Abstract

In the context of the global pursuit of the ‘carbon neutrality’ objective, Chinese enterprises are proactively advancing green development and low-carbon transformation. Among these efforts, climate transition risks have emerged as a crucial factor affecting strategic enterprise decisions and long-term competitiveness. This study utilizes a sample comprising Chinese A-share listed enterprises over the period from 2012 to 2024 to construct an enterprise climate transition risk index using text analysis methods. It empirically investigates this index’s impact on enterprise green innovation by adopting panel data analysis method to construct a fixed effects model and further examines the moderating roles of institutional investors’ shareholding and enterprise environmental uncertainties in response to climate transition risks. The research findings indicate the following: First, climate transition risks significantly enhance enterprise green innovation. The validity of this conclusion persists following a series of robustness and endogeneity tests, including replacing the explained variable, lagging the explanatory variable, controlling for city-level fixed effects, and applying instrumental variable methods. Second, both institutional investors’ shareholding and enterprise environmental uncertainties exert a significant positive regulatory effect on the relationship between climate transition risk and green innovation, indicating that external monitoring and heightened risk perception jointly enhance enterprises’ responsiveness in driving green innovation. Thirdly, heterogeneity analysis indicates that the positive impact of climate transition risks on green innovation is notably amplified within non-state-owned enterprises and manufacturing enterprises. By examining the dual regulatory mechanisms of ‘external monitoring’ and ‘risk perception’, this study broadens the study framework on the relationship between climate risks and enterprise green innovation, offering new empirical evidence supporting the applicability of the ‘Porter Hypothesis’ within the context of climate-related challenges. Furthermore, it provides valuable implications for policymakers in refining climate information disclosure policies and assists enterprises in developing forward-looking green innovation strategies.

1. Introduction

In the context of escalating global climate change and the international consensus on the ‘carbon neutrality’ goal, enterprises, as the main body of economic activities, are confronted with profound transformational pressure from policy, market, and technology perspectives. Climate risks, particularly the climate transition risks arising from green development and low-carbon transition, have evolved from potential external challenges into core elements that influence enterprises’ strategic decisions and long-term competitiveness [1]. As an active advocate and practitioner of the ‘dual carbon’ goal, a comprehensive green and low-carbon shift is underway across China’s economy and society through a robust framework of policies and regulations. In this context, how Chinese enterprises address climate-related transition risks and harness them as catalysts for green and innovative development is not only critical to their own long-term sustainability but also holds substantial significance for the successful implementation of the nation’s carbon neutrality strategy.

Green innovation serves as a critical strategy for enterprises to achieve energy efficiency improvements, reduce emissions, and attain a sustainable competitive advantage in the context of environmental sustainability [2]. The existing literature has extensively examined the driving effects of traditional factors, such as environmental regulations [3] and government subsidies [4], on enterprise green innovation. And green innovation has a positive impact on enterprise performance [5]. However, there remains a notable gap in research regarding how forward-looking and systemic changes—arising from anticipated shifts in policies, technologies, and market preferences in response to climate change, commonly referred to as climate transition risks—influence enterprises’ green innovation behaviors. On the one hand, the transformation risks related to adapting to climate change can potentially curtail enterprises’ innovation investment by elevating compliance costs and resulting in asset stranding, among other methods. On the other hand, these risks may also ‘compel’ or ‘spur’ enterprises to undertake green technological innovation via mechanisms such as uncovering future market opportunities and enhancing investor attention. Ascertaining this net effect and its scope of action is an essential aspect of comprehending the behavioral logic of enterprises in the carbon-neutral era.

Moreover, the impact of climate transition risks on enterprise green innovation does not occur in isolation; rather, it is embedded within specific enterprise governance structures and external environmental contexts. Subsequently, as a significant external monitoring mechanism, can institutional investors’ shareholding strengthen enterprises’ focus on long-term climate-related risks and thereby enhance the positive impact of transition risks on green innovation? Zhang et al. (2025) demonstrates that an increase in pressure-sensitive institutional investors shareholding strengthens the positive impact between managerial climate awareness and firms’ sustainability performance [6]. And the effect of multiple large shareholders (MLSs) plays a monitoring role in environmental, social, and governance (ESG) controversies and contributes to firm value by reducing their negative consequences [7].

Furthermore, does the climate risk perception arising from environmental uncertainty either dampen managerial responsiveness to transition risks or, conversely, heighten their urgency to pursue innovative breakthroughs? Some researchers constructed a synthesized Chinese-context climate risk perception index to analyze the relationship between climate risk perception and green innovation [8], or ESG performance [9]. Other researchers employed difference-in-differences (DID) analysis with the Paris Agreement as a policy shock to examine enterprise risk perception [10]. Therefore, by investigating institutional investors’ shareholding and climate risk perception caused by environmental uncertainty, those two regulatory mechanisms can provide deeper insights into the transmission pathways through which climate risks influence enterprise micro-level behaviors. The existing literature has not offered a definitive answer to these questions.

Based on the above-mentioned realistic background and theoretical gap, this study uses Chinese A-share listed enterprises from 2012 to 2024 as the research sample and attempts to conduct an in-depth exploration of the following questions: First, can climate transition risk significantly enhance enterprise green innovation? Second, does this impact show heterogeneity among enterprises with different property rights and industry characteristics? Third, what regulatory roles do institutional investors’ shareholding and enterprise environmental uncertainty play in this process?

