Abstract

Designing Low Earth Orbit (LEO) constellations for the continuous, collaborative observation of space objects in MEO/GEO is a complex optimization task, frequently limited by prohibitive computational costs. This study introduces an efficient surrogate-based framework to overcome this challenge. Our approach integrates Optimized Latin Hypercube Sampling (OLHS) with a Radial Basis Function (RBF) model to minimize the required number of satellites. In a comprehensive case study targeting 18 diverse space objects—including communication satellites in GEO (e.g., EUTELSAT, ANIK) and navigation satellites in MEO/IGSO from GPS, Galileo, and BeiDou constellations—the method proved highly effective and scalable. It successfully designed a 208-satellite Walker constellation that provides 100% continuous coverage over a 36-h period. Furthermore, the design ensures that each target is simultaneously observed by at least three satellites at all times. A key finding is the method’s remarkable efficiency and scalability: the optimal solution for this larger problem was found using only 46 high-fidelity function evaluations, maintaining a computational time that was 5–8 times faster than traditional global optimization algorithms. This research demonstrates that surrogate-assisted optimization can drastically lower the computational barrier in constellation design, offering a powerful tool for building cost-effective and robust Space Situational Awareness (SSA) systems.

1. Introduction

Space objects refer to all objects in outer space, including non-functional spacecraft, rocket upper stages, and space debris [1]. With the rapid advancement of space technology worldwide, the orbital environment around Earth is becoming increasingly congested, populated by man-made satellites, rocket bodies, and other forms of space junk. Effectively monitoring and avoiding these on-orbit objects are crucial for the continued expansion of human space exploration and technological development [2]. According to data from NASA’s Orbital Debris Program Office, as of 2023, the number of medium- and high-orbit space objects larger than 10 cm in diameter exceeds 42,000. The target density in the Geosynchronous Earth Orbit (GEO) belt is as high as 1.8 objects per square degree [3], with an annual collision probability of approximately 2.3 × 10−4 [4]. These space objects not only severely interfere with the normal operation of spacecraft but also pose significant obstacles to space exploration and development activities.

Within the framework of SSA [5], Space-Based Space Surveillance (SBSS) [6] systems are paramount. They can overcome the limitations of ground-based surveillance systems, which are constrained by atmospheric conditions and geographical distribution, enabling all-weather, wide-area monitoring missions. The United States has developed advanced SBSS systems, establishing a series of sophisticated satellite platforms. For example, the Midcourse Space Experiment (MSX) satellite, launched in 1996 [7], validated space-based optical space object surveillance techniques, laying a solid foundation for subsequent system development. The SBSS program, initiated in 2002, launched the “Pathfinder” satellite (SBSS-1) in 2010, significantly enhancing the US’s capability for space awareness. Furthermore, systems such as the Geosynchronous Space Situational Awareness Program (GSSAP) [8] and the SBSS Block 10 system (formerly EAGLE) have demonstrated an exceptional performance in wide-area spatial coverage and close-in inspection.

However, existing space object monitoring methods and technologies face numerous limitations. Ground-based monitoring systems are constrained by atmospheric turbulence and geographical distribution, resulting in an average daily observational blind period of up to 6.8 h for GEO targets, which struggles to meet the demands of real-time situational awareness. While space-based systems offer certain advantages, challenges remain in terms of target detection accuracy, signal processing complexity, and constellation optimization design [9]. In the field of constellation design, most existing space-based constellation research focuses on Earth observation or communication services, leaving a gap domestically in optimization studies specifically targeting space object surveillance. Internationally, the United States has validated its capability for space-based multi-satellite collaborative surveillance through initiatives like the STARE constellation [10] and the Starshield program, but the technical details remain undisclosed.

Addressing the aforementioned challenges, this paper proposes a low-Earth orbit (LEO) Walker constellation design method based on a surrogate optimization algorithm. The objective is to minimize the number of required LEO satellites while satisfying the requirements for continuous monitoring of space objects and ensuring that at least three LEO satellites simultaneously observe each space target. The main contributions of this work are as follows:

- (1)

- The application of a surrogate optimization algorithm to LEO Walker constellation design, integrating Optimal Latin Hypercube Sampling (OLHS) [11] and a Radial Basis Function (RBF) [12] surrogate model to effectively reduce computational load, enhance optimization efficiency and precision, and avoid local optima.

- (2)

- Modeling of continuous temporal coverage: The establishment of a coverage effectiveness evaluation model under spatiotemporal distributions of multiple targets in different orbits, with the optimization goal of minimizing the number of satellites, supporting the dynamic adjustment of Walker-Delta constellation parameters.

The effectiveness and scalability of the design are validated through comprehensive simulation experiments involving 18 diverse space objects [13,14]. The results demonstrate that the optimized constellation achieves 100% continuous coverage over a 36-h period. This study addresses the challenge of achieving full-time monitoring of medium- and high-orbit space objects using a LEO constellation, providing an efficient and scalable design tool for space situational awareness systems and supporting critical tasks such as debris avoidance and on-orbit servicing.

The structure of this paper is as follows: Section 2 details the construction of the RBF surrogate model and the OLHS method. Section 3 establishes the coverage model of the Walker constellation for space objects and defines the optimization problem. Section 4 verifies the reliability and effectiveness of the design through simulation experiments and comparative analysis. Section 5 concludes the paper and discusses future research directions.

2. Radial Basis Function Surrogate Model

2.1. Latin Hypercube Design

Latin Hypercube Sampling (LHS), proposed by McKay et al. in 1979 [15], is a multi-dimensional stratified sampling method. Its core procedure consists of the following steps: (1) Divide each dimension of the n-dimensional design space into mutually exclusive and equiprobable intervals; (2) randomly select one sample point within each interval of every dimension, resulting in m candidate points per dimension; (3) construct m n-dimensional vectors through random combination, ensuring each interval of every dimension is sampled exactly once. This method guarantees projection uniformity, meaning each interval of any dimension contains exactly one sample point. However, the random pairing of dimensions can result in a poor spatial distribution of the samples across the entire n-dimensional space.

