Abstract

The Croton genus includes a diverse group of plants with remarkable potential in natural products research, particularly due to their bioactive compounds with hypoglycemic and phytochemical significance. This study examines Croton guatemalensis Lotsy, focusing on its chemical composition and its biological efficacy as a glucose-6-phosphatase inhibitor. Phytochemical analysis led to the isolation and structural elucidation of eleven compounds (1–11), including three new ent−clerodane diterpenes, designated crotoguatenoic acids C (9), D (10), and E (11). The absolute configurations of compounds 9–11 were determined by electronic circular dichroism (ECD) as (5R,8R,9R,10S)-configured ent–clerodanes. High-performance liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (HPLC–MS/MS) revealed 25 peaks tentatively assigned to terpenoids, flavonoids, and alkaloids, highlighting the species’ chemical diversity. In vitro assays using ethanol–water extract (EWE) and isolated compounds with rat liver microsomes demonstrated inhibitory activity against glucose-6-phosphatase (G6Pase), particularly among ent–clerodane diterpenes (73–96%), with EWE and compounds 1, 4, and 11 showing the highest inhibition. Molecular docking analysis revealed strong interactions between these diterpenoids and the G6PC1 binding pocket, with binding energies comparable to chlorogenic acid (positive control). These findings position C. guatemalensis as a valuable source of bioactive diterpenoids and support the potential of ent-clerodane derivatives as natural G6Pase inhibitors for hyperglycemia management.

1. Introduction

The genus Croton (Euphorbiaceae), comprising over 1200 species distributed throughout tropical and subtropical regions, is well known for its diverse phytochemical profile. This includes diterpenoids, triterpenoids, alkaloids, flavonoids, and other phenolic compounds. Numerous pharmacological activities have been attributed to these metabolites, notably anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, cytotoxic, and hypoglycemic effects [1,2]. Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2D) remains a growing global health concern. Approximately 589 million adults (20–79 years) worldwide are estimated to live with diabetes, of which 43% (≈252 million) remain undiagnosed [3]. Projections estimate that the global number of diabetes cases will reach 853 million by 2050, with over 81% occurring in low- and middle-income countries. In 2024 alone, diabetes accounted for approximately 3.4 million deaths worldwide and imposed healthcare costs exceeding one trillion USD [3]. As the prevalence of type 2 diabetes continues to rise in regions where traditional medicine remains deeply rooted, the therapeutic use of medicinal plants has become an increasingly important component of diabetes management. These trends have spurred significant interest in plant-based therapeutics, especially those from traditional medicine, recognized as a rich source of structurally diverse and biologically active compounds [4].

Croton guatemalensis Lotsy, a small tree native to Central America and southern Mexico, is traditionally used to treat gastrointestinal disorders, skin infections, and diabetes [5,6]. Despite these ethnomedicinal uses, our group exclusively performed a comprehensive chemical analysis of the bark’s ethanol–water extract (EWE) [7], which led to the isolation of five ent–clerodane diterpenoids, including two novel structures (crotoguatenoic acids A and B) and three flavonoids (rutin, epicatechin, and quercetin). These compounds were fully characterized by NMR, ECD, and MS techniques, and affinity-directed fractionation revealed ent–clerodanes as α–glucosidase inhibitors. Given its traditional use as a hypoglycemic remedy by the Cakchiquel community in Guatemala and supported by prior in vivo studies showing its acute glucose-lowering effect [5], our research group performed mechanistic studies to elucidate the bioactivity of EWE and its primary constituent, junceic acid (1).

In a previous study, we explored possible mechanisms of action that could explain the hypoglycemic effect of C. guatemalensis extract and junceic acid. We demonstrated that, following administration of the extract and the compound in both fasting and postprandial states, insulin levels decreased in healthy and hyperglycemic rats despite reduced blood glucose concentrations in both metabolic states, suggesting a potential insulin-sensitizing effect. However, neither the compound nor the extract enhanced insulin action in insulin tolerance tests nor inhibited the activity of protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B, a negative regulator of the insulin signaling pathway. We also demonstrated that the extract and junceic acid inhibited the activity of two rate-limiting enzymes involved in hepatic glucose production. Compared with chlorogenic acid, junceic acid exerted a more potent inhibitory effect on glucose-6-phosphatase, which is commonly used as a positive control. We conclude that this species can modulate hyperglycemia primarily by reducing hepatic glucose production, specifically through inhibition of the rate-limiting enzyme G6Pase, while exerting a non-insulin-dependent sensitizing effect [8].

Building upon our previous findings, which identified junceic acid (1) as a novel clerodane–type diterpenoid with hypoglycemic activity via inhibition of G6Pase, we extended our investigation of the EWE from C. guatemalensis to isolate and characterize additional structurally related compounds that could also inhibit G6Pase. This targeted phytochemical approach led to the discovery and structural elucidation of three previously unreported ent–clerodane diterpenoids, providing an opportunity to evaluate their potential as G6Pase inhibitors. Concurrently, we conducted an untargeted HPLC–ESI–QTOF–MS/MS profiling of the extract, which revealed a diverse chemical composition including diterpenoids, alkaloids, and flavonoids. The isolated diterpenes were subsequently evaluated in vitro for their inhibitory activity against G6Pase, a key regulatory enzyme in gluconeogenesis and a validated therapeutic target for type 2 diabetes [9,10]. Remarkably, all three ent–clerodane diterpenoids exhibited inhibitory activity against G6Pase, underscoring the pharmacological relevance of this structural class within C. guatemalensis. To the best of our knowledge, this study represents the first to integrate comprehensive metabolomic profiling with G6Pase inhibitory evaluation in this species, thereby reinforcing its chemotaxonomic significance within the genus and highlighting its potential as a source of novel ent–clerodane-based scaffolds for hypoglycemic drug development.

2. Results and Discussion

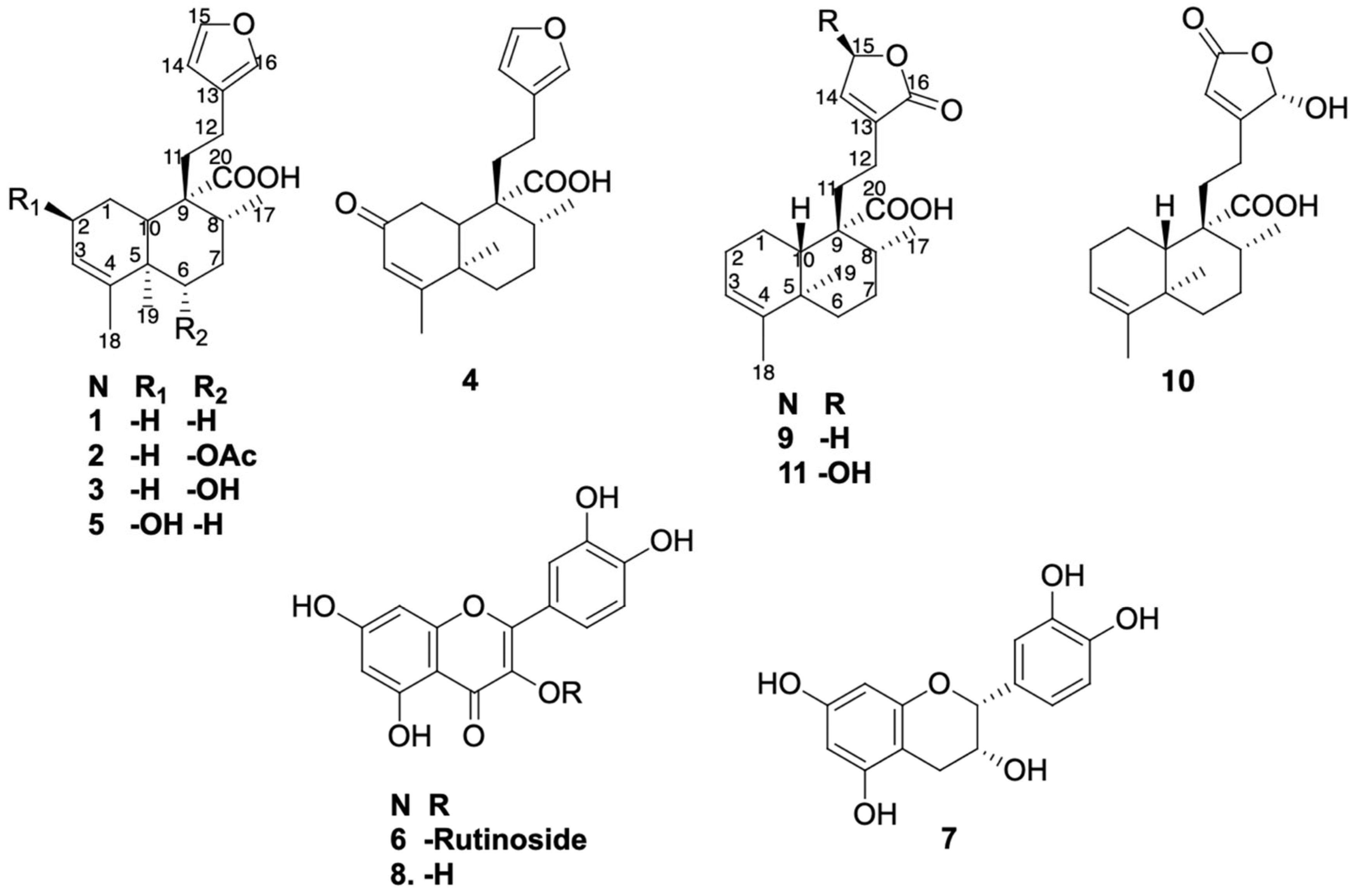

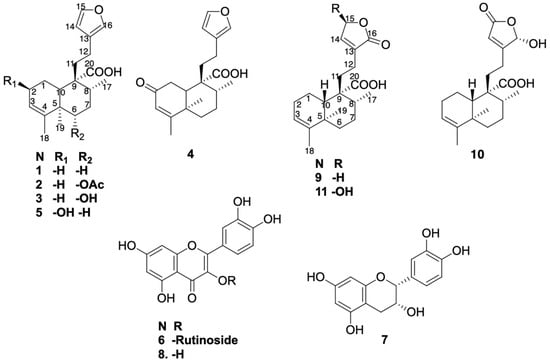

The isolated compounds (Figure 1) from the EWE of C. guatemalensis—eight ent–clerodane diterpenes (1–5, 9–11) and three flavonoids (6–8)—were evaluated in vitro for their inhibitory activity against G6Pase, a key enzyme in hepatic glucose production. Junceic acid (1) had previously demonstrated in vivo hypoglycemic effects via this mechanism [8].

Figure 1.

Isolated compounds from EWE of C. guatemalensis.

2.1. Structure Elucidation

A combination of 1H and 13C NMR spectral data (COSY, HSQC, HMBC, NOESY, TOCSY), high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS), and electronic circular dichroism experiments (ECDs) revealed the structures of three previously unreported compounds.

