Abstract

This study investigates the gendered nexus between climate change, food insecurity, and conflict in Plateau State, Nigeria. This region in north-central Nigeria is marked by recurring farmer–herder clashes and climate-induced environmental degradation. Drawing on qualitative methods, including interviews, gender-disaggregated focus groups, and key informant discussions, the research explores how climate variability and violent conflict interact to exacerbate household food insecurity. The methodology allows the capture of nuanced perspectives and lived experiences, particularly emphasizing the differentiated impacts on women and men. The findings reveal that irregular rainfall patterns, declining agricultural yields, and escalating violence have disrupted traditional farming systems and undermined rural livelihoods. The study also shows that women, though they are responsible for household food management, face disproportionate burdens due to restricted mobility, limited access to resources, and a heightened exposure to gender-based violence. Grounded in Conflict Theory, Frustration–Aggression Theory, and Feminist Political Ecology, the analysis shows how intersecting vulnerabilities, such as gender, age, and socioeconomic status, shape experiences of food insecurity and adaptation strategies. Women often find creative and local ways to cope with challenges, including seed preservation, rationing, and informal trade. However, systemic barriers continue to hinder sustainable progress. This study emphasized the need for integrating gender-sensitive interventions into policy frameworks, such as land tenure reforms, targeted agricultural support for women, and improved security measures, to effectively mitigate food insecurity and promote sustainable livelihoods, especially in conflict-affected regions.

1. Introduction

Climate change has shown potential for disrupting many aspects of human life, as it exposes nations to diverse challenges that range from economics to health and security. In vulnerable regions of the Global South, climate change and conflict are increasingly recognized as interrelated threats to agricultural productivity, household stability, and livelihood security [1] The unpredictability of rainfall and changes in temperature patterns directly impact agricultural yields and disrupt food systems. At the same time, conflicts destroy livelihoods and displace communities, undermining the ability of households to produce or access food [2]. These stressors often intersect. For example, in Nigeria, the changes in the climate, such as irregular rainfall in the south and desertification in the North, have intensified disputes among farmers and herdsmen over arable land and scarce water resources [3].

In the north-central region of Nigeria, where Plateau State lies, prolonged farmer–herder conflicts have intensified over recent decades, largely linked to population growth, increasing competition for scarce arable land and water resources, and deepening environmental pressures [4]. The competition over resources has contributed to the increasing reports of violent clashes between farmers and herders, resulting in numerous fatalities and ongoing insecurity [5,6].

Beyond the immediate violence, the cycle of attacks and threats forces farmers off their land, reduces planting and harvesting activities, and exacerbates hunger and malnutrition [7,8]. According to the World Food Programme, Nigeria’s north-central region now exhibits critical levels of severe food insecurity and malnutrition, marking the region as a major hotspot, demanding critical attention [9]. The conflict disrupts agricultural productivity and undermines local food systems, exacerbating hunger and malnutrition in affected households [6,10].

The centrality of agriculture to Plateau State’s economy cannot be overstated. Subsistence farming is one of the primary sources of livelihood for most residents, especially women, who manage small plots of land to produce food to feed their households. The increasing scarcity of arable land forces both farmers and herders to compete more intensely, with devastating consequences for food security. However, this is compounded by political manipulations and the state’s failure to play its role in adequate governance, particularly regarding land tenure and natural resource management [11].

The effect of climate change and conflict is not felt uniformly. In many developing countries, gender roles heavily influence how individuals experience and respond to these challenges. In Nigeria, women are often responsible for household food management, from growing and harvesting crops to preparing meals and caring for children, which makes them vital to food security at the household level [12,13]. Despite a growing body of research on food security in conflict zones, there has been less attention paid to the gendered dimensions of food insecurity in this context, especially at the household level [14]. Gender disparities in access to resources, decision-making power, and social mobility mean that men and women experience and respond to food insecurity differently [15,16]. During times of conflict, the responsibilities may become more burdensome as women face additional challenges, such as reduced access to land, restricted mobility, and increased workloads, especially in situations where the male household members are displaced or involved in the conflict and increased risk of gender-based violence [17,18].

Further research highlights the intersectionality of gender, agricultural labor, and food security. The State of Food Security and Nutrition report by FAO (2023) [16] report that women and men are more food insecure than men. The report revealed that 27.8% of women face moderate to severe food insecurity compared to 25.4% of men, stressing the need for more equitable food systems.

Critical to this study is the recognition that climate change and conflict do not occur in isolation. Instead, they intensify deep-rooted structural issues that have existed for many decades, such as population pressures, land degradation, insecure land tenure systems, and entrenched gender inequality, which have challenged rural livelihoods in Plateau State and other regions in Nigeria. These persisting issues are becoming more acute due to increasing climate impacts and regional conflict.

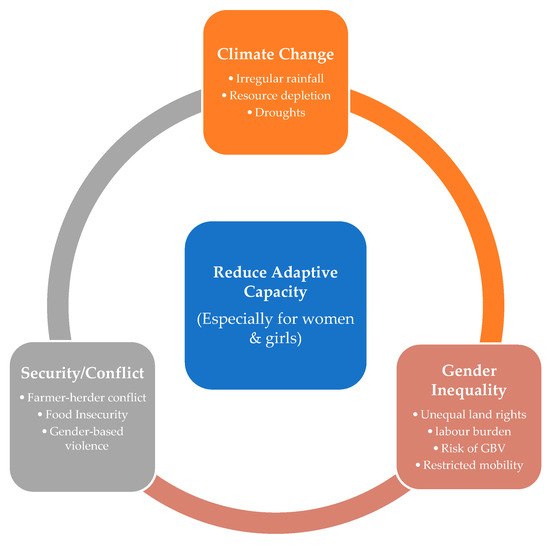

Against this backdrop, this study examines the gendered nexus between climate change and food security in the context of conflict. Figure 1 presents the conceptual framework underpinning this study. It illustrated the interrelated nature of climate change, gender inequality, and conflict in shaping food insecurity and adaptive capacity in Plateau State. By using Plateau State as a case study, we aim to gain a deeper understanding of how conflict dynamics influence the relationship between climate change and food security outcomes for women and men. While a growing body of literature has explored climate change as a driver and its implications for food security, fewer studies [14,19,20] have examined the gendered dimensions of these linked issues, particularly in the context of north-central Nigeria.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of the gender–climate–security nexus.

2. Theoretical Framing

This study is grounded in complementary theoretical perspectives—the resource scarcity nexus and a gender-informed analysis of vulnerability. Drawing on the first, the conflict theory, initially developed by Karl Marx and later expanded upon in the field of political economy, provides a foundation for understanding how structural inequalities and power dynamics contribute to social problems, including food insecurity [21,22]. In this context, the theory informs our understanding of how political instability, fueled by environmental degradation and ethno-religious tensions, disrupts local economies and food systems. In Plateau State, unequal power relations that govern access to land, agricultural and market inputs reflect broader patterns of resource control by dominant political and economic elites [21,22]. These dynamics disproportionately affect marginalized groups, including women, who face restricted access to productive resources, especially during times of conflict.