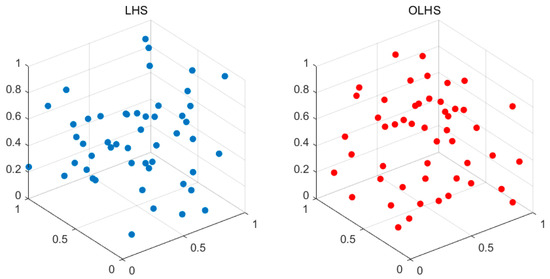

To address this limitation, Morris et al. proposed Optimal Latin Hypercube Sampling (OLHS), which enhances spatial uniformity through a dual optimization criterion: maximizing the minimum distance between samples and minimizing the maximum distance. As shown in Figure 1, a comparative experiment involving three variables and 20 samples demonstrates that OLHS significantly improves the spatial distribution of samples while maintaining projection uniformity. Although coordinate projections exhibit equally spaced characteristics in both methods, OLHS achieves superior spatial dispersion through systematic optimization. This characteristic makes it particularly valuable for engineering design applications.

Figure 1.

Comparison of sample point distributions between LHS and OLHS.

2.2. Radial Basis Function

The radial basis function (RBF) model is an interpolation model constructed through the linear combination of radial basis kernel functions [16], where the radial basis kernel function is a type of function that takes the Euclidean distance between the test point and the sample points as its independent variable. The fundamental concept of the RBF model is to determine a set of sample points, equal in number to the intended sample size; use these points as centers; and employ the radial basis kernel functions as basis functions. The objective function value at a test point x is then computed through the linear combination of these basis functions. By employing the Euclidean distance, the radial basis kernel function effectively transforms a multidimensional problem into a one-dimensional problem with Euclidean distance as the independent variable. The relationship between the input variables and the predicted response in the radial basis kernel function model can be expressed as follows:

In the formula

represents the weight coefficient, and

denotes the radial basis kernel function, where

is the Euclidean distance between the test point and the sample point. The weight coefficient vector

can be uniquely determined by the interpolation condition

Here, the matrix

, and

is a column vector composed of the response values at the sample points. Iterative methods may be employed to achieve improved fitting performance. Commonly used radial basis kernel functions include the linear kernel (L), cubic kernel (C), thin plate spline (TPS), Gaussian kernel (G), multi-quadratic (MQ) [17], and inverse multi-quadratic (IMQ) kernels, among others. Based on the comparative study by Franke [18], the MQ kernel demonstrates superior performance in terms of accuracy, stability, and computational efficiency. Therefore, the MQ kernel is adopted in this work for constructing the RBF surrogate model. Table 1 lists the commonly used radial basis kernel functions.

Table 1.

Commonly Used Radial Basis Kernel Functions.

2.3. Surrogate-Based Optimization Algorithm

The surrogate-based optimization algorithm seeks the global optimum of the objective function through iterative alternation between two main phases [5]: the surrogate construction phase and the minimum search phase.

- (1)

- Surrogate Construction Phase;

This phase aims to generate a set of random points within the bounded parameter space via Optimal Latin Hypercube Sampling (OLHS). The objective function values at these points are computed and used to construct a Radial Basis Function (RBF) interpolation model, which serves as an approximate surrogate function of the objective function. This process effectively reduces the frequency of direct objective function evaluations, thereby improving overall optimization efficiency [19].

- (2)

- Minimum Search Phase;

Within the bounded domain, multiple points are randomly sampled. A merit function is estimated based on the surrogate values at these points and their Euclidean distances to the known sampled points of the objective function. The global optimum of this merit function is selected as the adaptive point, at which the true objective function value is computed to update the surrogate model. The algorithm then returns to the minimum search phase and iterates. Under certain conditions—specifically, when all sample points cluster within a predefined neighborhood of known values—the algorithm triggers a surrogate reset, switching back from the minimum search phase to the surrogate construction phase. This ensures comprehensiveness and accuracy of the search. A detailed flowchart of the algorithm is shown in Algorithm 1. The key components of the algorithm are described below:

| Algorithm 1: Surrogate-based Optimization Algorithm |

| Input: Objective function

, parameter bounds

, initial sampling size

, termination criteria, initial scale value, weight parameter

Output: Optimal solution with minimum value, or None if no solution found. |

|

① Objective Function: The true model whose global optimum the algorithm aims to find. As the objective function may be unknown, computationally expensive, or time-consuming to evaluate, it is approximated via a surrogate function.

② Surrogate Function: Serves as an approximation of the objective function. This paper employs an RBF interpolation model to construct the surrogate, reducing the number of direct objective function evaluations and improving optimization efficiency.

③ Incumbent Point: Refers to the point with the smallest objective function value since the last surrogate reset. It serves as a key reference during the optimization process.

④ Best Point: The point with the smallest objective function value among all evaluations since the algorithm started. Upon termination, this point is taken as the final global optimum.

⑤ Random Points: Generated from a pseudorandom sequence during the surrogate construction phase. These points are scaled and shifted to ensure they lie within the specified bounds. The objective function is evaluated at these points to build the surrogate.

⑥ Adaptive Point: Determined during the minimum search phase. The algorithm evaluates the true objective function at this point to update the surrogate and guide subsequent search directions.

⑦ Merit Function: Balances two competing tasks: minimizing the surrogate and exploring the search space [20]. It is defined as

where

Here, the merit function is a weighted sum of two competing terms designed to balance local exploitation and global exploration. The components are defined as follows:

: This term represents the predicted value of the objective function at a candidate point

, as computed by the RBF surrogate model. It serves as a computationally cheap approximation of the true, expensive objective function.

: This is the Euclidean distance from the candidate point

to its nearest neighbor in the set of existing, previously evaluated sample points, quantifying how far

is from known regions.

and

: These are the scaled surrogate value and scaled distance, respectively. The scaling parameters

and

are the minimum and maximum surrogate values (

) observed across all existing sample points where the true objective function has been evaluated. Similarly,

and

are the minimum and maximum nearest-neighbor distances (

) calculated over the current batch of candidate points being considered. This dynamic scaling normalizes the two objectives at each search step.

The parameter

is a dynamic weight that controls the trade-off between minimizing the surrogate and exploring the search space. To ensure a robust search that systematically alternates between these objectives, we employ a cyclic weighting strategy where

iterates through the predefined set of values: {0.15, 0.35, 0.65, 0.9}. A smaller

(e.g., 0.15) places more emphasis on the distance term, promoting exploration of new regions. Conversely, a large

(e.g., 0.9) emphasizes surrogate minimization, guiding the search toward the surrogate’s predicted minimum and thus promoting exploitation. This strategy prevents premature convergence and facilitates a comprehensive search of the parameter space.