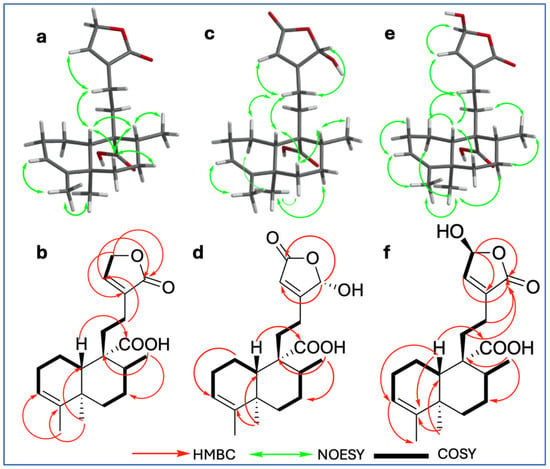

Compound 9 was isolated as a white powder with a melting point of 100–101 °C. Its molecular formula, C20H28O4, was established based on NMR spectroscopic data and confirmed by ESI-MS (HRESIMS) ion at m/z 331.19288 [M − H]− (calcd. for C20H27O4, 331.19148), indicating seven degrees of unsaturation (Figures S1–S10). The IR spectrum (Figure S2) showed characteristic absorption bands for hydroxyl groups (broad band at 3387 cm−1), conjugated carbonyls (1745 cm−1 for a carboxylic acid and 1692 cm−1 for an ester), and olefinic functionalities (1448, 1406, 1375, and 1347 cm−1). The 1H, 13C, and DEPT NMR spectra (Table 1; Supplementary Data, Figures S3–S5) revealed a 20-carbon framework comprising three methyls, seven methylenes, two methines, two vinylic, and six quaternary carbons. The combined analysis of 1H and 13C data (Table 1, Figures S3 and S4), along with HSQC (Figure S6) and COSY (Figure S7) correlations, indicated the presence of a clerodane–type diterpenoid skeleton. The three methyl groups were identified as part of the core clerodane structure, with signals observed at δC/H 17.8/0.95 (s; C/H-19), 16.8/1.12 (d, J = 6.88 Hz; C/H-17), and 18.2/1.57 (q; J = 1.80 Hz C/H-18); COSY correlations between δH 4.78 (H-15) and 7.14 (H-14), along with HMBC correlations (Figure S8) from H-15 with δC 134.4 (C-13), 144.1 (C-14), and 174.0 (C-16), as well as from H-14 to δC 70.4 (C-15), 134.4 (C-13), and 174.3 (C-16), supported the presence of an α,β-unsaturated γ–lactone ring as a side chain moiety. A broad singlet at δH 5.23 (H-3) and its corresponding carbon signal at δC 121.3, along with δC 143.5 (C-4), indicated a trisubstituted double bond with no substitution at C-18. The carboxyl signal at δC 181.7 showed HMBC correlations with δH 1.61 (m, H-10) and δH 1.52 (m, H-8), confirming its location at C-20. The TOCSY (Figure S9) enables the unequivocal assignment of proton positions within the decalin system; thus, H-3 (δH 5.23) was found to be spin-coupled with δH 1.57 (H-18), 1.70 (m, H-1α), 1.90 (m, H-1β), and 2.00 (m, H-2α and H-2β), confirming its position within the A ring. Additionally, the proton at δH 1.52 (m, H-8) showed correlation with interaction with δH 1.19 (dd, H-6α), 1.78 (m, H-6β), 1.44 (dd, H-7β), 2.13 (dd, H-7α), and 1.61 (m, H-10), confirming its location within the B ring of the decalin system. The relative configuration of 9 was determined by NOESY spectroscopy (Figure S10). Key NOESY correlations (Figure 2a) were observed between H-6β (m, δH 1.78) and both H-10 (m, δH 1.61) and H-8 (m, δH 1.52), supporting their beta orientation; simultaneously, H-10 with H-12 (m, δH 2.23) and H-19 (s, δH 0.95) with H-7α (dd, δH 2.13), indicating a trans–cis–type configuration of the clerodane skeleton, which is characteristic of most of these diterpenes [11]. This configuration is consistent with the ent–clerodane structures previously reported by our group [7], although compound 9 shows distinct differences in the side chain.

Table 1.

1H and 13C NMR spectroscopy data of compounds 9, 10, and 11 (δ in ppm, J in Hz).

Table 1.

1H and 13C NMR spectroscopy data of compounds 9, 10, and 11 (δ in ppm, J in Hz).

| 9 a | 10 a | 11 a | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | δH | δC | δH | δC | δH | δC |

| 1 | α 1.70, m β 1.90 b, m | 20.4 | α 1.73, qd (12.21, 5.82) β 1.83 b, m | 20.4 | α 1.70, m β 1.88 b, m | 20.4 |

| 2 | α 2.00 b, m β 2.00 b, m | 27.1 | α 1.95 b, m β 1.95 b, m | 27.4 | α 2.03 b, m β 2.03 b, m | 27.3 |

| 3 | 5.23, br s | 121.3 | 5.25, br s | 121.1 | 5.24, br s | 121.2 |

| 4 | - | 143.5 | - | 143.5 | - | 143.5 |

| 5 | - | 38.9 | - | 38.9 | - | 38.9 |

| 6 | α 1.19, dd (4.35, 13.35) β 1.78, m | 37.5 | α 1.20, dd (14.61, 5.16) β 1.82, m | 37.4 | α 1.21 b, m β 1.79 b, m | 37.5 |

| 7 | α 2.13, dd (13.01, 3.15) β 1.44, dd (13.75, 3.57) | 27.5 | α 2.11 b, m β 1.45 b, m | 27.3 | α 2.03 b, m β 1.45 b, m | 27.4 |

| 8 | 1.52 b, m | 37.3 | 1.50, m | 37.3 | 1.54 b, m | 37.2 |

| 9 | - | 49.9 | - | 49.8 | - | 49.9 |

| 10 | 1.61 b, m | 48.4 | 1.56 b, m | 48.5 | 1.59 b, m | 48.5 |

| 11 | α 1.89 b, m β 2.23 b, m | 31.5 | α 1.91 b, m β 2.27 b, m | 30.5 | α 1.88 b, m β 2.22 b, m | 31.2 |

| 12 | 2.23 b,c, m | 18.9 | 2.35 b,c, m | 21.1 | 2.03 b,c, m | 21.2 |

| 13 | - | 134.4 | - | 168.6 | - | 138.1 |

| 14 | 7.14, t (1.68) | 144.1 | 5.90, br s | 117.3 | 6.89, d (1.53) | 143.4 |

| 15 | 4.78, d (1.89) | 70.4 | - | 170.7 | 6.10, s | 97.0 |

| 16 | - | 174.0 | 6.03, br s | 98.7 | - | 171.7 |

| 17 | 1.12, d (6.88) | 16.8 | 1.13, d (6.79) | 16.7 | 1.12, d (6.85) | 16.7 |

| 18 | 1.57, q (1.80) | 18.2 | 1.59, br s | 18.2 | 1.56, br s | 18.2 |

| 19 | 0.95, s | 17.8 | 0.96, s | 17.7 | 0.94, s | 17.7 |

| 20 | - | 181.7 | - | 180.5 | - | 181.2 |

a Data recorded at 400 MHz (1H) and 150 MHz (13C) in CDCl3. b Overlapped signals. c Signals for two protons.

Figure 2.

Key NOESY correlations of compounds 9 (a), 10 (c), and 11 (e); key HMBC (H—C) correlations of compounds 9 (b), 10 (d), and 11 (f); 1H-1H COSY correlations of compounds 9 (b), 10 (d), and 11 (f).

Figure 2.

Key NOESY correlations of compounds 9 (a), 10 (c), and 11 (e); key HMBC (H—C) correlations of compounds 9 (b), 10 (d), and 11 (f); 1H-1H COSY correlations of compounds 9 (b), 10 (d), and 11 (f).

Compound 10 (C20H28O5) exhibited a close structural similarity to compound 9 (Table 1; Figures S11–S20), with the most notable difference being in the downfield shift observed in the chemical shifts corresponding to the side chain (C-13–C-16), which appeared downfield. Specifically, 13C and 1H NMR spectra showed a carbonyl at δC 170.7 (C-15) and a proton signal shifted downfield at δH 6.03 (br s, H-16) due to a hydroxyl at the position C-16, in contrast to the methine and carbonyl group arrangement found in compound 9. The position of the carbonyl at C-15 and the hydroxyl group at C-16 was confirmed by the HMBC spectrum (Figure S18), which showed key correlations between H-14 (br s, δH 5.90) and C-13 (δC 168.6), C-15 (δC 170.7), and C-16 (δC 98.7). Additionally, H-16 (br s, δH 6.03) exhibited HMBC correlations with both C-13 and C-15, further supporting the proposed structural arrangement. The relative configuration at C-10 (δC 48.5) of compound 10 was determined by analysis of the NOESY spectrum (Figure S20); key NOESY correlations (Figure 2c) were observed between H-10 (m, δH 1.56) and both H-6β (m, δH 1.82) and H-12 (m, δH 2.35); simultaneously, correlations between H-19 (s, δH 0.98) with H-1α [δH 1.73, dd, J = qd (12.21, 5.82)] as well as H-7α (m, δH 2.11), supported a trans–cis–type clerodane skeleton configuration similar to compound 9.

Compound 11 (C20H28O5) exhibited the same spectroscopic characteristics as 9 (Figures S21–S30). The only significant difference was observed in the downfield chemical shifts of C/H-15 (δC 97.0/δH 6.10, s), indicating the presence of a hydroxyl substituent at C-15. The relative configuration of 11 (Figure 2e) by NOESY NMR spectrum showed some key interactions between H-10 (m, δH 1.59) with H-6β (m, δH 1.79) and H-1β (m, δH 1.88); simultaneously, correlations between H-19 (s, δH 0.94) with H-1α (m, δH 1.70) as well as H-7α (m, δH 2.03) supported a trans–cis–type clerodane skeleton configuration similar to compounds 9 and 10.