The decline in the availability and quality of resources, like fertile land and water, combined with factors like unequal access and rapid population growth, creates scarcity and heightened competition. Thus, existing conflicts have been driven by competition and scarcity, exposed by climate change and other environmental concerns, causing various groups to seek the advancement and protection of their livelihoods [10]. The Frustration–Aggression Theory (FAT) posits that when individuals or groups are prevented from achieving their goals, the resulting frustration can lead to aggressive behavior [23,24]. Developed originally to understand how individuals respond to societal pressures, the theory has since been extended to include broader socio-political contexts, such as post-colonial Africa conflict dynamics [25]. FAT offers a valuable lens for understanding the structural linkage between climate change, as an instigator of resource stress, and conflict, which impacts food security by disrupting agriculture [1]. This theory is particularly relevant in the context of the farmer–herder conflicts in northern Nigeria, where environmental degradation, including drought and desertification, has significantly constrained access to arable land and water resources [26,27,28].

In Plateau State, these environmental stressors have been exacerbated by the shortcomings in national food security policies and governance structures [29]. Recent evidence suggests that national strategies are skewed towards large-scale agricultural investments and export-oriented production, overlooking the critical needs of smallholder farmers and herders who rely heavily on local land and water resources for subsistence [30,31,32]. This neglect manifests in the inadequate infrastructure, weak extension services, and restricted access to inputs, which have been identified as barriers to smallholder productivity in Nigeria [16,33]. As a result, well-intentioned national programs fall short, failing to counter persistent household food insecurity in rural communities in Plateau State, leaving smallholder farmers vulnerable to cyclical insecurity.

While the Conflict Theory and FAT provide a general explanation for the rise in conflicts over resources, Feminist Political Ecology (FPE) and intersectionality theory further enriches this framework by highlighting how overlapping social identities, such as gender, ethnicity, class, and age, influence individuals’ experiences of oppression and privilege and unique experiences of marginalization [34]. FPE argues that access to and control over natural resources and exposure to environmental risks are deeply gendered, influencing men and women differently based on socially constructed roles and power relations [35,36]. In Plateau State, women are primary actors in food production, household nutrition, and resource collection. However, they have limited access to land ownership, resources, and decision-making processes due to patriarchal societal structures [37]. When conflicts arise from resource competition, women are disproportionately impacted through displacement, loss of livelihoods, and increased vulnerability to gender-based violence, which has severe repercussions on women’s health, mobility, and overall participation in the economy [38,39]. Gendered social norms that confine women to the domestic space reduce their involvement in household and community decision-making processes [40]. FPE highlights the undervalued contributions women make in agriculture and household food security, even though they bear the brunt of the consequences when food systems are disrupted by conflict.

Additionally, men and women adopt different coping strategies in times of crisis. Social identity also interacts to create unique experiences of marginalization. In many household contexts in this region, informal networks, small-scale gardening, and other low-resource activities are employed by women to manage food shortages, while men may migrate or engage in formal labor [41].

Approaching the analysis from an intersectional approach further enriches this framework by highlighting how overlapping social identities, such as ethnicity, class, and age, influence individuals’ experiences of oppression, privilege, and unique experiences of marginalization. In conflict-affected communities, a widowed man, a young unmarried man, and an elderly grandmother may all face distinct challenges and degrees of vulnerability even if they live in the same village in Plateau State [42]. By drawing on these theoretical frameworks, we provide both macro-level analyses of climate change and conflict and examine the micro-level differentiated impacts on food security within the population. This integrated approach helps ensure that the analysis goes beyond treating communities as homogenous units and highlights how climate change and conflict can have differentiated impacts.

3. Literature Review

Climate change poses significant threats to agriculture and food systems globally. In many regions, rising temperatures, changing perception patterns, and increasing extreme weather events undermine crop yields and destabilize food production [43,44,45]. Global assessments indicate that the impact on food security in poorer countries is disproportionately felt due to their lower adaptive capacity and a larger population share that depends on climate-sensitive livelihoods. In sub-Saharan Africa, warming trends and more erratic rainfall have been linked to reduced productivity for staple crops and increased food crises [46]. Nigeria is no exception, with many reports on climatic shocks evident nationwide. The rainfall has become more unpredictable and erratic in the southern regions, while in the northern regions, they face intensified droughts and desertification [47]. These climatic shifts have reduced the availability of arable land and water resources necessary for farming and herding, disrupting traditional livelihood practices [29].

In regions like Plateau State, conflict is another major driver of insecurity. It disrupts agricultural activities, market access, and resource allocation, all of which are crucial for maintaining food security [48]. Food security is defined by the FAO (1996, p. 3) [49] as “when all people, at all times, have physical, social, and economic access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food to meet their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life.” However, during times of conflict, all food dimensions are severely impacted. Conflict disrupts food production, restricts market access, destroys infrastructure, and displaces populations, making it hard to maintain stable food systems [50].

In Nigeria, political instability is presented through localized conflicts, such as the ongoing clash between farmers and herders, which is exacerbated by environmental degradation and resource scarcity [51]. When communities are engulfed in conflict, such as the farmer–herder clashes, it puts intense pressure on existing vulnerabilities, pushing smallholder farmers into a state of poverty and hunger by preventing them from accessing their farms or rearing livestock. In many instances, they are forced to flee their homes and abandon their fields, and local markets may collapse due to insecurity [52]. (The conflict drastically reduces local food production, as farmers are restricted from cultivating their lands due to security concerns, and herders face difficulties grazing their livestock, leading to reduced meat and dairy supply. There are also recorded attacks in the region, where assailants not only destroy farmland and property but also are perpetrators of gender-based violence [53].

Both climate and conflict have gendered implications for food security. Women in rural Nigeria make significant contributions to food production and family nutrition, yet they do not have the same access to resources and decision-making power as men. These barriers put a strain on their ability to respond to climate stressors. Women make up approximately 40% of the agricultural workforce in Nigeria, yet they own less than 5% of the farmland, a constraint that hinders their adaptive capacity [54]. However, women are typically responsible for food processing and preparation. Hence, during reduced harvest seasons, women find creative ways to ensure the household is fed, sometimes by skipping meals and reducing portion sizes, prioritizing children’s nutrition [55,56,57].

At the same time, conflict intensifies these challenges. During farmer–herder conflicts, women and children sometimes get caught in the crossfire, become displaced, or find themselves heading households in the absence of men. Security breakdowns constrain women’s ability, as the fear of attack may prevent them from freely moving to their farms or markets, which in turn translates to lower production and incomes. Additionally, gender-based violence tends to surge in conflict settings. Reports from Nigeria’s north-central region show that in times of conflict, sexual violence and other attacks on women are used as tactics of war or intimidation [53,58].

