Abstract

The integration of neural interfaces with assistive robotics has transformed the field of prosthetics, rehabilitation, and brain–computer interfaces (BCIs). From brain-controlled wheelchairs to Artificial Intelligence (AI)-synchronized robotic arms, the innovations offer autonomy and improved quality of life for people with mobility disorders. This article discusses recent trends in brain–computer interfaces and their application in robotic assistive devices, such as wheelchair-mounted arms, drone control systems, and robotic limbs for activities of daily living (ADLs). It also discusses the incorporation of AI systems, including ChatGPT-4, into BCIs, with an emphasis on new innovations in shared autonomy, cognitive assistance, and ethical considerations.

1. Introduction

Neural interfaces bridge the gap between the brain and machines, enabling users to control external devices using neural signals. While once confined to laboratory settings, such interfaces are now making their way into widespread practical applications in robotics and prosthetics. The roots of neural interfaces trace back to the 1960s, with early experiments demonstrating that animals could control external devices using implanted electrodes. In the 1990s and early 2000s, large breakthroughs in electroencephalogram (EEG) technology and machine learning laid the foundation for non-invasive brain–computer interfaces (BCIs) [1]. The first human trials of cortical implants for controlling cursors or robotic arms began around this time, with one pivotal moment in public awareness coming with Stephen Hawking’s use of a neural interface to type and communicate while living with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS), highlighting the transformative potential of such systems [2]. Since then, advances in neural decoding, signal processing, and AI integration have rapidly accelerated, shifting BCIs from experimental devices to viable assistive technologies [1]. This paper discusses recent progress in BCI-driven assistive robotics in seven important areas: (a) wheelchair-mounted robotic arms, (b) robotic arms for activities of daily living (ADL), (c) BCI-controlled drone interfaces, (d) Robotic arms and high degree of freedom (DoF) prosthetics, (e) ChatGPT and large language models (LLMs) in neural interfaces, (f) Shared and hybrid control, (g) BCI-based communication and typing systems, and (h) BCI in neurorehabilitation.

1.1. Related Works

Several reviews have explored neural interfaces for assistive robotics, often focusing on specific modalities or applications. For example, Kawala-Sterniuk et al. [1] provided a historical overview of BCIs, while other surveys emphasized non-invasive EEG-based systems or shared-control frameworks. While these works are informative, they tend to be narrow in scope, either by neural signal type or application domain. In contrast, this manuscript offers a broader, application-driven perspective, comparing both invasive and non-invasive approaches across wheelchairs, robotic arms, drones, and hybrid systems. Additionally, it highlights recent integrations with AI and large language models.

1.2. Significant Contributions

This paper makes several key contributions to the field of neural interfaces for robotics and prosthetics. First, it provides a wide review on state-of-the-art technology, spanning both invasive and non-invasive approaches, and highlights how these methods enable robotic control across multiple domains. Second, it critically examines practical applications while identifying technical strengths and persistent limitations. Third, it presents a comparative perspective across different neural interface modalities, drawing attention to their usability, reliability, and scalability. Finally, the paper discusses novel ways that Artificial Intelligence (AI), have been integrated into the use of brain control interfaces, including the recent development of GPT models, instead of the much more commonly discussed and older Large Language Models.

2. Literature Search Methods

To ensure a comprehensive and up-to-date overview, a systematic literature search was conducted across the databases of PubMed, IEEE Xplore and Google Scholar for sources. The search was started from the initial research question surrounding the most novel and widespread uses of BCI and EEG in robotics and prosthetics. The search, carried out between May and August 2025, used combinations of the following keywords: “brain–computer interface” OR “BCI” OR “neural interface” AND “assistive robotics” OR “prosthetic control” OR “wheelchair” OR “communication interface” AND “artificial intelligence” OR “machine learning” OR “large language model” OR “ChatGPT” OR “hybrid control” OR “BCI neurorehabilitation” OR “shared autonomy.” The inclusion of both classical and emerging terminology ensured coverage of foundational research as well as the latest AI-driven BCI developments. Search filters were applied to include peer-reviewed journal articles, conference papers, and review studies, written in English. Additional studies were identified through backward citation tracking of key papers to capture influential earlier work and relevant cross-disciplinary contributions. This systematic retrieval process provided a balanced dataset that spanned early signal-processing approaches to the most recent developments in AI integration.