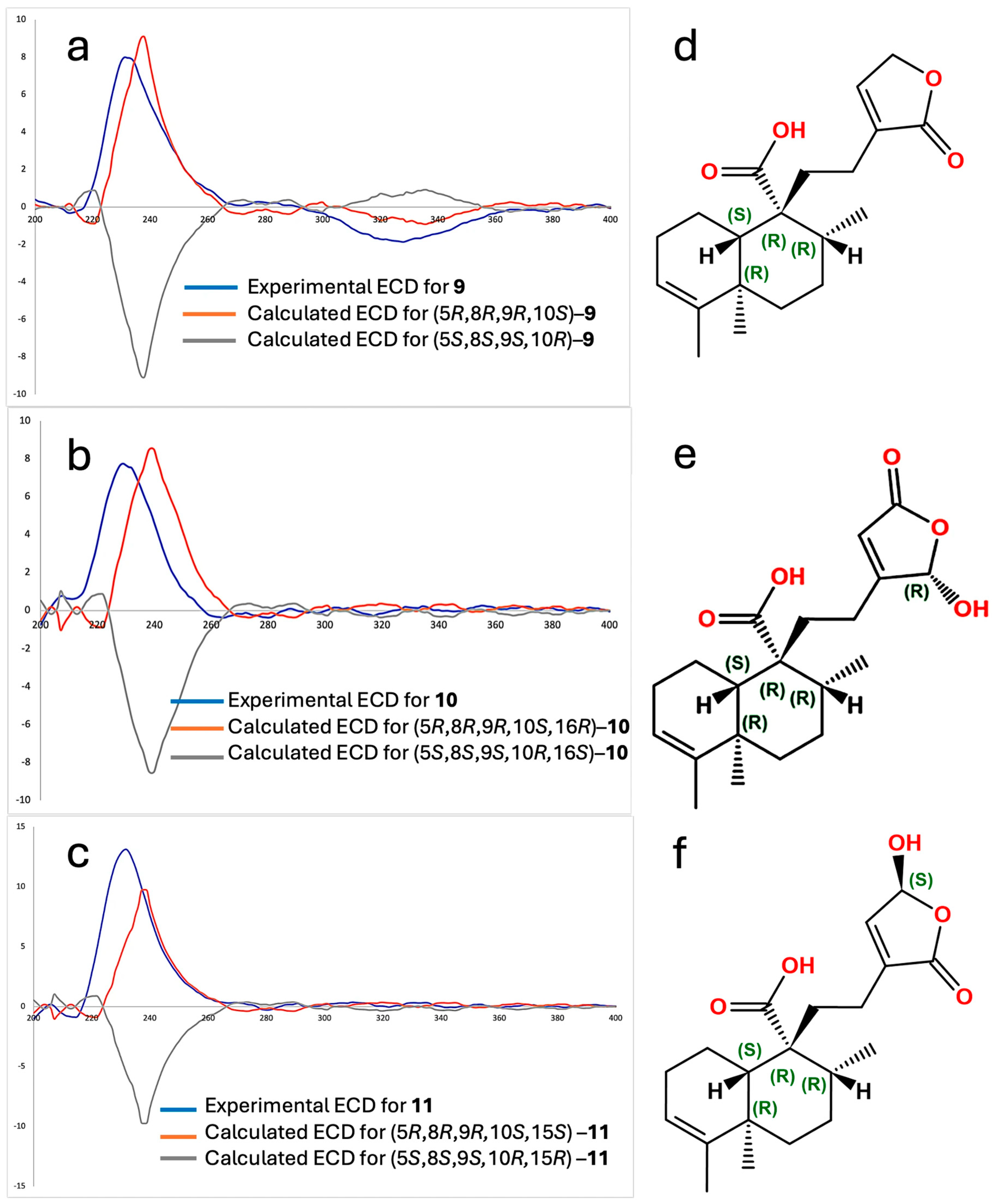

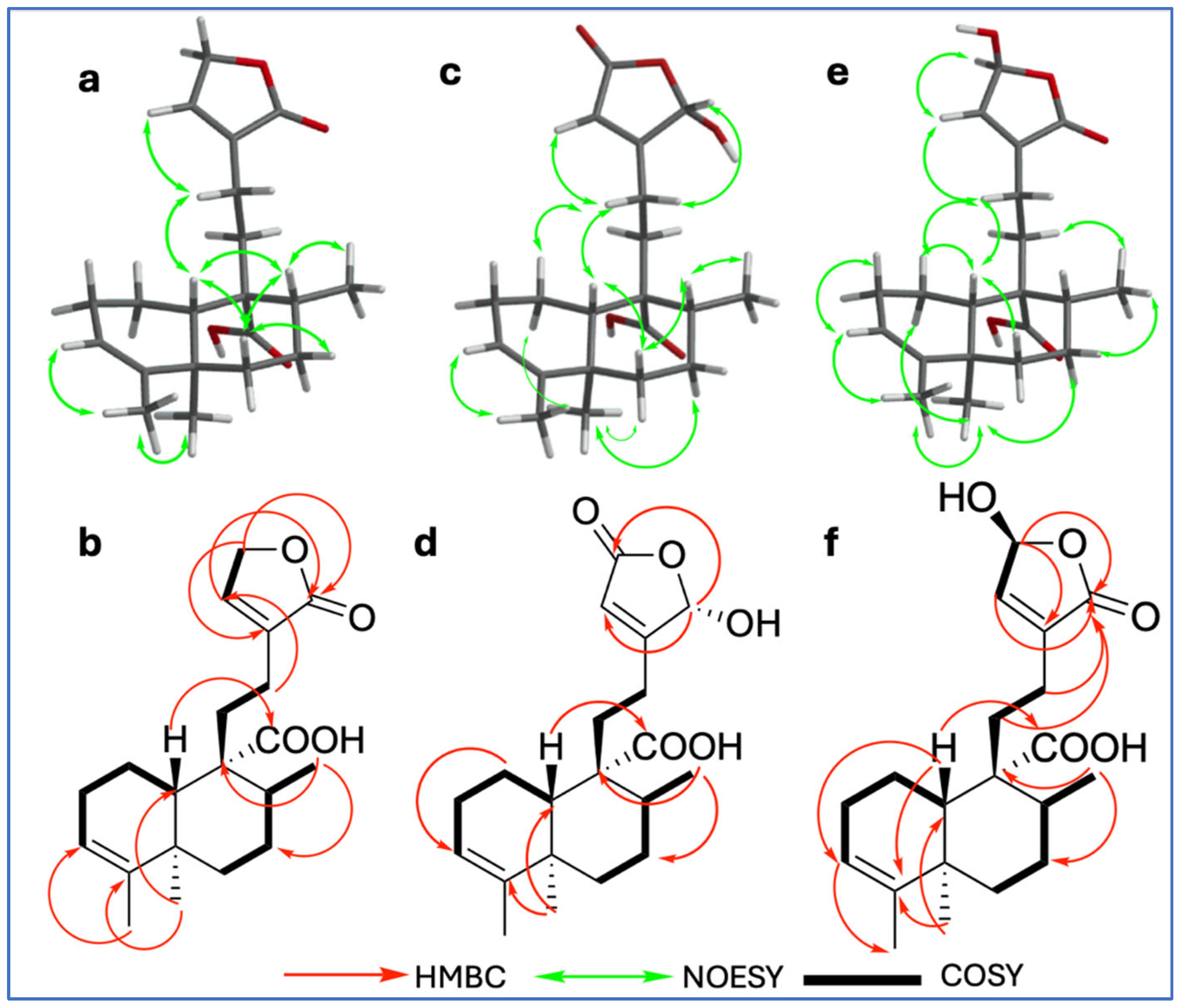

Specific rotation measurements and comparisons between experimental and calculated electronic circular dichroism (ECD) spectra for the ent–isomer were developed to establish the absolute configuration of compounds 9, 10, and 11 (Figure 3). The specific rotations were [α]20D = −48, [α]20D = −34, and [α]20D = −36 for 9, 10, and 11, respectively, showing all negative and of similar magnitude, suggesting a shared stereochemical framework with 9. The experimental ECD spectra of compound 9 (blue line, Figure 3a), 10 (blue line, Figure 3b), and 11 (blue line, Figure 3c) exhibited Cotton effects that aligned well with those calculated for the ent–isomer (orange lines in Figure 2a and Figure 2c, respectively). Compounds 9–11 demonstrated positive Cotton Effects at 231 nm (Δε = +7.99), 232 nm (Δε = +13.10), and 229 nm (Δε = +7.75) and negative Cotton Effects at 328 nm (Δε = −1.87), 200 nm (Δε = −1.40), and 200 nm (Δε = −0.75), respectively. These spectral features closely matched the theoretical ECD profiles calculated for the (5R,8R,9R,10S) configuration. Therefore, the absolute configurations were confirmed as follows: (5R,8R,9R,10S)–ent–cleroda–3,13–dien–16,15–olide–20–oic acid (Figure 3d) for compound 9; (5R,8R,9R,10S)–16–hydroxy–ent–cleroda–3,13-dien–15,16–olide–20–oic acid (Figure 3e) for compound 10; and (5R,8R,9R,10S)–15–hydroxy–ent–cleroda–3,13–dien–16,15–olide–20–oic acid (Figure 3f) for compound 11. Interestingly, the enantiomers of these structures were previously reported from the liverwort Heteroscyphus coalitus [12], where the isolated compounds showed positive optical rotation and mirror-image ECD spectra in comparison to compounds 9–11. This confirms that the terpenoids isolated from C. guatemalensis are the opposite enantiomers of those previously described and further supports the ent–prefix assignment in their nomenclature. Following the naming convention of previously reported ent–clerodane diterpenes from C. guatemalensis, such as crotoguatenoic acids A (2) and B (3), these compounds have been designated as crotoguatenoic acids C, D, and E for compounds 9, 10, and 11, respectively.

Figure 3.

Experimental electronic circular dichroism (ECD) spectra for compounds 9 (a), 10 (b), and 11 (c), along with computed calculated CD spectra. Absolute configuration of the crotoguatenoic acids C (d), d (f) and g (e).

The clerodane diterpenes, identified in various plant species, are known to stereospecifically interact with biological targets, thereby influencing diverse biological activities. Most of them were evaluated as anti-cancer, anti-inflammatory, and antimicrobial [13]. The presence of opposite enantiomers in C. guatemalensi and H. coalitus suggests the potential for each to be exploited against different biological targets. While the ent–neo–clerodanes from H. coalitus have shown antifungal activity against Candida albicans [12], the ent–clerodanes isolated from C. guatemalensis may act through a distinct mechanism aligned with their traditional use. It would be valuable to evaluate both types of compounds in the same biological assays to expand our understanding and support the development of previously unreported phytopharmaceuticals. The difference in stereochemistry of these chemical profiles strongly suggests that these plants may have unique biological activities, emphasizing the importance of enantioselective isolation and characterization in natural product chemistry [14].

2.2. Qualitative Phytochemical Screening Profile of C. guatemalensis by HPLC–ESI–QTOF–MS/MS

The HPLC–ESI–QTOF–MS/MS profiles (Figure S34), utilizing the EWE in both positive and negative ionization modes (Table 2), were specifically developed to enhance the phytochemical characterization of C. guatemalensis. A total of 25 peaks were detected and tentatively identified as terpenes, flavonoids, alkaloids, and sucrose.

Table 2.

Compounds tentatively identified from EWE by HPLC-ESI-QTOF-MS/MS.

At the early retention times of the HPLC–ESI–QTOF–MS/MS profile (2–19 min), protonated molecules corresponding to typical flavonoid molecular formulas were observed, including derivatives of epigallocatechin, rutin, and isorhamnetin, often in glycosylated forms.

Flavanols are efficiently ionized in HPLC–ESI–QTOF–MS/MS and can be observed in both positive and negative ionization modes, depending on analytical objectives and the specific molecular structure. In positive ion mode, especially when using an acidic mobile phase, flavanols typically form protonated molecular ions [M + H]+ [18].

Several peaks observed at retention times of 2.72, 6.72, 6.95, and 9.40 min were tentatively assigned as flavan–3–ols. For example, the compound eluting at 6.72 min showed a deprotonated molecule at m/z 593.12832 [M − H]− and a fragment ion at m/z 305.06658, consistent with the loss of a gallocatechin moiety (C15H13O6, 289.0712 Da). Similarly, the peaks at 2.72, 6.95, and 9.40 min showed the same fragmentation pattern, suggesting the similar functional groups [19]. These eluates exhibited typical procyanidin fragmentation patterns, including a characteristic fragment ion at m/z 139, which arises from C-ring cleavage through the 1,3-bond. This fragmentation behavior is consistent with the absence of substitution at the 3-position of the flavonoid skeleton and supports the presence of a flavanone [20]. In Table 2, the common fragmentation patterns of these flavanones can be observed.

Flavonols eluting at 12.3 and 18.7 min, with molecular formulas C27H30O16 and C16H12O7, showed protonated molecules at m/z 611.16333 [M + H]+ and 317.05280 [M + H]+, respectively. Positive ions at m/z 303.0362 and 303.0326 correspond to the loss of a rutinosyl moiety (C12H20O9) and a methyl group (CH3), respectively. These data are consistent with the presence of rutin (6) at 12.3 min and isorhamnetin at 18.7 min [18,21].

Isoquinoline alkaloids typically contain a basic nitrogen atom in their core structure, which readily undergoes protonation in solution and generates intense [M + H]+ signals [22]. Consequently, positive molecular ions of alkaloids were observed. Peaks at 5.35 and 5.90 min displayed protonated molecular ions at m/z 342.17248 [M + H]+ and 342.17277 [M + H]+, respectively, consistent with the molecular formula C20H23NO4. The MS/MS fragmentation patterns of both peaks matched those previously reported for isoquinoline alkaloids isolated from this genus [23]. The most informative product ions were [M + H − 17]+ or [M + H − 31]+, depending on whether the amino group is present as –NH2 or N-methylated (–N-CH3), reflecting neutral losses that are characteristic of aporphine-type alkaloids [24]. In this context, the peak at 5.35 min generated a fragment at m/z 293.10304 [M + H]+, indicative of a neutral loss of an N-methyl group, followed by loss of a hydroxyl substituent. Additionally, the overall fragmentation behavior closely resembled that of alkaloids such as isocorydine, previously identified in the genus Croton, suggesting that the alkaloid core skeleton is analogous to these known ones.

These isoquinoline alkaloids have been previously isolated from the ethanolic extract of Croton linearis [23] as well as from chloroform and dichloromethane extracts of Croton hemiargyreus, C. echinocarpa, C. rivinifolius [25], and Croton lechleri [26]. Corydine and some derivatives have been evaluated as G protein-biased full agonists of the opioid receptor (MOR), producing analgesic effects in a mouse model of visceral pain with minimal side effects. These properties make them very important in plants since they contribute to defense mechanisms and offer pharmacologically relevant scaffolds for drug development [27]. Nevertheless, corydine lacks in vivo or in vitro studies as hypoglycemic agents. However, isocorydine and some isoquinolin alkaloids were reported with hypoglycemic activity acting through inhibition of glucose uptake in intestinal membrane vesicles and reduced glucose absorption and blood glucose levels in vivo [28]. This information opens an interest in the isolation of these compounds from C. guatemalensis for their structural characterization and for their future studies as hypoglycemic agents.

