Abstract

The limited availability of in-situ images of the lunar surface significantly hinders the performance improvement of intelligent algorithms, such as scientific target point-of-interest recognition. To address the low diversity of images generated by traditional data augmentation methods under small-sample conditions, we propose a single-image generative adversarial method based on a blending mechanism of effective channel attention and spatial attention (ECSA-SinGAN). First, an effective channel attention module is introduced to assign different weights to each channel, enhancing the feature representation of important channels. Second, a spatial attention module is employed to assign varying weights to different spatial locations within the image, thereby improving the representation of target regions. Finally, based on a blending mechanism, lunar surface in-situ images are generated step by step, following a pyramidal hierarchy for multi-scale feature extraction. Experimental results show that the proposed method reduces MS-SSIM by 41% compared with SinGAN under identical image quality conditions in the lunar surface in-situ image augmentation task. The method preserves the original image style while significantly improving data diversity, making it effective for small-sample lunar surface in-situ image augmentation.

1. Introduction

With the launch of China’s fourth lunar exploration program, the execution of lunar exploration missions is transitioning toward intelligent and routine operations [1]. One of the key focuses of future exploration missions is the detection of scientific target points of interest on the lunar surface. These include rock piles formed by large amounts of unweathered debris, impact craters of varying sizes, shapes, and locations, as well as rocks with different sizes, shapes, and distributions [2]. Due to the vast distance between Earth and the Moon, coupled with the constraints of the lunar environment, research on target detection using in-situ lunar surface images has been limited. The main challenges are the difficulty of acquiring such images, the scarcity of data, and poor simulation results. In the scientific data collected by the lunar rover’s panoramic camera, varying image perspectives, complex image content, shadow interference, direct sunlight, and color requirements make it challenging to form an effective dataset from the already limited lunar in-situ images. These factors contribute to low detection accuracy and suboptimal performance in models trained using lunar panoramic camera target detection algorithms. To address these challenges, data augmentation methods are commonly employed to supplement the missing target images. Currently, mainstream data augmentation methods fall into two broad categories: traditional methods based on geometric transformations and intelligent methods relying on feature fitting.

In the early stages of data augmentation, most studies employed geometric transformations, such as rotation, translation, shearing, and random erasure, to enhance limited training data, with the goal of improving the accuracy of object detection models. The literature has utilized these methods; however, they failed to increase data diversity, making it challenging to improve the applicability and generalization of detection algorithms. With the introduction of feature-based Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), these networks have consistently outperformed traditional data augmentation methods, gradually replacing them as the primary approach. GANs learn the features of existing samples and generate similar features through feature-based methods, thereby enriching sample diversity. Conditional Generative Adversarial Networks (CGANs) [3] take input labels to generate desired images. From Pix2Pix, which requires paired datasets, to CycleGAN [4], which operates without paired data, literature has successfully applied GANs to the field of image style transfer, addressing the issue of one-to-one image mapping. This advancement provides a novel approach for data augmentation of lunar surface scientific points of interest, specifically transferring image styles from terrestrial images to lunar surface images. However, this method requires large datasets for training and cannot generate high-quality image data in scenarios with small sample sizes [5].

Few generative adversarial networks (GANs) are capable of addressing data augmentation under small-sample conditions. In 2019, SinGAN developed by the Technion–Israel Institute of Technology in collaboration with Google, was proposed [6]. Once trained on a single natural image, SinGAN learns an unconditional generative model of image patches, producing high-quality samples consistent with the original content [7]. For this reason, our study adopts the SinGAN framework as the baseline for lunar in-situ image data augmentation. Nevertheless, since the original training set mainly includes color-rich artistic images as well as natural scenes (e.g., lakes, birds), its direct application to lunar data results in limited target diversity. Enhancing the diversity of lunar in-situ images is therefore essential for constructing a high-quality dataset [8].

This paper addresses the issues of limited quantity and poor content diversity in current lunar panoramic camera image datasets by proposing a dual-channel, feature-based single-image generation method using ECSA-SinGAN. The main contributions are as follows:

- (1)

- We propose a single-image generative adversarial model based on the fusion of channel and spatial features, designing feature extraction mechanisms for both channel and spatial dimensions. We employ ECA and SAM to extract channel-based and spatial-position-based feature information, respectively, enhancing the model’s ability to represent features under different attention mechanisms and improving its generalization capability.

- (2)

- We investigate the impact of channel and spatial features in a cascaded structure, comparing them to their effects under separate conditions. Experimental results show that, compared to current SinGAN-based network methods, the proposed ECSA-SinGAN method effectively enhances the diversity of generated image content while maintaining high image generation quality.

The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 details the proposed network architecture. Section 3 explains the experimental design along with parameter settings, and Section 4 reports the experimental results. Section 5 presents the experimental analysis. Finally, Section 6 concludes with future research directions.

