Abstract

In rural areas of Nepal, where it is difficult to get access to Government health care facilities, people depend on medicinal plants and local healers for health problems. This study concerns an ethnobotanical survey of the Kavrepalanchok District, reporting some unusual uses of medicinal plants and original recipes. A total of 32 informants were interviewed, 24 of them being key informants. Ethnobotanical uses concerned 116 taxa, of which 101 were medicinal plants, with the most representative species belonging to Asteraceae, Fabaceae, Lamiaceae, and Zingiberaceae. Ethnobotanical indexes were used to evaluate the ethnopharmacological importance of each plant species and the degree of agreement among the informants’ knowledge. Informant consensus factor (Fic) showed that the fever category had the greatest agreement. Highest fidelity level (FL) values were found for Calotropis gigantea used for dermatological diseases, Drymaria cordata for fever, Mangifera indica and Wrightia arborea for gastrointestinal disorders. Data document the richness of the local flora and the traditional knowledge on medicinal plant species used by ethnic communities in rural areas. The active involvement of local populations in the conservation and management of medicinal plant species will encourage future projects for the sustainable development of the biological and cultural diversity of these rural areas of Nepal.

1. Introduction

Traditional systems of medicine are important health sources spread all over the world, especially in developing countries [1]. Most interesting ethnobotanical data can be generally collected in ethnic communities living in rural areas of remote regions, where Traditional Ethnobotanical Knowledge (TEK) remains often underdocumented without a proper documentation [2]. In such contexts it is pivotal to preserve the interaction between indigenous peoples and their environment to avoid that this knowledge fades out in a few generations. Accordingly, it appears increasingly important the role of TEK for promoting sustainable ecosystems and to develop strategies for protecting and enhancing the natural resources.

In Nepal, out of a total of approximately 28 million inhabitants, 80% lives in rural areas [3,4], where it is difficult to access government health care facilities. It is estimated that there are only 2 physicians per 10,000 people, while in other parts of the world the number is higher, e.g. in Europe there are on average 33 physicians per 10,000 people (minimum Romania 19, maximum Greece 54) [5]. After the earthquake (8 Mw) in April 2015, access to medical care has became even more problematic and rural areas have been exposed to many epidemic diseases, especially among children and elderly people. Therefore, people in these areas depend highly on traditional use of medicinal plants for their primary health care. This traditional knowledge, passed down orally mainly within families or small groups of healers, includes folk, shamanistic and Ayurvedic medicine [6].

Due to its significant variations in altitude, topography and climate, Nepal has an important floral biodiversity with 6500 species of flowering plants and ferns [7] of which 2000 are commonly used in traditional healing practices [8]. Also there is a high diversity in ethnic groups (125), each of them with its own culture, language, religious rites, and traditional practices in the use of medicinal plants [9,10].

The present study is an in-depth investigation of medicinal plants used by ethnic people residing in several villages of Kavrepalanchok District, which are located outside tourist circuits and characterized by a high rate of poverty. Our results integrate previous ethnobotanical studies conducted in this zone of Central Nepal [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27], with a special focus on medicinal plants selected and used by local healers and shamans who are considered the depository of TEK. The data highlight most quoted species in the treatment of specific pathologies, as shown by ethnobotanical indexes. In addition, we have also recorded some unusual uses of medicinal plants and original recipes, as well as the use of species that have never been reported in previous ethnobotanical studies from Central Nepal. The valorisation of folk medicine can promote a sustainable development of the natural resources in these rural areas.

2. Results

A total of 32 informants (26 men and 6 women) aged between 23 and 81 years were interviewed (Table 1).

Table 1.

Distribution of informants gender and age.

About 38% were illiterate (12 informants), 34% had a primary level of literacy (11 informants), about 25% a secondary level (8 informants) and only one informant (3%) had a degree. Among them, 24 were selected as key informants as follows: 8 shamans (jhankris), 2 local healers, 14 farmers and plant traders. The interviewed shamans belonged to the Tamang ethnic group (one was a woman) and the local healers belonged to the Brahmin ethnic group and were experts in Ayurvedic medicine. These informants lived in remote areas and preserved old tradition. In our survey, ethnobotanical knowledge was concentrated among informants with primary education (41%), followed by those with secondary education (33%), and finally by those who had no educational level (22%) while the only one graduate informant corresponded to 4% of the total. The 6 women provided 15% of the information collected.

2.1. Plants Diversity

The informants reported 318 ethnobotanical uses of 116 plants belonging to 57 families (Table 2).

Table 2.

Plants used by ethnic people in Kavrepalanchok District, Central Nepal.

The taxonomic diversity percentage was calculated: the most representative species belonged to Asteraceae (10.34%), Fabaceae (6.03%), Lamiaceae (5.17%) and Zingiberaceae (4.31%) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Taxonomic diversity of recorded plants species.

Among them the most representative were herbs (36.20%), followed by trees (26.72%), shrubs (25%), climbers (8.62%) and parasitic plants species (1.72%); further, two ferns were also recorded (1.72%). These data are indicative of the richness of the local flora and testify the botanical knowledge of the informants, in accordance with previous studies conducted in Central Nepal [28,29].

2.2. Ethnomedicinal Uses of Plants

About 87% of the 116 species (101) was reported for medicinal purposes, with 271 citations of uses. Among these species, 20 were reported also in other categories, particularly as food and food/medicine (11) and religious/ritual (6). Minor uses concerned domestic, handcraft, and agropastoral categories. The plants used were mostly wild plants easy to find, in particular, herbs, trees and shrubs growing near villages. Sometimes even some cultivated plants were used for medicinal purposes (Figure 1A).

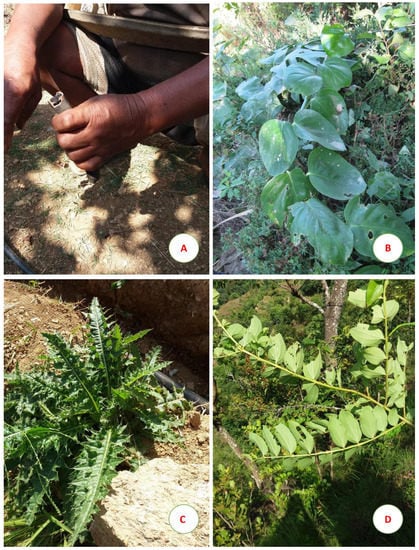

Figure 1.

