Abstract

Gibberellin (GA)-based seedless cultivation is widely used in the skin-edible interspecific table grape (Vitis labruscana × Vitis vinifera) ‘Shine Muscat’, yet when and how GA treatment reshapes fracture-type texture during berry development remains unclear. This study aimed to identify developmental stages and tissue/cell-wall features associated with GA-dependent differences in berry fracture behavior. We integrated intact-berry fracture testing at harvest (DAFB105), quantitative histology of pericarp/mesocarp tissues just before veraison (DAFB39) and at harvest, sequential cell-wall fractionation assays targeting pectin-rich (uronic acid) and hemicellulose/cellulose-related pools at cell division period, cell expansion period and harvest, and stage-resolved RNA-Seq across the same three developmental stages. GA-treated berries had a larger diameter and showed a higher fracture load and a lower fracture strain than non-treated berries at harvest, while toughness did not differ significantly. Histology revealed thicker pericarp tissues and lower mesocarp cell density in GA-treated berries, together with increased cell-size heterogeneity and enhanced radial cell expansion. Cell wall analyses showed stage-dependent decreases in uronic acid contents in water-, EDTA-, and Na2CO3-soluble fractions in GA-treated berries. Transcriptome profiling indicated GA-responsive expression of putative cell expansion/primary-wall remodeling genes, EXORDIUM and xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolases, at DAFB24 and suggested relatively enhanced ethylene-/senescence-associated transcriptional programs together with pectin-modifying related genes, Polygaracturonase/pectate lyase and pectin methylesterase, in non-treated mature berries. Collectively, GA treatment modifies mesocarp cellular architecture and pectin-centered wall status in a stage-dependent manner, providing a tissue- and cell wall–based framework for interpreting fracture-related texture differences under GA-based seedless cultivation in ‘Shine Muscat’.

1. Introduction

Gibberellin (GA)-induced seedless cultivation in grape (Vitis spp.) has been practiced for decades, originating from small-berry cultivars including Vitis labruscana ‘Delaware’ [1,2]. This technique is also widely applied to the modern premium Japanese interspecific table grape (Vitis labruscana × Vitis vinifera) ‘Shine Muscat’ [3]. The effects of GA treatment on berry texture have been suggested to vary among cultivars [4], and in ‘Shine Muscat’, GA treatment has been reported to increase flesh firmness, a key texture-related quality attribute in table grapes, plausibly through changes in pericarp/mesocarp structure and cell wall (pectin) status [5,6,7,8]. In table grapes, texture is commonly quantified by puncture- or fracture-type mechanical assays on intact berries, in which the measured response reflects combined contributions of the exocarp (skin) and the fleshy pericarp, mainly the mesocarp [6,7].

At the tissue and cellular scales, such mechanical outcomes can be linked to the mesocarp cell size distribution and cell density, as well as the balance between cell-wall deformation and loss of cell-to-cell adhesion mediated by the pectin-rich middle lamella [9,10,11]. Fruit texture changes during development and ripening are associated with remodeling of the primary wall, where cellulose microfibrils form a load-bearing framework embedded in a matrix of hemicelluloses and pectins, and with modification of the pectin-rich middle lamella that governs cell-to-cell adhesion [11,12]. Xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolases (XTHs) remodel xyloglucan–cellulose associations in primary walls and can modulate wall extensibility during growth, including fruit cell expansion [13,14,15]. Since grape mesocarp development involves extensive cell expansion, stage-dependent regulation of XTHs is a plausible molecular component linking primary-wall remodeling to changes in cell size distribution and tissue mechanics [16,17]. In parallel, the mechanics of the middle lamella and cell-to-cell adhesion are strongly influenced by homogalacturonan-rich pectins. De-methyl-esterified homogalacturonan, which is rich in galacturonic acid residues, can form Ca2+-mediated crosslinks that influence middle-lamella mechanics and cell-to-cell adhesion [12,18]. In this study, we focused on cell wall modification, specifically enzymatic remodeling and solubilization of mesocarp wall polysaccharides, with an emphasis on galacturonan-rich pectins and xyloglucan-related hemicelluloses. Fractionation studies of grape mesocarp cell walls across veraison have shown increased solubilization and molecular-weight shifts in pectin- and xyloglucan-rich fractions, consistent with progressive weakening of middle-lamella–mediated cell adhesion and altered flesh mechanics [19,20,21]. In such assays, uronic-acid content is widely used as a compositional proxy for galacturonan-rich pectins, and variation in uronic-acid-rich fractions has been linked to firmness differences during ripening and storage [19,22].

Collectively, previous studies suggest that GA-induced seedless cultivation can increase firmness-related mechanical indices of ‘Shine Muscat’ berries and is accompanied by changes in mesocarp cell wall composition, particularly in pectin-rich fractions [4,5]. However, integrated studies that combine mechanical testing with quantitative tissue descriptors, cell wall compositional analyses, and transcriptome profiling remain limited in ‘Shine Muscat’. In particular, it remains unclear at which developmental stages GA treatment drives divergences in mesocarp cell expansion and wall-remodeling processes relevant to primary-wall extensibility and middle–lamella–associated cell adhesion. Transcriptomic studies indicate that exogenous gibberellin triggers coordinated gene-expression programs in grapevine tissues relevant to seedlessness/parthenocarpy and early berry development [23,24]. Related transcriptome shifts have also been described under practical seedless-treatment regimes in ‘Shine Muscat’ during veraison stages to over-ripening, focusing on aroma components [3]. Nevertheless, transcriptome evidence explicitly linking GA-treated seedless cultivation to berry mechanical texture traits remains limited, particularly in studies that integrate mechanical phenotyping with quantitative histology and cell wall descriptors.

Therefore, the primary objective of this study was to determine when and how GA treatment induces changes in mesocarp cell expansion and pectin solubility throughout development, and to assess the relationship between these changes and altered fracture-type mechanical behavior at harvest. Specifically, we performed intact-berry fracture testing, quantitative histology, sequential cell-wall fractionation (pectin-rich uronic-acid fractions, hemicellulose-enriched sugar fractions, and a cellulose-enriched insoluble residue), and stage-resolved RNA-Seq across key developmental stages.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Fracture Properties of Berries at Harvest

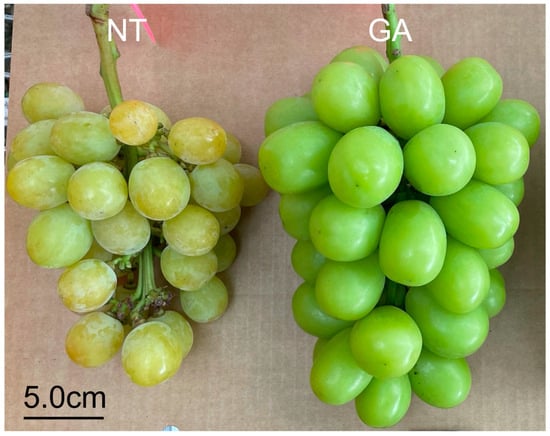

The harvested grape clusters are shown in Figure 1 a day after full bloom (DAFB) 105. At harvest time, the equatorial diameter of GA-treated berries was greater than that of non-treated berries (Table 1). GA-treated ‘Shine Muscat’ berries exhibited a significantly higher fracture load and a significantly lower fracture strain than non-treated berries (Table 1). These results suggest that GA treatment enhanced resistance to fracture while reducing the deformation capacity before fracture at harvest. Toughness (strain energy density to fracture) did not differ significantly between treatments; however, its mean value was lower in GA-treated berries than in non-treated berries (Table 1). Crispness is associated with brittle failure, characterized by relatively sudden fracture with limited deformation [25]. In contrast, a jelly-like texture is soft and deforms substantially before fracture, even when the work to fracture is low [25]. The combination of higher fracture load and lower fracture strain in GA-treated berries is consistent with a shift toward a more brittle-like fracture response in intact-berry testing.

