1. Introduction

Due to the profound societal costs of violence and the loss of human life in public spaces, there is now a substantial body of work on surveillance technologies that aim to detect, predict, or deter harmful events. Across public spaces, the evidence base shows that surveillance can reduce crimes and end-to-end latency between anomaly detection and alert issuance [

1]. Complementing cameras, randomized field work indicates that simply increasing visible guardianship (short, frequent private-security patrols in transit hubs) can deter offenses at scale, underscoring how human presence and routine activity patterns interact with place-based risk [

2]. Framing these interventions within broader policy trade-offs, crime imposes substantial tangible and intangible social costs—medical care, lost productivity, fear and quality-of-life harm—so even incremental prevention effects can yield large welfare gains [

3].

Early multimodal work in weakly supervised audio–visual (A/V) violence detection set the tone by showing that aligning sound and vision—even with coarse video-level labels—yields practical gains under real surveillance conditions. A seminal example is the ECCV study that explicitly taught models to “not only look, but also listen,” demonstrating how audio cues often precede or reinforce visual signals of aggression [

4]. Subsequent efforts fused visual frames with audio embeddings to stabilize detections when either stream was noisy or occluded, establishing that cross-modal fusion can outperform single-modality baselines in realistic footage [

5]. Building on this, dependency attention mechanisms were introduced to learn when and how modalities should influence each other, which is especially valuable when violent events unfold off camera but remain acoustically salient [

6]. Parallel work generalized weak supervision to broader settings, showing that careful cross-modal learning can approach a strongly supervised performance without dense annotations [

7], and even extending the embedding space into hyperbolic geometry to better structure hierarchical relations among violent and non-violent events [

8]. Complementary designs that emphasize optical flow for motion salience provide stronger visual grounding when camera shaking and crowd movement complicate the scene [

9]. The overall direction and gaps in this domain are synthesized in recent surveys, which document datasets, architectures, and pitfalls (e.g., context bias, staging effects, domain shift) in violence detection for surveillance [

10]. Meanwhile, engineering-focused work has improved computational efficiency so that A/V models remain deployable on edge devices that are common to camera networks [

11] and has broadened to crowd anomaly detection with joint audio–visual representation, learning to capture collective dynamics rather than individual actions [

12]. A later paper broadened the weak-supervision agenda with more experiments, underlining the scalability across scenes and label regimes [

13].

In parallel, audio-only research has matured rapidly for situations where cameras are occluded or privacy-restricted. Lightweight deep networks have shown that real-life audio carries distinctive violent signatures, even under noise and reverberation, enabling deployment on modest hardware [

14]. Transfer learning and targeted augmentation further boost performance under compute constraints, a recurring requirement in large-area sensor networks [

15]. Beyond ad hoc models, a new family of general-purpose audio backbones—audio spectrogram transformer (AST) [

16], hierarchical token-semantic AT (HTS-AT) [

17], and streaming audio transformers for online tagging [

18]—have become strong foundations for surveillance tagging pipelines. Techniques like PSLA refine pretraining and sampling strategies to reduce label noise sensitivity [

19], while PANNs offer robust CNN-based alternatives, pre-trained on AudioSet, that transfer effectively to downstream events that are common in public safety scenarios [

20].

A complementary wave harnesses language-supervised audio embeddings, aligning audio with natural language semantics to unlock zero-shot and flexible labeling: natural language supervision for general-purpose audio representations shows that tying audio to text space improves generalization across tasks [

21], while Wav2CLIP leverages vision–language pretraining to create robust cross-modal audio embeddings that are usable without extensive task-specific labels [

22]. For surveillance, these methods help “describe what you hear” in text that downstream decision agents can reason over, including subtle acoustic cues (e.g., crowd panic, metal impacts) that are not present in fixed taxonomies.

Given policy sensitivity, gunshot and explosion detection remains a focal area. Studies targeting gunshot audio in public places highlight the feasibility of identification/classification under realistic conditions and propose architectures for rapid localization and alerting [

23]. Work that contrasts gunshots vs. plastic bag explosions quantifies confusability and shows how deep models discriminate transient acoustic signatures that might otherwise trigger false alarms [

24]. A recent forensic science review expands the pipeline—detection, identification, and classification—into legal and investigative settings, outlining standards and evidence reliability challenges that directly impact real deployments [

25]. More generally, sound event detection for human safety in noisy environments catalogs the algorithmic adaptations (denoising, robust features, temporal context) that surveillance-grade systems need to maintain precision in the field [

26].

Beyond event cues, the affective and physiological dimension of audio has implications for post hoc triage and human-in-the-loop review. A systematic review synthesizes how acoustic correlations of speech (e.g., F0, spectral roughness, prosody) track negative emotions and stress, providing a principled basis for interpreting screams, pleas, and panic under duress [

27]. Controlled studies validate the fundamental frequency (F0) as a marker for arousal/valence and body-related distress [

28], while multimodal stress detection work demonstrates how cross-signals can raise reliability in real time [

29]. In the wild, daily stress detection from real-life speech shows that acoustic–semantic signals remain predictive outside the lab [

30], and benchmarks on emotion/arousal under stress probe the limits of speech-only recognition for operational use. Particularly striking for public-safety acoustics, scream-like roughness is shown to occupy a privileged niche in human nonverbal communication, which aligns with strong salience in detection models and human monitoring alike [

31,

32]. Although not strictly about public spaces, applications that detect harmful situations for vulnerable populations using audiotext cues reinforce the value of linguistic context when physiological or emotional markers are ambiguous [

33].

Finally, the systems perspective matters: moving from research to real-time city deployments entails robust streaming, edge computing, and scalable model management. A recent smart city case study demonstrates the real-time acoustic detection of critical incidents on edge networks, distilling practical lessons about latency budgets, bandwidth, privacy, and alert governance that are essential for any large-scale surveillance roll-out [

34].

Putting it together, today’s surveillance research converges on three pillars: (i) multimodal fusion to stabilize detection under occlusion and noise, (ii) foundation-style audio models (AST/HTS-AT/streaming transformers and language-supervised embeddings) to improve transfer and reduce annotation needs, and (iii) policy-aware event vocabularies (gunshot, explosion, glass break, crowd panic) with stress/affect cues to triage severity. The field is actively closing the gap between benchmark gains and operational reliability—addressing domain shift, compute limits, and the social consequences of false alarms in public spaces. That trajectory is essential for evidence-based deployment that respects both safety and civil liberties.

Our contribution is applied in nature: we integrate established signal processing algorithms in a novel and coherent way to address the still unresolved challenge of real-time, online, and interpretable incident detection, where interpretability directly supports accountability. We focus on on-line hazard detection and introduce an audio-only pipeline that converts heterogeneous acoustic evidence—AST sound events, CLAP/affect cues, diarization/overlap, prosody/pitch, and optional ASR—into a streaming, human-readable timeline consumed by a compact LLM under an explicit evidence hierarchy. Unlike end-to-end classifiers, this perception to text middleware decouples tagging from decision-making, enabling zero-shot extensibility via prompts, interpretable rationales, and real-time operation. The decision layer reasons over a rolling context with persistence and aftermath cues, issuing 2 s bin decisions and a session-level verdict that resists spurious tags and ASR dropouts. By prioritizing sound events, interactional, and prosodic signals over speech text, the system remains effective when speech is absent or unintelligible—common in street footage—while guard-railing against emotive false alarms. In few words, the practical novelty is in the streaming, interpretable, rule-constrained LLM adjudicator that fuses heterogeneous audio-to-text tokens for bin-level hazard decisions in real time. Evaluated on the X-Violence available on HuggingFace [

35] (a part of it with real-life videos containing audio tracks), the approach demonstrates competitive accuracy with low latency, offering a practical, privacy-preserving route to deployable acoustic surveillance. These videos include an unknown and time-varying number of concurrent audio sources, low-quality and reverberant recordings, faint sources, and overlapping, multi-speaker speech, distorted by stress or agony.