(A) Rhizome of Cautleya spicata; (B) Medicinal plants search during a jungle walk around Mukpatar village; (C) Ficus semicordata used for gastric problems; (D) Oxalis corniculata, remedy for the treatment of various diseases.

More rarely, hard-to-find plants were also selected, such as Viscum articulatum, Piper retrofractum and Picrasma quassioides that grow in inaccessible areas of the forest (Figure 1B). Medicinal plants were used by informants to treat 13 categories of human ailments and 1 related to cattle diseases (Table 4); 48 species were used to treat only one disease (e.g., Ficus semicordata, Figure 1C) and 53 species to treat more than one ailment (e.g., Oxalis corniculata, Figure 1D).

Table 4.

Ailments included in each illness category.

The most frequent disease categories treated with medicinal plants and showing the highest citations, were those concerning fever, digestive system, skeletal and muscular system, and skin diseases (56, 45, 30 and 25 citations, respectively). Traditional healers identified the diseases according to traditional patient examination, including inspection of tongue, skin, throat, eyes (red eyes, yellow eyes, etc.), feces, urine, external features (i.e., swelling), bleeding, body temperature.

Despite recent influences from Western medicine, ethnic people continue to rely on traditional medicine. This seems to confirm the therapeutic efficacy of local plants for the treatment of the most common and widespread pathologies [30].

2.3. Herbal Remedies

For medicinal preparations, roots, and rhizomes (23.61%), whole plant (22.88%), followed by bark and fruits (about 10% respectively) were used (Table 5).

Table 5.

Plant parts used in the preparation of medicine.

The preference in selecting portions of plants could be related both to their availability during the year and to the higher concentration of active ingredients. For example, most informants considered the part of the stem closest to the ground or underground portions more effective from a therapeutic point of view. The preferential use of roots and rhizomes was also reported by Bhattarai [31] in its ethnobotanical survey carried out in Ilam District, Eastern Nepal. On the contrary, the study of Luitel et al. [26] in the Makwanpur District of Central Nepal found that the most frequent portions used for medicinal purposes were fruits/seeds, followed by whole plants and leaves.

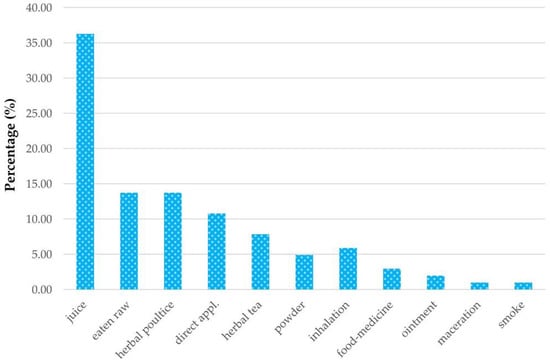

Considering only the 98 plant species used in human ailments, the informants reported various medicinal preparation forms. These were based on a single plant or were polyherbal formulations, fresh juice was the preferred form (36.27%) due to the simplicity of preparation by crushing the plant in a stone mortar and because this was also an excellent way of getting vitamins and minerals from the plant. The juice had to be taken within a short time after being prepared. Even raw plants (13.72%) were eaten for therapeutic purposes, especially roots, fruits, seeds, and tubers. Herbal poultices (13.72%) included “poultice”—generally prepared by crushing the plant portions to a pulpy mass - and “compresses” made of a piece of cloth soaked in the plant decoction or infusion. Other preparation forms were direct application (10.78%), herbal teas (7.84%), including decoction and infusion, inhalation (5.88%), powder (4.9%), vegetable used as food-medicine (2.94%), ointment (1.96%), maceration and smoke (0.98%, respectively) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Histogram of the relative frequencies of the medicinal preparation forms used.

The informants generally preferred fresh plants because they found them more effective. Plant parts were generally prepared using hot or cold water as a solvent, but other solvents such as milk, honey, lemon juice and rapeseed oil were occasionally employed.

Single herbs, or multiple herbs combined to obtain original recipes, can be used. Particularly, a Newar medicinal recipe, used to treat various ailments, was found to be in practice. It is prepared with aerial parts of Artemisia indica, Centella asiatica, Drymaria cordata, Mentha spicata, Oxalis corniculata (Figure 1D), Tagetes erecta, seeds of Oroxylum indicum, sprouts dried of Oryza sativa, wood of Picrasma quassioides and limestone powder. A typical feature of Newari medicine is that different medicinal plants can be used to treat a number of diseases [32].

Herbal remedies for human ailments were administered through different routes: internal use (66.33%), topical application (23.47%), nasal application and others (10.2%).

The prescribed quantity was always approximate, depending on how the healer judged the severity of the disease. The frequency of taking the medicines has been described in terms of the number of times in a day and the duration as for number of days or weeks.

2.4. Data Analysis

To evaluate the ethnopharmacological importance of each plant species and the degree of agreement among informants some ethnobotanical indices were calculated. The informant consensus factor (Fic) was used to highlight medicinal plants of particular cultural relevance and the degree of agreement of informants about each category of ailments. The different ailments and diseases were classified into 14 categories (see Table 4) and a Fic value for each category was calculated. The results showed that fever category had the greatest agreement (0.49), followed by gastrointestinal and dermatological categories (0.29). Intermediate agreement among informants was recorded for metabolic, oral/dental/ENT (0.28) and musculoskeletal (0.21) categories, while the others had a Fic lower than 0.20 (Table 6).

Table 6.

Informants consensus factor (Fic) by categories of diseases, calculated only for several use reports ≥ 15.

The fidelity level (FL) was used to identify the most preferred species for treating certain ailments, showing that the most quoted species were Calotropis gigantea (100%) for dermatological diseases, Drymaria cordata (100%) against fever, Mangifera indica and Wrightia arborea (100%) for gastrointestinal disorders. For treatment of fever also Oxalis corniculata and Centella asiatica were reported, with a FL of 80% and 75%, respectively. Notably a FL of 75% was also found for Curcuma caesia for treatment of maternal ailments. To better underline the therapeutic properties of the most cited medicinal plants, we have reported some information on their main chemical compounds probably involved in the specific curative effect (Table 7), based on recent pharmacological investigations [33,34,35,36,37,38,39].

