Abstract

Upper-limb motor impairment is a major consequence of stroke and neuromuscular disorders, imposing a sustained clinical and socioeconomic burden worldwide. Quantitative assessment of limb positioning and motion accuracy is fundamental to rehabilitation, guiding therapy evaluation and robotic assistance. The evolution of upper-limb positioning systems has progressed from optical motion capture to wearable inertial measurement units (IMUs) and, more recently, to data-driven estimators integrated with rehabilitation robots. Each generation has aimed to balance spatial accuracy, portability, latency, and metrological reliability under ecological conditions. This review presents a systematic synthesis of the state of measurement uncertainty, calibration, and traceability in upper-limb rehabilitation robotics. Studies are categorised across four layers, i.e., sensing, fusion, cognitive, and metrological, according to their role in data acquisition, estimation, adaptation, and verification. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) protocol was followed to ensure transparent identification, screening, and inclusion of relevant works. Comparative evaluation highlights how modern sensor-fusion and learning-based pipelines achieve near-optical angular accuracy while maintaining clinical usability. Persistent challenges include non-standard calibration procedures, magnetometer vulnerability, limited uncertainty propagation, and absence of unified traceability frameworks. The synthesis indicates a gradual transition toward cognitive and uncertainty-aware rehabilitation robotics in which metrology, artificial intelligence, and control co-evolve. Traceable measurement chains, explainable estimators, and energy-efficient embedded deployment emerge as essential prerequisites for regulatory and clinical translation. The review concludes that future upper-limb systems must integrate calibration transparency, quantified uncertainty, and interpretable learning to enable reproducible, patient-centred rehabilitation by 2030.

1. Introduction

Motor impairment of the upper limb is one of the most common consequences of stroke and neuromuscular disorders. It severely affects activities of daily living and imposes a persistent clinical and socioeconomic burden at the global level. Stroke remains a leading cause of long-term disability, and epidemiological studies indicate that tens of millions of survivors live with residual motor deficits. Upper-limb impairment is observed in most acute cases and often persists for several months after onset [1,2,3]. Quantitative assessment of movement accuracy is essential for rehabilitation effectiveness as it provides objective information on functional recovery, supports therapist decisions, and determines the calibration of robotic assistance systems. In this context, positioning accuracy is a critical factor governed by clinical and control thresholds. For instance, root mean square error (RMSE) values for elbow and humerothoracic joint angles are typically expected to remain within approximately 5° for reliable assessment and closed-loop interaction, while acceptable end-to-end latency is generally below 100 ms for assist-as-needed control. Moreover, reproducible calibration and bounded uncertainty are necessary to enable regulated use [4,5,6,7,8,9]. These quantitative criteria motivate this survey and form the basis for the comparisons presented throughout this paper.

Optical motion-capture systems, such as Vicon and Optotrak, have long been regarded as the reference standard for kinematic measurement [10,11,12]. They achieve sub-millimetre spatial precision through multi-camera triangulation of reflective markers [11,12]. From a measurement-principle perspective, optical systems infer segment orientations from reconstructed marker trajectories, and joint-angle accuracy is primarily governed by camera calibration quality, marker placement, and line-of-sight visibility [11,12,13]. In upper-limb biomechanics, soft-tissue artefacts and marker occlusions introduce joint-dependent errors [13,14,15], with increased sensitivity at the scapulothoracic and glenohumeral levels due to complex anatomical motion and skin movement [14,15]. However, their dependence on controlled laboratory environments, costly infrastructure, and complex calibration procedures limits their applicability in clinical and home-based contexts [10,11].

The emergence of micro-electromechanical inertial measurement units (IMUs), which integrate tri-axial accelerometers, gyroscopes, and magnetometers, introduced a paradigm shift towards portable and cost-effective motion tracking [16,17,18]. Inertial sensing estimates orientation through angular-rate integration and gravity-referenced inclination, while magnetometers provide heading information when the magnetic field is reliable [16,17,19]. Consequently, angle accuracy is influenced by gyroscope bias accumulation, sensitivity to dynamic accelerations, and magnetic disturbances [20,21], which become more pronounced during fast movements, long-duration tasks, or in magnetically perturbed environments [20,22]. Supported by advanced sensor-fusion algorithms, IMU-based systems can estimate upper-limb joint angles with mean errors below 4° when compared with optical benchmarks [23,24,25]. Nevertheless, estimation accuracy at scapulothoracic and glenohumeral joints remains affected by soft-tissue artifacts and magnetic disturbances [14,15,20,26]. Large-scale deployment further depends on calibration repeatability, magnetically robust heading estimation or magnetometer-free pipelines, and explicit uncertainty reporting, which remain inconsistently addressed in current research [22,23,27].

The increasing integration of wearable sensing with artificial intelligence (AI) has significantly transformed upper-limb kinematic estimation [4,28,29]. Deep temporal architectures such as convolutional long short-term memory (CNN–LSTM) and bidirectional long short-term memory (BiLSTM) networks have demonstrated the ability to reconstruct joint trajectories from minimal IMU arrays while maintaining clinically acceptable accuracy [4,28,30]. In this study, AI-driven modeling refers to estimators that learn mappings from multimodal time series (IMU, electromyography (EMG), vision, or encoders) to states or intent through parameterized function classes (for example, convolutional, recurrent, or transformer-based models) [29,31,32]. These models are trained using supervised, self-supervised, or distillation objectives and expose calibrated uncertainty or interpretability indicators that can be propagated to control [33,34]. In contrast, traditional estimation relies on mechanistic models and Bayesian filters such as complementary or extended Kalman filters on with explicitly defined noise models and observability assumptions [19,35,36]. Learning-based estimators enable adaptive control in robotic exoskeletons and assistive manipulators and form the foundation of cognitive rehabilitation robotics, where robots interpret user intention, learn from human motion, and adjust their control policy in real time [9,34,37]. For clinical translation, such cognitive systems must be traceable, with documented calibration chains and quantifiable uncertainty [24,27,38].

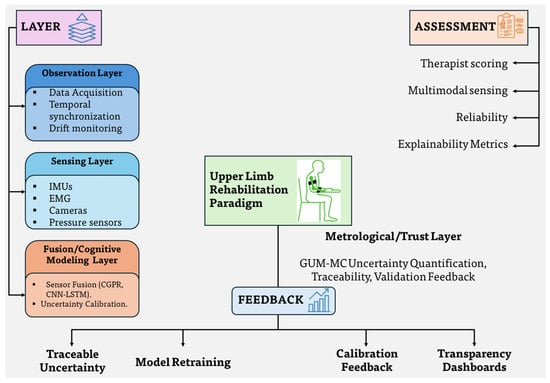

Problem framing and taxonomy: To organize the heterogeneous literature, a four-layer taxonomy is adopted that spans the entire sensing-to-intervention pipeline:

- Sensing layer: body-worn IMUs, EMG, encoders, and vision systems; placement and calibration procedures.

- Fusion layer: complementary and extended Kalman filters, magnetometer-free variants, biomechanical constraints, and uncertainty propagation using the Guide to the Expression of Uncertainty in Measurement (GUM) and the GUM Monte Carlo (GUM–MC) method.

- Cognitive layer: learning models for kinematics and intent that incorporate interpretability and calibration through confidence intervals and conformal bounds.

- Metrological layer: standards, repeatability, uncertainty budgets, and traceability linking device calibration to clinical performance metrics.

This taxonomy supports the comparative framework and clarifies where accuracy, uncertainty, and energy constraints appear across the processing pipeline.

Figure 1 illustrates the conceptual evolution of upper-limb rehabilitation technologies across four stages: clinical observation, wearable sensing, AI-driven modeling, and cognitive rehabilitation robotics. Each stage differs in its assessment and feedback mechanisms. Clinical observation relies primarily on therapist-evaluated functional scales, whereas wearable sensing employs IMUs, EMG, or camera-based systems for continuous data collection. AI-driven modeling introduces deep-learning frameworks that transform multimodal signals into interpretable motion features, while cognitive robotics integrates co-adaptive control and intent recognition to close the therapeutic feedback loop. This transition represents the gradual progression from subjective evaluation to intelligent and data-centric rehabilitation. In this work, Figure 1 is structured to align with the taxonomy above, with annotations for each layer and representative accuracy (<5°), latency (<100 ms), and uncertainty sources such as bias, heading, and soft-tissue effects.

Figure 1.

Conceptual progression of upper-limb rehabilitation technologies across sensing, fusion, cognitive, and metrological layers with indicative accuracy (≤) and latency (≤100 ms) targets.

