Abstract

This study presents an analysis of 40-years (1981–2020) precipitation climatology of ERA5-Land and E-OBS gridded datasets over Greece. The analysis focused on trends in total annual, low, moderate, and extreme precipitation—as well as number of rainy days—corresponding to the climatically diverse geographical areas of Greece. Substantial differences were found in the results between the two datasets that could be attributed to the nature of data sources. In general, ERA5-Land revealed slightly negative trends in total precipitation amount, an increase in low and moderate precipitation intensity, and an overall positive trend in extreme precipitation intensity. E-OBS demonstrated a rather negative trend in total precipitation amount, a clear decline in Crete in low precipitation intensity, a positive trend in northern Greece, and a negative trend in Southern Greece and Crete for moderate intensity, while no clear trend was revealed for most parts of Greece for extreme precipitation intensity. Regarding the corresponding results for the number of rainy days (NRD), a significant reduction was evident for E-OBS data and a slight increase for ERA5-Land data for total precipitation amount. Analysis of low precipitation intensity indicated a slight increase for ERA5-Land and an overall reduction for E-OBS. The differences are less pronounced for moderate precipitation intensity, while for extreme precipitation intensity, differences were considered as rather localized. Finally, both datasets showed positive trends in northern or mountainous geographical areas while exhibiting controversial results mainly over southern and coastal zones.

1. Introduction

Precipitation is a key environmental parameter for the assessment of climate and its impact on hydrological, water resource management and other related studies. Rain gauge stations are considered as the most suitable equipment for monitoring. However, such stations, providing rather point measurements, are not always available in many regions, while its installation is not always possible for areas located in high altitudes and/or remote areas [1]. Thus, it is difficult to monitor adequately the spatio-temporal assessment of precipitation. On the other hand, satellite-derived data and gridded precipitation products could overcome the geographical gap of data, with known, however, issues in terms of accuracy and spatial analysis [2].

Gridded precipitation products, such as the ECMWF Reanalysis v5 (ERA5) and E-OBS, have been developed to provide long-term precipitation data at both regional and global coverage scales. Accuracy assessment studies of such products have been performed at different geographical and climatic conditions [3,4,5,6,7].

Previous studies used the analysis of long-term ERA5 reanalysis precipitation data to identify spatio-temporal characteristics of precipitation over the Mediterranean region [8,9,10,11]. On the other hand, Retalis et al. [11] evaluated EOB-S climatology maps (monthly, seasonal and annual) and the Precipitation Condition Index against TRMM data for the Mediterranean region (1998–2012), depicting relative high correlation over Spain, Portugal, southern France, the Balkan region, and Cyprus, while considerably lower values were noticed for many parts of Italy, Turkey, and Greece, and a few regions of the Iberian Peninsula. Sakalis [12] examined the trend of annual precipitation in the SE Mediterranean region for the period 1990–2021 based on the analysis of precipitation records obtained from the gridded monthly data of the Climate Research Unit (CRU) Time Series (TS) v. 4.05. He found a positive trend in precipitation in Greece that is profound, especially in the last two decades.

In Greece, several precipitation studies have been performed based on rain gauge data [13,14,15], satellite precipitation products [16,17,18,19,20], and reanalysis data. Regarding the latter, Alexandridis et al. [21] evaluated the performance of ERA5 and ERA5-land datasets for a 10-year period (2010–2020) against rain gauge stations. They found that their performance was spatially varied, while ERA5-land exhibited higher accuracy and lower biases compared to ERA5. Kourtis et al. [22] studied the spatial variability and the trends of the annual precipitation in Greece using monthly ERA5 reanalysis precipitation dataset for the period 1940–2022. Their results showed non-significant declining trends in annual precipitation within the whole study area, although significant trends were noticed in the Aegean Islands, western Crete, and western mainland of Greece.

Leščešen et al. [23] used ERA5 land data from 1961 to 2020 to study extreme precipitation changes observed over the whole of Southeast Europe. They found in Greece, during the winter season (December–January–February), a positive precipitation trend in North Macedonia, while extreme precipitation events were noticed in the Central Peloponnese region. During the spring season (March–April–May), a statistically significant positive trend was observed over the western parts of North Macedonia, while statistically significant changes were noticed in the Southeastern parts of Greece, like central parts of Euboea Island and the Attica peninsula.

E-OBS and Regional Climate Models were used to analyze precipitation trends over the Thessaly Plain, concluding that E-OBS provided a reliable historical reference [24]. Moreover, Mavromatis et al. [25] found that E-OBS performed well in capturing variability and extreme precipitation indices. The assessment of eight precipitation datasets, including ERA5-Land and E-OBS, was evaluated against records from 304 gauging stations across Greece on a daily and a monthly timescale for the period 1984–2016 [26]. Varlas et al. [27] used ERA5 monthly precipitation data from 1950 to 2020 to estimate annual significance over Greece. They found that declining trends were more distinct in winter, specifically over western and eastern Greece.

In a recent study, Lagouvardos et al. [28] analyzed the trends of essential climate variables in Greece using the ERA5-Land dataset for the period 1991–2020. They found that an increasing amount of annual precipitation was noticed in several regions of Greece. Moreover, an establishment of an increasing trend in the number of days with heavy precipitation (>20 mm) was noticed in several geographical regions of Greece.

However, a comprehensive analysis of precipitation both in terms of intensity and rainy days in accordance with climatic zones has not been performed yet. Thus, this study aims to fill in this gap, presenting an analysis of trends in precipitation over Greek regions, in terms of total annual precipitation, as well as low, moderate, and high precipitation intensity classes, along with the corresponding number of rainy days for each case, accordingly, placing emphasis on the climatic zones of Greece.

2. Data and Methodology

2.1. Study Area

Greece is located in the SE Mediterranean region and is defined by its complex topography and extensive coastline. The Pindus Mountain range, expanding from northwest to the southwest, plays a significant role in precipitation formation and is associated weather patterns. Greece is characterized by strong spatio-temporal contrasts in precipitation, with high variability at multiple timescales, often enhanced by orography. Thus, western Greece and the Ionian islands frequently experience extreme precipitation events. The main precipitation period in Greece extends from autumn to spring, while summer is considered as a rather dry period.

