Abstract

This study’s objective was to evaluate the rescued traditional knowledge about the chiricaspi (Brunfelsia grandiflora s.l.), obtained in an isolated Canelo-Kichwa Amazonian community in the Pastaza province (Ecuador). This approach demonstrates well the value of biodiversity conservation in an endangered ecoregion. The authors describe the ancestral practices that remain in force today. They validated them through bibliographic revisions in data megabases, which presented activity and chemical components. The authors also propose possible routes for the development of new bioproducts based on the plant. In silico research about new drug design based on traditional knowledge about this species can produce significant progress in specific areas of childbirth, anesthesiology, and neurology.

Keywords:

activity; bioproduct; Brunfelsia; Amazonian; Ecuador; ethnobotanic; ayahuasca; validation; drug discovery; scopoletin 1. Introduction

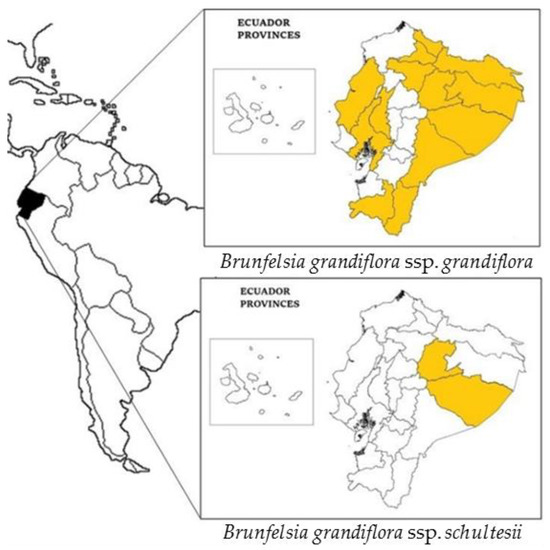

Three species of the genus Brunfelsia (Solanaceae) used as an additive in the hallucinogenic “ayahuasca” drink have traditionally been very important plants for Ecuadorian indigenous Amazonian cultures such as the Kichwa of the East, Tsa’chi, Cofán, Secoya, Siona, Wao, and Shuar [1]. They are Brunfelsia chiricaspi Plowman, Brunfelsia macrocarpa Plowman, and Brunfelsia grandiflora D.Don, including ssp. grandiflora and ssp. schultesii Plowman in the variability range. Ancestral knowledge recognizes different applications or degrees of activity for each taxon. B. grandiflora is the one with the widest distribution area. It is well known as ornamental in Tropical America and is differentiated from its congeners by morphological characters related to floral and foliar size. This paper presents an ethnobotanical review of B. grandiflora ssp. grandiflora and B. grandiflora ssp. schultesii, in order to document its use, to offer arguments for its conservation, and to provide scientific evidence of its activity. The traditional knowledge rescued in a barely contacted Kichwa community in the province of Pastaza (Ecuador) is also presented. The authors describe the ancestral practices that remain in force today. They validated them through bibliographic revisions in data megabases, which presented activity and chemical components. The authors also propose possible routes for the development of new bioproducts based on the plant. In essence, this study’s fundamental objective was to conserve, document, and validate the traditional use of Brunfelsia grandiflora, as an element for innovation.

2. Results

2.1. Brunfelsia grandiflora: Botanical Description, Chorolorogy, Variability, and Names

Brunfelsia grandiflora (see Figure 1) is a small tree that was described by David Don in 1829 from material collected during the Ruiz and Pavon expeditions undertaken in Peru [2]. It has spread from Central America (Nicaragua, Costa Rica, USA) to the north of South America (Colombia, Brazil, Ecuador, Peru and Bolivia). There, it is well-known in cultivation as ornamental, exhibiting some exceptional forms. In the Amazon region, it is also cultivated for its narcotic and medicinal properties. It grows primarily at elevations of 650–2000 m, mainly on the eastern slopes of the Andes, in the region known as the montana (i.e., a humid, montane rainforest) [3].

Figure 1.

