Abstract

Life cycle impact assessment (LCA) provides a better understanding of the energy, water, and material input and evaluates any production system’s output impacts. LCA has been carried out on various crops and products across the world. Some countries, however, have none or only a few studies. Here, we present the results of a literature review, following the PRISMA protocol, of what has been done in LCA to help stakeholders in these regions to understand the environmental impact at different stages of a product. The published literature was examined using the Google Scholar database to synthesize LCA research on agricultural activities, and 74 studies were analyzed. The evaluated papers are extensively studied in order to comprehend the various impact categories involved in LCA. The study reveals that tomatoes and wheat were the major crops considered in LCA. The major environmental impacts, namely, human toxicity potential and terrestrial ecotoxicity potential, were the major focus. Furthermore, the most used impact methods were CML, ISO, and IPCC. It was also found that studies were most often conducted in the European sector since most models and databases are suited for European agri-food products. The literature review did not focus on a specific region or a crop. Consequently, many studies appeared while searching using the keywords. Notwithstanding such limitations, this review provides a valuable reference point for those practicing LCA.

1. Introduction

Food supply chains (FSCs) are very complex. There are many components involved in FSCs that process, produce, package, store, transfer, distribute, and market food products to final consumers [1]. Each element in the FSC process is essential, as in any other supply chain; a change in one component affects the others. The relationship between the food system and the economy, environment, and society is mentioned by some organizations and agencies, such as the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO), Institute of Medicine (IOM), and National Research Council (NRC), when they define the FSC [2]. Therefore, the most crucial question is as follows: Which food production system is more sustainable for the environment and communities?

There are many concerns about food resources and massive population growth, such as meeting the food demand for the world’s population, production, and food consumption [1]. The total crop production must double or increase by at least 70% to meet the increasing world population’s demand by 2050 [3]. Models have estimated that a 2.4% annual increase in crop yield is necessary to reach the 2050 demand [4]. The rise in food demand results in substantial energy and resource use by the food supply chain, leading to different environmental impacts. Many organizations have mentioned environmental impacts associated with food production, including the use of land, water, and climate change. Significant environmental challenges that humans face are primarily due to climate change and the predicted future shortage of fossil fuels [5]. Farming methods, fertilizers, pesticides, water pumping, tractors to prepare the land, and transport of the crops or final food products via railroads, trucks, airplanes, or ships can all impact the environment. Lastly, food processing and food preservation methods such as refrigeration and packaging also contribute to environmental damages. There are many production sectors involved in environmental impacts, and one of them is the agricultural sector.

According to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), agricultural chemicals and pesticide manufacturing are two of the 68 area source groups that account for 90% of the overall emissions of the 30 urban air toxins. For example, in 2018, greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from the agriculture economic sector accounted for 9.9% of total US greenhouse gas emissions. Furthermore, GHG from agriculture has increased by 10.1% since 1990 [6]. One of the direct greenhouse gases is nitrous oxide. Agricultural soil management operations such as synthetic and organic fertilizers and other cropping techniques, the management of manure, and the burning of agricultural wastes produce nitrous oxide. Agricultural soil management is the major source of N2O emissions in the US, accounting for around 75% of total emissions [7]. Agricultural soils, for example, are a major source of NOx pollution in California, with soil NOx emissions in the state’s Central Valley region being particularly high. Therefore, it is necessary to quantify the impacts of agricultural products along the food supply chain for sustainable production and consumption systems.

Since the number of operations in the food system is large and complex, many studies have used the life cycle assessment (LCA) methodology as a tool to study the overall resources used and the environmental impact of food products over its entire life cycle [8]. It is best known for its qualitative and quantitative analysis of a product’s environmental aspects over its whole life cycle [9]. Products in this context include both goods and services [10]. Environmental impacts in the LCA context refer to the adverse effects on the areas of concern such as the ecosystem, human health, and natural resources. Due to the limitation of raw materials and energy resources, LCA has been used since the 1960s to find solutions for sustainable productions [11].

Such research on the crop supply chain provides helpful information from the economic, social, and environmental perspectives. Using the LCA offers a better understanding of the energy, water, and material input and evaluates the outputs’ impacts. Thus, decision-makers in various fields can regulate new policies and use modern practices to improve the production supply chains. As observed in previous studies [9,12], many authors have used LCA to address environmental impacts over the entire life cycle of crops. However, the world’s largest industrial sector, the food supply chain, involves various crops and products that still need to be addressed by the LCA.

Therefore, this study’s broad objective is to synthesize the LCA studies relating to different environmental impacts from agricultural production to support stakeholders with decision-making. Besides, an in-depth analysis of the various steps involved in LCA is provided.

2. Materials and Methods

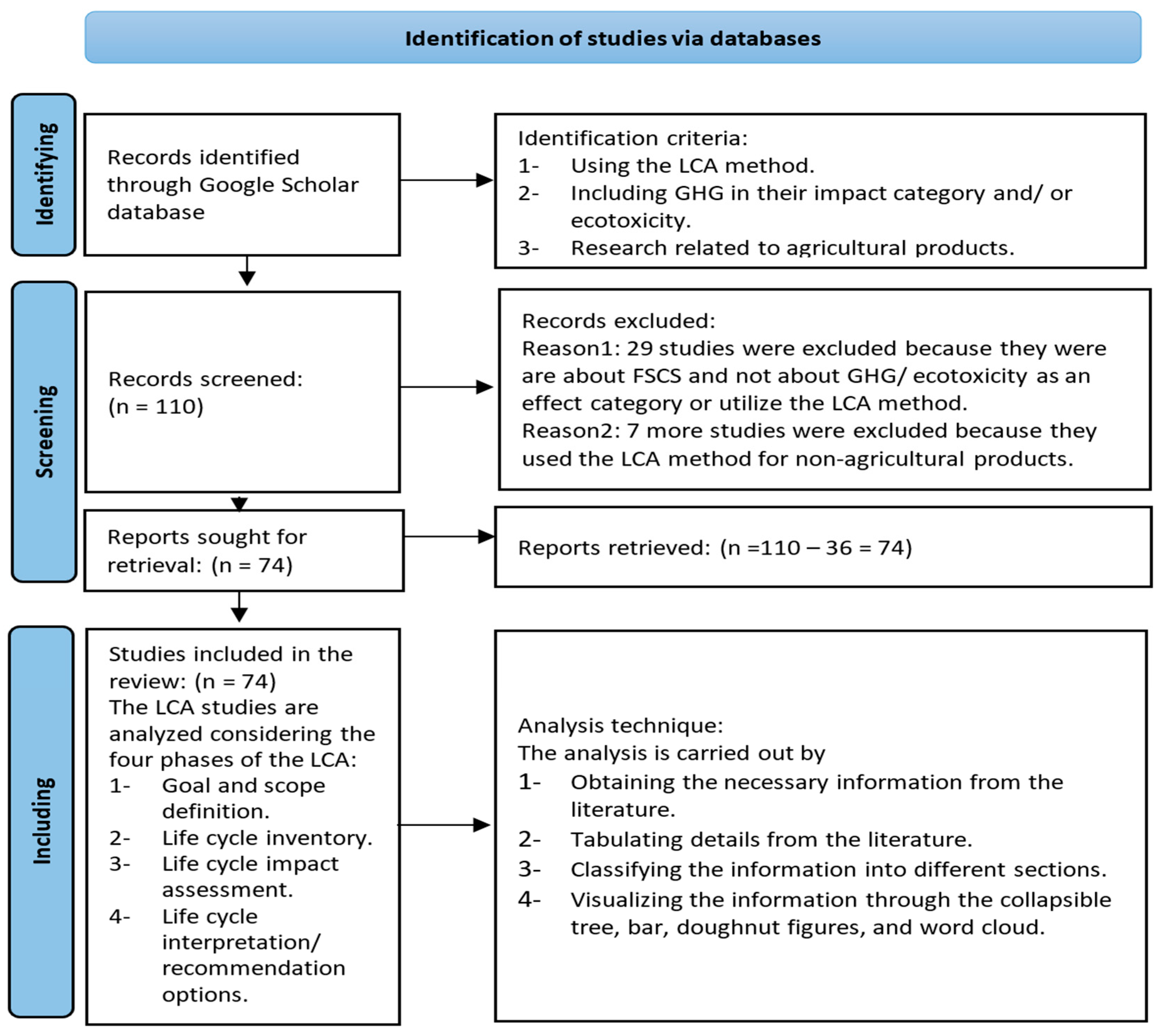

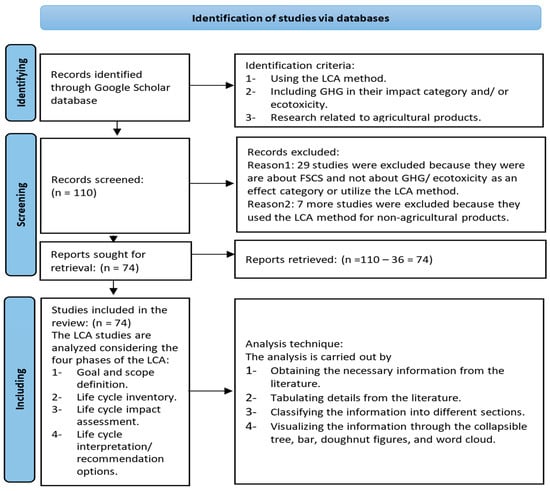

A literature review of published articles in international journals was undertaken using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) protocol to address the research aims.

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

The studies that applied the following selection criteria were chosen to reduce the number of articles: (i) using the LCA method, (ii) including GHG in their impact category and/or ecotoxicity, and (iii) researching agriculture products. A total of 36 research articles were eliminated because they were about FSCs and not GHG/ecotoxicity as an effect category, did not apply the LCA methodology, or utilized the LCA method for nonagricultural products. The LCA studies were analyzed extensively considering four phases of the LCA:

- Goal and scope definition,

- Life cycle inventory,

- Life cycle impact assessment,

- Life cycle interpretation/recommendation options.

2.2. Search Strategy

The literature review was done through the Google Scholar database. The keyword “LCA crop production” was used in the initial step, which yielded 59,100 studies as of July 2021. Later, more specific keywords were used, such as “agri-food supply chain and LCA” and “agri-food supply chain and GHG” combined with different fruit and vegetable products such as corn, peanuts, wheat, tomato, and apple. Nevertheless, the number of studies available remained enormous, the largest number of articles we got when we used the above key word with different crops was 7330, while the smallest number was 1820. A total of 110 articles were downloaded and analyzed. Twenty-nine studies were excluded because they were about FSCs and not about GHG/ecotoxicity as an effect category, or because they utilized the LCA method.

Furthermore, seven more were excluded because they used the LCA method for non-agricultural products. Accordingly, we ended up with 74 articles after applying the selection criteria. Figure 1 shows the steps used throughout the review and the inclusion criteria for the literature.

Figure 1.

Steps followed for review and the inclusion/exclusion criteria.

2.3. Categorization

The data obtained from the reviewed articles included the year of study, the aim of the study, and the different steps involved in LCA assessment, which are discussed in the results section. The timeline, different components, the approach of the LCA, application of the LCA concept in the impact analysis, and suggestions for a sustainable food system are all covered.

2.4. Data Analysis

The analysis was carried out by obtaining the necessary information from the literature, as given in Table A1 and Table A2 (Appendix A). Then, the information was visualized by means of collapsible trees, bar charts, doughnut figures, and word clouds after the information was classified into different result sections. Word clouds have evolved as a straightforward and visually appealing technique of text representation. They are used in a variety of contexts to offer an overview by reducing text down to the most frequently occurring terms. This is usually done statistically as a pure text summary [13,14]. Word clouds can be the initial step to refine the important concepts of results, which could save a great deal of time for other researchers since they already know where to start and the most common terms and ideas [15]. Pie and doughnut charts represent the relationship of parts with the whole [16,17]. Collapsible trees, bar charts, and doughnut figures are designed to provide greater numerical detail. Combining word clouds and bar charts allowed presenting both qualitative and quantitative information on LCA results.

The collapsible tree diagram was created with R software Version 3.6.1, and the bar and doughnut figures were created with Microsoft Excel. When making word cloud figures using the word cloud online website (https://www.jasondavies.com/wordcloud/ accessed on November 2021), each word must be typed correctly since the size and the color of the words in the figure are affected by the number of words entered. Therefore, it is essential to make sure that the number of entered words is accurate.

Lastly, the study was organized in IMRAD format, which is the most common format for scientific papers. The term represents the first letters of the words introduction, materials and methods, results, and discussion. IMRAD format facilitates knowledge acquisition and enables easy evaluation of an article [18]. Currently, IMRAD is used by the majority of academic publications. Before the IMRAD structure, all academic writing followed the IBC (introduction, body, and conclusion) pattern. The IMRAD format is only a more specified variant of the IBC format. [19]. It is important to keep in mind that no one journal follows a standard or consistent format. Each journal has its structure, yet they all have a guideline for authors [20].

3. Results

3.1. Snapshot of Selected Studies

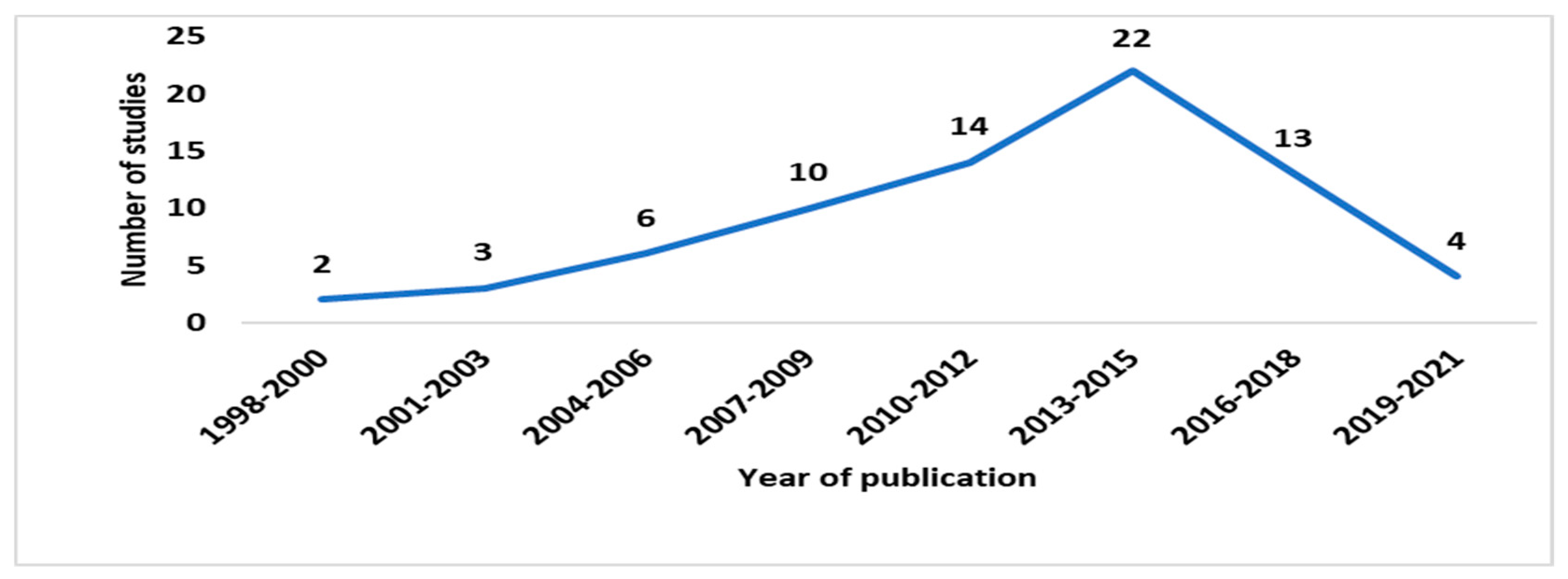

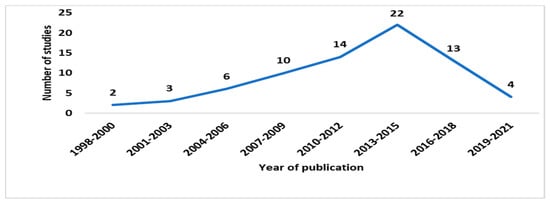

The characteristics of publications during 1998–2021 are displayed in Figure 2 to obtain an overview of LCA research. The number of publications per year has increased steadily since 2008, following development of the ISO standard.

Figure 2.

Frequency of studies related to LCA of agricultural production from 1998 to 2021 (n = 74).

Critiques of the ISO 14040 series pre-2006 were that LCA is too nascent [21], and ISO 14040 does not address uncertainty, weighting, valuation, and allocation [22].

The release of the latest version of the ISO 14040 standard in 2006 explains why LCA research is attracting more attention. Moreover, some have recently gone so far as to state that the ISO 14040: 2006 series “has proven a suitable tool for sustainability assessment” [13,14]. Fava et al. (2009) claimed that ISO 14040 should be the basis for future LCA studies [23].

