Abstract

Industrial wireless sensor and actuator networks (IWSANs) are central to Industry 4.0, supporting distributed sensing, actuation, and communication in cyber-physical production systems. Unlike previous studies, which focus on isolated constraints, this review synthesises recent work across eight coupled dimensions. These span reliability and fault tolerance, security and trust, time synchronisation, energy harvesting and power management, media access control (MAC) and scheduling, interoperability, routing and topology control, and real-world validation, within a unified comparative framework. Following Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines, a Scopus search identified 60 primary publications published between 2022 and 2025. The analysis shows a clear shift from reactive designs to predictive approaches that incorporate learning methods and energy considerations. Fault detection now relies on deep learning (DL) and statistical modelling, security incorporates trust and intrusion detection, and new synchronisation and MAC schemes approach wired levels of determinism. Regarding applied contributions, the analysis notes that routing and energy harvesting advances extend network lifetime. However, gaps remain in mobility support, interoperability across protocol layers, and field validation. The present work outlines these open issues and highlights research directions needed to mature IWSANs into robust infrastructure for Industry 4.0 and the emerging Industry 5.0 vision.

1. Introduction

1.1. Evolution from Industry 4.0 Towards Industry 5.0

The emergence of Industry 4.0 has reshaped industrial systems into interconnected, intelligent, and adaptive environments. Foundational to this transformation are cyber-physical systems (CPSs), wireless sensor networks (WSNs), and the Internet of Things (IoT). These technologies enable continuous monitoring, autonomous decision processes, and predictive control. Such capabilities open up unprecedented opportunities for efficiency, safety, and scalability across industrial domains. By embedding wireless connectivity into industrial infrastructures, organisations can reduce the rigidity and costs of wired solutions. At the same time, they gain greater flexibility in both monitoring and control. Yet, despite their transformative potential, IWSANs face limited adoption due to reliability, security, energy, and interoperability constraints [1,2].

More recently, attention has shifted from Industry 4.0 automation to Industry 5.0, commonly characterised by human-centricity, sustainability, and resilience. From an IWSAN perspective, human-centricity implies that industrial connectivity must support safe and trustworthy human–machine collaboration. As a result, the need for predictable communication with minimal delay in sensing and actuation loops increases. It also reinforces the need to integrate security into system design and to ensure privacy conscious data handling across the network. Sustainability places greater emphasis on energy-aware network design and lifecycle considerations. This reinforces the importance of energy-efficient protocols and architectures that are already central to industrial wireless systems. Finally, resilience shifts attention from nominal performance to continuity under disruption. Therefore, fault-tolerant and adaptive IWSAN architectures are required to maintain essential monitoring and actuation services under faults, attacks, and other disruptions [3,4,5].

1.2. From WSNs to IWSANs for Closed-Loop Connectivity

Against this background, it is useful to outline how WSNs evolved into IWSANs to support closed-loop operation. At the field level, WSNs comprise battery-powered sensor nodes that sense, process locally, and use short-range wireless links to relay measurements. Deployed in industrial settings for process monitoring, safety, and supply chain supervision, these networks become industrial wireless sensor networks (IWSNs). In this case, sensor nodes in harsh areas measure process variables and forward them in a multi-hop fashion to gateways, process controllers and host management systems. This architecture reduces wiring costs and increases flexibility, supporting smart factory concepts. Wireless sensor and actuator networks (WSANs) extend WSNs by introducing actuators. These devices act on the physical environment while also communicating and coordinating, tightly integrating sensing, decision making, and actuation. In industrial settings, this integration leads to IWSANs, where sensors communicate with actuators and actuators may also coordinate among themselves. Compared with traditional WSNs, IWSANs must meet stringent real-time and reliability requirements to support Industry 4.0 closed-loop applications such as safety systems, networked control, and predictive maintenance [6]. Unless otherwise specified, the term “industrial wireless networks (IWNs)” refers collectively to WSNs, IWSNs, WSANs, and IWSANs used in industrial settings.

1.3. IoT, IIoT, and the Role of Industrial Wireless Networks

To place IWNs within Industry 4.0 and the transition towards Industry 5.0, it is necessary to clarify the relationship between IoT, the Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT), and the supporting wireless networks. IoT broadly refers to large numbers of connected devices communicating over internet technologies, typically serving consumer-oriented applications. IIoT extends these concepts to industrial environments by interconnecting sensors, actuators, controllers, and supervisory systems to improve efficiency through process optimisation, higher throughput, and more flexible plant operation. Compared with generic IoT deployments, IIoT systems build on existing industrial infrastructure and depend on dense, high-precision sensor networks. Within this landscape, IWNs provide the sensing and actuation connectivity that links machines, processes, and human operators [7].

1.4. Requirements for Sensing and Networking in IIoT

Accordingly, effective IIoT operation depends on meeting strict requirements at both the sensor and network levels. Therefore, sensor performance criteria such as accuracy, resolution, sampling rate, and long-term stability must be explicitly defined. Sensors should also support metrological traceability and report measurement uncertainty to ensure trustworthy analytics over time. This is especially important as networks evolve or as sensors are recalibrated or replaced. Additionally, industrial sensors must withstand harsh environments and operate under tight resource constraints, including limited energy, processing power, and memory. At the network level, requirements include low latency, high reliability, time synchronisation, fault tolerance, and security. These requirements collectively shape sensor selection and integration in industrial systems. In practice, achieving these targets increases communication overhead, making energy efficiency a key design constraint [2,8].

1.5. Energy Efficiency in Industrial Wireless Networks

Given that wireless communication dominates energy consumption in IWNs, energy-aware design prioritises reducing transmissions and balancing energy use across nodes rather than minimising hop count. Consequently, hierarchical routing is widely used, with cluster heads aggregating or fusing data to suppress redundancy and extend network lifetime [9]. Complementary lifetime-maximisation techniques focus on sleep–wake operation and joint optimisation. Joint routing-sleep scheduling has been reported to extend network lifetime compared with routing-only or sleep-only baselines. It achieves this by keeping idle nodes in low-power states, balancing forwarding load, and still meeting delay constraints. Overall, the strongest gains come from co-designing routing or clustering, MAC scheduling, and data aggregation to suppress redundancy, maximise radio sleep time, and avoid premature depletion of heavily loaded nodes [10].

1.6. Research Trends in Industrial Wireless Networks

Given the critical role of IWNs in enabling Industry 4.0 applications, extensive research efforts have emerged to address their design, reliability, and integration challenges. A comprehensive synthesis of more than 130 studies [1] demonstrated how these technologies contribute to smart factories, digital twins, and CPSs. At the same time, it highlighted vulnerabilities such as network intrusions, flooding attacks, and protocol incompatibilities. The review also identified unresolved gaps in scalability and security. This indicates that WSNs and IoT, though essential for Industry 4.0, still need significant reinforcement for industrial integration at a large scale.

Building on this foundation, Güngör and Hancke [2] analysed IWSNs from a design principles perspective, emphasising the unique requirements imposed by harsh industrial environments. Their framework of design goals included low cost, scalability, energy efficiency, fault tolerance, and time synchronisation. They also surveyed emerging technical approaches such as energy harvesting methods, middleware platforms, and integrated architectures. Protocols such as wireless highway addressable remote transducer (HART), ISA100 (developed by the International Society of Automation), and Zigbee were examined for their potential to meet industrial demands. Each, however, presented limitations in terms of interoperability, latency, and security. This review underscored the need for a balanced approach that combines hardware and protocol innovations to address industrial challenges.

As the field matured, attention expanded from design principles to real-time performance in CPSs. A combined review and experimental investigation [11] explored scheduling and routing techniques, supported by testbeds and simulators. Experiments comparing source and graph routing under interference conditions revealed how network choices directly affect latency, reliability, and energy consumption in real industrial scenarios. Case studies on emergency communication protocols further demonstrated the importance of cyber-physical codesign. This approach jointly optimises communication strategies and control algorithms to ensure reliable system response. At the same time, both earlier solutions and new experimental findings showed that achieving strict timing guarantees in IWSNs remains a complex challenge.

