Abstract

Poverty is a complex global issue, closely linked to economic and social inequalities. It encompasses not only a lack of financial resources but also disparities in access to education, healthcare, employment, and social participation. In alignment with the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals—specifically SDGs 3 (Good Health and Well-being), 4 (Quality Education), and 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth)—this study investigates the relationship between poverty and a set of socioeconomic indicators across Italy’s 20 regions. To explore how poverty levels respond to different predictors, we apply an identity spline transformation to simulate controlled changes in the poverty indicator. The resulting scenarios are analyzed using partial least squares regression, enabling the identification of the most influential variables. The findings offer insights into regional disparities and contribute to evidence-based strategies aimed at reducing poverty and promoting inclusive, sustainable development.

1. Introduction

Poverty remains one of the most pervasive and complex issues affecting societies worldwide. Closely intertwined with economic and social inequalities, poverty reflects not only a lack of financial resources but also disparities in access to education, healthcare, employment, and social participation. Reducing these inequalities is among the most urgent challenges for achieving sustainable and inclusive development (Xhafaj & Nurja, 2014). As noted by Lanza (2015), economic inequality can be influenced by income and wealth disparities across different social groups, while social inequality—highlighted by Neckerman (2004)—manifests in unequal access to rights, services, and opportunities based on factors such as gender, ethnicity, or physical ability. Understanding the root causes and dimensions of poverty is essential for informing effective policy responses aimed at promoting equity, social cohesion, and long-term stability.

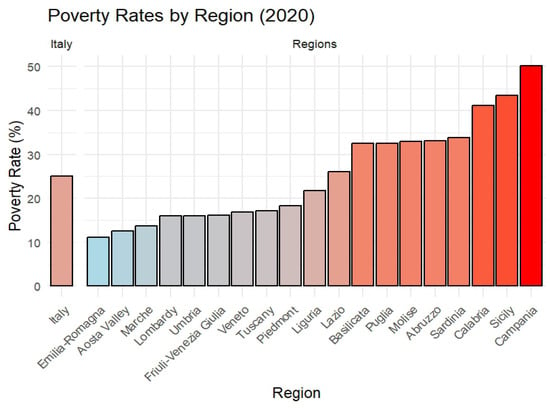

In Italy, the poverty risk indicator, calculated by ISTAT, measures the share of individuals living in households with an equivalent net income below the poverty risk threshold, defined as 60% of the median of the national distribution of the net income. In 2020, 20% of people residing in Italy were at risk of poverty (based on the previous year’s income), a percentage consistent with that of the preceding year (20.1% in 2019), despite the outbreak of the pandemic. Additionally, 5.6% of people were in conditions of severe material deprivation, and 11.7% were living in households with low work intensity. The composite indicator, based on these two components and on the risk of poverty, i.e., the share of the population at risk of poverty or social exclusion, indicates that 25.3% of the population was at risk of poverty or social exclusion, similar to 2019 (25.6%). This indicator is part of Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 10. The risk of poverty or social exclusion varies significantly between regions, displaying a clear North-South gradient (Figure 1). Several central-southern regions (Lazio, Abruzzo, Molise, Campania, Puglia, Basilicata, Calabria, Sicily, and Sardinia) have a percentage greater than 25.3%, whilest the north-central regions (Piedmont, Valle d’Aosta, Liguria, Lombardy, Trentino-Alto Adige, Veneto, Friuli-Venezia Giulia, Emilia-Romagna, Tuscany, Umbria, Marche) have percentages below 25.3%. In particular, among the north-central regions, only 11% of the resident population in Emilia-Romagna was at risk of poverty or social exclusion, whereas in Campania, among the central-southern regions, half of the population faced this risk (50.2%). The risk of poverty or social exclusion remained almost stable between 2019 and 2020 but remained high compared to other European countries, placing Italy near the bottom of the EU rankings. Over the past decade, regional disparities in poverty have persisted, showing no significant convergence between northern and southern Italy (Ciommi et al., 2021).

Figure 1.

The risk of poverty in Italian regions.

Socio-economic inequalities are shaped by a wide range of interrelated factors, including income, education, employment status, family structure, gender, ethnicity, and access to quality healthcare (Mackenbach et al., 2002; Timmis et al., 2022; Camminatiello et al., 2023). Previous research has shown that economically less developed countries tend to exhibit higher rates of NEET (Not in Education, Employment, or Training) individuals (Caroleo et al., 2020), whereas countries with more structured school-to-work transition systems experience lower NEET rates. Addressing these inequalities requires comprehensive and targeted interventions at the social, economic, and political levels (Schmidt et al., 2015). Moreover, several studies that analyze panel data report a negative correlation between economic growth and poverty (Garcés-Urzainqui, 2024; Marrero & Servén, 2022; Dollar et al., 2016).

In this study, we analyze the risk of poverty and social exclusion in Italy—hereafter referred to simply as poverty—and identify the socio-economic indicators most strongly associated with Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 3, 4, and 8, using data from the 20 Italian regions. When examining regional poverty levels, which are shaped by heterogeneous predictors, the research question can be framed around how poverty can be alleviated in the most disadvantaged areas and which variables exert the greatest influence in specific contexts. From a policy perspective, the short- to medium-term objective may consist in reducing the number of regions affected by poverty, a goal that can be pursued by perturbing the response variable through the use of an identity spline (Durand et al., 2025), which allows for the exploration of different poverty scenarios. Naturally, scenarios of varying complexities might be considered. Thus, the primary approach is to transform the response variable, poverty, with the aim of reducing poverty in specific areas. Furthermore, the analysis aims to identify the most influential predictors contributing to the attainment of this objective. To identify the most influential socio-economic indicators affecting poverty, this study employs partial least squares (PLS) regression (Wold, 1966). Unlike logit models (Xhafaj & Nurja, 2014) or quantile regression (Piketty & Saez, 2003; Lynch et al., 2004), PLS effectively addresses issues of multicollinearity among predictor variables, making it particularly suitable for analysing complex socio-economic phenomena.