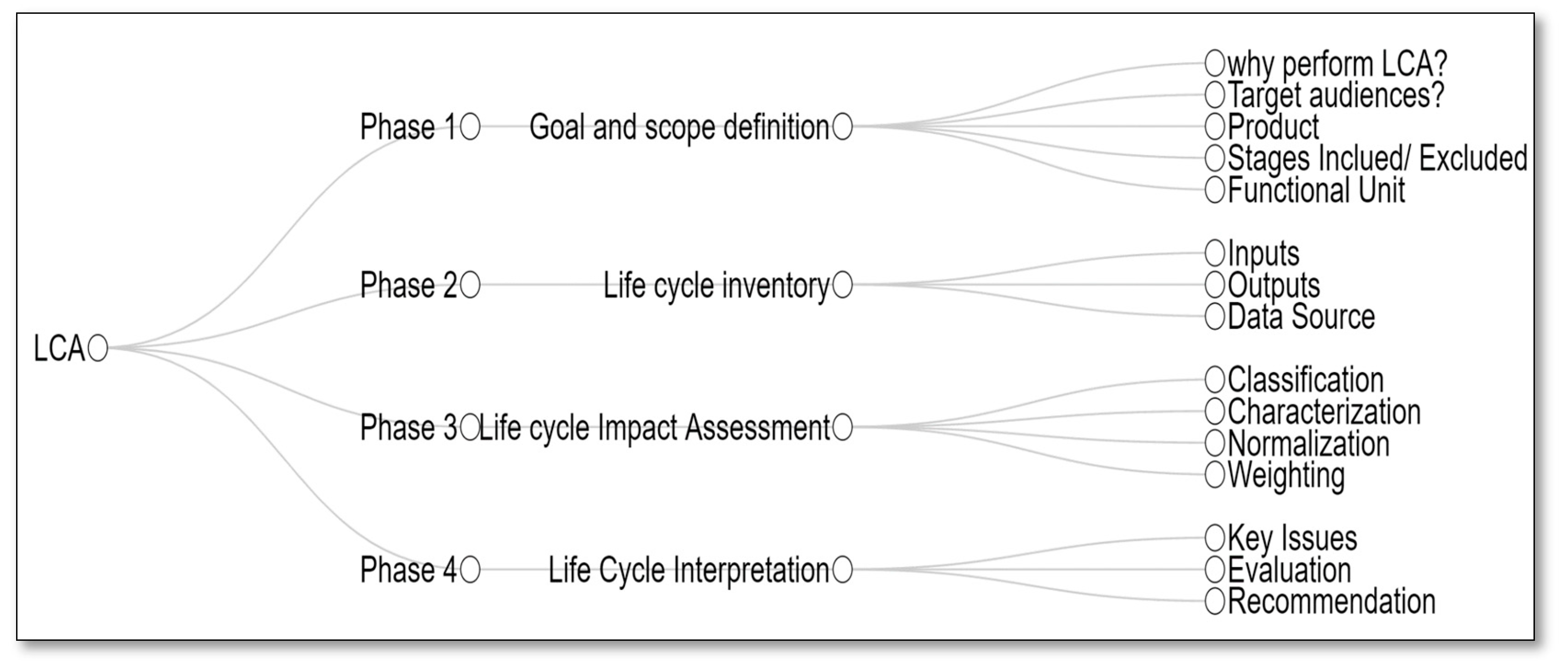

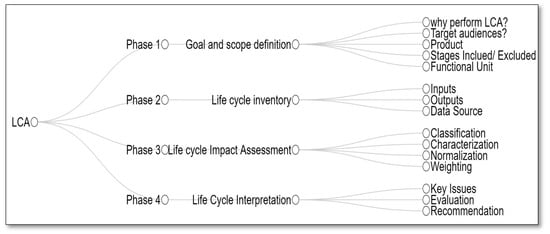

Studies found that the most common tool to study the impact on the environment associated with a product over its life cycle in the agri-food sector was the LCA ISO 14040 standard [14,15]. LCA ISO 14040 has four main phases: (1) goal and scope, which is the essential component of the LCA, (2) qualitative and/or quantitative inventory analysis of the used resources and the emissions released from the life cycle of a product, (3) life cycle impact assessment, which can be divided into classification, characterization, and evaluation, and (4) the interpretation, involving the identification of key issues, evaluation (including checking completeness, sensitivity, and consistency), and development of conclusions together with recommendations, as defined by ISO 14043 (Figure 3). The details of each phase are discussed below.

Figure 3.

Overview of life cycle assessment (LCA) phases.

3.2. Phase 1: Goal and Scope Definition

3.2.1. Goal

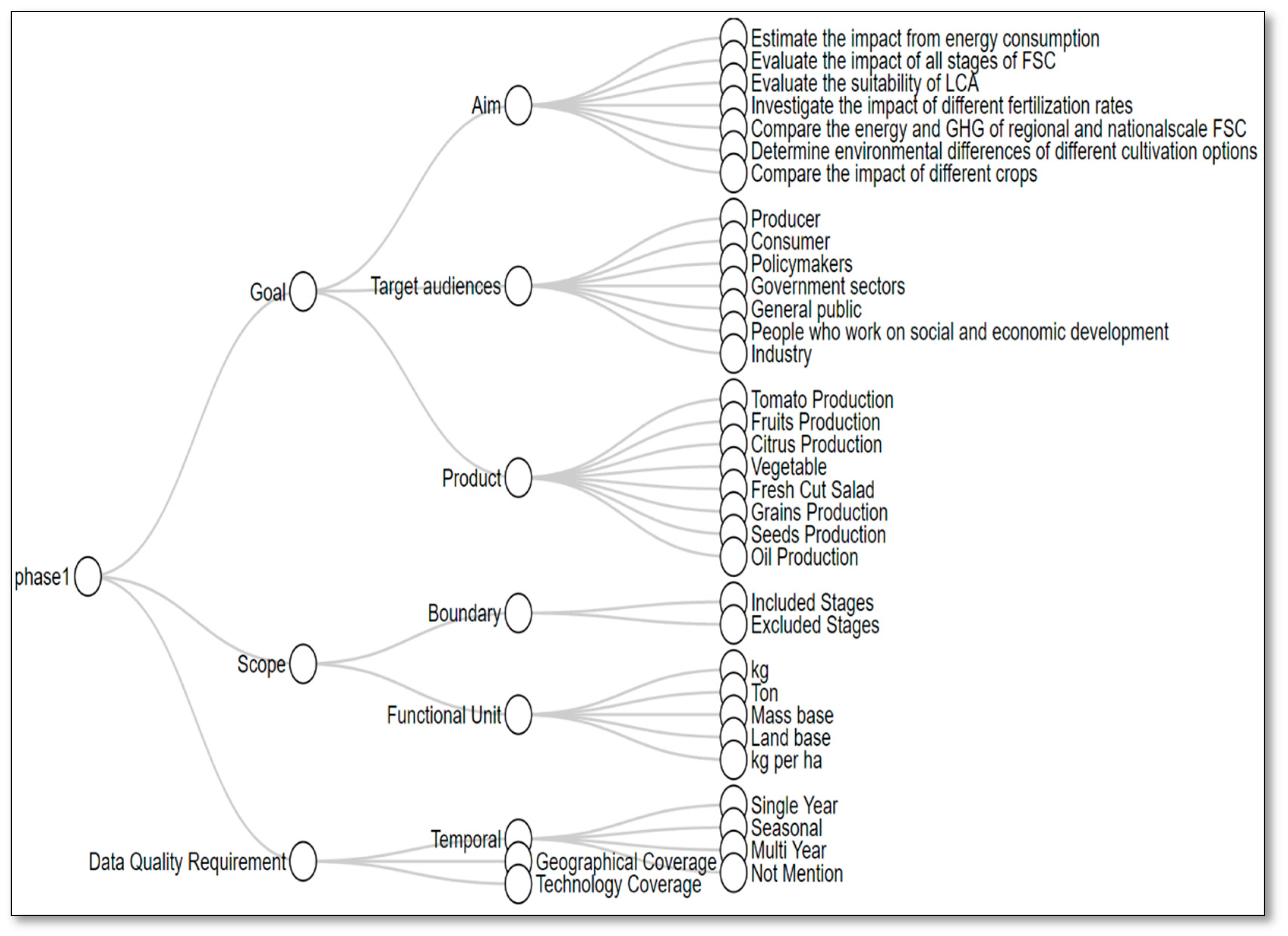

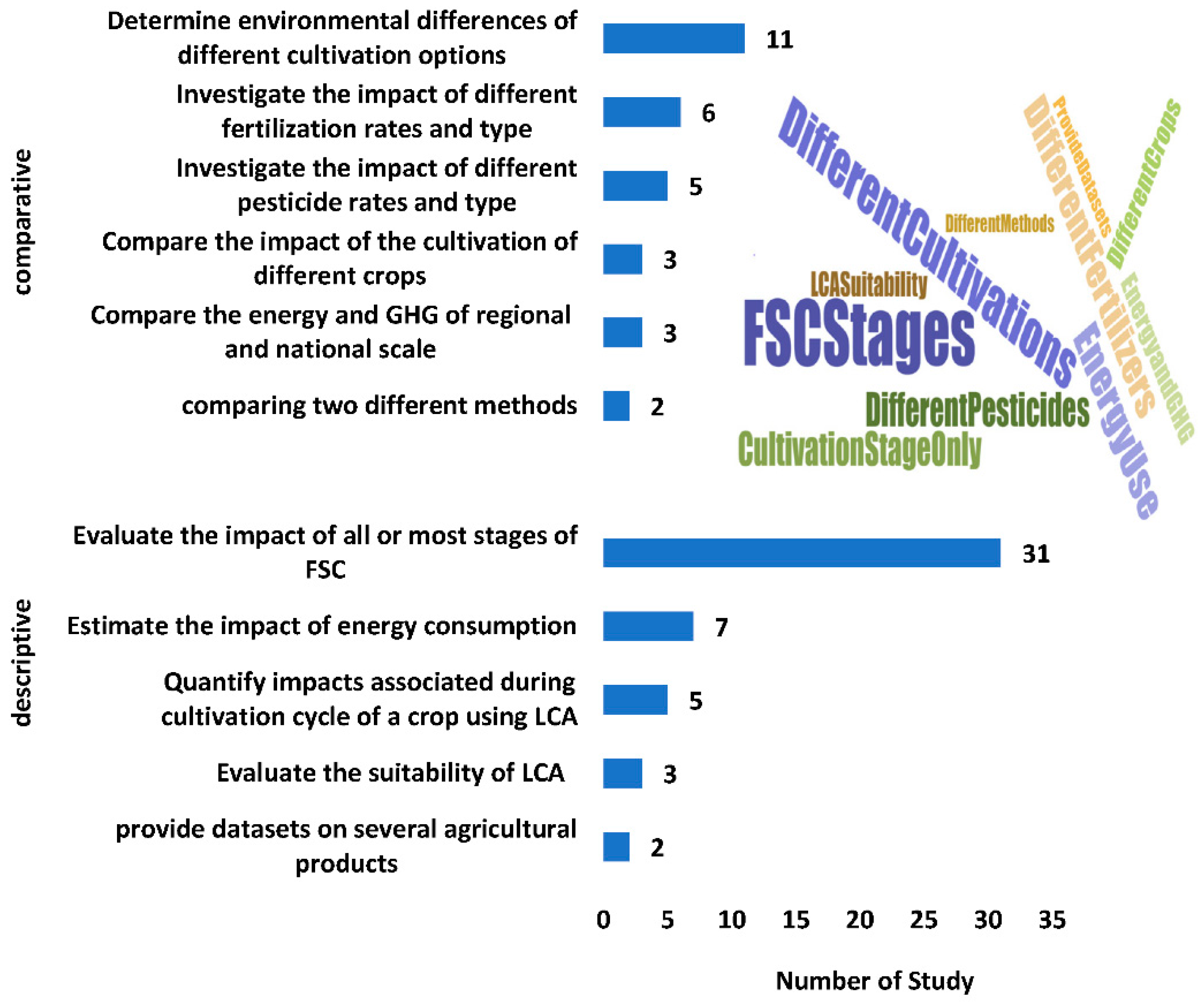

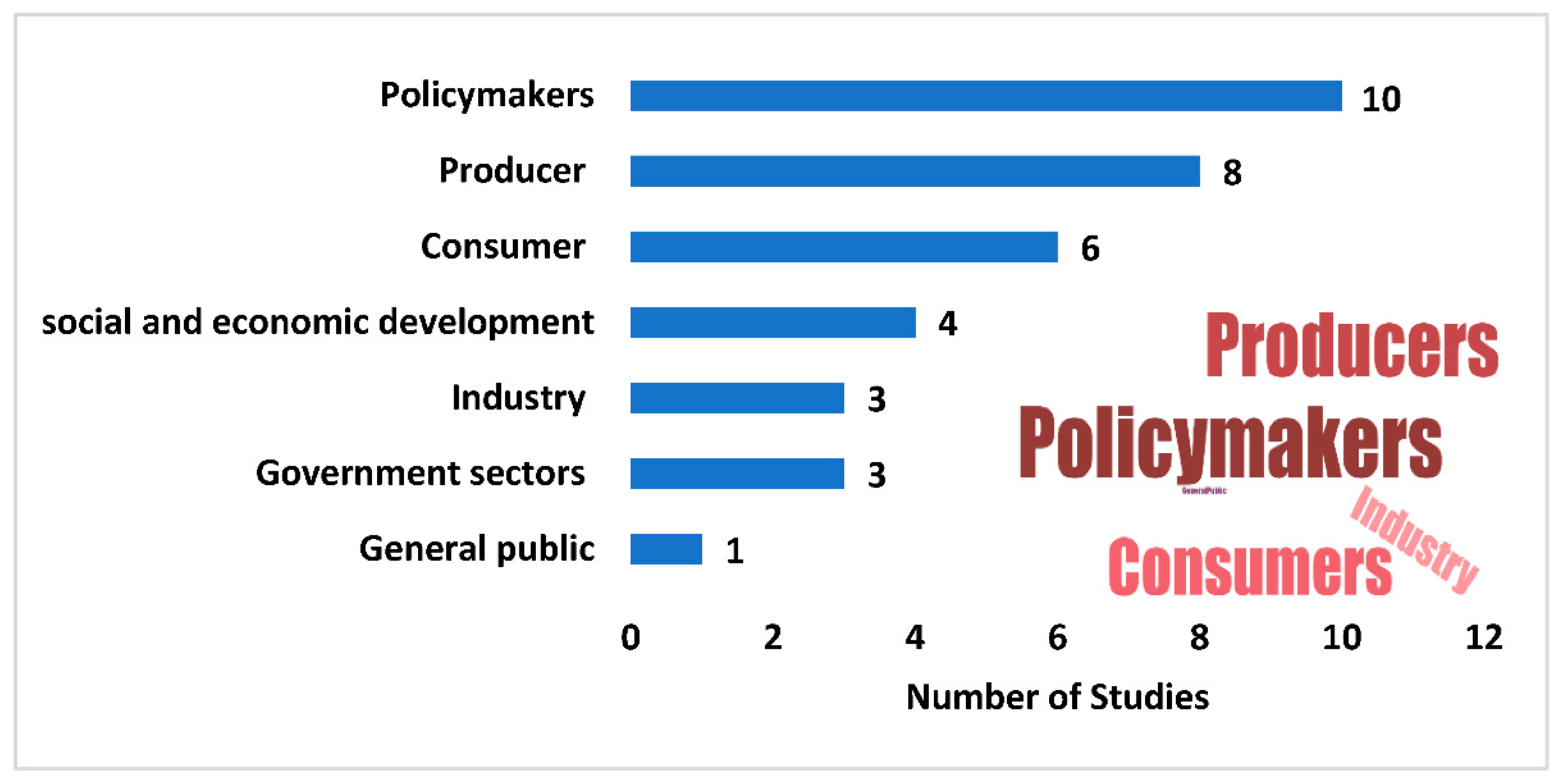

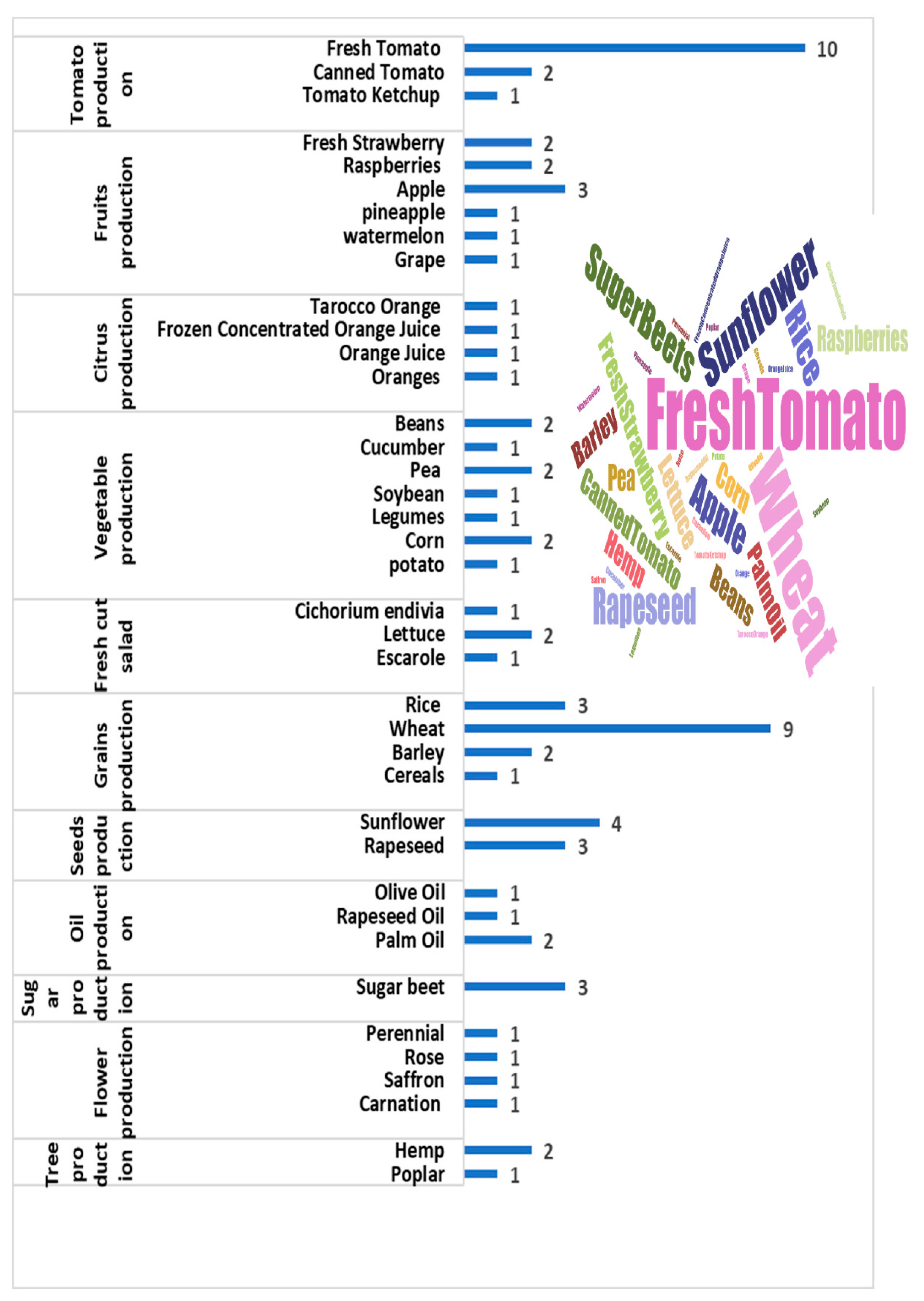

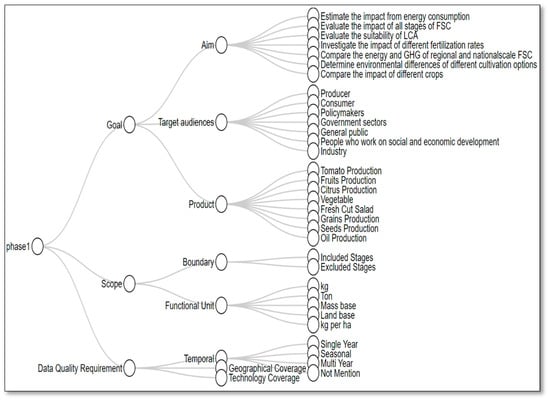

According to Lee and Inaba (2004), the following questions should be addressed to set up the goal: Why perform LCA, who is the target audience, and what is the product under the LCA study [10]? These were recognized from the reviewed articles while examining the first phase of the LCA, as given in Figure 4. Some of the studies stated the answers to these questions directly, whereas others addressed them indirectly. Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7 show the most common responses to each question.