According to the Köppen climate classification, Greece has 11 climates, the most in Europe for its size [29]. However, it was hard to depict/illustrate changes in precipitation trends since variations in classes were identified within the administrative boundaries (prefectures). To overcome this problem, we adopted the classification scheme suggested by the Technical Guidelines of the Technical Chamber of Greece [30,31]. Greece is, thus, divided into four climatic zones based on Heating Degree Days (DD). The reference temperature is 18 °C [32]. Table 1 presents the definition of variables used for each climatic zone.

Table 1.

Definition of variables used for each climatic zone [33].

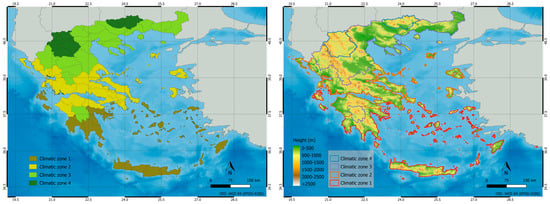

Table 2 presents the prefectures that fall into the four climatic zones (from the warmest to the coldest), while Figure 1 illustrates the climatic zones and the topography of Greece. In each prefecture, areas located 109 at an altitude exceeding 500 m are classified into the next colder climate zone, with the exception of zone 4, where all areas are included regardless of altitude. The part of the prefecture of Arcadia that falls within climate zone 3 and the part of the prefecture of Serres (NE part) that falls within climate zone 4 include all areas that have an altitude of over 500 m.

Table 2.

Prefectures of Greek territory by climate zone.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the climatic zones (left) and topography (right) of Greece.

Overall, Greece presents a predominantly Mediterranean climate, characterized by mild and wet winters and hot, dry summers. Nevertheless, substantial regional variability is observed due to the country’s diverse relief and extensive latitudinal range. Coastal and insular regions generally experience milder conditions, whereas inland and mountainous areas are influenced by continental climatic features, including lower temperatures and increased precipitation [34,35]. In the southern and coastal regions corresponding to climatic zone 1, winters are mild and summers are particularly hot and dry, with relatively low annual precipitation. Zone 2, which includes a large part of central and southern mainland Greece, is marked by moderate winter conditions and higher annual rainfall compared to zone 1. Zone 3, encompassing parts of Thessaly, Epirus, and central Macedonia, exhibits more pronounced seasonal contrasts, with colder winters and increased precipitation, often enhanced by orography [36]. Finally, zone 4, which includes northern and mountainous areas such as Western Macedonia and parts of Eastern Macedonia and Thrace, experiences cold winters, frequent frost and snowfall, and annual precipitation amounts exceeding 1000 mm [37]. This climatic heterogeneity plays a crucial role in shaping local hydrometeorological conditions, influencing regional energy demand and the frequency of extreme weather events.

2.2. Data

The extensively validated E-OBS and ERA5 Land databases, covering a long period of 40 years from 1981 to 2020, were used in this analysis.

2.2.1. ERA5-Land Data

ERA5-Land is a global, high-resolution reanalysis dataset, including numerous crucial atmospheric parameters, produced by the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF). Regarding precipitation, it provides consistent and gap-free hourly estimates of total precipitation from 1950 to near real-time. The difference with typical observational data is that it is generated by combining model data with observations from across the world into a complete and coherent dataset using data assimilation. This makes it especially valuable for studying land-surface processes and climate trends where direct measurements are sparse or unavailable. The primary strength of ERA5-Land is its global coverage, high spatial resolution (approximately 9 km), and long-term consistency. Because it is a reanalysis, it eliminates the gaps and inhomogeneities that plague in situ observational networks, making it ideal for global scale studies and model evaluation. However, as a model-based product, its accuracy is not uniform across the globe and is highly dependent on the quality of the assimilated observations and the performance of the underlying model [38].

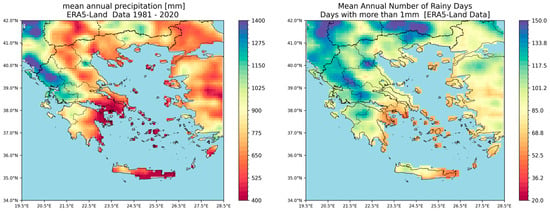

ERA5-Land is considered valuable for the Mediterranean basin due to its ability to provide a spatially complete picture over a region characterized by complex topography (mountain ranges like the Alps, Apennines, and Atlas) and a mix of land and sea, where ground-based observations are unevenly distributed. Its high resolution is a significant improvement over its predecessors (ERA5, ERA-Interim) for capturing the steep gradients found in coastal areas and mountainous terrain. Here, daily amounts are used. It should be noted, however, that ERA5-Land precipitation data often present significant biases in terms of mean precipitation (overestimation) and extreme precipitation intensities (underestimation) [20,39]. Figure 2 presents the mean annual precipitation derived from ERA5-Land data, and the mean annual number of rainy days for the whole period of study. The spatial distribution places the lowest values of yearly rainfall across the south and southeast regions (approximately 400 mm/year), while the highest values are located in the north-western mountainous area, reaching more than 1400 mm/year. This pattern reflects orographic enhancement influencing the region. Regarding mean NRD, there is a similar pattern with the lowest values of almost 50 days in the southeast and the maximum, that reaches 150 in the north and north-western regions.

Figure 2.

Mean annual precipitation (left) and mean annual NRD (right) calculated from ERA5-Land data for the period 1981–2020.

2.2.2. E-OBS Data

E-OBS is a land-surface observational dataset for Europe, developed and maintained by the European Climate Assessment and Dataset (ECA&D) project. It provides daily gridded fields of essential climate variables like temperature and precipitation, covering the period from 1950 onwards. Its key characteristic is that it is primarily based on in situ station measurements from the ECA&D database, which are interpolated to a regular grid using sophisticated statistical techniques. This means E-OBS is closer to “actual measurements” than model-based reanalysis datasets like ERA5-Land. The main advantage of E-OBS is that it provides a best estimate of the observed climate at the surface, making it a crucial reference dataset for validating climate models, reanalysis data, and climate monitoring studies specifically over Europe. Its reliance on real station data gives it high credibility for capturing observed extremes and local patterns, provided the station network is dense enough. A significant limitation of E-OBS is that its quality and effective resolution are directly tied to the density of the underlying station network, which varies across Europe and over time. This can lead to underestimation of extremes (especially precipitation) in data-sparse regions and generally results in a smoother representation of climate fields compared to the reality or a high-resolution model [40].