Figure 1.

The harvested grape clusters. The photograph shows V. labruscana × V. vinifera ‘Shine Muscat’ grape clusters at DAFB105 (scale bar = 5.0 cm). GA, GA-treated clusters; NT, non-treated clusters.

Table 1.

Effects of GA treatment on berry texture traits in ‘Shine Muscat’.

2.2. Histological Analysis of Berry Tissue

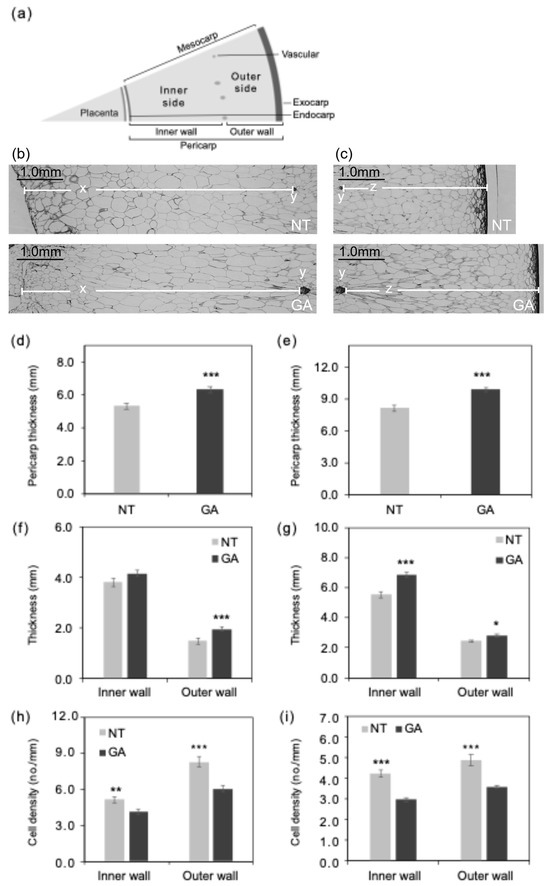

The structure of a grape berry is illustrated in Figure 2a. In this study, the term “pericarp” collectively refers to the exocarp, mesocarp, and endocarp (Figure 2a). The exocarp is sometimes referred to as the skin. Within the pericarp, the region inside the vascular bundles was defined as the inner wall. The region outside the vascular bundles was defined as the outer wall (Figure 2a). In addition, within the mesocarp, the region inside the vascular bundles was defined as the inner side. The region outside the vascular bundles was defined as the outer side (Figure 2a). Thus, the inner wall comprises the endocarp and the inner side of the mesocarp. In contrast, the outer wall comprises the outer side of the mesocarp and the exocarp (Figure 2a). Representative equatorial cross-sections of non-GA-treated seeded and GA-treated seedless berries at 105 days after full bloom (DAFB105) are also presented (Figure 2b,c). Inner wall sides of pericarp are shown in Figure 2b and outer wall sides of pericarp are shown in Figure 2c. The pericarp is referred to as the inner wall and outer wall on the inner and outer sides of the vascular ring, respectively [26]. It has been reported that, in mature ‘Delaware’ grapes, the inner wall, outer wall, and placental tissue occupy 59.7%, 17.4% and 9.9% of the total cross-sectional area at maturity, respectively [26]. Based on previous studies, the mesocarp constitutes the majority of both the inner and outer walls [26], suggesting that the flesh is predominantly composed of the mesocarp.

Figure 2.

Histological characteristics of the pericarp tissue structure. (a) Schematic diagram of the structure of a fresh grape berry. Pericarp structure near the equatorial plane (b) inner wall and (c) outer wall side at DAFB105 (scale bars = 1.0 mm). x, inner wall of pericarp; y, vascular; z, outer wall of pericarp. (d,e) Pericarp thickness at DAFB39 and DAFB105, respectively. (f,g) Thickness of the inner and outer walls of the pericarp at DAFB 39 and DAFB 105, respectively. Inner wall, inner wall of the pericarp; Outer wall, outer wall of the pericarp. (h,i) Mesocarp cell density on the inner and outer sides at DAFB 39 and DAFB 105, respectively. Inner side, inner side of the mesocarp; Outer side, outer side of the mesocarp. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; Welch’s t-test; n = 18–23. Error bars indicate standard error. GA, GA-treated berries; NT, non-treated berries.

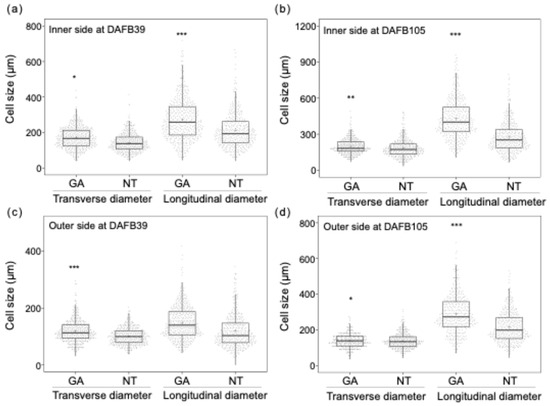

The pericarp of GA-treated berries was thicker than that of non-treated berries at DAFB39 and DAFB105 (Figure 2d,e). The outer wall of the pericarp was thicker in GA-treated berries than in non-treated berries at DAFB39 (Figure 2f). In contrast, both the inner and outer walls of the pericarp were thicker in GA-treated berries at DAFB105 (Figure 2g). The pericarp was thicker in GA-treated berries than in non-treated berries (Figure 2d,e), which was consistent with the larger berry size observed in GA-treated berries (Figure 1). Cell density in both the inner and outer sides of the mesocarp was lower in GA-treated berries than in non-treated berries at DAFB39 and DAFB105 (Figure 2h,i). The transverse (circumferential) and longitudinal (radial) diameters of cells in the inner side of the mesocarp exhibited greater variability in GA-treated berries than in non-treated berries at DAFB39 (Figure 3a), and the transverse diameter of cells in the outer side of the mesocarp also showed higher variability in GA-treated berries at this at DAFB39 (Figure 3b). Both transverse and longitudinal cell diameters in the inner and outer sides of the mesocarp displayed greater variability in GA-treated berries than in non-treated berries at DAFB105 (Figure 3c,d).

Figure 3.

Cell size distributions of the (a) inner and (b) outer sides of the mesocarp at DAFB39 and the (c) inner and (d) outer sides of the mesocarp at DAFB105 (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; F-test for equality of variances; n = 360–460 cells). The box plot displays the interquartile range (IQR) with the median indicated by a horizontal line. Whiskers extend to 1.5 × IQR, jittered points represent individual cell measurements, and the mean is denoted by a plus sign (+). Inner side, inner side of the mesocarp; Outer side, outer side of the mesocarp; GA, GA-treated berries; NT, non-treated berries; Transverse, circumferential on the equatorial plane of the berry; Longitudinal, radial on the equatorial plane of the berry.

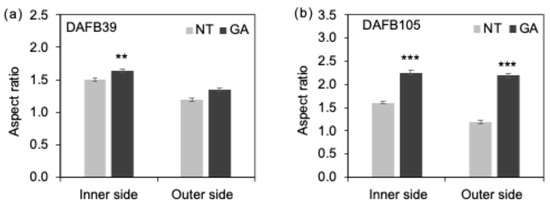

In addition, the longitudinal-to-transverse ratio of cells in the inner side of the mesocarp was higher in GA-treated berries at both DAFB39 and DAFB105, and a similar tendency was observed in the outer side of the mesocarp at DAFB105 (Figure 4a,b). Consistent with these results, the distributions of cell sizes in both the inner and outer sides of the mesocarp at DAFB105 were broader in GA-treated berries than in non-treated berries (Figure S1). These observations suggest that GA treatment promoted radial cell expansion in the mesocarp and increased cell size heterogeneity relative to non-treated berries.