Meanwhile, men drawn into the conflict, either willingly or unwillingly, may lose their lives or suffer injury, reducing the availability of labor for the household. Though these factors illustrate the differentiated experience of the intersection of climate change and conflict, which is often disproportionate for women, it is also important to recognize women’s agency. The literature shows that women in Nigeria and similar conflict-affected, climate-vulnerable contexts adopt coping strategies, such as planting climate-resistant crops, conserving drought-tolerant seeds, or engaging in petty trade to sustain their families during periods of crisis [59]. Any analysis of the climate–conflict–food security nexus must account for the gendered role and responsibilities, acknowledging both the vulnerabilities and the contributions of women and men, respectively.

Ongoing initiatives aim to address the intersecting issues of climate change, food insecurity, and gender inequality in Nigeria. The Nigerian government released the Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC), which includes commitments to climate-smart agriculture and measures to support land management and mitigate land degradation [60]. Other notable programs, like the World Bank-assisted programs, Nigeria Erosion and Watershed Management Project (NEWMAP), and the Agro-Climatic Resilience in Semi-Arid Landscapes (ACReSAL), were set up to increase the implementation of sustainable land management to improve agricultural productivity and strengthen Nigeria’s long-term enabling environment for integrated climate-resilient landscape management [61,62].

In addition, organizations, like the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), have implemented the Value Chain Development Programme (VCDP) and the Climate Adaptation and Agribusiness Support Programme (CASP). The focus of the programs closely aligns with the Nigerian government’s Agricultural Transformation Agenda (ATA) and both incorporate gender-sensitive approaches to improve the livelihoods of smallholder farmers [63,64]. Though these initiatives exist, gaps remain in localized implementation and the extent to which gender-responsive solutions are prioritized. This study highlights the need to bolster these initiatives with targeted gender analyses and community-focused interventions.

4. Methods

4.1. Study Area

Plateau State, located in north-central Nigeria, was selected as the study area due to its historical significance in agriculture and its experiences with environmental changes and conflict. The state’s diverse topography, including highlands and plains, and its mix of ethnic and religious communities make it a representative case for examining the complex interplay between gender, environmental changes, and socio-political conflicts.

4.2. Research Design

The empirical research presented in this paper is based on qualitative research geared towards understanding the gendered dimensions of environmental change-induced conflict in Plateau State, northern Nigeria, with a focus on its impact on food security and women’s safety. The qualitative approach was chosen for this study as it allows for collecting rich, detailed data that captures the lived experiences, perceptions, and narratives of individuals directly impacted by climate change and conflict. A semi-structured interview format was the primary data collection method, allowing participants to express themselves freely. The principal investigator, alongside two translators with research training, conducted the interviews.

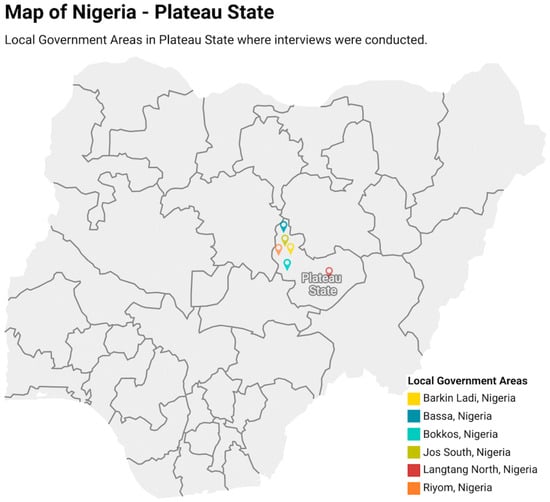

The research was conducted in six local government areas (LGAs) (Figure 2) from August 2023 to January 2024. The study employed a purposive sampling method to select participants who had lived in the areas for 20 years or more and had experienced the impacts of climate change and conflict. The participants’ demographics were considered to ensure diversity in age, gender, ethnicity, and socioeconomic background. There were 40 semi-structured interviews, six focus group discussion sessions, and key informant interviews as shown in Table 1. The semi-structured format of the interviews and focus group sessions allowed for unrestricted discussions, enabling participants to share their stories comfortably while providing information relevant to the study’s objectives. The interview guide probed their experiences with climate change and conflict, their impacts on farming, their coping strategies during food shortages, and any gender-specific challenges they faced.

Figure 2.

Map of Nigeria focusing on the local government areas where interviews were conducted.

Table 1.

Summary of qualitative data collected with smallholders.

The focus group discussions were held in groups of 6–8 participants, and four of the six sessions were disaggregated by gender to facilitate an open discussion in a comfortable setting. The topics discussed included any changes in gender roles due to conflict, community perceptions of climate change, conflict triggers and impact, and strategies for coping. Interviews lasted between 45 and 120 minutes and were conducted in English or one of the local languages (Hausa or Berom), depending on the participant’s preference. All interviews were audio recorded and securely stored. Interviews were transcribed, translated into English, and stored securely on a password-protected computer.

All participants provided informed consent, ensuring that they were fully aware of the study’s purpose, their right to withdraw at any time, and the confidentiality of their responses. The results are reported anonymously using pseudonyms. The research protocol was reviewed and approved by the University of Western’s ethics committee and had the support of community leaders in each village.

4.3. Data Analysis

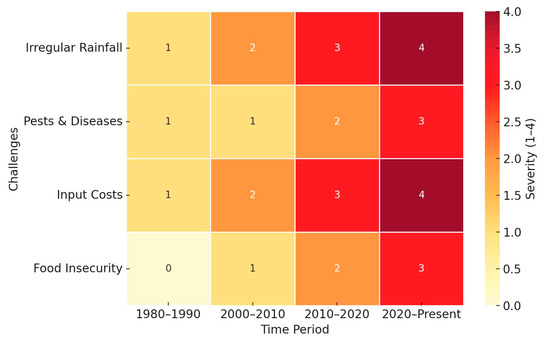

Data from interviews and focus group discussions were translated where necessary, transcribed verbatim and analyzed using thematic analysis in NVivo. This method involved reading and re-reading the transcribed interviews for a holistic view of the data, identifying themes, generating initial codes, and capturing essential elements related to the research question. Coding was both deductive (based on predefined themes, such as environmental changes, conflict causes, and gender impacts) and inductive (allowing new themes to emerge from the data), with codes collated into potential themes and sub-themes, and reviewed to ensure they accurately represented the data. Participants were asked to review and validate the interpretation and summary of their response to ensure accurate representation. Additionally, the research team conducted debriefing sessions to review the collected data and its interpretation, aiming to improve reliability and credibility. To complement the thematic analysis, a heatmap (Figure 3) was used to summarize respondent perceptions.