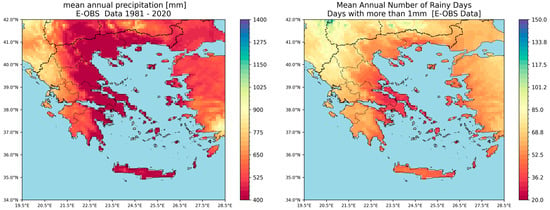

In the Mediterranean, the quality of E-OBS in the Mediterranean is directly impacted by the density of the corresponding rain gauges, which is generally sparser, compared to central and northern Europe. This sparsity can lead to a smoothing effect, particularly for precipitation, causing an underestimation of extreme values and reduced accuracy in representing the sharp climatic gradients found in mountainous areas. The version used is 30.0e (it should be noted that according to the E-OBS dataset documentation, 48 HNMS, mostly airport stations that are unevenly distributed, are used over Greece, but not all of them cover the whole study period; sixteen cover the whole period, eighteen reported until 2004, two until 2011, eleven were installed during the 90s, and one the period 2004–2020). Figure 3 presents results corresponding to Figure 2, mean annual precipitation, and NRD for the 1981–2020 period, calculated from the E-OBS data. While the overall spatial pattern for the mean rainfall is generally comparable, E-OBS yields notably lower precipitation totals, with maxima hardly reaching 1000 mm/year. Analogous is the pattern for the mean NRD where the values vary from almost 30 to hardly 100 days per year.

Figure 3.

Mean annual precipitation (left) and mean annual NRD (right), calculated from E-OBS data for the period 1981–2020.

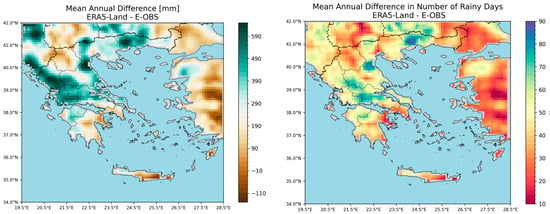

Indeed, comparing directly the two climatologies (Figure 4), there are significant differences, located mainly in the mountainous areas, where the maximum positive biases (ERA5-Land minus E-OBS) for precipitation exceed 500 mm/year, whereas on the other hand, negative differences—where E-OBS reports higher values than ERA5—generally remain below 100 mm/year. A similar pattern is evident for the NRD differences; however, in this case, no negative values appear, indicating that ERA5-Land data systematically yields a greater number of rainy days across the entire region. The maximum difference reaches approximately 90 days per year. These discrepancies likely stem from structural distinctions between reanalysis data and observation-based gridded products, including differences in interpolation methods, data assimilation, and the representing of orographic precipitation. This comparison clearly affects climatic trends, since each dataset presents different magnitude and spatial expression of long-term changes in precipitation. It is very important to understand the structural differences between the two products to better describe the trend signals and evaluate the robustness of climate diagnostics.

Figure 4.

Mean annual difference in precipitation (left) and NRD (right) between the two datasets (ERA5-Land minus E-OBS) for the period 1981–2020.

2.3. Precipitation Indices

For each grid cell of both datasets and for each year, the following indices were computed:

- Total Annual Precipitation: Sum of daily values over the year;

- Number of Rainy Days (NRD): Count of rainy days with precipitation ≥ 1 mm;

- Precipitation Intensity Classes: Rainy days categorized as low (1–10 mm/day), moderate (10–20 mm/day), and high (>20 mm/day);

- Precipitation anomaly: Calculation of precipitation anomaly as averaged indices calculated for each climatic zone by averaging over all grid points within the respective boundaries.

Data processing for the calculation of the above precipitation indices was performed with the CDO software (v.2.3.0) [41].

Trend analysis (see Equation (1)) for each dataset, based on the above assumptions, was calculated, in an effort to identify areas that are more vulnerable to possible future drought for each one of the climatic zones. The statistical significance of the trend (p-value < 0.05) is the result of the Mann–Kendall test, applied to each grid point’s 40-year time series.

Equation (1) presents the calculation of b parameter in the “x = a + b*t” equation, assuming x is precipitation and t is time (formula from CDO user’s guide).

3. Results

3.1. Total Annual Precipitation

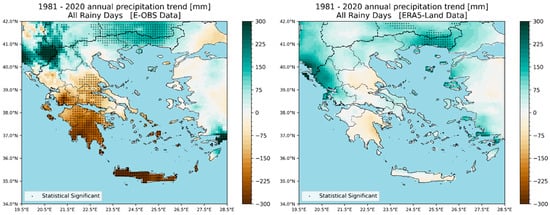

Figure 5 presents the trends in annual precipitation for both E-OBS and ERA5-Land databases, while Figure 6 shows the trends of the corresponding number of rainy days (NRD), accordingly.

Figure 5.

Trend of total annual precipitation for the period 1981–2020. Black dots indicate statistically significant trends.

Figure 6.

Trend of annual NRD for the period 1981–2020. Black dots indicate statistically significant trends.

At a first glance, there is a significant difference between the two datasets, regarding mainly the central and southern parts of Greece. While both datasets show a negative trend in these areas, E-OBS (on the left) shows a significant decline in annual precipitation, amounting to a reduction that reaches 300 mm over the whole period. In contrast, ERA5-Land negative values hardly reach 50 mm. Additionally, the north-western region of Greece presents a slightly negative trend according to the E-OBS values, whereas the ERA5-Land values suggest a slightly positive trend for the same area.

Similarly, the comparison of the two datasets shows even more discrepancies regarding the trend in NRD. Specifically, the analysis of the E-OBS data shows a pronounced reduction in the days with recorded rainfall, particularly evident in Central and Southern Greece. Conversely, the ERA5-Land dataset presents a slight increase in the number of rainy days across nearly the whole country.