This study seeks to make several principal contributions, which are summarized in the following points: First, it enhances quantitative research on climate risks by incorporating text analysis methodologies, thereby expanding the analytical toolkit available to researchers in this domain. Second, it empirically validates the positive impact of climate transition risks on enterprise green innovation through an incentive-based perspective, offering new empirical support for the Porter Hypothesis within the context of climate-related risks. Third, by integrating institutional investor’s shareholding and environmental uncertainty as regulated variables, this study identifies two distinct boundary conditions—external monitoring mechanisms and internal risk perception—thereby deepening the understanding of the underlying mechanisms through which climate risks influence enterprise behavior. Finally, the findings yield practical implications for supervision departments seeking to refine climate information disclosure policies, facilitate capital market engagement in green innovation, and assist enterprise managers in developing forward-looking climate strategies.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Climate Transition Risk Evolution

A consensus has been established in academic research regarding the classification framework of climate risks. The prevailing approach categorizes these risks into two primary types based on their sources and transmission pathways: physical risks and transition risks [1,11]. Physical risks pertain to the direct impacts of climate change on enterprises, encompassing both acute extreme weather events—such as hurricanes, floods, and extreme heat—and chronic climatic shifts—including sea level rise and soil degradation [12,13]. These risks adversely affect business operations by damaging production infrastructure, disrupting supply chain flows [14], and diminishing total factor productivity [15]. In contrast, transition risks are inherent in the large-scale restructuring required for the global shift toward a low-carbon economy. These include stricter policies and regulatory measures (e.g., carbon taxes and emissions trading systems), technological displacement driven by low-carbon innovations (e.g., the replacement of fossil fuels by renewable energy), evolving market preferences (e.g., increasing demand for sustainable investment and consumption), and legal liabilities (e.g., penalties for non-compliance with environmental regulations). Collectively, these factors may result in stranded high-carbon assets [16] and financial disruptions, such as the collapse of traditional business models [17,18].

In terms of measurement methodologies, the academic community has observed a progressive shift from ‘macro-level proxy variables’ to ‘micro-level specific indicators’, reflecting enhanced adaptability to the Chinese institutional and economic context. Early studies predominantly relied on indirect, region-level proxies—such as the average temperature in the geographic area where an enterprise is located [19], drought indices [20], or exogenous climate policy events (e.g., the U.S. Renewable Portfolio Standard [21]). While these proxies offer advantages in data availability, they are limited in their ability to capture enterprise-specific climate risks stemming from the differing characteristics and business models across industries. With the application of tools drawn from text analysis and machine learning, the enterprise-level measurement of climate risk has become a central concern in contemporary scholarship. Some researchers developed word-frequency-based climate risk indicators by analyzing textual content in the ‘Management Discussion and Analysis (MD&A)’ sections of enterprises’ annual reports [22,23]. More recently, Gu et al. (2025) innovatively leveraged unstructured text data from investor interaction platforms on the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock exchanges (e.g., ‘Interactive Easy’ and ‘Shanghai e-Interaction’), constructing timely and targeted enterprise climate risk indicators based on the frequency and intensity of climate-related discussions between investors and enterprise management [24]. The validity of these micro-level indicators has been empirically supported through comparative analyses with real-world events and regulatory contexts: enterprises affected by natural disasters (e.g., typhoons and floods) exhibited significant increases in physical risk scores, while carbon-intensive industries (e.g., power generation and mining) demonstrated substantially higher transition risk scores compared to other sectors.

In response to the unique challenges of measuring climate risk within the Chinese context, scholars have advanced the methodological framework for indicator construction. A recent study employed the Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) topic modeling technique to analyze climate-related news texts from the HuiKe database spanning the period of 2000–2022. They developed the China Climate Transition Risk Index by integrating three dimensions: ‘climate policy risk’, ‘low-carbon technology risk’, and ‘market preference risk’. This approach not only mitigates potential selection bias inherent in enterprise self-disclosures but also enhances the comprehensiveness of the index through principal component analysis [18]. In contrast, another study emphasized lexical adaptability specific to the Chinese linguistic and institutional environment. Through a manual review of over 600 annual reports of A-share listed enterprises and an integration of data from the National Meteorological Science Data Center, they constructed a specialized climate risk dictionary comprising 98 core terms. Using the Continuous Bag of Words (CBOW) word vector model, they expanded this set with semantically related terms and subsequently quantified enterprise climate risk based on term frequency proportions in annual reports. The validity of their methodology is substantiated by multiple lines of evidence, including sectoral variation (with the highest risk observed in the power and heat supply industry), temporal patterns (a concurrent rise in transition risk and ESG scores), and qualitative sentence-level validation (where randomly sampled report excerpts align coherently with assigned risk categories) [25]. The progression of these measurement approaches establishes a robust methodological foundation for this study to precisely capture enterprise-level climate transition risks, particularly in distinguishing cross-dimensional heterogeneity across policy, technological, and market domains.

2.2. The Impact of Climate Transition Risks

2.2.1. The Impact on Enterprise Financial Policies

Climate risks can significantly influence enterprise financial policies. With respect to cash holding strategies, Javadi et al. (2023) demonstrate that regional drought risks heighten enterprise business uncertainty, leading enterprises to increase precautionary cash reserves—evidence drawn from a sample of enterprises across 41 countries [20]. Gu et al. (2025) further confirm that both physical and transition climate risks substantially elevate enterprise cash holdings by increasing the standard deviation of operating cash flow volatility (CFvol) and the expected default frequency (EDF) based on a sample of enterprises listed on Chinese stock exchanges [24]. This finding remains robust after controlling for agency motives, disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, and enterprises benefiting from favorable climate conditions (e.g., clean energy enterprises). Notably, cash reserves accumulated in response to climate transition risks are associated with a significant increase in the market value of cash, suggesting that such strategic behavior is positively recognized by financial markets.

Regarding financing costs, climate transition risks contribute to higher capital costs by increasing investor risk premiums. Chen et al. (2023) show that climate transition risks significantly raise the cost of equity capital and enterprise default probabilities [26]. Zhai et al. (2024) indicate that climate policy uncertainty increases bond financing costs [27]. Du et al. (2023), through a refined classification of risk types, find that transition risks—rather than physical risks—are significantly and positively correlated with the cost of equity capital, particularly in high-carbon industries such as mining and power generation [25]. This effect is attributed to heightened regulatory pressure and asset-stranding risks faced by high-carbon enterprises, which necessitate greater risk compensation from investors.