2. Materials and Methods

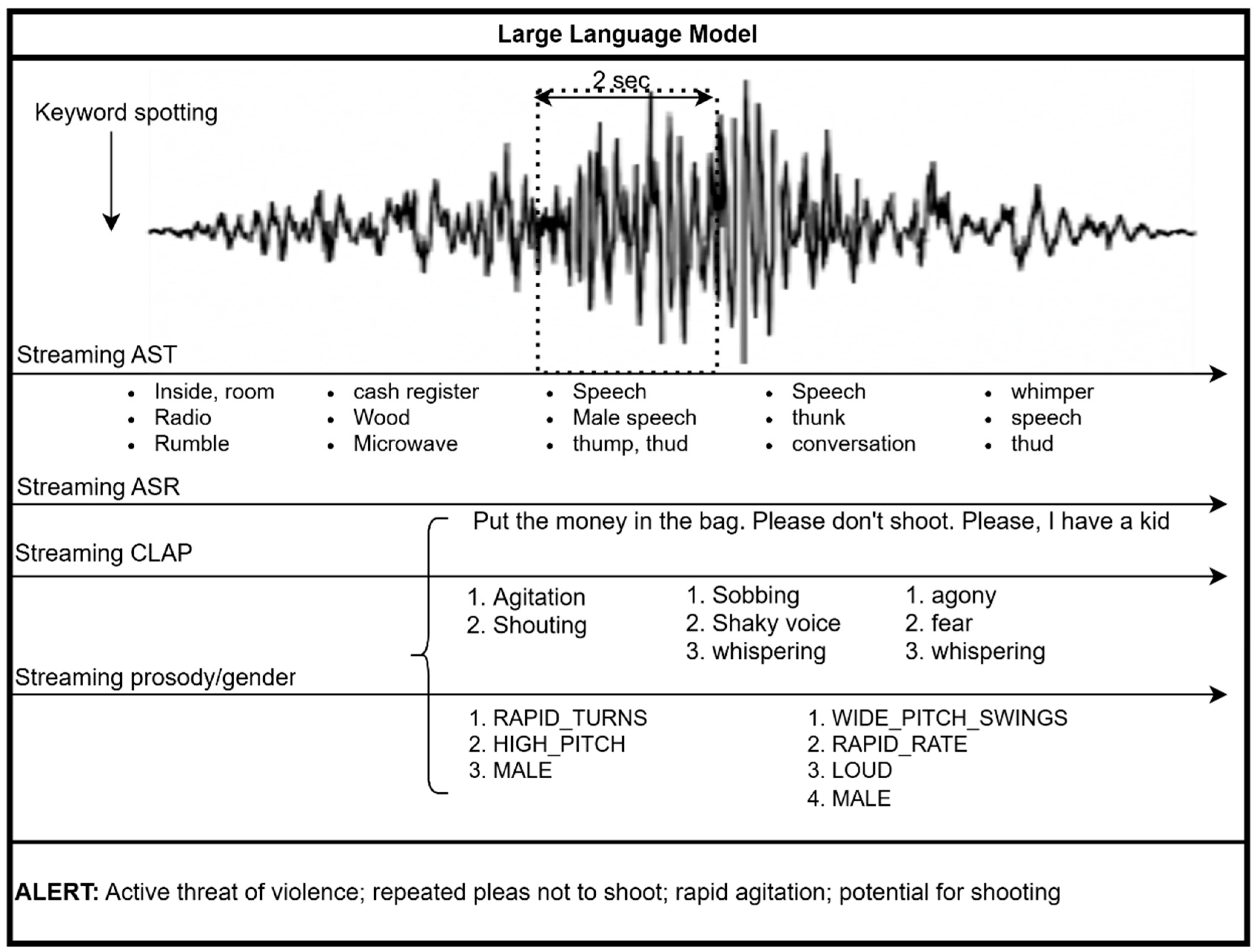

Our approach depicted in

Figure 1 is based on integrating open-source audio processing algorithms that do not require further training or adaptation. These algorithms independently compress the audio stream in complementary ways into text labels. A ChatGPT5-nano LLM receives a rolling window of these tokens in a streaming decoding version so that it can start interpreting what happens as audio–visual content evolves in real-time. Because all modalities ultimately yield text labels, the LLM can naturally fuse heterogeneous inputs—even when they appear intermittently. With structured prompting, it can integrate cues, count sources in audioscenes, and intentionally ignore signals that are semantically out of context. This is critical in complex auditory scenes, where cues may originate from sources unrelated to our single decision question: “is there a life-threatening incident?”.

2.1. Streaming AST

The classical audio spectrogram transformer (AST) model [

16] is optimized for offline tagging with a global 10 s context and quadratic self-attention, which implies large memory/compute, an intrinsic response delay on the order of the input window, and poor efficiency if naively recomputed for sliding online use. It is not applicable to online identification of streaming events. If [

16] is forced to short chunks, its accuracy degrades. In contrast, a streaming AST (SAT) [

17,

18] uses a ViT backbone with Transformer-XL-style chunked recurrence and cache, and is trained on AudioSet through a three-stage pipeline: (1) masked-autoencoder pretraining, (2) full-context finetuning on 10 s clips, and (3) streaming finetuning with pseudo-strong labels distilled at finer temporal scales so the model learns to emit stable predictions with short context. The resulting system operates at 1–2 s segment lengths (reporting per-chunk scores while carrying a compact past-state), achieving near-full-context tagging quality with far lower latency, memory, and flops. The targeted applications are online audio tagging scenarios like the one that this work handles. The streaming AST orchestrates all further stages. General audio labels of the AudioSet ontology are kept, whereas when ‘speech’ or ‘monologue’ or ‘conversation/narration’ appear in a label, this triggers speech transcription and emotional tagging of the speech segment. If the audio is not recognizable by the ASR module, it remains as a general ‘speech’ label but emotional analysis that is based on paralinguistic content still applies. In our setting, we keep the labels from the three highest ranks every 2 s, as we wish to catch possible overlapping in frequency audio events.

2.2. Streaming ASR

We employ a streaming version, namely faster-whisper, that decodes speech as it arrives. Integration with the overall pipeline is achieved through a streaming API that serializes recognized tokens as they are produced, enabling direct coupling with the conversational and decision modules. In this configuration, the speech recognition component contributes not only lexical content but also timing and confidence metadata, which are subsequently aligned with prosodic and acoustic-event features for joint interpretation. The model operates continuously on short overlapping audio buffers, providing incremental text output with minimal latency. The decoding beam size is fixed to one, which prioritizes speed and temporal responsiveness over marginal accuracy gains that are achievable through wider beams. This configuration also enhances robustness in noisy and non-stationary acoustic environments, where large beams tend to amplify spurious hypotheses and increase processing delays.