Figure 4.

Phase 1 (goal and scope definition) of life cycle assessment (LCA).

Figure 5.

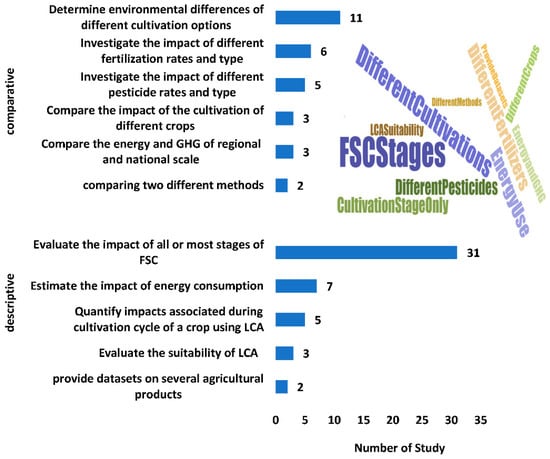

Quantitative and qualitative representation of the common aims of LCA from the literature.

Figure 6.

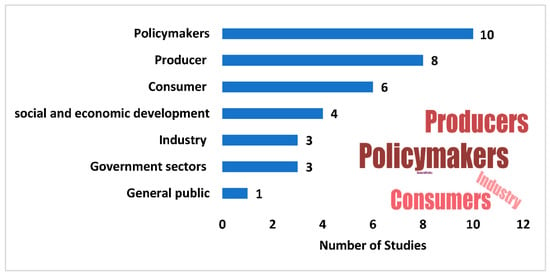

Target audiences in the literature represented as bars (quantitative) and a word cloud (qualitative).

Figure 7.

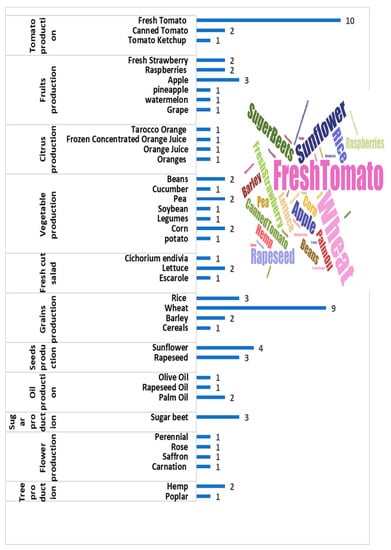

Common agricultural products used in LCA studies.

Aims of LCA

As indicated in the literature, LCA studies can be partitioned into two major categories: descriptive and comparative. Descriptions aim to recognize the natural load of a chosen framework, while comparisons aim to differentiate between two frameworks. Among the discussed papers, 48 were descriptive, while 30 were comparative. As noted, the most common aim was to assess agricultural production, cultivation, processing, packaging, transport, and emission at all production stages to recognize the vast issues and to propose reasonable alternatives that decrease the environmental effects (Figure 5). The purpose of this review was to better understand how to use LCA to evaluate the environmental impact of agricultural production. The least common goal was to compare LCA to other methods, which may be due to the difficulty of making a fair comparison in terms of method performance.

Target Audience

The target audience defines who undertakes or commissions an LCA and for whom. It is critical to understand who will use the LCA results to provide them with helpful information. The majority of articles have multiple target audiences (TAs). Politicians working on climate change, decision-makers, and policymakers on global warming potential (GWP) footprints related to food and common agricultural policy (CAP) were the most common TAs, with 10 studies. Additionally, several studies targeted government sectors such as food sector policymakers, the country’s agriculture sector, and the fruit and vegetable sector. Following that, the producers, namely, the farmers and the producing industry, were targeted in eight studies, six of which provided information to the consumer on a local and international scale (see Figure 6). People working on social and economic development, such as government policymakers for sustainable consumption and production, future ecolabeling programs, and those working to improve the environmental and financial sustainability of existing agricultural systems, were also targeted. Another target audience was represented by the Florida food, agri-food, and citrus industries. As shown in Figure 6, only 35 of the 74 research articles analyzed clearly stated their target audience. The frequency of target audiences is also displayed as a word cloud for a rapid overview.

Agricultural

We divided the products into 11 categories: tomato, fruits, citrus, vegetable, fresh salad, grains, seeds, oil, sugar, flower, and trees, as shown in Figure 7. The most common product was tomato; 13 studies analyzed tomato production, including fresh tomato, canned tomato (whole peeled, paste, and diced), and ketchup. The second most common product was wheat with nine studies. Because some studies involved more than one crop, that explains why the same reference was used for multiple crop groups and why the number of studies on the chart exceeds the number of studies covered. Tomato production was separated into three categories since three types of tomato products (fresh tomato, canned tomato, and tomato ketchup) were considered, as indicated in the diagram.

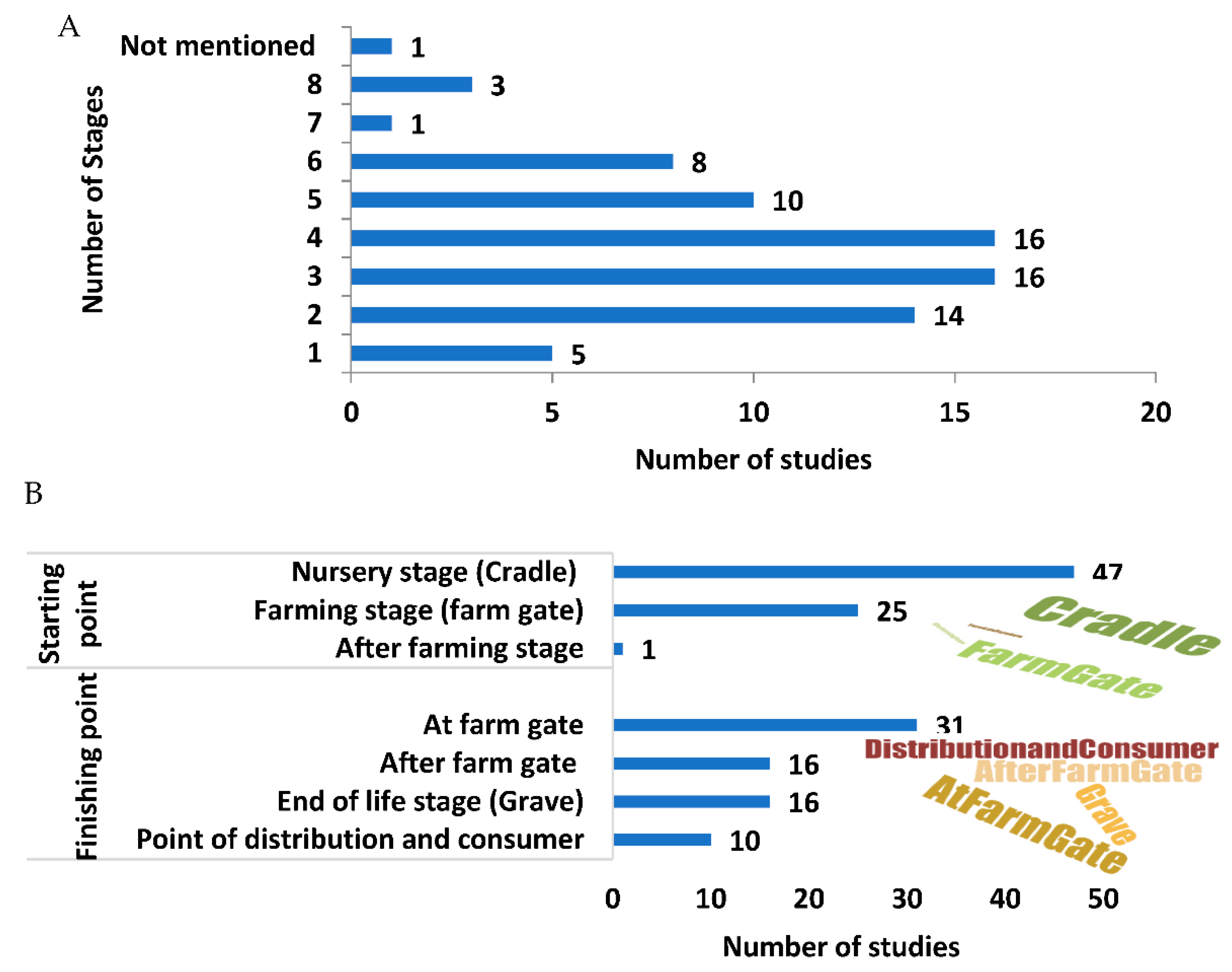

3.2.2. Scope

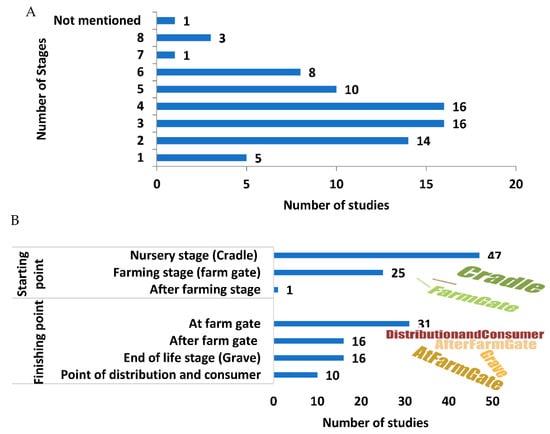

The scope defines the product system boundaries that determine which unit processes should be included in the LCA analysis and which should be excluded. Table A2 (Appendix A) includes more information on all 74 studies, including their inputs and outputs inside and outside of the scope. Most studies (14) contained three to four phases in their boundaries, as shown in Figure 8A. There are two explanations for not including the eliminated phases in the majority of articles. The first is a lack of data and knowledge about individual inputs, making it difficult to get a decent overall view. Secondly, some authors excluded the minor influence stages because it was impossible to include all phases.

Figure 8.

(A) Number of stages included in the systems obtained from the literature; (B) quantitative and qualitative illustration of the starting and ending points of the included stages as boundaries.

Since we are looking at the agri-food supply chain, most of the articles noticeably had similar steps when designing their boundaries. Depending on the selected crop and the target audience, there were slight differences in the scope’s starting point and finishing point (Figure 8B). According to the review, 47 studies started their scope from the nursery stage (cradle), which involves preparing the raw materials, buildings, and field or land. Furthermore, 25 studies began their scope from the farming stage (farm gate). Considering our focus on agricultural production, only one study started their scope after the farming stage.

Similarly, the final stage differed from one study to another, ranging from the farming stage to the grave, including the product’s processing, packaging, storing, and transferring stages. Thirty-one studies in the literature review included steps until the crop harvesting stage, whereas 16 authors included some or all of the processing, packaging, and storing stages in the study’s scope. A number of reviewed studies reached the point of distribution and consumption in their analysis. Disposal and waste management were the final stages in some studies, with 10 articles including the end-of-life phase in their analysis (Figure 8B). One study did not specific boundaries; thus, the number in Figure 8B is less than the number of studies reviewed [24].

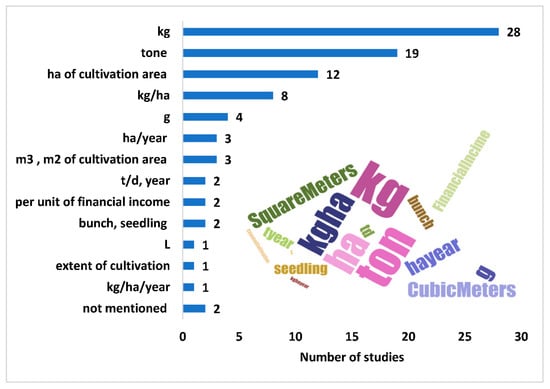

3.2.3. Functional Unit

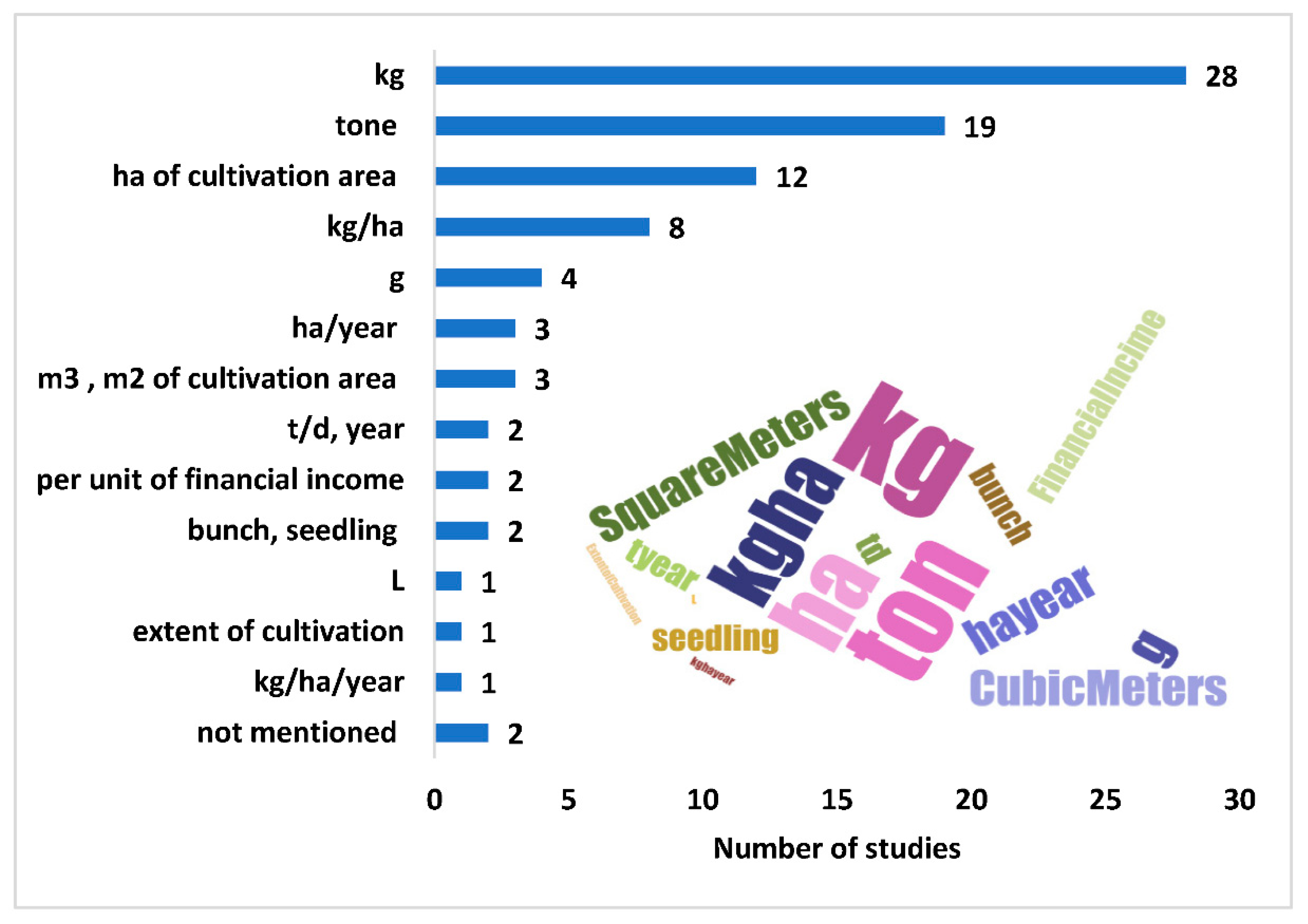

Another step of the goal and scope phase is to choose a functional unit of the scope. A functional unit is the reference unit in which elementary flows from the inventory until the impact assessment stage are represented. Selecting the ideal functional unit is necessary during the boundary designation step. The functional unit is dependent on the type of input materials (raw material) and the final products. Accordingly, the input unit might be separate from the outputs. For example, the output such as GHG emissions could be in kg·ha−1 while the final product could in tons or the input material could be in kWh for energy consumption and kg for fertilizers. Figure 9 shows the most common functional units used in previous studies.

Figure 9.

Functional units identified from the studies.

3.2.4. Data Quality Requirement

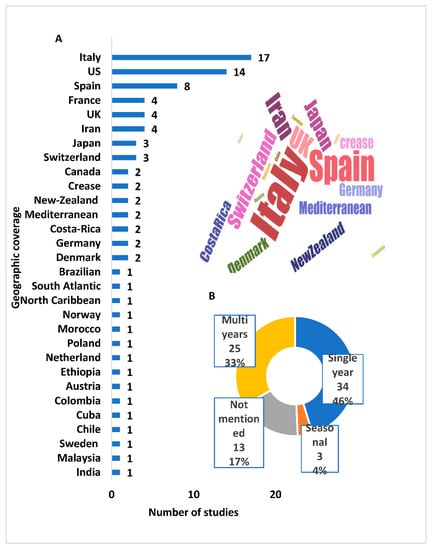

The reliability of the results from LCA studies strongly depends on how data quality requirements are met. The following parameters should be considered: time-related coverage (selected year), geographical coverage (study area), and technology coverage (technology used in the processes stages). This paper examined the temporal and spatial data in detail and the used machinery in general.

