Abstract

Heat waves have emerged as an escalating climate threat, triggering cascading disruptions across food, energy, and water systems, thereby undermining resilience and sustainability. However, reviews addressing heat wave impacts on the food–energy–water (FEW) nexus remain scarce, resulting in a fragmented understanding of cross-system interactions and limiting the ability to assess cascading risks under extreme heat. This critical issue is examined through bibliometric analysis, scoping review, and policy analysis. A total of 103 publications from 2015 to 2024 were retrieved from Web of Science and Scopus, and 63 policy documents from the United States, the European Union, Japan, China, and India were collected for policy analysis. Bibliometric analysis was conducted to identify the most influential articles, journals, countries, and research themes in this field. The scoping review indicates that agricultural losses are most frequently reported (32), followed by multiple impacts (19) and cross-sectoral disruptions (18). The use of spatial datasets and high-frequency temporal data remains limited, and community-scale studies and cross-regional comparisons are uncommon. Mechanism synthesis reveals key pathways, including direct system-specific stress on food production, water availability, and energy supply; indirect pressures arising from rising demand and constrained supply across interconnected systems; cascading disruptions mediated by infrastructure and system dependencies; and maladaptation risks associated with uncoordinated sectoral responses. Policy analysis reveals that most countries adopt sector-based adaptation approaches with limited across-system integration, and insufficient data and monitoring infrastructures. Overall, this study proposes an integrated analytical framework for understanding heat wave impacts on the FEW nexus, identifies critical research and governance gaps, and provides conceptual and practical guidance for advancing future research and strengthening coordinated adaptation across food, energy, and water sectors.

1. Introduction

Climate change has been altering global temperature patterns, with extreme heat events emerging as one of the most serious environmental challenges. Heat waves, which are defined as prolonged periods of excessively high temperatures lasting several days beyond statistical thresholds, are increasing in frequency, intensity, and duration globally [1,2]. These extreme heat events amplify existing stresses on food, energy, and water systems. According to statistical data, heat waves have reduced grain production in Europe by an average of 7.3% [3]; the 2022 heat wave caused India’s national wheat output to decline by 4.5%, with economic losses reaching as high as 15% in specific regions [4,5]; China and the United States are projected to face GDP losses of 2.7% ± 0.7% and 1.8% ± 0.5% by 2060 due to supply-chain disruptions induced by heat waves [6]. These facts indicate that heat waves are not confined to a single sector but instead impose simultaneous pressures on multiple systems.

FEW nexus framings emerged in the late 2000s to shift natural resource management from case-specific approaches to broader, cross-sectoral approaches in decision-making [7]. It emphasizes that water, energy, and food resources are interlinked [8], so interventions in one system inevitably affect the others through production, consumption, or ecological processes. As an interdisciplinary framework, the FEW nexus has been widely applied to resource management, urban sustainability, and climate adaptation, yielding multiple approaches such as life cycle assessment [9], emergy analysis [10], system dynamics modeling [11], multi-objective optimization modeling [12], and cross-sectoral policy analysis [13]. For instance, system dynamics modeling has been used to simulate changes in the FEW demand and supply in the megacity of Beijing [11]. However, studies focusing on the FEW nexus under extreme heat remain limited.

The intersection of heat wave impacts and the FEW nexus represents an emerging and rapidly developing research domain. Heat waves affect food, energy, and water systems through direct stress on biological and infrastructural components, as well as indirect pressures arising from increased cooling and irrigation demand and reduced system efficiency, thereby intensifying cross-sectoral disruptions [14,15,16]. Existing studies have examined heat wave impacts on individual sectors, such as increased cooling energy demand during heat waves or agricultural productivity losses under extreme temperatures [17,18]. In recent years, research has begun to explore heat wave impacts across systems. Hatfield (2015) discussed how heat stress affects not only crop yields but also irrigation water demand as well as energy requirements for cooling and processing facilities [19]. Evidence indicates that during heat waves, Israel’s desalination plant suspended operations in response to energy policies, resulting in increased freshwater scarcity and intensifying the conflict between energy systems and water resources [20]. Despite existing reviews examining climate change and FEW systems, emphasis on heat waves remains notably inadequate. These studies primarily examine climate change impacts on agriculture [21,22], evaluate methods for assessing climate change impacts on FEW nexus [23], and investigate adaptation strategies for distinct regions and sectors [24,25].

In addition, key research gaps are as follows. First, review research addressing heat wave impacts on the FEW nexus is limited, hindering a comprehensive understanding of the research landscape, thematic evolution, and knowledge gaps in this field. Second, existing studies often approach this issue from a single-case or single-system perspective, lacking analytical frameworks to systematically illustrate cascading impacts and underlying mechanisms. Third, despite countries implementing policies concerning food, energy, and water security, policies in response to address vulnerability of the FEW nexus under extreme heat remain fragmented, lacking cross-sectoral comparative analyses. These constraints impede the development of a data-oriented, nexus-oriented adaptation strategy in the context of heat waves.

To address these research gaps, we develop an integrated analytical framework combining bibliometric analysis, a scoping review, and policy analysis to synthesize evidence on heat wave impacts on FEW nexus and related policy responses. Due to the exploratory nature of the research questions, the diversity of study designs, and the absence of standardized outcome measures across studies, a scoping review is more appropriate than other review approaches. Accordingly, this study addresses three research questions. First, what are the publication trends, thematic hotspots, influential articles, journals, and countries in the field of heat wave impacts on the food–energy–water nexus? Second, what are the specific impacts and underlying mechanisms of heat waves on food, energy, and water systems? Third, how do policies respond to the vulnerabilities of the FEW nexus under extreme heat?

The contributions of this study are threefold. First, through bibliometric analysis, it clarifies boundaries, critical themes, and research trends of existing studies, through which it provides a coherent cognitive framework for the rapidly expanding domain. Second, this study proposes a multi-level impact mechanism framework that offers a theoretical foundation for understanding complex impacts of extreme heat on interconnected resource systems. Finally, through cross-country policy analysis, it identifies governance gaps and offers practical implications for strengthening cross-sectoral resilience in risk governance.

2. Methodology

This study employed a mixed-methods approach integrating bibliometric analysis, scoping review, and policy analysis. Bibliometric analysis was applied to examine overall research outputs, the evolution of key themes, and the structure of knowledge networks. The scoping review was conducted to assess impacts and mechanisms of heat waves on food, energy, and water systems. Policy analysis was used to assess representative nations’ policies on heat wave response. A review protocol was developed in advance and registered on the Open Science Framework (OSF; https://osf.io; registered on 23 December 2025). The registration includes the review objectives, eligibility criteria, search strategy, screening procedures, data extraction, and synthesis methods.

2.1. Study Selection Process

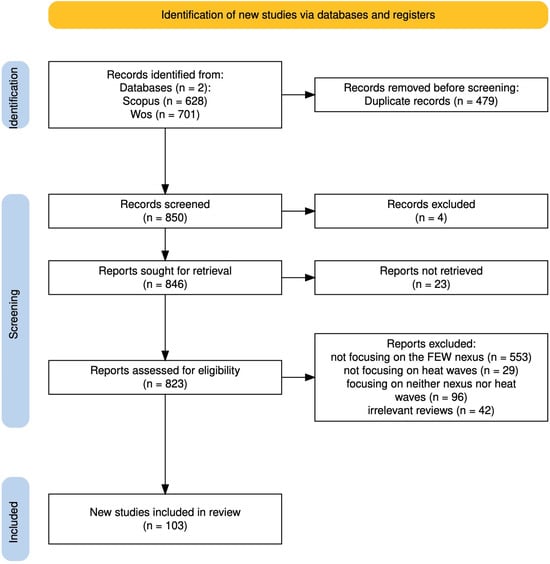

The article selection process adhered to the PRISMA-ScR (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews) guidelines [26]. PRISMA-ScR is widely accepted as a standard reporting guideline for implementing scoping reviews across multiple domains, including health and climate change studies [27,28]. It includes flow diagrams that represent the process of study selection, showing how many records were included or excluded at each stage of the review, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram for the scoping review.