Several technical challenges continue to limit reproducibility and cross-study comparability. IMU drift, magnetic interference, non-standardized sensor-to-segment calibration, and the absence of unified uncertainty quantification protocols remain critical barriers to clinical translation [27]. Furthermore, limited interoperability among sensing platforms and the lack of traceable calibration standards constrain the metrological reliability required for regulated clinical deployment. From a systems perspective, the key gap lies in developing a traceability-aware AI framework that provides calibrated confidence in kinematic and intent estimation, links these confidences to control envelopes such as stiffness or rate limits, and reports uncertainty metrics alongside clinical outcomes. Table 1 summarizes the chronological evolution of these technologies, highlighting major advancements and limitations from the 1990s to the present decade. Subsequent sections address these challenges through quantitative comparisons of accuracy, latency, and uncertainty propagation.

Table 1.

Evolution of upper-limb positioning technologies for rehabilitation.

Accordingly, this review provides a systematic synthesis of research on upper-limb positioning for rehabilitation robotics, encompassing the complete spectrum from wearable sensing to cognitive robotic adaptation. The analysis follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) methodology to ensure transparent study identification, screening, eligibility evaluation, and inclusion. The objectives are to (i) trace the evolution of sensing and positioning paradigms from optical to intelligent wearable systems, (ii) analyze computational pipelines for joint-angle estimation and adaptive robotic control, (iii) evaluate calibration, accuracy, and uncertainty-management strategies, and (iv) identify open challenges and future directions towards standardized and explainable upper-limb rehabilitation frameworks. Distinct from prior surveys, the present contribution introduces a unifying taxonomy and a traceability-oriented synthesis that integrates accuracy and latency targets with uncertainty budgets and control constraints, providing benchmarks for clinical and home-based applications.

To align the systematic review with the metrological objectives, five research questions (RQs) guide the analysis:

- RQ1

- What methodologies and sensing configurations are currently employed for upper-limb positioning in rehabilitation robotics, and how do they balance accuracy, latency, and ecological validity?

- RQ2

- How do intelligent or learning-based estimation frameworks improve joint-angle reconstruction and uncertainty management compared with traditional fusion algorithms?

- RQ3

- What technical and metrological limitations restrict reproducibility, calibration repeatability, and cross-study comparability in upper-limb kinematic assessment?

- RQ4

- Which methodological strategies, such as uncertainty propagation, standardization, and explainable AI can enhance traceable control and ensure reliability?

- RQ5

- What datasets, benchmarks, and validation protocols are required to enable large-scale, traceable, and clinically transferable upper-limb rehabilitation systems?

These research questions define the structure of the subsequent sections and form the conceptual basis for the PRISMA-guided synthesis described in Section 2. Specifically, RQ1 informed the categorization of sensing modalities and placement strategies, RQ2 guided the comparative analysis of traditional and learning-based estimation pipelines, and RQ3 shaped the identification of calibration, uncertainty, and reproducibility gaps. RQ4 directed the synthesis of traceability, explainability, and uncertainty-propagation strategies relevant to robotic control, while RQ5 structured the evaluation of datasets, benchmarks, and validation protocols required for large-scale clinical translation.

2. PRISMA Approach

This review follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA 2020) to ensure transparent identification, screening, eligibility assessment, and inclusion. The methodology is consistent with the four-layer taxonomy described in this paper, encompassing sensing, fusion, cognitive, and metrological layers. The five research questions (RQ1–RQ5) were used as analytical anchors throughout the review process, guiding eligibility criteria definition, data extraction, and thematic synthesis. The protocol was not preregistered; all steps, decision rules, and extracted variables are explicitly reported to support reproducibility.

Eligibility criteria: Primary studies and reviews were eligible if they (i) reported quantitative positioning or kinematic outcomes for the upper limb, such as joint-angle root mean square error (RMSE), orientation error, or latency; (ii) provided validation against a reference system, including optical motion capture, robot encoders, or benchmark datasets, or contained an explicit calibration or uncertainty analysis; and (iii) addressed robotic rehabilitation devices, exoskeletons, assistive manipulators, or wearable sensing systems relevant to robotic control. These criteria were formulated to ensure direct alignment with RQ1 and RQ3, prioritizing studies that reported accuracy, latency, calibration procedures, and uncertainty-related metrics. Editorials and narrative articles without quantitative data, clinical studies lacking instrumented kinematics, and investigations unrelated to the upper limb were excluded.

Information sources and search strategy: Comprehensive searches were conducted in Scopus, IEEE Xplore, ScienceDirect, and PubMed. The queries combined controlled vocabulary and keywords representing the review scope: (upper limb OR arm) AND (rehabilitation OR robotic OR exoskeleton) AND (measurement OR metrology OR uncertainty OR calibration OR IMU OR “sensor fusion”). The time window covered the period from 1999 to 2025, restricted to English-language publications. Reference lists of included papers and related surveys were manually inspected to identify additional records.

Selection process: All retrieved records were imported into a reference manager for automatic deduplication. A two-stage screening was performed through a web-based interface, first on title and abstract, followed by full-text review. Two reviewers independently applied the eligibility criteria at each stage. Disagreements were resolved through discussion. Inter-rater agreement for full-text inclusion was , indicating strong concordance. Decision rules prioritized the presence of quantitative positioning metrics, explicit calibration or uncertainty treatment, and direct relevance to robotic rehabilitation.

Data items and collection: For each study, the following items were extracted: sensing modality and configuration, calibration method (anatomical, functional, or landmark-free) and reference system, fusion or estimation algorithm, accuracy metrics by joint (for example, RMSE), latency or throughput, and computational or energy profile where available. These variables were selected to support comparative analysis aligned with RQ1 and RQ2, while extracted uncertainty descriptors and calibration details addressed RQ3 and RQ4. Treatment of uncertainty, including Type A and Type B components, GUM, GUM–MC, and prediction intervals, was also recorded.

Risk of bias and quality appraisal: Because most included studies are measurement or validation oriented rather than focused on clinical effectiveness, the risk of bias was evaluated using a measurement-centric checklist derived from the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (QUADAS-2) framework. The checklist incorporated domains of applicability, reference standard, and flow and timing, together with metrological reporting items covering calibration traceability, repeatability, and uncertainty statements. Each item was rated as low, unclear, or high risk, with justifications documented in the extraction sheet.

Synthesis methods: Quantitative results were summarized by sensing modality and algorithmic category. Heterogeneity in experimental tasks, joints, performance metrics, and reporting procedures precluded meta-analysis. The narrative synthesis was explicitly structured according to the research questions, progressing from sensing configurations (RQ1), to estimation and learning strategies (RQ2), to metrological limitations and uncertainty handling (RQ3–RQ4), and finally to dataset, benchmark, and validation requirements for scalable deployment (RQ5). When uncertainty components were available, propagation approaches using GUM or GUM–MC were synthesized and related to controller-relevant uncertainty bounds.

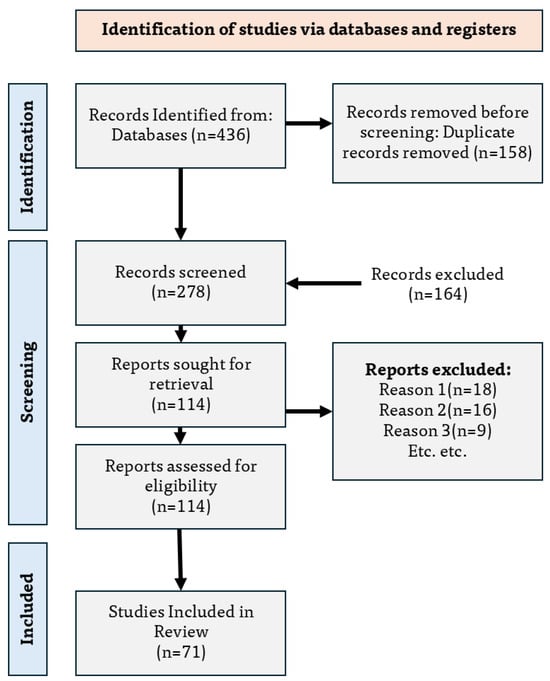

Study selection results: The search process identified records. After deduplication, records were removed, leaving for title and abstract screening. Full texts were retrieved and assessed for reports, of which were excluded with reasons (out of scope ; lacking quantitative kinematics ; unrelated to upper limb ). A total of studies met all criteria and were included in the synthesis across the sensing, fusion, cognitive, and metrological layers.

Figure 2 illustrates the PRISMA 2020 flow diagram, including databases searched, deduplication prior to screening, records screened, reports assessed, exclusion reasons, and the final set of studies incorporated in this review.

Figure 2.

PRISMA flow diagram showing identification, screening, eligibility assessment, and inclusion of studies on upper-limb positioning and metrology-driven rehabilitation robotics.