2. SinGAN Data Enhancement Method

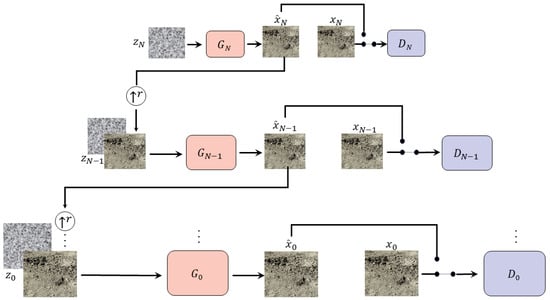

SinGAN mitigates the reliance of conventional GANs on large datasets by extracting intrinsic statistical features—such as texture, structure, and local patch patterns—from a single image. This allows multi-resolution synthesis of high-fidelity samples while retaining the source image’s visual semantics. Employing a pyramidal multiscale design with coarse-to-fine training, it is used to augment lunar panoramic camera data. In Figure 1, G and D denote the scale-specific generator and discriminator [9,10,11]; , , and represent the noise input, generated output, and real image, respectively. Each scale hosts an independent GAN that operates solely within its resolution for generation and discrimination.

Figure 1.

SinGAN’s multi-scale structure: the left shows generator training and the right shows discriminator training.

Our framework adopts a pyramid of generators trained on an image pyramid , where each scale image is obtained by downsampling the original image x by a factor of with . At scale n, the generator is responsible for producing realistic samples whose patch statistics align with those of .

Each generator is trained adversarially against a corresponding discriminator . The generator attempts to synthesize patches that fool , while the discriminator learns to distinguish between real patches from and synthetic patches from . The final discrimination score is aggregated over the patch-level predictions, enabling consistent learning across the full image domain.

To preserve cross-scale consistency, the output at scale n is progressively refined at finer scales. Specifically, noise is injected into the generators at each level, allowing them to capture new image details. Coarse generators provide the global structure of the image, while fine generators add higher-frequency details such as textures and edges. This hierarchical design enables the model to reproduce realistic image statistics while maintaining global coherence across scales.

The generation process begins at the coarsest scale and proceeds through all generators to the finest, with noise injected at each stage. Since generators and discriminators share the same receptive field, they capture progressively finer structures as resolution increases. At the coarsest scale, maps spatial white Gaussian noise into an image sample .

At this scale, the effective receptive field is about ∼ of the image height, enabling to capture the overall layout and global structure. At finer scales , each generator enriches the image with details absent from previous levels. Consequently, besides receiving spatial noise , each also takes as input an upsampled image produced by the preceding coarser scale, i.e.,

All generators share a similar architecture (Figure 2). At scale n, the input noise is combined with the upsampled image and processed by convolutional layers. This design mitigates the common issue in conditional settings where the GAN may disregard stochastic inputs. The convolutional layers refine by adding the missing details through residual learning. Formally, the generator is defined as

where is a fully convolutional network of five blocks, each consisting of Conv()–BatchNorm–LeakyReLU. At the coarsest scale, each block uses 32 kernels, doubling every four scales. With its fully convolutional design, the generator can synthesize images of arbitrary size and aspect ratio at test time by adjusting noise map dimensions [12,13].

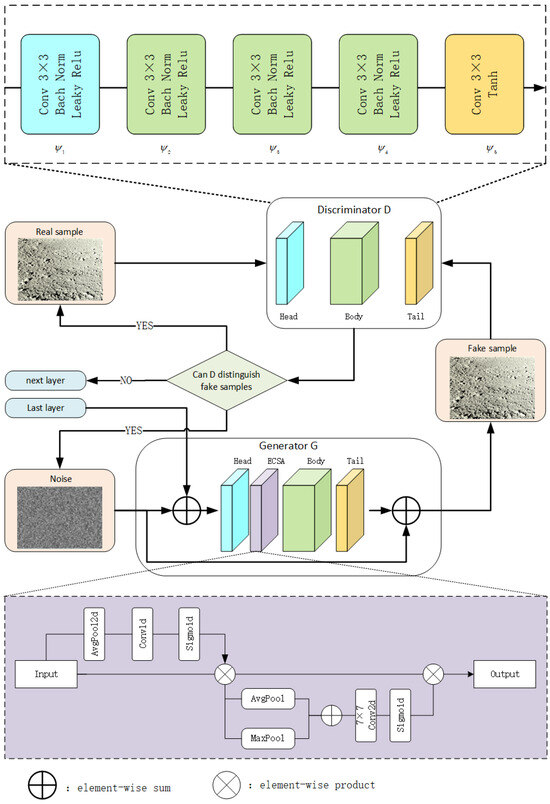

Figure 2.

Attention framework based on channels and spatial.

3. ECSA-SinGAN Design Based on Blending Attention Mechanism

3.1. Attention Framework Based on Channels and Spatial

In this paper, we propose the Effective Channel Spatial Attention (ECSA) module, a blending attention mechanism for convolutional neural networks in SinGAN. SinGAN generates samples by modeling an image’s internal patch distribution with a multiscale generator [14,15].The ECSA module helps preserve global structure while enhancing local features by dynamically combining attention weights, thus producing more diverse outputs. After the generator head, an intermediate feature map is extracted and processed sequentially along channel and spatial dimensions to generate attention maps. These maps are multiplied with the input feature map for adaptive weighting [15,16]. ECSA is lightweight and general-purpose, integrating into SinGAN with minimal cost, and can also be used with the base convolution module for end-to-end training [17].

As shown in Figure 2, the generated image from the previous scale, together with noise, is fed into the generator to produce a higher-scale fake sample. The fake sample is then evaluated by the discriminator D; if the discriminator classifies it correctly, the process is repeated until the discriminator can no longer reliably distinguish the generated image. The discriminator itself is trained using real images as inputs. The proposed ECSA module consists of a sequential integration of the Efficient Channel Attention module and the Spatial Attention module [18,19].

