Abstract

The Unified Gas–Kinetic Wave–Particle (UGKWP) method is a multiscale method that offers high computational efficiency when solving complex high-Mach-number flows around spacecraft. When the UGKWP method, based on a Graphics Processing Unit (GPU) platform, is used to simulate flow, threads within the same warp are responsible for tracking different particles, leading to a significant warp divergence problem that affects overall computational efficiency. Therefore, this study introduces a dynamic marking tracking algorithm based on block sharing to enhance the efficiency of particle tracking. This algorithm rebuilds the original tracking process by marking and tracking particles, aligning thread computations within the same warp as much as possible to reduce warp divergence. As a result, the average number of active threads increased by over 46% across different testing platforms. The optimized UGKWP platform was used to simulate the re-entry capsule case, and the results showed that the optimized UGKWP can accurately and efficiently simulate the flow details around the capsule. This research provides an efficient and accurate tool for simulating complex multiscale flows at high Mach numbers, which is of great significance.

1. Introduction

With the development of aerospace technology, the airspace for human exploration has expanded from traditional dense atmospheric environments to near space, outer space, and even deep space [1,2]. Correspondingly, the operational airspace of aircraft has extended from traditional single-regime flows to multi-scale regimes that include continuum and rarefied flows. For such multi-scale flow problems, wind tunnel tests face challenges in reproducing all the flight parameters and aerodynamic characteristics of aircraft in near-space conditions. Meanwhile, traditional Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) methods, based on the continuum assumption and Navier–Stokes (NS) equations, are no longer applicable. Therefore, an efficient and accurate cross-regime multi-scale method is key to solving complex multi-scale flow problems. To address this challenge, Xu et al. developed the Unified Gas–Kinetic Wave–Particle (UGKWP) method [3,4,5]. By combining the advantages of deterministic and particle methods through a wave-particle framework, the UGKWP method achieves efficient simulations of flows across all regimes and speed ranges.

The UGKWP method merges particle-free transport with collision processes and can solve all flow regimes, from collisionless free molecular flow to continuum flow. Moreover, the time and space steps of this technique are not limited by collision time or the mean free path, making it a genuinely multi-scale method. In contrast, the Direct Simulation of Monte Carlo (DSMC) method is limited by the molecular collision timescale when choosing the time step, which makes this method less efficient and accurate for near-continuum flow simulations, essentially remaining a single-scale algorithm [6,7]. Meanwhile, the UGKWP method uses simulated particles to adaptively discretize velocity space, demonstrating high computational efficiency and memory utilization in simulating complex high-speed flows. Conversely, both the Unified Gas Kinetic Scheme (UGKS) [8,9,10] and the Discrete Unified Gas Kinetic Scheme (DUGKS) [11,12] methods require a large velocity space for each spatial cell for flows with broad velocity ranges, leading to the “curse of dimensionality” problem [13]. One notable downside of the UGKWP method is that it models low-speed rarefied micro flows, and reducing particle noise greatly raises computational costs. At the same time, when simulating high Knudsen Number (Kn) flows, the UGKWP method still faces significant computational overhead due to the large number of simulated particles, complicating this method’s application in practical engineering problems involving complex multi-scale flows.

Today, as Graphics Processing Units (GPUs) continue to demonstrate increasingly better data processing power compared to Central Processing Units (CPUs), many researchers have shifted CFD programs from CPU to GPU platforms [14,15,16,17,18,19,20]. Since the UGKWP method involves simulating a large number of particles and has significantly higher computational demands than traditional CFD methods, this technique significantly benefits from GPU acceleration. In 2023, Fan et al. [20] implemented the first GPU-based 3D UGKWP method. Using separate cell-parallel and particle-parallel strategies to handle the wave and particle evolution components, the authors achieved a 62× speedup over single-CPU performance. This previous study demonstrated that the GPU-accelerated UGKWP method is especially suitable for particle simulations.

However, due to the complex algorithm and data structure, strong data dependency, and high memory requirement of the unstructured UGKWP method, there remain difficulties in achieving efficient computing on GPU platforms. Currently, only one study by the authors has investigated the unstructured UGKWP method in heterogeneous parallel computing environments [21]. In non-equilibrium flow simulations, particle tracking accounts for a significant portion of the total computation. Because threads within the same warp track different particles, this implementation leads to severe warp divergence in heterogeneous parallel systems, reducing overall computational efficiency. To address this challenge, we introduce a dynamic marking tracking algorithm to enhance computational efficiency in particle tracking.