In the first stage, Web of Science (WOS) and Scopus databases were used to define the search terms for retrieving relevant studies. WOS and Scopus are widely utilized and credible databases for the bibliometric and scoping review. They adhere to strict inclusion criteria, provide stable and structured metadata, feature mature citation systems, and offer extensive coverage across interdisciplinary fields [29], thereby supporting cross-system FEW research. By contrast, although open databases such as Google Scholar and OpenAlex offer broader coverage, their indexing mechanisms lack transparency and their metadata quality is inconsistent [29]. Additionally, Google Scholar does not support exporting large datasets, which limits its applicability for large-scale bibliometric analysis [29,30].

The search used the following string: (“heatwave *” OR “heat wave *”) AND ((food AND water) OR (food AND energy) OR (water AND energy)) to retrieve records within title, abstract, and keywords. Only English-language articles and reviews were included to ensure comprehensive coverage of core field contributions. The search timeframe was restricted to publications between 2015 and 2024 for the following reasons. Although the nexus concept began to attract attention around 2011, it remained at a conceptual and case-study stage until FAO formally defined the water–energy–food (WEF) nexus in 2014 [31]. Despite ‘FEW’ and ‘WEF’ both being widely used, this study adopts the food–energy–water (FEW) formulation to emphasize the central role of food systems in mediating heat wave impacts and cascading risks across systems. Subsequent global policy milestones in 2015 catalyzed research on climate risks and cross-system interactions, with many influential studies published thereafter. In addition, to minimize the risk of missing relevant studies due to the constrained nature of the primary search string, we conducted supplementary sensitivity searches that kept “heat wave” as a mandatory keyword and paired it with additional terms commonly used in this domain, including “irrigation”, “power demand”, “power load”, and “water scarcity”. These supplementary searches retrieved only a very small number of additional records and did not materially change the final dataset, confirming that the primary search provided adequate coverage.

The initial database searches yielded 628 records from Scopus and 701 records from WOS, resulting in a total of 1329 raw entries. Complete bibliographic records, including full records and cited references, were exported to form the foundational dataset for deduplication and subsequent analysis [32]. After removing 479 duplicate entries, 850 unique records remained for the initial screening stage.

An exclusion process was applied in the screening. Four records were first removed due to mismatched document types (book chapters), followed by the exclusion of 23 records for which full texts were unavailable. The remaining 823 articles were assessed for eligibility. This step involved a manual review in which our research team meticulously screened titles and abstracts, followed by full-text reviews, to determine relevance to heat wave impacts on the FEW nexus. We applied the following exclusion criteria: (1) not focusing on the FEW nexus; (2) not focusing on heat waves; (3) focusing on neither nexus nor heat waves; and (4) irrelevant reviews. Articles were included if they met all inclusion criteria: (1) they examined at least one component of the FEW nexus (food, energy, or water) under extreme heat conditions; and, (2) they provided empirical evidence, modeling analysis, or conceptual discussion relevant to heatwave-induced impacts. Following Schroeder’s guidance [33], these articles were coded based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. A code of 1 indicated full compliance with the criteria, while a score of 0 indicated non-compliance. This process finally yielded a selection of 103 publications. The screening was conducted by five reviewers. Each record was independently assessed by two reviewers. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion within the research team until consensus was reached.

Data were charted from included studies using a structured extraction form developed in advance and aligned with the research questions. The extraction form was piloted on a subset of studies to ensure clarity and consistency before full implementation. Data extraction was carried out by four reviewers. To ensure reliability, approximately 30–50% of the extracted records were randomly selected for independent cross-checking by a second extractor. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion.

The following data items were extracted from each included study: publication information (title and year), research scale (e.g., city, region, nation, and global), methodological approach and data type, temporal scale, FEW nexus components examined, types of heat wave impacts, and underlying mechanisms linking heat wave impacts on food, energy, and water systems. These variables were selected to support the mapping of research characteristics, and cross-system interactions. Charted data were synthesized using a narrative and descriptive approach. Studies were grouped and compared according to FEW types, impact types, mechanisms, spatial and temporal scales, and methodological characteristics. Results were presented through tables, figures, and conceptual frameworks to highlight key patterns, research gaps, and pathways.

2.2. Bibliometric Analysis

Bibliometric data visualization was conducted using Biblioshiny (the interface of the bibliometrix R package) [34], implemented in R (version 4.4.3). Bibliometric analysis provides descriptive analysis, including publication trends, leading articles, geographic distribution, keyword co-occurrence, and thematic maps, all of which are crucial for answering relevant research questions. Given that dataset was sourced from two different databases, standardization of data format was necessary. Data conversion function of CiteSpace (version 6.3.1) was used to convert Scopus CSV file to WOS plain text format, which was merged with the existing WOS dataset.

2.3. Policy Analysis

We conducted a structured search of national and regional policy documents through government portals, legal databases, and climate-policy repositories. This search utilized keyword combinations such as “heat wave,” “extreme heat,” “drought,” “water resources,” “energy supply,” “food or agriculture security,” and “climate adaptation.” The initial search yielded 106 documents across five regions. To operationalize authority, we restricted inclusion to documents issued by national or regional governmental bodies with formal regulatory or strategic responsibilities. To operationalize relevance, we included only policies that (1) explicitly referenced heat waves and addressed or extreme heat, (2) addressed at least two sectors related to food, energy, and water, and (3) provided actionable measures, regulatory or provisions. Screening was performed in two stages: title–abstract screening followed by full-text assessment by two independent reviewers, with disagreements resolved through discussion. Documents were excluded if they lacked relevance to FEW, addressed heat waves in isolation, were outdated or duplicated, or did not provide actionable provisions. Following these criteria, a final set of 63 policy documents met all inclusion requirements and were retained for detailed coding and comparative analysis. This set included 11 documents from China, 20 from the United States, 12 from Japan, 14 from the European Union, and 6 from India.

3. Results

3.1. Results of Bibliometric Analysis

3.1.1. Publication Trends

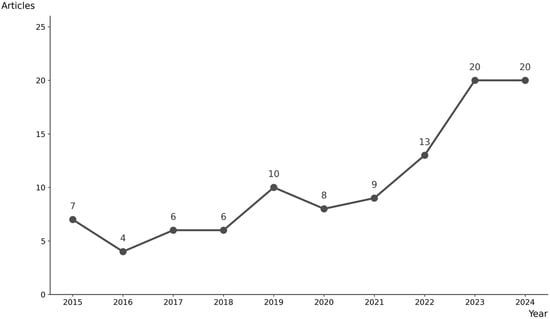

Figure 2 shows the annual production of scholarly publications addressing heat wave impacts within the FEW nexus from 2015 to 2024. Between 2015 and 2019, the number of articles remained modest, ranging from four to ten, without significant momentum. A turning point appears around 2020, when publication output began to rise drastically, and reached 20 by 2023. This upward trend could reflect a broader shift in climate discourse. For example, 2019 European heat waves, among other extreme events, could indicate the increasing risks of heat-related disruptions. Meanwhile, international assessments, such as the IPCC’s Sixth Assessment Report, might also stimulate cross-sectoral attention by highlighting cascading vulnerabilities in FEW systems.

Figure 2.

Publication trends of heat wave impacts on the FEW nexus.

3.1.2. Leading Articles

Table 1 presents the ten most globally cited articles on heat wave impacts within the FEW nexus. The article, authored by Miralles et al., published in Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, ranks first with 568 citations and the highest annual citation rate (81.14), reflecting its strong influence on understanding land–atmosphere feedbacks during droughts and heat waves [35]. Mora et al. (2018) follows with 444 citations, highlighting the cumulative climate hazards intensified by greenhouse gas emissions [36]. Other highly cited papers address diverse themes such as urban heat island effects, crop yield responses under heat stress, and agricultural adaptation strategies [37,38,39,40]. The range of topics underscores the multidisciplinary nature of the FEW nexus research and the central role of heat wave studies in advancing both climate impact assessment and adaptation planning.

Table 1.

Top 10 most global cited articles of heat wave impacts on food, energy, or water systems.