3. Neural Interface Applications

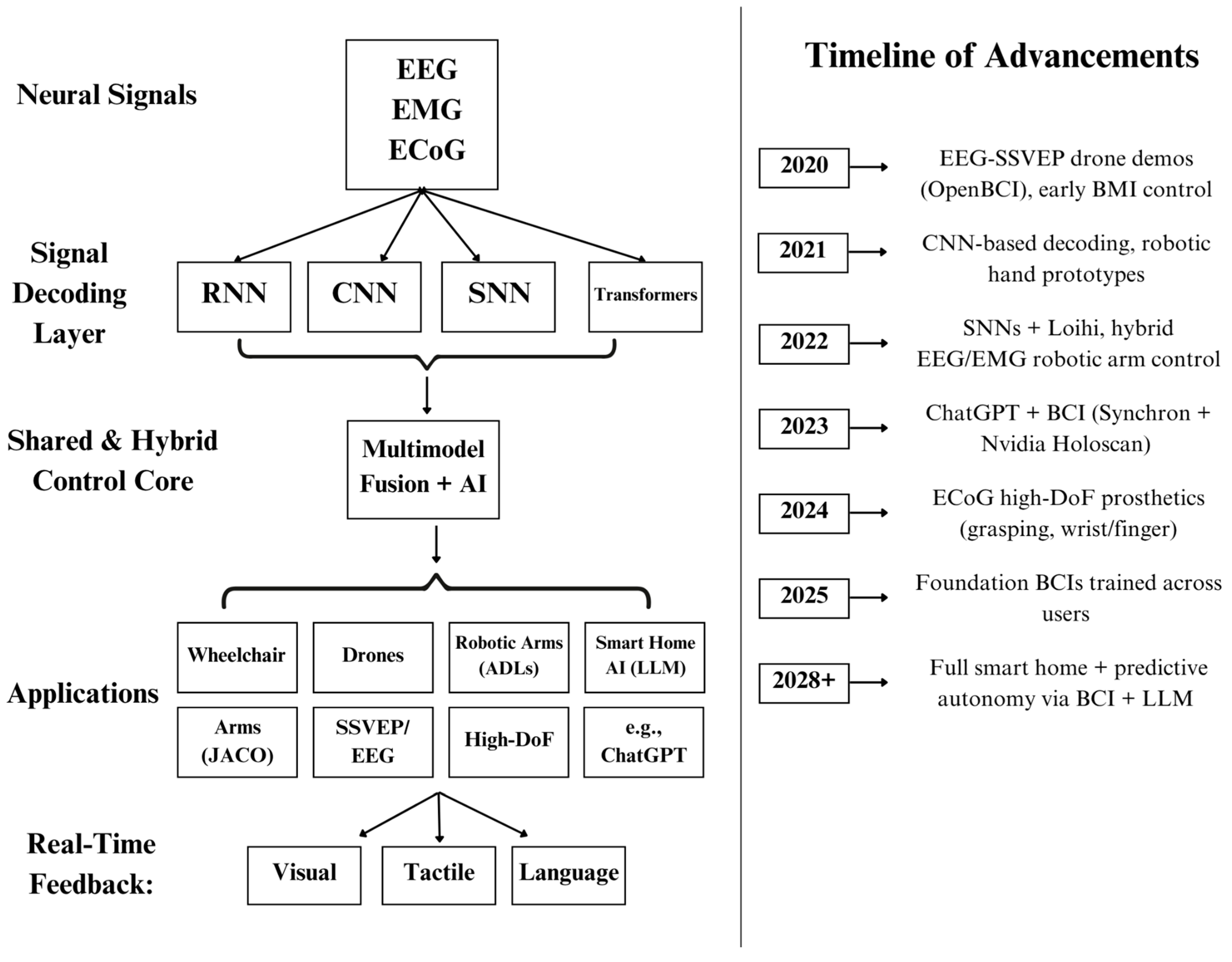

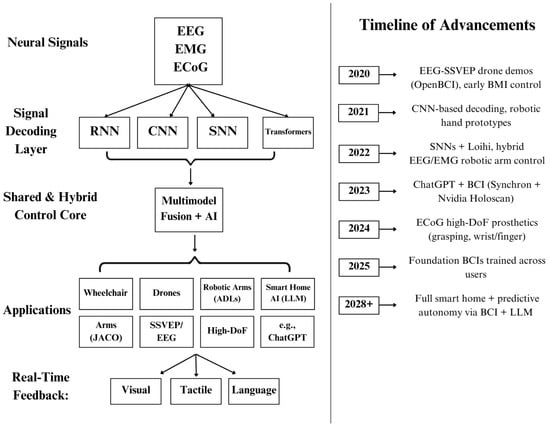

BCI systems comprise many segments which include everything from data collection to output. Figure 1 outlines the full pipeline from neural signal acquisition through electroencephalograms (EEG), electromyography (EMG), and electrocorticography (ECOG) to real-time control of assistive technologies. Signals are decoded through artificial intelligence (AI) models such as recurrent neural networks (RNN), convolutional neural networks (CNN), spiking neural networks (SNN), and transformers, then integrated into a shared control core that drives applications like robotic arms, wheelchairs, drones, and smart home systems. Figure 1 shows a descriptive pipeline of the BCI in assistive technologies. The timeline on the right highlights key advances from 2020 through future projections, including EEG controlled hardware, foundation models, and large language model integration. The following sections expand on each part of this pipeline, beginning with wheelchair-mounted robotic arms and moving through decoding strategies, feedback mechanisms, and AI-assisted communication tools.

Figure 1.

Timeline and description of the brain signal to assistive technology pipeline. (EEG—Electroencephalogram, ECOG—Electrocorticography, EMG—Electromyography, SNN—Spiking Neural Networks, RNN—Recurrent Neural Network, CNN—Convolutional Neural Network, DoF—Degrees of Freedom, SSVEP—Steady State Visual Evoked Potential, LLM—Large Language Model) [1].

3.1. Wheelchair-Mounted Robotic Arms

One of the newer applications of BCIs, as seen in Figure 1, is the control of robotic arms in mobility aids, i.e., wheelchairs [3]. These systems allow individuals with severe upper limb disabilities to perform daily tasks such as eating, grooming, or reaching for objects [4].

A recent innovation is the development of neuromorphic adaptive control systems based on Intel’s Loihi chip [5]. Scientists have employed spiking neural networks (SNNs) that enable wheelchair-mounted arms to adapt their movements in real time. SNN-based systems offer greater flexibility and lower latency than traditional PID control in dynamic environments [6]. These systems are energy efficient as well as being capable of regulating grip force and trajectory based on user intent and environmental conditions.

The CARRT (Center for Assistive, Rehabilitation & Robotics Technologies) Labs at the University of South Florida have developed advanced wheelchair-mounted robotic systems aimed at improving the independence of individuals with severe motor disabilities, as seen in Figure 2 [7]. Their work brings together mobility and manipulation, in a 9-DoF Image-Based Servoing algorithm, combined with having two separate trajectories for various ADL tasks, such as opening a door inward and going through it while maintaining the pose of the arm. This multifunctional system has greater assistive potential and better mimicry of human motion [8,9].

Figure 2.

CARRT Lab robotic wheelchair with 7-DoF arm in use to grab a glass [7,8,9].

Another example of assistive robotic arms is the iARM, developed by Exact Dynamics. This six-degree-of-freedom robotic manipulator is designed to be mounted on powered wheelchairs, providing individuals with severe upper limb impairments with the ability to perform essential tasks such as feeding, grooming, and object manipulation. The iARM shows how embedded sensing and actuation technologies can be integrated into daily assistive use and can become widespread in a short amount of time [10].

Although wheelchair-mounted robotic arms demonstrate high assistive potential and promising integration of neuromorphic and servoing algorithms, their deployment is constrained by cost, mechanical complexity, and training requirements for end-users. Compared to stand-alone prosthetic arms, they excel in mobility-linked independence but still face challenges in adapting to diverse environments and ensuring reliable long-term operation.

3.2. Robotic Arms for Activities of Daily Living (ADL)

Beyond wheelchairs, robotic arms are being developed for use in home and rehabilitation settings to assist with everyday tasks, such as cooking, self-care, and communication. These arms must be safe, accurate, and cost effective to see widespread use [11]. Their advantage lies in reducing user fatigue and improving task completion rates; however, autonomy introduces risks of errors or unintended actions. Robotic arms for ADLs come in many forms, whether in exoskeleton style or an external manipulator, the relative pros and cons of each are currently under testing, with studies showing that exoskeleton style arms are more preferred [12].

When compared to wheelchair-mounted systems, ADL-focused arms emphasize household integration but face challenges in cost reduction and safe physical interaction in unstructured environments.

To address the limitations of direct neural control, researchers have implemented shared-control systems where the user provides high-level commands and the robotic system completes the task autonomously, with the ability for the user to interrupt any task at any time during the task [13]. For example, EEG signals may indicate the desire to track a point, as seen in Figure 3, while computer vision and AI perform the grasping action.

Figure 3.

A robotic arm created by researchers at CMU that can track and follow a dot on a computer [14].

A study has shown that combining EEG-based intention decoding with CNN-based object detection improved task completion time and accuracy, while reducing user fatigue [15]. Additionally, SNNs have demonstrated superior performance over traditional machine learning and decoding methods in interpreting motor intent from EMG signals [5]. Accuracy in the most recent models has jumped up to nearly 80% across a wide range of two finger movements, and 60% in three finger movements, a large increase in precision compared to older technologies [16].

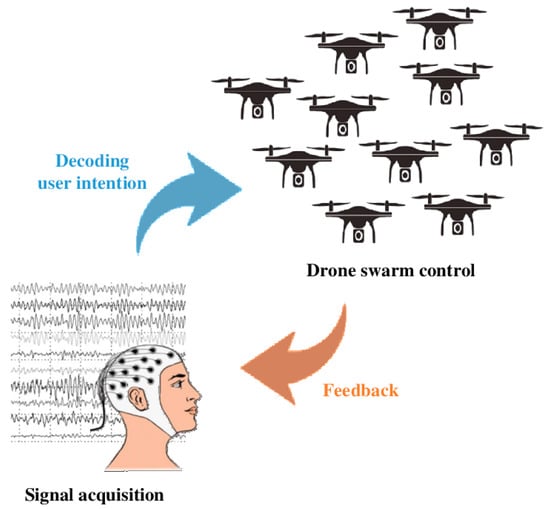

3.3. BCI-Controlled Drone Interfaces

Mind-controlled drones are one of the more novel and futuristic applications of BCI technology. In a 2025 Nature Medicine article, a paralyzed individual navigated a drone through a complex obstacle course using a high-density electrode array [17]. The interface used deep learning decoders to transform neural patterns into flight commands.