The structure of this study is organized as follows. Section 2 first analyzes the key computing issues of the UGKWP method, followed by a detailed introduction to the warp divergence issue in particle tracking and proposed a dynamic marking tracking algorithm based on block sharing. Section 3 conducts numerical experiments on the algorithm to verify the accuracy of the algorithm platform and optimize the acceleration effect of the algorithm, presenting the computed results of the algorithm for practical flow problems. Finally, Section 4 concludes with a discussion of findings and future research directions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Performance Analysis

The computation steps of the UGKWP method can be divided into five parts: “initialization and flow field updating”, “flux computation”, “particle sampling”, “particle tracking”, and “microscopic statistics”. The specific processes included in each part are as follows.

- Initialization and flow field updating: the initialization process and flow field update process, including macroscopic conservation quantities and microscopic particles.

- Flux computation: the macroscopic quantity reconstruction process, the analytical flux computation process, and the conservative quantity and time step computation process.

- Particle sampling: the process of particle sampling for collisionless particles.

- Particle tracking: the process of tracking the motion trajectory of particles and updating their positions.

- Microscopic statistics: the process of computing particle flux and statistical particle conservation.

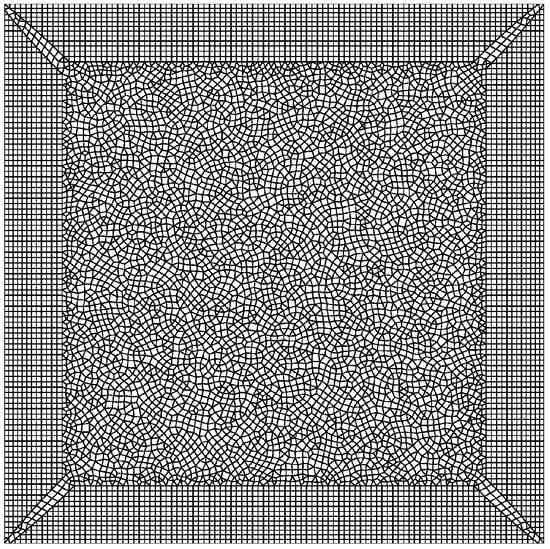

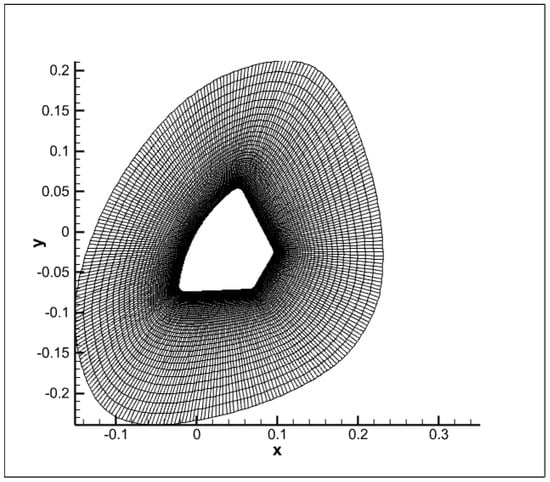

The UGKWP method has complex computational steps and multi-scale parallel granularity. To accurately identify performance bottlenecks on GPU platforms, we first conduct a computational profiling analysis. Table 1 presents the proportion of computation time for each calculation process as the Kn of the flow gradually increases from 0.00001 to 10. These results were obtained using the non-uniform mixed grid shown in Figure 1 under uniform flow conditions. The choice of uniform flow in this study helps eliminate the influence of flow structure, allowing us to draw more general conclusions.

Table 1.

The proportion of computation time for each calculation process.

Figure 1.

100 × 100 hybrid grid.

Table 1 shows that, in the near-continuum flow regime (Kn = 0.00001), the particle tracking process only occupies about 0.5% of the total computation time. The primary computational cost lies in the Initialization and flow field updating and Flux computation processes, where the computational efficiency of the UGKWP method approaches that of GKS. In near-continuous flows, non-equilibrium effects are negligible, leading to a minimal number of sampled particles. This factor reflects the multiscale efficiency-preserving nature of the method. Under such flow conditions, the performance bottleneck of UGKWP mainly stems from computation of the equilibrium flux component. However, as the Kn increases, the time proportion of the particle tracking process grows significantly. In the free-molecular flow regime (Kn = 10.0), particle tracking consumes 61.2% of the computational time. As the Kn increases, the number of free-transport particles in the flow field also increases, eventually far exceeding the number of collisional particles. Under these flow regimes, the main computational load of the UGKWP algorithm shifts from computing the equilibrium flux in the near-continuum flow regime to using simulated particles to compute the flow in the near free-molecular flow regime.

2.2. The Warp Divergence Issues

The UGKWP method requires tracking the motion trajectory of each simulated particle to determine the cell face particle flux and unit particle macroscopic quantity. However, particle motion has strong randomness, resulting in significant differences in computational complexity when parallel threads compute particle trajectories. This phenomenon leads to serious issues of warp divergence and wasted computational resources.