The most prominent isolated constituents are terpenes bearing a clerodane-type skeleton. Based on this background, and considering that clerodane diterpenes are commonly found within the genus [29], we proposed molecular formulas for the remaining unidentified peaks. Fifteen peaks were classified as diterpenes. Compounds of this nature began eluting at 19.4 min and continued up to 33.4 min. Some of them (at 21.4, 25.5, 25.9, 27.1, 27.9, 28.3, 29.6, and 33.4 min) were identified by comparing their retention times and mass spectra with those of previously isolated compounds (1–5, 9, 10, and 11). Other peaks presented similar molecular formulas to those of isolated compounds. For example, the peak at 17.7 min, with negative ion at m/z 347.18694 [M − H]−, exhibited the same molecular formula as crotoguatenoic acids D and E (C20H28O5). On the other hand, peaks at 18.5, 19.4, 21.0, 24.6, and 30.0 min, detected as positive or negative ions at 379.17493 [M − H]−, 365.19766 [M + H]+, 347.18789 [M + H]+, 389.19891 [M + H]+, and 393.22698 [M + H]+, respectively, exhibited fragmentation patterns similar to those of known clerodane diterpenes. In particular, the peak at 30.0 min showed fragment ions at m/z 315, 145, 133, 131, 119, and 117, closely matching the fragmentation behavior reported for crotoguatenoic acid B, which supports a similar structural nature. Taken together, these data and the corresponding molecular formulas are consistent with a clerodane diterpene skeleton bearing different substituents, such as methyl or hydroxyl groups. Based on these observations, we propose that these peaks also correspond to clerodane diterpenes, similar to those previously isolated. In this context, C. guatemalensis suggests a complex chemical profile consisting of diterpenes and flavonoids. The presence of diterpenes and flavonoids draws a parallel with the phytochemical profile reported for other species in the genus, such as C. lechleri and C. heliotropiifolius [2]. Reinforcing the chemotaxonomic significance of these metabolite classes in Croton.

2.3. Evaluation of Inhibition of Glucose-6-phosphatase (G6pase)

EWE and all the isolated compounds were tested for G6Pase inhibition, using CA as a positive control. Table 3 presents the inhibition percentages in descending order, along with their respective IC50 (µg/mL). All the ent–clerodane diterpenes and EWE inhibited the enzyme (73–96%). Crotoguatenoic acid E (11) exhibited the highest activity, achieving 96% inhibition, closely approaching the 99% inhibition of the positive control, CA. Junceic acid (1) and crotoguatenoic acids C (9) and D (10) were the other compounds that demonstrated at least 80% inhibition of G6Pase enzymatic activity. In contrast, rutin (6) showed weak inhibition and reduced enzymatic activity by only 37% (Table 3). Therefore, the three isolated flavonoids are unlikely to be responsible for the EWE activity. The clerodanes displayed similar inhibition (Figure S36). Based on their IC50 values (Table 3), the clerodanes’ activity decreased in the following order: formosin F (4), junceic acid (1), crotoguatenoic acid B (3), E (11), A (2), D (10), C (9), and bartsiifolic acid (5), with corresponding IC50 values of 484.3 ± 97.1, 579 ± 91.9, 655.3 ± 53.2, 772.3 ± 80.3, 828.5 ± 16.5, 943.3 ± 161.9, 1081.3 ± 202.9, and 1275 ± 257.3 µg/mL, respectively. This increase or decrease demonstrates the importance of a functional group present or absent in the structure; for example, compound 4 displayed a similar IC50 to CA, even better than 1, and these only structurally differ by a carbonyl in the C-2 position. Conversely, compound 5, which has a hydroxyl at the C-2 position instead of a carbonyl, exhibited the lowest activity among all tested clerodane diterpenes. This suggests that the carbonyl group, particularly its α,β-unsaturation, is crucial for enhancing enzyme affinity, possibly by acting as a Michael acceptor and complexing with nucleophilic protein residues at either the catalytic site or allosterically. These are biologically active molecules with low levels of toxicity [30,31]. Like compound 5, compound 3 also undergoes hydroxylation at the C-6 position; however, unlike compound 5, it demonstrates greater activity, comparable to that of junceic acid (1). There is much evidence of increased inhibitory activity of clerodane diterpenes in different targets related to the presence of a hydroxyl at the C-6 position, but this activity is diminished when this hydroxyl is replaced by an acetyl or methoxyl [11,13,32], which coincides for this assay in the case of compound 2, which exhibits lower activity, possibly due to some steric hindrance. The furan ring represents another significant functional group in these structures, appearing to be more influential than the presence of a γ-lactone, as observed in compounds 9, 10, and 11. The orientation of the furan ring influences activity; specifically, compound 11, with the γ-lactone carbonyl at C-16, shows greater activity compared to compound 10, which has the carbonyl at C-15. Ultimately, the EWE exhibited the best IC50 value, surpassing even that of CA. Given the inhibitory activity demonstrated by all ent–clerodanes, they likely complement one another, which could result in a synergistic effect [33]. These findings are in agreement with prior in vivo studies demonstrating that both EWE and junceic acid (1) exert hypoglycemic effects by suppressing hepatic glucose output, specifically via inhibition of the rate-limiting enzyme G6Pase [8]. Collectively, these data reinforce the pharmacological rationale for the traditional use of C. guatemalensis in diabetes management.

Table 3.

Inhibition of G6Pase by EWE and isolated compounds.

G6Pase is a key enzyme in the final step of both gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis. It catalyzes the conversion of glucose–6–phosphate to free glucose and is an essential process for maintaining blood glucose levels, especially during fasting [10]. Since G6Pase enzymatic activity is elevated in patients with T2D compared to healthy individuals [34], inhibiting or reducing this activity can help manage hyperglycemia associated with the disease. Crotoguatenoic acids (A to E), formosin F (4), and bartsiifolic acid (5) have shown promise in inhibiting G6Pase. Therefore, these structures serve as promising models for treating T2D by reducing hepatic glucose production.