Given an intermediate feature map , ECSA sequentially computes the ECA channel attention and the 2D spatial attention map , as shown in Figure 2. The overall mechanism is summarized as:

where ⊗ denotes element-wise multiplication. Here, channel attention values are broadcast along spatial dimensions, and is the final output [20].

In the SinGAN generator, forms the HEAD, , , and constitute the BODY, and serves as the TAIL, as shown in Table 1. This structure is applied consistently across all scales. During generation, each newly produced image incorporates the detailed information missing from the preceding scale. Consequently, image synthesis begins at the top layer of the pyramid and proceeds sequentially through each generator layer, progressively producing image samples with increasingly complete details [21,22].

Table 1.

The network structure of the generator.

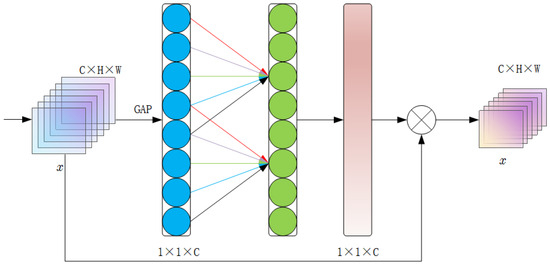

3.2. Effective Channel Attention Module

The attention mechanism in deep learning models emulates human focus by selectively emphasizing parts of the input. Instead of assigning equal weights, it allocates them according to the model’s focus, prioritizing task-relevant information and improving classification accuracy. The Efficient Channel Attention (ECA), shown in Figure 3, enhances convolutional neural network features by effectively capturing inter-channel dependencies [23].

Figure 3.

ECA module.

Given an input image with C channels, height H, and width W, the ECA mechanism applies Global Average Pooling (GAP) to capture channel-wise context, as shown in Figure 3. The GAP operation is defined as:

Here, denotes the -th element of channel c in the input feature map X. The GAP output is a C-dimensional vector representing the average response of each channel.

Next, the ECA mechanism models local channel dependencies using a one-dimensional convolution (1D Convolution Layer). With kernel size k, ECA dynamically sets k according to the number of channels, enabling adaptation to different dimensions and effective capture of local interdependencies. The kernel size k is computed as:

Here, r is a hyperparameter that controls the range of local dependencies. A smaller r results in a larger convolution kernel size, thereby covering a wider scope of channel relationships [24].

The output of a 1D convolutional layer is given by:

To enable adaptive learning of inter-channel correlations within the model, the 1D convolution output passes through a Sigmoid function, yielding a vector of attention weights [25,26]:

Finally, the attention weight vector A is applied to the original input feature map X through element-wise multiplication, thereby achieving channel attention rescaling. The recalibrated feature map is given by:

The ECA mechanism improves convolutional network features by capturing inter-channel dependencies [27]. It is efficient, lightweight, and integrates easily with existing architectures. With localized adaptive channel attention, ECA further boosts feature representations and overall performance [28].

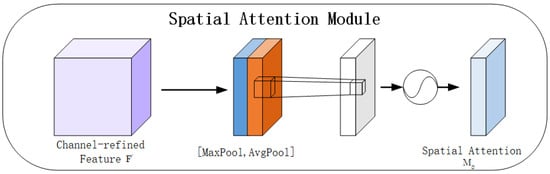

3.3. Spatial Attention Mechanisms

The Spatial Attention Mechanism (SAM) produces a spatial attention map by exploiting the spatial relationships among features. Unlike channel attention, which focuses on inter-channel dependencies, spatial attention emphasizes positional information, making it complementary to channel attention.

As shown in Figure 4, in the spatial attention module, average-pooling and max-pooling are applied along the channel axis to aggregate spatial information, producing two 2D maps: and , representing average- and max-pooled features. These maps are concatenated into a feature descriptor and passed through a convolution layer to generate the spatial attention map , which highlights regions to emphasize or suppress.

Figure 4.

SAM.

Formally, the spatial attention is computed as:

where is the sigmoid function and denotes a convolution with filter size .

4. Experiments

4.1. Dataset and Environment

The Jade Rabbit II rover discovered numerous small-scale impact craters with high reflectivity in the Chang’e-4 landing zone, ranging in size from a few centimeters to several meters in diameter. Many broken rocks were found accumulated along the rims of these craters, contrasting sharply with the surrounding dark, weathered layers and highly degraded impact craters, suggesting that the rocks were formed during a recent geological event. Small impact craters and their centimeter-sized spatters are challenging to document due to the ongoing external erosion of the lunar surface and limitations in image resolution. The debris piles on the lunar surface, composed of these broken rocks, are crucial scientific target points for exploration and research on the geological profiles of lunar regions, analysis of samples from the Lunar Panoramic Camera (LPC), and experiments on the in-situ utilization of resources. Studying these debris piles is of great significance, as they are closely linked to the evolution of the Moon’s most superficial layers.

Impact craters, widely distributed across the Moon, are the most prominent topographic features on its surface. These craters vary in size, ranging from large to small, and are often densely packed, forming circular structures. They include impact craters, radial patterns, and uplift formations associated with crater impacts. Impact craters are topographic marks or ring-shaped geological units formed by the high-speed impacts of asteroids, comets, and other small celestial bodies, which excavate lunar surface materials. The features of these craters provide an intuitive reflection of the lunar surface characteristics and the current state of the Moon, while also recording historical information about the formation and evolution of the Moon. The exploration and study of these lunar features offer valuable insights into the Moon’s state, structure, and composition, providing reliable and direct evidence for scientific inquiries into the origin and evolutionary history of the Moon.