⑧ Sampling Points: Used to evaluate the merit function during the minimum search phase. The results from these points help assess potential minima and guide the search direction.

⑨ Scale: A parameter used during the minimum search phase to quantify the search range, influencing the selection of adaptive points and balancing local versus global search.

⑩ Surrogate Reset: Occurs when all sample points cluster within a predefined range of known values. The algorithm switches from the minimum search phase back to the surrogate construction phase. This reset typically happens after the scale parameter has been reduced, concentrating all sample points around the incumbent point. This ensures thorough exploration of the region and helps avoid local optima [21].

The reliability of the optimization process and its robustness against convergence to local optima are ensured through several key mechanisms inherent in the algorithm’s design:

Balanced Exploration and Exploitation: The cyclic weighting strategy of the merit function (ω ∈ {0.15, 0.35, 0.65, 0.9}) systematically alternates between exploring undiscovered regions of the design space and refining solutions in promising areas, preventing premature convergence.

Surrogate Reset Mechanism: This acts as a global safeguard. When the search is deemed to be overly localized (all sample points cluster near the incumbent), the algorithm discards the current surrogate and rebuilds it from a new, space-filling OLHS sample. This effectively “restarts” the global search, mitigating the risk of being trapped in a local optimum.

Risk-Averse Adaptive Sampling: The selection of the next point for expensive evaluation is not solely based on the surrogate’s predicted optimum (which might be inaccurate) but on a balanced merit function that explicitly rewards points that are both promising and far from previously evaluated sites. This forces the algorithm to periodically verify its model in unexplored regions, reducing the risk of false convergence.

The selection of the adaptive point

, a critical step in the minimum search phase, is performed through a sampling-based approach rather than a separate optimization of the merit function itself. As outlined in the algorithm (), a large number of new candidate points are first randomly sampled across the entire search domain. The merit function, defined in Equation (2), is then evaluated for each of these randomly generated points.

The adaptive point

is simply chosen as the candidate point that yields the minimum value of the merit function from this evaluated set. This discrete sampling approach avoids the computational overhead of running a secondary, continuous optimization algorithm on the merit function, ensuring that the search for the next evaluation point remains efficient while still effectively balancing exploration and exploitation based on the merit function’s guidance.

3. Constellation Optimization Design Based on RBF Surrogate Model

This paper selects the Radial Basis Function (RBF) surrogate model for the design of a low-Earth orbit (LEO) Walker constellation due to its strong nonlinear mapping capability, which enables effective handling of complex optimization problems [22]. Its training process is simple and efficient, reducing computational costs and improving optimization efficiency. The model exhibits local approximation properties, allowing it to accurately capture local variations in parameters. Additionally, it demonstrates strong adaptability to high-dimensional data, making it well-suited for constellation design problems involving multiple parameters. Compared to traditional optimization algorithms such as gradient descent and Newton’s method [23], the RBF model more effectively avoids local optima and does not require derivative information of the objective function. In contrast to polynomial surrogate models, it offers higher accuracy and better generalization capability in high-dimensional, nonlinear problems [24]. Compared to neural networks, the RBF model is simpler to train and computationally more efficient [25]. Furthermore, relative to global optimization algorithms such as genetic algorithms and particle swarm optimization, the RBF surrogate-based optimization algorithm combines characteristics of both local and global search, significantly improving computational efficiency while ensuring global optimization performance [26].

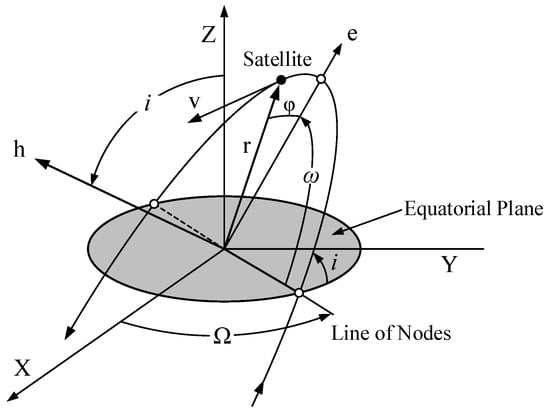

Under Earth’s gravitational influence, satellites orbit the Earth’s center of mass at specific velocities. Except for geostationary satellites, other satellites cannot remain fixed directly above a single point on the Earth’s surface. Their coverage areas change dynamically over time, a behavior strictly governed by parameters such as orbital altitude and inclination. Therefore, a single satellite generally cannot meet the monitoring requirements for medium- and high-orbit space targets. Given that satellite motion in orbit follows certain temporal and spatial patterns, collaborative operations using multiple satellites can achieve broader regional coverage and enhance coverage characteristics over specific areas. This ensures that target regions are monitored according to mission-specified time intervals or coverage frequency. The basic orbital parameters of a satellite are illustrated in Figure 2, and these parameters will be described in detail in the following section.

Figure 2.

Basic Satellite Orbital Parameters.

When designing satellite constellations for specific space mission requirements, the diversity and wide variability of satellite orbital parameters render the solution process considerably complex. Furthermore, the selection of different orbit types can significantly influence the final performance of the constellation design. Therefore, a common practice is to first select an appropriate constellation configuration and then proceed with design and optimization based on this foundation, thereby reducing the difficulty of the solution process. The constellation configuration specifies the spatial arrangement of satellites within the constellation, the types of orbits used, and the relational patterns among the satellites. Currently, in the field of satellite constellation design, the Walker constellation configuration is widely adopted. The following section will provide an in-depth discussion of this configuration.