From an industrial standpoint, such performance guarantees alone are insufficient. Somappa et al. [12] expanded the discussion by classifying application domains, ranging from safety-critical systems to open-loop monitoring. Each domain was systematically linked to its requirements for latency, scalability, and service differentiation. The study compared how standards such as wireless HART, ISA100.11a [13], and wireless networks for industrial automation-process automation (WIA-PA) addressed these needs. Persistent gaps were revealed, particularly in achieving a predictable quality of service under realistic deployment conditions. Importantly, the authors noted a gap between simulation assumptions and real industrial constraints.

Parallel to these developments, Åkerberg et al. [14] outlined a research agenda that stressed the importance of safety, actuator support, system integration, and coexistence. While many standards offer efficient sensing capabilities, deterministic downlink communication to actuators, which is essential for closed-loop control, remains insufficiently addressed. Furthermore, integration with legacy fieldbus systems is hindered by the limited standardisation of gateways and interoperability mechanisms. Their work also drew attention to scalability constraints, electromagnetic interference, and challenges related to hybrid power. Addressing such barriers requires not only technical innovation but also alignment in architecture and regulations.

In recent years, focus has shifted towards one of the most critical bottlenecks of IWSNs, namely their limited operational lifetime. Yadav and Kumar [15] addressed this issue in a practical implementation study, proposing energy-aware routing, power-saving protocols, energy harvesting, sleep scheduling, and data aggregation. Their comparative analysis showed efficiency gains exceeding 90% compared to earlier approaches. Moreover, they emphasised environmental benefits, including reduced battery waste and lower energy consumption, aligning IWSN development with global sustainability goals.

1.7. Persistent Challenges and Research Gap

Drawing on the literature reviewed and the evolution summarised in Table 1, a set of persistent and interrelated challenges emerges. Industrial conditions cause node, link, or gateway failures [2,12,14]. At the same time, previously reported vulnerabilities and protocol heterogeneity show that IWSNs in Industry 4.0 settings require robust security and trust solutions. They also need interoperability with existing industrial standards and legacy systems [1,12,14]. Furthermore, design goals such as time synchronisation, predictable scheduling at the MAC layer, and energy sustainability through harvesting and power management have been defined in earlier studies. However, they remain only partially addressed in realistic deployments [2,11,15]. This is consistent with recent 2025 studies that propose targeted advances in secure routing, clustering, mobility support, and industrial time management. However, they do not yet close the persistent gap between proposed methods and large-scale, experimentally validated industrial deployments [16,17,18,19,20]. Finally, several authors emphasise the gap between simulated proposals and real or experimental industrial validation [11,12].

Table 1.

Evolution of research focus on IWSANs.

Accordingly, the following analysis revisits these recurring challenges jointly in the Industry 4.0 context rather than in isolation. Unlike the studies in Table 1, which typically address single dimensions, this review compares reliability, security, synchronisation, MAC, interoperability, routing, and experimental validation within one framework. This integrated view helps distinguish simulation-only approaches from field-validated solutions and clarifies the remaining barriers to large-scale industrial adoption.

1.8. Study Roadmap and Review Framework

Table 1 highlights selected influential contributions discussed in this introduction, rather than offering a full chronology of IWNs research. Thus, the depicted progression should not be viewed as strictly linear. Nevertheless, a clear evolution from WSNs to IWSNs and IWSANs emerges, along with a diversification of technical directions warranting joint analysis. To capture this diversity transparently, the review adopts the PRISMA 2020 methodology and a formal risk of bias assessment. Within this framework, recent industrial wireless network developments for Industry 4.0 are organised into thematic groups, enabling structured synthesis, revealing validation gaps, and guiding future research in industrial wireless systems. To further clarify the research orientation and methodological framework of this review, Table 2 summarises its classification based on nature, objective, approach, and methodological procedure.

Table 2.

Classification of the present research.

To avoid ambiguity, key terms are used consistently throughout this review. Reliability refers to the ability of industrial wireless networks to meet required service levels over time under stated conditions. Fault tolerance denotes mechanisms that maintain acceptable operation in the presence of faults. Robustness describes limited performance degradation under uncertainty and non-fault disturbances. Resilience is used in a broader sense as the capability to withstand disruptions and, when needed, recover and restore service through adaptation.

The remainder is structured as follows. Section 2 describes the methodology adopted for the systematic review, including the formulation of research questions (RQs), the literature search strategy, and risk of bias assessment. Section 3 presents the results and analysis, encompassing publication trends, keyword co-occurrence, and detailed findings for each of the eight RQs. Section 4 consolidates the evidence into cross-cutting insights by comparing the identified approaches across the RQs, highlighting where results converge or conflict, and translating the findings into actionable research gaps and implications for real industrial deployment. Section 5 concludes by summarising the main takeaways and stating focused directions for future work.

2. Methodology

A systematic review protocol consistent with established reporting guidelines [21] was used to ensure transparency and rigour. These guidelines define procedures for formulating RQs, designing the search strategy, inclusion criteria, study selection, data extraction, and synthesis.

2.1. Formulation of Research Questions

Formulating clear and focused RQs is essential for guiding a systematic review. The RQs are a direct response to the persistent gaps identified in Section 1 and to the remaining challenges summarised in Table 1. As shown there, industrial deployments still report: (i) node, link, and gateway failures under harsh conditions, (ii) cybersecurity vulnerabilities and lack of trust in heterogeneous IIoT settings, (iii) the need for precise temporal coordination for closed-loop CPSs, (iv) limitations in energy sustainability and lifetime extension, (v) difficulties in achieving timely and predictable medium access in dense industrial networks, (vi) interoperability barriers with legacy and standardised industrial communication systems, (vii) the need for optimised routing, clustering, and topology control under resource constraints, and (viii) a gap between simulated proposals and real or experimental industrial validation. Each of the following RQs corresponds to one of these eight challenge areas.

- How is fault detection and fault-tolerant communication being addressed to improve the reliability of IWNs?

- What security and trust mechanisms have recently been proposed to protect IWNs from cyber threats in Industry 4.0 systems?

- What methods are being developed to achieve accurate and efficient time synchronisation in IWNs?

- How are recent strategies in energy harvesting and power management enhancing the sustainability of IWNs?

- What advancements in MAC protocols and scheduling algorithms are enabling efficient and reliable communication in IWNs?

- What approaches are being explored to ensure protocol compatibility and interoperability between IWNs and industrial communication systems?

- What recent techniques have been proposed for energy-aware routing, topology control, and network planning in IWNs?

- How are IWNs being applied and validated through real-world deployments and testbeds in industrial scenarios?

2.2. Literature Search Strategy

The literature search was conducted in Scopus and finalised on 1 September 2025 using a keyword strategy tailored to capture relevant studies in the field. Comparative analyses have reported small differences in retrieval volumes between Scopus and Web of Science for comparable searches [22]. Nevertheless, bibliographic databases differ in coverage and indexing practices, which can influence both the retrieved corpus and citation-based analyses. Therefore, a limited number of relevant studies indexed exclusively in other databases may not have been captured [23].

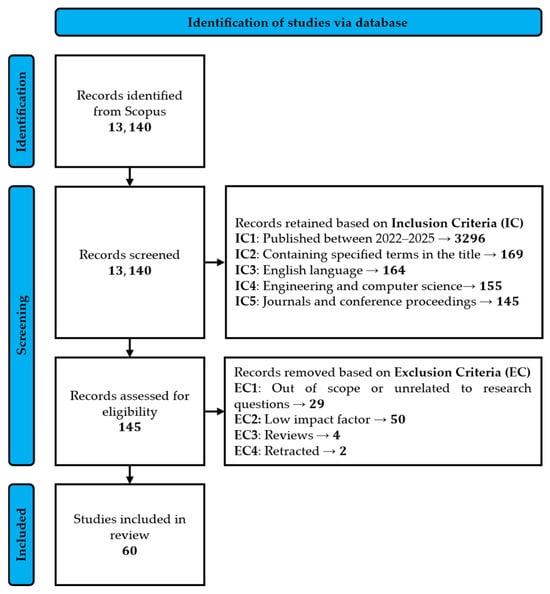

Based on this search scope, the broad query “TITLE-ABS-KEY (wsn OR (wireless AND sensor AND network*) AND industr*)” initially retrieved 13,140 records. To broaden coverage, the asterisk symbol served as a wildcard, capturing variations such as network/networks/networking and industry/industrial/industries. After applying the inclusion criteria, the dataset was reduced to 145 published works. The screening and exclusion decisions are summarised in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1), resulting in a final set of 60 included articles. The applied search string, filters, and parameters are summarised in Table 3.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart of the study selection process.