Figure 4.

Cell shape. Cell aspect ratio at (a) DAFB39 and (b) DAFB105, respectively (**, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; Welch’s t-test; n = 360–460 cells). Error bars indicate standard error. Inner side, inner side of the mesocarp; Outer side, outer side of the mesocarp. GA, GA-treated berries; NT, non-treated berries.

Cell-size heterogeneity can influence tissue-scale mechanics by altering the distribution of stresses within the cellular network. In strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa), volumetric cell-size distributions were quantitatively associated with tissue elastic modulus and failure stress, with less heterogeneous distributions generally corresponding to mechanically stronger tissues [27]. Although comparable quantitative evidence remains limited in grape berries, GA3-induced parthenocarpy in ‘Delaware’ has been reported to modify patterns of cell proliferation and enlargement across pericarp tissues [28], supporting the view that GA treatment can shift the balance between cell division and expansion. Consistent with the idea that cellular architecture and wall chemistry jointly condition texture, firmness differences between inner and outer mesocarp tissues in table grapes have also been linked to pectin methyl-esterification status and cell-wall-associated calcium [29]. Previous studies have shown that tomato (Solanum lycopersicum), a model for fruit development, treated with GA3 alone had fewer cell layers but larger mesocarp cell diameters than pollinated fruits at 21 days after anthesis (DAA) [30], which is consistent with our results in grape. In addition, Lu et al. [31] suggested that GA stimulates mesocarp cell expansion in grape, whereas auxin and cytokinin stimulate mesocarp cell division. Therefore, the decreased cell density observed in this study is likely a secondary consequence of enhanced cell enlargement.

2.3. Plant Cell Wall Component Analysis

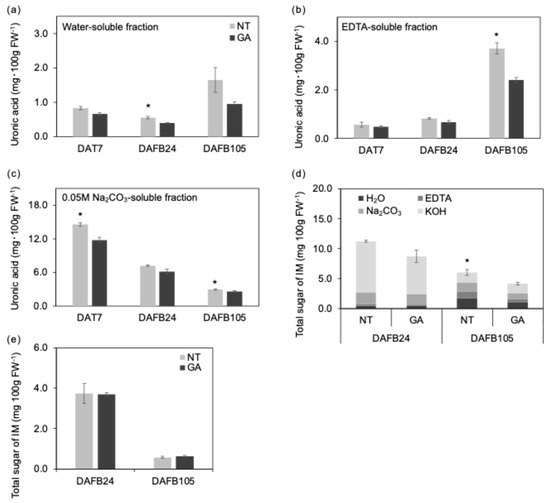

The uronic acid content in the water-soluble fraction of GA-treated berries was lower than that of non-treated berries at DAFB24 (Figure 5a). The uronic acid content in the EDTA-soluble fraction of GA-treated berries was also lower than that of non-treated berries at DAFB105 (Figure 5b). In addition, at DAFB10 and DAFB105, the uronic acid content in the Na2CO3-soluble fraction was lower in GA-treated berries than in non-treated berries (Figure 5c). The EDTA-soluble fraction is considered an operational indicator reflecting pectins that were retained in the cell wall via ionic interactions with cations, primary Ca2+, and subsequently solubilized by chelation [32,33]. Because the solubility of cell wall polysaccharides defines these fractions, quantitative differences should be interpreted in conjunction with qualitative changes such as molecular weight and the degree of de-methylesterification. Moreover, the relationship between pectin modification and fruit texture during ripening is not straightforward, and changes in fraction abundance alone do not necessarily explain differences in stiffness or firmness [9,10].

Figure 5.

Cell wall components in the mesocarp and endocarp. (a) Water-soluble, (b) EDTA-soluble, and (c) 0.05 M Na2CO3-soluble uronic acid contents were pectin-related. (d) Hemicellulose-related sugar content. H2O, water-soluble fraction; EDTA, EDTA-soluble fraction; Na2CO3, 0.05 M Na2CO3-soluble fraction; KOH, 4 M KOH-soluble fraction. (e) Insoluble material (IM). *, p < 0.05; n = 3. Error bars indicate standard error. GA, GA-treated berries; NT, non-treated berries.

De-methylesterification of homogalacturonan can promote Ca2+-mediated crosslinking and facilitate the formation of pectin–Ca gels with an egg-box-like structure [34,35]. Thus, an increase in the EDTA-soluble fraction may contribute less to directly enhancing the maximum tissue strength than to modulating cell-to-cell adhesion and gel-like viscoelastic behavior [18,35,36]. In fruits, the status of cell-to-cell adhesion has been shown to affect fracture mode (cell separation vs. cell rupture) and associated mechanical properties [37]. Accordingly, differences in pectin status and intercellular adhesion could alter fracture mode, such that maximum strength and deformation tolerance do not necessarily change in the same direction. In this context, the lower fracture load and higher fracture strain observed in GA-non-treated berries at the mature stage may reflect reduced maximum strength due to ripening- and senescence-associated cell wall reorganization, while differences in pectin status and cellular arrangement may have relatively maintained or enhanced deformation tolerance and energy absorption. Because Honda et al. [3] showed that nontreated ‘Shine Muscat’ berries ripen later than GA-treated berries on sugar and aromatic component under a comparable plant growth regulator regime, the greater softness of our nontreated berries is unlikely to reflect over-ripening. By contrast, because no significant difference was detected in total sugar content in the 4 M KOH-soluble fraction (Figure 5d), quantitative changes in alkali-soluble polysaccharides (hemicelluloses enriched fraction) were not prominent under our analytical conditions. The whole total sugar content was higher in the non-treated fruit (Figure 5d). Likewise, the absence of a clear difference in total sugar content in the insoluble material suggests that quantitative changes in cellulose-related components (Figure 5d) were not substantial.

Overall, these results suggest that, in the mesocarp at maturity, GA treatment may have stepwise effects on the balance between pectin solubilization and retention and on pectin structural status, thereby contributing to textural differences. In our study, the lower EDTA-soluble uronic acid content in GA-treated berries at DAFB105 may reflect altered ionically bound pectin pools and/or reduced Ca2+-associated pectin retention, which could influence cell-to-cell adhesion and fracture behavior at maturity.