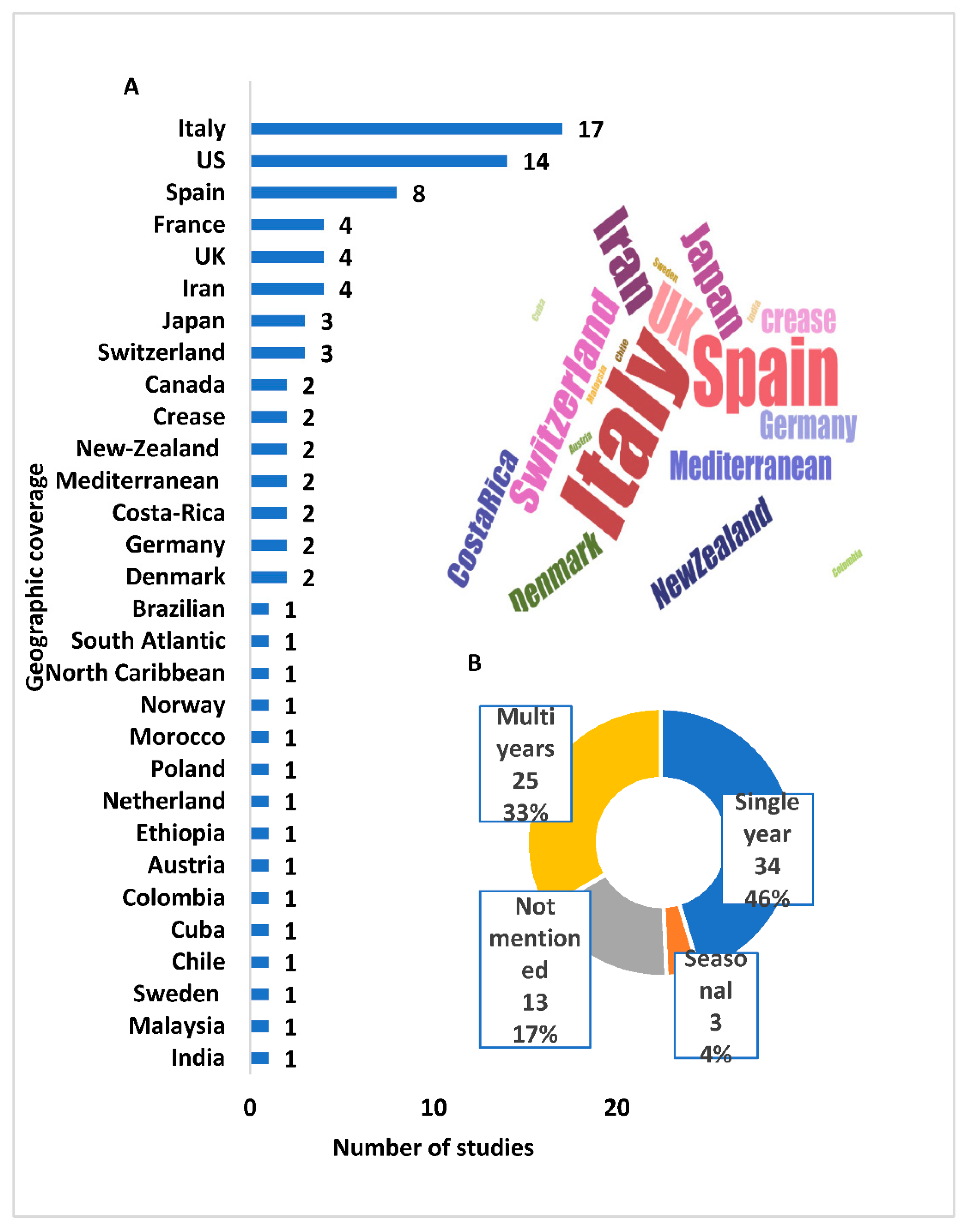

It is understood from the literature review that most studies collected their data for a single year of cultivation (Figure 10B). The spatial scale of the analysis (global or regional) depends on the impact category. For example, global warming is a worldwide issue, whereas acidification is a regional issue. Furthermore, two countries were commonly represented in the evaluated research, Italy and the United States, with 17 and 14 studies, respectively (Figure 10A). When it comes to the technology used in each activity, the majority of the tools mentioned were agricultural equipment, which is to be expected given that we are investigating crop production.

Figure 10.

(A) Quantitative (bars) and qualitative (word cloud) representation of the geographic coverage considered in the reviewed studies; (B) donut chart depicting the temporal scales used in the literature.

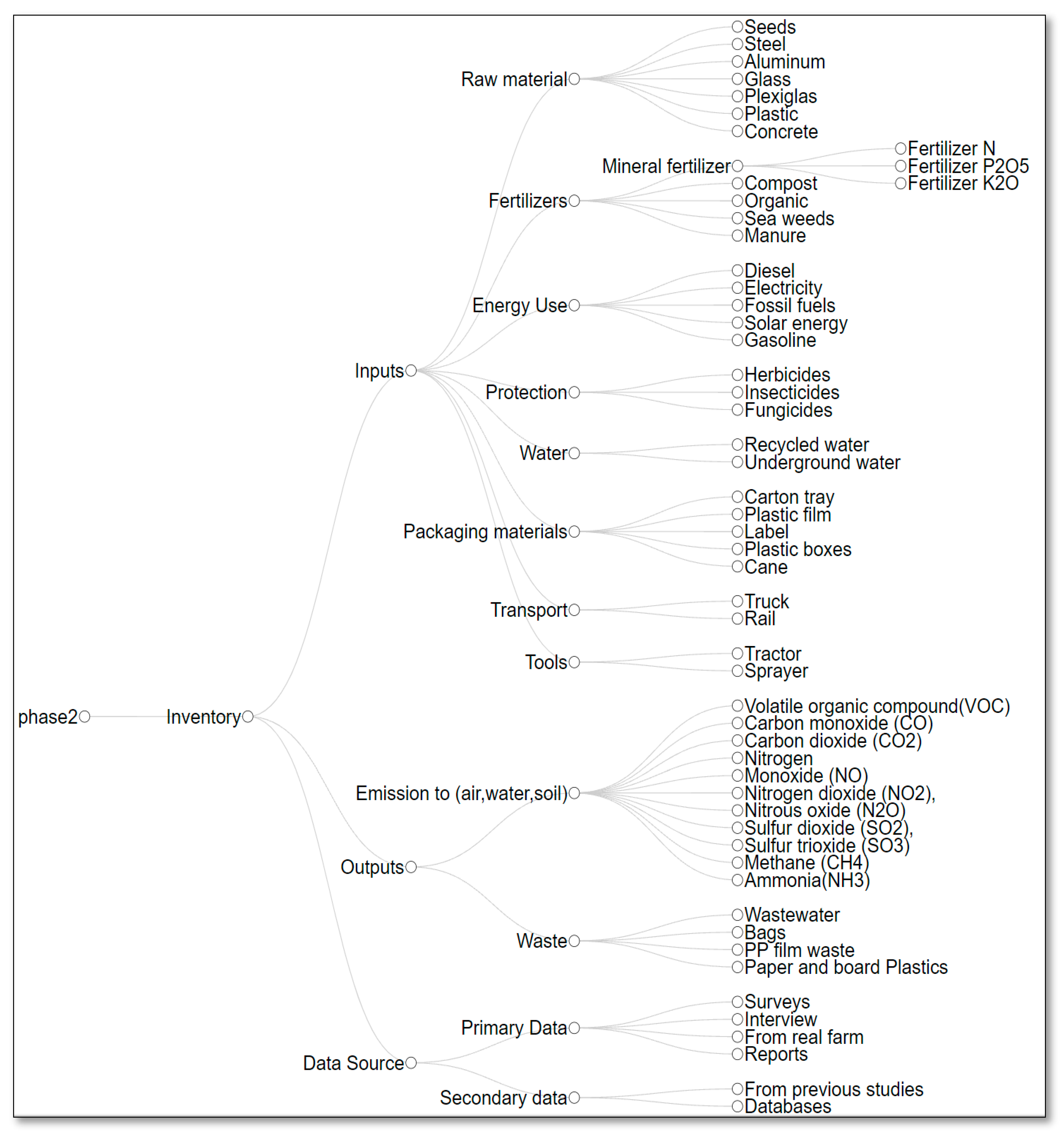

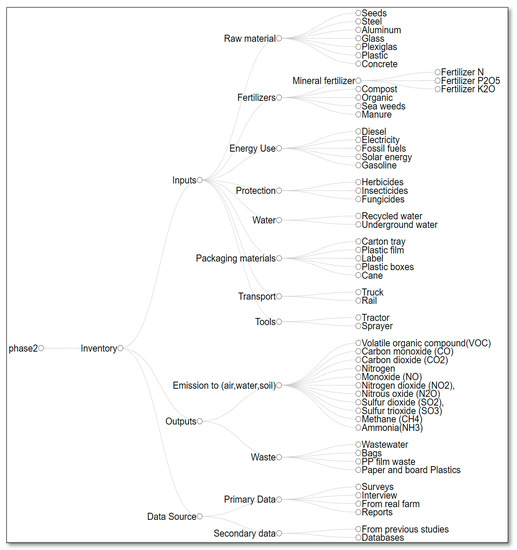

3.3. Phase 2: Life Cycle Inventory

The second step of the LCA is the life cycle inventory analysis (LCI). The product’s life cycle inventory results in an LCA study are obtained by summing up all fractional contributions of the input and output from each unit process in the product’s production system. Thus, LCI generates quantitative environmental information of a product throughout its entire life cycle.

Most studies at this stage specified the input material (water, fertilizer, pesticide, diesel, etc.) in each process of the production included in the scope, as well as the output (harvested crop, waste, emission to the air, soil, and water, etc.). Furthermore, they mentioned the sources of the inventory data (Figure 11), typically being from primary and/or secondary data sources. Primary data are obtained from specific processes throughout the life cycle of the researched product. Process activity data (physical measures of a process that results in GHG emissions or removal), direct emissions data (determined through direct monitoring, stoichiometry, mass balance, or similar methods) from a specific site, or data averaged across all sites containing the specific process are all examples of primary data [25]. Secondary data are collected from government departments, organizational records, and studies that previously gathered information from primary sources and made it available to other researchers.

Figure 11.

Phase 2 (inventory) of life cycle assessment (LCA).

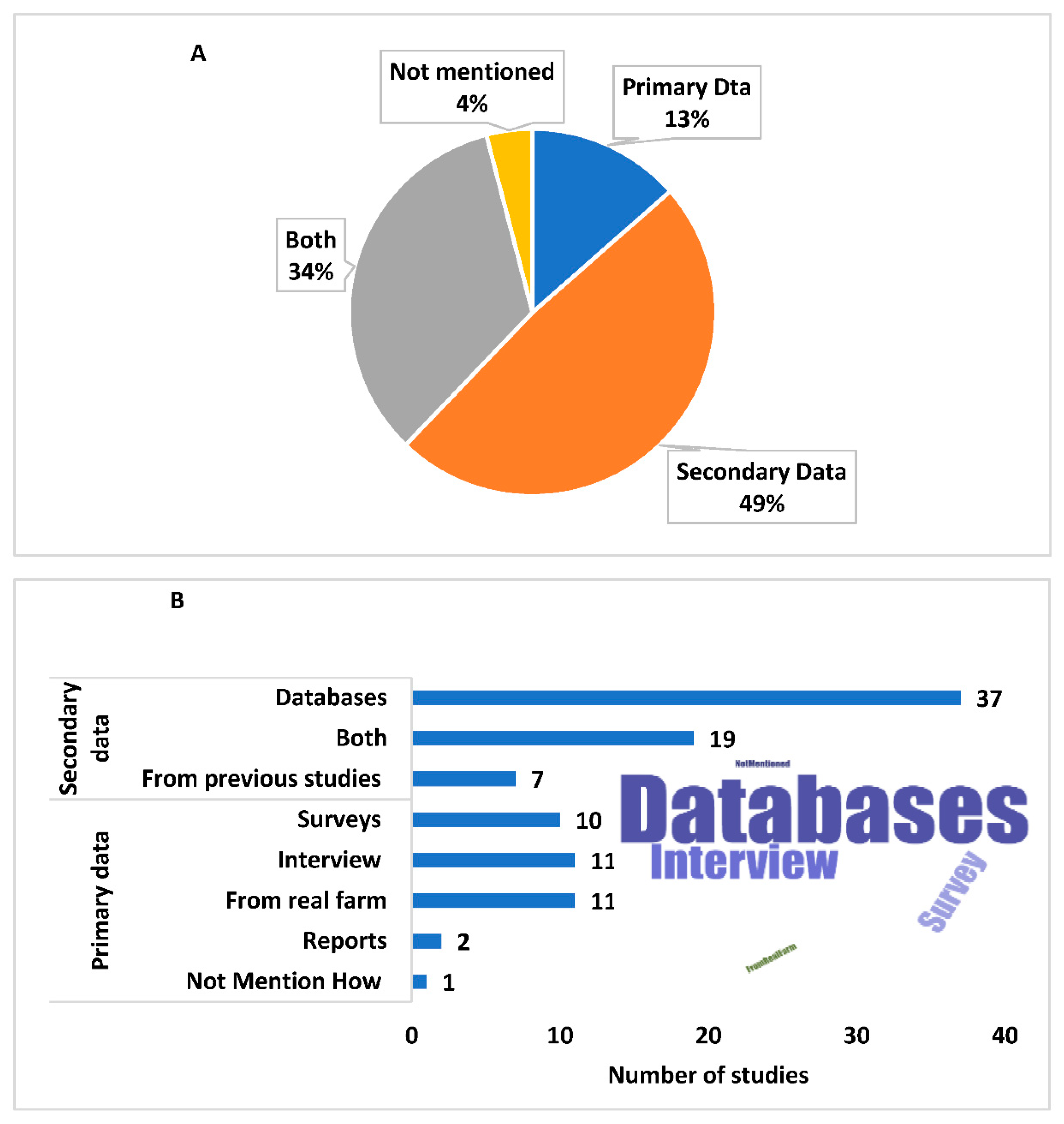

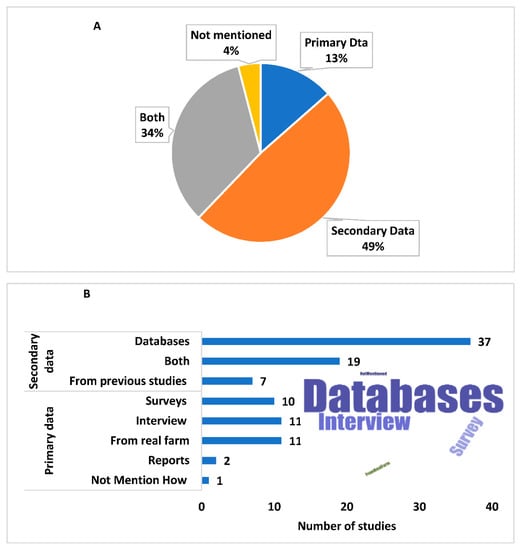

About 48% of the studies used secondary data, 13% used primary data, and 35% used both. One study collected data from a real farm experience. Three authors conducted interviews with owners to collect the data. Two studies used surveys with specific questions to collect the required information. One study mentioned that the source was primary, but the article did not specify their method. Seven studies utilized primary data, while the other nine used secondary data. The authors of the examined research utilized two types of secondary data methods: databases and previous studies. Eleven of the studies used databases, while five of them used previous studies. Five writers, on the other hand, gathered inventory data from databases and prior studies. Twenty-six studies utilized both primary and secondary approaches to reduce the uncertainty of their findings (Figure 12A,B).

Figure 12.

(A) Data sources of the inventory stage rendered as a pie chart; (B) breakdown of primary and secondary data into various sources as obtained from the studies.