Brunfelsia grandiflora ssp. grandiflora in the Pakayaku rainforest, Ecuador. Photo credit: CX. Luzuriaga-Quichimbo (8 February, 2016).

The author of its monograph [3] gave the following detailed description: “Shrubs or small tree 1–6 (10) m tall. Trunk to 7 cm in diameter near base, much branched. Bark thin, roughish, light to dark brown. Branches slender, ascending or spreading, often subvirgate and arching, leafy, glabrous. Branchlets glabrous, rarely pubescent, green. Leaves 10–23 cm long, 3–8 cm wide, glabrous or sparingly pubescent at midrib; petiole 3–12 mm long. Inflorescence terminal and subterminal, simple or branched, dense or lax, the axis 5–45 mm long. Flowers 5-many, showy, scentless, violet fading to white with age, with rounded, white ring at mouth. Bracts 1–3 per flower, 1–5 (10) mm long, lanceolate to ovate, ciliolate, pubescent or glabrate, caducous. Pedicel 2–10 mm long, glabrous or with few sparse glandular hairs, becoming thicker and corky-verrucose in fruit. Calyx 9–13 mm long, tubular-campanulate, somewhat narrowed toward base, globose to obovate in bud, somewhat inflated or not so, glabrous, rarely punctate or sparsely glandular within, smooth or striate-nerved, light yellow-green to gray-green, firmly membranaceous to subcoriaceous, teeth 2–5 mm long, ovate-lanceolate, blunt to short acuminate, erect or incumbent, recurved slightly with age; calyx in fruit persistent, coriaceous, becoming corky-verrucose especially near base, often splitting on one or more sides. Corolla tube 30–40 mm long, 2.5–3.5 mm in diameter, 2.5–3.5 mm in diameter, the mouth 6–9 mm long; limb 35–52 mm in diameter, spreading. Stamens completely included in upper part of corolla tube; filaments thin, upper pair 4 mm long, lower pair 3 mm long, white; anthers 1–1.5 mm long, orbicular-reniform, light brown. Ovary 1.5–2 mm long, sessile, conical to ovoid, pale yellow; style slender, slightly dilated at apex; stigma about 1 mm long, briefly bifid, unequal, the up-per lobe somewhat larger, obtuse, green. Capsule 8–20 mm long, 8–20 mm in diameter, ovoid to subglobose, obtuse or apiculate at apex, smooth, nitid, dark green turning brownish, with corkypunctate or—verrucose outgrowths, pericarp thin, 0.3 mm thick, crustaceous, drying brittle, tardily dehiscent. Seeds 10–20, 5–7 mm long, 2–3 mm in diameter, variable in shape, ellipsoid to oblong, angular, dark reddish brown, reticulate-pitted. Embryo about 4 mm long; slightly curved, cotyledons 1.5 mm long, ovate-elliptic”.

Brunfelsia grandiflora ssp. schultesii Plowman, within the species’ variability and which has been collected [2] in Venezuela, Colombia, Brazil, Bolivia, Peru, and Ecuador (see Figure 2), was described by Plowman in Bot. Mus. Leafl. 23 (6): 259 (1973). It is characterized by its lower altitudinal preferences and smaller dimensions. The aforementioned author [3] described it in detail as follows: “Inflorescence variable, compact or lax. Pedicel 2–6 mm long. Calyx 5–10 mm long, teeth 1–3 mm long, triangular to triangular-ovate. Corolla tube 15–30 mm long, 1–2 mm in diameter, curved toward apex; limb 20–40 mm in diameter, spreading, mouth 3–5 mm long. Capsule 11–16 mm long, 10–16 mm in diameter”.

Figure 2.

Distribution of Brunfelsia grandiflora s.l. in Ecuador.