In Section 2, we introduce the identity spline and briefly discuss the PLS regression model. Section 3 presents an application using poverty-related data from the Sustainable Development Goals of Agenda 2030 for Italy, suggesting potential avenues for poverty alleviation. Section 3.3 compares three different scenarios related to poverty reduction in specific regions of Italy. Finally, Section 4 provides a final discussion.

2. Materials and Methods

This study makes use of an identity spline for transforming the response variable; this spline is designed to simulate controlled changes in the response variable within a partial least squares regression model.

2.1. Identity Spline

Before introducing the identity spline function, we first briefly define splines and B-splines.

A spline function s for a continuous variable y on the open interval is constructed from piecewise polynomials of degree d (or order ). These polynomials are joined at K points, , known as knots, with continuity constraints determined by the knot multiplicity, which ranges from 1 to m and indicates how many knots coincide at the same location. The functional space of splines has dimension , and the most commonly used basis functions for splines are the B-splines (Shumaker, 1981). The user specifies K interior knots, which, together with the polynomial degree, act as tuning parameters. A spline function s is then expressed as linear combination of a set of B-splines:

where denotes the set of B-spline basis functions. For simplicity, a spline can be written as . In regression settings, the weight vector is typically estimated. However, when using specific functions, such as the identity spline, , it can also be modified by the users (Durand et al., 2025). The identity spline (Marsden, 1970), is defined by nodal weights , also known as Greville points (Greville, 1967) in approximation theory. Regardless of or the knot multiplicities, the identity spline satisfies

where

In any regression model involving a functional transformation of the response y, it is crucial to control the transformation to ensure both a good fit and predictive accuracy. By introducing small additive modifications to the nodal coefficients (), one can dynamically adjust the response y, while preserving both goodness of fit and predictive performance. The properties of such variations around the identity spline—through the choice of degree, number, location, and knot multiplicity—allow for precise local control of these adjustments.

Here, a new response, denoted , is defined as an alteration of the observed response y via a spline transformation, expressed as a deviation from the identity spline and controlled by the parameter . When , the transformation reduces to (Durand et al., 2025). Such an easy exploration of new scenarios, based on local or global, continuous or discontinuous, functional changes of the observed response, plays a strategic role, particularly for policymakers.

2.2. Partial Least Squares Regression

Partial least squares (PLS) is a statistical regression technique developed to identify linear relationships between one or more response variables and one or more predictor variables. PLS regression represents a non-parametric modeling approach which, unlike classical econometric models, does not rely on a priori assumptions regarding the distribution of the error terms. Consequently, neither the response variables nor the errors are assumed to follow a specific probability distribution, and traditional inferential tests can be applied through resampling techniques such as bootstrap procedures, as employed in this paper. This method is particularly advantageous when the set of predictors is large and characterised by multicollinearity or strong intercorrelations, and when the sample size is small relative to the number of variables (Wold, 1966, 1975, 1985).

PLS operates by constructing A centered and uncorrelated latent variables, , known as PLS components, which are linear combinations of the original p predictors, . These components are designed to maximize their covariance with the response variable. The number A of retained components is usually determined by cross-validation or generalized cross-validation (Lombardo et al., 2009). The basic form of the PLS regression model for estimating a response variable can be expressed as follows:

where is the coefficient associated with the jth predictor, which depends on the number A of retained PLS components. When A equals the rank of the predictor matrix , then PLS coincides with the ordinary least squares (OLS) regression.

A generalization of PLS for situations in which non-linear relationships exist between the response and predictor variables is provided by the partial least-squares splines (PLSS) model (Durand & Sabatier, 1997; Durand, 2001). This model extends PLS to the non-linear case by using B-splines as bases to transform the predictors.

In this study, we apply a linear PLS model, as the relationships between the response and the predictors appear to be linear.

3. Results

3.1. SDG-Based Variable Selection

Before using the linear PLS regression model to identify the most relevant predictors of poverty and its scenarios (see Section 3.2), the priority is to select the SDG indicators that will be used to predict poverty in Italy. This will be followed by the identification of three poverty scenarios, generated using three different identity spline transformations of poverty (see Section 3.2).

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are a set of 17 goals adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in 2015, aimed at promoting sustainable development, eradicating poverty, protecting the planet, and ensuring prosperity for all. Several studies have analyzed the SDGs in different ways. For instance, Alaimo and Maggino (2020) focus on composite indicators for SDGs 1–3 at the regional level in Italy, providing methodological insights useful for monitoring progress toward the 2030 Agenda. Similarly, D’Adamo et al. (2025) develop a multi-criteria decision analysis framework for regional assessment of the SDGs in Italy, using 61 indicators that cover social, economic, and environmental domains.

In this context, we focus on Italy’s Strategy for the SDGs (see the SDGs 2021 Report: Statistical Information for the 2030 Agenda in Italy, published by ISTAT), which assesses sustainable development across the 20 Italian regions.

We investigate poverty—a key aspect of SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities)—in conjunction with indicators collected under SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being), SDG 4 (Quality Education), and SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth). Accordingly, our analysis focuses on examining the dependence of poverty on several socio-economic indicators aligned with SDGs 3, 4, and 8, gathered from the 20 regions of Italy. These include 49 predictor variables described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Description of the 49 indicators of the SDGs 3, 4 and 8. The most relevant predictors in Scenarios 1, 2, and 3 are highlighted in bold.

It should be noted that only those indicators for which data were available across all Italian regions were considered, with 2019 selected as the reference year. A brief description of SDGs 3, 4, and 8 is provided in Table 1 and below:

- –

- SDG 3: “Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages” (HWB), described by 12 indicators aimed at measuring progress towards this goal.

- –

- SDG 4: “Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all” (QEdu), explained by 27 indicators.

- –

- SDG 8: “Promote sustained, inclusive, and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment, and decent work for all, and enhance productive capacity for the least developed regions” (WG), related to 10 indicators.

3.2. Poverty in Italy: Three Scenarios

We consider three scenarios corresponding to simulated controlled changes in poverty, generated using the identity spline described in Section 2. The choice of the -perturbation applied to the nodal coefficients of the identity spline depends on the specific target of the analysis—for example, in our poverty study, it is determined by the number of impoverished regions that we aim to move below the national average poverty threshold. Accordingly, different values of the -perturbation were adopted for the three hypothetical poverty scenarios.