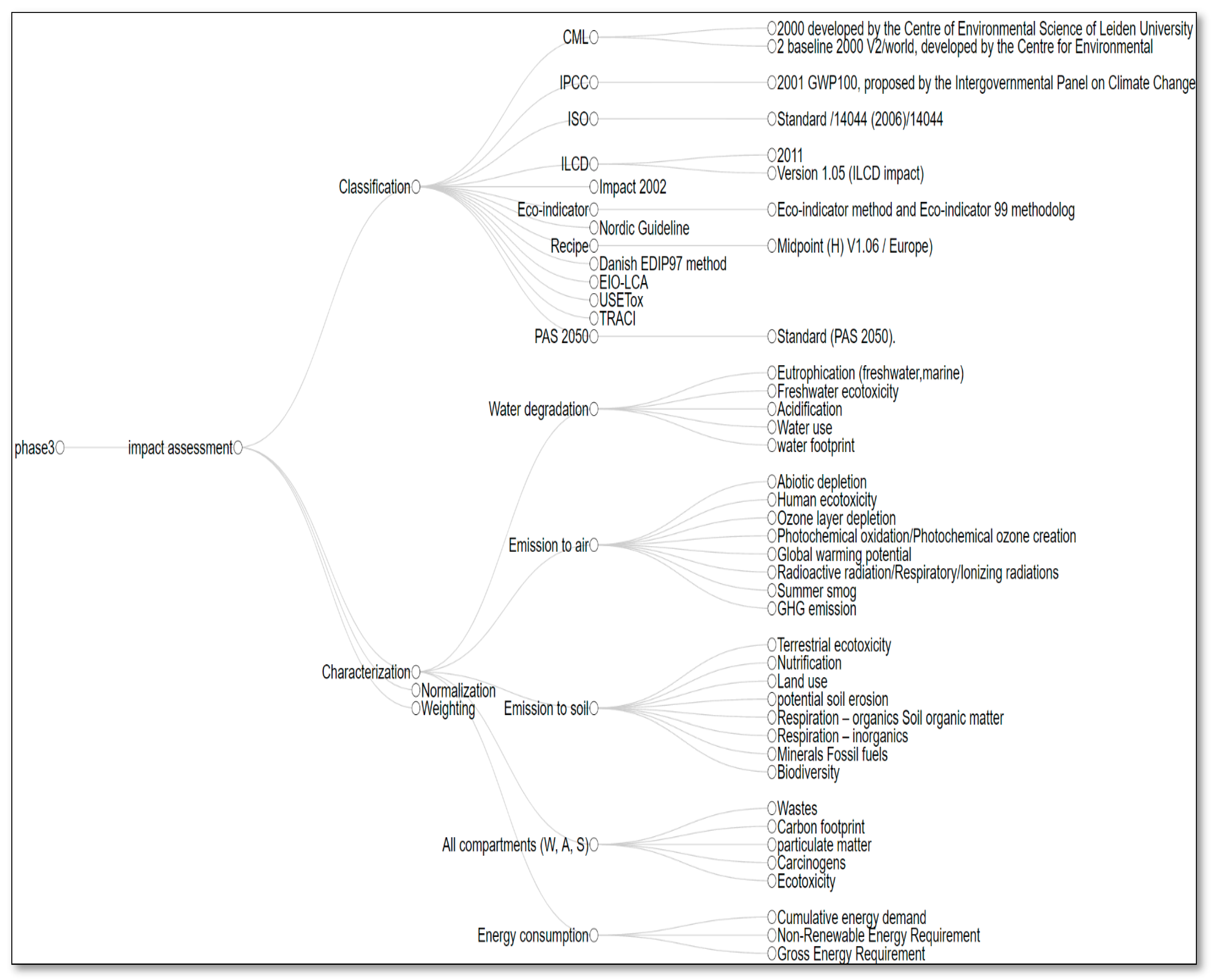

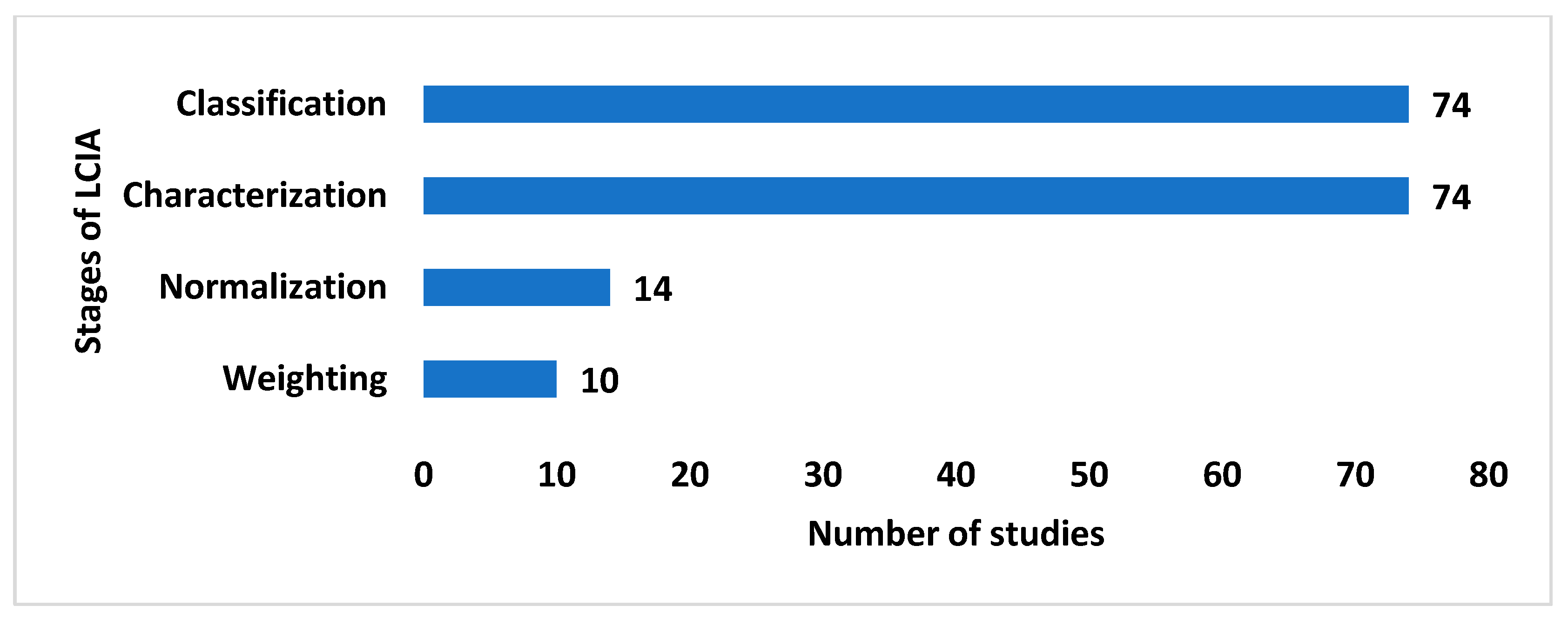

3.4. Phase 3: Life Cycle Impact Assessment

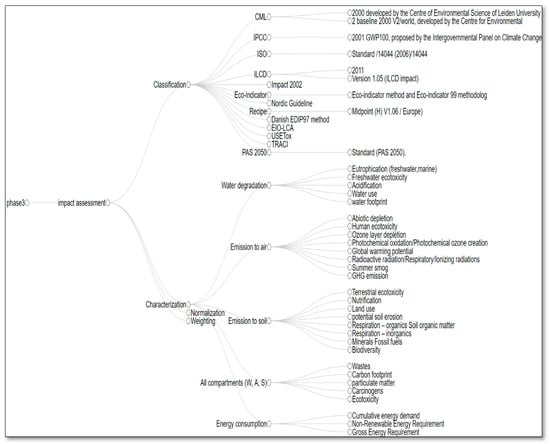

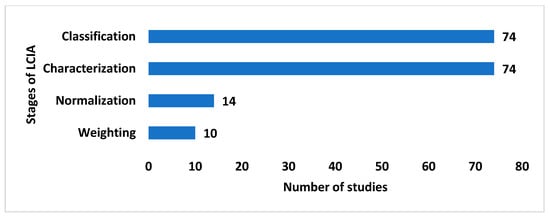

In life cycle impact assessment (LCIA), the significance of a product system’s potential environmental impacts, based on life cycle inventory results, is evaluated using LCIA. The LCIA consists of several elements: classification, characterization, normalization, and weighting. Of these four elements, normalization and weighting are considered optional, while the first two are mandatory elements in LCIA [10] (Figure 13). As shown in Figure 14, all 74 reviewed studies completed the classification and characterization phases, whereas 14 studies completed normalization and 10 completed weighting. Few studies included the waiting stage since it is optional and challenging.

Figure 13.

Phase 3 (impact assessment) of life cycle assessment (LCA).

Figure 14.

Quantitative and qualitative representation of the frequency of components of the LCIA phase in the reviewed studies.

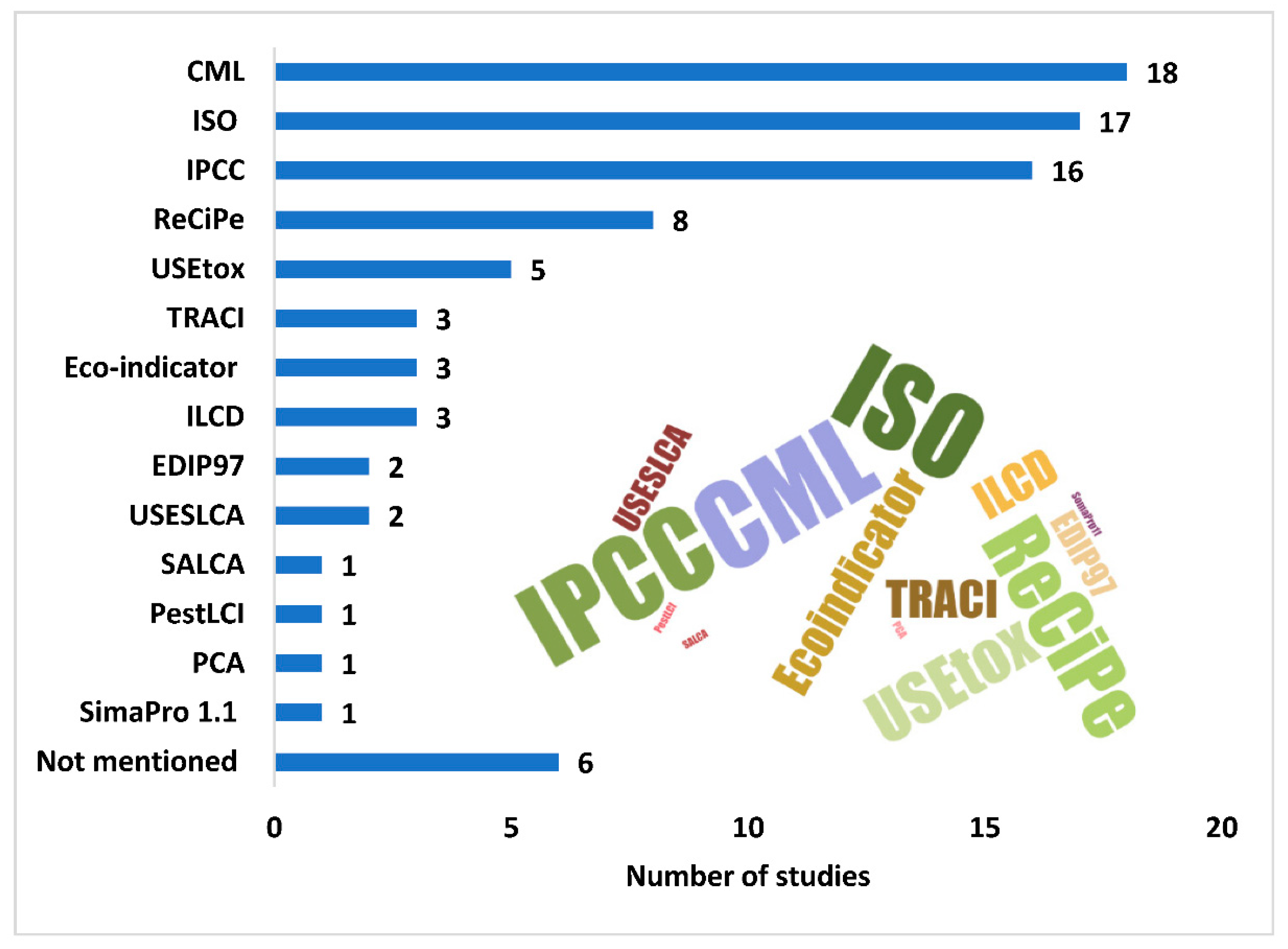

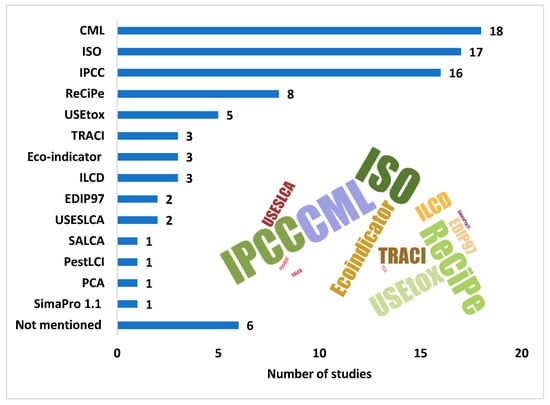

The first step is classification, which involves identifying the impact assessment method. The most common standard method was the CML with various versions, such as CML 2 baseline 2000 V2/world, developed by the Center for Environmental Studies, and CML 2000 produced by the Center of Environmental Science of Leiden University. The second most common methods were ISO 14044 (2006), ISO (2000), and ISO 14040, followed by many other methods, such as IPCC 2001 GWP 100, proposed by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. For more information about the methods used in the studies, see Figure 15. The model used to calculate the impact is determined by the impact category the author intends to examine. As a result, LCA, ISO, and IPCC were the most commonly used impact methods since they provide categorization factors for ecotoxicity and climate change, which were among the criteria used to select articles for this review.

Figure 15.

LCIA methods obtained from the literature review denoted by means of bar plots and a world cloud (classification).

Choosing the correct method for the LCA’s impact assessment stage depends on the impact category under investigation. Each method has categories; for example, CML 2000 has 10 environmental impact categories: abiotic depletion, global warming, ozone layer depletion, human toxicity, freshwater aquatic ecotoxicity, marine aquatic ecotoxicity, terrestrial ecotoxicity, photochemical oxidation, acidification, and eutrophication.

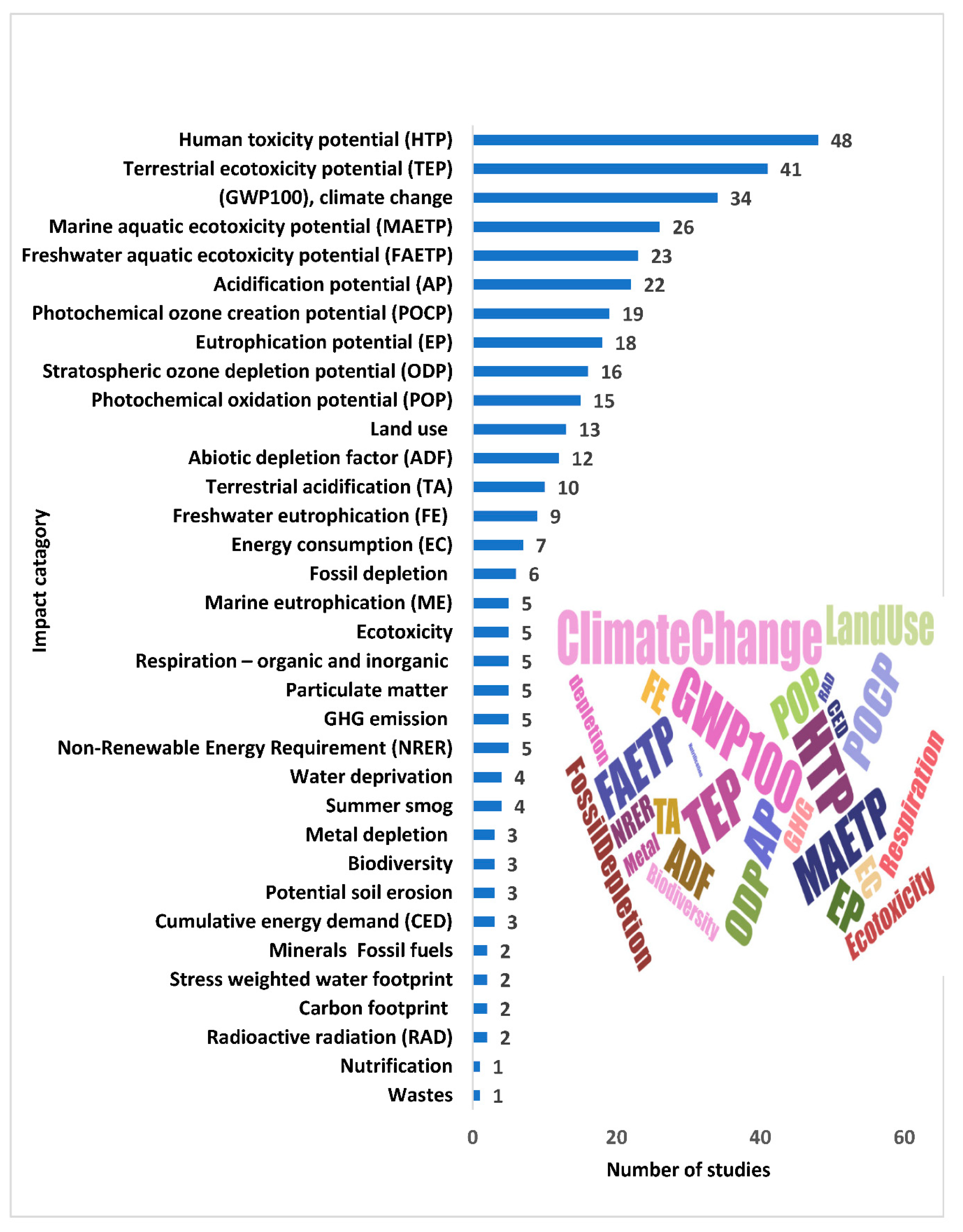

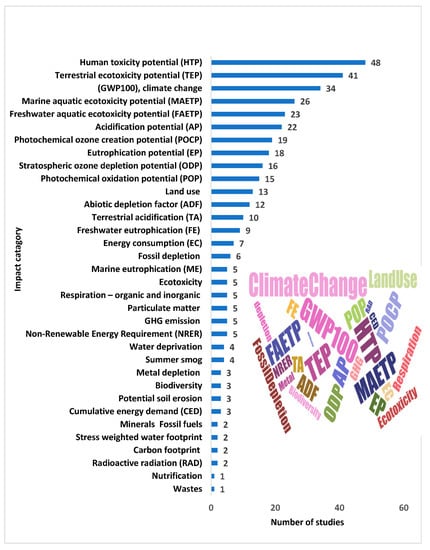

In the process to quantify the impact of a procedure or material used, impact categories are first chosen, followed by quantifying environmental impact in each impact category using the equivalency approach. This process is termed “characterization” [10]. Characterization includes the emissions to air, soil, and water, as represented in Figure 16. The most prevalent impact categories in the 74 papers were human toxicity and ecotoxicity, with 48 and 41 studies, respectively. Moreover, 34 studies included global warming potential as an effect category, whereas marine pollution (26 articles), freshwater aquatic ecotoxicity (23 articles), and acidification potential (22 articles) were topics of the remaining studies (Figure 16).

Figure 16.

Illustration of LCIA impact categories from the literature (characterization).