2.4. Transcriptome Analysis

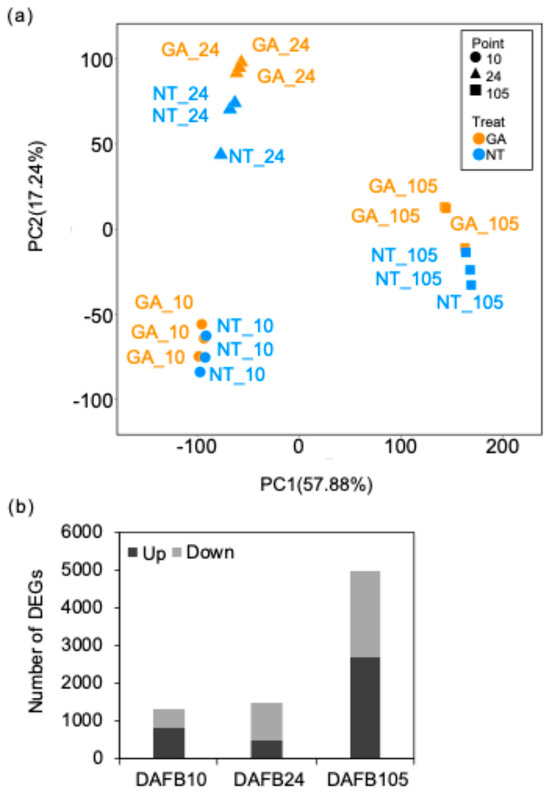

Approximately 20,079,000–26,106,000 reads were obtained from each sample (Table S1). Principal component analysis (PCA) showed that the first principal component (PC1; 57.88% of the variance) separated at DAFB105 from the other stages (Figure 6a). The second principal component (PC2; 17.24%) primarily reflected stage-dependent variation, with the treatment effect also partially captured along this axis (Figure 6a). Differential expression analysis (padj < 0.05) identified 1326 genes at DAFB10, of which 824 were upregulated and 502 were downregulated in GA-treated berries relative to non-treated berries (Figure 6b). 1475 genes were differentially expressed (494 upregulated and 981 downregulated in GA-treated berries) at DAFB24, whereas 4964 genes were differentially expressed at DAFB105 (2668 upregulated and 2296 downregulated in GA-treated berries) (Figure 6b). The differential expression genes (DEGs) between GA-treated vs. non-treated berry were showed in Tables S2–S4.

Figure 6.

RNA-Seq summary. (a) PCA based on gene expression levels. The first principal component (PC1, 57.88% of the variance explained) and the second principal component (PC2, 17.24%). GA, GA-treated berries, NT, non-GA-treated berries. (b) Number of DEGs. DEGs were genes with a padj < 0.05. Up, higher expression in GA-treated berries than non-treated berries; down, lower expression in GA-treated than NT berries. 10, DAFB10, 24, DAFB24, 105, DAFB105 (harvest stage).

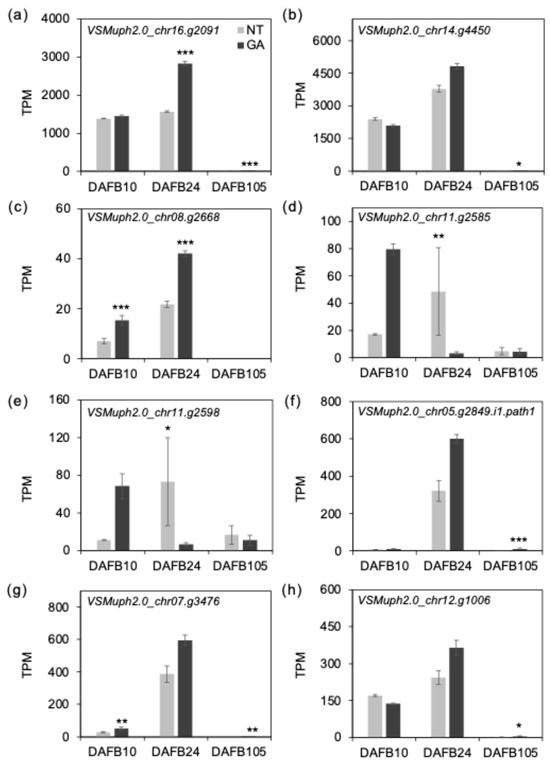

Gene expression levels were summarized as transcripts per million (TPM), a gene length- and library size-normalized measure, and TPM values were used in the following analyses and figures [38,39]. To interpret the transcriptome data in relation to our anatomical observations, we focused on genes putatively involved in cell expansion and cell wall remodeling, including EXORDIUM/EXORDIUM-like (EXO), expansins (EXP), and xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolases (XTH/XET). The expression of VSMuph2.0_chr16.g2091, which is predicted to encode an EXORDIUM_like protein, was higher in GA-treated berries at DAFB24 (Figure 7a), and VSMuph2.0_chr14.g4450, annotated as an expansin-like gene, also showed a tendency toward higher expression at DAFB24 (Figure 7b). EXO has been reported to be involved in the regulation of cell proliferation and to promote cell expansion in Arabidopsis thaliana [40,41], suggesting a potential role in cell enlargement in fruit tissues. Expansins are cell wall-localized proteins that promote cell expansion by inducing cell wall loosening [42,43]. Transcript levels of VSMuph2.0_chr08.g2668, annotated as xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase 32-like (XTH32-like), were higher in GA-treated berries at DAFB10 and DAFB24 (Figure 7c). VSMuph2.0_chr08.g2668 was annotated as a group IIIA XTH (VIT_208s0007g04950), a clade enriched for enzymes with xyloglucan endohydrolase (XEH) activity [44]. Transcripts of XTH6-like genes were lower in GA-treated berries at DAFB24 (Figure 7d,e). In contrast, the more highly expressed XTH-like genes tended to show higher transcript levels in GA-treated berries at the same stage (Figure 7f–h). Together, these patterns indicated that GA effects on the XTH family are gene-dependent and may shift the relative contribution of different XTH members during early berry development. Because several GA-upregulated XTH-like genes shown here are among the more abundant XTH transcripts examined, the aggregate XTH transcript level across this subset could be higher under GA treatment at DAFB24. XTHs remodel xyloglucan, a major hemicellulose associated with cellulose microfibril surfaces in primary walls; most catalyze transglycosylation reactions, whereas a subset shows higher hydrolase activity, thereby modulating microfibril–matrix coupling and primary-wall extensibility in a context-dependent manner [13,14,15]. In addition, the upregulation of putative cell expansion–related genes (including EXO-like transcripts) in GA-treated berries during the active cell enlargement stage, together with the GA-associated induction of several XTH-like genes, is consistent with a scenario in which GA enhances primary-wall extensibility through activation of xyloglucan/hemicellulose remodeling. These coordinated changes may facilitate radial mesocarp cell expansion and contribute to the increased mean cell size and broader cell-size distributions observed in GA-treated berries.

Figure 7.

Expression of putative cell expansion-related genes. TPM values of (a) VSMuph2.0_chr16.g2091 (EXORDIUM-Like 3), (b) VSMuph2.0_chr14.g4450 (expansin A1), (c) VSMuph2.0_chr08.g2668 (xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase 32), (d) VSMuph2.0_chr11.g2585 (xyloglucan endotransglycosylase 6), (e) VSMuph2.0_chr11.g2598 (xyloglucan endotransglycosylase 6), (f) VSMuph2.0_chr05.g2849 (xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase 15), (g) VSMuph2.0_chr07.g3476 (xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase 7) and (h) VSMuph2.0_chr12.g1006 (xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase 9). Error bars indicate standard error, n = 3. *, padj < 0.05; **, padj < 0.01; ***, padj < 0.001. GA, GA-treated berries; NT, non-treated berries.