Figure 3.

Participants perceived changes in environmental conditions over time.

To supplement the field research, an exploratory review was conducted using secondary data. This process involved reviewing online news publications and government documents on the subject matter, consulting past and present research on conflict, environmental challenges, and gender in the Nigerian and northern Nigerian contexts. Triangulation of data sources was used to build a comprehensive picture and validate the findings.

5. Results

Participants noted the linked nature of these challenges in both the interviews and focus group sessions.

5.1. Household Food Security

There was a clear consensus that noticeable changes in the climate have occurred over the past decade, adversely impacting agriculture and decreasing food availability. Participants consistently reported that changing weather patterns, some cited irregular rainfall, long dry seasons, rising temperatures, and increased outbreaks of pests and diseases, have led to declining agricultural productivity. As shown in Figure 3, the severity of these issues has intensified over the past years, contributing to heightened food insecurity. Traditional farming practices passed down from generation to generation rely on predictable rainy seasons, which are no longer viable due to erratic precipitation. Crops often fail to mature and, in some cases, are affected by blights or other crop pests and diseases. Soil fertility has declined significantly, forcing many farmers to rely heavily on costly fertilizers and other inputs. For instance, a male farmer from the Jos South Local Government Area remarked, “in the past, we could tell when the rain would come and plan with that information. Now the rains come later or sometimes not at all, and our crops spoil in the fields.”

Another participant talked about the growing need to fertilize the soil, or the crops will fail to mature, and in some cases, they do not grow as well as they once did, reducing their nutritional value. There are reports of decreased yields due to abandoned and overused farmlands and destroyed crops. In the face of conflict, many households reported being unable to produce enough food to meet their needs. They often have to rely on borrowing food produce from neighbors or, in more dire situations, going without food for days and rationing where possible. Participants reported that they cannot safely tend to their crops when conflict erupts. Fertile and productive farmlands are often left uncultivated, even during peak farming seasons, which reduces crop yields and leads to household food shortages. One participant described the severe insecurity around farming, noting how armed Fulani herders disrupt their agricultural activities:

The Fulani herders invade our farms, drive us away, and sometimes even kill the farmers. They allow you to cultivate your farm, and then, when it is time for harvest, they invade our farms. We are insecure. When it is time for harvest, the sometimes Fulani herders ask the farmers to pay some amount of money before they can be allowed to harvest their crops. If there is peace and security for people to go and farm, people will not starve(R17, Female).

One focus group in Langtang South recalled that in 2022, the rain started almost a month late, causing them to replant millet and sorghum seeds multiple times. When the rain finally came, it was so intense that flooding washed away seedlings. Such erratic patterns have made traditional farming calendars less reliable. Nearly all (95%) respondents reported experiencing at least one major climate-related shock (such as drought, flood, or severe storm) every couple of years. In contrast, these were far rarer in the past. Beyond crops, climate stress has also impacted pasture availability for livestock, which has shrunk (pressuring herders and farmers alike), water sources have sometimes dried up seasonally, and pests (like armyworms) were said to be more prevalent in drought-stressed crops.

Over the last decade, environmental changes have had increasingly devastating consequences for households that rely on subsistence farming. Loss of crop yields reduces household food availability and limits income-generating opportunities for families that depend on trading surplus crops in local markets. The impacts of climate change have compounded existing challenges and increased pressure on scarce resources, leading to conflict and further destabilizing food systems. Even when food is available, prices are often so high that many families cannot afford basic necessities, or the quality has deteriorated, leading to nutritional deficiencies, especially among children and pregnant women.

5.2. Safety and Security Concerns

All participants expressed concerns about personal safety and security. The fear of attacks or harassment from rival groups impacted how they moved daily. It affected activities, including market days, fetching water, and tending to the farmlands, especially for women. Participants reported families were fleeing the area with few belongings, leaving standing crops untended and stored food behind. Some participants also reported changes in their movement patterns and, in some cases, slowing down their farm activities due to increased fear of being harassed while working on the farms. A female respondent described the impact of the conflict on their ability to work, stating that sometimes, “you can’t go to the farm. Even if your household can go to the farm, all of you and in the end, the herders will come to disturb you, and we are finding it very difficult, and we are afraid.” This constant fear forces farmers to adjust their daily routines to avoid conflict, sometimes leading them to abandon their farms entirely. As one male farmer describes, “then roads to our farms and security is also an issue, as I have already mentioned before. Security on the farm is not encouraging at all. You have the land, but you cannot go and plough it because your life is at stake.”

The interviews also revealed that women and children are vulnerable during such conflict. The breakdown of community structures leads to an increase in gender-based violence. Respondents across multiple local government areas reported an alleged increase in the rate of rape and other forms of violence, including physical assault and psychological abuse, particularly against women and girls. Women and girls from farming communities were allegedly raped by suspected herders while working on the farm or on their way to the farms. A female respondent mentioned changing farm times because maize grows tall, and if the women leave home too early or too late, they could get attacked by surprise. The respondent explained that they “cannot plant maize because it takes over and is high, so we go for other crops because it will be horrible when they [herdsmen] come. They will hide inside the crops, so we plant crops that are like on ground level like soya beans so you can easily see somebody passing or coming close to you.”

Women across the region have become increasingly vulnerable, as rape is used as a war tool, with women’s and girls’ bodies considered part of the battlefield (Ademola-Adelehin et al., 2018 [53]). Another male farmer described the danger women face when encountered alone on farms:

There is no security in the state. When the Fulani herders meet only women in the farm, they drive them away and xxx, so we have to go to the farm with them. When they overpower you, you just have to leave the farm for them. They are the ones in power, so they do what they like. When the Fulani herders invade your farm with their cattle, you end up not getting much from your harvest.(R45, Male)

Respondents also mentioned that the violence was not restricted to the farming communities, as women and girls from pastoral communities were also reportedly raped by suspected farmers.

5.3. Gendered Impacts and Coping Strategies

The interplay of climate change and conflict has revealed a shift in gender dynamics within the household. The findings show that women, particularly those heading households or in other vulnerable positions, bear a disproportionate share of the food security burden. Female-headed households were more likely than male-headed households to experience food insecurity and reported some periods where they could not meet their family’s food needs. Many female-headed households interviewed were either widowed women or women whose husbands had migrated in search of work. This leaves them with less available labor for on-farm work, less access to cash or credit, and as some described, smaller landholdings (sometimes only borrowed plots). A widowed respondent explained that her husband had been killed in a clash, and she struggled to cultivate the entire plot of land alone and could not afford to hire extra hands, leading to a smaller harvest.