Automatic language detection is enabled by setting the language parameter to ‘auto’, allowing the model to adapt dynamically to multilingual recordings without prior specification of a target language. This design choice aligns with the objective of language independence and avoids imposing linguistic assumptions that could bias detection outcomes. The module further employs Whisper’s built-in speech-segment filtering, which rejects non-verbal or low-energy regions (e.g., silence, background noise, or purely environmental sounds) from being passed to the language model interface. This reduces unnecessary computational load and ensures that only semantically meaningful segments are processed downstream. In applications where we suggest a wakeup keyword, e.g., in shops, we used a very reliable keyword spotter from PicoVoice Porcupine to deploy a custom wake word (

https://picovoice.ai/platform/porcupine/, accessed on 23 December 2025).

2.3. CLAP

We build on contrastive language–audio pretraining (CLAP) [

36], which aligns audio and text in a shared space using contrastive learning, enabling open-vocabulary (zero-shot) classification by comparing an audio window to natural language prompts. In practice, we use the public laion/larger_clap_music_and_speech checkpoint via the HuggingFace zero-shot audio pipeline. CLAP’s training recipe (LAION-Audio-630K, text–audio encoders, contrastive objective) supports scoring short windows against prompt sets without task-specific fine-tuning, which suits our streaming setup.

Our implementation frames each 2 s window with the hypothesis template, “This audio expresses {}” evaluates a candidate set that combines affective phrases and neutral distractors, aggregates per-flag scores by taking the max over paraphrases and emits both a compact flag list and a human-readable description with the top contributing phrase. An energy gate skips low-RMS regions and per-flag multipliers, modestly boosting high_agitation and stress before thresholding. This design yields interpretable, auditable outputs in real time and provides a simple calibration handle via the neutral maxima.

We use a flag taxonomy that organizes cues into six buckets (stress, pain, despair, cry, agony, high_agitation), each populated with multiple paraphrases (e.g., “stressed breathing,” “hyperventilation,” “pleading voice”). This is well-matched to CLAP’s prompt-based zero-shot behavior and improves recall across lexical variation. The neutral set (“calm talking,” “silence,” “soft music,”, etc.) was used for anchoring scores. Subsequently, we apply a ‘reasoning canon’ that map-collapses heterogeneous forms into stable machine-readable tokens (e.g., “frantic shouting” → shouting, “crying in pain” → crying_pain) for downstream fusion (e.g., LLM reasoning, rule engines) and for audit trails.

2.4. Prosodic Cues and Speakers’ Flags

How we say something often incorporates our intentions and, therefore, analyzing prosodic cues of speech is of interest to our application. The prosodic modules add language-independent evidence about arousal and distress by quantifying pitch, loudness, speaking-rate, and pausing dynamics in short (2 s) windows and emitting interpretable flags for downstream fusion. These are extracted only for the audio part that is tagged by the AST as speech. The pitch/loudness script estimates F0 every 10 ms with torchcrepe/CREPE [

37,

38], uses periodicity to gate unreliable frames, applies Viterbi smoothing, and then computes robust statistics per bin: a median robust-z of F0 to flag [HIGH_PITCH] or [LOW_PITCH], the F0 standard deviation in Hz to flag [WIDE_PITCH_SWINGS], and a waveform RMS gate to flag [LOUD]. Our streaming pitch module operates in online mode by analyzing the audio as it arrives in fixed-length windows (e.g., 2 s) and producing a decision for each window before any subsequent data are seen. Incoming audio is read incrementally, resampled on the fly to the pitch estimator’s target rate, and pitch with a confidence measure is computed only for the current window. To normalize pitch within a session, the system maintains a bounded, rolling baseline built exclusively from the voiced frames observed in prior windows. Robust statistics (median and median absolute deviation) from this history yield per-window z-scores that adapt to the speaker and environment. Flags such as high/low pitch, wide pitch swings, loudness, and an optional gender tag are derived from the current window’s features, relative to the historical baseline. Τhe baseline is updated only after a window’s outputs are finalized, preventing look-ahead leakage and preserving causal processing. This design enables deployment on live streams with predictable latency, a bounded memory footprint, and no dependence on knowledge of the total recording duration.

In confrontational settings, speakers often exhibit rapid turn-taking, frequent interruptions, overlapping speech, and multiple simultaneous talkers—patterns that can signal escalating agitation [

39,

40,

41]. Therefore, only in the speech segment, we apply pyannote—a speaker-diarization pipeline—to convert the waveform into time-stamped segments labeled by speaker identity. The algorithm maintains the set of currently active speakers and integrates the duration during which at least two speakers are simultaneously active to obtain the overlap percentage. It also records the maximum size of the active set (peak concurrency). An interruption is counted whenever a new speaker starts, while another is already active. Speaker switches are counted when the identity of a single active speaker changes across contiguous sub-intervals. These windowed statistics are then normalized by window length (e.g., interruptions per minute) and compared to preset thresholds to emit interpretable flags such as HIGH_OVERLAP, MANY_SPEAKERS, INTERRUPTION, and RAPID_TURNS, along with a compact textual summary. A deterministic tie-breaking rule handles coincident starts and ends to keep the counts stable and conservative. All processing stages end up with a word description, as gathered in

Table 1.

2.5. LLM Prompting

Although AST, CLAP, and emotional cues are discretized into a limited set of predefined labels, speech transcriptions introduce a much richer and more variable token space, therefore, the tracking of a limited number of keywords and accumulation of their corresponding probabilities in a rolling short memory configuration is not viable, as in [

34]. The LLM receives all text tags and tries to co-interpret them to reduce false alarms. False alarms are reduced by integrating many text labels that are semantically related before supporting a hazardous event instead of relying on a single label (e.g., ‘gunshot’). The system needs to discern a scenario, even in the presence of a mistake from an upstream scenario (usually from AST or ASR). In our framework, when speech is detected, transcribed text and other mapped audio cues are jointly interpreted through a large language model (LLM), using hierarchical prompts. Rather than relying solely on unconstrained inference, the LLM is guided by a structured evidence hierarchy that conditions its reasoning on different extracts of audio context. This approach leverages the LLM’s semantic understanding to evaluate whether the mapped sensory reality entails a potential hazard, while maintaining interpretability through an explicit prompt design. The vision modality would normally provide contextual grounding for the application environment. However, since this study focuses exclusively on audio modality, we design different prompts tailored to broad operational categories. It is suboptimal to rely on a single, generic prompt for all environments (e.g., industrial plant, retail store, sports event, or traffic surveillance), because a situation’s hazard level depends heavily on its context (for instance, a scream in a basketball game differs from a scream in a library).