Table 7.

Fidelity level (FL) value of medicinal plants against a given ailment category and main chemical compounds allegedly responsible for the therapeutic effects.

Plant species with highest relative frequency of citation (RFCs) were Achyranthes bidentata (0.28), Calotropis gigantea and Drymaria cordata (0.16), followed by Artemisia indica, Centella asiatica, Curcuma caesia, Daphne papyracea and Oxalis corniculata (0.13, respectively) (Table 8).

Table 8.

Relative frequency of citation (RFCs) has been reported only for a value ≥ 0.1.

3. Discussion

Our results were in good accordance with other ethnobotanical studies carried out in Nepal and more in general, with the heritage of Traditional Asian Medicine. For example, the use of the latex from Calotropis gigantea for treatment of dermatological diseases (FL 100%) has been previously reported [23,40,41]. This plant is well-known in Ayurvedic medicine, reporting its many medicinal properties, including antimicrobial, antidiarrhoeal, antibacterial, antioxidant, anti-pyretic, and cytotoxic activities [42].

The antipyretic effects of Drymaria cordata (FL 100%), previously reported [43], can be associated with its content in saponins and related phytosterols, as well as phenols [34]. In addition, our informants have referred another medicinal use of plant juice drunken for the treatment of rhinitis and sinusitis. The same use of this plant has also been indicated in other areas of Nepal, but in this case the remedy administration was carried out by inhalation or fumigations [44,45].

Mangifera indica is a common tree in the home gardens of villages. Our informants described the use of the ripe mango peel to treat various gastrointestinal disorders (FL 100%). The use of this species for this category disease is confirmed by other studies on the folk medicine of Nepal [40], but bark and roots are generally the portions to which the greatest curative efficacy is attributed [23,46]. Therefore, the medicinal use of the fruit peel is typical of the survey area.

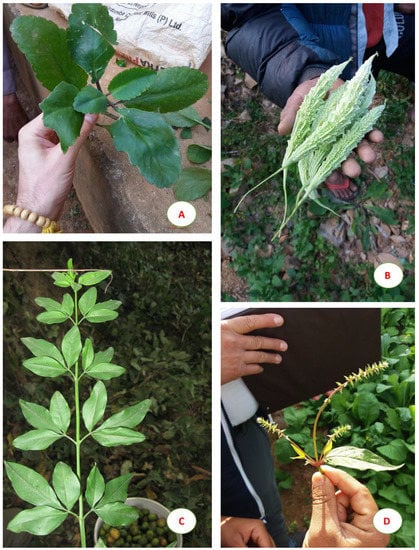

Another plant species showing 100% FL indicated by our informants for gastrointestinal problems was Wrightia arborea (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Informant with a pod of (A) Wrightia arborea; (B) Rhaphidophora glauca; (C) Cirsium wallichii; (D) Coriaria nepalensis.

This plant, belonging to the Apocynaceae family, is widely used in Ayurveda, Siddha, and other traditional medicines to treat various human diseases [47]. The bark is used as an antidote against snake bites and scorpion stings, for curing menstrual and renal complaints and for its antipyretic and antibacterial activities. The root is used to bring relief in case of headache and fever, while the leaves as a diaphoretic, expectorant and to treat dysentery, toothache, and diarrhea [48,49]. In our survey, we found a previously unknown use of the W. arborea pod septum, consumed raw to cure intestinal disorders.

We also compared our data with those from previous studies conducted among ethnic communities living in hilly rural areas of the Kavrepalanchok District [16,17], and in neighboring districts of Central Nepal [19,20,23,24,25,26,27]. Such comparison (Table 2) revealed that 77 of the plant species (66%) had already been mentioned and that 44 of them (38%) had been indicated for similar uses in at least one case. Therefore, we have focused our attention on species or on unusual medicinal uses of plants that had not been referred previously.

Although mixing medicinal plants and minerals—like black salt, “chuna” (limestone powder) iron, copper, “silajeet” (Asphaltum punjabianum), alum, etc.—is a common practice among shamans and local healers (also for making “buti”, or amulets) [50], in our survey we found some original recipes. For example, pieces of copper were added to the bark of Ficus semicordata to make a preparation for treating bloody diarrhea. Another special combination of plants and mineral powder was used by Newar healers against many diseases such as fever, joint pain and others. These plants included aerial parts from Centella asiatica, Tagetes patula, Mentha spicata, Oxalis corniculata, Drymaria cordata and Artemisia indica, seeds of Oroxylum indicum, dry shoots of Oryza sativa, and wood of Picrasma quassioides Notably, P. quassioides is not present in any of the previous studies on the ethnobotany of the Tamang people. Its wood contains quassinoids with anticancer and antimalarial activity [51], other than a number of medicinal compounds with anthelmintic, antiamoebal, antiviral, bitter, hypotensive, and stomachic properties [52].

Another interesting use was reported for Rhaphidophora glauca (Figure 3B), an aroid liane native to the subtropical and warm temperate Himalayan regions. The juice obtained from the aerial parts was administered to women to improve pregnancy. Similar uses are reported for related Indian species such as R. hookeri whose stem juice was indicated for pregnant women [53], and R. pertusa, that showed luteolytic, oestrogenic, and follicle-stimulating activities in cattle and buffaloes [54]. Interestingly, none of the previous studies on Tamang folk medicine cited this specific use for this genus. On the contrary, the most common medicinal use of different Rhaphidophora species, i.e., the treatment of bone fractures in human and cattle [55,56], was not reported by our informants.

Arenaria benthamii, belonging to the Caryophyllaceae family, has been employed to fill pillows in case of cold and cough, and to reduce nasal mucus. Although the balsamic properties of this species and of other Caryophyllaceae, such as Gypsophila arrostii Guss. and G. oldhamiana Miq., are known [57], this route of administration had never been reported previously.

Another new finding concerns the use of root juice from Strobilanthes pentastemonoides for the treatment of high fever, while other studies only reported the use of this plant like fodder [58,59].

The stem juice obtained from branchlets of Cipadessa baccifera was highly regarded by shamans as a good remedy for counteracting food and drink poisoning. This use had never been previously reported, but a few studies have shown the effectiveness of this plant as an antidote against snake, scorpion, and insect bites [60,61].