3.1.3. Leading Journals

Table 2 presents the top five most globally cited journals in the field of heat wave impacts within the FEW nexus. Environmental Research Letters leads with the highest h-index (7), g-index (10), and total citations (541) across 10 publications since 2015. This journal’s high g-index of 10 emphasizes its influence in publishing highly cited papers in the realm of environmental and energy systems research, especially related to climate extremes.

Table 2.

Top five most globally cited journals in the field.

Moreover, the second place is tied by Frontiers in Environmental Science and Frontiers in Plant Science with an h-index and g-index of 3. Although Frontiers in Environmental Science has only 13 total citations and started recently, in 2023, its m-index of 1.000 indicates its rapid early citation growth, and might indicate its potential for future impact in the field. Frontiers in Plant Science has been active since 2015 and has accumulated 234 citations over 3 publications, contributing significantly to the understanding of plant responses to heat waves and their connection to water and food security.

For Applied Energy, it follows with an h-index of 2 and total citations of 106. This journal focuses on energy supply and the impacts of heat waves on power plants and energy demand, which makes it central to understanding energy-related vulnerabilities in the FEW nexus, while Atmosphere is also highly relevant, with 179 citations across 2 publications since 2017. This journal plays an important role in understanding atmospheric dynamics during heat waves, including air quality impacts and temperature variations.

3.1.4. Influential Countries

As illustrated in Table 3, the top ten most productive countries contribute to the research field of heat wave impacts within the nexus. The United States stands out as the most prolific contributor to the literature on heat wave impacts within the FEW nexus, producing 20 articles and amassing over 1000 citations. While Germany and China follow in publication volume, countries like Turkey, Italy, and the UK demonstrate remarkable research influence through high average citation rates—exceeding 60 citations per article. This suggests that, despite fewer outputs, their studies resonate strongly within the academic community. The data reflects a geographically diverse research landscape, with both high-output and high-impact nations shaping the discourse on climate-related nexus challenges.

Table 3.

Top 10 most productive countries in the field.

3.1.5. Keywords Analysis

Table 4 presents the co-occurrence network analysis of author’s keywords, which is organized into four distinct thematic clusters. This analysis utilizes three core indicators of network centrality namely Betweenness, Closeness, and PageRank to evaluate how keywords are situated and function within the academic discourse. Betweenness represents the importance of a node as a “bridge” to access other nodes in the network. Closeness reflects how swiftly a keyword could access all other nodes in the network, indicating its integrative potential. Meanwhile, PageRank could evaluate the relative prominence of a keyword based on quantity and quality of its connections within the broader scholarly structure.

Table 4.

Co-occurrence network of the author’s keywords.

Cluster 1 focuses on the core concepts of heat waves and food systems, encompassing by keywords such as heat waves, wheat, elevated CO2, and flash drought. Heat waves show a Betweenness of 21.3, which indicates their bridging role in the network. In addition, Wheat exhibits high connectivity with a Betweenness of 15, reflecting growing attention to crop vulnerability under compound climate stressors.

Cluster 2 is dominated by water stress, highlighting its standalone importance in the nexus. While it has low centrality values, its consistent appearance signifies its relevance, especially under prolonged drought conditions.

In Cluster 3, terms like drought, thermal, pollution, and heat appear. The keyword “drought” shows a relatively high Betweenness score of 29, which reveals its pivotal function in linking diverse climate stress discussions.

Lastly, Cluster 4 contains keywords such as climate change, food security, adaptation, agriculture, and resilience, capturing the broader systemic context. Specifically, climate change holds the highest centrality across all metrics with a Betweenness of 94.7 and PageRank of 0.246, reflecting its universal and significant influence across subtopics. Moreover, adaptation and agriculture also score relatively high in PageRank, showing their policy and research significance.

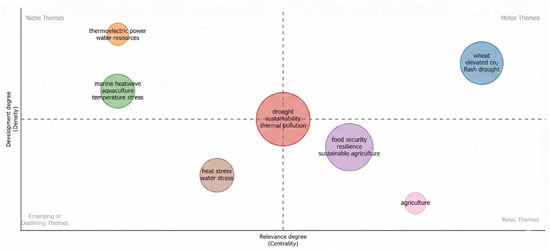

3.1.6. Thematic Map Analysis

Figure 3 presents the thematic map in the field of heat wave impacts on the FEW nexus. The map positions themes along two foundational bibliometric dimensions: centrality, represented on the x-axis as relevance degree, which indicates a theme’s external connectivity and importance to the broader network; and density, represented on the y-axis as development degree, which reflects the theme’s internal cohesion and maturity. The analysis employs the median values of these metrics to segment the map into four strategic quadrants: Motor Themes, Basic Themes, Niche Themes, and Emerging or Declining Themes. Each distinct colored cluster visualized on the map corresponds to a unique thematic grouping identified by the algorithmic analysis, with its strategic meaning derived from its quadrant placement.

Figure 3.

Thematic map of author’s keywords.

In the Motor Themes in the upper right quadrant with keywords such as “wheat,” “elevated CO2,” and “flash drought” show a research hotspot focusing on climate-induced agronomic stress. Their high centrality reflects an evolving interest in how rapid-onset droughts and shifting CO2 levels affect staple crop productivity. Some studies highlight CO2 fertilization effects, while others point to nutrient dilution and stress sensitivity. Their strong centrality reflects a growing, interdisciplinary interest in how rapid-onset droughts and shifting atmospheric compositions affect staple crop productivity, bridging plant physiology, climate science, and adaptive agronomy. However, this cluster could be enriched through greater integration with socio-economic dimensions, such as farmer decision-making or market resilience, to enhance its explanatory power and practical relevance.

Basic Themes, located in the lower-right quadrant, is defined by high centrality but lower density, and includes keywords such as “food security,” “resilience,” and “sustainable agriculture”. These terms represent foundational, cross-cutting concepts that are frequently adopted across disciplines, yet their conceptual fluidity—where resilience may imply ecological robustness or community adaptability—is reflected in their moderate internal cohesion. The relative isolation of the keyword “agriculture” within this space suggests a potential gap, indicating that traditional agricultural studies may not yet be fully aligned with broader sustainability or nexus discourses. This disconnection highlights an opportunity for stronger cross-disciplinary linkage, integrating agriculture more explicitly into frameworks that consider climate governance, equity, and long-term systemic adaptation.

The upper-left quadrant, representing Niche Themes, is characterized by high density but lower centrality. This signifies specialized, well-developed research areas with strong internal literature yet more limited interaction with other domains. A prominent cluster in this quadrant, visually distinct in its assigned color, centers on the nexus of “marine heatwave,” “aquaculture,” and “temperature stress.” This configuration indicates a growing interest of work related to marine systems and food production, particularly under frequent extreme heat scenarios. Although less central, these themes are gaining traction, possibly driven by rising concerns about the blue economy and marine ecosystem services.

For Emerging or Declining Themes, “heat stress” and “water stress” are in the lower-left quadrant. They are either emerging concerns or losing prominence as standalone topics. Their positioning may indicate a conceptual transition that while early studies have probably focused on these stressors in isolation, recent research increasingly frames them within compound risk or systematic approaches. Their potential to regain centrality hinges on more explicit integration into overarching resilience or nexus-based analyses.

Positioned near the intersection of the quadrants, the cluster containing “drought,” “sustainability,” and “thermal pollution” occupies a strategically pivotal yet conceptually evolving space. Its central location underscores the foundational role of drought in climate risk research and the unifying function of sustainability across sectors. The inclusion of thermal pollution—often an externality linked to power generation and aquatic ecosystem degradation—highlights an underexplored dimension that warrants greater attention within nexus governance studies. Collectively, the map reveals a research landscape anchored by a core concern for climate–agriculture interactions (Motor Themes), supported by broad but diffuse sustainability concepts (Basic Themes), and complemented by specialized technical and marine foci (Niche Themes). The analysis underscores a strategic imperative to foster stronger conceptual and empirical linkages between these diverse yet interconnected thematic clusters.