Furthermore, climate transition risks influence enterprise capital structure decisions. Ginglinger and Moreau (2023) observe that enterprises tend to reduce leverage to mitigate debt repayment pressures arising from climate-related uncertainties and to avoid potential financial distress [28]. At the same time, climate risks catalyze substantive business transformations, with green innovation playing a central role. Most studies support the ‘incentive’ effect of climate risks on green innovation. Xu et al. (2025) find that climate transition risks promote green innovation by enhancing enterprises’ environmental management intentions, intensifying competitive dynamics within industries, and encouraging greater transparency through environmental information disclosure [18]. Similarly, Tian et al. (2024) identify climate risks as a key driver of green innovation among Chinese enterprises, aligning with the theoretical framework of the Porter Hypothesis—the proposition that well-designed environmental regulation can stimulate innovation [29].

Nevertheless, some scholars caution that the uncertainty induced by climate transition risks may divert or crowd out resources allocated to innovation activities, potentially exerting a dampening effect on green innovation [30]. Consequently, the net impact of climate risks on green innovation requires careful empirical validation within specific institutional and industrial contexts.

2.2.2. The Dual Effects on Enterprise Green Innovation

A debate exists regarding whether climate-related risks stimulate or hinder green innovation in enterprises, a discussion framed by the contrasting perspectives of ‘forced promotion’ and ‘uncertainty suppression’. This discourse also engages with the theoretical propositions of the Porter Hypothesis. Most existing studies support the so-called ‘reverse forcing effect’. For instance, Xu et al. (2025), based on an empirical investigation of a sample of enterprises listed on Chinese stock exchanges, find that climate transition risks drive green innovation through three distinct mechanisms: first, by enhancing enterprises’ environmental management motivation—such as increased propensity to obtain certification of ISO14001:2015/Amd 1:2024 [31]; second, by intensifying industrial competition—particularly through the entry of low-carbon technology enterprises that stimulate market dynamics; and third, by promoting greater environmental information disclosure to meet investor demand for low-carbon transparency [18]. This effect is found to be more notable among non-heavy-polluting enterprises, state-owned enterprises, and enterprises with high resilience. Additional evidence indicates that policy and market pressures arising from climate transition risks lead enterprises to allocate more resources toward green technology research and development, which aligns with the Porter Hypothesis’s proposition that appropriately designed environmental regulation can stimulate innovation [29,32].

However, some studies have pointed out that the uncertainty of climate transition risk may have an inhibitory effect on green innovation. Wan et al. (2025) found that climate transition risk would reduce enterprises’ perception of long-term investment opportunities and crowd out green innovation resources [33]. Wang et al. (2024) further revealed that even if climate transition risks promote enterprise green innovation, there may be a tendency of ‘strategic innovation’ that is some enterprises (especially non-state-owned enterprises and manufacturing enterprises) will obtain policy subsidies through low-quality green utility model patents (rather than high-quality invention patents) in the context of green bond financial incentives and regulatory policies lagging behind [34]. This kind of strategic innovation can increase the number of innovations but cannot really improve the ability of enterprises to cope with climate risks. In addition, Du et al. (2023) pointed out that information asymmetry will amplify the inhibitory effect of climate risk on innovation, while institutional investors’ shareholding and analysts’ attention can alleviate this problem by reducing information friction, which provides an idea for the introduction of regulated variables in subsequent research [25].

2.3. The Role of Enterprise Green Innovation

Viewing green innovation as an important means to deal with climate-related risks reflects the evolving depth of academic inquiry in recent years. The traditional literature focuses on the driving factors of green innovation (including environmental regulation and government subsidies), while in recent years, scholars have begun to pay attention to how green innovation itself can help enterprises resist external risks.

Sun (2025) examined the issue from the perspective of reverse causality and employed data drawn from a sample of A-share listed enterprises spanning 2010 to 2023, demonstrating that green innovation mitigates enterprise climate transition risks through three principal mechanisms [35]. First, it reduces dependence on high-carbon assets and avoids asset stranding risks by facilitating technological upgrades—such as replacing fossil fuel-based equipment with new energy technologies. Second, it improves the quality of environmental information disclosure, thereby reducing information asymmetry between enterprises and investors and stabilizing expectations regarding asset values. Third, it strengthens supply chain resilience by optimizing production processes through green technologies, promoting coordinated emission reductions across upstream and downstream partners, and minimizing the risk of supply chain disruptions—particularly in the context of extreme weather events. His study represents the first systematic validation of the ‘risk mitigation’ role of green innovation, challenging the conventional unidirectional ‘risk → innovation’ framework and highlighting its strategic significance in enabling ‘innovation → risk reduction’.

Similarly, Benincasa et al. (2024) treated extreme weather events as exogenous shocks and found that enterprises tend to restore their production resilience through increased investment in green assets following physical losses caused by climate-related risks—such as energy-efficient equipment and low-carbon technology research and development [36]. Wang et al. (2024), within the context of digital transformation, further demonstrated that enterprise digitalization—particularly through technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI) and cloud computing—can enhance the resilience of green innovation in the face of climate risks by strengthening substantive green innovation capabilities, as opposed to strategic or symbolic efforts [34]. Specifically, digital technologies improve R&D efficiency and reduce information processing costs, enabling enterprises to develop higher-quality green patents and thereby more effectively reduce their dependence on high-carbon assets.

3. Theoretical Analysis and Hypotheses

Based on the above literature review, climate transition risks significantly influence enterprise strategic decision-making by shaping the external constraints and opportunities that enterprises encounter. This study seeks to examine the impact of climate transition risks on enterprises’ green innovation, as well as the underlying mechanisms involved. The subsequent section will integrate the Porter Hypothesis with risk management theory to formulate the research hypotheses of this study.