Our informants reported that the root juice of Cirsium wallichii (Figure 3C) was useful for urinary problems, weakness, and malarial fever. Other studies cited the root of this species to treat gastric problems [62], while recently this species has been investigated also for antimicrobial and antioxidant properties shown by leaf, inflorescence, and bark extracts [63].

The use of the ripe fruits and plant juice of Coriaria nepalensis (Figure 3D) in case of indigestion is unexpected, because the leaves and fruits of many Coriaria species are considered poisonous in Asia, due to the presence of coriamyrtin with convulsive effects [64]. Nevertheless, in Chinese Traditional Medicine this species is used to treat various diseases [65], and the leaf juice was indicated as antiseptic among the Newar community of Kathmandu District [32].

The Crassulacea Bryophyllum pinnatum (Figure 4A) was described by our informants as useful against kidney stones, in agreement with other studies [66,67,68].

Figure 4.

(A) Bryophyllum pinnatum; (B) Fruits of Momordica charantia; (C) Jasminum mesnyi; (D) Achyranthes bidentata.

Momordica charantia (Figure 4B) is commonly used in the traditional medicine of different developing countries for its multiple properties, especially as antidiabetic [69]. In our study, this plant was mainly used by local people to lower blood pressure. Such effect, also reported in African folk medicine, was tested on normal and diabetic rats showing that an aqueous extract possesses hypoglycaemic and hypotensive properties [70].

Jasminum mesnyi (Figure 4C), commonly known as Japanese jasmine, has been reported in our survey to cure fever and typhoid. The antimicrobial potential of the leaf extract of this species has been recently demonstrated on Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacterial pathogens [71].

Achyranthes bidentata, (Figure 4D) belonging to Amaranthaceae, is a well-known medicinal plant very common near the villages and used by local people to treat various diseases such as fever (FL about 33%) and maternal ailments (FL about 44%). Accordingly, this species showed the highest relative frequency of citation. These findings are a novelty, because a previous study on the same area reported only the use of this species for the treatment of urinary ailments [16].

Finally, twelve of the 116 plants cited by our informants are also traded in the streets of the Kathmandu Valley for the preparation of popular medicinal remedies, being a valuable source of income for local people [72]: Acorus calamus, Asparagus racemosus, Bergenia ciliata, Cautleya spicata, Curcuma angustifolia, Osyris wightiana, Phyllanthus emblica, Rubus ellipticus, Stephania glandulifera, Terminalia bellirica, Tinospora sinensis, and Valeriana jatamansi.

Some informants (especially plant traders) referred that there is a great demand of Asparagus racemosus roots, because they are useful for stimulating milk production in buffaloes. For this reason, the collection and trade of this species should be controlled to prevent environmental depletion.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Area and Ethnic People

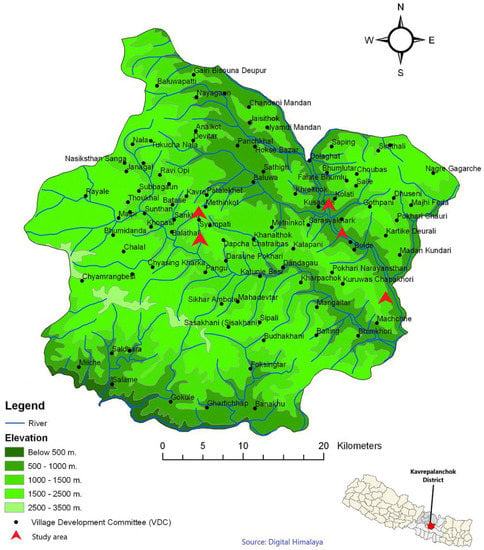

The Bagmati Pradesh (State) of Nepal comprises 13 districts, namely Sindhuli, Ramechhap, Dolakha, Sindhupalchok, Kavrepalanchok, Lalitpur, Bhaktapur, Kathmandu, Nuwakot, Rasuwa, Dhading, Makwanpur and Chitwan Districts. At the time of the 2011 Nepal census, Kavrepalanchok District had a population of 381,937. Of these, 50.9% spoke Nepali, 33.5% Tamang, 11.1% Newari, 1.6% Danuwar and 1.4% Magar as their first language [9]. The Kavrepalanchok District is located between 85°24’ to 85°49’ E and 27°22’ to 27°85’ N, with altitudes ranging from 275 (Dolalghat/Sunkoshi River) to 3018 m ASL (Bethanchowk hill). The total area is about 1396 km2 and the average temperature ranges from 10° to 31 °C [13]. This region has a subtropical climate and its vegetation is characterized by the forest of Schima sp., Castanopsis sp., Pinus roxburghii and Alnus nepalensis at the lower belt, while broad leaved oak forests of Quercus spp. are found at upper belt [73]. The Kavrepalanchok District consists of 13 Municipalities, out of which six are urban municipalities and seven are rural ones. The present survey was undertaken in six villages of the Temal Rural Municipality: Mukpatar (27°28’ N 85°48’ E), Maure (27°31’ N 85°45’ E), Chukha (27°32’ N 85°43’ E), Maure Bhanjyang (27°32’ N 85°44’ E), Lamagaun (27°33’ N 85°43’ E), Rackse Dhara (27°33’ N 85°43’ E), and in addition in the neighboring villages of Namo Buddha (27°34’ N 85°35’ E, Namobuddha Municipality) and Nyaupane Sanogon (27°33’ N 85°34’ E, Balthali Village Development Committee, VDC) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Map of the study area with the surveyed villages.

This area is about 100 km far from Kathmandu and its villages are mainly occupied by the Tamang community. Although this rural area is not too far from the city centers, people living here are very deprived of basic infrastructures and facilities. Many people are illiterate and therefore the major portion of population is involved in agriculture, which is mostly subsistence farming. Some people are engaged in tourism industry as porters and guides, like drivers or other occupation. Since educational facilities for children are lacking and parents often consider education a trivial factor in life, children are not encouraged to get an education.