In many conversations, older men expressed their hesitation to migrate out of their community, even when conflicts arose. The thoughts of the unknown and leaving behind farmlands passed down for generations were unfavorable. Younger men were more likely to move in search of work outside their community, often migrating to urban areas for stable employment. Several women also reported that during conflict peaks, they would mobilize to guard the farms and negotiate at checkpoints to bring food home. The increased responsibilities and emotional toll of conflict often left them feeling overwhelmed. These coping mechanisms highlight the significant emotional and logistical burdens placed on women as they strive to ensure household food security under increasingly challenging conditions.

The analysis also showed that women prioritize immediate household sustenance and often manage food scarcity through rationing and leveraging extended social networks. One respondent noted, “sometimes we manage the little we have and reserve little as seedlings for the next planting season. There is nothing we can do. Sometimes we ask for help from neighbors or relatives.” Men’s strategies involve external engagement. For example, there were many reports from women who reduced their food intake to support their children or borrowed money from relatives, and then came together in informal church groups to share resources during tough times. On the other hand, men more frequently reported selling off whatever they could for cash or travelling to cities for short-term labor opportunities on other farms or in the mines. Younger men were more likely to migrate to work as motorbike or taxi drivers or construction laborers to send money back home.

Despite these challenges, both men and women demonstrated resiliency and creativity. Some women emphasized the importance of prayer and hope in enduring hard times. Others stressed the need to diversify their skills and livelihoods. Youth respondents also expressed the need for skills training and new farming techniques. The findings show that gendered vulnerabilities exist at the nexus of climate change, conflict, and food security, but also the active role community members take to cope and adapt, even when support is limited.

5.4. Economic Impact on Households

Another central theme from the data is the loss resulting from the disruption to economic activity due to the conflict. The conflict is linked to the decline in farming activity and crop productivity in an area that’s also navigating the negative impacts of climate change. Participants consistently reported that they could no longer safely tend to their crops, and farmers reported abandoning their lands due to the threat of violence. Due to the high level of insecurity and fear, farmers are unable to go to their farms, resulting in the potential loss of yields for the farming season. Fields lie fallow, and harvest periods are missed, leading to a drastic decline in food production and income. Upon return, many found the crops were either spoiled, already harvested by a third party (as reported in Barkin Ladi LGA) or destroyed by cattle. A male respondent explained the adjustments made to mitigate these risks:

we cannot plant maize because it takes over and is high, so we go for other crops because it will be horrible when they [herdsmen] come. They will hide inside the crops, so we plant crops that are like on ground level like soya beans so you can easily see somebody passing or coming close to you.(R32, Male).

Some participants emphasized the conflict’s double-sided nature. Farmers are not the only impacted groups; herders are also affected by the destruction and theft of livestock, which is essential for their households as a source of income, food, and savings. Replacing livestock is costly and time-consuming, further exacerbating economic strain.

Beyond women’s direct involvement in food production, women also support and care for their families in times of need. Where possible, they are involved in market activities, such as selling farm produce, and thus also feel the economic impact of the conflict. Conflict disrupts market activities and causes insecurity in the region. As a result, participants observe that food prices have increased, making it difficult for families to afford basic necessities. Families heavily dependent on agriculture struggle to find alternative sources of income and sometimes fall into debt as they borrow to purchase food and other essentials. The economic strain is heightened in households where women are the primary caregivers and food providers. With the loss of income from selling their extra produce in the markets, women employ coping mechanisms, like taking on additional work, such as petty trading, casual labor, hair braiding, and other income-generating activities, to provide immediate support to their families. This increased workload adds to their physical and emotional burden. Conflict undermines food access by reducing the amount of land available for cultivation, weakening the local economy, and leading to financial insecurity, thereby perpetuating a cycle of poverty and hardship.

6. Discussion

The findings from the study support and improve our understanding of how climate change and conflict collectively exacerbate food insecurity in vulnerable communities from a gendered perspective. Consistent with the literature, the data support the argument that climate change functions as a “threat multiplier” in regions susceptible to conflict, exacerbating resource competition over land, water, and other resources and placing additional stress on livelihoods, which can trigger violence [1,65]. In Plateau State, farmers consistently noted increasingly irregular rainfall patterns, crop failures, and a decline in the availability of pastures, which intensify local tensions. These trends are also identified by Devereux and Edwards (2004) and Iorbo (2024) [43,45]. The results provide empirical support for Dollard et al.’s [23] Frustration–Aggression Theory, while also expanding the theory by highlighting the nuanced interaction between climate stressors and existing social inequalities.

One key insight in the study underscores the impact of conflict on pre-existing gender disparities. Women face heightened vulnerabilities, including increased exposure to gender-based violence, economic hardship, displacement, and disruption to social support networks. Restrictions on mobility and limited access to resources compound their vulnerabilities. The findings align with observations by Fjelde and von Uexkull [66] and Thurston et al. [67], who also found similar gendered vulnerabilities in conflict settings across sub-Saharan Africa. Furthermore, household dynamics shift during conflict. Women are compelled to assume greater responsibilities due to the absence of men. While these shifts can provide women with increased autonomy and authority within households, they also increase their workload and exacerbate emotional and physical stress, especially during periods of persistent insecurity, as noted in Raleigh’s (2010) [68] study in similar contexts.

Additionally, the study notes that female-headed households are more likely to experience food insecurity following climate shocks or conflict displacement. This finding aligns with broader research in Nigeria and beyond [20,69]. These studies have noted limitations in women’s access to land, credit, and decision-making authority, which significantly undermines their food security in times of crisis. Such restrictions heighten women’s financial hardships and increase the risk of exploitation and abuse, highlighting a critical gendered dimension of vulnerability.

The finding also indicates that women who lack secure land rights or support struggle to recover from a bad season or conflict-related loss. This underscores the need for comprehensive and gender-sensitive interventions that address the structural causes of conflict and inequality as part of resilience building, ultimately improving women’s protection and economic empowerment. This finding is similar to Tseer’s results [70], which showed that gender, age, and social capital played a significant role in determining farmers’ ability to diversify and adapt their livelihoods. Such analyses build on the feminist political ecology framework, highlighting the need for interventions that treat communities as diverse people and address the gendered power dynamics.

The study also highlights women’s agency and coping mechanisms. While women are often portrayed as victims in conflict and climate narratives, it is critical that we also see them as active agents, as revealed by the findings. Women are actively engaged in innovative coping mechanisms, such as planting climate-resilient crops, taking on new roles to support family survival, stepping in to fill gaps in the home, and leveraging informal networks. This finding aligns with emerging views on women’s resilience and roles in the face of climate adversity [71,72,73]. However, it is still evident that the risks women face in times of conflict are heightened, and their efforts are limited when confronted with large-scale crises, conflicts, and climate-related issues; external support is therefore critical. Policies and programs must build on Indigenous coping strategies, strengthening what already works, for example, providing drought-resistant crop varieties and supporting women’s groups in the community while filling gaps to ensure women’s improved access to aid and extension services.