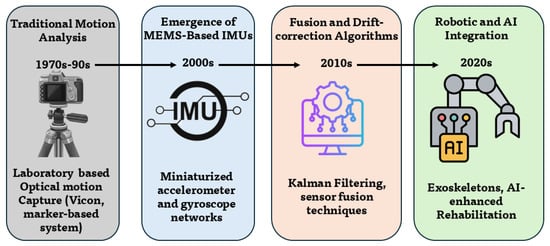

3. Evolution of Upper-Limb Positioning Systems

The evolution of upper-limb positioning systems reflects a gradual transition from laboratory optical precision to portable, intelligent, and context-aware sensing frameworks. This section outlines the principal technological and conceptual milestones, from stereophotogrammetric systems to hybrid, AI-enhanced, and robot-integrated approaches, and highlights how measurement accuracy, portability, and ecological validity improved over time. Figure 3 summarizes the historical progression. Quantitative comparisons of angular accuracy, computational latency, and device cost are reported where available to illustrate efficiency and clinical usability trends [12,23,41,42] (see Table 2). Foundational advances in context-aware sensing and on-body intelligence are reflected in multimodal activity recognition and deep sensor-fusion studies [43,44,45,46,47].

Figure 3.

Historical evolution of upper-limb positioning systems, illustrating the progression from laboratory optical motion capture to wearable inertial sensors, sensor-fusion and drift-correction algorithms, and integration with robotic and AI-driven rehabilitation frameworks.

Table 2.

Representative commercial motion-capture and wearable systems for upper-limb kinematic analysis.

3.1. Traditional Motion Analysis (1990s to Early 2000s)

Optical motion-capture systems established the reference for quantitative human movement analysis. Early comparative evaluations characterized commercial platforms such as Vicon, Qualisys, and Optotrak, indicating sub-millimetre spatial accuracy under controlled conditions [10]. The mathematical framework for stereophotogrammetry, including camera calibration, marker reconstruction, and propagation of instrumental errors to segment kinematics, was formalized in subsequent work [11]. Independent assessments quantified optical accuracy and spatial variability across large capture volumes [12] and identified error sources relevant to gait and upper-limb applications [13]. These results defined the benchmark for later wearable technologies.

Despite high accuracy, optical systems required controlled laboratories, complex setup, and substantial infrastructure, and were susceptible to occlusions. Electromagnetic (EM) trackers extended capture beyond line-of-sight but remained sensitive to ferromagnetic disturbances and had limited operational range [14]. The demand for portable, unconstrained, and repeatable motion tracking fostered the adoption of inertial sensing. In this period, mean angular root mean square error (RMSE) for optical systems was typically below 1°, whereas EM trackers often exhibited 3° to 5° under mild interference; acquisition rates commonly ranged from 60 Hz to 120 Hz [12] (RQ1). These early studies established a clear relationship between measurement principle and achievable angle accuracy [10,11]. Optical triangulation provides high spatial precision under controlled conditions, but joint-angle accuracy deteriorates in the presence of marker occlusion, skin motion, and limited capture volume [11,12,13]. Electromagnetic tracking, while independent of line-of-sight, introduced field-dependent distortions that translated into joint-angle errors during upper-limb motion [15,20,21]. These principle-level limitations motivated the transition toward inertial sensing approaches capable of supporting ambulatory and robot-assisted rehabilitation tasks [16,17,18].

3.2. Emergence of MEMS-Based IMUs (Early to Mid 2000s)

The proliferation of micro-electromechanical systems (MEMS) inertial measurement units (IMUs) enabled ambulatory kinematic measurement. Continuous orientation tracking with miniature gyroscopes and accelerometers achieved inclination errors near 3° with real-time gyro bias estimation [16]. Anatomical calibration protocols using Xsens sensors demonstrated full three-dimensional scapulothoracic and humerothoracic angle measurement outside laboratory settings [18].

These studies established the feasibility of portable upper-limb motion analysis while exposing limitations related to drift accumulation, unobservable heading without magnetometers, and sensitivity to soft-tissue artefacts. Evidence on placement sensitivity in upper-limb motion [49], verification of kinematic accuracy [42], and the impact of sensor-to-segment misalignment on joint-angle estimation [50] identified calibration and alignment as first-order design factors; guidance on biomechanical signal filtering is available in [51]. Efforts to reduce sensor count while preserving joint-angle fidelity motivated minimal-IMU configurations [52]. The transition from optical to MEMS sensing also introduced reductions in size and cost together with practical trade-offs documented in broader assessments of IMU usage [41] (RQ1, RQ3).

Inertial measurement accuracy is fundamentally constrained by the integration of noisy angular-rate signals and the observability of orientation states [16,35,53]. Accelerometers provide inclination through gravity sensing but are sensitive to dynamic accelerations, while magnetometers offer heading information that is susceptible to environmental disturbance [16,20,21]. Consequently, joint-angle accuracy in upper-limb applications varies across joints and movement conditions, with higher errors observed in multi-degree-of-freedom segments and during fast or compensatory motions [4,23,25]. These biomechanical dependencies underscore the need for principled calibration and fusion strategies when interpreting inertial kinematics [4,23,54].

3.3. Fusion and Drift-Correction Algorithms (Mid 2000s to 2010s)

Algorithmic development from 2005 to 2015 addressed drift and alignment errors. Complementary Kalman filters integrated accelerometer, gyroscope, and magnetometer data with explicit disturbance estimation, achieving dynamic orientation errors below 3° [17,21]. Quaternion-based extended Kalman filtering eliminated Euler singularities and enabled real-time full-body orientation estimation [35].

Nonlinear complementary filtering on the special orthogonal group provided globally stable attitude estimation for low-cost sensors [19]. Experimental analyses quantified magnetic interference and validated correction methods for joint-angle reconstruction [20]. Biomechanical models introduced joint-level constraints and inverse kinematic optimization to mitigate soft-tissue artefacts, with emphasis on scapular and humeral motion [15]. Comprehensive reviews of IMU-based pose estimation and drift-reduction techniques are available [55], including drift-free strategies for dynamic conditions [56] and practical filtering recommendations [51]. Algorithmic complexity ranged from gradient-descent filters to Kalman estimators at 100 Hz, with accuracy and energy–latency trade-offs summarized in [23,41] (RQ1, RQ2).

From a computational perspective, latency in fusion-based pipelines is dominated by matrix operations and update frequency [53,57]. Extended Kalman filters incur cubic-time complexity due to covariance propagation and inversion, which constrains achievable sampling rates on embedded processors [57,58]. In contrast, complementary and nonlinear observer-based filters rely on fixed-gain updates and avoid matrix inversion, enabling deterministic low-latency execution suitable for closed-loop robotic control [19,59,60]. Algorithmic optimizations reported in the literature include state-dimension reduction and selective covariance updates for Kalman-type estimators, as well as practical gating/robust handling of magnetometer measurements under disturbance, which collectively reduce inference latency while preserving estimation consistency [21,57,61].

3.4. Integration into Robotic and AI-Enhanced Frameworks (2010s to Present)

Mature inertial estimation enabled integration into rehabilitation robotics and assistive systems. Robotic exoskeletons and end-effector devices incorporated IMUs, encoders, and electromyography (EMG) to support adaptive control strategies, including impedance and admittance control and assist-as-needed operation [62]. Joint-angle inference from EMG and kinematics provided embedded feedback for control [31]. Meta-analyses quantified therapeutic benefit while noting heterogeneity in device configuration, dosage, and evaluation metrics [63]. Systematic reviews consolidated evidence for IMU-based systems in clinical contexts and reported design guidelines, accuracy benchmarks, and outcome measures [23]. Placement-critical considerations for upper-limb deployment were detailed in [49]. Commercial wearable platforms reported reliability across athletic and clinical scenarios [64], and complementary sensing for cardiopulmonary monitoring progressed in parallel [65,66,67].

Concurrently, embedded AI accelerators and edge computing enabled on-board inference for joint-angle regression and state estimation using lightweight deep models, including convolutional and recurrent architectures [28,30,43,44,45,68,69,70]. Kinematic reconstruction with task constraints and distributed wearable computing reduced latency and infrastructure dependence [29,71,72]. These developments form a technical bridge between conventional fusion and cognitive robotic intelligence (RQ2).

Reported implementations highlight that computational burden and latency depend strongly on model structure and deployment platform [43,53,59]. Classical fusion pipelines typically achieve sub-10 ms processing latency at 100 Hz on microcontrollers, whereas learning-based estimators exhibit higher but bounded inference times that scale with parameter count and sequence length [43,44,59,60]. Optimization strategies such as reduced-precision arithmetic, windowed inference, and hardware-aware scheduling enable known latency budgets to be met in robot-assisted therapy scenarios [9,34,73].