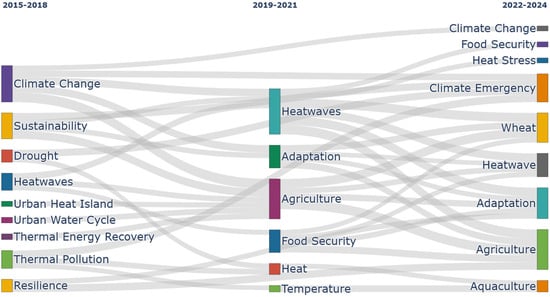

Figure 4 visualizes thematic evolution using a Sankey representation across three time slices (2015–2018, 2019–2021, and 2022–2024). Each block denotes a theme (a keyword cluster identified via co-word analysis within each time slice), and the block size reflects the relative volume of publications associated with that theme in the corresponding period. Flows connect themes in adjacent time slices when they share keywords; flow thickness represents the strength of this conceptual linkage (i.e., the extent of keyword overlap between the two themes).

Figure 4.

Thematic evolution of author’s keywords.

The period of 2015–2018 was primarily focused on broad and systems level issues like Climate Change, Sustainability, Urban Heat Islands, Thermal Pollution, and Resilience. This stage reflects a time when researchers focused on overall environmental conditions and the underlying causes of heat-related risks, rather than on their concrete impacts. The thematic arrangement in 2019–2021 is more narrowed on practical extremes of climate and human–environment relationships. The links between previous and subsequent themes (e.g., climate change—heat waves; sustainability—adaptation; drought—agriculture) reveal how the original conceptual concepts contributed to the applied research on the assessment of vulnerability and sector-specific adaptation demands. By 2022–2024, the literature had matured and spread into more specialized and differentiated themes against Climate Emergency, Heat Stress, and Wheat, although Adaptation and Agriculture persisted, signaling that they will be relevant as the field becomes risk management and resilience planning. The emergence of Aquaculture is also an indicator of diversification of elements of the FEW nexus that are not heavily exploited due to the increase in temperature. In general, the transformation of broad climatic concerns to sustainability-oriented investigation, and then to event-specific heat wave studies and finally to sector-specific specializations, can be viewed as the response of the literature to the increasing number of climate events, policy urgency, and the necessity of special adaptation measures.

3.2. Results of Scoping Review

3.2.1. Dimension, Scale, and Methods

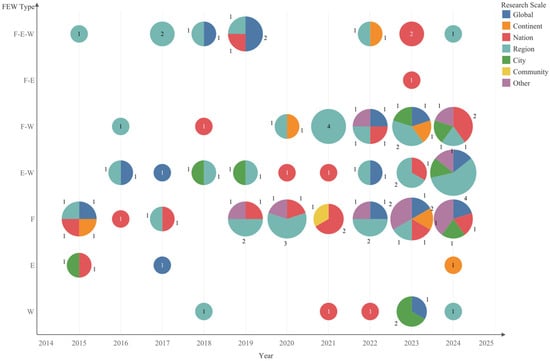

Among the identified 103 studies over the last decade, about half focus on heat wave impacts on a single system (n = 45), with the food system representing the largest category (n = 34) (Figure 5). The second most commonly studied configurations are the food–water (F–W) nexus (n = 22), the energy–water (E–W) nexus (n = 21), and the food–energy–water (F–E–W) nexus (n = 14). Regional studies are the most numerous (n = 39), followed by national (n = 23) and city (n = 15) scales. Global-scale studies (n = 15) are more concentrated within multi-system nexus types, such as the “E–W” type. On the contrary, community-based (n = 9) and continental (n = 6) studies were relatively limited, which could mean that localization and cross-continental comparisons were not the themes.

Figure 5.

The trend of studies on heat wave impacts on food, energy, and water systems (n = 103) over the past 10 years. Note: The numbers beside each circle represent the number of articles for each FEW type and research scale.

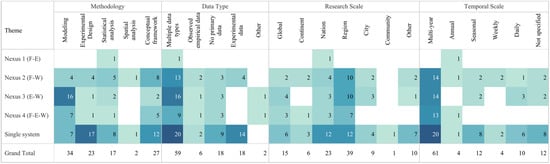

Figure 6 summarizes the scales and methods of heat wave impacts on the FEW nexus. In terms of research methods, modeling (n = 34) is the most frequently employed method [45,46], followed by experimental design [47] (n = 23) and statistical analysis [18] (n = 17). Spatial analysis is relatively less common, and conceptual frameworks tend to be mostly found in nexus studies (n = 15). The most methodological variety is observed in single-system studies, which commonly combine modelling, statistical analysis, and conceptual frameworks. Regarding data types, multiple data sources were the most widely used (n = 59), and the trend is the most significant in nexus studies. As an example, the sensitivity of Western U.S. power systems to heat and drought extremes has been modeled and analyzed using observed meteorological data, power plant operational records, secondary infrastructure data, and geospatial hydrological data at varying degrees of renewable energy penetration [48]. The second place is occupied by experimental data (n = 18) and studies as well as those which lack primary data and are predominantly reviews (n = 18). Empirical data is least frequently observed (n = 6) but is also present in nexus studies and single-system studies. Concerning temporal scale, multi-year assessments dominate (n = 61), reflecting the need to capture interannual variations of heat wave impacts [40,49]. Seasonal and annual data are less common (both n = 4), while high-frequency (weekly, daily) analyses are extremely rare, indicating a deficiency in methods for obtaining high-frequency data.

Figure 6.

Methods, data types, and scales of the identified studies over 10 years. Note: The numbers in each cell indicate the number of articles corresponding to the given FEW nexus type (rows) and the specified methodological, data, spatial, or temporal category (columns). The colors represent the number of articles in each category, with darker colors indicating higher values.

Thus, we find that there is substantial research on the impact of heat waves on food, food–water, or energy–water systems, but only a small fraction of studies (14/103) explicitly addresses how heat wave impacts propagate within the food–energy–water nexus. Moreover, the use of spatial data (9/103) and high-frequency temporal datasets (14/103) remains limited, and community-level analyses and cross-continental comparisons are still uncommon.

3.2.2. Heat Wave Impacts on the FEW Nexus

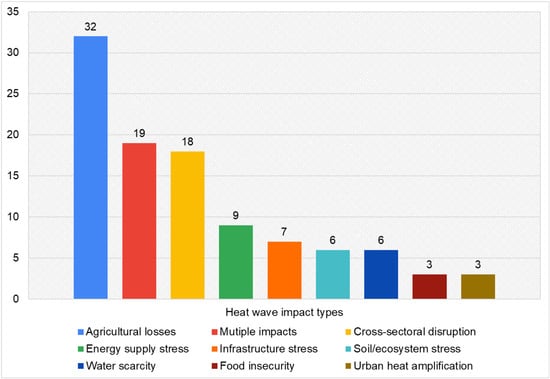

Figure 7 illustrates that heatwave impacts on the FEW nexus are diverse, spanning both single-system impacts and multi-system impacts across food, energy, and water systems. Overall, food-related impacts are most frequently reported, followed by multi-system impacts and cross-sectoral disruptions.

Figure 7.

Diverse heat wave impacts on food, energy, and water systems.

For single systems, the food system is the most frequently examined domain of heat wave impacts. Agricultural losses (32 cases) are primarily reported as crop yield reductions, livestock health deterioration, and disruptions to agricultural supply chains. Studies report that under high-temperature conditions, enhanced evapotranspiration, damage to crop reproductive phases, and increased pest and disease outbreaks are often observed concurrently with significant yield reductions [16,50,51,52]. In livestock systems, heat stress is typically associated with declined productivity and increased mortality [53]. Beyond direct losses, a limited number of studies further report food security implications arising from heatwave-induced agricultural shocks. For instance, the 2010 Russian heatwave and associated drought led to severe wheat yield losses and export restrictions, contributing to food price spikes and heightened food insecurity in import-dependent regions [54].

Energy-related impacts are also commonly reported (9 cases), mainly characterized by the concurrence of increased cooling demand and energy supply stress during heat waves. Existing studies indicate that under high-temperature conditions, water-cooled thermal power plants may face operational constraints due to elevated cooling-water temperatures or reduced water flow [17,55,56]. In contrast, the water system is less frequently examined as the primary impact domain (6 cases). The relevant studies on water scarcity reports increased pressure on water supply systems during heat waves. Empirical evidence shows that extreme heat can significantly increase household water consumption, with cumulative effects observed during prolonged heatwave events, thereby intensifying operational stress on urban water supply systems [57]. It also indicates that these impacts vary across regions, reflecting differences in climatic background and infrastructure conditions.