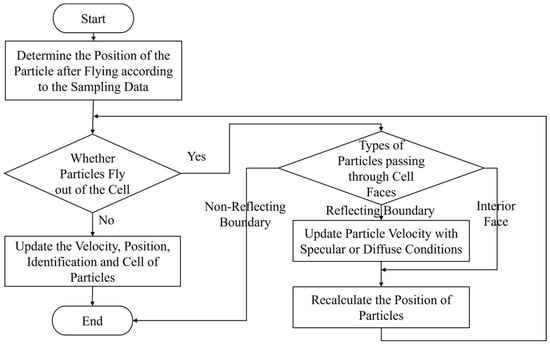

In the particle tracking process of the UGKWP algorithm, the first step is to determine whether the particle has moved out of the current cell. If the particle has not moved out of the current cell, the tracking of the particle is terminated. If a particle moves out of the current cell, it is necessary to determine through which cell face the particle passes to the particle’s subsequent movement state. If the particle passes through the non-reflective boundary face (inflow/outflow, far-field, and other boundary conditions), the particle has left the computational domain, and its data need to be deleted from memory. If a particle passes through the reflective boundary face (symmetry, solid, etc.), the particle will reflect (specular or diffuse) and return to the flow field with a new velocity. If a particle passes through an interface and enters an adjacent cell, the particle will maintain the same velocity and continue to move for the remaining time. By repeating the above steps, we can determine in which cells the particles will ultimately reside. Figure 2 shows the algorithm flow of the particle tracking process.

Figure 2.

The algorithm flow of the particle tracking process.

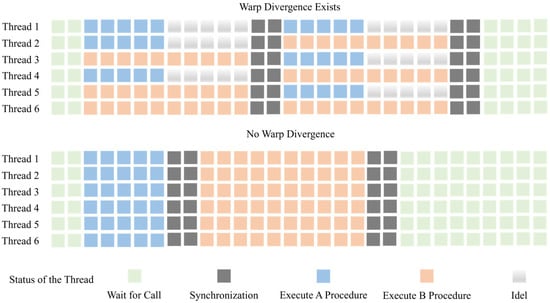

In parallel architectures, all threads in the same warp execute the same instruction during the same clock cycle. However, as shown in Figure 3, the particle tracking kernel performs different computational processes depending on whether particles exit the cells and the type of cell face they pass through. This situation is called warp divergence. When threads performing different computations are placed in the same warp, faster-executing threads must wait until all threads in the warp complete. This warp divergence significantly reduces the number of active threads and decreases thread utilization, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Schematic Diagram of warp divergence issues.

2.3. Proportion of Warp Divergence

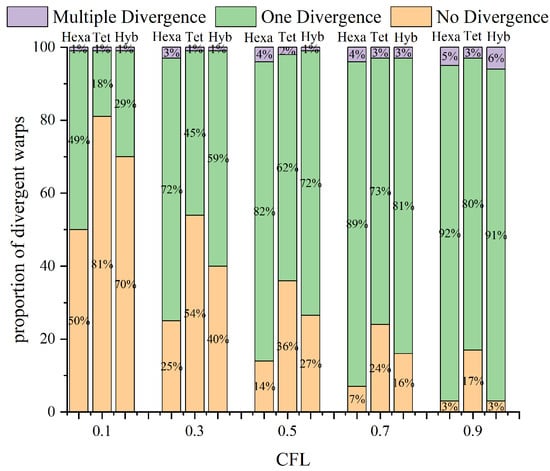

The flight distance of simulated particles mainly influences the proportion of warp divergence in the UGKWP method. For a fixed Kn, a higher CFL number leads to longer particle transport times, which increases the probability of particles crossing cell boundaries into adjacent cells. This study uses three different grid types to assess the ratio of divergent warps to total warps during the particle tracking process under various CFL conditions. The test grids include pure hexahedral grids, pure tetrahedral grids, and hybrid grids, with 125,000, 123,456, and 125,561 cells, respectively.

Figure 4 shows the proportion of divergent warps during the particle tracking process under various conditions. The results indicate that as the CFL number increases, most warps experience at least one divergence event. Among the three tested grid types, pure tetrahedral grids have the lowest proportion of warp divergence.

Figure 4.

Proportion of divergent warps.

There are significant differences in the computational process when particles pass through different cell faces. For example, when the cell face is a non-reflective boundary face, the particle is considered to have exited the computational domain, and there is no need to compute its subsequent motion. For particles experiencing complete diffuse reflection at no-slip walls, their motion states must be sampled according to wall conditions. This process involves generating random numbers and calculating velocity components, which requires additional computational time. Table 2 shows the measured time consumed by particles crossing various types of cell faces. Table 3 shows the measured time consumed by different types of warp divergence during the tracking process. To simplify analysis, all time data are dimensionless and based on the reference condition (i.e., no particles passing through the cell).

Table 2.

The measured time consumed by particles crossing various types of cell faces (the reference condition is no particles passing through the cell).