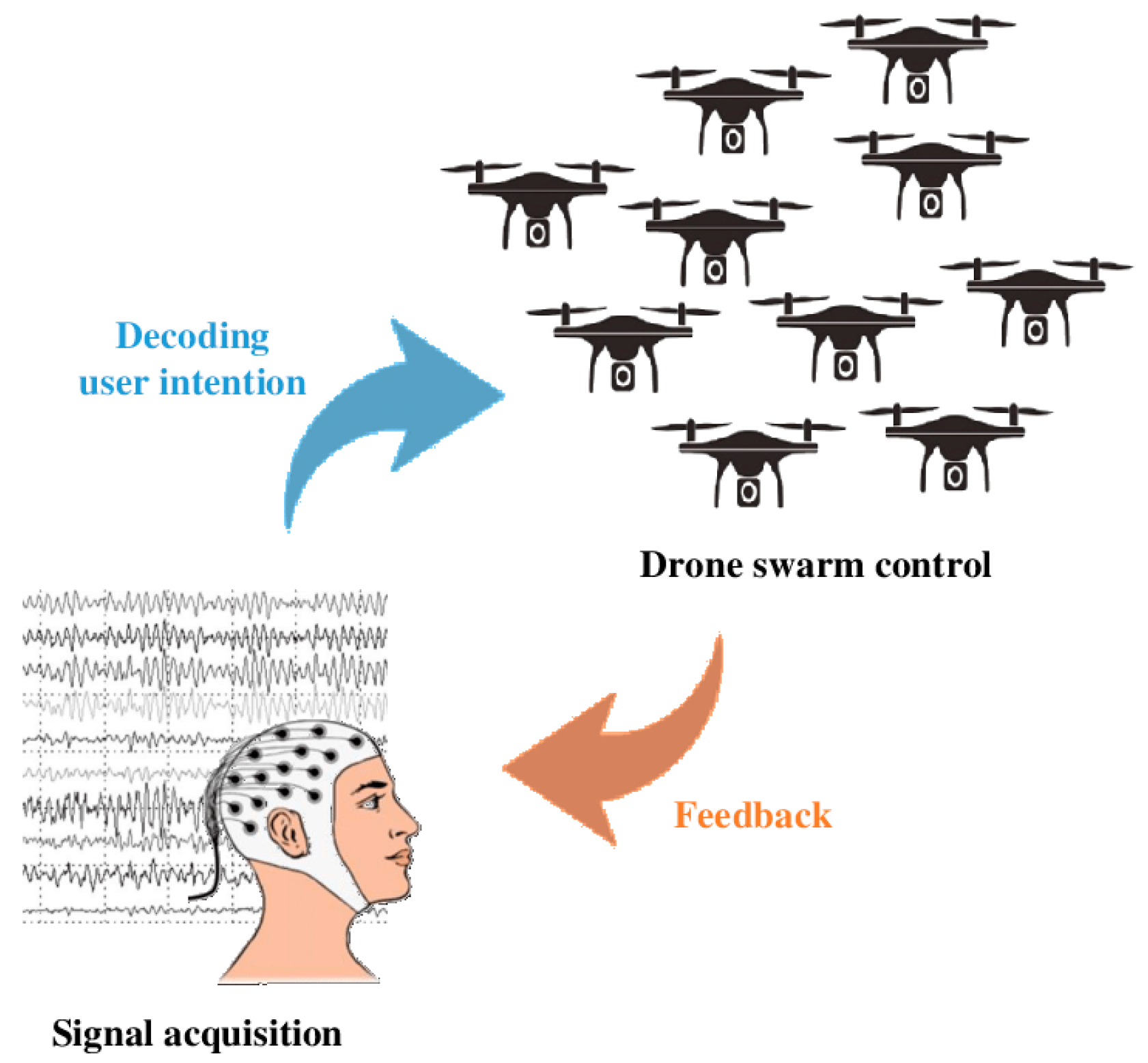

Drone interfaces showcase the reach of BCIs but remain limited in practical application. Invasive approaches provide superior control and precision but are impractical for everyday use, while non-invasive methods offer accessibility at the cost of noisy signals and lower accuracy. In comparison with robotic arms, drones demonstrate the flexibility of neural control beyond assistive care, but their main contribution today is as a research platform or commercial item rather than a clinically deployable tool. Non-invasive systems, such as EEG headsets combined with eye trackers, have demonstrated hands-free quadcopter control using steady-state visually evoked potentials (SSVEPs), as seen in Figure 4 [18,19]. Despite their lower resolution and sensitivity to noise, these systems are appealing for at-home or recreational use.

Figure 4.

Example of Signal-Control pipeline in drone interface with EEG (Reprinted with permission from Ref. [20] Copyright 2020 arXiv).

Importantly, both invasive and non-invasive systems have achieved closed-loop control, providing real-time visual or tactile feedback to the user, with these types of feedback loops significantly enhance precision, responsiveness, and safety [21]. Systems have also been linked to augmented reality, allowing for better control and better interfaces than ever before [22].

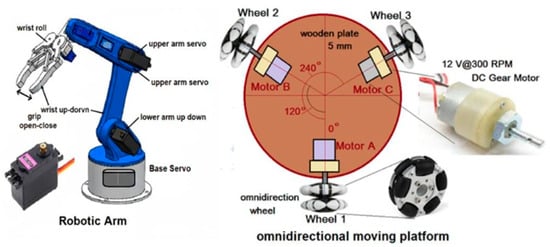

3.4. Robotic Arms and High-DoF Prosthetic Control

Controlling robotic limbs with high degrees of freedom (DoF) is an ongoing challenge. Recent research using electrocorticography (EcoG) has enabled users to manipulate robotic arms with six or more DoFs, including wrist and finger articulation [23].

These systems employ RNNs and other machine learning architectures trained on neural signals to decode fine motor intentions in real time. High-DoF systems represent a leap toward natural motion, with invasive methods showing the greatest potential for restoring fine motor function. Yet, the cost, training requirements, and long-term implant stability remain major barriers.