The species is referenced in Ecuador (see Figure 2) where it is called chiri kaspi, chiri wayusa, chiri wayusa pahu, chiri wayusa panka atu, urku chiri wayusa, wayra panka (Kichwa), uva silvestre (Spanish), i’shan ta’pe, luli ta’pe (Tsafi’ki), tsontimba’cco (A’ingae), jaija’o ujajai (Pai Coca), winemeawe (Wao Tededo), apaj, chirikiasip (Shuar Chicham), paiapia, and simora (unspecified language) [4].

2.2. Compilation of Brunfelsia grandiflora Ethnobotanical Uses

The Kichwa name chiricaspi (which means cold tree) refers to the chills and tingling sensations (”like rain in the ears”) that are felt after ingesting the bark. It is widely employed as a hallucinogen, often added to intensify the effect of narcotic drinks. Indigenous groups throughout the northwest Amazon use this plant to treat fever, rheumatism, and arthritis. It is said to act as a tonic over time, giving one strength and resistance to colds [3]. Ethnobotanical uses have been reported from different countries, for example, Bolivia [5], Brazil [6], Venezuela [7,8], Colombia [5,8,9], and Peru [8,10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. In Peru, the use of remedies based on this plant is traditionally associated with diet (refrain from eating pepper, i.e., ají, Capsicum frutescens), meat, and sexual relations [10,11]. Old thick roots are considered toxic, so only 2–3 roots approximately 1–1.5 cm diameter should be used [12]. Macerated roots are employed to combat rheumatism and syphilis. The leaves are also used to treat colds, arthritis, and snake bites. The bark is utilized against leishmaniasis. It is boiled to obtain a thick liquid that is applied to the affected areas [10,11,17]. In Colombia, both subspecies are commonly known as borrachero [3,9,12]. They are used in that country as an antirheumatic as well. Roots and, less frequently, the leaves are an admixture of ayahuasca. Prepared alone, this plant is used only when the shaman is faced with a particularly difficult or persistent problem, because the toxicity is known by local population. The most common preparation is making a tea from the roots and the bark. Cold water extraction can also be carried out, by shaving the bark from the roots and stems and then allowing them to soak. Alcohol mixture extractions have also been described [7,8]. In the Yabarana tribe (Venezuela), the leaves are routinely dried, crushed, mixed with tobacco and smoked [7,8].

Presented below (see Table 1) is a synthesis of the ethnobotanical knowledge about Brunfelsia grandiflora ssp. grandiflora and B. grandiflora ssp. schultesii, obtained from the indigenous communities of Ecuador based in bibliographic revisions [4,18] and our field prospections (see Table 2). Both subspecies seem to be used interchangeably in folk medicine, but ssp. schultesii is more widespread in the lowlands and is the form more likely to be employed.

Table 1.

Synthesis of the ethnobotanical knowledge about Brunfelsia grandiflora ssp. grandiflora D. Don and B. grandiflora ssp. schultesii Plowman * from the indigenous communities of Ecuador.

Table 2.

Specific medical and cultural uses of B. grandiflora ssp. grandiflora and B. grandiflora ssp. schultesii * in Pakayaku (Pastaza, Ecuador).

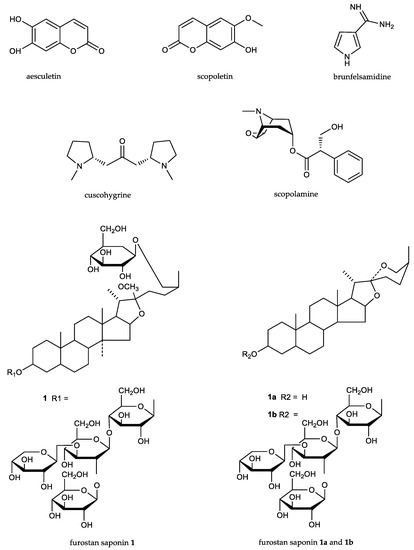

2.3. Towards a Validation of the Pharmacological Action of B. grandiflora

The most important compounds found [5,7,12,19,20] in the leaves, stems, roots, and root bark are presented in Figure 3: coumarins, as aesculetin and scopoletin; a metilendiamine, as brunfelsamidine; unidentified alcaloids, as manacine and manaceine; tropanic alcaloids, as scopolamine; pirrolidinic alcaloids, as cuscohygrine; and steroidic saponins belonging to the furostan saponins type.