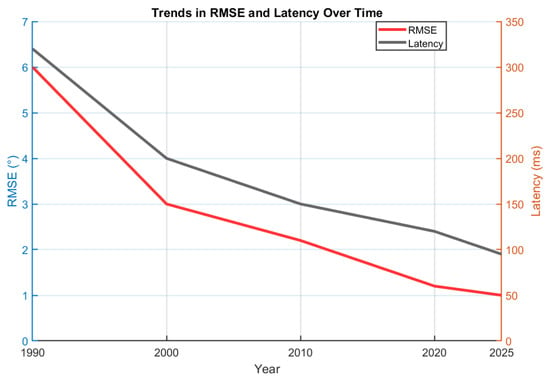

3.5. Synthesis and Outlook

The lineage from optical to inertial to intelligent robotic systems (Figure 3) shows a consistent shift toward portability, contextual adaptability, and cognitive integration. Optical frameworks established metrological ground truth [10,11]. MEMS-based IMUs enabled wearable motion capture [16,18]. Fusion algorithms achieved near-optical accuracy in ecological settings [21,22,35]. Across the literature, reductions in orientation RMSE and system latency are observed alongside decreasing per channel cost, these quantitative trends across successive technology generations are summarized in Figure 4. Trade-offs and clinical guidance are further summarized in [23,41]. Priorities include magnetometer-free operation, robust handling of misalignment and soft-tissue artefacts [50,51], and uncertainty-aware pipelines that interface with robotic decision-making; recent surveys on drift reduction provide additional context [55]. Continued maturation of upper-limb placement protocols [49] is expected to strengthen traceability and clinical adoption.

Figure 4.

Quantitative performance timeline of upper-limb positioning technologies from 1990 to 2025. Reported mean angular error (RMSE) and latency (ms) indicate progressive improvements in accuracy and real-time performance.

4. Wearable and Inertial Sensing Foundations

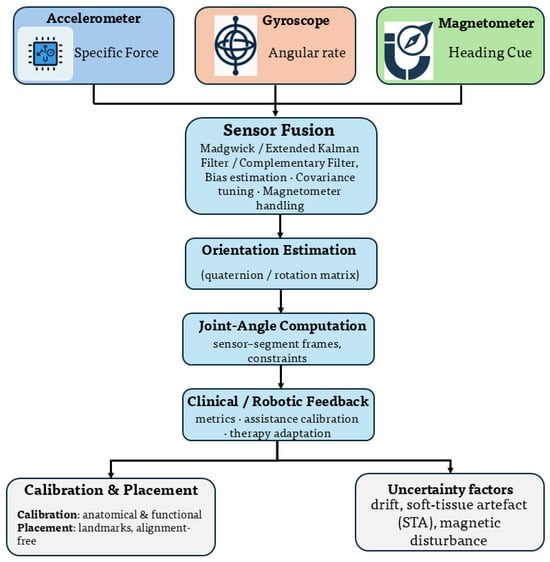

Wearable inertial sensing is a principal enabler of ambulatory upper-limb kinematic assessment. A typical inertial measurement unit (IMU) integrates a tri-axial accelerometer for specific force, a gyroscope for angular rate, and optionally a magnetometer for the local magnetic field. Conversion of raw signals into clinically useful joint kinematics requires four elements: (i) a sensing configuration and protocol, (ii) sensor-to-segment calibration and placement, (iii) drift-robust data fusion with uncertainty handling, and (iv) validation against optical or robotic ground truth. Figure 5 summarizes this pipeline. A metrological framework is adopted to couple sensor fusion with uncertainty propagation and traceable calibration.

Figure 5.

Architecture of a wearable sensing system. Raw IMU signals are fused to estimate segment orientation, which is mapped to joint angles through sensor-to-segment calibration and biomechanical constraints. Uncertainty sources are indicated at each stage, including sensor bias , scale factor , drift model , and calibration covariance .

The measurement principle of each sensing modality directly influences joint-angle accuracy in biomechanical applications [16,23]. Inertial sensors infer orientation through angular-rate integration and gravity alignment, which makes accuracy sensitive to bias drift, sensor noise, and calibration quality [16,35,36]. Flexible and strain-based wearable sensors estimate joint motion through local deformation, resulting in accuracy that depends on material properties, nonlinear strain–angle relationships, and attachment consistency [74]. In upper-limb rehabilitation, these effects manifest as joint-dependent uncertainty, particularly at anatomically complex segments, and necessitate uncertainty-aware fusion and validation against traceable references [23,24].

From a clinical perspective, IMU pipelines are employed to quantify movement quality in rehabilitation robots and daily activities, complementing traditional scales with objective kinematic biomarkers [34,75,76,77]. Open toolboxes and standardized metric taxonomies support reproducible analysis across datasets and platforms [38,78]. In parallel to inertial sensing, flexible and soft wearable sensors have emerged as complementary technologies for upper-limb rehabilitation robotics. These sensors, including strain-based, textile-integrated, and elastomeric transducers, enable conformal attachment to the human body and robotic interfaces, improving wearability and continuous motion capture during assisted therapy [74]. Their compliant nature facilitates closer physical coupling between the patient and the rehabilitation robot, with potential benefits for sensing fidelity and operational comfort. Heterogeneity in calibration procedures, magnetic susceptibility, and reporting practices continues to limit cross-study comparability, which motivates intelligent and self-calibrating approaches [23,54] ( See Table 3). The subsections below formalize the calibration-to-validation chain with quantitative uncertainty and computational metrics (RQ1, RQ3).

Table 3.

Representative IMU-based upper-limb studies and reviews with dataset and context details. Reported errors are indicative ranges aggregated from each source.

4.1. IMU Configurations and Protocols

Common upper-limb configurations mount IMUs on the sternum or scapula, upper arm, forearm, and in some cases the hand to capture humerothoracic, elbow, and wrist motion. Protocols specify reference frames, anatomical landmarks, and functional tasks used for calibration and evaluation [1,25,54]. In robot-assisted therapy, on-board encoders and force sensors are combined with IMUs to provide redundancy for controller adaptation and movement assessment [34,75]. Recent rehabilitation systems further integrate flexible wearable sensors within these configurations, either as standalone joint-angle transducers or in hybrid arrangements with IMUs [74,79,80]. Flexible strain and textile-based sensors are commonly positioned across joints such as the elbow or shoulder to directly encode joint deformation, offering an alternative sensing pathway that reduces sensitivity to rigid-body misalignment and attachment variability [67,77,81].

Standardized metric sets based on smoothness, speed, accuracy, efficiency, range of motion, and force-related indicators are increasingly adopted to align kinematic readouts with clinical outcomes [38,78]. Sampling rates for contemporary IMUs typically range from 100 to 1000 Hz, providing bandwidth for rapid upper-limb trajectories; dynamic range near ±2000 deg/s and noise density on the order of to characterize achievable angular resolution in fine-motor tasks (RQ1). In contrast, flexible sensors trade high-frequency bandwidth for enhanced conformability and continuous joint coverage, which can improve operational robustness in long-duration rehabilitation sessions when combined with appropriate calibration and compensation strategies [27,67].

4.2. Calibration and Alignment-Free Techniques

Accurate joint-angle estimation depends on consistent sensor-to-segment alignment. Anatomical calibration may rely on bony landmark identification or functional movements to align IMU frames with anatomical axes [54]. Alignment-free or personalized strategies infer alignment parameters during natural movements using optimization or probabilistic modeling, thereby reducing user burden and improving ecological validity. Reviews report typical errors for elbow and humerothoracic joints in the range of 2° to 5° under controlled conditions [4,23]. Magnetometer-free configurations are increasingly explored to avoid heading corruption in disturbed environments, with biomechanical constraints and refined Kalman filtering stabilizing yaw [36] (RQ3).

From a metrological standpoint, calibration uncertainty can be propagated from sensor-level bias and scale errors to joint-angle uncertainty using a first-order Taylor expansion following the GUM:

where is the Jacobian of the joint-angle model with respect to sensor outputs and is the covariance matrix of sensor noise and bias. This formulation enables estimation of combined standard uncertainty in degrees for each reconstructed joint and supports traceable confidence intervals comparable across laboratories. Calibration-repeatability studies generally report within 1.5° to 2.5° for static alignment and below 5° under dynamic conditions.

4.3. Data Fusion and Uncertainty

Sensor fusion estimates orientation while attenuating drift and noise. Frequently used approaches include quaternion extended Kalman filters (EKF), complementary filters on , and gradient-descent methods such as Madgwick [36]. Comparative analyses emphasize that low-acceleration and steady-state periods inform gyro-bias compensation, magnetometer cues improve heading when the field is reliable, and explicit modeling of process and measurement covariances is crucial for uncertainty-aware estimation [4,23]. In rehabilitation robots, uncertainty estimates are propagated to controller constraints to ensure safe assistance [34]. When the magnetic environment is unstable, magnetometer rejection with joint-level constraints or vision–inertial fusion is preferred [25,82] (RQ2).

From a metrological standpoint, fusion algorithms do not alter the underlying measurement principle but mitigate its error propagation by combining complementary information sources, thereby bounding joint-angle uncertainty rather than eliminating principle-induced limitations [53,58]. In contrast to classical Bayesian fusion, which combines measurements through explicitly defined likelihood models and noise covariances, learning-based approaches rely on data-driven mappings to integrate multimodal information [28,29,58]. This distinction is particularly relevant in upper-limb biomechanics, where soft-tissue artefacts, intermittent magnetic disturbance, and heterogeneous sensor noise complicate explicit probabilistic modeling [15,20,21,23].