Table 3.

Search query used for retrieving studies from Scopus.

2.3. Data Extraction, Quality Assessment, and Synthesis

A risk of bias assessment was conducted for all included studies, in alignment with PRISMA 2020 guidelines. A custom five-criterion checklist was developed to evaluate methodological transparency and credibility. Each study was appraised across: (1) clarity of objectives and methodology, (2) transparency of data and assumptions, (3) appropriateness of analytical methods, (4) validation or empirical support, and (5) disclosure of funding sources or conflicts of interest. Each domain was rated as low, moderate, or high risk, and an overall rating was assigned based on the severity and consistency of concerns across domains. Among the 60 studies reviewed, 5 were rated as low risk, 4 as low to moderate risk, and 51 as moderate risk. No study was classified as high risk. Common issues included limited reproducibility, incomplete methodological reporting, and lack of accessible data or code. A detailed breakdown of individual scores and justifications is provided in Supplementary Table S1.

Data extraction was conducted independently by all authors and cross-checked for consistency and accuracy. Each study was mapped to the RQs it addressed. The findings are organised into thematic blocks covering reliability and fault tolerance, security and trust, time synchronisation, energy and lifetime, MAC and scheduling, interoperability, routing and topology, and experimental validation.

3. Results and Analysis

This section brings together the key findings from the systematic analysis. It begins by examining publication trends to highlight how scholarly interest in the topic has developed over time. Next, a keyword co-occurrence analysis reveals the underlying intellectual structure, identifying dominant thematic clusters within the literature. The 60 studies included in the review are then grouped according to the RQs outlined earlier, with each thematic area explored individually.

3.1. Publication Trends and Research Activity

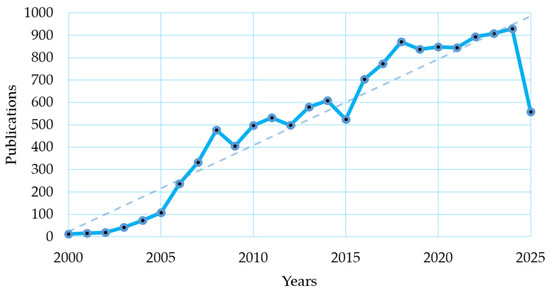

Figure 2 shows the annual distribution of publications from 2000 to 2025 using the broad query described in Section 2.2, without additional filters. Results indicate a steady increase in research activity, with pronounced growth after 2005 and a peak in 2024. The apparent decline in 2025 reflects the year being incomplete. A fitted trend line further confirms the over-all upward trajectory and the field’s growing importance.

Figure 2.

Publication trends in the research domain.

3.2. Thematic Keyword Co-Occurrence Analysis

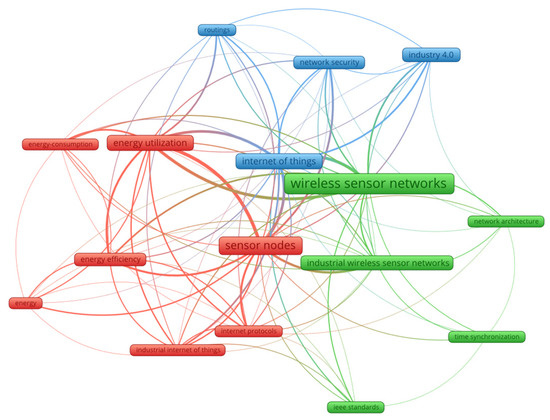

To identify the main research themes within the reviewed literature, a keyword co-occurrence network was constructed using open-source software, Visualisation of Similarities Viewer (version 1.6.20). Figure 3 shows nodes representing keywords, where node and label size indicates frequency of occurrence and link thickness represents co-occurrence strength. Colours indicate clusters of related keywords.

Figure 3.

Interconnected research themes in Industry 4.0 and IWNs.

Three dominant clusters emerge: (i) energy-related studies focusing on energy utilisation, efficiency, and consumption in relation to sensor nodes, (ii) security and architectural concerns, including synchronisation, network architecture, and Industry 4.0 integration, and (iii) networked approaches emphasising IoT, IIoT, routing, and standardisation.

3.3. Reliability and Fault Tolerance (RQ1)

Permanent faults represent one of the biggest risks for IWNs. A study by Heidari et al. [24] analysed reliability and availability using fault tree analysis and Markov chains. Different network topologies and redundancy were tested to show how permanent node failures impact long-term performance. Results show that replication and careful design can significantly improve availability and highlight critical nodes that require protection.

Another line of research focuses on intelligent routing to handle node and link faults. Kaur and Chanak [25] proposed a reinforcement learning and whale optimisation scheme for IIoT. Their method dynamically selects backup cluster heads and reroutes traffic when nodes fail. Both simulations and a fire-detection testbed showed improvements in throughput, energy efficiency, and lifetime compared to traditional routing.

Fault detection has also been addressed through mobile agents in obstacle-rich environments. Kaur et al. [26] developed an obstacle-aware detection scheme using mobile nodes that avoid barriers while checking for faulty sensors. They combined meta-heuristics such as grey wolf optimisation and ant colony optimisation with machine learning (ML) classifiers. This scheme enhanced the accuracy of detecting both hard and soft faults while reducing energy waste.

Predictive methods represent another approach to fault tolerance. Ruan et al. [27] introduced a DL model, the cumulative uncertainty reduction network, designed for fault prediction in CPSs. Trained on large chemical plant datasets, the system was able to forecast failures up to two minutes in advance. By incorporating a new recursive gradient descent method, it achieved higher accuracy in predicting rare events.

Other studies focus on statistical sensor fusion for detection and localisation. Tabella et al. [28] proposed Bayesian frameworks that combine one-bit decisions from distributed sensors. The system adapts thresholds and fuses evidence across time and space to identify and localise faults. Results showed faster detection and fewer false alarms compared to Shewhart and cumulative sum control chart methods.

Critical node detection is another essential topic for reliability. Shukla [29] introduced the angle-based critical nodes detection algorithm. It identifies boundary and articulation points in the network using only angle and signal strength information, without relying on the global positioning system. Experiments showed higher accuracy and lower energy consumption compared to earlier methods.

Finally, cascading failures caused by data overload are a major threat in hierarchical networks. Lv et al. [30] built a cascading failure model for cluster topologies, introducing new metrics that include both survivability and communication efficiency. They tested different load distribution strategies and showed that dynamic methods reduce the risk of large-scale collapse. Increasing the capacity of single-hop cluster heads also proved effective for avoiding failure chains.

3.4. Security, Intrusion Detection, and Trust Management (RQ2)

Research on security and trust in IWNs has expanded in several directions, particularly in intrusion detection. Predictive frameworks that combine decision trees, multilayer perceptrons, and autoencoders have shown detection accuracy above 99%. These systems are able to identify threats such as blackhole, grayhole, and flooding attacks, while also ranking the most severe threats for faster response [31]. Similar results appear in studies using spatial-temporal DL. By combining convolutional layers with recurrent units, denial of service (DoS) attacks can be detected with high precision and lower false alarms [32]. Feature selection has also become important. Enhanced adaptive butterfly optimisation has been applied together with DL, improving detection by choosing only the most relevant data features. This method achieved up to 97% accuracy and clearly outperformed standard optimisation techniques [33].

Another important theme is trust management. Generative adversarial networks (GANs) have been used to strengthen trust-based clustering. They help the system distinguish malicious nodes even when only a small amount of data is available. To reduce false positives, fuzzy logic and redemption models are added, so that misclassified nodes can regain trust [34]. Another approach proposed a trust framework called multi-layered assessment system for trustworthiness enhancement and reliability. This system observes both direct behaviour and feedback from other nodes. It can detect Sybil and on-off attacks with high accuracy. At the same time, it helps extend network lifetime by saving energy [35].

Work on jamming detection takes a different angle by relying on collaboration between nodes. Sensors share information about interference to identify unusual radio patterns, and studies report higher detection accuracy with collaborative schemes. Cooperative schemes, where only selected nodes share information, reduce energy use. Each approach offers trade-offs between detection strength and resource efficiency [36].