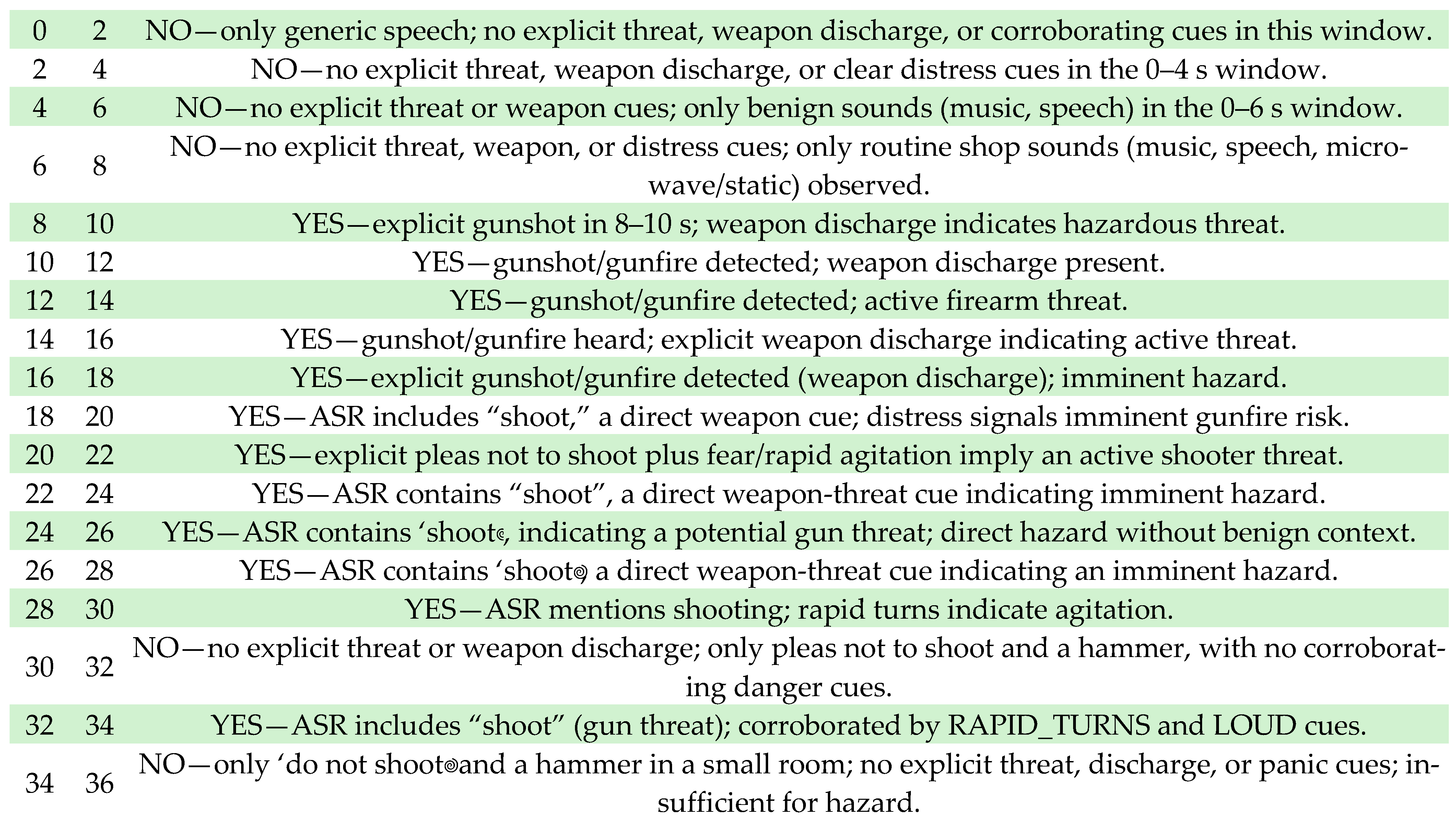

The prompts are formulated as explicit evidence hierarchies with fixed decision rules, ensuring that the model functions as a constrained adjudicator. Their structure allows for specific informational cues to be weighed differently, measure their persistence or even ignored, depending on their relevance to the operational setting. Concretely, the prompt for gunfight detection ranks audio-event tags as the highest, automatic speech recognition second, and emotion/prosody as supporting only. The decision process is implemented through a structured pair of messages to the model, consisting of a domain-specific system prompt and a user prompt that encodes the recent event timeline. The Python 3.11 script constructs a rolling window of 2 s bins, converts each bin to a textual line with time span and key labels, concatenates these lines into a “Timeline” block, and appends a strict instruction that the model must answer on a single line, starting with either YES or NO plus a brief rationale, which allows for automatic conversion of each response to a numeric verdict and a clip level label.

The policy specifies three hazard pathways: (A) direct hazard from conclusive acoustic events (e.g., gunfire, explosion), which defaults to YES without speech evidence (B) nonverbal assault requires an “impact cluster,” together with distress context, and (C) speech-led hazard requires explicit danger language corroborated by acoustic or emotional cues. Prompt formulations also describe benign background conditions for each environment and introduce explicit override cases in which otherwise dangerous sounding events, such as gunshots or explosions, are reinterpreted as non-hazardous only when accompanied by clear contextual evidence, such as training range instructions or celebratory fireworks with cheering and no distress. Benign overrides are narrowly defined (e.g., fireworks with festive context, training/range/drill cues) and can reverse a YES only when the benign context is strong and internally consistent. Conflicting information is resolved by giving priority to high-reliability cues, such as weapon discharge tags or explicit verbal threats over weaker emotional or prosodic signals, by demanding corroboration when cues are ambiguous, and by defaulting to non-hazard decisions when only low-priority evidence is present, which together enables the prompt to systematically disambiguate between true dangerous events and noisy but benign urban or commercial soundscapes. Conflict-resolution rules further constrain behavior: emotional cues never trigger YES alone, isolated words are ignored, and the policy prefers precision over recall, except for potentially lethal events. The diarization and overlapping speakers indicators are used only as corroboration, not as primary triggers. This organization yields interpretable, auditable decisions under noisy real-world conditions by binding the LLM to a ranked, rule-based fusion of audio tags, speech content, and prosodic signals with a strict output schema. An example of such structured prompting is in

Appendix A-(b).

While the GPT API supports token-streaming for partial, incremental responses, we use a sequential invocation scheme in this proof of concept. The system masks and forwards features produced by upstream modules to a lightweight GPT model (ChatGPT5-nano in our prototype) via its API, maintaining a fixed system prompt and a rolling context comprising the current bin and a number of preceding ones (i.e., four 2 s windows). This design preserves online behavior (decide as it happens) with bounded state while simplifying integration and error handling. Our approach does not rely on any model-specific features and any modern, high-end LLM can be used in place of ChatGPT.

2.6. Data

Only real-life videos from the X-violence dataset of HuggingFace [

35] are included, excluding commercial movie material. The subset we use excludes extracts from professional films because, in cinematic production, audio is post-processed to enhance narrative coherence and does not represent real operational conditions as those of CCTV surveillance cameras and mobile phones do. We selected videos with continuous audio presence and excluded clips where sound is absent, such as traffic accidents without recorded impact audio, as these are not suitable for the present objectives. Visual information is not used by our system, and all classifications rely exclusively on audio data extracted from videos. Restricting the analysis to audio has both advantages and limitations. The main advantage is that in many practical applications, visual input is unavailable or impractical to acquire, while microphone-based systems are low-cost and easily deployable. The limitation is that visual content often provides decisive contextual cues that audio alone may fail to capture or disambiguate.