Table 3.

The measured time consumed by different types of warp divergence (the reference condition is no particles passing through the cell).

Based on the data in Table 2 and Table 3, it can be concluded that particles passing through internal faces require more computational time than particles that remain within the cell due to trajectory tracking. The computational time is shortest when particles pass through non-reflective boundaries since no further tracking is needed. In contrast, for reflective boundaries, additional time is consumed by the computation of both specular and diffuse reflections, with the latter involving random number generation, which contributes significantly to the increased computational cost.

During the particle tracking process, most of the warp divergence occurs when particles cross interfaces into adjacent cells. A small amount of warp divergence appears near the boundary of the computational domain, caused by particle reflection. Combining Figure 4, Table 2 and Table 3 shows that the widespread presence of warp divergence can lead to inefficient use of computing hardware, resulting in a decrease in overall efficiency.

2.4. The Dynamic Marking Tracking Algorithm

This study presents a dynamic marking tracking algorithm designed to reduce the negative impact of warp divergence and improve computational efficiency during the particle tracking process. The algorithm reorganizes the process of “compute (position)—judgment (relationship between trajectory and cell)—loop” used in the original UGKWP method. Before tracking the particle’s trajectory, the algorithm determines whether the particle will pass through the cell face and identifies the type of cell face it will pass through and then marks and classifies the particle accordingly. To minimize warp divergence, the algorithm assigns particles with the same state to physically contiguous and logically adjacent thread groups. Additionally, to avoid frequent global memory access, the algorithm marks particles in on-chip memory after partitioning their data. Once marked, the movement states of particles can be shared within data blocks stored in on-chip memory.

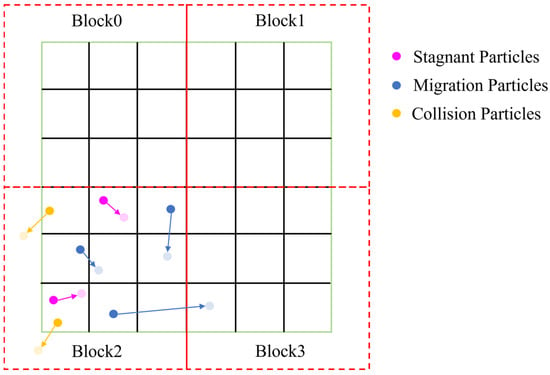

Figure 5 shows the process of particle data partitioning and marking. The regions enclosed by black lines in the figure represent cells, the green border represents the boundary of the computational domain, and the red dashed lines represent the data block containing a certain number of particles. Each data block independently marks the states of particles within its block and assigns a locally contiguous thread group to particles of the same type. In the figure, “stagnant particles” refer to particles whose trajectories do not cross any cell faces, “migration particles” are those whose trajectories intersect internal cell faces, and “collision particles” are those whose trajectories intersect the domain boundaries and reflect.

Figure 5.

The general process of particle data partitioning and particle marking.

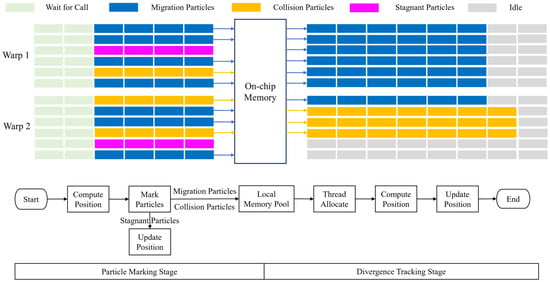

The implementation process of the dynamic marking tracking algorithm has two stages: “particle marking” and “divergence tracking”, as shown in Figure 6. During the particle marking stage, the particle–cell relationship is determined based on particle positions, and particles are marked accordingly. In this stage, each thread in the warp performs an equal computational load—one SAXPY operation and one particle–cell relationship calculation—to avoid warp divergence. If a particle is marked as “stagnant”, it remains in its original cell and only needs position updating without further loops. Particles marked as “migration” or “collision” require at least two loops to determine their final positions. In these cases, particles are placed in a “local memory pool” composed of on-chip memory. Particles in this pool then proceed to the divergence tracking stage. After all particles in the data block are marked, migration particles and collision particles will be extracted from the local memory pool. The contiguous thread group is then allocated to each of these two types of particle, with unused threads also logically grouped. While CUDA threads run concurrently in software, the number of warps is usually greater than the number of Streaming Multiprocessor Sub-Partitions (SMSPs). Therefore, warps on SMSPs are scheduled sequentially, and idle warps are excluded from scheduling. During the divergence tracking stage, idle warps do not waste hardware resources.

Figure 6.

The “particle marking” and “differentiation tracking” stages of the dynamic marking tracking algorithm.