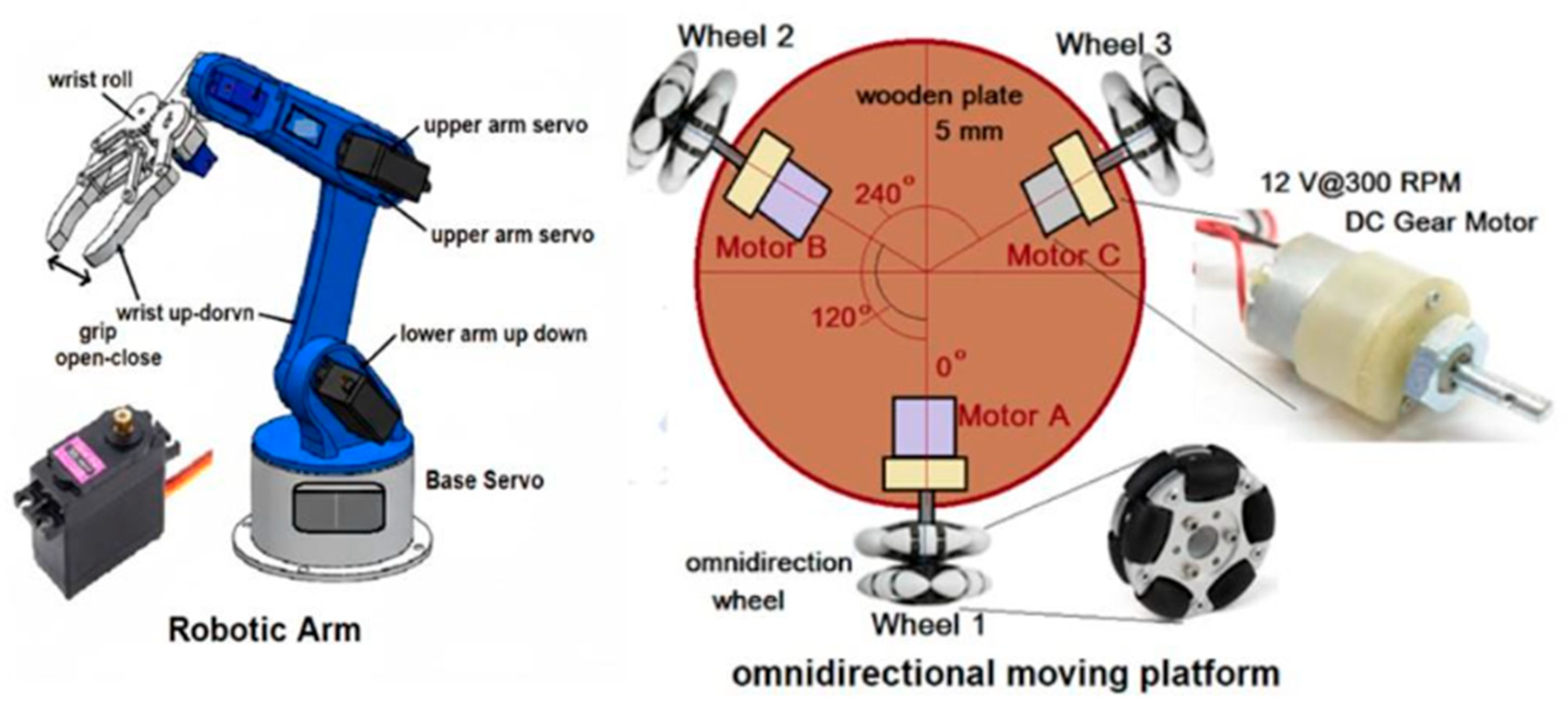

In one study, a participant with spinal cord injuries used high-resolution cortical implants to once again be capable of tasks like opening bottles and pouring liquids [24]. In another, tactile feedback was established during ADL’s through a bionic arm, allowing feedback from their actions and more precise use [24]. At the opposite end, Do It Yourself (DIY) systems using consumer EEG gear and Arduino boards have demonstrated basic, low-cost robotic control options suitable for education and prototyping, as seen in Figure 5 [25,26]. While DIY and low-cost approaches increase accessibility, they compromise largely on precision, often making them unsuitable for true unassisted daily life. Compared to wheelchair-mounted or ADL arms, these systems highlight the tension between performance and scalability, suggesting hybrid approaches may be the most viable path forward.

Figure 5.

Example of a high DoF robotic arm powered by Arduino technology [26].

The current bottleneck is balancing precision with price and usability. Combining EMG, eye tracking, and cognitive control in hybrid interfaces appears to offer the best path forward for scalable, intuitive, and usable high-DoF systems [27].

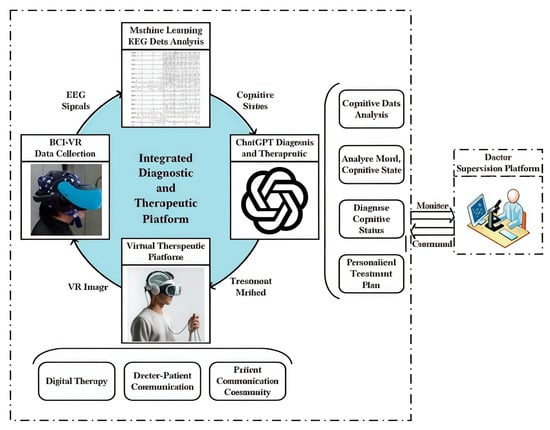

3.5. ChatGPT and LLMs in Neural Interfaces

The integration of AI language models, such as ChatGPT, into BCI systems is a groundbreaking advance in assistive technology. Synchron [28], a U.S.-based neurotech firm, has developed a mesh-like electrode array that interfaces with NVIDIA’s Holoscan platform and ChatGPT, allowing patients to interact with smart home devices and compose messages using only thought [29]. In such systems, the BCI detects the user’s intent, and ChatGPT or another AI model facilitates natural language interaction. For example, users can issue commands like “turn off the lights” or ask questions, and the AI interprets and executes these inputs [30].

AI-assisted BCIs also improve user experiences by offering predictive typing, error correction, and context-awareness. This reduces the cognitive load on the user and speeds up communication [31]. However, the fusion of thought and machine learning raises complex ethical concerns regarding authorship, privacy, and agency, with some emerging applications of BCI technology—including commercial ventures that seek to meld human intelligence with AI—presenting new and unique ethical concerns [32].

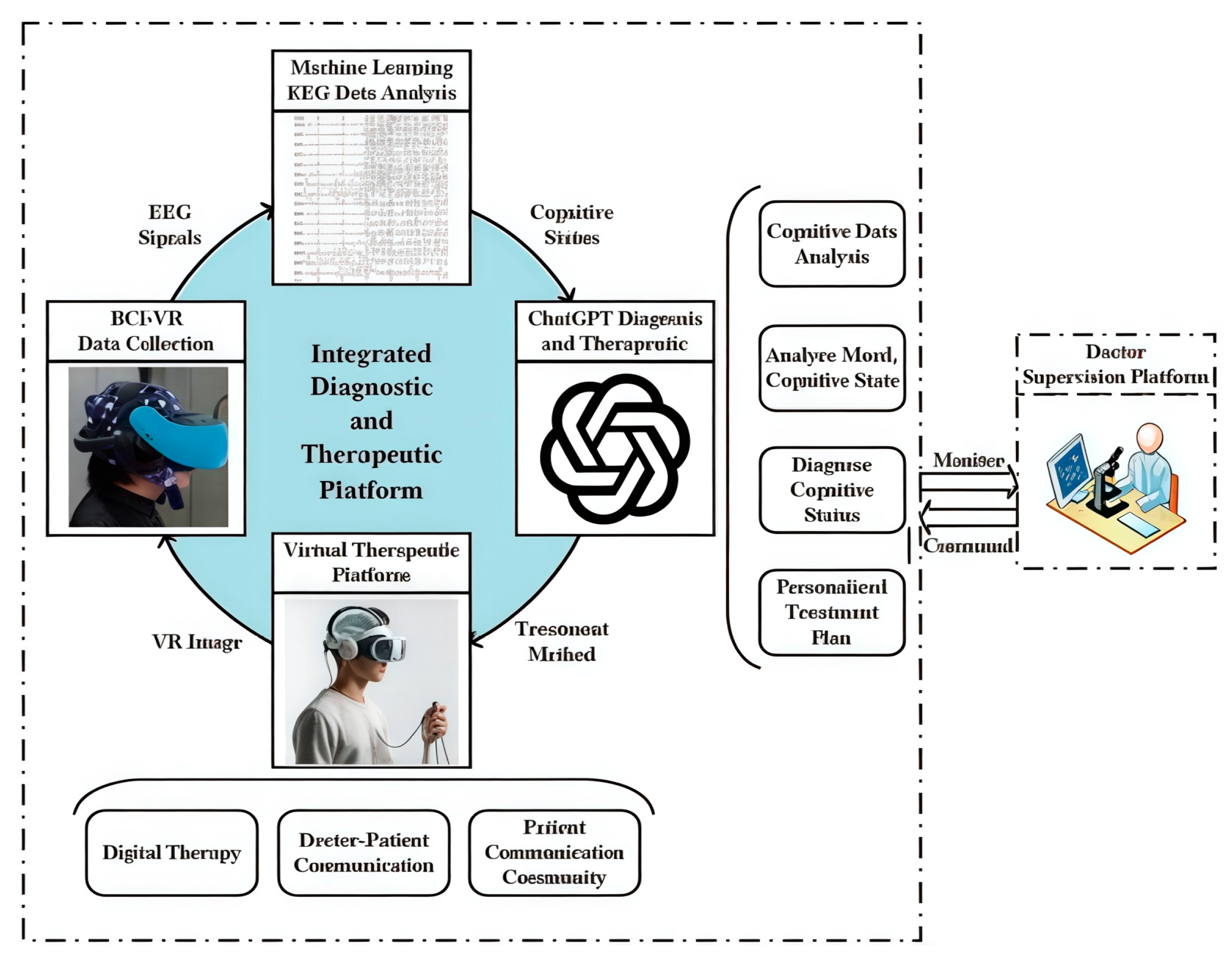

A ChatGPT-based model that links non-invasive EEG signals with upper-limb motion data from marker-based motion capture has been developed by [33]. The system achieved over 80% classification accuracy using a 16-channel EEG headset and demonstrated the potential of generative AI to enhance intent decoding for assistive device control. This approach supports more natural, high-level interaction between users and robotic systems. This increase in accuracy can lead to more advanced applications for deciphering EEG through easily accessible chatbots, leading to possible advancements such as EEG ChatGPT based therapy as shown in Figure 6.

Integrating LLMs into BCI systems greatly enhances communication and task efficiency by adding contextual understanding, predictive typing, and natural interaction. The key strength is reducing cognitive workload, but this benefit is counterbalanced by ethical and privacy concerns around data ownership, agency, and dependency on proprietary AI models [34]. Compared with traditional spellers, LLM-assisted systems improve speed and usability, yet the technology is still in early phases of deployment. However, the rush to commercialize BCIs risks prioritizing market interests over patient welfare [35].