3.1. The Relationship Between Climate Transition Risks and Enterprise Green Innovation

The impact of climate transition risks on enterprise green innovation may be characterized by two competing mechanisms: an inhibitory effect and a driving effect. On the one hand, the policy, technological, and market uncertainties associated with climate transition risks can heighten the unpredictability of future cash flows, leading management to adopt a more risk-averse posture and consequently reduce investment in long-term green innovation initiatives [34], thereby exerting an inhibitory influence. On the other hand, in accordance with the Porter Hypothesis, well-designed environmental regulation can trigger an innovation compensation effect [2]. Climate transition risks embody a forward-looking and systemic form of regulatory and market pressure. To mitigate potential financial exposures—such as future carbon taxes, stranded assets, and shifts in consumer demand—enterprises are incentivized to reconfigure their competitive advantages through green innovation [18,29]. This ‘reverse forcing’ mechanism reflects a strategic preventive motive: enterprises proactively pursue innovation to decrease dependence on high-carbon assets, develop low-carbon technologies and products, and enhance their adaptability to and leadership in the low-carbon economic transition [35]. Within the broader context of China’s vigorous pursuit of its ‘dual carbon’ goals, this driving effect—rooted in long-term strategic considerations—may outweigh the inhibitory effect. Enterprises that initiate green innovation strategies earlier are likely to secure more favorable positions in future low-carbon markets.

Based on the foregoing analysis, this study posits that although uncertainties may exert certain inhibitory influences, the long-term strategic pressures and emerging market opportunities embedded in climate transition risks are likely to prevail in shaping enterprise decision-making. As a result, these factors collectively generate a net positive impact on enterprise green innovation. Consequently, the central hypothesis of this study is formulated as follows:

H1.

Climate transition risks have a significant positive effect on enterprise green innovation.

3.2. The Effect of the Dual Regulatory Mechanism

3.2.1. Regulatory Effect of Institutional Investors’ Shareholding

As an important external governance force, institutional investors’ shareholding may strengthen the driving effect of climate transition risks on green innovation. First, from the perspective of governance supervision, institutional investors, especially press-resistant institutions (such as social security funds and public offering funds) that focus on long-term value, can effectively alleviate the myopic behavior of management [37]. In response to climate transition risks, such investors are more likely to support the allocation of resources toward green innovation initiatives that are conducive to the long-term sustainable development of enterprises [38,39], and may ensure the implementation of innovation strategies by including green performance in the assessment [34]. Second, from the perspective of resource empowerment, institutional investors can not only provide stable financial support but also introduce scarce resources such as technical information and R&D cooperation opportunities to enterprises [24], helping enterprises more effectively transform climate risks into actual innovation output. Therefore, the higher the shareholding level of institutional investors, the more capable and motivated enterprises are in transforming climate transition pressure into green innovation actions. Based on this reasoning, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H2.

Institutional investors’ shareholding positively strengthens the effect of climate transition risks on enterprise green innovation.

3.2.2. Regulatory Effect of Enterprise Environmental Uncertainty

Objective environmental uncertainty has important impacts on entrepreneurial decision-making, but entrepreneurs’ perception of uncertainty may be a more crucial factor [40]. Enterprise environmental uncertainty reflects the individual facing the specific operating environment risk and volatility, which can present enterprise perception of climate transition risk directly and objectively. This study argues that higher environmental uncertainty will enhance rather than weaken enterprises’ innovation response to climate transition risks. The reasons are as follows: first, the risk superposition effect. When an enterprise is in a highly uncertain business environment, the management is more sensitive to various risks [41]. Climate transition risks, as a systemic risk, combined with inherent operational risks will further highlight the survival pressure faced by enterprises, thus arousing their sense of urgency to seek breakthroughs and build new competitive advantages through fundamental green innovation. The second is the weakening of innovation path dependence. In a highly uncertain environment, the original business model and technology path may have failed, which reduces the opportunity cost and path dependence of green innovation and provides fertile ground for disruptive innovation [42]. Therefore, environmental uncertainty amplifies the ‘reverse forcing’ signal of climate transition risks and urges enterprises to respond to challenges through green innovation more actively. Based on this, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H3.

Enterprise environmental uncertainty will strengthen the promotion effect of climate transition risks on enterprise green innovation.

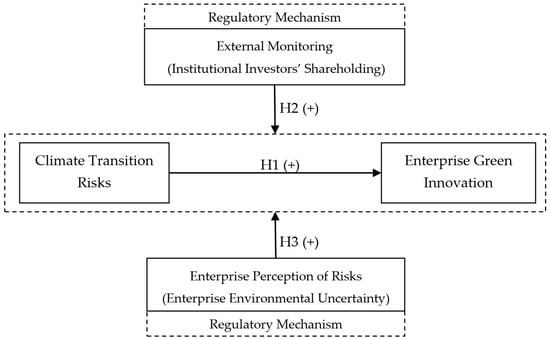

Therefore, a conceptual framework diagram that contains the regulatory mechanisms investigated in this study is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework diagram.

4. Model Setting and Data Source

4.1. Samples and Data

This study selects all A-share listed enterprises from 2012 to 2024 as the initial sample. To ensure the scientific rigor and reliability of the subsequent analysis, the following screening criteria are applied: (1) Enterprises labeled with special treatment (ST), those operating in the financial sector, and those with incomplete financial data are excluded; (2) observations with fewer than 30 weekly return records within a given year are also removed. After applying these filters, the final sample comprises 40,666 observations. All financial data used in this study are obtained from the China Stock Market & Accounting Research Database (CSMAR) (https://data.csmar.com/).

4.1.1. Measurement of Climate Transition Risks

Physical risks and transition risks represent the predominant classification framework for climate-related risks in contemporary research [43]. Building on foundational studies, climate risks can be further categorized into acute physical risks, chronic physical risks, and transition risks, with the first two subtypes constituting the broader category of physical risks [44,45]. Keyword sets associated with climate risks are classified according to these three dimensions: serious risks, chronic risks, and transition risks [25]. A comprehensive list of 98 keywords related to ‘climate risks’ was identified from the prior literature and applied to conduct textual analysis of annual reports of listed enterprises. This analysis yielded the frequency distribution of these keywords, which was subsequently used to construct a climate risk index—higher values of which indicate greater exposure to climate-related risks. This study primarily focuses on climate transition risks. In line with existing scholarly research, climate transition risk is defined in this study as the potential for financial losses, asset devaluation, or competitive disadvantages (Table 1) that enterprises may encounter during the transition toward carbon neutrality or a low-carbon economy, driven by shifts in policy frameworks, technological innovation, market dynamics, and evolving societal preferences.

Table 1.

Climate transition risks to enterprises.