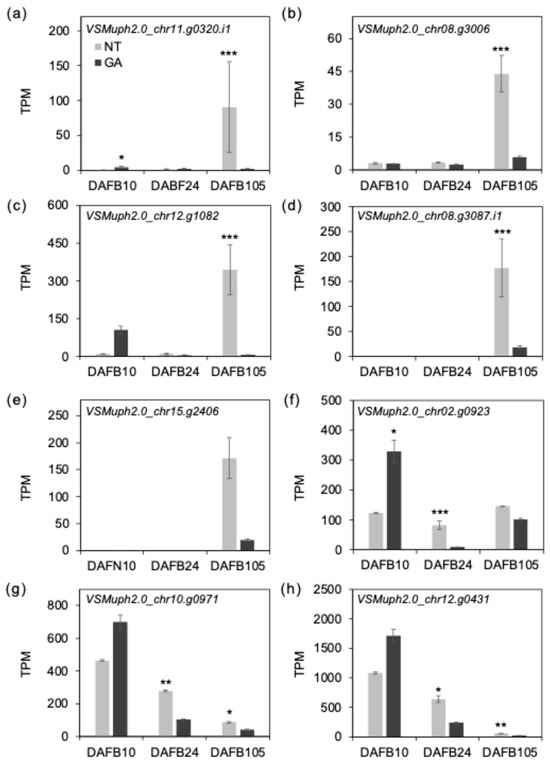

To examine transcriptional differences at harvest (DAFB105), we screened DEGs showing large expression changes (|log2FC| ≥ 2, DESeq2) and identified an aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate oxidase 1-like (ACO1-like) gene (VSMuph2.0_chr11.g0320, Figure 8a), which exhibited a extremely high fold change (|log2FC| > 5, Table S4). ACC oxidase catalyzes the final step of ethylene biosynthesis [45], and ethylene-associated ripening/senescence programs can contribute to softening through regulation of pectin-related cell wall remodeling [46]. In grape, ripening/softening–associated expression of pectin-modifying genes in the skin supports active pectin remodeling during maturation [47], so we used the ACO1-like expression pattern to prioritize similarly regulated candidate genes. Because ACO1-like transcript levels showed substantial among-replicate variability, we considered that some biologically linked genes might not be recovered as DEGs under stringent multiple-testing correction; therefore, we additionally performed a co-expression-based prioritization using the ACO1-like expression profile. Using Pearson correlation on log2(TPM + 1) values (r ≥ 0.8), we identified 315 genes that were highly correlated with the ACO1-like gene (Table S5). As a result, NAC87 like, wound-responsive genes, and genes annotated polygalacturonase/pectate lyase—like and pectin methylethterase-like proteins were found to be preferentially and strongly expressed in non-treated berries at maturity (Figure 8b–e). PMEs de-methyl-esterify homogalacturonan (HG), thereby shifting the balance between Ca2+-mediated crosslinking and the susceptibility of HG to solubilization and depolymerization by pectin-depolymerizing enzymes such as polygalacturonases and pectate lyases [34,36,48]. NAC87-like is annotated as a homolog of A. thaliana ANAC087, which has been implicated in programmed cell death [49] and was recently shown to positively regulate age-dependent leaf senescence [50]. This behavior is consistent with the possible activation of a senescence-like/stress-associated transcriptional program in non-treated mature berries in the present study. In addition, several ethylene responsive factor (ERF)-like gene transcripts with relatively high abundance at maturity, including VSMuph2.0_chr12.g0431 and VSMuph2.0_chr10.g0971, were significantly higher in non-treated berries (Figure 8f–h). These results support the possibility that non-treated mature berries exhibit a relatively enhanced ethylene-associated program coupled with stress-/senescence-like regulation, which may facilitate pectin remodeling and contribute to the softer and/or gummy fracture behavior observed at harvest. Notably, ERF-like transcripts exhibited treatment-dependent differences as early as DAFB24. While ERF–ACO1 patterns were not tightly aligned at early stages, ACS1 showed a broadly similar trend to the ERF profile at DAFB10–24 (Figure S2), suggesting that ethylene/ERF-associated transcriptional states may diverge early during the cell enlargement phase.

Figure 8.

Expression of putative ethylene-related genes. TPM values of (a) VSMuph2.0_chr11.g0320 (ACC oxidase 1), (b) VSMuph2.0_chr08.g3006 (NAC domain containing protein 87), (c) VSMuph2.0_chr12.g1082 (Wound-responsive family protein), (d) VSMuph2.0_chr08.g3087.i1 (Pectin lyase-like superfamily protein), (e) VSMuph2.0_chr15.g2406 (Plant invertase/pectin methylesterase inhibitor superfamily), (f) VSMuph2.0_chr02.g0923 (ethylene responsive element binding factor 1), (g) VSMuph2.0_chr10.g0971 (erf domain protein 9) and (h) VSMuph2.0_chr12.g0431.1 (erf domain protein 9). Error bars indicate standard error, n = 3. *, padj < 0.05; **, padj < 0.01; ***, padj < 0.001. GA, GA-treated berries; NT, non-treated berries.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Plant Material

Interspecific grapevines (Vitis labruscana × V. vinifera) ‘Shine muscat’ grown in 2023 at the experimental vineyard of Horticultural Research Institute, Yamagata Integrated Agricultural Research Center, Yamagata, Japan, was used in this study. For the compositional analyses and RNA-Seq, three clusters per treatment were sampled, each taken from a different fruiting shoot within the same vine. For each cluster, ten berries were collected and pooled to generate one biological replicate (n = 3). Each cluster was treated as an independent biological replicate. For the fracture test, berries were sampled at 105 days after full bloom (DAFB105, harvest time), and 6–10 berries were collected from each of 5–8 clusters per treatment (n = 4–8). For histological analysis, berries were sampled at DAFB39 (veraison stage for seedless berries) and DAFB105 (harvest time), with 5–10 berries each collected from the three clusters per treatment. For cell wall component analysis and gene expression analysis was performed on berries sampled at DAFB10 and DAFB24, representing the early (cell proliferation–dominant) and subsequent (active cell-expansion) phases, respectively, and at DAFB105, which corresponds to the harvest stage. Ten Berries were collected from each of three clusters per treatment (n = 3). For these analyses, the exocarp, placenta, and seeds were removed from each berry to obtain mesocarp and endocarp tissues. The samples were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until use.

3.2. Plant Hormone Treatment

All clusters on the experimental vines were sprayed with a 1:2000 dilution of mepiquat chloride (Nisso Flaster; Nippon Soda Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) at 9 days before full bloom. In the GA-treated group, cluster dipping with 200 mg/L streptomycin (Mitsui Chemicals Crop & Life Solutions, Inc., Tokyo, Japan) was performed at 8 days before full bloom according to a conventional seedless cultivation protocol.

Gibberellin (GA) treatment was applied twice, at DAFB3 and DAFB15. For the first treatment, flower clusters were dipped in a mixed solution containing 25 mg/L GA3 (Sumitomo Chemical Co., Ltd. Tokyo, Japan), and 5 mg/L CPPU (Fulmet; Sumitomo Chemical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). For the second treatment, fruit clusters were dipped in a solution containing 25 mg/L GA3.

3.3. Fruit Instrumental Texture Analysis

All berries were first measured for berry equatorial largest diameter and then subjected to a fracture test using a creep meter (RE2-3305C; YAMADEN Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) at the Horticultural Research Institute, Yamagata Integrated Agricultural Research Center. A cylindrical plunger (3.0 mm in diameter) was driven through the berry near the equatorial region at a table speed of 1 mm s−1. The amplifier gain was set to ×10. Each intact berry was positioned with the equatorial plane perpendicular to the plunger axis and compressed until the first fracture event occurred, which was identified as the first peak force followed by an abrupt force drop on the force–displacement curve. The force at the first fracture event was recorded as the fracture load (N). Fracture strain (%) was calculated as (ΔL1stfracture/D × 100), where ΔL1stfracture is plunger displacement from initial contact to first fracture (mm) and D is equatorial berry diameter (mm). Toughness (strain energy density to first fracture; kJ m−3) was computed as the area under the force–displacement curve up to the first fracture event, normalized by the product of plunger cross-sectional area and equatorial berry diameter.