Figure 6.

A proposed AI-enhanced integrated platform combining EEG-VR data and ChatGPT for personalized cognitive diagnosis and therapy (Reprinted with permission from Ref. [36]. Copyright 2024 Frontiers).

Figure 6.

A proposed AI-enhanced integrated platform combining EEG-VR data and ChatGPT for personalized cognitive diagnosis and therapy (Reprinted with permission from Ref. [36]. Copyright 2024 Frontiers).

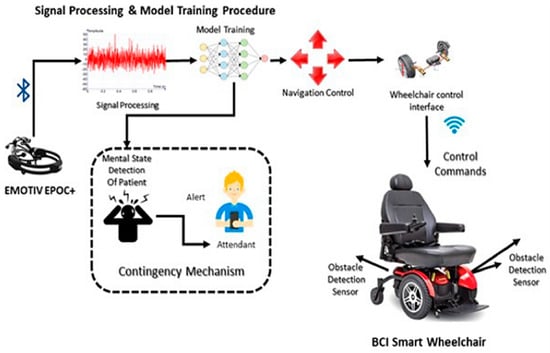

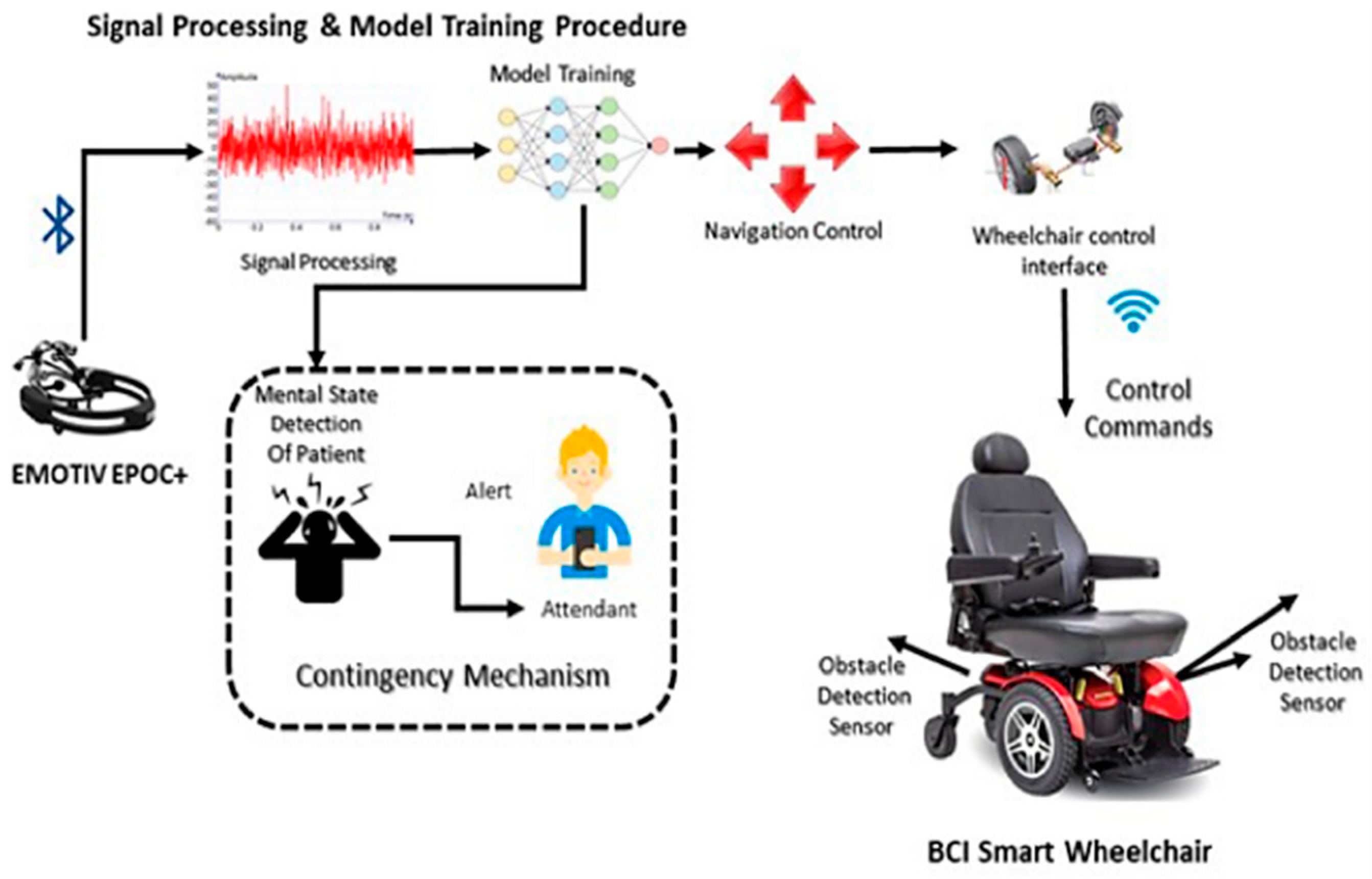

3.6. Shared and Hybrid Control

Shared and hybrid control models have become essential due to the limitations of single-modality BCIs. In a shared-control framework, the user provides directional cues while the system uses autonomous algorithms to complete tasks—such as using visual or haptic sensors to align a robotic arm with a target object [37]. Shared and hybrid systems clearly outperform single-modality BCIs in robustness and user satisfaction, making them one of the most promising directions for practical adoption. Their strength is adaptability, as multiple biosignals compensate for weaknesses of individual channels. Hybrid interfaces combine multiple bio signals—EEG for cognitive commands, EMG for muscle activation, and eye-tracking for attention—and fuse them using neural networks or reinforcement learning to interpret user intent with greater reliability, as seen in Figure 7 [38]. Studies have shown that these multimodal systems not only improve task accuracy but also enhance the user’s sense of agency and satisfaction [39]. For individuals with minimal mobility, this can translate into independence in daily life. However, integration complexity, calibration time, and cost remain significant barriers. In comparison with purely EEG- or EMG-based systems, hybrid models provide superior reliability but demand more sophisticated hardware and computational resources. Recent systems that can take advantage of both EEG and electrooculography (EOG) inputs have achieved accuracies of up to 96.61% for activities of daily living [40].

Figure 7.

Input output cycle of an EEG-based BCI system enabling wireless control of a powered wheelchair via visual stimuli [41].

Figure 7.

Input output cycle of an EEG-based BCI system enabling wireless control of a powered wheelchair via visual stimuli [41].