The Moon’s surface features meter-sized rocks and a wide distribution of rock fragments ranging from centimeters to millimeters in size. These rocks are generally less susceptible to impact metamorphism and space weathering than lunar meteorites and lunar soil. They originate from various parts of the Moon, with a high probability of obtaining well-focused samples. Conducting continuous sampling and analysis missions on the lunar surface to obtain detailed mineral and chemical compositions of the lunar crust will provide key evidence for studying major scientific issues, such as the evolution of the magma ocean and the Moon’s impact history. This research is of great significance for the future advancement of China’s lunar scientific endeavors.

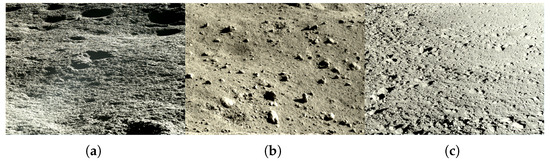

The dataset used in this paper is derived from the scientific data captured by the panoramic camera (PCAM) of the CE-4 rover. The color images were obtained after preprocessing the scientific data. As shown in Figure 5, three types of images, including old impact craters, rocky blocks, and debris piles, were selected for the dataset. The experimental environment configuration is shown in Table 2.

Figure 5.

(a) old impact craters. (b) rocky blocks. (c) debris piles.

Table 2.

Experimental environment configuration.

4.2. Discriminators and Loss Functions

The multi-scale framework trains sequentially from the coarsest to the finest scale. After each GAN is trained, its parameters remain fixed. For the n-th GAN, The training objective includes two components: adversarial loss and reconstruction loss.

The adversarial loss measures the discrepancy between the patch distribution of and that of the generated samples . The reconstruction loss ensures that a specific set of noise maps can reproduce , which is essential for image manipulation tasks. The details of and are provided below.

Adversarial loss. Each generator pairs with a Markovian discriminator that classifies overlapping patches. Training uses WGAN-GP loss, and the final score is the average of patch outputs. Unlike texture-oriented single-image GANs that define the loss on random crops (batch size 1), our formulation applies it to the entire image, enabling the model to capture boundary conditions, a crucial aspect in this setting. The discriminator follows the same architecture as the network inside , with a receptive field (patch size) of .

Reconstruction loss. To guarantee the existence of a noise configuration that reproduces the original image x, we define a fixed set of inputs , where is sampled once and kept constant throughout training. Let denote the image generated at scale n using these noise maps. For ,

and for , we use .

The reconstructed image also serves to estimate the noise standard deviation at each scale. In particular, is set proportional to the root mean squared error (RMSE) between and , reflecting the level of detail that must be introduced at that scale.

4.3. Assessment of Indicators

Single Image Fréchet Inception Distance (SIFID) is adopted to evaluate the quality of generated images. Unlike the traditional Fréchet Inception Distance (FID), SIFID measures the feature distribution of a single image by leveraging the output of a specific layer in the Inception V3 model. A smaller SIFID value generally corresponds to higher visual quality in the generated results [29].

While FID has become a widely used metric for assessing GAN-based image generation, this study applies SIFID, as proposed in the SinGAN model, to better suit the single-image generation setting. Different from FID, which relies on activation vectors after the final pooling layer of Inception V3, SIFID extracts single-image features from the convolutional layer prior to the second pooling stage. Lower SIFID values thus indicate that the generated images are closer to real ones in terms of feature representation [30,31].

Multi-Scale Structural Similarity (MS-SSIM) is a metric that evaluates image similarity from brightness, contrast, and structural perspectives. In the context of generative models, lower MS-SSIM values indicate greater diversity among generated images, providing a useful measure of both quality and variability [32,33].

To account for the fact that human visual perception is sensitive to image structures across multiple spatial resolutions, the Multi-Scale SSIM (MS-SSIM) extends SSIM by performing a multi-level image decomposition, through iterative low-pass filtering and downsampling, and then evaluating SSIM components at each scale. The Structural Similarity Index (SSIM) is a perceptual metric that evaluates image quality degradation by measuring the structural similarity. SSIM assesses image similarity from three complementary aspects: luminance, contrast, and structural consistency.These components are, respectively, defined as , , and , where and denote the local means, and represent the standard deviations, and is the cross-covariance between corresponding image patches. The overall SSIM index is computed as the product of these three terms, where higher values indicate greater perceptual similarity. MS-SSIM quantifies similarities between synthetic images by comparing pixel-level and structural information. Higher MS-SSIM values suggest stronger similarity, whereas lower values reflect greater diversity within the same class. Formally, MS-SSIM is calculated between two images x and y [34].

In this equation, structure and contrast features are computed at scale j, while luminance is measured at the coarsest scale M. The final MS-SSIM score is obtained as a weighted combination of these multi-scale measurements, expressed as

where M denotes the number of scales and , , and are the corresponding weighting coefficients that control the relative importance of luminance, contrast, and structural terms at each scale.