3.4. Histological Analysis

All berries used for histological observation were sliced to approximately 2.0 mm thickness around the equatorial region and fixed in 50–100 volumes of FAA solution (100% ethanol: glacial acetic acid: formalin: ultrapure water = 12:1:1:6). Samples were vacuum-infiltrated and stored in glass bottles until use [51]. Samples preserved in FAA solution were washed twice with 60% ethanol and then gradually transferred to 100% ethanol for solvent exchange [51]. During the exchange procedure, samples were vacuum-infiltrated under reduced pressure and then immersed for at least 12 h at each step [51]. For resin embedding, Technovit® 7100 (Kulzer, Hanau, Germany) was used. Resin substitution solutions were prepared by mixing Technovit® 7100 with hardener I (100 mL Technovit® 7100 per 1.0 g hardener I) as precursors of the embedding resin, and samples were gradually transferred from 100% ethanol to increasing concentrations of the resin substitution solutions [51,52]. During each substitution step, samples were vacuum-infiltrated under reduced pressure and then incubated on a rotator for at least 12 h [51]. For embedding, the resin solution and hardener II were mixed at a 11:1 ratio to prepare the embedding resin [51]. Samples were placed in silicone molds and filled with the resin [51]. After adjusting the orientation of the samples, polymerization was allowed to proceed at 4 °C in the dark for at least 8 h, followed by incubation at room temperature (25 °C) until the resin was completely hardened [51]. The polymerized resin blocks were then glued onto wooden blocks for sectioning [51].

Transverse sections (9–12 μm thick) near the equatorial region were prepared using a rotary microtome (No.1115, Yamato Kohki Industrial Co., Ltd., Saitama, Japan) equipped with a disposable microtome blade (Feather, S35; Feather Safety Razor Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan). Sections were mounted on slides using a stretching device, stained with a 5.0 mg/L toluidine blue solution (Waldeck GmbH & Co. KG, Münster, Germany), and observed under a digital microscope (DIM-03; Alfa Mirage Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan). These procedures were adapted from previously published methods (Ishikawa et al. [51]; Kuroiwa [52]).

Cell density was estimated based on the length corresponding to 10 cells in the inner side or 5 cells in the outer side of the mesocarp. For cell size analysis, radial (longitudinal) and circumferential (transverse) diameters of randomly selected cells in the inner and outer regions were measured to calculate the aspect ratio. The radial axis was defined as the longitudinal diameter, and the circumferential axis as the transverse diameter on the equatorial section. Mesocarp cell size was measured separately in the inner- and outer wall regions.

3.5. Analysis of Cell Wall Components

Alcohol-insoluble residue (AIR) was prepared from 100 to 300 mg of frozen berry tissue by adding 1.5 mL of 80% ethanol, centrifuging, removing the supernatant, and drying the pellet. The AIR was extracted with 1.6 mL distilled water for 20 h with shaking to obtain the water-soluble fraction. The residue was then extracted sequentially with 1.6 mL of 0.05 M ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid for 20 h (EDTA-soluble fraction) and with 1.6 mL of 0.05 M Na2CO3 for 20 h (Na2CO3-soluble fraction).

To remove starch, 1.6 mL sodium acetate buffer (20 mM, pH 6.5) was added to the residue, followed by incubation in boiling water for 5 min. After cooling to room temperature, 320 μL of a mixed enzyme solution containing 8 units mL−1 α-amylase (Sigma-Aldrich Japan, Tokyo, Japan) and 8 units mL−1 glucoamylase (Sigma-Aldrich Japan, Tokyo, Japan) was added, and the mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. After removing the supernatant, the residue was washed twice with distilled water.

The residue was then extracted with 1.6 mL of 4 M KOH for 20 h with shaking to obtain the KOH-soluble fraction (KOHSF). The remaining residue was washed twice with 800 μL of 0.1 N acetic acid and twice with 800 μL of a 1:1 (v/v) ethanol:diethyl ether mixture. The washed residue was dried at 100 °C for 48 h and used as the insoluble material.

As pectin-related components, uronic acid contents of the H2O-, EDTA-, and Na2CO3-soluble fractions were quantified using the m-hydroxydiphenyl method [53]. Total sugar contents of all fractions were determined by the phenol-sulfuric acid method [54]. For cellulose-related sugars, the insoluble material was dissolved in 0.2 mL of 72% sulfuric acid and incubated for 12 h at room temperature. The solution was then diluted with 2.8 mL of distilled water and analyzed using the phenol–sulfuric acid method. Absorbance was measured at 520 nm for uronic acids (as galacturonic acid equivalents) and at 490 nm for total sugars (as glucose equivalents). All cell wall component contents were expressed on a 100 g fresh weight basis. These methods followed those of Oida et al. [5,8] with minor modifications.

3.6. RNA Isolation

All samples were pulverized under frozen conditions prior to RNA extraction. Total RNA was extracted using the Cica genius® RNA Prep Kit (for Plant) (Kanto Chemical Co., Inc., Tokyo, Japan). The modified extraction buffer described by McQuinn et al. [55] was used.

3.7. RNA Sequencing and Expression Analysis

RNA libraries were prepared using the NEBNext® Ultra™ II Directional RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina® (New England Biolabs, Inc., Ipswich, MA, USA). Paired-end sequencing (150 bp) was performed on a DNBSEQ-Q7 platform (MGI). Raw reads were assessed using FastQC and trimmed with Trimmomatic v0.39 (Table S1). Trimmed reads were mapped to the ‘Shine Muscat’ genome available in PLANT GARDEN using HISAT2 v2.2.1 [56]. Read counts and TPM values were calculated with StringTie v2.2.3. Annotation of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) was obtained by local BLAST (version 2.16.0) searches against A. thaliana against A. thaliana reference sequences (TAIR10.1), with a significance threshold of E < 1 × 10−5.

3.8. Statistical Analysis

Differences between means in the fracture tests and in the analyses of plant cell wall components were evaluated using Welch’s t-test. For histological analyses, Welch’s t-test was used for all comparisons of means except for the comparison of mesocarp cell size. For the comparison of mesocarp cell size in the histological analysis, an F-test (two-sample for variances) was applied.

The baseMan, log2 fold change (log2FC), and padj (FDR-adjusted p-value) were calculated using DESeq2 in R v4.4.1. PCA was performed using values normalized for library size differences (total read counts) by DESeq2 via size factors and transformed by variance stabilizing transformation (VST). DEGs were defined as genes with padj < 0.05 based on read count data.

Similarity in gene expression patterns was assessed in R using TPM values transformed as log2 (TPM + 1). Pearson correlation coefficients with the gene of interest (VSMuph2.0_chr11.g0320) were computed using the base R function cor(). Genes with correlation coefficients of r ≥ 0.8 were extracted as similar genes. Genes with TPM = 0 across all samples were excluded from the analysis.

4. Conclusions

GA-based seedless cultivation in ‘Shine Muscat’ was associated with a clear shift in intact-berry fracture behavior at harvest. GA-treated berries exhibited a higher fracture load and a lower fracture strain than non-treated berries at DAFB105, indicating greater resistance to first failure with reduced deformation capacity, while toughness did not differ significantly. Pronounced differences in pericarp/mesocarp histology accompanied this mechanical shift. GA-treated berries had a thicker pericarp at both DAFB39 and DAFB105 and showed lower mesocarp cell density, together with greater cell-size heterogeneity and enhanced radial cell expansion. These features provide a plausible tissue-level basis for altered fracture-type texture, because both cellular architecture and cell-to-cell adhesion contribute to failure modes in fleshy fruit tissues. Cell wall fractionation further indicated stage-dependent changes in pectin-enriched pools. Uronic acid contents in water-, EDTA-, and Na2CO3-soluble fractions were lower in GA-treated berries at specific stages, whereas hemicellulose- and cellulose-related fractions showed no significant quantitative differences under our analytical conditions. Although fraction abundance alone cannot resolve pectin chemistry, these results support the view that GA treatment alters the balance of pectin solubilization/retention in a stage-dependent manner, which could influence middle-lamella mechanics and thus fracture behavior.