Figure 3.

Chemical structures of the principal components of Brunfelsia grandiflora s.l.

2.4. Experimental Studies on Activity

The principal evidence elements related to the physiological and pharmacological activities demonstrated by the experimental work carried out in the laboratory were selected and are summarized in Table 3. This table refers only to the activity of molecules that are contained in the species B. grandiflora. These activities have been tested and published in literature. The references that appear in the last column belong to the team author of the corresponding research for each case.

Table 3.

Biological activity of some chemical compounds present in Brunfelsia grandiflora.

3. Discussion

Brunfelsia grandiflora is an interesting neotropical plant with worthy arguments for its conservation. It is locally cultivated as an ornamental decoration, as a personal decoration during traditional festivals, as an element of construction and even as a singular edible plant. However, its most unique use is cultural, linked to its administration by the local leaders of different ethnic groups. For example, it is used in the Ecuadorian Amazon, among the Cofán, to diagnose diseases or remove evil spirits; among the Shuar, to improve the aim or for inducing vomits; among the Siona to check paternity; among the Kichwa to improve luck during hunting. It has been used as a shamanic beverage in order to obtain knowledge about new medicines to treat diseases. It is ingested in rituals, is a relaxing, hypnotic, or hallucinogenic drug, and it is also prepared in the form of baths, along with orange leaves, caimito, achiote, grapefruit, and onion. As a medicinal plant it is used as an anti-flu medicine, to reduce fever and headache, to treat arthritis and rheumatism, wounds, burns, and even as a contraceptive. The subspecies grandiflora has been collected by botanists in the Bobonaza River basin [33], but the subspecies schultesii has not even been observed in the biggest province of Ecuador, Pastaza. Our survey revealed that the plant grows in the remote forest, where it was perfectly recognized by local inhabitants; it was currently being used and had a good reputation to combat rheumatism, arthritis, body pain, colds, and fever. Our fieldwork also provided three novel uses that had not been reported before: against stomach pain, as a larvicide against tupe, and as an accelerator of childbirth.

The validation of the pharmacological action of B. grandiflora can be supported by interrelating different information published in scientific literature. The anti-inflammatory effect of scopoletin [25,26], fully justifies the abovementioned uses against rheumatism, arthritis, body pain, colds, flu, fever, headache, joint and muscle pain, body blows, and discomfort. It can also explain its use by folk medicine as an anti-snake venom, and in cases of wounds and burns. The hallucinogenic and narcotic properties associated with symbolic cultural rituals clearly depend on the brain and nervous system activities that are mediated by brunfelsamidine [19], cuscohygrine [23], scopolamine [24], and even scopoletin [27,28,29], the last two sometimes exerting opposite effects. With respect to the traditional custom of associating this plant with increasing energy, wisdom, or marksmanship, the authors had to take into consideration the activity currently being studied in the furostan saponines (i.e., about their capacity to induce pro-sexual and androgenic enhancing effects [34]).

There are promising fields for innovation and scientific research in the future about this taxon. The antiproliferative effects of aesculetin [21,22] open the way in the field of oncology; brunfelsamidine and cuscohygrine [19,23], in the fields of anesthesiology and reanimation; and most relevantly, furostan saponins for the treatment of leishmania and other intracellular parasites that produce malaria [32]. The small molecular size of the main components presented in Table 2 make them very good candidates to be tested in the future “in silico” discovery of new drugs. Neurology seems to be one of the most current specialties, and their use in the childbirth process should also be addressed.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Area and Voucher Collection

The Kichwa community of Pakayaku (Bobonaza River, Pastaza, Ecuador) lies in an isolated region where bio- and ethnodiversity studies are still lacking. One of the authors (C.X.L.-Q.) was based in the Biological Station Pindo Mirador in the northern Bobonaza River basin (1° 27′ 09″ S, 78° 04′ 51″ W), and, since 2008, was charge of environmental monitoring and education programs involving the local population.