Existing studies also report heat wave impacts spanning food, energy, and water systems. Multiple impacts (19 cases) and cross-sectoral disruptions (18 cases) are typically reported as the co-occurrence of agricultural losses, energy supply stress, and water scarcity [58,59,60,61,62,63]. For example, studies simultaneously observe crop yield reductions and surging cooling electricity demand during heat waves, placing pressure on water allocation for both irrigation and energy production [58,59,60]. In other cases, power supply constraints are reported together with impaired irrigation operations and deteriorated food storage conditions [18,61]. These observations suggest that heat wave impacts often extend across multiple systems.

Although other impact types are less frequently documented, they are reported as important under specific contexts. Infrastructure stress includes damage to transportation networks critical for food distribution, as well as the degradation of irrigation or water supply systems [64,65]. Soil and ecosystem stress is reflected in soil moisture loss, vegetation degradation, and biodiversity decline, which may adversely affect long-term agricultural productivity and ecosystem service provision [66,67,68].

Moreover, heat wave impacts on FEW systems exhibit regional variations in the literature. For instance, studies from Asia and Europe most frequently document agricultural losses (6 and 4 cases, respectively) and cross-sectoral disruptions (5 and 4 cases, respectively), reflecting their intensive agricultural systems and interconnected infrastructure [16,38,50,69]. Whereas, energy-supply stress appears frequently in North American studies (4 cases), reflecting the region’s reliance on thermal and hydro generation vulnerable to heat-drought extremes [17,48,56,70]. These differences suggest that reported heat wave impacts on multiple systems are shaped by regional climatic conditions, infrastructure configurations, and socio-economic contexts.

Overall, the above analysis primarily reflects the distribution and manifestations of different impact types as documented in the literature, but remains insufficient to explain how these impacts interact across systems and their potential cascading effects. The underlying mechanisms will be further explored in the next section.

3.2.3. Mechanisms of Heat Wave Impacts on the FEW Nexus

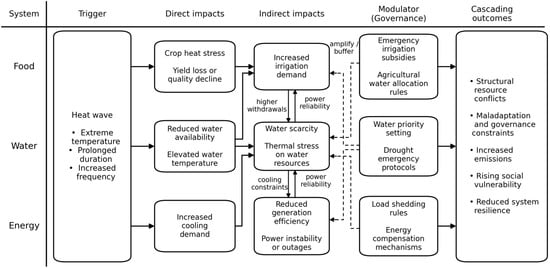

Building on this foundation, this section examines the underlying mechanisms through which heat wave impacts propagate across food, energy, and water systems, and generate cascading effects (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Mechanism of heat wave impacts on food–energy–water nexus. Note: Solid arrows indicate impact propagation pathways, while dashed arrows represent modulation or feedback loops.

Heat waves act as an initial trigger by exerting direct pressure on food, water, and energy systems through prolonged periods of extreme high temperatures. In the food system, heat stress disrupts crop physiological processes, leading to yield reductions or quality deterioration [39,71]. In the water system, heat waves are typically associated with elevated water temperatures and reduced water availability [15,17]. In the energy system, cooling demand increases quickly, thereby raising electricity loads and reducing the operational efficiency of certain power generation facilities [45,72]. At this stage, impacts are primarily confined within individual systems and manifest as direct biophysical or operational stress responses induced by heat waves.

Under this direct pressure, structural interactions within the food–energy–water nexus are activated, generating indirect impacts and enabling the propagation of risks across systems. Heat stress frequently induces rapid increases in irrigation demand as an adaptive response to prevent crop yield losses, increasing both water withdrawal intensity and energy loads [62,73]. At the same time, elevated domestic water demand during heat waves further amplifies operational stress on water systems, causing water scarcity to emerge not only as a supply-side constraint but as a dual pressure arising from both demand and supply dynamics [57]. As water systems become increasingly stressed, constrained cooling conditions may reduce the generation efficiency of thermal and hydropower facilities, thereby undermining energy system stability [17,45]. In turn, energy system instability or outages can disrupt irrigation infrastructure, food storage, and cold-chain logistics, allowing localized disturbances to escalate rapidly into cross-system risks.

Governance and policies play a critical moderating role in these processes and may either amplify or buffer pathways of risk transmission across systems. Policy instruments such as emergency irrigation subsidies, water allocation rules, load-shedding regimes, and energy compensation mechanisms are often designed to maintain the short-term functional stability of specific systems. However, in the absence of cross-sectoral coordination and integrated trade-off frameworks, such measures may reallocate pressures across systems, inadvertently inducing maladaptation by shifting risks rather than alleviating them [20,74,75]. For example, in Israel, desalination has been promoted as a key adaptation strategy to address water scarcity. Yet during heat waves, existing power load reduction and compensation mechanisms can make reductions in desalination output economically preferable, leading to forced declines in freshwater production. This dynamic increases water-system dependence on the energy sector and amplifies overall system vulnerability [20]. A similar form of maladaptation has been documented in Mississippi Delta of the United States. Under extreme heat conditions, increased irrigation is often regarded as a viable response to crop heat stress due to low groundwater extraction costs and the absence of heat-specific regulatory controls, even when soil moisture is not limiting. The study suggests that this strategy fails to mitigate heat-related yield losses while accelerating aquifer depletion and increasing energy, leading to maladaptation driven by misaligned governance incentives and risk mechanisms [75].

When multiple impacts propagate across systems and are further shaped by governance interventions, heat waves can trigger cascading outcomes that extend beyond isolated system disruptions. These outcomes manifest as compound risks, including structural resource conflicts, maladaptation and intensified governance constraints, increased greenhouse gas emissions, heightened social vulnerability, and declining overall system resilience [20,61,76,77]. In the absence of effective buffering mechanisms and cross-system coordination capacities, short-term extreme heat events may escalate into cross-system and cross-sector compound crises.

3.3. Results of Policy Analysis

Scoping review results show that heat waves exert multi-dimensional and cross-system impacts on the FEW nexus. However, existing studies predominantly focus on single systems such as agriculture, energy supply, or water availability, while research on cascading effects among food, energy, and water systems remains limited. These research gaps suggest that scientific evidence is inadequate to inform policy design. Furthermore, they imply that many countries’ policies primarily reflect single-sector responses, lacking a cohesive weighing and coordination mechanism. Therefore, it is essential to investigate whether policy practices adequately address heat wave risks and research gaps identified in the literature. Accordingly, the study further conducts a policy analysis by comparing governance logics, cross-sectoral coordination mechanisms, and specific adaptation instruments across countries to identify potential blind spots and institutional vulnerabilities within existing governance frameworks. This approach provides a more comprehensive perspective for understanding governance gaps and pathways for enhancing resilience in the FEW nexus in the context of heat wave risks.

This study examines five regions: the United States, the European Union, Japan, China, and India. These areas were chosen not only for their significant contributions to the field, but also for their diverse risk profiles and governance models (Table 5). The selection covers both developed and developing countries, various regulatory frameworks, and strategies to mitigate heat wave impacts. Policies collected include laws, strategic plans, targeted action programs, and cross-sectoral coordination mechanisms. The criteria for selection focused on relevance to heat wave adaptation governance in food, energy, and water systems, as well as level of authority. In total, 63 relevant policy documents were identified as follows: 14 from the European Union, 20 from the United States, 12 from Japan, 11 from China, and 6 from India. A structured analysis table of these policy documents is available in the Supplementary Materials.

Table 5.

The main reasons for selecting the five case regions.

3.3.1. European Union

The European Union (EU) addresses heat wave challenges through a multi-level governance framework, in which policies are primarily formulated at the supranational (EU) level and subsequently implemented by individual member states. The Directorate General for Climate Action, Directorate General for Energy, and Directorate General for Environment as the crucial tools for the European Commission to develop policy and coordination. The European Environment Agency (EEA) provides scientific assessment and monitoring. The European Parliament and the Council of the European Union are responsible for passing legally binding legislative documents. The European Climate Law is a core legal tool. It sets the main goal of achieving climate neutrality by 2050 as a legal obligation and requires that climate change adaptation be incorporated into the legal framework [78]. Member states develop National Adaptation Plans (NAPs) that integrate adaptation measures into multi sectoral policies such as agriculture, water, and energy [79]. However, there is no permanent cross-departmental agency at the EU level specifically responsible for coordinating the FEW nexus, which leads to fragmented policy implementation.