We extracted and manually tagged positive and negative for life hazard videos from the X-Violence dataset with the only criterion being that the video has audio. We extract the audio to mono, wav format at 16 kHz, since all algorithms but CLAP expect this sample rate. We organize it in four broad distinct categories, for which we have different prompts for the LLM. This way, we notify the system of the area that the application will operate (shop surveillance, athletic event surveillance, urban surveillance, and combat zone). This could also be provided partially if image data were used or the LLMs advance to the point that they learn to disregard part of the information while organizing partial information to realistic scenarios. The algorithms (see

Appendix A-(a)) can be applied to any video with audio content.

Gunfight detection (17 videos).

We tested the system on video segments containing gunfights and explosions that posed immediate danger to human life.

Urban surveillance (120 videos).

This subset included recordings from dense urban settings such as busy streets, metro stations, and open markets, characterized by a mixture of voices, traffic, moving crowds, street performance, gatherings, and ambient music. The objective was to evaluate the system’s robustness in distinguishing violent or hazardous events (e.g., clashes, riots, accidents) from benign urban noise. In particular, protest scenes were examined to assess whether the model could discriminate between peaceful demonstrations and acts involving vandalism or violent conflicts. A total of 45 videos contain clearly audible violent acts and 75 contain soundscapes that contain non-threatening situations.

Sports facilities (36 videos).

Sports arenas are acoustically intense environments that are dominated by shouting, cheering, and frequent impact sounds. Our system in such spaces is tuned to look for mass shooting, explosions, and prolonged vandalism. To evaluate resilience to false alarms, we included recordings from hockey, basketball, and football matches—contexts that often contain sharp thuds and vocal agitation, both from players and the audience. We have split this corpus into 16 movies where players indulge into altercations and 20 typical games. However, sports are highly supervised games and are well-guarded by police and surveillance cameras and all cases are negative for life-threatening situations, although in some, altercations are present.

Indoor surveillance (8 videos).

This scenario focused on confined environments such as shops, offices, or residential interiors where armed robbery, mugging, or violent altercations occurred. The model was tuned to following multi-stage acoustic events (impact sequences, cries, object collisions) in real time to capture the temporal evolution of the situation.

2.7. Hardware

All experiments were conducted on an Intel i7 laptop equipped with an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3060 GPU. The key components—Streaming AST and ASR—are highly efficient. As a benchmark, Streaming AST [

18] processes a 1 h and 9 min recording in 32 s using the SAT_B_2s model, while Faster Whisper processes the same recording in 58 s using large-v3.

We analyze the processing time further, but it is important to note that these figures represent a maximum potential delay (upper bound) because: (a) downstream feature extraction (CLAP, ASR, and prosody) is triggered only when AST detects speech; and (b) these modules can execute in parallel while the next chunk is being received. Although available as streaming versions, we have not optimized for asynchronous parallel processing in this proof-of-concept paper.

In

Table 2 we report on per-module latency to demonstrate that the system fits within the constraints of consumer hardware. LLM response times can vary depending on the model and network connectivity for API calls and, therefore, we would not obtain a meaningful, reliable measure. To mitigate unpredictable network delays, we present measurements using a local Llama 3.2 (1B parameter version, 2.0 GB in size) model (see

Appendix A-(a), for code). Llama 3.2 is a lightweight, instruction-tuned large language model developed by Meta. It was accessed via the Ollama framework, utilizing the llama3.2:latest build, optimized for local inference with reduced memory footprint.

3. Results

We evaluate qualitatively on real-world clips and report confusion counts to demonstrate plausibility and traceability. Our focus is design clarity, interpretability, and reproducibility, not optimality (we do not pursue SOTA). We upload all processing stages and automatically annotated videos in ZENODO (see

Appendix A-(a)). We force the LLM to make a clear decision and a brief explanation on where it is, based on its decision for transparency and traceability, and we embed its 2 sec output as captions in the movie. For the clarity of the manuscript, we analyze a case to clarify what the system’s input and output is below. Our example is an armed robbery in a shop. A male enters a shop and is armed with a gun. He points the gun at the victim and asks for all the money.

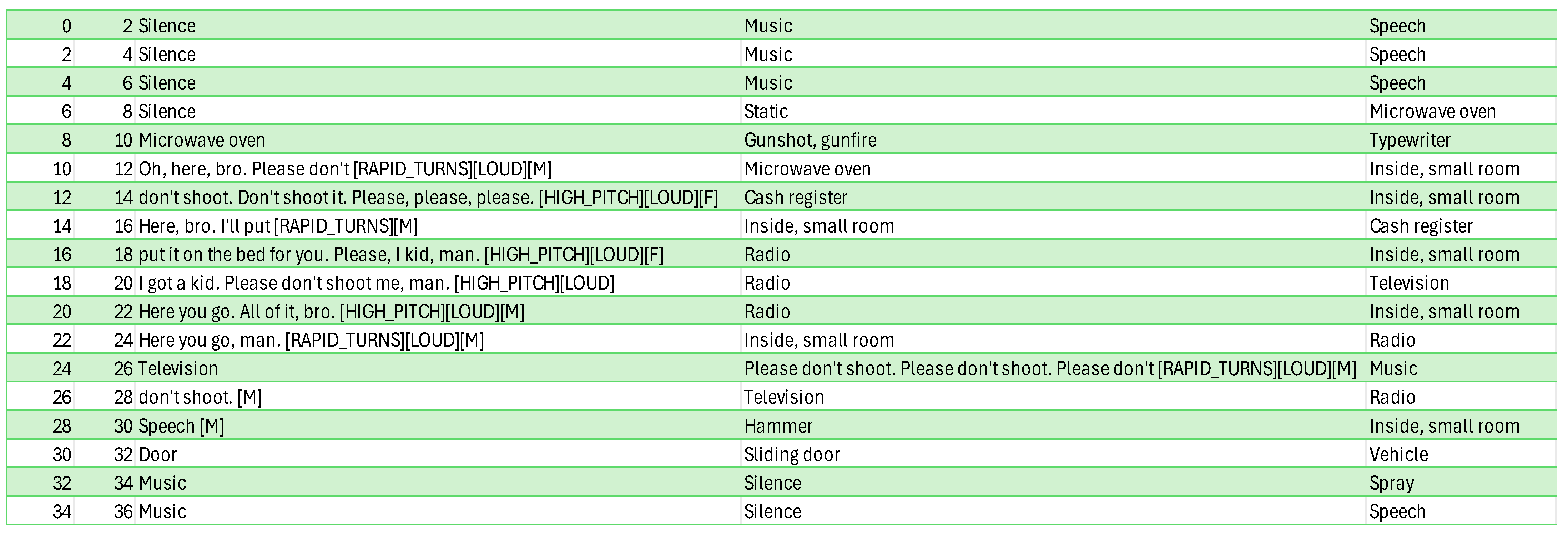

Details: The audio of the video is of low quality. The perpetrator and the victim keep relatively calm but have anxious voices (no shouts or screams that would help an audio-based surveillance system). The sound of an arming gun is clearly heard. AST observes a gun-oriented sound but misclassifies it as a gunshot. The speech cues originate mainly from the victim (pleas for his life) and have helped the system to reach a decision. The video is processed online, and the results are gathered in

Figure 2. The structured information if

Figure 2 is progressively processed by ChatGPT-nano (i.e., it processes only the current and four previous lines) and then tags the audio every two seconds (see

Figure 3). The decision is flipped from negative to positive from danger in just 6 s.