3.2. Low Precipitation Intensity

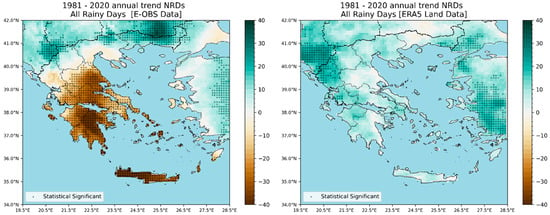

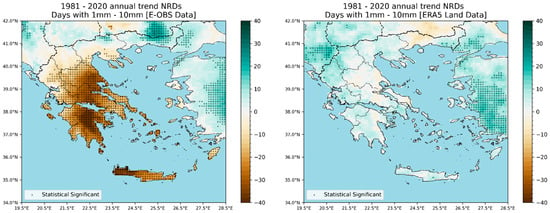

Figure 7 presents the trends of low precipitation intensity (1 mm < P < 10 mm) for both E-OBS and ERA5-Land databases, while Figure 8 shows the trends of the corresponding number of rainy days (NRD), accordingly.

Figure 7.

Trend of annual precipitation for the period 1981–2020, considering only days with low precipitation intensity.

Figure 8.

Trend of annual NRD for the period 1981–2020, considering only days with low precipitation intensity.

Analyzing only the low precipitation intensity days (Figure 7 and Figure 8), the differences between the two datasets persist; however, for annual precipitation, the contrast is less pronounced this time, except over Crete where E-OBS again indicates a clear reduction in annual precipitation close to 200 mm. On the other hand, ERA5-Land again presents an increase in annual trend across the entire country, including Crete.

With respect to the number of rainy days (defined this time as days with precipitation between 1 mm and 10 mm), the contrast in Figure 5 is notable. E-OBS reveals a “loss” of up to 40 days for the whole study period, particularly across central and southern Greece, with very few grid cells showing a positive trend. On the other hand, the ERA5-Land data show again a slight increase, with values rarely passing 10 days though.

3.3. Moderate Precipitation Intensity

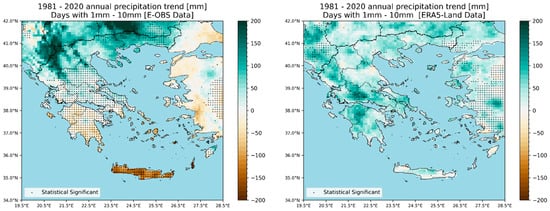

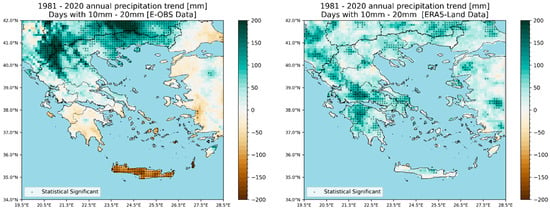

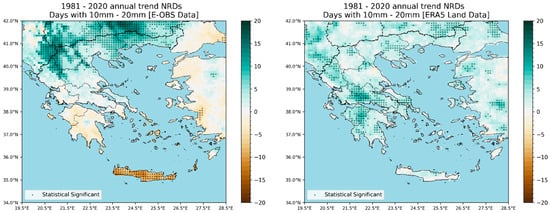

Figure 9 presents the trends of moderate precipitation intensity (10 mm < P < 20 mm) for both E-OBS and ERA5-Land databases, while Figure 10 shows the trends of the corresponding number of rainy days (NRD), accordingly.

Figure 9.

Trend of annual precipitation for the period 1981–2020, considering only days with moderate precipitation intensity.

Figure 10.

Trend of annual NRD for the period 1981–2020, considering only days with moderate precipitation intensity.

Focusing on the days with moderate precipitation intensity (Figure 7 and Figure 10), the differences between the two datasets appear mixed. E-OBS shows higher positive values in the annual precipitation trend (Figure 7) for areas in northern Greece, with values surpassing 150 mm. In contrast, ERA5-Land gives positive values across most of the country, though rarely exceeding 100 mm. Southern Greece and Crete have mostly negative values for E-OBS, with the largest island of the country displaying reductions up to 200 mm.

With respect to the number of rainy days (defined here as days with precipitation between 10 mm and 20 mm), the contrast in Figure 10 is less pronounced. E-OBS reveals a “gain” of more than 10 days over parts of Northern Greece, no trend or negative for southern Greece, and clearly negative over Crete. On the other hand, the ERA5-Land data suggest again a slight increase covering almost the entire country, with values hardly reaching 10 days.

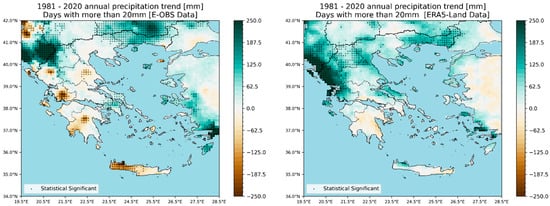

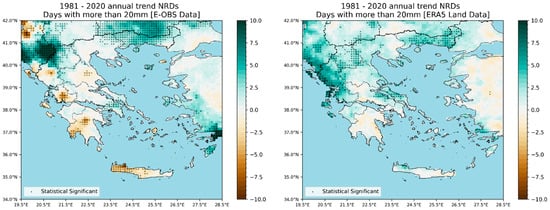

3.4. Extreme Precipitation Intensity

Figure 11 presents the trends of extreme precipitation intensity (P > 20 mm) for both E-OBS and ERA5-Land databases, while Figure 12 shows the trends of the corresponding number of rainy days (NRD), accordingly.

Figure 11.

Trend of annual precipitation for the period 1981–2020, considering only days with extreme precipitation intensity.

Figure 12.

Trend of annual NRD for the period 1981–2020, considering only days with extreme precipitation intensity.

Considering days with extreme precipitation intensity (Figure 11 and Figure 12), the differences between the two datasets again are mixed; however, they are more localized. E-OBS shows higher positive trend values in annual precipitation (Figure 11) over limited areas in northern Greece, with values surpassing 200 mm. A substantial part of the country has no clear trend, while some regions, including once again Crete, exhibit negative trends. In contrast, ERA5-Land gives positive values across most of the country, reaching 250 mm in some locations, while parts of Southern Greece and Crete have near zero or slightly negative trends.

Regarding the number of rainy days (defined here as days with precipitation higher than 20 mm), the contrast in Figure 12 is less pronounced. E-OBS reveals a “gain” of more than 10 days over parts of Northern Greece, and little-to-no trend or even negative across southern Greece and Crete. On the other hand, the ERA5-Land data suggest again a modest overall increase, with values that generally hardly exceed 5 days, and most of Southern Greece and Crete showing no clear trend.