The interaction between conflict-related insecurity and gender norms emerged as critical in the study. Women in male-headed households frequently lacked decision-making power, particularly regarding security and resource allocation, which sometimes led to their needs being overlooked in relief efforts, echoing similar observations by Ademola-Adelehin et al. (2018) [53]. Involving women in community peacebuilding or local climate adaptation planning leverages their knowledge and ensures solutions address their specific challenges. Similarly, engaging men in gender-inclusive approaches is critical for sustainability. This could include encouraging male community leaders to support women’s economic initiatives, which can help slowly shift norms that restrict women’s adaptive capacity.

The research further highlights the multidimensional nature of vulnerability, shaped by the interaction of gender, marital status, social norms, and economic status. Some farmers manage better than others due to their financial status, indicating that gender is one of several axes of inequality. Thus, targeted interventions must incorporate vulnerability assessments. Despite this multidimensionality, the persistent barriers women face necessitate gender-sensitive measures to address these issues.

Finally, the study acknowledges several limitations. The sample was limited to one state in Nigeria, potentially limiting generalizability beyond the region. A qualitative approach could also reflect the researcher’s subjectivity despite the checks and cross-validation. Future studies could address these limitations through quantitative research, comparative cross-national studies, or longitudinal analysis.

7. Conclusions

Plateau State is a case study in Nigeria that highlights the interplay between climate change and conflict, exacerbating food insecurity. The World Food Programme (WFP) reports have identified conflict in north-central Nigeria, including Plateau and climate shocks, as drivers of the country’s food crises [74]. The study notes three critical findings: (1) women’s resilience and adaptability to challenges, (2) gender-based violence is exacerbated by conflict and limits women’s adaptive capacity, and (3) the crucial role of climate variability on agricultural productivity.

The community-level case study brings a more local context to global statistics. More initiatives that simultaneously improve water and land management are needed to reduce resource competition, signal early warnings of conflict, and empower women and men with the tools and rights required to adapt to changing conditions. Recent frameworks, like the Climate Change, Agriculture, and Food Security’s gender–climate–security nexus, stress this integrated approach [20], advocating for meaningful gender analysis in climate security efforts for more efficient and equitable outcomes.

Addressing the gendered dimensions of food security necessitates that policymakers and development practitioners adopt a gender-sensitive approach. This requires recognizing and accounting for the specific needs of women and men in conflict-affected regions. The policy implications include gender-sensitive food assistance, secure land rights for women, and increased targeted agricultural extension services for women farmers. Interventions must prioritize increasing women’s access to agricultural resources, such as land, credit, labor, and credit-smart technologies, while addressing the unique barriers that hinder women from fully participating in decision-making processes within the household. These interventions can improve household resilience and response during conflict.

Building equitable resource-sharing agreements, strengthening conflict resolution mechanisms, and creating community-based programs that support both men and women in managing food production and security are essential. Integrating these strategies into broader agricultural and conflict management policies offers a good foundation for achieving sustainable food security. Future studies should continue to explore how community-based solutions can be better tailored to the needs of women and men, ensuring that interventions are truly inclusive and responsive to the diverse needs and complex realities of affected communities.

Author Contributions

T.O.I. was involved in conceptualization, methodology, analysis, visualization, and writing—review and editing. T.O.I. and I.L. were involved in validation, comments, and editing of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Ontario Graduate Scholarship (OGS) awarded by Western University.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the data is part of an ongoing doctoral study. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to the first author at tishola@uwo.ca.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Suleiman, M.B.; Salisu, K. Effects of climate change induced farmer-herder conflicts on socio-economic development of farmers in Giwa Local Government Area, Kaduna State, Nigeria. Dutse J. Pure Appl. Sci. 2022, 8, 129–138. [Google Scholar]

- Uyigue, E.; Agho, M. Coping with climate change and environmental degradation in the Niger Delta of southern Nigeria. In Community Research and Development Centre Nigeria; Community Research and Development Centre: Benin, Nigeria, 2007; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Adamu, A.; Ben, A. Migration and violent conflict in divided societies: Non-Boko Haram violence against Christians in the Middle Belt region of Nigeria. In Nigeria Conflict Security Analysis Network (NCSAN) Working Paper No. 1; World Watch Research, Open Doors International: Harderwijk, The Netherlands, 2015; Available online: https://opendoorsanalytical.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/Migration-and-Violent-Conflict-in-Divided-Societies-March-2015.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Setrana, M.B.; Adzande, P. Farmer-pastoralist interactions and resource-based conflicts in Africa: Drivers, actors, and pathways to conflict transformation and peacebuilding. Afr. Stud. Rev. 2022, 65, 399–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjaminsen, T.A.; Ba, B. Fulani-dogon killings in Mali: Farmer-herder conflicts as insurgency and counterinsurgency. Afr. Secur. 2021, 14, 4–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Crisis Group. Herders Against Farmers: Nigeria’s Expanding Deadly Conflict. Africa Report No. 252. 2017. Available online: https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/west-africa/nigeria/252-herders-against-farmers-nigerias-expanding-deadly-conflict (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Higazi, A. The Jos Crisis: A Recurrent Nigerian Tragedy; Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung: Wuse II Abuja, Nigeria, 2011; Available online: https://library.fes.de/pdf-files/bueros/nigeria/07812.pdf (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Nnaji, A.; Ratna, N.N.; Renwick, A. Gendered access to land and household food insecurity: Evidence from Nigeria. Agric. Resour. Econ. Rev. 2022, 51, 45–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO; IFAD; UNICEF; WFP; WHO. The State of Food Security Nutrition in the World 2023 Urbanization Agrifood Systems Transformation Healthy Diets Across the Rural–Urban Continuum Rome; F.A.O.: Rome, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoli, A.C.; Atelhe, G.A. Nomads Against Natives: A Political Ecology of Herders/Farmers Conflicts in Nasarawa State, Nigeria. Am. Int. J. Contemp. Res. 2014, 4, 76–88. [Google Scholar]