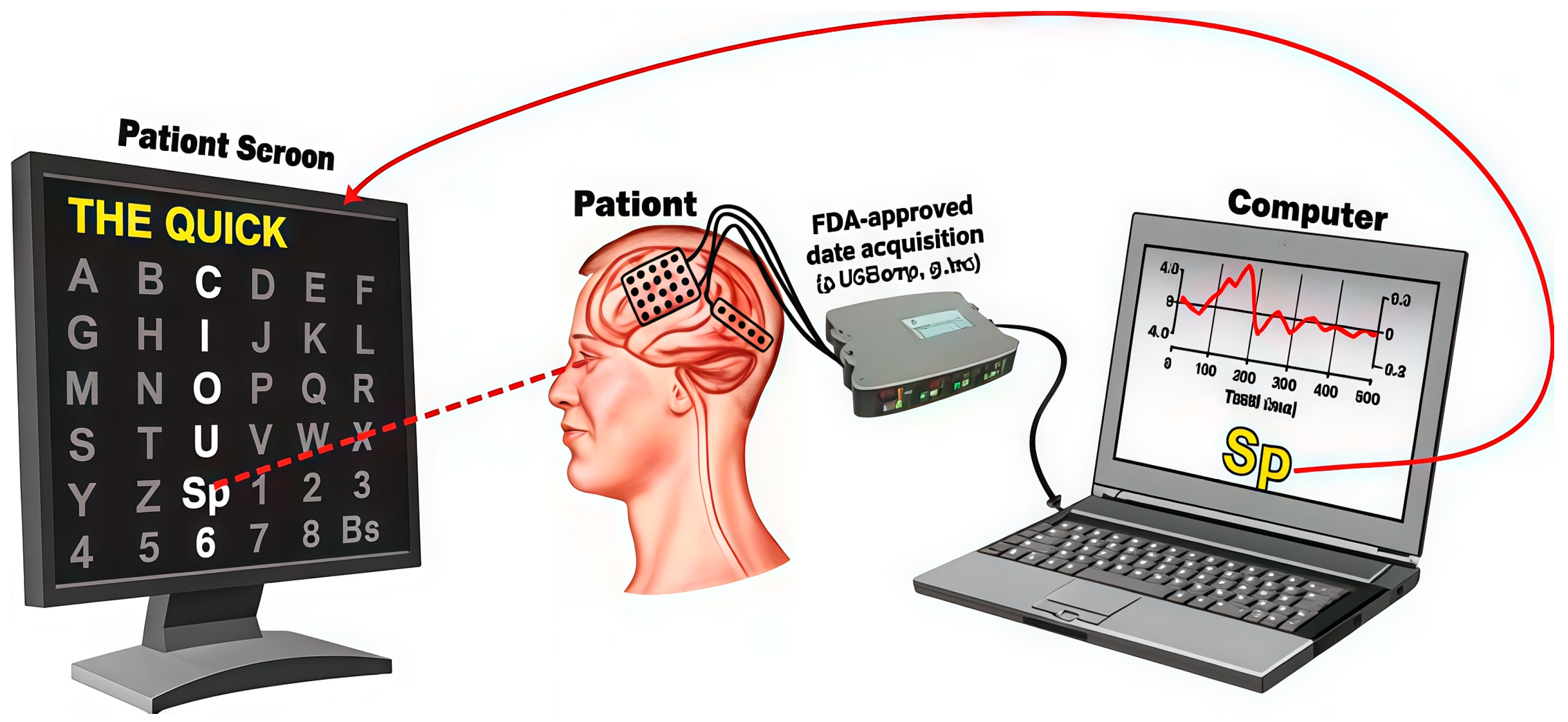

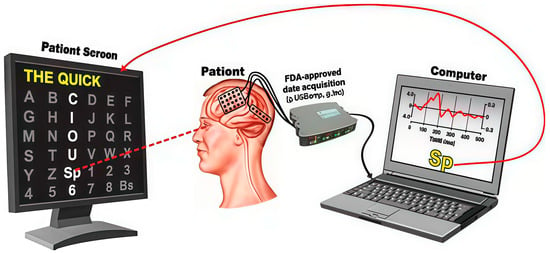

3.7. BCI Based Communication and Typing Systems

Brain–computer interface (BCI) systems for communication and typing have been a cornerstone of assistive neurotechnology for decades. These systems allow individuals with severe motor impairments, including those with ALS or brainstem injuries, to express themselves by selecting letters or controlling digital interfaces using only their brain signals [42]. One notable example is Stephen Hawking, who used a cheek-operated switch and later collaborated on more advanced systems integrating predictive software to facilitate communication as his physical capabilities declined. His case helped popularize BCI communication as a realistic solution for patients facing total paralysis [2].

Modern BCI spellers typically rely on paradigms such steady-state visually evoked potentials (SSVEPs), P300s (method seen in Figure 8) or even intracortical recordings for higher accuracy, though issues persist [43]. Advances in AI, particularly the integration of language models like transformers, have enabled the decoding of neural signals into coherent text at increasingly fast and accurate rates. In one study, users have achieved communication speeds exceeding 90 characters per minute, marking a significant leap in usability and practicality [44]. Their advantage is enabling independence for patients, but limitations persist in terms of accuracy, prolonged training sessions, and dependence on visual stimuli. Compared to control applications like arms and drones, communication systems are more clinically mature, yet still face challenges in scalability, portability, and equitable access.

Figure 8.

P300 Based BCI spelling system using EEG signals to select letters on a screen for communication spelling system, from screen to computer (Reprinted with permission from Ref. [45]. Copyright 2011 Frontiers).

3.8. Neurorehabilitation

Modern neurorehabilitation systems work to restore lost motor functions following stroke, spinal cord injury, or neurodegenerative disease [46]. These platforms combine neural activity monitoring—often through EEG or functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) with robotic exoskeletons or haptic feedback mechanisms to promote neuroplasticity and reestablish motor control through repetitive, task-specific training. Hybrid BCIs that fuse multiple physiological modalities, such as EEG and EMG, have shown significant improvements in accuracy and adaptability for post-stroke motor recovery compared to single-signal approaches [47]. Recent studies also emphasized the role of models, which personalize rehabilitation protocols based on patient performance and neural biomarkers, enhancing the rate and extent of functional recovery [48]. Neurorehabilitation represents a key frontier where neuroscience, robotics, and artificial intelligence converge to promote independence and quality of life in individuals with motor impairments, including in strokes and other diseases [49]. In another study, BCI was used as a validation index for transcranial stimulation, increasing connectivity and accuracy when paired together to help in lower limb motor imagery [50].

3.9. Current Research Gaps

Brain–computer interfaces (BCIs) continue to face significant limitations that hinder their practical application, with each type of technology facing different challenges and having different new lines of inquiry, as seen in Table 1. Studies such as Zhang et al. highlight that many studies rely on small sample sizes, exhibit poor generalizability, and suffer from inconsistent signal quality, which reduces reproducibility while case studies such as Stephen Hawking’s assistive technologies (University of Washington) demonstrate the potential of BCIs for communication and rehabilitation but also show their dependence on highly specialized, individualized setups [2,42]. Laboratory studies on neural decoding and neuroprosthetic control (2017; Collinger et al., 2013) achieve impressive accuracy, yet performance often declines in real-world conditions due to variability in neural signals, environmental noise, and task complexity [23]. Hardware complexity and system integration also remain major barriers [23].

Table 1.

Advances in each application of BCI and Assistive Technology discussed in this paper, their respective drawbacks, as well as potential research gaps.

Hybrid interfaces combining EEG, EMG, and eye-tracking (Ehrlich et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2024) improve intent detection and user satisfaction but require extensive calibration, costly components, and sophisticated integration [6,42]. Non-invasive BCIs, while safer and more practical, still struggle to match the speed, precision, and robustness of invasive systems (Willsey et al., 2025; Doud et al., 2011) [17,19]. AI-enhanced BCIs for natural language processing, drone control, or hybrid decoding (Jin et al., 2025; Carìa, 2025; Mota et al., 2025) remain largely experimental and lack long-term validation, leaving real-world usability, cognitive load, and safety insufficiently studied [30,33,34]. Additionally, inconsistencies in experimental protocols and performance metrics hinder comparability and slow progress toward standardized benchmarks (Abiri et al., 2019; Styler et al., 2025) [37,51].

Finally, as BCIs expand beyond the lab, ethical and legal challenges become increasingly urgent. Autonomy, neuro-rights, privacy, and informed consent remain underexplored despite the potential for misuse of neural data (Coin et al., 2020; Ienca & Andorno, 2017) [32,52]. Addressing these limitations requires scalable, user-independent decoding methods, standardized benchmarking datasets, and ethical deployment frameworks to ensure BCIs are reliable, accessible, and safe in real-world settings [53].

4. Future Directions

The field of neural interfaces for robotics and prosthetics is rapidly advancing, propelled by innovations in adaptive hardware, artificial intelligence, and multimodal signal processing. Existing studies have demonstrated remarkable progress ranging from wheelchair-mounted robotic arms like the iARM to cortical implant–driven prosthetic hands and low-cost EEG Arduino systems. However, most current research remains limited by small sample sizes, poor generalizability, long calibration times, and inconsistent signal quality across users. These shortcomings point to the urgent need for scalable, user-independent neural decoding methods and standardized benchmarking datasets to ensure reproducibility and comparability across studies.