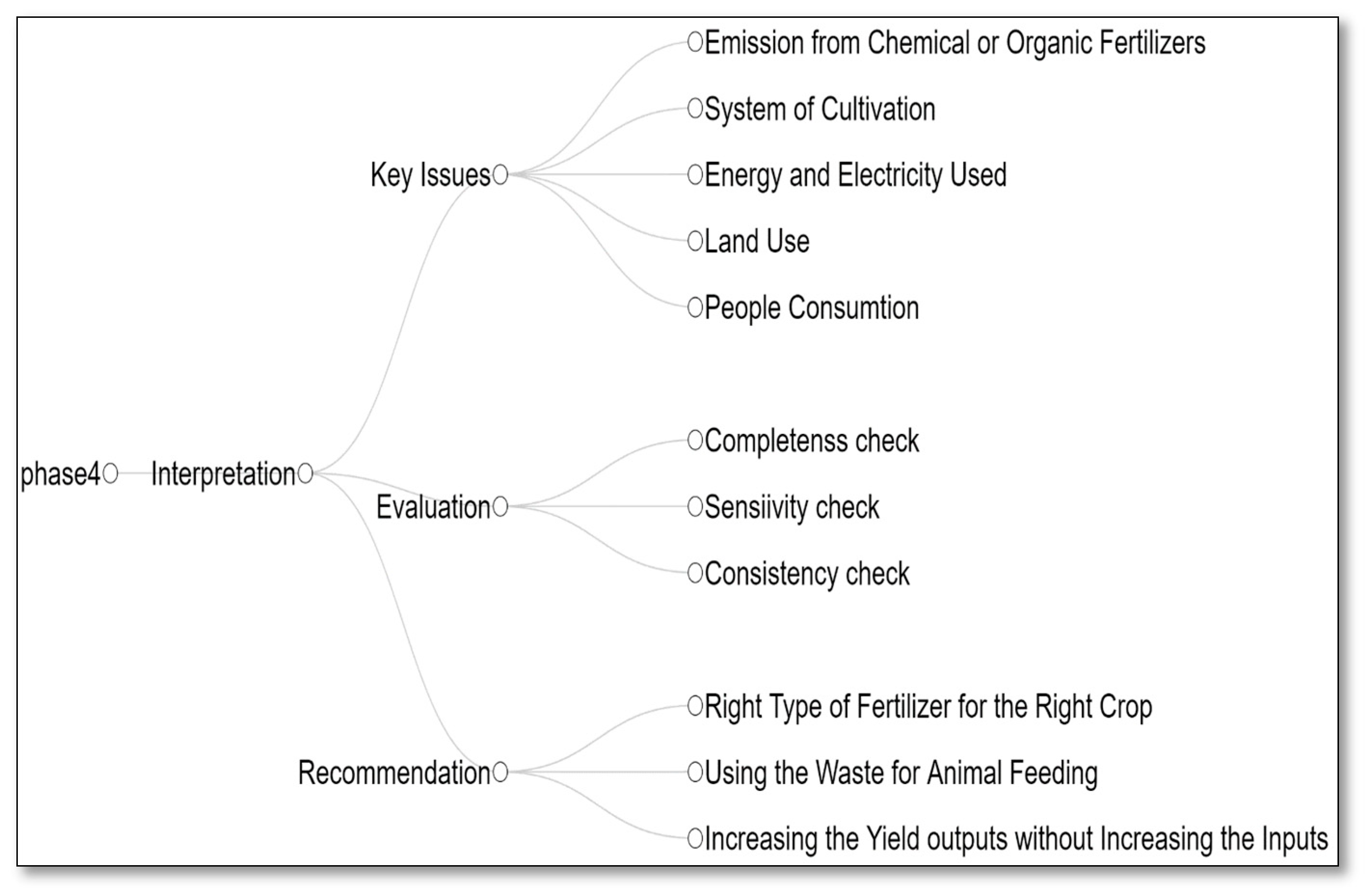

3.5. Phase 4: Life Cycle Interpretation/Recommendation Options

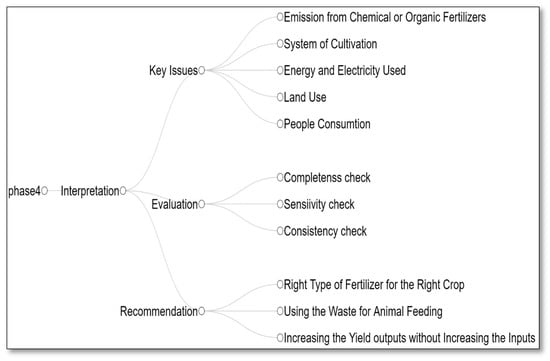

The primary purpose of interpretation, which is the last phase of the LCA, is to use the inventory results and impact assessment analysis to evaluate the starting point for product improvement. The starting point is to understand the process tree and then identify the key issues, i.e., the key processes, materials, activities, components, or even life cycle stages in developing a product. The primary purpose is followed up with improvement recommendations to find more environmentally friendly designs and/or process modification. Studies applied dominance analysis and marginal analysis to identify the key issues. The dominant aspects of the inventory table may be revealed by studying the environmental elements of a process matrix. An arbitrarily chosen criterion, such as “contribution greater than 1% of the total impact”, can be applied in identifying key issues from the matrix. Marginal analysis illustrates the changes in the process to which the intervention, effect, or index is most sensitive. In theory, marginal analysis is a powerful tool in determining product improvement options [8,26].

Many studies stated that, for a complete understanding of the significant driver of the impacts, it is necessary to include all stages and material used through a product’s life cycle, which is very challenging due to a lack of information and databases. However, depending on the aim of the LCA research, the literature review revealed a number of critical concerns, such as emissions from chemical and energy usage, the cultivation method used, land-use problems, and consumption waste.

Furthermore, studies in the literature proposed several recommendations for improving the agri-food system and reducing environmental consequences. One of them was adhering to the EPA and USDA pesticide and fertilizer guidelines. A frequent proposal was to use agricultural waste as animal feed. The most common request, however, was to enhance production without increasing inputs (Figure 17).

Figure 17.

Phase 4 (interpretation/recommendation) of life cycle assessment (LCA).

4. Discussion

The present study reviewed articles related to the environmental impacts of agricultural production in LCA assessment. The main steps in conducting an LCA are defining the purpose of the study and boundary stages involved in the analysis, collecting the data of the inventory phase, estimating the impact of the involved process and used material, and then identifying the key issues, followed up with improvement recommendations. Most studies followed these steps, and some of them had common impact categories. However, implementing LCA is challenging and necessitates meticulous data collection.

4.1. Choice of Time, Spatial Domain, and Elementary Flows in LCA

Nearly 17% of studies did not mention the temporal scale of their analyses, depicting the inherent limitation of ISO 14040/ISO 14044 in considering the time period of evolution and process variations pertaining to diverse impact categories. The highest temporal resolution obtained from the literature was seasonal (4% of studies). The choice of time in LCA depends on the spatial and temporal scale of the impact categories considered. For example, the temporal scale of ecotoxicity varies from hours to years. On the other hand, ecotoxicity impacts have multiple transport pathways such as air, water, and soil emissions with diverse temporal scales. Establishing a time frame for the evaluation in LCA is challenging, as both very lengthy and very short periods of assessment are not practicable depending on the topic of the LCA. Extremely short timescales violate the concept of intergenerational equality, whereas extremely long ones marginalize short-term actions, lowering the incentive to act [27]. Consequently, care should be taken when defining the temporal scale of inventory flows.

About half of the studies (49%) used secondary data collection for the LCA, acquiring data from websites and previous studies. The studies that constituted primary datasets were fewer due to the trouble of obtaining data at the desired spatial/temporal resolution for the inventory flows. The selection of impact categories and spatial domains (Figure 16) clearly reflects a preference for secondary datasets. The major categories studied were human toxicity potential and terrestrial ecotoxicity (the primary contributor being agricultural pesticide emissions). Studies used the approximated characterization factor from models for a particular spatial and temporal horizon to assess the potential impacts. Multimedia chemical exposure models such as CalTOX [28], USES-LCA [28,29], IMPACT 2002 [30], and USEtox [31] can provide the time-dependent concentrations of a chemical in the environmental compartments of air, soil, water, plants, and sediments. The potential impacts are characterized on the basis of the chemical’s fate in an environmental partition and its effect.

4.2. Impact Assessment

The quantity of the input material at each stage of the crop production chain can reduce GHG, as well as emissions, including energy use (diesel, fuel, electricity) both on farm (crop production, machinery use) and off farm (transportation, refrigeration). Additional emissions include fertilizer production and use (N, P2O5, K2O), pesticide use (fungicide, herbicide, insecticide), raw material production and transportation, packaging production, and disposal (Table A2). These sources of emissions contribute to environmental impacts in various ways, including human toxicity, terrestrial toxicity, freshwater toxicity, aquatic toxicity, global warming, and acidification (Figure 16). It has been demonstrated that low-input crops have minimal impacts, but high-input crops have high impacts [32]. Furthermore, the type of input can affect the rate of the impacts. For example, replacing Thomas slag with triple superphosphate reduced the toxicity associated with the presence of heavy metals [33]. Simultaneously, replacing urea with ammonium nitrate reduced the influence of fertilization on eutrophication and acidity induced by ammonia volatilization [34].

4.3. LCA as a Tool in Environmental Policy Decisions

In order to achieve the population demand in the future, increasing food production is not the only pathway to increase food availability. Increased food production necessitates either more land or increased fertilizer and pesticide use on current arable land, with negative environmental consequences such as elevated GHG emissions, biodiversity loss, water contamination, and soil erosion [35]. That explains why, among the LCA papers, the most common target audiences were policymakers and producers, whereby policymakers regulate new policies for upcoming issues and producers follow these rules. The LCA methodology can be used to identify parameters and their variability in order to assist producers, wholesale and retail consumers, and policymakers in aligning their practices and purchasing decisions with low-carbon goals. LCA can also be used to analyze different production systems in order to quantify differences in input consumption and environmental consequences. The key parameters and their variability are then addressed to offer stakeholder metrics for evaluating and aligning their agricultural processes, purchasing decisions, and policies to optimize production supply chains.

4.4. Challenges in Collecting the Information and Limitations

Obtaining each LCA component from the reviewed studies is not simple for the reader due to the authors’ descriptive and nonexhaustive approach. Section 3 shows that diverse communities can benefit from this study on a local, international, and global scale. Hence, the author could have used a table or a flow chart to present the flow of components and stages to summarize the four phases and their components to enable the reader to focus on helpful information.

Another challenge is to identify what information needs to be included in the phases of the LCA. One of the essential characteristics of phase one of the LCA is using a functional unit; some authors mentioned it in the goal section while others mentioned it in the scope section. Noticeably, studies with an economic purpose often did not clearly report the functional unit.

The necessity of incorporating all production processes and their input materials, analyzing all phases to understand the environmental effect, and obtaining an optimal outcome from the LCA analysis of food production systems was emphasized by researchers. However, that is neither possible nor practical because of data limitations and cost restrictions [10]. Accordingly, the minor influential stages were excluded. Hence, most studies focused on a single phase of the food production chain. For example, some studies focused on the cultivation phase because they considered that the food production system’s environmental impact mainly comes from farming activities.

The literature review did not focus on a specific region or a crop. Consequently, many studies appeared while searching using the keywords. Therefore, we included 74 articles related to LCA in agricultural production in general, as well as GHG emissions and ecotoxicity as an LCA impact category.

4.5. Assumptions Used, Benefits, and Recommendations

The LCA of crops along a food supply chain can provide helpful information from an economic, social, and environmental perspective. Using the LCA, stakeholders can better understand the energy, water, and material input and evaluate the outputs’ environmental impacts. Thus, they can regulate new policies and use modern practices to improve the production supply chains.

A substantial understanding of each phase of the LCA is required to present an accurate food product’s environmental impact. This paper clearly explains the LCA’s major components that can serve as a primer for the scientific community. Specifically, because LCA is a systematic tool that allows for analyzing a product throughout its life cycle, LCA is used to study the economic value and importance from the local and global perspectives.

If the final product’s functional unit is introduced at either the goal or the scope stage, the study results would be unaffected from our perspective. However, we recommend illustrating the input’s measurement unit and the outputs while illustrating the production scope, followed by a table of units to be more readable for the audience to understand at which stage the inputs are being used and to represent the elementary flows. Defining the system boundary determines the impact pathway for an impact category that links the elementary flows from inventory to the endpoint of analysis. It is clear that the system boundary processes need to be defined according to the study’s goal and the impact category. Furthermore, the functional unit must be clearly defined to explain the elementary flows from inventory to the endpoint. It is essential to know the impact category that the LCA aims to estimate, which processes are related to it, and their cause–effect relationships. The impact assessment studies were mostly conducted in the European sector since most models and databases are suited for European agri-food products.

4.6. Research Gaps

The information obtained from the literature sheds light on some of the future research needs: (a) the impact of land use on GHG emissions [36], (b) LCA applications based on irrigation techniques using solar energy dealing with waste streams [37], (c) LCA of processed and homegrown vegetables [38], (d) packaging of foods with eco-design solutions [8], and (e) applications of LCA in organic agricultural practices, fertilization practices, mulching and milling techniques, and achievable production yields [39]. Some studies have called for more LCA applications in non-European and non-OECD countries to make their agri-food sector more environmentally friendly [40]. Therefore, it is understood that LCA can be used to make the agri-food supply chain more sustainable.

The inventory flows obtained from the present review point to the inter-dependency of three sectors in LCA: energy, food, and water. Consequently, policymakers can use LCA as a tool to spot the crucial areas that need improvisation within the framework of the food–energy–water nexus. Moreover, it is imperative to understand the drivers of environmental policy for selecting an environmentally friendly agri-food supply system. The regional variation of this nexus calls for more regional LCA assessments based on the allocation of resources. More research is needed to explore future scenarios [41] that drive resource consumption and policy design for long-term sustainability utilizing the LCA framework.

Funding

This material was based on work partially supported by the USDA-National Institute of Food and Agriculture’s Evans-Allen Project, grant 11979180/2016-01711 and 1890 Institution Capacity Building grants 2017-38821-26405, the National Science Foundation under grant No. 1735235, awarded as part of the National Science Foundation Research Traineeship as well as the Saudi Arabian Cultural Mission (SACM) under grant No. KSA10009393.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing does not apply to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Common aims in the selected studies.

Table A1.

Common aims in the selected studies.

| Aim | Type of Aim | Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Evaluate the impact of all or most stages of FSC | Descriptive | [12,38,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69] |

| Determine environmental differences of different cultivation options | Comparative | [24,36,39,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77] |

| Estimate the impact of energy consumption | Descriptive | [42,43,48,50,78,79,80] |

| Investigate the impact of different fertilization rates and type | Comparative | [34,70,81,82,83,84] |

| Quantify impacts associated during cultivation cycle of a crop using life cycle analysis | Descriptive | [32,85,86,87,88] |

| Investigate the impact of different pesticide rates and type | Comparative | [28,89,90,91,92] |

| Evaluate the suitability of LCA | Descriptive | [34,93,94] |

| Compare the energy and GHG of regional and national scale | Comparative | [40,95,96] |

| Compare the impact of the cultivation of different crops | Comparative | [97,98,99] |

| Provide datasets on several agricultural products | Descriptive | [47,100] |

| Compare two different methods | Comparative | [101,102,103] |

Table A2.

Inventory data of the selected studies.

Table A2.

Inventory data of the selected studies.

| # | Reference | Data Source | Practice | Input | Unit | Output | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | [42] | Primary data Not mentioned how | Field preparation Seeding Post seeding weed control Creation of irrigation ditches Irrigation Irrigation Supporting with reeds Fertilization Plant protection Harvest Life cycle inventory data (per 1 t of beans produced) and (per 1 ha cultivated) | Diesel Seeds Manure Water (electricity) Herbicides, insecticides, fungicides N fertilizer, P2O5, K2O Manure cattle, sheep Seaweeds Land occupation | 60 kw tractor 60 kw tractor kg kg ton ton m2/year | Emissions to air, water, and soil) harvested beans | kg |

| 2 | [43] | Primary data (real farm) Secondary data (previous studies) | Cultivation and crop Orange transport Selection and washing Primary extraction | Fertilizers: N, P2O5, K2O Water Diesel HDPE bins Electric energy Water Recycled water | kg MJ kg MJ kg MJ kg | CO2, CO, NOx, SO2, N2O, NH3 Oranges Wastes (leaves, rejected, citrus) Wastewater purification plant Scraps | kg kg kg kg kg kg kg |

| 3 | [44] | Primary data (Interview) secondary data (Databases) | Crop management practices Maintenance of watering canals Bank management Plowing Fertilizing Harrowing Sowing Application of plant protection products Harvesting Fertilizers Cuoio torrefatto (12% N); ORVET 8 (8% N); Urea (46% N); Calce Fosfopotassica (8% P2O5–22% K2O–20% CaO); Complesso (18% N–36% K2O); ORVET (10% N–5% P2O5–15% K2O); Complesso (11% N–12% P2O5–36% K2O) Pesticides Gulliver Londax 60 DF–Square 60 WDG Pull 52 DF Sunrice Karmex Buggy–Clinic 360 Stratos ultra Aura K-Othrine Dipterex Heteran Nominee Rifit Cannicid–Poladan | Excavation hydraulic digger Ploughing Tillage, plowing Fertilizing, by broadcaster Tillage, harrowing, by rotary harrow Sowing Application of plant protection products, by field sprayer Combine harvesting 12% N, 46% N, 21% P2O5, 50% K2O | m3 ha ha ha ha ha kg/ha | Direct field emissions (CH4, NH3, etc.) Indirect emissions from combustion delivered refined rice Rice byproducts: husk, flour, broken grains, green grains | kg |

| 4 | [104] | Secondary data (previous studies) | Fertilizer production (process gas and fuel) Arable farming P fertilizer application Fertilizer production (effluents) Arable farming (volatilization) Fertilizer production (nitric acid production) Arable farming (denitrification/nitrification) Arable farming (leaching) P fertilizer production (effluents) | NA | NA | Fossil fuels (oil, natural gas, hard coal, lignite) Minerals (phosphate rock, potash) Land Cd CH4, CO2, CO, NOx, particles, SO2, NMVOC Ntot NH3 N2O NO3-N Ptot | NA |

| 5 | [95] | Secondary data (databases) | Field production Diced tomato processing Tomato paste processing Diced tomato packaging Tomato paste consumer packaging Transport: long-haul truck, rail | Fertilizers (synthetic/organic) Crop protection (chemical/organic) Energy (diesel, gas, electricity) Seeds/plants Water Energy Chemicals Packaging materials Fuel use efficiency | L/mt km | Field emissions of N2O during tomato production Field emissions of CO2 GHG emissions associated with the production of seeds and transplants Emissions intensity | kg CO2/mt km |

| 6 | [78] | Primary (survey and interview) Secondary data (databases and previous studies) | Pesticides Fertilizers Machinery Energy water | NA | NA | Emission from direct energy consumption and field emission Harvested apple | 1 ton |

| 7 | [8] | Primary data (real farm) Secondary data (databases) | NA | Steel, aluminum, concrete, glass fiber resin, plastic Water Fertilizer, manure Pesticide Packaging Diesel | kg m3 kg kg kg kg | Organic waste Construction waste Packaging Plastics oils Hazardous waste | kg kg kg kg kg kg |

| 8 | [45] | Primary data (interview) Secondary data (databases) | Motion of tractors Conveying and unloading Optical selection Washing Peeling Crushing and pulping for the juice Sorting Can filling and pasteurization Water purification Palletizing Irrigation Tomato fertilization Plant protection Tomato fruit transport Packaging | Diesel Electricity Natural gas Water N, P2O5, K2O Insecticide, fungicide Tin can, label, carton tray, plastic film, pallet, box for transport, plastic boxe | kg kWh/can kWh/can m3/Can kg L g/can | The resulting impact was provided as output. | NA |

| 9 | [46] | Primary data (Surveys | Resources Raw materials and fossil fuels Electric and thermal energy | Occupation, permanent crop, fruit, extensive Transformation, to permanent crop, fruit, extensive Transformation, from pasture and meadow Water, process, unspecified natural origin Fertilizer N, P2O5, K2O Pesticides Planting Irrigating Pesticide treatments Transport Power saw Petrol unleaded at a refinery Diesel at refinery Lubricating oil Sawmill Transport, lorry 16–32 ton, EURO Orchard end of life | ha·year ha ha m3 ton ton ha m3 ha kton·km p kg kg kg p ton·km p | Emission in water Nitrogen, total Phosphorus, total Potassium Waste treatments Disposal, hazardous waste, 25% water, to hazardous waste incineration | ton ton ton kg |

| 10 | [47] | Primary data (interview) Secondary data (databases) | Fuels, fertilizers, pesticides, water use, agricultural machinery models and use, yield, harvest schedule, distance and means of transport to the packing facility. | NA | NA | Air emission Water and soil waste | NA |

| 11 | [48] | Primary data (Survey) Secondary data (databases) | Life cycle inventory data for greenhouse tomato and cucumber (per 1 ton of produced crop). Energy coefficients of different inputs and output used | Machinery Labor Diesel fuel Electricity Natural gas Nitrogen Phosphate Potassium Sul Farmyard manure Pesticides Water for irrigation Plastic 1. Machinery Tractor, self-propelled Stationary Equipment implemented, machinery 2. Human labor 3. Natural gas 4. Diesel fuel 5. Biocide Herbicide, fungicide, insecticide 6. Fertilizers: N, P2O5, K2O 7. Micro (M) 8. Farmyard: manure 9. Water for Irrigation 10. Electricity 11. Seeds | kg h L kWh m3 kg kg kg kg kg kg m3 kg kg·year kg·year h m3 L kg kg kg kg m3 kWh kg | Tomato/cucumber | kg |

| 12 | [70] | Primary data (real farm) Secondary data (databases) |

Industrial composting process Biofilter characteristics and gaseous emissions

Phytosanitary substances substage (CuP) Machinery and tools substage (CuM) Irrigation substage (CuI) Post-application emissions sub-stage (CuE) Nursery plants substage (CuN) Management of waste generated in the cultivation stage