3.1. Walker-Delta Constellation Configuration

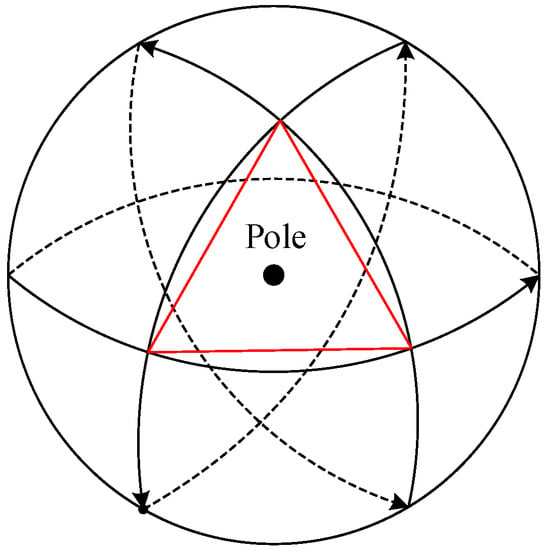

The Walker constellation configuration is a type of inclined symmetric circular-orbit satellite constellation, proposed by John Walker of the British Aerospace Corporation. This configuration includes two special forms: the Delta pattern and the Rosette pattern [27,28]. Among these, the Walker-Delta constellation, as the classical form, consists of three satellite orbital planes. When viewed from the direction of the polar axis, the ground track intersections of the satellites in each orbital plane form a pattern resembling the Greek letter Delta (Δ), as illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Schematic Diagram of Walker-Delta Constellation.

The Walker constellation configuration is composed of multiple orbital planes sharing the same orbital altitude and inclination. Satellites within each orbital plane are equally spaced and uniformly distributed, enabling this architecture to provide stable surveillance coverage over the target service area.

For each Walker constellation, the following seven parameters must be defined: orbital altitude H, orbital inclination I, number of satellites per plane N, number of orbital planes M, phase factor P, right ascension of the ascending node R, and argument of latitude A [29]. The parameter set can be expressed as:

The phase factor P, in particular, takes integer values in the range:

.

In practical applications, appropriate constraints can be imposed on these parameters according to specific design objectives, thereby simplifying computations and enhancing optimization efficiency. For instance, the orbital inclination may be constrained to meet specific regional coverage requirements, while the number of satellites may be limited by budget or launch capabilities. By applying such constraints rationally, an optimized constellation design can be achieved while fulfilling mission requirements.

3.2. Coverage Modeling and Optimization of Walker-Delta Constellation for Space Targets

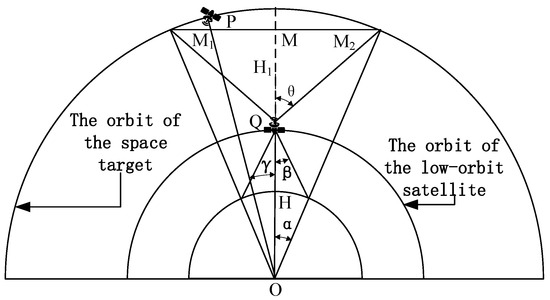

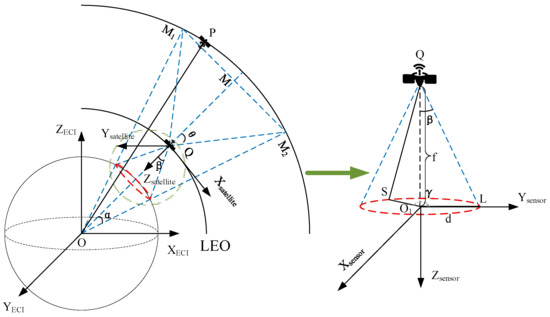

When designing a low-Earth orbit (LEO) satellite constellation for monitoring medium- and high-orbit space objects [30], its primary task is to efficiently observe these targets to support critical missions such as space situational awareness and debris avoidance. During the detection of space objects, LEO satellites operate against the backdrop of deep space. To simplify the modeling, the optical axis of the sensor payload on the LEO satellites is assumed to be aligned along the geocentric radial direction (pointing away from the Earth’s center). Their detection range is illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Schematic Diagram of LEO Satellite Detection of Space Objects.

Assuming the sensor’s half-angle field of view of the LEO satellite is within the range

, the corresponding visible region for space targets is the arc segment

shown in the figure. The visibility condition between the LEO satellite Q and the space target P is given by [31]:

with the following relationships:

where O is the center of the Earth, and M is the midpoint of the chord

on the orbit where the space target P is located.

Using Equation (7), the

can be determined. To simplify the visibility condition, when the sub-point of the space target lies within the cone formed by the normal to the orbital plane of LEO satellite Q, satellite Q is considered able to monitor target P at that time. This simplification effectively transforms the three-dimensional line-of-sight problem into a two-dimensional sub-satellite point inclusion problem. This simplification effectively transforms the three-dimensional (3D) line-of-sight problem into a more computationally efficient two-dimensional (2D) sub-satellite point inclusion problem. It is crucial to distinguish between the fundamental 3D geometric condition and its 2D projection.

In the 3D Earth-centered frame, the visibility condition is governed solely by the Earth obstruction and the sensor’s boresight and is inherently independent of latitude. In the adopted 2D projection model, the equivalent sensor coverage area on the Earth’s surface deforms from a circle to an ellipse at higher latitudes. This deformation is an artifact of the map projection and represents the primary approximation introduced by our model.

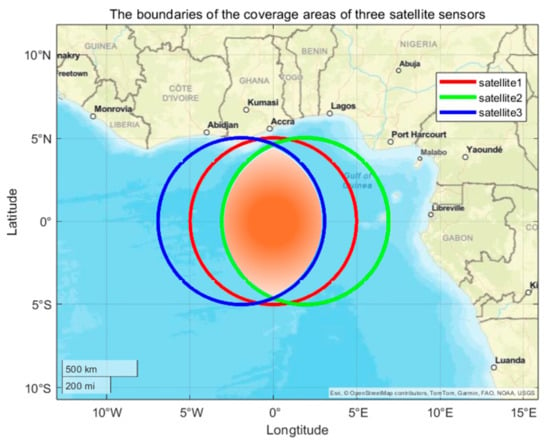

The circular areas shown in Figure 5 are for illustrative purposes to demonstrate the principle of multi-satellite overlap in a simplified, low-latitude context.the orange areas specifically illustrate the overlapping coverage of three satellite sensors. (The modified Figure 5 can be placed here.)

Figure 5.

Feasible Region for Simultaneous Multi-Satellite Surveillance (at least 3 satellites).

The field of view of the LEO satellite for monitoring the space target, when projected onto the Earth’s surface, corresponds to a sensor half-angle denoted as

in Figure 4. Combining this with Equation (7), we obtain:

where

is the distance from the Earth’s center to the boundary of the equivalent sensor coverage region.

A space target is considered detectable by LEO satellite Q if its sub-satellite point falls within the equivalent field of view of satellite Q.