Transcriptome profiles were consistent with a developmental transition in candidate processes underlying these phenotypes. During early development (DAFB10–24), GA-responsive expression of putative cell expansion and primary-wall remodeling genes (EXO/EXP/XTH) supports a scenario in which GA promotes primary-wall extensibility and radial mesocarp expansion. At maturity (DAFB105), non-treated berries exhibited higher expression of ACO1-like and ERF-like transcripts together with stress-/senescence-associated candidates (including NAC87-like and wound-responsive genes) and pectin-modifying enzyme genes (PME- and PG/PL-like), suggesting relatively enhanced ethylene-/senescence-associated transcriptional programs that may facilitate pectin remodeling and contribute to a softer and/or gummy fracture behavior.

Collectively, our integrative approach links intact-berry fracture behavior to stage-resolved changes in mesocarp cellular architecture and pectin-centered wall traits under GA-based seedless cultivation. The anatomical descriptors and pectin-related soluble fractions highlighted here provide candidate intermediate traits for cultivar comparison and management optimization. Future studies that couple tissue-resolved mechanical analyses (skin vs. adjacent flesh) with detailed pectin chemistry (degree/pattern of methylesterification, Ca2+ association, and polymer depolymerization) will be essential to validate the mechanistic roles of the wall-remodeling and cell-adhesion candidates suggested by our transcriptome profiles.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/plants15020287/s1, Table S1. RNA-Seq read data quality summary; Table S2. DEGs DAFB10; Table S3. DEGs DAFB24; Table S4. DEGs DAFB105; Table S5. High correlation genes with ACO1 like; Figure S1. Cell size variability in the mesocarp; Figure S2. TPM values of VSMuph2.0_chr102g0031(ACC synthase 1).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.I. and T.S.; methodology, H.I., K.M. and T.S.; software, H.I.; investigation, H.I., K.M. (fruit instrumental texture analysis) and T.S.; resources, K.M.; writing—original draft preparation, H.I.; data curation, H.I., K.M. (fruit instrumental texture analysis) and T.S.; Formal analysis, H.I., K.M. (fruit instrumental texture analysis) and T.S.; writing—review and editing, H.I. and T.S.; supervision, T.S.; project administration, T.S.; funding acquisition, H.I. and T.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by JSPS KAKENHI, Grant Numbers JP21K14849 and JP24KJ0330.

Data Availability Statement

The RNA-Seq data have been submitted to the DDBJ Sequence Read Archive (DRA) under BioProject accession PRJDB39879 (Run: DRR892648-DRR892665).

Acknowledgments

This study was conducted under the collaboration agreement between Yamagata University and Yamagata Prefecture. We also thank the staff of the Horticultural Research Institute of Yamagata Prefecture for their technical assistance in vineyard management and sampling. The authors thank Kenta Shirasawa for his valuable advice on bioinformatics analyses, Naoki Sakurai for helpful suggestions on instrumental texture analysis, and Kazuo Ikeda for constructive comments and support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ito, H.; Motomura, Y.; Konno, Y.; Hatayama, T. Exogenous gibberellin as responsible for the seedless berry development of grapes. I. Physiological studies on the development of seedeless delaware grapes. Tohoku J. Agric. Res. 1969, 20, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Motomura, Y.; Ito, H. Exogeanous gibberellin as responsible for the seedless berry development of grapes. II. Role and effects of the prebloom gibberellin application as concerned with the flowering, seedlessness and seedless berry development of Delaware and Campbell Early grapes. Tohoku J. Agric. Res. 1972, 23, 15–32. [Google Scholar]