Fusion filters differ in mathematical complexity and computational load. Complementary filters operate with fixed-gain blending at cost and can achieve kilohertz throughput on microcontrollers with low power consumption [59,60]. Quaternion-based EKF introduces matrix inversion at cost while providing consistent estimates with covariance output near 100 Hz and moderate power budgets [53,58]. Nonlinear observers on combine stability and low power while maintaining attitude accuracy within 2° to 3°. Gradient-descent schemes achieve near-EKF accuracy with reduced computational cost [57,61].

Drift modeling is central to uncertainty quantification. Bias instability , random-walk coefficient , and Allan deviation describe gyro and accelerometer drift characteristics, with fitted empirically for each sensor. Real-time bias adaptation and periodic reset filtering reduce accumulated drift to below 2° per minute in recent systems. These drift models support GUM Monte Carlo (GUM–MC) simulations to bound long-term orientation uncertainty [83] (RQ4).

Latency-aware implementations prioritize algorithmic simplicity and predictable execution time [59,60]. Fixed-gain filters and nonlinear observers are frequently selected due to their bounded worst-case runtime and avoidance of matrix inversion [19,59,60]. Kalman-based approaches remain feasible when optimized through reduced state dimension, selective covariance updates, or decoupling of slow and fast states [57,58]. These optimizations enable real-time operation while preserving uncertainty estimates required for safety-aware control in rehabilitation robotics [34,53].

4.4. Validation Against Motion-Capture Systems

Clinical validity is established by comparison of IMU-derived angles with optical motion capture (OMC) or robot encoders. Systematic reviews report elbow and humerothoracic errors typically in the range of 2° to 5° under controlled tasks, with larger errors at scapulothoracic and glenohumeral joints due to soft-tissue artefact and heading uncertainty [4,23]. Recent comparative studies indicate that, for functional tasks such as an instrumented drinking activity, low-cost IMUs approximate OMC sufficiently for movement-quality assessment in mild-to-moderate stroke cohorts [25]. Magnetometer-free pipelines and robust calibration reduce failure modes in magnetically perturbed settings [36]. These findings support deployment beyond the laboratory, provided that protocols report sensor placement, calibration, environment, and uncertainty metrics. Figure 4 presents mean RMSE per joint from representative studies, confirming higher susceptibility of proximal joints to soft-tissue displacement.

4.5. Outlook: Toward Intelligent and Self-Calibrating Sensing

Converging evidence indicates that standardized calibration protocols, magnetometer-robust fusion with explicit uncertainty estimates, and transparent validation against OMC or encoders are necessary for reproducible clinical translation [23,75]. Emerging directions include self-calibrating workflows that infer alignment and bias online, dataset-agnostic toolchains for reproducible kinematic metrics [38], and edge-AI classifiers that transform raw IMU streams into patient-relevant digital markers during daily activities [73,77]. Flexible wearable sensors represent a complementary sensing pathway for upper-limb rehabilitation robotics, but they introduce modality-specific metrological constraints, including hysteresis, nonlinear strain-to-angle mapping, temperature sensitivity, and time-dependent drift. Reliable use therefore requires explicit calibration models, repeatability characterization, and uncertainty-aware compensation mechanisms that remain stable across attachment conditions and therapy duration [77].

At the sensing layer, the primary open issues are calibration repeatability across operators, robustness to magnetic and attachment disturbances, and consistent uncertainty reporting for joint-level kinematics. Integrated system-level priorities, milestones, and validation endpoints are consolidated in Section 8 to avoid repetition and to present a single cross-cutting research roadmap.

Despite continued advances in calibration, fusion, and uncertainty modeling, the evidence reviewed in this section indicates that classical sensing pipelines face intrinsic limitations in upper-limb biomechanics [4,23]. Soft-tissue artefacts, subject-specific movement strategies, non-stationary sensor disturbances, and context-dependent task execution introduce nonlinearities and variability that cannot be fully resolved through fixed biomechanical models or analytically defined noise assumptions [15,20,21,49]. As sensing systems move from controlled laboratory conditions to home and daily-life environments, these effects increasingly dominate the error budget and limit the scalability and adaptability of purely model-based estimation [23,41,77]. Consequently, intelligent modeling emerges not as a functional extension of wearable sensing, but as a necessary development to capture latent motion patterns, personalize estimation across users, and adapt inference under heterogeneous and evolving conditions [28,29,30,37].

5. Intelligent Modeling and Cognitive Rehabilitation Robotics

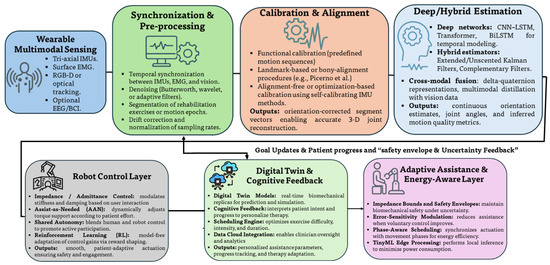

Section 1, Section 2, Section 3 and Section 4 established that trustworthy upper-limb positioning depends on high-quality wearable sensing, rigorous sensor-to-segment calibration, and uncertainty-aware fusion verified against optical or robotic ground truth. Building on this foundation, this section examines how data-driven estimators transform multimodal signals into joint kinematics and intent, and how rehabilitation robots convert these estimates into patient-adaptive assistance. The objective is a cognitive rehabilitation loop in which the robot interprets patient intent, adapts assistance to evolving capability, and learns user-specific kinematics over time (Figure 6). To provide analytical depth, the discussion introduces a taxonomy of learning approaches, quantitative comparisons across model families, treatment of interpretability and generalization, and an energy profile for embedded deployment.

Figure 6.

Cognitive sensing-to-control pipeline. Multimodal signals are synchronized, calibrated, and fused by deep or hybrid estimators to recover orientation, joint angles, and movement-quality metrics. The robot controller adapts assistance using intent cues, while a digital twin layer personalizes therapy and an energy-aware layer enforces safety envelopes and efficient actuation.

5.1. Data-Driven Estimation from Wearable Signals

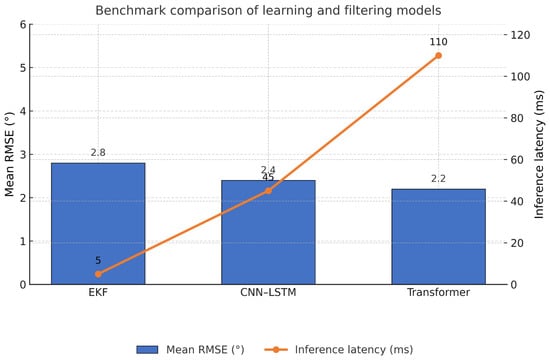

Deep networks reconstruct joint kinematics from sparse inertial arrays with accuracy comparable to classical filters while reducing sensor count. Convolutional neural network (CNN) and long short-term memory (LSTM) pipelines, including bidirectional LSTM (BiLSTM), trained on upper arm and forearm IMUs recover shoulder and elbow angles with errors competitive with extended Kalman filter (EKF) baselines [39]. Cross-modal training further improves accuracy. Vision keypoints used as supervisory signals for IMU models provide better orientation and angle estimates without additional runtime sensing through multimodal distillation [32]. Sequence models operating on delta quaternions stabilize orientation learning on and reduce error accumulation [84]. Reported mean root mean square error (RMSE) for elbow and humerothoracic angles commonly lies within 2° to 5° for CNN–LSTM models at 100 to 200 Hz input, with latency below 50 to 80 ms on embedded processors after quantization. Temporal transformer variants achieve comparable accuracy for longer context windows at higher compute and memory cost (RQ2), and Table 4 classifies the main learning models used for upper-limb estimation.

Table 4.

Taxonomy of learning methods for upper-limb estimation and cognition. Dimensions include model class, inputs, typical training scale, interpretability, real-time feasibility, and clinical validation status.

Beyond pointwise accuracy, clinical applicability depends on robustness to inter-subject variability, pathological kinematics, and compensatory movement strategies. Upper-limb impairment is frequently characterized by altered joint coordination, asymmetric motion patterns, and task-dependent compensations that deviate from the kinematic distributions observed in healthy cohorts [79,80,85]. Models trained exclusively on healthy motion may therefore achieve low RMSE while misinterpreting compensatory strategies as recovery, which represents a critical limitation for rehabilitation assessment and adaptive assistance [85].

Robust evaluation of learning-based estimators thus requires analysis across heterogeneous populations and movement strategies. Reported approaches include pathology-aware fine-tuning, subject-wise leave-one-out validation, and domain adaptation methods that align latent representations between healthy and impaired motion [79,86]. Performance reporting limited to aggregate RMSE can obscure failure modes under compensatory motion. Complementary indicators such as joint-wise error distributions, prediction interval coverage, and sensitivity to atypical trajectories provide a more informative assessment of generalization [87].