Plant collection permits were granted by the Ministry of the Environment, following the Convention of Biological Diversity rules [35]. Plant vouchers were deposited at the Herbarium José Alfredo Paredes, Universidad Central de Ecuador, Quito QAP Herbarium as “Ecuador. Pastaza: Sarayaku, Pakayaku, banks of the Bobonaza river, path to the lake by the house belonging to Mr. O. Aranda, 383 m, 01° 39′ 0.4″ S, 077° 35′ 53″ W, lowland evergreen forest, 9 February 2016, C. X. Luzuriaga-Q & E. Gayas sub subsp. Grandiflora: (QAP 93819); and subsp. Schultesii Plowman (QAP 93817).” The identification was revised by C. Cerón.

4.2. Ethnobotanical Survey

Collective written research consent was granted by Mrs. Luzmila Gayas, community president of the Assembly of Pakayaku. Prior oral individual consent was obtained from the persons taking part in the survey. Nagoya Protocol Rules were followed [35]. The investigation consisted of a series of planned house visits and walking routes accompanied by Kichwa interpreters and local inhabitants of Pakayaku. Interviews were semi-structured and included a series of open questions aimed to encourage discussion. All interviews were recorded. Ten knowledgeable elders of the Pakayaku community acted as informants and agreed to reveal their wisdom of the plant. The informants answered freely about several topics, namely the Kichwa common name, the part of the plant used, a description of the use, the harvest season, the storage (if any), the concoction, and the treatment target. After the field wok, the data were inserted into an MS Excel spreadsheet. All recorded uses were referred to standard classifications [4,18]. The data provided by the community (see Table 2) were compared with the existing ethnobotanical literature from Ecuador (see Table 1).

4.3. Scientific Validation

A bibliographic study was performed to provide scientific evidence for the medicinal uses of the plant. PRISMA statement reporting items were considered [36]. This included searching databases, removing duplicates, screening records, defining the eligibility criteria for articles, deciding about accessed and excluded articles, including selected articles, and studying the articles. The databases accessed were: Academic Search Complete, Agricola, Agris, Biosis, CAB Abstracts, Cochrane, Cybertesis, Dialnet, Directory of Open Access Journals, Embase, Espacenet, Google Academics, Google Patents, Medline, PubMed, Science Direct, Scopus, Teseo, and Web of Science by the Institute for Scientific Information (ISI). The selected citations are summarized in Table 3. A critical examination of Table 3 was the basis for the discussion of the results and the presentation of a specific and concrete conclusion.

5. Conclusions

This study presents the case of an Amazonian plant for which the approach adopted demonstrates well the value of biodiversity conservation in an endangered ecoregion. In silico new drug design, based on the traditional knowledge about chiricaspi, can produce significant progress in medical fields, such as neurology and anesthesiology.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.R.-T.; methodology, C.E.C.-M., and C.X.L.-Q.; validation, J.B.-S.; formal analysis, M.H.d.B.; investigation, C.X.L.-Q.; data curation, C.E.C.-M. and C.X.L.-Q.; writing and original draft preparation, T.R.-T.; writing, review and editing, J.B.-S.; visualization, M.H.d.B.; supervision, C.X.L.-Q.; project administration, T.R.-T.; funding acquisition, C.X.L.-Q. and T.R.-T.

Funding

This research was partially funded by the Government of Extremadura (Spain) and the European Union through the action “Apoyos a los Planes de Actuación de los Grupos de Investigación Catalogados de la Junta de Extremadura: FEDER GR15080”.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to the members of the Kichwa community of Pakayaku, Luzmila Gayas, the People’s Assembly of Pakayaku, and the collaborating ayllus (families), for their cooperation during the field work, and to the anonymous Referee for the evaluation of our paper and for the constructive critics. M.V. Gil Alvarez (Organic Chemistry Department, University of Extremadura) assisted us with the chemical drawing software.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The founding sponsors had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, and in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Bennett, B.C. Hallucinogenic Plants of the Shuar and Related Indigenous Groups in Amazonian Ecuador and Peru. Brittonia 1992, 44, 483–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Missouri Botanical Garden. Available online: www.tropicos.org (accessed on 25 June 2018).