The criterion used in choosing the villages for this study was to have a sufficiently homogeneous survey area in terms of culture and land use. The informants belonged to the Tamang ethnic group (27 informants), and to other minor communities living in the study area, like Newar (2 informants) and Brahmin (3 informants). Tamang are one of the major Tibeto-Burmese speaking communities in Nepal, originating from Tibet. In Tibetan language “Ta” means horse and “Mang” means traders. So probably Tamang originally were horse traders. They account for 5.8% of the total people of the country [9] and currently most of them lives in the hilly regions of Nepal, adjoining sides of the Kathmandu valley.

In the study area the Tamang is the main ethnic group, while the other groups represent a minority. In the rural villages, small Newar and Brahmin family groups have been present for a few generations, with a consequent exchange of ethnobotanical traditions. For this reason, the proportional composition of our informants reflects this ethnic distribution.

Tamang people have a rich traditional knowledge linked to plants and animals, nevertheless only a few ethnobotanical studies concerned this culture [12,16,19,25,74,75]. According to the animistic vision of Tamang, the world is populated by numerous spirits living in nature and responsible for many events of life. Evil spirits, angry ghosts (pichas), and witches (bokshi) should be the cause of balance alterations in the human organism that cause diseases. The shamans (jhankris), acting as mediators between the spiritual and the material world, have developed techniques to identify the evil spirits, rituals to expel them, such as mantra (secret whisper) and amulets, and herbal preparations for humans and animals [76,77]. A few informants from the study area belonged to the Newar and Brahmin ethnic groups. The Newar are the indigenous inhabitants of the Kathmandu Valley and are known for their rich artistic and cultural tradition. Their main occupations are agriculture and plant trade [58]. Brahmin (Bahuns in Nepali Language) represent one of the Hindu Nepalese castes, and not a distinguished ethnic group. They live in the central area of Nepal, occupying fertile agricultural land at the foot of the Himalayan mountain range [78].

4.2. Field Survey and Data Collection

The present study was carried out in the months of October and November of 2017 and 2018, after the monsoon season. During two previous study trips (2015–2016) contacts were made with the local community in order to gather information on his daily habits, work, and relationship with the natural environment. Ethnobotanical and ethnomedicinal data on plants has been collected by interviewing 32 informants from the different villages of the study area.

For the choice of the typology and number of informants we have followed the “purposive sampling” approach according to Tongco [79], a nonrandom method, where the informants are selected by virtue of knowledge and experience. In our case, such key informants are the persons recognized by the community as depository of traditional knowledge about medicinal plants. This approach allows to collect a high amount of reliable data with a low number of interviews.

Key informants (24) were traditional healers selected by the following criteria: experience (local healers and shamans); age (knowledgeable elder villagers); occupation (farmers and plant traders).The interviews were conducted in Tamang and Nepali Language with the help of a bilingual speaking local guide. The data has been collected in compliance with the rules of the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) related to traditional cultural expressions [80], and of the ethical guidelines of the international society of ethnobiology (ISE) [81]. The purposes and modalities of the research were carefully communicated to the informants and a prior informed consent (PIC) was obtained [82].

Different interviews and inquiry methods were followed, according to Martin [83] and Alexiades [84]: (a) informants were asked to freely list all plants of a certain ethnobotanical interest, with special attention to plants used for medicinal purposes (free listing); (b) healers and shamans were accompanied on their excursions in search of medicinal plants and followed during the healing ceremonies and herbal remedies preparation (walk-in-the-woods and participant observation). Some difficulties have been found in interviews with shamans because of the belief that revealing the medicinal properties of a plant deprives it of the therapeutic efficacy; (c) samples of plants were shown to the informants, asking them to identify species of ethnobotanical interest (specimen display); (d) small groups of people were interviewed about their ethnobotanical knowledge using the specimen display method (group interviews).

All information was collected through semi-structured questionnaires, including questions on the informants (gender, age, ethnic group, occupation, educational level, birth place, residence place, interview place, etc.), and the plants (local name, growth form, habitat, parts used, uses, preparation and routes of administration of herbal medicine). Plant specimens were collected and partly identified in the field with the help of local guides [58,85,86], and partly by one of us in the laboratory (RPC). The set of plant specimens was deposited in the Tribhuvan University Central Herbarium (TUCH), Nepal, with voucher numbers [87]. Plant nomenclature follows Plant of the World [88].

4.3. Quantitative Analysis

The collected data include plant species name, family, local name, altitude, location, voucher specimen number, parts used and ethnomedicinal uses. The data were then processed in ethnobotanical indices: Fic (informant consensus factor), FL (fidelity level), RFCs (relative frequency of citation), as followed.

4.3.1. Informants Consensus Factor (Fic)

Informants consensus factor was calculated in order to find out the homogeneity in the information given by informants. This index is calculated for each ailment category with the following formula [89,90].

where Nur is the number of use reports in a particular illness category, and Nt the number of taxa or species used to treat that particular category. A high Fic value indicates the agreement among the informants on the use of taxa for a certain disease category.

4.3.2. Fidelity Level (FL)

The fidelity level (FL) is the percentage of informants claiming the use of a certain plant for the same major purpose, and is calculated according to the following formula [84,91]:

where Np is the number of informants that claim the use of a plant species to treat a particular disease, and N the number of informants that use the same plant as a medicine to treat any disease.

4.3.3. Relative Frequency of Citation (RFCs)

This index is used to determine the local importance of each species in the study area. The formula used, according to Tardìo and Pardo-de-Santayana [92] is:

where FCs is the number of informants that cites the use of a plant species, and N the total number of informants.

5. Conclusions

The present study shows that the ethnic community, living in rural areas of the Kavrepalanchok District, still retains a rich traditional knowledge of medicinal plants which are an important source for primary health care. In fact, although some allopathic medicines are available in government “health posts”, most indigenous peoples rely on traditional local healers and shamans for their primary health care needs. Despite the close relationship with wilderness in this area, we have observed that this heritage is at risk. Young people are generally attracted to urban and Western lifestyles, and sometimes do not fully understand the value of traditional knowledge. Our data could be of help to the people of the rural municipalities of this area in order to plan bioconservation strategies. A recent example in the Temal region concerns an endemic species of handicraft interest, Ziziphus budhensis, which is cultivated and traded for Buddhist rosaries.

Similarly, the plants for which we have found novel therapeutic uses could be subjected to pharmacognostic investigation and cultivated in dismissed agricultural lands, turning them into a source of income and valorisation of the territory.