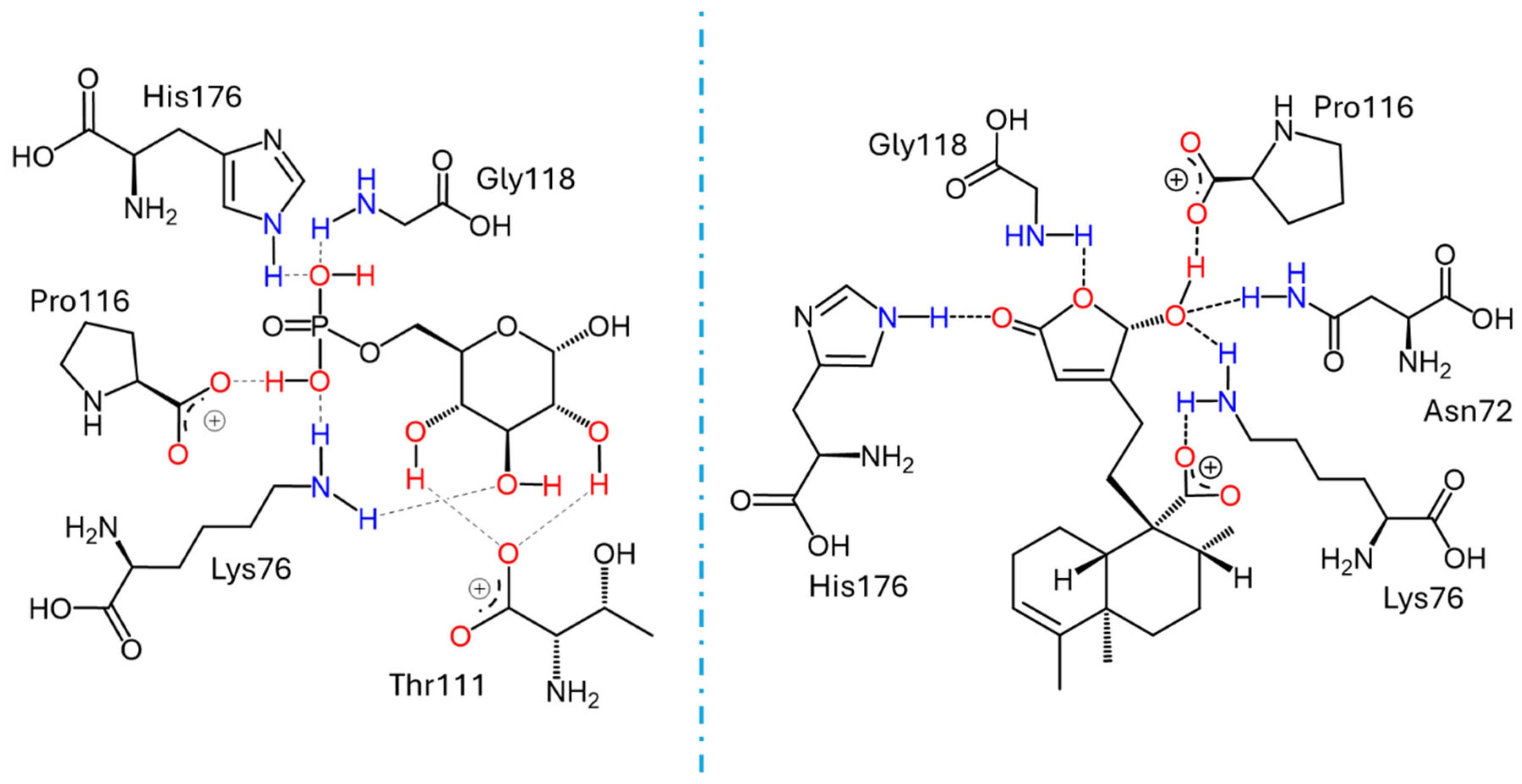

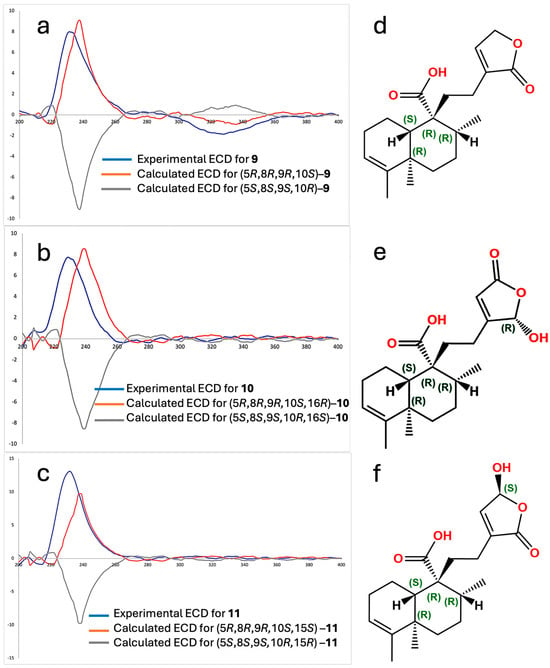

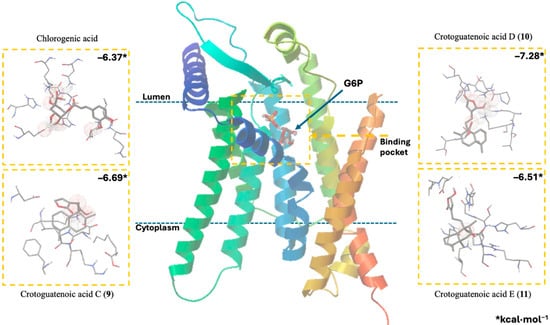

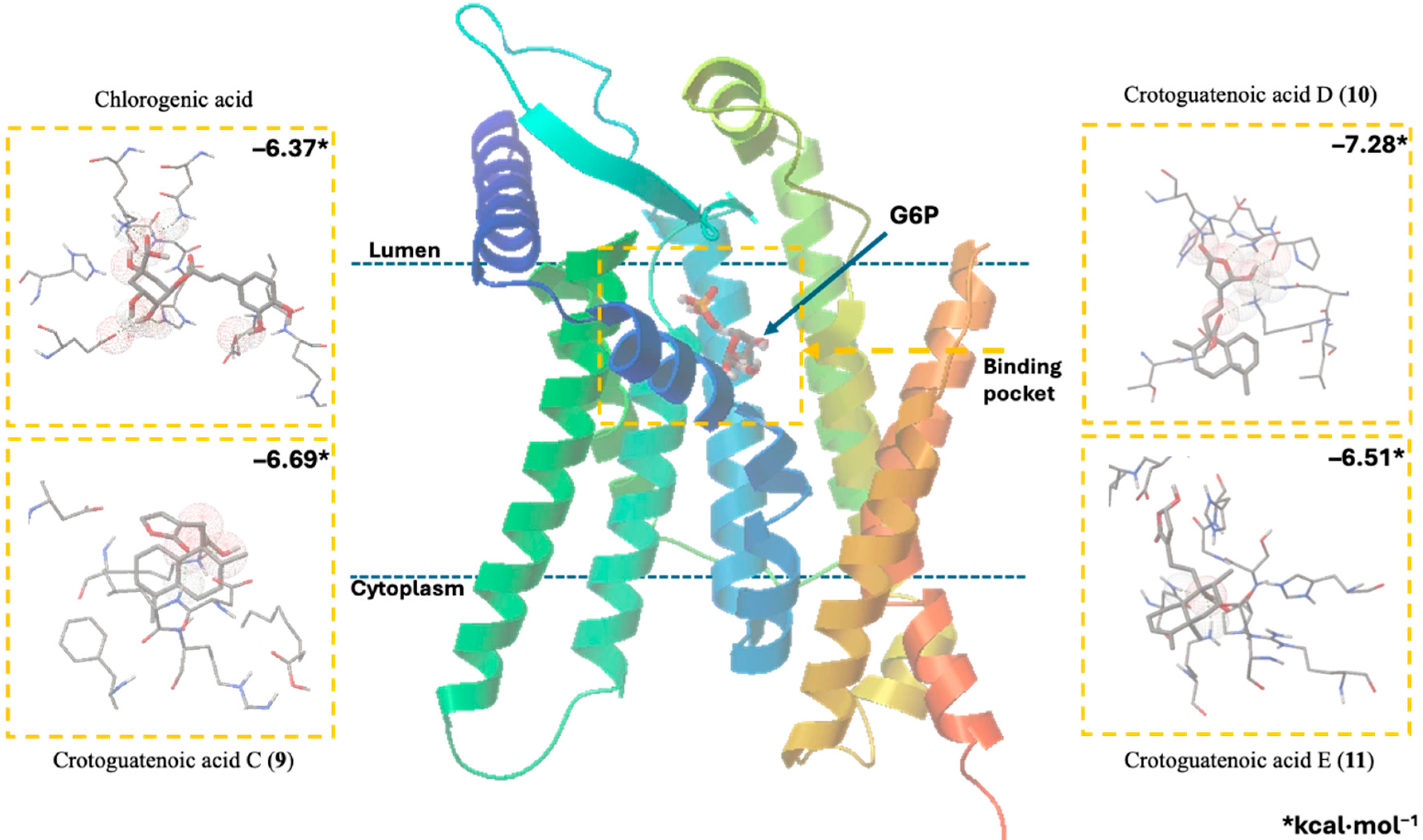

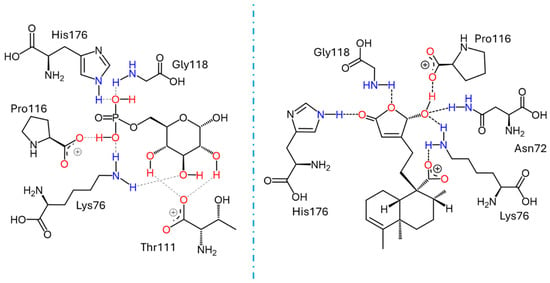

2.4. Molecular Docking

Docking studies were conducted to elucidate the interaction of the compounds within the pocket of the human G6PC1 crystal structure (9J7V.PDB), which served as the molecular modeling template [35]. To test the adapted protocol with G6PC1 templates [35,36], ligand–receptor molecular models were also calculated for CA (positive control) and glucose-6-phosphate (G6P). G6P interacts with the amino acid His176, which is the most important residue in the catalytic pocket of the analyzed enzyme (Figure 4, Table 4) [35]. It forms hydrogen bonds between the amino acid residues Lys76 (1.714 and 1.771 Å), Thr111 (1.663 and 1.881 Å), Pro116 (2.07 Å), Gly118 (2.196 Å), and His176 (1.905 Å). CA fits better than G6P (Figure 4, Table 4), forming hydrogen bond interactions between the amino acid residues Asp38 (1.73 Å), Asn72 (2.133 Å), Lys76 (1.849 Å), Glu110 (2.16 and 1.913 Å), Gly118 (2.156 Å), and His176 (2.044 Å).

Table 4.

G6PC1 theoretical inhibition of diterpenoid selected for docking study.

Figure 4.

Docking results using the structural model of the ligand–receptor molecular model for human G6PC1 (9J7V.PDB) with G6P, CA, and compounds 9 to 11.

Figure 4.

Docking results using the structural model of the ligand–receptor molecular model for human G6PC1 (9J7V.PDB) with G6P, CA, and compounds 9 to 11.

The ligand–receptor calculations for the ent–clerodane diterpenoids 1–5 and 9–11 were well-fitted in the catalytic pocket of the analyzed enzyme (Figure 4, Table 4). Compound 1 showed hydrogen bonding interactions between the amino acid residues Leu39 (2.174 Å), Asn72 (1.945 Å), Lys76 (1.839 Å), and Gly118 (2.207 Å). Compound 2 showed hydrogen bonding interactions between the amino acid residues Lys76 (2.176 Å), Thr111 (2.043 Å), and Ser260 (1.902 Å). Compound 3 showed hydrogen bonding interactions between the amino acid residues Lys76 (1.868 Å) and His176 (2.016 Å). Compound 4 showed hydrogen bonding interactions between the amino acid residues Lys76 (1.933 Å), Thr111 (1.774 Å), Gly118 (2.057), and His176 (2.158 Å). Compound 5 showed hydrogen bonding interactions between the amino acid residues Val107 (2.075 Å), Arg170 (1.957 Å), and His252 (1.951 Å). Compound 9 showed hydrogen bonding interactions between the amino acid residues Leu39 (2.108 Å) and Lys263 (2.121 Å). Compound 10 showed hydrogen bonding interactions with the amino acid residues Asn72 (2.219 Å), Lys76 (1.85 and 1.893 Å), Pro116 (2.15 Å), Gly118 (2.075 Å), and His176 (1.881 Å). Similarly, compound 11 showed hydrogen bonding interactions with the amino acid residues Asn72 (2.181 Å) and Lys76 (1.839 Å).

Recent studies that provided information on the structure, substrate recognition, and catalytic mechanism of G6Pase [35] enable molecular recognition studies to be conducted with this enzyme complex [36]. These studies help suggest the possible mechanism of action of these hypoglycemic agents as G6Pase inhibitors, as well as the structural requirements for the biological activity of these bioactive metabolites. G6Pase comprises nine transmembrane helices and possesses a large catalytic pocket facing the lumen [35]. Docking studies allowed us to observe how diterpenes cause steric hindrance by interacting with the amino acid residue His176, which is a crucial part of G6P recognition [35].

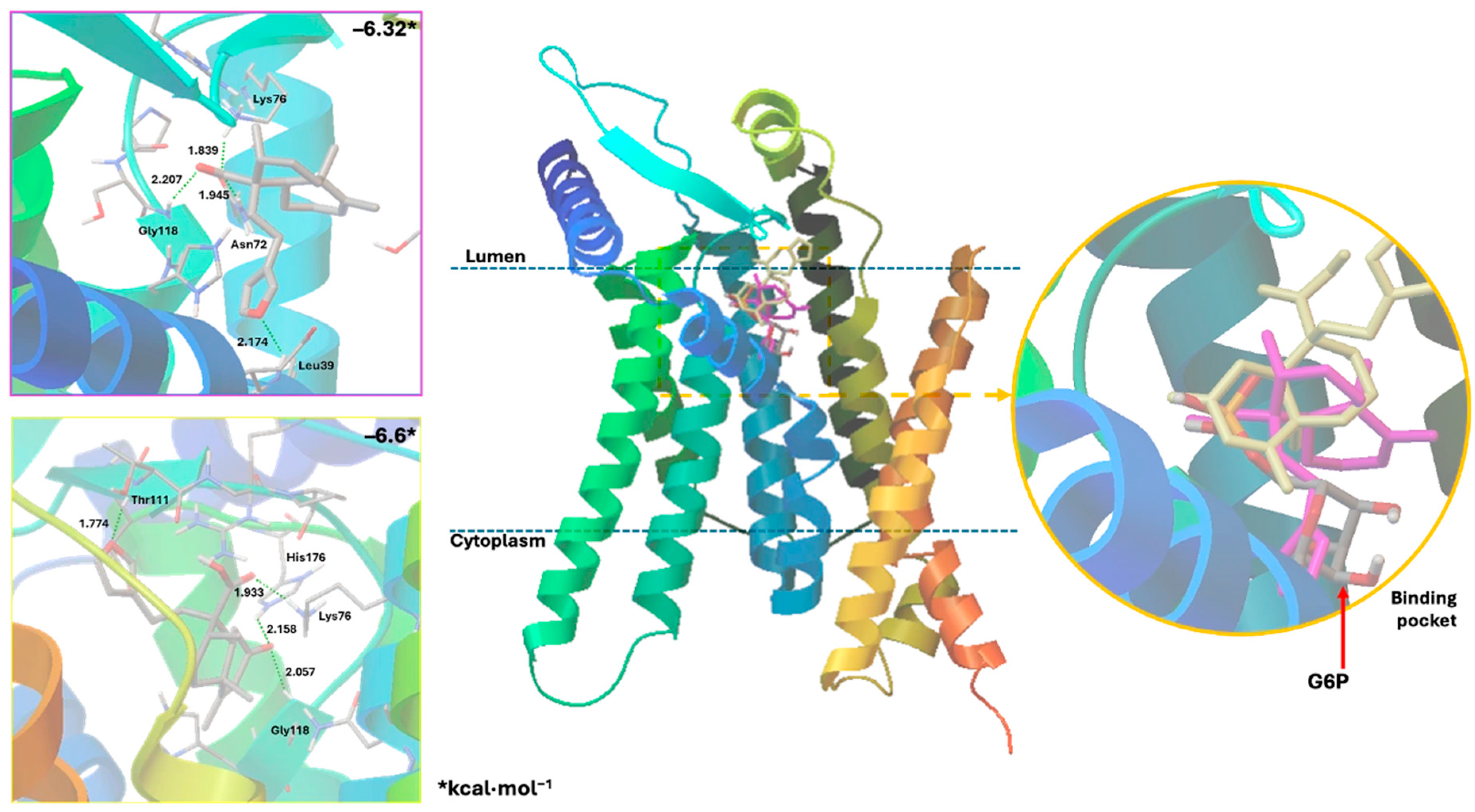

These results suggest that crotoguatenoic acid D (10) represents the optimal conformation among the ent–clerodane diterpenoids for inhibiting the studied enzyme (Table 4), as evidenced by a lower dissociation constant Ki for G6PC1 (4.64 μM) and a lower binding energy (ΔGbinding = −7.28 kcal/mol). Compound 10 binds to the enzyme’s catalytic site in a specific conformation and orientation that creates a significant steric block at the receptor surface. This steric hindrance effectively prevents access to the catalytic pocket (Figure 5). Interestingly, junceic acid (1) and formosin F (4) exhibited binding energies comparable to CA (Figure 5, Table 4). Junceic acid (1) showed four hydrogen bonds with the residues Leu39 (2.174 Å), Asn72 (1.945 Å), Lys76 (1.839 Å), and Gly118 (2.207 Å), displaying a binding energy (ΔGbinding = −6.32 kcal/mol) and a dissociation constant (Ki = 23.46 mM). In the case of formosin F (4), similar to compound 1, it formed four hydrogen bonds with the residues Lys76 (1.933 Å), Thr111 (1.774 Å), Gly118 (2.057 Å), and His176 (2.158 Å), but with slightly better binding energy (ΔGbinding = −6.6 kcal/mol) and dissociation constant (Ki = 14.42 μM) than the values obtained for 1, CA, and G6P (Figure 6, Table 4) and interacting with the catalytic amino acid His176 [35] with a hydrogen bond. These results were observed both experimentally in the in vitro assay and theoretically in the docking assay (Table 3 and Table 4, Figure 6). Figure 6 shows that, in addition to the furan ring and carboxylic acid functional groups, the α,β-unsaturated carbonyl of 4 could interact with the most important residue, His176. Since 1 does not exhibit this interaction, the earlier hypothesis in Section 2.3 is supported.