Among numerous climate-related laws and strategies, three policies are most representative. Firstly, the European Climate Law establishes a legal framework for achieving climate neutrality by 2050 and requires systematic adaptation actions [78]. This law covers FEW with agricultural adaptability requirements, decarbonization measures, and climate resilience resource planning respectively, that mainly through regulatory means. Secondly, the EU Climate Change Adaptation Strategy provides a non-binding, but detailed roadmap to improve climate resilience at all levels of governance. It addressed food (drought resistance), energy (infrastructure adaptation), and water (water security) [78]. This strategy relies on informational and organizational measures, such as knowledge sharing platforms, but still focuses on departments. Thirdly, the Fit for 55 Package aims to reduce EU greenhouse gas emissions by 55% by 2030 through reforms in the energy, transportation, and industrial sectors [80]. The plan includes market-based tools such as carbon pricing and renewable energy quotas. The heat waves caused by climate change exacerbate the vulnerability of FEW systems. The EU’s Fit for 55 packages indirectly mitigates these risks through emission reduction and energy transition measures. However, it focuses on mitigation and has limited direct adaptation measures for the interactions of FEW systems.

The integration of FEW linkages in EU climate policy is mostly implicit. Departmental policies, such as the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), Water Framework Directive, and Renewable Energy Directive, while promoting climate adaptation in their respective fields, lack systematic planning tools to link food, energy, and water resources [79]. For instance, renewable energy policies may have indirect impacts on water resources and food systems through hydropower or bioenergy, but these interactions have not been incorporated into formal planning. It also lacks multi-system coordination tools, such as joint FEW early warning systems or unified monitoring platforms.

Regarding risk monitoring and response, EU policy documents explicitly recognize heat waves as major public health and economic risks [81]. Risk identification typically occurs at the national level, while the Copernicus and the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) use multi-parameter indices including temperature thresholds, duration, and humidity. Monitoring and early warnings are managed by predictive services at the EU level, with the EEA providing vulnerability distribution maps. In practical operation, member states implement Hot Health Action Plans (HHAPs), including opening cooling centers, issuing public recommendations, and targeted information dissemination to vulnerable groups [79]. In cross-border crises, the EU civil protection mechanism can be activated. However, the operational definitions and thresholds for triggering measures vary among member states, and a unified EU legal standard for triggering measures is lacking. To conclude, while EU policies are well developed at designing stage, their effectiveness depends heavily on member states’ implementation capacities, which leads to uneven outcomes. Strengthening joint cooperation, resource coordination, and data sharing among member states will be keyways to enhance climate adaptation capabilities.

3.3.2. United States

The United States tackles climate risks to its food, energy, and water systems through a multi-layered federal approach. Federal, state, and local governments all play a role, each with clear responsibilities across areas like climate policy, agriculture, water, and energy. This design protects the independence of each level while providing a basic framework for cross-system collaboration [82].

At the institutional level, the Department of Energy (DOE) works to strengthen energy infrastructure, making it more resilient against disruptions. Meanwhile, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) addresses agricultural adaptation and monitors food security. At the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the primary concerns are water quality and overall environmental health. When disasters hit, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) steps in to coordinate the response. On the legislative side, Congress sets up the legal framework and approves funding through new laws, and to tie everyone together, coordination usually happens through groups like the White House OSTP or special interagency task forces. It is essential to note that although agencies have developed climate risk responses within their respective areas, the US lacks a permanent interagency body specifically dedicated to integrated FEW nexus governance [83].

At the policy level, representative policies are selected for analyzing. The federal Modernizing Extreme Weather and Heat Response Act (2024) serves as a guiding policy. It emphasizes regulatory and informational tools to enhance system resilience. This Act requires modernizing water and power infrastructure, establishing water–energy coordination systems, and linking weather monitoring with emergency management platforms—measures aimed at reducing systemic risks from heat waves at the points where water and energy systems interact [84]. Similarly, the 2024 report Extreme Heat Emergency Response: Federal Assistance and Congressional Considerations focus on resource allocation. It recommends protecting vulnerable groups through farm support, energy supply guarantees, and emergency drinking water provisions. It also encourages states to develop localized response plans and promotes faster delivery of aid resources [85].

State-level policies tend to be more hands-on. Take New York State’s 2020 Extreme Heat Policy Agenda, for example. It focuses on community mobilization through improved information sharing and coordination. The plan includes practical steps such as setting up cooling centers, strengthening cold chains for food supplies, introducing time-based electricity pricing to ease grid pressure, and incorporating water supply management into emergency planning. It is a good example of how local approaches can adapt more flexibly to manage resources. Meanwhile, the USDA-led Federal Assistance for Agriculture in Extreme Heat (2024) combines market incentives with information sharing by providing subsidies, insurance, and technical guidance to affected farmers, while promoting adaptive measures such as water-saving irrigation and heat-resistant crops, and managing agricultural electricity use [86]. Notably, the 2023 Congressional document Climate Change and Extreme Heat explicitly proposed a cross-agency coordination platform, calling for the integration of climate data, infrastructure management, emergency response, and social safety nets into a unified framework—one of the few high-level policies directly targeting FEW system integration [87].

However, when it comes to governing the FEW nexus, the U.S. still faces some stubborn challenges. Policy integration tends to happen indirectly. Many measures address vulnerabilities within individual systems, such as strengthening water infrastructure or managing grid load, but they often overlook the connections between these systems. For example, water-saving farm upgrades might use more power for irrigation, straining energy supplies, while heat-response plans for the grid can overlook competition for water between power plants and crops. Coordination between agencies is mostly reactive, triggered by emergencies rather than built into long-term planning. Agencies like NOAA and the NWS operate advanced heat alert systems and collaborate with local groups to establish cooling centers and implement public health measures [87], so the groundwork is in place, even if nexus-level thinking is not, yet.

3.3.3. Japan

The climate, energy, food, and water sectors are largely centralized in Japan where the main control rests on a national scale [88]. Ministries of particular importance to climate policy and energy systems are the Ministry of the Environment (MOE) and the Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry (METI); those in charge of agricultural development and food security are the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries (MAFF), and the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport, and Tourism (MLIT), which addresses water resources and other infrastructural issues [89,90,91,92]. The Cabinet Office, Disaster Management Bureau is the center of governance over heat waves and the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) works in coordination with the local government to provide warnings and enact emergency measures. The Climate Change Adaptation Act (2018, amended in 2021) requires adaptation plans at both national and local levels; nevertheless, cross-cutting implementation is still on the level of individual ministries. This leaves institutional integration, even within the FEW nexus, wanting, which may limit systemic responses to related climate stressors [89,93].

Among the existing national strategies related to climate change and sectoral resilience, three policies can be identified as illustrative segments of Japan’s approach to addressing heat waves and other issues associated with the FEW system pressures. The Climate Change Adaptation Act is the first to provide a legal framework for adaptation planning at the ministry and government levels. Although it does not mention the FEW nexus directly, it demands that public authorities treat risks related to extreme weather, such as heat waves, drought, and water shortages, etc. The Act functions primarily through regulatory and institutional instruments, mandating climate risk assessments and the development of local adaptation plans, with optional participation from private sector stakeholders [93]. The 6th Strategic Energy Plan is the second important document that provides the development strategy of Japanese energy supply in terms of stable and decarbonized energy sources kept in spite of the rise of climate variability [94]. The plan proposes a set of technological and market-based solutions, including demand response programs, decentralized renewable energy generation, and investments in heat-resilient infrastructure. The third representative policy is MAFF’s adaptation initiatives, as described in the Climate Change Adaptation Plan, which promote the use of advanced digital technologies—such as precision irrigation, real-time crop stress monitoring, and heat-resilient crop breeding—to adapt agricultural systems to climate stressors [89]. While it does not explicitly address energy or water governance, it introduces incentive-based mechanisms and infrastructure support to promote water-efficient and heat-tolerant agricultural practices.