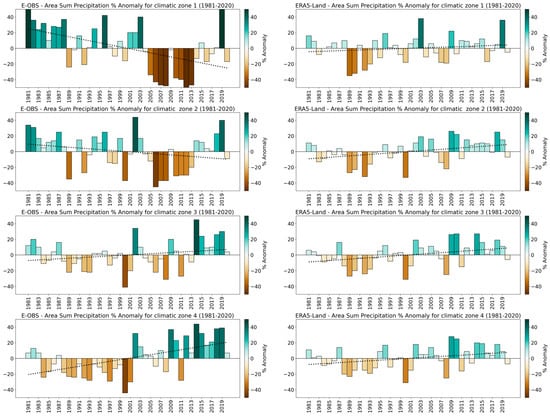

3.5. Precipitation Anomaly

Precipitation anomaly (%), for each of the ERA5-Land and E-OBS datasets, estimated as the percentage of the difference between the precipitation for a specific time period (year) and the long-term average (1980–2020) precipitation, was calculated. Positive anomalies indicate wetter-than-average years, while negative anomalies show drier-than-average years that could be associated with possible drought periods.

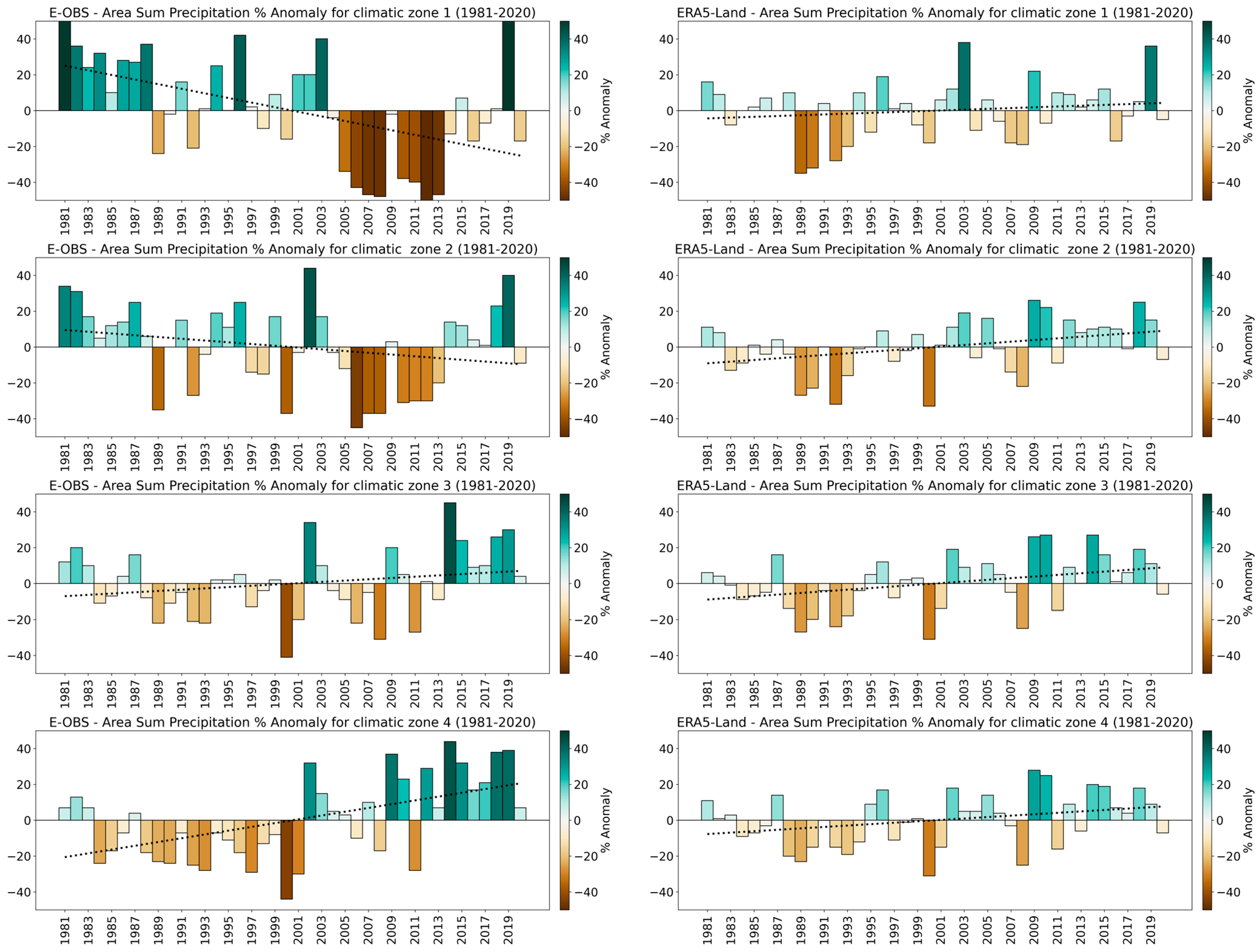

Figure 13 presents the annual precipitation anomaly per climatic zone derived from both datasets used in this study. The grid cells of each dataset were assigned to zones using shapefiles that correspond to the regions already mentioned in Table 2 and shown in Figure 1. Accordingly, a summary of the results for both the precipitation intensity classes and the corresponding number of rainy days for both datasets and for the four climatic zones is presented in Table 3.

Figure 13.

Annual precipitation anomaly (%) per climatic zone, with respect to the average for the period 1981–2020.

Table 3.

Trends of precipitation intensity and corresponding number of rainy days for each of the four climatic zones.

The analysis reveals the differences between each climate zone and again between the two datasets, displaying spatial- and dataset-dependent variations. E-OBS shows a notable difference between the climatic zones that changes gradually, showing a south–north gradient, with negative anomalies for the southern ones (climate zones 1 and 2) and positive for the northern ones (climate zones 3 and 4). On the other hand, the ERA5-Land dataset presents a uniform trend for all zones, almost identical for zones 2, 3 and 4. Comparing with E-OBS, the two datasets agree reasonably well in climate zone 3, and partially in zone 4, where there is a positive trend for both series with some differences, while zone 1 and 2 have discrepancies since they are positive for ERA5-Land and clearly negative for E-OBS.