- Olayoku, P.A. Trends and Patterns of Cattle Grazing and Rural Violence in Nigeria (2006–2014). Doctoral Dissertation, IFRA-Nigeria, Ibadan, Nigeria, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Meinzen-Dick, R.; Kovarik, C.; Quisumbing, A.R. Gender and sustainability. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2014, 39, 29–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ene-Obong, H.N.; Onuoha, N.O.; Eme, P.E. Gender roles, family relationships, and household food and nutrition security in Ohafia matrilineal society in Nigeria. Matern. Child Nutr. 2017, 13 (Suppl. 3), e12506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njuki, J.; Eissler, S.; Malapit, H.; Meinzen-Dick, R.; Bryan, E.; Quisumbing, A. A review of evidence on gender equality, women’s empowerment, and food systems. In Science and Innovations for Food Systems Transformation; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; Volume 165. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal, B. Bargaining and gender relations: Within and beyond the household. Fem. Econ. 1997, 3, 1–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Gender Emergencies and Resilience Building; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2021; Available online: https://www.fao.org/gender/learning-center/thematic-areas/gender-and-emergencies-and-resilience-building/3/en?tabInx=0&utm_source (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- Fruttero, A.; Halim, D.Z.; Broccolini, C.; Dantas Pereira Coelho, B.; Gninafon, H.M.A.; Muller, N. Gendered Impacts of Climate Change: Evidence from Weather Shocks. In Policy Research Working Paper Series; 2023; p. 10442. Available online: https://wrd.unwomen.org/practice/resources/gendered-impacts-climate-change-evidence-weather-shocks (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Buvinic, M.; Das Gupta, M.; Casabonne, U.; Verwimp, P. Violent conflict and gender inequality: An overview. World Bank Res. Obs. 2013, 28, 110–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayanlade, A.; Oluwatimilehin, I.A.; Ayanlade, O.S.; Adeyeye, O.; Abatemi-Usman, S.A. Gendered vulnerabilities to climate change and farmers’ adaptation responses in Kwara and Nassarawa States, Nigeria. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caroli, G.; Tavenner, K.; Huyer, S.; Sarzana, C.; Belli, A.; Elias, M.; Pacillo, G.; Läderach, P. The Gender-ClimateSecurity Nexus: Conceptual Framework, CGIAR Portfolio Review, and Recommendations towards an Agenda for One CGIAR; Position Paper No. 2022/1; CGIAR FOCUS Climate Security, 2022; Available online: https://ccafs.cgiar.org/resources/publications/gender-climate-security-nexus-conceptual-framework-cgiar-portfolio (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Marx, K.; Engels, F. The communist manifesto. In Ideals and Ideologies; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 243–255. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, M. Politics as vocation. In From Max Weber: Essays in Sociology; Gerth, H.H., Mills, C.W., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1946; pp. 77–128. [Google Scholar]

- Dollard, J.; Doob, L.; Miller, N.; Mowrer, O.H.; Sears, R. Frustration and Aggression; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1939. [Google Scholar]

- Buss, A.H. The Psychology of Aggression; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Mamdani, M. Beyond Settler and Native as Political Identities: Overcoming the Political Legacy Colonialism; Ozo-Eson, P., Ukiwo, U., Eds.; Ideology and African Development, CASS & AFRIGOV, 2001; Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2696665 (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Udoh, O.D.; Aforijiku, O.E.; Abasilim, U.D.; Osimen, G.U. Climate change and migratory patterns of Fulani Herdsmen in Nigeria. Int. J. Clim. Change Strateg. Manag. 2025; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar]

- Yahaya, I.I.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Inuwa, A.Y.; Zhao, Y.; You, Y.; Basiru, H.A.; Ochege, F.U.; Na, Z.; Ogbue, C.P.; et al. Assessing desertification vulnerability and mitigation strategies in northern Nigeria: A comprehensive approach. Heliyon 2024, 10, e31167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwilo, P.C.; Olayinka, D.N.; Okolie, C.J.; Emmanuel, E.I.; Orji, M.J.; Daramola, O.E. Impacts of land cover changes on desertification in northern Nigeria and implications on the Lake Chad Basin. J. Arid Environ. 2020, 181, 104190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odoh, S.I.; Chilaka, F.C. Climate change and conflict in Nigeria: A theoretical and empirical examination of the worsening incidence of conflict between Fulani herdsmen and farmers in Northern Nigeria. Arab. J. Bus. Manag. Rev. 2012, 2, 110–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babatunde, A.O.; Ibnouf, F.O. The Dynamics of Herder-Farmer Conflicts in Plateau State, Nigeria, and Central Darfur State, Sudan. Afr. Stud. Rev. 2024, 67, 321–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oderinde, F.O.; Akano, O.I.; Adesina, F.A.; Omotayo, A.O. Trends in climate, socioeconomic indices and food security in Nigeria: Current realities and challenges ahead. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 6, 940858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adejumo, A.O. Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security in Ogun State, Nigeria: An Analysis of Policy and Institutional Framework; Greenline Publishers: Abeokuta, Nigeria, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Atobatele, A.J.; Suleiman Adamu, I.; Oladoyin, A.M.; Olaoye, O.P.; Dele-dada, M. X-ray of agricultural development programme and food security in Nigeria. Agric. Food Secur. 2025, 14, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crenshaw, K. Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. In Feminist Legal Theories; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; pp. 23–51. [Google Scholar]

- Rocheleau, D.; Thomas-Slayter, B.; Wangari, E. Feminist Political Ecology: Global Issues and Local Experience; Routledge: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Dankelman, I.; Jansen, W. Gender, environment, and climate change: Understanding the linkages. In Gender and Climate Change: An Introduction; Routledge: London, UK, 2010; pp. 37–62. [Google Scholar]

- Olaniyan, A.; Francis, M.; Okeke-Uzodike, U. The cattle are “Ghanaians” but the herders are strangers: Farmer-herder conflicts, expulsion policy and pastoralist question in Agogo, Ghana. Afr. Stud. Q. 2015, 15, 53–67. [Google Scholar]

- Usman, A.; Amodu, N.O. Gender and the environment: Impacts of pastoral conflicts on women’s health and well-being in Plateau State, Nigeria. Women’s Health Urban Life 2018, 17, 34–52. [Google Scholar]

- Nightingale, A. Bounding difference: Intersectionality and the material production of gender, caste, class and environment in Nepal. Geoforum 2011, 42, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nightingale, A.J. The Nature of Gender: Work, Gender, and Environment. Environ. Plan. D Soc. Space 2006, 24, 165–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriesberg, L. Constructive Conflicts: From Escalation to Resolution; Rowman & Littlefield, 2003; Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2003-04146-000 (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Kaag, M. Gender and Development in Muslim Societies: The Case of Northern Nigeria; Brill, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Devereux, S.; Edwards, J. Climate Change and Food Security. IDS Bull. 2004, 35, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egeru, A.; Wasonga, O.; Kyagulanyi, J.; Majaliwa, G.M.; MacOpiyo, L.; Mburu, J. Spatio-temporal dynamics of forage and land cover changes in Karamoja sub-region, Uganda. Pastoralism 2014, 4, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iorbo, R. Herdsmen-farmer conflict-induced internal displacement, humanitarian crisis, and effects on development in Benue state–Nigeria. In Polycrisis and Economic Development in the Global South; Routledge: London, UK, 2024; pp. 69–80. [Google Scholar]