When calculating the orbital period, the influence of Earth’s perturbation must be taken into account. In this section, a fitted J2 perturbation model is adopted. Let

denote the Earth’s rotational angular velocity. The formula for calculating the satellite’s subsatellite point trajectory is as follows:

The declination of the subsatellite point is then:

In general, the semi-major axis

, eccentricity

, and inclination

remain constant. However, the right ascension of the ascending node

, argument of perigee

, and mean anomaly

vary with time:

The sub-satellite point tracks of adjacent orbital periods coincide, with a longitude difference of:

In Equations (9) to (14),

denotes the right ascension of the ascending node,

represents the mean motion,

is the Earth’s equatorial radius, a is the semi-major axis,

is the eccentricity,

is the inclination,

is the argument of perigee,

is the mean anomaly,

is the Earth’s rotational angular velocity, and

is the perturbation coefficient. Therefore, given the six classical orbital elements and time at

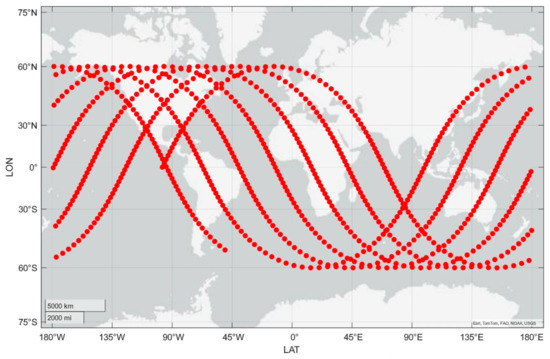

, the subsatellite point trajectory can be computed [32]. Using Equations (9)–(14), the ground track of a satellite with a semi-major axis of 7500 km, inclination of 60, RAAN of 37, and true anomaly, eccentricity, and argument of perigee all equal to zero, sampled at 60-s intervals over 36 h, is illustrated in the Figure 6 (The modified Figure 6 can be placed here.)

Figure 6.

Schematic Diagram of the 12-H Satellite Ground Track.

As shown in Figure 7,

is the projection point on the ground corresponding to the center of the sensor’s field of view, and point

is a point on the boundary of this field. By rotating the vector

is a point on the boundary of this field. By rotating the vector

around axis

, the observation vector

to any arbitrary point can be obtained. Let

and

, so that

, Then, the line-of-sight vector in the sensor coordinate system is given by:

The normalized line-of-sight vector is:

where

is the intermediate angle within the sensor’s field of view, ranging from

to

. Its specific value depends on the number of boundary points

of the sensor; a larger

results in a denser distribution of points projected from the sensor boundary onto the Earth’s surface.

Figure 7 illustrates schematic diagrams in both the Earth-Centered Inertial (ECI) coordinate system and the satellite’s orbital coordinate system, with the right panel specifically depicting the sensor coverage of the low-Earth orbit satellite.

The observation vector is transformed from the sensor coordinate system to the satellite orbital coordinate system through attitude rotations defined by the yaw angle

, pitch angle

, and roll angle

[33]. The resulting observation vector in the satellite orbital frame is thus given by:

The transformation from the satellite orbital coordinate system to the Earth-Centered Inertial (ECI) coordinate system is achieved using a projection method. Let the satellite’s position vector in the ECI frame be

and its velocity vector be

The transformation matrix

is constructed from three orthogonal unit vectors defined as follows:

The z-unit vector is the radial unit vector pointing in the direction opposite to the position vector (i.e., toward the Earth’s center):

The y-unit vector is perpendicular to the orbital plane, obtained by normalizing the cross product of

and the velocity vector

:

The x-unit vector completes the right-handed coordinate system:

Finally, the transformation matrix is formed by arranging these three unit vectors as rows:

The transformation from the Earth-Centered Inertial (ECI) frame to the Earth-Centered Earth-Fixed (ECEF) frame must account for precession, nutation, polar motion [34], and Greenwich Sidereal Time. For a detailed implementation procedure, refer to [35].

After obtaining the projected point position (X, Y, Z) in the Earth-Centered, Earth-Fixed (ECEF) coordinate system, it is converted to longitude (L), latitude (B), and height (H) in the geodetic coordinate system. The height (H) is then set to zero to obtain the longitude and latitude of the projected point in the geodetic coordinate system. The transformation relations are given by:

where

,,

is the semi-major axis of the Earth, and

is the eccentricity.

To ensure reliable surveillance of space targets, it is required that at least three low-Earth orbit (LEO) satellites simultaneously monitor the target throughout the observation period [36]. As illustrated in Figure 8, the diagram shows the projected coverage areas on longitude and latitude coordinates for three LEO satellites (parameters) observing targets at the same orbital altitude. The orange shaded region represents the feasible zone where stable surveillance of the space target is achieved.

Let

denote the ground-projected coverage area of the

-th LEO satellite in a Walker-Delta constellation of

satellites, monitoring a space target at altitude

. The number of satellites visible to the space target can then be expressed as:

Figure 7.

Schematic Diagram of LEO Satellite Coverage in the Sensor Coordinate System.

Figure 8.

Simulation Results for Upper Limits of Satellites per Plane and Number of Orbital Planes.

Here, is an indicator function defined as:

Based on the parameters required for the Walker-Delta constellation configuration and the coverage requirements for space targets, the constellation design problem is formulated as the following optimization problem:

4. Simulation Experiments and Result Analysis

4.1. Simulation Experiments

In the simulation validation phase of this study, Two-Line Element (TLE) files for 18 space targets were obtained from public data sources [37]. The orbital parameters of this expanded target set are summarized in Table 2. Since the RBF surrogate-based optimization algorithm requires optimized parameters to be defined within closed intervals, the orbital altitude of the LEO satellites was constrained between 500 km and 1500 km according to mission requirements.

Table 2.

Orbital Parameters of the 18 Space Targets.

To define the search space for the constellation parameters, the upper bounds for the number of satellites per orbital plane

and the number of orbital planes

were investigated through preliminary simulation tests. The results indicated that a configuration with

and

was sufficient to satisfy the requirement for continuous triple-coverage of all 18 space targets throughout the 36-h observation period. Therefore, the upper limits of

and

were set to 50 as input constraints for the surrogate optimization algorithm. This choice not only ensures the feasibility and computational stability of the optimization process but also provides sufficient design space for algorithm exploration. Thus, the optimization objective is to minimize the total number of LEO satellites while maintaining the required coverage performance. The constraints applied to the Walker-Delta constellation parameters comply with the requirements of the RBF surrogate optimization method, ensuring both feasibility and effectiveness of the solution.

where

denotes the orbital radius,

the argument of latitude,

the orbital inclination,

the phase factor,

the number of orbital planes,

the right ascension of the ascending node, and

the number of satellites per plane. The above constraints on the Walker-Delta constellation parameters satisfy the requirements of the RBF surrogate optimization algorithm.