Authentication protocols form another active research stream. A Software-Defined Networking (SDN) solution was proposed to improve real-time data transfer. It uses mutual authentication, pseudonyms, and velocity checks to detect cloned nodes. Tests confirmed high throughput, low delay, and resistance to replay or impersonation attacks [37]. Lightweight privacy-preserving authentication has also been explored. One protocol allows a single registration across multiple IWNs and includes efficient revocation and anonymity features. This design resists replay and impersonation attacks while keeping overhead low [38]. Fog computing has supported the development of stronger user authentication. Three-factor systems that combine a password, a smart card, and biometrics offer protection even when one factor is stolen [39,40].

Industrial deployment of authentication and trust mechanisms must account for real-world constraints, especially the limited energy, memory, and processing capacity of sensor nodes. The practicality of artificial intelligence (AI)-based cybersecurity in IWNs therefore depends on where analysis and inference are executed, and security mechanisms must balance overhead with operational performance [2]. Consequently, computation-heavy models are more realistic at cluster heads, gateways, or higher tier nodes. There, processing functions can be placed based on available compute and system constraints [8]. Feasibility is also shaped by communication overhead. Collaborative detection, feature reporting, and authentication signalling increase radio activity, which can significantly raise energy consumption and shorten node lifetime in IWNs [9]. Therefore, hierarchical designs can mitigate these costs by combining lightweight on-node screening with selective, aggregated reporting to a gateway for deeper analysis, while preserving robustness.

These studies show that security in IWNs is a multi-layered challenge. Intrusion detection enhances protection from external threats, and trust management ensures stability against internal misbehaviour. Jamming defences protect the physical layer, while authentication mechanisms safeguard user and device access. Yet, most of these works remain limited to simulations or controlled datasets, and real-world industrial validation is still missing. Another open issue is how to balance strong security with limited energy and computing resources. Mechanisms such as GANs or three-factor authentication are powerful, but they may not scale easily in resource-constrained environments. Overall, practical and standardised solutions are still needed for large-scale industrial adoption.

3.5. Time Synchronisation and Temporal Coordination (RQ3)

Recent studies have advanced time synchronisation in IWNs by focusing on accuracy, speed, scalability, and security. Koo et al. [41] proposed a control-theoretic time synchronisation protocol using sliding-mode control and proportional-integral-derivative regulation. Their approach achieves fast convergence while reducing energy consumption and remains robust even when nodes join dynamically.

Wang et al. [42] addressed the challenge of random delays by applying maximum likelihood estimation to relative clock skew. Their method improves accuracy by storing multiple timestamps in a sliding window. As a result, it outperforms both average and gradient time synchronisation protocols under noisy conditions.

To accelerate consensus-based synchronisation, Wang et al. [43] introduced the multi-hop event-triggered average consensus time synchronisation protocol. This scheme uses virtual multi-hop links to increase network connectivity. It also applies recursive least squares estimation to handle Gaussian delays and uses event-triggered updates to save energy. The results showed significantly faster convergence and reduced overhead.

A different perspective was offered by Wang et al. [44], who tailored synchronisation for mesh-star architectures. Their fast and low-overhead time synchronisation protocol splits the process into a mesh and a star layer. Mesh nodes synchronise actively, while star nodes follow passively, which lowers overhead and increases resilience to mobility.

Finally, Wang et al. [45] emphasised security. They designed the reference broadcast-based secure time synchronisation protocol. It relies on reference broadcasts and public neighbour forwarding to filter out malicious timestamps. This method protects against Sybil and manipulation attacks without relying on heavy encryption, though at the cost of a higher communication load.

Together, these works show a clear trajectory. The focus has shifted from improving synchronisation speed and accuracy to integrating scalability, energy efficiency, and resilience against cyberattacks. Despite progress, challenges remain in balancing accuracy, overhead, and security under real-world industrial conditions.

3.6. Energy Harvesting and Power Management (RQ4)

Recent research on energy harvesting and power management in IWNs has explored many strategies. Bagwari et al. [46] introduced an ML energy optimisation model that predicts node behaviour. The model dynamically adapts transmission, reception, idle, and sleep cycles. Their approach achieved over 30% energy savings across operating modes while maintaining high reliability, highlighting the potential of predictive algorithms for sustainable IWNs.

Huet et al. [47] developed a tuneable piezoelectric vibration energy harvester combined with supercapacitor storage. The system successfully powered industrial sensor nodes by converting machine vibrations into electricity. It achieved more than six hours of autonomy during vibration interruptions.

Van Leemput et al. [48] examined the integration of battery-less energy harvesting devices into multi-hop IWNs. They highlighted the issue of intermittent power supply caused by supercapacitor-based storage. To address this, they proposed three integration strategies: synchronised, ad hoc, and non-synchronised communication. Each strategy offered trade-offs between reliability, latency, and energy demands.

Mouapi and Mrad [49] focused on kinetic energy harvesting in a mining environment and combined energy prediction with cooperative energy management. Their work introduced a DL model to forecast harvested power. In addition, they introduced a hierarchical energy-balancing protocol that allowed nodes with surplus energy to support weaker ones. Experimental validation showed that all nodes maintained autonomy, compared to only 66% under older methods.

Chen et al. [50] addressed the challenge of optimising sensor activation and mobile charging scheduling in industrial wireless rechargeable sensor networks. To achieve this, they developed the joint sensor activation and charging scheduling algorithm. It integrates deep reinforcement learning with approximation techniques to optimise both sensor activity and charging routes. Simulation results showed reduced total energy consumption and improved charger utilisation compared to baseline methods.

Together, these studies reveal progression from algorithmic optimisation to hardware-based harvesting and finally to integrated system-level solutions. They emphasise the complementary roles of prediction, harvesting, storage, and charging in sustaining IWNs. The main unresolved challenges lie in managing intermittency, balancing energy among heterogeneous nodes, and ensuring long-term scalability in real deployments.

3.7. MAC Layer Protocols and Adaptive Scheduling (RQ5)

Recent studies have explored new approaches to strengthen security, trust, and scheduling mechanisms in IWNs. Khalifeh et al. [51] proposed a hybrid protocol based on the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) 802.15.4 standard [52], which switches between carrier sense multiple access and time division multiple access to improve energy efficiency and reduce packet loss. Veisi et al. [53] used SDN to enable centralised scheduling, achieving strict reliability at the cost of higher energy consumption. Ying et al. [54] introduced the concept of age of task-oriented information, optimising both sampling frequency and access selection to keep industrial data fresh.

Scalability has also been a key concern. Orozco-Santos et al. [55] improved time-slotted channel hopping (TSCH) systems that were based on SDN. In particular, they introduced virtual sinks and multiple frequency bands. This approach allowed the system to support more nodes without losing reliability. Oh et al. [56] developed the distributed adaptive communication framework with on/off switching and dual queuing for energy efficiency. This approach reduced power consumption by nearly half.

Traffic awareness has been another focus. Cheng and Sha [57] proposed the autonomous traffic-aware scheduling for IWNs. A method that allocates slots based on actual traffic loads while maintaining high reliability even under heavy data rates. Nguyen and Oh [58] designed a multichannel slotted access protocol. It avoided collisions by letting sensors select different channels and times, boosting throughput and reducing energy waste.

Optimisation methods have also been explored, with Satrya and Shin [59] applying evolutionary algorithms. They showed that genetic approaches outperform traditional scheduling methods by reducing missed deadlines and idle times. Jerbi et al. [60] improved the mobile scheduling updated TSCH protocol to better handle mobile nodes and high traffic loads. Their approach reduced delays while saving energy. Finally, Pu et al. [61] developed an age-of-information scheduling algorithm. This method guarantees that every sensor’s data stays within a strict freshness limit, strengthening safety in control systems.

Together, these works show that progress in IWNs is moving from basic hybrid MAC designs to advanced centralised, adaptive, and optimisation-driven scheduling. Another key goal is to ensure data freshness and scalability in demanding industrial environments.

3.8. Interoperability with Industrial Communication Systems (RQ6)

Interoperability between IWNs and broader industrial communication systems remains a central challenge for Industry 4.0. One line of research focuses on enabling Internet Protocol version 6 (IPv6) integration. Veena et al. [62] investigated packet delivery over the G.9959 protocol [63], offering an alternative to the widely used IEEE 802.15.4 [52]. Their method introduced channel-aware routing, packet fragmentation, and trust-based transmission. Results demonstrated higher packet delivery ratios, reduced energy consumption, and improved scalability. This approach highlights how IPv6 can be efficiently supported in IWNs, thereby facilitating compatibility with internet-native systems.