3.2.1. Scenario 1

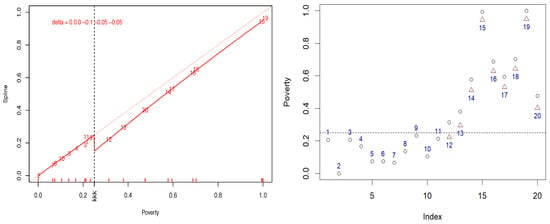

First, poverty—with observations ranging from 0 to 1—is transformed using second-degree B-splines with a multiple knot at 0.25 (the average poverty level in Italy) and a multiplicity of 3. According to B-splines smoothness property, a knot of multiplicity 3 at the poverty threshold 0.25 introduces a discontinuity in the six-dimensional spline functions. The nodal coefficients are perturbed by as indicated in the top-left corner of Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Description of Scenario 1. In the left plot, the identity spline (red dotted line) of degree 2 has one knot at the poverty average value of 0.25, with a multiplicity of 3, marked by overturned ‘k’ letters on the horizontal axis, leading to a discontinuity at that point. In the right plot, poverty values are represented by (with the nine regions of high poverty highlighted in red). After the delta perturbations ( = 0, 0, 0, −0.1, −0.05, −0.05), the new values marked with correspond to a decrease of the original values. Observe that the delta-perturbation moves Lazio (12) below the national average poverty threshold.

On the right side of Figure 2, which displays both real and simulated poverty values, only the nine regions above the national poverty average have their values modified. Consequently, the nodal coefficients of the identity spline are modified by these delta values.

This adjustment results in a reduction in poverty in central-southern regions (Lazio = 12, Abruzzo = 13, Molise = 14, Campania = 15, Puglia = 16, Basilicata = 17, Calabria = 18, Sicilia = 19, and Sardinia = 20), while other regions remain unaffected (Piedmont = 1, Valle d’Aosta = 2, Liguria = 3, Lombardy = 4, Trentino-Alto Adige = 5, Veneto = 6, Friuli-Venezia Giulia = 7, Emilia-Romagna = 8, Tuscany = 9, Umbria = 10, Marche = 11). Notably, the delta perturbation substantially affects the risk of poverty for the Lazio region (12 = Lazio), bringing it below the national average.

The right side of Figure 2 illustrates the regions where the poverty value decreases. Note that the knot’s multiplicity is marked by overturned ‘k’ letters on the horizontal axis and that the identity spline is the red dotted line.

3.2.2. Scenario 2

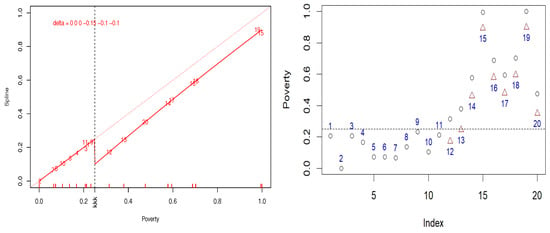

Figure 3 shows the second scenario. The nodal coefficients have been perturbed by . Due to the smoothness property of B-splines, a discontinuity arises in the function at 0.25 (with a knot multiplicity of 3). Since the first three values of are zero, poverty remains unchanged in the less impoverished regions within the first knot interval, as in Scenario 1. Conversely, the distinct values in the subsequent interval induce nonlinear changes in areas with high poverty, decreasing the values in the central-southern regions. In particular, for two regions—Lazio (12) and Abruzzo (13)—this adjustment results in a reduction in poverty, bringing the risk of poverty or social exclusion below the Italian average.

Figure 3.

Description of Scenario 2. In the left plot, the identity spline (red dotted line) of degree 2 has one knot at the poverty average value of 0.25, with a multiplicity of 3, marked by overturned ‘k’ letters on the horizontal axis, leading to a discontinuity at that point. In the right plot, poverty values are represented by (with the 9 regions of high poverty highlighted in red). After the delta perturbations ( = 0, 0, 0, −0.15, −0.1, −0.1), the new values marked with correspond to a decrease of the original values. Observe that the delta-perturbation moves Lazio (12) and Abruzzo (13) below the national average poverty threshold.

3.2.3. Scenario 3

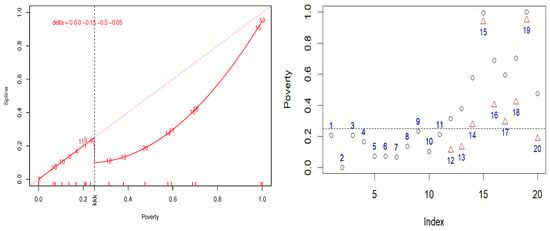

Figure 4 shows the third scenario. The nodal coefficients have been perturbed by different constant values, . Since the first three values of are zero, as in the first two scenarios, poverty remains unchanged in the northern, less impoverished regions within the first knot interval. However, the values in the subsequent interval induce significant changes in the central-southern regions. Now, in three regions—Lazio (12), Abruzzo (13), and Sardinia (20)—the reduction in poverty is substantial, bringing the risk of poverty or social exclusion in these regions below the Italian average.

Figure 4.

Description of Scenario 3. In the left plot, the identity spline (red dotted line) of degree 2 has one knot at the poverty average value of 0.25, with a multiplicity of 3, marked by overturned ‘k’ letters on the horizontal axis, leading to a discontinuity at that point. In the right plot, poverty values are represented by (with the nine regions of high poverty highlighted in red). After the delta perturbations ( = 0, 0, 0, −0.15, −0.5, −0.05), the new values marked with correspond to a decrease of the original values. Observe that the delta-perturbation moves Lazio (12), Abruzzo (13), and Sardinia (20) below the national average poverty threshold.

In summary, decision-makers can make real-time adjustments to specific components of the statistical model by locally modifying the observed response. The choice of the appropriate scenario, , depends on the available resources and time required to reach it. The decision process allows for online control of the changes in the response (target to pursue) and the immediate evaluation of a new model (here, PLS).