Figure 5.

Docking results for the human G6PC1 (9J7V.PDB) structural model, encompassing the catalytic site and the binding interactions for G6P with the residues Lys76, Thr111, Pro116, Gly118, and His176 (left); and for crotoguatenoic acid D (10) with the residues Asn72, Lys76, Pro116, Gly118, and His176 (right).

Figure 6.

Docking results using the structural model of the ligand–receptor molecular model for human G6PC1 (9J7V.PDB) with 1 (pink) and 4 (yellow).

With docking analysis, four very important functional groups were observed in the structures: the carboxylic acid, the furan ring, the α,β-unsaturated carbonyl, and the α,β-unsaturated gamma–lactone. These interact with protein residues through different bond formations between the functional group and the protein. α,β-unsaturated carbonyls are Michael acceptors that can generate covalent bonds with nucleophilic protein residues such as cysteine (Cys), histidine (His), and lysine (Lys) [31]; gamma–lactones form non-covalent bonds such as hydrophobic forces and hydrogen bonds with hydrophobic residues (such as leucine (Leu), isoleucine (Ile), valine (Val), phenylalanine (Phe)) and polar residues (e.g., serine, threonine, tyrosine), in addition to possible interactions with polar side groups or the peptide backbone [37]. Furans can form covalent adducts mainly with lysine (Lys), but also, under certain conditions, with cysteine (Cys) and tyrosine (Tyr) [38]; finally, carboxylic acids interact through hydrogen and salt bonds with basic residues (Lys, Arg) and rarely covalently [39]. These functionalities collectively position ent–clerodanes as promising G6Pase inhibitors.

Driven by the recent interest in clerodanes isolated from Croton species for T2D treatment, there has been an increased evaluation of these structures against different biological targets. For example, fifteen compounds isolated from Croton yunnanensis were tested for their ability to promote glucose uptake in insulin-resistant 3T3-L1 adipocytes, thus acting as insulin sensitizers [40]. In the same way, eighteen clerodanes from Croton mangelong were tested for hypoglycemic activity in insulin-resistant 3T3-L1 adipocytes, and ten of them demonstrated activity. Moreover, mangelonine D demonstrated a significant hypoglycemic effect (30 mg/kg) in a streptozotocin-induced hyperglycemic Sprague–Dawley rat model [41]. Conversely, junceic acid (1) from C. guatemalensis demonstrated a hypoglycemic effect, reducing postprandial insulin levels in healthy and hyperglycemic rats, suggesting an insulin-sensitizing effect [8]. Collectively, these investigations underscore the potential of clerodane diterpenes as promising candidates for diabetes treatment.

3. Conclusions

The phytochemical investigation of C. guatemalensis led to the isolation of several clerodane-type diterpenes, including the novel crotoguatenoic acids C–E (compounds 9–11), whose absolute configurations were confirmed by ECD.

The HPLC–ESI–MS/MS analysis proposed the presence of diterpenes, flavonoids, and alkaloids in C. guatemalensis. Notably, the alkaloids in this species are identified for the first time in this species, highlighting a novel phytochemical component. This finding underscores the need for targeted isolation and characterization of these alkaloids to evaluate their potential as hypoglycemic agents.

In patients with type 2 diabetes, hepatic glucose production is overactive, driven by both gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis. Targeting glucose-6-phosphatase (G6Pase) allows simultaneous modulation of both pathways, thereby reducing hepatic glucose output and improving fasting hyperglycemia.

In vitro biological evaluation of the isolated compounds from C. guatemalensis revealed that the ent–clerodane diterpenes inhibit G6Pase, with inhibition levels reaching up to 96%. Comparative analysis suggests a structure–activity relationship influenced by functional group substitutions at C-15 and C-16 of the clerodane core, as well as variations at C-2 and C-6. Specifically, the presence of an α,β-unsaturated carbonyl group at the C-2 position of the decalin system enhances inhibitory activity, whereas substitution with a hydroxyl group diminishes it. Docking analyses further indicate that a γ–lactone moiety at C-15 and C-16 may confer greater activity than a furan ring at the same positions.

These findings establish C. guatemalensis as a promising natural source of bioactive ent–clerodane diterpenes with potential applications in managing hyperglycemia. Further evaluations and mechanistic studies are essential to validate their therapeutic potential as G6Pase inhibitors.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. General

Analytical and semi-preparative high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) experiments were conducted using an Agilent 1260 Infinity system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). This system includes a G1311B quaternary pump, a G1367E autosampler, and a G1315C diode-array detector (DAD VL+), with data acquisition and processing via ChemStation software (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Analytical separations were achieved using a Luna Omega Polar C18 column (50 × 2.1 mm, 1.6 μm particle size; Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA). For semi-preparative purposes, a Nucleosil C18 column (Macherey-Nagel; 250 × 10 mm, 5 μm) was also employed. Rutin, epicatechin, and quercetin reference compounds (purity ≥ 94% by HPLC) were procured from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Column chromatography was performed using Sephadex LH-20 (Sigma-Aldrich) or silica gel 70–230 mesh (Merck Mexico). Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) was performed on silica gel 60 F254 plates (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany), and spots were visualized using a 10% ceric sulfate solution in sulfuric acid.

A Varian Inova 400 MHz spectrometer (Varian Inova, Palo Alto, CA, USA), operating at 400 MHz for 1H and 150 MHz for 13C nuclei, acquired nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra, including one-dimensional (1H, 13C, DEPT) and two-dimensional (HSQC, HMBC, COSY, NOESY, TOCSY) experiments. Chemical shift values are expressed in parts per million (δ, ppm). High-resolution electrospray ionization mass spectrometry was performed using an Agilent HPLC-ESI-QTOF system (Model G6530BA; Agilent Technologies system, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Additional high-resolution mass spectrometry (HR-MS) data were recorded with a JEOL AccuTOF JMS-T100LC instrument (HR-DART-MS; JEOL USA, Peabody, MA, USA). Electronic circular dichroism (ECD) and Fourier-transform infrared (FT-IR) spectra were measured using a J-1500 spectropolarimeter (JASCO, Oklahoma City, OK, USA) and a Tensor 27 instrument (Bruker Optics), respectively.

4.2. Plant Material and Extracts

Croton guatemalensis was collected in 2019 from the Department of Chimaltenango, Guatemala, by Dr. Carola Cruz, based on prior ethnobotanical research [5]. A specimen was deposited at the Deshidrafarmy-Farmaya Herbarium with the voucher CFEH 1259.

EWE was prepared by extracting 20 g of dried C. guatemalensis material twice using 500 mL of a 1:1 ethanol–water mixture for 4 h each time, resulting in a total extract volume of 1 L. The combined extracts were filtered and concentrated at 40 °C with a Büchi Labortechnik AG rotary vacuum evaporator (Flawil, Switzerland). The aqueous residue was subsequently lyophilized, yielding 4.864 g of dry extract, which was stored at 4 °C for further studies. For the phytochemical study, the same methodology previously reported by our group [7] was applied, using a larger amount of plant material. Dried and ground C. guatemalensis (120.7 g) was extracted with a 1:1 ethanol–water mixture (6 L) over 4 h. The extract was then filtered and sequentially partitioned with dichloromethane (CH2Cl2; 3 × 6 L), followed by ethyl acetate (EtOAc; 3 × 6 L). This process yielded 11.4871 g of CH2Cl2-soluble fraction (DSF), 2.6885 g of EtOAc-soluble fraction (ESF), and 11.5303 g of water-soluble fraction (WSF).

4.3. Compounds Isolation

This study aimed to determine whether structurally related diterpenoids and co-occurring flavonoids contribute to the overall activity of the extract. To obtain additional quantities of the previously isolated compounds from the EWE of C. guatemalensis, the extract was subjected to repeated silica gel column chromatography, following previously reported methodology [7]. As a result, compounds 1–8 were isolated as well as three previously undescribed ent–clerodane diterpenes (9–11) (Figure 1).

DSF (10.6 g) was partitioned onto 378 g of silica gel (70–230 mesh, Merck Mexico) using column chromatography. An eluent system of n–hexane, ethyl acetate (EtOAc), and methanol (MeOH) was used, starting with 100% n–hexane and gradually increasing the polarity with EtOAc and then MeOH. Following TLC analysis of their chromatographic profiles, 133 collections were obtained (each 100 mL). This process led to 37 primary fractions (DSF1-DSF37), respectively. Fractions DSF1 (1.364 g) and DSF4 were obtained as the pure compounds 1 (junceic acid) and 2 (crotoguatenoic acid A), respectively. Preparative TLC of fractions DSF8 (79.0 mg; CH2Cl2:MeOH, 96:4; 1.0 mm), DSF9 (116.4 mg; CH2Cl2:MeOH, 96:4; 1.0 mm), and DSF11 (95.0 mg CHCl3:MeOH, 95:5; 1.0 mm) yielded 15.2 mg of 3 (crotoguatenoic acid B), 25.2 mg of 5 (bartsiifolic acid), 33.5 mg of 4 (formosin F), 36.6 mg of 9, and 22.8 mg of 11. The semi-preparative HPLC separation of 50 mg of DSF10 was conducted using a mixture of 15:85 MeCN:H2O as the mobile phase for 15 min (2.0 mL/min; 240 nm UV-detection) to obtain 15.0 mg of 10 (Rt = 5.5 min) and 16.1 mg of 4 (Rt = 6.4 min).

Using MeOH as the eluent, ESF (2.37 g) was subjected to 100 g of Sephadex LH-20, resulting in 89 subfractions (ESF1–ESF89). They were injected into the HPLC-DAD to obtain the fractions for rutin (6) and epicatechin (7). Conditions of the HPLC profile were performed following the methodology previously developed by our group [7]. Elution was carried out at a flow rate of 0.35 mL/min using solvent A (water with 0.1% formic acid) and solvent B (acetonitrile, MeCN) under the following gradient program: 99:1 (A:B) at 0 min, 80:20 at 14 min, 50:50 from 14 to 26 min, 70:30 from 26 to 34 min, 20:80 from 34 to 35 min, and returning to 99:1 from 35 to 38 min. The column temperature was 35 °C. The UV detection was monitored at 254 and 365 nm. Compound 6 (rutin) was obtained as a pure isolate (49 mg) from fraction ESF25. Fraction ESF14–ESF17 (87 mg) was further purified by semi-preparative HPLC using a Nucleosil C18 column (250 × 10 mm internal diameter, 5 μm; Macherey-Nagel). Elution was performed with a 10:90 mixture of MeCN:H2O (v/v) at a flow rate of 2.0 mL/min over 15 min, with UV detection at 280 nm, affording compound 7 (epicatechin) as a pure compound (25 mg, Rt = 9.0 min).