Therefore, the uses of medicinal plants in this area need to be explored and documented before oral traditions are lost forever. The active involvement of local populations in the valorisation, conservation, and management of medicinal plants will encourage future projects aimed at the sustainable development of the biological and cultural diversity of these rural areas of Nepal.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: G.A., L.C.; methodology and investigations, G.A., L.C., R.P.C., M.M.; writing—original draft preparation, G.A., L.C.; supervision, L.C., M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

G.A. is the recipient of a Miur PhD scholarship: XXXIII Course STAT—Distav, University of Genoa, Italy. The cultural association “In Cammino” (Piazza dei Cappuccini, 1, 16122 Genova, Italy) has provided a partial funding to the expenses incurred in Nepal.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks are due to the informants of Kavrepalanchok District (Central Nepal) and to our local guide Rajesh Lama Tamang and his team.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- WHO Global Report on Traditional and Complementary Medicine 2019; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- Adhikari, M.; Thapa, R.; Kunwa, R.M.; Devkota, H.P.; Poudel, P. Ethnomedicinal Uses of Plant Resources in the Machhapuchchhre Rural Municipality of Kaski District, Nepal. Medicines 2019, 6, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World Population Prospects 2019. 2019. Available online: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo/ (accessed on 6 September 2019).

- The World Bank Data. Rural Population. Available online: http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.RUR.TOTL.ZS (accessed on 17 September 2019).

- WHO. World Health Statistics 2010. Available online: http://who.int/gho (accessed on 16 September 2019).

- Aryal, K.K.; Dhimal, M.; Pandey, A.; Pandey, A.R.; Dhungana, R.; Khaniya, B.N.; Mehta, R.K.; Karki, K.B. Knowledge Diversity and Healing Practices of Traditional Medicine in Nepal; Nepal Health Research Council: Kathmandu, Nepal, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Press, J.R.; Shrestha, K.K.; Sutton, D.A. Annotated Checklist of the Flowering Plants of Nepal; Natural History Museum: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Gaire, B.P.; Subedi, L. Medicinal plant diversity and their pharmacological aspects of Nepal Himalayas. Pharmacogny J. 2011, 3, 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Population and Housing Census (NPHC) 2011; Central Bureau of Statistics: Kathmandu, Nepal, 2012.

- Niroula, G.; Singh, N.B. Religion and Conservation: A Review of Use and Protection of Sacred Plants and Animals in Nepal. J. Inst. Sci. Technol. 2015, 20, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kunwar, R.M.; Bussmann, R.W. Ethnobotany in the Nepal Himalaya. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2008, 4, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattarai, N.K. Herbal Folk Medicines of Kabhrepalanchok District, Central Nepal. Int. J. Crude Drug Res. 1990, 28, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manandhar, N.P. Medicinal plant lore of Tamang tribe of Kabhrepalanchok District, Nepal. Econ. Bot. 1991, 45, 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhetri, R.B.; Gauchan, D.P. Traditional knowledge in fruit pulp processing of Lapsi in Kavre district. Indian J. Trad. Knowl. 2007, 6, 46–49. [Google Scholar]

- Pratik, A.; Roshan, K.C.; Kayastha, D.; Thapa, D.; Shrestha, R.; Shrestha, T.M.; Gyawali, R. Phytochemical Screening and Anti-Microbial Properties of Medicinal Plants of Dhunkharka Community, Kavrepalanchowk, Nepal. Int. J. Pharm. Biol. Arch. 2011, 2, 1663–1667. [Google Scholar]

- Malla, B.; Chhetri, R.B. Indigenous knowledge on ethnobotanical plants of Kavrepalanchowk District. Kathmandu Univ. J. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2009, 5, 96–109. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, S.; Lamichhane, D. Documentation of Indigenous Knowledge on plants used by Tamang Community of Kavrepalanchok District, Central Nepal. J. Plant Res. 2017, 15, 45–51. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattarai, N.K. Ethnobotanical studies in Central Nepal: The ceremonial plants food. Contrib. Nepalese Stud. 1989, 16, 35–41. [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha, P.M.; Dhillion, S.S. Medicinal plant diversity and use in the highlands of Dolakha district, Nepal. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2003, 86, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamang, G. An ethnobiological study of Tamang people. Our Nat. 2003, 1, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunwar, R.M.; Nepal, B.K.; Sigdel, K.P.; Balami, N. Contribution to the Ethnobotany of Dhading District, Central Nepal. Nepal J. Sci. Technol. 2006, 7, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, K.; Joshi, A.R. Ethnobotanical Studies on Some Lower Plants of the Central Development Region, Nepal. Ethnobotanical Leaflets 2008, 12, 832–840. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattarai, S.; Chaudhary, R.P.; Taylor, R.S. Ethno-medicinal Plants Used by the People of Nawalparasi District, Central Nepal. Our Nat. 2009, 7, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, K.; Joshi, R.; Joshi, A.R. Indigenous knowledge and uses of medicinal plants in Macchegaun Nepal. IJTK 2011, 10, 281–286. [Google Scholar]

- Thapa, S. Medico-ethnobotany of Magar Community in Salija VDC Parbat district, Central Nepal. Our Nat. 2012, 10, 176–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luitel, D.R.; Rokaya, M.B.; Timsina, B.; Munzbergovà, Z. Medicinal plants used by the Tamang community in the Makawanpur district of Central Nepal. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2014, 10, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamang, R.; Sedai, D.R. Documentation of Ethnomedicinal Knowledge on Plant Resources Used by Baram Community in Arupokhari VDC, Gorkha District, Central Nepal. Bull. Dept. Plant Res. 2016, 38, 60–64. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattarai, S.; Chaudhary, R.P.; Quave, C.L.; Taylor, R.S.L. The use of medicinal plants in the transhimalayan arid zone of Mustang district, Nepal. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2010, 6, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrestha, N.; Shrestha, S.; Koju, L.; Shrestha, K.K.; Wang, Z. Medicinal plant diversity and traditional healing practices in eastern Nepal. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 192, 292–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bechan, R.; Prasad, K.D. Present status of traditional healthcare system in Nepal. Int. J. Res. Ayurveda Pharm. 2011, 2, 876–882. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattarai, K.R. Ethnobotanical study of plants used by Thami community in Ilam District, eastern Nepal. Our Nat. 2018, 16, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balami, N.P. Ethnomedicinal uses of plants among the Newar Community of Pharping Village of Kathmandu District, Nepal. Tribhuvan Univ. J. 2004, 24, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saratha, V.; Pillai, S.I.; Subramanian, S. Isolation and characterization of lupeol, a triterpenoid from Calotropis gigantea latex. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Rev. Res. 2011, 10, 54–57. [Google Scholar]