In learning-based pipelines, information fusion is performed implicitly through the network architecture rather than through explicit probabilistic weighting, as multimodal dependencies are learned directly from data [28,43]. Early fusion is commonly achieved by concatenating synchronized sensor streams, such as multi-IMU signals or combined IMU and electromyography inputs, at the network input [31,43]. Feature-level fusion is realized through shared latent representations learned by convolutional or recurrent layers, where modality-specific features are jointly embedded and temporally aggregated [28,43]. Late fusion strategies employ modality-specific subnetworks whose outputs are combined through learned weighting or ensemble averaging, often conditioned on task context or confidence estimates [45]. In multimodal distillation settings, vision-derived kinematics act as a supervisory signal during training, transferring cross-modal information into inertial-only models without increasing inference-time sensing [32].

Inference latency in learning-based pipelines is primarily governed by network depth, temporal window length, and numerical precision [28,88]. Post-training quantization, pruning of recurrent states, and replacement of floating-point operations with fixed-point arithmetic substantially reduce inference time while preserving kinematic accuracy [73,88]. Such optimizations are essential for integration into closed-loop rehabilitation robots operating under strict timing and safety constraints [9,89].

Synthesis papers identify conditions for reliability, including drift-aware targets, windowed training, consistent calibration, and biomechanical constraints [5,23]. Tutorials on quaternion and EKF modeling clarify where learned estimators benefit from physically grounded priors and observability analysis [36]. Learned features also serve as digital biomarkers, such as smoothness, reaction time, and accuracy, which correlate with Fugl–Meyer Assessment (FMA) and Wolf Motor Function Test (WMFT) scores in robot-integrated tasks and daily activities [34,77]. Toolboxes and metric taxonomies support reproducible computation across datasets [38,78]. Quantitative reporting should therefore include both accuracy and robustness indicators, including pre-transfer and post-transfer performance, coverage of prediction intervals, and sensitivity to compensatory motion patterns, to support transparent clinical translation.

5.2. Cognitive Architectures in Rehabilitation Robots

With reliable kinematics, rehabilitation robots transition from fixed routines to patient-aware interaction. Surveys catalogue exoskeleton and end-effector devices that implement patient-cooperative and assist-as-needed paradigms with embedded sensing [62,90]. Multimodal intent detectors based on IMU, electromyography (EMG), and vision inform impedance or admittance modulation and shared autonomy [90]. Digital twin architectures replicate patient dynamics by fusing wearable streams with robot encoders and simulation back-ends to enable predictive adaptation and analytics [40]. Large multi-center efforts provide harmonized datasets for benchmarking [91]. Clinical studies indicate that robot-measured kinematics act as prognostic biomarkers of recovery and can be integrated into therapy for movement-quality assessment [34,76]. Within such architectures, the learning component benefits from calibrated confidence and interpretable attributions that can be consumed by safety monitors and by clinicians. This linkage binds estimation confidence to controller envelopes and increases transparency (RQ4).

5.3. Model-Based, Model-Free, and Hybrid Learning

The interface between learned components and control is a primary design decision. Model-based controllers exploit biomechanical structure and uncertainty propagation for interpretability and safety but may underfit subject-specific dynamics. Model-free policy learning adapts from experience and requires careful constraint handling and attention to data efficiency. Contemporary systems adopt hybrid schemes in which learned observers, such as kinematic estimators, intent classifiers, or residual dynamics models, operate within physically consistent controllers bounded by safety envelopes. Reviews of AI in rehabilitation robotics identify hybridization, explainability, and generalization as dominant trends [37], with multisensory feedback and optimization highlighted as near-term opportunities [89]. Within these architectures, uncertainty-aware estimators from Section 4 feed controllers constrained by bounded impedance and rate limits, while open metric toolboxes link controller adaptations to clinically interpretable outcomes [38,78]. A practical pattern combines a compact observer for kinematics and intent, a supervisory layer that maps estimator covariance and coverage to stiffness and rate-limit bounds, and a monitor that enforces passivity or energy budgets. This separation of learning from guarantees supports certification and clinical audit (RQ2, RQ4).

Hybrid learning architectures provide a structural advantage for robustness under compensatory and pathological motion [92,93]. Biomechanical constraints embedded in the control layer limit physically implausible estimates, while learned components adapt to subject-specific dynamics and non-linear sensor effects [92]. This coupling reduces the risk that compensatory strategies are misclassified as normative motion, which is a known limitation of purely data-driven estimators trained on healthy populations.

Within such architectures, explicability emerges at the system level through structured information flow rather than isolated model introspection [33,93]. Low-level fusion integrates raw or preprocessed sensor signals within learned observers, producing state estimates accompanied by uncertainty descriptors. At higher levels, estimated kinematics, intent probabilities, and confidence bounds are combined to modulate controller parameters such as impedance, assistance gain, or task progression. This hierarchical fusion enables traceability between sensing, estimation, and control actions, ensuring that performance improvements introduced by learning remain interpretable and verifiable in clinical settings [93].

5.4. Toward Energy-Aware and Sustainable Intelligence

Scaling intelligent functionality requires attention to computation and actuation budgets. Edge-oriented inference using Tiny machine learning (TinyML) enables on-device sequence modeling for IMU streams and reduces bandwidth and power [73]. On the actuator side, phase-aware scheduling, intent-gated support, and gravity compensation limit redundant torque production. Digital twin simulation supports duty-cycle optimization and predictive maintenance [40]. Energy profiling should accompany accuracy reports, including inference latency, parameter count, floating-point operations per second, and measured power on representative hardware. CNN–LSTM models with fewer than one million parameters typically sustain 100 Hz inference at 30 to 150 mW on microcontrollers or low-power neural processing units (NPUs). Temporal transformer variants often require two to ten times more energy unless aggressively quantized.

Beyond model compression, system-level optimization strategies include early-exit inference, event-driven execution triggered by motion salience, and joint optimization of sensing, inference, and control update rates [9,73]. These approaches reduce computational burden and latency while maintaining clinically relevant accuracy, supporting sustainable deployment in long-duration rehabilitation settings [73,80].

5.5. Layer-Specific Synthesis of Intelligent Estimation

The intelligent layer completes the progression developed in Section 1, Section 2, Section 3 and Section 4. Wearable sensing provides multimodal input, and learning-based or hybrid estimators convert these signals into joint kinematics and intent under constraints of latency, compute budget, and deployment context. Within this scope, the main contribution of this section is a structured linkage between model family, generalization strategy, and deployment feasibility, together with reporting elements that support clinical interpretability.

A recurring requirement across intelligent estimators is the presence of decision-support outputs that remain auditable in rehabilitation settings [33,34,37]. Relevant outputs include calibrated prediction intervals or uncertainty summaries (e.g., covariance/variance outputs), modality contribution indicators in multimodal models, and failure mode cues under distribution shift [33,45,86]. These outputs enable consistent comparison across learning pipelines and clarify how model uncertainty can be exposed for downstream use in assessment and control [33,34].

System-level integration of estimator confidence with controller constraints, clinician-facing oversight, and certification-oriented trust objectives is treated as a cross-cutting topic and is therefore centralized in Section 8 [9,62,89]. This separation preserves the technical focus of the intelligent layer while keeping the roadmap as the single consolidated location for future directions and endpoints.

6. Human–Robot Interaction and Co-Adaptive Control

Rehabilitation proceeds as an interactive loop in which assistance and human behaviour evolve together. The robot modulates support according to sensed capability, while the patient adapts movement strategies in response to cues and constraints. This section formalizes the bidirectional process in human–robot interaction (HRI), outlines multimodal intent sensing, and presents control constructs that enable co-adaptation with safety, transparency, and trust as primary requirements. Quantitative parameters and latency figures are reported to connect the formulations to deployed upper-limb systems (RQ4).

6.1. Shared Autonomy and Adaptive Assistance

Shared autonomy blends human and robot commands to maintain engagement while ensuring task completion. Let denote the human command estimated from intent, for example surface electromyography (sEMG) or voluntary torque, and the robot assistive command. A common allocation is

where increases with intent-recognition confidence or measured voluntary effort [62,90]. Assist-as-needed control adapts based on task error and effort. A Cartesian impedance template is

with gains updated using effort-aware rules, for example

where , encodes voluntary activation, and are learning and forgetting factors, and enforces bounded stiffness for safety [94]. Equation (2) is implementable at torque or velocity level and can be combined with virtual fixtures for precision tasks. Typical reported stiffness gains for elbow rehabilitation are 150 to 300 N/m for ARMEO Power and 200 to 500 N/m for MIT-MANUS, with damping between 10 and 30 Ns/m. Assistance adaptation rates from 0.05 to 0.2 produce perceptible yet stable support changes. Inner loops commonly update at 500 to 1000 Hz, enabling sub-2 ms force-output latency.