Pu et al. [64] introduced a joint architecture for semantic data exchange. The architecture integrates WIA-PA with the open platform communications unified architecture (OPC UA) publish/subscribe model via message queuing telemetry transport (MQTT). Laboratory tests confirmed high success rates, low publishing delays, and modest memory requirements. This demonstrates how middleware and semantic mapping can support cross-protocol communication while maintaining efficiency.

Together, these works illustrate complementary directions. Protocol-level mechanisms improve alignment with internet standards, while semantic and middleware frameworks enable meaningful exchange across heterogeneous industrial systems.

3.9. Routing Optimisation and Topology Control (RQ7)

Recent research on energy-aware routing, topology control, and network planning in IWNs shows a strong trend towards bio-inspired optimisation. Luo et al. [65] proposed an improved levy chaotic particle swarm optimisation for cluster routing. Their approach balanced intra-cluster distance and residual energy, achieving a 22.9% reduction in energy use and extending lifetime by nearly 14%. Similarly, Liu et al. [66] introduced a quantum elite Grey Wolf Optimisation scheme, which delayed first-node death by hundreds of rounds and reduced latency to 145 milliseconds.

Sharma et al. [67] integrated security with energy efficiency. Their meta-heuristic secure routing protocol used lightweight encryption, achieving 95.8% throughput while consuming only 0.0102 millijoules of energy. In contrast, Zhou [68] explored access control and load balancing in digital twin scenarios. They proposed a tree-chain clustered routing method that distributed workloads more evenly, thus reducing early battery depletion in critical nodes.

Other studies moved towards network-wide planning. Almuntasheri and Alenazi [69] employed SDN to choose routes based on battery status rather than path length. This doubled transmission time and prevented premature node death. Soares et al. [70] applied a positioning immune network resilient method for router placement. Their solution improved resilience by over 73% in real refinery scenarios by considering obstacles and forbidden zones. Jecan et al. [71] validated predictive energy-aware routing on real hardware. Their results showed a more than twofold increase in lifetime and predictable battery replacement cycles, bridging the gap between simulation and deployment.

Topology control has also been addressed through relay and router placement. Safiee et al. [72] studied relay node placement under budget constraints. They showed that focusing on the largest connected group minimised relay count while preserving connectivity. Similarly, Arun Mozhi Devan et al. [73] enhanced the whale optimisation algorithm for router placement. Their method improved convergence by 42% and increased client connectivity by 266% with fewer routers.

Evolutionary and meta-heuristic methods also advanced routing efficiency. Alharbi et al. [74] enhanced graph routing using covariance-matrix adaptation evolution strategy to optimise path distance, energy, and delay simultaneously. Their approach reached a 99.8% delivery ratio and balanced energy across nodes. Lin et al. [75] introduced a fuzzy harmony search for dynamic group-based routing. Their method adapted to interference, reduced overuse of bridge nodes, and improved reliability in uncertain industrial environments.

Security and resilience were addressed alongside energy goals. Singh, Raj, Rani, Khatibi, Aldeeb, Shukla, Sabry and Hassan [16] developed a protocol combining ant colony optimisation and trust-based routing, extending network lifetime by 23% while maintaining over 90% packet delivery under blackhole attacks. Wu et al. [76] focused on making cluster head selection fairer in IWNs. They introduced a jointly optimised clustering protocol based on a double-layer evolutionary algorithm. The approach improved network lifetime by 42% and achieved nearly 50% higher throughput compared to the low-energy adaptive clustering hierarchy (LEACH) protocol.

Finally, adaptive learning is emerging as a strong direction. Park et al. [77] introduced criticality-aware adaptive path learning for IWNs. This reinforcement learning framework selects paths based on their criticality. It reduced motor control settling times by 13–23% and adapted quickly to disruptions.

3.10. Real-World Deployments and Industrial Applications (RQ8)

Practical deployments of IWNs provide insights that simulations alone cannot capture. Liu et al. [78] proposed a binary tree-structured support vector machine to monitor the boundaries of spreading gas leaks. Their method reduced the number of sensors needed while still keeping accuracy high. A follow-up study by Liu et al. [79] introduced a framework called motion behaviour learning predictive tracking. This approach learns the movement of gas clouds and activates only the relevant sensors. As a result, it achieves energy savings while also improving safety.

Other works turn to continuous equipment monitoring. Ahmed et al. [80] developed an optical camera communication system for industrial valves. Small light-emitting diodes on valves transmit status information to closed-circuit television cameras. This avoids problems with radio interference and lowers deployment costs. In another direction, Ravindhar and Sasikumar [81] combined IWNs with cloud big data systems. Their platform handles monitoring, anomaly detection, and real-time alerts on a large scale. In process industries, He et al. [82] codesigned wireless networks together with estimation algorithms. Their solution accurately tracked the temperature of moving steel slabs while ensuring timely responses.

Applications also extend to supply chain and environmental monitoring. Zhao and Ding [83] applied IoT-enabled IWNs to automobile manufacturing supply chains. Their work focused on tracking resources, monitoring emissions, and supporting greener logistics. Finally, Schlichter and Wolf [84] described large-scale testbed deployments. They installed 70 sensor nodes across five industrial sites, including electroplating and machine tool factories. The study reported challenges such as dust, hardware failures, and restrictions on wireless communication.

Evidence reported in the reviewed literature suggests that real-world validation remains limited. Based on Supplementary Table S1, 56 of the 60 studies provide moderate empirical support, commonly relying on simulations, a single dataset, or small-scale laboratory demonstrations. Only 4 studies are assessed as low risk in this domain, reflecting stronger validation such as extended hardware trials or multi-site industrial deployments. These field-oriented works highlight practical constraints including reliability under harsh conditions, restrictions on wireless communication, maintenance needs, and scalability. At the same time, they demonstrate the feasibility of IWNs in Industry 4.0 through applications ranging from energy-aware sensing and predictive tracking to cloud integration and large-scale monitoring testbeds.

4. Discussion

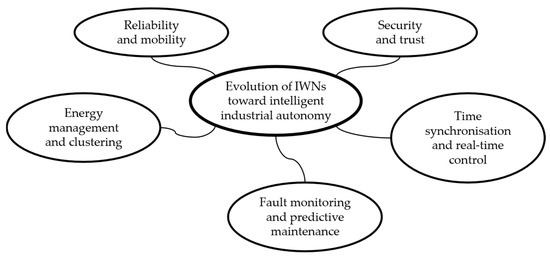

The following subsections synthesise recent contributions on IWNs along the main thematic axes identified in the review. The aim is to interpret how advances in reliability and mobility, energy management and clustering, security and trust, fault monitoring and predictive maintenance, and time synchronisation with real-time control collectively shape the readiness of IWNs for Industry 4.0.

4.1. Reliability and Mobility

As mobility becomes more common in industrial IWNs, predictive approaches are increasingly used to maintain reliability. Kim and Kim [85] showed that decision-tree-based classification and regression can anticipate mobility patterns, enabling proactive routing adjustments that reduce packet loss. These results support the broader shift from reactive to predictive reliability management and align with the view that CPSs require resilient infrastructures capable of adapting to dynamic environments.

From an architectural perspective, Duan et al. [86] examined reliability in IWNs that operate under IIoT conditions. They proposed an improved software-defined IWN framework that separates the control plane from the data plane and introduces four layers: physical, virtual, control, and application. Key sensor nodes in the physical layer are mapped to virtual nodes so that the controller can manage resources, balance load, and optimise routes based on a global view of the network. The authors combined a sleep scheduling scheme based on K-neighbourhood degree with a routing algorithm that considers both residual energy and processor load of nodes. This combination reduces unnecessary activity, spreads traffic more evenly, and mitigates node failures caused by energy depletion. Experiments using an IEEE 802.15.4 [52] network emulated with mininet and a floodlight controller showed lower node energy consumption and shorter delay compared with traditional IWNs and earlier SDN solutions.