- Akindele, A.J.; Ibe, I.F.; Adeyemi, O.O. Analgesic and antipyretic activities of Drymaria cordata (Linn.) Willd (Caryophyllaceae) extract. Afr. J. Tradit. Complement. Altern. Med. 2012, 9, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kuganesan, A.; Thiripuranathar, G.; Navaratne, A.N.; Paranagama, P.A. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities of peels, pulps and seed kernels of three common mango (Mangifera indica L.) varieties in Sri Lanka. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Res. 2017, 8, 70–78. [Google Scholar]

- Raghavendra, M.P.; Satish, S.; Raveesha, K.A. Phytochemical analysis and antibacterial activity of Oxalis corniculata; a known medicinal plant. my Sci. 2006, 1, 72–78. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, J.Y.; Rong Jiang, X.G.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, L. Antipyretic and Anti-inflammatory Effects of Asiaticoside in Lipopolysaccharide-treated Rat through Up-regulation of Heme Oxygenase-1. Phytother. Res. 2012, 27, 1136–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donipati, P.; Sreeramulu, S.H. Preliminary Phytochemical Screening of Curcuma caesia. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci 2015, 4, 30–34. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, C.-K.; Gao, J.; Ma, R.-L.; Xu, X.-X.; Huang, P.; Ni, S.-D. Research on analgesic and anti-inflammatory and invigorate circulation effects of total saponins of Achyranthes. Anhui Med. Pharm. J. 2003, 7, 248–249. [Google Scholar]

- Tamang, R.; Thakur, C.K.; Koirala, D.R.; Chapagain, N. Ethno-medicinal Plants Used by Chepang Community in Nepal. J. Plant Res. 2017, 15, 21–30. [Google Scholar]

- Acharya, R.; Acharya, K.P. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used by Tharu community of Parroha VDC, Rupandehi District, Nepal. Sci. World 2009, 7, 80–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarti, C. A review on pharmacological and biological properties of Calotropis gigantea. Int. J. Recent Sci. Res. 2014, 5, 716–719. [Google Scholar]

- Chopra, R.N.; Nayar, S.L.; Chopra, I.C. Glossary of Indian Medicinal Plants (Including the Supplements); CSIR: New Delhi, India, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattarai, K.R. Ethnomedicinal Practices of the Lepcha Community in Ilam, East Nepal. J. Plant Res. 2017, 15, 31–44. [Google Scholar]

- Bantawa, P.; Rai, R. Studies on ethnomedicinal plants used by traditional practitioners, Jhankri, Bijuwa and Phedangma in Darjeeling Himalaya. Nat. Prod. Rad 2009, 8, 537–541. [Google Scholar]

- Paudyal, S.K.; Ghimire, G. Indigenous Medicinal Knowledge among Tharus of Central Dang. A note on gastro-intestinal diseases. In Proceedings of the two-days conference on Gender, Education and Development, and Indigenous Knowledge and Health Practices, Kathmandu, Nepal, 21–22 December 2005; CERID: Balkhu, Nepal, 2006; Volume 22, pp. 98–105. [Google Scholar]

- Divakar, M.C.; Lakshmi Devi, S.; Panayappan, L. Pharmacognostical Investigation of Wrightia Arborea Leaf. J. Chem. Pharm. Res. 2010, 2, 117–121. [Google Scholar]

- Ngan, P.T. A Revision of the Genus Wrightia (Apocynaceae). Ann. Mo. Bot. Gard. 1965, 52, 114–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khyade Mahendra, S.; Vaikos Nityanand, P. Pharmacognostic evaluation of Wrightia arborea (Densst.) Mabb. Int. J. Res. Ayurveda Pharm. 2014, 5, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, M.R. Use of Medicinal Plants in Traditional Tibetan Therapy System in Upper Mustang, Nepal. Our Nat. 2006, 4, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houël, E.; Stien, D.; Bourdy, G.; Deharo, E. Quassinoids: Anticancer and antimalarial activities. In Natural Products: Phytochemistry, Botany and Metabolism of Alkaloids, Phenolics and Terpenes; Ramawat, K., Mérillon, J.M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 3775–3802. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Regional Office for the Western Pacific. Medicinal Plants in the Republic of Korea: Information on 150 Commonly Used Medicinal Plants; WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific: Manila, Philippines, 1998; pp. 204–205. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, B. Arboreal Flora of Nokrek Biosphere Reserve, Meghalaya. Ph.D. Thesis, Gauhati University, Guwahati, India, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Santhosh, C.R.; Shridhar, N.B.; Narayana, K.; Ramachandra, S.G.; Dinesh, S. Studies on the luteolytic, oestrogenic and follicle-stimulating hormone like activity of plant Rhaphidophora pertusa (Roxb.). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2006, 107, 365–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dash, P.K.; Sahoo, S.; Bal, S. Ethnobotanical Studies on Orchids of Niyamgiri Hill Ranges, Orissa, India. Ethnobot. Leafl. 2008, 12, 70–78. [Google Scholar]

- Suneetha, J.; Prasanthi, S.; Ramarao Naidu, B.V.A.; Seetharami Reddi, T.V.V. Indigenous phytotherapy for bone fractures from Eastern Ghats, Andhra Pradesh. Indian J. Tradit. Knowl. 2011, 10, 550–553. [Google Scholar]

- Chandra, S.; Rawat, D.S. Medicinal plants of the family Caryophyllaceae: A review of ethno-medicinal uses and pharmacological properties. Integr. Med. Res. 2015, 4, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manandhar, N.P. Plants and People of Nepal; Timber Press: Portland, OR, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rijal, A. Surviving on Knowledge: Ethnobotany of Chepang community from midhills of Nepal. Ethnobot. Res. Appl. 2011, 9, 181–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandhya Sri, B.; Seetharami Reddi, T.V.V. Traditional phyto-antidotes used for snakebite by Bagata tribe of Eastern Ghats of Visakhapatnam district, Andhra Pradesh. Int. Multidiscip. Res. J. 2011, 1, 42–45. [Google Scholar]