4.3.1. (5R,8R,9R,10S)-Ent-cleroda-3,13-dien-16,15-olide-20-oic Acid (Crotoguatenoic Acid C; 9)

White powder; [α]20D = −48 (c 0.001 MeOH); UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) 214 (1.937) nm; ECD (MeOH) λmax (Δε) 231 (+7.99), 328 (−1.87); IR νmax 3387 (OH), 1745 (COOH), 1692 (C=O), 1448 (C=C), 1375 (C=C), 1347 (C=C) cm−1; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz), and 13C NMR (CDCl3, 150 MHz), see Table 1; HRESIMS 331.19288 [M − H]− (calcd. for C20H27O4, 331.19148).

4.3.2. (5R,8R,9R,10S)-16-Hydroxy-ent-cleroda-3,13-dien-15,16-olide-20-oic Acid (Crotoguatenoic Acid D; 10)

White powder; [α]20D = −34 (c 0.001 MeOH); ECD (MeOH) (Δε) 232 (+13.10), 200 (−1.40); IR νmax 3380 (OH), 1697 (C=O), 1561 (C=C), 1382 (C=C) cm−1; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) and 13C NMR (CDCl3, 150 MHz), see Table 1; ESI–MS m/z 695.6 [2M − H]−, HRESIMS ion at m/z 349.20157 [M + H]+ (calcd. for C20H29O5, 349.20204).

4.3.3. (5R,8R,9R,10S)-15-Hydroxy-ent-cleroda-3,13-dien-16,15-olide-20-oic Acid (Crotoguatenoic Acid E; 11)

White powder; [α]20D = −36 (c 0.001 MeOH); ECD (MeOH) (Δε) 229 (+7.75), 200 (−0.75); IR νmax 3424 (OH), 1695 (C=O), 1765 (C=O),1453 (C=C), 1381 (C=C) cm−1; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) and 13C NMR (CDCl3, 150 MHz), see Table 1; HRESIMS m/z 347.15660 [M − H]− (calcd. for C20H27O5, 347.18639).

4.4. Instrumental and Chromatographic Conditions for HPLC–QTOF–ESI–MS/MS Analysis

High-resolution mass spectra were acquired using high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry (HPLC–QTOF–ESI–MS/MS) on an Agilent 1260 Infinity LC system equipped with a G6530BA QTOF mass spectrometer (Agilent Technologies, USA). To identify the bioactive constituents present in EWE of C. guatemalensis, the extract and compounds were dissolved in deionized water and methanol, respectively, and 3 μL aliquots were injected into a Poroshell C18 column (5 × 3.0 mm i.d., 2.6 μm particle size) maintained at 35 °C for analysis. Chromatographic separation was performed using a binary gradient elution system with solvent A (acetonitrile) and solvent B (deionized water) at a flow rate of 0.5 mL/min. The gradient program was as follows: 99:1 (A:B) at 0 min, 80:20 at 14 min, 50:50 from 14 to 26 min, 70:30 from 26 to 34 min, and 20:80 from 34 to 35 min. Mass spectrometric conditions included the following optimized parameters: electrospray ionization (ESI) in positive and negative mode, ion spray voltage at 3.5 kV, fragmentor voltage at 80 V, and both drying and sheath gas temperatures at 350 °C. The sheath gas flow rate was set at 10 L/min. Accurate mass measurements were obtained for all protonated molecules.

All detected ions were recorded in high-resolution mode, and molecular formulas were assigned based on the comparison between experimental and calculated exact masses. Retention times observed m/z values, and reference ions were used to annotate the compounds. A comparative analysis of the fragmentation patterns of each peak was carried out against public spectral libraries. Specifically, the observed analyte ions were searched in MassBank (MassBank of mass spectral data, MassBank Consortium, available at https://massbank.eu, accessed on 2 January 2025) and GNPS in order to tentatively annotate the detected features. Previously reported phytochemical profiles of the species and published HPLC-DAD chromatographic data for this plant additionally guided the proposed molecular structures, providing a consistent framework for assigning likely metabolite classes. The identification process was further supported by literature data on previously reported metabolites in related Croton species.

4.5. Computational Details

This process was carried out exactly as previously described by our group [7]. Spartan’14 software generated energy-minimized structures for all ligands via geometry optimization using the semiempirical PM3 method. Resulting conformers were filtered for redundancy and subsequently optimized using B3LYP/DGDZVP density functional theory (DFT) implementation in Gaussian 09 software. At this level, thermochemical parameters, infrared (IR) spectra, and vibrational frequency analyses were also computed. For the major conformers in methanol, TD-SCF calculations were performed using the same functional and basis set along with the default solvent model to obtain theoretical circular dichroism (TCD) spectra. The calculated excitation energies (in nm) and corresponding rotatory strengths (R) in dipole velocity form (Rvel) were used to simulate TCD spectra via the Harada–Nakanishi equation, as implemented in SpecDis version 1.71.

4.6. Evaluation of Inhibition of Glucose-6-phosphatase (G6Pase)

To prepare the G6Pase enzyme, subcellular fractions were isolated from the livers of Wistar rats. Two Wistar rats were fasted for 18 h prior to the procedure. The animals were then anesthetized with pentobarbital (6 mg/100 g body weight, administered intraperitoneally). After anesthesia, the livers were dissected and homogenized in buffer containing 250 mM sucrose, 1 mM EDTA, and 5 mM HEPES (pH 7.4). The homogenate was subjected to differential centrifugation to obtain the desired fractions. The resulting pellets were stored at −40 °C until further use [42]. After resuspending the obtained microsomal fraction in buffer (250 mM sucrose, 40 mM imidazole, pH 7), different concentrations (2 µg/mL to 5.0 mg/mL) of inhibitor samples (CA or compounds) were added to the reaction mixture. The enzymatic reaction was started by adding 80 mM G6Pase and incubating at 20 °C for 20 min. The reaction was stopped by adding a “stop solution”, which consists of 0.42% ammonium molybdate in 1 N H2SO4, 10% SDS, and 10% ascorbic acid. After that, it was incubated at 45 °C for 20 min. Absorbance was measured at 830 nm [43].

4.7. Docking Calculations

Docking was performed using Auto Dock 4.2 software (The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA, USA) with default parameters as previously described [44,45]. Crystal structure resolution of the human wild-type (WT) G6PC1 apo form (9J7V.PDB) was used for docking calculations. The calculations for the energy-minimized form with geometric optimization for all ligands were developed with HyperChem 8. Protein and ligand protonation states were assigned according to AutoDockTools 4.2 defaults at physiological pH. Polar hydrogens were added, non-polar hydrogens were merged into the enzyme structures, and Gasteiger charges were calculated for the molecular models of the analyzed compounds, following the procedure previously described for G6PC1 [35,36]. All file preparations were performed using AutoDockTools 4.2. Surface scanning and refined docking were performed to analyze the binding modes accurately. To refine these results, the best conformations observed for the ligand–receptor molecular models in the preliminary analysis were docked into a smaller area to analyze the binding modes to G6PC1. In the refined docking, the grid map was a 40 × 40 × 40 grid point. The Lamarckian genetic algorithm was applied. During the docking experiment, 100 independent runs per ligand were carried out. Auto Dock 4.2 software was used for obtaining the theoretical inhibition constant (Ki) by the binding energy (∆G) obtained using the formula Ki = exp(∆G/RT), where T is the temperature (298.15 °K) and R is the universal gas constant (1.985 × 10−3 kcal mol−1 K−1).

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/plants15030442/s1, Figure S1: HRESI-MS spectrum of compound 9; Figure S2: IR spectrum of compound 9; Figure S3: 1H-NMR spectrum of compound 9 (400 MHz, CDCl3); Figure S4: 13C-NMR spectrum of compound 9 (125 MHz, CDCl3); Figure S5: DEPT spectrum of compound 9 (135 MHz, CDCl3); Figure S6: HSQC spectrum of compound 9 (400 MHz, CDCl3); Figure S7: COSY spectrum of compound 9 (400 MHz, CDCl3); Figure S8: HMBC spectrum of compound 9 (400 MHz, CDCl3); Figure S9: TOCSY spectrum of compound 9 (400 MHz, CDCl3); Figure S10: NOESY spectrum of compound 9 (400 MHz, CDCl3); Figure S11. HRESI-MS spectrum of compound 10; Figure S12: IR spectrum of compound 10; Figure S13: 1H-NMR spectrum of compound 10 (400 MHz, CDCl3); Figure S14: 13C-NMR spectrum of compound 10 (125 MHz, CDCl3); Figure S15: DEPT spectrum of compound 10 (135 MHz, CDCl3); Figure S16: HSQC spectrum of compound 10 (400 MHz, CDCl3); Figure S17: COSY spectrum of compound 10 (400 MHz, CDCl3); Figure S18: HMBC spectrum of compound 10 (400 MHz, CDCl3); Figure S19: TOCSY spectrum of compound 10 (400 MHz, CDCl3); Figure S20: NOESY spectrum of compound 10 (400 MHz, CDCl3); Figure S21: HRESI-MS spectrum of compound 11; Figure S22: IR spectrum of compound 11; Figure S23: 1H-NMR spectrum of compound 11 (400 MHz, CDCl3); Figure S24: 13C-NMR spectrum of compound 11 (125 MHz, CDCl3); Figure S25: DEPT spectrum of compound 11 (135 MHz, CDCl3); Figure S26: HSQC spectrum of compound 11 (400 MHz, CDCl3); Figure S27: COSY spectrum of compound 11 (400 MHz, CDCl3); Figure S28: HMBC spectrum of compound 11 (400 MHz, CDCl3); Figure S29: TOCSY spectrum of compound 11 (400 MHz, CDCl3); Figure S30: NOESY spectrum of compound 11 (400 MHz, CDCl3); Figure S31: Experimental circular dichroism spectrum of 9; Figure S32: Experimental circular dichroism spectrum of 10; Figure S33: Experimental circular dichroism spectrum of 11; Figure S34: Phytochemical screening profile of C. guatemalensis by HPLC–ESI–Q–TOF–MS/MS in positive and negative modes; Figure S35. MS/MS spectra of the HPLC-MS/MS profile of the ethanol:water extract of C. guatemalensis; Figure S36: Concentration–response inhibition curves of G6Pase.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.M.E.-R. and A.A.-C.; methodology, S.M.E.-R., D.G.R.-R. and G.M.-T.; software, D.G.R.-R.; validation, S.M.E.-R.; formal analysis, S.M.E.-R. and D.G.R.-R.; investigation, S.M.E.-R., A.A.-C., D.G.R.-R. and R.A.-E.; resources, A.A.-C. and R.A.-E.; data curation, S.M.E.-R., D.G.R.-R. and G.M.-T.; writing—original draft preparation, S.M.E.-R., D.G.R.-R. and G.M.-T.; writing—review and editing, A.A.-C., S.M.E.-R. and D.G.R.-R.; visualization, S.M.E.-R. and A.A.-C.; supervision, A.A.-C. and R.A.-E.; project administration, A.A.-C.; funding acquisition, A.A.-C. and R.A.-E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México by the program “Programa de Apoyo a Proyectos de Investigación e Innovación Tecnológica” (UNAM-PAPIIT), by the projects No. IN213222, IN214225, and IN215823.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The protocol was approved by “Comisión de Ética Académica y Responsabilidad Científica (CEARC) Facultad de Ciencias, UNAM.” Protocol Number; PI_09_03_2023_03 (Renovated 2024).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank Elizabeth Huerta Salazar and María de los Ángeles Peña González (Instituto de Química, UNAM) for assistance with NMR spectra recording, Adriana Romo Pérez (Instituto de Química, UNAM) for CD spectra recording, and Everardo Tapia Mendoza (LANCIC—Instituto de Química, UNAM) for assistance with LC-MS/MS recording. D.G.R.-R. thanks SECIHTI for his postdoctoral scholarship (CVU: 205045).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ECD | Electronic circular dichroism |

| HPLC–MS | High-performance liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry |

| CA | Chlorogenic acid |

| G6Pase | glucose-6-phosphatase |

| T2D | Type 2 diabetes |

| HRMS | high-resolution mass spectrometry |

References

- Coy-Barrera, C.A.; Galvis, L.; Rueda, M.J.; Torres-Cortés, S.A. The Croton Genera (Euphorbiaceae) and Its Richness in Chemical Constituents with Potential Range of Applications. Phytomed. Plus 2025, 5, 100746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.H.; Liu, W.Y.; Liang, Q. Chemical Constituents from Croton Species and Their Biological Activities. Molecules 2018, 23, 2333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Diabetes Federation IDF Diabetes Atlas 11th Edition—2025, Brussels. 2025. Available online: https://diabetesatlas.org (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Roy, D.; Ghosh, M.; Rangra, K.N. Herbal Approaches to Diabetes Management: Pharmacological Mechanisms and Omics-Driven Discoveries. Phyther. Res. 2025, 39, 5464–5490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, E.C.; Andrade-Cetto, A. Ethnopharmacological Field Study of the Plants Used to Treat Type 2 Diabetes among the Cakchiquels in Guatemala. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 159, 238–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- José Del Carmen, R.O.; Willam, H.M.J.; Del Carmen, G.M.A.; Nataly, J.G.; Stefany, C.O.S.; Anahi, C.A.; Domingo, P.T.J.; Leonardo, G.P.; De La Mora Miguel, P. Antinociceptive Effect of Aqueous Extracts from the Bark of Croton guatemalensis Lotsy in Mice. Res. Pharm. Sci. 2016, 11, 15–22. [Google Scholar]