The local memory pool is located in on-chip memory, ensuring that all particle data (positions, velocities, etc.) required during the divergence tracking stage remains in on-chip memory, avoiding the performance overhead of reading data from outside the chip through the PCIe bus. However, because on-chip memory capacity is limited and the Streaming Multiprocessor’s (SM’s) on-chip resources are evenly distributed among scheduled thread blocks, high demand for on-chip memory by kernel functions can limit the parallel scale of GPU devices. Therefore, the local memory pool of each thread block only records the global indices of migrated and collided particles. As a result, even when global memory utilization exceeds 95%, the on-chip memory usage remains below 5%, thereby ensuring that on-chip memory does not compromise computational accuracy. This design means that during the particle marking stage, SAXPY operations and the “particle–cell” relationship computation for migration and collision particles can only be redundant, and their results are used only for marking particles.

3. Results

3.1. Numerical Result Verification

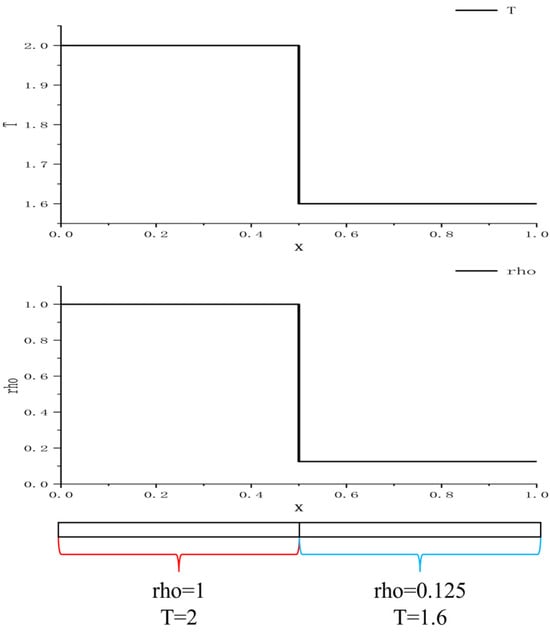

To examine whether the tracking algorithm proposed in this study affects the accuracy of the UGKWP method, we conducted numerical experiments using a Sod shock tube case to validate the accuracy of the full Knudsen-number-range simulation performed using the optimized UGKWP algorithm platform.

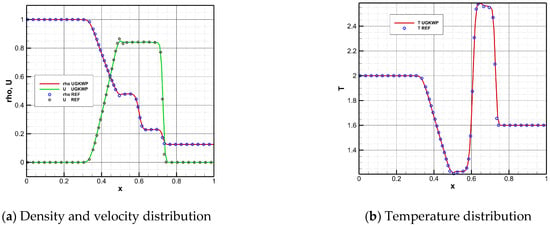

The Sod shock tube problem is a classic unsteady flow test case in numerical scheme research and can be used to evaluate the accuracy and robustness of numerical algorithms when simulating complex flow phenomena. This study uses a two-dimensional quadrilateral mesh with a mesh size of 100 × 1 to compute the Sod problem. The computational domain is [0, 1] × [0, 0.01], and the initial condition is given using Equation (1). A diagram of the shock tube is shown in Figure 7. The reference number of particles per cell, Nref, is set to 1000. The Green–Gauss interpolation algorithm and Venkatakrishnan limiter were also used in the simulation. Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11 present the numerical simulation results obtained using the UGKWP solver after algorithm optimization, and compare those results with those of the reference solution under the UGKS method [8]:

Figure 7.

Schematics Diagram of the Sod shock tube case.

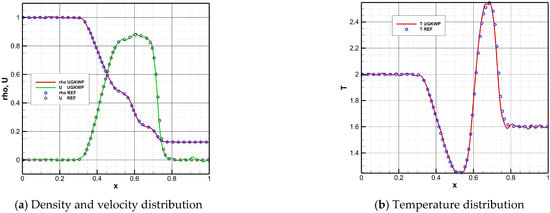

Figure 8.

Parameter distribution of the Sod shock tube at t = 0.12 and Kn = 0.00001.

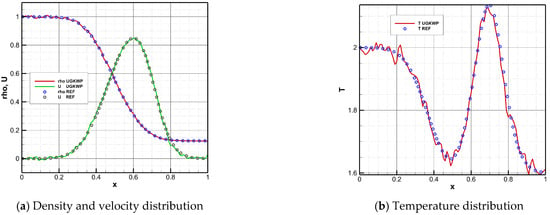

Figure 9.

Parameter distribution of the Sod shock tube at t = 0.12 and Kn = 0.001.

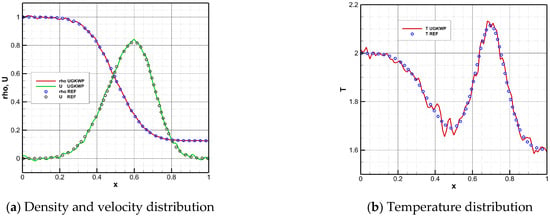

Figure 10.