Greenhouse management substage (GM Avoided burdens of dumping OFMSW and BA in landfill | Fertilizer application Compost HNO3, KNO3, KPO4H2, K2SO4 Nitrogen application organic, mineral Irrigation water Per area Per ton tomato Open field (OF) Commercial yield, Total yield Tomato average diameter Tomato average weight Greenhouse (GH) Commercial yield Total yield diameter Tomato average weight Trucks | g·m−2 g·m−2 L·m−2 m3·FU−1 t·ha−1 mm g t·ha−1 t·ha−1 mm g T MAL | Outputs of the composting process in the industrial composting plant of Castelldefels Greenhouse gases | |

| 13 | [71] | Secondary data (both) | Wheat life cycle inputs Transport | N, P: conv Pesticide: conv Phosphate rock: org Manure: org Diesel (org and conv) Gasoline (org and conv) Truck, rail transport | kg, kg P kg kg of manure P L L t km | Baking, packaging, and sales Wheat Flour | kg |

| 14 | [39] | Secondary data (Both) | NA | Average yield per cultural cycle Specific area Water Organic fertilizers Crop residues (durum wheat) Manure Foliar nitrogenous fertilizer Differentiated and prolonged release nitrogenous fertilizer Mineral fertilizers Controlled release NPK fertilizer (14–7–14) NPK complex fertilizer Total nutrient supply N (organic fertilizers) N (mineral fertilizers) N (total) P (total, as P2O5) K (total, as K2O) Pesticides (active substances) Benfluralin (herbicide) Propyzamide (herbicide) Boscalid (fungicide) Pyraclostrobin (fungicide) Cyprodinil (fungicide) Fludioxonil (fungicide) Deltamethrin (insecticide) Spinosad (insecticide) Black LDPE mulching film (35 mm; 28 g/m2) | t m2 m3 t t kg kg kg kg kg kg kg kg kg kg kg kg kg | To air: NH3, NOx Groundwater: Surface waters: (PO4) Soil Heavy metals (Cd, Cr, Cu, Ni, Pb, Zn) Pesticides (active substances) | |

| 15 | [96] | Secondary data (databases) | Fertilizer production Pesticide production Production of greenhouse infrastructure | Mineral fertilizer N Mineral fertilizer P Mineral fertilizer K Manure compost Organic fertilizer Steel Aluminum Glass Plexiglas Plastic Iron Concrete Rockwool | N kg·ha−1·year−1 P kg·ha−1·year−1 K kg·ha−1·year−1 N kg·ha−1·year−1 N kg·ha−1·year−1 kg·ha−1·year−1 kg·ha−1·year−1 kg·ha−1·year−1 kg·ha−1·year−1 kg·ha−1·year−1 kg·ha−1·year−1 kg·ha−1·year−1 kg·ha−1·year−1 | Machine use Energy demand heating changes in soil organic carbon | h ha−1 GJ year−1 N2O emissions direct N2O emissions indirect Humus sequestration |

| 16 | [81] | Primary data (real farm) | NA | N min in the soil in spring Mineral N fertilizer rate Atmospheric N deposition Net N mineralization during vegetation Mineralization of N from sugar beet leaves (easily degradable part) Mineralization of N from sugar beet leaves (slowly degradable part) | NA | NH3 volatilization N2O emission N removal with beets N content of leaves N uptake of winter wheat in autumn | One ton of grain |

| 17 | [49] | Primary data (interview) Secondary data (databases) | Greenhouse Training system Irrigation system | Low-density Polyethylene Sawn timber Steel Wire Polyethylene Sawn timber Wire Polyethylene Polyvinylchloride | k m3 kg kg kg m3 kg kg kg | Fresh tomato Air emissions NH3 N2O-N NOx-N Water emissions N-NO3 | t kg·ha−1 kg·ha−1 |

| 18 | [50] | Primary data (real farm) Secondary data (previous studies and databases) | Cultivation and crop Primary process (citrus selection and washing, extraction) Secondary process (refining; centrifugation) Secondary process (refining; pasteurization and cooling) Concentration and cooling Packaging and storage Transport of final products | Fertilizers Water Diesel Electric energy Water Recycled water Water-oil emulsion Electric energy Cooling water Raw juice Methane Electric energy Steam Electric energy Methane Steam Cooling water electric energy Essential oil Electric energy Natural juice Concentrated juice HFO, Diesel | NA | Air emissions Amount of citrus fruit Wastes (scraps, leaves, rejected citrus) Wastewater to a purification plant Scraps to pressing process Essential oil to packaging and storage Wet wastes Wastewater to purification plant Natural and concentrated juice Concentrated juice | NA |

| 19 | [40] | Secondary data (previous studies) | (larvae/fingerlings, fertilizers, and feeds). | NA | NA | nitrogen and phosphorus emissions | NA |

| 20 | [51] | Primary data (reports) Secondary data (databases) | Land use Pesticides Fertilizer use Fuel use Seed use Sun use Agr. operations Lime hydrated Cane Cane transport River water Air Softened water Ammonium sulfate Sulfuric acid Yeast Transport of filter cake Transport of ashes | Diuron, Glyphosate, Gesapox 80, MSMA 72, Amine Salt, Isoctilic ester 48, Asulox 40, Goxone, Amigan 65, Merlin 75, Sulfatante 90, Unspecified Urea, P2O5, K2O Diesel Cane seed Solar energy Harvesting Fertilizing Planting Irrigating NaOH 50% in H2O HCl 30% in H2O | ha/year kg/ha·year kg/ha·year kg/ha·year kg/ha·year kg/ha·year kg/ha·year kg/day kg/ha·year GJ/day ha/year ha/year ha/year ha/year t/day t/day t/day t/day km t/day t/day t/day t/day t/day t/day km | Cane products Cane Agr. Wastes Emissions N2O N total to water Pesticides to water Pesticides to soil Sugar Molassesa Electr. to networka Alcohol Biogas Ash (P2O5 equiv.) Ash (K2O equiv.) Sludge/wastewater/cake (urea equiv.) Sludge/wastewater/cake (P2O5 equiv.) Sludge/wastewater/cake (K2O equiv.) Emissions to air PM10 Nitrogen oxides Emissions to water Wastewater Inorganic solids Total nitrogen Chemical oxygen demand Total phosphorus Emissions to soil Ashes Filter cake | t/day t/day kg/day kg/day kg/day kg/day t/day t/day GJ/day t/day t/day t/day t/day t/day t/day t/day t/day t/day t/day t/day t/day t/day t/day t/day t/day |

| 21 | [52] | Primary data (interview) Secondary data (databases) | Seed production and transport Fertilizer protection and transport Pesticide production and transport Machinery protection and maintenance Energy carriers and protection | NA | NA | Emission to air and water Solid emission | NA |

| 22 | [53] | Secondary data (databases) | Cultivation: Plastic cover Greenhouse Transportation: small truck, truck, sea, pre-cooling, and storage | fuel consumption, refrigeration, driving | L/t km kWh/m3/year | Waste management (CO2 emission, t/t) Paper, board, plastics CO2 emission from packaging, transportation, and storage Transportation Farm to packing house Packinghouse to wholesale | kg/t kg/t kg/t·km kg/t |

| 23 | [54] | Secondary data (databases) | Cattle manure Fuel use for various types of driving machinery and for different loads Low power Medium power High power Combine Willow harvester | N, P2O5, K2O fertilizer Slurry Power | mg/kg mg/kg kw | Willow Straw Wheat | mg/kg mg/kg mg/kg |

| 24 | [82] | Secondary data (both) | Yields for main products Straw yields and crop residues Moisture content Quantity of seed Use of machinery (number of passes) Sowing and harvest date Quantity of fertilizers Types of fertilizers in integrated systems Types of fertilizers in organic systems Pesticide applications Chemical seed dressing Machinery classes Tractor harvester Trailer machinery, tillage Slurry tank | Steel, unalloyed Steel, alloyed Other metals Rubber Plastics Others (glass, paints, etc.) | NA | Ammonia emissions Nitrate leaching P-emissions N2O emissions Heavy-metal emissions Pesticide applications Tractor combustion emissions | NA |

| 25 | [97] | Secondary data (both) | Inventory of agricultural inputs Agrochemical types and application rates Seeding rate Irrigation water intake Fuel consumption in agricultural operations Operating rate in machinery Agricultural machinery type Seed yield | Fertilizers and lime Nitrogen fertilizer (urea and diammonium phosphate) Phosphate fertilizer (diammonium phosphate) Potassium fertilizer (potassium chloride) Agricultural lime (calcic carbonate) Pesticides: Clopyralid, Haloxyfop, Picloram, Glyphosate, Linuron, Thiophanate-methyl, Prochloraz Seed Seed for sowing Irrigation requirement Irrigation water intake Diesel consumption: plowing, harrowing, crushing sowing, spraying, weeding, hilling/fertilizing harvest Tractor for field operations Tools and harvester Seed yield | kg N kg P2O5 kg K2O kg CaCO3 kg kg m3 kg kg kg t/ha | Ammonia (NH3) Nitrates (NO3) Nitrous oxide (N2O) Nitrogen oxides (NOx) Phosphates (PO4) Carbon dioxide (CO2) Glyphosate (main pesticide in rapeseed) Linuron (main pesticide in sunflower) | kg/xkg kg/xkg kg/xkg kg/xkg kg/xkg kg/xkg kg/xkg kg/xkg kg/xkg |

| 26 | [55] | Secondary data (databases) | Inventory data on wheat production (1995–2011, year−1). Wheat grown in paddy fields and Wheat grown in upland fields | Production costs Seed Chemical fertilizers Purchased manure Pesticides 49858 Fossil fuels 14760 Electricity Land improvement and irrigation Agricultural services Buildings Agricultural machinery Fossil fuels Heavy oil Diesel oil Kerosene Gasoline Motor oil Premixed fuel Calcium carbonate fertilizer Nitrogen balance Chemical fertilizers Purchased manure Atmospheric deposition Wheat straw (incorporated) Wheat Wheat straw (total) Denitrification Ammonia volatilization Surplus | yen·ha−1 L·ha−1 kg·ha−1 kg N·ha−1 | Wheat straw Wheat Air-emission sources included fossil fuel combustion, fertilizer application, and crop residue incorporation Emissions in fossil fuel combustion were calculated using the CO2, CH4, and N2O emission factors and the NOx and SOx emission factors The CO2 emission factor of calcium carbonate fertilizer on a weight the basis was 12% | |

| 27 | [105] | Primary data (real farm) Secondary data (previous studies and databases) | Farming Irrigation Soil management Pest treatment Fertilization Pruning Harvesting Olive oil mill Washing Milling Pressing Decantation Oil pomace mill Pitting Drying Solvent extraction Dysventilation and condensation | Water Pesticides Fertilizers Diesel Lubrification oil water Electric energy Water Electric energy Hexane | m3 kg kg kg L m3 kWh L kWh kg | Olive mill Wastewater Water from washing Virgin olive Exhausted pomace Pomace oil | L L L L kg kg |

| 28 | [56] | Primary data (interview) | Fertilization Pesticides Packaging Transportation | N, P, K Lubricating oils Seeds Tomatoes Sugar beets Tomato paste Raw sugar Sugar solution Vinegar Spice emulsion Salt Tomato ketchup Packaging system for tomato paste Packaging system for ketchup Transportation Shopping Household phase Electricity production Waste management | CH4, N2O, CO NMHC Biological oxygen demand (BOD) NOx Other organic compounds Water emissions Soil emissions | kg per FU kg per FU g per FU m3 per FU kg soil per FU | |

| 29 | [72] | Secondary data (databases) | Primary input and output flow from the case study farms during broccoli cropping Flow Inventory of retail-to-grave processes RDC Retailer Household | Occupation, arable land Plants (plugs) CO2 from air fixed in crop Tractor use Diesel (for field operations) Steel (spare parts replacement) Labor (labor-intensive operations) Diesel (for workers’ transport) Plastic (fleece, mulch…) Pesticides (unspecified) Fertilizers: N, P, K Manure/organic fertilizers Irrigation Bluewater, surface water Bluewater, groundwater Infrastructure (pipes, sprinklers…) Electricity (pumps) Input packed broccoli to RDC Diesel for transport to RDC From Spain From the UK Electricity RDC storage Input packed broccoli to retailer Diesel for transport to retailer Electricity retailer storage and display Solid waste from retailer to landfill Broccoli LDPE packaging Diesel for solid waste transport Input broccoli to household Petrol for transport to household Diesel for transport to household Electricity home storage Electricity cooking Natural gas cooking Tap water Solid waste from household to landfill Broccoli LDPE packaging Diesel for solid waste transport Cooking wastewater to WWTP Cooked broccoli (input to human excretion) | m2·year number kg CO2 hours L kg kg N, kg P2O5, kg K2O kg m3 m3 kg kWh kg kg kg MJ kg MJ kg kg kg MJ MJ MJ L kg kg kg L kg | Crop Soil emissions (literature) CO2 from soil CH4 from soil NH3 from soil NOx from soil N2O from soil NO3 from soil PO4 from soil Change in soil organic carbon (SOC) | kg kg CO2 kg CH4 kg NH3 kg NOx kg N2O kg NO3 kg PO4 kg C |

| 30 | [38] | Secondary data (databases) | Data inventory for the agricultural phase Data inventory for the processing phase (data refer to FU) | Seeds Compost from cow and horse manure Fosetyl-Al [Thio]carbamate-compounds [Sulfonyl]urea-compounds Diesel fuel Water Electricity for irrigation LDPE film (greenhouse) Land Salad (Valerianella locusta) Salad Electricity Water Sodium hypochlorite PP film | Mg g mg mg mg g dm3 kWh mg m2 g g kWh dm3 mg g | Emissions to air Carbon dioxide Carbon monoxide Nitrogen oxides Particulate hydrocarbons Dinitrogen monoxide Ammonia Benfluralin Fosetyl-Al Propamocarb Emissions to water Benfluralin Fosetyl-Al Propamocarb Emissions to soil Benfluralin Fosetyl-Al Propamocarb Salad bag (130 g) Salad scraps PP film waste Wastewater | g mg mg mg mg mg mg mg mg mg mg mg mg mg mg p g |

| 31 | [98] | Secondary data (previous studies) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 32 | [73] | Primary data (interview) Secondary data (databases) | Main characteristics of the life cycle inventory of the studied conventional (Con) and organic (Org) groups of fruit tree orchards crops in Spain. Data refer to 1 ha and year unless otherwise stated | Drip irrigation Surface irrigation Water use Electricity Presence of cover crops Machinery use Fuel consumption Mulching plastic Mineral nitrogen Mineral phosphorus Mineral potassium Manure Slurry Cover crop seeds Other organic fertilizers Total carbon inputs Total nitrogen inputs Synthetic pesticides Sulfur Copper Paraffin Natural pesticides Production Yield | % of cases % of cases m3 kWh % h L kg kg N kg P2O5 kg K2O mg mg kg kg kg kg kg active matter kg kg kg | Soil emissions Direct nitrous oxide Indirect nitrous oxide Methane Carbon | kg N2O kg N2O kg CH4 kg C |

| 33 | [57] | Secondary data (previous studies) | LCI to produce a single oil palm seedling | Electricity Diesel Polybag Water Fertilizer: N, P2O5, K2O Thiocarbamate Pyrethroid Organophosphate Dithiocarbamate Unspecified pesticide Urea/sulfonylurea Glyphosate Transportation Van | kWh L kg L kg kg kg kg kg kg kg kg tkm | Emissions to air NH3 N2O NO N2 Glyphosate Metsulfuron-methyl Glufosinate ammonium Paraquat Emissions to water Glyphosate Metsulfuron-methyl Carbofuran Glufosinate ammonium Paraquat Emissions to soil Glyphosate Metsulfuron-methyl Carbofuran Glufosinate ammonium Methamidophos Paraquat | kg/t FFB kg/t FFB Leached out and runoff g/t FFB |