3.3. Comparing Poverty Scenarios

To understand which socio-economic indicators most affect changes in poverty across Italian regions, we first analyze the non-transformed poverty variable—named —using PLS regression model, i.e., . The model shows good fit and predictive accuracy. Specifically, the coefficient of determination is 0.90 and the PRESS value is very good (0.11) suggesting to retain only one component. Therefore, since PLS is the simpler and more parsimonious model, requiring only one component, we retain this linear model without seeing the need to construct a non-linear PLS model.

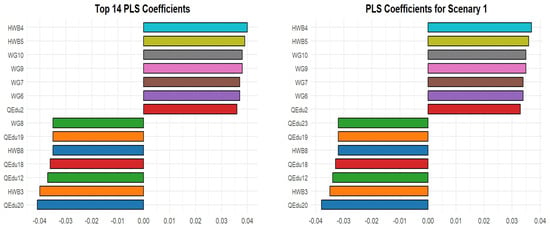

When the goal is to alleviate poverty in one of the most impoverished regions, we can consider Scenario 1 (see Figure 2), which produces the new response . This response differs from by a slight decrease in poverty in the nine most impoverished regions (12 = Lazio, 13 = Abruzzo, 14 = Molise, 15 = Campania, 16 = Puglia, 17 = Basilicata, 18 = Calabria, 19 = Sicilia, 20 = Sardegna), bringing the Lazio region below the Italian average for poverty, while leaving the northern, less impoverished regions unaffected. This poverty scenario is then compared to the original observed in Scenario 0 through the corresponding = PLS() model, see Table A1. The coefficient is 0.88, and the PRESS value is 0.13, indicating that the goodness of fit and predictive accuracy are very similar to those of the original model. The left panel of Figure 5 shows the bar plot of the effects of the predictor variables on poverty () in Scenario 0, while the right panel displays the corresponding bar plot for poverty () in Scenario 1. In both scenarios, and , the seven most important predictors with positive coefficients—HWB4 (Diabetes), HWB5 (Hypertension), WG10 (NEET, aged 15–24), WG9 (NEET), WG7 (Non-participation rate in the workforce), WG6 (Unemployment rate), and QEdu2 (Inadequate literacy skills, students in Grade III of lower secondary school)—are identical, as is their order of importance, although their values differ (see Figure 5 and Table A1). All of these predictors are statistically significant at the level, as shown in Table A2.

Figure 5.

Barplot of the first fourteen most PLS influential predictors for Scenarios 0 and 1.

Regarding the seven most important predictors with negative coefficients, six of them are identical (in position but not in value) across both scenarios: QEdu20 (Advanced digital skills), HWB3 (Healthy life expectancy at birth), QEdu12 (Nurseries and integrated services for early childhood), QEdu18 (Participation in continuous training), HWB8 (Ordinary ward beds in public and private healthcare institutions), and QEdu19 (At least basic digital skills). The remaining predictor differs in Scenario 1, where QEdu23 (Physically accessible schools) appears more relevant for Lazio than WG8 (Employment rate). Among these most influential predictors, HWB4 reflects the standardized prevalence of diabetes in the impoverished population and ranks first among the predictors with positive coefficients in Scenario 2 as well. Conversely, QEdu20 emphasizes that adequate digital skills are essential for lifting people out of poverty and is the most important predictor with a negative coefficient across all scenarios. For complete details on the predictor coefficients in the full model, and to check their statistical significance, see Table 1 and Table A2, respectively, in Appendix A.

Therefore, to alleviate poverty in the nine most disadvantaged regions—particularly in Lazio (Scenario 1)—greater efforts should be directed toward improving digital skills (QEdu20), increasing healthy life expectancy at birth (HWB3), expanding nurseries and integrated services for early childhood (QEdu12), enhancing participation in continuous training (QEdu18), increasing the availability of ordinary ward beds in public and private healthcare institutions (HWB8), and strengthening basic digital skills (QEdu19). Additionally, for Lazio in particular, attention should be given to increasing the number of physically accessible schools (QEdu23).

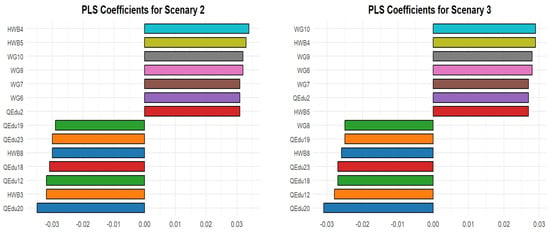

When the goal is to reduce the risk of poverty or social exclusion below the national average in two specific regions, Abruzzo and Lazio, we can consider Scenario 2 (see Figure 3), which leads to the new response (see the model in Table A1). This response differs from by exhibiting a stronger decrease (compared to Scenario 1) in the nine regions with the highest poverty levels—Lazio (12), Abruzzo (13), Molise (14), Campania (15), Puglia (16), Basilicata (17), Calabria (18), Sicilia (19), and Sardegna (20)—while the northern regions remain largely unaffected.

The coefficient is 0.86 and the PRESS value is 0.15 when retaining one component. Thus, the model’s goodness of fit and predictive accuracy remain strong.

The left panel of Figure 6 presents the predictors for poverty () under Scenario 2. The seven most influential predictors with positive coefficients are consistent with those identified in Scenario 1, although their values differ. Notably, six of the seven most important predictors with negative coefficients are shared with Scenario 0. The only variable that distinguishes Scenario 2—and ranks first relative to Scenario 1—is QEdu23, which reflects an increase in the number of physically accessible schools aimed at mitigating poverty.

Figure 6.

Barplot of the first fourteen most influential predictors on poverty for Scenario 2 and 3.

Overall, to effectively alleviate poverty in the two most disadvantaged regions—Abruzzo and Lazio—greater efforts should be directed toward increasing the number of physically accessible schools, along with improving all the other indicators.

Finally, when the goal is to reduce the risk of poverty or social exclusion below the national average in three specific regions—Abruzzo, Lazio, and Sardinia—we can consider Scenario 3 (see Figure 4), which produces the new response (see the model in Table A1). Again, this response differs from by showing a stronger decrease—compared with Scenarios 1 and 2—in the nine impoverished regions: Lazio (12), Abruzzo (13), Molise (14), Campania (15), Puglia (16), Basilicata (17), Calabria (18), Sicilia (19), and Sardinia (20), while leaving the remaining regions unaffected. As a result, in Abruzzo, Lazio, and Sardinia, poverty falls below the national average.