From Table 3, it is evident that variations in trends are attributed to the two datasets. An agreement is clearly demonstrated for climatic zone 4, where both datasets show a positive trend for each case, with NRD during low precipitation intensity as the only exception. The same picture is observed also for climatic zone 3, where exceptions are reported for the cases with low precipitation intensity (both for amount of rain and NRD) and NRD for total annual precipitation. Regarding climatic zone 2, it is evident that there is an agreement for moderate and intense precipitation intensity and corresponding NRD. Finally, both datasets present a disagreement for all cases of P and NRD, with ERA5-Land data showing a positive trend, while E-OBS a negative one.

4. Discussion

Precipitation trends in the Mediterranean are characterized by high spatial and temporal variability, leading to a simultaneous decrease in total annual rainfall alongside an increase in the intensity of extreme precipitation events [42,43]. While the region is widely recognized as a climate change hotspot, long-term trends remain complex and are heavily influenced by natural variability [42].

The Mediterranean is generally experiencing pronounced aridification [42]. Since the mid-20th century, many sub-regions have shown a significant decrease in total annual precipitation amounts [8,43]. Significant drying trends have been observed in Northwest Africa and the southern Iberian Peninsula, with total annual rainfall declines reaching up to 60 mm per decade in specific areas [8,44]. Greece has exhibited significant declining inter-annual trends, particularly in winter precipitation, since the 1950s. However, recent decades (2000–2020) have shown a slight increase in rainfall compared to the low levels of the 1990s, though still below the peaks of the 1960s [27].

A defining feature of current trends is the shift in the nature of rainfall. While the total volume of water is often decreasing, the frequency of extreme events is rising in several areas, particularly along the northern Mediterranean coast [43]. Maximum one-day precipitation has increased in localized regions by up to 3 mm per decade [8].

The primary driver of drying in the Mediterranean is not necessarily a decrease in the intensity of rain when it happens, but a significant increase in the frequency of dry days [42]. In short, it rains less often, but when it does, it tends to be more severe [23,43,45,46].

Moreover, precipitation changes are not uniform across the basin, revealing distinct geographical splits: a west–east dipole and a north–south gradient. For the first one, a clear contrast exists between the Western Mediterranean (decreasing trends) and the Northeastern Mediterranean (increasing trends) [8]. For instance, heavy precipitation days have decreased in the West while increasing in parts of the Balkans and Turkey [8]. For the second one, Northern Europe is generally becoming wetter, while the Mediterranean experiences light rain decreases but extremes intensify [42].

Our findings are in good agreement with recent studies focusing on the same region. In a recent study, Cavalleri et al. [47] report that ERA5-Land generally improves spatial coherence and temporal correlation compared to ERA5, but exhibit region-dependent biases, particularly in areas of complex topography. Differences from E-OBS are most pronounced in daily precipitation extremes, where E-OBS tends to underestimate peak intensities while ERA5-Land may smooth or overestimate them. Additionally, Papa and Koutroulis [26], comparing ERA5-Land and ERA5 with E-OBS and dense gauge-based observational records, across Greece, indicate that E-OBS often underestimates high-intensity rainfall events, whereas ERA5-Land can overestimate precipitation totals in some regions, leading to different characterizations of extremes and wet-day frequency.

5. Conclusions

A 40-year study of precipitation using the ERA5-Land and E-OBS gridded databases over Greece was presented emphasizing on the climatic zones of Greece. The study presented an analysis of precipitation trends considering both precipitation intensity and the number of rainy days. Regarding precipitation intensity, precipitation calculations for total annual precipitation (P > 1 mm), as well as low (1 mm < P < 10 mm), moderate (10 mm < P < 20 mm), and extreme (P > 20 mm) precipitation were considered, accounting accordingly the corresponding number of rainy days for each case. Moreover, precipitation anomaly was also calculated.

The main findings of our study are summarized below:

- Regarding total precipitation E-OBS and ERA5-Land data showed a negative trend with distinctive differences in the geographical areas of central and southern parts of Greece. However, a controversary trend was established in the north-western region of Greece. The trend in the number of rainy days (NRD) of E-OBS data presented a significant reduction, particularly evident in Central and Southern Greece, while ERA5-Land data indicated a slight increase in NRD across nearly the whole country.

- Differences in precipitation of low intensity between the two datasets are still evident. Overall, E-OBS presented a clear decline in Crete, while ERA5-Land presented an increase in almost the whole country. Regarding the corresponding number of rainy days, the distinction between the two datasets is still prominent. ERA5-Land data presented a slight increase in NRD, while E-OBS revealed an overall reduction, with only a few exceptions.

- The variance of precipitation trend of E-OBS and ERA5-Land data in the case of moderate precipitation intensity is noticed. ERA5-Land presented positive values across most of the country, while E-OBS only in areas of northern Greece. However, negative values for E-OBS are noticed in areas of Southern Greece and Crete. On the other hand, this variation in differences is less pronounced as compared to the number of rainy days. E-OBS reveals a slight increase in areas of Northern Greece, no trend or negative for southern Greece, and an undoubtedly negative trend over Crete. In contrast, ERA5-Land data showed a slight increase in almost the entire country.

- Differences between the two datasets in terms of extreme precipitation intensity could be considered as rather localized. E-OBS demonstrated higher positive trend over limited areas in northern Greece; an extensive part of the country revealed no clear trend, while some areas, like Crete, displayed negative trends. In contrast, ERA5-Land demonstrated a positive trend across most parts of the country, while areas of Southern Greece and Crete showed near zero or slightly negative trends. With respect to the number of rainy days, differences are less pronounced. E-OBS demonstrated increase in areas of Northern Greece, little to no trend, or even negative across southern Greece and Crete. On the other hand, the ERA5-Land data depicted a modest overall increase, while no clear trend was noticed in Southern Greece and Crete.

- Spatial- and dataset-dependent variations were revealed each of the climate zones. E-OBS and ERA5-Land data presented an overall good agreement in the climatic zones 3 and 4, depicting positive trends. On the other hand, significant differences are noticed especially in the climatic zone 1 and less in climatic zone 2, where ERA5-Land presented positive trends and E-OBS presented negative ones.