4.4. Image Enlargement Process

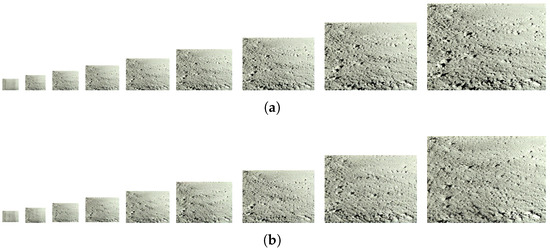

Multi-layer GAN structures are designed in SinGAN to learn the distribution of image blocks at different scales, generating higher resolution images progressively from coarse to fine, better learning of the overall layout and structure of the image at coarse scales, and increased learning of detailed features such as texture at fine scales. Figure 6 shows an example of step-by-step generation of the image of the debris pile on the moon’s surface.

Figure 6.

(a) Train pyramid set. (b) Generate pyramid set.

4.5. Comparative Experiments

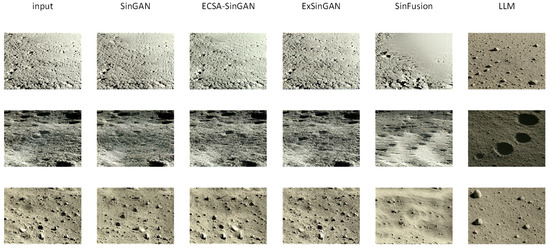

In the generation of panoramic camera scenes, ExSinGAN, SinFusion [35], and GPT-4o are comparable to the baseline model SinGAN, although there is an increase in the diversity of content, and there is a decrease in image quality. For ExSinGAN, the change in image quality shows a particularly obvious decrease. SinFusion in the generation of the target leaves a lot of blanks, and GPT-4o is more affected by the prompt, so it contains more earth-soil factors in the generated images. The ECSA-SinGAN proposed in this paper achieves an increase in the diversity of generated content by decreasing the MS-SSIM by 41% while ensuring the quality of image generation.

As shown in Figure 7, the same training images are selected for testing, and identical experiments are conducted on the baseline models SinGAN, ExSinGAN, the diffusion model SinFusion, and GPT-4o, as well as on the proposed ECSA-SinGAN. For each training image, the same number of random samples is generated to ensure fairness across models. When using GPT-4o, it is necessary to provide a corresponding prompt along with the input image. The content of the prompt is: “Please generate a similar lunar surface image based on this image.” The average SIFID value of the generated images is calculated as the evaluation index of model performance, while the MS-SSIM value of the generated images is calculated as the evaluation index of generation diversity. The experimental results, summarized in Table 3, provide a direct comparison among the models. Specifically, the average SIFID of the generated images is used as the quantitative metric for evaluating performance, and the MS-SSIM value is used as the metric for assessing diversity. The results, shown in Table 3, demonstrate that ECSA-SinGAN achieves noticeable improvements over the original SinGAN and other comparison models in terms of generation diversity, while still preserving image quality.

Figure 7.

Comparative figure.

Table 3.

Comparative Experimental results table.

On the SIFID metrics, the quality of images generated by ECSA-SinGAN is better than ExSinGAN, the diffusion model SinFusion, and GPT-4o when using the same training data. The external pre-training information introduced by ExSinGAN during image generation reduces the quality of the original images generated. The diffusion model SinFusion generates a large number of blank intervals in the image generation, which is not consistent with the real lunar surface. GPT-4o has the texture characteristics of ground soil due to the large amount of original earth surface information in its large model and the influence of the prompt in the image generation.ECSA-SinGAN learns the information inside the image under the multi-scale feature network to learn the information inside the image, which ensures the stability of the image quality.

ECSA-SinGAN outperforms SinGAN in the MS-SSIM metrics due to the fact that the ECSA design introduced by ECSA-SinGAN plays a role in maintaining the global consistency of the image, which enhances the model’s ability to reconstruct the details and textures of the image. SinGAN sometimes fails to reconstruct strong structures, which leads to a higher score, while ECSA-SinGAN better balances reconstruction and variation.

4.6. Ablation Experiments

The MS-SSIM value of SinGAN rises after adding the ECA channel attention mechanism; the MS-SSIM value rises after adding the SAM spatial attention mechanism, in Table 4.

Table 4.

Ablation Experimental results table.

Subject to the limitation of a single attention mechanism, when ECA is used alone, the channel attention highlights key features by adjusting the weights of different channels, which can cause the model to pay excessive attention to the features of a few dominant channels and inhibit the information expression of other channels. In image generation, certain color or texture channels are over-enhanced, and the generation model tends to be homogeneous. When SAM is used alone, spatial attention directs the model to focus on critical regions (e.g., object edges) by weighting spatial locations, and the resulting local bias causes the model to ignore global semantic associations. The model may repeatedly generate similar spatial structures (e.g., fixed-angle objects), limiting diversity. SinGAN’s MS-SSIM values instead decreased after incorporating both ECA and SAM.

Synergized by the crosstalk mechanism, channel attention first screens the feature channels, and spatial attention subsequently assigns spatial weights on the screened features. While retaining the original information features, the filtered information features are strengthened, and this hierarchical processing retains the diversity of channel dimensions while dynamically adjusting the locally generated details through spatial weights to form a more comprehensive feature representation. The joint use of channel attention and spatial attention not only avoids the bias problem of a single attention mechanism, but also enhances the flexibility and diversity of feature expression through information integration. This design essentially simulates the synergistic mechanism of “feature selection—spatial focusing” in the human visual system, thus achieving richer content generation in the task.