Parameter distribution of the Sod shock tube at t = 0.12 and Kn = 0.1.

Figure 11.

Parameter distribution of the Sod shock tube at t = 0.12 and Kn = 10.

The numerical results indicate that the optimized UGKWP method can achieve highly consistent results with the UGKS reference solution in the entire flow region from continuum to rarefied, demonstrating the accuracy and reliability of the optimized UGKWP algorithm platform for full-Knudsen-number simulations. The results at different Knudsen numbers show that an increase in the Kn of the flow field leads to more pronounced statistical noise in the numerical results. Moreover, temperature is affected by statistical noise to a significantly greater extent than density and velocity. The reason for this situation is that as the Kn increases, the proportion of collisional particles in the flow field rises, and non-equilibrium effects become more pronounced. Temperature, being a second-order moment of the distribution function, exhibits a higher level of noise than that of lower-order quantities such as density and velocity.

3.2. Algorithm Acceleration Effect

To evaluate the acceleration effect of the proposed block-shared dynamic tag-tracking algorithm on particle tracing, numerical experiments were conducted on the unstructured mesh shown in Figure 1. The simulations were performed using an RTX 3090 GPU under a flow condition with a Knudsen number of 0.001.

The degree of warp divergence can be measured by two indicators: “Avg. Active Threads Per Warp” and “Avg. Not Predicted Off Threads Per Warp”. The former shows the average number of actively executing threads per warp, while the latter indicates the average number of non-predicated-off threads. Ideally, both indicators should be 32, meaning that all threads in the warp run the same instruction within the same clock cycle, without any divergence. Numerical experiments (Table 4) reveal that the unoptimized particle tracking process exhibits significant warp divergence, with both active and non-predicated-off threads averaging less than 16 per warp, less than 50% thread utilization per clock cycle. As shown in Table 4, implementation of the proposed block-shared dynamic tag-tracking algorithm achieved an increase of over 46% in the average number of active threads on the test platform.

Table 4.

Numerical experimental results of the warp divergence optimization effect.

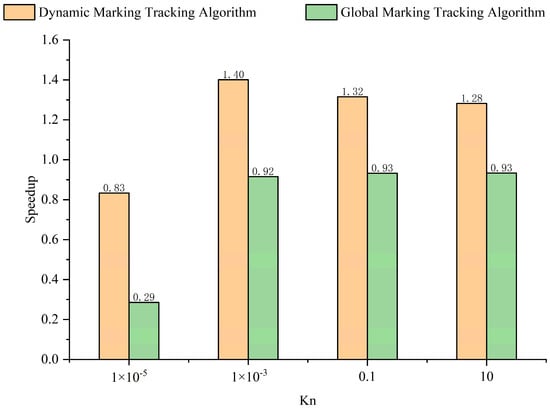

Figure 12 shows the improvement effect of the dynamic marking tracking algorithm based on block sharing on the computational efficiency of the particle tracking process under different flow regimes. For comparison, the performance of the global marking tracking algorithm is also shown in the figure. The global marking tracking algorithm operates by first scanning and marking particle types in global memory before proceeding with classification and computation. While straightforward to implement, this approach increases the volume of data read from global memory. In contrast, the dynamic marking tracking algorithm segments the data, allowing each thread block to be processed independently. This strategy better utilizes the memory hierarchy by placing data frequently accessed during tagging into on-chip memory, thereby reducing global memory traffic. The figure shows that when the Kn is 0.001, using a dynamic marking tracking algorithm can achieve a 40% increase in the overall efficiency of the particle tracking process.

Figure 12.

The improvement effect of the dynamic marking tracking algorithm.

To further demonstrate the computational efficiency of the proposed algorithm under more demanding conditions, a comprehensive set of simulations was conducted based on a 2D shock tube problem at a Knudsen number of 0.001. The performance gains were evaluated across different numbers of particles (Table 5), cell resolutions, and cell types (Table 6).

Table 5.

Increase in the proportion at different particle numbers.

Table 6.

Increase in the proportion at different cell resolutions and for diverse cell types.

The algorithm developed in this study operates exclusively as a hardware-level optimization. Consequently, this algorithm is agnostic to the number of particles and does not alter the outcomes of numerical experiments. Similarly, while the count and type of computational cell influence the warp divergence ratio and thus the algorithm’s efficiency, they do not affect the validity of the simulation results.

To demonstrate the optimization effectiveness of the algorithm under extreme flow conditions, uniform flow simulations were performed on the hybrid mesh shown in Figure 1 at Kn = 10. The resulting speedup ratios across different Mach numbers are summarized in the table below.