The

Supplementary Materials present a selection of videos where information cues are intermittent or entirely absent (e.g., lack of speech). Despite these missing signals, the system maintains a robust performance by integrating the remaining modalities to disambiguate the context. The link in

Appendix A-(a) provides a comprehensive assessment of all processed videos, formatted consistently with csv files, as depicted in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3.

3.1. Metrics

The proposed system was evaluated across several operational scenarios that reflect distinct real-world surveillance conditions. Each subset represents a different acoustic environment with its own challenges with respect to misses and false alarms. Based on the voting of two independent viewers, we have manually split the videos into positive and negative for human life cases, based on the audio (since the system has no access to the image). If 10% of the 2 sec chunks are flagged as positive for a life threat, the whole video is classified as positive. Sports arenas are well-guarded, therefore, we set the threshold to 15% of chunks for this scenario. The definition of metrics is in

Table 3.

Gunfight detection (17 videos).

The system consistently detected all instances of gunfire and explosions with high confidence, except in one case. Only one false negative (i.e., a miss) was recorded, in a clip where the explosion was visually present but acoustically too faint to be detected. By design, the system prioritizes precision over recall, therefore, borderline cases like this are typically rejected to minimize false alarms.

Conversely, two clips were manually classified as negative—despite containing visually apparent explosions—because they depicted controlled experiments with no risk to life. Since the objective is hazard for life detection, these safe environments are valid negatives. However, the system misclassified these instances as positive (false positives). This occurred because the acoustic signature of the repeated transients exceeded the decision threshold, overriding the lack of visual hazard indicators.

Therefore, Gunfight subset has the following: 15 positive, 13 TP, 2 FN; 2 negative, 0 TN, 2 FP.

Urban surveillance (120 videos).

This is the hardest subset to classify, and it includes cases where even human observers may disagree on whether there is danger to human life lurking. It includes complex urban scenes (metro-stations in rush, street-music events, crowdy demonstrations, clashes with police). Protest scenes were examined to see whether the model could discriminate between peaceful demonstrations and conflicts between crowds involving vandalism or violence and police forces. Note that even the “ground truth” is uncertain: human annotators often label events based on audio alone and may revise their judgments when presented with the combined audio–visual stream. Even with audio–visual evidence, raters can disagree on the severity of a clash. In this study, we operationalize life-threatening situations such as those involving gunshots, visible evidence of injury, or violent fights beyond routine crowd altercations. We consider the latter to be marginally within the limits of law.

The Urban subset has the following: 45 positive, 41 TP, 4 FN; 75 negative, 63 TN, 12 FP.

Sports facilities (36 videos).

From this corpus, the system has classified 35 videos as hazardless and 1 as positive for violence (false alarm). The single false alarm comes from an amateur hockey game and illustrates the limitations of purely acoustic classification: the microphone was positioned close to the concourse on a highly reflective surface that received the audio of repeated thuds of hockey sticks, combined with the agitated vocalizations and shouts of the players. The resulting dense sequence of impact and vocal events caused the model to classify the full recording as being indicative of a potentially hazardous situation. Although our aim is not to detect altercations and confrontations inside the sports arena, as these are hardly life-threatening, we have grouped 16 cases in a separate folder. The system successfully detected altercations, slams, and aggressive physical contact in 7 out of 16 test videos. However, it is not always possible to resolve such situations by using the audio modality alone, as the characteristic sounds of physical fights may not reach the recording microphone, though they are obvious from the visual cue.

The Sports subset has the following: 36 negative, 35 TN, 1 FP.

Indoor surveillance (8).

All eight videos have been successfully flagged as containing life-threatening situations. A practical—and, in our view, decisive—result is that armed robberies and hazardous confrontations are flagged within seconds of onset and while they are still in progress. By contrast, under current practice, public safety services often learn of incidents only well after the fact, via witnesses (if any) or victims who are able to report (if they are able), or passive surveillance cameras if their recorders have not been disabled. In our tests, two armed-robbery clips were detected rapidly: one 30 s event was persistently flagged from the sixth second onward and another 48 s event was flagged from the fifth second. In addition, a jail altercation lasting 48 s was identified as a fierce fight within 8 s and a discrete mugging case in 38 out of 1 min 24 s.

The Indoors subset has the following: 8 positive, 8 TP, 0 FN.

All counts and metrics in

Table 4 are computed from the end-to-end system described in

Section 2, applying the bin-to-video aggregation rule of

Section 3.1 to the 2 s hazard decision output by the LLM.

3.2. Examining Error Patterns

What has been made obvious after examining all errors in videos and associated captions is that vision could have disambiguated many edge cases and should be integrated whenever available. Audio and video provide complementary cues. Below, we summarize the representative failure modes observed in our evaluation.

(a) Audio-silent hazards.

Some hazardous scenes produced faint/no acoustic imprint (e.g., distant car crashes seen by dash/cabin cameras, protest footage overlaid with commentary or music). In such cases, audio-only inference is intrinsically underpowered.

(b) Normative ambiguity in crowd–police clashes.

It can be difficult to draw a context-independent boundary between loud protest and life-threatening violence. Human judgments can reflect bias or political priors, underscoring the need for explicit, pre-registered criteria. In a highly agitated protest, the model initially remained conservative but later fused flare discharges (mistaken for gunshots), a passing ambulance siren, and sustained crowd agitation into a hazardous scenario. Most residual errors arise in dense crowd soundscapes with overlapping sources. Persistent-evidence rules and “benign-context” priors (stadiums, permitted marches, fireworks windows) can mitigate drift.

(c) ASR-led misclassification via narration.

The system transcribes speech and may up-weight repeated phrases linked to danger. In one video, the commentator interleaved short clips of violent clashes (correctly flagged) with long stretches of inflammatory narration and absent visual confirmation, the model over-indexed the narration (“they are shooting people”), mischaracterizing the overall segment. This highlights the need to require ASR claims to be corroborated by visual evidence to avoid fake characterizations.

(d) Acoustic look-alikes.

On a metro line, the repeatedly slamming doors at its entrance were misclassified by the AST as gunshots. Although the system uses multi-cue integration and does not act on a single tag, the repeated impulse pattern mimicked small-arms signatures closely enough to trigger a hazard verdict. In another video, protesters are throwing stones at metallic signposts, and the audio was misclassified by the AST as gunshots. Dedicated gunshot/explosion verifiers or spectral “fingerprint” checks would reduce this error class. Finally, we analyzed two clips featuring repeated explosions conducted in a controlled environment and calmly narrated. While the system is configured to down-weight isolated gunshots and absent corroborating cues (e.g., footsteps, shouts, screams), the sustained sequence of explosions combined with missing visual evidence resulted in an error.

(e) Large audio–visual models.