Taken together, the ECSA-SinGAN model generates higher quality and more diverse images compared to ExSinGAN, the diffusion model SinFusion, and GPT-4o. Therefore, ECSA-SinGAN has better performance.

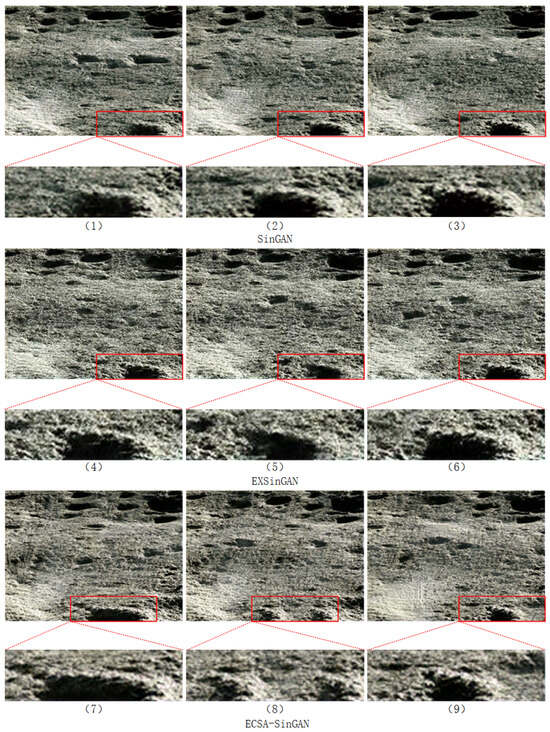

5. Discussion

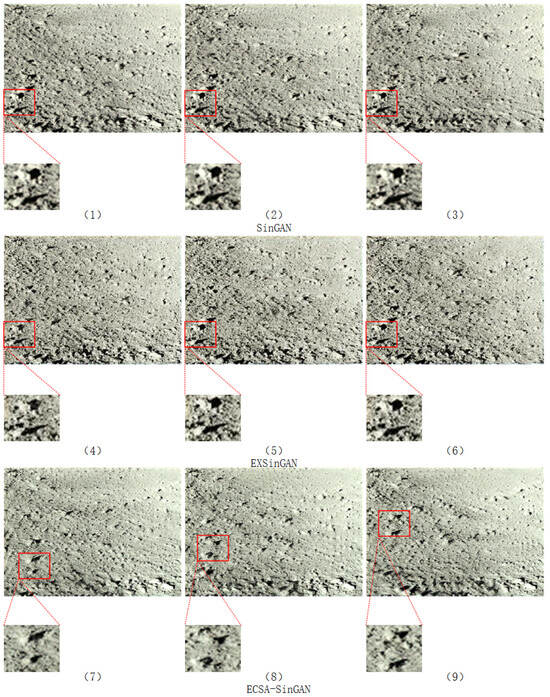

In Figure 8, the craters within the red boxes generated by SinGAN and EXSinGAN exhibit similar structures and repetitive patterns. By contrast, the craters produced by the improved ECSA-SinGAN display significant variations in terms of position, size, morphology, and quantity when compared with the original image.

Figure 8.

Impact craters. Images (1)–(3) are generated by SinGAN, images (4)–(6) are generated by EXSinGAN, and images (7)–(9) are generated by ECSA-SinGAN.

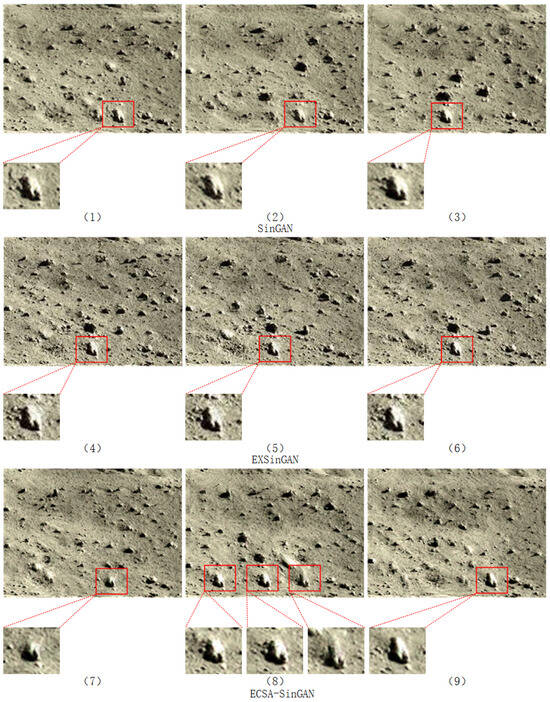

In Figure 9, the debris piles generated by SinGAN and EXSinGAN within the red boxes also demonstrate structural similarity and repetition. However, in the improved ECSA-SinGAN, the shadows, shapes, and spatial distribution of the debris piles undergo notable changes.

Figure 9.

Debris piles. Images (1)–(3) are generated by SinGAN, images (4)–(6) are generated by EXSinGAN, and images (7)–(9) are generated by ECSA-SinGAN.

In Figure 10, the rock blocks generated by SinGAN and EXSinGAN again show repetitive and structurally similar features within the red boxes. In contrast, the rock blocks generated by the improved ECSA-SinGAN present considerable diversity in position, size, morphology, and quantity.