Under near free-molecular flow conditions (Kn = 10.0), the number of free-transport particles in the flow field significantly exceeds that of colliding particles. In such regimes, the inter-particle collision frequency is extremely low, allowing the vast majority of particles to maintain fixed memory addresses over multiple consecutive iteration steps. This characteristic reduces the randomness of microscopic data distribution in memory space, thereby alleviating the computational load imbalance caused by thread warp divergence. As shown in Figure 12 and Table 7, the speedup ratio achieved by the algorithm at Kn = 10 is lower than that at Kn = 0.001. The influence of Mach number on the proposed algorithm is similar to that of cell resolutions: it only affects the degree of warp divergence and thus the computational efficiency, without compromising the accuracy of the simulation results.

Table 7.

Increase in the proportion under Kn = 10 across different Mach numbers.

3.3. Two-Dimensional Re-Entry Capsule Case

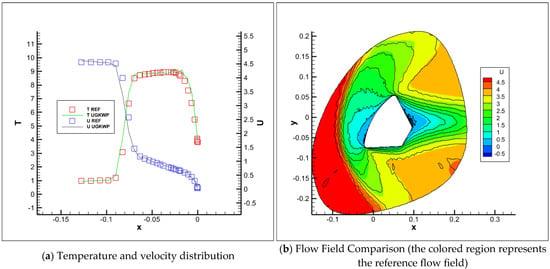

To evaluate the computational ability of the UGKWP algorithm platform we developed for practical flow problems, a numerical simulation was conducted for a two-dimensional re-entry capsule case. The shape and grid of the re-entry capsule are shown in Figure 13. Here, the flow field is discretized with a quadrilateral grid, with 280 and 60 grid points distributed in the circumferential and radial directions, respectively.

Figure 13.

The shape and grid of the re-entry capsule.

The capsule enters a rarefied flow at Kn = 0.001 with a Mach number of 5. The freestream density is 1.794 × 10−5 kg/m3, the freestream pressure is 0.531 Pa, the freestream temperature is 142.2 K, and the wall temperature is set to 500 K. These parameters are configured following the reference settings in Wei’s work [22]. The Green–Gauss interpolation scheme combined with the Venkatakrishnan limiter was employed for macroscopic variable reconstruction, with the reference number of particles per cell set to 4000. A steady flow field was obtained after 30,000 iterations. The resulting flow field was compared with that computed using the DUGKS [11] method, as shown in the Figure 14. A comparison of computational time before and after optimization demonstrates that the optimized algorithm achieves a 15.6% improvement in computational efficiency for the entire particle tracking process.

Figure 14.

Parameter distribution of the two-dimensional re-entry capsule case.

The results clearly demonstrate the flow characteristics around the re-entry capsule under hypersonic conditions: A clear bow shock can be seen in the figure. After passing through the shock, the flow decelerates from supersonic to subsonic in certain regions, consistent with the velocity-blocking effect of the shock in hypersonic flows. At the shoulder of the re-entry capsule, the flow expands supersonically and propagates rearward, resulting in a flow vacuum region near the aft-body. The results demonstrate that the optimized UGKWP method achieves excellent agreement with the DUGKS solutions, confirming the accuracy and reliability of the enhanced algorithm platform.

4. Discussion

The GPU-based unstructured UGKWP algorithm suffers from a significant warp divergence issue. To address this issue, this study proposed a block-shared dynamic marking tracking algorithm. This algorithm restructures the conventional particle tracking workflow by introducing particle marking and categorized tracking, thereby better aligning the computational load among threads within the same warp. The accuracy and efficiency of the dynamic marking tracking algorithm were evaluated using several benchmark test cases. The results show that under various conditions, the optimized algorithm maintains excellent agreement with reference solutions, confirming its accuracy. Furthermore, the average number of active warps increased by over 46%, and the computational efficiency of the entire particle tracking process improved by more than 14%. Thus, the proposed optimization algorithm can effectively mitigate warp divergence in the UGKWP method while preserving numerical accuracy and enhancing overall computational performance.

This work provides an efficient and accurate tool for simulating high-Mach-number, multi-scale, complex flows. However, this study is limited to a single GPU. In multi-GPU systems, warp divergence may present more complex challenges. Additionally, engineering applications of the parallel unstructured UGKWP algorithm still face performance bottlenecks such as memory access conflicts and non-coalesced memory accesses, which will be the focus of our future work.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.Y. and W.R.; methodology, H.Y.; software, H.Y. and Y.C.; validation, Q.F. and W.R.; formal analysis, Y.C.; investigation, Y.C.; resources, Z.T.; data curation, Q.F.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.C.; writing—review and editing, H.Y.; visualization, Y.C.; supervision, W.R.; project administration, Z.T.; funding acquisition, Z.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 12202490), Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province, China (Grant Nos. 2024JJ6455 and 11472004), and Postgraduate Scientific Research Innovation Project of Hunan Province (Grant No. LXBZZ2024001).