- Plowman, T. Brunfelsia in Ethnomedicine. Bot. Mus. Lealf. Harv. Univ. 1977, 25, 289–320. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- De la Torre, L.; Navarrete, H.; Muriel, P.; Marcia, M.; Balslev, H. Enciclopedia De Plantas Utiles Del Ecuador; Herbario QCA & Herbario AAU: Quito, Ecuador, 2008; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Nordegren, T. The A-Z Encyclopedia of Alcohol and Drug Abuse; Brown Walker Press: Parkland, FL, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- León, B.; Wiersema, J.H. World Economic Plants: A Standard Reference, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gilman, E.F. Brunfelsia Grandiflora Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow. FPS77. Available online: http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pdffiles/FP/FP07700.pdf (accessed on 23 May 2018).

- Schultes, R.E.; Hofmann, A.; Rätsch, C. Plants of the Gods. Their Sacred, Healing and Hallucinogenic Powers; Healing Arts Press: Rochester, VT, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Pratt, C. An Encyclopedia of Shamanism, Volume 1; Rosen Publishing Group: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Santiváñez Acosta, R.; Cabrera Meléndez, J. Catálogo Florístico de Las Plantas Medicinales Peruanas; Ministerio de Salud, Instituto Nacional de Salud: Lima, Perú, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mejía, K.; Reginfo, E. Plantas Medicinales de Uso Popular En La Amazonía Peruana; Agencia Española de Cooperación Internacional & Instituto de Investigaciones de la Amazonía Peruana: Lima, Perú, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Voogelbreinder, S. Garden of Eden: The Shamanic Use of Psychoactive Flora and Fauna, and the Study of Consciousness; 2009. Available online: http://docshare01.docshare.tips/files/27747/277478962.pdf (accessed on 23 May 2018).

- Jauregui, X.; Clavo, Z.M.; Jovel, E.M.; Pardo-De-Santayana, M. “Plantas Con Madre”: Plants That Teach and Guide in the Shamanic Initiation Process in the East-Central Peruvian Amazon. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011, 134, 739–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kvist, L.P.; Christensen, S.B.; Rasmussen, H.B.; Mejia, K.; Gonzalez, A. Identification and Evaluation of Peruvian Plants Used to Treat Malaria and Leishmaniasis. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2006, 106, 390–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kloucek, P.; Polesny, Z.; Svobodova, B.; Vlkova, E.; Kokoska, L. Antibacterial Screening of Some Peruvian Medicinal Plants Used in Callería District. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2005, 99, 309–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polesna, L.; Polesny, Z.; Clavo, M.Z.; Hansson, A.; Kokoska, L. Ethnopharmacological Inventory of Plants Used in Coronel Portillo Province of Ucayali Department, Peru. Pharm. Biol. 2011, 49, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reginfo, E.; Cerruti, S.; Pinedo, P.M. Plantas Medicinales de La Amazonía Peruana: Estudio de su uso y cultivo; Instituto de Investigaciones de la Amazonía Peruana: Iquitos, Perú, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Luzuriaga-Quichimbo, C.X. Estudio Etnobotánico En Comunidades Kichwas Amazónicas de Pastaza (Ecuador). Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Extremadura, Badajoz, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd, H.A.; Fales, H.M.; Goldman, M.E.; Jerina, D.M.; Plowman, T.; Schultes, R.E. Brunfelsamidine: A Novel Convulsant from the Medicinal Plant Brunfelsia Grandiflora. Tetrahedron Lett. 1985, 26, 2623–2624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kress, H. Brunfelsia Grandiflora. Available online: https://www.henriettes-herb.com/eclectic/kings/franciscea.html (accessed on 23 May 2018).