AI integration, particularly through large language models, has enabled natural language processing within BCI systems for writing, smart home control, and cognitive therapy. Yet, these applications remain largely experimental and lack long-term validation through research and remain validated only in short-term experiments at best. Future research should focus on longitudinal studies assessing real-world usability, cognitive load, and safety, as well as on adaptive AI architectures that learn and update with the user’s neural patterns to improve personalization and reduce setup time.

Hybrid systems combining EEG, EMG, and eye-tracking have shown promise in improving intent detection and user satisfaction. Still, their hardware complexity and integration costs limit widespread adoption. Additionally, researchers need to explore the options between non-invasive and invasive methods in terms of their respective costs and accuracies, and also to make noninvasive versions of these systems at the same level as existing invasive solutions. Researchers should aim to develop low-cost, energy-efficient, and compact multimodal platforms that balance accuracy with accessibility. Finally, as BCI applications expand, there is a critical need to establish ethical and legal frameworks addressing issues of autonomy, data privacy, and neuro-rights.

5. Conclusions

The field of neural interfaces for robotics and prosthetics is rapidly advancing, driven by innovations in adaptive hardware, AI, and multimodal signal integration. Technologies like wheelchair-mounted arms, BCI-controlled drones, and AI-enhanced communication tools highlight the potential of this field to enhance both physical and cognitive function.

While wheelchair-mounted robotic arms, such as the iARM, show how the recent advancements in BCI and robotics can have huge impacts on people’s physical rehabilitation, mind-controlled drones and high-DoF arms—ranging from cortical implant-driven robotic hands to DIY EEG-Arduino systems—show the ability of robotics to interface with both fun and commercial projects. The integration of AI, particularly ChatGPT, into BCI systems has unlocked natural language processing capabilities for composing messages, controlling smart home devices, and even enabling cognitive therapy through EEG-chatbot interaction platforms. Inspired by GPT models, researchers are developing general-purpose neural decoders trained across individuals to reduce calibration time [52], which has a significant impact on prosthetic simplicity and usability. Furthermore, hybrid interfaces combining EEG, EMG, and eye-tracking have shown superior intent detection and user satisfaction in shared control model, leading to high possibility for new eye tracking and brain scanning tech becoming widespread to increase convenience. However, there is a growing need for ethical frameworks on human-BCI rights, to address autonomy, safety, and data protection in mind–machine collaboration, because utilization of one’s brainwaves is a relatively new ethical question [53].

The future of BCI lies in seamless, intuitive integration between the brain and intelligent systems, enabling enhanced mobility, communication, and cognition. As hardware becomes more adaptive and AI continues to evolve, BCIs will move even more from labs to everyday life. Multimodal systems and general-purpose decoders promise unprecedented accessibility, and aid to those in need. Progress points toward a future where brain–computer interfaces unlock human potential in entirely new ways, transforming how we move, communicate, and connect with the world.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.A. and S.S.; resources R.A.; writing—original draft preparation, S.S.; writing—review and editing, R.A.; visualization, S.S.; supervision, R.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study..

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript: ALS—Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis EEG—Electroencephalogram, ECOG—Electrocorticography, EMG—Electromyography, BCI—Brain–Computer Interface, SNN—Spiking Neural networks, RNN—Recurrent Neural Network, CNN—Convolutional Neural Network, DoF—Degrees of Freedom, SSVEP—Steady State Visual Evoked Potential, LLM—Large Language Model.