The 18 space targets listed in Table 2 comprise a diverse set of objects crucial for validating the proposed methodology. This ensemble includes geostationary (GEO) communication satellites (e.g., EUTELSAT, ANIK, AMC, NSS) known for their high orbital stability and service continuity in broadcasting and data transmission. It also incorporates navigation satellites from multiple global systems—including the American GPS, European Galileo, and Chinese BeiDou constellations—which operate in medium Earth orbit (MEO) and inclined geosynchronous orbit (IGSO) to provide precise positioning, navigation, and timing services worldwide. This selection robustly represents predominant medium and high Earth orbit architectures, thereby ensuring a rigorous test for the generalizability of the constellation design.

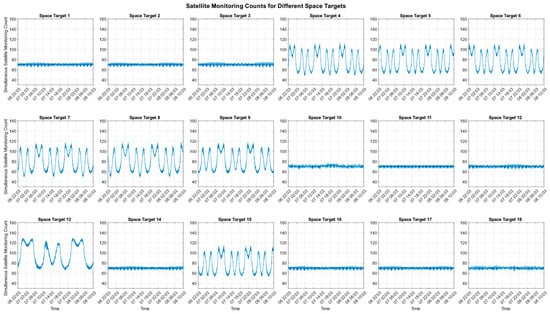

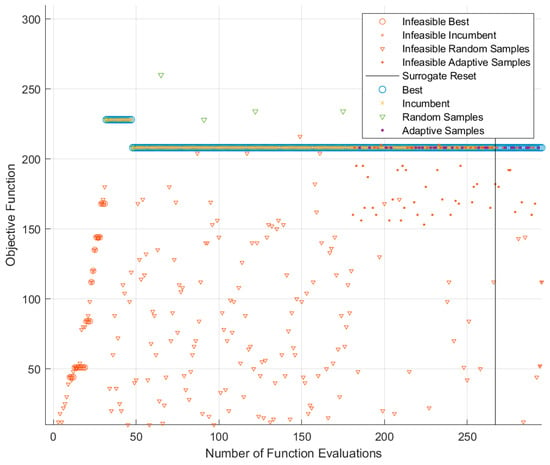

The simulation was initialized at 22:00 UTC on 6 March 2022, with a total duration of 36 h. Satellite orbits were propagated using the SGP4 model. The sensor payloads on the LEO satellites were modeled with a half-angle field of view of 25°, oriented radially away from the geocenter, and the coverage condition was sampled at 60-s intervals. The optimization process concluded after 300 iterations, with its convergence behavior detailed in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Surrogate Optimization Process.

The optimization algorithm exhibited a highly efficient convergence profile. The global optimum was first located at the 46th iteration. The subsequent iterations served to validate the robustness of this solution and refine the surrogate model in its vicinity. The “surrogate reset” mechanism was systematically triggered at iteration 269, a consequence of the search having concentrated sufficiently around the optimum without finding improvements. This sequence of events—rapid discovery followed by sustained validation and a final convergence check—underscores the reliability of the final parameters presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Constellation Parameters Optimized by the RBF Surrogate Model.

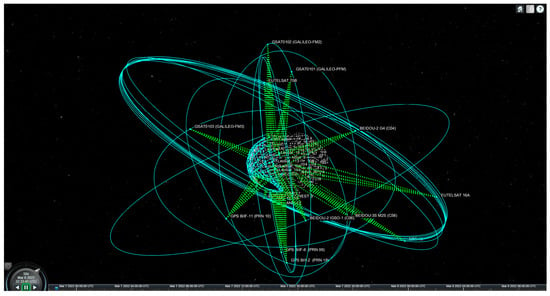

Using MATLAB Aerospace Toolbox, a high-fidelity simulation scenario was constructed based on the low-Earth orbit satellite constellation parameters provided in Table 3. These parameters include orbital altitude, inclination, phase factor, and constellation geometry, among other critical variables. By accurately importing these parameters into the simulation model, a constellation model was generated that closely mirrored real-world operational conditions.

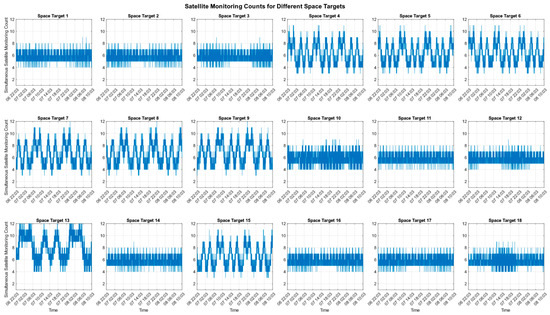

Figure 10 clearly depicts the coverage status of each space object over the entire simulation period. Detailed analysis of the simulation data indicates that the designed LEO satellite constellation achieves 100% continuous coverage for all targets throughout the entire simulation period. Moreover, at any given time, each space object is simultaneously covered by at least three LEO satellites, fully satisfying the requirements for multi-satellite collaborative surveillance. A schematic diagram of the simulation scenario is presented in Figure 11.

Figure 10.

Coverage Performance of the Optimized Walker Constellation for the 18 Space Targets.

Figure 11.

Simulation Scenario of Coverage Performance for the 18 Space Targets.

4.2. Comparative Performance Analysis

To further validate the computational efficiency and superiority of the proposed RBF surrogate-based optimization algorithm, a comparative study was conducted against three widely used global optimization algorithms: Genetic Algorithm (GA) [38], Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) [39], and Simulated Annealing (SA) [40]. All algorithms were implemented in MATLAB R2024a and executed on a high-performance computing platform equipped with an Intel Xeon Silver 421R CPU (@ 2.40 GHz) and 128 GB of RAM, ensuring a consistent and fair hardware environment for all tests.

The objective of each algorithm was to minimize the total number of satellites in the Walker constellation while ensuring continuous triple-coverage of all 18 space targets over a 36-h period. The configuration of each algorithm was carefully tuned to balance exploration and exploitation capabilities:

The GA was configured with a population size of 20, a maximum of 50 generations, tournament selection with a size of 3, heuristic crossover, adaptive feasible mutation, and parallel computation enabled to enhance global search capability.