The integration of the FEW nexus in Japan’s national policy framework remains largely implicit. Though individual policies address sector-specific vulnerabilities—such as irrigation demands during heat waves or grid stability under peak load conditions—there is little evidence of systemic coordination between sectors. For instance, MAFF’s promotion of water-efficient irrigation does not account for the increased electricity required to power such systems, while METI’s planning for heat-induced electricity surges overlooks potential competition with agricultural and urban water needs [90,95]. There are no operational joint early warning systems, shared data platforms, or synergistic policy instruments that bridge the energy, water, and food sectors.

However, Japan specifically recognizes heat waves and extreme heat as critical climate risks. The JMA has used evident temperature level thresholds to coin terms—such as days exceeding 35 °C—to issue public health alerts. Since 2021, the nationwide Heatstroke Alert System has also provided early warnings in collaboration with local governments, triggering actions such as the opening of cooling shelters, dissemination of behavioral guidance, and activation of emergency care networks [89,96]. Governance responses are well coordinated through the Cabinet Office and MOE, with municipal authorities leading on-the-ground implementation. While this system could effectively address health-related risks, its extension to FEW system vulnerabilities, such as the impact on crop yields, cold-chain logistics, or hydropower generation might still remain underdeveloped. Overall, Japan has well-established institutions that respond to heat-related health risks, but a lack of coordinated sectoral governance remains.

3.3.4. China

China implements a centralized, state-led governance model in climate change adaptation and resource management. In this model, the central government formulates policy and strategic frameworks, while local governments are responsible for implementing these frameworks and providing feedback [97]. The State Council’s Leading Group for Climate Change Response and Energy Conservation and Emission Reduction, chaired at the vice-premier level, is responsible for top-level coordination. This group integrates the functions of the Food–Energy–Water (FEW) system and related public safety sectors [98]. Heat wave governance follows a pattern of central monitoring and local implementation. Meanwhile, policy instruments are mainly regulatory and informational, with representative policies including.

National Climate Change Adaptation Strategy 2035 [99]: The first to include a special section on “health risks from high-temperature heat waves”. It also requires new energy projects to assess the interaction between water and energy. While it helps identify health risks and plan for energy, farming adaptations mostly focus on saving water using less irrigation. They do not consider energy costs or managing water resources in a coordinated way.

Outline of the Yellow River Basin Ecological Protection and High-Quality Development Plan [100]: This plan proposes a strategy for basin development that emphasizes the coordinated use of water, food, and energy. It also includes the establishment of a FEW trading market, where agricultural water-saving credits can be exchanged for wind power development quotas. Additionally, the plan involves the piloting of investments in bundled photovoltaic and drip irrigation technologies. This mechanism has fostered innovative cross-sectoral resource allocation pathways and achieved initial success in some provinces of the Yellow River Basin. However, the scope of coverage is currently confined to nine provinces (regions) within the basin, with no explicit timeline or institutional framework in place for a nationwide implementation.

Regulations on the Prevention of Meteorological Disasters of Jiangsu Province [101]: At the local level, this regulation created a linkage mechanism between meteorological warnings, power grid load dispatching, and agricultural production management. It stipulated that power grid enterprises must integrate with meteorological warning systems and adjust power load allocations 72 h in advance after a red high-temperature warning is issued. Furthermore, agricultural greenhouses are required to activate shading, ventilation, and power control systems concurrently during periods of extreme heat to mitigate crop heat stress. Nevertheless, the financial constraints associated with the high costs of equipment retrofitting continue to impede the adoption of these technologies by smallholders.

Nevertheless, a systematic framework for fully integrating the interdependencies of food, energy, and water systems remains conspicuously absent. Chinese policies across systems are marked by implicit, localized linkages. While certain measures address vulnerabilities within single sectors (e.g., scheduling irrigation during heat waves or ensuring grid stability during peak loads), there is limited evidence of systemic cross-sectoral coordination [102]. Also, there is still no joint warning system that can be used by all of these sectors, no cross-sectoral data platform, and no coordinated policy tools among the energy, water, and agriculture sectors.

Regarding the identification and response to heat waves, the Regulations on the Prevention of Meteorological Disasters and the Measures for the Issuance of High Temperature Heatwave Warning Signals explicitly use terms such as “high-temperature heat wave” and “extreme heat”. A nationally unified grading standard based on temperature thresholds and duration (≥35 °C yellow, ≥37 °C orange, ≥40 °C red) is adopted; however, it does not sufficiently account for climatic zone differences [103]. Table 6 illustrates the main responsibilities of China’s key ministries in heat wave governance. The sequence of response chain is as follows: The CMA issuing warnings, the MEM initiates cross-departmental responses, and local governments implement measures such as opening cooling centers and adjusting work schedules. The NHC issues heatstroke prevention guidelines. At the same time, the MARA and the MWR also use irrigation before they send it out to crops in areas with severe drought. This system has proven effective in reducing health risks, but it has not been able to systematically integrate risks to the food, energy, and water systems.

Table 6.

Main roles of China ministries in heat wave governance.

3.3.5. India

India’s governance of the food–energy–water nexus is shaped by its demographic and ecological constraints. With 18% of the global population but only 4% of the world’s freshwater resources, the country is among the most water-stressed nations worldwide [104]. These constraints are exacerbated by rapid urbanization, climate variability, and intensifying extremes such as droughts and heat waves, which disrupt agriculture, water supply, and electricity demand. Public policies have sought to address each sector individually, while gradually incorporating integrative approaches; however, nexus thinking remains inconsistently embedded.

The institutional architecture reflects strong central policymaking combined with state-level adaptation. The National Action Plan on Climate Change (NAPCC) and its sectoral missions, covering water, agriculture, and renewable energy, provide a broad framework [105]. The National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA), under the Ministry of Home Affairs, plays a unique coordinating role by translating global climate agreements into sectoral guidelines. Its Heat Wave Guidelines (2019) and disaster management protocols exemplify how disaster governance acts as a linkage across ministries and states, embedding water, energy, and food considerations into risk management [106].

Water governance has historically been central to nexus challenges. The successive National Water Policies of 1987, 2002, and 2012 progressively emphasized sustainability, efficiency, and basin-level planning [107]. The Ministry of Jal Shakti, established in 2019, consolidated national-level water portfolios. Flagship initiatives include the Jal Jeevan Mission (JJM), which aims to provide functional household tap water, and the Atal Bhujal Yojana, promoting community-based groundwater management in stressed aquifers [108,109]. States have developed complementary innovations: Karnataka’s State Water Policy (2019/2022) proposed a framework law and basin-level authorities [110]; Telangana’s Mission Bhagiratha built a state-wide piped water grid [111]; and Maharashtra’s Jalyukt Shivar programme emphasized decentralized watershed management [112]. These examples demonstrate how water policy mediates both agricultural productivity and energy demand for irrigation.

Energy policy reforms have equally significant implications for the nexus. India’s commitment to 500 GW of non-fossil capacity by 2030 is driven by the National Solar Mission and the Pradhan Mantri Kisan Urja Suraksha evam Utthaan Mahabhiyan (PM-KUSUM), which expands solar-powered irrigation and decentralized generation [113,114]. While these reduce reliance on subsidized electricity and fossil fuels, they also risk unsustainable groundwater pumping without regulatory checks (Atal Bhujal Yojana provides partial safeguards). Complementary initiatives such as the Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana expand access to clean cooking fuels, reducing biomass dependence and improving health, while indirectly relieving pressure on ecosystems [115].

Food policy is anchored in the National Food Security Act [116], which guarantees subsidized cereals to nearly two-thirds of the population. While ensuring caloric security, NFSA has reinforced procurement of water-intensive rice and wheat, intensifying water and energy pressures. To counterbalance these outcomes, the National Mission for Sustainable Agriculture (NMSA) promotes climate-resilient practices, and the Pradhan Mantri Krishi Sinchayee Yojana (PMKSY) advances micro-irrigation for water-use efficiency under the principle of “per drop, more crop” [117]. These measures represent incremental efforts to embed resource efficiency into food security policy.