4.2. Energy Management and Clustering

In IWNs, sustainability and network lifetime are central concerns. Conventional clustering algorithms, such as LEACH and its many variants, aimed to improve fairness in cluster head selection. However, they often struggled to scale in heterogeneous environments where nodes have different energy levels or workloads. To address this limitation, Yogarajan, Revathi and Kannan [18] proposed a hybrid multi-criteria approach that combines the analytic hierarchy process with the technique for order preference by similarity to ideal solution. This design increased network lifetime by 70% and significantly improved packet delivery. In another advancement, Duan, Fu, Li, Pace, Aloi and Fortino [17] introduced a noise-aware adaptive clustering algorithm that integrates automated guided vehicles (AGVs) as mobile relays. Their approach reduces the need for long-distance transmissions and explicitly accounts for industrial noise, which is often ignored in conventional models.

Energy management can also be addressed at the routing level in IIoT settings. A recent study defined a conceptual model for energy-aware IWNs and instantiated it in the predictive energy-aware routing (PEAR) solution [71]. The model introduces energy profiles that specify the maximum acceptable consumption for groups of field devices. These profiles enable lifetime prediction and battery replacement scheduling at the cluster level. The concept was implemented and evaluated as PEAR on a real industrial wireless testbed compliant with the ISA100.11a standard [13]. In this implementation, energy consumption is estimated from the number of transmitted and received data link protocol data units per minute. Traffic is then balanced according to the available energy margin in each device and cluster. Experimental results showed that PEAR can reduce overconsumption by a factor of 10.4 while keeping average energy use close to a baseline without energy-aware routing. In scenarios with multiple profiles, the same approach increases the lifetime of clusters with low-energy consumption by up to 3.2 times and reduces average energy consumption by more than 20%.

Overall, these contributions show that clustering has evolved into a holistic design tool for IWNs beyond energy savings. Future work should combine hybrid decision-making methods with energy harvesting to move IWNs closer to energy autonomy.

4.3. Security and Trust

IWNs are also vulnerable to jamming, intrusion, and DoS attacks. Babbar, Rani and Boulila [19] introduced a hybrid intrusion detection system that combines convolutional neural networks (CNNs) with long short-term memory (LSTM). This system achieved nearly perfect accuracy against distributed DoS attacks in smart manufacturing environments that use IWNs. Beyond technical performance, their study places cybersecurity within the Industry 5.0 paradigm, in which human–machine collaboration enhances efficiency but also expands potential attack surfaces. This perspective reinforces the conclusion that robust cybersecurity measures are essential for industrial adoption and must evolve alongside new paradigms of collaborative manufacturing.

Cauteruccio et al. [87] examined trust and influence in interacting IoT systems. They introduced the concept of the scope of a smart object, understood as the range over which the object and its data are relevant. The paper proposed two formalisations, naive scope and refined scope. Both are based on a graph model of multiple interacting IoT systems and rely on metadata to keep the model independent from underlying technologies. Refined scope incorporates trust degree, which measures how many transactions sent by a node are requested, reposted, or elaborated by its neighbours, and the proactivity degree, which reflects how often a node forwards or elaborates received transactions. The model also introduces a security level for each instance and a security requirement degree that captures how security constraints affect information propagation. Experiments on simulated networks with multiple IoT systems show that scope remains well balanced relative to diffusion and influence degrees.

4.4. Fault Monitoring and Predictive Maintenance

Although simulation-based proposals still dominate much of the literature, recent work begins to bridge theory and practice. Rao et al. [88] developed an IoT model with edge, fog, and device layers, forming a hybrid architecture that combines edge and cloud resources for industrial fault detection. Lightweight models at the edge provide immediate responses, while CNN-LSTM models in the cloud sustain long-term accuracy and reliability. Their results showed that scalable deployments are now feasible when suitable datasets are available, suggesting that the gap between laboratory prototypes and industrial rollouts is starting to narrow.

Mourtzis et al. [89] presented an IoT platform for remote monitoring and predictive maintenance of cold chain refrigeration and storage systems. It targets refrigerators and cold storage units whose failures increase energy consumption and jeopardise the quality of perishable goods. The framework employs IWNs and a custom data acquisition device to retrofit existing units with temperature, humidity, barometric pressure, and air quality sensors. Sensor nodes transmit measurements over wireless fidelity (Wi-Fi) to a cloud platform. Engineers interact with a web interface to inspect current and historical operating conditions and receive notifications when malfunctions are detected. The authors present this implementation as a foundation for predictive maintenance functions. These functions will estimate the remaining useful life of critical components and deliver maintenance instructions through augmented reality interfaces. Taken together, the proposed system shows how wireless monitoring, cloud services, and visualisations tailored to users can be combined into a practical tool for maintenance support in an Industry 4.0 setting.

4.5. Time Synchronisation and Real-Time Control

Synchronisation continues to be a foundational requirement for industrial automation. Earlier studies pointed to consensus protocols and secure timestamping as key mechanisms. However, Rusu, Dobra, Hulea and Miron [20] demonstrated that commercial solutions can now achieve sub-millisecond drift using IEEE 802.15.4-2020 [52] in TSCH mode. Their algorithm validated that wireless process control, can meet timing constraints previously reserved for wired systems. Future studies should evaluate such synchronisation methods under large-scale, noisy, and security-critical deployments to ensure scalability and resilience.

Nuratch [90] examined real-time monitoring and control from the perspective of an IIoT device to cloud gateway. The work presented a gateway implemented on a 16-bit microcontroller that connects traditional industrial sensors, actuators, and Modbus devices to a cloud system. The firmware uses interrupt-driven real-time multitasking to serve all required tasks on time. It also manages communication between the gateway and the cloud through an onboard Wi-Fi module. On top of this wireless link, the system uses the websocket protocol to maintain a persistent bidirectional connection. Experimental web applications show that this setup supports monitoring and control through a web browser. They also demonstrate real-time exchange of measurements and commands between field devices and the cloud in industrial automation scenarios.

4.6. Research Gaps and Future Directions

Despite promising advances, several gaps remain. First, AI methods need validation in heterogeneous, real-world deployments rather than controlled testbeds. Second, clustering and routing must account for both mobility and noise, integrating AGVs, unmanned aerial vehicles, and other mobile relays into scalable frameworks. Third, cybersecurity should evolve towards lightweight, explainable AI to ensure trust and transparency in Industry 5.0. Fourth, hybrid edge-cloud architectures must integrate predictive maintenance with interoperability standards to ease deployment. Finally, time synchronisation should be explored not only for small-scale cells but also for large-scale, multi-factory deployments where latency, scalability, and resilience intersect.

In addition, a cross-layer research gap is the limited treatment of the coupling between cybersecurity mechanisms, energy consumption, and end-to-end latency. Security mechanisms such as intrusion detection and trust modelling improve robustness against jamming, intrusion, and DoS behaviours. However, they can increase communication and processing overhead, raising energy consumption and potentially adding delay to time-critical traffic [19,87]. Conversely, energy-optimised solutions extend lifetime but may increase end-to-end latency or reduce the monitoring granularity required for timely detection and response [18,71,86]. This interaction becomes especially important for deterministic scheduling and real-time control, where tight synchronisation and bounded channel occupancy are essential. Recent TSCH-based results confirm that wireless control can achieve strict timing. However, these results also imply that any additional control and security overhead must be engineered carefully so that latency constraints are not violated [20,90].

Figure 4 summarises how recent work is shifting IWNs from monitoring-oriented prototypes toward intelligent, increasingly autonomous industrial communication systems.

Figure 4.

Conceptual summary of the recent advances in IWNs.

Collectively, advances across these axes improve predictability, energy efficiency, and security, positioning IWNs as a core enabler of Industry 4.0 and a stepping stone toward the human-centric vision of Industry 5.0.

5. Conclusions

This systematic review synthesised 60 recent studies on IWNs. It assesses how progress is distributed across key Industry 4.0 requirements, including reliability, security, time synchronisation, energy management, networking and interoperability, and experimental validation. By organising the evidence within a unified comparative structure, the review enables consistent comparison across heterogeneous proposals and clarifies where the field is converging towards deployable IWNs solutions.

Three overarching findings emerge. First, reliability engineering is shifting from redundancy-dominated designs towards predictive and adaptive strategies. In particular, learning-based mobility awareness and dynamic routing are increasingly used to reduce packet loss and improve robustness. Second, security is shifting from static protection schemes to multi-layer approaches. These increasingly incorporate trust management, intrusion and anomaly detection, and context-aware mechanisms to address the expanding attack surface of connected industrial systems. Third, time synchronisation and deterministic scheduling are maturing, and wireless solutions can increasingly approach timing guarantees traditionally associated with wired industrial control. This progress expands feasible use cases from monitoring to closed-loop control.