6.2. Multimodal Feedback and Intent Recognition

Reliable intent estimation benefits from complementary sensing. Electromyography (EMG) captures feedforward muscle activation; inertial measurement units (IMUs) provide segment kinematics; force and torque sensors quantify interaction; cameras or depth sensors add context when occlusions are manageable (modalities summarized in Table 5). Reviews map sensing to control decisions and survey data-driven classifiers and sequence models for intent-aware assistance [37,90] (See Figure 7). Practical fusion rates for intent decoding are 100 to 200 Hz with classifier decision delays below 50 ms to sustain natural feedback. Many systems employ a two-level hierarchy: high-rate reflexive control from physical sensors and lower-rate cognitive modulation from EMG or vision inputs.

Table 5.

Sensing modalities in co-adaptive rehabilitation and their roles, with signal rate, delay tolerance, and fusion strategy.

Figure 7.

Benchmark-style comparison of learning and filtering approaches. Left axis shows mean RMSE for elbow and humerothoracic angles; right axis shows inference latency. Bars illustrate typical ranges for EKF, CNN–LSTM, and temporal transformer models under comparable sensor density.

Multimodal feedback sustains engagement and promotes motor learning. Visual progress bars and target overlays communicate task goals; haptic cues implement guidance or resistance consistent with Equation (3); proprioceptive feedback is shaped through compliant trajectories. Therapy-integrated studies identify smoothness, reaction time, speed, and accuracy as reliable movement-quality metrics for closed-loop cueing [34]. Daily-activity markers derived from a single wrist IMU correlate with clinical scales and extend feedback beyond the clinic [77]. Latency budgets between sensed action and feedback within 100 to 150 ms are generally tolerated without disrupting motor learning.

6.3. Co-Adaptive Learning Models

Co-adaptation can be expressed as joint optimization of a personalization vector and a control policy :

where ℓ penalizes task error and effort, updates personalization from measured metrics such as smoothness, range, and fatigue proxies, and is a learning matrix. Hybrid designs embed learned observers, for example intent classifiers or residual dynamics, within model-based controllers to preserve physical consistency while adapting to idiosyncratic behaviour [37]. Robot-measured kinematics show prognostic value and support data-driven scheduling of difficulty and dose [76]. Empirical reports indicate adaptation convergence within 8 to 12 training sessions for HAL-type systems and assistance reductions of 20 to 30% after approximately 10 sessions with co-adaptive stiffness tuning in MIT-MANUS cohorts.

6.4. Safety, Transparency, and Trust

Safety envelopes constrain stiffness, velocity, and power. Passivity layers or energy tanks prevent net energy injection under uncertainty, and rate limiters avoid abrupt assistance changes. Transparency is promoted by dashboards that explain controller adjustments in clinical terms, for example assistance reduction due to improved smoothness, and by reporting uncertainty on states and intents, for example confidence-weighted in Equation (2). Validation against optical motion capture or encoders remains essential for traceability [24,54]. Comfort and ethics include managing muscle fatigue, avoiding over-constraint, ensuring data privacy for EMG or vision streams, and preserving user agency through shared autonomy [62,90]. Typical stability margins for upper-limb exoskeletons are 20 to 35 dB in phase and 6 to 10 dB in gain; inner torque loops remain stable under delays up to 20 ms. Trust calibration metrics, including user comfort, perceived transparency, and cognitive load, provide measurable indicators of the safety–trust balance.

6.5. Bridge to Cognitive Aims

Co-adaptive HRI links mechanical accuracy with cognitive objectives by translating kinematic estimation into assistance modulation and interpretable feedback. In this pathway, sensing and fusion define the fidelity of state estimates, while interaction design determines how assistance is perceived, adapted, and accepted during therapy. Digital coaching signals and progress analytics convert short-horizon kinematics into clinically meaningful indicators when measurement uncertainty is tracked and communicated. This section therefore serves as a conceptual transition from estimation to interaction, emphasizing how measurement quality and timing constraints shape usable feedback and safe adaptation (see Figure 6). Consolidated research gaps, milestones, and long-horizon targets that span sensing, learning, interaction, and governance are presented in Section 8.

7. Standardization, Traceability, and Future Research Directions

The advancement of upper-limb rehabilitation robotics requires technical performance together with demonstrable reliability and trustworthiness. Measurement traceability, standardized calibration, and explainable intelligence underpin clinical acceptance and ethical deployment. This section integrates two perspectives: (i) the need for metrological rigour and regulatory alignment, and (ii) technological trends that define the research frontier toward 2030. Quantitative examples and normative references are included to link conceptual reliability to measurable practice (RQ3, RQ4).

7.1. Metrology and Traceability in Rehabilitation Robotics

Measurement science establishes the basis for reproducible rehabilitation technology. Each sensing chain, from accelerometer to clinical outcome, should be traceable to a reference standard. Calibration protocols for inertial sensors employ gravitational and magnetic references, static alignment sequences, or optical benchmarking to quantify bias and scale factors. Optical motion capture remains a calibration reference for assessing inertial measurement unit (IMU) drift, alignment accuracy, and repeatability across trials [24,54]. Repeatable characterisation produces confidence intervals and defines performance limits for clinical monitoring and robotic assistance.

A representative traceability chain is summarised as follows: sensor output → calibration artefact (for example, reference goniometer or rate table) → accredited metrology laboratory certified under ISO/IEC 17025 [96] → national metrology institute (NMI) → International System of Units (SI) realisation. Each link introduces calibration uncertainty that combines according to the GUM. Representative co-adaptive control strategies and their comparative performance characteristics are summarized in Table 6. Inter-laboratory comparison campaigns coordinated by institutes such as Physikalisch-Technische Bundesanstalt (PTB), the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), and Istituto Nazionale di Ricerca Metrologica (INRIM) promote global consistency of reference values for angular rate and acceleration (See Table 7).

Table 6.

Comparative taxonomy of co-adaptive control strategies.

Table 7.

Principal standards and institutional references relevant to rehabilitation robotics.

Metrological reliability extends beyond device-level accuracy. GUM and the GUM–MC supplement provide a structured approach to propagate uncertainty through kinematic and dynamic estimations. Type A evaluation quantifies statistical repeatability, whereas Type B incorporates manufacturer specifications, calibration data, and model assumptions. For illustration, consider a two-link arm with joint angles and derived from IMU quaternions and with mean bias and standard deviation . The combined uncertainty on a reconstructed joint angle , evaluated by GUM–MC over draws, yields a coverage interval . This result indicates that 95% of estimates fall within of the true joint orientation and explicitly attributes contributions from noise, bias, and alignment (RQ3).

7.2. Algorithmic Transparency and Ethical Accountability

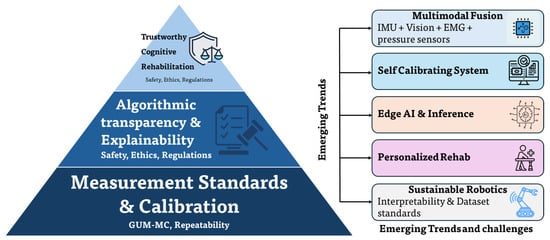

Reliability also depends on algorithmic transparency and interpretability. In the context of upper-limb rehabilitation robotics, explicability refers to the capability of an intelligent system to expose the rationale, confidence, and influencing factors underlying its estimations or control decisions in a form that is meaningful to clinicians, engineers, and regulators. Explicability extends beyond model interpretability by linking internal computational representations to biomechanical variables, uncertainty bounds, and observable system behaviour [4,38,75]. Explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) frameworks provide post hoc analyses of deep and hybrid estimators, enabling clinical inspection of decision relevance and detection of anomalous behaviour [37]. Models that infer joint kinematics or patient intent can expose feature attributions and calibrated prediction intervals or trust scores to support therapy evaluation [28,90]. Integration of uncertainty-aware prediction with XAI yields interpretable confidence and enables a balance between autonomy and oversight [37] as depicted in Table 8 and Figure 8.

Table 8.

Sub-roadmaps with TRL progression and quantitative targets.

Figure 8.

Integrated traceability and trust pyramid with emerging research trends. The layered structure illustrates the traceability chain (sensor, calibration artefact, metrology laboratory, SI unit), uncertainty quantification (GUM and GUM–MC propagation), explainability (XAI tools such as SHAP and LIME), and ethical–regulatory references (GDPR and ISO 27701). Annotations link each layer to relevant international standards and institutions.

Concrete examples of explicability in rehabilitation scenarios include attribution-style analyses indicating which inertial channels or temporal segments dominate joint-angle estimation [28,33], confidence-aware assistance modulation where elevated estimator uncertainty triggers more conservative controller behaviour (e.g., reduced stiffness or assistance) to preserve safety and stability [9,91], and intent classifiers that expose probability distributions over task hypotheses rather than discrete commands to support supervised decision-making [90]. In hybrid systems, explainability also emerges through operational transparency, where controller adaptations can be traced to specific changes in estimated kinematics, uncertainty growth, or detected deviations in movement quality/compensatory patterns, enabling clinician-facing audit trails and interpretability at the system level [37,38,75].