Disaster risk governance illustrates how the FEW nexus is increasingly addressed under climate stress. NDMA’s Heat Wave Guidelines (2019) and local Heat Action Plans, such as those in Ahmedabad, integrate water access, electricity reliability, and public health measures into anticipatory responses [118]. Emergency water provisioning, cooling centers, and power backups for hospitals illustrate how resilience planning connects across the nexus.

Despite advances, fragmentation continues to undermine policy integration. Ministries often operate in silos, with agricultural subsidies, electricity tariffs, and water allocations poorly aligned. Data deficits at the aquifer and basin scale hinder planning, and state capacities remain uneven. Incentives such as free electricity for agriculture and procurement of water-intensive crops perpetuate unsustainable practices [119]. Climate extremes amplify these vulnerabilities, underscoring the need for stronger coordination between global commitments, national missions, and state programs.

Yet promising examples suggest a path forward. Mission Bhagiratha in Telangana demonstrates universal access to piped water through integrated planning; Maharashtra’s Jalyukt Shivar highlights the role of decentralized watershed management; and Karnataka’s reforms show the need for legal frameworks and institutional restructuring. Heat Action Plans illustrate how disaster management fosters cross-sectoral coordination. These examples indicate that while integration is still partial, embedding FEW nexus thinking systematically into policy is both possible and urgent. Strengthening NDMA’s role, advancing state reforms, and aligning incentives with basin-scale planning and climate adaptation will be critical for practice. Systemic approaches are essential for reconciling competing demands and building resilience to climate risks.

Finally, a comparative analysis of five regions reveals several common patterns and differences (Table 7). In terms of governance structure, the United States and India adopt federal systems with shared authority between national and subnational levels, whereas Japan and China rely on more centralized, ministry-led or top-down governance arrangements. The European Union operates under a distinct configuration, characterized by supranational legal frameworks combined with implementation by member states. Although these governance structures differ substantially, such institutional variations do not necessarily result in stronger integration of food, energy, and water systems. With respect to governance scale, all regions involve multi-level governance, though the extent and form of vertical coordination vary. The EU spans supranational to local levels, while governance in Japan and China is primarily organized around national–local linkages. Regarding dominant systems, policy responses are framed through different sectoral entry points, including public health and disaster response in Japan and the United States, energy–water security in China, and water–agriculture concerns in India. In terms of policy instrument profiles, regulatory and planning tools constitute the main governance approaches across five regions, complemented to varying degrees by market-based mechanisms, informational instruments, and localized pilot initiatives. Overall, coordination across food, energy, and water systems remains largely implicit or uneven. Cross-sectoral coordination is often episodic or localized, particularly in the United States and China, while in India, institutional integration is more evident within disaster governance contexts. Nevertheless, critical gaps exist across these regions, including fragmented implementation, limited cross-sector coordination, and inadequate incorporation of cross-system trade-offs in the face of escalating heat-wave threats.

Table 7.

Summary of major similarities and differences in heat wave governance.

4. Discussion

4.1. Key Findings

The bibliometric analysis demonstrated a variety of trends in this field. The number of publications has increased significantly since 2020. This surge likely reflects a combination of factors, including heightened awareness following recent high-impact heat events (such as the 2019 European Heatwave), expanding climate-risk research funding, and growing international policy and media attention to climate impacts during the IPCC Sixth Assessment cycle. However, the bibliometric data do not allow us to attribute this increase to any single driver. At the same time, the strong clustering of post-2020 papers around specific recent heat events suggests a predominantly reactive orientation: research tends to analyze crises after they occur rather than to anticipate future extremes and their FEW-nexus implications. This temporal lag between extreme events and academic output limits the extent to which the field currently supports anticipatory governance, for example by informing early-warning systems and ex-ante adaptation planning.

The breakdown of keyword clusters shows that agronomic stressors such as wheat, high levels of CO2, and flash drought events have become topical areas of interest. Such a trend could be traced to an increased awareness of how heat waves destabilize biophysical processes at the crop–physiology interface. On the contrary, key conceptual terms, including food security, resilience, and sustainable agricultural production, seem to be theoretically coherent.

Patterns at the journal level indicate a disparate concentration of influence among a small group of climatic–agricultural researchers, particularly those working at the intersection of hydrological modeling and energy-system resilience. A simple geographic breakdown of the 103 papers shows that 55 include European case studies and 46 include North American cases, with only 11 examining South Asia and 6 addressing sub-Saharan Africa (including multi-country and multi-region studies). In other words, we found that less than one in ten papers in our sample covers South Asia and fewer than one in fifteen covers sub-Saharan Africa, even though both regions are widely recognized as heat-vulnerability hotspots. This pattern reinforces concerns about the limited Global South representation in the current literature and raises serious doubts about the representativeness of vulnerability profiles at the international level and of how authorship and citation networks continue to marginalize highly exposed regions.

Collectively, the results highlight an emerging but unbalanced discipline in which scientific creativity has preceded theoretical synthesis and international fairness in research priorities. Filling this gap will need further transdisciplinary interaction, as well as more investment in Global South knowledge systems.

A scoping review was conducted to clarify the impacts of heat waves on the FEW nexus and its mechanisms. Findings indicate that the most often described effect is agricultural losses, which further reflect the susceptibility and complexity of the food system. At the same time, the strain of energy availability and water shortage are often co-morbid, which implies that cross-system risks are triggered by heat waves due to the interaction of increased demand and restricted supply. Moreover, under extreme heat, infrastructural stress and cross-sectoral perturbations increase, hence illustrating the compound vulnerability that the nexus bears. However, significant gaps remain in the existing evidence base.

To begin with, the identification of mechanisms of interaction is obstructed by a preference of single-system studies. The literature primarily focuses on the direct impacts on individual systems (e.g., crop yield reduction or electricity load), but there is a lack of literature that investigates the interactions across systems. This methodological bias leads to an underestimation of competition and the feedback loop of resources, thus restricting an in-depth explanation of the process by which heat waves develop systemic crises.

Second, mechanistic insight is limited by inherent limitations in both spatial and temporal scales. Most studies are conducted on a regional or national scale, with multi-year or annual time resolutions. Although these studies provide an insight into long-run patterns, threshold risks of extreme heat are ignored. In fact, the danger of heat waves comes to a head at critical points where crops are subjected to heat stress during critical developmental stages, there is peak electricity demand, or the water temperature rises above ecological levels. Lack of short- term high frequency data hinders the precise recording of the discrepancy between surging demand and limited supply in the short term.

Third, the maladaptation paradox deserves closer attention. Lacking cross-system coordination, some adaptation measures may exacerbate stress in other systems. For instance, agricultural water-saving interventions may increase electricity demand, while response measures in power grids may further exert stress on water resources [15,20,75]. Such maladaptation outcomes highlight institutional risks in heat wave adaptation and the inadequacy of single-sector optimization in building overall resilience.

The policy analysis reveals different governance models in response to heat wave impacts on the FEW nexus across countries. Despite the extensive institutionalization of regulatory arrangements and digital instruments, market-based and incentive schemes remain underutilized. There are also obvious disparities in policy implementation across regions, particularly along urban–rural lines.

At the same time, these cases show distinct strengths. Under the guidance of the European Climate Law, the European Union has developed a multi-level governance regime and a powerful database; however, differences among member states have resulted in inconsistent application and the absence of a unified energy–water monitoring platform. The United States has established a multi-level and highly developed system of public health response, supported by a wide range of policy tools, including regulatory, market-based, and informational instruments, yet it lacks a unified approach to water and energy efficiency. Japan has prioritized scientific and technological innovation and the development of disaster preparedness systems, becoming an international leader in smart farming and energy-saving technologies; however, departmental barriers continue to hamper coordination. China’s centralized governance system has enabled rapid localization and large-scale water–energy distribution, but the energy sector remains insufficiently involved. Recent trends in India, particularly in water governance, energy transition, and food reform, indicate potential pathways toward integration; however, these efforts remain limited and highly dependent on institutional coordination at the national level and reform at the state level.