The coefficient is 0.66 and the PRESS value is 0.38 when retaining one component. Thus, the model’s goodness of fit and predictive accuracy remain acceptable.

The right panel of Figure 6 shows the fourteen most important predictors for poverty in Scenario 3. We note that the seven most important predictors with negative coefficients belong primarily to SDG 4 (Quality Education), unlike in Scenario 0. These include QEdu20, QEdu12, QEdu18, QEdu23, and QEdu19 (see also Table 1 and Table A1), all of which are statistically significant at the level, as shown in Table A2. Furthermore, we observe the increased relevance of WG8 (Employment rate) compared with HWB3 (Healthy life expectancy at birth), which ranks second in Scenarios 0, 1, and 2. Therefore, to effectively alleviate poverty in Sardinia, greater efforts should be made to enhance knowledge of advanced digital skills (QEdu20), which recent studies have identified as particularly relevant for reducing social inequalities in general (Park, 2017; van Deursen & Helsper, 2015). As in Scenarios 1 and 2, Scenario 3 also shows that expanding nurseries and integrated services for early childhood (QEdu12), enhancing participation in continuous training (QEdu18), increasing the number of physically accessible schools (QEdu23), increasing the number of ordinary ward beds in public and private healthcare institutions (HWB8), strengthening basic digital skills (QEdu19), and improving the employment rate (WG8) are crucial for alleviating poverty overall, and especially in Lazio, Abruzzo, and Sardinia.

4. Discussion

This paper presents a novel application of the identity spline (Marsden, 1970) within the framework of partial least squares regression models (Wold, 1966; Durand, 2001). The innovative use of the identity spline allows researchers and decision-makers to move beyond analysis of the observed response variable by constructing alternative target scenarios that reflect hypothetical or desired outcomes. This methodological approach is particularly valuable in complex socio-economic contexts, where observed data may not fully capture the dynamics or potential trajectories of key societal challenges such as poverty.

By systematically deviating from the observed response using the identity spline, we can simulate and assess how changes in specific predictors influence poverty outcomes across Italian regions. This capability provides a more flexible and forward-looking tool for policy evaluation. Unlike traditional regression models that focus solely on present conditions, our approach facilitates the exploration of what-if scenarios, helping to identify actionable strategies for poverty reduction under constrained resources and varying policy priorities.

The application of this method to three distinct poverty scenarios has yielded several important insights. Specifically, our findings suggest that particular attention should be paid to enhancing advanced digital skills (QEdu20) among the population (OECD, 2021b; Park, 2017; van Deursen & Helsper, 2015), as this factor consistently emerges as a key lever for reducing poverty levels. Similarly, reducing the prevalence of diabetes (HWB4) and hypertension (HWB5), increasing the number of young people not in employment, education, or training (NEETs; WG9 and WG10), reducing the unemployment rate (WG6) and non-participation in the workforce (WG7), and decreasing inadequate literacy skills of students in Grade III of lower secondary school (QEdu2) are critical targets. These predictors are not only relevant but also carry clear policy implications, aligning with well-established socio-economic mechanisms that drive exclusion and vulnerability (Carcillo et al., 2015; Lanza, 2015; OECD, 2021a; Marrero & Servén, 2022).

Moreover, the scenario-based analysis highlights the importance of addressing public health concerns, particularly through indicators such as HWB4 and HWB5, which reflect the standardized prevalence of diabetes and hypertension in the population. This finding underscores the intersection between health and economic deprivation, suggesting that efforts to tackle chronic conditions could have downstream effects on poverty alleviation. Recent global reports indicate that diabetes disproportionately affects disadvantaged populations and contributes to long-term economic hardship (WHO, 2016; Narayan et al., 2006). Therefore, reducing its prevalence through improved prevention and healthcare access is not only a public health priority but also a strategic component of sustainable anti-poverty policies.

These multidimensional linkages reaffirm the need for integrated policy approaches that cut across sectors such as health, education, and labor markets. Nevertheless, we acknowledge the inherent complexity of poverty as a multidimensional phenomenon. The scenarios discussed here are illustrative rather than exhaustive. Future work could build on these findings by incorporating additional response scenarios and predictor variables (Marrero & Servén, 2022). The selection of such variables should be guided by both theoretical considerations and the practical feasibility of monitoring and influencing SDG indicators at the regional level. In particular, further research is needed to understand how local contexts mediate the relationship between structural predictors and poverty outcomes, and how regional disparities in policy implementation may affect these results.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that the identity spline, when integrated within the PLS regression framework, provides an effective means of exploring alternative response scenarios and assessing the sensitivity of outcomes to changes in key predictors. Given the large set of predictors, characterized by strong intercorrelations, and the small sample size of the Italian regions, the PLS regression model is particularly suitable (Wold, 1966; Durand, 2001). However, the identity spline can also be applied within other regression models (Tibshirani, 1996), such as penalized regression models, to explore new response scenarios.

Applied to regional poverty in Italy, the model proves capable of identifying the most influential socio-economic determinants—such as education, employment, and health—while enabling the construction of hypothetical scenarios to support evidence-based policy design.

Beyond poverty analysis, the identity spline approach can be extended to other socio-economic and environmental domains where the capacity to model controlled changes in response variables is essential. For example, by using the national unemployment rate or the national average level of healthcare perfomance, the proposed method can help identify regional disparities and determine the main factors underlying such differences.

By enabling the formulation of what-if scenarios within a consistent statistical framework, this methodology offers a valuable contribution to scenario planning, policy evaluation, and sustainable development research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.-F.D. and R.L.; Methodology, J.-F.D. and R.L.; Software, J.-F.D.; Formal Analysis, R.L.; Data Curation, I.C. and C.C.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, R.L., I.C., J.-F.D., and C.C.; Supervision, J.-F.D.; Funding Acquisition, C.C., R.L. and I.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research has been funded by the following research projects: PRIN-2022 SciK-Health: Mapping Scientific Knowledge about Health for Decision-making (Project code: 2022825Y5E_02; CUP: B53D23009750006), and PRIN-2022 PNRR “The value of scientific production for patient care in A. H. S. C.” (Project Code: P2022RF38Y; CUP: B53D23026630001).