Figure 10.

Rocky blocks. Images (1)–(3) are generated by SinGAN, images (4)–(6) are generated by EXSinGAN, and images (7)–(9) are generated by ECSA-SinGAN.

In terms of practical applicability, the proposed approach offers two primary advantages. First, by enriching data content and increasing the diversity of samples—such as different impact craters, debris piles, and rock blocks—it provides a broader spectrum of feature representations that can support scientific investigations, including tasks such as object detection and recognition. Second, from the perspective of model evaluation, the generated data can serve as test inputs for experimental validation, thereby offering a reliable basis for assessing model performance and robustness.

In terms of limitations, this study primarily focuses on enhancing diversity by accounting for variations in image content, including morphology, size, and spatial position. However, because the source images are obtained mainly from mid- to low-latitude regions, the generated results inherently retain visual characteristics typical of these environments. As a result, images associated with low solar elevation angles—commonly observed in high-latitude regions—are insufficiently represented in the generated outputs. Future research should therefore consider integrating solar elevation angle factors, addressing the challenges posed by low-illumination conditions with high dynamic ranges and, conversely, high-illumination scenarios with pronounced backscattering effects. Expanding the model to capture a broader spectrum of illumination conditions, such as front and backlighting, will further enhance its generalization capability.

6. Conclusions

In this study, we proposed a novel lunar surface image generation method, ECSA-SinGAN, which integrates an effective blending attention mechanism to address the limitations of low target diversity in conventional SinGAN-based single-image generation approaches. By exploiting the synergistic effects of ECA and SAM, the ECSA module effectively mitigates information suppression inherent in single-attention mechanisms, thereby improving the flexibility and diversity of information representation. Using the CE-4 panoramic camera dataset, experimental results demonstrate that our method reduces MS-SSIM by 41% while preserving image quality, thereby confirming its effectiveness in enhancing content diversity. The generated images not only exhibit new structures and target morphologies but also maintain visual characteristics consistent with real lunar surface imagery. This validates the applicability and potential of ECSA-SinGAN for a wide range of lunar surface target detection tasks.

Future work will focus on extending the proposed framework to generate image series under the unique environmental conditions of the lunar south pole and reconstructing 3D models from multi-perspective generated images. Moreover, rapid enhancement of image details captured by rovers during surface exploration will be investigated, as it plays a critical role in supporting real-time operational decision-making.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.Y.; methodology, J.Y.; software, Z.Y.; validation, Y.W. and Z.C.; formal analysis, J.Z.; investigation, Z.Y.; resources, Z.Y.; data curation, Z.Y.; writing original draft preparation, Z.Y.; writing—review and editing, J.Y.; visualization, Z.Y.; supervision, J.Y.; project administration, Q.J.; funding acquisition, J.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by XTT-1 Ground Test System under grant number E16D05A31S.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SinGAN | Single Generative Adversarial Network |