4.1.2. Measurement of Enterprise Environment Uncertainty

Climate transition risks fundamentally arise from anticipated systemic shifts in future policies, technological advancements, and evolving market preferences. Stock prices represent a consolidated reflection of capital market expectations regarding an enterprise’s future cash flows. Consequently, the fluctuations in stock prices caused by enterprise-specific factors (i.e., the residual fluctuations after excluding market and industry influences) [46,47,48] can most sensitively and promptly capture divergent investor expectations concerning an enterprise’s capacity to manage transition risks. These pronounced differences in expectations underscore the high degree of environmental uncertainty faced by the enterprise.

The core independent variable in this study, ‘transition risk,’ inherently incorporates the effects of systemic shocks. To measure enterprise-level environmental uncertainty, this study employs a regression model to isolate enterprise-specific risk by removing the common effects of market and industry fluctuations (see model (1)) [49]. The resulting residual volatility reflects idiosyncratic risks unique to individual enterprises. This methodological approach ensures that the regulated variable—enterprise environmental uncertainty—is measured independently from the independent variable—climate transition risk—thereby enabling a robust examination of the hypothesis that ‘enterprises with higher inherent uncertainty exhibit a stronger innovation response’.

The measurement procedure is specified as follows: First, regress the weekly individual stock return of the i-th enterprise in the τ-th week of year t on the corresponding weekly market return and weekly industry return. The residual εiτ from this regression captures the enterprise-specific volatility component unexplained by market- and industry-level fluctuations. Subsequently, compute the standard deviation of all weekly residuals over the t-th year for the given enterprise and employ this value as a proxy for enterprise-level environmental uncertainty, as denoted by .

4.2. Model Setting

This study adopts panel data analysis method to constructs a fixed-effects model and controls for industry and year fixed effects to study the impact of enterprise climate transition risks on green innovation. The model is set up as follows:

where is the green innovation of enterprise i in year t, Trit represents the risk of climate transition, is the control variable, and are the fixed effects of industry and year, respectively, and is the error term.

The regulatory effect model is further constructed to examine whether institutional investors’ shareholdings and enterprise environmental uncertainty have regulatory effects on the impact of climate transition risks on enterprise green innovation. The model is set up as follows:

Here, is the regulated variable of institutional investors’ shareholding and enterprise environment uncertainty.

Green innovation (Gpatent) is measured as the natural logarithm of the number of green patent applications filed by enterprises within the year + 1. The following are defined: Regulated Variable: institutional investors’ shareholding (Sshare), measured as the proportion of institutional investors’ shareholding; enterprise environment uncertainty (En), the proxy variable of the environmental uncertainty of listed enterprise, which is . Control Variables: Enterprise size (Size) is measured as the natural logarithm of total assets; profitability (ROA) is measured as the net profit/total assets; enterprise cash flow (Cashflow) is measured as the cash flow generated by enterprise operating activities/total assets; enterprise growth (Growth) is measured as the growth rate of operating income; shareholding ratio of the largest shareholder (Top1), the shareholding quantity of the largest shareholder/total number of shares, the shareholding ratio of the top five shareholders; enterprise age (EnterAge) is measured as the natural logarithm of the difference between the current year and the year of establishment of the enterprise. The descriptive statistics of the variables defined above are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics.

5. Empirical Results and Discussion

5.1. Benchmark Regression Analysis

5.1.1. Correlation Analysis

As shown in the correlation analysis results listed in Table 3, the correlation coefficient between enterprise climate transition risks and enterprise green innovation is significantly positive. This indicates a positive correlation between the two: the higher the level of climate transition risk, the greater the level of enterprise green innovation.

Table 3.

Correlation analysis.

5.1.2. Regression Analysis

As shown in the benchmark regression results presented in Table 4, the coefficient on enterprise climate transition risk in Column (1) is 0.673 and statistically significant at the 1% level. In Column (2), after incorporating control variables, the coefficient remains positive and significant at the 1% level, with a magnitude of 0.504. These findings suggest that enterprise climate transition risk exerts a significant incentive for enterprises to engage in green innovation.

Table 4.

Benchmark regression results.

5.2. Robustness Test

5.2.1. Replace the Explained Variable

This study employs the natural logarithm of the number of green invention patent applications +1 (Gpat) and the proportion of green patent applications (Gpat1) to replace the explained variables for the robustness test. As shown in Table 5, the regression coefficients of enterprise climate transition risk in Columns (1) and (2) are significantly positive, which indicates that the previous conclusions are still robust after replacing the explained variables.

Table 5.

Robustness test.

5.2.2. Lag the Explanatory Variable

The regression analysis was conducted using one-period-lagged enterprise climate transition risk. As shown in Table 5, the regression coefficient of enterprise climate transition risk in Column (3) is significantly positive, which indicates that after lagging explanatory variables, enterprise climate transition risk still helps promote enterprise green innovation.

5.2.3. Control the Fixed Effects of Cities

City fixed effects are added to control for city characteristics in robustness tests. As shown in Table 5, the regression coefficient of enterprise climate transition risk in Column (4) remains positive and statistically significant, which indicates that enterprise climate transition risk can still promote enterprise green innovation after controlling for city characteristics.

5.3. Endogeneity Test

Considering the potential reverse causality that results in endogeneity issues, drawing on existing research [24], this study employs the average climate transition risk of other enterprises within the same industry and region as an instrumental variable (IV). The two-stage least squares instrumental variable approach is applied to mitigate endogeneity concerns. As presented in Table 6, the LM statistic of Kleibergen–Paap RK is significant at the 1% level, confirming the validity of the instrumental variable in identifying the model. Furthermore, the Wald F statistic of Kleibergen–Paap RK exceeds 16.38, indicating that the instrumental variable is not weak. In Column (1), the estimated coefficient on the instrumental variable is positive and statistically significant, while in Column (2), the coefficient on the enterprises’ climate transition risk remains positive and significant. These results suggest that, even after accounting for endogeneity, climate transition risk continues to have a robust positive effect on green innovation.

Table 6.

Endogeneity test.