Data Availability Statement

The data are available from the ISTAT database, 30 October 2024 https://www.istat.it/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Misure-statistiche-2004-2024.xlsx. The figures and statistical results in this paper are derived from the free, open-source R package v.4.4.2 ‘Boosted Partial Least Squares Regression,’ available on the website “jf-durand-pls.com”.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no potential conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

In this appendix, we present Table A1, which reports the forty-nine predictor coefficients of the four models analyzed in this paper. The first model, , refers to the original values of poverty (), whereas the remaining models, , , and , correspond to the response variables , , and , respectively, associated with the three scenarios of poverty discussed in Section 3.

Table A1.

Predictor coefficients of the original linear (PLS) model applied to poverty (subscript 0) and its three different scenarios (subscripts 1, 2, and 3), with all predictors increasingly ordered.

Table A1.

Predictor coefficients of the original linear (PLS) model applied to poverty (subscript 0) and its three different scenarios (subscripts 1, 2, and 3), with all predictors increasingly ordered.

| Beta | Beta | Beta | Beta | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QEdu20 | −0.041 | QEdu20 | −0.038 | QEdu20 | −0.035 | QEdu20 | −0.031 |

| HWB3 | −0.040 | HWB3 | −0.035 | HWB3 | −0.032 | QEdu12 | −0.028 |

| QEdu12 | −0.037 | QEdu12 | −0.034 | QEdu12 | −0.032 | QEdu18 | −0.027 |

| QEdu18 | −0.036 | QEdu18 | −0.033 | QEdu18 | −0.031 | QEdu23 | −0.027 |

| HWB8 | −0.035 | HWB8 | −0.032 | HWB8 | −0.030 | HWB8 | −0.026 |

| QEdu19 | −0.035 | QEdu19 | −0.032 | QEdu23 | −0.030 | QEdu19 | −0.025 |

| WG8 | −0.035 | QEdu23 | −0.032 | QEdu19 | −0.029 | WG8 | −0.025 |

| QEdu23 | −0.034 | WG8 | −0.032 | WG8 | −0.029 | QEdu21 | −0.022 |

| QEdu21 | −0.029 | QEdu21 | −0.027 | QEdu21 | −0.026 | HWB3 | −0.021 |

| HWB6 | −0.013 | HWB6 | −0.013 | HWB6 | −0.013 | HWB11 | −0.014 |

| HWB11 | −0.012 | HWB11 | −0.012 | HWB11 | −0.011 | HWB6 | −0.012 |

| QEdu25 | −0.011 | QEdu25 | −0.009 | HWB9 | −0.008 | HWB10 | −0.010 |

| QEdu24 | −0.010 | HWB9 | −0.008 | QEdu25 | −0.008 | HWB9 | −0.009 |

| WG1 | −0.009 | HWB10 | −0.008 | HWB10 | −0.007 | WG1 | −0.007 |

| HWB9 | −0.008 | QEdu24 | −0.008 | WG1 | −0.007 | WG3 | −0.007 |

| HWB10 | −0.008 | WG1 | −0.008 | QEdu24 | −0.006 | WG2 | −0.006 |

| WG3 | −0.008 | WG2 | −0.007 | WG2 | −0.006 | QEdu24 | −0.004 |

| WG2 | −0.007 | WG3 | −0.007 | WG3 | −0.006 | QEdu25 | −0.004 |

| QEdu17 | 0.003 | QEdu17 | 0.002 | QEdu17 | 0.001 | QEdu17 | −0.002 |

| HWB12 | 0.005 | HWB12 | 0.003 | HWB12 | 0.002 | QEdu22 | −0.002 |

| QEdu14 | 0.005 | QEdu14 | 0.003 | QEdu14 | 0.002 | HWB12 | 0.002 |

| QEdu15 | 0.006 | QEdu15 | 0.005 | QEdu22 | 0.004 | QEdu14 | 0.004 |

| HWB7 | 0.007 | QEdu22 | 0.005 | QEdu15 | 0.005 | HWB7 | 0.006 |

| QEdu22 | 0.007 | HWB7 | 0.006 | HWB7 | 0.006 | QEdu15 | 0.009 |

| QEdu16 | 0.009 | QEdu16 | 0.008 | QEdu16 | 0.008 | QEdu16 | 0.010 |

| QEdu26 | 0.017 | QEdu26 | 0.016 | QEdu26 | 0.015 | QEdu26 | 0.016 |

| QEdu13 | 0.027 | HWB1 | 0.026 | HWB2 | 0.024 | QEdu10 | 0.019 |

| HWB1 | 0.028 | HWB2 | 0.026 | QEdu13 | 0.024 | HWB2 | 0.020 |

| HWB2 | 0.028 | QEdu13 | 0.026 | HWB1 | 0.025 | QEdu8 | 0.020 |

| QEdu8 | 0.030 | QEdu6 | 0.028 | QEdu6 | 0.025 | QEdu6 | 0.021 |

| QEdu6 | 0.031 | QEdu8 | 0.028 | QEdu8 | 0.025 | QEdu27 | 0.021 |

| QEdu10 | 0.031 | QEdu10 | 0.028 | QEdu10 | 0.025 | QEdu13 | 0.022 |

| QEdu27 | 0.031 | QEdu27 | 0.029 | WG4 | 0.026 | WG4 | 0.022 |

| WG4 | 0.032 | WG4 | 0.029 | QEdu27 | 0.027 | QEdu1 | 0.023 |

| QEdu11 | 0.033 | QEdu3 | 0.030 | QEdu1 | 0.028 | QEdu3 | 0.023 |

| QEdu1 | 0.034 | QEdu1 | 0.031 | QEdu3 | 0.028 | WG5 | 0.023 |

| QEdu3 | 0.034 | QEdu4 | 0.031 | QEdu11 | 0.028 | HWB1 | 0.024 |

| QEdu9 | 0.034 | QEdu9 | 0.031 | WG5 | 0.028 | QEdu4 | 0.024 |