Representative XAI tools include SHAP (Shapley Additive Explanations), LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations), and Grad-CAM (Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping) for temporal sequences. When applied to wearable-sensor-based models, these tools enable inspection of temporal relevance, sensor contribution, and robustness to perturbations, supporting verification of clinically plausible behaviour [28,33,37]. Reporting of explanation fidelity and stability, for example an -style agreement between explanations and held-out perturbations, provides audit trails for regulatory evaluation.

Ethical and regulatory dimensions further shape system design. ISO 13482 [97] and IEC 80601-2-78 [98] establish baseline requirements for mechanical safety, fail-safe operation, and human exposure limits. Conformity assessment requires documentation of calibration chains, uncertainty models, and safety-testing protocols. Privacy and data governance are essential when multimodal sensing involves electromyography, vision, or cloud-linked digital twins. The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) [105] and ISO 27701 [104] principles motivate explicit consent, local processing or encryption for physiological data, and limited data retention. Edge inference aligns with both energy constraints and privacy objectives.

7.3. Cybersecurity and System Resilience in Rehabilitation Robotics

Cybersecurity is a fundamental requirement for the safe and reliable deployment of upper-limb rehabilitation robotics, particularly as these systems increasingly rely on networked sensing, embedded intelligence, and adaptive control [37,62]. In this context, cybersecurity concerns the protection of data integrity, communication pathways, computational models, and control logic against unauthorized access, manipulation, or disruption that may compromise measurement validity or patient safety [38,74].

Wearable-sensor-based rehabilitation systems present multiple attack surfaces, including wireless sensor links, firmware update mechanisms, on-device inference pipelines, and cloud-connected digital twins [23,40,80]. Documented threat vectors include signal injection or replay attacks on inertial data streams, tampering with learned model parameters, unauthorized modification of controller settings, and denial-of-service conditions that interfere with real-time operation [29,43,96]. These events can directly degrade kinematic accuracy, invalidate uncertainty estimates, and affect the safety of assistive control [4,9,75].

From a metrological standpoint, cybersecurity breaches may invalidate traceability by corrupting calibrated sensor outputs or associated uncertainty metadata [10,11,74]. Secure system design therefore requires authenticated devices, encrypted communication, and integrity verification of both raw measurements and derived kinematic quantities [38,74]. Hardware-based roots of trust, secure boot procedures, and signed firmware updates are increasingly adopted to preserve the integrity of embedded sensing and inference components [65,66,81].

At the algorithmic level, resilience is supported through anomaly detection on sensor residuals, cross-validation between redundant modalities, and confidence-aware fail-safe mechanisms [24,32,95]. In such schemes, abnormal data patterns or elevated estimation uncertainty trigger conservative control actions or controlled shutdown, preventing uncontrolled physical interaction [9,37,94].

Regulatory frameworks further motivate explicit treatment of cybersecurity. Standards such as IEC 62304 [97] for medical device software (Euleria Rehab Suite) life-cycle processes and emerging cybersecurity guidelines for networked medical devices require documented threat assessment, risk mitigation strategies, and post-deployment monitoring [37,38]. Integrating cybersecurity with traceability, uncertainty quantification, and explainable intelligence is therefore essential for certification, clinical acceptance, and long-term deployment in clinical and home-based rehabilitation environments [74,79,80].

7.4. Emerging Technological Trends

Recent research trends converge on integrated pipelines that couple sensing, computation, and human factors under measurable reliability constraints [37,38]. Self-calibrating IMUs and alignment-free kinematic models reduce setup time and operator dependence [22,27,49,54]. Multimodal fusion that combines IMU, electromyography, vision, and tactile sensing increases robustness to occlusion and noise and supports intent inference under naturalistic conditions [32,82,90,95]. Digital-twin architectures connect sensor data to biomechanical simulation to support individualized planning and monitoring, but they require validation protocols that preserve traceability between virtual and physical representations [5,10,11,40].

Edge artificial intelligence supports local inference through efficient temporal models (e.g., temporal convolutional or recurrent architectures) and TinyML-oriented pipelines that enable real-time estimation under strict power and memory budgets, reducing reliance on continuous cloud connectivity [43,44,68,71,73]. Sustainable deployment further depends on the joint consideration of sensing rate, inference cost, and actuation scheduling, where energy-aware strategies can trade estimation fidelity against computational load while maintaining clinically usable kinematic outputs [41,75,93].

7.5. Grand Challenges and Open Directions

Several challenges remain unresolved. Interoperability across heterogeneous sensors and robotic platforms limits large-scale validation. Dataset scarcity and non-uniform labelling conventions hinder reproducibility of artificial intelligence models. Reliable in-home evaluation requires context-aware safety mechanisms and remote verification of calibration status. Ethical concerns include transparent data sharing, informed consent for longitudinal monitoring, and mitigation of algorithmic bias in model training. Quantified bias audits, for example differential error between subgroups, are recommended to evidence fairness and align with emerging standards on bias management in artificial intelligence.

Addressing these challenges calls for coordination among metrology institutes, clinical centres, and manufacturers. Common data formats, uncertainty-reporting standards, and benchmark protocols are required to establish comparable performance metrics. Future cognitive rehabilitation systems are expected to integrate traceable measurement, transparent learning, and adaptive control into a framework that is auditable, interpretable, and patient-centred. Collaborative platforms such as the European Metrology Cloud and working groups on metrology for intelligent systems are promoting reference datasets and uncertainty-annotation schemas that support traceable and explainable rehabilitation robotics toward 2030.

8. Future Outlook and Research Roadmap to 2030

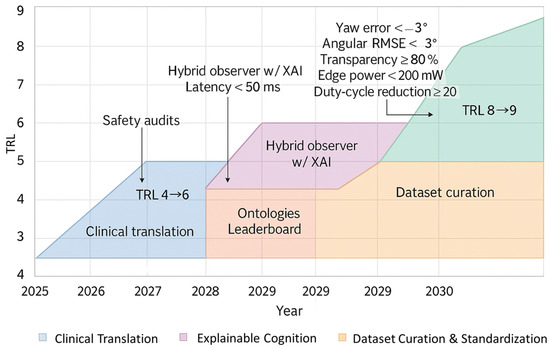

Upper-limb rehabilitation robotics is positioned to transition from laboratory-validated prototypes to clinically reliable, home-deployable ecosystems by 2030. Progress depends on closing research gaps identified across Section 3, Section 4, Section 5, Section 6 and Section 7, including heterogeneous calibration procedures, limited uncertainty reporting, magnetometer vulnerability, non-standard datasets and labels, insufficient validation on pathological movement, incomplete human–robot co-adaptation metrics, and immature governance for privacy and explainability. This section consolidates a roadmap that aligns technical advances with metrological traceability and clinical interpretability, framed by Technology Readiness Levels (TRL) (RQ5). In addition to domain-specific advances, emphasis is placed on cross-cutting milestones that integrate sensing, modeling, control, and governance into coherent and verifiable system-level endpoints. Beyond performance-driven objectives, the roadmap explicitly incorporates system-level trust requirements, including cybersecurity, data integrity, and resilience against malicious or accidental perturbations affecting sensing, inference, and control.

8.1. Roadmap Structure and Quantitative Targets

The roadmap adopts TRL 1 to TRL 9 and anchors progress to quantitative indicators as depicted in Table 9 and Figure 9. Global targets by 2030 are:

Table 9.

Roadmap matrix: actions, metrics, and TRL progression.

Figure 9.

Technology-readiness roadmap to 2030. The horizontal axis indicates calendar year and the vertical axis indicates TRL. Coloured bands show sub-roadmaps for sensing standardisation, dataset curation, explainable cognition, and clinical translation. Milestones label quantitative targets in accuracy, latency, power, and uncertainty.

- Angular root mean square error (RMSE): elbow and humerothoracic < 3° at 95% coverage; scapulothoracic < 5°.

- Closed-loop inference latency: <50 ms end to end; inner torque-loop delay < 2 ms.

- Edge consumption: <200 mW for 100 Hz multi-sensor inference; actuation duty-cycle reduction ≥ 20%.

- Uncertainty reporting: per-joint cards including Type A, Type B, and GUM–MC envelopes; clinical prediction-interval (PI) calibration error < 5%.

- Explainability: XAI fidelity on clinician-defined features; transparency score ≥ 80%.

- System trustworthiness: documented linkage between sensing uncertainty, estimator confidence, controller constraints, and safety margins across all TRL stages.

8.2. Horizon 1 (2025–2027): Standardisation and Dataset Curation

The initial horizon prioritises reproducible baselines to enable fair comparison and regulatory-ready reporting.