- Honda, C.; Tanaka, F.; Ohmori, Y.; Tanaka, A.; Komazaki, K.; Izumi, K.; Ichikawa, K.; Kawabata, S.; Nagano, A.J. Differences in the aroma profiles of seedless-treated and nontreated ‘Shine Muscat’ grape berries decrease with ripening. Hortic. J. 2024, 93, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, A.; Yamada, M.; Iwanami, H.; Mitani, N. Quantitative and instrumental measurements of grape flesh texture as affected by gibberellic acid application. J. Jpn. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 2004, 73, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oida, K.; Matsui, M.; Muramoto, Y.; Itai, A. Effects of plant growth regulator treatments in blooming period on rheological properties and cell wall components of mature grape berries of ‘Shine Muscat’. Hortic. Res. (Japan) 2022, 21, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolle, L.; Siret, R.; Segade, S.R.; Maury, C.; Gerbi, V.; Jourjon, F. Instrumental texture analysis parameters as markers of table-grape and winegrape quality: A review. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2012, 63, 11–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conner, P.J. Instrumental textural analysis of muscadine grape germplasm. HortScience 2013, 48, 1130–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oida, K.; Matsui, M.; Muramoto, Y.; Itai, A. Changes in cell wall components on berry texture and adhesion strength of table grape ‘Shine Muscat’ at different ripening stages. Sci. Hortic. 2025, 347, 114198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brummell, D.A. Cell wall disassembly in ripening fruit. Funct. Plant Biol. 2006, 33, 103–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paniagua, C.; Posé, S.; Morris, V.J.; Kirby, A.R.; Quesada, M.A.; Mercado, J.A. Fruit softening and pectin disassembly: An overview of nanostructural pectin modifications assessed by atomic force microscopy. Ann. Bot. 2014, 114, 1375–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.T.; Pelloux, J. The dynamics, degradation, and afterlives of pectins: Influences on cell wall assembly and structure, plant development and physiology, agronomy, and biotechnology. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2025, 76, 85–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmer, D.; Dixon, R.A.; Keegstra, K.; Mohnen, D. The plant cell wall—Dynamic, strong, and adaptable—Is a natural shapeshifter. Plant Cell 2024, 36, 1257–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, J.K.C.; Braam, J.; Fry, S.C.; Nishitani, K. The XTH family of enzymes involved in xyloglucan endotransglucosylation and endohydrolysis: Current perspectives and a new unifying nomenclature. Plant Cell Physiol. 2002, 43, 1421–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eklöf, J.M.; Brumer, H. The XTH gene family: An update on enzyme structure, function, and phylogeny in xyloglucan remodeling. Plant Physiol. 2010, 153, 456–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaewthai, N.; Gendre, D.; Eklöf, J.M.; Ibatullin, F.M.; Ezcurra, I.; Bhalerao, R.P.; Brumer, H. Group III-A XTH genes of Arabidopsis encode predominant xyloglucan endohydrolases that are dispensable for normal growth. Plant Physiol. 2013, 161, 440–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishimaru, M.; Kobayashi, S. Expression of a xyloglucan endo-transglycosylase gene is closely related to grape berry softening. Plant Sci. 2002, 162, 621–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shangguan, L.F.; Mu, Q.; Fang, X.; Zhang, K.K.; Jia, H.F.; Li, X.Y.; Bao, Y.Q.; Fang, J.G. RNA-sequencing reveals biological networks during table grapevine (‘Fujiminori’) fruit development. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0170571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willats, W.G.T.; McCartney, L.; Mackie, W.; Knox, J.P. Pectin: Cell biology and prospects for functional analysis. Plant Mol. Biol. 2001, 47, 9–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunan, K.J.; Sims, I.M.; Bacic, A.; Robinson, S.P.; Fincher, G.B. Changes in cell wall composition during ripening of grape berries. Plant Physiol. 1998, 118, 783–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yakushiji, H.; Sakurai, N.; Morinaga, K. Changes in cell-wall polysaccharides from the mesocarp of grape berries during veraison. Physiol. Plant. 2001, 111, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malacarne, G.; Lagreze, J.; Martin, B.R.S.; Malnoy, M.; Moretto, M.; Moser, C.; Costa, L.D. Insights into the cell-wall dynamics in grapevine berries during ripening and in response to biotic and abiotic stresses. Plant Mol. Biol. 2024, 114, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejsmentewicz, T.; Balic, I.; Sanhueza, D.; Barria, R.; Meneses, C.; Orellana, A.; Prieto, H.; Defilippi, B.G.; Campos-Vargas, R. Comparative study of two table grape varieties with contrasting texture during cold storage. Molecules 2015, 20, 3667–3680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, C.J.; Hur, Y.Y.; Yu, H.-J.; Noh, J.-H.; Park, K.-S.; Lee, H.J. Gibberellin application at pre-bloom in grapevines down-regulates the expressions of VvIAA9 and VvARF7, negative regulators of fruit set initiation, during parthenocarpic fruit development. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e95634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishiyama, S.; Yoshimura, D.; Sato, A.; Yonemori, K. Characterization of tissue-specific transcriptomic responses to seedlessness induction by gibberellin in table grape. Hortic. J. 2022, 91, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, J.F.V. Application of fracture mechanics to the texture of food. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2004, 11, 695–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, S.; Nanjo, Y. A morphological study of Delaware grape berries. J. Jpn. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 1965, 34, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, X.; Li, Z.; Wegner, G.; Zude-Sasse, M. Effect of cell size distribution on mechanical properties of strawberry fruit tissue. Food Res. Int. 2023, 169, 112787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiozaki, S.; Miyagawa, T.; Ogata, T.; Horiuchi, S.; Kawase, K. Differences in cell proliferation and enlargement between seeded and seedless grape berries induced parthenocarpically by gibberellin. J. Hortic. Sci. 1997, 72, 705–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balic, I.; Olmedo, P.; Zepeda, B.; Rojas, B.; Ejsmentewicz, T.; Barros, M.; Aguayo, D.; Moreno, A.A.; Pedreschi, R.; Meneses, C.; et al. Metabolomic and biochemical analysis of mesocarp tissues from table grape berries with contrasting firmness reveals cell wall modifications associated to harvest and cold storage. Food Chem. 2022, 389, 133052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrani, J.C.; Fos, M.; Atarés, A.; García-Martínez, J.L. Effect of Gibberellin and Auxin on Parthenocarpic Fruit Growth Induction in the cv Micro-Tom of Tomato. J. Plant Growth Reg. 2007, 26, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Liang, L.; Zhu, X.; Xiao, K.; Li, T.; Hu, J. Auxin- and cytokinin-induced berries set in grapevine partly rely on enhanced gibberellin biosynthesis. Tree Genet. Genomes 2016, 12, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brummell, D.A.; Dal Cin, V.; Lurie, S.; Crisosto, C.H.; Labavitch, J.M. Cell wall metabolism during the development of chilling injury in cold-stored peach fruit: Association of mealiness with arrested disassembly of cell wall pectin. J. Exp. Bot. 2004, 55, 2041–2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandel, V.; Biswas, D.; Roy, S.; Vaidya, D.; Verma, A.; Gupta, A. Current advancements in pectin: Extraction, properties and multifunctional applications. Foods 2022, 11, 2683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Micheli, F. Pectin methylesterases: Cell wall enzymes with important roles in plant physiology. Trends Plant Sci. 2001, 6, 414–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, E.M.; Mollet, J.-C. Plant cell adhesion: A bioassay facilitates discovery of the first pectin biosynthetic gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 15843–15845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bou Daher, F.; Braybrook, S.A. How to let go: Pectin and plant cell adhesion. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atkinson, R.G.; Sutherland, P.W.; Johnston, S.L.; Gunaseelan, K.; Hallett, I.C.; Mitra, D.; Brummell, D.A.; Schröder, R.; Johnston, J.W.; Schaffer, R.J. Down-regulation of POLYGALACTURONASE1 alters firmness, tensile strength and water loss in apple (Malus × domestica) fruit. BMC Plant Biol. 2012, 12, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Ruotti, V.; Stewart, R.M.; Thomson, J.A.; Dewey, C.N. RNA-Seq gene expression estimation with read mapping uncertainty. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patro, R.; Duggal, G.; Love, M.I.; Irizarry, R.A.; Kingsford, C. Salmon provides fast and bias-aware quantification of transcript expression. Nat. Methods 2017, 14, 417–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrar, K.; Evans, I.M.; Topping, J.F.; Souter, M.A.; Nielsen, J.E.; Lindsey, K. EXORDIUM—A gene expressed in proliferating cells and with a role in meristem function, identified by promoter trapping in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2003, 33, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröder, F.; Lisso, J.; Lange, P.; Müssig, C. The extracellular EXO protein mediates cell expansion in Arabidopsis leaves. BMC Plant Biol. 2009, 9, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McQueen-Mason, S.; Durachko, D.M.; Cosgrove, D.J. Two endogenous proteins that induce cell wall extension in plants. Plant Cell 1992, 4, 1425–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brummell, D.A.; Harpster, M.H. Cell wall metabolism in fruit softening and quality and its manipulation in transgenic plants. Plant Mol. Biol. 2001, 47, 311–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, T.; Zhang, L.; Yu, Y.; Pang, Y.; Tang, X.; Wang, X.; Li, L.; Li, B.; Sun, Q. Identification and expression analysis of xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase (XTH) family in grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.). PeerJ. 2022, 10, e13546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.F.; Hoffman, N.E. Ethylene Biosynthesis and its Regulation in Higher Plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. 1984, 35, 155–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, G.; Yin, X.; Zhang, A.; Wang, M.; Zhu, Q.; Liu, X.; Xie, X.; Chen, K.; Grierson, D. Ethylene and fruit softening. Food Qual. Saf. 2017, 1, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deytieux-Belleau, C.; Vallet, A.; Donèche, B.; Gény, L. Pectin methylesterase and polygalacturonase in the developing grape skin. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2008, 46, 638–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levesque-Tremblay, G.; Pelloux, J.; Braybrook, S.A.; Müller, K. Tuning of pectin methylesterification: Consequences for cell wall biomechanics and development. Planta 2015, 242, 791–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huysmans, M.; Buono, R.A.; Skorzinski, N.; Radio, M.C.; Winter, F.D.; Parizot, B.; Mertens, J.; Karimi, M.; Fendrych, M.; Nowack, M.K. NAC transcription factors ANAC087 and ANAC046 control distinct aspects of programmed cell death in the Arabidopsis columella and lateral root cap. Plant Cell 2018, 30, 2197–2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Yan, J.; Tong, T.; Zhao, P.; Wang, S.; Zhou, N.; Cui, X.; Dai, M.; Jiang, Y.; Yang, B. ANAC087 transcription factor positively regulates age-dependent leaf senescence through modulating the expression of multiple target genes in Arabidopsis. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2023, 65, 967–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, H.; Togano, Y.; Shibuya, T. Effect of GA3 treatment on berry development in the large berry mutant of ‘Delaware’ grapes. Hortic. J. 2023, 92, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuroiwa, H. The application of the Technovit embedding method for the research of plant embryology. Plant Morphol. 1991, 3, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumenkrantz, N.; Asboe-Hansen, G. New method for quantitative determination of uronic acids. Anal. Biochem. 1973, 54, 484–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, M.; Gilles, K.A.; Hamilton, J.K.; Rebers, P.A.; Smith, F. Colorimetric method for determination of sugars and related substances. Anal. Chem. 1956, 28, 350–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McQuinn, R.P.; Wong, B.; Giovannoni, J. AtPDS overexpression in tomato: Exposing unique patterns of carotenoid self-regulation and an alternative strategy for the enhancement of fruit carotenoid content. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2017, 16, 482–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shirasawa, K.; Hirakawa, H.; Azuma, A.; Taniguchi, F.; Yamamoto, T.; Sato, A.; Ghelfi, A.; Isobe, S.N. De novo whole-genome assembly in an interspecific hybrid table grape, ‘Shine Muscat’. DNA Res. 2022, 29, dsac040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.