| WG5 | 0.034 | QEdu11 | 0.031 | QEdu4 | 0.029 | QEdu7 | 0.024 |

| QEdu4 | 0.035 | WG5 | 0.031 | QEdu5 | 0.029 | QEdu5 | 0.025 |

| QEdu5 | 0.035 | QEdu5 | 0.032 | QEdu7 | 0.029 | QEdu9 | 0.025 |

| QEdu7 | 0.035 | QEdu7 | 0.032 | QEdu9 | 0.029 | QEdu11 | 0.026 |

| QEdu2 | 0.036 | QEdu2 | 0.033 | QEdu2 | 0.031 | HWB5 | 0.027 |

| WG6 | 0.037 | WG6 | 0.034 | WG6 | 0.031 | QEdu2 | 0.027 |

| WG7 | 0.037 | WG7 | 0.034 | WG7 | 0.031 | WG7 | 0.027 |

| WG9 | 0.038 | WG9 | 0.035 | WG9 | 0.032 | WG6 | 0.028 |

| WG10 | 0.038 | WG10 | 0.035 | WG10 | 0.032 | WG9 | 0.028 |

| HWB5 | 0.039 | HWB5 | 0.036 | HWB5 | 0.033 | HWB4 | 0.029 |

| HWB4 | 0.040 | HWB4 | 0.037 | HWB4 | 0.034 | WG10 | 0.029 |

Note that the most influential predictors, in absolute value, which are also displayed in Figure 5 and Figure 6, are highlighted in bold.

Significance of Predictors Across Confidence Levels

Table A2 reports the estimated PLS coefficients together with their 90% (*), 95% (**), and 99% (***) bootstrap confidence intervals, based on 1000 replicates.

Table A2.

Bootstrap confidence intervals for PLS regression coefficients (). Significant coefficients at are marked with **.

Table A2.

Bootstrap confidence intervals for PLS regression coefficients (). Significant coefficients at are marked with **.

| Predictor | Estimate | Lower | Upper |

|---|---|---|---|

| HWB1 * | 0.028 | 0.002 | 0.057 |

| HWB2 ** | 0.028 | 0.018 | 0.036 |

| HWB3 *** | −0.040 | −0.071 | −0.028 |

| HWB4 ** | 0.040 | 0.027 | 0.054 |

| HWB5 ** | 0.039 | 0.026 | 0.064 |

| HWB6 | −0.013 | −0.037 | 0.022 |

| HWB7 | 0.007 | −0.008 | 0.023 |

| HWB8 *** | −0.035 | −0.049 | −0.022 |

| HWB9 | −0.008 | −0.040 | 0.012 |

| HWB10 | −0.008 | −0.027 | 0.011 |

| HWB11 | −0.012 | −0.033 | 0.006 |

| HWB12 | 0.005 | −0.010 | 0.018 |

| QEdu1 ** | 0.034 | 0.025 | 0.046 |

| QEdu2 ** | 0.036 | 0.024 | 0.049 |

| QEdu3 *** | 0.034 | 0.025 | 0.040 |

| QEdu4 ** | 0.035 | 0.024 | 0.045 |

| QEdu5 ** | 0.035 | 0.025 | 0.046 |

| QEdu6 ** | 0.031 | 0.023 | 0.037 |

| QEdu7 ** | 0.035 | 0.027 | 0.042 |

| QEdu8 ** | 0.030 | 0.023 | 0.036 |

| QEdu9 ** | 0.034 | 0.025 | 0.047 |

| QEdu10 ** | 0.031 | 0.023 | 0.041 |

| QEdu11 * | 0.033 | 0.021 | 0.042 |

| QEdu12 *** | −0.037 | −0.044 | −0.027 |

| QEdu13 * | 0.027 | 0.009 | 0.054 |

| QEdu14 | 0.005 | −0.013 | 0.030 |

| QEdu15 | 0.006 | −0.013 | 0.029 |

| QEdu16 | 0.009 | −0.014 | 0.029 |

| QEdu17 | 0.003 | −0.019 | 0.017 |

| QEdu18 *** | −0.036 | −0.042 | −0.028 |

| QEdu19 *** | −0.035 | −0.040 | −0.027 |

| QEdu20 *** | −0.041 | −0.047 | −0.032 |

| QEdu21 *** | −0.029 | −0.037 | −0.019 |

| QEdu22 | 0.007 | −0.031 | 0.024 |

| QEdu23 *** | −0.034 | −0.088 | −0.019 |

| QEdu24 | −0.010 | −0.050 | 0.005 |

| QEdu25 | −0.011 | −0.026 | 0.014 |

| QEdu26 | 0.017 | −0.003 | 0.040 |

| QEdu27 ** | 0.031 | 0.020 | 0.058 |

| WG1 | −0.009 | −0.031 | 0.014 |

| WG2 | −0.007 | −0.029 | 0.015 |

| WG3 | −0.008 | −0.026 | 0.011 |

| WG4 ** | 0.032 | 0.018 | 0.038 |

| WG5 ** | 0.034 | 0.023 | 0.048 |

| WG6 ** | 0.037 | 0.027 | 0.046 |

| WG7 ** | 0.037 | 0.029 | 0.043 |

| WG8 *** | −0.035 | −0.040 | −0.027 |

| WG9 ** | 0.038 | 0.030 | 0.045 |

| WG10 ** | 0.038 | 0.029 | 0.047 |

As expected, the interval width increases with the confidence level. Several predictors remain statistically significant across all three levels, confirming the robustness of their effects. In particular, HWB3, HWB8, QEdu3, QEdu12, QEdu18–QEdu21, QEdu23, and WG8 are significant even at the 99% level ().

A second group of variables, including HWB2, HWB4–HWB5, most of the education-related indicators (QEdu1–QEdu11, except for QEdu12), QEdu27, and the work-growth dimensions (WG4–WG7, WG9–WG10), remain significant at the 95% level () but lose significance at 99%.

Finally, HWB1, QEdu11, and QEdu13 are significant only at the 90% level (), whereas the remaining predictors include zero in all intervals, indicating no statistically significant relationship.