- Trisos, C.H.; Adelekan, I.O.; Totin, E.; Ayanlade, A.; Efitre, J.; Gemeda, A.; Kalaba, K.; Lennard, C.; Masao, C.; Mgaya, Y.; et al. 2022: Africa. In Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability; Pörtner, H.-O., Roberts, D.C., Tignor, M., Poloczanska, E.S., Mintenbeck, K., Alegría, A., Craig, M., Langsdorf, S., Löschke, S., Möller, V., et al., Eds.; Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 1285–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortimore, M.; Anderson, S.; Cotula, L.; Davies, J.; Faccer, K.; Hesse, C.; Morton, J.; Nyangena, W.; Skinner, J.; Wolfangel, C. Dryland Opportunies: A New Paradigm for People, Ecosystems and Development; International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), 2009; Available online: https://www.iied.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/migrate/G02572.pdf (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Gwanshak, J.Y.; Wuyep, S.Z. A survey of the impact of rural insecurity-driven displacement on agricultural practices and food security in plateau state, Nigeria. Multidiscip. Sci. J. 2024, 12, 2321–2338. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture (FAO). Rome Declaration on World Food Security and World Food Summit Plan of Action. Available online: https://ecfs.msu.ru/Low_documents/International/Rome%20Declaration%20on%20World%20Food%20Security%201996.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Devereux, S. The impact of droughts and floods on food security and policy options to alleviate negative effects. Agric. Econ. 2007, 37, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamu, A.; Ben, A. Nigeria: Benue State Under the Shadow of “Herdsmen Terrorism” (2014–2016); World Watch Research Report; 2017. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/322759537_Nigeria_Benue_State_under_the_shadow_of_herdsmen_terrorism_2014-2016_Africa_Conflict_and_Security_Analysis_Network_ACSAN_Formerly_NCSAN-Nigeria_Conflict_and_Security_Analysis_Network?channel=doi&linkId=5a6ef7e1aca2722c947f7bca&showFulltext=true (accessed on 23 June 2024).

- Adebayo, O.O.; Olaniyi, O.A. Factors associated with pastoral and crop farmers conflict in derived Savannah Zone of Oyo State, Nigeria. J. Hum. Ecol. 2008, 23, 71–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ademola-Adelehin, B.I.; Achakpa, P.; Suleiman, J.; Donli, P.; Osakwe, B. The Impact of Farmer-Herder Conflict on Women in Adamawa, Gombe and Plateau States of Nigeria. In Policy Brief; Search for Common Ground: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Gender Data Portal: Nigeria—Labor and Land Ownership. 2024. Available online: https://genderdata.worldbank.org/ (accessed on 22 June 2025).

- Falola, A.; Olanrewaju, A.S.; Mukaila, R.; Olorunseye, H.B.; Obalola, T.O. Assessing Households’ Food Insecurity and Coping Strategies in Seme, Nigeria: A Borderland Community in Economic Transition. J. Hunger. Environ. Nutr. 2025, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilori, T.; Christofides, N.; Baldwin-Ragaven, L. The relationship between food insecurity, purchasing patterns and perceptions of the food environment in urban slums in Ibadan, Nigeria. BMC Nutr. 2024, 10, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anugwa, I.Q.; Agwu, A.E.; Suvedi, M.; Babu, S. Gender-specific livelihood strategies for coping with climate change-induced food insecurity in Southeast Nigeria. Food Secur. 2020, 12, 1065–1084ez. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demetriades, J.; Esplen, E. The gender dimensions of poverty and climate change adaptation. IDS Bull. 2008, 39, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resurrección, B.P. Gender, climate change and disasters: Vulnerabilities, responses, and imagining a more caring and better world. In Proceedings of the Background Paper, EGM/EV/BP. 2, UN Women Expert Group Meeting; Queens University: Kingston, ON, Canada, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Ministry of Environment, Abuja. Nigeria’s Nationally Determined Contribution. 2021. Available online: https://climatechange.gov.ng/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/NDC_File-Amended-_11222.pdf (accessed on 22 June 2025).

- World Bank. Nigeria Erosion and Watershed Management Project (NEWMAP) (Project P164082)–Additional Financing. 2022. Available online: https://projects.worldbank.org/en/projects-operations/project-detail/P164082 (accessed on 22 June 2025).

- World Bank. Agro-Climatic Resilience in Semi-Arid Landscapes (ACReSAL) (Project P175237). 2024. Available online: https://projects.worldbank.org/en/projects-operations/project-detail/P175237 (accessed on 22 June 2025).

- International Fund for Agricultural Development Nigeria—Climate Change Adaptation and Agribusiness Support Programme in the Savannah Belt. 2022. Available online: https://www.ifad.org/documents/48415603/49457717/Nigeria+1100001692+CASP+Project+Completion+Report.pdf/b534e36b-206e-f572-e873-1762dfe9c2d3?t=1726606669987 (accessed on 22 June 2025).

- International Fund for Agricultural Development. Nigeria—Value Chain Development Programme. 2024. Available online: https://www.ifad.org/documents/48415603/50527856/NGA_1100001594_SUPERVISION_REPORT_NOV_2024_0024-811606050-2136.pdf/2e8faa06-41c1-58aa-9587-9f1dcd20726f?t=1736953306476 (accessed on 22 June 2025).

- Adigun, O.W. A Critical Analysis of the Relationship Between Climate Change, Land Disputes, and the Patterns of Farmers/Herdsmen’s Conflicts in Nigeria. Can. Soc. Sci. 2019, 15, 76–89. [Google Scholar]

- Fjelde, H.; von Uexkull, N. Rainfall anomalies, vulnerability and communal conflict in Sub-Saharan Africa. Political Geogr. 2012, 31, 444–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurston, A.M.; Stöckl, H.; Ranganathan, M. Natural hazards, disasters and violence against women and girls: A global mixed-methods systematic review. BMJ Glob. Health 2021, 6, e004377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raleigh, C. Political marginalization, climate change, and conflict in African Sahel states. Int. Stud. Rev. 2010, 12, 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, E.R.; Thompson, M.C. Gender and climate change adaptation in agrarian settings. Geoforum 2014, 53, 46–56. [Google Scholar]

- Tseer, T. Surviving violent conflicts and climate variability: An intersectional analysis of differentiated access to diversification resources among smallholder farmers in Kuka. Heliyon 2023, 9, e22190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smyth, I.; Sweetman, C. Introduction: Gender and Resilience. Gend. Dev. 2015, 23, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, K.; Najjar, D.; Bryan, E. Women’s Resilience and Participation in Climate Governance in the Agri-Food Sector: A Strategic Review of Public Policies; International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA): Beirut, Lebanon, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, P.; Tabe, T.; Martin, T. The role of women in community resilience to climate change: A case study of an Indigenous Fijian community. Women’s Stud. Int. Forum 2022, 90, 102550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO; European Union; CIRAD. Food Systems Profile—Nigeria. In Catalysing the Sustainable and Inclusive Transformation of Food Systems; FAO: Rome, Italy; European Union: Brussels, Belgium; CIRAD: Montpellier, France, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).