We analyzed mostly the false alarm cases with audio–visual models Qwen3-VL-235B-A22B (

https://chat.qwen.ai/, accessed on 13 December 2025). Multimodal audio–visual models can substantially outperform audio-only systems at filtering false alarms by leveraging visual context. For example, we repeat that in ice hockey footage, an audio-only pipeline may interpret persistent stick thuds followed by agitated voices as a life-threatening altercation, whereas the audio–visual model infers the sports-arena context, recognizes the referee, and correctly rejects lethal danger. Conversely, in a video of a burning track where the audio signal is weak and our approach misses the event, the audio–visual model (e.g., Qwen3-VL) promptly flags a life-threatening event. That said, audio-only analysis still has value, even in the era of large audio–visual models. We observed that some Qwen3-VL variants hallucinate or repeatedly lose temporal alignment with the unfolding scene in our dataset. Qwen3 did not transcribe speech in any language we tried, but speech can be a rich cue for information in certain cases. Small guns were not always detected. A dedicated audio pipeline—built on classical signal-processing methods and independent of generative modeling—provides an additional, lightweight source of evidence that can both anchor the audio–visual model to reality and improve synchronization. In our experiments, augmenting the audio–visual prompt with the audio system’s transcript improved temporal grounding. Practical considerations also differ: state-of-the-art audio–visual models are computationally heavy and typically require specialized hardware, whereas signal-processing-based audio methods are light and embeddable even in low-resource edge devices. Real-world pipelines often use an inexpensive detector (e.g., of movement in video and SNR in audio) to detect regions of interest that are directed at state-of-the-art, but costlier, models. Our approach is more sophisticated than audio detectors based on SNR, yet it is computationally cheap compared to Qwen3 and thus has a place as a first-pass detector (e.g., in a home surveillance setting). Finally, some events occur outside the camera’s field of view—or cameras may be unavailable or impractical—making audio indispensable. When vision is available, however, integration is crucial and, in our dataset, it reduced false alarms to near zero.

Takeaway.

Despite these challenges, the overall accuracy is strong, and a qualitative review of the annotated videos confirms that audio-first AI can resolve many complex, conflicting real-world scenarios. The clearest path to further gains is principled multimodal fusion (adding vision when available and mapping it using audio–visual models to text descriptions) plus specialized verifiers for gunshots/explosions and refined context models for crowds and events. Hazardous situations are rare but life changing, and one cannot afford to miss a case, therefore, we have prioritized precision over recall. False alarms, however, are a serious problem and need to be lowered significantly because they quickly lead to mistrust and fatigue. Currently, the system can operate as a filter of reality that must direct findings to a human operator for further action.

4. Discussion

The proposed framework has the potential to enable affordable, autonomous language-based services that remain limited in their current form. These services can operate across multiple deployment tiers, ranging from personal protection to public safety.

At the personal level, the system could power voice-activated mobile applications that provide real-time protection against mugging or harassment, particularly for teenagers, women, LGBTQ+ people, elderly people, and people with disabilities that are often targeted in the streets. It could also serve as an audio-based equivalent of a “panic button” in domestic violence contexts, designed for users willing to lower their privacy standards in exchange for enhanced safety. What we are suggesting is that people who are afraid of domestic violence could voluntarily activate a service that continuously assesses domestic ‘heat’. Alerts are routed first to user-selected trusted contacts or trained advocates, with police contact only being at the user’s direction or when an imminent harm criterion is met. Recognizing the model’s limitations and the risk of false alarms, all automated detections can be reviewed or canceled by the user, and the performance metrics are openly reported. Keyword-activated audio surveillance could be deployed in small commercial environments or for in-home monitoring through consumer devices such as smart televisions or mobile phones, thereby reducing emergency response latency without reliance on visual input. A further advantage is that, unlike currently deployed CCTV systems, the audio evidence would already be transmitted off-site to secure servers—preventing intruders from destroying local storage—and audio modality is inherently less traceable.

At the public and infrastructural level, potential extensions include affect-aware public spaces that are capable of detecting distress, real-time flagging of violent or harmful content on streaming platforms, and acoustic monitoring in public transportation systems for early hazard detection. Beyond these examples, the same architecture can be adapted for industrial safety systems to detect leaks, explosions, or structural collapse sounds. In urban contexts, crowd-management applications could identify early signs of panic or aggression and direct police drones for additional evidence collection and more efficient resource prioritization.

Across all these scenarios, the novelty lies not in any single application, but in the shared foundation: a streaming, interpretable, audio-only hazard detection pipeline that operates in real time and independently of language. This unified framework enables the exploration of safety-critical settings where microphones are available but cameras are impractical—such as personal safety situations—while maintaining traceable decision processes and supporting responsible, privacy-aware deployment.

We note that audio-based systems can be vulnerable to adversarial attacks (inaudible perturbations that trigger false positives) or replay attacks (playing a recording of a gunshot) [

42,

43]. However, our multi-modal corroboration requirement (e.g., requiring ASR plus Prosody plus Event Tag) acts as a natural defense layer, as an attacker would need to spoof multiple disjoint feature extractors simultaneously to trigger a false alarm in the LLM.

Finally, lightweight audio-only detectors can work alongside more demanding audio–visual models, helping to ground their decisions and supplement their capabilities in language and speech understanding.

4.1. On the Acceptance of Surveillance in Public Spaces

Many core social institutions—laws, rights, markets, and even nation states—are intersubjective orders that persist because large numbers of people concurrently accept and enact them. Their legitimacy is not a property of nature but of a shared belief and coordination, or else “imagined orders” [

44]. In classic sociological terms, legitimacy arises when power is accepted as rightful—whether through tradition, charisma, or formal rules—so public consent is constitutive of what counts as “lawful” or “appropriate”. Because collective beliefs about societal organization evolve, the perceived acceptability of surveillance is historically contingent, rather than fixed. Cross-national panel evidence shows systematic value change over decades, while critical events (e.g., post-9/11 terrorist attacks, mass shootings of civilians, and indiscriminate shootings in educational institutions) illustrate how security shocks can recalibrate the balance people strike between liberty and monitoring. Thus, attitudes toward surveillance should be analyzed as variable outputs of shifting cultural values and legitimacy claims, not as timeless constants.

We seek to reframe the narrative around surveillance in favor of affective buildings and responsive public spaces, where automated audio–visual nodes provide continuous monitoring to detect hazardous events and trigger alerts as they occur. This entails the deployment of surveillance on large spatial scales. The objective is twofold: (a) shorten the response interval by flagging an ongoing hazardous to life event so emergency services or on-site staff can act faster and (b) enable immediate mitigation (e.g., context-appropriate announcements or alarms) that may deter offenders by notifying them that they have been detected or may guide bystanders to safety.

Privacy and safety are not static opposites. They are part of a negotiated social contract that evolves with our capabilities. In the past, buildings were passive shells. Today, we have the capacity to create Affective Buildings—structures with a moral duty to respond. When a human shouts in pain or despair, a ‘smart’ building that remains deaf is no longer neutral; it is negligent. We propose renegotiating our expectations of privacy not to intrude, but to enable an immediate, life-saving response to human suffering.

To ensure proportionality and public trust, deployments are narrowly scoped to a pre-registered set of high-harm hazards (e.g., gunshots, explosions, glass breaking with distress, multi-impact fights, traffic collisions). The algorithm runs edge-only inference with no raw audio export, and alerts consist only of short-lived event tokens. It applies strict data-retention limits and requires multi-cue corroboration and human authorization before any public intervention. Responses follow graded policies and are bounded by false alert caps and rate limiting (“harm budgets”). Small police-operated drones, when used, are launched only after human authorization and multi-cue confirmation, fly within geofenced corridors, apply privacy masking by default, and purge footage unless it is tied to an incident number. The system we present excludes biometric identification, is not designed to monitor lawful assemblies by default, and needs to operate under clear legal bases, visible signage and notice, independent oversight, and auditable, traceable logs.