- Escandón-Rivera, S.M.; Andrade-Cetto, A.; Rosas-Ramírez, D.G.; Arreguín-Espinosa, R. Phytochemical Screening and Isolation of New Ent–Clerodane Diterpenoids from Croton guatemalensis Lotsy. Plants 2022, 11, 3159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Vargas, A.D.; Andrade-Cetto, A.; Espinoza-Hernández, F.A.; Mata-Torres, G. Proposed Mechanisms of Action Participating in the Hypoglycemic Effect of the Traditionally Used Croton guatemalensis Lotsy and Junceic Acid, Its Main Compound. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1436927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutton, J.C.; O’Brien, R.M. Glucose-6-Phosphatase Catalytic Subunit Gene Family. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 29241–29245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, L.S.; Lau, H.H.; Abdelalim, E.M.; Khoo, C.M.; O’Brien, R.M.; Tai, E.S.; Teo, A.K.K. The Role of Glucose-6-Phosphatase Activity in Glucose Homeostasis and Its Potential for Diabetes Therapy. Trends Mol. Med. 2025, 31, 152–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Morris-Natschke, S.L.; Lee, K.H. Clerodane Diterpenes: Sources, Structures, and Biological Activities. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2016, 33, 1166–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Jin, X.Y.; Zhou, J.C.; Zhu, R.X.; Qiao, Y.N.; Zhang, J.Z.; Li, Y.; Zhang, C.Y.; Chen, W.; Chang, W.Q.; et al. Terpenoids from the Chinese Liverwort Heteroscyphus Coalitus and Their Anti-Virulence Activity against Candida Albicans. Phytochemistry 2020, 174, 112324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- dos Lima, J.R.; Marinho, E.M.; Alencar de Menezes, J.E.; Rogênio Mendes, F.S.; da Silva, A.W.; Ferreira, M.K.; Santos Oliveira, L.; Moura Barbosa, I.; Marinho, E.S.; Marinho, M.M.; et al. Biological Properties of Clerodane-Type Diterpenes. J. Anal. Pharm. Res. 2022, 11, https://medcraveonline.com/JAPLR/JAPLR-11-00402.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, S.; Zhu, Y.; Luo, C.; Zhang, P.; Wang, F.; Li, R.; Lin, G.; Zhang, J. Chiral Drugs: Sources, Absolute Configuration Identification, Pharmacological Applications, and Future Research Trends. LabMed Discov. 2024, 1, 100008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Evans, F.J.; Roberts, M.F.; Phillipson, J.D.; Zenk, M.H.; Gleba, Y.Y. Polyphenolic Compounds from Croton lechleri. Phytochemistry 1991, 30, 2033–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravanelli, N.; Santos, K.P.; Motta, L.B.; Lago, J.H.G.; Furlan, C.M. Alkaloids from Croton echinocarpus Baill.: Anti-HIV Potential. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2016, 102, 153–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, G.A.; Aisa, H.A.; Zhang, H.W.; Yang, J.S.; Zou, Z.M.; Shakhidoyatov, K.M. Flavonoids from Croton laevigatus. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2012, 48, 687–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Justino, G.C.; Borges, C.M.; Helena Florêncio, M. Electrospray Ionization Tandem Mass Spectrometry Fragmentation of Protonated Flavone and Flavonol Aglycones: A Re-Examination. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2009, 23, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spáčil, Z.; Nováková, L.; Solich, P. Comparison of Positive and Negative Ion Detection of Tea Catechins Using Tandem Mass Spectrometry and Ultra High Performance Liquid Chromatography. Food Chem. 2010, 123, 535–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuzuak, S.; Ballington, J.; Xie, D.Y. HPLC-QTOF-MS/MS-Based Profiling of Flavan-3-Ols and Dimeric Proanthocyanidins in Berries of Two Muscadine Grape Hybrids FLH 13-11 and FLH 17-66. Metabolites 2018, 8, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Gates, P.J. Systematic Characterisation of the Fragmentation of Flavonoids Using High-Resolution Accurate Mass Electrospray Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Molecules 2024, 29, 5246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carnevale Neto, F.; Andréo, M.A.; Raftery, D.; Lopes, J.L.C.; Lopes, N.P.; Castro-Gamboa, I.; Lameiro de Noronha Sales Maia, B.H.; Costa, E.V.; Vessecchi, R. Characterization of Aporphine Alkaloids by Electrospray Ionization Tandem Mass Spectrometry and Density Functional Theory Calculations. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2020, 34, e8533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Díaz, J.; Tuenter, E.; Escalona Arranz, J.C.; Llauradó Maury, G.; Cos, P.; Pieters, L. Antimicrobial Activity of Leaf Extracts and Isolated Constituents of Croton linearis. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2019, 236, 250–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dantas, E.P.; Monteiro, J.; de Medeiros, L.S.; Romanelli, M.M.; Amaral, M.; Tempone, A.G.; Lago, J.H.G.; Soares, M.G.; Sartorelli, P. Dereplication of Aporphine Alkaloids by UHPLC-HR-ESI-MS/MS and NMR from Duguetia lanceolata St.-Hil (Annonaceae) and Antiparasitic Activity Evaluation. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2020, 31, 1908–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motta, L.B.; Furlan, C.M.; Santos, D.Y.A.C.; Salatino, M.L.F.; Duarte-Almeida, J.M.; Negri, G.; de Carvalho, J.E.; Ruiz, A.L.T.G.; Cordeiro, I.; Salatino, A. Constituents and Antiproliferative Activity of Extracts from Leaves of Croton macrobothrys. Rev. Bras. Farmacogn. 2011, 21, 972–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milanowski, D.J.; Winter, R.E.K.; Elvin-Lewis, M.P.F.; Lewis, W.H. Geographic Distribution of Three Alkaloid Chemotypes of Croton lechleri. J. Nat. Prod. 2002, 65, 814–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaserer, T.; Steinacher, T.; Kainhofer, R.; Erli, F.; Sturm, S.; Waltenberger, B.; Schuster, D.; Spetea, M. Identification and Characterization of Plant-Derived Alkaloids, Corydine and Corydaline, as Novel Mu Opioid Receptor Agonists. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 13804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.J.; Chen, C.H.; Liu, F.W.; Kang, J.J.; Chen, C.K.; Lee, S.L.; Lee, S.S. Inhibition of Intestinal Glucose Uptake by Aporphines and Secoaporphines. Life Sci. 2006, 79, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Shaibany, A.; Alhakami, I.A.; Humaid, A.; Elasser, M. A Review Article of Phytochemical Constitutions of Croton Genus. Eur. J. Pharm. Med. Res. 2022, 9, 64–78. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, S.T.; Chen, C.; Chen, R.X.; Li, R.; Chen, W.L.; Jiang, G.H.; Du, L.L. Michael Acceptor Molecules in Natural Products and Their Mechanism of Action. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1033003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrés, C.M.C.; Pérez de la Lastra, J.M.; Bustamante Munguira, E.; Andrés Juan, C.; Pérez-Lebeña, E. Michael Acceptors as Anti-Cancer Compounds: Coincidence or Causality? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, A.; Tel-Çayan, G.; Öztürk, M.; Duru, M.E.; Nadeem, S.; Anis, I.; Ng, S.W.; Shah, M.R. Phytochemicals from Dodonaea viscosa and Their Antioxidant and Anticholinesterase Activities with Structure–Activity Relationships. Pharm. Biol. 2016, 54, 1649–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girirajan, S.; Campbell, C.; Eichler, E. Synergy and Antagonism in Natural Product Extracts: When 1 + 1 Does Not Equal 2. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2019, 36, 869–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardner, L.B.; Liu, Z.; Barrett, E.J. The Role of Glucose-6-Phosphatase in the Action of Insulin on Hepatic Glucose Production in the Rat. Diabetes 1993, 42, 1614–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Z.; Liu, C.; Wu, D.; Chen, H.; Zhao, J.; Jiang, D. Structural Insights into Glucose-6-Phosphate Recognition and Hydrolysis by Human G6PC1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2025, 122, e2418316122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patil, S.B.; Gadad, P.C. Chlorogenic Acid, a Potential Glucose-6-Phosphatase Inhibitor: An Approach to Develop a Pre-Clinical Glycogen Storage Disease Type I Model. Indian J. Pharm. Educ. Res. 2024, 58, s372–s381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Gan, N.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, L.; Tang, P.; Pu, H.; Zhai, Y.; Gan, R.; Li, H. Insights into Protein Recognition for γ-Lactone Essences and the Effect of Side Chains on Interaction via Microscopic, Spectroscopic, and Simulative Technologies. Food Chem. 2019, 278, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miret-Casals, L.; Van De Putte, S.; Aerssens, D.; Diharce, J.; Bonnet, P.; Madder, A. Equipping Coiled-Coil Peptide Dimers With Furan Warheads Reveals Novel Cross-Link Partners. Front. Chem. 2022, 9, 799706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, A.; Chatzopoulou, M.; Frost, J. Bioisoteres for Carboxylic Acids: From Ionized Isosteres to Novel Unionized Replacements. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2024, 104, 117653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.Y.; Liu, C.J.; Niu, Q.; Yan, X.Y.; Xiao, D.; Zhang, H.L.; Huang, C.Q.; Shi, S.L.; Zuo, A.X.; He, H.P. In Vitro Hypoglycemic Diterpenoids from the Roots of Croton yunnanensis. J. Nat. Prod. 2023, 86, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.Y.; Niu, Q.; Wang, H.X.; Xu, H.N.; Xie, H.X.; Chen, L.; Chen, R.; Zhang, H.L.; Gao, L.; Zuo, A.X.; et al. Structurally Diverse Diterpenoids from the Leaves of Croton mangelong and Their Anti-Diabetic Activity. Phytochemistry 2024, 226, 114206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade-Cetto, A.; Vázquez, R.C. Gluconeogenesis Inhibition and Phytochemical Composition of Two Cecropia Species. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2010, 130, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arion, W.J. Measurement of Intactness of Rat Liver Endoplasmic Reticulum. Methods Enzymol. 1989, 174, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huey, R.; Morris, G.M.; Olson, A.J.; Goodsell, D.S. Software News and Update a Semiempirical Free Energy Force Field with Charge-Based Desolvation. J. Comput. Chem. 2007, 28, 1145–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, G.M.; Goodsell, D.S.; Halliday, R.S.; Huey, R.; Hart, W.E.; Belew, R.K.; Olson, A.J. Automated Docking Using a Lamarckian Genetic Algorithm and an Empirical Binding Free Energy Function. J. Comput. Chem. 1998, 19, 1639–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.