5.4. Regulatory Effect Test

The regulatory effect test results are shown in Table 7. The regression coefficient of the interaction term (Tr × Sshare) between enterprise climate transition risk and institutional investors’ shareholding in Column (1) is significantly positive, which indicates that institutional investors’ shareholding plays a positive regulatory role in climate transition risk, promoting enterprise green innovation. The regression coefficient of the interaction term (Tr × En) between enterprise climate transition risk and enterprise environmental uncertainty in Column (2) is also significantly positive, which indicates that environmental uncertainty enhances the positive impact of climate transition risk on green innovation. These findings collectively imply that the influence of climate transition risk in promoting enterprise green innovation becomes stronger with higher levels of institutional investors’ shareholding and an increase in environmental uncertainty.

Table 7.

Regulatory effect test.

5.5. Heterogeneity Analysis

5.5.1. Nature of Property Rights

Considering the variations in climate transition risks and green innovation capabilities of enterprises with different property rights. This study divides the samples into state-owned enterprises and non-state-owned enterprises according to enterprises’ property rights for heterogeneity analysis. As shown in Table 8, the regression coefficients of enterprise climate transition risk in Columns (1) and (2) are significantly positive, but the coefficient in Column (2) is notably greater than that in Column (1), and the p-value for the between-group coefficient difference test using Fisher’s combined probability test is 0 000. This indicates that climate transition risks have a stronger positive impact on green innovation in non-state-owned enterprises compared to state-owned enterprises.

Table 8.

Heterogeneity analysis.

5.5.2. Different Types of Industry

Further consideration is given to whether the impact of climate transition risks on green innovation varies across different industries. As shown in Table 8, the regression coefficients of enterprise climate transition risk in Columns (3) and (4) are both significantly positive. However, the coefficient in Column (3) is notably larger than that in Column (4), and the p-value from the coefficient difference test between the two groups is 0.000, indicating a statistically significant difference. This result suggests that, compared to non-manufacturing enterprises, manufacturing enterprises experience a stronger positive effect of climate transition risks on green innovation.

6. Conclusions and Implications

6.1. Conclusions

This study applies Chinese A-share listed enterprises from 2012 to 2024 as the research sample to empirically investigate the impact of climate transition risk on enterprise green innovation, as well as its underlying mechanisms. The primary research findings are summarized as follows:

- (1)

- Climate transition risks exert a significant positive influence on enterprise green innovation. This finding remains robust after conducting a series of sensitivity analyses and addressing potential endogeneity concerns. The results suggest that, within the current macroeconomic context of China’s strong commitment to achieving the ‘dual carbon’ objectives, the transformational pressures stemming from policy shifts, technological advancements, and market dynamics are more accurately characterized as strategic opportunities that drive enterprises toward innovation, rather than merely representing sources of uncertainty or burden. This provides empirical support for the applicability of the Porter Hypothesis in the context of climate-related risks.

- (2)

- The impact of climate transition risks on green innovation is regulated by external monitoring mechanisms and enterprises’ environmental risk perception. Specifically, institutional investors’ shareholding strengthens this positive effect, suggesting that institutional investors play an active role in supervision and resource provision, thereby enabling enterprises to transform climate-related risks into drivers of innovation. Moreover, environmental uncertainty caused by climate-related risks is not a mitigating factor; rather, it amplifies enterprises’ responsiveness to climate transition risks, reflecting a ‘crisis-driven’ dynamic under conditions of compounded risks. These conclusions better demonstrate the relevant view that fewer large institutional investors’ shareholding and enterprise environmental uncertainty caused by climate-related risks will promote enterprise innovation, especially green innovation.

- (3)

- The impact of climate transition risks exhibits significant heterogeneity. The positive effect on green innovation is more pronounced in non-state-owned enterprises and manufacturing enterprises. This suggests that non-state-owned enterprises—facing tighter budget constraints and more intense market competition—and manufacturing enterprises—which play a pivotal role in emission reduction—are more sensitive and proactive in responding to climate transition risks. These conclusions are different from the previous studies on heterogeneity, which focused more on a certain industry with high carbon emissions, such as the energy industry or steel industry. However, the heterogeneity analysis of this study distinguishes the nature of enterprises and industries with high carbon emissions—mainly including manufacturing enterprises from those with non-high carbon emissions, and its conclusions are more universal and can be extended to most industrial countries.

6.2. Implications

6.2.1. For the Governments

- (1)

- Enhance and reinforce the mechanism for climate-related information disclosure. Empirical research indicates that transparent climate risk disclosures can effectively steer enterprise decision-making. However, due to the insufficiently sound information transmission mechanism for market climate information disclosure, there is an information asymmetry among investors, financial institutions and enterprises, which consequently reduces the effectiveness of the market’s spontaneous adjustment of resource allocation. So, we suggest supervision departments should expedite the development of standardized, comparable, and mandatory climate disclosure requirements, with a particular emphasis on mandating enterprise reporting of transition risks and corresponding mitigation strategies. A unified climate data system has the attributes of a public good. Government intervention can overcome the insufficiency of market supply and promote the improvement in climate risk management efficiency throughout society. Such measures will enable capital markets to accurately assess and price climate-related risks, thereby leveraging market mechanisms to incentivize enterprises to pursue green innovation.

- (2)

- Implement differentiated policy incentive and constraint mechanism. Through fiscal subsidies and tax levers, a ‘punishment–reward’ dual incentive mechanism is established to guide capital towards the low-carbon sector. And implement differentiated supervision based on the degree of climate risk exposure of industries or enterprises, affecting their financing costs and market valuations, and driving enterprises to proactively transform. So, given that non-state-owned enterprises and manufacturing enterprises are important responders to green innovation, guidance and support for policies should be more precisely targeted. For the manufacturing sector, measures such as setting up subsidies for green technology transformation costs and providing green special re-lending can be adopted to reduce their transformation costs. For non-state-owned enterprises, efforts should be made to create a fair competitive environment, ensuring they have equal access to green financial resources and technological support, thereby stimulating their innovation vitality.