From a scientific and practical standpoint, this review provides a structured synthesis that consolidates fragmented advances into a coherent picture of IWNs readiness for Industry 4.0. It also offers an empirical gap map explaining why widespread adoption remains uneven. Key barriers include limited energy autonomy, incomplete support for mobility and harsh environments, persistent challenges in cross-layer interoperability, and a continued shortage of large-scale real-world validation and standardised benchmarking. Collectively, these issues sustain a deployment gap between algorithmic innovation and performance under realistic industrial constraints.

The findings should be interpreted in light of the selected search scope and time window. In many topics, the available evidence base remains predominantly simulation based or derived from small testbeds. Therefore, the synthesis reflects published research trends rather than a meta-analytic quantification of effect sizes across comparable industrial deployments.

Future work should prioritise multi-site field deployments and shared benchmarks to improve reproducibility. It should also focus on integrated system designs that combine energy harvesting, power management, and networking for scalable autonomy. In addition, mobility aware and noise aware frameworks are needed to support mobile relays without sacrificing stability. Research should further develop lightweight and security mechanisms that support trust and operational transparency. Finally, scalable synchronisation and scheduling should be validated under interference, adversarial conditions, and deployment across multiple factories. Addressing these needs is essential for translating current advances into robust, interoperable IWNs infrastructures for Industry 4.0 and the emerging Industry 5.0 landscape.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jsan15010007/s1, Table S1: Risk of Bias Assessment of Studies on Industrial Wireless Sensor and Actuator Networks.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, C.T., P.P., D.P. and R.A.M.; methodology, C.T., P.P., D.P. and R.A.M.; validation, C.T., P.P., D.P. and R.A.M.; formal analysis, C.T., P.P., D.P. and R.A.M.; investigation, C.T., P.P., D.P. and R.A.M.; resources, C.T.; data curation, C.T.; writing—original draft preparation, C.T.; writing—review and editing, C.T., P.P., D.P. and R.A.M.; visualisation, C.T., P.P., D.P. and R.A.M.; supervision, P.P., D.P. and R.A.M.; project administration, C.T., P.P., D.P. and R.A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data analysed in this study were obtained from the Scopus database through the query described in Section 2.2. Access to Scopus requires an institutional or individual subscription at https://www.scopus.com (accessed on 1 September 2025). No new data were created in this study.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support of the University of West Attica for providing access to the Scopus database through the institutional OpenVPN service.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AGV | Automated Guided Vehicle |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| CPS | Cyber Physical System |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| DoS | Denial of Service |

| GAN | Generative Adversarial Network |

| IEEE | Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers |

| IIoT | Industrial Internet of Things |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| IP | Internet Protocol |

| ISA | International Society of Automation |

| IWN | Industrial Wireless Network |

| IWSAN | Industrial Wireless Sensor and Actuator Network |

| IWSN | Industrial Wireless Sensor Network |

| LEACH | Low-Energy Adaptive Clustering Hierarchy |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| MAC | Media Access Control |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| MQTT | Message Queuing Telemetry Transport |

| OPC UA | Open Platform Communications Unified Architecture |

| PEAR | Predictive Energy-Aware Routing |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| RQ | Research Question |

| SDN | Software-Defined Networking |

| TSCH | Time-Slotted Channel Hopping |

| WIA-PA | Wireless Networks for Industrial Automation—Process Automation |

| Wi-Fi | Wireless Fidelity |

| Wireless HART | Wireless Highway Addressable Remote Transducer |

| WSAN | Wireless Sensor and Actuator Network |

| WSN | Wireless Sensor Network |

References

- Majid, M.; Habib, S.; Javed, A.R.; Rizwan, M.; Srivastava, G.; Gadekallu, T.R.; Lin, J.C.W. Applications of Wireless Sensor Networks and Internet of Things Frameworks in the Industry Revolution 4.0: A Systematic Literature Review. Sensors 2022, 22, 2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güngör, V.C.; Hancke, G.P. Industrial wireless sensor networks: Challenges, design principles, and technical approaches. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2009, 56, 4258–4265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Lu, Y.; Vogel-Heuser, B.; Wang, L. Industry 4.0 and Industry 5.0—Inception, conception and perception. J. Manuf. Syst. 2021, 61, 530–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahavandi, S. Industry 5.0—A human-centric solution. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddikunta, P.K.R.; Pham, Q.V.; Boopathy, P.; Deepa, N.; Dev, K.; Gadekallu, T.R.; Ruby, R.; Liyanage, M. Industry 5.0: A survey on enabling technologies and potential applications. J. Ind. Inf. Integr. 2022, 26, 100257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, S.; Faheem, M.; Guenes, M. Industrial wireless sensor and actuator networks in industry 4.0: Exploring requirements, protocols, and challenges—A MAC survey. Internet J. Commun. Syst. 2019, 32, e4074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotaibi, B. A Survey on Industrial Internet of Things Security: Requirements, Attacks, AI-Based Solutions, and Edge Computing Opportunities. Sensors 2023, 23, 7470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichstädt, S.; Gruber, M.; Vedurmudi, A.P.; Seeger, B.; Bruns, T.; Kok, G. Toward smart traceability for digital sensors and the industrial internet of things. Sensors 2021, 21, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantazis, N.A.; Nikolidakis, S.A.; Vergados, D.D. Energy-efficient routing protocols in wireless sensor networks: A survey. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2013, 15, 551–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yetgin, H.; Cheung, K.T.K.; El-Hajjar, M.; Hanzo, L. A Survey of Network Lifetime Maximization Techniques in Wireless Sensor Networks. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2017, 19, 828–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Saifullah, A.; Li, B.; Sha, M.; González, H.; Gunatilaka, D.; Wu, C.; Nie, L.; Chen, Y. Real-Time Wireless Sensor-Actuator Networks for Industrial Cyber-Physical Systems. Proc. IEEE 2016, 104, 1013–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somappa, A.A.; Øvsthus, K.; Kristensen, L.M. An industrial perspective on wireless sensor networks—A survey of requirements, protocols, and challenges. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2014, 16, 1391–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ANSI/ISA-100.11a-2011; Wireless Systems for Industrial Automation: Process Control and Related Applications. International Society of Automation (ISA): Research Triangle Park, NC, USA, 2011.