In overall, E-OBS and ERA5-Land precipitation estimations presented significant differences in some cases that could attributed to the nature of sources of each dataset. Although ERA5-Land is a well-established product used in several research studies, having the ability to detect the geographical patterns well, caution, due to precipitation overestimation, is necessary in areas of complex topography. On the other hand, the E-OBS dataset needs to be enhanced with more in situ rainy stations so as to better “capture” precipitation patterns, especially in areas of complex topography.

E-OBS provides high-resolution coverage of Greece, with daily data for temperature, precipitation, and sea level pressure, but its reliance on sparse stations limits accuracy in southern Greece, islands, and mountains. ERA5-Land offers global coverage ensuring consistency across all regions, particularly data-sparse islands and mountains. E-OBS is preferable in northern Greece for climatological studies, while ERA5-Land excels in southern Greece, islands, and for broader applications like hydrological or energy studies.

Results could assist policy makers to consider mitigation actions for preventing climate change impacts on a regional level. The authors aim to continue their research by exploiting recent precipitation data and the role of some extraordinary extreme events, such as the Medicane Daniel, examining whether such events have any impact on long-term precipitation trends.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.R. and D.K.; data curation, D.K., A.R., I.L. and C.G.; writing—original draft preparation, A.R., D.K., I.L. and C.G.; writing—review and editing, A.R., D.K., I.L. and C.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) for the provision of ERA5-Land data and the Copernicus Climate Change Service for the provision of E-OBS data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Tapiador, F.J.; Turk, F.J.; Petersen, W.; Hou, A.Y.; García-Ortega, E.; Machado, L.A.T.; Angelis, C.F.; Salio, P.; Kidd, C.; Huffman, G.J.; et al. Global precipitation measurement: Methods, datasets and applications. Atmos. Res. 2012, 104–105, 70–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaelides, S.; Levizzani, V.; Anagnostou, E.; Bauer, P.; Kasparis, T.; Lane, J.E. Precipitation: Measurement, remote sensing, climatology and modeling. Atmos. Res. 2009, 94, 512–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandhauer, M.; Isotta, F.; Lakatos, M.; Lussana, C.; Båserud, L.; Izsák, B.; Szentes, O.; Tveito, O.E.; Frei, C. Evaluation of daily precipitation analyses in E-OBS (v19.0e) and ERA5 by comparison to regional high-resolution datasets in European regions. Int. J. Climatol. 2022, 42, 727–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivoire, P.; Martius, O.; Naveau, P. A comparison of moderate and extreme ERA-5 daily precipitation with two observational data sets. Earth Space Sci. 2021, 8, e2020EA001633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lledó, L.; Haiden, T.; Chevallier, M. An intercomparison of four gridded precipitation products over Europe using an extension of the three-cornered-hat method. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2024, 28, 5149–5162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassler, B.; Lauer, A. Comparison of Reanalysis and observational precipitation datasets including ERA5 and WFDE5. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavers, D.A.; Simmons, A.; Vamborg, F.; Rodwell, M.J. An evaluation of ERA5 precipitation for climate monitoring. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2022, 148, 3124–3137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavaşlı, D.D. Spatio-temporal trends in precipitation indices over Mediterranean using ERA5-Land data (1950–2024). Int. J. Climatol. 2025, 45, e70049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, P.; Messori, G.; Faranda, D.; Ward, P.J.; Coumou, D. Compound warm–dry and cold–wet events over the Mediterranean. Earth Syst. Dyn. 2020, 11, 793–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastrantonas, N.; Herrera-Lormendez, P.; Magnusson, L.; Pappenberger, F.; Matschullat, J. Extreme precipitation events in the Mediterranean: Spatiotemporal characteristics and connection to large-scale atmospheric flow patterns. Int. J. Climatol. 2020, 41, 2710–2728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retalis, A.; Katsanos, D.; Michaelides, S. Precipitation climatology over the Mediterranean Basin—Validation over Cyprus. Atmos. Res. 2016, 169, 449–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakalis, V. Trend analysis and forecast of annual precipitation and temperature series in the Eastern Mediterranean region. Atmósfera 2023, 38, 381–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markonis, Y.; Batelis, S.C.; Dimakos, Y.; Moschou, E.; Koutsoyiannis, D. Temporal and spatial variability of rainfall over Greece. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2017, 130, 217–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philandras, C.M.; Nastos, P.T.; Paliatsos, A.G.; Repapis, C.C. Study of the rain intensity in Athens and Thessaloniki, Greece. Adv. Geosci. 2010, 23, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livada, I.; Charalambous, G.; Assimakopoulos, M.N. Spatial and temporal study of precipitation characteristics over Greece. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2008, 93, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsanos, D.; Lagouvardos, K.; Kotroni, V.; Huffmann, G.J. Statistical evaluation of MPA-RT high-resolution precipitation estimates from satellite platform over the central and eastern Mediterranean. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2004, 31, L06116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feidas, H. Validation of satellite rainfall products over Greece. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2010, 99, 193–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nastos, P.T.; Kapsomenakis, J.; Philandras, K.M. Evaluation of the TRMM 3B43 gridded precipitation estimates over Greece. Atmos. Res. 2016, 169, 497–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazamias, A.P.; Sapountzis, M.; Lagouvardos, K. Evaluation of GPM-IMERG rainfall estimates at multiple temporal and spatial scales over Greece. Atmos. Res. 2022, 269, 106014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsanos, D.; Retalis, A.; Kalogiros, J.; Psiloglou, B.E.; Roukounakis, N.; Anagnostou, M. Performance Evaluation of Satellite Precipitation Products During Extreme Events—The Case of the Medicane Daniel in Thessaly, Greece. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 4216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandridis, V.; Stefanidis, S.; Dafis, S. Evaluation of ERA5 and ERA5-Land Reanalysis Precipitation Data with Rain Gauge Observations in Greece. Environ. Sci. Proc. 2023, 26, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourtis, I.M.; Vangelis, H.; Tigkas, D.; Mamara, A.; Nalbantis, I.; Tsakiris, G.; Tsihrintzis, V.A. Drought Assessment in Greece Using SPI and ERA5 Climate Reanalysis Data. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leščešen, I.; Basarin, B.; Podraščanin, Z.; Mesaroš, M. Changes in Annual and Seasonal Extreme Precipitation over Southeastern Europe. Environ. Sci. Proc. 2023, 26, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nastos, P.; Kapsomenakis, J.; Matsangouras, I.; Poulos, S. Precipitation over Thessaly Plain, Greece. Present and Future Changes. In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Environmental Science and Technology, Rhodes, Greece, 3–5 September 2015; Available online: http://thalis-daphne.geol.uoa.gr/fileadmin/thalis-daphne.geol.uoa.gr/uploads/Papers/Nastos_et_al_CEST2015.pdf (accessed on 7 October 2025).