- (3)

- Cultivate long-term institutional investors to construct governing and stability mechanism. Long-term institutional investors pay more attention to the sustainability and long-term risks of enterprises and promote the improvement in climate governance by exercising shareholder activism (such as voting and communication). And Long-term capital can alleviate the problem that enterprises neglect long-term climate investment due to short-term performance pressure and enhance the enterprise resilience in response to transformation risks. So, long-term, value-oriented institutional investors, such as social security funds and insurance funds, should be encouraged to participate in enterprise governance, guiding them to focus on long-term climate risk management and green innovation strategies and thereby cultivating the development of ‘patient capital’. Supervision departments may implement supportive measures, including tax incentives, to encourage institutional investors to integrate green innovation performance into their investment decision-making frameworks, reinforcing their role as both ‘stabilizers’ and ‘catalysts’ in sustainable market development.

6.2.2. For Enterprises

- (1)

- Improve the mechanism for adapting to and managing risks in enterprise strategies. If enterprises incorporate climate risks into investment decisions and retain flexibility to adjust production models or technologies in the future, they will avoid the risk of sunk costs. So, Climate transition risks should be integrated into the core strategic framework. Enterprise leaders should enhance their strategic comprehension of climate risk, abandon the mindset of passive compliance, and proactively embrace low-carbon transformation as an opportunity to build future competitive advantages. Climate scenario analyses should be conducted systematically to evaluate the potential impacts of transition risks on business models, and forward-looking green innovation strategies should be developed.

- (2)

- Optimize enterprise governance mechanism to address the environmental uncertainties caused by climate change. Enhancing the ability of enterprise managers to identify and monitor climate risks can ensure the effective implementation of strategies. So, enterprises should focus on introducing and listening to the opinions of long-term institutional investors, improving long-term incentive mechanisms for management, incorporating green innovation achievements into performance evaluations, and avoiding short-sighted behaviors. Furthermore, they should enhance strategic resilience in complex and uncertain climate-related risk environments and transform enterprise environmental uncertainties into the driving force for disruptive innovation.

- (3)

- Strengthen collaborative innovation mechanism between the climate risk management and supply chain management. By implementing supply chain contract designs (such as carbon tracking clauses and green procurement requirements), the pressure of climate transition risks can be transmitted to the upstream and downstream, which can promote emissions reduction throughout the entire chain. So, for manufacturing enterprises as main source of carbon emissions, they should extend their green innovation practices to the entire supply chain, promoting joint emission reductions and innovation among upstream and downstream partners and establishing a resilient and sustainable supply chain system. This integrated approach will systematically reduce overall exposure to climate-related transition risks.

Above all, these implications jointly build a chain economic mechanism from ‘macro policy guidance’ to ‘market signal transmission’, and then to ‘enterprise strategic response’ and ’industrial chain coordination’. Its core is to gradually transform climate negative externalities into endogenous cost and benefit considerations of market players through the path of ‘information transparency → risk pricing → incentive reconstruction → behavior change’, and finally promote enterprise performance to green and low-carbon transformation.

6.3. Limitations

Our study also has some limitations. Firstly, we adopt a sample of listed enterprises to test our hypothesis. But there are so many non-listed enterprises. They may also be compelled to engage in green innovation due to survival pressure or resource constraints and sensitive to perceptions of climate transition risks caused by environmental uncertainty. Therefore, using a sample of non-listed enterprises in future research could be interesting for studying this issue. Secondly, in heterogeneity analysis, we have made heterogeneity test for different types of industry just by dividing enterprises into manufacturing enterprises and non-manufacturing enterprises. Although manufacturing enterprises is the main source of carbon emissions, this type of industry still includes so many sub-industries, especially for emerging industries of strategic importance. So, in future research, we will focus on manufacturing industries whose activities cause the largest carbon footprint.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.C. and F.Z.; methodology, L.C.; software, L.C.; validation, L.C. and F.Z.; formal analysis, L.C.; resources, L.C.; data curation, L.C.; writing—original draft preparation, L.C.; writing—review and editing, L.C.; visualization, L.C.; supervision, F.Z.; project administration, L.C.; funding acquisition, L.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Shanghai Philosophy and Social Sciences Foundation Project: 2023BJB014.