The PSO used a swarm size of 10, maximum iterations of 5, self-adjustment and social-adjustment weights of 1.49, and an inertia range of [0.4, 0.9], with parallel computation enabled.

The SA was set with a maximum of 10 iterations, 20 function evaluations, an initial temperature of 100, fast annealing function, exponential temperature decay, and detailed iterative output.

The convergence performance of each algorithm was evaluated based on the computational time required to reach a feasible solution of 208 satellites. The results are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Computational Time Comparison of Optimization Algorithms.

The proposed RBF surrogate-based optimization algorithm significantly outperformed all three traditional methods, converging to the optimal solution in only 3 h and 44 min, which was 5–8 times faster than the other algorithms. This remarkable efficiency stems from the surrogate model’s ability to approximate the expensive objective function with minimal high-fidelity evaluations, thereby drastically reducing computational overhead.

Moreover, the RBF-based method required only 46 high-fidelity evaluations to converge, whereas the population-based methods (GA and PSO) and the trajectory-based method (SA) typically require thousands of function evaluations, further justifying the use of surrogate models in complex constellation design problems.

To further validate the computational efficiency and scalability of the proposed RBF surrogate-based optimization algorithm under varying problem complexities, a comparative study was conducted. We investigated the time-to-first-convergence for scenarios with different numbers of space targets (12, 15, and 18) and different simulation durations (12 and 36 h). The objective was to find the minimal satellite constellation that satisfied the continuous triple-coverage requirement. The results, summarized in Table 5, demonstrate the algorithm’s consistent and efficient performance.

Table 5.

Computational Time to First Convergence for Different Problem Scales.

The scalability analysis in Table 5 demonstrates the algorithm’s consistent and efficient performance under increasing computational load. As the problem complexity grows—either by increasing the number of targets from 12 to 18 or by extending the simulation duration from 12 to 36 h—the computational time exhibits a manageable, sub-linear growth. This robust scalability confirms that the RBF surrogate model effectively abstracts the underlying coverage problem, allowing the optimizer to navigate larger and more complex design spaces without a prohibitive increase in cost. The predictable scaling relationship makes this approach particularly suitable for practical, high-fidelity constellation design tasks.

These results demonstrate that the RBF surrogate approach consistently delivers high-quality solutions with remarkable efficiency. Its robust scalability, validated by our analysis showing a sub-linear increase in computational time with problem size, makes it particularly suitable for the large-scale, computationally expensive problems prevalent in aerospace engineering.

5. Conclusions

This study proposed an efficient surrogate-based optimization framework for designing low-Earth orbit (LEO) Walker constellations to achieve continuous, collaborative monitoring of medium- and high-orbit space objects. By integrating a Radial Basis Function (RBF) surrogate model with Optimized Latin Hypercube Sampling (OLHS), the method significantly reduced computational costs while ensuring high-quality solutions. The framework’s effectiveness and scalability were rigorously validated through a comprehensive case study involving 18 diverse space targets over a 36-h period. Simulation results demonstrated that the optimized 208-satellite constellation successfully achieved 100% continuous coverage for all targets, with each target simultaneously observed by at least three satellites at any time, thereby fully meeting the stringent requirement for collaborative space surveillance.

The comparative analysis underscored the superior computational efficiency of the proposed approach. For the challenging 18-target scenario, the RBF-based algorithm converged to the optimal solution using only 46 high-fidelity evaluations, which was 5–8 times faster than traditional global optimization algorithms. This remarkable efficiency highlights the potential of surrogate models to enable practical optimization in the complex, high-dimensional design spaces typical of advanced aerospace engineering problems.

Despite its promising performance, the current method has certain limitations. The accuracy and efficiency of the RBF surrogate depend heavily on the quality and quantity of initial samples, which may vary across different problem settings. Additionally, the current coverage model assumes simplified sensor geometries and orbital perturbations, which could be refined to include more realistic environmental factors.

Future work will focus on the following directions:

- (1)

- Transitioning to a multi-objective optimization framework to explicitly trade-off satellite count against other critical metrics like cost and coverage robustness, particularly to mitigate performance degradation from potential satellite failures;

- (2)

- Incorporating higher-fidelity models, including realistic sensor pointing strategies, Earth obscuration, and advanced orbital perturbations beyond the effect, to improve simulation accuracy;

- (3)

- Further validating the scalability of the approach on even larger target sets and more diverse orbital regimes.

In summary, this research provides a robust, efficient, and scalable design tool for next-generation space situational awareness systems. It holds significant promise for enhancing critical capabilities in space debris monitoring, collision avoidance, and ensuring the sustainable development of space infrastructure.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.F. (You Fu); Methodology, Y.F. (You Fu); Software, Y.F. (You Fu); Formal analysis, Z.M.; Investigation, Y.F. (Youchen Fan) and L.Y.; Writing—original draft, Y.F. (You Fu); Writing—review & editing, Z.X. and Y.L.; Supervision, S.F.; Project administration, S.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key Laboratory of Space Target Awareness under Grant STA2024KJW0401.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this study are derived from the publicly available CELESTRAK database [37]. These data can be accessed directly from https://celestrak.org/NORAD/elements/ (accessed on 7 March 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Heiner, K. Space Debris: Models and Risk Analysis; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bombardelli, C.; Alessi, E.; Rossi, A.; Valsecchi, G. Environmental effect of space debris repositioning. Adv. Space Res. 2017, 60, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jah, M. Space Surveillance, Tracking, and Information Fusion for Space Domain Awareness; NATO STO-EN-SCI-292: Brussels, Belgium, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cowardin, H. Orbital Debris Quarterly News, August 2023. In Orbital Debris Quarterly News; NASA: Washington, DC, USA, 2023; Volume 27. [Google Scholar]