- Mavromatis, T.; Voulanas, D. Evaluating ERA-Interim, Agri4Cast, and E-OBS gridded products in reproducing spatiotemporal characteristics of precipitation and drought over a data poor region: The case of Greece. Int. J. Climatol. 2021, 41, 2118–2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papa, K.M.; Koutroulis, A.G. Evaluation of precipitation datasets over Greece. Insights from comparing multiple gridded products with observations. Atmos. Res. 2025, 315, 107888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varlas, G.; Stefanidis, K.; Papaioannou, G.; Panagopoulos, Y.; Pytharoulis, I.; Katsafados, P.; Papadopoulos, A.; Dimitriou, E. Unravelling Precipitation Trends in Greece since 1950s Using ERA5 Climate Reanalysis Data. Climate 2022, 10, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagouvardos, K.; Dafis, S.; Kotroni, V.; Kyros, G.; Giannaros, C. Exploring Recent (1991–2020) Trends of Essential Climate Variables in Greece. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, H.E.; McVicar, T.R.; Vergopolan, N.; Berg, A.; Lutsko, N.J.; Dufour, A.; Zeng, Z.; Jiang, X.; van Dijk, A.I.J.M.; Miralles, D.G. High-resolution (1 km) Köppen-Geiger maps for 1901–2099 based on constrained CMIP6 projections. Sci Data 2023, 10, 724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Technical Guide, TOTEE 20701-1. In Analytic National Specifications of the Parameters for the Calculation of the Energy Performance of Buildings and the Issue of the Energy Certificate of Buildings, 1st ed.; Technical Chamber of Greece, (Government Gazette 4003/Β/17.11.2017); National Printing Office: Athens, Greece, 2017. (In Greek)

- Technical Guide, TOTEE 20701-3. In Climatic Data of Greek Areas, 2nd ed.; Technical Chamber of Greece: Athens, Greece, 2012. (In Greek)

- Bololia, M.; Androutsopoulos, A. Achieving nearly zero energy buildings in Greece. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 410, 012035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaglia, A.G.; Tsikaloudaki, A.G.; Laskos, C.M.; Dialynas, E.N.; Argiriou, A.A. The impact of the energy perfor-mance regulations’ updated on the construction technology, economics and energy aspects of new residential buildings: The case of Greece. Energy Build. 2017, 155, 225–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Founda, D.; Giannakopoulos, C. The exceptionally hot summer of 2007 in Athens, Greece—A typical summer in the future climate? Glob. Planet. Change 2009, 67, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagouvardos, K.; Kotroni, V.; Bezes, A.; Koletsis, I.; Kopania, T.; Lykoudis, S.; Mazarakis, N.; Papagiannaki, K.; Vougioukas, S. The automatic weather stations NOANN network of the National Observatory of Athens: Operation and database. Geosci. Data J. 2017, 4, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feidas, H.; Noulopoulou, C.; Makrogiannis, T.; Bora-Senta, E. Trend analysis of precipitation time series in Greece and their relationship with circulation using surface and satellite data: 1955–2001. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2007, 87, 155–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellenic National Meteorological Service (HNMS). Climatic Atlas of Greece. 2025. Available online: http://climatlas.hnms.gr/sdi/?lang=EN (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Muñoz-Sabater, J.; Dutra, E.; Agustí-Panareda, A.; Albergel, C.; Arduini, G.; Balsamo, G.; Boussetta, S.; Choulga, M.; Harrigan, S.; Hersbach, H.; et al. ERA5-Land: A state-of-the-art global reanalysis dataset for land applications. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2021, 13, 4349–4383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomis- Cebolla, J.; Khorchani, M.; Delrieu, G.; Braud, I. Are ERA5 and ERA5-Land Precipitation Data Reliable for Simulating Mediterranean Extreme Flash-Flood Events? Atmos. Res. 2023, 286, 106606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornes, R.C.; van der Schrier, G.; van der Besselaar, E.J.M.; Jones, P.D. An Ensemble Version of the E-OBS Temperature and Precipitation Datasets. J. Geophys. Res. 2018, 123, 9391–9409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulzweida, U. CDO User Guide (2.3.0); Zenodo: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- André, J.; D’Andrea, F.; Drobinski, P.; Muller, C. Regimes of precipitation change over Europe and the Mediterranean. J. Geophys. Res. 2024, 129, e2023JD040413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senatore, A.; Furnari, L.; Nikravesh, G.; Castagna, J.; Mendicino, G. Increasing Daily Extreme and Declining Annual Precipitation in Southern Europe: A Modeling Study on the Effects of Mediterranean Warming. EGUsphere, 2025; preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, D.A.; Olmo, M.E.; Cos, P.; Muñoz, Á.G.; Doblas-Reyes, F.J. Regional aspects of observed temperature and precipitation trends in the western Mediterranean: Insights from a timescale decomposition analysis. J. Geophys. Res. 2025, 130, e2024JD042637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jézéquel, A.; Faranda, D.; Drobinski, P.; Lionello, P. Extreme Event Attribution in the Mediterranean. Int. J. Climatol. 2025, 45, E8799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zittis, G.; Bruggeman, A.; Lelieveld, J. Revisiting future extreme precipitation trends in the Mediterranean. Weather Clim. Extrem. 2021, 34, 100380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavalleri, F.; Lussana, C.; Viterbo, F.; Brunetti, M.; Bonanno, R.; Manara, V.; Lacavalla, M.; Sperati, S.; Raffa, M.; Capecchi, V.; et al. Multi-scale assessment of high-resolution reanalysis precipitation fields over Italy. Atmos. Res. 2024, 312, 107734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.