Data Availability Statement

All data that support the findings of this study are included within this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- NGFS. Overview of Environmental Risk Analysis by Financial Institution Annual Report 2019. Available online: https://www.ngfs.net/system/files/import/ngfs/medias/documents/overview_of_environmental_risk_analysis_by_financial_institutions.pdf (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Porter, M.E.; van der Linde, C. Toward a New Conception of the Environment-Competitiveness Relationship. J. Econ. Perspect. 1995, 9, 97–118. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2138392 (accessed on 1 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; Li, D.; Wang, P.; Ma, R. Heterogeneous environmental regulation tools and green economy development: Evidence from China. Environ. Res. Commun 2023, 5, 15007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, S.; Shen, L.; Cui, J. Do environmental rights trading schemes induce green innovation? Evidence from listed firms in China. Econ. Res. J. 2018, 53, 129–143. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Jiang, J. The Role of Green Innovation Appropriability and Firm Performance: Evidence from the Chinese Manufacturing Industry. Sustainability 2025, 17, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Ma, R. Managerial Climate Awareness, Institutional Investors, and Firms’ Sustainability Performance: Evidence from China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Saleh, N.M.; Keliwon, K.B.; Ghazali, A.W. Can Multiple Large Shareholders Mitigate Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Controversies? World 2025, 6, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Gao, D.; Zhou, X. Nurturing Sustainability from Risks: How Does Climate Risk Perception Reshape Corporate Green Innovation. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Tan, L.; Wu, J.; Gao, D. From risk to sustainable opportunity: Does climate risk perception lead firm ESG performance? J. Int. Financ. Manag. Account. 2025, 36, 581–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.X.; Sun, M.N.; Yu, X.Y. The ‘Porter Hypothesis Puzzle’ of Carbon Risk and Audit Pricing: Empirical Evidence from the Paris Agreement. Audit. Res. 2022, 5, 75–84. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- TCFD. Recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures 2016. Available online: https://www.fsb.org/uploads/Recommendations-of-the-Task-Force-on-Climate-related-Financial-Disclosures.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Barnett, M.; Brock, W.; Hansen, L.P. Pricing Uncertainty Induced by Climate Change. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2020, 33, 1024–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, N.; Qiu, Q.; Luo, Y. Corporate climate risk and cash holdings: Empirical evidence from investor interaction platforms. Secur. Mark. Her. 2025, 5, 3–15. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Jean-Noël, B.; Julien, S. Input Specificity and the Propagation of Idiosyncratic Shocks in Production Networks. Q. J. Econ. 2016, 131, 1543–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Olivier, D.; Kyle, C.M.; Zhang, J. Temperature effects on productivity and factor reallocation: Evidence from a half million Chinese manufacturing plants. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2018, 88, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Yuan, J. China’s coal power sector stranded assets under the 2 °C global carbon constraint. Adv. Clim. Change Res. 2021, 17, 36–44. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Bolton, P.; Kacperczyk, M. Global pricing of carbon-transition risk. J. Financ. 2023, 78, 3677–3754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Wei, L.; Jin, K.; Wang, Y. Can the pressure of climate transition risks force enterprises to engage in green innovation?—Based on the risk of the LDA model decomposition and quantization. Shanghai Econ. Rev. 2025, 6, 61–75. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yu, M.; Ma, S.; Zhu, C. The alternating change of cold and warm extremes over North Asia during winter 2020/21: Effect of the annual cycle anomaly. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2022, 49, e2021GL097233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javadi, A.; Tomm, N.; Antoniadis, N.O.; Brash, A.J.; Schott, R.; Valentin, S.R.; Wieck, A.D.; Ludwig, A.; Warburton, R.J. Cavity-enhanced excitation of a quantum dot in the picosecond regime. New J. Phys. 2023, 25, 93027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kangoh, L. Renewable portfolio standards and electricity prices. Energy Econ. 2023, 126, 106959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sautner, Z.; Van, L.L.; Vilkov, G.; Zhang, R. Firm-level climate change exposure. J. Financ. 2023, 78, 1449–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Yang, K.; Li, Y. Climate risk and precautionary cash holdings: Evidence from Chinese listed companies. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1045827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, N.; Qiu, Q. Climate risk, environmental action and pricing of local government bond issuance. China Soft Sci. 2025, 1, 157–174. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Du, J.; Xu, X.; Yang, Y. Does climate risk affect the cost of equity capital?—Empirical evidence from text analysis of annual reports of Chinese listed companies. J. Financ. Rev. 2023, 15, 19–46+125. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G.; Wang, J.; Zhao, X. The impact of climate transition risks on enterprise default rates. Manag. Sci. 2023, 36, 144–159. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhai, P.; Lei, L.; Fan, Y. Climate policy uncertainty and enterprise bond financing costs. Syst. Eng. Theory Pract. 2024, 44, 3520–3536. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginglinger, E.; Moreau, Q. Climate risk and capital structure. Manag. Sci. 2023, 69, 7492–7516. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Chen, S.; Dai, L. How climate risk drives corporate green innovation: Evidence from China. Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 59, 104762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Li, W.; Li, J.; Wan, L. The effects of extreme climate events on green technology innovation in manufacturing enterprises. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2024, 25, 337–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 14001:2015/Amd 1:2024(en); Environmental Management Systems—Requirements with Guidance for Use—AMENDMENT 1: Climate Action Changes. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024.

- Amore, M.D.; Bennedsen, M. Corporate governance and green innovation. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2016, 75, 54–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, D.; Liu, H.; Yang, D.; Li, G. How does climate risk impact corporate green investment? Evidence from Chinese listed firms. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 396, 128040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zhang, Y. Enterprise digital transformation, strategic green innovation and enterprise environmental performance. Econ. Res. J. 2024, 59, 113–131. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Sun, L. Research on the impact of green innovation on climate transition risks. Hainan Financ. 2025, 7, 73–87. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Emanuela, B.; Frank, B.; Luca, G. How do firms cope with losses from extreme weather events? J. Corp. Financ. 2024, 84, 102508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L.; Shen, R.; Zhang, B. Does the media spotlight burn or spur innovation? Rev. Account. Stud. 2021, 26, 343–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, Y. Research on the promotion of green innovation by green credit policy. J. Manag. World 2021, 37, 173–188+11. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Cai, G.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Lu, R. Investor-listed company interaction and capital market resource allocation efficiency: Empirical evidence based on the cost of equity capital. J. Manag. World 2022, 8, 199–217. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Han, X.; Yue, B.; He, Z. Thriving in uncertainty: Examining the relationship between perceived environmental uncertainty and corporate eco-innovation through the lens of dynamic capabilities. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1196997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdu, A.J.; Tamayo, I.; Ruiz-Moreno, A. The moderating effect of environmental uncertainty on the relationship between real options and technological innovation in high-tech firms. Technovation 2012, 9–10, 579–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, W.; Ma, M.; Zhang, L. Path dependence in environment-related innovation: Evidence from listed firms in China. Appl. Econ 2025, 57, 8799–8816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TCFD. Use of Scenario Analysis in Disclosure of Climate-Related Risks and Opportunities. 2017. Available online: https://assets.bbhub.io/company/sites/60/2020/10/FINAL-TCFD-Technical-Supplement-062917.pdf (accessed on 24 June 2017).

- Stefano, G.; Maggiori, M.; Stroebel, J.; Weber, A. Climate change and long-run discount rates: Evidence from real estate. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2021, 34, 3527–3571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Paresh, K.N.; Iman, G.; Danny, H. Climate change and financial risk: Is there a role for central banks? Energy Econ. 2025, 144, 108320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulan, L.T. Real options, irreversible investment and firm uncertainty: New evidence from U.S. firms. Rev. Financ. Econ. 2005, 14, 255–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panousi, V.; Papanikolaou, D. Investment, idiosyncratic risk, and ownership. J. Financ. 2012, 67, 1113–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, L.; Wang, S. Investment, idiosyncratic risk, and growth options. J. Empir. Financ. 2021, 61, 118–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q. Uncertainty, Equity Incentive and Inefficient Investment. Account. Res. 2014, 3, 41–48. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.