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The data are not publicly available due to the large size of the dataset and intellectual property restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| UGKWP | Unified Gas–Kinetic Wave–Particle |

| GPU | Graphics Processing Unit |

| CFD | Computational Fluid Dynamics |

| NS | Navier–Stokes |

| DSMC | Direct Simulation of Monte Carlo |

| UGKS | Unified Gas Kinetic Scheme |

| DUGKS | Discrete Unified Gas Kinetic Scheme |

| Kn | Knudsen Number |

| CPU | Central Processing Unit |

| SMSP | Streaming Multiprocessor Sub-Partition |

| SM | Streaming Multiprocessor |

References

- Zhou, K.; Lou, Y.; Zhang, S.; Ding, D.; Zhang, B. Surrogate multi-objective optimization of missile RCS performance in hypersonic rarefied flow of the near space. AIP Adv. 2024, 14, 075319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, M.R.; Lourenco, S.F. On the nature of near space: Effects of tool use and the transition to far space. Neuropsychologia 2006, 44, 977–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Zhu, Y.; Xu, K. Unified gas-kinetic wave-particle methods I: Continuum and rarefied gas flow. J. Comput. Phys. 2020, 401, 108977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhong, C.; Xu, K. Unified gas-kinetic wave-particle methods. II. Multiscale simulation on unstructured mesh. Phys. Fluids 2019, 31, 067105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Xu, K. Unified gas-kinetic wave-particle methods IV: Multi-species gas mixture and plasma transport. Adv. Aerodyn. 2021, 3, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, G.A. Approach to translational equilibrium in a rigid sphere gas. Phys. Fluids 1963, 6, 1518–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, G.A. Molecular Gas Dynamics and the Direct Simulation of Gas Flows; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, K.; Huang, J.-C. A unified gas-kinetic scheme for continuum and rarefied flows. J. Comput. Phys. 2010, 229, 7747–7764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Wen, X.; Wang, L.P.; Guo, Z.; Wang, J.; Chen, S.; Zhakebayev, D.B. Simulation of three-dimensional forced compressible isotropic turbulence by a redesigned discrete unified gas kinetic scheme. Phys. Fluids 2022, 34, 025106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Xu, K. The first decade of unified gas kinetic scheme. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2102.01261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Xu, K.; Wang, R. Discrete unified gas kinetic scheme for all Knudsen number flows: Low-speed isothermal case. Phys. Rev. E 2013, 88, 033305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, D.; Mao, M.; Li, J.; Deng, X. An implicit parallel UGKS solver for flows covering various regimes. Adv. Aerodyn. 2019, 1, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Xu, K.; Zhong, C. Progress of the unified wave-particle methods for non-equilibrium flows from continuum to rarefied regimes. Acta Mech. Sin. 2022, 38, 122123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, H. GPU implementation of preconditioning method for Low-speed flows. Int. J. Mod. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2016, 42, 1660165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emelyanov, V.N.; Karpenko, A.G.; Kozelkov, A.S.; Teterina, I.V.; Volkov, K.N.; Yalozo, A.V. Analysis of impact of general-purpose graphics processor units in supersonic flow modeling. Acta Astronaut. 2017, 135, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Akhtar, M.N.; Qureshi, K.R.; Durad, M.H.; Usman, A.; Mohsin, S.M.; Shahab, B.; Mosavi, A. Computationally efficient GPU based NS solver for two dimensional high-speed inviscid and viscous compressible flows. Eng. Appl. Comput. Fluid Mech. 2023, 17, 2210196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Guo, X.; Weng, Y.; Zhang, X.; Lu, Y.; Zhao, Z. Hybrid MPI and CUDA paralleled finite volume unstructured CFD simulations on a multi-GPU system. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2023, 139, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Y.; Zhang, X.; Guo, X.; Zhang, X.; Lu, Y.; Liu, Y. Effects of mesh loop modes on performance of unstructured finite volume GPU simulations. Adv. Aerodyn. 2021, 3, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Dai, Z.; Li, R.; Deng, L.; Liu, J.; Zhou, N. Acceleration of a production-level unstructured grid finite volume CFD code on GPU. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 6193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, G.; Zhao, W.; Yao, S.; Jiang, Z.; Chen, W. The implementation of the three-dimensional unified gas-kinetic wave-particle method on multiple graphics processing units. Phys. Fluids 2023, 35, 086108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Xie, W.; Ren, W.; Tian, Z. A piecewise-hierarchical particle count method suitable for the implementation of the unified gas-kinetic wave–particle method on graphics processing unit devices. Phys. Fluids 2024, 36, 101703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Cao, J.; Ji, X.; Xu, K. Adaptive wave-particle decomposition in UGKWP method for high-speed flow simulations. Adv. Aerodyn. 2023, 5, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).