4.2. Limitations

To reduce erroneous hazard alerts while preserving high accuracy, the system must separate benign, high-energy sounds from genuinely dangerous events. Fireworks and thunder are well-documented confounders for gunshots and explosions. Low-altitude aircraft flying over cities can generate low-frequency rumbling that the system can perceive as distant eruptions. Likewise, public protests and demonstrations often feature shouting and agitation without further violence, therefore, they are a legal form of collective expression in Western societies and elsewhere. This is why single-cue detectors provide insufficient evidence of harm and automated systems need to notify authorities and not act autonomously. To mitigate these ambiguities, our approach aggregates evidence over short windows and requires corroboration across independent cues (audio-event tags, lexical content, and prosody) before issuing a verdict. The large-language-model component receives a rolling history of recent audio events and is constrained to assess scenario plausibility under a fixed decision policy, reducing spurious alarms while maintaining responsiveness for life-critical cases. However, even with these guardrails, errors happen and need to be carefully measured before real deployment, and a quasi-experimental pilot on selected sites must be carried out to report the response-time deltas, incident capture rate, false alert burden on staff, and community sentiment.

4.3. Is Language the Right Substrate for Integrating Audio–Visual Evidence?

Our approach intends to map reality as perceived by audio—and subsequently, visual sensors (among others, e.g., proximity, vibrational, etc.)—to a story described in words with a query directed to the system. The system, which is exposed to a huge amount of written material during training, needs to recreate possible scenarios of reality, given sensors’ originating tokens that act as anchors to narration and scan them for possible life-threatening scenarios. At first thought, language does not appear to be the suitable means to reason for sensory information that is compressed into words. Hazard-sensing in biological systems does not require language, which, after all, in its written form, is an invention: in animals and humans, fast threat responses run through subcortical auditory–limbic pathways that can trigger defensive actions without symbolic labeling, so it is reasonable to design systems that prioritize acoustic evidence and treat language as optional context. Nonverbal acoustic codes themselves carry danger information across species and cultures—human screams exploit a “roughness” regime that rapidly recruits subcortical appraisal, and vervet monkeys produce predator-specific alarm calls—showing that category-like distinctions can arise from the acoustic structure alone. Engineering-wise, we treat language as an interpretability and control layer, not the primary sensing substrate. The core pipeline encodes audio into non-linguistic tokens—event tags, prosodic flags, and learned/quantized acoustic units—and then a streaming transformer aggregates these time-aligned tokens to score a small set of scene hypotheses (e.g., assault, crash, benign crowd). This mirrors a fast nonverbal threat appraisal in humans: danger can be inferred from the acoustic structure alone, without symbolic labeling. Language remains useful, but for different reasons: mapping token patterns to compact natural language rationales leverages broad priors for zero-shot prompting and yields auditable justifications for operators.

Operationally, we run a dual-stream representation: (i) symbolic tokens (AST/diarization/CLAP/prosody) for discrete cues and (ii) embedded acoustic states for nuance. A priority and corroboration policy governs decisions (AST > diarization > CLAP > ASR > prosody): high-risk acoustics (e.g., sustained gunfire/explosion tags) can suffice, but otherwise, we require agreement across independent channels and abstain under conflict. ASR never acts as a sole trigger, and when speech is unreliable/absent, the system defaults to non-verbal acoustic tokens and context priors. In short, language is the interface, not the sensor: transformers over embedded acoustic tokens capture meaning for decision-making, while language ensures traceability, operator trust, and low-friction integration into downstream workflows.

4.4. Related Work

The domain of automated violence detection has evolved from purely visual analysis to multimodal systems that leverage the complementary nature of audio and video. The current literature can be broadly categorized into multimodal fusion architectures, lightweight audio-specific models, and emerging foundation model approaches.

4.4.1. Multimodal and Visual-Centric Approaches

Early works primarily focused on visual cues, such as optical flow and pose estimation, to detect aggression. However, the release of large-scale multimodal datasets like X-Violence shifted the paradigm toward audio–visual (A/V) fusion [

4,

5,

8]. However, these approaches typically operate as “black boxes”—outputting a probability score without a semantic explanation for why an event was flagged. Furthermore, they often require substantial computational resources (GPUs) to process dual video–audio streams in real time, limiting their deployability on edge devices.

4.4.2. Audio-Only and Lightweight Models

Parallel research has optimized violence detection for privacy-sensitive or visually occluded environments, using only audio. Ref. [

14] and others have demonstrated that lightweight convolutional neural networks (CNNs) can detect violent signatures (e.g., screams, impacts) with high efficiency, which is suitable for resource-constrained hardware. These systems prioritize low latency and privacy but often lack the ability to distinguish between acoustically similar but semantically distinct events (e.g., distinguishing a “joyful scream” at a concert from a “distress scream” in an alley) without broader contextual reasoning.

4.4.3. The Interpretability Gap

A critical gap remains in the interpretability of the decisions of various classification approaches. Standard deep classifiers do not provide a rationale for their alerts, which is a significant barrier to trust in public safety applications. While recent foundation models like AST [

16,

18] and CLAP [

36] offer powerful tokenization of audio concepts, they have rarely been integrated into a reasoning framework that can output human-readable justifications in real time.

4.4.4. Our Approach

Instead of feeding raw audio embeddings directly into a massive LMM (which would be slow), the system uses specialized, lightweight signal processing (AST, ASR, CLAP, Diarization) to convert the sensory world into a compact textual narrative (e.g., “00:02: Gunshot detected. 00:04: Screaming detected, agony, [Male], [Speaker turns]. ASR: ‘Money in the bag, please don’t shoot’.”).

Efficiency: Inference on this short text sequence by a small-LLM (like ChatGPT5-nano or Llama-3.2-1B) is exponentially faster than processing raw modalities. It allows the complex “reasoning” (e.g., correlating the gunshot with the scream) to happen at the speed of text processing. Signal processing techniques are fast and, therefore, we achieve the interpretability of an LLM with the latency profile of signal processors.

Interpretability: The generated text log functions as an auditable “Chain of Thought,” allowing operators to verify exactly which inputs triggered a “Hazard” decision. This transparency effectively addresses the “black box” limitations that are common in end-to-end deep learning models. Furthermore, by abstracting the raw sensor data into text, we decouple the reasoning engine from the input modality. This design ensures extensibility, allowing for new modalities to be integrated without retraining the core system.

Table 5 presents a comparative analysis of our approach against state-of-the-art methods on the XD-Violence dataset.

To position our approach within the broader research landscape, we first trace the trajectory of automated hazard detection from hand-crafted features to sophisticated deep learning paradigms. We categorize the contemporary literature into three primary streams: weakly supervised video anomaly detection (WS-VAD) [

45,

46,

47,

48], large multimodal models (LMMs), and audio-centric surveillance [

49]. We then critically analyze the trade-offs regarding latency, privacy, and interpretability that are inherent in these approaches to contextualize our contribution, as summarized in

Table 6.