- Flohrer, T.; Krag, H. Space surveillance and tracking in ESA’s SSA programme. In Proceedings of the 7th European Conference on Space Debris, Darmstadt, Germany, 17–21 April 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Du, J.; Chen, J.; Li, B.; Sang, J. Tentative design of SBSS constellations for LEO debris catalog maintenance. Acta Astronaut. 2019, 155, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catron, K.M.; Wang, H.; Hu, G.; Shen, M.M.; Abate-Shen, C. Comparison of MSX-1 and MSX-2 suggests a molecular basis for functional redundancy. Mech. Dev. 1996, 55, 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.-l.; Wang, R.; Zhang, L.; Chen, X.; Chen, W.; Guo, J.-t.; Cai, S. On-orbit application research and imaging simulation analysis of GSSAP satellite. Infrared Laser Eng. 2023, 52, 20220759. [Google Scholar]

- Flohrer, T.; Peltonen, J.; Kramer, A.; Eronen, T.; Kuusela, J.; Riihonen, E.; Schildknecht, T.; Stöveken, E.; Valtonen, E.; Wokke, F. Space-based optical observations of space debris. In Proceedings of the 4th European Conference on Space Debris, Darmstadt, Germany, 18–20 April 2005; p. 165. [Google Scholar]

- Popowicz, A.; Pigulski, A.; Bernacki, K.; Kuschnig, R.; Pablo, H.; Ramiaramanantsoa, T.; Zocłońska, E.; Baade, D.; Handler, G.; Moffat, A. BRITE Constellation: Data processing and photometry. Astron. Astrophys. 2017, 605, A26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wansaseub, K.; Sleesongsom, S.; Panagant, N.; Pholdee, N.; Bureerat, S. Surrogate-assisted reliability optimisation of an aircraft wing with static and dynamic aeroelastic constraints. Int. J. Aeronaut. Space Sci. 2020, 21, 723–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, D.; Chen, J.; Zhang, H.; Shi, Y.; Wang, T. Intelligent prediction for digging load of hydraulic excavators based on RBF neural network. Measurement 2023, 206, 112210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aughey, R.J. Applications of GPS technologies to field sports. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2011, 6, 295–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenech, H.; Tomatis, A.; Amos, S.; Soumpholphakdy, V.; Serrano Merino, J.L. Eutelsat HTS systems. Int. J. Satell. Commun. Netw. 2016, 34, 503–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mckay, M.D.; Beckam, R.J.; Conover, W.J. A Comparison of Three Methods for Selecting Values of Input Variables in the Analysis of Output from a Computer Code. Technometrics 2000, 42, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhmann, M.D. Radial basis functions. Acta Numer. 2000, 9, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, R.L. Multiquadric equations of topography and other irregular surfaces. J. Geophys. Res. 1971, 76, 1905–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franke, R. Scattered data interpolation: Tests of some methods. Math. Comput. 1982, 38, 181–200. [Google Scholar]

- Bhosekar, A.; Ierapetritou, M. Advances in surrogate based modeling, feasibility analysis, and optimization: A review. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2018, 108, 250–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Qiu, H.; Gao, L.; Cai, X.; Jiang, C.; Chen, L. A surrogate-assisted particle swarm optimization algorithm based on efficient global optimization for expensive black-box problems. Eng. Optim. 2019, 51, 549–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, I.-B.; Park, D.; Choi, D.-H. Surrogate-based global optimization using an adaptive switching infill sampling criterion for expensive black-box functions. Struct. Multidiscip. Optim. 2018, 57, 1443–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koziel, S.; Leifsson, L. Surrogate-based aerodynamic shape optimization by variable-resolution models. AIAA J. 2013, 51, 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Du, W.; Qian, F. Multi-objective differential evolution with ranking-based mutation operator and its application in chemical process optimization. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 2014, 136, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozcanan, S.; Atahan, A.O. RBF surrogate model and EN1317 collision safety-based optimization of two guardrails. Struct. Multidiscip. Optim. 2019, 60, 343–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Yang, Z.; Ran, J.; Li, H. Multi-objective parameter optimization of turbine impeller based on RBF neural network and NSGA-II genetic algorithm. Energy Rep. 2021, 7, 584–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Zhang, Q.; Lin, Q.; Gao, W. A three-level radial basis function method for expensive optimization. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2021, 52, 5720–5731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrueco, J.; Montalban, J.; Iradier, E.; Angueira, P. Constellation design for future communication systems: A comprehensive survey. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 89778–89797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornara, S.; Beech, T.W.; Belló-Mora, M.; Janin, G. Satellite constellation mission analysis and design. Acta Astronaut. 2001, 48, 681–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.; Xu, Y.; Luo, R.; Li, Y.; Yuan, C. Low Earth orbit constellation design using a multi-objective genetic algorithm for GNSS reflectometry missions. Adv. Space Res. 2023, 71, 2357–2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Yang, L.; Chen, Q.; Yu, S.; Chen, X.; Zhao, Y. Design of a low earth orbit satellite constellation network for air traffic surveillance. J. Navig. 2020, 73, 1263–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineau, D.; Felicetti, L. Design of an optical system for a Multi-CubeSats debris surveillance mission. Acta Astronaut. 2023, 210, 535–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Bian, L.; Cao, Y.; Meng, Y.; Zhang, L. Design and analysis of Beidou global integrity system based on LEO augmentation. In China Satellite Navigation Conference; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 624–633. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Guo, J.; Qin, T.; Wang, J.; Cui, Z.; Han, P.; Bao, Q.; Li, X.; Meng, F.; Qi, B. Integrated modeling and analysis of the microvibration effects on the line-of-sight stability for the space laser communication terminal. Opt. Eng. 2024, 63, 024110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Hwang, S.S. Enhanced Real-Time Onboard Orbit Determination of LEO Satellites Using GPS Navigation Solutions with Signal Transit Time Correction. Aerospace 2025, 12, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Gu, D.; Ju, B.; Yao, J.; Duan, X.; Yi, D. Basic performance of BeiDou-2 navigation satellite system used in LEO satellites precise orbit determination. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2014, 27, 1251–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, S.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Chen, Y. Coverage Analysis for Elliptical-Orbit Satellites Based on 2-D Map. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2023, 59, 4223–4239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CELESTRAK. Available online: https://celestrak.org/ (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Holland, J.H. Genetic algorithms. Sci. Am. 1992, 267, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, J.; Eberhart, R. Particle swarm optimization. In Proceedings of the ICNN’95-International Conference on Neural Networks, Perth, WA, Australia, 27 November–1 December 1995; pp. 1942–1948. [Google Scholar]

- Van Laarhoven, P.J.; Aarts, E.H. Simulated annealing. In Simulated Annealing: Theory and Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1987; pp. 7–15. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).