References

- Kawala-Sterniuk, A.; Browarska, N.; Al-Bakri, A.; Pelc, M.; Zygarlicki, J.; Sidikova, M.; Martinek, R.; Gorzelanczyk, E.J. Summary of over Fifty Years with Brain-Computer Interfaces-A Review. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- University of Washington. Dr. Stephen Hawking: A Case Study on Using Technology to Communicate with the World. Access Computing. Available online: https://www.washington.edu/accesscomputing/dr-stephen-hawking-case-study-using-technology-communicate-world (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Lebedev, M.A.; Nicolelis, M.A. Brain-Machine Interfaces: From Basic Science to Neuroprostheses and Neurorehabilitation. Physiol. Rev. 2017, 97, 767–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagengruber, A.; Quere, G.; Iskandar, M.; Bustamante, S.; Feng, J.; Leidner, D.; Albu-Schäffer, A.; Stulp, F.; Vogel, J. An assistive robot that enables people with amyotrophia to perform sequences of everyday activities. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 8426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, M.; Wild, A.; Orchard, G.; Sandamirskaya, Y.; Guerra, G.A.F.; Joshi, P.; Plank, P.; Risbud, S.R. Advancing Neuromorphic Computing With Loihi: A Survey of Results and Outlook. Proc. IEEE 2021, 109, 911–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrlich, M.; Zaidel, Y.; Weiss, P.L.; Melamed Yekel, A.; Gefen, N.; Supic, L.; Ezra Tsur, E. Adaptive control of a wheelchair mounted robotic arm with neuromorphically integrated velocity readings and online-learning. Front. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 1007736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mounir, R.; Alqasemi, R.; Dubey, R. BCI-controlled hands-free wheelchair navigation with obstacle avoidance. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2005.04209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashali, M.; Wu, L.; Alqasemi, R.; Dubey, R. Controlling a Non-Holonomic Mobile Manipulator in a Constrained Floor Space. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Brisbane, QLD, Australia, 21–25 May 2018; pp. 725–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathirage, I.K.; Alqasemi, R.; Dubey, R.; Khokar, K.; Klay, E.K. Vision Based Brain-Computer Interface Systems for Performing Activities of Daily Living. U.S. Patent 9,389,685, 12 July 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Exact Dynamics. iARM—Intelligent Robot Arm for Your Wheelchair. Robots.nu. Available online: https://robots.nu/en/robot/iarm-intelligente-robotarm-voor-aan-je-rolstoel (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Allen, B.; Bagnati, C.; Dow, E.; Friel, A.; Ibrahim, S.; June, H.; Laten, N.; Le, V.; Manes, E.; McCoy, M.; et al. Report on the Use of Assistive Robotics to Aid Persons with Disabilities. Undergraduate Coursework. 2020. Paper 4. Available online: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1003&context=ugcw (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Catalán, J.M.; Trigili, E.; Nann, M.; Blanco-Ivorra, A.; Lauretti, C.; Cordella, F.; Ivorra, E.; Armstrong, E.; Crea, S.; Alcañiz, M.; et al. Hybrid brain/neural interface and autonomous vision-guided whole-arm exoskeleton control to perform activities of daily living (ADLs). J. NeuroEng. Rehabil. 2023, 20, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, G.; Song, A.; Xu, B.; Li, H.; Hu, C.; Zeng, H. Continuous shared control for robotic arm reaching driven by a hybrid gaze-brain machine interface. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Madrid, Spain, 1–5 October 2018; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 4462–4467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, P. Mind-controlled robotic arm works without brain implant. Tech. Explorist Mar. 2019, 5. Available online: https://www.techexplorist.com/mind-controlled-robotic-arm-works-without-brain-implant/24247/ (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Sliwowski, M. Artificial Intelligence for Real-Time Decoding of Motor Commands from ECoG of Disabled Subjects for Chronic Brain Computer Interfacing. Ph.D. Thesis, Université Grenoble Alpes, Grenoble, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, Y.; Udompanyawit, C.; Zhang, Y.; He, B. EEG-based brain-computer interface enables real-time robotic hand control at individual finger level. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 5401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willsey, M.S.; Shah, N.P.; Avansino, D.T.; Hahn, N.V.; Jamiolkowski, R.M.; Kamdar, F.B.; Hochberg, L.R.; Willett, F.R.; Henderson, J.M. A high-performance brain–computer interface for finger decoding and quadcopter game control in an individual with paralysis. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.H.; Kim, M.; Jo, S. Quadcopter flight control using a low-cost hybrid interface with EEG-based classification and eye tracking. Comput. Biol. Med. 2014, 51, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doud, A.J.; Lucas, J.P.; Pisansky, M.T.; He, B. Continuous three-dimensional control of a virtual helicopter using a motor imagery based brain-computer interface. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e26322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, J.H.; Lee, D.H.; Ahn, H.J.; Lee, S.W. Towards brain-computer interfaces for drone swarm control. In Proceedings of the 2020 8th International Winter Conference on Brain-Computer Interface (BCI), Gangwon, Republic of Korea, 26–28 February 2020; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belkacem, A.N.; Jamil, N.; Khalid, S.; Alnajjar, F. On closed-loop brain stimulation systems for improving the quality of life of patients with neurological disorders. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1085173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillen, A.; Omidi, M.; Díaz, M.A.; Ghaffari, F.; Roelands, B.; Vanderborght, B.; Romain, O.; De Pauw, K. Evaluating the real-world usability of BCI control systems with augmented reality: A user study protocol. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1448584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collinger, J.L.; Wodlinger, B.; Downey, J.E.; Wang, W.; Tyler-Kabara, E.C.; Weber, D.J.; McMorland, A.J.; Velliste, M.; Boninger, M.L.; Schwartz, A.B. High-performance neuroprosthetic control by an individual with tetraplegia. Lancet 2013, 381, 557–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenspon, C.M.; Valle, G.; Shelchkova, N.D.; Hobbs, T.G.; Verbaarschot, C.; Callier, T.; Berger-Wolf, E.I.; Okorokova, E.V.; Hutchison, B.C.; Dogruoz, E.; et al. Evoking stable and precise tactile sensations via multi-electrode intracortical microstimulation of the somatosensory cortex. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2025, 9, 935–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouton, C.E.; Shaikhouni, A.; Annetta, N.V.; Bockbrader, M.A.; Friedenberg, D.A.; Nielson, D.M.; Sharma, G.; Sederberg, P.B.; Glenn, B.C.; Mysiw, W.J.; et al. Restoring cortical control of functional movement in a human with quadriplegia. Nature 2016, 533, 247–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, A. 6-DOF Robotic arm with Omnidirectional Moving Base and Joystick Remote Control. Arduino Project Hub. 2022. Available online: https://projecthub.arduino.cc/ambhatt/6-dof-robotic-arm-with-omnidirectional-moving-base-and-joystick-remote-control-df8d8a (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Ramírez-Moreno, M.A.; Gutiérrez, D. Evaluating a Semiautonomous Brain-Computer Interface Based on Conformal Geometric Algebra and Artificial Vision. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2019, 2019, 9374802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wired Magazine. Synchron’s Brain–Computer Interface Now Has Nvidia’s AI. Wired. 2024. Available online: https://www.wired.com/story/synchrons-brain-computer-interface-now-has-nvidias-ai/ (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- The Australian. Aussie Tech Group Uploads ChatGPT to People’s Brains. The Australian. 2024. Available online: https://www.theaustralian.com.au/business/technology/aussie-tech-company-uploads-chatgpt-to-peoples-brains/news-story/f3e12845ef5fc27251c7c9864ce52c9f (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Jin, J.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, R.; Chen, Y. An Innovative Brain-Computer Interface Interaction System Based on the Large Language Model. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.11659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Hong, K.; Sayyah, Z.; Krolick, M.; Steinberg, E.; Venkatdas, R.; Pavuluri, S.; Wang, Y.; Huang, Z. Hybrid Brain-Machine Interface: Integrating EEG and EMG for Reduced Physical Demand. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.10904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coin, A.; Mulder, M.; Dubljević, V. Ethical Aspects of BCI Technology: What Is the State of the Art? Philosophies 2020, 5, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota, T.d.S.; Sarkar, S.; Poojary, R.; Alqasemi, R. ChatGPT-Based Model for Controlling Active Assistive Devices Using Non-Invasive EEG Signals. Electronics 2025, 14, 2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carìa, A. Towards Predictive Communication: The Fusion of Large Language Models and Brain-Computer Interface. Sensors 2025, 25, 3987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyler, B.J. Ethical Imperatives in the Commercialization of Brain-Computer Interfaces. IBRO Neurosci. Rep. 2025, 19, 718–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Hasan, W.Z.W.; Jiao, W.; Dong, X.; Ramli, H.R.; Norsahperi, N.M.H.; Wen, D. ChatGPT and BCI-VR: A new integrated diagnostic and therapeutic perspective for the accurate diagnosis and personalized treatment of mild cognitive impairment. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1426055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Styler, B.K.; Deng, W.; Chung, C.-S.; Ding, D. Evaluation of a Vision-Guided Shared-Control Robotic Arm System with Power Wheelchair Users. Sensors 2025, 25, 4768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, K.-S.; Khan, M.J. Hybrid brain–computer interface techniques for improved classification accuracy and increased number of commands: A review. Front. Neurorobot. 2017, 11, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Erp, J.B.F.; Lotte, F.; Tangermann, M. Brain–computer interfaces: Beyond medical applications. Computer 2012, 45, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.; Ghosh, L.; Saha, S. Hybrid brain-computer interfacing paradigm for assistive robotics. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2025, 185, 104893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Li, J.; Ji, H.; Jiang, C. A hybrid brain computer interface system based on the neurophysiological protocol and brain-actuated switch for wheelchair control. J. Neurosci. Methods 2014, 229, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Jiao, L.; Yang, S.; Li, H.; Jiang, X.; Feng, J.; Zou, S.; Xu, Q.; Gu, J.; Wang, X.; et al. Brain-computer interfaces: The innovative key to unlocking neurological conditions. Int. J. Surg. 2024, 110, 5745–5762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.; Mamun, K.A.; Ahmed, K.; Mostafa, R.; Naik, G.R.; Darvishi, S.; Khandoker, A.H.; Baumert, M. Progress in Brain Computer Interface: Challenges and Opportunities. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 578875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willett, F.R.; Avansino, D.T.; Hochberg, L.R.; Henderson, J.M.; Shenoy, K.V. High-performance brain-to-text communication via handwriting. Nature 2021, 593, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunner, P.; Ritaccio, A.L.; Emrich, J.F.; Bischof, H.; Schalk, G. Rapid communication with a “P300” matrix speller using electrocorticographic signals (ECoG). Front. Neurosci. 2011, 5, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johns Hopkins Medicine. Neurological Rehabilitation. Available online: https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/treatment-tests-and-therapies/neurological-rehabilitation (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Gouret, A.; Le Bars, S.; Porssut, T.; Waszak, F.; Chokron, S. Advancements in brain-computer interfaces for the rehabilitation of unilateral spatial neglect: A concise review. Front. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1373377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Singh, V.K.; Chorsiya, V.; Chaurasia, R.N. Neurorehabilitation and its relationship with biomarkers in motor recovery of acute ischemic stroke patients—A systematic review. J. Clin. Sci. Res. 2024, 13, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elashmawi, W.H.; Ayman, A.; Antoun, M.; Mohamed, H.; Mohamed, S.E.; Amr, H.; Talaat, Y.; Ali, A. A Comprehensive Review on Brain–Computer Interface (BCI)-Based Machine and Deep Learning Algorithms for Stroke Rehabilitation. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 6347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, M.; Iáñez, E.; Gaxiola-Tirado, J.A.; Gutiérrez, D.; Azorín, J.M. Study of the Functional Brain Connectivity and Lower-Limb Motor Imagery Performance After Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation. Int. J. Neural Syst. 2020, 30, 2050038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abiri, R.; Borhani, S.; Sellers, E.W.; Jiang, Y.; Zhao, X. A comprehensive review of EEG-based brain-computer interface paradigms. J. Neural Eng. 2019, 16, 011001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ienca, M.; Andorno, R. Towards new human rights in the age of neuroscience and neurotechnology. Life Sci. Soc. Policy 2017, 13, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, R.B.; Coffin, T.; Pham, M.; Klein, E.; Marathe, M. Mind the gap: Bridging ethical considerations and regulatory oversight in implantable BCI human subjects research. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2025, 19, 1633627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).