- Murugammal, S.; Ilavarasan, R. Phytochemical standardization of the leaves of a medicinal plant Cipadessa baccifera Roth Miq. J. Pharm Res. 2016, 10, 609–613. [Google Scholar]

- Uniyal, S.K.; Singh, K.N.; Jamwal, P.; Lal, B. Traditional use of medicinal plants among the tribal communities of Chhota Bhangal, Western Himalaya. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2006, 2, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.U.; Ajaib, M.; Anjum, M.; Siddiqui, S.Z.; Malik, N.Z. Investigation of Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Activities of Cirsium wallichii DC. Biologia (Pakistan) 2016, 62, 297–304. [Google Scholar]

- DeFilipps, R.A.; Krupnick, G.A. The medicinal plants of Myanmar. PhytoKeys 2018, 102, 1–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.Y.; Tian, J.M.; Zhang, C.C.; Luo, B.; Gao, J.M. Picrotoxane Sesquiterpene Glycosides and a Coumarin Derivative from Coriaria nepalensis and Their Neurotrophic Activity. Molecules 2016, 21, 1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, M.; Gulkari, V.D.; Wanjari, M.M. Bryophyllum pinnatum leaf extracts preventi formation of renal calculi in lithiatic rats. Anc. Sci. Life 2016, 36, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.G.; Hamal, J.P. Traditional phytotherapy of some medicinal plants used by Tharu and Magar communities of Western Nepal, against dermatological disorders. Sci. World 2013, 11, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattarai, S.; Tamang, R. Medicinal and aromatic plants: A synopsis of Makawanpur district, central Nepal. Int. J. Ind. Herbs Drugs 2017, 2, 6–15. [Google Scholar]

- Grover, J.K.; Yadav, S.P. Pharmacological actions and potential uses of Momordica charantia: A review. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2004, 93, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojewole, J.A.; Adewole, S.O.; Olayiwola, G. Hypoglycaemic and hypotensive effects of Momordica charantia Linn. (Cucurbitaceae) whole plant aqueous extract in the rat. Cardiovasc. J. S. Afr. 2006, 17, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Verma, R.; Balaji, B.S.; Dixit, A. Phytochemical analysis and broad spectrum antimicrobial activity of ethanolic extract of Jasminum mesnyi Hance leaves and its solvent partitioned fractions. Bioinformation 2018, 14, 430–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acharya, K.P.; Rokaya, M.B. Ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants traded in the streets of Kathmandu Valley. Sci. World 2005, 3, 44–48. [Google Scholar]

- Bajracharya, D.M. Phyto-geography of Nepal Himalaya. Tribhuvan Univ. J. 1996, 19, 57–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toffin, G.; Wiart, J. Recherches sur l’Ethnobotanique des Tamang du Massif du Ganesh Himal (Népal central): Les plantes non cultivées. J. Agric. Tradit. Bot. Appl. 1985, 32, 127–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, P. Contribution to the Ethnobotany of the Tamangs of Kathmandu Valley. Contrib. Nepalese Stud. 1988, 15, 247–266. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, L.G. Tamang Shamans. An. Ethnopsychiatric Study of Ecstasy and Healing in Nepal; Nirala Publications: New Delhi, India, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Khatry, P.K. The Nepalese Traditional Concepts of Illness and Treatment. DADA Riv. Antropol. Postoglob. 2011, 1, 45–54. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, J.F. Brahman and Chhetri of Nepal. Encyclopedia of World Cultures. Available online: https://www.encyclopedia.com/humanities/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/brahman-and-chhetri-nepal (accessed on 19 April 2020).

- Tongco, M.D. Purposive Sampling as a Tool for Informant Selection. Ethnobot. Res. Appl. 2007, 5, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WIPO. WIPO Intellectual Property Handbook: Policy, Law and Use, 2nd ed.; WIPO Publication: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- International Society of Ethnobiology. ISE Code of Ethics (with 2008 Additions). Available online: http://ethnobiology.net/code-of-ethics/ (accessed on 30 October 2019).

- Singh, R.K.; Singh, K.P.; Turner, N.J. A special note on Prior Informed Consent (PIC). Why are you asking our gyan (knowledge) and padhati (practice)? Ethics and prior informed consent for research on traditional knowledge systems. Indian J. Tradit. Knowl. 2013, 12, 547–562. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, G.J. Ethnobotany. A Methods Manual; Walter, M., Ed.; Chapman & Hall: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Alexiades, M.N. Selected Guidelines for Ethnobotanical Research: A Field Manual; Alexiades, M.N., Ed.; NYBG Press: Bronx, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, K.K.; Joshi, S.D. Medicinal and Aromatic Plants Used in Nepal, Tibet and Trans-Himalayan Region; AuthorHouse: Bloomington, IN, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Polunin, O.; Stantion, A. Flowers of Himalaya; Oxford University Press: New Delhi, India, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Preparation of Plant Specimens for Deposit as Herbarium Vouchers. Available online: https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/herbarium/voucher.htm (accessed on 28 April 2020).

- Plants of the World Online. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Available online: http://www.plantsoftheworldonline.org/ (accessed on 30 April 2020).

- Trotter, R.T.; Logan, M.H. Informant consensus: A new approach for identifying potentially effective medicinal plants. In Plants in Indigenous Medicine & Diet. Biobehavioral Approaches; Etkin, N.L., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 1986; pp. 91–112. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, S.; Martins, X.; Mitchell, A.; Teshome, A.; Arnason, J.T. Quantitative Ethnobotany of two East Timorese cultures. Econ. Bot. 2006, 60, 347–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade-Cetto, A.; Heinrich, M. From the field to the lab: Useful approaches to selecting species based on local knowledge. Front. Pharmacol. 2011, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tardìo, J.; Pardo-De-Santayana, M. Cultural Importance Indices: A Comparative Analysis Basedon the Useful Wild Plants of Southern Cantabria (Northern Spain). Econ. Bot. 2008, 62, 24–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).