position estimation for pinpoint landing on Mars. In Proceedings of the 2005 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Piscataway, NJ, USA, 18–22 April 2005; pp. 1573–1578. [Google Scholar]

- Hanak, C.; Crain, T.; Bishop, R. Crater identification algorithm for the lost in low lunar orbit scenario. In Proceedings of the 33rd Annual AAS Rocky Mountain Guidance and Control Conference, Springfield, VA, USA, 5–10 February 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Park, W.; Jung, Y.; Bang, H.; Ahn, J. Robust crater triangle matching algorithm for planetary landing navigation. J. Guid. Control. Dyn. 2019, 42, 402–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doppenberg, W. Autonomous Lunar Orbit Navigation with Ellipse R-CNN; Delft University of Technology: Delft, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, L.H.; Jiang, J.; Ma, Y. Ellipse crater recognition for lost-in-space scenario. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 6027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Jiang, J.; Zhang, G. CraterIDNet: An end-to-end fully convolutional neural network for crater detection and identification in remotely sensed planetary images. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Xu, R.; Li, Z.; Wang, B.; Zhao, Z. Lunar rover collaborated path planning with artificial potential field-based heuristic on deep reinforcement learning. Aerospace 2024, 11, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Wan, G.; Liu, J.; Cong, D. Path Planning for Lunar Rovers in Dynamic Environments: An Autonomous Navigation Framework Enhanced by Digital Twin-Based A*-D3QN. Aerospace 2025, 12, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, W.; Zhang, J.; Hu, H.; Zhang, J.; Sun, H.; Zeng, Z.; Song, J.; Wang, J. Intelligent navigation for the cruise phase of solar system boundary exploration based on Q-learning EKF. Complex Intell. Syst. 2024, 10, 2653–2672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, K.; Zhou, P.; Wei, C. Spacecraft autonomous navigation using line-of-sight directions of non-cooperative targets by improved Q-learning based extended Kalman filter. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part G J. Aerosp. Eng. 2024, 238, 182–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fereoli, G.; Schaub, H.; Di Lizia, P. Meta-reinforcement learning for spacecraft proximity operations guidance and control in cislunar space. J. Spacecr. Rocket. 2025, 62, 706–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).