References

- Alaimo, L. S., & Maggino, F. (2020). Sustainable development goals indicators at territorial level: Conceptual and methodological issues—The Italian perspective. Social Indicators Research: An International and Interdisciplinary Journal for Quality-of-Life Measurement, 147(2), 383–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camminatiello, I., Lombardo, R., Musella, M., & Borrata, G. (2023). A model for evaluating inequalities in sustainability. Social Indicators Research, 175, 879–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carcillo, S., Fernández, R., Königs, S., & Minea, A. (2015). NEET youth in the aftermath of the crisis: Challenges and policies. (OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 164). OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caroleo, F. E., Rocca, A., Mazzocchi, P., & Quintano, C. (2020). Being NEET in Europe before and after the economic crisis: An analysis of the micro and macro determinants. Social Indicators Research, 149, 991–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciommi, M., Gigliarano, C., & Chelli, F. M. (2021). Incidence, intensity and inequality of poverty in Italy. Rivista Italiana di Economia Demografia e Statistica, LXXV(4), 41–52. [Google Scholar]

- D’Adamo, I., Gastaldi, M., & Uricchio, A. F. (2025). A multiple criteria analysis approach for assessing regional and territorial progress toward achieving the sustainable development goals in Italy. Decision Analytics Journal, 15, 100559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dollar, D., Kleineberg, T., & Kraay, A. (2016). Growth still is good for the poor. European Economic Review, 81(C), 68–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durand, J. F. (2001). Local polynomial additive regression through PLS and splines: PLSs. Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory Systems, 58, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durand, J. F., Lombardo, R., & Camminatiello, I. (2025). Identity spline variations in boosted partial least-squares: A study on poverty. Statistical Methods & Applications. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durand, J. F., & Sabatier, R. (1997). Additive splines for partial least squares regression. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 92(440), 1050–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcés-Urzainqui, D. (2024). Poverty dynamics and vulnerability during a growth episode. evidence from Bangladesh: 2000–2016. The Journal of Development Studies, 61(5), 797–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greville, T. (1967). On the normalisation of the B-splines and the location of the nodes for the case of unequally spaced knots. In O. Shisha (Ed.), Inequalities (pp. 286–290). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lanza, G. (2015). La misurazione della disuguaglianza economica: Approcci, metodi e strumenti. Franco Angeli. [Google Scholar]

- Lombardo, R., Durand, J. F., & De Veaux, R. (2009). Model building in multivariate additive partial least squares splines via the GCV criterion. Journal of Chemometrics, 23, 605–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, J., Smith, G. D., Harper, S., Hillemeier, M., Ross, N., Kaplan, G. A., & Wolfson, M. (2004). Is income inequality a determinant of population health? Part 1. A systematic review. Milbank Quarterly, 82(1), 5–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mackenbach, J. P., Bakker, M., & Benach, J. (2002). Reducing inequalities in health: A European perspective. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Marrero, G. A., & Servén, L. (2022). Growth, inequality and poverty: A robust relationship? Empirical Economics, 63, 725–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsden, M. (1970). An identity for spline functions with applications to variation-diminishing spline approximation. Journal of Approximation Theory, 3, 7–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, K. M. V., Zhang, P., Kanaya, A. M., Williams, D. E., Engelgau, M. M., Imperatore, G., & Ramachandran, A. (2006). Diabetes: The pandemic and potential solutions. In D. T. Jamison, J. G. Breman, A. R. Measham, G. Alleyne, M. Claeson, D. B. Evans, P. Jha, A. Mills, & P. Musgrove (Eds.), Disease control priorities in developing countries (2nd ed., pp. 591–603). World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Neckerman, K. (2004). Social inequality. Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. (2021a). Labour market developments: The unfolding COVID-19 crisis. OECD employment outlook 2021. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2021/07/oecd-employment-outlook-2021_e81ed73a/5a700c4b-en.pdf (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- OECD. (2021b). The digital transformation of education: Connecting schools, empowering learners. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/education/ (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- Park, S. (2017). Digital inequalities in rural Australia: A double jeopardy of remoteness and social exclusion. Journal of Rural Studies, 54, 399–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piketty, T., & Saez, E. (2003). Income inequality in the United States, 1913–1998. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118(1), 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, W. H., Burroughs, N. A., Zoido, P., & Houang, R. T. (2015). The role of schooling in perpetuating educational inequality: An international perspective. Educational Researcher, 44(7), 371–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shumaker, L. (1981). Spline functions: Basic theory. Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Tibshirani, R. (1996). Regression shrinkage and selection via the lasso. Journal of the Royal Statistical Association, 58(1), 267–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmis, A., Vardas, P., Townsend, N., Torbica, A., Katus, H., De Smedt, D., Gale, C. P., Maggioni, A. P., Petersen, S. E., Huculeci, R., Kazakiewicz, D., de Benito Rubio, V., Ignatiuk, B., Raisi-Estabragh, Z., Pawlak, A., Karagiannidis, E., Treskes, R., Gaita, D., Beltrame, J. F., … Atlas Writing Group, European Society of Cardiology. (2022). European society of cardiology: Cardiovascular disease statistics 2021. European Heart Journal, 43(8), 716–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Deursen, A. J. A. M., & Helsper, E. J. (2015). The third-level digital divide: Who benefits most from being online? Communication and Information Technologies Annual, 10, 29–52. [Google Scholar]

- Wold, H. (1966). Estimation of principal components and related models by iterative least squares. In P. Krishnaiah (Ed.), Multivariate analysis (pp. 391–420). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wold, H. (1975). Soft modelling by latent variables: Non-linear iterative partial least squares approach. In J. Gani (Ed.), Perspectives in probability and statistics: Papers in honour of Bartlett (pp. 117–142). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wold, H. (1985). Partial least squares. In S. Kotz, & N. Johnson (Eds.), Encyclopedia of statistical sciences (Vol. 6, pp. 581–591). Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2016). Global report on diabetes. WHO. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241565257 (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Xhafaj, E., & Nurja, I. (2014). Determination of the key factors that influence poverty through econometric models. European Scientific Journal, 10(24), 65–72. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).