| 34 | [58] | Primary data (real farm) Secondary data (databases) | Fertilizer doses, application emissions, and irrigation water (per ha) for lettuce and escarole crops in the open field (OF), plastic mulch (PM), plastic mulch combined with fleece system (PM F), and greenhouse (GH) systems. Characteristics of materials and electricity and diesel consumption (per ha) included in the inventory. PY polyethylene, PP polypropylene. | Fertilizer doses N optimum P2O5 K2O Mulch Fleece Main pipe 1 Main pipe 2 Main pipe 3 Secondary pipes Drip irrigation pipes (laterals) Pumps Electricity (pumps) Electricity (climate system) Diesel (crop management) | kg m2 m2 m m m m kg MJ MJ | Air emissions NH3-N NO2-N Water emissions NO3-N Irrigation water | kg kg m3 |

| 35 | [59] | Primary data (interview) | Principal inputs involved in the analysis of the “Delizie di Bosco del Piemonte” production chain for raspberries and giant American blueberries Nursery Rooting Mulching Covering Covering Fertigation system Fertigation system Fertigation Fertigation Nozzles Cold storage Field Soil preparation Soil preparation Mulching Total processes Mulching Irrigation system Irrigation system Irrigation Irrigation Base fertilization Total fertilization Covering Covering Plant protection treatments Post-harvesting Refrigeration Flow packaging Flow packaging Flow packaging | Substratum Black PE White PE Metal supports PVC piping PVC tubing Compost mix Water PVC Electrical energy Plow or cultivator Harrow Bed-former Diesel consumption PE sheeting PVC piping PVC tubing Water Electrical energy for the well Manure Compost White PE Metal supports p.a. Electrical energy Electrical energy PE tray PE wrapping | L·ha−1 kg·ha−1 kg·ha−1 kg·ha−1 kg·ha−1 kg·ha−1 kg·ha−1 m3·ha−1 kg·ha−1 kWh·m−3 h·ha−1 h·ha−1 h·ha−1 L·h−1 kg·ha−1 kg·ha−1 kg·ha−1 m3·ha−1 kWh·ha−1 t·ha−1 t·ha−1 kg·ha−1 kg·ha−1 kg·ha−1 kWh·kg−1 kWh·kg−1 g·kg−1 g·kg−1 | GWP (global warming potential) IPCC 100a Nonrenewable energy | kg CO2 eq MJ primary |

| 36 | [60] | Secondary data (databases) | Rice production tillage, growing, harvest | Machines, materials | Rice field Pollution (emissions) Product, byproduct Rice field product, byproduct, pollution | ||

| 37 | [36] | Primary data (survey) Secondary data (previous studies and databases) | Seed Power tiller diesel fuel use GHG intensity diesel fuel Power tiller life expectancy Power tiller weight Tractor L diesel fuel/h Tractor weight Embodied GHG of steel Bullocks Allocation to straw Tractors embodied emission Fertilizers Pesticides Manure Nitrogen use efficiency | kg CO2 eq·ha−1 L/h kg CO2 eq·L−1 Years kg L/h kg kg CO2 eq·kg steel−1 kg CO2 eq·h−1 kg CO2 eq·h−1 kg CO2 eq·kg−1 CO2-eq kg/kg CO2-eq·t−1 | Methane emissions Nitrous oxide emissions SRI CH4 and N2O emissions Electricity-based emissions from irrigation. Embodied GHG emissions associated with electricity Harvest Soil organic carbon | kg CO2-eq·ha−1 kg CO2 eq·ha−1 kg CO2 eq·ha−1 kg CO2 eq·kWh−1 GHG emissions·h−1 kg CO2 eq·ha−1 | |

| 38 | [61] | Primary data (interview) | Primary production Grading and packing Regional distribution center Supermarkets | Piscicide production N fertilizer production Tools Machinery Water Compost Field diesel Packaging Electricity Electricity Pallets and packaging Electricity Pallets and packaging | NA | Land-use change Direct emission Nitrate Nitrous oxide Ammonia Waste Waste waste | NA |

| 39 | [62] | Primary data (reports) Secondary data (previous studies) | Orchard establishment inputs Agricultural stage inputs Retail stages inputs Consumption stages inputs | Water Electricity Diesel Machinery Materials Transport | L kW kg kg kg tkm | Apple Peach (NPK) NOx N2O Machinery production emissions and diesel consumed for machinery operations | kg kg |

| 40 | [74] | Secondary data (both) | Annual chemical inputs for managing a mature orange grove in Florida Chemical mowing Herbicide spray Pesticide spray Fertilization Use of energy products for undertaking various cultural activities at a mature orange grove in Florida Site preparation Management of a mature orange grove | Roundup weather max Solicam 80 DF Karmex WP Roundup weather max Prowl H20 Simazine 4L Roundup weather max Mandate Direx 4L Roundup weather max Spray oil Copper (Kocide 3000) Agrimek (if no mite resistance) Zn, Mn, B Lorsban 4EC Copper (Kocide 3000) Spray Oil MgO Dolomite Mowing (mechanical) Mowing (chemical) Discing Soil shaping Planting Mowing (mechanical) Mowing (chemical) Fertilization (16–0–16–4 MgO) Fertilization (lime) Herbicide Pesticide Conditioning Topping Hedging Brush removing Chopping brush Dead tree removal Irrigation Fruit picking Transporting pickers Roadsiding fruit | mL/ha kg/ha kg/ha mL/ha mL/ha mL/ha mL/ha mL/ha mL/ha mL/ha L/ha kg/ha mL/ha kg/ha mL/ha kg/ha L/ha kg/ha kg/ha | Emission from energy use Emission from material use | g CO2 eq./FU g CO2 eq./FU |

| 41 | [75] | Primary data (survey) Secondary data (databases) | Principal inputs involved in the production and distribution chain (scenarios 1 and 2) for strawberries Nursery Rooting Mulching Covering Covering Fertigation system Fertigation system Fertigation Fertigation Cold storage Field Soil preparation Soil preparation Mulching Total processes Mulching Irrigation system Irrigation system Irrigation Irrigation Base fertilization Total fertilization Covering Covering Plant protection treatments Post-harvesting Refrigeration Flow packaging Flow packaging | Substratum Black PE White PE Metal supports PVC piping PVC tubing Compost mix Water Electrical energy Plow or cultivator Harrow Bed-former Diesel consumption PE sheeting PVC piping PVC tubing Water Electrical energy for the well Manure Compost White PE Metal supports p.a. Electrical energy PE tray PE wrapping | L·ha−1 kg·ha−1 kg·ha−1 kg·ha−1 kg·ha−1 kg·ha−1 kg·ha−1 m3·ha−1 kWh·m−3 h·ha−1 h·ha−1 h·ha−1 L·h−1 kg·ha−1 kg·ha−1 kg·ha−1 m3·ha−1 kWh·ha−1 t·ha−1 t·ha−1 kg·ha−1 kg·ha−1 kg·ha−1 kWh·kg−1 g·kg−1 g/kg | GWP (global warming potential) IPCC 100a Non-renewable energy | kg CO2 eq·UF−1 kg CO2 eq·UF−1 |

| 42 | [93] | Secondary data (databases) | Life cycle inventory data for watermelon cultivation (per ha). Characterization factors of inputs used in watermelon production. Parameters and coefficients of objective functions. | 1. Human labor (man/woman) 2. Diesel fuel Plowing Discing Ditcher 3. Machinery Tractor and self-propelled Implement and machinery 4. Fertilizers Nitrogen (N) Phosphate (P2O5) Potassium (K2O) Microelements 5. Farmyard manure 6. Electricity 7. Chemicals Fungicide Insecticide 8. Seeds 9. Plastics Machinery Diesel fuel Chemical fertilizers (a) Urea (b) Phosphate (P2O5) (c) Potassium (K2O) Manure Pesticides Electricity Plastics Constanta N K2O P2O5 Manure Diesel Electricity Seed Chemicals Machinery Plastic Water | h L kg kg kg kWh kg kg kg kg L kg kg kg kWh kg kg kg kg kg L kWh kg kg kg kg MJ | Watermelon On-farm emissions N fertilizer Diesel fuel | kg kg MJ |

| 43 | [76] | Secondary data (databases) | NA | Mulching film for pot production (PP) Wind-stopper (galvanized iron) Hydraulic pipe/micro pipe (PEHD/PELD/PVC) Taps (PEHD/PVC) Tunnel cover Tunnel structure (galvanized iron) Poles (galvanized iron/wood) Sprinklers (galvanized iron) Hydraulic fittings (PE) Solenoid (PVC) Support canes (bamboo) Black clip (PP) Plates PP black wire (nylon) Green thread (PVC) Iron wire (galvanized iron) Elastics/hooks/butterfly valve (PE) Irrigation bar (aluminum) Block (concrete) Covering (gravel/volcanic stones) Raincoat towel (PVC/PP/PEHD) A chain-link fence (galvanized iron) Centrifugal/submersible pump (Cast iron/stainless steel) Electrical panel (PEHD/copper) Burlap (jute) String (sisal) Wire basket (iron) Plastic net (PP) Plastic box (PP) | NA | Total yearly GHG emissions are divided into different categories (kg CO2 eq/m2/year) NFS ¼ nursery farm structure; AGS ¼ aboveground structures; IC ¼ inputs of cultivation; P ¼ packaging; EFS ¼ emissions from soil | NA |

| 44 | [106] | Secondary data (databases) | NA | Strawberry (nursery field) PE punnet PE plastic film End-of-life Transport Electricity | NA | Nonrenewable energy IPCC GWP 100a | MJ·UF−1 kg CO2 eq·UF−1 |

| 45 | [79] | Primary data (surveys) | Gasoline at the refinery (US) Diesel at the refinery (US) Urea ammonium nitrate (UAN), (US) Monoammonium phosphate (US) Waxes/paraffin at the refinery (US) Potassium sulfate, at regional storage (Europe) Mined from natural sources, only transport is modeled Fishmeal Potassium carbonate, at the plant (Europe) Sulfur (elemental) at the refinery (US) Yeast (surrogate data, yeast produced as a co-product) Serenade is a strain of Bacillus subtilis (Swiss) Glyphosate, at regional storehouse (Europe) Diphenyl-ether compounds at regional storehouse (Europe) Phtalamide compounds at regional storehouse (Europe) Pesticide unspecified, at regional storehouse RER Developed based on Recycled Organics Unit (2006), updated with regionally appropriate LCI datasets Electricity grid mix (West US) Modeled based on power rating and hours of operation (California model) and Diesel (US) Truck (combination)—diesel rail (US diesel) | Gasoline Diesel Urea ammonium nitrate (UAN) Monoammonium phosphate (MAP) Adjuvant (stylet oil) Potassium sulfate Phytamin component: seabird guano Phytamin component: fishmeal Phytamin component: potassium carbonate Sulfur dust Serenade Roundup Ultra Max Goal 2XL Chateau, Pristine (Boscalid and Pyraclostrobin) Compost production Electricity Equipment operation Truck, rail shipping International shipping | NA | IPCC Tier 2 emissions were used to calculate the field-based N2O emissions from fertilizer and compost application and vineyard plant matter, including leaves, clippings, and cover crop residue following mowing (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change 2006; Point et al. 2012). | NA |

| 46 | [63] | Secondary data (databases) | Fossil energy life cycle factors for agricultural inputs | Nitrogen Phosphorous Potassium Lime Sulfur Micronutrients Cover crop seed Herbicide Insecticide Fungicide Gasoline Diesel Plastic Agriculture machinery Electricity | MJ/kg MJ/kg MJ/kg MJ/kg MJ/kg MJ/kg MJ/kg MJ/kg MJ/kg MJ/kg MJ/L MJ/L MJ/kg MJ/h MJ/kWh | Direct N2O emissions from agricultural Emissions (e.g., volatile organic compound (VOC), carbon monoxide (CO), carbon dioxide (CO2), nitrogen monoxide (NO), nitrogen dioxide (NO2), nitrous oxide (N2O), particulate matter (PM10), particulate matter (PM2.5), sulfur dioxide (SO2), sulfur trioxide (SO3), methane (CH4)) Emissions and energy use in transportation | NA |

| 47 | [24] | Secondary data (databases) | Electricity production Oil production Plastic P1 production Gutter A1 production Gutter A1 use and demolition Incineration of P1/A1 Recycling process Material B production Product system Electricity production Oil production Plastic P2 production Gutter A2 production Gutter A2 use and demolition Incineration of P2/A2 Recycling process Material B production Product system | Electricity Oil Plastic P1 Produced A1 Installed A1 Incinerated P1/A A1 in recycling Avoided material B | MJ kg kg 100 m 100 m kg kg kg | CO2 CH4 N2O NOx SO2 | kg kg kg kg kg |

| 48 | [64] | Secondary data (databases) | Planting and maintenance Harvesting and baling Receiving/storage Drying and chopping Pelletizing/cooling/screening Packing and storage | Seed Fertilizer Pesticide/herbicide Land use Machinery Fuel Machinery Fuel Electricity Air Plastic bag | kg·ha−1 ha kg·ha−1 ha MJ MJ kWh | Strawbale CO2 N2O CH4 SO2 PO4 Pellet | kg g CO2 eq g CO2 eq g CO2 eq g CO2 eq g SO2 eq g PO4 eq kg |

| 49 | [65] | Primary data (real farm) Secondary data (database and previous studies) | Production characteristics Greenhouse plastic Water consumption Growing media Fertilizer Pesticide Electric power Diesel and petrol Post-harvest chemicals | Plastic consumption Rejected steams Power consumption Diesel Petrol Cardboard box Bunching paper Rubber band Strapping roll Water Substrate (red ash) Pesticide Pesticide empty containers Calcium nitrate Other fertilizers Acids Post-harvest chemicals Post-harvest water use | g # kWh g g g g g g L g g g g g g g L | Roses CO2 CH4 N2O | Bunch g g g |

| 50 | [32] | Secondary data (database and previous studies) | Production of crop inputs, production and use of diesel, and field emissions | N (ammonium nitrate) P2O5 (triple superphosphate K2O (potassium chloride) CaO Seed for sowing Pesticide (active ingredient) Diesel Natural gas (for grain drying) Agricultural machinery Grain dry matter yield Stem/straw dry matter yield Sugar/tuber dry matter yield Followed bycatch crop (%) Succeeding crop NO3-N emitted | kg/ha kg/ha kg/ha kg/ha kg/ha kg/ha kg/ha kg/ha kg/ha kg/ha kg/ha kg/ha kg/ha | Hemp Sunflower Rapeseed Pea Wheat Maize Potato Sugar beet NH3-N NO3-N N2O-N PO4-P | ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha emissions/kg emissions/kg emissions/kg emissions/kg |

| 51 | [100] | Secondary data (database and previous studies) | Infrastructure:

| Mineral fertilizers Organic fertilizers Pesticides Seed Feed | kg kg kg kg kg | Potatoes organic, at the farm Rapeseed extensive, at the farm Wheat grains conventional, Barrois, at the farm Carbon dioxide CO2 Sulfur dioxide SO2 Lead Pb Methane CH4 Benzene C6H6 Particulate Matter PM Cadmium Cd Chromium Cr Copper Cu Monoxide N2O Nickel Ni | kg kg kg g/kg g/kg g/kg g/kg g/kg g/kg g/kg g/kg g/kg g/kg |

| 52 | [85] | Primary data (survey) | Tractors and equipment Buildings required energy Carriers Mineral fertilizer Tree nursing Constructions for hail protection Water for irrigation Application of compost | Pesticides Fungicide Insecticide Herbicide Other plants treatment products Fertilizers N-fertilizer Ca- and Mg-fertilizer (kg Ca, Mg) K-fertilizer P-fertilizer Machinery Diesel Tractor Equipment Buildings | kg active matter kg N kg K2O kg P2O5 kg kg kg m2 | Total receipts Yield | USD·ha−1 t·ha−1 |

| 53 | [89] | Secondary data (databases) | Pesticide Seeds PK fertilizer N fertilizer Machinery mulching Machinery irrigation Machinery pesticide Machinery fertilization Machinery weeding Machinery soil tillage Machinery harvest Machinery sowing | Energy input | MJ eq | CH4 N2O CO2 Ph NH3 NO−3 | t CO2 eq·ha−1·year−1 kg N eq·ha−1·year−1 t CO2 eq·ha−1·year−1 kg N eq·ha−1·year−1 kg N eq·ha−1·year−1 kg N eq·ha−1·year−1 |

| 54 | [77] | Primary data (farmers) Secondary data (databases and references) | Transportation Fertilization Pesticides Irrigation | Inputs 1. Diesel fuel 2. Transportation 3. Human labor 4. Chemical fertilizers (a) Nitrogen (b) Phosphate (c) Potassium (d) Sulfur 5. Manure 6. Chemical pesticides (a) Fungicide (b) Insecticide 7. Irrigation water The total energy input | L kg h kg kg kg m3 MJ | Grape Ammonia (NH3) Ammonia (NH3) Benzene Benzo (a) pyrene Cadmium (Cd) Carbon dioxide (CO2) Carbon dioxide (CO2) from urea. Carbon monoxide (CO) Chromium (Cr) Copper (Cu) Diazinon Dinitrogen monoxide (N2O) Dinitrogen monoxide (N2O) Dinitrogen monoxide (N2O) from atmospheric deposition Hydrocarbons (HC, as NMVOC) Methane (CH4) Nickel (Ni) Nitrate (NO3) Nitrogen oxide (NOx) Nitrogen oxides (NOx) PAH (polycyclic hydrocarbons) Particulates (b2.5 mm) Phosphorus emissions from fertilizers application emitted into groundwater. Selenium (Se) Sulfur dioxide (SO2) Tillet Zinc (Zn) | kg kg·ha−1 kg·ha−1 kg·ha−1 kg·ha−1 kg·ha−1 kg·ha−1 kg·ha−1 kg·ha−1 kg·ha−1 kg·ha−1 kg·ha−1 kg·ha−1 kg·ha−1 kg·ha−1 kg·ha−1 kg·ha−1 kg·ha−1 kg·ha−1 kg·ha−1 kg·ha−1 kg·ha−1 kg·ha−1 kg·ha−1 kg·ha−1 kg·ha−1 kg·ha−1 |