- Rubio, V.; García-Pérez, A.I.; Herráez, A.; Tejedor, M.C.; Diez, J.C. Esculetin Modulates Cytotoxicity Induced by Oxidants in NB4 Human Leukemia Cells. Exp. Toxicol. Pathol. 2017, 69, 700–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, J.; Zhang, W.; Feng, X.; Shao, M.; Xing, C. Aesculetin (6,7-Dihydroxycoumarin) Exhibits Potent and Selective Antitumor Activity in Human Acute Myeloid Leukemia Cells (THP-1) via Induction of Mitochondrial Mediated Apoptosis and Cancer Cell Migration Inhibition. J. BUON 2017, 22, 1563–1569. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Minina, S.A.; Astakhova, T.A.; Gromova, E.G.; Vaichageva, Y.V. Preparation and Pharmacological Study of Cuscohygrine bis(methyl benzenesulfonate). Pharm. Chem. J. 1977, 11, 478–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DrugBank. Scopolamine. Available online: http://www.drugbank.ca/drugs/DB00747 (accessed on 23 May 2018).

- Kim, H.J.; Jang, S.I.; Kim, Y.J.; Chung, H.T.; Yun, Y.G.; Kang, T.H.; Jeong, O.S.; Kim, Y.C. Scopoletin Suppresses Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines and PGE2 from LPS-Stimulated Cell Line, RAW 264.7 Cells. Fitoterapia 2004, 75, 261–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moon, P.D.; Lee, B.H.; Jeong, H.J.; An, H.J.; Park, S.J.; Kim, H.R.; Ko, S.G.; Um, J.Y.; Hong, S.H.; Kim, H.M. Use of Scopoletin to Inhibit the Production of Inflammatory Cytokines through Inhibition of the IκB/NF-ΚB Signal Cascade in the Human Mast Cell Line HMC-1. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2007, 555, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, E.J.; Romero, M.A.; Silva, M.S.; Silva, B.A.; Medeiros, I.A. Intracellular Calcium Mobilization as a Target for the Spasmolytic Action of Scopoletin. Planta Med. 2001, 67, 605–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rollinger, J.M.; Hornick, A.; Langer, T.; Stuppner, H.; Prast, H. Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitory Activity of Scopolin and Scopoletin Discovered by Virtual Screening of Natural Products. J. Med. Chem. 2004, 47, 6248–6254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carpinella, M.C.; Ferrayoli, C.G.; Palacios, S.M. Antifungal Synergistic Effect of Scopoletin, a Hydroxycoumarin Isolated from Melia Azedarach L. Fruits. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 2922–2927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, R.Y.; Ham, J.R.; Lee, H.I.; Cho, H.W.; Choi, M.S.; Park, S.K.; Lee, J.; Kim, M.J.; Seo, K.I.; Lee, M.K. Scopoletin Supplementation Ameliorates Steatosis and Inflammation in Diabetic Mice. Phyther. Res. 2017, 31, 1795–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kayser, O.; Kolodziej, H. Antibacterial Activity of Extracts and Constituents of Pelargonium Sidoides and Pelargonium Reniforme. Planta Med. 1997, 63, 508–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuchino, H.; Sekita, S.; Mori, K.; Kawahara, N.; Satake, M.; Kiuchi, F. A New Leishmanicidal Saponin from Brunfelsia Grandiflora. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2008, 56, 93–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borgtoft, H.; Fjeldså, J.; Øllgaard, B. People and Biodiversity: Two Case Studies from the Andean Foothills of Ecuador. Centre for Research on Cultural and Biological Diversity of Andean Rainforests. DIVA Tech. Rep. 1998, 3, 1–190. [Google Scholar]

- Neychev, V.; Mitev, V. Pro-Sexual and Androgen Enhancing Effects of Tribulus Terrestris L.: Fact or Fiction. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 179, 345–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations. Convention on Biological Diversity. Available online: https://www.cbd.int/convention/. (accessed on 23 May 2018).

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. BMJ 2009, 339, b2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).