| ECA | Effective Channel Attention |

| SAM | Spatial Attention Mechanism |

| ECSA | Effective Channel and Spatial Attention |

| SIFID | Single Image Fréchet Inception Distance |

| MS-SSIM | Multi-Scale Structural Similarity |

References

- Zhang, Z.; Qin, T.; Shi, Y.; Qiao, D.; Jian, K.; Chen, H.; Zhang, T.; Xu, R.; Jin, X. Research on artificial intelligence technology for lunar scientific research station. J. Deep Space Explor. 2022, 9, 560–570. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.; Ling, Z.; Zhang, J.; Chen, J. Rock size-frequency distributions analysis at lunar landing sites based on remote sensing and in-situ imagery. Planet. Space Sci. 2017, 146, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahsan, R.; Shi, W.; Ma, X.; Croft, W.L. A comparative analysis of CGAN-based oversampling for anomaly detection. IET Cyber-Phys. Syst. Theory Appl. 2022, 7, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, R.; Boukerche, A.; Yu, X.S.; Zhang, C.; Yan, B.; Zhou, X.J. Data augmentation method for insulators based on Cycle GAN. J. Electron. Sci. Technol. 2024, 22, 100250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, V.L.T.; Marques, B.A.D.; Batagelo, H.C.; Gois, J.P. A review on generative adversarial networks for image generation. Comput. Graph. 2023, 114, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaham, T.R.; Dekel, T.; Michaeli, T. Singan: Learning a generative model from a single natural image. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 4570–4580. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Karimi, H.A. Generating high-resolution climatological precipitation data using SinGAN. Big Earth Data 2023, 7, 81–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, S.; Zhang, R.; Luo, H.; Li, M.; Feng, H.; Tang, X. Improved SinGAN integrated with an attentional mechanism for remote sensing image classification. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugahara, R.; Du, W. NNST-based Image Outpainting via SinGAN. In Proceedings of the 2024 10th International Conference on Computing and Artificial Intelligence, Bali Island, Indonesia, 26–29 April 2024; ACM: Xi’an, China, 2024; pp. 26–31. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, M.; Saini, H.C.; Sikarwal, P.K. Exploring the Potential of Sin-GAN for Image Generation and Manipulation. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Blockchain and Distributed Systems Security (ICBDS), Pune, India, 17–19 October 2024; IEEE: Singapore, 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe, K.; Nguyen-Nhu, T.; Takano, S.; Mori, D.; Fujimoto, Y. Data Augmentation for Enhanced Fish Detection in Lake Environments: Affine Transformations, Neural Filters, SinGAN. Animals 2025, 15, 1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thambawita, V.; Salehi, P.; Sheshkal, S.A.; Hicks, S.A.; Hammer, H.L.; Parasa, S.; Lange, T.d.; Halvorsen, P.; Riegler, M.A. SinGAN-Seg: Synthetic training data generation for medical image segmentation. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0267976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakharia, V.; Shah, M.; Suthar, V.; Patel, V.K.; Solanki, A. blending perovskites thin films morphology identification by adapting multiscale-SinGAN architecture, heat transfer search optimized feature selection and machine learning algorithms. Phys. Scr. 2023, 98, 025203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasir, F.A.; Khurshid, K. SyntAR: Synthetic data generation using multiscale attention generator-discriminator framework (SinGAN-MSA) for improved aircraft recognition in remote sensing images. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2025, 84, 42777–42805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Jin, S.; Bian, G.; Cui, Y.; Wang, M. Sample augmentation method for side-scan sonar underwater target images based on cbl-singan. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Wang, X.; Han, T.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, P. Research on a U-Net bridge crack identification and feature-calculation methods based on a CBAM attention mechanism. Buildings 2022, 12, 1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Zhang, C.; Yang, X.; Li, Y. Performance study of CBAM attention mechanism in convolutional neural networks at different depths. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 18th Conference on Industrial Electronics and Applications (ICIEA), Ningbo, China, 18–22 August 2023; IEEE: Shenzhen, China, 2023; pp. 1373–1377. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Yu, Q.; Li, X.; Zeng, H.; Zhang, H.; Gao, H. A CBAM-GAN-based method for super-resolution reconstruction of remote sensing image. IET Image Process. 2024, 18, 548–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Yang, G.; Deng, F.; Qian, Y.; Fan, Y. MCBAM-GAN: The GAN spatiotemporal fusion model based on multiscale and CBAM for remote sensing images. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Mao, K.; Guo, Z. Defogging remote sensing images method based on a blending attention-based generative adversarial network. Smart Agric. 2025, 7, 172–182. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, E.; Hu, X. Image super-resolution via channel attention and spatial attention. Appl. Intell. 2022, 52, 2260–2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Li, L. An attention mechanism and GAN based low-light image enhancement method. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computer, Artificial Intelligence, and Control Engineering (CAICE 2023), Hangzhou, China, 17–19 February 2023; SPIE: Xi’an, China, 2023; Volume 12645, pp. 363–369. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Liu, Y.; Liu, H. Target localization and defect detection of distribution insulators based on ECA-SqueezeNet and CVAE-GAN. IET Image Process. 2024, 18, 3864–3877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Jiang, M.; Li, Y.; Xia, L.; Wang, Z.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H. An efficient ECG denoising method by fusing ECA-Net and CycleGAN. Math. Biosci. Eng. 2023, 20, 13415–13433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakno, M.; Ibrahim, M.Z.; Saealal, M.S.; Fadilah, N.; Samsudin, W.N.A.W. Optimal integration of improved ECA module in cGAN architecture for hand vein segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 10th Information Technology International Seminar (ITIS), Surabaya, Indonesia, 6–8 November 2024; IEEE: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2024; pp. 7–11. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhan, Q.; Ma, Z. EfficientNet-ECA: A lightweight network based on efficient channel attention for class-imbalanced welding defects classification. Adv. Eng. Informatics 2024, 62, 102737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wu, B.; Zhu, P.; Li, P.; Zuo, W.; Hu, Q. ECA-Net: Efficient channel attention for deep convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 11534–11542. [Google Scholar]

- Waghumbare, A.; Singh, U.; Kasera, S. DIAT-DSCNN-ECA-Net: Separable convolutional neural network-based classification of galaxy morphology. Astrophys. Space Sci. 2024, 369, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, M.M.; Rehmani, M.H.; O’Reilly, R. Assessing intra-class diversity and quality of synthetically generated images in a biomedical and non-biomedical setting. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2308.02505. [Google Scholar]

- Dragan, C.M.; Saad, M.M.; Rehmani, M.H.; O’Reilly, R. Evaluating the quality and diversity of DCGAN-based generatively synthesized diabetic retinopathy imagery. In Advances in Deep Generative Models for Medical Artificial Intelligence; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; Volume 1124, pp. 83–109. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-Gaona, Y.; Carrión-Figueroa, D.; Lakshminarayanan, V.; Rodríguez-Álvarez, M.J. GAN-based data augmentation to improve breast ultrasound and mammography mass classification. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2024, 94, 106255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.T.; Imam, R.; Qazi, M.A.; Ukaye, A.; Nandakumar, K.; Dhabi, A. Introducing SDICE: An index for assessing diversity of synthetic medical datasets. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.19436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahamed, M.Y.; Syed, M.A.B. DIVA: Diversity assessment in text-to-image generation via blending metrics. In 4th Muslims in ML Workshop Co-Located with ICML 2025; ICML: Vienna, Austria, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Du, S.; Hong, J.; Wang, Y.; Qi, Y. A high-quality multicategory SAR images generation method with multiconstraint GAN for ATR. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2021, 19, 4011005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaniv, N.; Niv, H.; Michal, I. SinFusion: Training Diffusion Models on a Single Image or Video. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2211.11743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).