- Åkerberg, J.; Gidlund, M.; Björkman, M. Future Research Challenges in Wireless Sensor and Actuator Networks Targeting Industrial Automation. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Industrial Informatics (INDIN), Lisbon, Portugal, 26–29 July 2011; pp. 410–415. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, A.K.; Kumar, A. The Smart Analysis of Prolong Lifetime in Industrial Wireless Sensor Networks. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Distributed Computing and Electrical Circuits and Electronics (ICDCECE), Bangalore, India, 28–29 April 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A.; Raj, A.; Rani, P.; Khatibi, A.; Aldeeb, H.; Shukla, P.K.; Sabry, A.; Hassan, M.M. Resilient wireless sensor networks in industrial contexts via energy-efficient optimization and trust-based secure routing. Peer-to-Peer Netw. Appl. 2025, 18, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Fu, T.; Li, L.; Pace, P.; Aloi, G.; Fortino, G. AGV-Integrated Noise-Aware Adaptive Clustering for Industrial Wireless Sensor Networks in smart factories. Ad Hoc Netw. 2025, 177, 103906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yogarajan, G.; Revathi, T.; Kannan, A.S.K. A Hybrid Multicriteria Decision-Making Algorithm for Energy-Efficient Clustering in Industrial Wireless Sensor Networks. Internet Technol. Lett. 2025, 8, e70030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babbar, H.; Rani, S.; Boulila, W. Fortifying the Connection: Cybersecurity Tactics for WSN-Driven Smart Manufacturing in the Era of Industry 5.0. IEEE Open J. Commun. Soc. 2025, 6, 3417–3428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusu, A.; Dobra, P.; Hulea, M.; Miron, R. Time Management in Wireless Sensor Networks for Industrial Process Control. Algorithms 2025, 18, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alryalat, S.A.S.; Malkawi, L.W.; Momani, S.M. Comparing bibliometric analysis using pubmed, scopus, and web of science databases. J. Vis. Exp. 2019, 2019, e58494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pech, G.; Delgado, C. Assessing the publication impact using citation data from both Scopus and WoS databases: An approach validated in 15 research fields. Scientometrics 2020, 125, 909–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidari, A.; Amiri, Z.; Jabraeil Jamali, M.A.J.; Jafari Navimipour, N. Assessment of reliability and availability of wireless sensor networks in industrial applications by considering permanent faults. Concurr. Comput. Pract. Exp. 2024, 36, e8252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, G.; Chanak, P. An Intelligent Fault Tolerant Data Routing Scheme for Wireless Sensor Network-Assisted Industrial Internet of Things. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2023, 19, 5543–5553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, G.; Chanak, P.; Bhattacharya, M. Obstacle-Aware Intelligent Fault Detection Scheme for Industrial Wireless Sensor Networks. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2022, 18, 6876–6886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, H.; Dorneanu, B.; Arellano-García, H.; Xiao, P.; Zhang, L. Deep Learning-Based Fault Prediction in Wireless Sensor Network Embedded Cyber-Physical Systems for Industrial Processes. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 10867–10879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabella, G.; Ciuonzo, D.; Paltrinieri, N.; Salvo Rossi, P.S. Bayesian Fault Detection and Localization Through Wireless Sensor Networks in Industrial Plants. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 11, 13231–13246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, S. Angle Based Critical Nodes Detection (ABCND) for Reliable Industrial Wireless Sensor Networks. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 2023, 130, 757–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, H.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, B.; Gao, Q. Cascading Failure Analysis of Hierarchical Industrial Wireless Sensor Networks under the Impact of Data Overload. Machines 2022, 10, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Quayed, F.; Ahmad, Z.; Humayun, M. A Situation Based Predictive Approach for Cybersecurity Intrusion Detection and Prevention Using Machine Learning and Deep Learning Algorithms in Wireless Sensor Networks of Industry 4.0. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 34800–34819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Embarak, O.H.; Zitar, R.A. Securing wireless sensor networks against dos attacks in industrial 4.0. J. Intell. Syst. Internet Things 2023, 8, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dontu, S.; Vallabhaneni, R.; Addula, S.R.; Kumar Pareek, P.; Hussein, R.R. Enhanced Adaptive Butterfly Optimizer based Feature Selection for Protecting the Data in Industry based WSN. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Intelligent Algorithms for Computational Intelligence Systems (IACIS), Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 21–23 March 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.; Yang, S.X.; Li, Y.; Lu, Y.; Guo, T. Generative Adversarial Learning for Trusted and Secure Clustering in Industrial Wireless Sensor Networks. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2023, 70, 8377–8387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Quadri, Q.N.; Lasisi, A.; Kaushik, S.; Kumar, S. A Multi-Layered Assessment System for Trustworthiness Enhancement and Reliability for Industrial Wireless Sensor Networks. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 2024, 137, 1997–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortés-Leal, A.; Del-Valle-Soto, C.; Cardenas, C.; Valdivia, L.J.; Del-Puerto-Flores, J.A. Performance metric analysis for a jamming detection mechanism under collaborative and cooperative schemes in industrial wireless sensor networks. Sensors 2022, 22, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, P.K.; Bhattacharya, A. SDIWSN: A Software-Defined Networking-Based Authentication Protocol for Real-Time Data Transfer in Industrial Wireless Sensor Networks. IEEE Trans. Netw. Serv. Manag. 2022, 19, 3465–3477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, L.; Peng, T.; Li, F.; Zeng, S.; Wu, H. Privacy-Preserving Authentication Scheme With Revocability for Multi-WSN in Industrial IoT. IEEE Syst. J. 2023, 17, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, S.S.; Mohanty, S.; Majhi, B. An efficient three-factor user authentication scheme for industrial wireless sensor network with fog computing. Internet J. Commun. Syst. 2022, 35, e5028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, K.; Saleem, M.A.; Ghaffar, Z.; Shamshad, S.; Das, A.K.; Alenazi, M.J.F. Robust and efficient three-factor authentication solution for WSN-based industrial IoT deployment. Internet Things 2024, 28, 101372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, Y.C.; Mahyuddin, M.N.; Ab Wahab, M.N.A. Novel Control Theoretic Consensus-Based Time Synchronization Algorithm for WSN in Industrial Applications: Convergence Analysis and Performance Characterization. IEEE Sens. J. 2023, 23, 4159–4175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yong, T.; Song, X.; Sun, D. Maximum Likelihood Estimation of Relative Clock Skew for Distributed Time Synchronization in Industrial Wireless Sensor Networks. IEEE Sens. J. 2023, 23, 31359–31367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zou, Y.; Liu, X.; Li, M. A Fast Convergence Scheme for Distributed Consensus Time Synchronization Using Multihop Virtual Links in Industrial Wireless Sensor Networks. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 20009–20017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yong, T.; Song, X. Fast and Low-Overhead Time Synchronization for Industrial Wireless Sensor Networks with Mesh-Star Architecture. Sensors 2023, 23, 3792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Sun, D.; Yu, C. Reference Broadcast-Based Secure Time Synchronization for Industrial Wireless Sensor Networks. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 9223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagwari, A.; Logeshwaran, J.; Usha, K.; Raju, K.; Alsharif, M.H.; Uthansakul, P.; Uthansakul, M. An Enhanced Energy Optimization Model for Industrial Wireless Sensor Networks Using Machine Learning. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 96343–96362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huet, F.; Boitier, V.; Séguier, L. Tunable Piezoelectric Vibration Energy Harvester With Supercapacitors for WSN in an Industrial Environment. IEEE Sens. J. 2022, 22, 15373–15384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Leemput, D.; Hoebeke, J.; de Poorter, E. Integrating Battery-Less Energy Harvesting Devices in Multi-Hop Industrial Wireless Sensor Networks. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2024, 62, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouapi, A.; Mrad, H. Energy Prediction and Energy Management in Kinetic Energy-Harvesting Wireless Sensors Network for Industry 4.0. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 7298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Yi, C.; Wang, R.; Zhu, K.; Cai, J. A Joint Optimization of Sensor Activation and Mobile Charging Scheduling in Industrial Wireless Rechargeable Sensor Networks. In Proceedings of the Conference Record—International Conference on Communications, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 16–20 May 2022; pp. 3568–3573. [Google Scholar]

- Khalifeh, A.; Tanash, R.; AlQudah, M.; Al-Agtash, S. Enhancing energy efficiency of IEEE 802.15.4- based industrial wireless sensor networks. J. Ind. Inf. Integr. 2023, 33, 100460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEEE Std 802.15.4-2020; IEEE Standard for Low-Rate Wireless Networks. IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020.

- Veisi, F.; Montavont, J.; Theoleyre, F. Enabling Centralized Scheduling Using Software Defined Networking in Industrial Wireless Sensor Networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023, 10, 20675–20685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, C.; Zhao, Z.; Yi, C.; Shi, Y.; Cai, J. An AoTI-Driven Joint Sampling Frequency and Access Selection Optimization for Industrial Wireless Sensor Networks. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2023, 72, 12311–12325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orozco-Santos, F.; Sempere, V.; Silvestre, J.; Vera-Perez, J. Scalability Enhancement on Software Defined Industrial Wireless Sensor Networks Over TSCH. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 107137–107151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.; Lee, D.; Lakew, D.S.; Cho, S. DACODE: Distributed adaptive communication framework for energy efficient industrial IoT-based heterogeneous WSN. ICT Express 2023, 9, 1085–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Sha, M. Autonomous Traffic-Aware Scheduling for Industrial Wireless Sensor-Actuator Networks. ACM Trans. Sens. Netw. 2023, 19, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.; Oh, H. A Smart Multichannel Slotted Sense Multiple Access Protocol for Industrial Wireless Sensor Networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 12460–12471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satrya, G.B.; Shin, S.Y. Evolutionary computing approach to optimize superframe scheduling on industrial wireless sensor networks. J. King Saud Univ. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2022, 34, 706–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerbi, W.; Cheikhrouhou, O.; Guermazi, A.; Hafedh, H. An enhanced MSU-TSCH scheduling algorithms for industrial wireless sensor networks. Concurr. Comput. Pract. Exp. 2024, 36, e7938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, C.; Yang, H.; Wang, P.; Dong, C. AoI-Bounded Scheduling for Industrial Wireless Sensor Networks. Electronics 2023, 12, 1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]